Protective Factors for LGBTI+ Youth Wellbeing: A Scoping Review Underpinned by Recognition Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Orientations and Identities

1.2. Wellbeing and Stigmatisation

1.3. Social Justice as a Pre-Requisite for Wellbeing

1.4. Rationale and Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Search and Study Selection

2.3. Data Charting and Summarising Results

2.4. Content and Thematic Analysis

2.5. Consultation

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

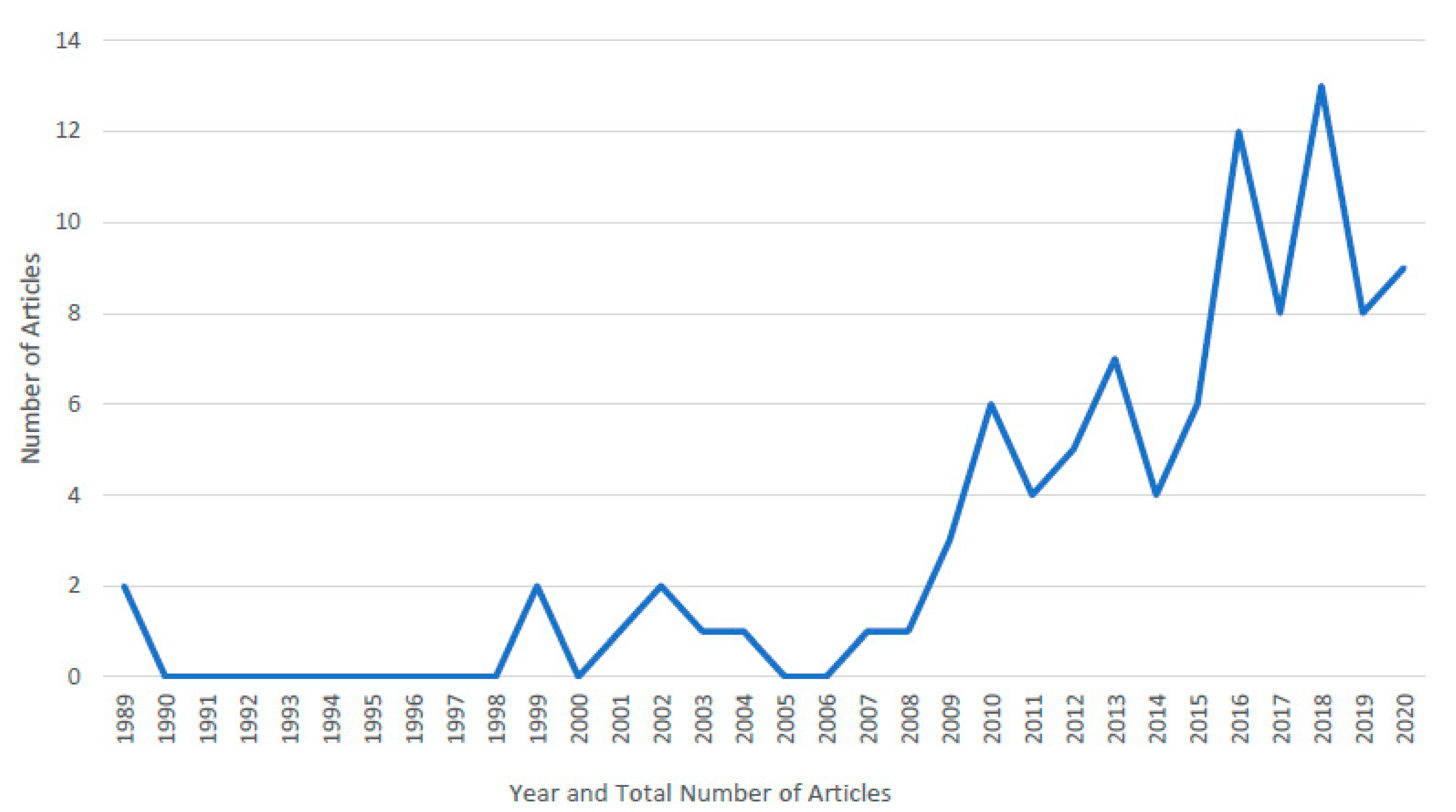

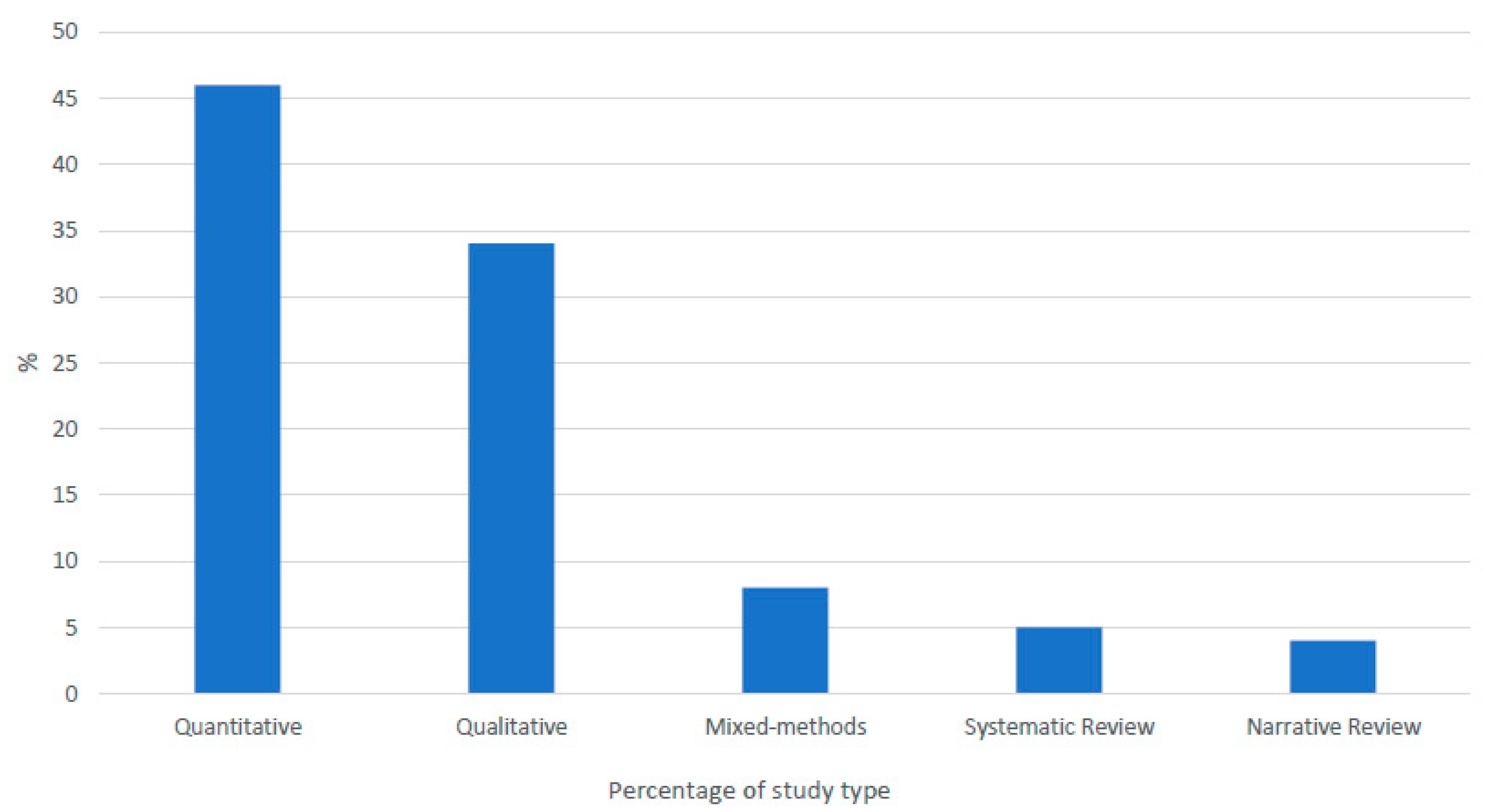

3.2. Overview of Documented Records

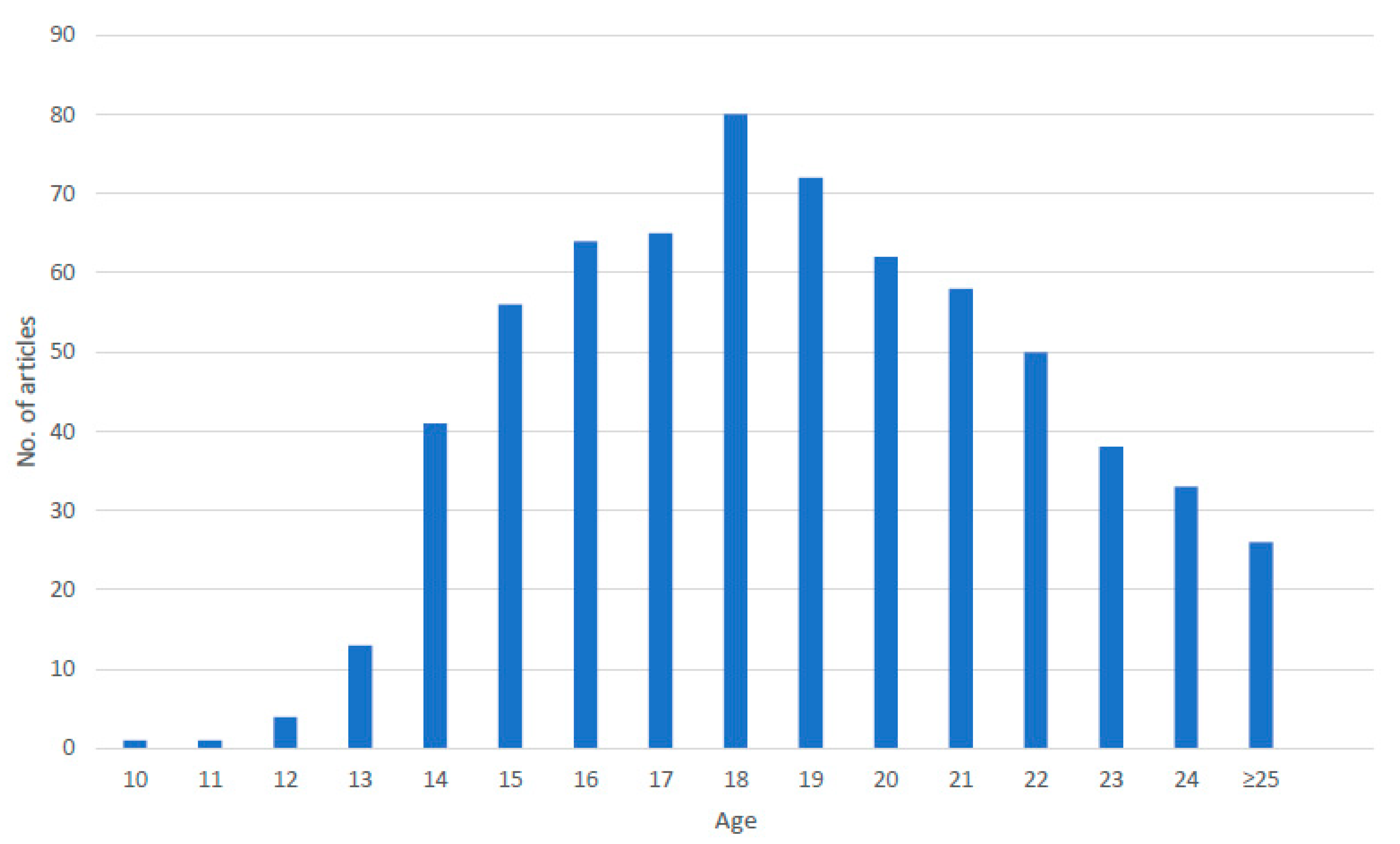

3.3. Demographic Overview

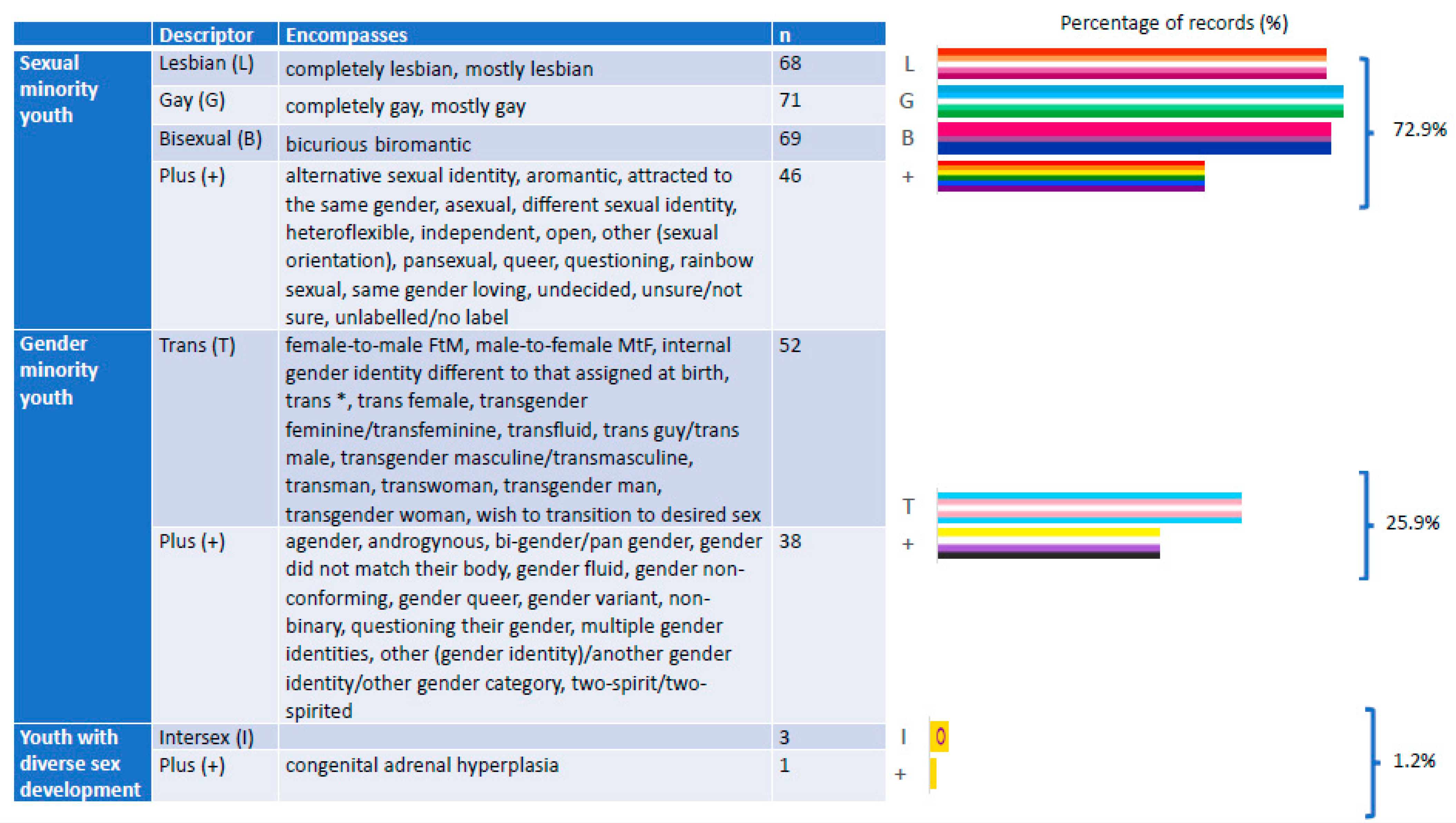

3.3.1. Orientations and Identities

3.3.2. Self-Descriptors

3.3.3. Being “Out”

3.3.4. Age

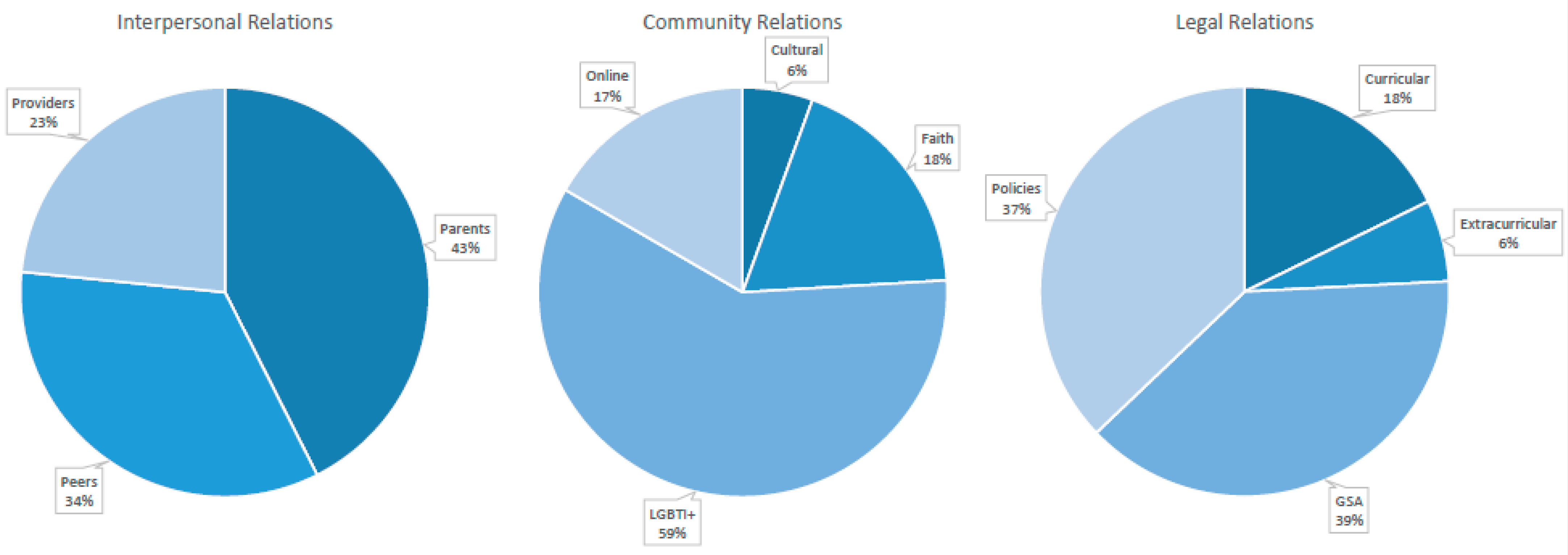

3.4. Intersubjective Recognition

3.4.1. Parents

3.4.2. Peers

3.4.3. Providers

3.5. Community Connectedness

