Abstract

Industrial enterprises have provided outstanding contributions to economic development in countries around the world. The green development of industrial enterprises has received widespread attention from researchers. However, existing research lacks the tools to scientifically measure the green development behavior and performance of industrial enterprises. According to the theory of green development behavior and performance of industrial enterprises (GDBP-IE), the aim of this paper is to provide a tool for scientifically measuring such behavior and performance. This paper determined the initial scale through literature analysis and expert discussions and obtained valid samples from 31 provincial administrative regions in China through field and online surveys (N = 853). The exploratory factor analysis method was used to test the reliability and validity of the scale. The main conclusions are as follows: (1) The reliability and validity of the GDBP-IE scale are good; (2) the GDBP-IE scale, with a total of 70 items, comprises four sub-scales: The internal factors sub-scale, the external factors sub-scale, the green development behavior of industrial enterprises sub-scale, and the green development performance of industrial enterprises sub-scale. Among them, the internal factors sub-scale, with a total of 13 items, consists of two dimensions: Corporate tangible resources and corporate intangible resources. The external factors sub-scale, with a total of 23 items, consists of three dimensions: Market environment; public supervision; policy and institutional environment. The green development behavior of industrial enterprises sub-scale, with a total of 18 items, consists of two dimensions: Clean production behavior and green supply chain management practice. The green development performance of industrial enterprises sub-scale, with a total of 16 items, comprises three dimensions: Corporate social performance, corporate financial performance, and corporate environmental performance. The findings enrich the research on corporate organizational behavior, green behavior, and green development system theory, and provide tools for further empirical testing. The development and verification of green development behavior and performance of industrial enterprises can help guide various types of industrial enterprises in transforming to green development and can provide a reference for the government to formulate targeted green development policies.

1. Introduction

Since the publication of Our Common Future in 1987, the importance of sustainable development has been recognized by researchers around the world [1]. Sustainable development is defined as development that meets the need of the present generation without compromising the needs of future generations. To guide the global efforts of sustainable development in 2015–2030, the United Nations Development Programme breaks down sustainable development goals into 17 detailed goals: No poverty; zero hunger; good health and well-being; quality education; gender equality; clean water and sanitation; affordable and clean energy; decent work and economic growth; industry, innovation, and infrastructure; reduced inequalities; sustainable cities and communities; responsible consumption and production; climate action; life below water; life on land; peace, justice, and strong institutions; and partnerships for the goals [2].

In recent years, research on green development (GD) has attracted researchers’ attentions. Green development is a complex adaptive system closely related to the social, economic, and natural environment. It is affected by production, life, policies, and the GD concept, and its core is the human and natural life communities [3,4,5]. Whereas both GD and sustainable development focus on the natural environment and economic development, GD emphasizes the systematism of the economy and natural environment.

According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China [6], from 2016 to 2018, China’s industrial added value accounted for more than 40% of GDP. Industrial enterprises have provided outstanding contributions to the economic development of many countries, including China. However, when promoting economic development, the organizational behavior of industrial enterprises can easily produce negative environmental impacts. This characteristic is particularly prominent in developing countries, for example, China [3], India [7], and Malaysia [8]. According to data surveyed by the National Bureau of Statistics of China [9], annual industrial solid waste generation in China is 3159.92 million tons, of which 54.64% is comprehensively used. In other words, Chinese industrial enterprises still need to accelerate the transition to green development and reduce their negative impact on the environment [10]. To reduce the negative environmental impact of economic development, GD policies have emerged at a historic moment and have received responses from countries around the world, especially China [11].

Many researchers have evaluated various aspects of the performance of GD, for example, green industry performance index and green industry progress index [12], green total-factor growth performance [13], green total-factor productivity [14], efficiency of innovation and environmental performance [15], green innovation performance [16], organizational performance and environmental performance of green human resource management [17], and green supply chain management practices and performance [18,19]. Although these studies deeply enriched the field literature on GD performance, a scientific and effective tool is lacking to measure the GD behavior and performance of industrial enterprises (GDBP-IE).

For a long time, the relationship between corporate organizational behavior and performance was the focus of many management researchers [20,21,22]. The theory of GDBP-IE states that in order to respond to environmental protection and enterprise development, the green behavior formed by industrial enterprises as an organizational carrier is called the GD behavior of industrial enterprises, including clean production behavior and green supply chain management practices [23]. Thus, how is it possible to scientifically and effectively measure and verify GDBP-IE? To answer the question, we aimed to provide a scientific tool for measuring GDBP-IE according to the GDBP-IE theory.

Scale development can be used to scientifically and effectively measure emerging academic concepts and has been widely recognized in the fields of environmental psychology and environmental management [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Therefore, according to the procedures of scale development, we created a GDBP-IE scale with four sub-scales using a questionnaire survey and an exploratory factor analysis method, and tested its reliability and validity. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a GDBP-IE scale has been developed and verified.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews relevant literature in terms of three aspects: Influencing factors, the green development behavior of industrial enterprises (GDB-IE), and the green development performance of industrial enterprises (GDP-IE). Section 3 describes the steps involved in scale development, the exploratory factor analysis method, and data sources. Section 4 describes the results of the exploratory factor analysis, including the principal component analysis, validity analysis, and reliability analysis. Section 5 introduces the similarities and differences between similar research results and this study, and objectively outlines the limitations and future research directions. The final section summarizes the main new findings and management implications.

2. Literature Review

Industrial enterprises are affected by production, life, and policies. Therefore, the GD of industrial enterprises has been increasingly valued by researchers [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. This section provides a review of the relevant literature in terms of three aspects: Influencing factors, GDB-IE, and GBP-IE. Table 1 shows the relevant literature on the GD behavior and performance of industrial enterprises.

