Abstract

Studies of complex natural environments often focus on either biodiversity or on isolating organisms with specific properties. In this study, we sought to widen this perspective and achieve both. In particular, hypersaline ecosystems, such as the Sečovlje salt pans (Slovenia), are particularly promising sources of novel bioactive compounds, as their microorganisms have evolved adaptations to desiccation and high light intensity stress. We applied shotgun metagenomics to assess microbial biodiversity under low- and high-salinity conditions, complemented by isolation and cultivation of photosynthetic microorganisms. Metagenomic analyses revealed major shifts in community composition with increasing salinity: halophilic Archaea became dominant, while bacterial abundance decreased. Eukaryotic assemblages also changed, with greater representation of salt-tolerant genera such as Dunaliella sp. Numerous additional microorganisms with biotechnological potential were identified. Samples from both petola and brine led to the isolation and cultivation of Dunaliella sp., Tetradesmus obliquus, Tetraselmis sp. and cyanobacteria Phormidium sp./Sodalinema stali, Leptolyngbya sp., and Capilliphycus guerandensis. The newly established cultures are the first collection from this hypersaline environment and provide a foundation for future biodiscovery, production optimization, and sustainable bioprocess development. The methods developed in this study constitute a Toolbox Solution that can be easily replicated in other habitats.

1. Introduction

Microalgae and cyanobacteria are photosynthetic microorganisms. The fundamental structural difference between them is that microalgae are eukaryotes that contain membrane-bound organelles such as a nucleus, mitochondria, and chloroplasts, whereas cyanobacteria are prokaryotes that lack membrane-bound organelles but possess non-membranous structures [1]. Both are widely found in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems and can multiply rapidly using natural resources such as sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water. Due to these characteristics, they serve as a fundamental component of trophic networks and contribute significantly to the global carbon cycle [2].

Microalgae and cyanobacteria are attractive for biotechnological use due to their short generation times and the ability to grow on non-arable land [3]. Almost every newly discovered cyanobacterium produces one or several unique secondary metabolite (toxins, antibiotics, etc.) [4]. Microalgae are particularly rich in antioxidant pigments, especially carotenoids, which include both carotenes (e.g., carotenes such as α-carotene and β-carotene) and xanthophylls such as lutein and zeaxanthin. These pigments reduce oxidative stress by providing protection against free radicals at the cellular level and contribute to the balance of biological systems [5]. In addition, microalgae contain valuable lipids such as fucosterol and β-sitosterol, as well as polysaccharides. Both microalgae and cyanobacteria produce many industrially relevant bioactive compounds such as polyphenols, phytosterols, tocopherols, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and polysaccharides [6,7]. These molecules exhibit a wide range of biological activities, including antitumor, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, anticoagulant, antihypertensive, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic ones [8]. Their retinal proteins, pigments, extracellular polysaccharides and other metabolites are already being used in medical, cosmetics, food/feed, materials, bioremediation, and other industries [3].

The exact number of algae and cyanobacteria species found in nature is still unknown. Nevertheless, estimates indicate that there are more than 70,000 species, of which more than 40,000 have been scientifically identified. This vast biological diversity is noteworthy not only for their roles in ecosystems but also for their economic significance [9]. Indeed, the global market value of products derived from microalgae and cyanobacteria has been steadily increasing in recent years [10]. The microalgae market was reported to be worth approximately USD 3.4 billion in 2020, and this value is expected to reach USD 19.85 billion by 2028, continuing to grow at a rate of 7.8% [1,11]. Among the main reasons for this increase are the recognition of the potential of valuable compounds contained in microalgae and their evaluation as a sustainable alternative in food and energy production [12]. In this context, the genera Dunaliella, Botryococcus, Chlamydomonas and Chlorella are the most frequently used microalgae for commercial industrial applications [13]. The market size of cyanobacteria-based biological products was reported to be approximately USD 348 million in 2020, showing an average annual growth rate of 10.5% [11]. Among cyanobacteria, Arthrospira (Spirulina) stands out in particular. The global Arthrospira (Spirulina) production has approximately doubled in the last two decades, currently estimated to be at least 30,000 tons yearly [14]. Overall, these numbers demonstrate the growing importance of microalgae and cyanobacteria on a global scale, both in terms of biological diversity and economic potential [1]. Despite this potential, cyanobacteria and microalgae have found only limited industrial use to date, which highlights their significant market growth potential [15].

Beyond their general biotechnological potential, increasing attention has recently been directed toward microorganisms that thrive under extreme environmental conditions. Indeed, some microorganisms can survive in environments with high or low pH (acidophiles and alkaliphiles), extreme temperatures (thermophiles and psychrophiles), high pressure (piezophiles), high salinity (halophiles), and even multiple stress factors (polyextremophiles) thanks to their extraordinary adaptation mechanisms [16]. Microorganisms (prokaryotes and eukaryotes) living in extreme environments can produce extremozymes and extremolytes, the latter being unique organic compounds that do not play a direct role in the normal growth, development, or reproduction processes [17,18]. Under environmental stress conditions, such as low temperature, high salinity, and nutrient limitation, the accumulation of omega-3 fatty acids increases and is considered an adaptive mechanism to maintain cell membrane fluidity. Nannochloropsis species can contain up to 37.8% eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), an omega-3 PUFA. Certain environmental conditions, for example, low temperature and high light intensity, increase EPA production in Nannochloropsis, while phosphate limitation and elevated CO2 levels have similar effect in Phaeodactylum tricornutum [19]. Spirulina platensis, an alkaliphilic cyanobacterium, has a higher vitamin B12 content than any other plant or animal source. It is also an excellent source of provitamin A, vitamin E, thiamine, biotin, inositol, and cobalamin [20]. These stress-driven metabolic responses highlight the potential of extremophilic microalgae and cyanobacteria as targeted platforms for optimized biotechnological applications.

Advances in culturing methods under laboratory conditions and genetic and metabolic data by omics approaches have contributed to a better understanding of the ecological roles and evolutionary processes of extremophiles. The enzymes and metabolites produced by these organisms emerge as promising resources for biotechnology, drug development, bioremediation, energy production, and sustainable industrial applications. All these developments reveal that extremophiles are a critical area of research not only for understanding biodiversity in nature but also for future scientific and technological advances [21].

One of the extreme environments of increasing interest are ecosystems with high or extreme salinity, which host diverse microbial communities. The molecular adaptations and metabolic pathways of microorganisms living in halophilic environments suggest promising biotechnological applications [22,23,24]. Coastal lagoons in Portugal and Spain, the Camargue delta in France, the salt flats of Italy, and the saline wetlands of the Balkan Peninsula represent some of the most characteristic hypersaline systems in Europe in terms of carotenoid-producing microalgae and halophilic microorganisms. [24]. There is a continuous need to understand the metabolic pathways of extremophilic or extremotolerant organisms and the environmental influences that trigger the production of valuable compounds that can enable the marine bioprospecting approach that encompasses sampling, determination of biological diversity, isolation of cultures, screening for new metabolites, isolation and testing of target metabolites, and development of commercial products [25,26]. The isolation and cultivation of organisms that produce biotechnologically relevant compounds remains a critical milestone in this pipeline [27].

Within this research, we conducted a comprehensive assessment of the biological diversity of the Sečovlje salt pans in Slovenia. These extreme ecosystems, which have not yet been fully researched, offer untapped potential from a biotechnological perspective. In line with this, our study contributes to the bioprospecting pipeline development by identifying and culturing biotechnologically prospective microorganisms.

2. Results

2.1. Metagenomic Analysis of Petola

A total of 21 petola samples were collected between April and September 2023 (Table 5), capturing the seasonal variability in temperature and salinity, which we expected to be the most likely drivers of the observed changes in microbial composition. Low salinity refers to values between 4.4 and 5.1% S (April, May, September), whereas high salinity refers to values between 26.8 and 28.7% S (July and August) (see Table 5).

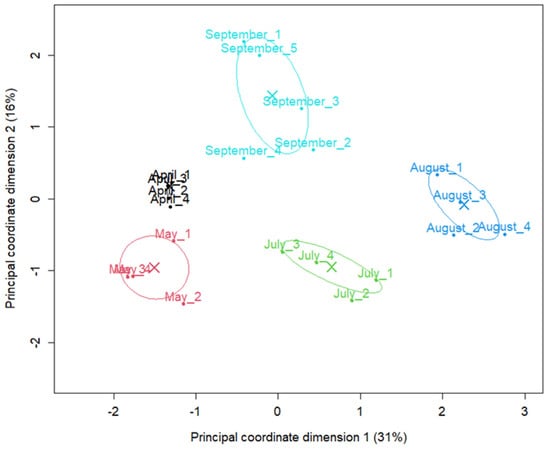

The seasonal shift in abundance of microbial species was evident in the multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot, where samples cluster distinctly by month with August forming a particularly distinct cluster (Figure 1). The first axis (Principal coordinate dimension (1) accounted for 31% of the total variation (dissimilarity), whereas the second axis (Principal coordinate dimension (2) accounted for 16%. Together, these two axes accounted for 47% of the total variation, with samples from different months located in markedly different regions. Samples from April were located very close to each other, suggesting very similar abundance profiles among replicates. In contrast, samples from May, July, August and September showed a wider distribution, suggesting time-dependent changes in taxon abundance.

