Abstract

Many schools in low-income countries have inadequate access to water facilities, sanitation and hygiene promotion. A systematic review of literature was carried out that aimed to identify and analyse the impact of water, sanitation and hygiene interventions (WASH) in schools in low-income countries. Published peer reviewed literature was systematically screened during March to June 2018 using the databases PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, Science Direct, and Google Scholar. There were no publication date restrictions. Thirty-eight peer reviewed papers were identified that met the inclusion criteria. The papers were analysed in groups, based on four categories of reported outcomes: (i) reduction of diarrhoeal disease and other hygiene-related diseases in school students; (ii) improved WASH knowledge, attitudes and hygiene behaviours among students; (iii) reduced disease burden and improved hygiene behaviours in students’ households and communities; (iv) improved student enrolment and attendance. The typically unmeasured and unreported ‘output’ and/or ‘exposure’ of program fidelity and adherence was also examined. Several studies provide evidence of positive disease-related outcomes among students, yet other assessments did not find statistically significant differences in health or indicated that outcomes are dependent on the nature and context of interventions. Thirteen studies provide evidence of changes in WASH knowledge, attitudes and behaviours, such as hand-washing with soap. Further research is required to understand whether and how school-based WASH interventions might improve hygiene habits and health among wider family and community members. Evidence of the impact of school-based WASH programs in reducing student absence from school was mixed. Ensuring access to safe and sufficient water and sanitation and hygiene promotion in schools has great potential to improve health and education and to contribute to inclusion and equity, yet delivering school-based WASH intervention does not guarantee good outcomes. While further rigorous research will be of value, political will and effective interventions with high program fidelity are also key.

1. Introduction

Schools with adequate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities have: a reliable water system that provides safe and sufficient water, especially for hand-washing and drinking; sufficient number of toilets for students and teachers that are private, safe, clean, and culturally and gender appropriate; water-use and hand-washing facilities, including some close to toilets; and sustained hygiene promotion [1]. Facilities should cater to all, including small children, girls of menstruation age, and children with disabilities. WASH conditions in schools in many low-income countries, however, are inadequate with associated detrimental effects on health and school attendance [2]. An evaluation by UNICEF [3] found that in schools in low-income countries, only 51% of schools had access to adequate water sources and only 45% had adequate sanitation.

Globally, school-based WASH interventions variously aim to: (i) reduce the incidence of diarrhoea and other hygiene related diseases; (ii) improve school enrolment, school performance, and attendance; and (iii) influence hygiene practices of parents and siblings whereby children act as agents of change in their households and communities. However, evidence assessing the impact of school-based WASH interventions has been mixed. Two previous reviews of studies of the impact of school-based WASH interventions have shown mixed results on outcome measures such as knowledge, attitudes and practices, school attendance, and health [2,4]. The review by Jasper et al. [2] had a global focus and most included studies (n = 41) were from high- and middle-income countries (e.g., United States, United Kingdom); Joshi and Amadi [4] also had a global focus including studies from North America and Europe and their review was confined to studies (n = 15) published between 2009–2012.

The objective of this review is to analyse published peer-reviewed journal articles that focus on WASH in schools in low-income countries. The review focuses on intervention-based studies and key outcome measures including: health among school students (e.g., diarrhoeal disease and other hygiene-related diseases); WASH knowledge, attitudes and hygiene behaviours among students; changes in disease burden and hygiene behaviours in students’ households and communities; changes in student enrolment and school attendance. The review also considers the under-reported indicator of intervention fidelity. The review highlights gaps in knowledge and potential future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

Published peer reviewed journal articles were included that examined the impacts of school-based WASH intervention in low-income countries. WASH interventions included: hand-washing initiatives (e.g., water, wash basins, soap, drying devices); drinking water initiatives; improved sanitation (improved toilets, facilities for menstruation); and hygiene behaviour initiatives (e.g., handwashing with soap, hygiene education). Reported outcomes include: educational outcomes (i.e., school attendance, school dropout); hygiene behaviours, knowledge and attitudes; and health (i.e., WASH-related illness). Intervention fidelity—adherence to intervention delivery standards—was also reported in several studies (either as an ‘exposure’ or ‘outcome’). Article inclusion was restricted to those with a focus on low-income countries, defined as countries with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita (calculated using the World Bank Atlas method) of 1005 USD or less in 2016. The review was restricted to articles for which the abstract and article was available in English language.

Descriptive studies of school-based WASH conditions, without evaluative focus on intervention impacts, were excluded [5,6]. Morgan et al. [5], for example conducted a cross-sectional survey of 2270 WASH intervention beneficiary schools in Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia and found that fewer than 23% of rural schools met World Health Organization recommended student-to-latrine ratios. While descriptive studies provide important insight into the context and challenges for WASH in schools, they are not the focus here.