Table 1.

Relevant literature on the green development (GD) behavior and performance of industrial enterprises.

2.1. Internal Factors (IFs)

The IFs of an enterprise are composed of enterprise resources. Resource-based view of the firm was first proposed by Wernerfelt [32], and then continuously developed and improved by researchers [33]. As a competitive advantage of an enterprise, resources can be used to distinguish the level of enterprise performance [34]. According to a resource-based view of the firm, the enterprise is regarded as a collection of resources, and a powerful framework was proposed to unify and combine several different resources to generate a competitive advantage. However, no uniform standard exists for the definition or classification of resources in academia [35]. For example, some studies suggested that enterprise resources include tangible, intangible, and human resources [36], whereas others suggested that enterprise resources include only tangible and intangible resources [10,23,37]. The key to these research disputes is human resources. From a macro perspective, however, tangible resources can explain the scope of human resources. Per previous research, dividing resources into tangible and intangible resources is a generally accepted paradigm.

Corporate tangible resources refer to visible and tangible resources having a physical form, such as machinery, equipment, workshops, and raw materials owned by the enterprise [38,39]. In a resource-based view of the firm, tangible resources are an important factor in the study of corporate performance because of their controllability. Newbert [40] stated that tangible resources must be considered in the actual research of the resource-based theory of the firm, which can not only directly result in high performance output but also produce a competitive advantage [41].

Corporate intangible resources are resources that do not have a physical form but can provide certain rights to the enterprise, such as patent rights, land use rights, non-patented technologies, copyrights, trademark rights, and reputation [42,43]. Corporate intangible resources are vital to the survival and development of an enterprise and directly impact the competitiveness of the enterprise [38]. Newbert [40] thought that intangible resources play the greatest role in the success of enterprises. Therefore, the phenomenon of "weak advantage over strong" in the market can be understood. The competence-based theory of the firm showed that corporate capabilities played an important role in corporate performance [44]. According to a resource-based view of the firm, capabilities are an important part of corporate intangible resources. However, intangible resources are dual in nature, and their existence can also place enterprises at a competitive disadvantage or even result in bankruptcy [45].

At present, corporate tangible and intangible resources are considered to be the internal factors of the enterprise. However, the existing studies lack a comprehensive consideration of the IFs scale regarding GDB-IE. In order to overcome for this shortcoming, based on previous studies, we comprehensively considered GDB-IE and developed an IFs sub-scale.

2.2. External Factors (EFs)

Institutions are artificially designed restrictions that constitute political, economic, and social communication, including informal institutions (e.g., normative constraints, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct) and formal institutions (e.g., the constitution, laws, and property rights) [46]. The instability and unsustainability of the institutions can increase transaction costs, whereas the improvement of the institution environment can reduce transaction costs and improve transaction efficiency [47]. Enterprise production and operation activities are embedded in a certain institutional environment. Therefore, the policy and institutional environment is closely related with the development strategy of the enterprise.

In their theory of Industrial Organization, Bain [48,49] advocated researching industrial economic issues with the structure–conduct–performance paradigm. The analysis framework dictates that a certain market structure affects market behavior and then market performance. In this regard, Stigler et al. [50] hold different views. They think that an adverse impact relationship may exist among the three-fold paradigm, that is, changes in market performance will adversely affect market behavior and market structure. If the transformation of GD achievements of industrial enterprises is regarded as a kind of market behavior, the influence of a certain market structure and market performance on market behaviors can be analyzed (i.e., transformation of GD achievements of industrial enterprises) [51]. Therefore, the market environment is important in the GD of industrial enterprises.

From historical and intellectual perspectives, in developing countries like China, to promote the GD of industrial enterprises, public supervision is indispensable. Public supervision can compensate for the deficiencies of the legal system and play a role in transmitting information to enterprises, thereby promoting enterprises to GD [52]. Generally, the public can obtain relevant information through television, radio, newspapers, the Internet, and other media, and indirectly exert pressure on enterprises through public opinion [53]. Wu [54] found that as a third-party independent supervisor, the news media are an important driving force for enterprises to actively fulfill their social responsibilities. Porter et al. [55] considered the media and government agencies as important sources of corporate responsibility for the consequences of their actions. In addition, to maintain the enterprise’s good reputation and social image, the management of industrial enterprises will actively undertake social responsibilities through GD and positively respond to relevant media reports [56,57].

However, the existing studies lack an EFs scale that comprehensively considers GDB-IE. In the context of China, tools for measuring policy and institutional environments, market environments, and public supervision through scales have not yet been developed. To address this shortcoming, we comprehensively considered GDB-IE and developed an EFs sub-scale based on previous studies.

2.3. Green Development Behavior of Industrial Enterprises (GDB-IE)

The green development behavior of industrial enterprises has attracted increasing attention from environmental management researchers. The green production behavior of industrial enterprises plays an important role in production, management, and consumption [58,59]. Li et al. [23] constructed a theoretical model of GDB-IE through research on grounded theory of Chinese industrial enterprises. In this study, we considered GDB-IE is embodied in clean production behavior [60,61] and green supply chain management practices [62,63]. Although clean production behavior cannot produce economic benefits in the short term, long-term clean production technology innovation can change the production costs of enterprises and enhance corporate competitive advantages. To improve environmental performance, enterprises are subject to government regulation in the short term and passively increase investment in environmental technology upgrades. However, forcing enterprises to increase costs can damage competitive advantages [64,65].

