Narrative Voice Matters! Improving Smoking Prevention with Testimonial Messages through Identification and Cognitive Processes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants Subsection

2.2. Independent Variable and Stimulus Materials

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

3.2. Effect of Narrative Voice on Identification with the Protagonist (H1)

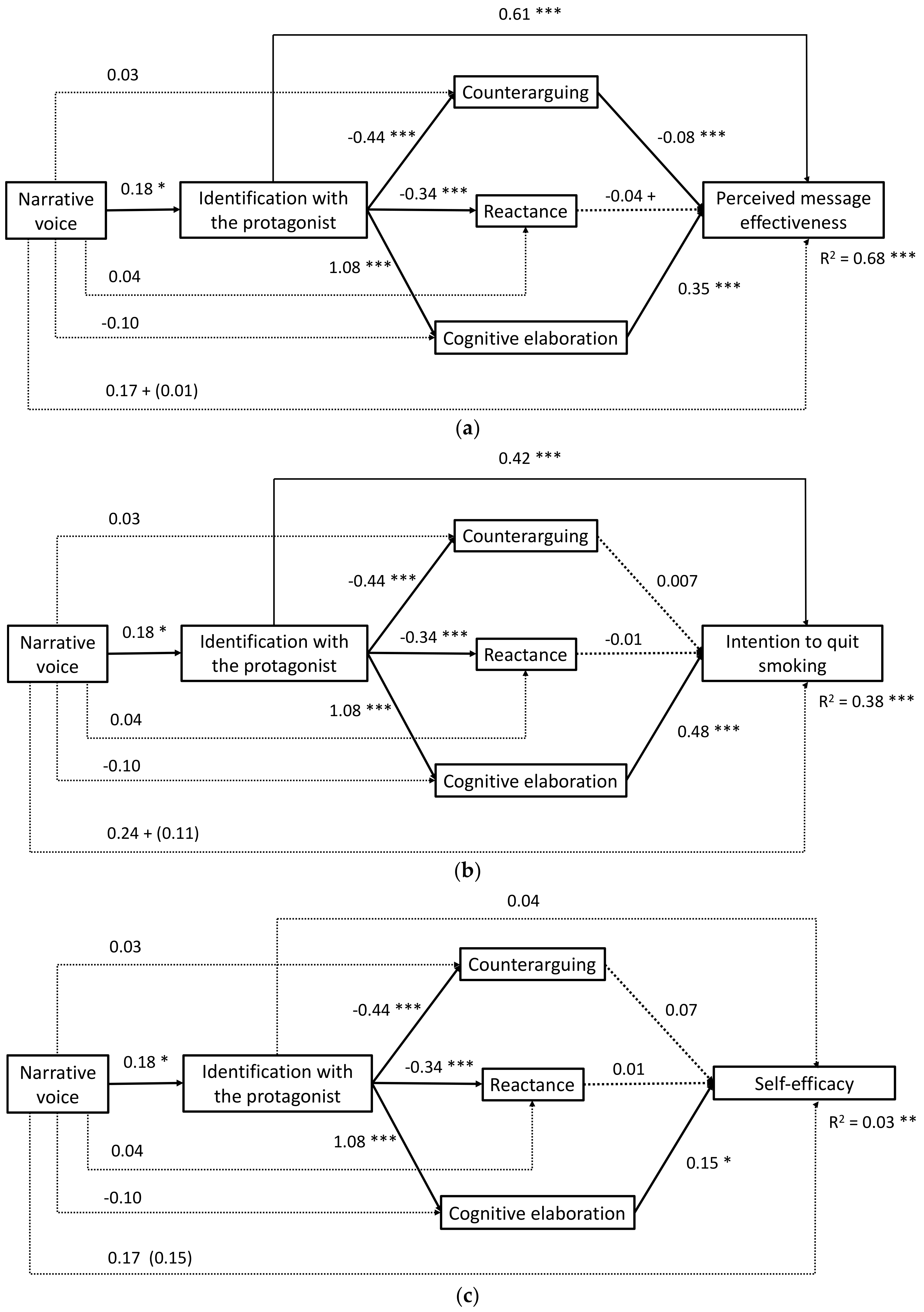

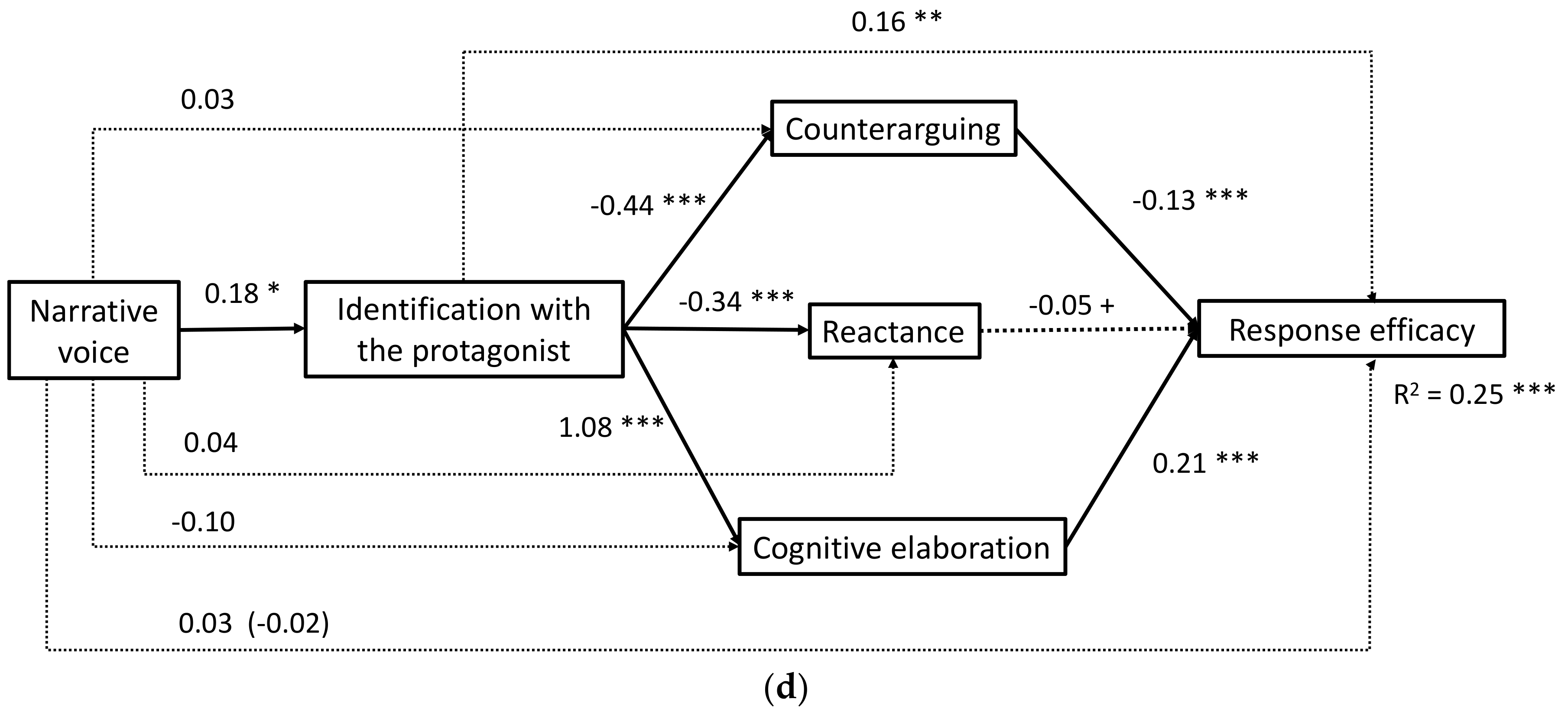

3.3. Testing a Serial-Parallel, Mediation Model (H2)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Cancer Society. Health Risks of Smoking Tobacco. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/tobacco-and-cancer/health-risks-of-smoking-tobacco.html#references (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- World Health Organization. Tobacco. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/ (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- AECC. Tabaquismo y Cáncer En España. Situación Actual [Smoking and Cancer in Spain. Current situation.]. Available online: https://www.aecc.es/sites/default/files/content-file/Informe-tabaquisimo-cancer-20182.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/consequences-smoking-exec-summary.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Dunlop, S.M.; Wakefield, M.; Kashima, Y. Pathways to persuasion: Cognitive and experiential responses to health-promoting mass media messages. Commun. Res. 2010, 37, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. When similarity strikes back: Conditional persuasive effects of character-audience similarity in anti-smoking campaign. Hum. Commun. Res. 2019, 45, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braverman, J. Testimonials versus informational persuasive messages: The moderating effect of delivery mode and personal involvement. Commun. Res. 2008, 35, 666–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, K.; Willington, S.F.; Blake, K.K. Media effects and population health. In The SAGE Handbook of Media Processes and Effects; Nabi, R.L., Oliver, M.B., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- Myrick, J.G. Media effects and health. In Media Effects. Advances in Theory and Research; Oliver, M.B., Raney, A.A., Bryant, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 308–323. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Shi, R.; Cappella, J.N. Effect of character–audience similarity on the perceived effectiveness of antismoking PSAs via engagement. Health Commun. 2016, 31, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braddock, K.; Dillard, J.P. Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Commun. Monogr. 2016, 83, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebregs, S.; Van den Putte, B.; Neijens, P.; de Graaf, A. The differential impact of statistical and narrative evidence on beliefs, attitude, and intention: A meta-analysis. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, G.F.; Libby, L.K. Changing beliefs and behavior through experience-taking. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Krieken, K.; Hoeken, H.; Sanders, J. Evoking and measuring identification with narrative characters: A linguistic cues framework. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.C.; Greene, K. Role of transportation in the persuasion process: Cognitive and affective responses to antidrug narratives. