Abstract

Self-harm among young people remains largely stigmatised and misunderstood. Parents have been identified as key facilitators in the help-seeking process, yet they typically report feeling ill-equipped to support the young person in their care. The aim of this review was to examine the perspectives of both young people (aged 12–28) and parents and to develop the conceptual framework for a future qualitative study. A systematic search of MEDLINE and PsycINFO was performed to identify articles that focused on the experiences of family members and young people related to managing the discovery of self-harm. Fourteen articles were included for review. Four addressed the perspectives of young people and 10 reported on the impact of adolescent self-harm on parents. The impact of self-harm is substantial and there exists a discrepancy between the most common parental responses and the preferences of young people. In addition, parents are often reluctant to seek help for themselves due to feelings of shame and guilt. This highlights the need for accessible resources that seek to alleviate parents’ distress, influence the strategies implemented to manage the young person’s self-harm behaviour, reduce self-blame of family members, and increase the likelihood of parental help seeking.

1. Introduction

Self-harm is defined as any form of intentional self-injury or self-poisoning, irrespective of motive or suicidal intent. Self-harm is associated with an increased risk of mental health problems, suicide, and other adverse outcomes, such as poor educational results and premature death due to risk-taking behaviour [1,2]. Whilst these behaviours are linked to a heightened risk of suicide, not all people who engage in self-harm are suicidal. In these instances, self-harm may occur in an attempt to cope with, or to regulate, intense emotional or psychological distress [1,2]. Given that global self-harm rates have increased over the past two decades [3,4,5], self-harm remains a priority public health concern.

Adolescence represents a critical period of development during which substantial neurological and biological changes occur. In conjunction with these changes, adolescents are exposed to new challenges related to study and work, romantic relationships, and increasing responsibility and independence [6]. As a result of the complex interplay between genetic, biological, psychiatric, psychosocial, and cultural influences, self-harm often begins during adolescence, with the onset of self-harm commonly associated with the beginning of puberty [7,8].

1.1. Prevalence of Self-Harm in Young People

Obtaining information regarding the prevalence of self-harm is problematic given that most young people who engage in self-harm do not seek professional help [9]. Furthermore, whilst hospital admission data provide an indication of self-harm rates and trends, these reveal only the tip of the iceberg as the majority of people who self-harm do not require medical attention, and many hospital presentations do not lead to admissions [10].

Despite the above, community prevalence estimates of self-harm can be inferred based on self-report data. Whilst global variation exists, community research suggests that around 10% of young people have engaged in self-harm behaviours [11,12,13,14,15,16]. In most countries self-harm occurs more frequently in females than males, with a sex ratio as high as 6:1 between the ages of 12 and 15 years [2]. Furthermore, repeated self-harm is common in adolescents with almost two thirds of those who have self-harmed reporting doing so more than four times [11].

In addition to young females, other populations of young people experience disproportionately high rates of self-harm. For example, young people who identify as LGBTIQA+ are twice as likely to engage in self-harm, and this is often the result of bullying and discrimination [17,18,19,20]. Similarly, within Australia, young people aged 15–24 years of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent are up to five times more likely than non-indigenous youths to engage in self-harming behaviours [21]. This discrepancy is widened by the overrepresentation of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander young people in juvenile justice facilities, where approximately 80% of people have a diagnosed mental illness [22]. The rates of self-harm are higher in clinical samples, particularly those with depression, anxiety [23], substance use [16], and borderline personality disorder (BPD) [24]. An awareness of these subgroups of young people, and the unique challenges they face, is essential when addressing their complex support needs, particularly in the context of self-harm.

1.2. Help-Seeking Among Young People

Help-seeking includes seeking support from formal service providers (e.g., health professionals) as well as informal connections (e.g., family members and peers). As mentioned above, only a minority of young people who engage in self-harm seek help [9]. This is concerning given that early intervention and prevention programs have been found to reduce the severity of physical injuries incurred as a result of self-harm, as well as lower the risk of future suicide attempts [25].

Numerous barriers to help-seeking amongst young people have been identified. Fears related to confidentiality breaches, stigma, being appraised as “attention seeking”, and receiving negative reactions are common interpersonal barriers to help-seeking [9,26,27,28]. In addition, the presence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, as well as a belief that one should be able to cope on one’s own, further hinders the ability to reach out [27,29]. Conversely, assurances of confidentiality, being treated respectfully, having a trustworthy person to talk to, and the option of talking to someone of a similar age and background have been identified as facilitators to help-seeking behaviour [28,30].

