Abstract

Mental health in children and adolescents has become an increasingly important topic in recent years. It is against this backdrop that physical education and school sports play an important role in promoting psychological wellbeing. The aim of this review was to analyse interventions for improving psychological wellbeing in this area. To this end, a literature review was conducted using four databases (WOS, SPORTDiscus, SCOPUS and ERIC) and the following keywords: psychological wellbeing, physical education, and school sports. Twenty-one articles met the inclusion criteria. The results showed that interventions varied greatly in terms of duration and used a wide range of strategies (conventional and non-conventional sports, physical activity, games, etc.) for promoting psychological wellbeing, primarily among secondary school students. There was a lack of consensus as to the conceptualisation of the construct of psychological wellbeing, resulting in a variety of tools and methods for assessing it. Some studies also suggested a link between psychological wellbeing and other variables, such as basic psychological needs and self-determination. Finally, this study provides a definition of psychological wellbeing through physical activity based on our findings.

1. Introduction

Mental health problems in adulthood originate primarily in childhood and can be related to a variety of causes, such as socioeconomic, genetic or cultural factors [1]. It is in adolescence that the greatest risks of behaviours affecting wellbeing occur [2,3]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) [4] describes these problems as the main cause of disability worldwide, with depression extremely prevalent among young people [5]. School is therefore a suitable location for interventions, allowing students to acquire and develop skills and strategies to face life’s challenges as best they can, with high levels of physical and psychological wellbeing [6,7].

In recent years, the use of physical activity (PA) and sports for personal and social development in children and adolescents has been the subject of an increasing number of studies. Research suggests that physical education (PE) and school sports provide a suitable, effective framework for transferring and teaching skills and strategies to reduce risky behaviour and promote wellbeing [8,9]. Although there is evidence that PA and sports enhance young people’s skills and values at these life stages, there is a gap in research on their impact on psychological wellbeing and a lack of consensus as to the definition of psychological wellbeing in this context [10].

Studies have shown that individuals with high levels of psychological wellbeing are more successful in terms of education, work, friends, stable relationships and physical health [11]. In education, psychological wellbeing leads to improved attention, creative thinking and holistic thinking [5]. Psychological wellbeing is usually understood as a construct from the eudaimonic tradition. Unlike subjective wellbeing, which derives from happiness and satisfaction through the pursuit of pleasure and the reduction of pain, psychological wellbeing seeks to allow people to attain their maximum potential by developing virtues [12], focusing on capabilities and personal growth, and understanding that happiness is achieved through individual self-realisation [13,14]. Psychological wellbeing focuses on the process and on pursuing values leading to personal growth rather than on pleasurable, pain-avoiding activities, thus making the individual feel alive and authentic [15]. Ryff [16] proposed a multidimensional model for understanding psychological wellbeing called the Integrated Model of Personal Development (IMPD), consisting of six dimensions: self-acceptance, autonomy, personal growth, purpose in life, environmental mastery and positive relations with others.

Although information on interventions in the context of PE and school sports using the IMPD is limited, the model is widely recognised as a coherent, logical, valid construct [12], and PA and sports represent useful tools for its implementation [17]. Two systematic reviews by Malm, Jacobsson and Nicholson [18] and Mnich, Weyland, Jekauc and Schipperijn [19] list the benefits of PA and sports, including, on a physical level, reduced risk of developing metabolic syndromes, reduced side effects of cancer, improved cardiovascular health, stronger bones and improved physical condition; and, on a psychological level, improved cognition, better school performance, increased cognitive function and improved mental health, which generates psychological wellbeing.

However, there is limited information on the effects of PA on the development and psychological wellbeing of children and adolescents in the context of PE and school sports. It is therefore necessary to identify different strategies and interventions for developing psychological wellbeing in the literature. The primary objective of this paper is to explore studies that seek to promote psychological wellbeing among schoolchildren through PE and school sports and to identify conceptualisations of psychological wellbeing in this specific context.

This review has two objectives. Firstly, it seeks to address the following questions.

What are the characteristics of studies on psychological wellbeing interventions in PE and school sports?

What are their objectives?

What does the literature report on the outcomes of interventions aiming to improve psychological wellbeing?