The following electronic databases were searched during March to June 2018: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, Science Direct, and Google Scholar. The search was based on the keywords: WASH or water or sanitation or soap or hygiene or “hand hygiene” or “hand wash*” AND school or attendance AND “low income” or “developing country” or “developing nations”. For example, in Embase the following search terms were deployed: (WASH OR water OR hygiene OR “hand hygiene” OR “hand wash*” OR sanitation OR Soap* OR “child* health”) AND (school OR attendance) AND (“low income country” OR “developing country”). References of included articles were systematically searched for relevant documents. There were no publication date restrictions.

3. Results

3.1. Systematic Review and Yielded Studies

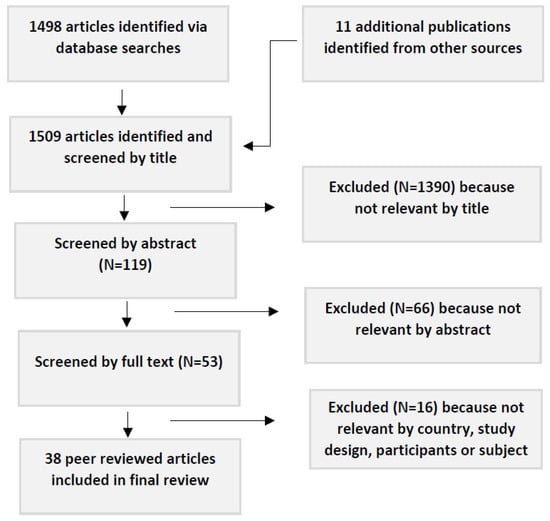

The initial search terms identified 1498 publications; 11 additional articles were identified from other sources. The secondary screening—based on the title—identified 119 articles with a potential focus on WASH in schools in low-income countries. Thirty eight of these articles met the inclusion criteria, following screening by abstract and then full text. Bibliographies of these references identified no additional articles (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing procedure for article selection.

For each article, a summary of key information was tabled: i.e., country of study, study design, study population (number of schools, children, and/or their age), exposure/intervention, outcome measure, key findings. As the studies use diverse methods and outcome measures no attempt was made to weight the value of findings according to study quality, or to conduct meta-analysis of study findings. Of the 38 articles: 47% reported the intervention impact on diarrhoeal disease and other hygiene-related diseases in school students; 34% reported changes in WASH knowledge, attitudes and hygiene behaviours among students; 16% reported impact on disease burden and hygiene behaviours in students’ households and communities; 32% reported changes in student enrolment and school attendance; and 11% reported on intervention fidelity (see Table 1). Twelve studies reported outcome measures across more than one category [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Outcome measures reported in included articles (n = 38).

Countries of focus included Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, China, Colombia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Mali, Niger, Nepal and Tanzania. Study methods included cross-sectional survey, non-randomized trial, cluster-randomized trial, and before and after intervention studies. Study design is identified in Table 2.

Table 2.

Published evaluations of WASH in schools in low-income countries.

3.2. Reduced Diarrhoea and other WASH-Related Diseases in School Students

Despite the biological plausibility that improvements in school WASH conditions will be beneficial for pupil health, results from school-based WASH evaluations have been mixed. There is evidence that WASH in Schools programs have a positive impact on child health, including reductions in diarrhoeal disease and other hygiene-related diseases. Migele et al. [28] examined the impact of a simple school-based water treatment and hand-washing intervention in a boarding school in Kenya: i.e., clay pots modified with narrow mouths and ceramic lids, taps for drinking water, plastic tanks with taps for hand washing, WaterGuard (i.e., sodium hypochlorite solution) for drinking water, and soap for hand washing. Before-and-after rates of diarrhoea disease (with no control schools) indicated a more than 50% reduction in recorded cases of diarrhoea among students. In their evaluation of WinS interventions in Mali, Trinies et al. [18] found that, as compared with control schools, there were lower odds of students in beneficiary schools reporting diarrhea (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.60–0.85) or respiratory infection symptoms (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.65–0.86) in the past week. And a study in rural Kenya [15] found that school-based water treatment and hygiene programs resulted in a decrease in rates of acute respiratory illness, although no decrease in acute diarrhea was observed. Improving school-based WASH can also reduce other hygiene-related diseases, such as soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infection [7,21,22]. For example, Bieri et al. [7] found that among Chinese school-children, the incidence of infection with STHs was 50% lower in the intervention group that received a STH education package than in the control group (4.1% vs. 8.4%, p < 0.001). And in Mali, Freeman et al. [22] found that provision of school-based sanitation, water quality, and hygiene improvements reduced reinfection of some STHs after school-based deworming, but the magnitude of the effects were helminth species-specific.