The literature suggests that of those young people who do seek help, the majority turn to informal supports [9,26]. Whilst peers remain the preferred source of support amongst young people [30,31], parents have been identified by young people as key facilitators in the help-seeking process [26,30]. Indeed, evidence suggests that connectedness between young people and their parents and other carers serves as a protective function for a range of health-outcomes among young people [32,33]. The initial response of parents has been found to affect the timing of formal help-seeking among young people [34] and influence the likelihood of future help-seeking [28]. Unfortunately; however, parents remain uncertain regarding how best to support and manage a young person who is engaging in self-harm [30], do not initiate the professional help-seeking process until the young person experiences a number of difficulties independent of self-harm [34], and are often perceived by young people as responding harmfully [1,30]. While parents may feel uncertainty, when they are appropriately informed and supported (e.g., provided with parenting and family skills training, parent education, and social support), they can play an instrumental role in initiating treatment and supporting young people who self-harm. Notably, efficacious psychosocial treatments for self-harm thoughts and behaviors for young people focus on treating the family, as well as the young person [35]. The global increase in self-harm rates amongst young people raises questions related to the availability and utility of resources designed to provide support to both young people and their parents and carers.

Therefore, the aim of this narrative review is to analyse the common themes from both the perspective of young people and parents and carers. This review will advance understanding of both perspectives, inform consultation exercises with young people and their families, and inform a qualitative study that will adapt an existing resource for parents and carers.

2. Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

The literature search involved an investigation of the experiences of family members and young people with regards to managing the discovery of self-harm within the family. A systematic search of the electronic databases MEDLINE and PsycINFO was performed in September 2017. The following search terms formed the basis of the search strategy: (Parent* OR Carer* OR “Support Person” OR Adult* OR Relative* OR Relation OR Guardian OR “Family Relation*” OR Caregiver* OR “Family Member*” OR Family) AND (“Young Person” OR “Young People” OR “Young Adult” OR Teen* OR Adolesc* OR Youth* OR Student*) AND (“Suicidal Ideation” OR “Self Harm*” OR “Self Injurious Behaviour” OR “Self Mutilation” OR “Self Inflicted Wounds” OR “Self-poison*” OR “Self-injur*” OR “Self-cut*”) AND (Support* OR Resource* OR Program* OR Group OR Brochure OR Pamphlet OR Guideline* OR “Support Group*” OR “Written Communication”). Reference lists of key review papers and included articles were also searched. The search was restricted to academic literature published between 2007 and 2017.

From the pool of potential articles, those that were included for full review and data extraction contained primary research data and specifically addressed: (1) opinions of young people (age range 12–28) on how best to help young people who self-harm and their experience of support after self-harm disclosure; or; (2) parental experiences of supporting a young person through self-harm. Articles were excluded if they were a secondary source, or related to medication, were explicitly related to specific mental health disorders (e.g., BPD), related to self-harm in other populations (i.e., older adults), focused on discussion of screening measures, prevalence or risk factors or were specific to mental health professionals.

3. Results

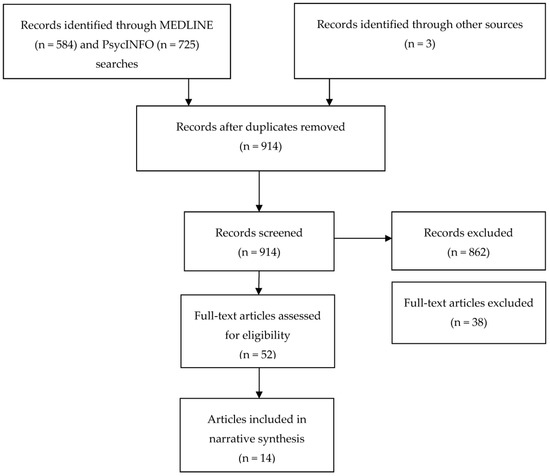

From the search, 1312 articles were identified, of which 14 were included for this review. The literature search is summarised in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Search flow diagram.

