Abstract

Background: Nowadays the use of intraoral scanners has become a routine practice in orthodontics. It allows the introduction of many treatment innovations. One should consider to what extent intraoral scanners have influenced the everyday orthodontic practice and in what direction should the further research in this field be conducted. This study is aimed to systematically review and synthesize available controlled trials investigating the accuracy and efficacy of intraoral scanners for orthodontic purpose to provide clinically useful information and to direct further research in this field. Methods: A literature search of free text and MeSH terms was performed by using MedLine (PubMed), Scopus, Web of Science and Embase. The search engines were used to find studies on application of intraoral scanners in orthodontics (from 1950 to 30 September 2020). The following keywords were used: “intraoral scanners AND efficiency AND accuracy AND orthodontics”. Results: The number of potential identified articles was 71, including 61 from PubMed, two from Scopus, three from Web of Science and five from Embase. After removal of duplicates, 67 full-text articles were analyzed for inclusion criteria, 16 of them were selected and finally included in the qualitative synthesis. Conclusions: There are plenty of data available on accuracy and efficacy of different scanners. Scanners of the same generation from different manufacturers have almost identical accuracy. This is the reason why future similar research will not introduce much to the orthodontics. The challenge for the coming years is to find new applications of digital impressions in the orthodontic practice.

1. Introduction

The first intraoral scanner—named CEREC—was developed by Dentsply Sirona (Charlotte, NC, USA) and came into production in 1985. Its purpose was to take the “impression” in order to design fixed prosthetic restorations [1,2]. In 1999 Orthocad (Czestochowa, Poland) introduced the first version of their software, which allowed the study of digital versions of orthodontic casts after proper scanning at the company headquarters, what can be considered as the introduction of 3D models into orthodontics [3]. Since then scanners have improved significantly, providing high quality mapping of both hard and soft tissues, being able to replace traditional plaster models [4]. The inconvenience of pouring and trimming plaster casts as well as the need to take them out of storage on every visit is no longer a must. Nowadays one can view teeth on the computer screen and manipulate them freely in 3D on different devices, which further facilitates communication with a patient [5]. The question asked in the revision on orthodontic scanners from 2015 by Martin et al. “Will intraoral scanners be routinely used in orthodontics?” [3] should be answered in the affirmative. Since then plenty of data in literature are available in which the authors deal with the introduction of scanners in everyday dental practice on the basis of various specialties—prosthodontics, dental surgery or orthodontics. Moreover, the same authors pointed out that intraoral scanners made it possible to introduce innovations in orthodontics such as monitoring dental movement through digital model superimposition [6], aligners [7], further customization of orthodontic appliances such as removable retainers [7] and last but not least, more accurate diagnosis, treatment planning and even simulation of possible orthodontic movement on appropriate software [8,9]. However, one should ask a question to what extent intraoral scanners have influenced the everyday orthodontic practice and in what direction should the further research be conducted to make this technology even more useful for clinicians.

The aim of this study was to systematically review and synthesize available controlled trials investigating the efficiency and accuracy of orthodontic intraoral scanners in order to provide useful information to make clinical decisions, and to direct further research in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was performed according to the PRISMA statement [10] and by following the guidelines from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [11]. The framework of this systematic review according to PICO [12] was: Population: orthodontic patients; Intervention: scanning oral cavity; Comparison: traditional impressions or no intervention; Outcomes: efficiency and accuracy.

2.1. Search Strategy

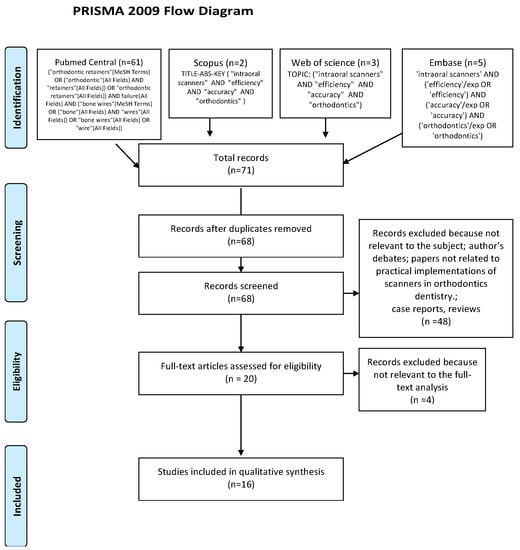

Literature searches of free text and MeSH terms were performed by using MedLine (PubMed), Scopus, Web of Science and Embase (covering from 1950 to 30 September 2020). All searching was performed using a combination of subject headings and free-text terms: we determined the final search strategy through several pre-searches. The keywords used in the search strategy were as follows: (“intraoral scanners AND efficiency AND accuracy AND orthodontics”). Search strategy for MedLine (PubMed Central), Scopus, Web of Science and Embase is presented in Figure 1. Reference lists of primary research reports were cross-checked in an attempt to identify additional studies.

