Abstract

The crude ethyl acetate extract of the culture of a marine sponge-associated fungus, Aspergillus unguis KUFA 0098, was tested for its capacity to inhibit the growth of ten phytopathogenic fungi, viz. Alternaria brassicicola, Bipolaris oryzae, Colletotrichum capsici, Curvularia oryzae, Fusarium semitectum, Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Phytophthora palmivora, Pyricularia oryzae, Rhizoctonia oryzae, and Sclerotium roflsii. At a concentration of 1 g/L, the crude extract was most active against P. palmivora, causing the highest growth inhibition (55.32%) of this fungus but inactive against R. oryzae and S. roflsii. At a concentration of 10 g/L, the crude extract completely inhibited the growth of most of the fungi, except for L. theobromae, R. oryzae, and S. roflsii, with 94.50%, 74.12%, and 67.80% of inhibition, respectively. The crude extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 exhibited growth-inhibitory effects against B. oryzae and P. oryzae, causative agents of brown leaf spot disease and leaf blast disease, respectively, on rice plant var. KDML105, under greenhouse conditions. Chromatographic fractionation and purification of the extract led to the isolation of four previously described depsidones, viz. unguinol (1), 2-chlorounguinol (2), 2,4-dichlorounguinol (3), and folipastatin (4), as well as one polyphenol, aspergillusphenol A (5). The major compounds, i.e., 1, 2, and 4, were tested against the ten phytopathogenic fungi. Compounds 1 and 4 were able to inhibit growth of most of the fungi, except L. theobromae, R. oryzae, and S. roflsii. Compound 1 showed the same minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values as that of carbendazim against A. brassicicola, C. capsici, C. oryzae, and P. oryzae, while compound 4 showed the same MIC values as that of carbendazim against only C. capsici and P. oryzae. Compound 2 was not active against all of the ten phytopathogenic fungi tested.

1. Introduction

Synthetic fungicides are still popular and most widely used by farmers to control plant diseases, caused by plant pathogenic fungi, due to their high efficacy and persistence []. However, the drawback of synthetic fungicides is that their continuous and excessive use can lead to high resistance of the pathogens and cause negative impacts on people’s health, environment, as well as non-target organisms []. Since pathogenic fungi are responsible for approximately 70–80% of total agricultural product loss, which is a great concern for countries with economies heavily reliant on agriculture [], managing an agricultural system in an eco-friendly and profitable manner by using fungicidal natural products that can minimize fungal infections in an agricultural ecosystem is a challenging task for sustainable agriculture []. Thus, the development and manufacture of effective, safe-to-humans, and environmentally friendly fungicides have always been the most desirable goal [].

One of the most popular approaches is the use of botanical fungicides since plant extracts normally contain a variety of compounds that can efficiently inhibit the growth of phytopathogenic fungi, probably through synergistic effects. Furthermore, the different modes of action of natural products in plant extracts can also avoid the emergence of drug resistance []. Despite these great advantages, botanical fungicides still have a number of limitations. First, they are less effective than synthetic fungicides and are not always promptly available on the market when needed. Moreover, since they are more easily degradable in the environment, they are less persistent when compared to synthetic fungicides. Other hurdles include variation in the chemical compositions of plants that are collected in different geographical locations and climatic conditions, and the need to obtain a large quantity of biomass of selected plants for large-scale production for commercialization [].

Another interesting nature-based approach is the use of endophytic fungi to protect plants against phytopathogens []. This approach has no risk of evolution of pathogen resistance compared to agrochemicals []. From this perspective, endophytic fungi can be explored for their use against phytopathogenic fungi since they have a capacity to produce a myriad of structurally diverse and biologically active secondary metabolites to protect their hosts from pathogenic microorganisms []. Despite this logic, no compounds produced by fungi have been used as commercial fungicides until now. However, it is important to mention that the syntheses of the strobilurin fungicides were inspired by the natural product, strobilurin A, which was isolated from Strobilurus tenacellus, a type of basidiomycete fungus that is often found on decaying wood []. These synthetic strobilurin fungicides and strobilurin A share a common structural feature, i.e., the methyl ester of β-methoxyacrylic acid [].

An extensive research program with the aims of preparing analogs of natural products with high levels of activity and suitable physical properties for an agricultural fungicide has led to the development of several strobilurin fungicides, including azoxystrobin, pyraclostrobin, fluoxastrobin, kresoxim-methyl, trifloxystrobin, picoxystrobin, mandestrobin, and metominostrobin []. Strobilurin fungicides are also referred to as QoI fungicides since they specifically bind to the cytochrome bc1 complex, thereby preventing electron transport and energy production via oxidative phosphorylation []. This unique and non-target specific mechanism made these fungicides broad-spectrum, rapid, and highly efficient germicidal activities. Moreover, their cost-effective and rapid degradation during plant metabolism have contributed to the large-scale use of these fungicides []. Strobilurin fungicides are globally used to combat white mold, rot, early and late leaf spot, rusts, and rice blast []. Among the strobilurin fungicides, azoxystrobin shares its biochemical mode of action with natural strobilurins. Moreover, azoxystrobin is not cross-resistant to other site-specific fungicides, such as benzimidazoles, DMIs, or phenylamides. This fungicide provides systemic, protectant, and curative action and is sold under various trade names, such as Abound, Amistar, and Quadris, which represents an effective new tool for the management of resistance, which is frequently a significant factor in the choice of fungicide products. Despite these advantages, long-term use of strobilurins has raised a serious public health concern due to their environmental contamination and non-target toxicity. Moreover, since strobilurins act on one specific site of fungal pathogens, they are susceptible to resistance. Consistently, several resistance genes from fungi treated with strobilurin have been reported [,,], suggesting that strobilurins can potentially cause long-term adverse effects to the ecosystem.