Results, however, are not uniformly clear or positive. In an evaluation of a hand-washing promotion program in Chinese primary schools, rates of diarrhoea were too low in both intervention and control groups to identify attributable differences in prevalence [35]. Some studies indicated that basic interventions that include hygiene promotion, water treatment, and behaviour change did not reduce rates of diarrhoeal disease [11,15]. In a multi-country study, Dujister et al. [20] found that the STH prevalence at baseline and at follow-up did not significantly differ between intervention schools (that provided deworming and improved handwashing) and control schools. And a study by Greene et al. [25] conducted in schools in western Kenya found that hygiene promotion and water treatment did not reduce risk of Escherichia coli presence on pupils’ hands; further, the addition of new latrines to intervention schools significantly increased E. coli presence among girls (RR = 2.63, 95% CI 1.29–5.34) which they attributed to an absence of sufficient hygiene behaviour change, and lack of soap, water, and anal cleansing materials. It is important to note, however, that presence of E. coli on hands is a variable that is difficult to interpret in terms of disease risk and outcomes.

Context is important. For example, Freeman et al. [11] found that local water availability affected the impact of school-based WASH interventions on diarrhoea rates among pupils. Pupils attending ‘water-scarce’ schools (in which there was no dry-season water source within 1km) that received WASH intervention (including water-supply improvement, hygiene promotion and water treatment, and sanitation improvements) reported a reduction in diarrhoea incidence and days of illness; they reported a 56% difference in the risk of diarrhoea for pupils attending intervention vs. control schools in water-scarce sites (adjusted risk ratio (aRR) 0.34, 95% CI 0.17–0.64). No statistically significant effect was detected for any intervention in ‘water-available schools’, nor for ‘water-scarce’ schools that received only hygiene promotion and water treatment. Similarly, Garn et al. [44] found that in water-scarce schools in Kenya, there was reduced prevalence of diarrhea among pupils attending schools that adhered to two or three intervention components (prevalence ratio 0.28, 95% CI 0.10–0.75), compared with schools that adhered to zero components or one. It was not clear why results were different in water-scarce versus water-available schools, but it is possible that WASH interventions in water-scarce schools were more comprehensive.

There is widespread recognition that WASH infrastructure and resources are important foundations for hygiene behaviour change and reduced risk of WASH-related diseases. There is evidence, however, that latrine construction, without other supporting water and hygiene-related interventions, is not effective at reducing diarrhoeal disease [11, 20). Possible explanations are that without broader hygiene promotion and latrine maintenance efforts, construction of latrines alone may not result in their use or (conversely) latrines may increase exposure to faecal pathogens if they are poorly maintained, used incorrectly, or if hygiene resources are not available during and after use [11,36]. The health benefits of improved WASH infrastructure and resources in schools may depend on consistent availability of soap and water for handwashing and on conditions of the latrines, not only pupil to latrine ratios [26].

3.3. Improved WASH Knowledge, Attitudes and Hygiene Behaviours

Thirteen studies measured WASH knowledge, attitudes and hygiene behaviours among students (see Table 1); all found evidence of improved knowledge, attitudes and behaviours associated with WinS program. Dreibelbis et al. [29] report findings of an intervention that aimed to improve hand-washing after toilet use among students in two primary schools in rural Bangladesh. Dedicated locations for hand-washing were constructed in both schools. Two nudges were implemented: first, connecting latrines to hand-washing stations via brightly painted paved pathways; second, painting footprints on pathways guiding students to the handwashing stations and handprints on stations. Soap was provided and schools were asked to make soap available and refill water storage containers each day. At baseline, hand-washing with soap (HWWS) was low (4%); this increased to 68% the day after nudges were completed and 74% at both 2 weeks and 6 weeks post intervention. The high rates of observed handwashing post-intervention suggest that nudges can have sustained effects on hygiene behaviours. A related cluster-randomized trial in schools Bangladesh [30] demonstrated comparable increases in rates of handwashing with soap five months after intervention both for a nudge intervention (paved path with painted shoe-prints and arrows connecting latrines to the handwashing facility, painted handwashing station with handprints and a dedicated location for soap) and high intensity hygiene education initiatives. La Con et al. [31] found that installation of water and handwashing stations in schools in rural Kenya, coupled with WASH education, enabled student handwashing with stations located closer to latrines (<10 m) used much more frequently. One randomized cluster trial in rural Kenya [17] examined the impact of provision of regular soap and latrine cleaning materials and hygiene education; pupil hand-washing rates following toileting were observed to be 32–38% in intervention schools compared to 2% of students in control schools. Another randomized cluster trial in urban Nairobi, Kenya, examined the impact of teacher hygiene training and provision of regular alcohol-based hand sanitizer or liquid soap; pupil hand-washing rates following toileting were observed to be 82% at schools with sanitizer, 38% at schools with soap, and 37% at control schools [16].

