Abstract

The Australian National Preventive Health Strategy 2021–2030 recommended the establishment of evidence-based frameworks to enable local public health services to identify strategies and interventions that deliver value for money. This study aimed to review the cost-effectiveness of preventive health strategies to inform the reorientation of local public health services towards preventive health interventions that are financially sustainable. Four electronic databases were searched for reviews published between 2005 and February 2022. Reviews that met the following criteria were included: population: human studies, any age or sex; concept 1: primary and/or secondary prevention interventions; concept 2: full economic evaluation; context: local public health services as the provider of concept 1. The search identified 472 articles; 26 were included. Focus health areas included mental health (n = 3 reviews), obesity (n = 1), type 2 diabetes (n = 3), dental caries (n = 2), public health (n = 4), chronic disease (n = 5), sexual health (n = 1), immunisation (n = 1), smoking cessation (n = 3), reducing alcohol (n = 1), and fractures (n = 2). Interventions that targeted obesity, type 2 diabetes, smoking cessation, and fractures were deemed cost-effective, however, more studies are needed, especially those that consider equity in priority populations.

1. Introduction

Driven by the unsustainable burden of chronic disease, a shift is occurring within healthcare systems globally from curative, treatment-focused health towards preventive health. The preventive health approach aims to improve the health and well-being of a population by “reducing the likelihood of a disease or disorder, interrupt or slow the progression or reduce disability” [1]. In conjunction with this shift is an emphasis on health system changes that align with value-based healthcare. While there is no universal definition of what constitutes “value”, fundamentally the approach attempts to deliver financially sustainable healthcare, as opposed to cost reduction, while keeping the needs, experiences, and outcomes that matter to the patient at the core [2].

Integration and adoption of preventive health into existing health systems require leadership and support for significant health service reorientation. Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognises that of the five actions identified in the Ottawa Charter, reorientation of health services has been the most challenging [3]. Several recommendations have been made on how nations can develop strategies that positively influence the reorientation of health services, emphasising that development and design be contextual; achievable within the current health system, resource, and economic capabilities; and aligned with local values and preferences [3].

Like many other high-income countries, Australia’s current health systems focus heavily on treatment of illness and disease, with issues of access to healthcare and health inequity. The National Preventive Health Strategy 2021–2030 aims to rebalance the health system through a long term, systems-based approach [4]. This strategy acknowledges that the burden of ill health is not shared equally among the Australian community, and any service reorientation planning must include concerted efforts to reduce disparities and improve health outcomes among priority populations. In Australia, these groups include, but are not limited to, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD), lesbian, gay, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, and/or sexuality and gender diverse people (LGBTQI+), people with mental illness, people of low socioeconomic status, people with disability, and rural, regional, and remote communities.

One of the policy goals identified within the National Preventive Health Strategy is the establishment of local prevention frameworks [4]. Ideally, these frameworks are evidence based, incorporating the elements of value. Economic evaluations can assist local public health services identify strategies and interventions within their local framework that demonstrate cost-effectiveness, representing value for money. Such evaluations need to consider local contextual factors, such as resource allocation, and what is within jurisdictional purchasing power [5].

Both the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the Productivity Commission have highlighted the need to ensure sustainability of Australia’s health expenditure by addressing the growing disparity in investment in preventive health compared to clinical services, specifically noting that despite the potential for significant returns from investments into preventive health, the field suffers from a relative lack of funding [6,7]. This review specifically seeks to identify where there is evidence of cost-effectiveness or returns on investment in preventive health.

A scoping review is a type of evidence synthesis that can be used to systematically map the scope, characteristics, and findings in an area, which is useful for identifying priority areas for future research, policy, and practice. Therefore, this type of research design is highly appropriate for summarising the evidence base to support the development of local prevention frameworks. To our knowledge, no scoping reviews have been conducted that have identified and mapped the evidence for preventive health strategies for multiple health risk factors and/or health conditions for predominately high-income countries. This review is important to provide a synthesis of relevant findings and draw conclusions based on the strength of the evidence to support translation. The aim of this scoping review was to identify and synthesise the available evidence from systematic reviews on the cost-effectiveness of preventive health strategies with relevance to local public health services, to inform the reorientation of preventive health services and delivery of value-based healthcare.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with JBI methodology for scoping reviews [8] and reported using the PRISMA-ScR Reporting Standards (Table A1) [9] (Appendix A, Table 1). The protocol for the scoping review is provided in Appendix A, Table A2. Due to the exploratory nature of scoping reviews and the breadth of preventive health, a review of reviews approach was used [10], searching for publications that include high-level aggregate data and/or an evidence synthesis of primary trials. The purpose was to extract evidence that has already been synthesised and identify cost-effective focus areas for intervention in preventive health.

Table 1.

Keywords included in search strategy.

2.1. Definition of Key Terms

2.1.1. Types of Preventive Health

Types of preventive health were based on the National Preventive Health Strategy definitions, which represents a continuum spanning from wellness to ill health [4]. Primordial prevention, as defined by the strategy, is focused on the wider determinants of health by addressing the social and environmental factors across the entire population through strategies such as taxation, regulation, and infrastructure [4]. Primordial strategies require multilevel, multisectoral collaboration and investment and therefore fall outside the remit of local public health services. Primary prevention is focused on reducing risk factors to prevent ill health before it occurs through population-level strategies such as vaccination and targeted strategies for high-risk individuals, such as people with high blood pressure, low physical activity, poor dietary intake, or overweight/obesity [4]. Secondary prevention is focused on identifying individuals at high risk of ill health as well as early detection and management of a disease or disorder to either prevent or slow the long-term effects, using strategies such as health screening and counselling and education programmes [4]. Both primary and secondary health promotion are within the remit and purchasing power and embedded in service-level agreements of local public health services. Tertiary prevention focuses on managing established disease or disorder to maximise functional ability [4]. Quaternary prevention focuses on reducing harm from medical interventions used to manage a disease or disorder [4].

Health promotion is the process of “empowering people to increase control over their health and its determinants through health literacy efforts and multisectoral action to increase healthy behaviors” [11]. Disease prevention and health promotion share considerable overlap in goals and functions. The WHO characterise disease prevention services as those primarily concentrated within the healthcare sector, whereas health promotion services depend on intersectoral actions and/or are concerned with the social determinants of health.

2.1.2. Economic Evaluation and Evaluation Methods

For this scoping review, economic evaluation was defined as the “comparative analysis of alternative courses of action in terms of both their costs and consequences” [12]. There are several economic evaluation methods that can be used to evaluate cost-effectiveness. While measurement of cost is common to all methods, measurement and valuation of outcomes vary.

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) measures outcomes in natural health units such as deaths prevented, units of blood pressure, or minutes of physical activity. Cost–utility analysis (CUA) measures outcomes in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), or health-adjusted life years (HALYs), combining survival with quality of life, measured using preference-based, multiattribute utility instruments [13]. Both CEA and CUA compare alternatives using a summary measure, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). ICERs can be compared against a pre-determined cost-effectiveness threshold, recognised as a willingness to pay for a QALY [14]. While thresholds vary between countries and debate surrounds their origins and limitations [15], ICERs provide decision makers with a benchmark to guide value-based decisions and some level of comparability when allocating scarce resources. The United Kingdom has published their willingness to pay threshold for a QALY as from GBP 20,000–30,000 [16]. However, empirical evidence suggests in practice the true threshold sits at GBP 13,000 [17]. In the United States, ICER thresholds range from USD 50,000 to USD 200,000 [18]. The WHO have a published threshold, generally for low- and middle-income countries, set at one to three times the per capita gross domestic product [19]. While Australia has no explicitly stated or public threshold, empirical studies have reported thresholds around AUD 28,000 based on decision-making patterns for pharmaceutical reimbursement [20].

