Abstract

Public reporting is a way to promote quality of healthcare. However, evidence supporting improved quality of care using public reporting in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is disputed. This study aims to describe the impact of public reporting of AMI care on hospital quality improvement in Korea. Patients with AMI admitted to the emergency room with ICD-10 codes of I21.0 to I21.9 as the primary or secondary diagnosis were identified from the national health insurance claims data (2007–2012). Between 2007 and 2012, 43,240/83,378 (51.9%) patients manifested ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Timely reperfusion rate increased (β = 2.78, p = 0.001). The mortality rate of STEMI patients was not changed (β = −0.0098, p = 0.384) but that of NSTEMI patients decreased (β = −0.465, p = 0.001). Public reporting has a substantial impact on the process indicators of AMI in Korea because of the increased reperfusion rate. However, the outcome indicators such as mortality did not significantly change, suggesting that public reporting did not necessarily improve the quality of care.

1. Introduction

Heart disease, including acute myocardial infarction, is the second most common cause of death in Korea [1]. The mortality rate associated with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in Korea is 8.1%, which is higher than the average mortality rate of 7.5% in the OECD countries [2]. Patients should be treated as soon as possible after the onset of symptoms to reduce the risk of death. Guidelines for AMI diagnosis and treatment have been published by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) [3] advocate for patients to be treated as soon as possible after the onset of symptoms to reduce the risk of death.

Public reporting has been used to promote the quality of health care worldwide [4,5,6]. The Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) introduced a healthcare performance management program in 2002, with a pilot project of public reporting in 2005 and extended it to private and public hospitals [7]. In Korea, more than 90% of hospitals are private and the percentage of public hospitals is far lower than the OECD average [8]. The main method of payment is fee-for-service (FFS) at both private and public hospitals/clinics, although a prospective payment system (PPS) has been partially introduced.

Studies have shown that public reporting on AMI reduces mortality [9,10] and improves reperfusion rates [11] in patients with AMI. However, other studies have shown no association between public reporting and mortality [11,12,13,14]. Further, studies have demonstrated that public reporting did not improve the quality of process of care [15] and prevented clinicians from treating high-risk patients [14,15,16]. Additionally, the findings of HIRA and the academic society regarding the effect of public reporting in improving the quality of care in patients with AMI are disputed [17].

Further, HIRA introduced the pay-for-performance program in 2011 based on the public reporting scores, which were close to the maximum value with minor variation, suggesting the need to review the appropriateness of public reporting of AMI in improving the quality of care for implementing future programs. To date, the gap between HIRA and the position of healthcare community on the effect of public reporting has yet to be bridged, and therefore the public reporting of AMI has not resumed since its discontinuation in 2012.

Thus, we conducted this study to describe the impact of public reporting on AMI care in improving the hospital quality in Korea. The hypotheses are:

Hypotheses 1:

The public reporting improves the process indicators of AMI.

Hypotheses 2:

The public reporting reduces the mortality of AMI.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources

Hospital quality of AMI care data were sourced from HIRA. Data were registered using the computerized system of HIRA for hospital evaluation. Patient demographics, diagnoses, procedures, medication, laboratory results, hospitalization records, and emergency room visits were based on hospital medical data.

2.2. Study Population

Patients were included if they were admitted to the emergency room and their primary or secondary diagnosis was assigned International Statistical ICD-10 codes of I21.0 to I21.9. In 2010, the patients with ICD-10 codes in the secondary diagnoses were included. Patients were excluded if they did not have a definitive diagnosis of AMI, were not discharged at the time of data collection, or were diagnosed with AMI after being hospitalized for other disease(s).

Between 2007 to 2012, 21% of patients with definitive AMI, including inpatients and outpatients [18,19,20,21,22,23], met the eligibility criteria in the annual public reporting of AMI care by HIRA, and represented our study population. 99.6% of all tertiary hospitals and 54.5% of all general hospitals in Korea participated in the study [24]. We further stratified our AMI population into patients presenting ischemic symptoms and persistent ST-segment elevation on the electrocardiogram (ECG) for STEMI group and non ST-segment elevation for NSTEMI group according to universal definition of myocardial infarction.