With the continuous deterioration of the resources and environment, the contradiction amongst economic development, environmental protection, and social development has become increasingly prominent. Enterprise operation management models need to seek a path to GD. Therefore, green supply chain management has become an important operational strategy for the GD of enterprises [66,67]. Since the 20th century, some leading enterprises have implemented green supply chain management and achieved significant environmental and economic benefits. Green supply chain management practices are considered to be traditional supply chain activities that limit the harmful effects on services or production products throughout the life cycle, including green manufacturing, green packaging, and reverse logistics [68,69,70,71].

However, existing studies lack a scale for GDB-IE. In particular, in the Chinese context, tools for measuring clean production behavior and green supply chain management practice through scales have not yet been developed. To address this shortcoming, we developed a GDB-IE sub-scale for GDB-IE based on previous studies.

2.4. Green Development Performance of Industrial Enterprises (GDP-IE)

The triple bottom line theory considers corporate financial performance, corporate environmental performance, and corporate social performance in a framework [72], and the theory is accepted by researchers in the field of GD [23,73,74,75,76].

Although most researchers support studies on enterprise performance from the perspective of supply chain management practices, a comprehensive consideration of GDB-IE and its influencing factors is lacking. Heterogeneity exists between different industries, and the GD opportunities and challenges faced by different industries are different. The GD of industrial enterprises is not completely consistent with that of other enterprises. Therefore, the introduction of triple bottom line theory into the research of industrial enterprises’ GD behavior and performance and the influencing factors can compensate for this deficiency. In addition, researchers engaged in GD performance research mostly focus on the construction and evaluation of indicator systems but have not provided a measurable scale tool. To address this limitation, we comprehensively considered GDB-IE and its influencing factors based on previous studies, and developed a GDP-IE sub-scale.

3. Materials and Methods

First, the main structure of the scale was determined through literature analysis. According to the theoretical model of industrial enterprises’ GD behavior and performance constructed by Li et al., we determined that the scale consists of four parts: Internal factors, external factors, GD behavior of industrial enterprises, and GD performance of industrial enterprises [23]. The items of internal factors sub-scale were sourced from previous studies [77,78,79,80,81], the external factors sub-scale items were mainly sourced from [51,82], those of GD behavior of industrial enterprises sub-scale were mainly obtained from [79,80,83], and for the items of GD performance of industrial enterprises sub-scale, we mainly referred to references [77,84,85].

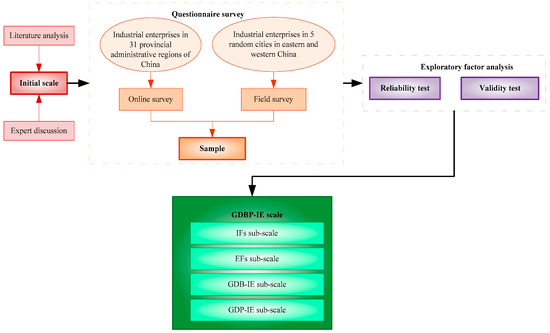

Second, in July 2018, initial item pools were evaluated and affirmed through a meeting discussion. The researchers involved in the discussion consisted of 3 professors and 2 doctors and met the following two conditions: (1) From the field of management science; (2) familiar with the scale development process. Anonymous voting was used to vote for all items from the literature and self-developed items, and items with less than four votes were deleted. Finally, a five-level Likert scale containing 70 items was obtained as the initial scale: IFs sub-scale (13 items), EFs sub-scale (23 items), GDB-IE sub-scale (18 items), and GDP-IE sub-scale (16 items). Figure 1 shows the research framework.

Figure 1.

Framework for GDBP-IE scale development. Note: IFs—internal factors; EFs—external factors; GDB-IE—green development behavior of industrial enterprises; GDP-IE—green development performance of industrial enterprises.

3.1. Data Sources

Using a random sampling strategy, two methods were used to obtain samples: Field survey and online survey. From September 2018 to June 2019, we randomly selected workers and managers of industrial enterprises from five cities in Eastern and Western China (i.e., Zhenjiang, Wuxi and Changzhou in Jiangsu Province, and Chengdu and Luzhou in Sichuan Province) and issued 600 questionnaires. According to survey data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China [1], the industrial sales value of industrial enterprises above the designated size in Jiangsu and Sichuan in 2016 were the highest values in Eastern and Western China. Therefore, we chose Jiangsu and Sichuan provinces for our field research. During this period, 400 questionnaires were issued to industrial workers and managers from 31 provinces in China (excluding Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan) through online surveys using a commissioned questionnaire website www.wjx.cn. After removing the unqualified questionnaires, 853 valid samples were finally obtained, and the effective rate was 85.3%. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics of the samples.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics (N = 853).

The results are shown in Table 2. (1) From the perspective of sex distribution, 572 male (67.06%) and 281 female (32.94%) employees were included in the sample. The proportion of men was slightly higher than that of women, which is consistent with the sex distribution characteristics of industrial enterprises in actual work. (2) From the perspective of age distribution, people aged under 30, 30–39, 40–49 years, and older than 50 years were 250 (29.31%), 366 (42.91%), 177 (20.75%), and 60 (7.03%), respectively. The samples were mainly middle-aged and young people, which is consistent with the age distribution characteristics of industrial enterprises in actual work. (3) From the perspective of position distribution, workers and managers in the sample accounted for 364 (42.67%) and 489 (57.33%), respectively. The difference between the proportion of workers and managers in the sample is small, but the proportion of managers is slightly higher than workers. In the organization, managers have the right to make management decisions on organizational behavior, which is in line with the characteristics of management decisions of industrial enterprises in actual work. (4) From the perspective of level of education, 494 (57.91%) employees had bachelor’s degrees in the sample and 359 (42.09%) had other degrees. The samples were dominated by bachelor’s degrees, which is consistent with the level of education characteristics of industrial enterprises in the actual workplace. (5) From the perspective of the number of employees in an enterprise, those working in three types of enterprises (i.e., less than 300, 301–1000, and more than 1000 employees) were 309 (36.23%), 310 (36.34%), and 234 (27.43%), respectively. In other words, the samples covered large, medium, and small industrial enterprises. Therefore, the sample was representative.