Of the included articles, four addressed the perspectives of young people with regards to how best to help young people who self-harm or their experience of support after self-harm disclosure (primarily to parents and peers). Of those four articles, three reported data generated from one study. Ten articles examined the impact of adolescent self-harm on parents and carers. Of those 10 articles, three articles used the same dataset to answer different research questions. All of the articles related to perspectives of young people involved quantitative analysis, whilst those addressing parental perspectives were qualitatively analysed. Studies were conducted across Australia, the UK, USA, and Ireland. A summary of the included articles is displayed in Table 1 and Table 2 and a narrative synthesis of the findings is presented below.

Table 1.

Articles that examined the perspectives of young people (n = 4).

Table 2.

Articles that examined the perspectives of parents and carers (n = 10).

3.1. The Perspectives of Young People

One common theme amongst the articles examining young people’s perspectives was the report that emotionally charged reactions from parents and other caregivers and disciplinary measures are unhelpful and often detrimental [1,30]. These responses, combined with a parental fear of stigma and a general reluctance to seek professional help, have been found to intensify distress in the young person and promote self-harming behaviour as a coping strategy [30]. Conversely, young people reported that the most helpful strategies for assisting them in managing their self-harm were talking and listening (i.e., maintaining open communication) in a non-judgmental way [1,26,30,31]. More specifically, studies identified that parents can help by remaining calm, acknowledging the intensity of their child’s distress, directly asking the young person for guidance in how they can assist, and openly offering their time [1,31].

In addition to talking and listening, young people indicated that parents could support them by providing referrals to professional services and other adults who might be able to help [1,26,30,31]. Active parenting such as gathering family members together for pleasurable activities or to resolve problems, and encouraging the young person to seek help from school staff, are examples that have been provided regarding informal referrals [26,30].

Less frequently suggested, though still important are the views that parents should refer their child to professionals including counsellors, psychologists, GPs or psychiatrists [1,26,30]. The endorsement of helping a young person by referring them to someone, including an adult, relative or teacher, supports previous suggestions that adults should take action when they recognise self-harm [30].

Finally, young people expressed their concerns regarding stigma and confidentiality as barriers to help-seeking [1,26,30,31]. Fears related to judgement and labelling from adults may increase the tendency to turn to peers for support over parents [31]. In addition, young people feel that assurances of confidentiality increase feelings of trust and thus the likelihood of self-harm disclosure [1,26]. In order to address this, they recommend that parents and carers remain non-judgmental and respect the young person’s privacy as far as possible [1,26,30].

Table 3 summarises the above and categorises young people’s views on parental support in the context of self-harm into five broad themes identified by Berger, et al. [30]. The content related to three family sub-themes (more love, talk to family members, and family problems) identified by Fortune, et al. [26] have also been incorporated in the table.

Table 3.

What young people believe parents can do to help young people whom have engaged in self-harm.

3.2. The Perspectives of Parents and Carers

Ten of the included articles investigated the impact that self-harm by young people can have on parents and carers. The results indicated that in addition to the detrimental effects that self-harm has on the young person, it also has a significant impact on their parents and carers [34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44].

Caregiver strain can be conceptualised as the adverse thoughts, feelings, and consequences experienced by those caring for someone who is suffering [44]. Despite little research in this area, the general consensus is that parental well-being and functioning are directly impacted by child mental health status. This was highlighted by all of the 10 included articles that addressed the perspectives of parents and carers [34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Specifically, parents of young people who self-harm reported experiencing significant feelings of guilt and shame, doubts about their ability to parent effectively, fears of exacerbating self-harm and lack of social support and resources to guide them in supporting their young person [37,38,40,42,43,44]. Ferrey and colleagues [38], found that the impact of self-harm discovery on family members is widespread, extending beyond the immediate psychological consequences. This was supported by several of the other articles and included: initial and ongoing impacts on mental health, impact on partners, siblings and wider family networks, social isolation, work and financial complications, and parental perceptions of the future [36,37,38,39,41].