3.5.1. LGBTI+ Communities

3.5.2. Online Communities

3.5.3. Faith Communities

3.5.4. Cultural Communities

3.6. Inclusion through Universal Rights

3.6.1. Gay–Straight Alliances/Gender–Sexuality Alliances (GSAs)

3.6.2. Policies

3.6.3. Curricular

3.6.4. Extracurricular Activities

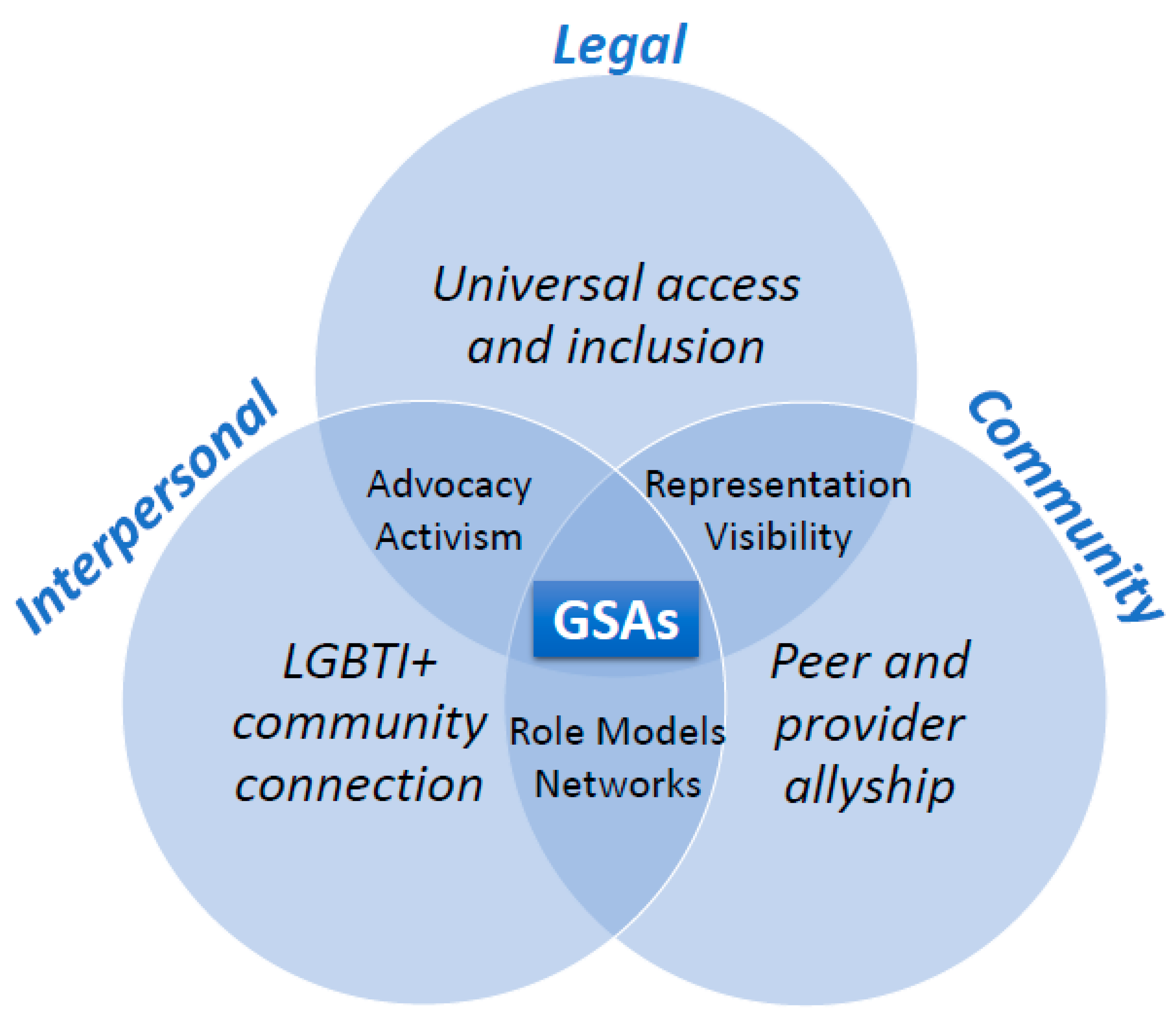

3.7. Intersecting Forms of Recognition

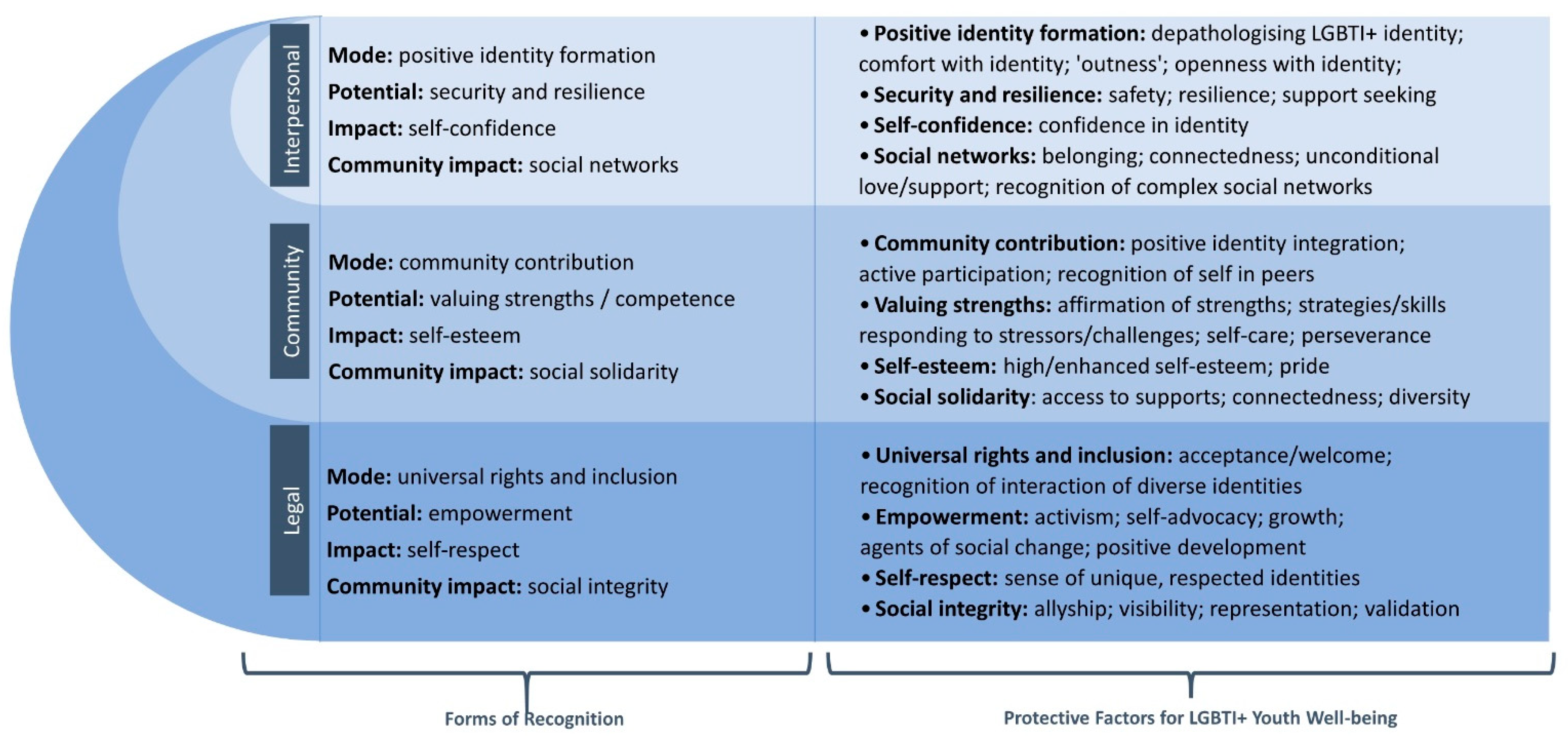

3.8. Indicators of Wellbeing

3.9. Consultations

4. Discussion

4.1. Multi-Faceted Orientations and Identities

4.2. Broadening Understandings of Family

4.3. Salience of Community Connectedness

4.4. Shifts from Protectionisism to Rights-Based, Universal Inclusion

4.5. Mental Health beyond a Dichotomy

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist

| Section | Item | PRISMA-ScR Checklist Item | Reported on Page No. |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 3 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 3 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 3 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 4 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 4 |

| Selection of sources of evidence | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 3–4 |

| Data charting process | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 4 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 4 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | N/A |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 4 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 5 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 6–26 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | N/A |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 6–26 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 25–36 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 36–39 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 39–40 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 40 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 41 |