Cost–benefit analysis (CBA) values outcomes in monetary terms with an action deemed cost-effective if the benefit to cost ratio is greater than 1. Cost–consequence analysis (CCA), a form of CBA, includes monetised outcomes where available alongside non-monetised outcomes reported in natural units, allowing decision makers to assess value, albeit subjectively. Cost-minimisation analysis (CMA) is a method commonly associated with non-inferiority trials. Where outcomes are shown to be statistically equivalent between comparators, the analysis is constrained to looking at differences in cost only and the alternative with the lowest cost is favourable. Return on investment (ROI), while not strictly a comparative analytical approach, is the monetary benefit minus cost expressed as a proportion of the cost [21]. For example, a programme that spends AUD 1 and saves AUD 9 in future spending has an ROI of 800%. Social return on investment (SROI) and social cost–benefit analysis (SCBA) are emerging approaches, which attempt to monetise outcomes not typically captured, such as wider social and environmental outcomes [22].

2.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy was developed and tested in consultation with a research librarian (JB) following the mixed method Population, Concept, Context (PCC) framework [23]. The search strategy included grey literature to find reviews of economic evaluations, relevant to local public health services, contained within reports and government documents, and not typically located in peer-reviewed publications.

An initial search strategy was piloted in MEDLINE with iterative screening of the first 100 titles and abstracts until the search terms were set (Table 1). The final search was performed in the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, APO, and MedNar, for review articles published between 2005 and February 2022. The search of the academic literature was limited to 2 databases for pragmatic reasons. The year 2005 was chosen as data from PubMed indicated that 79% of articles related to preventive health interventions and economic evaluation were published after this date (Table A3). Furthermore, health economic evaluations were not vigorously reported until the introduction of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Task Force guidance for economic evaluation alongside clinical trials which occurred in 2005 [24]. Australian health economic and tertiary institution websites were manually searched for the same period, using search filters/terms defined by the institutions’ own search engines. The full search strategy is available in Appendix A (Table A4 and Table A5). Citations identified by the search were collated and uploaded into EndNote X9 [25] and duplicates removed.

2.3. Selection of Articles

Articles were included if they described a review of economic evaluations for primary- and/or secondary-level prevention interventions within or relevant to a local public health service setting. Health promotion was included only when the intervention fell within the resourcing of local public health services. Economic evaluations were restricted to full evaluations, excluding partial economic evaluations (e.g., micro-costings), methodological reviews, or economic frameworks. Reviews were excluded if the authors identified the preventive health strategies as primordial, tertiary, or quaternary. Even though local public health services engage in tertiary preventive health strategies, the scope of this review was focused on primary and secondary prevention, with a view to reorienting health services from illness to wellness.

Clinical treatments, such as medical devices and pharmacotherapy for established disease, were excluded, except for therapies specifically for reducing tobacco use and nicotine addiction. In the absence of a stated level of prevention classification, the National Preventive Health Strategy was used as a reference point [4].

To increase generalisability to the Australian context, reviews of studies predominantly conducted in high-income countries, as defined by the World Bank for 2022 fiscal year [26], were included. Where reviews included studies in both high- and middle-income countries, a cut-off of ≤25% of all studies being from middle-income countries was applied. Reviews of low-income countries, global data, or aggregates of large regions (such as the European Union) were excluded. Non-English publications were also excluded due to resource constraints. Table 2 outlines the full inclusion and exclusion criteria applied for the screening of articles.

Table 2.

Scoping review inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.4. Evidence Screening and Selection

Pilot screening was conducted on titles and abstracts by two independent reviewers (DS, AH) for assessment against the initial eligibility criteria, with discrepancies resolved and revisions made to clarify eligibility criteria (Table 2). The remainder of the screening and selection process was undertaken primarily by one reviewer (DS), with 20% screened in duplicate by a second reviewer (AH); agreement was high at >95%.

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data extraction was completed by two reviewers (DS, RT) with 20% screened by a third reviewer (AH). Data extraction was conducted within Microsoft Excel software (v16). Characteristics of the studies in each review were extracted, including the number of countries represented, date range of publication, review aim, population included, median sample size, and type of prevention intervention. Extracted data were then descriptively or quantitatively summarised (i.e., median, minimum, maximum). Detailed mapping of the priority populations, as defined by the National Preventive Health Strategy [4], included in each of the reviews was undertaken.

The economic evaluation characteristics and results of each review were extracted, including the number of economic evaluations, method of analysis, study design, valuation of outcomes, and key economic findings. There is debate in the literature regarding the value of meta-analysis for economic evaluations that are heterogeneous [27,28]; therefore, a narrative approach was taken to summarise the study findings. Intuitive conclusions were drawn from the economic evidence within each focus area, classified into the following categories: cost-effective, not cost-effective, lack of evidence, and unclear, based on the criteria reported in Table 3. Where there were multiple reviews concluding cost-effectiveness within the same focus area (e.g., type 2 diabetes), the individual studies were compared across reviews to identify overlap and avoid misrepresenting the strength of evidence.

Table 3.

Criteria for evaluating the economic evidence from the systematic reviews.

2.6. Risk of Methodological Bias Appraisal of the Body of Evidence

In accordance with scoping review methods, appraisal of the risk of economic methodological bias in the included reviews was not conducted [9]. However, methodological appraisals conducted within the reviews, including assessment tools used, were extracted as part of the study characteristics.

3. Results

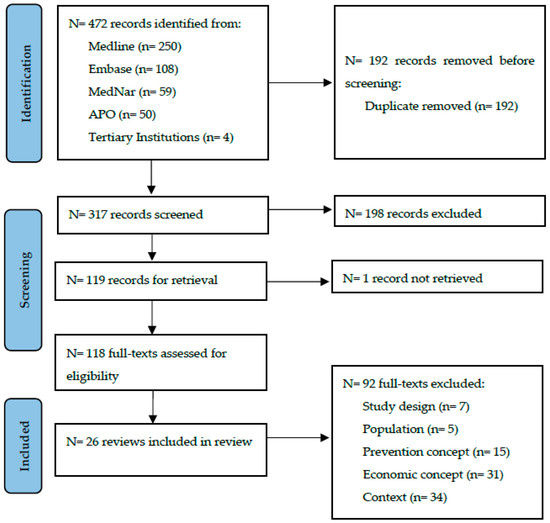

A total of 472 records were identified during the initial search with 192 duplications, returning 317 unique articles for screening. At title and abstract screening, 198 records were excluded, and 1 article not able to be retrieved. One hundred and eighteen full text articles were assessed for eligibility. A total of 26 systematic reviews were included in full data extraction. The results of each stage are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) depicting the identification, screening, and inclusion of reviews.