Secondly, this review attempts to analyse how psychological wellbeing is conceptualised in this context and to provide a definition of the concept based on the findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This review was carried out following the protocol outlined in the PRISMA statement. A comprehensive search was conducted in four databases: WOS, SPORTDiscus (EBSCO), SCOPUS and ERIC (Proquest). A number of articles were selected considering bibliography of reference research (6). Individual searches of all studies published up to September 2019 were performed in each database following the PICO protocol as used by Opstoel et al. [9] (P = Population, I = Intervention, C = Comparison, O = Outcomes).

- P = child, children, boys, girls, adolescents

- I = physical education

- C = no comparison group was added to the search

- O = psychological wellbeing, eudaimonic wellbeing.

The search terms used were “psychological wellbeing” and “eudaimonic wellbeing”, in combination with “AND” and the search terms “physical education” and “child”, “children”, “boys”, “girls”, and “adolescents”. Searches were conducted in English and Spanish. Only original articles were included in the study.

2.2. Selection Criteria

Potentially relevant studies for this review were checked against the following selection criteria: (a) the study had been published in an international peer-reviewed journal; (b) the study covered interventions with children and adolescents aged between 6 and 18 years old; (c) the study explored the relationship between PE or school sports and psychological wellbeing; and (d) a full-text version was available in English and/or Spanish.

Regarding the first criterion, interventions implemented in the school setting (PE classes and in-school and extracurricular sports activities) were eligible. Regarding the second criterion, interventions with children and adolescents at all stages of formal schooling within the aforementioned age range were also considered for inclusion. In the event that the studies included individuals outside that age range, only articles with the majority of participants within that age range were eligible.

Articles were excluded following Opstoel’s criteria [9]:

- Studies involving a specific population with any type of physical, cognitive or psychological impairment.

- Articles not providing primary data (non-interventions), as they do not ensure methodological and statistical rigour (reviews, conceptual articles, conference proceedings, editorials, doctoral theses, books, opinion articles, etc.).

- Instrument validations.

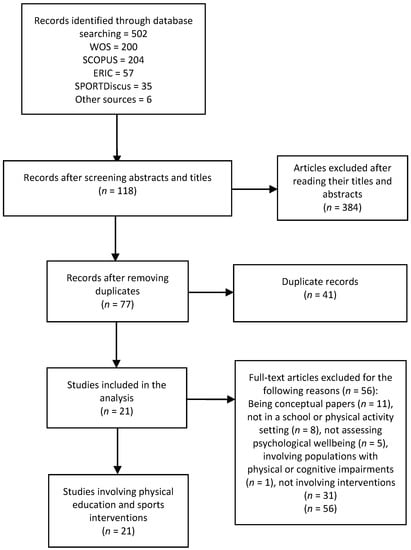

Duplicates were discarded. The study selection process consisted of screening the titles and abstracts identified during the search. Potentially relevant full-text studies were independently checked for eligibility by two authors, J.P.-C. and R.P.-O. Discrepancies in the selection of the articles were discusses until a consensus was reached. Figure 1 shows the sampling process used. After removing duplicates and excluding records by abstract and title, a total of 21 articles were retrieved.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the sampling process.

2.3. Data Extraction and Reliability

Pilot test forms were used to extract data from the studies. A content analysis of the articles included in this review was also performed. Subsequently, the data were discussed and confirmed by the researchers. The following categories were defined: authors, year, journal (volume and issue), country, objectives, sample size, characteristics of the participants, duration of the study, instruments used to assess psychological wellbeing, and results (Table 1).

Table 1.

General overview of the articles included.

The criteria for assessing the quality of the studies included were adapted from the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statement [41] as used by Pozo et al. [42]. The quality assessment criteria were: (a) description of the programme, (b) number of participants, (c) inclusion of the journal of publication in the Journal Citation Reports, (d) duration of the programme, (e) description of the methodology; (f) definition of psychological wellbeing.

Each item was rated from 0 to 2 based on the criteria outlined in Figure 1. A total score was calculated for each study depending on the number of positive items it contained. Studies with a total score of 9 or higher were considered to be of high quality (HQ); studies with a total score of 5–8 were considered to be of average quality (AQ); studies with a total score lower than 4 were considered to be of low quality (LQ). Details are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality of the studies.

