Abstract

Introduction: The global rise of urbanization has much triggered scientific interest in how nature impacts on human health. Natural environments, such as alpine landscapes, forests, or urban green spaces, are potential high-impact health resources. While there is a growing body of evidence to reveal a positive influence of these natural environments on human health and well-being, further investigations guided by rigorous evidence-based medical research are very much needed. Objective: The present study protocol aims at testing research methodologies in the context of a prospective clinical trial on nature-based interventions. This shall improve the standards of medical research in human–nature interactions. Methods: The ANKER Study investigates the influence of two novel types of nature-based therapy—mountain hiking and forest therapy—on physiological, psychological, and immunological parameters of couples with a sedentary lifestyle. Two intervention groups were formed and spent a seven-day holiday in Algund, Italy. The “forest therapy group” participated in daily guided low-power nature connection activities. The “hiking group”, by contrast, joined in a daily moderate hiking program. Health-related quality of life and relationship quality are defined as primary outcomes. Secondary outcomes include nature connection, balance, cardio-respiratory fitness, fractional exhaled nitric oxide, body composition and skin hydration. Furthermore, a new approach to measure health-related quality of life is validated. The so-called “intercultural quality of life” comic assesses the health-related quality of life with a digitally animated comic-based tool.

1. Introduction

Over a whole lifetime, human health is dynamically affected by a plethora of external and internal factors. Following the Exposome concept, both external push factors and internal factors that are influenced directly or more indirectly by humans themselves play a seminal role in health development over time [1,2,3,4]. As has been shown elsewhere, genetic predisposition may affect the personal risk of developing chronic diseases by 10% [5]. This is a rather small factor in the present context. External or environmental factors, such as diet, exercise, place of residence, access to green space or climatic conditions, have been changing rapidly over the last centuries, leading to increasing numbers of non-communicable diseases [6]. Scientific evidence is growing that natural environments have a great potential for disease prevention and health promotion [7]. However, current research often lacks methodological quality and rarely meets state-of-the art criteria to assess the impact of natural environments as an external factor on human health and well-being [8].

How exactly and to what extent forests promote human health is currently only researched to a limited extent, although there is increasing evidence for a positive effect of forest therapies. This applies to both the physical, mental and social health of humans [9]. Schuh and Immich [10] find that forest therapies are particularly suitable for promoting the general health and act as stress reducers. Several studies on stress reduction through forest therapies show an increase in parasympathetic activity [11,12,13]. These play an important role in physical recovery and relaxation [14] but may also have a positive effect on blood pressure [15] and heart rate [16]. Furthermore, forest therapies can be used to mitigate known risk factors for cardiovascular diseases [17,18]. Respiratory diseases, such as COPD [19], depression [20], exhaustion [21] and sleep disorders [22], can also be positively influenced by forest-based interventions. Moreover, as evidenced, forests have positive effects on the immune system [11]. In general, more frequent and longer stays in forests have a stronger and more lasting effect than isolated and shorter visits [23]. However, a curative effect of forest stays on existing diseases has not been proven yet [10].

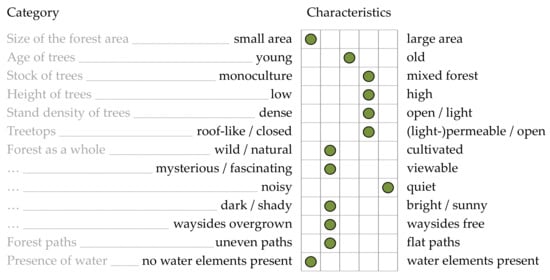

Overall, it can be said that, while there are numerous studies on health effects of forests, there is still much need for improved research conceptually, as well as methodologically [9]. Unfortunately, we have identified various studies on forest-based interventions with medium to poor quality and high risk of bias. Structural and methodological weaknesses in study design and reporting quality come with insufficient description of the intervention groups, reporting of confounding variables and missing or inadequate control group organizations [24]. Furthermore, most studies identified are performed in Asian countries with mostly healthy and young participants, thus limiting the generalizability of the results. The intervention duration is mostly rather short (1–3 days) without reporting long-term effects [25,26]. In addition, it must be taken into account that possible health effects of forests may be triggered by individual perceptions of forest visitors and thus by the setting of the forest itself [27]. Therefore, a homogenous assessment tool to characterize the forest itself would be particularly important. By structuring the numerous findings on the impact of forests, it is possible to derive a basic evaluation scheme for individual forest areas, which can be used as a comparative instrument between different study areas and, therefore, also contribute to the necessary improvement of the approach of the Exposome [8]. The characteristics of the forest or the trees can be divided into different categories, each with measurable indicators. These are:

- (1)

- Size of the forest area: Larger, more coherent forests increase well-being and can also be activity enhancing [28].

- (2)

- Age of trees: Older forests with large and mature trees increase well-being and positively contribute to recreational preferences [29].

- (3)

- Stock of trees: Mixed forests with deciduous and coniferous trees are perceived as more attractive than monocultures and thus increase well-being [30].

- (4)

- Height and structure of the trees: Higher trees increase well-being. In addition, different tree heights (levels of the treetops) are perceived as more attractive [27].

- (5)

- Stand density of the trees: Light forests with a rather low stand density of trees, and thus a higher incidence of light, increase well-being [10].

- (6)

- Characteristics of the treetops: A crown covering of about 75%, combined with sufficient light incidence, increases well-being [27].

- (7)

- Characteristics of the forest as a whole: Well-tended forests in the sense of managed forests (mood-lifting effect) [31] and a low proportion of dead wood, but at the same time, no excessive traces of lumbering [27], are preferred. In addition, the forests should be bright (orientation and safety), free of waste and noise [27].

- (8)

- Other vegetation: A varied, green-to-colorful vegetation (in addition to the trees), which is neither too dense nor too open, is generally preferred [14].