Figure 1.

Abundance-based ordination of shotgun metagenomic samples by sampling month. Samples were colored and labeled by sampling month. Principal coordinate (MDS/PCoA) plot of samples based on TMM-normalized species count data, generated with the limma plotMDS function. Distances between points represent the leading log2-fold-change in species abundances between samples. Samples are colored and labelled by sampling month; crosses (X) indicate monthly centroids and ellipses the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The percentages in parentheses on the axes indicate the proportion of between-sample variation captured by each dimension.

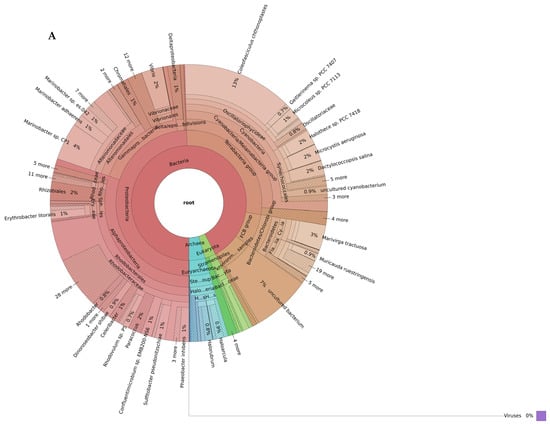

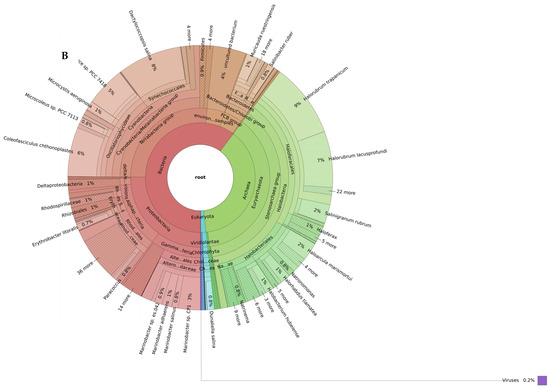

The shotgun metagenomic taxonomic read classification showed that the petola was inhabited by a rich microbial community dominated by Bacteria, followed by Archaea and to a smaller extent eukaryotes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Biodiversity of the Sečovlje salt pans petola mat at low (A) and high (B) salinity levels. Only the most abundant phyla present in all samples (shared_summary) are shown in the outermost ring of each plot (bacteria in red, Archaea in green and eukaryotes in blue). Interactive Krona plots generated by recentrifuge are available at github.com/NIB-SI/AlKoSol. Legend: Taxonomic assignments shown in this Figure 2 reflect the nomenclature present in the Centrifuge default database (built in 2018), which follows earlier taxonomic classifications. Updated taxonomy: Firmicutes (Bacillota), Actinobacteria (Actinomycetota/Actinobacteriota), Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota), Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota), and Chlorobi (now class Chlorobia within Bacteroidota) based on Genom Taxonomy Data Base.

2.1.1. Low-Salinity Biodiversity

At low-salinity conditions, bacteria constituted the vast majority of microbial communities, representing approximately 86% of total diversity (Figure 2A). In this environment, cyanobacteria (26%) and Rhodobacterales (23%) belonging to Alphaproteobacteria stand out as the dominant taxa. In addition, Alteromonadales (11%), Vibrionales (3%), and Chromatiales (1%) from the Gammaproteobacteria subphyla were found in significant proportions. Furthermore, phyla such as Actinobacteriota (7%) and Bacteroidota (7%) also constituted a significant portion of the community. Archaeal communities were represented at a limited level in the low-salinity environment. In particular, the Halobacteria group reached only 4%. Eukaryota members were identified as only a small fraction (2–3%).

Among the identified species in the low-salinity petola, species with biotechnological potential are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Species of biotechnological relevance that were present in the petola microbial mat at low-salinity environmental conditions.

2.1.2. High-Salinity Biodiversity

Organisms in the petola mat samples taken in high-salinity conditions consisted of 56% bacteria, 37% Archaea, 2% eukaryotes (Figure 2B). The bacterial domain included representatives from Alphaproteobacteria (57 species), Bacteroidota (48 species), Gammaproteobacteria (36 species), cyanobacteria (31 species), Bacillota, Actinobacteriota and uncultured subgroups. Among the species in the high-salinity petola, some species with biotechnological potential are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Species of biotechnological relevance that were present in the petola microbial mat at high-salinity environmental conditions.

These species were observed in all petola mat samples taken under high-salinity environmental conditions. Metagenomic results showed that the Archaeon Halorubrum trapanicum was the most common species representing 9% of all species in petola mat samples with high salinity.

2.2. Influence of Salinity on Microbiome Composition

Higher salinity significantly influenced the composition of the microbial community. The most pronounced shift was observed in Archaea, which accounted for only 5% of the community under low-salinity conditions but increased to 38% under high-salinity conditions (Figure 2). Within Archaea, the halotolerant genus Halorubrum increased in abundance from 19% at low salinity to 47% at high-salinity conditions.

Even more strikingly, within Eukaryota, elevated salinity conditions strongly favored the proliferation of the unicellular green algae Dunaliella salina, which represented 0.3% of Eukaryota in low-salinity samples but rose to 54% under high-salinity conditions (Figure 2, see Supplementary Table S2—Petola species read classification). Among Stramenopiles, Nannochloropsis showed the greatest difference between salinity levels, maintaining a relative abundance of about 9–10% of the Eukaryotic community in both environments (see Supplementary Table S2—Petola species read classification).

In both salinity conditions, cyanobacteria were present at similar levels (25–26%), with the community dominated by Coleofasciculus chthonoplastes, followed by Dactylococcopsis salina, Halothece sp. PCC 7418, and Microcystis aeruginosa.

Of the 110 robustly differentially abundant species, 57 were more abundant and 53 were less abundant in the high-salinity samples compared with low-salinity samples (Supplementary Table S3—table merged_results_Brine_salinity_factor). The largest increase in abundance was observed for Dunaliella salina, followed by several halotolerant Archaea and Bacteria. Among Archaea, several Halorubrum species exhibited a 30- to 80-fold increase in abundance relative to low salinity. A more than 60-fold increase was also detected for the bacterium Halanaerobacter jeridensis. Species that were less abundant in high-salinity samples predominantly belong to Alphaproteobacteria and several marine eukaryotes. Notably, none of the Archaeal species decreased in abundance under the high-salinity conditions.

2.3. Cultivation, Isolation and Identification of Cultures

Several photosynthetic species capable of tolerating high-salinity conditions, such as those present in salt pans, were detected in our samples. These species were successfully isolated and cultivated under laboratory conditions. By applying various isolation and purification techniques (such as streak plate method, single filament transfer, serial dilution, and single colony transfer) and cultivation in growth media with varying salinity levels (mimicking freshwater, marine, and hypersaline conditions), we managed to cultivate different photosynthetic microorganisms from Sečovlje salt pans and analyzed them by DNA barcoding of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) genomic region (ITS1-5.8S rDNA-ITS2 for green algae, and16S-23S rDNA ITS for cyanobacteria) (Table 3).

Table 3.

List of cultivated photosynthetic microorganisms isolated from Sečovlje salt pans. The table includes information about the final culture type (axenic or mixed), salinity conditions at the time of sampling (high salinity corresponds to 26.8–28.7% S—July and August, and low salinity corresponds to 4.4–5.1% S—April, May, September), sample types (petola or brine), and the growth media used for laboratory cultivation (freshwater medium—BBM; marine media—ASN-III, BG11+NaCl, BG11+Agar; hypersaline media—Modified Johnson medium, Artari medium). For each isolate, the corresponding GenBank accession numbers are listed.