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Bell, R.A.; Taylor, L.D. Persuasive effects of point of view, protagonist competence, and similarity in a health narrative about type 2 diabetes. J. Health Commun. 2017, 22, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, K.R. I, you, or he: Examining the impact of point of view on narrative persuasion. Media Psychol. 2018, 21, 700–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Dahlstrom, M.F.; Richards, A.; Rangarajan, S. Influence of evidence type and narrative type on HPV risk perception and intention to obtain the HPV vaccine. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Graaf, A.; Sanders, J.; Hoeken, H. Characteristics of narrative interventions and health effects: A review of the content, form, and context of narratives in health-related narrative persuasion research. Rev. Commun. Res. 2016, 4, 88–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Bell, R.A.; Taylor, L.D. Narrator point of view and persuasion in health narratives: The role of protagonist–reader similarity, identification, and self-referencing. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.C.; Brock, T.C. In the mind’s eye: Transportation-imagery model of narrative persuasion. In Narrative Impact. Social and Cognitive Foundations; Green, M.C., Strange, J.J., Brock, T.C., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer-Gusé, E. Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Commun. Theory 2008, 18, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.D.; Rouner, D. Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Commun. Theory 2002, 12, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, E.M.; Miller, G.; Hosenfeld, C.; Mendelsohn, A.; Russell, W.; James, J.; Greene, A.; Joseph, D. Person and tense in narrative interpretation. Discourse Process. 1997, 24, 271–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; McGlone, M.S.; Bell, R.A. Persuasive effects of linguistic agency assignments and point of view in narrative health messages about colon cancer. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Commun. Soc. 2001, 4, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, J.J.; Barrios, I. Changing real-world beliefs with controversial movies: Processes and mechanisms of narrative persuasion. J. Commun. 2012, 62, 514–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer-Gusé, E.; Nabi, R.L. Explaining the effects of narrative in an entertainment television program: Overcoming resistance to persuasion. Hum. Commun. Res. 2010, 36, 26–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, J.J.; Vega, J. Identification with characters, elaboration, and counterarguing in entertainment-education interventions through audiovisual fiction. J. Health Commun. 2016, 2, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederdeppe, J.; Kim, H.K.; Lundell, H.; Fazili, F.; Frazier, B. Beyond counterarguing: Simple elaboration, complex integration, and counterelaboration in response to variations in narrative focus and sidedness. J. Commun. 