Figure 1.

Prisma Flow Diagram.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were employed for this systematic review: (1) randomized clinical trial (RCT); (2) cohort study; (3) case-control study; (4) articles in the last five years (5) published in English; all the potentially evaluated articles were supposed to explore the subject of development, accuracy and innovatory ways of using scanners in orthodontics. The following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) case reports; (2) reviews; (3) abstract and author debates or editorials; (4) lack of effective statistical analysis; (5) papers not related to practical implementations of scanners in orthodontics or dentistry.

2.3. Data Extraction

Titles and abstracts were independently selected by two authors (M.J. and J.J.-O.), following the inclusion criteria. The full text of each identified article was then analyzed to verify whether it was suitable for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through consensus or by discussion with the third author (M.M.). Authorship, year of publication, type of each eligible study and its relevance regarding the use of scanners in everyday practice were independently extracted by two authors (M.M. and M.J.) and examined by the third author (J.J.-O). Characteristics of the studies included have been presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

2.4. Quality Assessment

According to the PRISMA statements the evaluation of methodological quality gives an indication of the strength of evidence provided by the study, because methodological flaws can result in biases [10].

The quality assessment was performed using Jadad scale for randomized controlled trials for RCT and RCCT studies [13]. It was taken into account in the assessment whether the study was randomized, double-blind with appropriately described methods to find out the level of the risk of bias. A point was given for every characteristic evaluated, when the possible assessment was from zero to five, with a high score indicating a good quality of a study. Notwithstanding, for Case-control Studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Form [14] was used. The quality of all included case-control studies was based on object selection, comparability, and exposure. The possible quality assessment score ranged from zero to nine points with a high score indicating a good quality study. There was one point awarded for each characteristic evaluated.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

The search strategy identified 71 potential articles: 61 from PubMed Central, two from Scopus, three from Web of Science and five from Embase. After removal of duplicates, 67 articles were analyzed. Subsequently, 48 papers were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the remaining 20 papers, four more were excluded because they were not relevant to the subject of the study. The remaining 16 papers were included in the qualitative synthesis. A Prisma 2009 flow diagram representing the study selection process has been presented in Figure 1.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of each of the 16 included studies.

It should also be noted that: (i) five of all included studies focused on comparison of the accuracy and clinical effectiveness of different scanners in relation to one another; (ii) seven studies tried to implement the innovative methods of the use of scanners in the daily work of dental practice. Moreover, five of them focused on both checking accuracy of the scanners and implementing the novelties.

The studies included in this review used a large variety of scanners:

- 3Shape (n studies: 12; 3Shape Trios -n 7- and 3Shape TriPod -n 5-);

- iTero Element (n studies: 4);

- Carestream 3600 (n studies: 4);

- OrthoinSight 3D*-extraoral scanner (n studies: 3)

- Other (n studies: 5)

3.2. Quality Assessment and the Risk of Bias

Quality assessment is shown in Table 2 for the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and in Table 3 for the case-control studies.

Table 2.

Evaluation of included RCTs according to Jadad Scale.

Table 3.

Evaluation of case—control studies according to Newcastle—Ottawa quality assessment.

According to the Jadad scale for RCT, the authors evaluated the qualities of all four clinical trials included in the qualitative synthesis, based on five questions that analyze the randomization process, the experimental blinding and the appropriate time of follow-up. In the evaluation of the quality of RCTs, the total score of three studies was equal to 5, indicating high-quality studies [17,19,26]; while one scored 3, indicating a low-quality study [15]. Blinding is present in three RCT studies (Yilmaz et al. [26] Nalaci et al. [17] and Kim and Lagravére [19], Table 2).

According to the Newcastle–Ottawa scale, the authors evaluated the qualities of all 12 case-control studies included in the qualitative synthesis, based on object selection, comparability, and exposure. In the evaluation of the quality of case-control studies, the total score of eight studies was 9, indicating high-quality studies [15,18,20,21,24,27,28,29]. Then two studies scored 6 [25,30], indicating a medium quality; one 7 [23] and one 8 [22] (Table 3).