The effects of the forest floor can be described with the help of two categories: (1) “characteristics of the forest paths”; and (2) “characteristics of the forest floor”. Thus, the following statements and indicators can be derived from the literature:

- (1)

- Characteristics of the forest paths: Flat, easily walkable paths, as well as free waysides and thus easy orientation (wide view), increase well-being, as well as the recreational value [32].

- (2)

- Characteristics of the forest floor: An area-wide vegetation, which is not overgrown and essentially walkable, increases well-being [32].

Apart from the forest characteristics listed above, other natural and artificial elements impact on the well-being of forest visitors. Natural factors include the presence of water (e.g., creeks, rivers, lakes, waterfalls), natural resting places (e.g., moss, snags, meadows, mounds, clearings) and existing views or scenery [33]. Artificial elements include infrastructure, such as recreation areas (e.g., benches), the signage of the paths or possibilities for protection from the elements of nature (e.g., shelters). For infrastructural elements, suitable materials (e.g., wood and stone instead of plastic and metal) should be chosen, and an overloading of nature with artificial elements should be avoided [28,34,35]. Further, the issue of barrier-free access can also be important in the context of forest therapies [36].

Considering the multitude of indicators for the assessment of the forest as defined above, it can be assumed that not all factors classified as positive in the literature are always fulfilled or present. On the one hand, it is difficult to find the perfect forest area in terms of the listed criteria. On the other hand, numerous external factors, such as ownership or accessibility, also play an important role in the possible use of a forest area. In this respect, the forest area used is almost always a compromise solution between potential optimum and reality. It is therefore even more important to integrate the question of the actual effect of the forest setting into future studies. Thus, the forest as a natural space is also a factor that can have an influence on human health. Generally, the Exposome provides an interesting approach, especially for the health effects of our natural environment, which, in our view, requires intensified research and further methodological approaches [8].

Objectives and Trial Design

The present paper represents a protocol of a prospective clinical study assessing the effects of two different nature-based interventions on human health and well-being, following the SPIRIT guidelines [37]. The purpose is to improve the levels of methodological quality in nature-based therapy research meeting validity criteria of reproducibility by other research groups. It will thus contribute to improving the standards of medical research regarding nature-based interventions and contribute to a more solid body of evidence regarding the linkage between nature and human health and well-being.

The objective of the ANKER Study (“Algunder Nature and climate therapy: Green Exercise vs. Nature Connection”) is to analyze effects of two types of nature-based interventions—(1) Hiking and (2) Forest Therapy—in couples with a sedentary lifestyle on health-related quality of life, quality of relationship, and further psychological and physiological parameters are investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants, Interventions and Outcomes

2.1.1. Study Design

The ANKER Study was designed as a two-armed randomized controlled trial. It aimed at investigating the effects of moderate mountain hiking and forest therapy on couples with a sedentary lifestyle. Participants were assigned to two intervention groups: (1) a “hiking group”; and (2) a “forest therapy group”. Both groups spent a seven-day holiday in Algund, Italy, and participated in daily hiking or forest therapy activities. The study was carried out in two independent sequences but with the same intervention schedule. One half of the study population finished the ANKER Study in October 2019. The second study sequence was scheduled for April 2020, but due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, this part was only carried out in June 2021, when hotels in Algund re-opened, and a safe implementation was guaranteed.

2.1.2. Eligibility Criteria

The ANKER Study included couples with a sedentary lifestyle presenting the following demographics: age 50–60 years old, relationship duration >1 year, body mass index ≥25–≤30, sedentary lifestyle (International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form <3.00 METmin/week) and the ability to participate in moderate hiking tours (Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire). The following exclusion criteria were applied: active lifestyle, immunologically mediated chronic conditions or immunodeficiency, severe respiratory diseases, acute or untreated psychiatric disorders, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled metabolic disease, acute infection or fever, diagnosis of or treatment for malignant neoplastic disorders within the last 5 years, arteriosclerotic event <6 months before enrollment, cardiac insufficiency, renal insufficiency, diagnosis or history of alcoholism, current recreational drug use, currently smoking >10 cigarettes/day, orthopedic contraindications for hiking, medication intake >5mg/day prednisone, colchicine, imuran, methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide or cyclosporine, intake of weight-loss drugs or preparations and pregnancy.

For the second sequence of the study, all participants had to be fully vaccinated, recovered or regularly tested for COVID-19. Additionally, rapid COVID-19 antigen tests were performed at arrival. No study participant tested positive throughout the intervention.

2.1.3. Interventions

The participants of both intervention groups spent a seven-day-holiday in Algund (Italy, 46°40′57.5″ N 11°07′19.0″ E), located 350 m above sea level. The region is characterized by its mild, almost Mediterranean climate. All participants were hosted in local hotels and received the same meals. No lifestyle recommendations were given for any group during the non-intervention phase. The activity level of the participants during the intervention was controlled by heart rate monitors (Forerunner 25, Garmin, Olathe, KS, USA).

The hiking group participated in a daily moderate hiking program (Table 1), except for one rest day in the middle of the week. All tours were guided by mountain-hiking-coaches. The “nature group” participated each day in standardized Forest Therapy sessions for 3–4 h (Table 2), assisted by a psychologist. These were characterized by low physical activity. The Forest Therapy was guided by a holistic framework which fosters meaningful connections at three different levels: (1) connection with nature; (2) connection with others; and (3) connection with oneself. Each day was grouped under a certain theme, which is first presented, then discussed in depth and later supported by 3–5 exercises. The session was then ended with a written self-reflection to capture experiences, insights, and thoughts of the day.

Table 1.

Exercise program of the hiking group.

Table 2.

Thematic schedule of the nature group.

2.1.4. Outcomes

Data were collected before the start of the intervention (day 0; T1), after the intervention week (day 7; T2) and again after two (day 60; T3) and six months (day 180; T4) following the intervention. All medical examinations at T1 and T2 were carried out at the Department of Sports Medicine, Tappeiner Hospital Merano (Italy). Follow-up examinations at day 60 took place at the Paracelsus Medical University Salzburg (Austria). The follow-up examination at day 180 was conducted as an online survey. Short-term effects of a single hiking tour and forest therapy session were assessed at day 2 (T1.2, T1.3). Health-related quality of life and quality of relationship were set as primary outcomes. All interventions and assessments are represented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Participant timeline showing time schedule of enrollment, interventions and assessments of participants. Abbreviations: BMI—Body Mass Index, IPAQ-SF—International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form, FEGK—Questionnaire for the Collection of Health-Related Control Beliefs, VAS—Visual Analog Scale.