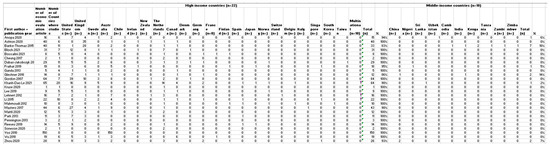

3.1. Characteristics of Included Reviews

The characteristics of the 26 included systematic reviews are described in Table 4. The systematic reviews were predominately (19 of 26) published between 2015 and 2021. Across the systematic reviews, there were 674 economic evaluation studies, conducted in high-income (n = 22 countries) and middle-income (n = 10) countries (Figure A1). All systematic reviews (26 of 26) had ≥90% of included studies from high-income countries. Many of the reviews (n = 18) included studies conducted in Australia. Vos et al. [29] exclusively included 150 preventive health interventions that were modelled with the Australian population in 2003 as well as 21 interventions for the Australian indigenous population. The authors of these reviews did not report there was a significant difference in the findings of Australian studies versus other high-income countries. The sample population of the studies in the systematic reviews included universal (n = 7), adults (n = 13), adults and adolescents (n = 3), and children (n = 3). The systematic reviews that included priority populations are summarised in Table 5. The highest proportion of systematic reviews in priority populations included people with disabilities (11 of 26 reviews) and mental illness (10 of 26). Very few systematic reviews included Indigenous people (1 of 26) and LGBTQI+ (1 of 26). Only half (13 of 26) reported the sample sizes of the included studies; for these the median sample was 911 individuals (minimum = 196, maximum = 1,216,000).

Table 4.

Characteristics of included systematic reviews.

Table 5.

Priority populations a of included systematic reviews.

Most systematic reviews (22 of 26) aimed to identify studies related to specific interventions (e.g., psychological) for a risk factor or condition (e.g., psychotic experiences). The remaining four aimed to identify economic evaluations in public health, without limiting to any particular focus area. Within reviews, studies were often grouped by characteristics such as population, intervention sub-types, intervention approach (i.e., universal vs. targeted), method of economic evaluation, methodological quality, and type of economic outcomes reported. More than half of the reviews (16 of 26) included interventions that targeted primary prevention. Prevention focus areas included mental health (n = 3 reviews), obesity (n = 1), type 2 diabetes (n = 3), dental caries (n = 2), public health (n = 4), chronic disease (n = 5), sexual health (n = 1), immunisation (n = 1), smoking cessation (n = 3), reducing alcohol (n = 1), and fractures (n = 2).

3.2. Economic Evaluation Methods

The economic evaluation methods and key findings are described in Table 6. The median number of economic evaluation studies included in the systematic reviews was 16 (minimum = 1, maximum = 150). Economic analysis methods included CEA, CUA, CBA, CCA, SROI, and ROI.

Table 6.

Economic evaluation methods, risk of bias assessment, and key findings.

3.3. Risk of Methodological Bias of the Evidence from the Systematic Reviews

Twenty of twenty-six systematic reviews used an assessment tool to appraise the risk of economic methodological bias (Table 6). The quality assessment tools used included: the Drummond Critical Appraisal of Economic Evaluations Checklist (n = 6) [52], guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the British Medical Journal (n = 4) [52], Krlev et al.’s framework (n = 2) [53], Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) Checklist (n = 2) [54], Assessing Cost Effectiveness (ACE) Study Priority-Setting Checklist (n = 1) [29], Community Guide protocol for economic evaluations (n = 1) [55], Consensus on Health Economics Criteria list (n = 1) [56], Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (n = 1) [57], Quality of Health Economic Studies Instrument (n = 1) [58], National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality appraisal checklist for economic evaluations (n = 1) [59], and Philips’s Checklist (n = 1) [60]. Eleven systematic reviews [18,21,22,30,33,35,38,40,42,43,48] concluded that at least 70% of studies were highly rated for their methodological quality (Table 7). Limitations of the evidence commonly related to the use of a short time horizon, limited perspective for the economic analysis, and a higher proportion of studies from the United States.

Table 7.

Categorisation of the cost-effectiveness of intervention by health area for the included systematic reviews (n = 26).

3.4. Cost-Effective or Not Cost-Effective?

The categorisation of the cost-effectiveness of the interventions by health area for the included systematic reviews is reported in Table 7 and summarised below. Details about the type of interventions included in the reviews are provided in Appendix A Table A6.

3.4.1. Mental Health

Three systematic reviews [18,30,31] evaluated the economic evidence of mental health interventions. Le at al. [30] reviewed primary intervention studies (n = 65) for mental health disorders and mental health promotion across all life stages. The main types of interventions included were cognitive behavioural therapy, standard psychological intervention, school-based interventions, parenting interventions, and screening plus psychological interventions. Li et al. [34] classified 64% of the interventions as “unclear” since the health benefits associated with the intervention were at a higher cost. Thirty four percent of the interventions were classified as “favoured” which focused on children, adolescents, or adults and targeted the prevention of depression and suicide or promotion of mental health. The cost-effectiveness of these interventions was classified as not clear due to the broad scope of the systematic review which considered interventions that targeted multiple mental health conditions across different life stages.

Park et al. [31] reviewed secondary intervention studies (n = 11) for physical health promotion in adults and older adults with mental health disorders. There was a wide range of interventions that were included, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, physical exercise, and smoking cessation programmes. The cost-effectiveness of these interventions was classified as not clear. While there were 11 studies in the review the studies were too heterogeneous to draw conclusions on cost-effectiveness.

Soneson et al. [18] reviewed secondary prevention interventions (n = 2) for psychotic experiences in adolescents and adults. There was insufficient evidence to determine the cost-effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy interventions; the two articles identified were based on data from a single RCT.

3.4.2. Obesity

One systematic review [32] evaluated the long-term (≥40 years) impact of primary prevention intervention studies (n = 16) for obesity for all life stages. The main types of interventions included diet, physical activity, and lifestyle. Lehnert et al. [32] reported that 81% of behavioural and 75% of community interventions were cost-effective or cost-saving. In particular, this systematic review found that seven of nine lifestyle interventions were cost-effective [32]. These interventions were predominately (83%) in adults and the economic evidence for interventions that targeted children was not favourable. Interventions targeting adults were therefore classified as cost-effective, while interventions in children were classified as lacking evidence as only three studies were included. Nine of sixteen studies included in the review were based on economic evidence from the Australian ACE study on prevention of obesity, which overlapped with studies included in the systematic review by Vos et al. [29] included in this scoping review; however, this did not change the interpretation of obesity prevention being cost-effective.

3.4.3. Type 2 Diabetes

Three systematic reviews [33,34,35] evaluated the economic evidence of type 2 diabetes interventions for adults. Interventions were classified as cost-effective across all three systematic reviews. Glechner et al. [33] reported that 94% of studies (n = 14) found that diet and physical activity intervention studies were cost-effective. Li et al. [34] reported that 85% of diet and physical activity intervention studies (n = 22) were cost-effective. Group-based programmes were found to be more cost-effective compared with individual-based programmes [33]. Zhou et al. [35] reported that lifestyle interventions targeting diet and physical activity were the most cost-effective interventions, followed by metformin interventions. The median ICERs for group-based interventions were less than half of those for individual-based interventions [35]. In total there were 64 studies included across the 3 systematic reviews; 18 studies (28%) overlapped between reviews. There were sixteen studies that overlapped between two reviews, and two studies between three systematic reviews; this did not change the interpretation of type 2 diabetes prevention being cost-effective.