Intriguingly, due to the rich chemical diversity of the marine environment, much more attention has been paid to the screening of marine-derived fungi than their terrestrial counterparts in recent years []. For this reason, in our program of the exploitation of marine natural products for sustainable agriculture, we have screened the growth-inhibitory activity of the ethyl acetate (EtOAc) extracts of cultures of various marine-derived fungi, collected from the Gulf of Thailand, against ten phytopathogenic fungi, which cause diseases for important economic crop plants in Thailand. For example, the crude extract of a marine sponge-associated fungus, Talaromyces tratensis KUFA 0091, was tested against Alternaria padwickii (Ganguly) M.B. Ellis, Bipolaris oryzae (Breda de Haan) Shoem., Curvularia lunata (Wakk) Boedjin., and Fusarium moniliforme J. Sheld, the causative agents of rice brown spot and dirty panicle, in vitro and in greenhouse conditions. The crude extract completely inhibited the radial growth of all tested pathogens at a concentration of 10 g/L and significantly inhibited the mycelial growth of B. oryzae by 53% at 1 g/L. Under greenhouse conditions, the highest reductions in the incidences of brown spot and dirty panicle were 56.74% and 60% when treated with the crude extract at 5 g/L []. The crude extract of this fungus, at 5 g/L, was the most effective in controlling brown leaf spot, with disease reduction in the field of 45.04%, when applied twice. However, at 10g/L, it was moderately effective against rice blast, reducing its incidence by 35.11%, when applied twice under field conditions []. In another work, crude extracts of ten marine-derived fungi, viz. Emericella stellatus KUFA 0208, Eupenicillium parvum KUFA 0237, Neosartorya siamensis KUFA 0514, N. spinosa KUFA 0528, Talaromyces flavus KUFA 0119, T. macrosporus KUFA 0135, T. trachyspermus KUFA 0304, Trichoderma asperellum KUFA 0559, T. asperellum KUFA 0559, and T. harzianum KUFA 0631 were evaluated for their in vitro fungicidal activity against five rice pathogens. However, only the extracts of E. stellatus KUFA 0208 and N. siamensis KUFA 0514 exhibited the best antifungal activity, causing complete inhibition of the mycelial growth of A. padwickii, Bipalaris oryzae, F. semitectum, P. oryzae, and Rhizoctonia solani at 10 g/L [].

In this study, the crude extract of Aspergillus unguis KUFA 0098 did not only exhibit interesting growth-inhibitory activity against ten phytopathogenic fungal strains but also showed its preventive and curative effects against leaf brown spot disease, caused by B. oryzae, and leaf blast disease, caused by P. oryzae, on rice plant var. KMDL105, under greenhouse conditions. Therefore, the chemical constituents of A. unguis KUFA 0098 were isolated, characterized, and assayed for the in vitro growth-inhibitory activity against these phytopathogenic fungi.

2. Results and Discussion

Aspergillus unguis (Aspergillaceae) is a cosmopolitan fungus since it can be isolated from soils [], plants [], lichens [], and marine organisms, including algae [] and sponges []. A review article by Domingos et al. [], covering the period of 1970-2022, reported the isolation of ninety-seven secondary metabolites from the cultures of A. unguis, and a myriad of their biological activities, including antibacterial, antimalarial, larvicidal, and anti-inflammatory activities, enzyme inhibitory activities, and cytotoxicity against some cancer cell lines. Among the secondary metabolites isolated from A. unguis, depsidones constituted 30% of the total. Depsidones are an important group of polyketide secondary metabolites since they possess not only diversified structural features but also relevant biological activities [].

Since more attention has been paid to marine-derived fungi as a source of naturally occurring fungicides against phytopathogenic fungi [,,,], coupled with our interest in searching for bioactive secondary metabolites from marine-derived fungi to combat diseases of the economic crops caused by phytopathogenic fungi [], we have tested the effect of the crude EtOAc extract of the culture of A. unguis KUFA 0098, isolated from a marine sponge Hyrtios erectus, against phytopathogenic fungi.

The crude EtOAc extract of the culture of A. unguis KUFA 0098 was assayed for its capacity to inhibit the growth of ten plant pathogenic fungi, which are causative agents of economic crops in Thailand, viz. Alternaria brassicicola KUFA 1031 (black spot of Chinese Kale), B. oryzae KUFA 1032 (brown spot of rice), Colletotrichum capsici KUFA 1033 (anthracnose of chili), Curvularia oryzae KUFA 1034 (leaf spot of rice), F. semitectum KUFA 1035 (dirty panicle of rice), Lasiodiplodia theobromae KUFA 1036 (fruit rot of durian), Phytophthora palmivora KUFA 1037 (root and stem rot of durian), P. oryzae KUFA 1038 (rice blast), Rhizoctonia oryzae KUFA 1039 (sheath blight of rice), and Sclerotium roflsii KUFA 1040 (stem rot of bean). At a concentration of 1g/L, the crude EtOAc extract did not inhibit the mycelial growth of R. oryzae and S. roflsii but inhibited the mycelial growth of the rest of the tested phytopathogenic fungi to less than 50%, except for P. palmivora, for which the inhibition was 55.32%. At a concentration of 10 g/L, the crude EtOAc extract completely inhibited the mycelial growth of seven phytopathogenic fungi, viz. A. brassicicola, B. oryzae, C. capsici, C. oryzae, F. semitectum, P. palmivora, and P. oryzae; however, it was less active toward R. oryzae and S. roflsii, showing inhibition of 74.12 and 67.80% of their mycelial growth, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of the crude EtOAc extract of Aspergillus unguis KUFA 0098 on the growth of plant pathogenic fungi.

Since the crude EtOAc extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 showed 100% inhibition of the mycelial growth of B. oryzae and P. oryzae at a concentration of 10g/L, and 27.46 and 20. 67% at a concentration of 1 g/L, the crude extract was evaluated for its capacity to control brown leaf spot disease (caused by B. oryzae) and the leaf blast disease (caused by P. oryzae) on rice plants var. KMDL105 under greenhouse conditions. The reasons why we selected these two rice diseases are not only because rice is the most valuable commodity in the world but also because it takes a reasonable amount of time to perform experiments with rice plants in greenhouse conditions.