3.4. Reduced Disease Burden and Improved Hygiene Practices in Households and Communities

In addition to limiting pathogen transmission in the public domain—such as at schools—school-level WASH interventions may also reduce community disease burden and improve hygiene knowledge. One study in Kenya found that in water-scarce areas, school-based WASH interventions that included improvement in water supply reduced diarrhoea among school students’ siblings under the age of five who were not attending school [33]. The authors suggest this could be due to diffusion of improved hygiene practices and behaviours in both home environments and community, or interruption of pathogen transmission in school contexts thereby reducing exposure and transmission in domestic environments. Another study in Kenya documented transfer of knowledge from school students to their parents, identifying increased parental awareness and household use of water treatment with flocculent disinfectant following student hygiene education and provision of water treatment products to students; improved household water treatment practices were sustained over one year [32]. A study of a school-based WASH intervention in Kenya documented the transfer of knowledge about point-of-use water treatment practices and increased utilisation of WaterGuard in student’s households as indicated by having chlorine residuals in stored water; parents also reported improved hand-washing and 38% of parents demonstrated correct hand-washing technique [14]. However, based on their study in Burkina Faso, Erismann et al. [10] warn that although children can promote health messages to family members, effective behaviour changes among family members is more difficult to achieve due to the challenge of changing practices and the broader constraints that limit improved behaviours (e.g., water scarcity).

3.5. Improved Student Enrolment and Attendance

In this review, twelve studies in low-income countries were identified that examined the impact of school-based WASH programs on student absence and enrolment. Improved school WASH conditions may reduce student absence by providing services (including, importantly, for girls who are menstruating) and by reducing illness transmission [45]. There is some evidence that improved hand-washing with soap at school can reduce illness in school-aged children thereby reducing absence from school [11,14,15,18,21,35,41].

Interventions that deliver hand-washing promotion and point-of-use water treatment have reported reductions in student absence of between 21% [32] and 61% [38] with one study specifically identifying reduced absence among girls (i.e., 58% reduction in the odds of absence for girls) [21]. A school-based water and hygiene intervention in public primary schools in Kenya found a decrease in student absence of 35% relative to baseline as compared to a 5% increase in neighbouring schools [14]. Talaat et al. [41] identified a 21% reduction in school absence from all illnesses (e.g., diarrhea, conjunctivitis, influenza) as a result of an intensive hand-washing campaign in Egypt; absences caused by influenza-like illness, diarrhea, conjunctivitis, and laboratory-confirmed influenza were reduced by 40%, 33%, 67%, and 50%, respectively. A small pilot study in Ghana entailed provision of sanitary pads and puberty education to adolescent girls in both intervention and control schools, with the intervention found to significantly improve attendance [39]. Evaluation of a comprehensive WASH intervention in schools in Bangladesh—using a non-experimental survey design—reported a 9–12% reduction in school absence among girls (varying between schools) [42]. A trial of school-based WASH interventions in Kenya found that cleanliness of latrines was strongly correlated with recent student absence [37]. And a study of hand-washing intervention in Chinese primary schools found that the expanded intervention (standard government education plus hand-washing program, soap for sinks, and peer hygiene monitors) reported 42% fewer absence episodes and 54% fewer days of absence, and the standard intervention (handwashing program) reported 44% fewer absence episodes and 27% fewer days of absence [35].

Some intervention studies, however, found no evidence of impact on attendance. A study in the Chitwan region of Nepal [40] trialled the use of menstrual cups (a silicone cup used internally for menstrual flow management) with a small sample of schoolgirls. The study found the technology had no impact on school attendance or school test outcomes; the authors suggest this is because the technology assisted only with management of blood, and did not reduce cramps which were reported as the primary reason for non-attendance. However, the study had several limitations including self-reporting of menstrual cup usage, and lack of consideration of existing water and sanitation facilities in schools. And a trial in Kenya to assess the impact of a scalable, low-cost, school-level latrine cleaning intervention on pupil absence did not find a reduction in absenteeism; the authors hypothesised that the additional impact of cleaning may not have been sufficient to reduce absence beyond reductions attributable to the original WASH intervention [36].

3.6. Intervention Fidelity

Effectiveness of interventions is associated with the typically unmeasured and unreported ‘output’ and/or ‘exposure’ of intervention delivery including program fidelity and adherence. Three studies reported on intervention fidelity but did not draw conclusions as to its effect on measured outcomes. Chard and Freeman [9] report on a WASH intervention in Laotian primary schools and found inadequate school-level adherence to project outputs (e.g., soap provision, water availability, hygiene promotion activities); the differential impact of school-level intervention fidelity on measured hygiene behaviours (e.g., toilet use and daily hygiene activities) was not reported. Alexander et al. [43] assessed whether student and parental monitoring and additional funding for repairs and maintenance affected the fidelity and effectiveness of school-based WASH service provision in 70 schools in Western Kenya; no clear results emerged. Hetherington et al. [12] reported on an initiative in Tanzania that aimed to engage high-school students and the wider community in improving sanitation and hygiene. While they noted challenges of intervention adherence and fidelity—including timing of activities, communication between schools and local coordination, and inadequate supplies and allowances to support activities—the impact of these challenges on the primary outcome measures (i.e., hygiene knowledge, attitudes, behaviours) was not assessed. Garn et al. [44] provide rare evidence of the impact of intervention adherence and found that among water-scarce schools in Kenya improved adherence resulted in reduced prevalence of diarrhoea among pupils.