3.4.4. Dental Caries

Two systematic reviews [36,37] evaluated the economic evidence of dental caries interventions in children. Anopa [36] reviewed primary prevention intervention studies (n = 16) for dental caries in pre-school-aged children. The main types of interventions included were multicomponent interventions, fluoride treatment, molar sealant, and oral hygiene and diet education. The cost-effectiveness of these interventions was classified as unclear since only 40% and 50% of studies that conducted CEA and CBA, respectively, reported the interventions to be cost-effective. Fraihat et al. [37] also reviewed prevention studies (n = 19) but for both pre-school-aged and primary-aged children. A wide variety of interventions were included and sub-group analyses indicated that primary prevention interventions were only effective in reducing incremental cost for children older than six years (n = 4) and were not cost-effective for children less than six years old (n = 14). These interventions were classified as not clear due to the mixed findings.

3.4.5. Public Health

Four systematic reviews [21,22,38,39] evaluated the economic evidence of public health interventions. A wide variety of interventions were included such as physical activity, substance misuse, child behavioural management, community-based programmes, and healthy lifestyle interventions. These reviews were broad in scope and included interventions that targeted multiple health conditions across different life stages. As the studies included were too heterogeneous to draw conclusions, cost-effectiveness was classified as unclear for the four systematic reviews.

3.4.6. Chronic Disease

Five systematic reviews [29,40,41,42,43] evaluated the economic evidence for chronic disease prevention. Three systematic reviews [29,40,41], including one review in which the interventions were modelled exclusively on the Australian population, were broad in scope and included interventions that targeted multiple health conditions across different life stages. Therefore, the cost-effectiveness of interventions was assessed as unclear for these three systematic reviews. Mattli et al. [42] reviewed physical activity intervention studies (n = 12) for chronic disease in adults. These interventions were classified as not cost-effective since 82% of the studies reported an ICER above the cut-off defined by Mattli et al. [42]. The systematic review of lifestyle interventions for chronic disease prevention in adults by Pennington et al. [43] only included three studies; therefore, it was classified as lacking evidence.

3.4.7. Sexual Health

One systematic review [44] evaluated primary and secondary intervention studies (n = 31) for sexually transmitted infections and human immunodeficiency virus. The majority (25 of 31 studies) of the included studies assessed the cost-effectiveness of different screening approaches for chlamydia trachomatis. The cost-effectiveness of these interventions was classified as unclear, because findings were mixed with 52% of the studies indicating that chlamydia trachomatis screening is cost-effective for adults less than 30 years of age.

3.4.8. Immunisation

One systematic review [45] evaluated economic evidence of influenza vaccination studies (n = 8) for children. Influenza vaccines were classified as cost-effective since all included studies in the systematic review concluded that vaccinations, specifically the quadrivalent formulation, were cost-effective. Six of eight studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies or employees were co-authors of articles.

3.4.9. Smoking Cessation

Three systematic reviews [46,47,48] evaluated the economic evidence of smoking cessation interventions for adults. Cheung et al. [46] reviewed online smoking cessation interventions in the Netherlands. There was a lack of evidence to draw conclusions about the cost-effectiveness of these interventions, as only two eligible studies were identified.

The two other reviews on smoking cessation were classified as cost-effective. Lee et al. [47] reviewed adult inpatient smoking cessation interventions (n = 9) and found they were highly cost-effective and the degree of cost-effectiveness might not be related to the components of the programme or methodological variations in the cost-effectiveness analysis. Mahmoudi et al. [48] reviewed non-nicotine therapies for smoking cessation (n = 10) and found varcenicline (a drug that blocks nicotine from triggering the release of dopamine) was clinically superior and cost-saving compared to bupropion (a drug used to balance dopamine levels when nicotine is excreted from the body) in most cost-effectiveness models. Variations in time horizon, cost of bupropion, efficacy of either drug, age, and the incidence of smoking-related disease were noted as factors that could change the interpretation of results.

3.4.10. Reducing Alcohol

One systematic review [49] evaluated the economic evidence of telehealth medicine for alcohol abuse, addiction, and rehabilitation. There was a lack of evidence to draw conclusions about the cost-effectiveness as only one study was included in the review.

3.4.11. Fractures

Two systematic reviews [50,51] evaluated the economic evidence for a fracture liaison service programme and it was categorised as cost-effective. Ganda et al. [50] reported that four of four studies on identification, assessment, and treatment of patients as part of the service showed it was cost-saving or cost-effective. One study on identification, assessment, and then referral for treatment by a primary care physician also showed it was cost-effective. Wu et al. [51] reported that the fracture liaison service was cost-effective regardless of the intensity of the service delivery or the country of the implemented service. In total there were twenty-four studies included across the two systematic reviews; one study (4%) was identified in both systematic reviews; however, this did not change the interpretation of fracture prevention being cost-effective.

4. Discussion

This review used a systematic approach to map the best of the available evidence regarding the cost-effectiveness of preventive health strategies. The accessibility of economic evidence nationally and internationally and the health economics knowledge and skills of health decision makers are significant barriers for the use of economic evidence in decision making [61,62]. Therefore, the scope, characteristics, and findings of research in this area were synthesised and summarised to provide visibility to existing evidence for local public health services. This can be used in priority setting and to inform the development of local prevention frameworks that support the reorientation and delivery of value-based healthcare.

Our evidence synthesis of 26 systematic reviews found obesity (in adults), type 2 diabetes, smoking cessation, immunisation, and fracture prevention were cost-effective preventive health areas, based on existing evidence. For more than half (65%) of the reviews there was either not enough evidence to draw conclusions or the findings were unclear. This review provides clear guidance for where further economic evaluations are needed within preventive health.

In Australia, the National Preventive Health Strategy 2021–2030 identified seven focus areas for the prevention of chronic disease which include nutrition, physical activity, tobacco, immunisation, cancer screening, alcohol and other drug use, and mental health [4]. These focus areas were given priority to boost prevention in the first years of the strategy as cancer, mental health, and substance abuse disorders were the leading national burden of disease groups in 2015 [63]. Tobacco use, overweight and obesity, and dietary risks are the main modifiable factors contributing to the national disease burden [63]. Cadilhac et al. [64] reported that by targeting five risk factors (poor diet, physical activity, tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, and overweight and obesity), cost savings of AUD 2334 million over the lifetime of the Australian adult population could be achieved. While the strategy aims to promote health benefits particularly in communities with health inequalities and generate health gains across all life stages through impactful and coordinated initiatives within these focus areas [4], local public health services are required to implement state-level frameworks that are not well aligned with the strategy.

The economic methodology of the studies included in the systematic review varied widely based on modelling approach (e.g., trial-based analysis, modelled dichotomy economic evaluations), time frame, perspective of analysis, and study context. This heterogeneity was acknowledged within various systematic reviews [35,40,47] and precluded meta-analysis, therefore a narrative approach was taken. There are pros and cons for each of the modelling approaches. An advantage of “trial-based analysis” is that the relative treatment effect is based on a study design that minimises the risk of selection bias through use of randomisation. However, it is argued that “trial-based analysis” represents only a partial form of analysis because the study design only compares a limited number of interventions, the length of follow-up is shorter than what is required for economic analysis, it may not be relevant to the decision context, it does not incorporate all evidence that is available, and the decision uncertainty can only be quantified based on evidence from the trial (a single input) [65]. “Modelled” dichotomy economic evaluations have the advantage of being able to fully characterise decision uncertainty by combining data from multiple inputs including clinical efficiency data from trials. Two systematic reviews [22,38] evaluated studies that used SROI and SCBA which are recently adopted approaches for conducting economic evaluations. These systematic reviews identified that SROI and SCBA studies have predominately been implemented in the United Kingdom and published in the grey literature [22,38]. The methodological weaknesses (e.g., use of estimated or subjective parameters, assumptions are required) associated with these approaches have been acknowledged as a contributing factor for the lack of published studies in the peer-reviewed literature.