The risk of bias is difficult to ascertain in qualitative, social science studies. Version 5.1.0 of the Cochrane handbook emphasises that, in many situations, it is not practical or possible to blind participants or study staff in the intervention group.

3. Results

3.1. Sample

The total number of participants in the studies reviewed was 10,357, ranging from 23 [40] to 3124 [38].

The ages of participants ranged from 7 to 18 years old. Two interventions involved children under 10 [22,36], eight interventions involved children aged 10–15 years old, eleven interventions involved children around 15 years old, one intervention involved children aged 11–16 years old [21], one intervention involved children aged 12–15 years old [33], one intervention involved children aged 12–18 years old [25], and one intervention involved children aged 13–16 years old [29].

Regarding participants’ levels of education, 5 of the 21 studies focused on primary education students, 15 studies focused on secondary education students, and 1 study focused on primary and secondary education.

3.2. Countries

Most of the studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (4/21) and the United States (4/21), followed by Australia (2/21), China (2/21), Turkey (2/21), Canada (1/21), Denmark (1/21), Greece (1/21), Finland (1/21), South Africa (1/21), Spain (1/21), and Sweden (1/21).

3.3. Duration of the Studies

The duration of the interventions ranged from 3 days [37] to 36 weeks [38]. Within that range, four of the 21 studies lasted 8 weeks, three lasted 10 weeks, two lasted 6 weeks, one lasted one week, one lasted 12 weeks, one lasted 13 weeks, one lasted 14 weeks, one lasted 18 weeks, one lasted 20 weeks, one lasted 23 weeks, and one lasted 24 weeks. One study [28] indicated that the pilot study, intervention, evaluation and follow-up lasted for 2 years.

The number of sessions ranged from 4 [36] to 35 [34]. It is important to note that 13 of the 21 studies provided information on the number of sessions conducted in their interventions/programmes.

3.4. Instruments Used to Assess Wellbeing

A variety of instruments were used to assess wellbeing depending on how wellbeing was conceptualised. Only 16 of the 21 articles mentioned instruments for measuring wellbeing: the KIDSCREEN-10, -27, and -52 measures (4/16); the Flourishing Scale (3/16); the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Schedule for Children (3/16); the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (2/16); Ryff’s Psychological Wellbeing Scale (2/16); the SF-12v2 (1/16); the Profile of Mood States (1/16); the Perceived Stress Scale (1/16); the Inventory of Positive Psychological Attitudes (1/16); Harter’s Self-Perception Profile for Children (1/16); the Danish national survey of wellbeing in the school-aged population (1/16); the Personally Expressive Activities Questionnaire (1/16); the British Panel Household Survey (BHPS-Y) (1/16); the Perceived Behavioral Control Questionnaire (1/16); the Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (1/16); the Physical Self-Description Questionnaire (1/16).

3.5. Conceptualisation of Psychological Wellbeing

A variety of conceptualisations of psychological wellbeing were presented in the studies. They were so diverse that there was no consensus among the 21 articles reviewed on the definition of psychological wellbeing in the context of PE and school sports. Some definitions focused on self-confidence, improvements in mood (feeling happier or less sad), self-discipline and goal-setting [21], while other definitions revolved around a broader conceptualisation of wellbeing from the hedonic or eudaimonic perspective [32,39]; as well as health-related quality of life [31], specifically mental health [30]; self-concept and mental health (depression and anxiety) [34]; psychosocial wellbeing: mood states, affects, and perceived stress [35]; self-esteem, intrinsic motivation and attitudes towards dance and group PA [23]; positive feelings towards five domains in life: school, work, family, appearance and friends [29]; flourishing, establishing relationships, self-esteem, purpose in life and optimism [24,27,32] health-related quality of life, positive and negative affects, emotional intelligence and social anxiety [33]; positive thoughts and emotions [30]; self-acceptance and human fulfilment [25]; individuals’ awareness of their own abilities to overcome stress in life, be productive, and contribute their skills to the community [20]; development of human potential and self-realization, which encompasses developing self-acceptance, positive relations with others, self-determination, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth [26]. Five of the studies analysed did not provide a clear definition of the concept of psychological wellbeing [22,28,36,38,40].