4. Discussion

Access to WASH facilities and hygiene behaviour change education in schools contribute to inclusion, dignity, and equity. From a human rights perspective, WASH in schools is considered essential. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) implicitly highlight the need to expand WASH beyond household settings, in the effort to achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water, sanitation and hygiene for all. The SDGs explicitly refer to WASH in Schools in Target 4.a via the indicator of the “proportion of schools with access to: (e) basic drinking water; (f) single-sex basic sanitation; and (g) basic handwashing facilities” [46]. However, the aim is to not only provide adequate ratios, but to ensure positive outcomes across diverse measures including diarrhoeal disease and other WASH-related diseases, hygiene behaviour and school attendance.

There is biological plausibility supporting the health and educational benefits of providing WASH in schools, as well as rights-based arguments for WASH in Schools. The studies in this review indicate that school-based WASH interventions can protect against diarrhoea and other WASH-related illness such as soil-transmitted helminths and acute respiratory infections, increase WASH-related knowledge and practices, and improve educational outcomes including reduced absence.

Fourteen (78%) of the 18 publications that reported disease-related outcomes found reductions in diarrhoeal disease and other hygiene-related diseases, such as respiratory illness and soil-transmitted helminths, among students at intervention schools (c.f. [7,18,21,28]). Of these publications reporting positive health outcomes, however, more than half also reported that there were no statistically significant reductions for some disease-related outcomes: e.g., intestinal parasitic infections prevalence, but not undernutrition, was found to decrease [10]. Four of the 18 publications reported no evidence of reduced risk for the primary disease-related outcome measures, including soil-transmitted helminths and E. coli on pupils’ hands [17,20,25,26].

All of the 13 publications that examined changes in WASH knowledge, attitudes and hygiene behaviours reported evidence of positive change among students in intervention schools including hand-washing with soap or sanitizer [8,16,29,30,31], improved knowledge of WASH-related diseases, and improved hygiene habits [7,13].

Six studied examined whether WASH interventions in schools led to reductions in the family and community burden of WASH-related diseases and improved WASH knowledge at the family and community level. They provide very limited evidence of improvements in WASH-related knowledge and behavior and reduced WASH-related disease among family [14,32,33]. Further research is required to understand whether and how school-based WASH interventions can improve hygiene habits and disease-related outcomes among wider family and community members [29].

Demographic factors are key predictors of student absence from school, including gender and socio-economic status [37]. Nonetheless, WASH-related illnesses have been estimated to result in hundreds of millions of days of school absence [47]. Twelve publications examined the impact of school-based WASH interventions on student absence in low-income countries and the findings were mixed. There is some evidence that improved hand-washing with soap at school, provision of sanitary pads, maintained and clean latrines can reduce absence in school-aged children (c.f. [11,18,35,37,42]), but a few studies found that school-based WASH interventions had no impact on student attendance [36,40].

Importantly, intervention effectiveness is affected by intervention delivery, including program fidelity and adherence. Freeman et al. [11] warn that suboptimal intervention fidelity often means that researchers evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in real-world settings, not ideal ‘best practice’ for WASH environments. Yet, while various publications mention the challenges of fidelity and adherence in school-based WASH interventions, their impact on outcomes is rarely assessed; only one study in schools in Kenya specifically demonstrated that improved intervention adherence resulted in reduced prevalence of diarrhoea among pupils [44]. Studies such as these highlight that ensuring consistent and effective delivery of WASH interventions in low-resources contexts, including school-based interventions, remains a challenge.

So, there is no universal blueprint and effects are not consistent between studies as both context and intervention type matter. For example, the effectiveness of an intervention in reducing diarrhoeal disease may be based on background rates of disease, pathogen-pathways in specific environments, student populations, baseline WASH conditions such as water availability, and broader social, political and economic contexts [11,44]. Several publications emphasise that combined interventions that include multiple components—for example, latrine construction, hygiene promotion, latrine maintenance, and sustained provision of resources such as soap and water for handwashing—are more effective at reducing WASH-related diseases than single interventions such as construction of latrines [11,21,36].

Evaluative research of WASH in Schools encounters challenges which influence results and their interpretations, including: restrictions in randomisation, the potential of crossover effects, and circumstances beyond the researchers’ control such as the interference of other health programmes. The definition of illness outcomes such as “diarrhea” are not uniform across studies which makes inter-study comparison difficult. And, importantly, evaluations of WASH interventions in low-resource settings often measure outcomes—such as diarrheal disease—via self-report, an approach prone to recall and social desirability biases, subjective interpretations of the definition of “diarrhea”, and imprecise measurements of incidence [9]. It is notable that of the 18 studies in this review that report disease-related outcomes, ten (56%) included objective rather than self-reported measures of disease and infection: for example, fecal samples were examined for soil-transmitted helminths, intestinal protozoa and other parasites [7,8,10,11,20,22,24,26], blood samples were collected to measure blood hemoglobin concentration [26], and hand-rinse samples were analysed for E. coli [17,25].