2.3. Indicators

The process indicators included rates of reperfusion, timely reperfusion, and oral medication. The reperfusion rates indicate the proportion of patients who underwent reperfusion treatment. Reperfusion rates of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI were calculated, and the correlation between reperfusion rates and mortality in the two groups was analyzed.

Timely reperfusion rate is a treatment performance indicator for STEMI. The treatment of STEMI requires thrombolytic agents and primary percutaneous coronary intervention (P.PCI). Timely reperfusion rate was calculated by combining (1) thrombolytic rate and (2) P.PCI rate. The reference time for reperfusion was shortened in 2010, while the thrombolytic treatment time decreased from 60 min to 30 min and P.PCI time decreased from 120 min to 90 min. The association between mortality of STEMI and timely reperfusion rate was analyzed.

Oral medication rates were defined as the rate of aspirin administered upon arrival and the prescription rate of aspirin and beta blockers at discharge. Oral medications were administered to all of the patients and the association between oral medication rates and mortality was analyzed. Other indicators affecting the care process included the usage rate of ambulance services and the median time from AMI symptoms to door. The median time from arrival at the hospital to thrombolytic treatment and the median time from arrival at the hospital to receiving balloon inflation in the P.PCI procedure for patients with STEMI was computed (Table A1).

The outcome indicators included 30-day mortality rate following admission and 1-year mortality rate from symptom manifestation. Annual mortality rates for six years (2007 to 2012) and monthly mortality rates for four years (2009 to 2012) were calculated.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We investigated the changes in the process and outcome indicators annually or monthly by hospital type (tertiary vs. general) and AMI type (STEMI vs. NSTEMI) for years. Chi-squared analysis and an ANOVA test were used to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients over the years. Linear regression analysis was performed to determine the estimate (β) with 95% confidence interval (CI) of the process and outcome indicators by year. A correlation analysis of the association between the process and outcome indicators with respect to hospital type was performed. Multiple regression analyses were performed to determine the association between the process of care and mortality. Only simple linear regression models were created using one of the process indicators due to severe multi-collinearities among the independent variables. The Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model (12, 0, 0) was used because of seasonal variation in mortality data. The analysis of NSTEMI was also based on the ARIMA model (0, 0, 1).

SAS (version 9.2, Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients and Hospitals

Among the total patients analyzed between 2007 and 2012, the least number of patients was evaluated in 2007 because of the inclusion of patients at tertiary hospitals from the last half of the year. The largest number of patients were included in the year 2010 following expansion of the inclusion criteria of targeted subjects with secondary diagnosis of AMI, in addition to the primary diagnosis in the national health insurance claims data. However, the number of eligible patients in 2010 did not significantly increase from the previous year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients.

3.2. Process Indicators

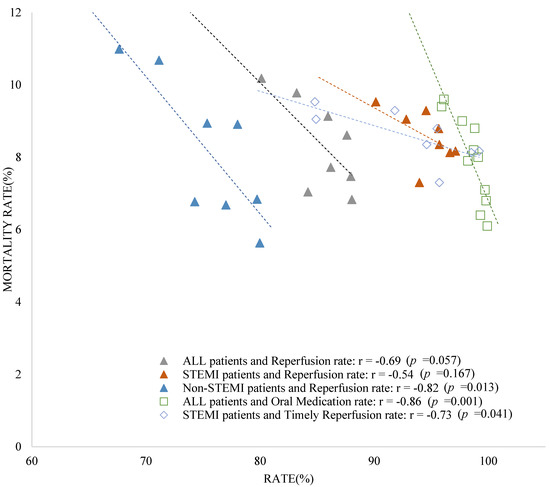

Of the eligible patients, 84.8% patients underwent reperfusion treatment. Reperfusion treatment was administered to 93.9% STEMI and 75.1% of NSTEMI cases. The reperfusion rate increased to more than 80% during the study period, and was higher in STEMI than in NSTEMI cases (Table 1). Reperfusion rate was increased by 6.6% between 2007 and 2012. Only an increased reperfusion rate of NSTEMI was associated with a decrease in the 30-day mortality of NSTEMI (p = 0.013) (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Association between year and process and outcome indicators.

Figure 1.