The discovery of self-harm can also lead to changes in parenting strategies and has been shown to alter the power structure in the family as parents become fearful of imposing boundaries for their child [39]. The negative emotions and uncertainty experienced by parents in response to self-harm may lead them to disengage from discussing their child’s behaviour or, alternatively, attempt to exert control [36,37]. For example, parents have reported reading their child’s emails and diaries following the discovery of self-harming behaviour in order to monitor their emotional state [39,41]. These common reactions are those that young people believed to be the most unhelpful [30]. On reflection however, parents also reported that these intense emotional reactions can be detrimental to the parent-child relationship and that instead, maintaining open communication and demonstrating care, affection or love are much more helpful responses [37,39].

Parents typically find communication with their child about self-harm to be a difficult process [40,41]. Kelada and colleagues [41] revealed that parents feel uncertain about how to address the topic and doubt their abilities to support their young person. Parents in this study tended to describe their child is terms such as “unapproachable” and stated that they felt ill-equipped and fearful that discussions could trigger another episode of self-harm [41]. Despite these feelings of uncertainty and the indication that parents require assistance in managing and relating to their child, the stigma attached to self-harm often means that parents are reluctant to seek information and help to support them in their caring role [37]. This can result in perceived isolation, making it difficult for parents to access information that could help them to cope and support their child. Parents have therefore expressed a need for practical and easily accessible information and support, including written information, that may assist them in managing their young person’s self-harm [43].

Bryne, et al. [31] identified parents and carers require both support and information to meet their internal (e.g., emotions and beliefs) and external (e.g., knowledge and coping strategies) needs. In Table 4 the relevant information above has been summarized and presented in one of these two categories.

Table 4.

What parents and carers need to help themselves and the young people whom have engaged in self-harm.

4. Discussion

This review identified 14 articles that had a primary focus on the experiences of family members and young people with regards to managing the discovery of self-harm within the family. Of the 14 included articles, 10 of them reported on the perspectives of parents compared to only four that focused on the views of young people. The findings highlight that the impact of self-harm is substantial, and that the wellbeing of parents and carers can be significantly impacted. In addition, there exists a disparity between the most common parental responses to self-harm and the preferences of young people. For example, attempts to exert control, heightened monitoring and disciplinary measures are perceived by young people to be unhelpful and can serve to perpetuate their self-harming behaviours [41,45]. It was also noted that in many cases, young people prefer to talk to their friends, as opposed to their parents. However parents can play an important role if provided with appropriate support and information.

Understanding the ways in which parents make sense of their child’s self-harm is imperative, as it has been shown that the conceptualisation of self-harm can influence the strategies implemented to manage the behaviour [39]. For example, when parents attribute their child’s self-harm to their developmental stage, this often leads to the use of more supportive parenting strategies [39]. The same is true when parents understand self-harm in the context of mental health difficulties [39]. However, when self-harm is perceived as “naughty”, “bad” or an attempt to exert control, this can result in counterproductive responses such as dismissive disengagement or increased monitoring [39]. This suggests that providing education to parents regarding the broad range of factors that render a young person vulnerable to self-harm, could result in more accurate conceptualisations of the behaviour, and thus the implementation of more supportive and effective parenting strategies.

Given that parents report feeling substantially ill-equipped and isolated when attempting to manage a young person’s self-harm, the results of the present review support the need for more open communication and easily accessible resources that seek to alleviate parents’ distress and isolation. Indeed, parents from the study conducted by Stewart and colleagues [43] expressed a need for practical resources (including leaflets and web resources). Parents are often reluctant to seek help (formal or informal) as a result of the immense feelings of shame and guilt that they experience in relation to their child’s self-harm [37]. This is particularly problematic, as young people indicated that it would be helpful for their parents to facilitate connections with informal supports, such as teachers [30]. Moreover, sometimes disclosure of a young person engaging self-harm is made to parents by school staff [34]. This highlights that the importance of building supportive communities and training gatekeepers, such as school staff—see Robinson, et al. [46] for a review of school-based interventions. Despite their reluctance to seek help, parents frequently indicate that they require support in order to manage their child’s behaviour [37]. This suggests that reducing the stigma attached to self-harm is an essential step in order to promote help seeking behaviour among parents and reduce the incidence of self-harm in young people. In the meantime, given that the internet is used as a resource for health information [47], there is a need for increased availability of online resources that parents can access from the privacy of their own home. This could enable them to contextualise self-harm, avoid self-blame, improve the quality of their relationship with their child, implement effective support for their child, and increase their likelihood of seeking help and support for themselves and their child.