Primary Outcomes

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) was assessed at T1–T4 by the short-form health survey (SF12) and the EuroQol (EQ-5D). The SF12 covers health-related quality of life across the two main dimensions of physical and mental health, as well as a total score [42]. The EQ5D consists of two parts—a descriptive self-assessment in five dimensions, resulting in a health profile index (EQ-5DIndex), and a visual analog scale (EQ-5D-VAS) on which the respondent estimates their current state of health in a range of 0 (worst possible health status) to 100 (best possible health status) [43].

In addition to these well-established HRQOL questionnaires, a novel approach to measure HRQOL was used: the intercultural quality of life comic (iQOLC). Developed by the Institute of Ecomedicine at the Paracelsus Medical University Salzburg, the tool assesses HRQOL with a digitally animated comic-based application. It covers 16 items that are rated on a linear scale. The result of each item is displayed in the value range of 1 to 100, whereas higher values represent a better health status.

The iQOLC is still in the development process. The long-term goal of the iQOLC development is to generate a graphics-based application to validly assess generic health-related quality of life regardless of language, culture and educational background. In addition, disease-specific extensions to the tool are being considered. Within the ANKER Study, the current version of the iQOLC, accessible via www.winterhealth.eu, will be psychometrically validated in the described sedentary population sample, planned as the first step of a comprehensive validation process.

Quality of relationship was evaluated at T1–T4 by the Partnership Questionnaire and the Problem List, which are part of the Partner Diagnostics Questionnaire [44]. The Partnership Questionnaire consists of 30 items, from which three scales (dispute behavior, tenderness and commonality/communication), as well as an overall score, can be formed. Finally, a six-step single item records how unhappy or happy the person currently assesses his/her relationship to be. The Problem List covers 23 problem areas.

Secondary Outcomes—Questionnaires

Nature connectedness was assessed at T1–T4 by the Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) and the Nature Relatedness Scale (NRS). The CNS captures the connection with nature with 13 items, which are rated from 1 = “does not apply” to 5 = “applies”. Higher values mean a higher attachment to nature [45]. The NRS assesses closeness to nature over 21 items, which are rated on a scale of 1 = “do not agree” up to 5 = “agree fully”, with higher values indicating a higher closeness to nature [46].

Socio-psychological well-being in the sense of flourishing of personality was measured at T1–T4 by the German version of the Flourishing Scale (FS-D). The FS-D consists of eight items, which are answered on a seven-step scale from “I fully agree” to “I absolutely do not agree”. Higher values mean higher socio-psychological well-being [47].

The “Satisfaction with Life Scale” (SWLS) is a one-dimensional questionnaire for recording life satisfaction and was handed out for completion at T1–T4. The SWLS consists out of five items, which are answered on a seven-level Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 5 (lowest satisfaction) to 35 (highest satisfaction). It is standardized for a German population [48].

“Subjective impairment” of the participants was assessed at T1–T4 by the complaints list (B-L’). Each item on the B-L’ is rated on a physio scale from 0 = “not at all” to 3 = “strong” [49].

Mindfulness was recorded by the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS). The MAAS comprises 15 items, which are queried on a six-stage scale from 1 = “almost always” to 6 = “almost never”. Higher levels indicate higher levels of mindfulness [50].

The immediate effects of a single hiking/forest therapy session were assessed at day 2 by the “Feeling Scale” (FS), “Felt Arousal Scale” (FAS) and “Mood Scale” (Bf-SR). The FS is a bipolar single-item scale ranging from −5 = “very bad” to 0 = “neutral” to + 5 = “very good” to assess a participant’s pleasure [51]. The FAS is also a single-item scale on which participants rate their level of activation between 1 (low arousal) and 6 (high arousal) [52]. The Bf-SR assesses the current mental state over 24 items, by rating contrary adjectives on a five-point Likert scale [53].

The five personality traits of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, tolerability/agreeableness and neuroticism were assessed at T1–T5 by the BFI-10 questionnaire. Each of the dimensions is rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “applies fully” [54].

Health locus of control was assessed by the German short version of the questionnaire for the collection of health-related control beliefs (FEGK). The FEGK consists of 10 items, which are answered on a six-point scale with the extreme poles “very correct” to “very wrong” [55]. The latter two (BFI-10, Health locus control) are mainly used for the purpose of assessing discriminant validity of the iQOLC.

Secondary Outcomes—Physiological Parameter

Static balance was assessed at T1–T3 by MFT-S3 Check (Bodywork, Trend Sport Trading GmbH, Großhöflein, Austria). Participants are asked to enter a labile balance disc and are instructed to keep the disc centered. Within two measurement cycles, stability, symmetry and sensorimotor function will be assessed. Balance scores are reported as percent of predicted, based on normative data [56].

“Body composition” was measured at T1–T3 by a four-terminal impedance analyzer (BIA-101, RJL Systems; Detroit, Detroit, MI, USA) with two electrodes fixed on the right hand and the other two on the right foot, according to the standard procedure described elsewhere [57]. Data analysis will be performed by Bodygram PLUS software (Akern S.r.l; Pontassieve, Italy). The following parameter will be evaluated: total body water (l), fat mass index (kg/m2), fat-free mass index (kg/m2), body cell mass index (kg/m2), muscle mass index (kg/m2) and appendicular muscle mass index (kg/m2).

At T1–T3, 12 ml of forearm venous blood was collected in tubes (Vacuette®, Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Austria) according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Serum and plasma samples were stored at minus 80 °C until analysis. Differential blood counts were performed by the Laboratory for Chemical-Clinical Analysis and Microbiology, Tappeiner Hospital Merano (Italy) for T1 and T2, and the University Institute for Medical and Chemical Laboratory Diagnostics of the Paracelsus Medical University Salzburg (Salzburg, Austria) for T3.