References

- World Health Organization. Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice: Report of the World Health Organization; Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, in Collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation and the University of Melbourne: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/en/promoting_mhh.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Dooris, M.; Farrier, A.; Froggett, L. Wellbeing: The challenge of ‘operationalising’ an holistic concept within a reductionist public health programme. Perspect. Public Health 2017, 138, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, R.; Daly, A.P.; Huyton, J.; Sanders, L.D. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2012, 2, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, A.P.; Eliason, M.; Mays, V.M.; Mathy, R.M.; Cochran, S.D.; D’Augelli, A.R.; Silverman, M.M.; Fisher, P.W.; Hughes, T.; Rosario, M.; et al. Suicide and Suicide Risk in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Populations: Review and Recommendations. J. Homosex. 2010, 58, 10–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Ylioja, T.; Lackey, M. Identifying Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Search Terminology: A Systematic Review of Health Systematic Reviews. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, G.J. How Many People Are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender; The Williams Institute, UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.M. LGBT Identification Rises to 5.6% in Latest U.S. Estimate. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Roen, K. Intersex or Diverse Sex Development: Critical Review of Psychosocial Health Care Research and Indications for Practice. J. Sex Res. 2018, 56, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Understanding the Well-Being of LGBTQI+ Populations; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.T.; Sheehan, A.E.; Walsh, R.F.; Sanzari, C.M.; Cheek, S.M.; Hernandez, E.M. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 74, 101783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucassen, M.F.; Stasiak, K.; Samra, R.; Frampton, C.M.; Merry, S.N. Sexual minority youth and depressive symptoms or depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2017, 51, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshal, M.P.; Dietz, L.J.; Friedman, M.S.; Stall, R.; Smith, H.A.; McGinley, J.; Thoma, B.C.; Murray, P.J.; D’Augelli, A.R.; Brent, D.A. Suicidality and Depression Disparities Between Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 49, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Solid Facts: Social Determinants of Health, 2nd ed.; International Centre for Health and Society, WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003; Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/98438/e81384.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding; The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M. The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, A. A Sociological Critique of Youth Strategies and Educational Policies that Address LGBTQ Youth Issues. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2019, 1, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A.; Mayock, P. Supporting LGBT Lives? Complicating the suicide consensus in LGBT mental health research. Sexualities 2016, 20, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.M.; Marx, R.A. The persistence of policies of protection in LGBTQ research & advocacy. J. LGBT Youth 2018, 15, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D. Popular culture, the ‘victim’ trope and queer youth analytics. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2010, 23, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talburt, S.; Rofes, E.; Rasmussen, M.L. Transforming Discourses of Queer Youth. In Youth and Sexualities: Pleasure, Subversion, and Insubordination in and Out of Schools; Rasmussen, M.L., Rofes, E., Talburt, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams, R.C. The New Gay Teenager; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mayock, P.; Bryan, A.; Carr, N.; Kitching, K. Supporting LGBT Lives: A Study of the Mental Health and Well-Being of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People; GLEN/BeLonGTo: Dublin, Ireland, 2009; Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/mentalhealth/suporting-lgbt-lives.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Higgins, A.; Doyle, L.; Downes, C.; Murphy, R.; Sharek, D.; DeVries, J.; Begley, T.; McCann, E.; Sheerin, F.; Smyth, S. The LGBTIreland Report: National Study of the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex People in Ireland; GLEN/BeLonGTo: Dublin, Ireland, 2016; Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/mental-health-services/connecting-for-life/publications/lgbt-ireland-report.html (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- World Health Organization. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion: An International Conference on Health Promotion, The Move Towards a New Public Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Honneth, A. Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the “Postsocialist” Condition; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Honneth, A. The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Honneth, A. Recognition and Moral Obligation. Soc. Res. 1997, 64, 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N.; Honneth, A. Redistribution or Recognition? A Political-Philosophical Exchange; Verso: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K.; Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Kastner, M.; Levac, D.; Ng, C.; Sharpe, J.P.; Wilson, K.; et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daudt, H.M.L.; Van Mossel, C.; Scott, S.J. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceatha, N.; Bustillo, M.; Tully, L.; James, O.; Crowley, D. What is known about the protective factors that promote LGBTI+ youth wellbeing? A scoping review protocol. HRB Open Res. 2020, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceatha, N. Scoping review protocol on protective factors that promote LGBTI+ youth wellbeing. Open Sci. Framew. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.R. Social Acceptance of LGBT People in 174 Countries 1981 to 2017; The Williams Institute, UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/GAI-Update-Oct-2019.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Medline, T. Selecting Studies for Systematic Review: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. Contemp. Issues Commun. Sci. Disord. 2006, 33, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, M.; Peterson, K.; Raina, P.; Chang, S.; Shekelle, P. Avoiding Bias in Selecting Studies. Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2013. Available online: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Peters, M.D.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Évid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, R.; Hendry, M.; Aslam, R.; Booth, A.; Carter, B.; Charles, J.M.; Craine, N.; Edwards, R.T.; Noyes, J.; Ntambwe, L.I.; et al. Intervention Now to Eliminate Repeat Unintended Pregnancy in Teenagers (INTERUPT): A systematic review of intervention effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and qualitative and realist synthesis of implementation factors and user engagement. Health Technol. Assess. 2016, 20, 1–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundy, L. ‘Voice’ is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 33, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, L. In defence of tokenism? Implementing children’s right to participate in collective decision-making. Childhood 2018, 25, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, R. Participation in practice: Making it meaningful, effective and sustainable. Child. Soc. 2004, 18, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawn, L.; Welsh, P.; Kirkpatrick, L.; Webster, L.A.; Stain, H.J. Getting it right! Enhancing youth involvement in mental health research. Health Expect. 2015, 19, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennehy, R.; Cronin, M.; Arensman, E. Involving young people in cyberbullying research: The implementation and evaluation of a rights-based approach. Health Expect. 2018, 22, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceatha, N. ‘Learning with’ dogs: Human–animal bonds and understandings of relationships and reflexivity in practitioner-research. Aotearoa N. Z. Soc. Work. 2020, 32, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, K.; Beagan, B. Making Assumptions, Making Space: An Anthropological Critique of Cultural Competency and Its Relevance to Queer Patients. Med. Anthr. Q. 2014, 28, 578–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, A.; Campbell, P.; Struthers, C.; Synnot, A.; Nunn, J.; Hill, S.; Goodare, H.; Morris, J.; Watts, C.; Morley, R. Development of the ACTIVE framework to describe stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2019, 24, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Költő, A.; Vaughan, E.; O’Sullivan, L.; Kelly, C.; Saewyc, E.M.; Nic Gabhainn, S. LGBTI+ Youth in Ireland and Across Europe: A Two-Phased Landscape and Research Gap Analysis; Health Promotion Research Centre, National University of Ireland Galway, Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth: Dublin, Ireland. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/135654/4d466c48-34d9-403a-b48e-fdcfb7931320.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- McDermott, E.; Gabb, J.; Eastham, R.; Hanbury, A. Family trouble: Heteronormativity, emotion work and queer youth mental health. Health Interdiscip. J. Soc. Study Health Illn. Med. 2019, 25, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, R.; Wheldon, C.; Russell, S.T. How Does Sexual Identity Disclosure Impact School Experiences? J. LGBT Youth 2015, 12, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L.M.; Lucas, S. Sexual-Minority and Heterosexual Youths’ Peer Relationships: Experiences, Expectations, and Implications for Well-Being. J. Res. Adolesc. 2004, 14, 313–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, C.; Case, R.; Anderson, A. Internalized homophobia and depression in lesbian women: The protective role of pride. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2018, 30, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, N.D.; Willoughby, B.L.B.; Lindahl, K.M.; Malik, N.M. Sexuality Related Social Support Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 1134–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bry, L.J.; Mustanski, B.; Garofalo, R.; Burns, M.N. Management of a Concealable Stigmatized Identity: A Qualitative Study of Concealment, Disclosure, and Role Flexing Among Young, Resilient Sexual and Gender Minority Individuals. J. Homosex. 2016, 64, 745–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, L.A.; Bell, T.S.; Benibgui, M.; Helm, J.L.; Hastings, P.D. The buffering effect of peer support on the links between family rejection and psychosocial adjustment in LGB emerging adults. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 35, 854–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, L.; Darnell, D.A.; Rhew, I.C.; Lee, C.M.; Kaysen, D. Resilience in Community: A Social Ecological Development Model for Young Adult Sexual Minority Women. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 55, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Children and Youth Affairs. National Youth Strategy 2015–2020; DCYA, Government Publications: Dublin, Ireland, 2014; Available online: https://www.youth.ie/documents/national-youth-strategy-2015-2020/ (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Department of Children and Youth Affairs. Better Outcomes, Brighter Futures: The National Policy Framework for Children and Young People 2014–2020; DCYA, Government Publications: Dublin, Ireland, 2014. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/23796/961bbf5d975f4c88adc01a6fc5b4a7c4.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Veale, J.F.; Peter, T.; Travers, R.; Saewyc, E. Enacted Stigma, Mental Health, and Protective Factors Among Transgender Youth in Canada. Transgender Health 2017, 2, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taliaferro, L.A.; Muehlenkamp, J.J. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Suicidality Among Sexual Minority Youth: Risk Factors and Protective Connectedness Factors. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BourisVincent, A.; Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Pickard, A.; Shiu, C.; Loosier, P.S.; Dittus, P.; Gloppen, K.; Waldmiller, J.M. A Systematic Review of Parental Influences on the Health and Well-Being of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth: Time for a New Public Health Research and Practice Agenda. J. Prim. Prev. 2010, 31, 273–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poteat, V.P.; Calzo, J.; Yoshikawa, H.; Lipkin, A.; Ceccolini, C.J.; Rosenbach, S.B.; O’Brien, M.D.; Marx, R.A.; Murchison, G.; Burson, E. Greater Engagement in Gender-Sexuality Alliances (GSAs) and GSA Characteristics Predict Youth Empowerment and Reduced Mental Health Concerns. Child Dev. 2019, 91, 1509–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.; Cariola, L.A. LGBTQI+ Youth and Mental Health: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2019, 5, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taliaferro, L.A.; McMorris, B.J.; Nic Rider, G.; Eisenberg, M.E. Risk and Protective Factors for Self-Harm in a Population-Based Sample of Transgender Youth. Arch. Suicide Res. 2018, 23, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poštuvan, V.; Podlogar, T.; Šedivy, N.Z.; De Leo, D. Suicidal behaviour among sexual-minority youth: A review of the role of acceptance and support. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2019, 3, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, M.E.; Mehus, C.J.; Saewyc, E.M.; Corliss, H.; Gower, A.L.; Sullivan, R.; Porta, C.M. Helping Young People Stay Afloat: A Qualitative Study of Community Resources and Supports for LGBTQ Adolescents in the United States and Canada. J. Homosex. 2017, 65, 969–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhardt, L.S.; Xie, H.; Wesp, L.M.; Murray, J.R.; Apchemengich, I.; Kioko, D.; Weinhardt, C.B.; Cook-Daniels, L. The Role of Family, Friend, and Significant Other Support in Well-Being Among Transgender and Non-Binary Youth. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2018, 15, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansfaçon, A.P.; Hébert, W.; Lee, E.O.J.; Faddoul, M.; Tourki, D.; Bellot, C. Digging beneath the surface: Results from stage one of a qualitative analysis of factors influencing the well-being of trans youth in Quebec. Int. J. Transgend. 2018, 19, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehus, C.J.; Watson, R.J.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Corliss, H.L.; Porta, C.M. Living as an LGBTQ Adolescent and a Parent’s Child: Overlapping or Separate Experiences. J. Fam. Nurs. 2017, 23, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snapp, S.D.; Watson, R.; Russell, S.T.; Diaz, R.M.; Ryan, C. Social Support Networks for LGBT Young Adults: Low Cost Strategies for Positive Adjustment. Fam. Relat. 2015, 64, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higa, D.; Hoppe, M.J.; Lindhorst, T.; Mincer, S.; Beadnell, B.; Morrison, D.M.; Wells, E.A.; Todd, A.; Mountz, S. Negative and Positive Factors Associated with the Well-Being of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Questioning (LGBTQ) Youth. Youth Soc. 2012, 46, 663–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, C.; Russell, S.T.; Huebner, D.; Diaz, R.; Sanchez, J. Family Acceptance in Adolescence and the Health of LGBT Young Adults. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2010, 23, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.S.; Saltzburg, S.; Locke, C.R. Supporting the emotional and psychological well being of sexual minority youth: Youth ideas for action. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2009, 31, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby-Mullins, P.; Murdock, T.B. The Influence of Family Environment Factors on Self-Acceptance and Emotional Adjustment Among Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Adolescents. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2007, 3, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detrie, P.M.; Lease, S.H. The Relation of Social Support, Connectedness, and Collective Self-Esteem to the Psychological Well-Being of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth. J. Homosex. 2007, 53, 173–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Arayasirikul, S.; Raymond, H.; McFarland, W. The Impact of Discrimination on the Mental Health of Trans*Female Youth and the Protective Effect of Parental Support. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 2203–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, L.; Schrager, S.M.; Clark, L.F.; Belzer, M.; Olson, J. Parental Support and Mental Health Among Transgender Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 791–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, F.J.; Stein, T.S.; Harter, K.S.M.; Allison, A.; Nye, C.L. Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Youths: Separation-Individuation, Parental Attitudes, Identity Consolidation, and Well-Being. J. Youth Adolesc. 1999, 28, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, A.L.; Nic Rider, G.; Brown, C.; McMorris, B.J.; Coleman, E.; Taliaferro, L.A.; Eisenberg, M.E. Supporting Transgender and Gender Diverse Youth: Protection Against Emotional Distress and Substance Use. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin-Williams, R.C. Parental Influences on the Self-Esteem of Gay and Lesbian Youths. J. Homosex. 1989, 17, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, M.M.; Beltran, O.; Armstrong, H.; Jayne, P.E.; Barrios, L.C. Protective Factors Among Transgender and Gender Variant Youth: A Systematic Review by Socioecological Level. J. Prim. Prev. 2018, 39, 263–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savin-Williams, R.C. Coming Out to Parents and Self-Esteem Among Gay and Lesbian Youths. J. Homosex. 1989, 18, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.C.; LeBlanc, A.J.; Sterzing, P.R.; Deardorff, J.; Antin, T.; Bockting, W.O. Trans adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of their parents’ supportive and rejecting behaviors. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 67, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanhere, M.; Fuqua, J.S.; Rink, R.C.; Houk, C.P.; Mauger, D.T.; Lee, P.A. Psychosexual development and quality of life outcomes in females with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Int. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toomey, R.; Russell, S.T. Gay-Straight Alliances, Social Justice Involvement, and School Victimization of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Youth. Youth Soc. 2011, 45, 500–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustanski, B.; Newcomb, M.E.; Garofalo, R. Mental Health of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youths: A Developmental Resiliency Perspective. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2011, 23, 204–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheets, R.L.; Mohr, J.J. Perceived social support from friends and family and psychosocial functioning in bisexual young adult college students. J. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 56, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.J. Psychosocial Risk and Protective Factors for Depression Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Youth: A Systematic Review. J. Homosex. 2017, 65, 263–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, E.; Birkett, M.A.; Mustanski, B. Typologies of Social Support and Associations with Mental Health Outcomes Among LGBT Youth. LGBT Health 2015, 2, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, R.J.; Grossman, A.H.; Russell, S.T. Sources of Social Support and Mental Health Among LGB Youth. Youth Soc. 2016, 51, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenaughty, J.; Harré, N. Life on the Seesaw. J. Homosex. 2003, 45, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, J.J.; Sarno, E.L. The ups and downs of being lesbian, gay, and bisexual: A daily experience perspective on minority stress and support processes. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M. “Gay capital” in gay student friendship networks. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 35, 1183–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, S.W.; Dyar, C.; Newcomb, M.E.; Mustanski, B. Romantic involvement: A protective factor for psychological health in racially-diverse young sexual minorities. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018, 127, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galupo, M.P.; John, S.S. Benefits of cross-sexual orientation friendships among adolescent females. J. Adolesc. 2001, 24, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.S.; Harper, G.W.; Sánchez, B.; Fernández, M.I. Examining natural mentoring relationships (NMRs) among self-identified gay, bisexual, and questioning (GBQ) male youth. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauermeister, J.A.; Johns, M.M.; Sandfort, T.G.M.; Eisenberg, A.; Grossman, A.H.; D’Augelli, A.R. Relationship Trajectories and Psychological Well-Being Among Sexual Minority Youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 1148–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, T.J.; Hastings, S.L. Resilience Among Rural Lesbian Youth. J. Lesbian Stud. 2010, 14, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, M.; Chow, S.; Scanlon, C.P. Meeting the Needs of LGBTQ Youth: A “Relational Assets” Approach. J. LGBT Youth 2009, 6, 174–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Plaza, C.; Quinn, S.C.C.; Rounds, K.A. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Students: Perceived Social Support in the High School Environment. High Sch. J. 2002, 85, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R.M.; Sanchez, J.; Lopez, B. LGBTQ+ Latinx young adults’ health autonomy in resisting cultural stigma. Cult. Health Sex. 2018, 21, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paceley, M.S.; Sattler, P.; Goffnett, J.; Jen, S. “It feels like home”: Transgender youth in the Midwest and conceptualizations of community climate. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 1863–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, K. Social Support and Mental Health in LGBTQ Adolescents: A review of the literature. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 39, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.A. Transgender Youth of Color and Resilience: Negotiating Oppression and Finding Support. Sex Roles 2012, 68, 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.A.; Meng, S.E.; Hansen, A.W. “I Am My Own Gender”: Resilience Strategies of Trans Youth. J. Couns. Dev. 2014, 92, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, N.E.; Kane, S.B.; Wisneski, H. Gay—Straight Alliances and School Experiences of Sexual Minority Youth. Youth Soc. 2009, 41, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.T.; Pollitt, A.; Li, G.; Grossman, A.H. Chosen Name Use Is Linked to Reduced Depressive Symptoms, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicidal Behavior Among Transgender Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.A.; Meng, S.; Hansen, A. “It’s Already Hard Enough Being a Student”: Developing Affirming College Environments for Trans Youth. J. LGBT Youth 2013, 10, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. The Impact of Belonging to a High School Gay/Straight Alliance. High Sch. J. 2002, 85, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, M.; Dalton, S.; Kolbert, J.; Crothers, L. Informal mentoring for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 109, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, M.E.; Gower, A.L.; Watson, R.J.; Porta, C.M.; Saewyc, E.M. LGBTQ Youth-Serving Organizations: What Do They Offer, and Do They Protect Against Emotional Distress? Ann. LGBTQ Public Popul. Health 2020, 1, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scroggs, B.; Miller, J.M.; Stanfield, M.H. Identity Development and Integration of Religious Identities in Gender and Sexual Minority Emerging Adults. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2018, 57, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolowic, J.M.; Sullivan, R.; Valdez, C.A.B.; Porta, C.M.; Eisenberg, M.E. Come Along With Me: Linking LGBTQ Youth to Supportive Resources. Int. J. Child Youth Fam. Stud. 2018, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiFulvio, G.T. Sexual minority youth, social connection and resilience: From personal struggle to collective identity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesmith, A.A.; Burton, D.L.; Cosgrove, T.J. Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Youth and Young Adults. J. Homosex. 1999, 37, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios, D.; Eaton, A. Perceived social support in the lives of gay, bisexual and queer Hispanic college men. Cult. Health Sex. 2016, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.W.; Brodsky, A.; Bruce, D. What’s Good About Being Gay? Perspectives from Youth. J. LGBT Youth 2012, 9, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Smith, E.; Ward, R.; Dixon, J.; Hillier, L.; Mitchell, A. School experiences of transgender and gender diverse students in Australia. Sex Educ. 2015, 16, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffnett, J.; Paceley, M.S. Challenges, pride, and connection: A qualitative exploration of advice transgender youth have for other transgender youth. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2020, 32, 328–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeman, L.; Aranda, K.; Sherriff, N.; Cocking, C. Promoting resilience and emotional well-being of transgender young people: Research at the intersections of gender and sexuality. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 20, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty-Caplan, D.M. Schools, Sex Education, and Support for Sexual Minorities: Exploring Historic Marginalization and Future Potential. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2013, 8, 246–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkie, E.; Adkins, V.; Masters, E.; Bajpai, A.; Shumer, D. Transgender Adolescents’ Uses of Social Media for Social Support. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 66, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, S.-Y.; Fenaughty, J.; Lucassen, M.F.; Fleming, T. Navigating double marginalisation: Migrant Chinese sexual and gender minority young people’s views on mental health challenges and supports. Cult. Health Sex. 2018, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, S.L.; McInroy, L.; McCready, L.; Alaggia, R.; Craig, S.L.; McInroy, L.; McCready, L.; Alaggia, R. Media: A Catalyst for Resilience in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth. J. LGBT Youth 2015, 12, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattis, M.N.; Woodford, M.R.; Han, Y. Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms Among Sexual Minority Youth: Is Gay-Affirming Religious Affiliation a Protective Factor? Arch. Sex. Behav. 2014, 43, 1589–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagaman, M.A.; Watts, K.; Lamneck, V.; D’Souza, S.A.; McInroy, L.B.; Eaton, A.D.; Craig, S. Managing stressors online and offline: LGBTQ+ Youth in the Southern United States. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 110, 104799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInroy, L.B. Building connections and slaying basilisks: Fostering support, resilience, and positive adjustment for sexual and gender minority youth in online fandom communities. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2019, 23, 1874–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceglarek, P.J.; Ward, L.M. A tool for help or harm? How associations between social networking use, social support, and mental health differ for sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paceley, M.S.; Goffnett, J.; Sanders, L.; Gadd-Nelson, J. “Sometimes You Get Married on Facebook”: The Use of Social Media among Nonmetropolitan Sexual and Gender Minority Youth. J. Homosex. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillier, L.; Mitchell, K.J.; Ybarra, M.L. The Internet As a Safety Net: Findings From a Series of Online Focus Groups With LGB and Non-LGB Young People in the United States. J. LGBT Youth 2012, 9, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, S.L.; Biello, K.; Perry, N.S.; Gamarel, K.E.; Mimiaga, M.J. A compensatory model of risk and resilience applied to adolescent sexual orientation disparities in nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide attempts. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, J.; Walls, N.E.; Wisneski, H. Religion and religiosity: Protective or harmful factors for sexual minority youth? Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2013, 16, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, E.; Donohue, G.; Timmins, F. An Exploration of the Relationship Between Spirituality, Religion and Mental Health Among Youth Who Identify as LGBT+: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 828–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meanley, S.; Pingel, E.S.; Bauermeister, J.A. Psychological Well-being Among Religious and Spiritual-identified Young Gay and Bisexual Men. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2015, 13, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walker, J.J.; Longmire-Avital, B. The impact of religious faith and internalized homonegativity on resiliency for black lesbian, gay, and bisexual emerging adults. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, N.C.; Flentje, A.; Cochran, B.N. Offsetting risks: High school gay-straight alliances and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2013, 1, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toomey, R.; Ryan, C.; Diaz, R.M.; Russell, S.T. High School Gay–Straight Alliances (GSAs) and Young Adult Well-Being: An Examination of GSA Presence, Participation, and Perceived Effectiveness. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2011, 15, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poteat, V.P.; Yoshikawa, H.; Calzo, J.; Gray, M.L.; DiGiovanni, C.D.; Lipkin, A.; Mundy-Shephard, A.; Perrotti, J.; Scheer, J.R.; Shaw, M.P.; et al. Contextualizing Gay-Straight Alliances: Student, Advisor, and Structural Factors Related to Positive Youth Development Among Members. Child Dev. 2014, 86, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Birkett, M.; Van Wagenen, A.; Meyer, I.H. Protective School Climates and Reduced Risk for Suicide Ideation in Sexual Minority Youths. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porta, C.M.; Singer, E.; Mehus, C.J.; Gower, A.; Saewyc, E.; Fredkove, W.; Eisenberg, M.E. LGBTQ Youth’s Views on Gay-Straight Alliances: Building Community, Providing Gateways, and Representing Safety and Support. J. Sch. Health 2017, 87, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poteat, V.P.; Calzo, J.P.; Yoshikawa, H. Promoting Youth Agency Through Dimensions of Gay–Straight Alliance Involvement and Conditions that Maximize Associations. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1438–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhardt, L.S.; Stevens, P.; Xie, H.; Wesp, L.M.; John, S.A.; Apchemengich, I.; Kioko, D.; Chavez-Korell, S.; Cochran, K.M.; Watjen, J.M.; et al. Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Youths’ Public Facilities Use and Psychological Well-Being: A Mixed-Method Study. Transgender Health 2017, 2, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernick, L.J.; Kulick, A.; Chin, M. Gender Identity Disparities in Bathroom Safety and Wellbeing among High School Students. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, C.M.; Gower, A.L.; Mehus, C.J.; Yu, X.; Saewyc, E.M.; Eisenberg, M.E. “Kicked out”: LGBTQ youths’ bathroom experiences and preferences. J. Adolesc. 2017, 56, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. Education policies: Potential impacts and implications in Australia and beyond. J. LGBT Youth 2016, 13, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M.; Hillier, L. Sexuality education school policy for Australian GLBTIQ students. Sex Educ. 2012, 12, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA). LGBTI+ National Youth Strategy; DCYA, The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/a6f110-lgbti-national-youth-strategy-2018-2020/?referrer=/documents/publications/odtc_full_eng.pdf/ (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Dennehy, R.; Meaney, S.; Cronin, M.; Arensman, E. The psychosocial impacts of cybervictimisation and barriers to seeking social support: Young people’s perspectives. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 111, 104872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frommer, M.; Howell, J.; Santow, E.; Cochrane, S.; Alston, B. Ensuring Health and Bodily Integrity: Towards a Human Rights Approach for People Born with Variations in Sex Characteristics Report 2021. Available online: https://humanrights.gov.au/intersex-report-2021 (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Ceatha, N. Opinion: It’s Pride 2021, Let’s Consider Giving Greater Support to LGBTI+ Youth in School. Available online: https://www.thejournal.ie/prev/5471030/dvIge7VkxiVY/ (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Költő, A.; Young, H.; Burke, L.; Moreau, N.; Cosma, A.; Magnusson, J.; Windlin, B.; Reis, M.; Saewyc, E.; Godeau, E.; et al. Love and Dating Patterns for Same- and Both-Gender Attracted Adolescents Across Europe. J. Res. Adolesc. 2018, 28, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.G. Counterproductive Effects of Parental Consent in Research Involving LGBTTIQ Youth: International Research Ethics and a Study of a Transgender and Two-Spirit Community in Canada. J. LGBT Youth 2008, 5, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, B.; Fitzgerald, A. My World Survey 1: The National Study of Youth Mental Health in Ireland; Jigsaw and UCD School of Psychology: Dublin, Ireland, 2012; Available online: https://jigsaw.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/MWS1_Full_Report_PDF.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Dooley, B.; O’Connor, C.; Fitzgerald, A.; O’Reilly, A. My World Survey 2: The National Study of Youth Mental Health in Ireland; Jigsaw and UCD School of Psychology: Dublin, Ireland, 2019; Available online: http://www.myworldsurvey.ie/full-report (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Ryan, C. Engaging Families to Support Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: The Family Acceptance Project. Prev. Res. 2010, 17, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, R.; Greenhalgh, T.; Harvey, G.; Walshe, K. Realist review—A new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matijczak, A.; McDonald, S.E.; Tomlinson, C.A.; Murphy, J.L.; O’Connor, K. The Moderating Effect of Comfort from Companion Animals and Social Support on the Relationship between Microaggressions and Mental Health in LGBTQ+ Emerging Adults. Behav. Sci. 2020, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, S.E.; Matijczak, A.; Nicotera, N.; Applebaum, J.W.; Kremer, L.; Natoli, G.; O’Ryan, R.; Booth, L.J.; Murphy, J.L.; Tomlinson, C.A.; et al. “He was like, my ride or die”: Sexual and Gender Minority Emerging Adults’ Perspectives on Living with Pets during the Transition to Adulthood. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceatha, N.; Mayock, P.; Campbell, J.; Noone, C.; Browne, K. The Power of Recognition: A Qualitative Study of Social Connectedness and Wellbeing through LGBT Sporting, Creative and Social Groups in Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceatha, N. Mastering wellness: LGBT people’s understanding of wellbeing through interest sharing. J. Res. Nurs. 2016, 21, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formby, E. Exploring LGBT Spaces and Communities: Contrasting Identities, Belongings and Wellbeing; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, C.; Kasperavicius, D.; Duncan, D.; Etherington, C.; Giangregorio, L.; Presseau, J.; Sibley, K.M.; Straus, S. ‘Doing’ or ‘using’ intersectionality? Opportunities and challenges in incorporating intersectionality into knowledge translation theory and practice. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G.M.; Bohan, J.S. Institutional Allyship for LGBT Equality: Underlying Processes and Potentials for Change. J. Soc. Issues 2016, 72, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, K.J. The Role of Community Belongingness in the Mental Health and Well-Being of Black LGBTQ Adults. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7815&context=etd (accessed on 19 September 2021).