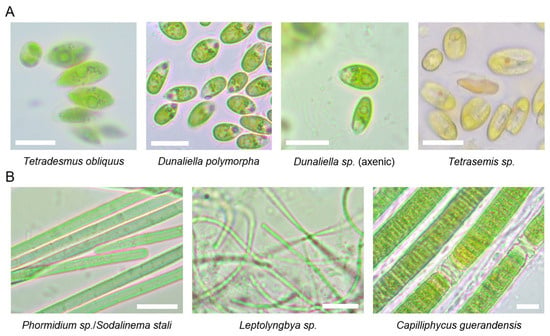

We obtained both axenic and mixed cultures of different Dunaliella species, a mixed culture of Tetraselmis sp. along with an unidentified species (two PCR-products were observed with AGE analysis; however, direct sequencing revealed that one did not match any known species), and an axenic culture of the freshwater alga Tetradesmus obliquus. Only one cyanobacterial culture was purified to axenicity, identified as the filamentous cyanobacterium Phormidium sp./Sodalinema stali. Additionally, two mixed cultures containing at least two different cyanobacteria were cultivated under laboratory conditions (Leptolyngbya sp. co-cultured with Prochlorotrichaceae bacterium, and Capilliphycus guerandensis co-cultured with an unidentified cyanobacterium). These cultures could not be purified to axenicity during several months of the experiment. Axenicity was determined by microscopic examination and the AGE-analysis of genomic markers (algal ITS1-5.8S rDNA-ITS2 or bacterial ITS) amplified using universal primers. Culture was marked as axenic if a single band was recorded in the AGE-analysis of PCR-products, and no visible contaminants were observed macro- and microscopically. Light microscopy was used to confirm DNA barcoding results (Figure 3) and to monitor cell culture purity.

Figure 3.

Microscopy images of algal (A) and cyanobacterial (B) species isolated from Sečovlje salt pans. Representative cells were imaged by Primo star (Zeiss). Scale bar corresponds to 10 μm.

A total of 23 laboratory cultures were obtained from the collected petola and brine samples (Table 5). Using the DNA barcoding approach, we were able to identify different microalgae and/or cyanobacteria in these cultures (Table 3). However, in approximately 15% of cultures, the microalgae/cyanobacteria species could not be identified using DNA barcoding, due to different factors: difficulties with culture growth, failure of universal primers used for DNA barcoding to produce PCR products, unsuccessful sequencing of the PCR amplicons (corresponding to algal or bacterial ITS regions), or the absence of matching reference sequences in GenBank. Interestingly, analysis of two laboratory cultures revealed that they contained the ciliate Schmidingerothrix salina. In both cases, this organism was detected in culture originating from brine samples that were collected during the high-salinity period (August 2023).

3. Discussion

This study evaluated the diversity of microorganisms inhabiting the Sečovlje salt pans in Slovenia and established laboratory cultures, which forms a basis for the extraction of high-value-added products produced by microalgae and other microorganisms that can survive in hypersaline environments. These organisms are of both scientific and industrial importance due to their adaptability to extreme environmental conditions. Although a part of microbial diversity is maintained in several global microbial culture collections, sourcing biotechnologically relevant organisms locally, even from natural parks, is an important market value proposition. Indeed, the increase in consumer awareness to purchase and use sustainably sourced, local and safe products is driving the development of several industrial sectors, such as food, feed and cosmetics [67,68,69]. Local food and other industrial systems can generate higher margins for producers, higher-paid employment opportunities, and increased local economic multipliers compared against ‘long’ supply chains [70].

First, metagenomics was used to assess the seasonal variation in microbial diversity in the Sečovlje salt pans in Slovenia. To our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating the microbial diversity in these salt ponds by focusing on species with biotechnological potential. This is a critical step towards targeted approaches of isolation and potential applications in various industrial sectors. Indeed, Sečovlje salt pans contain species (such as Dunaliella salina) already used in industrial applications which have not been directly targeted for the local industries.

Second, we isolated and cultivated green microalgae and cyanobacteria under laboratory conditions with the primary aim of obtaining axenic cultures of hypersaline photosynthetic microorganisms, originating from the Sečovlje salt pans in Slovenia.

For many industrial purposes, obtaining axenic (pure) cultures is crucial. These pure cultures can then be characterized in terms of their taxonomy, biochemical and physiological properties, and biotechnological potential. Axenic cultures of biotechnologically promising species can be cultivated in large-scale systems for biomass production or used for further metabolic engineering studies [3,10,71]. An additional practical advantage of halophiles is that their cultivation in high-salt environments naturally suppresses contaminants, thereby reducing the need for sterile conditions and lowering sterilization costs [72,73].

Although culture-independent molecular methods have revolutionized our understanding of microbial diversity, culturing remains indispensable. This is because only cultured microorganisms can be used to perform controlled physiological tests, produce new biomolecules, facilitate transition to industrial applications (e.g., enzyme, antibiotic, and pigment production), and enable taxonomic characterization of new species. As a result, a comprehensive approach that begins with metagenomic analysis and continues with targeted culturing emerges as the most effective strategy for both enhancing our fundamental microbiology knowledge and making environmentally or biotechnologically valuable microorganisms available for use.

3.1. Microbial Biodiversity of the Sečovlje Salt Pan

To date, only a limited number of biodiversity studies have been conducted in the Sečovlje salt pans, particularly in terms of taxonomic resolution. This research is the first to focus on taxonomic resolution at the species/genus level and to place special emphasis on species with biotechnological potential. Furthermore, it should be noted that most previous shotgun biodiversity studies of salt pans have focused more on bacteria, Archaea, and viruses, with less emphasis on eukaryotes [74,75,76,77,78]. This may be due to the relatively low abundance of eukaryotes; however, it also presents an important opportunity for further research [79,80].

A pivotal bacterial diversity study of the Sečovlje petola in contrasting salinity levels was performed by Tkavc and colleagues using a low-throughput 16S cloning and Sanger sequencing approach. Our shotgun metagenomics profile results closely resemble the active petola’s top layer described before, showing similar proportions of Gammaproteobacteria, cyanobacteria, Betaproteobacteriota, Bacteroidota, and Bacillota [78].

In the higher salinity, [75] observed higher abundance of Bacillota of the order Halanaerobiales, Actinobacteriota of the genera Ilumatobacter and Nitriliruptor, and halophilic Alphaproteobacteria as well as reduced abundance of Planctomycetota [75]. Comparison with our DNA results also revealed an increase in Bacillota, primarily attributable to halophilic species such as Halanaerobacter jeridensis, Halobacteroides halobius, and Acetohalobium arabaticum (see Supplementary Table S3–merged_results_Brine_salinity_factor). In our study, only about 1% of the reads were classified as Actinobacteriota. Compared to approximately 6% reported by [75], we did not observe any change in the abundance of this phylum between low- and high-salinity conditions. Within Actinobacteriota, approximately half of the reads were classified as the species Ilumatobacter coccineus; however, we did not observe any shotgun reads that were classified as Nitriliruptor. Within Alphaproteobacteria, our results indicate that only two low-abundance species, Rhodovulum sp. JZ3A21 and Sphingopyxis macrogoltabida, were able to proliferate under high-salinity conditions, whereas the abundances of 24 other Alphaproteobacteria were reduced. Similarly, the Planctomycetota were present in very low amounts (<1% of bacteria) in our samples and none of the PVC (Planctomycetota, Verrucomicrobiota and Chlamydiota) bacterial group taxa showed a difference in abundance between high and low salinities. Contrary to 36–54% of cyanobacteria belonging to Leptolyngbyaceae reported by Glavaš and colleagues, this family was represented on average by less than 1% of reads in our samples (Supplementary Table S2—Petola species read classification) [75].

Our findings reveal that salinity is a dominant driver of microbial community structure in petola, consistent with studies of other salt pans such as those along the Mississippi Gulf Coast [81]. Under low-salinity conditions (Figure 2A), we found that the community was dominated by Pseudomonadota, Bacteroidota and Planctomycetota, with Pseudomonas and other facultative anaerobes. In contrast, at high salinity (Figure 2B), the community shifted significantly toward Archaea, with halophilic Halobacteriaceae and Haloferacaceae in the surface layers. High salinity therefore imposes strong selective pressure that excludes non-halophilic groups such as Planctomycetota and reduces the overall bacterial diversity [81].

Sečovlje salt pans contain several eukaryotic species of biotechnological importance. Fistulifera solaris stands out for its high capacity to produce PUFAs, particularly EPA. EPA is an essential fatty acid for human health, with functions including cardiovascular protection, anti-inflammatory effects, and support for brain health. Therefore, the lipids produced by this species are considered valuable in the field of dietary supplements and functional foods, and also show promise for pharmaceutical applications [39,40]. Similarly, carotenoids such as diadinoxanthin and fucoxanthin synthesized by Cylindrotheca closterium are gaining attention due to their potent antioxidant properties. Fucoxanthin is used in the food and cosmeceutical industries, particularly for its potential effects against obesity and its photoprotective properties. The carotenoid profile of this species contributes to the diversification of natural antioxidant sources and offers a sustainable alternative to synthetic antioxidants [41,42,43]. Diatom species such as Thalassiosira oceanica are important not only for metabolite production but also for structural biomaterials. This species capacity to produce bio-silica is of interest for nanotechnology and biomedical applications. In addition, its antimicrobial properties offer potential applications in the medical field. Bio-silica-based materials are being evaluated in innovative biomedical applications such as tissue engineering and drug delivery systems [44].

