The Wildman Programme—Rehabilitation and Reconnection with Nature for Men with Mental or Physical Health Problems—A Matched-Control Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Nature as Treatment

1.2. The Wildman Programme

1.3. Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Venue

2.4. Intervention

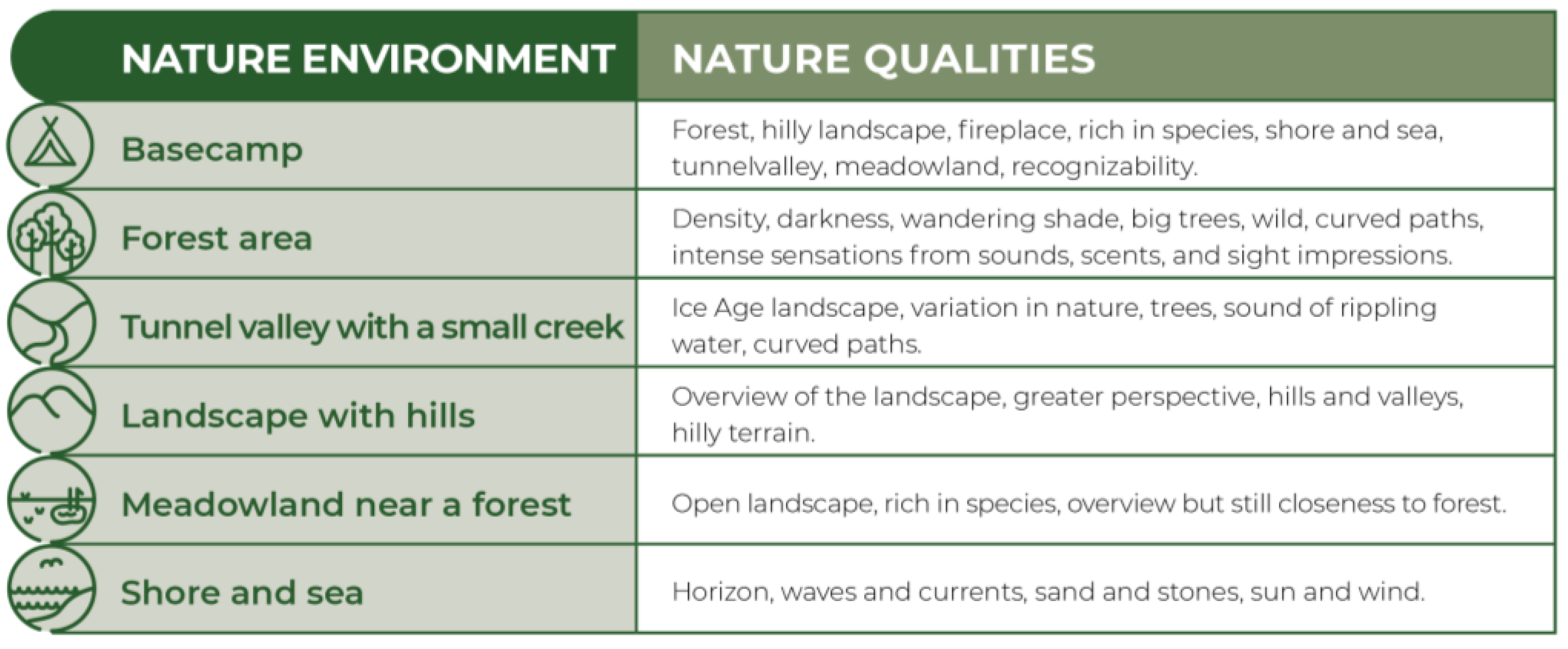

2.4.1. Nature

2.4.2. Body

2.4.3. Mind

2.4.4. Community Spirit

2.5. Outcomes

2.5.1. Primary Outcome

- Physical health: 7 items.

- Psychological health: 6 items.

- Social relationships: 3 items.

- Environment: 8 items.

2.5.2. Secondary Outcomes

- The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [68]: PSS examines how different situations affect feelings and perceived stress in daily living within the last month. The scale consists of 10 items in a five-point Likert Scale. The scores range from 0 to 4 for the questions 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 10. The scores of the questions 4, 5, 7, and 8 are reversed. The scores for each item are added to get a total. The individual scores on the PSS can range from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicate higher perceived stress. Scores ranging from 0 to 13 are considered as a low level of perceived stress, scores ranging from 14 to 26 are considered as a moderate level of perceived stress, and scores ranging from 27 to 40 are considered as a high level of perceived stress [68].