2012, 62, 758–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rains, S.A. The nature of psychological reactance revisited: A meta-analytic review. Hum. Commun. Res. 2013, 39, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change; Springer: Wiesbaden, German, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, B.; Yeykelis, L.; Cummings, J.J. The use of media in media psychology. Media Psychol. 2017, 19, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.; Peter, J.; Valkenburg, P.M. Message variability and heterogeneity: A core challenge for communication research. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2015, 39, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Bigman, C.A.; Leader, A.E.; Lerman, C.; Cappella, J.N. Narrative health communication and behavior change: The influence of exemplars in the news on intention to quit smoking. J. Commun. 2012, 62, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Lee, T.K. Conditional effects of gain–loss-framed narratives among current smokers at different stages of change. J. Health Commun. 2017, 22, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Kozlowski, L.T.; Frecker, R.C.; Fagerstrom, K.O. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991, 86, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, M.F.; Niederdeppe, J.; Gao, L.; Zhu, X. Operational and conceptual trends in narrative persuasion research: Comparing health-and non-health-related contexts. Int. J. Commun. 2017, 11, 4865–4885. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L. Targeting smokers with empathy appeal antismoking public service announcements: A field experiment. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, D.J. Message pretesting using assessments of expected or perceived persuasiveness: Evidence about diagnosticity of relative actual persuasiveness. J. Commun. 2018, 68, 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, A.; Waters, E.A.; Kaphingst, K.A.; Caburnay, C.A.; Sanders Thompson, V.L.; Boyum, S.; Kreuter, M.W. Examining interpretations of graphic cigarette warning labels among us youth and adults. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spek, V.; Lemmens, F.; Chatrou, M.; Kempen, S.; Pouwer, F.; Pop, V. Development of a smoking abstinence self-efficacy questionnaire. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2013, 3, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Leech, N.L. Post hoc power: A concept whose time has come. Understandg. Stat. 2004, 3, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, D.J. Brief report: Post hoc power, observed power, a priori power, retrospective power, prospective power, achieved power: Sorting out appropriate uses of statistical power analyses. Commun. Methods Meas. 2007, 1, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.C.; Greene, K. Examining narrative transportation to anti-alcohol narratives. J. Subst. Use 2013, 18, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer-Gusé, E.; Chung, A.H.; Jain, P. Identification with characters and discussion of taboo topics after exposure to an entertainment narrative about sexual health. J. Commun. 2011, 61, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, A.; Van Leeuwen, L. The role of absorption processes in narrative health communication. In Narrative Absorption; Hakemulder, F., Kuipers, M.M., Tan, E.S., Bálint, K., Doicaru, M.M., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 271–292. [Google Scholar]