Relationship between annual 30−days mortality and indicators of hospital type. (1) Triangles: Relationship between annual 30−days mortality rate and annual reperfusion rate by hospital type (tertiary and general hospitals) for all patients including STEMI and NSTEMI (2009~2012); (2) Square: Relationship between annual 30−days mortality rate and annual oral medication rate by hospital type (tertiary and general hospitals) for all patients; (3) Rhombus: Relationship between annual 30−days mortality rate in STEMI patients and annual timely reperfusion rate by hospital type (tertiary and general hospitals) (2009~2012).

The overall timely reperfusion rate showed an increase of 14.0% between 2007 and 2012. The overall timely perfusion rate was 90.9% in 2009 and has exceeded 90.0% since then. In case of tertiary hospitals alone, the timely reperfusion rate increased by 16.3%. In 2009, the rate at the tertiary hospital was 95.7% and steadily increased by 95% since then. The general hospital showed a 13.3% increase in timely reperfusion rate. The increase was associated with a decrease in the 30-day mortality rate of STEMI (p = 0.041) (Table 2, Figure 1).

The prescription rates of oral medications increased by 1.4% from 2007 to 2012. The prescription rate of oral medication exceeded 95% since 2007, and no significant difference was found between hospital types. An increase in oral medication rate was associated with a decrease in the 30-day mortality (p = 0.001) (Table 2, Figure 1).

The number of patients utilizing an ambulance was 51.5%. The ambulance utilization rate was 51.3% in 2009 and increased by more than 50% since then. The increase was greater in tertiary than in general hospitals. The median AMI symptom-to-door time was the highest at 164 min in 2009 and has since declined. The median symptom-to-door time was longer in tertiary than in general hospitals, with an average difference of 49.7 min per year (p < 0.001) (Table 1 and Table 2).

3.3. Outcome Indicators

The 30-day mortality rate decreased during the study periods. The 30-day mortality rate in tertiary hospitals did not decrease, whereas it decreased from 2008 to 2012 in general hospitals. It was significantly shorter in tertiary than in general hospitals (p < 0.001) (Table 1 and Table 2).

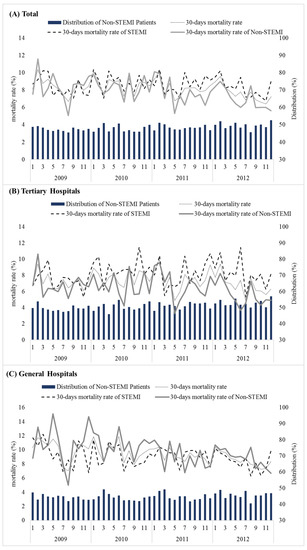

There were 67,191 patients between 2009 and 2012, including 51.6% of STEMI cases. The overall 30-day mortality rate since admission decreased (p = 0.004, ARIMA p < 0.001). The 30-day mortality rate for the STEMI did not change (p = 0.385, ARIMA p = 0.859), but decreased for NSTEMI (p = 0.001, ARIMA p = 0.001). The 1-year mortality rate decreased during the same time period. The 1-year mortality rate for patients with STEMI did not change, but decreased for NSTEMI cases (Figure 2, Table 3).

Figure 2.

30-day mortality rate and distribution of NSTEMI patients (2009 to 2012). (A) Total; (B) Tertiary Hospitals; (C) General Hospitals.

Table 3.

Linear regression analysis of factors associated with mortality rate (2009 to 2012).

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

Overall, our key findings showed that the public reporting in Korea has a marginal impact on the AMI quality of care improvement. First, the timely reperfusion rate marginally increased during the study period. However, as the reperfusion rate was high (>90%), the margin of increase was limited. Second, the 30-day mortality rate for NSTEMI significantly decreased significantly.

The timely reperfusion rate in 2010 decreased from the previous year presumably due to the 30-min reduction in appropriate treatment time in 2010. The P.PCI rate decreased by 0.5% and the thrombolytic rate decreased by 2%. Thus, the timely reperfusion rate was influenced by a decrease in the thrombolytic rate in the general hospital.

The prescription rate of oral medication increased during the study period. The aspirin prescription at discharge was already greater than 99% in 2007. An increase in the prescription rate of beta blockers might not be regarded as improvement in treatment quality. Despite the controversial side effects of beta-blockers [25], a small number of beta-blockers were administered occasionally even in unnecessary cases to obtain a high score.