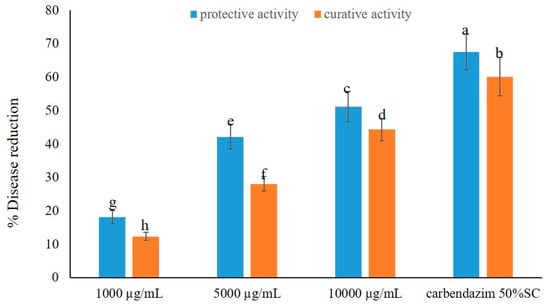

The crude EtOAc extract showed its capacity to control brown leaf spot disease in a dose-dependent manner, and without phytotoxicity (Figure 1). Moreover, the crude extract exhibited higher protective activity than curative activity in disease reduction. Application of the crude extract at the highest dose, i.e., at 10,000 µg/L, displayed remarkable fungicidal activity, causing 51.23 and 44.32% reduction in protective and curative activity tests, respectively. Moreover, even at a concentration of 5000 µg/L, the crude extract showed moderate activity against the disease, reducing the disease incidence by 42.16 and 28.09%, respectively. However, at a concentration of 1000 µg/L, the crude extract displayed low activity, causing less than 20% of disease reduction in both activity tests. Tellingly, the application of a standard fungicide, carbendazim, exerted a higher disease reduction in both activity tests, viz. ca. 70% in protective activity and ca. 60% in curative activity (Figure 1). The effects of the crude extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 against brown leaf spot disease under greenhouse conditions are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Effects of the crude extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 against brown leaf spot disease under greenhouse conditions. Means ± SD, followed by the same letter, do not significantly differ at p < 0.05 when analyzed using Duncan’s test of one-way ANOVA.

Figure 2.

Effects of the crude extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 against brown leaf spot disease under greenhouse conditions when applied before pathogen inoculation. A = control; B = 1000 µg/mL; C = 5000 µg/mL; and D = 10,000 µg/mL.

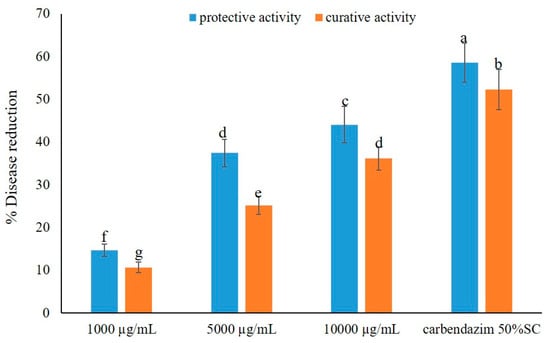

The effects of the crude extract against the leaf blast disease, under greenhouse conditions, were similar to those of brown leaf spot disease. The crude extract showed a reduction in leaf blast disease in a dose-dependent manner and displayed more potent protective activity than curative activity. However, it exhibited lower activity against the leaf blast test when compared to the brown leaf spot test. Application of the crude extract at the highest dose, i.e., 10,000 µg/mL, exhibited potent activity, causing 44.09 and 36.17% disease reduction in the protective and curative activity tests, respectively. Application of the crude extract at lower concentration, at 5000 µg/mL, showed moderate activity against the disease, reducing the disease incidence by 37.43% and 25.15%, respectively. However, the extract displayed low activity when applied at a concentration of 1000 µg/mL, causing less than 15% of disease reduction in both activity tests. Similarly to brown leaf spot, the application of a fungicide, carbendazim, also exerted a higher disease reduction in both activity tests, viz. ca. 60% in protective activity and ca. 55% in curative activity (Figure 3). The effects of the crude extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 against leaf blast disease under greenhouse conditions are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Effects of the crude extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 against leaf blast disease under greenhouse conditions. Means ± SD, followed by the same letter, do not significantly differ at p < 0.05 when analyzed using Duncan’s test of one-way ANOVA.

Figure 4.

Effects of the crude extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 against leaf blast disease under greenhouse conditions when applied before pathogen inoculation. A = control; B = 1000 µg/mL; C = 5000 µg/mL; and D =10,000 µg/mL.

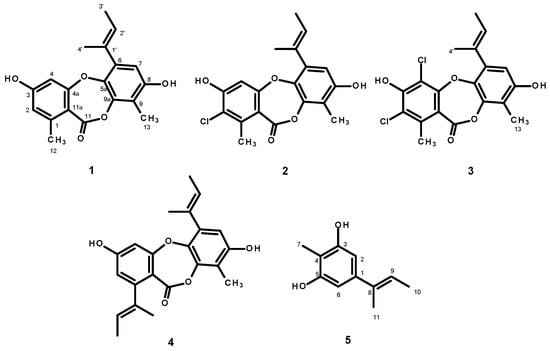

Since the crude EtOAc extract showed promising results, inhibiting completely the growth of seven out of ten phytopathogenic fungi, at a concentration of 10g/L (Table 1), we proceeded with the isolation and characterization of the constituents of the crude EtOAc extract to isolate the compounds and to test them individually against these ten phytopathogenic fungi in order to identify the compounds responsible for the activity of the crude extract. The EtOAc crude extract was first partitioned to CHCl3, and after evaporation of the solvent by reduced pressure, the crude CHCl3 extract was obtained. Fractionation of the CHCl3 portion by column chromatography of silica gel occurred, followed by purification by crystallization, preparative TLC and Sephadex LH-20 column, furnished unguinol (1) [], 2-chlorounguinol (2) [], and folipastatin (4) [] as major compounds (with yields of 1.72, 1.43, and 1.21%, respectively), together with 2,4-dichlorounguinol (3, 0.05%) [], and aspergillusphenol A (5, 0.02%) [] as minor compounds (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Structures of unguinol (1), 2-chlorounguinol (2), 2,4-dichlorounguinol (3), folipastatin (4), and aspergillusphenol A (5), isolated from the culture extract of Aspergilus unguinol KUFA 0098.