3.6. Objectives of the Studies

The objectives most frequently addressed in the articles related to assessing the effects of the programmes on participants (12/21), specifically: the effectiveness of a positive youth development-based sports mentorship programme on wellbeing [30]; the effects of PA and avoiding screen time on wellbeing [32]; the effects of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) on the wellbeing of PE students [27]; the effect of a health education programme on participants’ perceptions of their quality of life [31]; the effectiveness of a randomised, controlled intervention on wellbeing [39]; the effect of a hip-hop dance programme on adolescent wellbeing [21]; the effects of a pedometer-based physical activity intervention on the psychological wellbeing of overweight adolescents [25]; the effects of a health club approach on adolescents [34]; the effect of sports education on the psychological wellbeing of high school students [26]; the effect of a curriculum-based physical activity intervention on primary school students [22], and the effects of running on wellbeing-related variables [36]. Another study sought to evaluate the effect of sports on wellbeing in general [20], while two studies aimed to develop, implement, and evaluate physical activity interventions to improve psychosocial wellbeing [38] and reduce sedentary behaviour [28]. Two other studies sought to assess the effectiveness of PA and sports induction protocols and programmes on psychological wellbeing [24,37]. Three studies aimed to assess the impact of specific programmes on variables related to wellbeing and PA [23,29,33] while another study sought to explore the implementation and short-term outcomes of a responsibility-based physical activity programme that was integrated into an intact high school PE class [40]. Finally, one study aimed to assess whether integrating yoga into the secondary school curriculum had a preventive effect on wellbeing among secondary school students [35].

3.7. Results of the Studies

The articles reviewed mainly reported on the effects of the programmes studied. In three of them [20,24,36], no statistically significant differences in wellbeing were found post-intervention. In five of them [21,27,28,39,40], the authors proposed their respective intervention programmes as strategies for promoting PA and psychosocial variables; however, they failed to provide any results on wellbeing per se. Additionally, Ho et al. [30], McNamee et al. [34], and Connolly et al. [23] described the effects of their programmes on mental health, wellbeing, and other psychological, physical, and PA-related variables among adolescents. In the same vein, Bakır & Kangalgil [20] stated that although no changes in participants’ positivity were identified, there were changes in the mental wellbeing of participants who took part in sporting activities, which was also assessed by Smedegaard et al. [38]. Karasimopoulou et al. [31] reported that children in the experimental group significantly improved their perceptions of physical wellbeing, family life, financial aspects, friends, school life and social acceptance, with better perceptions of autonomy than the control group in the final measurement. In turn, Lubans et al. [32] and Slee & Allan [37] linked their results to the fulfilment of basic psychological needs. While Lubans et al. [32] argued that in order to achieve psychological wellbeing, it is necessary to address autonomy, Slee & Allan [37] argued that psychological wellbeing could be related to self-determination. Other results were linked to the effect of the programmes on academic performance, wellbeing and brain development [22]; improved physical condition, satisfaction with appearance, more positive attitudes towards school and friends, and greater environmental awareness [29]. Finally, Noggle et al. [35] reported that although PE-as-usual students showed decreases in primary outcomes, yoga students maintained or improved them, echoing the findings of Luna et al. [33] regarding subjective wellbeing and emotional intelligence, and Gül et al. [26], who reported that PA and sports had an effect on the individual development of the different dimensions of psychological wellbeing.

4. Discussion

The aim of this review was to analyse the characteristics, objectives, and results of studies seeking to promote psychological wellbeing among schoolchildren through PE and school sports, as well as to identify different conceptualisations of the construct in this specific context and provide a definition of it.

With regard to the first objective, most of the interventions identified were held at secondary schools within school hours, both in PE classes and during in-school and extracurricular sports activities. This was consistent with results from other studies on programmes targeting this population [10,43]. In addition, the durations of the programmes reviewed were similar to those of other programmes involving children and, especially, adolescents. A systematic review by Opstoel et al. [9] notes that studies on this type of population tend to last between 8 and 28 weeks. However, Rodríguez-Ayllon et al. [44] report that interventions can last from 10 days to 2 years. The studies analysed had multiple, varied objectives that can be grouped into four major categories: (i) to evaluate the effects of the interventions and/or programmes on participants, (ii) to explore correlations between the programmes and wellbeing, (iii) to identify relationships between different variables, and (iv) to explore wellbeing and empirical strategies for programme evaluation. These objectives are shared by other studies on variables linked to wellbeing across different populations and settings, such as: individuals with diabetes and the effectiveness of programmes on wellbeing [45]; pre-schoolers, infants, and adolescents, and the effect of PA on mental health [44]; and the effect of PA on happiness [46].