Finally, the divergent views held by young people and by parents identified by the current review, suggest the clear need for information, resources, and models of care and support that can balance the needs of both groups, in order that both young people and their parents/carers receive optimal support. Such resources or treatment strategies should be developed in consultation with young people and parents, delivered, and rigorously evaluated in order to ensure that they are both acceptable and effective.

Limitations

When considering the findings of this review, several limitations need to be taken into account. Firstly, whilst the search strategy was thorough, it is possible that some articles may have been missed, particularly those outside of the specified date range or in languages other than English. Secondly, there is currently no standardised definition of self-harm, and therefore the term may have been employed non-systematically across studies, making it difficult to compare findings. Thirdly, while the articles included were based on large samples of adolescents recruited through schools, the vast majority of young people did not have personal experience of thoughts of self-harm or an actual episode of self-harm, thus their perspectives may differ from young people with lived experience of self-harm. Furthermore, the quantitative and open-ended survey questions employed in the two separate studies did not permit in-depth exploration of the topic or further elaboration of responses. As a result, researchers might not have been able to comprehensively and thoroughly answer research questions. Finally, this was not a systematic review, and as such no double screening or data extraction were conducted; nor is an assessment of study quality provided. That said, it is noted that a number of the included studies were conducted in Western countries and did not employ random sampling procedures, and thus the generalisability of the results in this review may be limited. Overall, given that the present review took the form of a narrative synthesis, results should be treated as an overview, not an expansive, systematic presentation of the evidence.

5. Conclusions

Despite the above limitations, this review offers an important insight into the experiences and views of parents and carers who are supporting a young person with self-harm.

Self-harm among young people is a significant public health issue, and one which remains largely stigmatised and misunderstood. It is estimated that one in 11 young people between the ages of 12 and 17 have self-harmed at some point in their life, yet worryingly, less than a half of these seek help [9,11]. When help is sought, peers tend to be the preferred source of support, reflecting the increased need for independence from parents during this developmental period [30,31]. However, turning to peers for support may also reflect the perception that parents lack understanding and may not be equipped to help [31]. Indeed, research has consistently indicated that parents feel uncertain and fearful when faced with a child who is engaging in self-harm and experience intense feelings of guilt and shame [36,41]. As such, providing evidence-based information about self-harm to parents could increase their confidence in managing and supporting their young person.

Dissemination of this information is likely to assist in the reduction of feelings such as guilt and shame, as well as the stigma that serves as a significant barrier to help-seeking for both parents and young people. Researchers, clinicians and policy makers can assist this process by making information about self-harm more widely available in a range of formats, thus educating the public and reducing misconceptions. It is imperative however, that resources of this nature continue to be informed by the experiences, needs and perspectives of both parents and young people. Empowering parents to effectively support a young person through self-harm is essential for the prevention of self-harm repetition, promotion of future help-seeking, and reduction of suicide risk.

Author Contributions

J.R. conceived and designed the study and obtained the funding. She also contributed to the writing of the manuscript. S.C. helped to design the study, conducted the literature review and the narrative synthesis of the findings. P.T., S.H., S.R., and A.M. helped with study design, and conducted and assisted with the writing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