4. Discussion

This systematic review endeavored to comprehensively display the available evidence on the efficiency and accuracy of scanners used in orthodontics, in order to document the state of the art and further development.

A total of 16 studies were included in this review, four RCTs and 12 case-control studies. Different scanners were analyzed: 3Shape Trios (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark) in twelve studies, iTero Element (Aligntech, San Jose, CA, USA) in four studies, Carestream 3600 (Carestream, Rochester, NY, USA) in four studies, OrthoinSight 3D* (Motion View Software, LLC, Chattanooga, TN, USA) in three studies, Lavacos (3M, Maplewood, MN, USA) in two studies.

The included studies were critically revised and they focused mainly on: (i) determination of the accuracy of scanning and measurement on digital models of different scanning devices; (ii) implementation of the innovative approaches in the use of intraoral scanners.

4.1. Determining the Accuracy of Scanning and Measurement on Digital Models of Different Scanning Devices

In total there were 10 papers analyzing the accuracy of scanners and measurement on digital casts and their comparability to plaster models and measurements on them [19,22,23,26,30], to models processed by high-efficiency industrial scanners [21,27], evaluation of accuracy of one scanning device in comparison to another [15,20,22,27,28]. All authors underlined that the accuracy of intraoral scans allowed them to replace classic dental models, as the quality of tissue mapping is the same or better than in the classical method [20,23,26,27]. Interestingly, there were no significant differences in the mapping of the oral cavity between the direct and indirect technique, which eliminates the necessity of casting plaster models [21,24]. Furthermore, scanning requires more chairside time, but it was found less unpleasant than standard procedure of impression taking [21]. However, evidence exists that patients when asked which type of impression satisfy them more, choose digital, due to patient-centered outcomes [31]. Some authors pointed out that the results of the studies, which showed the differences in accuracy between different intraoral scanners models, could have significant impact for future research, but the differences in tissue mapping between different models did not significantly alter the clinical evaluation of the orthodontic patient [20,21,22,27]. Solabrietta et al. pointed out that the differences in accuracy between the scanners are rudimentary, and the characteristics that make every daywork easier and more enjoyable for the doctor and the patient seem to be much more important. As example, Lava Cos and Trios 3-Shape intraoral scanners showed similar characteristics, both of them being good enough to carry out needed procedures, but LavaCos requires coating and had a comfortable small tip, whereas the Trios 3-Shape scanner had a larger tip and worked much faster [20]. In the study of Jacob et al. all, scanners used in the study (iTero element, Lythos, Ortho Insight 3D) showed similar and reliable measures. However, the most errors were found in the Ortho Insight 3D measurements, as on its arch length and canine height were systematically underestimated [15]. One must remember that this scanner does not shorten the working time as it does not allow one to avoid the impression-taking procedure.

It is easy to behold that the topic of comparing the accuracy of digital models is extremely popular and has been present in the literature for so long that separate systematic reviews have been developed about it [4]. The results of included studies lead to the general statement that for clinical purposes, deviations in the accuracy between the different scanners are irrelevant [15,20,22,27,28]. Naturally, new papers are constantly being published, however, they focus more often on implantology, where accuracy on smaller orders of magnitude can make a difference [32,33]. For the purposes of orthodontists, however, until a new generation of products hits the market, further studies seem redundant, and the accuracy of current devices seems to be at least satisfactory.

The prices of scanners of different manufacturers are comparable. However, extraoral scanners seem to be a cheaper alternative to intraoral scanners when used for longer period of time. The 3Shape Trios has been marketed since 2015. Its average cost is about $35,000 for the current version scanner and $3500/year for a subscription to the dedicated PC software. The iTero Element is marketed since 2015 with a cost of $28,000 for the current version scanner and $4320/year for a subscription to the dedicated PC software. The Carestream CS 3600 is marketed since 2016 at a cost of $40,000 for the scanner and $2,200$/year for a subscription to dedicated PC software. Currently 3M (St. Paul, MN, USA) offers the True Definition scanner for $17,000$ for the current version scanner and $230/year for a subscription to dedicated PC software.