Other biotechnologically relevant species found in Sečovlje salt pans include Durinskia baltica from the Dinoflagellate class, Lotharella oceanica from the Protozoa class, and Emiliania huxleyi, a Coccolithophore, which all play a major role in the production of calcium carbonate [82]. Finally, our results revealed the presence of nitrogen (N2)-fixing Halothece sp. [83], Phormidium lucidum with rich carbohydrate, phycobiliprotein, and vitamin C content [84] and Pseudanabaena sp. with potential for biodiesel production [85].

Research on microbial diversity in saline ecosystems has expanded substantially over the past decade, providing a clearer understanding of both the ecological roles and biotechnological potential of extremophilic phototrophs. When comparing salt lakes and ponds in different geographical regions, the composition and dominant groups of microbial communities vary depending on environmental conditions. The study on the Monegros lakes revealed that inland salt lakes possess high phylogenetic richness and unexpected levels of diversity, particularly among protists, and exhibit a high degree of genetic novelty in Archaea (especially in the Halobacteriaceae and DHVEG-6 groups (Deep Hydrothermal Vent Euryarchaeotal Group 6)) [86]. In contrast, at Sečovlje Salt pans, cyanobacteria and phototrophic Pseudomonadota (Rhodobacterales) were dominant under low-salinity conditions, while Archaea (Halobacteria) communities were prominent at high salinity. Therefore, the role of Archaea became more pronounced with increasing salinity in both systems. As salinity increases, the dominance of Archaea, particularly members of the class Halobacteria, becomes evident, representing a characteristic pattern widely described in the literature for hypersaline ecosystems [87]. This transition indicates that extreme salinity conditions are tolerated by Archaea with exceptionally high osmotic stress resistance, and that these groups achieve ecological advantage in such environments through metabolic strategies based on phototrophic pigments and retinal proteins [24]

3.2. Targeted Organisms with Biotechnological Potential: Isolation of Microalgal and Cyanobacterial Cultures

Salt pans are areas where light, temperature and salinity conditions change rapidly, and these environmental changes affect microbial diversity and the content of the bioactive substances that microorganisms inhabiting salt pans produce. Consequently, abiotic parameters such as light transmission and oxygen availability significantly affect culture conditions, thereby influencing both microbial growth and the production of target compounds [88]. For example, Dunaliella species have higher antimicrobial properties under osmotic stress conditions [89]. Therefore, a better understanding of the chemical and physical conditions, and their effect on algal metabolism is crucial for laboratory-scale production and future industrial scale-up. The initial understanding of the environmental effects, such as temperature and salinity throughout the year, can thus contribute to improving the cultivation conditions for optimal yields of biomass and targeted bioactive compounds.

Through our targeted cultivation attempts, we aimed to establish cultures of species with potential for their use in various industries (Table 4).

Table 4.

Biotechnological potentials, industrial applications, and market value of cultivated microalgae and cyanobacteria.

Through regular sampling campaigns on the same location, our study demonstrates that the microbial community changes with increased salinity and temperatures from April to August (Figure 2). The most striking is the abundance increase in the green algae Dunaliella salina and the halophilic Archaea. These are typical representatives of hypersaline environments such as solar salterns, brine pools, salt lakes, deserts and intertidal zones [110].

We successfully cultivated axenic and mixed cultures of green microalgae from the genus Dunaliella (Table 3). Different species of Dunaliella were obtained from samples collected during both high- and low-salinity seasons, indicating that these algae are present in the Sečovlje salt pans throughout the whole year. They can be efficiently isolated using hypersaline nutrient media, such as Modified Johnson’s medium and Artari medium (see Supplementary Table S1—Culture_Medium_Contents). This finding aligns with metagenomics results from this study, which detected multiple Dunaliella species in petola samples in low- and high-salinity season (see Figure 2, see Supplementary Table S3—merged_results_Brine_salinity_factor). Indeed, besides D. salina, which is one of the most halophilic species within the Dunaliella genus, other less halophilic species also inhabit the salterns. For example, D. viridis and D. parva growth is superior in mediums with intermediate salinity (around 1 M NaCl), while D. salina thrives optimally at higher salinities—up to 3 M NaCl [111].

The taxonomic classification of the isolated Dunaliella species based on morphological traits and DNA barcoding of the ITS region proved challenging. Earlier studies relied heavily on morphological features; however, because cell size and shape change considerably in response to environmental conditions such as nutrient availability, salinity, temperature, and light intensity, morphology-based identification alone does not allow reliable species-level resolution [111,112]. Therefore, modern approaches use molecular techniques like DNA barcoding of the 18S rDNA and ITS regions, analysis of ITS2 secondary structure, phylogenetic reconstruction, intron analysis of the 18S rDNA, and fingerprinting methods for accurate species identification [111,113,114]. The ITS region is particularly effective for barcoding members of Chlorophyta group, including Dunaliella, due to its high intraspecies variability, availability of universal set of primers, and well-established database of reference sequences [115]. Despite the effectiveness of ITS barcoding for many green algae, this study identified only Dunaliella polymorpha to the species level. For other samples, species-level identification was not achieved due to high similarity among the sequenced regions and the presence of multiple similar reference sequences in GenBank. Previous reports have highlighted issues with having confusing and potentially incorrect taxonomic classifications for Dunaliella species. Notably, one of the main challenges in Dunaliella taxonomy is the absence of a well-established and universally accepted classification system. Both Dunaliella viridis and Dunaliella salina have been shown to consist of multiple genetically distinct clades rather than forming single coherent phylogenetic groups [116,117,118]. It is increasingly apparent that many database entries, particularly from older studies, are mislabeled or misnamed, indicating a need for a revision of Dunaliella taxonomy [111,117]. Importantly, incorporating ITS2 secondary structure analysis may overcome some of these limitations. Structural features such as compensatory base changes and helix architecture provide phylogenetically informative characters that are not evident from primary sequence alone. Detailed ITS2 structural assessment has already proven useful in resolving complex species boundaries, as demonstrated in the taxonomic re-evaluation of D. viridis [114].

Besides Dunaliella species, two other green microalgae were isolated: Tetraselmis sp. and Tetradesmus obliquus. Both hold high potential for biotechnology use [90]. For example, Tetraselmis sp. can be an alternative food production source [119]. Indeed, Tetraselmis sp. is rich in vitamins, carotenoids and protein, similar to microalgae such as Chlorella and Arthrospira, which are considered as safe food that does not contain pathogens and toxic components [119]. Tetradesmus obliquus produces lutein, β-carotene, protein and essential fatty acids used in cosmetics, medicine and pharmaceuticals [120]. Interestingly, despite its laboratory growth, the genus Tetradesmus was not identified in the metagenomics analysis of petola samples, and Tetraselmis was present only in some of them at a low relative abundance. This indicates that these species might inhabit the brine but not the petola mat.

Next, we established cultures of various filamentous cyanobacteria. Species that grew in hypersaline nutrient media included Phormidium sp./Sodalinema stali (axenic culture) and Leptolyngbya sp. in combination with a Prochlorotrichaceae bacterium (mixed culture) (see Table 3). Additionally, cultivation in marine medium ASN-III (see Supplementary Table S1—Culture_Medium_Contents) enabled the growth of a mixed culture of Capilliphycus guerandensis and another filamentous cyanobacterium, likely from the order Leptolyngbyales, based on observed morphological characteristics (Figure 3).

Surprisingly, Coleofasciculus chtonoplastes, the predominant cyanobacterium identified by metagenomic analysis, could not be cultivated under laboratory conditions. This could be due to the lack of its adaptation to the laboratory conditions or a slower growth compared to other cyanobacterial strains (such as Phormidium sp./Sodalinema stali) under chosen conditions, which allowed the latter to outcompete all species present in the crude environmental samples. C. chtonoplastes is a mat-forming cyanobacterium [121]. The biotechnological potential has already been elucidated for mat-forming taxa, with their enzymes and antimicrobials [122]. Hence, the isolation of this species should remain a target in future studies.