This scoping review has several strengths. Firstly, health service stakeholders co-created the design, conduct, analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. The scoping review was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR Reporting Standards. The review synthesised the highest level of evidence (systematic review) and included preventive health strategies that targeted any type of health problem across different life stages. The review also has some limitations that should be considered. The search of the academic literature was limited to two databases: MEDLINE and Embase. The search terms were not exhaustive and included studies were limited to those published in English between 2005 and 2022. Reviews were only included if primary and secondary preventive health strategies were relevant to local public health services and studies were predominately conducted in high-income countries. Studies were conducted in a wide variety of healthcare settings which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other local public health services. However, reviews in the type 2 diabetes focus area included the prescription of metformin as the study intervention which is a treatment rather prevention and is outside the scope of local public health services. These reviews were included to avoid excluding diabetes prevention programme interventions as the study intervention or comparator which is relevant to local public health services.

Preventive health interventions, such as sustained behaviour change compared with clinical interventions, require a long-term follow-up period or modelled dichotomy economic evaluations to observe the anticipated health gains. Many of the trial-based analyses were reliant on interventions with a short-term follow-up period and, therefore, the economic benefits were limited to intermediate indicators. The perspective of the analysis varied considerably by the studies included in the systematic reviews. This may reflect the lack of consensus on the recommendations from the study perspective provided by national healthcare economic evaluation guidelines [65,66]. Weise et al. [67] recently reviewed the assessment approaches for transferability and recommended that the assessment methods chosen should be relevant to the health area and the context of the decision making.

4.1. Implications

In this review, the following preventive interventions were concluded to be cost effective: adult obesity (behavioural and community interventions), type 2 diabetes (lifestyle interventions), smoking cessation (adult inpatient programme and non-nicotine therapies), immunisation, and fracture prevention (fracture liaison service programme). However, to enable the use of economic evidence to inform public policy agendas and political prioritisation, local public health services may still want to consider if systematic review evidence is transferable to their local context prior to setting policies and implementing the evidence. One study by Nystrand et al. [64] examined delivery differences, feasibility of implementation, costings, and intervention outcomes when assessing the potential transferability of systematic review evidence of the cost-effectiveness of public health interventions targeting the use of alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco, as well as problematic gambling behaviour. While this approach may have utility, it is resource intensive. In comparison, Welte et al. [68] and Goeree et al. [69] developed user-friendly decision charts and a classification system that indicates transferability factors and approaches for improving transferability to support decision-making processes.

4.2. Future Research Directions

For many (65%) of the systematic reviews, the authors of the current scoping review concluded there was not enough evidence or the evidence was unclear regarding the cost-effectiveness of the interventions. This highlights the need for further research so more definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding the economic evidence for preventive health interventions. Greater consideration is also needed for priority populations in future research, especially for Indigenous people and LGBTQI+. Wider determinants of health such as social, environmental, structural, economic, cultural, biomedical, commercial, and digital factors prevent these priority populations from having fair and just opportunities to attain the highest level of health and lead to inequity [4]. The United National 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development strives to “leave no one behind”; this commitment is reflected in 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [70]. A call to achieve health equity is implied in SDG3 “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” [70]. The National Health Strategy also aims to address health equity in priority populations [4]. Therefore, ensuring that equity is considered in future research is important as this is a high priority for local public health services for informing policy. However, cost-effectiveness analysis was primarily designed to optimise efficiency in the allocation of healthcare resources without considering health equity [71]. This prevents local public health services from understanding if there are any trade-offs between efficiency and equity. Alternative methods to the traditional cost-effectiveness analysis have been developed, such as equity-informative cost-effectiveness analysis and distributional cost-effectiveness analysis, which is an important step for the consideration of health equity in future economic evaluations [72,73,74,75].

Conducting prospective economic evaluations in which costs are recorded for the intervention design and local adaptation, implementation, and scale-up will be essential. Sohn et al. [76] has provided a conceptual framework consisting of three phases: design, initiation, and maintenance, to assist researchers in assessing implementation costs. Jalai et al. [77] recently reviewed statistical approaches for addressing missing data when conducting prospective economic evaluations alongside clinical trials. This evidence will assist local public health services in understanding the application of potential interventions for use in different contexts.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review identified a large amount of evidence from systematic reviews on the cost-effectiveness of preventive health strategies, however, for most reviews there was a lack of evidence or the evidence was unclear. Interventions targeting obesity, type 2 diabetes, smoking cessation, and fractures were found to be cost-effective. We found limited evidence related to equity in priority populations. Local contextual factors need consideration in the translation of these findings into practice, including local public health services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.R., N.K., A.S., A.B. and A.H.; methodology, D.S., R.T. and A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.T., D.S. and A.H.; writing—review and editing, R.T., D.S., P.R., N.K., A.S., E.S., A.B., C.W. and A.H.; supervision, P.R. and A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank and acknowledge the support from Research Librarian Jessica Birchall (JB), University of Newcastle, who assisted with developing the search strategy. We thank Anthea Bill for expertise and assistance in reviewing the content of the drafted manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.

Table A1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.

| Section | Item | PRISMA-ScR Checklist Item | Reported on Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | Page 1, Lines 2–3 |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | Page 1, Lines 16–29 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | Pages 1–2 Lines 34–84 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | Page 2 Lines 84–88 |

| Methods | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | Page 2, Line 92 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | Pages 4–5 Lines 189–210 |

| Information sources * | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | Page 4 Lines 165–185 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | Page 4, Lines 183–184 |

| Selection of sources of evidence † | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | Page 5, Line 212–216 |

| Data charting process ‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | Page 5, Lines 218–236 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | Page 5, Lines 218–236 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence § | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | Page 5, Lines 238–241 |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | Page 5, Lines 218–236 |

| Results | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | Page 7, Figure 1 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | Pages 8–11 Table 4 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | Pages 21–22, Table 7 |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | Pages 16–20, Table 6 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | Pages 21–22, Table 7 |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | Page 22–23 Lines 478–529 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | Page 23 Lines 536–547 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | Page 24, Lines 560–605 |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | Page 25, Line 622 |

JBI = Joanna Briggs Institute; PRISMA-ScR = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews. * Where sources of evidence (see second footnote) are compiled from, such as bibliographic databases, social media platforms, and websites. † A more inclusive/heterogeneous term used to account for the different types of evidence or data sources (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy documents) that may be eligible in a scoping review as opposed to only studies. This is not to be confused with information sources (see first footnote). ‡ The frameworks by Arksey and O’Malley (6) and Levac and colleagues (7) and the JBI guidance (4, 5) refer to the process of data extraction in a scoping review as data charting. § The process of systematically examining research evidence to assess its validity, results, and relevance before using it to inform a decision. This term is used for items 12 and 19 instead of “risk of bias” (which is more applicable to systematic reviews of interventions) to include and acknowledge the various sources of evidence that may be used in a scoping review (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy document).