4.2. Interpretation within the Context of the Wider Literature

During the study period, the 30-day mortality rate significantly decreased among NSTEMI cases but did not significantly change among those with STEMI. There are several possible reasons for the decline in the mortality rate associated with NSTEMI. First, the improved AMI care process resulted in better quality of care. Second, the number of NSTEMI cases who underwent reperfusion increased, which may reflect a greater proportion of admissions involving NSTEMI [26,27,28] or exclusion of NSTEMI cases at the hospitals to increase their performance score. The reduction in mortality rate was higher than the 30-day mortality rate following admission due to STEMI than NSTEMI, or a reduction in the time taken to reach the hospital may have affected the mortality rate. According to Nallamothu’s study, the decreased mortality rate in AMI patients was attributed to changes in population over time [29].

The 30-day mortality rate did not significantly change and the 1-year mortality rate following symptom manifestation decreased. Thus, the long-term benefits of public reporting should be further investigated in larger populations. While the 30-day mortality was higher in STEMI than in NSTEMI cases, the 1-year mortality was higher in NSTEMI than in STEMI. This may potentially be due to the older age of patients with NSTEMI with a greater burden of cardiovascular comorbidities than STEMI [30,31]. Under-utilization of effective cardiac medications and PCI, as well as delays in the time to PCI in patients with NSTEMI may also contribute to this difference in mortality between STEMI and NSTEMI cases [31].

4.3. Implications for Policy, Practice and Research

The timely reperfusion rate in tertiary hospitals varied enormously compared with the rate in general hospitals. The mortality rate associated with STEMI decreased in general hospitals due to improved quality of medical care compared with the quality at tertiary hospitals. However, selection bias may have potentially influenced this outcome at the general hospitals as patients reporting favorable treatment outcome may have been selected [14,16]. The tertiary hospitals reported shorter door-to-thrombolytic time, door-to-P.PCI balloon inflation time and better ambulance utilization except symptom-to-door time than the general hospitals. These factors did not lead to a reduction in mortality.

In addition, the data source is another factor determining the outcome. The tertiary hospitals in Korea have an average of 5 or more cardiologists and more than 500 beds [32]. This number is twice the average size than the general clinics. The tertiary setup achieved high rates of timely reperfusion exceeding 95%, in contrast to the general hospitals. The differences in timely reperfusion rate (annual difference of 4−6%) were greater than the differences in the rate of oral medication administered at tertiary and general hospitals, whereas the rate of oral medication was similar at the two hospitals because oral medication is relatively easier to administer than reperfusion treatment. Since timely reperfusion rate requires additional personnel and financial resources, the rate was higher in tertiary hospitals equipped with sufficient medical personnel and resources.

In 2005, ACC/AHA recommended reperfusion treatment for STEMI [3]. The tertiary hospitals immediately implemented the recommendations. The general hospitals with relatively lower levels of reperfusion therapy reported an increase in reperfusion rate during the evaluation period, which reduced mortality. Public reporting leads to improved quality of institutions with scarce medical resources. Public reporting should be used to identify and support hospitals with insufficient resources.