The theory of change embedded in project design also influences the nature of an intervention and its delivery. In their evaluation of Project SHINE (Sanitation and Hygiene INnovation in Education) in Tanzania, for example, Hetherington et al. [12] highlighted the value of strategies that enable communities to develop locally sustainable approaches to improving their health, in contrast to other models (e.g., Community Led Total Sanitation) which incorporate shaming and disgust techniques to promote behaviour change. Theories of change must be considered to fully understand effectiveness, or lack thereof, rather than reducing interventions to processual elements of exposure and outcome.

Notably, several studies have examined the onset and management of menses in low-income countries, with a specific focus on the challenges of menstrual hygiene management (MHM) in school environments (e.g., negative attitudes, limited health and sexuality information, inadequate facilities and privacy) (c.f. [48,49,50]). However, these studies are qualitative and/or descriptive; very few intervention studies include a focus on menstrual hygiene management in schools in low-income countries [39,40,43].

This review contributes to understanding of the impact of school-based WASH interventions beyond the two existing reviews of school-based WASH by Jasper et al. [2] and Joshi and Amadi [4]. First, these two existing reviews have no restrictions on study location and more than two thirds of the 41 articles in the review by Jasper et al. [2] report findings of research conducted in high-income countries (e.g., United Kingdom, United States, Germany) and almost one third of the 15 articles in the review by Joshi and Amadi [4] were conducted in developed countries; this review has an explicit focus on low-income countries where there is the greatest need for improved access to safe drinking water, improved sanitation, handwashing facilities and hygiene education [47]. Second, these reviews necessarily include only publications available up to 2012: the Jasper et al. review [2] had no time restriction on the date of publication and the search was conducted in 2010 and updated in 2012; the Joshi and Amadi [4] review was restricted to studies published between 2009 and 2012 and the search was conducted in 2013. In this review, however, twenty-five of the 38 studies included were published after 2012. The contribution of this review, then, is its explicit focus on low-income countries and its inclusion of the substantial body of relevant research published in the last several years.

5. Conclusions

It is important to better understand disease-related and educational outcomes of school-based WASH interventions. This can help governments and donors allocate resources to school-based WASH interventions and enable agencies to design and implement effective interventions [11]. Intervention studies of WASH in schools in low-income settings are both expensive and challenging. There is, arguably, no need for additional large-scale epidemiological studies on the impact of WinS on diarrhoea among students as numerous studies have found evidence of positive outcomes related to diarrhoeal disease [11]. There is, however, still a need to better understand the differential impacts of different types of WinS programmes for broader health and educational outcomes, the extent to which students operate as change agents in wider communities, the role of independent variables including gender and socio-economic status, and the effect of targeted initiatives on menstrual hygiene management and girls’ school attendance. Further, there is value in conducting process evaluations that identify opportunities and challenges within program implementation, including theories of change and intervention fidelity. Political will and financing and effective delivery of interventions will be required to ensure universal access to WASH in Schools including in low-income countries.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the librarian who assisted with the search strategy associated with this publication, David Honeybone at The University of Melbourne.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, J.; Bartram, J.; Chartier, Y.; Sims, J. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Standards for Schools in Low-cost Settings. World Health Organization/UNICEF. 2009. Available online: http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/wash_standards_school.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2016).