3Shape Tripods are marketed since 2012 at a cost of $31,000 for the current version of the scanner and $1900 for a subscription to the dedicated PC software. The OrthoinSight 3D is marketed since 2012. Its price, however, is not openly available either on the manufacturer’s website or at any local provider.

Other factors, which should affect the choice of proper scanner, are the consistency of software and solutions proposed by the producer. One should pay attention to the cooperation between the office and the final user of the scan—the dental technician.

4.2. The Innovative Approaches in Use of Intraoral Scanners

The presence of intraoral scanners in orthodontic practice has already revolutionized many types of treatment. When treatment with Invisalign’s transparent aligners was introduced in 1997, laser scans were approached with caution [34]. It involved converting PVS impressions to computer scans at the company’s premises [35]. After the iTero scanners were launched on the market and the physician-technician communication was transferred to the Clinchek platform, access to this technology was facilitated, treatment planning and monitoring was improved, and its efficiency increased [36]. Is there a chance for an innovative proposal, thanks to which scanners will once again change orthodontic practices? In the remaining 11 included papers, authors proposed some innovations in the use of intraoral scanners.

Among them there should be distinguished:

- (a)

- New improvements in general use

- -

- proposing a new training to maximize the efficiency of dental hygienist [16]

- -

- orthodontic movement monitoring in quicker and much more comfortable way than before [17]

- -

- finding that full intraoral scans are perfectly reliable for orthodontic cases, but still not useful for prosthetic cases, where up to 3 segments should be scanned [21]

- -

- using the digital scans as exact for documentation of palatal soft tissue [23]

- -

- the innovative method of scanning the palate, ensuring its most faithfully reproduction on the digital model [24]

- -

- finding that when clinician depend on digital models, it is best to use ceramic brackets as they provide the lowest discrepancy of measurements [28]

- -

- finding that scanning method, which provides most accurate digital casts is when scanning begins from tooth #12 up to tooth #17, and then from tooth #12 up to tooth #27 [25]

In order to monitor orthodontic treatment, the standard is the periodic repetition of radiological examinations such as a panoramic radiograph or cephalogram, what is evidenced by the methods used in many recently published studies [37,38]. However, the radiation of patients should be minimized, especially during their period of growth [39]. On the other hand, comparing the measurements performed on the model and in the patient’s oral cavity in vivo may be burdened with considerable operator error [40]. Scanners seem to be an ideal, accurate and safe alternative in this case. It is encouraging that clinicians appreciate a feature that only scanners can provide, i.e., assessments of soft tissue features such as exact shape, which changes gradually throughout the treatment, [24] and color, saturation or swelling [21,23]. It is also interesting that the type of brackets is quite important for the fidelity of turning the tooth surface through the scanner [28]. It is such studies, with specific clinical recommendations, that can spread the use of scanners and increase their efficiency.

- (b)

- Completely new applications in the use of scanners

- -

- use rugae palatine patterns on digital scans in order to identify individuals [18]

- -

- determine the occlusal contacts in a novel way [20]

- -

- display in more accurate way the interdental areas in periodontal patients directly in patients’ mouth [29]

- -

- finding centric relation only by using intraoral scanner [30]

Moreover, an increasing trend is to treat patients centrally, which, according to many doctors, ensures greater stability of treatment [41]. The growing popularity of courses in line with the Functional and Cosmetic Excellence (FACE) philosophy is not without significance [42]. Currently, accurate determination of occlusal contacts and the articulation of the patient are a tedious process that often requires a team of many people and the help of a technician. The proposed methods could significantly shorten the patient’s articulation process and, secondly, make it more common [20,30]. Interestingly, intraoral scanner was used to identify people [18] and it shows the skill of scanners to carefully assess the palatal soft tissue, proven by Deferm et al. [23] Assessment of the condition of the palate is an important part of monitoring the progress of orthodontic treatment as well as monitoring the interdental areas in periodontal patients during orthodontic therapy [29]. These are the new and interesting proposals, that the world of scanners needs to keep growing.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, included studies focused on scanners’ development and implementation to solve many challenging elements of orthodontic therapy. On the other hand, there are plenty of data available on accuracy and efficacy as well as mapping comparisons of different scanners. Scanners of the same generation from different manufacturers have almost identical accuracy. This is the reason why similar research will not introduce much to the orthodontic case evaluation or treatment. Any new reports should focus solely on comparing the new, untested models. Scanners are a modern, adequate and increasingly accessible source for capturing and imaging the appearance of oral tissues. The challenge for the coming years is to find new applications of digital impressions and imagining in the orthodontic practice. In the upcoming studies scanners should serve only as a tool for observing clinical phenomena.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J. and J.J.-O.; Methodology, M.J.; Formal Analysis, M.J., M.M. and J.J.-O.; Investigation, M.J.; Resources, J.J.-O.; Data Curation, M.J., Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.J. and J.J.-O.; Writing—Review & Editing, M.J., J.J.-O. and M.M.; Visualization, K.G.; Supervision, J.J.-O. and K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Abbreviations