The results obtained from the interventions are linked to other systematic reviews on personal and social growth aspects of PE that seek to explore the effects of PA on psychological wellbeing [43] and improve the psychological and social skills of children and young people to better prepare them for the future [9]. A number of studies have also argued that wellbeing is related to fulfilling basic psychological needs, such as Menéndez-Santurio & Fernández-Río [47], who identified a relationship between social responsibility, basic psychological needs and motivation, and described how these can predict positive relations with others, especially friends. Similar results are reported by Molina, Gutiérrez, Segovia & Hopper [48], who identified a relationship between the implementation of a sports programme and improved basic psychological needs, social relationships and responsibility. In addition, Menéndez-Santurio, Fernández-Río, Cecchini & González-Villora [49] confirm that students who have low wellbeing rates due to victimisation and bullying at school have low levels of satisfaction of basic psychological needs, which supports the relationship between wellbeing, basic psychological needs and self-determination put forward by various authors [12,50,51]. It is important to note that the majority of the studies reviewed used multiple forms of physical activity, such as dance, active play and modified sports, and do not use conventional sports to promote wellbeing. This is in consonance with a review by Sánchez-Alcaraz et al. [52], which discusses the importance for psychosocial development of creating a balance between conventional or more popular sports and other less popular sports and physical activities or exercises offering new experiences for children and adolescents.

There is also a lack of consensus on the definition of psychological wellbeing in the context of PE and school sports. Nevertheless, it is fairly safe to say that more than half of the studies (13 out of 21) linked the construct to Diener’s definition [53], which is related to the concept of hedonism or subjective wellbeing. As a result, these studies assessed variables such as life satisfaction, affects and depression, rather than the dimensions included in Ryff’s IMPD regarding eudaimonic or psychological wellbeing [16,54]. This trend could be explained by the interest in understanding and promoting individual happiness that emerged in the 1980s [14], which was reinforced by Huta & Waterman [55], who pointed out asymmetries and preferences in research on these concepts. Additionally, Cabieses, Obach & Molina [56] argue that producing knowledge from the perspective of subjective wellbeing, that is, looking into life satisfaction and happiness, could be useful when planning public policies for this population. Since subjective wellbeing is associated with immediacy, a large number of studies use this construct. Romero, García-Mas & Brustad [12] point out that psychological wellbeing in the field of PA and sports has not been approached consistently, which may explain the scarcity of studies on this topic. In line with Huta & Waterman [55], we believe that it is necessary to find a compromise definition to inform future research on this topic, as the use of a wide range of definitions produces a wide range of results when analysing and comparing studies focusing on the same concept.

To this end, we propose the following definition based on the aforementioned findings, Ryff’s theoretical approach to psychological wellbeing [14,16,54,57], and aspects inherent to PA and sports, such as movement and corporeality: “Psychological wellbeing in PA (PWBPA) is the state of optimal psychological functioning in the context of physical activity, which encompasses accepting one’s strengths and limitations, being independent in decision-making and self-assessment, choosing or creating favourable environments, interacting positively with others in PA and sports, developing one’s potential to the fullest, and seeking meaning and purpose in life based on PA values.”

With regard to the limitations of our study, articles in both Spanish and English were included; however, their results only provided information from English-speaking countries, limiting perceptions of the phenomenon to a particular culture, which may have influenced the researchers’ conceptualisation of the phenomenon in this particular population. In addition, the search was limited to interventions involving populations without pre-existing physical or cognitive issues, excluding other articles which may have been relevant to the topic. In light of the limited number of studies on psychological wellbeing in the field of PA, specifically in PE and school sports, it would be helpful to conduct a meta-analysis to identify the effects of PA and sports programmes/interventions on the psychological wellbeing of children and youths in the school setting. It would also be of interest for future research to analyse and review articles on PE and sports from the point of view of different countries and cultures. Also, to deepen knowledge it would be interesting in future research to consider additional threads related to other contexts besides PE classes or sport school, such as different kinds of sports practices and socioeconomic differences between schools. Finally, in order to broaden the field of knowledge, further studies could be carried out to provide information on parents, guardians and agents of socialisation, who are very important in the development of children and adolescents.