Table A2.

Scoping review protocol.

Table A2.

Scoping review protocol.

| Scoping Review Details | ||

|---|---|---|

| Scoping review title | Health Economic Considerations in the Development of a Local Health District Preventive Care Framework | |

| Review objectives |

| |

| Review questions |

| |

| Databases | MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus | |

| Grey literature | Analysis & Policy Observatory (APO), MedNar Institutions and associations within the fields of

Records limited to

| |

| Search period | Published in the period 2005 to 2022 | |

| Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Population, patient, or problem | Studies that relate to the whole district population Key terms include:

|

|

| Intervention | Studies that relate district-level strategies and frameworks to implement preventive health

|

|

| Comparator |

|

|

| Context/Content | Studies relating to preventive care frameworks from the public health service perspective

|

|

| Outcomes | Studies in which the cost-effectiveness of the intervention and/or downstream final outcomes are measured and valued Economics

|

|

| Types of studies |

|

|

| Study design |

|

|

| Types of evidence sources |

| |

| Evidence source details and characteristics | ||

| Citation details | Author(s) Publication year Source origin/country of origin | |

| Details/results extracted from source of evidence | ||

| Study characteristics | Publication type No. of reviews or studies included Population type Preventive care strategy type Cost-effective outcome Valuation of final downstream outcomes | |

| Screening the evidence | ||

| Number of reviewers | 2 | |

| Process for piloting screening, inclusion, and identification process | A single reviewer (DS) will screen possible records based on title and abstract for inclusion and then in full-text article retrieval. Identification of records will be performed by DS and AJH | |

| Management of disagreements | If there are disagreements between the two reviewers and consensus cannot occur, a third reviewer (PR) will assess the source to determine its eligibility | |

| Software used in selection | EndNote | |

* Adapted from JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, Chapter 6 Systematic reviews of economic evaluations and Chapter 11 (Scoping reviews).

Table A3.

PubMed search of articles published between 1965 and 2022. Search query: preventive health intervention and economic evaluation.

Table A3.

PubMed search of articles published between 1965 and 2022. Search query: preventive health intervention and economic evaluation.

| Year of Publication | Number of Articles Published |

|---|---|

| 2022 | 512 |

| 2021 | 647 |

| 2020 | 719 |

| 2019 | 809 |

| 2018 | 820 |

| 2017 | 785 |

| 2016 | 726 |

| 2015 | 748 |

| 2014 | 672 |

| 2013 | 647 |

| 2012 | 623 |

| 2011 | 540 |

| 2010 | 474 |

| 2009 | 458 |

| 2008 | 432 |

| 2007 | 382 |

| 2006 | 349 |

| 2005 | 310 |

| 2004 | 261 |

| 2003 | 228 |

| 2002 | 229 |

| 2001 | 239 |

| 2000 | 240 |

| 1999 | 200 |

| 1998 | 190 |

| 1997 | 168 |

| 1996 | 166 |

| 1995 | 118 |

| 1994 | 116 |

| 1993 | 116 |

| 1992 | 92 |

| 1991 | 91 |

| 1990 | 63 |

| 1989 | 52 |

| 1988 | 39 |

| 1987 | 26 |

| 1986 | 28 |

| 1985 | 22 |

| 1984 | 26 |

| 1983 | 22 |

| 1982 | 14 |

| 1981 | 14 |

| 1980 | 8 |

| 1979 | 7 |

| 1978 | 15 |

| 1977 | 9 |

| 1976 | 12 |

| 1975 | 6 |

| 1974 | 1 |

| 1973 | 1 |

| 1972 | 1 |

| 1971 | 4 |

| 1965 | 1 |

Table A4.

Peer-reviewed literature search strategy.

Table A4.

Peer-reviewed literature search strategy.

| Search Set | MEDLINE Primary Prevention | Results | MEDLINE Secondary Prevention | Results | EMBASE Primary Prevention | Results | EMBASE Secondary Prevention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Public Health/ec | 3675 | Public Health/ec | 3677 | public health/ | 216,169 | public health/ | 89,658 |

| 2 | Health Promotion/ec | 2945 | Health Promotion/ec | 2946 | health promotion/ | 104,403 | health promotion/ | 78,797 |

| 3 | Primary Prevention/ec | 748 | Secondary Prevention/ec | 214 | primary prevention/ | 43,974 | secondary prevention/ | 22,101 |

| 4 | Efficiency, Organizational/ec [Economics] | 2007 | Efficiency, Organizational/ec [Economics] | 2007 | organizational efficiency/ | 1185 | organizational efficiency/ | 22,304 |

| 5 | conceptual framework.mp. | 14,252 | conceptual framework.mp. | 14,291 | conceptual framework.mp. | 41,767 | conceptual framework.mp. | 14,308 |

| 6 | health care service *.mp. | 17,729 | health care service *.mp. | 17,751 | health care service *.mp. | 21,337 | health care service *.mp. | 17,761 |

| 7 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 | 40,968 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 | 40,589 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 | 411,813 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 | 237,994 |

| 8 | (prevent * or promot *).mp. | 3,672,540 | (prevent * or promot *).mp. | 3,677,713 | (prevent * or promot *).mp. | 4,543,210 | (prevent * or promot *).mp. | 3,679,847 |

| 9 | (health prevention or health promotion).mp. | 100,740 | (health prevention or health promotion).mp. | 100,830 | (health prevention or health promotion).mp. | 121,932 | (health prevention or health promotion).mp. | 100,857 |

| 10 | 8 or 9 | 3,672,540 | 8 or 9 | 3,677,713 | 8 or 9 | 4,543,210 | 8 or 9 | 3,679,847 |

| 11 | Cost-Benefit Analysis/or Value for Money.mp. or Health Care Costs/ | 122,325 | Cost-Benefit Analysis/or Value for Money.mp. or Health Care Costs/ | 122,423 | Cost-Benefit Analysis/or Value for Money.mp. or Health Care Costs/ | 250,377 | Cost-Benefit Analysis/or Value for Money.mp. or Health Care Costs/ | 122,489 |

| 12 | Economic evaluation.mp. | 11,627 | Economic evaluation.mp. | 11,651 | Economic evaluation.mp. | 26,535 | Economic evaluation.mp. | 11,654 |

| 13 | ((Cost Effective or Cost Utility or Cost Benefit or Cost Consequence or Cost minimis *) adj Analys?s).mp. | 92,632 | ((Cost Effective or Cost Utility or Cost Benefit or Cost Consequence or Cost minimis *) adj Analys?s).mp. | 92,721 | ((Cost Effective or Cost Utility or Cost Benefit or Cost Consequence or Cost minimis *) adj Analys?s).mp. | 103,559 | ((Cost Effective or Cost Utility or Cost Benefit or Cost Consequence or Cost minimis *) adj Analys?s).mp. | 92,762 |

| 14 | (Return of Investment or return to investment or Social Return of Investment or social return to investment).mp. | 2199 | (Return of Investment or return to investment or Social Return of Investment or social return to investment).mp. | 2202 | (Return of Investment or return to investment or Social Return of Investment or social return to investment).mp. | 2903 | (Return of Investment or return to investment or Social Return of Investment or social return to investment).mp. | 2200 |