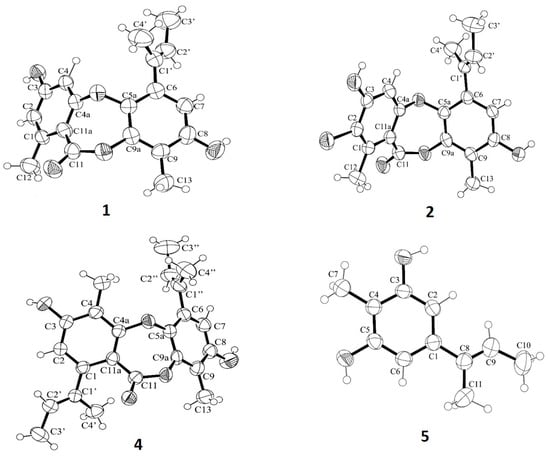

The structures of 1-5 were elucidated by an interpretation of their 1D (1H, 13C, DEPT) and 2D NMR (COSY, HSQC and HMBC) (Figures S1–S25 and Tables S1–S5), as well as a comparison of their NMR data with those previously reported. The structures of 2 and 3 were confirmed by (+)-HRESIMS spectra (Figures S26 and S27). The crystal structures of 1, 2, 4, and 5 were obtained, for the first time, by an X-ray diffractometer equipped with CuKα radiation, and their Ortep views are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

ORTEP views of unguinol (1), 2-chlorounguinol (2), folipastatin (4), and aspergillusphnol A (5).

Since the three depsidones, viz. 1, 2, and 4, were isolated in high quantities from the crude EtOAc extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098, they were assayed for in vitro antifungal activity against the ten phytopathogenic fungi, using carbendazim as a positive control. Table 2 shows that 1 was the most active compound, showing similar growth-inhibitory activity to that of the positive control, carbendazim (MIC = 125 μg/mL), against A. brassicicola, C. capsici, C. oryzae, and P. oryzae, (MIC = 125 μg/mL), and it was two folds less active than carbenazim against B. oryzae (MIC = 125 μg/mL), F. semitectum (MIC = 250 μg/mL), and P. palmivora (MIC = 125 μg/mL) but inactive (MIC ˃ 500 μg/mL) against L. theobromae, R. oryzae, and S. roflsii. On the other hand, 4 was more active towards less phytopathogenic fungi than 1. Compound 4 showed comparable inhibitory activity against C. capsici and P. oryzae (MIC = 125 μg/mL) with that of carbendazim (MIC = 125 μg/mL), but it was two folds less active than carbendazim against P. palmivora (MIC = 125 μg/mL) and F. semitectum (MIC = 250 μg/mL), and inactive against the rest of the fungi (MIC = 500 ˃ μg/mL). Intriguingly, 2 was inactive against all the phytopathogenic fungi tested (MIC = 500 ˃ μg/mL) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of Aspergillus unguis KUFA 0098 on the growth of the ten plant pathogenic fungi.

Interestingly, the introduction of bulky groups to the depsidone scaffold slightly affected the growth-inhibitory activity of the depsidones since 4, an analog of 1, with the but-2-en-2-yl group on C-1 and the methyl group on C-4, displayed a similar growth-inhibitory activity to that of 1, except for A. brassicicola and C. oryzae. On the other hand, the introduction of a chlorine atom to C-2 of 1 dramatically decreased its growth-inhibitory activity, as evidenced by the lack of activity of 2 against all the phytopathogenic fungi tested. It is interesting to note that all of the three depsidones did not inhibit the growth of three phytopathogenic fungi, viz. L. theobromae, R. oryzae, and S. roflsii.

Intriguingly, our findings are in contrast to those reported by Sadorn et al., who found that the chlorodepsidones, viz. emerguisin A (7-chloro), 2-chlorounguinol (2-chloro), and nornidulin (2,4,7-trichloro), isolated from the culture of the endophytic fungus, A. unguis BCC54176, which was obtained from a leaf of coriander, showed anti-phytopathogenic activity against C. acutatum, with the same MIC value (3.13 μg/L), which is two folds less active than the positive control, amphotericin B (MIC = 1.56 μg/L). On the other hand, nornidulin (MIC = 25 μg/L) and 2-chlorounguinol (MIC = 12.5 μg/L) were less active against A. brassicicola, while emerguisin A was inactive (MIC ˃ 50 μg/L) against this pathogenic fungus. Conversely, folastatin was inactive against both A. brassicicola and C. acutatum, while unguinol was inactive against C. acutatum but slightly active against A. brassicicola [].

The discrepancies of the results obtained by us in this work and by Sadorn et al. [] could be due to either the different methods used to determine the growth-inhibitory activity of the compounds or the source and type of the phytopathogenic fungal strains. While the CLSI method is used in this work to determine MICs of the compounds, with carbendazim as a positive control, Sadorn et al. [] used the 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate (CFDA) fluorometric assay, with amphotericin B as a positive control. The source of the phytopathogenic fungi can also influence the obtained results. While Sadorn et al. [] used commercially available strains, i.e., A. brassicicola (BCC42724) and C. acutatum (BCC58146), we used the strains of the pathogenic fungi isolated from the diseased host plants with their pathogenicity confirmed in our laboratory.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at ambient temperature on a Bruker AMC instrument (Bruker Biosciences Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) operating at 300 and 75 MHz, respectively. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were measured with a Waters Xevo QToF mass spectrometer (Waters Corporations, Milford, MA, USA) coupled to a Waters Aquity UPLC system. A Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) Silica gel GF254 was used for preparative TLC, and a Merck Si gel 60 (0.2–0.5 mm) was used for column chromatography. LiChroprep silica gel and Sephadex LH-20 were used for column chromatography.

3.2. Fungal Strain

The strain KUFA 0098 was isolated from the marine sponge, Hyrtios erectus, which was collected by scuba diving at a depth of 15-20 m, from a coral reef at Samae San Island (12°34′36.64″ N 100°56′59.69″ E), Chonburi province, Thailand, in April 2016. The sponge was washed with sterilized seawater three times, dried on a sterile filter paper under sterile aseptic condition, and cut into small pieces (5 × 5 mm). Four pieces of the sponges were placed on Petri dish plates containing 15 mL of potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium mixed with 300 mg/L of streptomycin sulfate and incubated at room temperature for 7 d. The hyphal tips emerging from the pieces of sponges were individually transferred onto a PDA slant and maintained as pure cultures at Kasetsart University Fungal Collection, Department of Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand.