“Fractional exhaled nitric oxide” was measured by NioxMino® (Aerocrine AB, Sweden) according to the ATS/ERS guidelines at T1 and T2 [58]. To assess the immediate effects of the interventions, additional fractional exhaled nitric oxide measurements were performed before and after a single hiking/forest therapy session on day 2.

“Anthropometric measures” (height, weight, waist and hip circumference) were performed according to the WHO guidelines [59]. “Height” was measured by a wall-mounted stadiometer. BMI and waist–hip ratio were calculated.

The “Chester step test” was used to assess aerobic fitness at T1–T3. During Chester step test, participants are asked to step on and off a low step at a defined rate, which is set by a metronome. Every two minutes, the heart rate and exertion level are recorded. The test continues until the participant reaches 80% of its maximum predicted heart rate [60]. Before and after the step test, the peak expiratory flow is measured in triplicates by a peak flow meter (Mini-Wright peak flow meter), and the best value is recorded.

Transepithelial water loss was measured by a Tewameter® TM 300 (Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH, Köln, Germany) at T1–T3. Skin hydration was measured by a Corneometer® CM 825 (Courage + Khazaka electronic GmbH, Köln, Germany) at T1–T3.

Environmental Monitoring

In addition to personal data, environmental parameters, such as particulate matter, volatile organic compounds or microbiome profiles, are also collected as part of the study. Environmental parameters were measured at the forest therapy site, at a selected point of the hiking tours, and at a control site at the city of Meran. Air quality, including particulate matter 1 µg/m3, 2.5 µg/m3, 10 µg/m3 and volatile organic compounds, was measured by a portable air quality monitor (Atmotube PRO, Atmotech Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA). The radon concentration was measured with a Radon/Thoron Monitor 1688 (SARAD GmbH, Dresden, Germany). Nanoparticles were measured with a multimeric nanoparticle detector (Partector 2, naneos particle solutions gmbh, Windisch, Switzerland). The density of air ions was measured by an air ion counter (AIC2, AlphaLab Inc., Salt Lake City, UT, USA). Furthermore, microbiome samples were collected with sterile swabs and an air sampler (Coriolis Compact, Bertin Technologies SAS, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France).

Finally, an evaluation of the forest described in the Introduction was carried out. An example of such a forest profile is given below (Figure 1). The survey form for assessing a forest can be found in full length in the Appendix A (see Table A1). The presented study protocol will focus mostly on human–nature interaction.

Figure 1.

Exemplary forest profile based on presented evaluation approach (Source: own illustration).

2.1.5. Sample Size

Sample size was estimated using health-related quality of life data from a former intervention study [61] (ISRCTN18092043). The sample size for the study was approximated with the statistical packages G*Power (G*Power Ver. 3.0.10, Franz Faul, Universität Kiel, Germany). The sample size was estimated for an ANOVA with fixed effects, special effects, main effects and interactions with the following input parameters: effect size f = 0.38, type I error α = 0.05, power 1-β = 0.85, number of groups = 2, degree of freedom = 2. The required sample size for getting a power of at least 85% was estimated to be 39 persons per group.

2.1.6. Recruitment

Participants were recruited via a webpage (https://www.klimatherapie.eu/, accessed on 22 January 2021) and advertisements posted on social media channels. An eligibility check was designed as a two-step process: in a preliminary online form, sociodemographic data (age, relationship status), BMI and activity level were (International Physical Activity Questionnaire—Short Form, two questions) assessed. Eligible persons were invited to fill out a second online form, which evaluated general health status (PHQ-9), nature connectedness (NRS-6) and physical activity readiness (PAR-Q).

2.2. Assignment of Interventions

Randomization was performed by an open-source add-in (Daniel’s XL Toolbox, Ver. 7.2.7) for the Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet software in blocks of two (pairwise allocation of couples), with age, general health status (PHQ-9), nature relatedness (NRS-6), BMI, activity level (IPAQ-SF) and relationship duration as allocation criteria [62]. As allocation method, the Kullback–Leibler divergence method was used. During randomization, patient data were anonymized by sequential numbers. Assignment to the interventions was communicated at day 0 after baseline examinations. Recruitment, eligibility check and assignment of participants to the interventions were performed by the same research scientist. Sequence generation, randomization and all following statistical analyses were performed by independent research scientists. Due to the intervention type, no blinding was planned.

2.3. Data Collection, Management, and Analysis

2.3.1. Data Collection Methods

Trained research scientists collected all data. Once a subject was enrolled for the ANKER Study, the researchers made every effort to avoid possible sample loss. Questionnaires at T0–T2 were paper–pencil-based and were digitalized by trained research scientists. Questionnaires at T3 were based on an online survey tool. To avoid missing data points, all answers were set as mandatory. No further data were collected from participants who were excluded from the study.

2.3.2. Data Management

Data were anonymized by four-digit ID numbers. The master list, which contains the assignment of the IDs to the personal data, is stored on a data server of the Paracelsus Medical University Salzburg (Austria) and is only accessible to the research scientist in charge of recruitment, eligibility check and assignment. Data from medical examinations and surveys are stored in spreadsheet files. Only authorized researchers have access to the data. Participants can access their personal data after completing the study.

2.3.3. Statistical Methods

Analyses were performed in accordance with the intention-to-treat principles, and the reporting adheres to the CONSORT statement, including CONSORT flow chart [63]. All statistical analyses were executed using the R-GNU software environment (General Public License, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set at the level of a <0.05 for all tests. Randomly missing values were replaced using the standard procedure, last outcome carried forward. The Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to check for normal distribution. Depending on data distribution, parametric or non-parametric tests were be applied. Participant data were compared in terms of baseline data, including outcome variables, as well as demographics (unpaired Student’s T-test or Wilcoxon test). Changes over time and between the interventions were either analyzed by linear mixed models or F1-LD-F1 models from the nparLD package [64]. In both cases group, time and group*time interaction effects were assessed. Furthermore, a post hoc sample size calculation based on bootstrap simulation was performed [65].