The cyanobacterium Phormidium sp. is another species of biotechnological potential. It produces phycocyanin, which is important for cosmetics and medicine applications [123]. Many cyanobacterial species form extracellular mucous sheaths that are inhabited by heterotrophic microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi [124]. Indeed, Phormidium sp. forms dense biofilms under high-salinity conditions as it has the capacity to produce significant amounts of extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) [125,126]. As filamentous cyanobacteria typically coexist within complex microbial mats in their natural environments, separation of species is challenging. Moreover, cyanobacteria are known to form symbiotic interactions with other microorganisms [127], which may explain why mixed cultures are often obtained as the final culture. The ability to grow mixed or axenic cultures was dependent on the salinity of the culture medium. While the detailed results are presented in Section 2, it is notable that hypersaline conditions favored the growth of axenic Phormidium sp./Sodalinema stali, whereas intermediate salinity supported more complex microbial associations [128,129]. Gradually increasing the salinity of the medium may be a promising strategy for purifying cyanobacterial hypersaline species.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Description of the Study Area

Located in southwestern Slovenia and covering an area of about 670 hectares, the Sečovlje Salina Nature Park is the largest coastal wetland in Slovenia and contains the northernmost active solar salt pans in the Mediterranean. The traditional manual salt harvesting is based on the cultivation of the microbial mat named petola, which covers the bottom of the crystallization pans. This active biological layer has many roles, like stabilizing the sediment surface, preventing contamination of the harvested salt with the bottom mud, and enhancing salt purity [74,75,77]. Recently, it was also revealed that salt from Sečovlje salt pans contains higher concentrations of glutamic acid, a key contributor to umami taste [130].

4.2. Sample Site

Samples of the microbial mat petola were collected from the crystallizing pan number S10 (45°29′21.58″ N, 13°35′59.17″ E) during spring, summer and autumn in 2023 (Table 5). Short vertical cores of the upper 1 cm were collected in plastic sterile containers. Brine salinity was measured with a hydrometer, and the temperature-corrected Baumé [131] was converted into mass percent salinity (S %) (Equation) [132,133]. In solar salt pans, the salinity of brine in the crystallizing pans is influenced by the evaporation of seawater for salt production. The cultivation of the microbial mat petola requires it to be predominantly covered by water of seawater salinity (approx. 4–5% S) during the pre-harvest (spring) and post-harvest (autumn) period. In contrast, during the summer season, the salinity of the brine increases significantly, up to 29% S. Low salinity refers to values between 4.4 and 5.1% S, whereas high salinity refers to values between 26.8 and 28.7% S (Table 5).

Table 5.

Information of samples collected from Sečovlje salt pans in 2023.

4.3. Shotgun Metagenomics

4.3.1. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from the petola samples using the PowerLyzer PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA; Cat no. 12855-50). The isolation process was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with minor modifications as follows: (i) Sample homogenization was performed using FastPrep (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA, USA) bead grinder, consisting of two homogenization rounds at 6.5 m/s for 45 s each, with an intermediate incubation period of 10 min at 70 °C accompanied by shaking at 2000 rpm. (ii) Following the precipitation with Solution C3, only 625 μL of the supernatant was transferred, and 1000 μL of Solution C4 was added in the subsequent step. (iii) The final elution of DNA was performed twice, each time using 75 μL of Solution C6 with a 10 min incubation. DNA was checked for purity and quantity on both NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and TapeStation (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Samples passing the quality and quantity requirements of the sequencing service (A260/280 > 1.8 and concentration > 10 ng/μL) were selected for shotgun metagenomics sequencing (Table 5). DNA library preparation and sequencing on Illumina NovaSeq X Plus in paired-end 150 bp mode were performed by Novogene Ltd. (Sacramento, CA, USA).

4.3.2. NGS Data Analysis

Adapter trimming and read quality control was performed by Novogene Ltd. Taxonomic classification of reads was performed using centrifuge v1.0.4 [134] by defining a random generator seed (−seed 42) and ensuring a single call per read (−k 1). Centrifuge-supplied “NCBI nucleotide nt” database built in 2018 was used. Because phylum-level nomenclature has been revised since that release, the names in the text were updated to current names, while the original Centrifuge labels are given in parentheses where relevant. Read counts obtained by centrifuge were further processed with Recentrifuged v1.14.0 [135] by setting parameters to retain only high-confident classifications (−−minscore 75) and removing any contaminants associated with taxa “Sinsheimervirus”, “chordates”, “unclassified sequences”, and “other sequences” (−x 1,910,954 −x 7711 −x 12,908 −x 28,384). Recentrifuge was run independently for low- and high-salinity samples. Interactive Krona plots were exported and are available at github.com/NIB-SI/AlKoSol.

Differential abundance analysis for identified species was performed in the R statistical environment v4.3.1 using MaAslin2 (Microbiome Multivariable Association with Linear Models 2) package [136]. The raw count data was filtered to retain only species with at least 2 reads in at least 10% of samples. For statistical comparisons, salinity level was used as a fixed effect variable, with “low” as the reference value (Table 5). To obtain a robust set of differentially abundant species, the intersection of three statistical methods was used: (i) linear model fit (LM) method, (ii) negative binomial (NEGBIN) method available in MaAslin2, and (iii) voomLmFit method from the edgeR package [137]. For the LM method, the count data was normalized with cumulative sum scaling (CSS) followed by log2 transformation, whereas for the NEGBIN method, CSS normalization was applied without additional transformation. For the voomLmFit method, the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) normalization was used. Species were considered differentially abundant if they were detected in at least 12 out of 21 (57%) samples (as determined by MaAslin2 methods) and if statistical tests of all three methods yielded adjusted p-values below 0.05. The Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) plot was generated using plotMDS function from the limma package and generated from filtered TMM-normalized count matrix as input.

4.4. Isolation and Maintenance of Microalgal/Cyanobacterial Cultures

A 1 × 1 cm section of petola was transferred into approximately 10–20 mL of liquid medium or plated onto a solid selective medium (agar thickness of 1 cm) in Petri dishes. Brine water samples were directly used for inoculation of selected growth medium. Each growth medium was designed to isolate different species of microalgae and cyanobacteria (see Supplementary Table S1—Culture_Medium_Contents): Johnson’s medium modified with 1.5 M NaCl [138], ASN-III medium [139], Artari medium [140], BG-11 medium supplemented with 0.6 M to 4 M NaCl [141], and Bold’s basal medium [142]. Following the initial inoculation, the cultures were incubated for 2–4 weeks at 22 ± 2 °C for the spring season and 26 ± 2 °C for the summer season under light intensity of 25 µmol m−2 s−1 ± 15% (cold white light). Cultures were observed regularly and subcultured into fresh medium once they turned dark green or reached high density. Enriched cultures were then purified in multiple steps using a combination of purification techniques, such as the streak plate method, serial dilution in liquid media and single cell isolation. For purification of some cyanobacterial strains, cultures were grown on 1% agarose plates filled with liquid medium to mimic natural conditions in salt pans and purified sequentially by transfer of single filaments.

4.5. DNA Barcoding: DNA Isolation, PCR and Sequencing of Laboratory-Grown Microalgae

Total genomic DNA was isolated from 5 to 10 mL of culture (the volume depended on the cell culture density). Microalgal biomass was pelleted by centrifugation and the pellet was resuspended in 500 µL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4 Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Next, samples were sonicated 4 times for 15 s (LABSONIC M ultrasonic homogeniser, Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) on ice and centrifuged at 10,000× g for 10 min. The supernatant was used for extraction with DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Cat no. 69506, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (starting at the 2nd step of the protocol). The elution volume was 100 µL. The concentration and purity of isolated DNA was determined spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop 2000c, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) genomic regions were amplified from isolated DNA by PCR Veriti Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The ITS1-5.8S rDNA-ITS2 region of green algae was amplified using primers Fw_ITS1 and Rv_ITS4 [115]. For amplification of cyanobacterial ITS region, primers 322 and 340 were used [143]. PCR reactions were prepared as a 20 µL mixture, containing 12.4 µL of ultrapure water, 4 µL of 5× High-Fidelity green buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.5 µM of primers, 1 µL of isolated genomic DNA (concentration 20–200 ng/µL), and 0.4 U of Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The PCR amplification protocol was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 8 min, 40 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, Tm (see Table 6) for 45 s and 72 °C for 75 s, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 8 min.

Table 6.

Primers, used for barcoding samples.

The PCR-products were separated on a 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel in 1× TAE buffer and stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Single bands were excised and purified using the E.N.Z.A. gel extraction kit (Cat no. D2500-02, Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified PCR-products were directly sequenced by Sanger method (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany) using the primers described in Table 6.

Homologues of the algal (ITS1–5.8S rDNA–ITS2 and bacterial ITS) sequences were searched using the BLASTN heuristic algorithm for pairwise alignment against the core nucleotide (core nt) database. Match quality was evaluated based on sequence identity, coverage, and e-value [144].

4.6. Microscopy

Cultivated microorganisms were regularly observed and imaged with the optical microscope Primo star (Carl Zeiss, Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany). Observed morphological and physiological features included shape, length and width, color, motility, presence of multicellular structures, and the presence of extracellular mucilage (on filamentous cyanobacteria). Representative micrographs of cultivated cultures were taken using Plan-Achromat 100×/1.25 Oil objective (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany).