The fungal strain KUFA 0098 was identified as Aspergillus unguis, based on morphological characteristics. This identification was confirmed by molecular techniques using ITS primers. DNA was extracted from young mycelia following a modified Murray and Thompson method []. The universal primer pairs ITS1 and ITS4 were used for ITS gene amplification []. PCR reactions were conducted on Thermal Cycler, and the amplification process consisted of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 34 cycles at 95 °C for 1 min (denaturation), at 55 °C for 1 min (annealing), and at 72 °C for 1.5 min (extension), followed by final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were examined by agarose gel electrophoresis (1% agarose with 1×TBE buffer) and visualized under UV light after staining. DNA sequencing analyses were performed using the dideoxyribonucleotide chain termination method [] by Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea). The DNA sequences were edited using FinchTV software (version 1.4) and submitted to the BLAST program for alignment and compared with that of fungal species in the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ accessed on 20 December 2020). Its gene sequences were deposited in GenBank with the accession number PV719693.

3.3. Extraction and Isolation of the Compounds

The mycelial plugs of A. unguis KUFA 0098 were transferred into 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 200 mL of potato dextrose broth (PDB) and incubated at room temperature on a rotary shaker at 120 rpm for 7 d to prepare mycelial suspension. Fifty 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks, each containing 300 g of sterile cooked rice, were then inoculated with 20 mL of mycelial suspension in each flask and incubated at room temperature for 30 d, after which 500 mL of EtOAc was added to each flask and macerated for 7 d and then filtered with filter paper (Whatman No.1) to produce the organic solutions, which were combined and evaporated under reduced pressure to furnish a crude EtOAc extract (300 g). The crude EtOAc extract was then dissolved in EtOAc (300 mL) and washed with H2O (3 × 500 mL), and the EtOAc solution was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure to obtain 270.2 g of the crude EtOAc extract. The crude EtOAc extract was then dissolved in 500 mL of CHCl3 and filtered. The CHCl3 solution was evaporated under reduced pressure to obtain 157.3 g of a crude CHCl3 extract. The crude CHCl3 extract was applied on a column of silica gel (400 g) and eluted with mixtures of petrol/CHCl3 and CHCl3/Me2CO, wherein 250 mL fractions (Frs) were collected as follows: Frs 1–83 (CHCl3–petrol, 7:3), 84–184 (CHCl3–petrol, 9:1), 185–186 (CHCl3), 187–232 (CHCl3-Me2CO, 9:1), and 233–255 (CHCl3-Me2CO, 8:2). Frs 87–115 were combined (4.42 g) and crystalized in CHCl3 to give 1.21 g of 2. Frs.116–146 were combined (4.45 g) and crystalized in CHCl3 to give 1.18 g of white crystals of 2. Frs. 147–184 were combined (2.31 g) and crystalized in CHCl3 to give 912.2 mg of 2. Frs. 185–191 were combined (1.12 g) and crystalized in CHCl3 to give 543.8 mg of 2. The mother liquor of Frs 87–115 (3.35 g) was applied on a column chromatography of silica gel (30 g) and eluted with mixtures of petrol and CHCl3, wherein 150 mL subfractions (sfrs) were collected as follows: sfrs 19–41 (CHCl3–petrol, 3:7), sfrs 42–46 (CHCl3–petrol, 3:7), sfrs 47–53 (CHCl3–petrol, 3:7), sfrs 54–61 (CHCl3–petrol, 3:7), sfrs 62–79 (CHCl3–petrol, 5:5), sfrs 80–87 (CHCl3–petrol, 7:3), and sfrs 88–99 (CHCl3–petrol, 9:1). Sfrs 62–87 were combined (383.6 mg) and purified by preparative TLC of silica gel G254 and eluted with CHCl3-Me2CO-petrol, 90:5:5, to produce 12.2 mg of 3. The mother liquor of frs.116 was applied on a column chromatography of silica gel (30 g) and eluted with mixtures of petrol and CHCl3, wherein 150 mL sfrs were collected as follows: sfrs 5–14 (CHCl3–petrol, 3:7), sfrs 15–68 (CHCl3–petrol, 3:7), sfrs 69–79 (CHCl3–petrol, 5:5), and Sfrs 80–92 (CHCl3–petrol, 7:3). Sfrs 5–41 were combined and crystallized in CHCl3 to give 483.3 mg of 5. Frs. 192 and 193 were combined (9.54 g) and crystalized in CHCl3 to give 3.28 g of 4. Frs 194–198 were combined (7.25 g) and crystallized in CHCl3 to give 4.64 g of 1.

3.4. X-Ray Crystallography

Single crystals were mounted on cryoloops using paratone, X-ray diffraction data were collected at 293 K with a Gemini PX Ultra equipped with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å). The structures were solved by direct methods using SHELXS-97 and refined with SHELXL-97 []. Non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. Hydrogen atoms were either directly found from difference Fourier maps and refined freely with isotropic displacement parameters or were placed at their idealized positions using appropriate HFIX instructions in SHELXL and included in subsequent refinement cycles. Full details of the data collection and refinement and tables of atomic coordinates, bond lengths and angles, and torsion angles are deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

3.4.1. Unguinol (1)

The crystal was triclinic, space group P-1, with a unit cell volume of 1898.8(2) Å3. The unit cell dimensions were a = 11.7197(6) Å, b = 12.0288(9) Å, and c = 15.3894(6) Å, with angles α = 82.936(4)°, β = 87.858(4)°, and γ = 61.903(6)° (uncertainties in parentheses). The asymmetric unit contained one molecule of the compound and one solvent molecule of chloroform. The refinement converged with R (all data) = 14.06% and wR2 (all data) = 36.74%. Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre deposition number CCDC 2452372.

3.4.2. 2-Chlorounguinol (2)

The crystal was monoclinic, space group P 21/c, with a unit cell volume of 1844.63(17) Å3. The unit cell dimensions were a = 9.9458(5) Å, b = 18.7156(7) Å, and c = 11.0150(5) Å, with β = 115.886(6)° (uncertainties in parentheses). The asymmetric unit contained one molecule of the compound and one water molecule. The refinement converged with R (all data) = 9.96% and wR2 (all data) = 26.12%. Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre deposition number CCDC 2452435.