4.4. Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, the total number of patients increased in 2010 due to changes in criteria to identify patients with AMI based on secondary diagnosis in addition to primary diagnosis. Since AMI patients identified via secondary diagnosis often failed to receive AMI confirmation at the hospital, only 65% of patients with AMI diagnosis were eligible for this study. However, a majority of AMI patients were selected based on the primary diagnosis. The effects of eligibility criteria, which includes patients with secondary diagnosis after 2010, was insignificant. To ensure the reliability, data were randomly sampled from each hospital and compared with the hospital medical records to establish their accuracy. In case of inconsistency, the error was corrected after careful review. Depending on the indicator, the data for exclusion were determined by an expert advisory council. Second, our study described outcomes of patients with AMI without a comparator group (i.e., outcomes of patients with AMI before public reporting) and thus could not confirm the association between public reporting and quality of care. We included all tertiary hospitals with AMI and most general hospitals offering treatment for AMI in Korea. Almost all of the patients with AMI were included and therefore no hospitals were available for comparison. Since 100% of tertiary hospitals (except only one hospital in 2012) and 50% of general hospitals participated in the public reporting exercise from 2007 to 2012, the findings represent the results of AMI care. Third, due to the lack of patient demographic data, standardized adjusted mortality for case mix index could not be calculated. Thus, there can be various confounders in the relationship between AMI care and outcomes. Fourth, specific factors were not included in our analysis, such as changes in reference time for reperfusion over time and the newly established regional cardio-cerebrovascular center, which might have impacted the AMI care. The government has designated each regional university hospital as a regional cardio-cerebrovascular center to facilitate the rapid treatment of patients with AMI and stroke in all regions. The number of cardio-cerebrovascular centers increased from three in 2008 to 14 in 2018 [33].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the public reporting system has a substantial impact on the process indicators of AMI in Korea because of the increase in reperfusion rate. However, outcome indicators such as the mortality did not significantly change, suggesting that it did not necessarily improve the quality of care. Disparity exists in quality of care across hospitals, with tertiary care centers equipped with abundant resources offering better quality than general care centers. The variation in public reporting across individual hospitals underscores the need to investigate their management features and practice norms. Further studies are needed on the criteria for treatment and mortality for NSTEMI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: K.C., M.K., B.O.K., H.-J.K., D.-J.O., D.W.J., W.-Y.C., C.U.C., K.-R.H., M.-S.H., H.Q. and S.K.; methodology: K.C., M.K., C.Y.J. and S.K.; Writing—original draft: K.C. and M.K.; Writing—reviewing and editing: M.K., S.L. and S.K.; Project administration: K.C., M.K., C.Y.J. and S.K.; Formal analysis: K.C. and C.Y.J.; Supervision: B.O.K., H.-J.K., D.-J.O., D.W.J., W.-Y.C., C.U.C., K.-R.H., M.-S.H., H.Q. and S.K.; Funding acquisition: K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been funded by the Research Institute for Healthcare Policy, Korean Medical Association (KMA) in 2017 (No.2017-12-18). The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board Catholic University of Korea (MC18ZESI0044).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. Patient records/information were anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Study variables.

Table A1.

Study variables.

| Variables | Numerator | Denominator (Case of Population) |

|---|---|---|

| Population | ||

| Source population | No. of patients identified from claim data | |

| Eligible patients | No. of patients diagnosed with AMI | |

| Exclude | No. of excluded patients | |

| Male patients | No. of male patients | |

| Age | Mean, SD of patients | |

| Age of males | Mean, SD of male patients | |

| Age of females | Mean, SD of female patients | |

| STEMI 1 patients | ST elevation on ECG or new onset LBBB | |

| Patients treated with reperfusion | No. of patients exposed to reperfusion | |

| Reperfusion of STEMI patients | No. of STEMI patients treated with reperfusion | |

| Reperfusion of NSTEMI 2 patients | No. of NSTEMI patients treated with reperfusion | |

| Monthly patients | Monthly number of patients | |

| Monthly number of STEMI patients | Monthly number of STEMI patients | |

| Monthly number of non-STEMI patients | Monthly number of NSTEMI patients | |

| Process | ||

| Timely reperfusion rate (A = A1 + A2) | STEMI | |

| Thrombolytic rate within 30 min (A1) | within 30 min of arrival (from 2010 to 2012)within 60 min of arrival (from 2007 to 2009) | Thrombolytic therapy within 6 h of hospital arrival of STEMI |

| P.PCI rate within 90 min (A2) | within 90 min of arrival (from2010 to 2012)within 120 min of arrival (from 2007 to 2009) | P.PCI within 12 h of hospital arrival of STEMI |

| Oral medication (B = B1 + B2 + B3) | Eligible | |

| Aspirin at arrival (B1) | Aspirin administered within 24 h of hospital arrival | |

| Aspirin prescribed at discharge (B2) | prescribed at discharge | |

| Beta-blocker prescribed at discharge (B3) | prescribed at discharge | |

| Ambulance utilization rate | No. of patients hospitalized by ambulance | Eligible |

| Symptom-to-door (S2D) median time (minutes) | Symptom-to-door median time (minutes) | Eligible |

| Door-to-thrombolytic(D2T) median time (minutes) | Door to thrombolytic (D2T) median time (minutes) | STEMI |

| Door-to-P.PCI balloon inflation (D2B) median time (minutes) | Door-to-P.PCI balloon inflation (D2B) median time (minutes) | STEMI |

| Outcomes | ||

| 30-day mortality rate following admission | No. of patients who died within 30 days of hospitalization | Eligible |

| In-hospital mortality rate | No. of patients who died during hospitalization | |

| Monthly 30-days mortality rate from admission | Number of patients dying within 30 days of hospitalization | Eligible |

| 1-year mortality following symptoms | Number of patients dying within 1 year of symptom manifestation |