5. Conclusions

This study is the first step in a comprehensive bioprospecting in the Sečovlje salt pans. We addressed the biodiversity of microorganisms, focusing on those with high potential for biotechnological applications and their remarkable ability to survive extreme environmental conditions. Furthermore, we established cultures of biotechnologically relevant green microalgae and cyanobacteria. The establishment of laboratory-scale cultures is significant for further optimization of biomass accumulation and therefore the yield of selected bioactive compounds. Among the targeted organisms, we established cultures of: Tetradesmus obliquus, which produces lutein, β-carotene, antioxidant compounds, and high fatty acid content; Dunaliella sp., which stands out for its high β-carotene and glycerol production; Tetraselmis sp., which produces polysaccharides, fatty acids such as EPA and DHA, and antimicrobial peptides; Phormidium sp./Sodalinema stalli; Leptolyngbya sp., which produces high protein content, UV-absorbing compounds (MAAs), phycocyanin, and polysaccharides; and Capilliphycus guerandensis, which has cytotoxic activity. Additionally, the metagenomic evaluation of biodiversity uncovered other organisms of potential biotechnological interest, such as Halocynthiibacter arcticus, Spiribacter salinus, Cylindrotheca Closterium, Halomicrobium mukohataei, and Halopenitus persicus (see the Supplementary Table S4_Extended_Discussion) [28,29,32,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,62,63,64,126,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170].

It is important to highlight that a successful completion of laboratory-scale experiments does not guarantee the industrial transition. This transition requires more comprehensive and multidisciplinary research. The development of large-scale cultivation technologies, the reduction in contamination risk, and the increase in the yield of targeted metabolites are priority objectives. At the same time, the development of environmentally friendly, highly efficient, and cost-effective methods for the extraction and purification of products will determine the competitiveness of these natural compounds against their synthetic counterparts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/md24010026/s1, Supplementary Table S1—Culture_Medium_Contents; Supplementary Table S2—Petola species read classification; Supplementary Table S3—merged_results_Brine_salinity_factor; Supplementary Table S4—Extended_Discussion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., A.R. and M.D.; methodology, E.A., D.B., N.G., M.P. and P.T.V.; validation, E.A., A.R., M.P., D.B. and P.T.V.; formal analysis, E.A., P.T.V. and M.P.; investigation, E.A., D.B., M.P. and P.T.V.; resources, ALL AUTHORS; data curation, E.A., M.P. and P.T.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., E.A. and P.T.V.; writing—review and editing, All Authors; visualization, E.A., M.P. and P.T.V.; supervision, A.R. and M.D.; project administration, A.R.; funding acquisition, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency, grant number L4-4564, 1000-2025-8869, and research core funding No. P4–0432, and Interreg Euro-MED Programme, co-funded by the European Union, Project No. Euro-MED 0200514–2B-BLUE project. This publication is based upon work from COST Action CA18238 (Ocean4Biotech) and Ocean4Biotech, the professional association joining marine biotechnologists.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are publicly accessible in the GitHub repository at: github.com/NIB-SI/AlKoSol, which has been archived on Zenodo (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17975011). The raw shotgun metagenomic sequencing data generated in this study are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the project accession number PRJNA1225550. Supplementary Data supporting the findings presented in the manuscript, including all Supplementary Tables, are provided within the Supplementary Materials. No additional datasets were generated or utilized beyond those made available through the repository and Supplementary Files. The nucleotide sequences generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the following accession numbers: PX677330, PX677331, PX677332, PX677333, PX677334, PX677335, PX677336, PX677337, PX677338, PX684463, PX684464, PX684465, PX684466, PX684467, PX684468, PX684469, and PX684470.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Sara Fišer, Ernesta Grigalionyte-Bembič, Luen Zidar, and Katja Klun from the National Institute of Biology, Slovenia for their kind assistance, technical support, and collaboration during the fieldwork and laboratory phases of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Author Neli Glavaš is employed by SOLINE Pridelava soli d. o. o, Portorož, Slovenia, but this affiliation does not represent a conflict of interest with the content of this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| USD | United State Dollar |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic Acid |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| pH | Potential of Hydrogen |

| MDS | Multidimensional scaling |

| LogFC | Logarithm of Fold Change |

| PHA | Production of poly-hydroxy-alkanoates |

| Mn | Manganese |

| β-Carotene | Beta Carotene |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| rDNA | Ribosomal Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ITS | Internal transcribed spacer |

| Be° | Baumé |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| AGE | Agarose Gel Electrophoresis |

| MAE | Microwave-assisted extraction |

| SPE | Supercritical fluid extraction |

| UAE | Ultrasound-assisted Extraction |

| UV | Ultra Violet |

| DHA | Dihydroxyacetone |

| AMPs | Antimicrobial Peptides |

| EPSs | Extracellular Polymeric Substances |

| MAAs | Mycosporine-like Amino Acids |

| % S | Salinity |

| ng | Nanogram |

| μL | Micro liter |

| MaAslin2 | Microbiome Multivariable Association with Linear Models 2 |

| LM | Linear model fit |

| NEGBIN | Negative binomial |

| CSS | Cumulative sum scaling |

| TMM | Trimmed mean of M-values |

| BG11 | Blue-Green medium 11 |

| ASN-III | Artificial Seawater Medium III |

| µmol | Micromole |

| m | Meter |

| s | Second |

| mM | Millimolar |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleotide Triphosphate |