- The Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS) [69]: PRS measures, in 26 items, four different categories of self-experienced restitution related to spontaneous attention: fascination, being away, extent, and compatibility. The scale is used for measuring meditation practice and attention training in natural environments [70].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

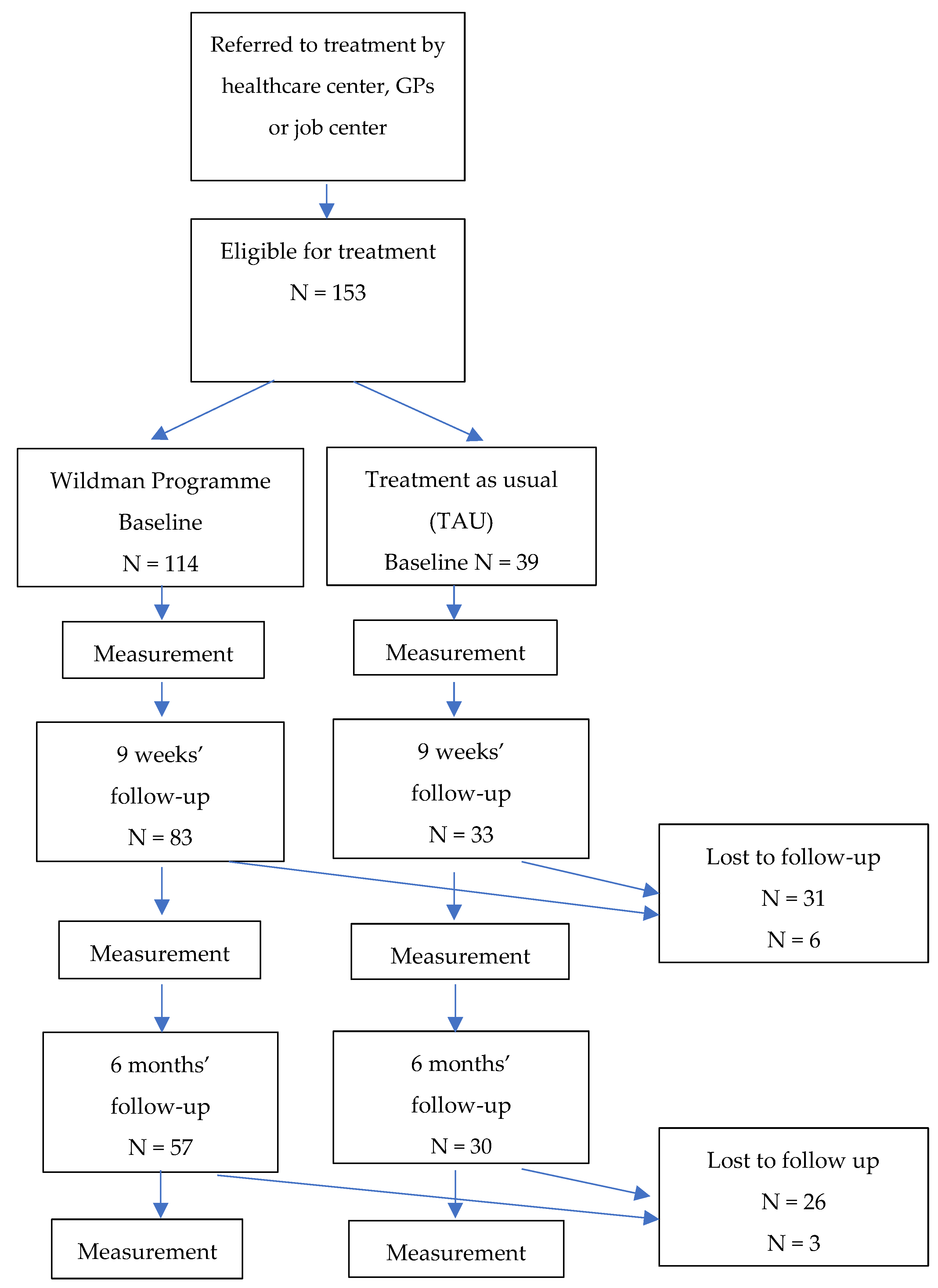

3.1. Flow of Participants

3.2. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

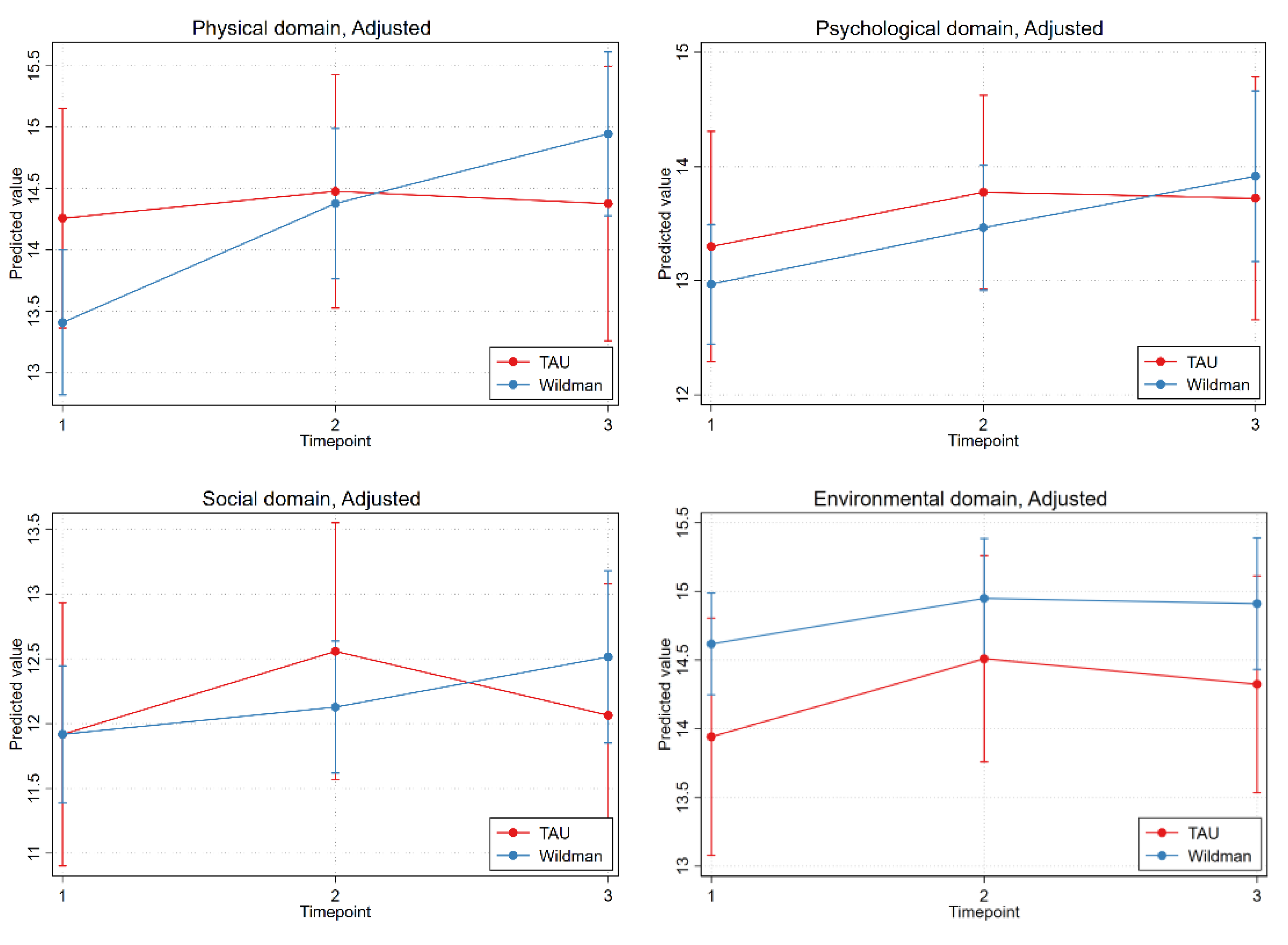

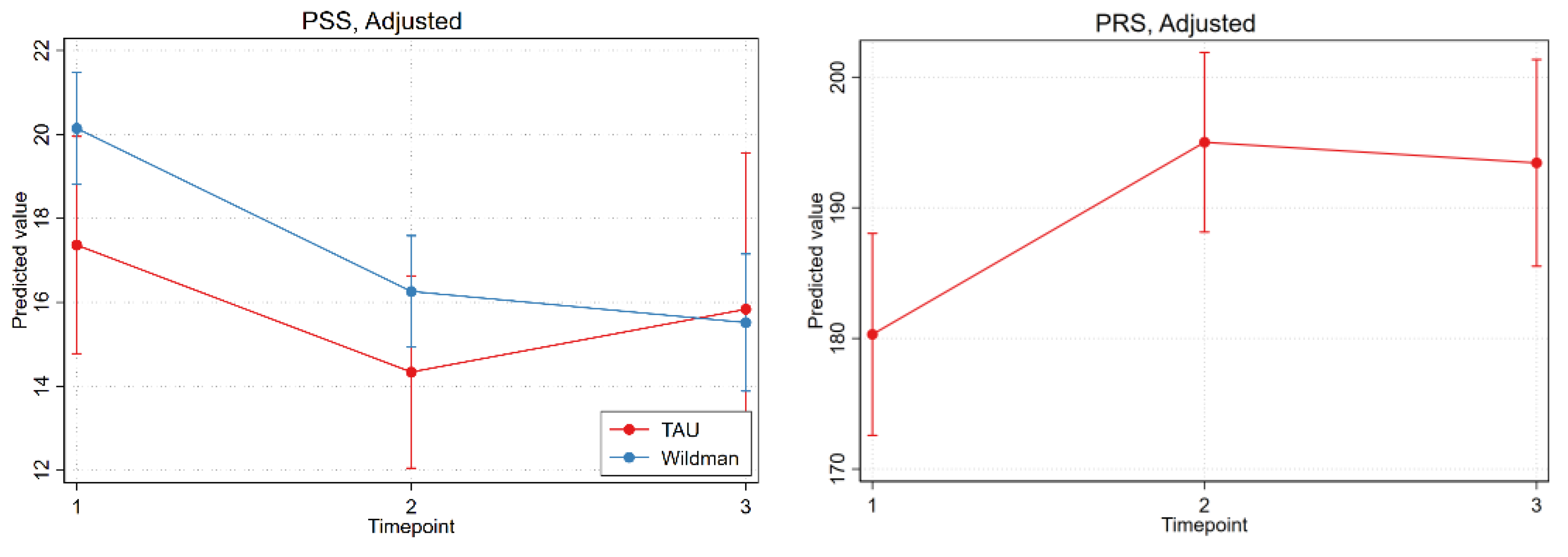

3.3. Results of the Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of the Wildman Programme

4.2. Appeal to Men

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (11th Revision). 2020. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Jensen, H.A.R.; Davidsen, M.; Ekholm, O.; Christensen, A.I. Danskernes Sundhed—Den Nationale Sundhedsprofil 2017. The Danes’ Health—The National Health Profile. Sundhedsstyrelsen. 2018. Available online: https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2018/~/media/73EADC242CDB46BD8ABF9DE895A6132C.ashx (accessed on 6 March 2018).