| 15 | (cost effective * or efficien * or cost saving * or cost analys?s or return on).mp. | 1,351,342 | (cost effective * or efficien * or cost saving * or cost analys?s or return on).mp. | 1,353,818 | (cost effective * or efficien * or cost saving * or cost analys?s or return on).mp. | 1,627,269 | (cost effective * or efficien * or cost saving * or cost analys?s or return on).mp. | 1,354,960 |

| 16 | 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 | 1,417,128 | 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 | 1,419,644 | 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 | 1,819,368 | 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 | 1,420,811 |

| 17 | 7 and 10 and 16 | 3050 | 7 and 10 and 16 | 2756 | 7 and 10 and 16 | 17,744 | 7 and 10 and 16 | 9822 |

| 18 | review.m_titl. | 585,846 | review.m_titl. | 587,375 | review.m_titl. | 697,162 | review.m_titl. | 588,146 |

| 19 | 17 and 18 | 166 | 17 and 18 | 156 | 17 and 18 | 796 | 17 and 18 | 498 |

| 20 | limit 19 to (english language and humans and yr = “2005–Current”) | 128 | limit 19 to (english language and humans and yr = “2005–Current”) | 122 | limit 19 to (human and english language and yr = “2005–Current”) | 679 | limit 19 to (human and english language and yr = “2005–Current”) | 414 |

| 21 | limit 20 to COVID-19 | 31 | limit 20 to COVID-19 | 7 | ||||

| 22 | 20 not 21 | 648 | 20 not 21 | 407 | ||||

| 23 | “cost effect *”.m_titl. | 45,637 | “cost effect *”.m_titl. | 31,253 | ||||

| 24 | 22 and 23 | 61 | 22 and 23 | 47 |

* Search operator.

Table A5.

Grey literature search strategy.

Table A5.

Grey literature search strategy.

| APO | Results | MedNar | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date accessed | 15 February 2022 | Date accessed | 15 February 2022 | ||

| Subject | Economics | Search terms | population health framework economic evaluation | ||

| Search terms | Preventive health | 1375 | Cluster | Medical | 1400 |

| Subject | Preventive health | 50 | Topics | Cost-effective | 62 |

| Date published | All 2012–2021 | 50 | Authors | All | 62 |

| Collection | All | 50 | Publications | All | 62 |

| Publisher | All | 50 | Source | All | 62 |

| Author/creator | All | 50 | Dates | All (2008 to 2022) | 59 |

| Geographic coverage | All | 50 | Document Format | All | 59 |

| Resource type | All | 50 | Document Type | All | 59 |

| Results | 50 | Results | 59 |

Table A6.

Summary of cost-effective interventions for studies included in the review.

Table A6.

Summary of cost-effective interventions for studies included in the review.

| First Author, Year of Review | Target Problem | Target Population | Type of Intervention | Total No. of Cost-Effective Studies | Design of the Cost-Effective Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health | |||||

| Le, 2021 [30] | Anxiety | Children | CBT | 2 of 2 | 1 RCT, 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Anxiety | Parents and children | CBT | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Anxiety | Parents | CBT | 2 of 2 | 1 RCT, 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Children | School-based intervention | 1 of 2 | 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Children | Psychological intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Behavioural problems | Children | Psychological intervention | 1 of 1 | Pre–post study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Behavioural problems | Parents and children | Screening and parent psychoeducation | 0 of 1 | N/A |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Behavioural problems | Parents | Parent psychoeducation | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Suicide prevention | Children | CBT | 0 of 1 | N/A |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Suicide prevention | Children | School-based intervention | 0 of 1 | N/A |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Suicide prevention | Children | Screening | 0 of 1 | N/A |

| Le, 2021 [30] | General mental health | Divorced families | Parenting programme or child and parenting programme | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Maltreatment | Children | Psychological intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Adolescents | CBT | 2 of 2 | 1 RCT, 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Adolescents | School-based CBT | 0 of 1 | N/A |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Adolescents | Physical activity intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Eating disorders | Adolescents | School-based intervention | 1 of 2 | 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Drug use | Adolescents | Education and training programmes | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Bullying | Adolescents | School programme | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Adults | Psychological intervention | 4 of 4 | 1 RCT, 3 model studies |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Adults | CBT | 3 of 3 | 1 RCT, 2 model studies |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Adults | Psychological intervention | 3 of 4 | 1 RCT, 2 model studies |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Adults | Brief bibliotherapy | 1 of 1 | N/A |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Adults | Workplace education | 1 of 1 | 1 pre–post-test study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Adults | Peer support intervention | 1 of 1 | N/A |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Adults | Training for visiting new mothers | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Suicide prevention | Adults | Psychological intervention | 4 of 4 | 4 model studies |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Suicide prevention | Adults | CBT | 1 of 2 | 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Suicide prevention | Adults | Screening and psychological intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Suicide prevention | Adults | Workplace education | 0 of 1 | N/A |

| Le, 2021 [30] | General mental health | Adults | Psychological intervention | 4 of 5 | 2 RCTs, 1 non-RCT, 1 cross-sectional study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | General mental health | Adults | Screening | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Le, 2021 [30] | General mental health | Adults | Physical activity intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Eating disorders | Adults | Cognitive dissonance | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Eating disorders | Adults | Screening and psychological intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Eating disorders | Adults | Psychological intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Generalised anxiety disorder | Adults | CBT | 2 of 2 | 2 model studies |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Psychosis | Adults | CBT | 2 of 2 | 1 RCT, 1 model study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Panic disorder | Adults | CBT | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Substance abuse | Adults | Peer-based prevention programme | 1 of 1 | 1 retrospective ecological study |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Older adults | Psychological intervention | 2 of 3 | 2 RCTs |

| Le, 2021 [30] | Depression | Older adults | CBT | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Park 2013 [31] | Mental and substance abuse disorders | Adults | Integrated management programme | 0 of 3 | N/A |

| Park 2013 [31] | Sedentary behaviour | Adults | Primary care physical activity intervention | 2 of 2 | 2 RCTs |

| Park 2013 [31] | HIV | Adults | Small-group intervention | 1 of 2 | 1 model study |

| Park 2013 [31] | Blood-borne infectious diseases | Adults | Specialist brief programme | 0 of 2 | N/A |

| Park 2013 [31] | Mental health | Adults | Physical exercise programme | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Park 2013 [31] | Smoking cessation | Adults | Smoking cessation programme | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Soneson, 2020 [18] | Psychosis | Adolescents and adults | CBT | 1 of 2 | 1 RCT |

| Obesity | |||||

| Lehnert 2012 [32] | Obesity | Children | School curriculum programme | 0 of 1 | N/A |

| Lehnert 2012 [32] | Obesity | Children | Active after school programme | 0 of 2 | N/A |

| Lehnert 2012 [32] | Obesity | Children | Family-based GP-mediated intervention | 0 of 1 | N/A |

| Lehnert 2012 [32] | Obesity | Adults | Diet intervention | 3 of 4 | 3 model studies |

| Lehnert 2012 [32] | Obesity | Adults | Diet and exercise intervention | 0 of 3 | N/A |

| Lehnert 2012 [32] | Obesity | Adults | Diet and pharmacotherapy intervention | 0 of 3 | N/A |

| Lehnert 2012 [32] | Obesity | Adults | Diet, exercise, and behaviour modification intervention | 6 of 7 | 6 model studies |

| Lehnert 2012 [32] | Obesity | Adults | Community programme | 2 of 2 | 3 model studies |