| Tm | Melting Temperature |

| U | Unit |

| (w/v) | Weight/volume |

| TAE buffer | Tris–Acetate–EDTA |

| BLASTN | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

References

- Hachicha, R.; Elleuch, F.; Ben Hlima, H.; Dubessay, P.; de Baynast, H.; Delattre, C.; Pierre, G.; Hachicha, R.; Abdelkafi, S.; Michaud, P.; et al. Biomolecules from Microalgae and Cyanobacteria: Applications and Market Survey. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdur Razzak, S.; Bahar, K.; Islam, K.M.O.; Haniffa, A.K.; Faruque, M.O.; Hossain, S.M.Z.; Hossain, M.M. Microalgae Cultivation in Photobioreactors: Sustainable Solutions for a Greener Future. Green Chem. Eng. 2024, 5, 418–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, A.; Barbier, M.; Bertoni, F.; Bones, A.M.; Cancela, M.L.; Carlsson, J.; Carvalho, M.F.; Cegłowska, M.; Chirivella-Martorell, J.; Conk Dalay, M.; et al. The Essentials of Marine Biotechnology. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 629629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnery, J.K.; Mevers, E.; Gerwick, W.H. Biologically Active Secondary Metabolites from Marine Cyanobacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyaswari, S.G.; Metusalach; Kasmiati; Amir, N. A Review: Bioactive Compounds of Macroalgae and Their Application as Functional Beverages. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 679, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Meenatchi, R.; Pachillu, K.; Bansal, S.; Brindangnanam, P.; Arockiaraj, J.; Kiran, G.S.; Selvin, J. Identification and Characterization of the Novel Bioactive Compounds from Microalgae and Cyanobacteria for Pharmaceutical and Nutraceutical Applications. J. Basic Microbiol. 2022, 62, 999–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Kaur, R.; Bansal, A.; Kapur, S.; Sundaram, S. Chapter 8—Biotechnological Exploitation of Cyanobacteria and Microalgae for Bioactive Compounds. In Biotechnological Production of Bioactive Compounds; Verma, M.L., Chandel, A.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 221–259. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, J.P.; Muñoz, A.A.; Figueroa, C.P.; Agurto-Muñoz, C. Current Analytical Techniques for the Characterization of Lipophilic Bioactive Compounds from Microalgae Extracts. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 149, 106078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayo, A.; Morales, V.; Rodríguez, R.; Vicente, G.; Bautista, L.F. Cultivation of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria: Effect of Operating Conditions on Growth and Biomass Composition. Molecules 2020, 25, 2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoveská, L.; Nielsen, S.L.; Eroldoğan, O.T.; Haznedaroglu, B.Z.; Rinkevich, B.; Fazi, S.; Robbens, J.; Vasquez, M.; Einarsson, H. Overview and Challenges of Large-Scale Cultivation of Photosynthetic Microalgae and Cyanobacteria. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.Z.; Cai, S.; Liu, L.; Cheng, Q.; Hu, Z.; Zheng, Y. Cyanobacterial Metabolic Pathways of Industrial Interests. In Cyanobacteria Biotechnology: Sustainability of Water-Energy-Environment Nexus; Mehmood, M.A., Malik, S., Musharraf, S.G., Boopathy, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Loke Show, P. Global Market and Economic Analysis of Microalgae Technology: Status and Perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 357, 127329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais Junior, W.G.; Gorgich, M.; Corrêa, P.S.; Martins, A.A.; Mata, T.M.; Caetano, N.S. Microalgae for Biotechnological Applications: Cultivation, Harvesting and Biomass Processing. Aquaculture 2020, 528, 735562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.V.; Benemann, J.; Vonshak, A.; Belay, A.; Ras, M.; Unamunzaga, C.; Cadoret, J.-P.; Rizzo, A. Spirulina in the 21st Century: Five Reasons for Success in Europe. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025, 37, 2203–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, M.; Abbriano, R.M.; Pernice, M.; Sutherland, D.L.; Commault, A.S.; Hall, C.C.; Labeeuw, L.; McCauley, J.I.; Kuzhiuparambil, U.; Ray, P.; et al. Emerging Technologies in Algal Biotechnology: Toward the Establishment of a Sustainable, Algae-Based Bioeconomy. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshney, P.; Mikulic, P.; Vonshak, A.; Beardall, J.; Wangikar, P.P. Extremophilic Micro-Algae and Their Potential Contribution in Biotechnology. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 184, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, O.V.; Gabani, P. Extremophiles: Radiation Resistance Microbial Reserves and Therapeutic Implications: Radiation Resistance Microbial Reserves and Therapeutic Implications. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavasi, V.; Soru, S.; Cao, G. Extremophile Microalgae: The Potential for Biotechnological Application. J. Phycol. 2020, 56, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Prasad, P.; Sreedhar, R.V.; Akhilender Naidu, K.; Shang, X.; Keum, Y.-S. Omega−3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs): Emerging Plant and Microbial Sources, Oxidative Stability, Bioavailability, and Health Benefits—A Review. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantar, M.; Svirčev, Z. Microalgae and Cyanobacteria: Food for Thought. J. Phycol. 2008, 44, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampelotto, P.H. Extremophiles and Extreme Environments: A Decade of Progress and Challenges. Life 2024, 14, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, L.; Ben Ali, M. Chapter 5—Halophilic Microorganisms: Interesting Group of Extremophiles with Important Applications in Biotechnology and Environment. In Physiological and Biotechnological Aspects of Extremophiles; Salwan, R., Sharma, V., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, G.M.; Pire, C.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Hypersaline Environments as Natural Sources of Microbes with Potential Applications in Biotechnology: The Case of Solar Evaporation Systems to Produce Salt in Alicante County (Spain). Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekanov, K. Diversity and Distribution of Carotenogenic Algae in Europe: A Review. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yovchevska, L.; Gocheva, Y.; Stoyancheva, G.; Miteva-Staleva, J.; Dishliyska, V.; Abrashev, R.; Stamenova, T.; Angelova, M.; Krumova, E. Halophilic Fungi—Features and Potential Applications. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvam, J.; Mal, J.; Singh, S.; Yadav, A.; Giri, B.; Pandey, A.; Sinha, R. Bioprospecting Marine Microalgae as Sustainable Bio-Factories for Value-Added Compounds. Algal Res. 2024, 79, 103444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavčar Verdev, P.; Dolinar, M. A Pipeline for the Isolation and Cultivation of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria from Hypersaline Environments. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürch, T.; Preusse, M.; Tomasch, J.; Zech, H.; Wagner-Döbler, I.; Rabus, R.; Wittmann, C. Metabolic Fluxes in the Central Carbon Metabolism of Dinoroseobacter shibae and Phaeobacter gallaeciensis, Two Members of the Marine Roseobacter Clade. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.T.H.L.; Yoo, W.; Lee, C.; Wang, Y.; Jeon, S.; Kim, K.K.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, T.D. Molecular Characterization of a Novel Cold-Active Hormone-Sensitive Lipase (HaHSL) from Halocynthiibacter arcticus. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Lu, J.; Ding, W.; Zhang, W. Genomic Features and Antimicrobial Activity of Phaeobacter inhibens Strains from Marine Biofilms. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, M.; Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Li, B.; Xue, C.-X.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X.-H. Comparative Genomic and Metabolic Analysis of Manganese-Oxidizing Mechanisms in Celeribacter manganoxidans DY25T: Its Adaptation to the Environment of Polymetallic Nodules. Genomics 2020, 112, 2080–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arahal, D.R.; Lucena, T.; Rodrigo-Torres, L.; Pujalte, M.J. Ruegeria denitrificans sp. nov., a Marine Bacterium in the Family Rhodobacteraceae with the Potential Ability for Cyanophycin Synthesis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 2515–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, B.; Zheng, L. Complete Genome Analysis Reveals Environmental Adaptability of Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacterium Thioclava nitratireducens M1-LQ-LJL-11 and Symbiotic Relationship with Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Chrysomallon squamiferum. Mar. Genom. 2023, 71, 101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, D.Y.; Tourova, T.P.; Spiridonova, E.M.; Rainey, F.A.; Muyzer, G. Thioclava pacifica gen. nov., sp. nov., a Novel Facultatively Autotrophic, Marine, Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacterium from a near-Shore Sulfidic Hydrothermal Area. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.-H.; Nam, H.-K.; Kim, K.-R.; Kim, S.-W.; Oh, D.-K. Molecular Characterization of an Aldo-Keto Reductase from Marivirga tractuosa That Converts Retinal to Retinol. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 169, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringø, E. Probiotics in Shellfish Aquaculture. Aquac. Fish. 2020, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y.; He, J.; Su, P.; Feng, D. Insights into the Planktonic to Sessile Transition in a Marine Biofilm-Forming Pseudoalteromonas Isolate Using Comparative Proteomic Analysis. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 86, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ge, Y.; Iqbal, N.M.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. Sulfitobacter alexandrii sp. nov., a New Microalgae Growth-Promoting Bacterium with Exopolysaccharides Bioflocculanting Potential Isolated from Marine Phycosphere. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2021, 114, 1091–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Yabuuchi, T.; Maeda, Y.; Nojima, D.; Matsumoto, M.; Yoshino, T. Production of Eicosapentaenoic Acid by High Cell Density Cultivation of the Marine Oleaginous Diatom Fistulifera solaris. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, L.; Dietrich, T.; Marañón, I.; Villarán, M.C.; Barrio, R.J. Producing Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: A Review of Sustainable Sources and Future Trends for the EPA and DHA Market. Resources 2020, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorgiz, R.G.; Gureev, M.A.; Zheleznova, S.N.; Gureeva, E.V.; Nechoroshev, M.V. Production of Diadinoxanthin in an Intensive Culture of the Diatomaceous Alga Cylindrotheca closterium (Ehrenb.) Reimann et Lewin. and Its Proapoptotic Activity. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2022, 58, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, S.; Zhao, W.; Kong, Q.; Zhu, C.; Fu, X.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Mou, H.; et al. Fucoxanthin from Marine Microalgae: A Promising Bioactive Compound for Industrial Production and Food Application. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 7996–8012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Bakar, M.F.; Mohd Setapar, S.H. Fucoxanthin: An Emerging Ingredient in Cosmeceutical Applications. J. Dermatol. Sci. Cosmet. Technol. 2025, 2, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.H.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, J.W.; Ki, M.-R.; Pack, S.P. Microalgae-Derived Peptide with Dual-Functionalities of Silica Deposition and Antimicrobial Activity for Biosilica-Based Biomaterial Design. Process Biochem. 