5. Conclusions

Psychological wellbeing in PE and school sports is a developing field that has drawn increasing attention in recent years, which may be due to the need for PA to improve mental health and quality of life for children and adolescents.

We found that most programmes/interventions involve adolescents, especially in secondary schools. The programmes usually last between 3 days and 36 weeks (9 months or an academic year), and it is English-speaking countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, that have conducted the majority of the studies on this topic. There is no consensus as to definitions of the concept, study objectives, methods or tools for assessing psychological wellbeing. As for whether or not PA promotes psychological wellbeing in PE and school sports, the disparate results of the studies analysed do not allow us to draw conclusions. However, there appears to be a relationship between PA, wellbeing and other variables, such as basic psychological needs and quality of life.

From an educational perspective, the authors suggest that future interventions should employ a single definition of psychological wellbeing in PA, such as the one proposed in this paper. This would promote self-realisation and personal growth in children and adolescents by focusing on transcendence rather than on a narrow search for subjective wellbeing, while providing researchers with a common criterion for applying the concept in the context of PA.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.P.-C. and R.P.-O.; methodology: R.P.-O. and A.F.-M.; investigation: J.P.-C. and A.N.; resources: J.P.-C. and R.P.-O.; data curation: J.P.-C. and R.P.-O.; writing—original draft preparation: J.P.-C. and A.N.; writing—review & editing: A.F.-M. and A.N.; visualisation: A.F.-M. and A.N.; supervision: A.F.-M. and A.N. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Andalusian Regional Government (Andalusia, Spain).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in-volved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kieling, C.; Baker-Henningham, H.; Belfer, M.; Conti, G.; Ertem, I.; Omigbodun, O.; Rohde, L.A.; Srinath, S.; Ulkuer, N.; Rahman, A. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Worldwide: Evidence for Action. Lancet 2011, 378, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Días, C.; Cruz, J.; Danish, S. El Deporte Como Contexto Para El Aprendizaje y La Enseñanza de Competencias Personales. Programas de Intervencion Para Niños y Adolescentes. Revista de Psicología del Deporte 2000, 9, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, F.G. Caracterización de factores implicados en las conductas de riesgo en adolescentes. Rev. ABRA 2018, 38, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J. World Happiness Report. 2013. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/happiness-report/2013/WorldHappinessReport2013_online.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Seligman, M.E.P. Florecer: La Nueva Psicología Positiva y la Búsqueda del Bienestar; Océano exprés: México D.F, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, L.; Marchant, D.; Johnson, L.; Huntley, E.; Kosteli, M.; Varga, J.; Ellison, P. Life Skills Development in Physical Education: A Self-Determination Theory-Based Investigation across the School Term. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 49, 101711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechmann, C.; Catlin, J.R.; Zheng, Y. Facilitating Adolescent Well-Being: A Review of the Challenges and Opportunities and the Beneficial Roles of Parents, Schools, Neighborhoods, and Policymakers. J. Consumer Psychol. 