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

The exploratory factor analysis method was used to test the reliability and validity of the scale. Exploratory factor analysis is a common method used for scale development, including reliability tests and validity tests. We used SPSS 25.0 software (International Business Machines Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) to test the reliability and validity of the scale. In the analysis process, the following criteria were used to determine whether the items were reasonable:

(1) Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value. Kaiser [86] stated that, “when the KMO value is in the 0.90s, marvelous; in the 0.80s, meritorious; in the 0.70s, middling; in the 0.60s, mediocre; in the 0.50s, miserable; below 0.50, unacceptable”. In other words, if a factor analysis is suitable, the KMO value of the questionnaire must be greater than 0.6.

(2) Factor loadings. Factor loadings reflect the importance of the item to the extracted common factor, and the value cannot be less than 0.4.

(3) Communality. Communality is the proportion of variation the item can explain for a common trait or attribute.

(4) Cronbach’s α coefficient value. The Cronbach’s α coefficient value is an index used to judge the internal consistency of the questionnaire in reliability analysis. When the Cronbach’s α coefficient value is above 0.9, the reliability of the scale is ideal; when between 0.8 and 0.899, the reliability of the scale is very good; when between 0.7 and 0.799, the reliability of the scale is good; when between 0.6 and 0.699, the reliability of the scale is acceptable; when between 0.5 to 0.599, the reliability of the scale is acceptable but low; when less than 0.5, the reliability of the scale is unacceptable.

(5) Corrected item and total correlation. The corrected item and total correlation coefficient value is an index used for judging the internal consistency of the item and the remaining items. If the coefficient value is less than 0.4, the internal consistency of the item and the remaining items is low.

4. Results

Validity was tested by KMO and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Table 3 shows the KMO and Bartlett’s test of sphericity of the scale.

Table 3.

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity.

The results in Table 3 show that the KMO values of the IFs sub-scale, EFs sub-scale, GDB-IE sub-scale, and GDP-IE sub-scale were 0.938, 0.930, 0.948, and 0.935, respectively, all of which are higher than 0.9. In addition, the significance of Bartlett’s test of sphericity for the scale was less than 0.001. Therefore, common factors exist among the variables, which indicates suitability for further exploratory factor analysis. Next, we analyzed the principal components and reliability of the scale separately.

4.1. Development and Verification of IFs sub-Scale

4.1.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Table 4 shows the principal component and factor loadings of the IFs sub-scale. The factor loadings were between 0.559 and 0.799 (higher than 0.4); the communality was between 0.488 and 0.681 (higher than 0.2), indicating that the scale is acceptable with a good interpretation reliability. Therefore, two factors of the IFs sub-scale were obtained through PCA, that is, corporate tangible resources (including nine items) and corporate intangible resources (including four items).

Table 4.

Principal component and factor loadings of IFs sub-scale (N = 853).

4.1.2. Reliability Analysis

Table 5 shows the reliability test results of the IFs sub-scale. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the IF sub-scale was 0.908 (above 0.9), indicating that the overall internal consistency of the scale is ideal. In addition, the Cronbach’s α coefficients of the two factors with corporate tangible resources and corporate intangible resources were 0.888 and 0.808 (above 0.8), respectively, indicating that the internal consistency of the factors is very good.

Table 5.

Test results of the internal factors (IFs) sub-scale (N = 853).

4.2. Development and Verification of EFs Sub-Scale

4.2.1. PCA

Table 6 shows the principal component and factor loadings of the EFs sub-scale. The factor loadings were between 0.466 and 0.759 (higher than 0.4); the communality was between 0.412 and 0.659 (higher than 0.2), which indicates that the scale is acceptable with a good interpretation reliability. Therefore, three factors of the EFs sub-scale were obtained through principal component analysis, that is, market environment (including 11 items), public supervision (including eight items), and policy and institutional environment (including four items).

Table 6.

Components and factor loadings of the external factors (EFs) sub-scale (N = 853).

4.2.2. Reliability Analysis

Table 7 shows the reliability test results of the EFs sub-scale. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the EFs sub-scale was 0.920 (higher than 0.9), indicating that the overall internal consistency of the scale is ideal. In addition, the Cronbach’s α coefficients of the three factors market environment, public supervision, and policy and institutional environment were 0.869, 0.845, and 0.827 (higher than 0.8), respectively, indicating that the internal consistency of the factors is very good.

Table 7.

Test results of the EFs sub-scale (N = 853).

4.3. Development and Verification of GDB-IE Sub-Scale

4.3.1. PCA

Table 8 shows the principal component and factor loadings of the GDB-IE sub-scale. The factor loadings were between 0.409 and 0.812 (higher than 0.4); and communality was between 0.266 and 0.672 (higher than 0.2), indicating that the scale is acceptable with a good interpretation reliability. Therefore, two factors of the GDB-IE sub-scale were obtained through principal component analysis: Clean production behavior (including 11 items) and green supply chain management practices (including eight items).

Table 8.

Component and factor loadings of the GDB-IE sub-scale (N = 853).