- Kerekere, E. Part of the Whānau: The Emergence of Takatāpui Identity—He Whāriki Takatāpui. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10063/6369 (accessed on 19 September 2021).

- Sheppard, M.; Mayo, J.B. The Social Construction of Gender and Sexuality: Learning from Two Spirit Traditions. Soc. Stud. 2013, 104, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. School Design Guide (SDG) SDG 02-06 Sanitary Facilities; Government Publications: Dublin, Ireland, 2021. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/131218/d52c421e-99b7-47e2-ac15-2e5657af368d.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2021).

- Formby, E. Sex and relationships education, sexual health, and lesbian, gay and bisexual sexual cultures: Views from young people. Sex Educ. 2011, 11, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. LGBTI Inclusive Education Working Group: Report to the Scottish Ministers; Government Publications: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/lgbti-inclusive-education-working-group-report/documents/ (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Moffat, A. No Outsiders: Everyone Different, Everyone Welcome: Preparing Children for Life in Modern Britain; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.routledge.com/No-Outsiders-Everyone-Different-Everyone-Welcome-Preparing-Children-for/Moffat/p/book/9780367894986 (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Moffat, A.; Field, L. No Outsiders in Our School: Neglected Characteristics and the Argument against Childhood Ignorance. Educ. Child. Psychol 2020, 37, 101–117. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1245926 (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Moffat, A. No Outsiders in Our School: Teaching the Equality Act in Primary Schools, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceatha, N.; Kelly, A.; Killeen, T. Visible, Valued and Included: Prioritising Youth Participation in Policy-Making for the Irish LGBTI+ National Youth Strategy. In Child and Youth Participation: Policy, Practice and Research Advances in Ireland; Kennan, D., Horgan, D., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Child-and-Youth-Participation-in-Policy-Practice-and-Research/Horgan-Kennan/p/book/9780367568290 (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Vicars, M.; Van Toledo, S. Walking the Talk: LGBTQ Allies in Australian Secondary Schools. Front. Sociol. 2021, 6, 611001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PCC | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| P—Population |

|

|

| C—Concept |

|

|

| C—Context |

|

|

| Author/Year/Location Title | Methodology/Analysis | Demographic Details | Protective Factors | Wellbeing Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parra et al., 2018 Canada The Buffering Effect of Peer Support on the Links Between Family Rejection and Psychosocial Adjustment in LGB Emerging Adults. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 62 youth)

| Peer:

|

|

| Whitton et al., 2018 USA Romantic Involvement: A Protective Factor for Psychological Health in Racially-Diverse Young Sexual Minorities. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 248 youth)

| Peer:

|

|

| Veale et al., 2017 Canada Enacted Stigma, Mental Health, and Protective Factors Among Transgender Youth in Canada | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 923 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| McConnell et al., 2016 USA Families Matter: Social Support and Mental Health Trajectories Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 232 youth)

| Parent/peer

|

|

| Mohr and Sarno, 2016 USA The Ups and Downs of Being Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual: A Daily Experience Perspective on Minority Stress and Support Processes. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 61 students)

| Peer

|

|

| Taliaferro et al., 2016 USA Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Suicidality Among Sexual Minority Youth: Risk Factors and Protective Connectedness Factors. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 2223 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Watson et al., 2016 USA Sources of Social Support and Mental Health Among LGB Youth. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 835 youth)

| Peer:

|

|

| Wilson, 2016 USA The Impact of Discrimination on the Mental Health of Trans * Female Youth and the Protective Effect of Parental Support. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 216 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Kanhere et al., 2015 USA Psychosexual Development and Quality of Life Outcomes in Females with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 27 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Watson et al., 2015 USA How Does Sexual Identity Disclosure Impact School Experiences? | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 375 youth)

| Parent/Peer:

|

|

| Simons et al., 2013 USA Parental Support and Mental Health Among Transgender Adolescents | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 66 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Mustanski et al., 2011 USA Mental Health of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youths: A Developmental Resiliency Perspective | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 425 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Bauermeister et al., 2010 USA Relationship Trajectories and Psychological Well-Being Among Sexual Minority Youth | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 350 youth)

| Peer:

|

|

| Doty et al., 2010 USA Sexuality Related Social Support Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 98 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Ryan et al., 2010 USA Family Acceptance in Adolescence and the Health of LGBT Young Adults | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 245 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Sheets and Mohr, 2009 USA Perceived Social Support from Friends and Family and Psychosocial Functioning in Bisexual Young Adult College Students | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 210 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Detrie and Lease, 2008 USA The Relation of Social Support, Connectedness, and Collective Self-Esteem to the PsychologicalWell-Being of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 218 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Darby-Mullins and Murdock, 2007 USA The Influence of Family Environment Factors on Self-Acceptance and Emotional Adjustment Among Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Adolescents | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 102 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Floyd et al., 1999 USA Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Youths: Separation-Individuation, Parental Attitudes, Identity Consolidation, and Well-Being | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 72 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Savin-Williams, 1989 USA Parental Influences on the Self-Esteem of Gay and Lesbian Youth: A Reflected Appraisals Model | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 317 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Savin-Williams, 1989 USA Coming Out to Parents and Self-esteem Among Gay and Lesbian Youths | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 317 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Author/Year/Location Title | Methodology/Analysis | Demographic Details | Protective Factors | Wellbeing Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johnson et al., 2020 USA Trans Adolescents’ Perceptions and Experiences of Their Parents’ Supportive and Rejecting Behaviors. | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 24 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| McDermott et al., 2019 England Family trouble: Heteronormativity, Emotion Work and Queer Youth Mental Health. | Qualitative (two phase study)

| Participants (n = 13 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Bry et al. 2017 USA Management of a Concealable Stigmatized Identity: A Qualitative Study of Concealment, Disclosure, and Role Flexing Among Young, Resilient Sexual and Gender Minority Individuals | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 10 youth)

| Parent/peer:

|

|

| Mehus et al., 2017 USA/Canada Living as an LGBTQ Adolescent and a Parent’s Child | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 66 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Weinhardt et al., 2017 USA The Role of Family, Friend, and Significant Other Support in Well-Being Among Transgender and Non-Binary Youth. | Mixed-methods research

|

Participants (n = 157) youth survey; focus groups (n = 8)

| Parent:

|

|

| Mulcahy et al. 2016 USA Informal Mentoring for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Students. | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 10) youth

| Provider:

|

|

| Bouris et al., 2010 USA A Systematic Review of Parental Influences on the Health and Well-Being of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth: Time for a New Public Health Research and Practice Agenda | Systematic review

| Included studies (n = 31 records)

| Parent:

|

|

| Diamond and Lucas, 2004 USA Sexual-Minority and Heterosexual Youths’ Peer Relationships: Experiences, Expectations, and Implications for Well-Being | Mixed-methods research

| Participants (n = 60)

| Peer:

|

|

| Galupo and St John, 2001 USA Benefits of Cross-Sexual Orientation Friendships Among Adolescent Females | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 20 youth

| Peer:

|

|

| Author/Year/Location Title | Methodology/Analysis | Demographic Details | Community Protective Factors | Wellbeing Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eisenberg et al., 2020 USA LGBTQ Youth-Serving Organizations: What Do They Offer and Do They Protect Against Emotional Distress? | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 2454 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities

|

|

| McCann et al., 2020 Global An Exploration of the Relationship Between Spirituality, Religion and Mental Health Among Youth Who Identify as LGBT+: A Systematic Literature Review | Systematic review

| Included studies (n = 9 records)

| Faith communities

|

|

| Wagaman et al., 2020 USA Managing Stressors Online and Offline: LGBTQ+ Youth in the Southern United States | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 662 youth)

| Online communities

|

|

| McInroy, 2019 USA/Canada Building Connections and Slaying Basilisks: Fostering Support, Resilience, and Positive Adjustment for Sexual and Gender Minority Youth in Online Fandom Communities | Mixed-methods research

| Participants (n = 3665 youth)

| Online communities

|

|

| Rubino et al., 2018 Australia Internalized Homophobia and Depression in Lesbian Women: The Protective Role of Pride | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 225 adults)

| LGBTI+ communities (lesbian)

|

|

| Scroggs et al., 2018 USA Identity Development and Integration of Religious Identities in Gender and Sexual Minority Emerging Adults | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 961 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities

|

|

| Ceglarek and Ward, 2016 USA A Tool for Help or Harm? How Associations Between Social Networking Use, Social Support, and Mental Health Differ for Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Youth | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 146 youth)

| Online communities

|

|

| Meanley et al., 2016 USA Psychological Well-being Among Religious and Spiritual-identified Young Gay and Bisexual Men | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 397 people)

| Faith communities

|

|

| Zimmerman et al., 2015 USA Resilience in Community: A Social Ecological Development Model for Young Adult Sexual Minority Women | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 843 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities (lesbian)

|

|

| Gattis et al., 2014 USA Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms Among Sexual Minority Youth: Is Gay-Affirming Religious Affiliation a Protective Factor? | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 393 people)

| Faith communities

|

|

| Longo et al., 2013 USA Religion and Religiosity: Protective or Harmful Factors for Sexual Minority Youth? | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 250 youth)

| Faith communities

|

|

| Walker and Longmire-Avital, 2013 USA The Impact of Religious Faith and Internalized Homonegativity onResiliency for Black Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Emerging Adults | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 175 youth)

| Faith communities

|

|

| Author/Year/Location Title | Methodology/Analysis | Demographic Details | Community Protective Factors | Wellbeing Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goffnett et al., 2020 USA Challenges, Pride, and Connection: A Qualitative Exploration of Advice Transgender Youth Have for Other Transgender Youth | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 19 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities (trans)

|

|

| Paceley et al., 2020 USA “Sometimes you get married on Facebook”: The Use of Social Media among Nonmetropolitan Sexual and Gender Minority Youth | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 34 youth)

| Online communities

|

|

| Selkie et al., 2020 USA Transgender Adolescents’ Uses of Social Media for Social Support | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 25 youth)

| Online communities

|

|

| Chiang et al., 2019 New Zealand Navigating Double Marginalisation: Migrant Chinese Sexual and Gender Minority Young People’s Views on Mental Health Challenges and Supports | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 11 youth)

| Cultural communities

|

|

| Schmitz et al., 2019 USA LGBTQ+ Latinx Young Adults’ Health Autonomy in Resisting Cultural Stigma | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 41 youth)

| Cultural communities

|

|

| Morris, 2018 UK “Gay capital” in GayStudent FriendshipNetworks: AnIntersectional Analysis ofClass, Masculinity, andDecreased Homophobia | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 40 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities (gay)

|

|

| Wolowic et al., 2018 USA/Canada Come Along With Me: Linking LGBTQ Youth to Supportive Resources | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 66 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities

|

|

| Zeeman et al., 2017 UK Promoting Resilience and Emotional Well-Being of Transgender Young People: Research at the Intersections of Gender and Sexuality | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 5 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities (trans)

|

|

| Rios and Eaton, 2016 USA Perceived Social Support in the Lives of Gay, Bisexual and Queer Hispanic College Men | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 51 students)

| LGBTI+ communities (gay)

|

|

| Craig et al., 2015 Canada Media: A Catalyst for Resilience in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 19 youth)

| Online communities

|

|

| Singh, 2013 USA Transgender Youth of Color and Resilience: NegotiatingOppression and Finding Support | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 13 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities (trans)

|

|

| Harper et al., 2012 USA What’s Good About Being Gay? Perspectives from Youth | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 63 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities (gay)

|

|

| Hillier et al., 2012 USA The Internet As a Safety Net: Findings From a Series of Online Focus Groups With LGB and Non-LGB Young People in the United States | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 33 youth)

| Online communities

|

|

| Singh et al., 2012 USA “I Am My Own Gender”: Resilience Strategies of Trans Youth | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 19 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities (trans)

|

|

| DiFulvio, 2011 USA Sexual Minority Youth, Social Connection and Resilience: From Personal Struggle toCollective Identity | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 22 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities

|

|

| Munoz-Plaza et al., 2002 USA Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Students: Perceived Social Support in the High School Environment | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 12 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities

|

|

| Nesmith et al., 1999 USA Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Youth and Young Adults | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 17 youth)

| LGBTI+ communities

|

|

| Author/Year/Location Title | Methodology/Analysis | Demographic Details | Protective Factors | Wellbeing Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poteat et al., 2019 USA Greater Engagement in Gender-Sexuality Alliances (GSAs) and GSA Characteristics Predict Youth Empowerment and Reduced Mental Health Concerns. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 580 youth)

| Gender Sexuality Alliances

|

|

| Weinhardt et al., 2019, USA Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Youths’ Public Facilities Use and Psychological Well-Being: A Mixed-Method Study | Mixed-methods research

| Participants (n = 127 youth)

| Inclusive policies

|

|

| McDonald, 2018 Global Social Support and Mental Health in LGBTQ Adolescents: A Review of the Literature. | Narrative review

| Included studies

| Gay-Straight Alliances:

|

|

| Russell et al., 2018 USA Chosen Name Use Is Linked to Reduced Depressive Symptoms, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicidal Behavior Among Transgender Youth. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 129 youth)

| Inclusive policies:

|

|

| Porta, Gower et al., 2017 Canada/USA “Kicked out”: LGBTQ youths’ Bathroom Experiences and Preferences. | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 25 youth)

| Inclusive policies

|

|

| Porta, Singer et al., 2017 Canada/US LGBTQ Youth’s Views on Gay-Straight Alliances: Building Community, Providing Gateways, and Representing Safety and Support. | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 58 youth)

| Gay–Straight Alliances

|

|

| Wernick et al., 2017 USA Gender Identity Disparities in Bathroom Safety and Wellbeing among High School Students | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 86)

| Inclusive policies (bathrooms)

|

|

| Jones, 2016 Australia Education Policies: Potential Impacts and Implications in Australia and Beyond. | Mixed-methods research

| Participants (n = 3134 youth)

| Inclusive policies

|

|

| Poteat et al., 2016 USA Promoting Youth Agency Through Dimensions of Gay-Straight Alliance Involvement and Conditions that Maximize Associations. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 205 youth)

| Gay–Straight Alliances

|

|

| Poteat et al., 2015 USA Contextualizing Gay-Straight Alliances: Student, Advisor, and Structural Factors Related to Positive Youth Development Among Members. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 85 youth)

| Gay–Straight Alliances

|

|

| Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014 USA Protective School Climates and Reduced Risk for Suicide Ideation in Sexual Minority Youths. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 4314 youth)

| Gay–Straight Alliances

|

|

| Heck et al., 2013 USA Offsetting Risks: High School Gay Straight Alliances and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 145 youth)

| Gay–Straight Alliances

|

|

| McCarty-Caplan, 2013 USA Schools, Sex Education, and Support for Sexual Minorities: Exploring Historic Marginalization and Future Potential | Narrative review

| Studies

| Gay–Straight Alliances:

|

|

| Jones and Hillier, 2012 Australia Sexuality Education School Policy for Australian GLBTIQ Students | Mixed-methods research

| Participants (n = 3134 youth)

| Inclusive policies:

|

|

| Toomey and Russell, 2011 USA Gay-Straight Alliances, Social Justice Involvement, and School Victimization of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Youth: Implications for School Well-Being and Plans to Vote. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 230 youth)

| Gay–Straight Alliances

|

|

| Toomey et al., 2011 USA High School Gay–Straight Alliances (GSAs) and Young Adult Well-Being: An Examination of GSA Presence, Participation, and Perceived Effectiveness. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 245 youth)

| Gay–Straight Alliances

|

|

| Walls et al., 2010 USA Gay-Straight Alliances and School Experiences of Sexual Minority Youth. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 135 youth)

| Gay–Straight Alliances:

|

|

| Lee, 2002, USA The Impact of Belonging to a High School Gay/Straight Alliance | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 7 youth)

| Gay–Straight Alliances:

| Increased school attendance, expected college attendance

|

| Author/Year/Location Title | Methodology/Analysis | Demographic Details | Intersecting Protective Factors | Wellbeing Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paceley et al. 2020 US “It feels like home”: Transgender Youth in the Midwest and Conceptualizations of Community Climate | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 19)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Wilson and Cariola, 2020 Global LGBTQI+ Youth and Mental Health: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research. | Systematic review

| Included studies (n = 34 records)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Poštuvan et al., 2019 Global Suicidal Behaviour Among Sexual-Minority Youth: A Review of the Role of Acceptance and Support | Narrative review

| Included studies

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Taliaferro et al., 2019 USA Risk and Protective Factors for Self-Harm in a Population-Based Sample of Transgender Youth. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 1635 youth)

| Parent/Provider:

|

|

| Eisenberg et al., 2018 US/Canada Helping Young People Stay Afloat: A Qualitative Study of Community Resources and Supports for LGBTQ Adolescents in the U.S. and Canada. | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 66 youth)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Gower et al., 2018 USA Supporting Transgender and Gender Diverse Youth: Protection Against Emotional Distress and Substance Use. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 2168 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Hall, 2018 US Psychosocial Risk and Protective Factors for Depression Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, andQueer Youth: A Systematic Review | Systematic review

| Included studies (n = 35 records)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Johns et al., 2018 US Protective Factors Among Transgender and Gender Variant Youth: A Systematic Review by Socioecological Level. | Systematic review

| Included studies (n = 21 records)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Sansfaçon et al., 2018 Canada Digging Beneath the Surface: Results from Stage One of a Qualitative Analysis of Factors Influencing the Well-Being of Trans Youth in Quebec | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 24 youth)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Jones, Smith et al., 2016 Australia School Experiences of Transgender and Gender Diverse Students in Australia. | Mixed-Methods Research

| Participants (n = 189 youth)

| Interpersonal

|

|

| Snapp et al., 2015 USA Social Support Networks for LGBT Young Adults: Low Cost Strategies for Positive Adjustment | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 245 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Higa, 2014 US Negative and Positive Factors Associated with the Well-Being of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Questioning (LGBTQ) Youth. | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 68 youth)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Reisner et al., 2014 USA A Compensatory Model of Risk and Resilience Applied to Adolescent Sexual Orientation Disparities in Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Suicide Attempts. | Quantitative

| Participants (n = 225 youth)

| Parent:

|

|

| Singh et al., 2013 US “It’s already hard enough being a student”: Developing Affirming College Environments for Trans Youth. | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 17)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Torres et al., 2012 US Examining Natural Mentoring Relationships (NMRs) Among Self-Identified Gay, Bisexual, and Questioning (GBQ) Male Youth. | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 39 youth)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Cohn and Hastings, 2010 US Resilience Among Rural Lesbian Youth | Narrative review

| Included studies (19 records)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Davis et al., 2009 US Supporting the Emotional and Psychological Well Being of Sexual Minority Youth: Youth Ideas for Action. | Mixed-Methods Research

| Participants (n = 33 youth)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Sadowski et al., 2009 US Meeting the Needs of LGBTQ Youth: A “Relational Assets” Approach. | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 30 youth)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

| Fenaughty and Harré, 2003 NZ Life on the Seesaw: A Qualitative Study of Suicide Resiliency Factors for Young Gay Men. | Qualitative

| Participants (n = 8 youth)

| Interpersonal:

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ceatha, N.; Koay, A.C.C.; Buggy, C.; James, O.; Tully, L.; Bustillo, M.; Crowley, D. Protective Factors for LGBTI+ Youth Wellbeing: A Scoping Review Underpinned by Recognition Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111682

Ceatha N, Koay ACC, Buggy C, James O, Tully L, Bustillo M, Crowley D. Protective Factors for LGBTI+ Youth Wellbeing: A Scoping Review Underpinned by Recognition Theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111682

Chicago/Turabian StyleCeatha, Nerilee, Aaron C. C. Koay, Conor Buggy, Oscar James, Louise Tully, Marta Bustillo, and Des Crowley. 2021. "Protective Factors for LGBTI+ Youth Wellbeing: A Scoping Review Underpinned by Recognition Theory" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111682

APA StyleCeatha, N., Koay, A. C. C., Buggy, C., James, O., Tully, L., Bustillo, M., & Crowley, D. (2021). Protective Factors for LGBTI+ Youth Wellbeing: A Scoping Review Underpinned by Recognition Theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111682