- Slavich, G.M. Life stress and health: A review of conceptual issues and recent findings. Teach. Psychol. 2016, 43, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. The Health and Well-Being of Men in the WHO European Region: Better Health through a Gender Approach; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Watkins, D.C.; Griffith, D.M. Equity, gender and health: New directions for global men’s health promotion. Health Prom. J. Aust. 2020, 31, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragonese, C.; Shand, T.; Barker, G. Masculine Norms and Men’s Health: Making the Connections; Promundo-US: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, S.A. Men as patients: Understanding and communicating with men. Trends Urol Men’s Health 2015, 6, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragonese, C.; Barker, G. Understanding masculinities to improve men’s health. Lancet 2019, 394, 198–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, A.I.; Mudu, P.; Braubach, M.; Martuzzi, M. Urban Green Spaces and Health: A Review of Evidence; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gascon Merlos, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Martínez, D.; Dadvand, P.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Plasència, A.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Residential green spaces and mortality: A systematic review. Environ. Int. 2016, 86, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, B.; Lee, K.J.; Zaslawski, C.; Yeung, A.; Rosenthal, D.; Larkey, L.; Back, M. Health and well-being benefits of spending time in forests: Systematic review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2017, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clatworthy, J.; Hinds, J.; Camic, P.M. Gardening as a mental health intervention: A review. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2013, 18, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Yamaura, Y. Gardening is beneficial for health: A meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 5, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, J.; Benz, A.; Holmgren, A.; Kinter, D.; McGarry, J.; Rufino, G. A systematic review of the effects of horticultural therapy on persons with mental health conditions. Occup. Ther. Ment. Health 2017, 33, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz, J. James and Attention: Reactive Spontaneity. In The Oxford Handbook of William James; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; CUP Archive: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S.; Berman, M.G. Directed attention as a common resource for executive functioning and self-regulation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment. Human Behavior and Environment (Advances in Theory and Research); Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; Volume 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, R.S. Visual landscapes and psychological well-being. Landsc. Res. 1979, 4, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høegmark, S.; Elmose Andersen, T.; Grahn, P.; Kaya Roessler, K. The Wildman Programme. A Nature-Based Rehabilitation Programme Enhancing Quality of Life for Men on Long-Term Sick Leave: Study Protocol for a Matched Controlled Study in Denmark. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P. The Economics of Biodiversity. The Dasgupta Review; HM Treasury: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bosch, M.; Bird, W. Oxford Textbook of Nature and Public Health: The Role of Nature in Improving the Health of a Population; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Will, K. Wilderness Recreation—An Analysis of Social Carrying Capacity, Regional Differences, and the Role of Gender. Master’s Thesis, Davis College of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Design, Innsbruck, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pálsdóttir, A.M.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Persson, D.; Thorpert, P.; Grahn, P. The qualities of natural environments that support the rehabilitation process of individuals with stress-related mental disorder in nature-based rehabilitation. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roessler, K.K.; Hoegmark, S.; Eichberg, H.; Robering, K. Naturen som med-behandler? Teoretiske og empiriske overvejelser om stemning og relationer i et terapeutisk rum. Psyke Logos 2018, 39, 162–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bratland-Sanda, S.; Andersson, E.; Best, J.; Høegmark, S.; Roessler, K.K. The use of physical activity, sport and outdoor life as tools of psychosocial intervention: The Nordic perspective. Sport Soc. 2017, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Ottosson, J.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K. The oxytocinergic system as a mediator of anti-stress and instorative effects induced by nature. The Calm and Connection theory. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.-W.; Chan, C.H.; Ho, R.T.; Chan, J.S.; Ng, S.M.; Chan, C.L. Managing stress and anxiety through qigong exercise in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Effect of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on human health: A review of the literature. Sante Publique 2019, S1, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.M. ICD-10-CM 2019 The Complete Official Codebook; American Medical Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, B.; Quitzau, M.