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, I.; Ruiz-Esteban, C. Actividad física, consumo de drogas y conductas riesgo en adolescentes. JUMP 2020, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Opstoel, K.; Chapelle, L.; Prins, F.J.; De Meester, A.; Haerens, L.; van Tartwijk, J.; De Martelaer, K. Personal and Social Development in Physical Education and Sports: A Review Study. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 26, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Hernandez, J.; Fayos, E.; García del Castillo-López, Á. Percepción de Bienestar Psicológico y Fomento de La Práctica de Actividad Física En Población Adolescente. Sociotam 2011, 22, 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J.; Kern, M.L. The PERMA-Profiler: A Brief Multidimensional Measure of Flourishing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, A.E.R.; Garcia-Mas, A.; Brustad, R.J. Estado Del Arte, y Perspectiva Actual Del Concepto de Bienestar Psicológico En Psicología Del Deporte [State of the Art and Current Perspective of Psychological Well-Being in Sport Psychology]. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2009, 41, 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.; Singer, B. Best News yet on Six-Factor Model of Well Being. Soc. Sci. Res. 2006, 35, 1103–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological Well-Being Revisited: Advances in the Science and Practice of Eudaimonia. Psychother. Psychosom. 2014, 83, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada, F.V.; Tur, M.C.T.; Resano, C.S.; Osuna, M.J. Bienestar, adaptación y envejecimiento: Cuando la estabilidad significa cambio. Rev. Multidiscip. Gerontol. 2003, 13, 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D. Well-Being with Soul: Science in Pursuit of Human Potential. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloodworth, A.; McNamee, M.; Bailey, R. Sport, Physical Activity and Well-Being: An Objectivist Account. Sport Educ. Soc. 2012, 17, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, C.; Jakobsson, J.; Isaksson, A. Physical Activity and Sports-Real Health Benefits: A Review with Insight into the Public Health of Sweden. Sports 2019, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnich, C.; Weyland, S.; Jekauc, D.; Schipperijn, J. Psychosocial and Physiological Health Outcomes of Green Exercise in Children and Adolescents-A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakır, Y.; Kangalgil, M. The Effect of Sport on the Level of Positivity and Well-Being in Adolescents Engaged in Sport Regularly. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2017, 5, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulac, J.; Kristjansson, E.; Calhoun, M. ‘Bigger than Hip-Hop?’ Impact of a Community-Based Physical Activity Program on Youth Living in a Disadvantaged Neighborhood in Canada. J. Youth Stud. 2011, 14, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käll, L.B.L.; Malmgren, H.; Olsson, E.; Lindén, T.; Nilsson, M. Effects of a Curricular Physical Activity Intervention on Children’s School Performance, Wellness, and Brain Development. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.K.; Quin, E.; Redding, E. Dance 4 Your Life: Exploring the Health and Well-being Implications of a Contemporary Dance Intervention for Female Adolescents. Res. Dance Educ. 2011, 12, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costigan, S.A.; Eather, N.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Hillman, C.H.; Lubans, D.R. High-Intensity Interval Training for Cognitive and Mental Health in Adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1985–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, J. The Effect of Accumulated Walking on the Psychological Well-Being and on Selected Physical- and Physiological Parameters of Overweight/Obese Adolescents. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Dance 2015, 21, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar]