4.3.2. Reliability Analysis

Table 9 shows the reliability test results of the GDB-IE sub-scale. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the GDB-IE sub-scale was 0.925 (above 0.9), indicating that the overall internal consistency of the scale is ideal. In addition, the Cronbach’s α coefficients of the two factors clean production behavior and green supply chain management practices were 0.880 and 0.866 (above 0.8), respectively, indicating that the internal consistency of each factor is very good.

Table 9.

Reliability test results of the GDB-IE sub-scale (N = 853).

4.4. Development and Verification of GDP-IE Sub-Scale

4.4.1. PCA

Table 10 shows the principal component and factor loadings of the GDP-IE sub-scale. The factor loadings were between 0.543 and 0.824 (higher than 0.4); and communality was between 0.450 and 0.752 (higher than 0.2), indicating that the scale is acceptable with a good interpretation reliability. Therefore, three factors of the GDP-IE sub-scale were obtained through principal component analysis: Corporate social performance (including six items), corporate financial performance (including six items), and corporate environmental performance (including six items).

Table 10.

Component and factor loadings of the GDP-IE sub-scale (N = 853).

4.4.2. Reliability Analysis

Table 11 shows the reliability test results of the GDP-IE sub-scale. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the GDP-IE sub-scale was 0.909 (above 0.9), indicating that the overall internal consistency of the scale is ideal. In addition, the Cronbach’s α coefficients of corporate social performance, corporate financial performance, and corporate environmental performance were 0.845, 0.833, and 0.834 (above 0.8), respectively, indicating that the internal consistency of the factors is very good.

Table 11.

Test results of the GDP-IE sub-scale (N = 853).

5. Discussion

In the fields of environmental psychology and environmental management, exploratory factor analysis can be used to effectively measure the reliability and validity of factors. Through exploratory factor analysis, we found that the reliability and validity of the GDBP-IE scale is very good. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a GDBP-IE scale has been developed and verified.

We found that the GDBP-IE scale consists of four parts: IF, EF, GDB-IE, and GDP-IE. This is consistent with the conclusions of Li et al. [23]. However, Li et al. [23] only proposed a theoretical model without providing a method for measuring GDBP-IE. The GDBP-IE scale developed here effectively compensates for this deficiency and provides a scientific basis for further research on the mechanism of the GDBP-IE scale.

The GDBP-IE scale comprises IF, EF, GDB-IE, and GDP-IE sub-scales. The IFs sub-scale is composed of two dimensions: Corporate tangible resources and corporate intangible resources. This is consistent with the research by Newbert [40] and Muller and Kolk [41]. The EFs sub-scale has three dimensions: Market environment, public supervision, and policy and institutional environment. This is consistent with the research by North [46], Jaiswal and Kant [51], and Porter et al. [55]. The GDB-IE sub-scale is composed of two dimensions: Clean production behavior and green supply chain management practices. This is consistent with the research by Qin et al. [64] and Ahi and Searcy [67]. The GDP-IE sub-scale has three dimensions: Corporate social performance, corporate financial performance, and corporate environmental performance. This is consistent with the research by Elkington [73], Ahmed and Sarkar [76], and Li et al. [23].

This study inevitably has some limitations. The samples in this paper are from Chinese industrial enterprises only, so may not be applicable to other areas. Therefore, on the basis of our findings, the sample scope can be expanded to include other countries and regions in the future. Although we developed and validates the GDBP-IE scale, we did not consider agriculture or services. Therefore, on the basis of our scale, new scales can be developed in the future based on the characteristics of the agriculture or service industries.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

According to the theory of GDBP-IE, we developed and validated the GDBP-IE scale (Appendix A, Table A1). First, the initial scale was determined through literature analysis and expert discussion. Then, through field surveys and online surveys, valid samples were obtained from 31 provincial administrative regions in China (N = 853). Finally, the exploratory factor analysis method was used to test the reliability and validity of the scale. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The reliability and validity of the GDBP-IE scale is very good.

(2) The GDBP-IE scale consists of four sub-scales with a total of 70 items: IFs, EFs, GDB-IE, and GDP-IE sub-scales. Among them, the IFs sub-scale is composed of two dimensions with a total of 13 items: Corporate tangible resources and corporate intangible resources. The EFs sub-scale comprises three dimensions with a total of 23 items: Market environment, public supervision, and the policy and institutional environment. The GDB-IE sub-scale is composed of two dimensions—clean production behavior and green supply chain management practices—with a total of 18 items. The GDP-IE sub-scale comprises three dimensions—corporate social performance, corporate financial performance, and corporate environmental performance—with a total of 16 items.

6.2. Implications

The theoretical and practical implications of our findings are as follows:

(1) Theoretically, as an emerging field in corporate organizational behavior, the development and verification of the GDBP-IE scale helps enrich the literature on corporate organizational behavior. As an emerging field in green behavior, the development and verification of the GDBP-IE scale can help enrich green behavior theory. In addition, the development of the GDBP-IE scale can help further reveal the mechanism of the production subsystem in the GD system [3,87] and provide a tool for further empirical inspection.

(2) Practically, the development and verification of the GDBP-IE scale can help to correctly guide various types of industrial enterprises to transform to GD and provide a reference for the government to formulate targeted GD policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, software, writing—original draft preparation and visualization, X.L.; formal analysis, H.L.; supervision, project administration and funding acquisition, J.D.; methodology, data curation and validation, X.L and H.L.; investigation and resources, X.L., J.D. and H.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Special Funds of the National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 18VSJ038.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire items on the green development behavior and performance of industrial enterprises (GDBP-IE).

Table A1.