-B. Byerne som arena for rehabilitering. In Rehabilitering Ude–Nye Ressourcer og Perspektiver i Rehabiliteringen; Videnscenter om Handicap, Universitet i Sørøst-Norge, Rehabiliteringsforum: Notodden, Norway, 2019; pp. 240–250. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, E.; Rohde, T.; Cserhalmi, N.; Lohne, B.; Sandell, K.; Lasse, S.; Hanssen, K.; Araluoma, M.; Koskinen, S.; Sarkkinen, S.; et al. Naturveiledning i Norden: En Bok om Opplevelser, Læring, Refleksjon og Deltakelse i Møtet Mellom Natur og Menneske; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wynn, T. Fire Good. Make Human Inspiration Happen; Smithsonian: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Aziz, M.; Ullah, Z.; Pieroni, A. Wild food plant gathering among Kalasha, Yidgha, Nuristani and Khowar speakers in Chitral, NW Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Sasaki, J.E.; Wang, H.; Xiao, Z.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of Baduanjin Qigong for health benefits: Randomized controlled trials. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 4548706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Clark, J.; Siskind, D.; Williams, G.M.; Byrne, G.; Yang, J.L.; Doi, S.A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of Qigong and Tai Chi for depressive symptoms. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Ottosson, Å. Trädgårdsterapi; Bonniers Existens: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J.; Barton, J. Nature-Based Interventions and Mind–Body Interventions: Saving Public Health Costs Whilst Increasing Life Satisfaction and Happiness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.; Hinds, J. Ecotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Summers, J.K.; Vivian, D.N. Ecotherapy—A forgotten ecosystem service: A review. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Tenngart Ivarsson, C.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Bengtsson, I.L. Using Affordances as a Health-Promoting Tool in a Therapeutic Garden; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2010; pp. 116–154. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, L. Review of Ecotherapy: Healing with Nature in Mind. Ecopsychology 2009, 1, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E. With nature in mind: The ecotherapy manual for mental health professionals. Br. J. Guid. Counsel. 2017, 45, 633–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamie, G.A. Signals, cues and the nature of mimicry. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 284, 20162080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellert, S.R. Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, D. The Biophilia Hypothesis. WLA 1995, 29, 371–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Keller, R. Regulation of circulating levels of the crustacean hyperglycemic hormone: Evidence for a dual feedback control system. J. Comp. Physiol. B 1993, 163, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. The ecological footprint. Vital Speeches 2001, 67, 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Brink, P.; Mutafoglu, K.; Schweitzer, J.P.; Kettunen, M.; Twigger-Ross, C.; Baker, J.; Kuipers, Y.; Emonts, M.; Hujala, T.; Ojala, A.; et al. The Health and Social Benefits of Nature and Biodiversity Protection. A Report for the European Commission (ENV. B. 3/ETU/2014/0039); Institute for European Environmental Policy: London, UK; Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, M.F.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Evans, K.L.; Goddard, M.A.; Lerman, S.B.; MacIvor, J.S.; Nilon, C.H.; Vargo, T. Biodiversity in the city: Key challenges for urban green space management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 15, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, C.D.; Brook, A.T.; Myers, O.E. Using Psychology to Save Biodiversity and Human Well-Being. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 702–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonntag-Öström, E. Forest for Rest: Recovery from Exhaustion Disorder; Umeå Universitet: Umeå, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Perciavalle, V.; Blandini, M.; Fecarotta, P.; Buscemi, A.; Di Corrado, D.; Bertolo, L.; Fichera, F.; Coco, M. The role of deep breathing on stress. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 38, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, K.; Douglas, J.; Serry, T. Sharing stories of lived experience: A qualitative analysis of the intersection of experiences between storytellers with acquired brain injury and storytelling facilitators. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 83, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even, C.; Bosser, A.; Ferreira, J.F.; Buche, C.; Stephan., F.; Cavazza, M.; Lisetti, C. Supporting social skills rehabilitation with virtual storytelling. In Proceedings of the 29th International Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference, FLAIRS 2016, Key Largo, FL, USA, 16–18 May 2016; pp. 329–334. [Google Scholar]