J.R. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship. S.R. is supported by the Mary Elizabeth Watson Early Career Fellowship in Allied Health from Royal Melbourne Hospital. S.H. is supported by an Auckland Medical Research Foundation Douglas Goodfellow Repatriation Fellowship and CureKids.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Berger, E.; Hasking, P.; Martin, G. Adolescents’ perspectives of youth non-suicidal self-injury prevention. Youth Soc. 2017, 49, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Saunders, K.E.; O’Connor, R.C. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet 2012, 379, 2373–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, P.D.; Tanti, C.; Stokes, R.; Hickie, I.B.; Carnell, K.; Littlefield, L.K.; Moran, J. Headspace: Australia’s National Youth Mental Health Foundation—Where young minds come first. Med. J. Aust. 2007, 187, 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, V.; Flisher, A.J.; Hetrick, S.; McGorry, P. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet 2007, 369, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoliers, G.; Portzky, G.; Madge, N.; Hewitt, A.; Hawton, K.; De Wilde, E.J.; Ystgaard, M.; Arensman, E.; De Leo, D.; Fekete, S. Reasons for adolescent deliberate self-harm: A cry of pain and/or a cry for help? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2009, 44, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bista, B.; Thapa, P.; Sapkota, D.; Singh, S.B.; Pokharel, P.K. Psychosocial Problems among adolescent students: An exploratory study in the central region of Nepal. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K.; Witt, K.G.; Salisbury, T.L.T.; Arensman, E.; Gunnell, D.; Townsend, E.; van Heeringen, K.; Hazell, P. Interventions for self-harm in children and adolescents. Bimonthly J. Psychiatry Adv. 2016, 22, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Hemphill, S.A.; Beyers, J.M.; Bond, L.; Toumbourou, J.W.; McMORRIS, B.J.; Catalano, R.F. Pubertal stage and deliberate self-harm in adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 46, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, S.L.; French, R.S.; Henderson, C.; Ougrin, D.; Slade, M.; Moran, P. Help-seeking behaviour and adolescent self-harm: A systematic review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapur, N.; Steeg, S.; Webb, R.; Haigh, M.; Bergen, H.; Hawton, K.; Ness, J.; Waters, K.; Cooper, J. Does clinical management improve outcomes following self-harm? Results from the multicentre study of self-harm in England. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, D.; Johnson, S.; Hafekost, J.; Boterhoven de Haan, K.; Sawyer, M.; Ainley, J.; Zubrick, S.R. The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing; Department of Health: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2015.