- Pirlott, A.G.; MacKinnon, D.P. Design approaches to experimental mediation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 66, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean (SD) or Percentage | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | M = 35.27 | 18–55 |

| SD = 10.97 | ||

| Sex | Male: 258 (49.1%) | |

| Female: 267 (50.9%) | ||

| Fagerström test | M = 4.65 | 0–10 |

| SD = 2.23 |

| Measure | Response Options | Reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) |

|---|---|---|

| Identification with the protagonist | 1 (not at all)–5 (very much) | 0.93 |

| ||

| Counterarguing | 1 (strongly disagree)–7 (strongly agree) | 0.73 |

| ||

| Reactance | 1 (strongly disagree)–7 (strongly agree) | 0.83 |

| ||

| Cognitive elaboration | 1 (strongly disagree)–7 (strongly agree) | 0.85 |

| ||

| Perceived effectiveness of the message | 1 (strongly disagree)–7 (strongly agree) | 0.86 |

| ||

| Intention to quit smoking | 1 (strongly disagree)–7 (strongly agree) | 0.84 |

| ||

| Self-efficacy | 1 (strongly disagree)–7 (strongly agree) | 0.87 |

| ||

| Response efficacy | 1 (strongly disagree)–7 (strongly agree) | 0.85 |

|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Identification | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 Counterarguing | −0.29 *** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 Reactance | −0.21 *** | 0.43 *** | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 Cognitive elaboration | 0.71 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.15 *** | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 Perceived message effectiveness | 0.77 *** | −0.35 *** | −0.24 *** | 0.74 *** | - | - | - | - |

| 6 Intention to quit smoking | 0.54 *** | −0.17 *** | −0.12 ** | 0.59 *** | 0.60 *** | - | - | - |

| 7 Self-efficacy | 0.11 ** | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.15 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.36 *** | - | - |

| 8 Response efficacy | 0.41 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.22 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.21 *** | - |

| Mean | 3.60 | 2.72 | 2.64 | 5.33 | 5.27 | 4.72 | 4.78 | 5.91 |

| Standard deviation | 0.84 | 1.26 | 1.37 | 1.26 | 1.14 | 1.46 | 1.25 | 0.97 |

| (a) Dependent variable: perceived message effectiveness | |||

| Specific indirect effects (mediators) | Effect | Boot SE | Boot 95% CI |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Perceived message effectiveness | 0.1154 | 0.0474 | [0.0271, 0.2119] |

| Narrative voice → Counterarguing → Perceived message effectiveness | −0.0028 | 0.0101 | [−0.0241, 0.0169] |

| Narrative voice → Reactance → Perceived message effectiveness | −0.0018 | 0.0058 | [−0.0147, 0.0092] |