- la Cour, K.; Ledderer, L.; Hansen, H.P. Storytelling as part of cancer rehabilitation to support cancer patients and their relatives. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2016, 34, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowlett, J.A. The discovery of fire by humans: A long and convoluted process. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, R. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, by Yuval Harari. Emerg. Libr. Inf. Perspect. 2018, 1, 134–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Partridge, C. “I Feel Part of a Movement that is Bigger than Myself”; Exploring the Experiences of the Fire Spinning Community and Their Connections to Nature. Bachelor’s Thesis, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. Health, Stress and Coping. Jossey Bass. Psychol. Med. 1981, 11, 206. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/psychological-medicine/article/abs/health-stress-and-coping-by-a-antonovsky-pp-225-illustrated-950-josseybass-london-1979/CCA7D94740812E9227DD528A6E86750D (accessed on 18 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, T.W. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Social Sci. Med. 1998, 46, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. Perceived Stress Scale. Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994; Volume 10, pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Korpela, K.; Evans, G.W.; Gärling, T. A measure of restorative quality of environments. Scand. Hous. Plan. Res. 1997, 14, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, M.; Berto, R.; Brondino, M.; Hall, R.; Ortner, C. How to measure the restorative quality of environments: The PRS-11. Procedia-Social Behav. Sci. 2014, 159, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D. Effects of shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) and nature therapy on mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prevent. Med. 2010, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, A.J.; Passmore, H.A.; Buro, K. Meaning in nature: Meaning in life as a mediator of the relationship between nature connectedness and well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brymer, E.; Crabtree, J.; King, R. Exploring perceptions of how nature recreation benefits mental wellbeing: A qualitative enquiry. Ann. Leis. Res. 2021, 24, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjortbak, B.R.; Bangshaab, J.; Johansen, J.S.; Lund, H. Udfordringer Til Rehabilitering i Danmark. Udfordringer, 246. 2011. Available online: https://www.rehabiliteringsforum.dk/contentassets/2e9c82ccb58a4c6caa97552697257878/udfordringer_til_rehabilitering_wed_udgave.pdf#page=246 (accessed on 1 November 2011).

| Sample Characteristics | Control | Intervention | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 39 | 114 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 57.55 (10.70) (n = 38) | 54.60 (13.67) (n = 109) | 0.23 |

| Educational level (ISCED), n (%) | |||

| Lower secondary or less | 6 (15.8%) | 18 (16.7%) | 0.95 |

| Upper secondary | 13 (34.2%) | 39 (36.1%) | |

| Short cycle tertiery/bachelor | 13 (34.2%) | 38 (35.2%) | |

| Master’s or above | 6 (15.8%) | 13 (12.0%) | |

| Currently employed, n (%) | |||

| Unemployed | 3 (7.9%) | 20 (18.7%) | 0.13 |

| Employed | 13 (34.2%) | 21 (19.6%) | |

| In job training or education | 1 (2.6%) | 12 (11.2%) | |

| Retired | 12 (31.6%) | 28 (26.2%) | |

| Other | 9 (23.7%) | 26 (24.3%) | |

| Cohabiting status, n (%) | |||

| Alone | 8 (21.1%) | 28 (25.7%) | 0.57 |

| Cohabiting | 30 (78.9%) | 81 (74.3%) | |

| Children, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 32 (84.2%) | 91 (83.5%) | 0.92 |

| No | 6 (15.8%) | 18 (16.5%) | |

| Referred from, n (%) | |||

| General Practitioner (GP) | 12 (33.3%) | 8 (7.4%) | <0.001 |

| Job centre | 3 (8.3%) | 38 (35.2%) | |

| Other | 21 (58.3%) | 62 (57.4%) | |

| Physical illness(es), n (%) | |||

| Yes | 28 (75.7%) | 61 (57.0%) | 0.044 |

| No | 9 (24.3%) | 46 (43.0%) | |

| Psychological illness(es), n (%) | |||

| Yes | 11 (28.9%) | 56 (52.8%) | 0.011 |

| No | 27 (71.1%) | 50 (47.2%) | |

| In treatment 1, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 32 (88.9%) | 65 (63.1%) | 0.004 |