3.4.3. Folipastatin (4)

The crystal was triclinic, space group P-1, with a unit cell volume of 2503.9(2) Å3. The unit cell dimensions were a = 9.4348(5) Å, b = 14.8071(6) Å, and c = 19.8438(8) Å, with angles α = 71.171(4)°, β = 83.665(4)°, and γ = 72.630(4)° (uncertainties in parentheses). The asymmetric unit contained two molecules of the compound. The refinement converged with R (all data) = 17.16% and wR2 (all data) = 40.88%. Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre deposition number CCDC 2451960.

3.4.4. Aspergillusphenol A (5)

The crystal was monoclinic, space group P 21/n, with a unit cell volume of 973.31(7) Å3. The unit cell dimensions were a = 8.0419(4) Å, b = 12.7973(4) Å, and c = 9.9934(4) Å, with β = 108.850(5)° (uncertainties in parentheses). The asymmetric unit contained one molecule of the compound. The refinement converged with R (all data) = 6.72% and wR2 (all data) = 14.84%. Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre deposition number CCDC 2451810.

3.5. In Vitro Antifungal Activity Bioassays Against Plant Pathogenic Fungi

3.5.1. Pathogen Isolation and Pathogenicity Test

All phytopathogen strains, viz. Alternaria brassicicola KUFA 1031, Bipolaris oryzae KUFA 1032, Colletotrichum capsici KUFA 1033, Curvularia oryzae KUFA 1034, Fusarium semitectum KUFA 1035, Lasiodiplodia theobromae KUFA 1036, Phytophthora palmivora KUFA 1037, Pyricularia oryzae KUFA 1038, Rhizoctonia oryzae KUFA 1039, and Sclerotium roflsii KUFA1040, were isolated from diseased host plants and identified by morphological analysis. Their pathogenicity test was conducted according to the method described by Agrios [] on the host plants under greenhouse conditions, as previously reported [,,].

3.5.2. In Vitro Antifungal Activity of the Crude EtOAc Extract of A. unguinol KUFA 0098 Against Plant Pathogenic Fungi

The in vitro growth-inhibitory activity of the crude EtOAc extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098, against ten plant pathogenic fungi, was evaluated using the dilution plate technique, according to the previously described method []. Briefly, the crude EtOAc extract (1.0 g) was dissolved in 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and serially diluted with 9 mL of H2O to obtain stock solutions of 100 and 10 g/L. In total, 1 mL of each stock solution was added to 9 mL of warm PDA, thoroughly mixed by a vortex mixer, and then poured into Petri dishes to give medium plates amended with the crude extract with concentrations of 10g/L and 1 g/L, respectively. Each pathogen strain was cultured on a PDA for 7 d, at 28 ± 2 °C, and a mycelial plug of 0.5 cm in diameter of each pathogen was placed on the center of the PDA plates containing the crude extract, which were incubated at room temperature for 14 d. The PDA plate void of the crude extract was used as a negative control. The inhibition levels were calculated using the formula [(x − y)/x] × 100, where x is a diameter of the colony growth of the plant pathogenic fungi in the negative control, and y is a diameter of the colony growth of the plant pathogenic fungi in the presence of the crude extract. Each treatment was performed with five replications and repeated three times independently. The mean inhibition levels and standard deviations were calculated from five replications and three repetitions. Data were subjected to analysis of variance, and means were subsequently compared using Duncan’s multiple range test (p ˂ 0.05) in the SPSS version 19 statistical program (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY, USA).

3.5.3. In Vitro Antifungal Assays of Unguinol (1), 2-Chlorounguinol (2), and Folipastatin (4) Against Plant Pathogenic Fungi

The antifungal activity of unguinol (1), 2-chlorounguinol (2), and folipastatin (4), major secondary metabolites isolated from the culture extract of the marine-derived A. unguis KUFA 0098, against the plant pathogens was assayed according to the CLSI recommendation by testing the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) []. Each pathogen strain was cultured on PDA for 14 d at 28 ± 2 °C. The spores of the pathogenic fungi were collected by gently scraping from the mycelium by a sterile loop to add to the PDB and adjust it to 106 spores/mL with PDB. In total, 1 mg of each compound was dissolved in 100 µL of 10% DMSO, and then 900 µL of distilled H2O was added to prepare a stock solution of 1000 µg/L. Two-fold serial dilutions of the stock solution by PDB mixed with a spore suspension provided the tested concentrations at 500, 250, and 125 µg/L. Each treatment was loaded with 200 µL of the compounds per well into 96-well U-shaped sterile polystyrene plates with five wells per treatment and subsequently incubated for 7 d at 25 °C. The lowest concentration that inhibited visible growth was determined as an MIC of the compound. Carbendazim (Sigma-Aldrich®, St. Louis, MI, USA), at the same concentration, was used as a positive control.

3.6. Effects of the Crude Extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 Against Rice Leaf Diseases Under Greenhouse Conditions

3.6.1. Preparation of the Solutions of the Crude Extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098

The crude EtOAc extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 (10 g) was thoroughly dissolved in 10 mL of DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and then 990 mL of H2O, with 1% Tween 80 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), was added to obtain a concentration of 10,000 µg/L. This solution was diluted with distilled H2O to obtain concentrations of 5000 and 1000 µg/L for the experiments.

3.6.2. Preparation of Spore Suspension of B. oryzae and P. oryzae

B. oryzae and P. oryzae were cultured separately on PDA plates for 14 d at 28 ± 2 °C. Then, 20 mL of sterile H2O was poured into each PDA plate, and spores were gently scraped from mycelium using a sterile glass rod. The spore suspension of each fungus was then passed through three layers of sterile cheesecloth to remove fungal mycelium. Then, the spore suspension was diluted with sterile H2O and adjusted using a hematocytometer to obtain 106 spores/mL.

3.6.3. Preparation of Rice Seedlings

Four seven-day-old rice seedlings (rice plant var. KDML 105) of the same height and vigor were transplanted to a plastic pot (25 cm diam. × 22 cm in height) containing sterile clay soil (1500 g). The pots were placed in a greenhouse at 30 ± 2 °C in a completely randomized design (Figure S28). The pots were watered daily.

3.6.4. Evaluation of the Effects of the Crude Extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 Against Leaf Brown Spot Disease and Leaf Blast Disease Under Greenhouse Conditions

The preventive and curative activities of the crude extract of A. unguis KUFA 0098 against leaf brown spot disease, on rice plant var. KMDL105, were evaluated under greenhouse conditions, following the previously described procedure [].