Questionnaire items on the green development behavior and performance of industrial enterprises (GDBP-IE).

| Sub-Scale | Dimensions | Codes | Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Factors (IFs) | Corporate tangible resources (CTR) | IFs1 | Our enterprise is an organization with a high awareness and mission of green production. |

| IFs2 | Our enterprise has a leadership that values green production. | ||

| IFs3 | Our enterprise has a department or organization in charge of environmental work. | ||

| IFs4 | Our enterprise has a special budget for green production. | ||

| IFs5 | Our enterprise has a leadership that is committed to green production. | ||

| IFs6 | The sufficient capital level of our enterprise can support green production. | ||

| IFs7 | Our enterprise regularly trains employees in green production-related skills. | ||

| IFs8 | Our enterprise has sufficient talent reserves related to green production. | ||

| IFs9 | Our enterprise has production equipment that fully meets the needs of green production. | ||

| Corporate intangible resources (CIR) | IFs10 | Our enterprise can easily design green ecological products. | |

| IFs11 | Our corporate products have the ability to register the green logo. | ||

| IFs12 | Our enterprise has the ability to market green products. | ||

| IFs13 | In the field of green production, our enterprise has stocked related advanced technologies. | ||

| External Factors (EFs) | Market environment (ME) | EFs1 | The enforcement of green production-related regulations in the market is strict. |

| EFs2 | The implementation of green production-related systems in the market is strict. | ||

| EFs3 | Consumers trust green products. | ||

| EFs4 | Green production helps to enhance corporate image and brand value. | ||

| EFs5 | Consumers tend to buy green products. | ||

| EFs6 | In the market, enterprises are heavily regulated. | ||

| EFs7 | In the market, the green production of enterprises has been actively supported. | ||

| EFs8 | In the market, enterprises’ participation in the construction of ecological industrial parks has been actively supported. | ||

| EFs9 | The customer (enterprise) has high requirements for the environment of our enterprise. | ||

| EFs10 | Investors place high demands on the environmental protection of our enterprise. | ||

| EFs11 | In the market, green production-related regulations and systems are highly practical. | ||

| Public supervision (PS) | EFs12 | Community residents are required to participate in the environmental impact approval process of surrounding enterprises. | |

| EFs13 | The public and the community will make petition letters or complaints about environmental violations of surrounding enterprises. | ||

| EFs14 | Residents of the community require surrounding enterprises to build public environmental protection infrastructure. | ||

| EFs15 | Social environmental organizations are very concerned about corporate environmental violations. | ||

| EFs16 | News media will report on corporate environmental violations. | ||

| EFs17 | Peers are very concerned about the enterprise’s green production capabilities. | ||

| EFs18 | Consumers pay great attention to the environmental violations of enterprises. | ||

| EFs19 | Green products have passed strict certification. | ||

| Policy and institutional environment (PIE) | EFs20 | The government has developed preferential land policies for enterprises adopting clean technologies. | |

| EFs21 | The government has developed investment and financing policies for enterprises adopting clean technologies. | ||

| EFs22 | The government has developed fiscal and tax incentives for enterprises adopting clean technologies. | ||

| EFs23 | The government actively implements preferential policies for cleaner production of enterprises. | ||

| Green Development Behavior of Industrial Enterprises (GDB-IE) | Clean production behavior (CPB) | GDB-IE1 | The production process of our enterprise strictly adheres to the requirements of cleaner production. |

| GDB-IE2 | Our enterprise is selecting and improving pro-environmental processes or equipment. | ||

| GDB-IE3 | Our enterprise purchases environmentally friendly processes and equipment. | ||

| GDB-IE4 | Our enterprise considers the need for cleaner production when designing products. | ||

| GDB-IE5 | Our enterprise actively builds a cleaner production brand. | ||

| GDB-IE6 | Our enterprise has promoted the image of cleaner production. | ||

| GDB-IE7 | Our enterprise cascades use energy between enterprises. | ||

| GDB-IE8 | Our enterprise recycles water between enterprises. | ||

| GDB-IE9 | Our enterprise is actively looking for partners to jointly achieve the goals of energy conservation and emission reduction. | ||

| GDB-IE10 | Our enterprise actively recycles and disposes of waste products. | ||

| Green supply chain management practices (GSCMP) | GDB-IE11 | Our enterprise conducts environmental and energy audits on the internal management of suppliers. | |

| GDB-IE12 | Our enterprise requires suppliers to provide design specifications for the environmentally friendly requirements of the products they purchase. | ||

| GDB-IE13 | Our enterprise evaluates suppliers’ environmentally friendly practices. | ||

| GDB-IE14 | In the supply chain, our enterprise is very concerned about the green technologies of other enterprises. | ||

| GDB-IE15 | Our enterprise purchases new energy-saving and low-carbon materials and new energy. | ||

| GDB-IE16 | In the supply chain, our enterprise actively shares energy-saving and emission-reduction technologies among enterprises. | ||

| GDB-IE17 | Our company chooses suppliers that have passed third-party environmental management system certification (e.g., ISO 14001). | ||

| GDB-IE18 | In the supply chain, our enterprise actively communicates information about byproducts between enterprises. | ||

| Green Development Performance of Industrial Enterprises (GDP-IE) | Corporate social performance (CSP) | GDP-IE1 | Customers increasingly trust our products. |

| GDP-IE2 | Our enterprise’s image and brand value have been enhanced. | ||

| GDP-IE3 | Our enterprise has improved product quality. | ||

| GDP-IE4 | Stakeholders have a high opinion of our enterprise. | ||

| GDP-IE5 | Our enterprise has improved relationships with the people in our communities. | ||

| GDP-IE6 | Our enterprise reduces the possibility of environmental accidents. | ||