2024, 146, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.-W.; Choi, Y.J. Extremophilic Microorganisms for the Treatment of Toxic Pollutants in the Environment. Molecules 2020, 25, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León, M.J.; Hoffmann, T.; Sánchez-Porro, C.; Heider, J.; Ventosa, A.; Bremer, E. Compatible Solute Synthesis and Import by the Moderate Halophile Spiribacter Salinus: Physiology and Genomics. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor, J.M.; Salvador, M.; Argandoña, M.; Bernal, V.; Reina-Bueno, M.; Csonka, L.N.; Iborra, J.L.; Vargas, C.; Nieto, J.J.; Cánovas, M. Ectoines in Cell Stress Protection: Uses and Biotechnological Production. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 782–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, M.K.; Piligian, B.F.; Olson, C.D.; Woodruff, P.J.; Swarts, B.M. Tailoring Trehalose for Biomedical and Biotechnological Applications. Pure Appl. Chem. Chim. Pure Appl. 2017, 89, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Masuzawa, N.; Kondo, K.; Nakanishi, Y.; Chida, S.; Uehara, D.; Katahira, M.; Takeda, M. A Heterodimeric Hyaluronate Lyase Secreted by the Activated Sludge Bacterium Haliscomenobacter hydrossis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2023, 87, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, J.; Saha, P.; Ganguly, J.; Paul, A.K. Production and Characterization of a Bioactive Extracellular Homopolysaccharide Produced by Haloferax sp. BKW301. J. Basic Microbiol. 2020, 60, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moopantakath, J.; Imchen, M.; Anju, V.T.; Busi, S.; Dyavaiah, M.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M.; Kumavath, R. Bioactive Molecules from Haloarchaea: Scope and Prospects for Industrial and Therapeutic Applications. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1113540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparici-Carratalá, D.; Esclapez, J.; Bautista, V.; Bonete, M.-J.; Camacho, M. Archaea: Current and Potential Biotechnological Applications. Res. Microbiol. 2023, 174, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banciu, H.L.; Enache, M.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Oren, A.; Ventosa, A. Ecology and Physiology of Halophilic Microorganisms—Thematic Issue Based on Papers presented at Halophiles 2019—12th International Conference on Halophilic Microorganisms, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 24–28 June 2019. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2019, 366, fnz250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Luna, D.; Canseco, S.P.; Morales, J.L.H.; Bolaños, T.A.; García-Sánchez, E. First Report of Halomicrobium mukohataei in Mexico and Its Biological Activity. Neotrop. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 20, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, D.; Sherkar, R.; Shirsathe, C.; Sonwane, R.; Varpe, N.; Shelke, S.; More, M.P.; Pardeshi, S.R.; Dhaneshwar, G.; Junnuthula, V.; et al. Biofabrication of Nanoparticles: Sources, Synthesis, and Biomedical Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1159193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalewicz-Kulbat, M.; Krawczyk, K.T.; Szulc-Kielbik, I.; Rykowski, S.; Denel-Bobrowska, M.; Olejniczak, A.B.; Locht, C.; Klink, M. Cytotoxic Effects of Halophilic Archaea Metabolites on Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. Microb. Cell Factories 2023, 22, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgaonkar, B.B.; Bragança, J.M. Utilization of Sugarcane Bagasse by Halogeometricum borinquense Strain E3 for Biosynthesis of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate). Bioengineering 2017, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luque, C.; Perazzoli, G.; Gómez-Villegas, P.; Vigara, J.; Martínez, R.; García-Beltrán, A.; Porres, J.M.; Prados, J.; León, R.; Melguizo, C. Extracts from Microalgae and Archaea from the Andalusian Coast: A Potential Source of Antiproliferative, Antioxidant, and Preventive Compounds. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H..; Lu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Liu, H.; Xiang, H. Identification of the Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA)-Specific Acetoacetyl Coenzyme A Reductase among Multiple FabG Paralogs in Haloarcula hispanica and Reconstruction of the PHA Biosynthetic Pathway in Haloferax volcanii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 6168–6175. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, R.U.; Paradisi, F.; Allers, T. Haloferax volcanii for Biotechnology Applications: Challenges, Current State and Perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Xu, X.-W.; Wu, M.; Huang, W.-D.; Oren, A. Isolation and Functional Expression of the Bop Gene from Halobiforma lacisalsi. Microbiol. Res. 2009, 164, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M.; Rittmann, S.K.-M.R. Haloarchaea as Emerging Big Players in Future Polyhydroxyalkanoate Bioproduction: Review of Trends and Perspectives. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2022, 4, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Singh, B.; Van Belkum, M.J.; Diep, D.B.; Chikindas, M.L.; Ermakov, A.M.; Tiwari, S.K. Halocins, Natural Antimicrobials of Archaea: Exotic or Special or Both? Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 53, 107834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari-Bafghi, M.; Babavalian, H.; Amoozegar, M.A. Isolation, Screening and Identification of Haloarchaea with Chitinolytic Activity from Hypersaline Lakes of Iran. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2019, 71, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Madrigal, A.S.; Barbachano-Torres, A.; Arellano-Plaza, M.; Kirchmayr, M.R.; Finore, I.; Poli, A.; Nicolaus, B.; De la Torre Zavala, S.; Camacho-Ruiz, R.M. Effect of Carbon Sources in Carotenoid Production from Haloarcula sp. M1, Halolamina sp. M3 and Halorubrum sp. M5, Halophilic Archaea Isolated from Sonora Saltern, Mexico. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourkarimi, S.; Hallajisani, A.; Alizadehdakhel, A.; Nouralishahi, A.; Golzary, A. Factors Affecting Production of Beta-Carotene from Dunaliella Salina Microalgae. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, M.C.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M., Jr. Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes Toward Local Food Products. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2016, 22, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, I.; Balázsné Lendvai, M.; Beke, J. The Importance of Food Attributes and Motivational Factors for Purchasing Local Food Products: Segmentation of Young Local Food Consumers in Hungary. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, A.; Varamogianni-Mamatsi, D.; Pobirk, A.Z.; Matjaž, M.G.; Cueto, M.; Díaz-Marrero, A.R.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Sveinsdóttir, K.; Catalá, T.S.; Romano, G.; et al. Marine Cosmetics and the Blue Bioeconomy: From Sourcing to Success Stories. iScience 2024, 27, 111339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Gorton, M.; Tocco, B.; Csillag, P.; Filipović, J. Chapter 10: Trends in Consumer Preference for Locally-Sourced Food Products. In Consumers and Food: Understanding and Shaping Consumer Behaviour; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Olaizola, M. Commercial Development of Microalgal Biotechnology: From the Test Tube to the Marketplace. Biomol. Eng. 2003, 20, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoozegar, M.A.; Safarpour, A.; Noghabi, K.A.; Bakhtiary, T.; Ventosa, A. Halophiles and Their Vast Potential in Biofuel Production. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DasSarma, S.; DasSarma, P. Halophiles and Their Enzymes: Negativity Put to Good Use. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015, 25, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavaš, N.; Šmuc, N.R.; Dolenec, M.; Kovač, N. The Seasonal Heavy Metal Signature and Variations in the Microbial Mat (Petola) of the Sečovlje Salina (Northern Adriatic). J. Soils Sediments 2015, 15, 2359–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavaš, N.; Défarge, C.; Gautret, P.; Joulian, C.; Penhoud, P.; Motelica, M.; Kovač, N. The Structure and Role of the “Petola” Microbial Mat in Sea Salt Production of the Sečovlje (Slovenia). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 1254–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonjak, S.; Udovič, M.; Wraber, T.; Likar, M.; Regvar, M. Diversity of Halophytes and Identification of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Colonising Their Roots in an Abandoned and Sustained Part of Sečovlje Salterns. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1847–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škrinjar, P.; Faganeli, J.; Ogrinc, N. The Role of Stromatolites in Explaining Patterns of Carbon, Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Silicon in the Sečovlje Saltern Evaporation Ponds (Northern Adriatic Sea). J. Soils Sediments 2012, 12, 1641–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkavc, R.; Gostinčar, C.; Turk, M.; Visscher, P.T.; Oren, A.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. Bacterial Communities in the ‘Petola’ Microbial Mat from the Sečovlje Salterns (Slovenia). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 75, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Rosso, G.; Peimbert, M.; Alcaraz, L.D.; Hernández, I.; Eguiarte, L.E.; Olmedo-Alvarez, G.; Souza, V. Comparative Metagenomics of Two Microbial Mats at Cuatro Ciénegas Basin II: Community Structure and Composition in Oligotrophic Environments. Astrobiology 2012, 12, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippidou, S.; Price, A.; Spencer-Jones, C.; Scales, A.; Macey, M.C.; Franchi, F.; Lebogang, L.; Cavalazzi, B.; Schwenzer, S.P.; Olsson-Francis, K. Diversity of Microbial Mats in the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans, Botswana. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingarten, E.A.; Lawson, L.A.; Jackson, C.R. The Saltpan Microbiome Is Structured by Sediment Depth and Minimally Influenced by Variable Hydration. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, I.; Weggenmann, F.; Posten, C. Cultivation of Emiliania huxleyi for Coccolith Production. Algal Res. 2018, 31, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Juárez, V.; Bennasar-Figueras, A.; Tovar-Sanchez, A.; Agawin, N.S.R. The Role of Iron in the P-Acquisition Mechanisms of the Unicellular N2-Fixing Cyanobacteria halothece sp., Found in Association with the Mediterranean Seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, P.; Rout, J. Algal Colonization on Polythene Carry Bags in a Domestic Solid Waste Dumping Site of Silchar Town in Assam. Phykos 2018, 48, e77. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.M.; Bae, E.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kang, J.-S.; Choi, Y.-E. Mixotrophic Cultivation of a Native Cyanobacterium, Pseudanabaena mucicola GO0704, to Produce Phycobiliprotein and Biodiesel. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 32, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casamayor, E.O.; Triadó-Margarit, X.; Castañeda, C. Microbial Biodiversity in Saline Shallow Lakes of the Monegros Desert, Spain. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 85, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saccò, M.; White, N.E.; Harrod, C.; Salazar, G.; Aguilar, P.; Cubillos, C.F.; Meredith, K.; Baxter, B.K.; Oren, A.; Anufriieva, E.; et al. Salt to Conserve: A Review on the Ecology and Preservation of Hypersaline Ecosystems. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 2828–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]