| Lehnert 2012 [32] | Obesity | Adults | Physical activity | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Type 2 diabetes | |||||

| Glechner 2018 [33] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Lifestyle intervention | 10 of 13 | 5 model studies, |

| Glechner 2018 [33] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Pharmacotherapy | 8 of 10 | 4 model studies, 4 RCTs |

| Glechner 2018 [33] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Screening + lifestyle intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Glechner 2018 [33] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Pharmacotherapy + lifestyle intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Li 2015 [34] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Lifestyle intervention | 15 of 16 | 13 model studies, 2 RCTs |

| Li 2015 [34] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Pharmacotherapy | 7 of 8 | 5 model studies, 2 RCTs |

| Li 2015 [34] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Screening | 2 of 3 | 3 model studies |

| Li 2015 [34] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Primary care intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Li 2015 [34] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Dietary intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Zhou 2020 [35] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Lifestyle intervention | 17 of 20 | 11 model studies, 6 RCTs |

| Zhou 2020 [35] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Screening + lifestyle intervention | 4 of 7 | 4 model studies |

| Zhou 2020 [35] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Screening + pharmacotherapy | 2 of 2 | 2 model studies |

| Zhou 2020 [35] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Screening + physical activity intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Zhou 2020 [35] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Screening + diet intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Zhou 2020 [35] | Type 2 diabetes | Adults | Screening | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Dental caries | |||||

| Anopa 2020 [36] | Dental caries | Children | Multicomponent intervention | 8 of 10 | 4 model studies, 1 RCT, 1 cohort study, 2 non-RCTs |

| Anopa 2020 [36] | Dental caries | Children | Fluoride treatment | 3 of 4 | 1 model studies, 2 non-RCTs |

| Anopa 2020 [36] | Dental caries | Children | Molar sealant | 3 of 3 | 3 model studies |

| Anopa 2020 [36] | Dental caries | Children | Oral hygiene and diet education | 1 of 1 | 1 non-RCT |

| Fraihat 2019 [37] | Dental caries | Children | Multicomponent intervention | 5 of 7 | 2 model studies, 3 RCTs |

| Fraihat 2019 [37] | Dental caries | Children | Education | 1 of 4 | 1 model study |

| Fraihat 2019 [37] | Dental caries | Children | Teeth brushing | 2 of 3 | 1 model study, 1 RCT |

| Fraihat 2019 [37] | Dental caries | Children | Fluoride varnish | 1 of 3 | 1 RCT |

| Fraihat 2019 [37] | Dental caries | Children | Screening | 0 of 2 | N/A |

| Fraihat 2019 [37] | Dental caries | Children | Counselling | 0 of 1 | N/A |

| Public health | |||||

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Breastfeeding | Post-partum women | Breastfeeding promotion programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Post-natal depression | Post-partum women | Community-based support programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Behavioural problems | Parents and children | Behaviour management programme for parents/families | 4 of 4 | 4 case studies |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Substance misuse | Parents and children | Substance misuse programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | General health | Children | Childcare programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | General health | Children | School music programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Substance misuse | Adolescents | Substance misuse programme | 2 of 2 | 2 case studies |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Sexual health | Adolescents | Community programme for the prevention of teenage pregnancy | 2 of 2 | 2 case studies |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Behavioural problems | Adolescents | Sporting programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Behavioural problems | Adolescents | Community programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Mental health | Adults | Training and employment programme | 3 of 3 | 3 case studies |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Mental health | Adults | Education | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Mental health | Adults | Living assistance community programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | General health | Adults | Community family programme | 1 of 2 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Smoking | Adults | Smoking cessation programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Substance misuse | Adults | Substance misuse programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Mental health | Older adults | Creative arts programme | 4 of 4 | 4 case studies |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Mental health | Older adults | Home care programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Mental health | Older adults | Peer support groups | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | General health | Universal | Community programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | General health | Universal | Healthy eating programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Chronic disease | Universal | Lifestyle intervention | 2 of 2 | 2 case studies |

| Ashton 2020 [22] | Sedentary behaviour | Universal | Physical activity intervention | 3 of 3 | 3 case studies |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Post-natal depression | Post-partum women | Community programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Sexual health | Parents and children | Sexual health intervention | 2 of 2 | 2 case studies |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Chronic disease | Parents and children | Mobility equipment service | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Substance misuse | Parents and children | Support programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Asthma | Children | Community asthma programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Poor dietary behaviours | Children | School breakfast programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | General health | Children and adolescents | General healthcare intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Sexual health | Adolescents | Sexual health intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Mental health | Adults | Skills training and employment programme | 3 of 3 | 3 case studies |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Mental health | Adults | Clubhouse for mental health support | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Mental health | Adults | Mental health awareness training courses | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Mental health | Adults | Reading programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Suicide | Adults | Support programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Substance misuse | Adults | Recovery programme | 2 of 2 | 2 case studies |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Substance misuse | Adults | Self-management course | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Substance misuse | Adults | Skills training and employment | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Smoking | Adults | Smoking cessation policy | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Sedentary behaviour | Adults | Walking programme | 3 of 3 | 3 case studies |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | HIV | Adults | Stigma and discrimination training | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | HIV and AIDs | Adults | Football support programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Spinal cord injury | Adults | Community rehabilitation programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Chronic disease | Adults | Self-care training | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | General health | Adults | Integrated healthcare | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Poor nutrition | Older adults | Meals home delivery programme | 2 of 2 | 2 case studies |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Mental health | Older adults | Mental health support programme | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | General health and HIV | Universal | Community-based care and support | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | HIV and AIDS | Universal | Community-based care and support | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | HIV | Universal | Adherence to anti-retroviral therapies intervention | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | General health | Universal | Hospital-based services | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Environmental health | Universal | Household-based water treatment and safe storage | 1 of 1 | 1 case study |

| Banke-Thomas 2015 [38] | Chronic disease | Universal | Healthy lifestyle intervention | 2 of 2 | 2 case studies |

| Masters 2017 [21] | Smoking | Pregnant women | Smoking cessation programme | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Masters 2017 [21] | Influenza | Post-partum women | Influenza vaccination programme | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | Haemophilus influenzae type b | Children | Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccination programme | 2 of 2 | 2 model studies |

| Masters 2017 [21] | General health | Children | Early education programme | 2 of 2 | 1 RCT and 1 matched cohort study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | General health | Parents and children | Early education programme | 1 of 1 | 1 matched cohort study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | Child behaviour | Parents and children | Parenting programme | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | Environmental health | Children | Household lead paint hazard control | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | General health | Adolescents | Multisystematic therapy | 1 of 1 | 1 RCT |

| Masters 2017 [21] | Chronic disease | Adults | Workplace health promotion | 3 of 4 | 1 quasi experimental study, 1 pre–post study, 1 case study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | Chronic disease | Adults | Medication management | 2 of 2 | 1 controlled intervention study, 1 cohort matched control study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | Chronic disease | Adults | Prevention programme | 1 of 1 | 1 cohort matched control study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | Heart disease | Adults | Disease management programme | 1 of 1 | 1 cohort study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | Heart disease | Adults | Home blood pressure monitoring | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | Heart disease | Adults | Tobacco cessation | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | HIV | Adults | Needle and syringe programme | 4 of 4 | 3 model studies, 1 mixed methods study |

| Masters 2017 [21] | HIV | Adults | HIV testing | 1 of 1 | 1 model study |