Psychometric analysis of the iQOLC was performed to test reliability, validity and responsiveness to change. To examine the fit of the assumed three-factor structure of the iQOLC (physical, psychological and social health), a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted, and the following model fit indices were calculated: chi-square, root mean square error of approximation, standardized root mean square residual and comparative fit index.

2.4. Monitoring

During all phases of the ANKER Study, the study coordinator supervised the study. In regular performance audits, the entire research team ensured that all participants met the inclusion criteria and that all performed the activities proposed by the study protocol. No data monitoring committee was installed. No interim analyses were performed. Although clinical evaluations and the planned hiking/forest therapy program are considered as having a low personal risk, adverse events would have been monitored and recorded by the researchers and reported to the research coordinator of the study and to the Ethics Committee of Bolzano, Italy.

2.5. Ethics and Dissemination

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bolzano (Comprensorio Sanitario di Bolzano, reference number: 18–2019, date of approval 2019/03/13). In the case of study protocol modifications, the approval of the Ethics Committee would have been sought immediately. Any changes were communicated to the participants and trial registry. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment by the researcher in charge of recruitment and eligibility check. All employees pledged confidentiality with their signature. The master list containing the assignment of the IDs to the personal data was accessible to authorized persons only. All statistical analyses were performed with anonymized data. In all publications and presentations, the personal data of individuals were not traceable. Trial data and documents from the ANKER Study were stored in the archives of the Paracelsus Medical University Salzburg, Institute of Ecomedicine, Austria, and will be made available on request after publication. The results of this protocol study will be published in peer-reviewed journals, as well as at national and international conferences. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

3. Discussion

The 21st century is characterized by a rapid growth of urban agglomerations, signified by externally structured and everyday life organizations in gray, geometric environments. This has led to the rediscovery of the forest as a “healing resource” for urban society. Forests promise peace, orientation, freedom, deceleration and fulfill our longing for authentic nature experience. Forests reduce stress outside of everyday life [66].

Given improvements to the validity of studies on Exposome and to the effects of individual external factors on human health, especially to natural factors, such as forests, such effects can be much better integrated into public health policies. To this purpose, this paper provides a variety of approaches, which address important research gaps. Certainly, these need to be examined in much more detail in the future.

The most important aspect relates to the selection of health outcome parameters of nature-based clinical intervention trials. Most studies in forest therapy put their research focus on surrogate parameters, such as natural killer cells count and activity or (short-term) reduced blood pressure and stress hormones [67]. An improvement of these parameters may only suggest a potential preventive health effect, but it does not show a clinically significant patient benefit. On the other hand, the selected primary outcomes of the ANKER Study (health-related quality of life, relationship quality) represent patient-centered clinical endpoints, thus indicating clinically meaningful changes and a direct patient benefit [68]. As a corollary, the ANKER Study also takes into account the emerging necessity of considering humans as integrated, feeling and active beings and not simply as biological organisms [69]. Moreover, it points to the demand for a stronger integration of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials [70].

Another aspect concerns the role of the control group. The intention of the control group should not be to achieve the greatest possible difference in health effects. To extract the specific influence of a forest on human health, the control group must be carried out in the same spatial setting, namely the forest. This is the only way to come closer to the actual impact of forests on human health. In this respect, the authors propose to use the survey questionnaire used here to determine the forest setting in future studies. Furthermore, this will leverage the comparability of studies. Ultimately, it will help in determining the actual influence of forests and the conducted activities on health.

Only when a more precise picture of the health effects of forests together with corresponding activities emerges can forests be seriously and reasonably used in a medical sense. Additionally, only then does it make sense, from the authors’ point of view, to assign a specific health function to individual forest areas, as already practiced in, for example, so-called “healing forests” [71].

In this context, the findings on the health effects of forests can be used, for example, to increase the general importance of nature-based health prevention. On the one hand, evidence-based health benefits of forests could become more important for individual health prevention and thus also help reduce the pressure on the public health care system [72]. On the other hand, such an approach can also be seen as a direct extension of a public health care system, which integrates prevention as an important factor of human health [73]. In this context forests play a special role as one of many natural healing resources, since forest areas, in contrast to waterfalls, for example, are more frequently available and thus more easily accessible by a large part of the population. For example, almost one-third of the world’s land mass is covered by forests, which corresponds to about 0.5 hectares of forest per capita [74]. Of course, there is a relatively strong inequality of distribution. However, if we consider only forests within the European Union, where the best conditions for such an approach probably exist in the form of public health systems, and where the proportion of forest areas even exceeds 40%, this inequality almost completely disappears [75].

Another benefit can be seen in the opportunities to develop nature-based health tourism offers that provide a proven, evidence-based, added health value. Thereby, the fundamental demand for nature experiences can be loaded with the added value of a higher medical evidence. This, again, perfectly fits with the current trend of an increased health consciousness in society [76]. When combined with other trends in tourism, such as the search for more regionality and more authenticity, and thus for more resonance experiences [77], innovative and market-oriented products can be created.