For the evaluation of the preventative activity, 40-day-old rice plants were sprayed with crude extract solutions at 1000 µg/L, 5000 µg/L, and 10,000 µg/L, 30 mL per pot. Distilled H2O and aqueous solution of carbendazim 50% W/V suspension concentrate (SC), at 1.5 mL/L, both containing 1% Tween 80, were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. The sprayed rice plants were left to dry for 2h, after which they were inoculated with 30 mL of spore suspension (containing 1%Tween 80) of B. oryzae (in the case of leaf brown spot disease) or P. oryzae (in the case of leaf blast disease), at 106 spores/mL/pot. Each treatment consisted of five pots (two replications) with two repetitions.

For the evaluation of the curative activity, the 30-day-old rice plants were first inoculated with 30 mL of spore suspension (containing 1% Tween 80) of B. oryzae at 106 spores/mL/pot. Then, each pot was covered with a transparent plastic bag for 24 h, after which the rice plants were sprayed with the crude extract solutions at 1000 µg/L, 5000 µg/L, and 10,000 µg/L, 30 mL per pot. Distilled H2O and aqueous solution of carbendazim 50% W/V SC, at 1.5 mL/L, both containing 1% Tween 80, served as negative and positive controls, respectively. Each treatment consisted of five pots (two replications) with two repetitions.

Ten days after the inoculation, ten leaves of the rice plants from the middle of the pot were randomly collected for the evaluation of the disease incidence. The numbers of brown leaf spots on each leaf were counted and the average in each treatment was calculated and compared with the control groups. The percentage of disease reduction was calculated as follows:

where R1 is the average of the number of diseased spots per leaf in the plants with treatment, and R2 is the average of the number of diseased spots per leaf in the negative control.

% disease reduction = [(R1 × 100)/R2] − 100

3.7. Statistical Analysis

All experiments in this study were conducted at least twice. Since there were no significant differences between the repetitions of each experiment, the data from each experiment were pooled and analyzed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) method. Means were compared using Duncan’s post hoc test (p < 0.05) using SPSS version 19 (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY, USA).

4. Conclusions

The present work reveals the capacity of the marine-derived fungus, A. unguis KUFA 0098, to produce compounds with growth-inhibitory activity against a variety of phytopathogenic fungi that cause diseases in economically important crops both in vitro and in vivo (in greenhouse conditions). Among the three major compounds isolated, unguinol and folipastatin displayed growth inhibition of 80% of the phytopathogenic fungi tested. These results led to the conclusion that these two compounds are responsible for the inhibitory activity of the crude EtOAc extract against eight out of ten phytopathogenic fungi tested and also revealed that depsidone is an important scaffold for anti-phytopathogenic fungal activity. Marine-derived fungi have been proven to be a prolific source of bioactive natural products, and thus the compounds produced by marine-derived fungi can have a great potential to combat not only human diseases but also plant diseases. Therefore, testing compounds produced by marine-derived fungi to search for natural fungicides to control plant diseases is a challenging task. Marine-derived fungal compounds have several advantages over plant-derived compounds. For example, they can be produced on a large scale, using a reactor, and in a shorter amount of time compared to phytochemicals. Moreover, different compounds with the same scaffolds can be obtained by using the OSMAC (One Strain Many Compounds) approach or semi-synthesis, which can lead to obtaining compounds with improved efficacy and less toxicity for use in eco-friendly and sustainable agriculture.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/md23120461/s1. Figures S1–S25: 1D and 2D NMR spectra of compounds 1–5. Figures S26 and S27: HRMS data for compounds 2 and 3. Figure S28: The design of rice seedling pot arrangement in the greenhouse. Tables S1–S5: 1H and 13C NMR data of compounds 1–5.