- Jasper, C.; Thanh-Tam, L.; Bartram, J. Water and Sanitation in Schools: A Systematic Review of the Health and Educational Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public 2012, 9, 2772–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Raising Even More Clean Hands; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A.; Amadi, C. Impact of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Interventions on Improving Health Outcomes among School Children. J. Environ. Public Health 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, C.; Bowling, M.; Bartram, J.; Kayser, G.L. Water, sanitation, and hygiene in schools: Status and implications of low coverage in Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zambia. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Quintero, C.; Freeman, P.; Neumark, Y. Hand washing among school children in Bogota, Colombia. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieri, F.A.; Gray, D.J.; Williams, G.M.; Raso, G.; Li, Y.; Yuan, L.; He, Y.; Li, R.S.; Guo, F.Y.; Li, S.M. Health-Education Package to Prevent Worm Infections in Chinese Schoolchildren. NEJM 2013, 368, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boubacar Maïnassara, H.; Tohon, Z. Assessing the Health Impact of the following Measures in Schools in Maradi (Niger): Construction of Latrines, Clean Water Supply, Establishment of Hand Washing Stations, and Health Education. J. Parasitol. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chard, A.N.; Freeman, M.C. Design, Intervention Fidelity, and Behavioral Outcomes of a School-Based Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Cluster-Randomized Trial in Laos. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erismann, S.; Diagbouga, S.; Schindler, C.; Odermatt, P.; Knoblauch, A.M.; Gerold, J.; Leuenberger, A.; Shrestha, A.; Tarnagda, G.; Utzinger, J.; et al. School Children’s Intestinal Parasite and Nutritional Status One Year after Complementary School Garden, Nutrition, Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Interventions in Burkina Faso. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, M.C.; Clasen, T.; Dreibelbis, R.; Saboori, S.; Greene, L.E.; Brumback, B.; Muga, R.; Rheingans, R. The impact of a school-based water supply and treatment, hygiene, and sanitation programme on pupil diarrhoea: A cluster-randomized trial. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, E.; Eggers, M.; Wamoyi, J.; Hatfield, J.; Manyama, M.; Kutz, S.; Bastien, S. Participatory science and innovation for improved sanitation and hygiene: Process and outcome evaluation of project SHINE, a school-based intervention in Rural Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karon, A.J.; Cronin, A.; Cronk, R.; Henrdwan, R. Improving water, sanitation, and hygiene in schools in Indonesia: A cross-sectional assessment on sustaining infrastructural and behavioral interventions. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, C.E.; Freeman, M.C.; Ravani, M.; Migele, J. The impact of a school-based safe water and hygiene programme on knowledge and practices of students and their parents: Nyanza Province, western Kenya, 2006. Epidemiol. Infect. 2008, 136, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.K.; Harris, J.R.; Juliao, P.; Nygren, B.; Were, V.; Kola, S.; Sadumah, I.; Faith, S.H.; Otieno, R.; Obure, A.; et al. Impact of a hygiene curriculum and the installation of simple hand-washing and drinking water stations in rural Kenyan primary schools on student health and hygiene practices. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 87, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, A.J.; Davis, J.; Blum, A.G.; Scalmanini, J.; Oyier, B.; Okoth, G.; Breiman, R.F.; Ram, P.K. Access to waterless hand sanitizer improves student hand hygiene behavior in primary schools in Nairobi, Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 89, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saboori, S.; Greene, L.E.; Moe, C.L.; Freeman, M.C.; Caruso, B.A.; Akoko, D.; Rheingans, R.D. Impact of regular soap provision to primary schools on hand washing and E. coli hand contamination among pupils in Nyanza Province, Kenya: A cluster-randomized trial. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 89, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinies, V.; Garn, J.; Chang, H.; Freeman, M. The Impact of a School-Based Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Program on Absenteeism, Diarrhea, and Respiratory Infection: A Matched–Control Trial in Mali. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 1418–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chard, A.N.; Trinies, V.; Moss, D.M.; Chang, H.H.; Doumbia, S.; Lammie, P.J.; Freeman, M.C. The impact of school water, sanitation, and hygiene improvements on infectious disease using serum antibody detection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dujister, D.; Monse, B.; Dimaisip-Nabuab, J.; Djuharnoko, P.; Heinrich-Weltzien, R.; Hobdell, M.; Kromeyer-Hauschild, K.; Kunthearith, Y.; Mijares-Majini, M.C.; Siegmund, N. ‘Fit for school’—A school-based water, sanitation and hygiene programme to improve child health. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 302. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M.; Greene, L.E.; Dreibelbis, R.; Saboori, S.; Muga, R.; Brumback, B.; Rheingans, R. Assessing the impact of a schoolbased water treatment, hygiene, and sanitation program on pupil absence in Nyanza Province, Kenya: A cluster randomized trial. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2012, 17, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Freeman, M.C.; Clasen, T.; Brooker, S.; Akoko, D.O.; Rheingans, R. The Impact of a School-Based Hygiene, Water Quality and Sanitation Intervention on Soil-Transmitted Helminth Reinfection: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 89, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, M.C.; Chard, A.N.; Nikolay, B.; Garn, J.V.; Okoyo, C.; Kihara, J.; Njenga, S.M.; Pullan, R.L.; Brooker, S.J.; Mwandawiro, C.S. Associations between school- and household-level water, sanitation and hygiene conditions and soil-transmitted helminth infection among Kenyan school children. Parasit. Vect. 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garn, J.; Brumback, B.; Drews-Botsch, C.; Lash, T.; Kramer, M.; Freeman, M. Estimating the Effect of School Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Improvements on Pupil Health Outcomes. Epidemiology 2016, 27, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, L.E.; Freeman, M.C.; Akoko, D.; Saboori, S.; Moe, C.; Rheingans, R. Impact of a school-based hygiene promotion and sanitation intervention on pupil hand contamination in Western Kenya: A cluster randomized trial. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 87, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimes, J.; Tadesse, G.; Gardiner, I.A.; Yard, E.; Wuletaw, Y.; Templeton, M.R.; Harrison, W.E.; Drake, L.J. Sanitation, hookworm, anemia, stunting, and wasting in primary school children in southern Ethiopia: Baseline results from a study in 30 schools. PLoS Negl. Trop. D 2017, 11, e0005948. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, J.S. Diarrhea and school toilet hygiene in Cali, Colombia. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1978, 107, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migele, J.; Ombeki, S.; Ayalo, M.; Biggerstaff, M.; Quick, R. Diarrhea prevention in a Kenyan school through the use of a simple safe water and hygiene intervention. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 76, 351–353. [Google Scholar]