4. Conclusions

This paper shows that further analyses of the health impact of forests is much needed, particularly regarding a more rigorous analysis of different natural areas and natural resources and of their possible integration into existing public health care systems. The example of Algund shows that health effects of nature are becoming more and more relevant for public authorities. Additionally, one can assume that the initial implementation of such an approach at community level would be less difficult than at national or EU level. Nevertheless, such projects should be realized on different levels in the future and, at best, should also be funded by the public sector. Ultimately, this study reveals that transdisciplinary research projects do not only offer high added value for scientific research and the regions involved as partners, but that essential transfers are achieved for society at large.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and C.P.; methodology, A.H., C.P. and J.F.; investigation, A.H., C.P., J.F., M.B., R.W.-E., G.S. and M.K.; resources, G.S. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P., J.F., M.B. and D.H.; writing—review and editing, R.W.-E., D.H., M.K., G.S., A.H. and P.C.M.; visualization, M.B. and J.F.; supervision, A.H.; project administration, A.H., C.P. and R.W.-E.; funding acquisition: A.H. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Tourism Association of Algund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Bolzano, Italy (ref.: 18-2019; 13.03.2019). This article corresponds to the SPIRIT 2013 Statement. The study was registered at ISRCTN43292449.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Tourism Association of Algund for their great support during the preparation and implementation of the ANKER Study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| BFI-10 | 10 Item Big Five Inventory |

| Bf-SR | Mood Scale |

| BIA | Bio Impedance Analysis |

| B-L’ | Complaints List |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CNS | Connectedness to Nature Scale |

| EQ-5D | Euro Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| FAS | Felt Arousal Scale |

| FEGK | Questionnaire for the Collection of Health-Related Control Beliefs |

| FS | Feeling Scale |

| FS-D | German Version of the Flourishing Scale |

| HRQOL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| IPAQ-SF | International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form |

| iQOLC | Intercultural Quality of Life Comic |

| MAAS | Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale |

| nparLD | Nonparametric Longitudinal Data Analysis |

| NRS-6 | Nature Relatedness Scale 6 |

| PAR-Q | Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire |

| PFB | Partnership Questionnaire |

| PFD | Partner Diagnostics Questionnaire |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| PL | Problem List |

| SF-12 | Short Form Health Survey |

| SWLS | Satisfaction with Life Scale |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Survey form for the forest profile.

Table A1.

Survey form for the forest profile.

| Scheme 1. | Filled by: | |||||

| Date: | Weather: | |||||

| Location/forest: | Route: | |||||

| Duration: | Distance in km: | Altitude in m: | ||||

| Scale explanation | ||||||

| ||||||

| Guidance* Characteristic X | 1 = is fully true | 2 = rather true | 3 = partially | 4 = rather true | 5 = is fully true | Guidance* Characteristic Y |

| Characteristics forest/trees | ||||||

| <200 hectares | Size of the forest area | >1000 hectares | ||||

| small area | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | large area |

| <10 years | Age of trees | >50 years | ||||

| young | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | old |

| Stock of trees | ||||||

| monoculture | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Mixed forest |

| <5 meters | High and structure of the trees | >20 meters | ||||

| low | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | high |

| single stage | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | multistage |

| Stand density of the trees | ||||||

| dense | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | open/light |

| Structure of treetops | ||||||

| low-hanging | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | high |

| not sprawling | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | sprawling |

| roof-like/closed | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | (light-)perme-able/open |

| Forest as a whole | ||||||

| wild/natural | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | cultivated |

| mysterious/fascinating | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | viewable |

| relaxing | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | stimulating |

| cool | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | warm |

| dirty (garbage) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | clean (garbage) |

| loud | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | quiet |

| lonely | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | full/socially connecting |

| unsafe | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | safe |

| dark/shady | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | bright/sunny |

| Other vegetation | ||||||

| monotonous | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | biodiverse |

| colorless | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | colorful |

| Survey form forest (2/2) | ||||||

| Scale explanation | ||||||

| ||||||

| Characteristic X | 1 = is fully true | 2 = rather true | 3 = partially | 4 = rather true | 5 = is fully true | Characteristic Y |

| Characteristics forest paths/forest floor | ||||||

| Condition/structure forest paths | ||||||

| waysides overgrown | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | waysides free |

| slim | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | wide |

| twisty | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | straight |

| plain | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | steep |

| uneven | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | flat |

| hard | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | soft |

| designed | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | natural |

| Condition/structure forest floor | ||||||

| bare | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | overgrown |

| impassable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | accessible |

| Other characteristics of the forest | ||||||

| no water elements *1 present | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Water elements present |

| no views/sceneries present | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | views/sceneries present |

| no natural resting places *2 present | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | natural resting places present |

| not barrier-free | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | barrier-free |

* Guidance is provided in a few cases for orientation purposes. Essentially, however, it is a rather subjective evaluation in the sense of “What applies predominantly to the forest?”. *1 Water elements: creek, river, lake, waterfall, etc. *2 Natural resting places: Moss, tree stumps, meadows, hills/clearings, etc.

References

- Wild, C.P. Complementing the Genome with an “Exposome”: The Outstanding Challenge of Environmental Exposure Measurement in Molecular Epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 1847–1850. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, C.P. The Exposome: From Concept to Utility. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rappaport, S.M.; Smith, M.T. Environment and Disease Risks. Science 2010, 330, 460–461. [Google Scholar]

- Dagnino, S.; Macherone, A. (Eds.) Unraveling the Exposome: A Practical View; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-89320-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, S.M. Implications of the Exposome for Exposure Science. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2011, 21, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frumkin, H.; Haines, A. Global Environmental Change and Noncommunicable Disease Risks. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gladwell, V.F.; Brown, D.K.; Wood, C.; Sandercock, G.R.; Barton, J.L. The Great Outdoors: How a Green Exercise Environment Can Benefit All. Extrem. Physiol. Med. 2013, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vrijheid, M. The Exposome: A New Paradigm to Study the Impact of Environment on Health. Thorax 2014, 69, 876–878. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, B.; Lee, K.J.; Zaslawski, C.; Yeung, A.; Rosenthal, D.; Larkey, L.; Back, M. Health and Well-Being Benefits of Spending Time in Forests: Systematic Review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2017, 22, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Schuh, A.; Immich, G. Waldtherapie—Das Potential des Waldes für Ihre Gesundheit; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-662-59025-6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. Shinrin-Yoku: The Art and Science of Forest Bathing; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-241-34695-2. [Google Scholar]