- Gül, Ö.; Çağlayan, H.S.; Akandere, M. The Effect of Sports on the Psychological Well-Being Levels of High School Students. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2017, 5, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ha, A.S.; Lonsdale, C.; Lubans, D.R.; Ng, J.Y.Y. Increasing Students’ Physical Activity during School Physical Education: Rationale and Protocol for the SELF-FIT Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Public Health 2017, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankonen, N.; Heino, M.T.J.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Sniehotta, F.F.; Sund, R.; Vasankari, T.; Absetz, P.; Borodulin, K.; Uutela, A.; Lintunen, T.; et al. “Let’s Move It”—A School-Based Multilevel Intervention to Increase Physical Activity and Reduce Sedentary Behaviour among Older Adolescents in Vocational Secondary Schools: A Study Protocol for a Cluster-Randomised Trial. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hignett, A.; White, M.P.; Pahl, S.; Jenkin, R.; Froy, M.L. Evaluation of a Surfing Programme Designed to Increase Personal Well-Being and Connectedness to the Natural Environment among ‘at Risk’ Young People. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2018, 18, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, F.K.W.; Louie, L.H.T.; Wong, W.H.-S.; Chan, K.L.; Tiwari, A.; Chow, C.B.; Ho, W.; Wong, W.; Chan, M.; Chen, E.Y.H.; et al. A Sports-Based Youth Development Program, Teen Mental Health, and Physical Fitness: An RCT. Pediatrics 2017, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasimopoulou, S.; Derri, V.; Zervoudaki, E. Children’s Perceptions about Their Health-Related Quality of Life: Effects of a Health Education–Social Skills Program. Health Educ. Res. 2012, 27, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D.R.; Smith, J.J.; Morgan, P.J.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Miller, A.; Lonsdale, C.; Parker, P.; Dally, K. Mediators of Psychological Well-Being in Adolescent Boys. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, P.; Guerrero, J.; Cejudo, J. Improving Adolescents’ Subjective Well-Being, Trait Emotional Intelligence and Social Anxiety through a Programme Based on the Sport Education Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamee, J.; Timken, G.L.; Coste, S.C.; Tompkins, T.L.; Peterson, J. Adolescent Girls’ Physical Activity, Fitness and Psychological Well-Being during a Health Club Physical Education Approach. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noggle, J.J.; Steiner, N.J.; Minami, T.; Khalsa, S.B.S. Benefits of Yoga for Psychosocial Well-Being in a US High School Curriculum: A Preliminary Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. JDBP 2012, 33, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sifers, S.; Shea, D. Evaluations of Girls on the Run/Girls on Track to Enhance Self-Esteem and Well-Being. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2013, 7, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, V.; Allan, J.F. Purposeful Outdoor Learning Empowers Children to Deal with School Transitions. Sports 2019, 7, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedegaard, S.; Christiansen, L.B.; Lund-Cramer, P.; Bredahl, T.; Skovgaard, T. Improving the Well-Being of Children and Youths: A Randomized Multicomponent, School-Based, Physical Activity Intervention. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standage, M.; Cumming, S.; Gillison, F. A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of the Be the Best You Can Be Intervention: Effects on the Psychological and Physical Well-Being of School Children. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.; Burton, S. Implementation and Outcomes of a Responsibility-Based Physical Activity Program Integrated into an Intact High School Physical Education Class. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2008, 27, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–369, W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, P.; Grao-Cruces, A.; Pérez-Ordás, R. Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility Model-Based Programmes in Physical Education: A Systematic Review. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2018, 24, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hernández, J.; Gómez-López, M.; Pérez-Turpin, J.A.; Muñoz-Villena, E. Andreu-Cabrera Perfectly Active Teenagers. When Does Physical Exercise Help Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Cadenas-Sánchez, C.; Estévez-López, F.; Muñoz, N.E.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Migueles, J.H.; Molina-García, P.; Henriksson, H.; Mena-Molina, A.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; et al. Role of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in the Mental Health of Preschoolers, Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1383–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, C.N.; Feig, E.H.; Duque-Serrano, L.; Wexler, D.; Moskowitz, J.T.; Huffman, J.C. Well-Being Interventions for Individuals with Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 147, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, W. A Systematic Review of the Relationship Between Physical Activity and Happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1305–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santurio, J.I.; Fernandez-Rio, J. Violencia, Responsabilidad, Amistad y Necesidades Psicológicas Básicas: Efectos de Un Programa de Educación Deportiva y Responsabilidad Personal y Social. Revista de Psicodidáctica 2016, 21, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.; Gutiérrez, D.; Segovia, Y.; Hopper, T. El modelo de Educación Deportiva en la escuela rural: Amistad, responsabilidad y necesidades psicológicas básicas (The Sport Education model in a rural school: Friendship, responsibility and psychological basic needs). Retos 2020, 38, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santurio, J.I.M.; Fernández-Río, J.; Estrada, J.A.C.; González-Víllora, S. Conexiones entre la victimización en el acoso escolar y la satisfacción-frustración de las necesidades psicológicas básicas de los adolescentes. Revista de Psicodidáctica 2020, 25, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Pulido-González, J.J.; Leo, F.M.; González-Ponce, I.; García-Calvo, T. Effects of an Intervention with Teachers in the Physical Education Context: A Self-Determination Theory Approach. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, B.J.S.A.; Ibáñez, J.C.; Ramírez, C.S.; Valenzuela, A.V.; Mármol, A.G. El modelo de responsabilidad personal y social a través del deporte: Revisión bibliográfica. Retos 2020, 37, 755–762. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Sujective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 463–473. ISBN 978-0-19-513533-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D. Eudaimonic Well-Being, Inequality, and Health: Recent Findings and Future Directions. Int. Rev. Econ. 2017, 64, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huta, V.; Waterman, A.S. Eudaimonia and Its Distinction from Hedonia: Developing a Classification and Terminology for Understanding Conceptual and Operational Definitions. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 1425–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabiese, B.; Obach, A.; Molina, X. The Opportunity to Incorporate Subjective Well-Being in the Protection of Children and Adolescents in Chile. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 2020, 91, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).