1 ST-segment elevation on the electrocardiogram; 2 Non ST-segment elevation.

References

- Korean Staticstical Information Service. Number of Deaths by Cause. 2014. Available online: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/1/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=349053&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&searchInfo=srch&sTarget=title&sTxt=+Causes+of+Death+Statistics+in+2014 (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- OECD. Health Statistics. OECD Health Statistics 2017. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888933603678 (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- Hunt, S.A. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J. Am. Coll. Cardio. 2005, 46, e1–e82. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital Compare—Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/hospitalqualityinits/hospitalcompare.html (accessed on 2 April 2019).

- Ryan, A.; Sutton, M.; Doran, T. Does winning a pay-for-performance bonus improve subsequent quality performance? Evidence from the Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration. Health Serv. Res. 2014, 49, 568–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Stroke Audit Acute Services. National Stroke Audit Acute Services Executive Summary 2015; National Stroke Foundation: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Kang, M. The Performance Management System of the Korean Healthcare Sector: Development, Challenges, and Future Tasks. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2016, 39, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Health Statistics 2018. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- Boyden, T.F.; Joynt, K.E.; McCoy, L.; Neely, M.L.; Cavender, M.A.; Dixon, S.; Masoudi, F.A.; Peterson, E.; Rao, S.V.; Gurm, H.S. Collaborative quality improvement vs public reporting for percutaneous coronary intervention: A comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention in New York vs. Michigan. Am. Heart J. 2015, 170, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavender, M.A.; Joynt, K.E.; Parzynski, C.S.; Resnic, F.S.; Rumsfeld, J.S.; Moscucci, M.; Masoudi, F.A.; Curtis, J.P.; Peterson, E.D.; Gurm, H.S. State mandated public reporting and outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 115, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzi, C.; Asta, F.; Fusco, D.; Agabiti, N.; Davoli, M.; Perucci, C.A. Does public reporting improve the quality of hospital care for acute myocardial infarction? Results from a regional outcome evaluation program in Italy. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2014, 26, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Waldo, S.W.; McCabe, J.M.; O’Brien, C.; Kennedy, K.F.; Joynt, K.E.; Yeh, R.W. Association between public reporting of outcomes with procedural management and mortality for patients with acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apolito, R.A.; Greenberg, M.A.; Menegus, M.A.; Lowe, A.M.; Sleeper, L.A.; Goldberger, M.H.; Remick, J.; Radford, M.J.; Hochman, J.S. Impact of the New York State Cardiac Surgery and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Reporting System on the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Am. Heart J. 2008, 155, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joynt, K.E.; Blumenthal, D.M.; Orav, E.J.; Resnic, F.S.; Jha, A.K. Association of public reporting for percutaneous coronary intervention with utilization and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2012, 308, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, J.V.; Donovan, L.R.; Lee, D.S.; Wang, J.T.; Austin, P.C.; Alter, D.A.; Ko, D.T. Effectiveness of public report cards for improving the quality of cardiac care: The EFFECT study: A randomized trial. JAMA 2009, 302, 2330–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangalore, S.; Guo, Y.; Xu, J.; Blecker, S.; Gupta, N.; Feit, F.; Hochman, J.S. Rates of Invasive Management of Cardiogenic Shock in New York before and after Exclusion from Public Reporting. JAMA Cardiol. 2016, 1, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Acute Myocardial Infarction Mortality Rate 1.5% P Reduction from the Initial Phase. 16 August 2012. Available online: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&page=451& CONT_SEQ=243407 (accessed on 2 April 2019).

- Korean Staticstical Information Service. The Number of Patients of Insurance Claim by Disease Sub-Classification (2007). 2007. Available online: http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=350&tblId=DT_35001_A003&conn_path= I2 (accessed on 7 April 2019).