| RCT | randomized control trial |

| RCCT | randomized control clinical trial |

| 3D | three dimensional; |

| CT | computed tomography |

References

- Sannino, G.; Germano, F.; Arcuri, L.; Bigelli, E.; Arcuri, C.; Barlattani, A. CEREC CAD/CAM Chairside System. Oral Implant. 2015, 7, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mörmann, W.; Brandestini, M.; Ferru, A.; Lutz, F.; Krejci, I. Marginal adaptation of adhesive porcelain inlays in vitro. Schweiz Mon. Zahnmed 1985, 95, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C.B.; Chalmers, E.V.; McIntyre, G.T.; Cochrane, H.; Mossey, P.A. Orthodontic scanners: What’s available? J. Orthod. 2015, 42, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragón, M.L.C.; Pontes, L.F.; Bichara, L.M.; Flores-Mir, C.; Normando, D. Validity and reliability of intraoral scanners compared to conventional gypsum models measurements: A systematic review. Eur. J. Orthod. 2016, 38, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjögren, A.; Lindgren, J.E.; Huggare, J.Å.V. Orthodontic Study Cast Analysis—Reproducibility of Recordings and Agreement between Conventional and 3D Virtual Measurements. J. Digit. Imaging 2009, 23, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.J.; Pham, J.; Choy, M.; Weissheimer, A.; Dougherty, H.L., Jr.; Sameshima, G.T.; Tong, H. Monitoring of typodont root movement via crown superimposition of single cone-beam computed tomography and consecutive intraoral scans. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 145, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravitz, N.D.; Groth, C.; Jones, P.E.; Graham, J.W.; Redmond, W.R. Intraoral digital scanners. J. Clin. Orthod. 2014, 48, 337–347. [Google Scholar]