| No | 4 (11.1%) | 38 (36.9%) | |

| Contact with psychiatric hospital 2, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 1 (3%) | 20 (22%) | 0.012 |

| No | 32 (97%) | 70 (78%) | |

| Medication 3, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 30 (83.3%) | 74 (70.5%) | 0.13 |

| No | 6 (16.7%) | 31 (29.5%) |

| Intervention Group (Wildman Programme) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, Mean (SD) | 9-Week Follow-Up, Mean (SD) | Difference Baseline to 9-Week Follow-Up, Mean (SD) 3 | Cohen’s d Baseline to 9-Week Follow-Up 4 | p-Value 1 | 6-Month Follow-Up, Mean (SD) | Difference Baseline to 6-Month Follow-Up, Mean (SD) 3 | Cohen’s d Baseline to 6-Month Follow-Up 4 | p-Value 2 | |

| WHOQOL-BREF Physical domain | 13.41 (3.05) | 14.26 (2.76) | 0.84 (2.18) | 0.38 | 0.001 | 15.15 (2.73) | 1.32 (2.66) | 0.50 | 0.000 |

| WHOQOL-BREF Psychological domain | 12.67 (3.28) | 13.38 (3.02) | 0.46 (1.87) | 0.24 | 0.029 | 14.43 (3.15) | 1.10 (2.84) | 0.39 | 0.005 |

| WHOQOL-BREF Social domain | 11.74 (2.95) | 12.17 (2.53) | 0.22 (2.56) | 0.09 | 0.440 | 12.92 (2.59) | 0.90 (2.91) | 0.31 | 0.024 |

| WHOQOL-BREF Environmental domain | 14.50 (2.04) | 14.96 (2.11) | 0.23 (1.59) | 0.15 | 0.191 | 15.32 (1.91) | 0.16 (1.63) | 0.10 | 0.470 |

| PSS | 20.38 (7.36) | 16.46 (6.11) | −3.63 (5.13) | −0.71 | <0.001 | 14.70 (6.24) | −3.36 (7.31) | −0.46 | 0.001 |

| PRS | 179.26 (35.56) | 195.27 (28.11) | 18.57 (27.14) | 0.68 | <0.001 | 195.37 (30.91) | 16.07 (31.41) | 0.51 | 0.002 |

| Control group (TAU) | |||||||||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 9-week follow-up, mean (SD) | Difference baseline to 9-week follow-up, mean (SD) 3 | Cohen’s d baseline to 9-week follow-up 4 | p-value 1 | 6-month follow-up, mean (SD) | Difference baseline to 6-month follow-up, mean (SD) 3 | Cohen’s d baseline to 6-month follow-up 4 | p-value 2 | |

| WHOQOL Physical domain | 14.22 (2.77) | 14.61 (2.77) | 0.03 (2.41) | 0.01 | 0.951 | 14.57 (3.37) | 0.15 (2.23) | 0.07 | 0.722 |

| WHOQOL Psychological domain | 13.86 (3.32) | 14.54 (2.65) | 0.38 (2.31) | 0.16 | 0.351 | 14.39 (3.11) | 0.41 (2.44) | 0.17 | 0.369 |

| WHOQOL Social domain | 12.03 (3.22) | 12.83 (2.79) | 0.63 (2.58) | 0.24 | 0.180 | 12.31 (2.96) | 0.22 (2.48) | 0.09 | 0.627 |

| WHOQOL Environmental domain | 14.05 (2.68) | 14.94 (1.91) | 0.59 (1.84) | 0.32 | 0.076 | 14.52 (1.97) | 0.29 (1.75) | 0.16 | 0.374 |

| PSS | 16.15 (7.49) | 13.03 (6.25) | −2.75 (4.54) | −0.61 | 0.002 | 14.50 (9.37) | −1.40 (7.83) | −0.18 | 0.335 |

| Control Group (TAU) | Intervention Group (Wildman Programme) | Intervention vs. Control | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted Value (SD) | Predicted Mean Difference (SD) | CI (p-Value) | Predicted Value (SD) | Predicted Mean Difference (SD) | CI (p-Value) | Difference in PMD (SD) 1 | CI (p-Value) | ||

| WHOQOL-BREF Physical domain | Baseline | 14.26 (0.46) | 13.41 (0.30) | ||||||

| 9-week follow-up | 14.48 (0.49) | 0.22 (0.46) | −0.69; 1.13 (0.636) | 14.38 (0.31) | 0.97 (0.25) | 0.49; 1.45 (0.0001) | 0.75 (0.53) | −0.28; 1.78 (0.1530) | |