| Narrative voice → Cognitive elaboration → Perceived message effectiveness | −0.0384 | 0.0275 | [−0.0925, 0.0168] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Counterarguing → Perceived message effectiveness (H2a) | 0.0074 | 0.0042 | [0.0009, 0.0171] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Reactance → Perceived message effectiveness (H2b) | 0.0028 | 0.0023 | [−0.0002, 0.0085] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Cognitive elaboration → Perceived message effectiveness (H2c) | 0.0725 | 0.0300 | [0.0167, 0.1348] |

| (b) Dependent variable: intention to quit smoking | |||

| Specific indirect effects (mediators) | Effect | Boot SE | Boot 95% CI |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Intention to quit smoking | 0.0796 | 0.0376 | [0.0153, 0.1617] |

| Narrative voice → Counterarguing → Intention to quit smoking | 0.0002 | 0.0053 | [−0.0102, 0.0126] |

| Narrative voice → Reactance → Intention to quit smoking | −0.0007 | 0.0060 | [−0.0143, 0.0120] |

| Narrative voice → Cognitive elaboration → Intention to quit smoking | −0.0520 | 0.0390 | [−0.1334, 0.0209] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Counterarguing → Intention to quit smoking (H2a) | −0.0006 | 0.0044 | [−0.0095, 0.0087] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Reactance → Intention to quit smoking (H2b) | 0.0010 | 0.0034 | [−0.0056, 0.0085] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Cognitive elaboration → Intention to quit smoking (H2c) | 0.0082 | 0.0414 | [0.0230, 0.1849] |

| (c) Dependent variable: self-efficacy | |||

| Specific indirect effects (mediators) | Effect | Boot SE | Boot 95% CI |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Self-efficacy | 0.0079 | 0.0226 | [−0.0374, 0.0557] |

| Narrative voice → Counterarguing → Self-efficacy | 0.0024 | 0.0097 | [−0.0161, 0.0245] |

| Narrative voice → Reactance → Self-efficacy | 0.0005 | 0.0063 | [−0.0124, 0.0147] |

| Narrative voice → Cognitive elaboration → Self-efficacy | −0.0165 | 0.0156 | [−0.0536, 0.0062] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Counterarguing → Self-efficacy (H2a) | −0.0063 | 0.0056 | [−0.0200, 0.0019] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Reactance → Self-efficacy (H2b) | −0.0008 | 0.0035 | [−0.0081, 0.0065] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Cognitive elaboration → Self-efficacy (H2c) | 0.0032 | 0.0203 | [0.0004, 0.0776] |

| (d) Dependent variable: response efficacy | |||

| Specific indirect effects (mediators) | Effect | Boot SE | Boot 95% CI |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Response efficacy | 0.0317 | 0.0187 | [0.0023, 0.0740] |

| Narrative voice → Counterarguing → Response efficacy | −0.0043 | 0.0148 | [−0.0330, 0.0268] |

| Narrative voice → Reactance → Response efficacy | −0.0024 | 0.0077 | [−0.0205, 0.0117] |

| Narrative voice → Cognitive elaboration → Response efficacy | −0.0232 | 0.0175 | [−0.0599, 0.0098] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Counterarguing → Response efficacy (H2a) | 0.0114 | 0.0061 | [0.0020, 0.0025] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Reactance → Response efficacy (H2b) | 0.0036 | 0.0028 | [−0.0002, 0.0106] |

| Narrative voice → Identification → Cognitive elaboration → Response efficacy (H2c) | 0.0439 | 0.0225 | [0.0080, 0.0954] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Igartua, J.-J.; Rodríguez-Contreras, L. Narrative Voice Matters! Improving Smoking Prevention with Testimonial Messages through Identification and Cognitive Processes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197281

Igartua J-J, Rodríguez-Contreras L. Narrative Voice Matters! Improving Smoking Prevention with Testimonial Messages through Identification and Cognitive Processes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197281

Chicago/Turabian StyleIgartua, Juan-José, and Laura Rodríguez-Contreras. 2020. "Narrative Voice Matters! Improving Smoking Prevention with Testimonial Messages through Identification and Cognitive Processes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 19: 7281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197281

APA StyleIgartua, J.-J., & Rodríguez-Contreras, L. (2020). Narrative Voice Matters! Improving Smoking Prevention with Testimonial Messages through Identification and Cognitive Processes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197281