- Korean Staticstical Information Service. The Number of Patients of Insurance Claim by Disease Sub-Classification (2008). 2008. Available online: http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=350&tblId=DT_35001_A054&conn_path=I2 (accessed on 7 April 2019).

- Korean Staticstical Information Service. The Number of Patients of Insurance Claim by Disease Sub-Classification (2009). 2009. Available online: http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=350&tblId=DT_35001_A067&conn_path= I2 (accessed on 7 April 2019).

- Korean Staticstical Information Service. The Number of Patients of Insurance Claim by Disease Sub-Classification (2010). 2010. Available online: http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=350&tblId=DT_35001_A06701&conn_path=I2 (accessed on 7 April 2019).

- Korean Staticstical Information Service. The Number of Patients of Insurance Claim by Disease Sub-Classification (2011). 2011. Available online: http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=350&tblId=DT_35001_A0701&conn_path=I2 (accessed on 7 April 2019).

- Korean Staticstical Information Service. The Number of Patients of Insurance Claim by Disease Sub-Classification (2012). 2012. Available online: http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=350&tblId=DT_35001_A07011&conn_path=I2 (accessed on 7 April 2019).

- Nunes, B.; Viboud, C.; Machado, A.; Ringholz, C.; Rebelo-de-Andrade, H.; Nogueira, P.; Miller, M. Excess mortality associated with influenza epidemics in Portugal, 1980 to 2004. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitouni, M.; Kerneis, M.; Lattuca, B.; Guedeney, P.; Cayla, G.; Collet, J.P.; Montalescot, G.; Silvain, J. Do Patients need Lifelong beta-Blockers after an Uncomplicated Myocardial Infarction? Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2019, 19, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, D.D.; Gore, J.; Yarzebski, J.; Spencer, F.; Lessard, D.; Goldberg, R.J. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am. J. Med. 2011, 124, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, D.; Xie, W.; Xie, X.; Guo, M.; Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, J. Recent Trends in Hospitalization for Acute Myocardial Infarction in Beijing: Increasing Overall Burden and a Transition from ST-Segment Elevation to Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction in a Population-Based Study. Medicine 2016, 95, e2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kook, H.Y.; Jeong, M.H.; Oh, S.; Yoo, S.H.; Kim, E.J.; Ahn, Y.; Kim, H.J.; Chai, L.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, C.J.; et al. Current Trend of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Korea (from the Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry from 2006 to 2013). Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 114, 1817–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nallamothu, B.K.; Normand, S.L.T.; Wang, Y.; Hofer, T.P.; Brush, J.E., Jr.; Messenger, J.C.; Bradley, E.H.; Rumsfeld, J.S.; Krumholz, H.M. Relation between door-to-balloon times and mortality after primary percutaneous coronary intervention over time: A retrospective study. Lancet 2015, 385, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralapanawa, U.; Kumarasiri PV, R.; Jayawickreme, K.P.; Kumarihamy, P.; Wijeratne, Y.; Ekanayake, M.; Dissanayake, C. Epidemiology and risk factors of patients with types of acute coronary syndrome presenting to a tertiary care hospital in Sri Lanka. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2019, 19, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, W.J.; Frederick, P.D.; Stoehr, E.; Canto, J.G.; Ornato, J.P.; Gibson, C.M.; Pollack, C.V., Jr.; Gore, J.M.; Chandra-Strobos, N.; Peterson, E.D.; et al. Trends in presenting characteristics and hospital mortality among patients with ST elevation and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am. Heart J. 2008, 156, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Rules for Designation and Evaluation of Tertiary Hospitals. 2017. Available online: http://www.law.go.kr/%EB%B2%95%EB%A0%B9/%EC%83%81%EA%B8%89%EC%A2%85%ED%95%A9%EB%B3%91%EC%9B%90%EC%9D%98%20%EC%A7%80%EC%A0%95%20%EB%B0%8F%20%ED%8F%89%EA%B0%80%EC%97%90%20%EA%B4%80%ED%95%9C%20%EA%B7%9C%EC%B9%99 (accessed on 2 April 2019).

- KCDC. Policy of Cardiovascular Disease Center Business. 2018. Available online: http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/contents/CdcKrContentView.jsp?cid=102731&menuIds=HOME006-MNU2802-MNU2895 (accessed on 2 April 2019).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).