- Grünheid, T.; McCarthy, S.D.; Larson, B.E. Clinical use of a direct chairside oral scanner: An assessment of accuracy, time, and patient acceptance. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 146, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, F.; Gandolfi, A.; Luongo, G.; Logozzo, S. Intraoral scanners in dentistry: A review of the current literature. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2011; Available online: www.handbook.cochrane.org (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Sackett, D.L.; Strauss, S.E.; Richardson, W.S.; Rosenberg, W.; Haynes, B.R. Evidence-Based mMedicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Churchill Livingstone: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jadad, A.R.; Moore, R.A.; Carroll, D.; Jenkinson, C.; Reynolds, D.J.; Gavaghan, D.J.; McQuay, H.J. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control. Clin. Trials 1996, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of case-control studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, H.B.; Wyatt, G.D.; Buschang, P.H. Reliability and validity of intraoral and extraoral scanners. Prog. Orthod. 2015, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.-R.; Park, J.-M.; Chun, Y.-S.; Lee, K.-N.; Kim, M.-J. Changes in views on digital intraoral scanners among dental hygienists after training in digital impression taking. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalcaci, R.; Altan, A.B.; Bicakci, A.A.; Ozturk, F.; Babacan, H. A reliable method for evaluating upper molar distalization: Superimposition of three-dimensional digital models. Korean J. Orthod. 2015, 45, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Taneva, E.D.; Johnson, A.; Viana, G.; Evans, C.A. 3D evaluation of palatal rugae for human identification using digital study models. J. Forensic Dent. Sci. 2015, 7, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lagravere, M. Accuracy of Bolton analysis measured in laser scanned digital models compared with plaster models (gold standard) and cone-beam computer tomography images. Korean J. Orthod. 2016, 46, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaberrieta, E.; Garmendia, A.; Brizuela, A.; Otegi, J.R.; Pradies, G.; Szentpétery, A. Intraoral Digital Impressions for Virtual Occlusal Records: Section Quantity and Dimensions. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 7173824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesemann, C.; Muallah, J.; Mah, J.; Bumann, A. Accuracy and efficiency of full-arch digitalization and 3D printing: A comparison between desktop model scanners, an intraoral scanner, a CBCT model scan, and stereolithographic 3D printing. Quintessence Int. 2017, 48, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.-M. Comparison of two intraoral scanners based on three-dimensional surface analysis. Prog. Orthod. 2018, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deferm, J.; Schreurs, R.; Baan, F.; Bruggink, R.; Merkx, M.A.W.; Xi, T.; Bergé, S.J.; Maal, T.J.J. Validation of 3D documentation of palatal soft tissue shape, color, and irregularity with intraoral scanning. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhongpeng, Y.; Xu, T.; Ruoping, J. Deviations in palatal region between indirect and direct digital models: An in vivo study. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favero, R.; Volpato, A.; De Francesco, M.; Di Fiore, A.; Guazzo, R.; Favero, L. Accuracy of 3D digital modeling of dental arches. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, H.; ÇakmakÖzlü, F.; Karadeniz, C.; Karadeniz, E.İ. Time-Efficiency and Accuracy of Three-Dimensional Models Versus Dental Casts: A Clinical Study. Turk. J. Orthod. 2019, 32, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Gkantidis, N. Trueness and precision of intraoral scanners in the maxillary dental arch: An in vivo analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Kim, M.-J. Accuracy on Scanned Images of Full Arch Models with Orthodontic Brackets by Various Intraoral Scanners in the Presence of Artificial Saliva. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 2920804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenz, M.A.; Schubert, V.; Schmidt, A.; Wöstmann, B.; Ruf, S.; Klaus, K. Digital versus Conventional Impression Taking Focusing on Interdental Areas: A Clinical Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafeev, A.; Ryakhovsky, A.; Petrov, P.; Chikunov, S.; Khizhuk, A.; Bykova, M.; Vuraki, N. Comparative Analysis of the Reproduction Accuracy of Main Methods for Finding the Mandible Position in the Centric Relation Using Digital Research Method. Comparison between Analog-to-Digital and Digital Methods: A Preliminary Report. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joda, T.; Brägger, U. Patient-centered outcomes comparing digital and conventional implant impression procedures: A randomized crossover trial. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2016, 27, e185–e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, F.G.; Hauschild, U.; Veronesi, G.; Imburgia, M.; Mangano, C.; Admakin, O. Trueness and precision of 5 intraoral scanners in the impressions of single and multiple implants: A comparative in vitro study. BMC Oral. Health 2019, 19, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelcu, R.; Olsson, P.; Nyström, I.; Thor, A. Finish line distinctness and accuracy in 7 intraoral scanners versus conventional impression: An in vitro descriptive comparison. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, B.H. Invisalign A to Z. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2002, 121, 540–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, E.; Miller, R.J. Automated custom-manufacturing technology in orthodontics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2003, 123, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haouili, N.; Kravitz, N.D.; Vaid, N.R.; Ferguson, D.J.; Makki, L. Has Invisalign improved? A prospective follow-up study on the efficacy of tooth movement with Invisalign. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2020, 158, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavoni, C.; Franchi, L.; Laganà, G.; Cozza, P. Radiographic assessment of maxillary incisor position after rapid maxillary expansion in children with clinical signs of eruption disorder. J. Orofac. Orthop. Fortschr. Kieferorthopädie 2013, 74, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Kim, J.-W.; Yoon, I.-Y.; Rhee, C.S.; Lee, C.H.; Yun, P.-Y. Influencing factors on the effect of mandibular advancement device in obstructive sleep apnea patients: Analysis on cephalometric and polysomnographic parameters. Sleep Breath. 2014, 18, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelid, I.; Mejàre, I.; Weerheijm, K. EAPD guidelines for use of radiographs in children. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2003, 4, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Caccianiga, G.; Paiusco, A.; Perillo, L.; Nucera, R.; Pinsino, A.; Maddalone, M.; Cordasco, G.; Lo Giudice, A. Does Low-Level Laser Therapy Enhance the Efficiency of Orthodontic Dental Alignment? Results from a Randomized Pilot Study. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea, C.M.; Badea, M.E.; Vasilache, S.; Mesaroș, M. Effects of CO-CR Discrepancy in Daily Orthodontic Treatment Planning. Clujul. Med. 2016, 89, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Course of Facial and Clinical Excellence. Available online: http://www.fullfacecourse.com/philosophy.php (accessed on 20 October 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).