- Karjalainen, E.; Sarjala, T.; Raitio, H. Promoting Human Health through Forests: Overview and Major Challenges. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, W.S.; Yeoun, P.S.; Yoo, R.W.; Shin, C.S. Forest Experience and Psychological Health Benefits: The State of the Art and Future Prospect in Korea. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Corazon, S.S.; Sidenius, U.; Refshauge, A.D.; Grahn, P. Forest Design for Mental Health Promotion—Using Perceived Sensory Dimensions to Elicit Restorative Responses. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 160, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, G.-X.; Cao, Y.-B.; Lan, X.-G.; He, Z.-H.; Chen, Z.-M.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Hu, X.-L.; Lv, Y.-D.; Wang, G.-F.; Yan, J. Therapeutic Effect of Forest Bathing on Human Hypertension in the Elderly. J. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological Effect of Olfactory Stimulation by Hinoki Cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa) Leaf Oil. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2015, 34, 44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mao, G.X.; Cao, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, S.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Xing, W.; Ren, X.; Lv, X.; Dong, J.; et al. The Salutary Influence of Forest Bathing on Elderly Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 368. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, G.X.; Cao, Y.B.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.M.; Dong, J.H.; Chen, S.S.; Wu, Q.; Lyu, X.L.; Jia, B.B.; Yan, J.; et al. Additive Benefits of Twice Forest Bathing Trips in Elderly Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Biomed. Environ. Sci. BES 2018, 31, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jia, B.B.; Yang, Z.X.; Mao, G.X.; Lyu, Y.D.; Wen, X.L.; Xu, W.H.; Lyu, X.L.; Cao, Y.B.; Wang, G.F. Health Effect of Forest Bathing Trip on Elderly Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Biomed. Environ. Sci. BES 2016, 29, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shin, W.S.; Shin, C.S.; Yeoun, P.S. The Influence of Forest Therapy Camp on Depression in Alcoholics. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2012, 17, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag-Öström, E.; Nordin, M.; Dolling, A.; Lundell, Y.; Nilsson, L.; Slunga Järvholm, L. Can Rehabilitation in Boreal Forests Help Recovery from Exhaustion Disorder? The Randomised Clinical Trial ForRest. Scand. J. For. Res. 2015, 30, 732–748. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, E.; Imai, M.; Okawa, M.; Miyaura, T.; Miyazaki, S. A before and after Comparison of the Effects of Forest Walking on the Sleep of a Community-Based Sample of People with Sleep Complaints. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2011, 5, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, M.; van Poppel, M.; Smith, G.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Andrusaityte, S.; van Kamp, I.; van Mechelen, W.; Gidlow, C.; Gražulevičiene, R.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; et al. Does Time Spent on Visits to Green Space Mediate the Associations between the Level of Residential Greenness and Mental Health? Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 25, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Stier-Jarmer, M.; Throner, V.; Kirschneck, M.; Immich, G.; Frisch, D.; Schuh, A. The Psychological and Physical Effects of Forests on Human Health: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R.; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wen, Y.; Yan, Q.; Pan, Y.; Gu, X.; Liu, Y. Medical Empirical Research on Forest Bathing (Shinrin-Yoku): A Systematic Review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cervinka, R.; Höltge, J.; Pirgie, L.; Schwab, M.; Sudkamp, J.; Haluza, D.; Arnberger, A.; Eder, R.; Ebenberger, M. Zur Gesundheitswirkung von Waldlandschaften: Green Public Health—Benefits of Woodland on Human Health and Well-Being; BFW-Berichte; Bundesforschungszentrum für Wald: Wien, Austria, 2014; ISBN 978-3-7001-6098-4. [Google Scholar]