- Dreibelbis, R.; Kroeger, A.; Hossain, K.; Venkatesh, M.; Ram, P. Behavior Change without Behavior Change Communication: Nudging Handwashing among Primary School Students in Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, E.; Hossain, M.K.; Uddin, S.; Venkatesh, M.; Ram, P.K.; Dreibelbis, R. Comparing the behavioural impact of a nudge-based handwashing intervention to high-intensity hygiene education: A cluster-randomised trial in rural Bangladesh. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2018, 23, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Con, G.; Schilling, K.; Harris, J.; Person, B.; Owuor, M.; Ogange, L.; Faith, S.; Quick, R. Evaluation of Student Handwashing Practices During a School-Based Hygiene Program in Rural Western Kenya, 2007. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2017, 37, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanton, E.; Ombeki, S.; Oluoch, G.; Mwaki, A.; Wannemuehler, K.; Quick, R. Evaluation of the role of school children in the promotion of point-of-use water treatment and handwashing in schools and households–Nyanza Province, Western Kenya, 2007. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 82, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreibelbis, R.; Freeman, M.C.; Greene, L.E.; Saboori, S.; Rheingans, R. The impact of school water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions on the health of younger siblings of pupils: A cluster-randomized trial in Kenya. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, M.C.; Clasen, T. Assessing the impact of a school-based safe water intervention on household adoption of point-of-use water treatment practices in Southern India. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 84, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, A.; Ma, H.; Ou, J.; Billhimer, W.; Long, T.; Mintz, E.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Luby, S. A cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of a handwashing-promotion program in Chinese primary schools. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 76, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, B.A.; Freeman, M.C.; Garn, J.; Dreibelbis, R.; Saboori, S.; Muga, R.; Rheingans, R. Assessing the impact of a school-based latrine cleaning and handwashing program on pupil absence in Nyanza Province, Kenya: A cluster-randomized trial. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreibelbis, R.; Greene, L.E.; Freeman, M.C.; Saboori, S.; Chase, R.P.; Rheingans, R. Water, sanitation, and primary school attendance: A multi-level assessment of determinants of household-reported absence in Kenya. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2013, 33, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, P.R.; Risebro, H.; Yen, M.; Lefebvre, H.; Lo, C.; Hartemann, P.; Longuet, C.; Jaquenoud, F. Impact of the Provision of Safe Drinking Water on School Absence Rates in Cambodia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, P.; Ryus, C.R.; Dolan, C.S.; Dopson, S.; Scott, L.M. Sanitary Pad Interventions for Girls’ Education in Ghana: A Pilot Study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oster, E.; Thornton, R. Menstruation and Education in Nepal; National Bureau of Economic Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Talaat, M.; Afifi, S.; Dueger, E.; El-Ashry, N.; Marfin, A.; Kandeel, A.; Mohareb, E.; El-Sayed, N. Effects of hand hygiene campaigns on incidence of laboratory-confirmed influenza and absenteeism in schoolchildren, Cairo, Egypt. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Evaluation of the Use and Maintenance of Water Supply and Sanitation System in Primary Schools; UNICEF: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.T.; Dreibelbis, R.; Freeman, M.C.; Ojeny, B.; Rheingans, R. Improving service delivery of water, sanitation, and hygiene in primary schools: A cluster-randomized trial in western Kenya. J. Water Health 2013, 11, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garn, J.V.; Trinies, V.; Toubkiss, J.; Freeman, M.C. The Role of Adherence on the Impact of a School-Based Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Intervention in Mali. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96, 984–993. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, J.; Mcphedran, K. A literature review of the non-health impacts of sanitation. Waterlines 2008, 27, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF; WHO. Core Questions and Indicators for Monitoring WASH in Schools in the Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, G.; Haller, L. Evaluation of the Costs and Benefits of Water and Sanitation Improvements at the Global Level; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A.; Haver, J.; Villasenor, J.; Parawan, A.; Venkatesh, M.; Freeman, M.C.; Caruso, B. WASH challenges to girls’ menstrual hygiene management in Metro Manila, Masbate, and South Central Mindanao, Philippines. Waterlines 2016, 35, 306–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Ackatia-Armah, N.; Connolly, S.; Smiles, D. A comparison of the menstruation and education experiences of girls in Tanzania, Ghana, Cambodia and Ethiopia. Compare 2015, 45, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, C.; Torondel, B. A Systematic Review of the Health and Social Effects of Menstrual Hygiene Management. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).