| Corporate financial performance (CFP) | GDP-IE7 | Our enterprise has reduced material costs. | |

| GDP-IE8 | Our enterprise has reduced operating costs. | ||

| GDP-IE9 | Our enterprise has reduced energy costs. | ||

| GDP-IE10 | Our enterprise has reduced the cost of environmental governance (e.g., emissions, penalties). | ||

| GDP-IE11 | Our enterprise has improved long-term financial performance. | ||

| GDP-IE12 | Our enterprise has reduced procurement costs through material recycling. | ||

| Corporate environmental performance (CEP) | GDP-IE13 | Wastewater emissions from our enterprise have decreased. | |

| GDP-IE14 | The emissions of exhaust gas produced by our enterprise have decreased. | ||

| GDP-IE15 | The amount of solid waste produced by our enterprise has decreased. | ||

| GDP-IE16 | Our enterprise has reduced the consumption of dangerous, toxic, and harmful substances. |

References

- Brundtland, G.H.; Khalid, M.; Agnelli, S.; Al-Athel, S.; Chidzero, B. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Li, X.; Du, J.; Long, H. Theoretical framework and formation mechanism of the green development system model in China. Environ. Dev. 2019, 32, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D. Scale of water resources development and sustainability: Small is beautiful, large is great. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2011, 56, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargentis, G.; Ioannidis, R.; Karakatsanis, G.; Sigourou, S.; Lagaros, N.D.; Koutsoyiannis, D. The development of the Athens water supply system and inferences for optimizing the scale of water infrastructures. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. National Data. Available online: http://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Islam, M.; Managi, S. Green growth and pro-environmental behavior: Sustainable resource management using natural capital accounting in India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, N.A.; Abidin, N.Z.; Zailani, S.H.M.; Govindan, K.; Iranmanesh, M. Linking the environmental practice of construction firms and the environmental behaviour of practitioners in construction projects. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 121, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2019. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2019/indexch.htm (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Liu, H.; Long, H.; Li, X. Identification of critical factors in construction and demolition waste recycling by the grey-DEMATEL approach: A Chinese perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 8507–8525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, J.; Long, H. A Comparative Study of Chinese and Foreign Green Development from the Perspective of Mapping Knowledge Domains. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Yang, D.; Yang, F.; Luken, R.; Saieed, A.; Wang, K. Green industry development in China: An index based assessment from perspectives of both current performance and historical effort. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 250, 119457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiahuey, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y. Measuring green growth performance of China’s chemical industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Wang, M. Journey for green development transformation of China’s metal industry: A spatial econometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yu, B.; Yan, X.; Yao, X.; Liu, Y. Estimation of innovation’s green performance: A range-adjusted measure approach to assess the unified efficiency of China’s manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lai, S.B.; Wen, C.T. The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, S.M.; Al Bakri, A.A.; Elbanna, S. Leveraging “Green” Human Resource Practices to Enable Environmental and Organizational Performance: Evidence from the Qatari Oil and Gas Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabat, A.; Khodaverdi, R.; Olfat, L. An exploration of green supply chain practices and performances in an automotive industry. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 68, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namagembe, S.; Ryan, S.; Sridharan, R. Green supply chain practice adoption and firm performance: Manufacturing SMEs in Uganda. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2019, 30, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-W.; Chen, F.-F.; Luan, H.-D.; Chen, Y.-S. Effect of Green Organizational Identity, Green Shared Vision, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment on Green Product Development Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyrer, J.; Schiffinger, M.; Lang, R. Organizational commitment—A missing link between leadership behavior and organizational performance? Scand. J. Manag. 2008, 24, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-F.; Hsieh, T.-S. The impacts of perceived organizational support and psychological empowerment on job performance: The mediating effects of organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, J.; Long, H. Green Development Behavior and Performance of Industrial Enterprises Based on Grounded Theory Study: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armento, M.E.; Hopko, D.R. The environmental reward observation scale (EROS): Development, validity, and reliability. Behav. Ther. 2007, 38, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, M.; Matheau-Police, A.; Couty, C. Development of a scale of perceived environmental annoyances in urban settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluess, M.; Assary, E.; Lionetti, F.; Lester, K.J.; Krapohl, E.; Aron, E.N.; Aron, A. Environmental sensitivity in children: Development of the Highly Sensitive Child Scale and identification of sensitivity groups. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markle, G.L. Pro-environmental behavior: Does it matter how it’s measured? Development and validation of the pro-environmental behavior scale (PEBS). Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, A.; Stolberg, A.; Wagner, U. Coping with global environmental problems: Development and first validation of scales. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 754–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, R.B.; Stern, M.J.; Krohn, B.D.; Ardoin, N. Development and validation of scales to measure environmental responsibility, character development, and attitudes toward school. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisat, S.; Riemer, M. The environmental action scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, A.; Galloway, G. Socially desirable responding in an environmental context: Development of a domain specific scale. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S.L. Emprical Research on the Resource-based View of the Firm: An Assessment and Suggestions for Future Research. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohjola, M. The new economy in growth and development. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2002, 18, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Tishler, A. The Relationships between Intangible Organizational Elements and Organizational Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 1257–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Fan, B. Exploring open government data capacity of government agency: Based on the resource-based theory. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Xu, K.; Carnes, C.M. Resource based theory in operations management research. J. Oper. Manag. 2016, 41, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.L. Model Establishment and Analysis of Enterprise Value Creation System. Stat. Decis. 2007, 9, 44–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, R.; Scheumann, R.; Galeitzke, M.; Wolf, K.; Kohl, H.; Finkbeiner, M. Sustainable Corporate Development Measured by Intangible and Tangible Resources as Well as Targeted by Safeguard Subjects. Procedia CIRP 2015, 26, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S.L. Value, Rareness, Competitive Advantage, and Performance: A Conceptual-level Empirical Investigation of the Resource-based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, A.; Kolk, A. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Drivers of Corporate Social Performance: Evidence from Foreign and Domestic Firm in Mexico. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekera, I. How Best to Communicate Intangible Resources on Websites to Inform Corporate-Growth Reputation of Small Entrepreneurial Businesses. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 738–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A.; Waddock, S. Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. The Dynamic Resource-based View: Capability Lifecycles. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wang, T.; Zhao, C. Utility and Matching Measure Model of Firm Resources. Manag. Rev. 2016, 28, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Institutional Environment, Transaction Rule and Efficiency of Corporate Control Transfer. Econ. Res. J. 2009, 44, 92–105. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bain, J.S. Barriers to New Competition; Harvard University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, J.S. Industrial Organization; Harvard University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Stigler, G. The Organization of Industry; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green purchasing behaviour: A conceptual framework and empirical investigation of Indian consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. Policy Support, Supervision Response and Green Entrepreneurship of Leading Agricultural Enterprises. J. Northwest A&F Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2018, 18, 121–128. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Research on the Correlation among Environmental Information Disclosure, Industry Differences and Supervisory System. Account. Res. 2008, 248, 54–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D. Corporate Governance, Media Coverage and Coporate Social Responsibility. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2016, 218, 110–117. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and Society: The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Dyck, A.; Zingales, L. Private Benefits of Control: An International Comparison. J. Financ. 2004, 59, 537–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Luigi, Z. The Corporate Governace Role of the Media: Evidence From Russia. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1093–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiel, C.; Paço, A.D.; Alves, H. Generativity, sustainable development and green consumer behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Bu, Y.; Jin, M.; Mbroh, N. Green Financial Behavior and Green Development Strategy of Chinese Power Companies in the Context of Carbon Tax. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.A.L.; Delai, I.; de Castro, M.A.S.; Ometto, A.R. Quality tools applied to Cleaner Production programs: A first approach toward a new methodology. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L.C.; Amaral, F.G. Barriers and strategies applying Cleaner Production: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazairy, A.; von Haartman, R. Analysing the institutional pressures on shippers and logistics service providers to implement green supply chain management practices. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2020, 23, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, P.D.; Lawson, B.; Petersen, K.J.; Fugate, B. Investigating green supply chain management practices and performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2019, 39, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Zhao, L.; Wan, J. The Impact of Cleaner Production Technology on Corporate Economic and Environmental Performance: An Empirical Study Based on the 2009 China Metal Products Industry Survey. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 30, 49–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani, A.; Tarola, O.; Vergari, C. End-of-pipe or cleaner production? How to go green in presence of income inequality and pro-environmental behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 160, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, M.; Carter, C.R.; Liane Easton, P. Sustainable supply chain management: Evolution and future directions. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2011, 41, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahi, P.; Searcy, C. A comparative literature analysis of definitions for green and sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamzadeh, R.; Govindan, K.; Esmaeili, A.; Sabaghi, M. Application of fuzzy VIKOR for evaluation of green supply chain management practices. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 49, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamon, B.M. Designing the green supply chain. Logist. Inf. Manag. 1999, 12, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltayeb, T.K.; Zailani, S.; Ramayah, T. Green supply chain initiatives among certified companies in Malaysia and environmental sustainability: Investigating the outcomes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Holt, D. Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, Y.; Shao, J.; Lai, K.; Kang, M.; Park, Y. The impact of sustainability and operations orientations on sustainable supply management and the triple bottom line. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafrilla, J.-E.; Arce, G.; Cadarso, M.-Á.; Córcoles, C.; Gómez, N.; López, L.-A.; Monsalve, F.; Tobarra, M.-Á. Triple bottom line analysis of the Spanish solar photovoltaic sector: A footprint assessment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 114, 109311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, I.; Raj, A.; Srivastava, S.K. Supply chain channel coordination with triple bottom line approach. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 115, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Sarkar, B. Management of next-generation energy using a triple bottom line approach under a supply chain framework. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. Green supply chain management: pressures, practices and performance within the Chinese automobile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q. A Resource-based View on Realization Mechanism of Regulations for Promoting Green Purchasing Practices among Manufacturers. Manag. Rev. 2012, 10, 143–149. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Yang, Q. An Empirical Study on Enterprises’ Environmental Behaviors and Their Influencing Factors through Eco-industrial Parks Development in China. Manag. Rev. 2013, 25, 843–844. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Geng, Y. Statistics Analysis on Types of Chinese Manufacturers Based on Practice of Green Supply Chain management and Their Performance. Appl. Stat. Manag. 2006, 25, 392–399. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.B.; Wu, Y.; Feng, Z.L.; Hao, Z.T. Investigation of Green Behavior of Resource-based Enterprise in China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2015, 5–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S. Research on the Influencing Factors of Corporate Environmental Behavior. Stat. Decis. 2011, 22, 181–183. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q. An Empirical Study on Barriers for Implementing Green Supply Chain Management in Manufacturers. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2009, 19, 83–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Feng, Y.; Choi, S.B. The role of customer relational governance in environmental and economic performance improvement through green supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Shi, J. The Relationship between Open Innovation, Government Support and the Performance of Leading Agricultural Enterprises. Issues Agric. Econ. 2013, 9, 84–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, J.; Long, H. Dynamic analysis of international green behavior from the perspective of the mapping knowledge domain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 6087–6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).