- Marušáková, Ľ.; Sallmannshofer, M. Human Health and Sustainable Forest Management; Forest Europe: Zvolen, Slovakia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, D.M.; Jay, M.; Jensen, F.S.; Lucas, B.; Marzano, M.; Montagné, C.; Peace, A.; Weiss, G. Public Preferences Across Europe for Different Forest Stand Types as Sites for Recreation. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, art27. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, A. Wahrnehmung von Wald und Natur; vs. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2000; ISBN 978-3-8100-2583-8. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, D.; Gutscher, H.; Bauer, N. Walking in “Wild” and “Tended” Urban Forests: The Impact on Psychological Well-Being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, T.R.; Kirk, K.M. Pathway Curvature and Border Visibility as Predictors of Preference and Danger in Forest Settings. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 620–639. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, A.R.; Bradley, G.A. The Effects of Viewer Attributes on Preference for Forest Scenes: Contributions of Attitudes, Knowledge, Demographic Factors, and Stakeholder Group Membership. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 147–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.B.; Heyman, E.; Richnau, G. Liked, Disliked and Unseen Forest Attributes: Relation to Modes of Viewing and Cognitive Constructs. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 113, 456–466. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; Wiley: Chichester, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-471-96233-5. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.; O’Brien, E.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Lawrence, A.; Carter, C.; Peace, A. Access for All? Barriers to Accessing Woodlands and Forests in Britain. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.-W.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Altman, D.G.; Laupacis, A.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Krleža-Jerić, K.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Mann, H.; Dickersin, K.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. SPIRIT 2013 Statement: Defining Standard Protocol Items for Clinical Trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berto, R. The Role of Nature in Coping with Psycho-Physiological Stress: A Literature Review on Restorativeness. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schutte, N.S.; Malouff, J.M. Mindfulness and Connectedness to Nature: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 127, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. Complementary and Integrative Treatments in Psychiatric Practice. Available online: https://www.appi.org/complementary_and_integrative_treatments_in_psychiatric_practice (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D. Reflective Self-Attention: A More Stable Predictor of Connection to Nature Than Mindful Attention. Ecopsychology 2015, 7, 166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, M.A.; Morfeld, M.; Glaesmer, H.; Brähler, E. Normierung Des SF-12 Version 2.0 Zur Messung Der Gesundheitsbezogenen Lebensqualität in Einer Deutschen Bevölkerungsrepräsentativen Stichprobe. Diagnostica 2018, 64, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.; Graf von der Schulenburg, J.-M.; Greiner, W. German Value Set for the EQ-5D-5L. PharmacoEconomics 2018, 36, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meuwly, N.; Schoebi, D.; Bierhoff, H.-W. TBS-TK Rezension: Fragebogen Zur Partnerschaftsdiagnostik (FPD; 2., Neu Normierte Und Erweiterte Auflage). Psychol. Rundsch. 2018, 69, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.; Frantz, C. The Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Individuals’ Feeling in Community with Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M. The NR-6: A New Brief Measure of Nature Relatedness. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esch, T.; Jose, G.; Gimpel, C.; Scheidt, C.; Michalsen, A. Die Flourishing Scale (FS) von Diener et al. Liegt Jetzt in Einer Autorisierten Deutschen Fassung (FS-D) Vor: Einsatz Bei Einer Mind-Body-Medizinischen Fragestellung. Forsch. Komplementärmedizin 2006 2013, 20, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaesmer, H.; Grande, G.; Braehler, E.; Roth, M. The German Version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS): Psychometric Properties, Validity, and Population-Based Norms. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2011, 27, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B-LR—Beschwerden-Liste. Revidierte Fassung—Hogrefe Verlag. Available online: https://www.testzentrale.de/shop/beschwerden-liste-revidierte-fassung.html (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Michalak, J.; Heidenreich, T.; Ströhle, G.; Nachtigall, C. Die Deutsche Version Der Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS) Psychometrische Befunde Zu Einem Achtsamkeitsfragebogen. Z. Für Klin. Psychol. Psychother. 2008, 37, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, C.J.; Rejeski, W.J. Not What, but How One Feels: The Measurement of Affect during Exercise. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1989, 11, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svebak, S.; Murgatroyd, S. Metamotivational Dominance: A Multimethod Validation of Reversal Theory Constructs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Zerssen, D.; Petermann, F. Die Befindlichkeits-Skala: Revidierte Fassung; Manual; Hogrefe Verlag: Göttingen, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rammstedt, B.; Kemper, C.J.; Klein, M.C.; Beierlein, C.; Kovaleva, A. A Short Scale for Assessing the Big Five Dimensions of Personality: 10 Item Big Five Inventory (BFI-10). Methods Data Anal. 2013, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferring, D. Forschungsbericht Zum “Fragebogen Zur Erfassung Gesundheitsbezogener Kontrollüberzeugungen” (FEGK); University of Luxembourg: Luxembourg, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raschner, C.; Lembert, S.; Platzer, H.-P.; Patterson, C.; Hilden, T.; Lutz, M. S3-Check—evaluation and generation of normal values of a test for balance ability and postural stability. Sportverletz. Sportschaden Organ Ges. Orthop. Traumatol. Sportmed. 2008, 22, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaski, H.C.; Bolonchuk, W.W.; Hall, C.B.; Siders, W.A. Validation of Tetrapolar Bioelectrical Impedance Method to Assess Human Body Composition. J. Appl. Physiol. 1986, 60, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. ATS/ERS Recommendations for Standardized Procedures for the Online and Offline Measurement of Exhaled Lower Respiratory Nitric Oxide and Nasal Nitric Oxide, 2005. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 171, 912–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO STEPS Surveillance Manual: The WHO STEPwise Approach to Chronic Disease Risk Factor Surveillance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; ISBN 978-92-4-159383-0. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, J.P.; Sim, J.; Eston, R.G.; Hession, R.; Fox, R. Reliability and Validity of Measures Taken during the Chester Step Test to Predict Aerobic Power and to Prescribe Aerobic Exercise. Br. J. Sports Med. 2004, 38, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Prossegger, J.; Huber, D.; Grafetstätter, C.; Pichler, C.; Weisböck-Erdheim, R.; Iglseder, B.; Wewerka, G.; Hartl, A. Effects of Moderate Mountain Hiking and Balneotherapy on Community-Dwelling Older People: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 122, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, D. Consolidated Data Analysis and Presentation Using an Open-Source Add-in for the Microsoft Excel® Spreadsheet Software. Med. Writ. 2014, 23, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Parallel Group Randomised Trials. BMJ 2010, 11, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, K.; Gel, Y.R.; Brunner, E.; Konietschke, F. NparLD: An R Software Package for the Nonparametric Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Factorial Experiments. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 50, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lunneborg, C.E. Bootstrap Applications for the Behavioral Sciences. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1987, 47, 627–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochner, A. Naturzeit Wald Was er uns Schenkt, Wie Wir Ihn Prägen; Kosmos Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-440-50189-4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. Effect of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on human health: A review of the literature. Sante Publique Vandoeuvre Nancy Fr. 2019, S1, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiteni, F.; Westeel, V.; Pivot, X.; Borg, C.; Vernerey, D.; Bonnetain, F. Endpoints in Cancer Clinical Trials. J. Visc. Surg. 2014, 151, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Buiting, H.M.; Olthuis, G. Importance of Quality-of-Life Measurement Throughout the Disease Course. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e200388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mercieca-Bebber, R.; King, M.T.; Calvert, M.J.; Stockler, M.R.; Friedlander, M. The Importance of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Clinical Trials and Strategies for Future Optimization. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2018, 9, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corazon, S.; Stigsdotter, U.; Claudi Jensen, A.G.; Nilsson, K. Development of the Nature-Based Therapy Concept for Patients with Stress-Related Illness at the Danish Healing Forest Garden Nacadia. J. Hortic 2010, 20, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Michalsen, A. Natur als Therapie und Prävention. Z. für Komplementärmedizin 2020, 12, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bock, F.; Dietrich, M.; Rehfuess, E. Evidenzbasierte Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung. Memo. Bundeszentrale Gesundh. Aufklärung (BZgA) 2020, 1.0, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-132974-0.

- Eurostat Anteil Der Waldfläche. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sdg_15_10/default/table?lang=de (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Hoffmann, S. (Ed.) Angewandtes Gesundheitsmarketing; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-3-8349-4034-6. [Google Scholar]

- Muntschick, V. Der Neue Resonanz-Tourismus: Herzlich Willkommen! Zukunftsinstitut: Frankfurt, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-945647-62-2. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).