- De Leo, D.; Heller, T.S. Who are the kids who self-harm? An Australian self-report school survey. Med. J. Aust. 2004, 181, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Madge, N.; Hewitt, A.; Hawton, K.; de Wilde, E.J.; Corcoran, P.; Fekete, S.; van Heeringen, K.; De Leo, D.; Ystgaard, M. Deliberate self-harm within an international community sample of young people: Comparative findings from the Child & Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K.; Rodham, K.; Evans, E.; Weatherall, R. Deliberate self harm in adolescents: Self report survey in schools in England. BMJ 2002, 325, 1207–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargus, E.; Hawton, K.; Rodham, K. Distinguishing between subgroups of adolescents who self-harm. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2009, 39, 518–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, P.; Coffey, C.; Romaniuk, H.; Olsson, C.; Borschmann, R.; Carlin, J.B.; Patton, G.C. The natural history of self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood: A population-based cohort study. Lancet 2012, 379, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Semlyen, J.; Tai, S.S.; Killaspy, H.; Osborn, D.; Popelyuk, D.; Nazareth, I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, W.; Pitts, M.; Mitchell, A.; Lyons, A.; Smith, A.; Patel, S.; Murray, C.; Barrett, A. Private Lives 2: The Second National Survey of the Health and Wellbeing of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender (GLBT) Australians; The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Skegg, K.; Nada-Raja, S.; Dickson, N.; Paul, C.; Williams, S. Sexual orientation and self-harm in men and women. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, P.; Cook, A.; Winter, S.; Watson, V.; Wright Toussaint, D.; Lin, A. Trans Pathways: The Mental Health Experiences and Care Pathways of Trans Young People. Summary of Results; Telethon Kids Institute: Perth, WA, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dudgeon, P.; Walker, R.; Scrine, C.; Shepherd, C.; Calma, T.; Ring, I. Effective Strategies to Strengthen the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Melbourne: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, E.B.; Andersen, K.C.; Dev, A.; Kinner, S. Prevalence of mental illness among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Queensland prisons. Med. J. Aust. 2012, 197, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fliege, H.; Lee, J.-R.; Grimm, A.; Klapp, B.F. Risk factors and correlates of deliberate self-harm behavior: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 66, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanen, A.M.; Jackson, H.J.; McCutcheon, L.K.; Jovev, M.; Dudgeon, P.; Yuen, H.P.; Germano, D.; Nistico, H.; McDougall, E.; Weinstein, C. Early intervention for adolescents with borderline personality disorder: Quasi-experimental comparison with treatment as usual. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2009, 43, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aseltine, R.H.; James, A.; Schilling, E.A.; Glanovsky, J. Evaluating the SOS suicide prevention program: A replication and extension. BioMed Cent. Public Health 2007, 7, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortune, S.; Sinclair, J.; Hawton, K. Adolescents’ views on preventing self-harm: A large community study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortune, S.; Sinclair, J.; Hawton, K. Help-seeking before and after episodes of self-harm: A descriptive study in school pupils in England. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klineberg, E.; Kelly, M.J.; Stansfeld, S.A.; Bhui, K.S. How do adolescents talk about self-harm: A qualitative study of disclosure in an ethnically diverse urban population in England. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, N.; Nishida, A.; Shimodera, S.; Inoue, K.; Oshima, N.; Sasaki, T.; Inoue, S.; Akechi, T.; Furukawa, T.A.; Okazaki, Y. Help-seeking behavior among Japanese school students who self-harm: Results from a self-report survey of 18,104 adolescents. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2012, 8, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berger, E.; Hasking, P.; Martin, G. ‘Listen to them’: Adolescents’ views on helping young people who self-injure. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasking, P.; Rees, C.S.; Martin, G.; Quigley, J. What happens when you tell someone you self-injure? The effects of disclosing NSSI to adults and peers. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieving, R.E.; McRee, A.L.; McMorris, B.J.; Shlafer, R.J.; Gower, A.L.; Kapa, H.M.; Beckman, K.J.; Doty, J.L.; Plowman, S.L.; Resnick, M.D. Youth-Adult Connectedness: A Key Protective Factor for Adolescent Health. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, S275–S278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, M.D.; Harris, L.J.; Blum, R.W. The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. J. Paediatr. Child Health 1993, 29 (Suppl 1), S3–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldershaw, A.; Richards, C.; Simic, M.; Schmidt, U. Parents’ perspectives on adolescent self-harm: Qualitative study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 193, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, C.R.; Franklin, J.C.; Nock, M.K. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, S.; Morgan, S.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Boylan, C.; Crowley, S.; Gahan, H.; Howley, J.; Staunton, D.; Guerin, S. Deliberate self-harm in children and adolescents: A qualitative study exploring the needs of parents and carers. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrey, A.E.; Hawton, K.; Simkin, S.; Hughes, N.; Stewart, A.; Locock, L. ‘As a parent, there is no rulebook’: A new resource for parents and carers of young people who self-harm. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrey, A.E.; Hughes, N.D.; Simkin, S.; Locock, L.; Stewart, A.; Kapur, N.; Gunnell, D.; Hawton, K. Changes in parenting strategies after a young person’s self-harm: A qualitative study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2016, 10, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrey, A.E.; Hughes, N.D.; Simkin, S.; Locock, L.; Stewart, A.; Kapur, N.; Gunnell, D.; Hawton, K. The impact of self-harm by young people on parents and families: A qualitative study. Br. Med. J. Open 2016, 6, e009631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, N.D.; Locock, L.; Simkin, S.; Stewart, A.; Ferrey, A.E.; Gunnell, D.; Kapur, N.; Hawton, K. Making Sense of an Unknown Terrain: How Parents Understand Self-Harm in Young People. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelada, L.; Whitlock, J.; Hasking, P.; Melvin, G. Parents’ experiences of nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents and young adults. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 3403–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, G.; O’Brien, L.; Jackson, D. Guilt and shame: Experiences of parents of self-harming adolescents. J. Child Health Care 2007, 11, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.; Hughes, N.D.; Simkin, S.; Locock, L.; Ferrey, A.; Kapur, N.; Gunnell, D.; Hawton, K. Navigating an unfamiliar world: How parents of young people who self-harm experience support and treatment. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2016, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J.; Lloyd-Richardson, E.; Fisseha, F.; Bates, T. Parental secondary stress: The often hidden consequences of nonsuicidal self-injury in youth. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 74, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, K.; Heath, M.A.; Fischer, L.; Young, E.L. Superficial self-harm: Perceptions of young women who hurt themselves. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2008, 30, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Cox, G.; Malone, A.; Williamson, M.; Baldwin, G.; Fletcher, K.; O’Brien, M. A systematic review of school-based interventions aimed at preventing, treating, and responding to suicide-related behavior in young people. Crisis 2013, 34, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wartella, E.; Rideout, V.; Montague, H.; Beaudoin-Ryan, L.; Lauricella, A. Teens, health and technology: A national survey. Media Commun. 2016, 4, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).