| 6-month follow-up | 14.38 (0.57) | 0.12 (0.39) | −0.65; 0.89 (0.760) | 14.95 (0.34) | 1.54 (0.33) | 0.90; 2.18 (0.0000) | 1.42 (0.51) | 0.42; 2.42 (0.0056) | |

| WHOQOL-BREF Psychological domain | Baseline | 13.30 (0.51) | 12.97 (0.27) | ||||||

| 9-week follow-up | 13.77 (0.43) | 0.48 (0.43) | 0.37; 1.32 (0.2691) | 13.46 (0.28) | 0.49 (0.22) | 0.07; 0.92 (0.0236) | 0.02 (0.48) | −0.93; 0.97 (0.9672) | |

| 6-month follow-up | 13.72 (0.54) | 0.42 (0.48) | −0.51; 1.35 (0.3732) | 13.91 (0.38) | 0.95 (0.35) | 0.26; 1.64 (0.0072) | 0.52 (0.59) | −0.63; 1.68 (0.3756) | |

| WHOQOL-BREF Social domain | Baseline | 11.92 (0.52) | 11.92 (0.27) | ||||||

| 9-week follow-up | 12.56 (0.51) | 0.64 (0.47) | −0.27; 1.55 (0.1685) | 12.13 (0.26) | 0.21 (0.30) | −0.37; 0.79 (0.4794) | −0.43 (0.55) | −1.51; 0.65 (0.4353) | |

| 6-month follow-up | 12.06 (0.52) | 0.15 (0.41) | −0.65; 0.94 (0.7163) | 12.51 (0.34) | 0.60 (0.38) | −0.16; 1.35 (0.1203) | 0.45 (0.56) | −0.65; 1.55 (0.4239) | |

| WHOQOL-BREF Environmental domain | Baseline | 13.94 (0.44) | 14.62 (0.19) | ||||||

| 9-week follow-up | 14.51 (0.38) | 0.57 (0.28) | 0.02; 1.12 (0.0440) | 14.95 (0.22) | 0.33 (0.19) | −0.04; 0.71 (0.0831) | −0.24 (0.34) | −0.91; 0.43 (0.4875) | |

| 6-month follow-up | 14.32 (0.40) | 0.38 (0.27) | −0.14; 0.90 (0.1493) | 14.91 (0.24) | 0.29 (0.22) | −0.15; 0.73 (0.1911) | −0.09 (0.35) | −0.77; 0.59 (0.7969) | |

| PSS | Baseline | 17.36 (1.32) | 20.14 (0.68) | ||||||

| 9-week follow-up | 14.34 (1.17) | −3.02 (0.93) | −4.84; −1.21 (0.0011) | 16.26 (0.68) | −3.88 (0.60) | −5.06; −2.71 (0.0000) | −0.86 (1.10) | −3.02; 1.30 (0.4355) | |

| 6-month follow-up | 15.84 (1.90) | −1.53 (1.67) | −4.79; 1.74 (0.3594) | 15.52 (0.83) | −4.63 (0.94) | −6.48; −2.78 (0.0000) | −3.10 (1.92) | −6.85; 0.66 (0.1058) | |

| PRS 3 | Baseline | NA | 178.70 (3.90) | Reference | NA | ||||

| 9-week follow-up | 196.46 (3.13) | 17.76 (3.48) | 10.95; 24.57 (0.0000) | ||||||

| 6-month follow-up | 194.82 (3.63) | 16.12 (3.99) | 8.30; 23.94 (0.0001) | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Høegmark, S.; Andersen, T.E.; Grahn, P.; Mejldal, A.; Roessler, K.K. The Wildman Programme—Rehabilitation and Reconnection with Nature for Men with Mental or Physical Health Problems—A Matched-Control Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111465

Høegmark S, Andersen TE, Grahn P, Mejldal A, Roessler KK. The Wildman Programme—Rehabilitation and Reconnection with Nature for Men with Mental or Physical Health Problems—A Matched-Control Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111465

Chicago/Turabian StyleHøegmark, Simon, Tonny Elmose Andersen, Patrik Grahn, Anna Mejldal, and Kirsten K. Roessler. 2021. "The Wildman Programme—Rehabilitation and Reconnection with Nature for Men with Mental or Physical Health Problems—A Matched-Control Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111465

APA StyleHøegmark, S., Andersen, T. E., Grahn, P., Mejldal, A., & Roessler, K. K. (2021). The Wildman Programme—Rehabilitation and Reconnection with Nature for Men with Mental or Physical Health Problems—A Matched-Control Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111465