Author Contributions

A.K., E.S. and T.D. conceived, designed the experiments and elaborated the manuscript; D.I.C.P. performed isolation and purification of the compounds; T.D. collected, isolated, identified and cultured the fungus; D.K. and T.D. performed in vitro antifungal assays and experiments in greenhouse conditions. L.G. performed X-ray analysis; S.M. provided HRMS; A.M.S.S. provided NMR spectra. A.K. edited and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FCT-Foundation for Science and Technology within the scope of UIDB/04423/2020 and UIDP/04423/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, X.; Zhao, H.; Chen, X. Screening of marine bioactive antimicrobial compounds for plant pathogens. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santra, H.K.; Banerjee, D. Natural products as fungicide and their role in crop protection. In Natural Bioactive Products in Sustainable Agriculture; Singh, J., Yadav, A.N., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2020; pp. 131–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deresa, E.M.; Diriba, T.F. Phytochemicals as alternative fungicides for controlling plant diseases: A comprehensive review of their efficacy, commercial representatives, advantages, challenges for adoption, and possible solutions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umetsu, N.; Shirai, Y. Development of novel pesticides in the 21st century. J. Pestic. Sci. 2020, 45, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuping, D.S.S.; Eloff, J.N. The use of plants to protect plants and food against fungal pathogens: A review. Afri. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 14, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Yadav, P.K.; Sarhan, A.T. Botanical fungicides; current status, fungicidal properties and challenges for wide scale adoption: A review. RFNA 2021, 2, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Dai, C.; Liu, X. Mechanisms of fungal endophytes in plant protection against pathogens. Afri. J. Microbiol. Res. 2010, 4, 1346–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhl, J.; Kolnaar, R.; Ravensberg, W.J. Mode of action of microbial biological control agents against plant diseases: Relevance beyond efficacy. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Li, X.Q.; Zhao, D.L.; Zhang, P. Antifungal secondary metabolites produced by the fungal dndophytes: Chemical diversity and potential use in the development of biopesticides. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 689527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anke, T.; Oberwinkler, F.; Steglich, W.; Schramm, G. The strobilurins new antifungal antibiotics from the basidiomycete Strobilurus tenacellus (Pers.ex Fr.) Sing. J. Antibiot. 1997, 30, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balba, H. Review of strobilurin fungicide chemicals. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2007, 42, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandelwal, A.; Gupta, S.; Gajbhiye, V.T.; Varghese, E. Degradation of kresoximmethyl in soil: Impact of varying moisture, organic matter, soil sterilization, soil type, light and atmospheric CO2 level. Chemosphere 2014, 111, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, E.T.; Lopes, I.; Pardal, M.A. Occurrence, fate and effects of azoxystrobin in aquatic ecosystems: A review. Environ. Int. 2013, 53, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhan, H.; Bhatt, P.; Chen, S. An overview of strobilurin fungicide degradation: Current status and future perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartett, D.W.; Clough, J.M.; Godfrey, C.R.A.; Godwin, J.R.; Hall, A.A.; Heaney, S.P.; Heaney, S.P.; Maund, S.J. Understanding the strobilurin fungicides. Pestic. Outlook. 2001, 12, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Köeller, W. Characterization of the mitochondrial cytochrome B gene from Venturia inaequalis. Curr. Genet. 1997, 32, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.S.; Auclair, C.; Gredt, M.; Leroux, P. First occurrence of resistance to strobilurin fungicides in Microdochium nivale and Microdochium majus from French naturally infected wheat grains. Pest Manag. Sci. 2009, 65, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piszczek, J.; Pieczul, K.; Kiniec, A. First report of G143A strobilurin resistance in Cercospora beticola in sugar beet (beta vulgaris) in Poland. J. Plant. Dis. Protect. 2017, 125, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.; Nakayama, D.G.; Sousa, E.; Pinto, E. Marine-derived compounds and prospects for their antifungal application. Molecules 2020, 25, 5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dethoup, T.; Kaewsalong, N.; Songkumorn, P.; Jantasorn, A. Potential application of a marine-derived fungus, Talaromyces tratensis KUFA0091 against rice diseases. Biol. Control. 2018, 119, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dethoup, T.; Jantasorn, A.; Kaewsalong, N. Efficacy of the antagonistic fungus Talaromyces tratensis KUFA 0091 in controlling rice blast and brown leaf spot diseases in field trials. Agr. Nat. Resour. 2022, 56, 697–704. Available online: https://li01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/anres/article/view/256131 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Chalearmsrimuang, T.; Suasa-ard, S.; Jantasorn, A.; Dethoup, T. Effects of marine antagonistic fungi against plant pathogens and rice growth promotion activity. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 16, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phainuphong, P.; Rukachaisirikul, V.; Phongpaichit, S.; Sakayaroj, J.; Kanjanasirirat, P.; Borwornpinyo, S.; Akrimajirachoote, N.; Yimnual, C.; Muanprasat, C. Depsides and depsidones from the soil-derived fungus Aspergillus unguis PSU-RSPG204. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 5691–5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorn, K.; Saepua, S.; Bunbamrung, N.; Boonyuen, N.; Komwijit, S.; Rachtawee, P.; Pittayakhajonwut, P. Diphenyl ethers and depsidones from the endophytic fungus Aspergillus unguis BCC54176. Tetrahedron 2022, 105, 132612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Gao, Y.; Liu, C.Y.; Sun, C.J.; Zhao, Z.T.; Lou, H.X. Asperunguisins A-F, cytotoxic asperane sesterterpenoids from the endolichenic fungus Aspergillus unguis. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.C.; Bao, H.Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Nie, Y.Y.; Yang, J.M.; Hong, P.Z.; Zhang, Y. Depsidone derivatives and a cyclopeptide produced by marine fungus Aspergillus unguis under chemical induction and by its plasma induced mutant. Molecules 2018, 23, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sureram, S.; Wiyakrutta, S.; Ngamrojanavanich, N.; Mahidol, C.; Ruchirawat, S.; Kittakoop, P. Depsidones, aromatase inhibitors and radical scavenging agents from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus unguis CRI282-03. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingos, L.T.S.; Martins, R.S.; Lima, L.M.; Ghizelini, A.M.; Ferreira-Pereira, A.; Cotinguiba, F. Secondary metabolites diversity of Aspergillus unguis and their bioactivities: A potential target to be explored. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, M.T.; Ghazawi, K.F.; Samman, W.A.; Alhaddad, A.A.; Mohamed, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.R.M. Recent advances on natural depsidones: Sources, biosynthesis, structure-activity relationship, and bioactivities. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, D.; Tian, X.Y.; Cao, F.; Li, Y.Q.; Zhang, C.S. Anti-phytopathogenic and cytotoxic activities of crude extracts andsecondary metabolites of marine-derived fungi. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Han, X.; Wang, D.; Liu, M.; Gou, J.; Peng, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Cao, F.; Zhang, C. Bioactive 3-decalinoyltetramic acids derivatives from a marine-derived strain of the fungus Fusarium equiseti D39. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Meng, Z.H.; Mu, X.; Yue, Y.F.; Zhu, H.J. Absolute configuration of bioactive azaphilones from the marine-derived fungus Pleosporales sp. CF09-1. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Mandi, A.; Li, X.M.; Du, F.Y.; Wang, J.N.; Li, X.; Kurtan, T.; Wang, B.G. Varioxepine A, a 3H-oxepine-containing alkaloid with a new oxa-cage from the marine algal-derived endophytic fungus Paecilomyces variotii. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4834–4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaram, R.; Dethoup, T.; Machado, F.P.; Gales, L.; Kumla, D.; Ghoran, S.H.; Sousa, E.; Mistry, S.; Silva, A.M.S.; Kijjoa, A. Pentaketides and 5-p-hydroxyphenyl-2-pyridone derivative from the culture extract of a marine sponge-associated fungus Hamigera avellanea KUFA0732. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, N.; Nakajima, S.; Satoh, Y.; Yamazaki, M.; Kawai, K. Studies on fungal products. XVIII. Isolation and structures of a new fungal depsidone related to nidulin and a new phthalide from Emericella unguis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 1970–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureram, S.; Kesornpun, C.; Mahidol, C.; Ruchirawat, S.; Kittakoop, P. Directed biosynthesis through biohalogenation of secondary metabolites of the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus unguis. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaiklay, S.; Rukachaisirikul, V.; Aungphao, W.; Phongpaichit, S.; Sakayaroj, J. Depsidone and phthalide derivatives from the soil-derived fungus Aspergillus unguis PSU-RSPG199. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 4348–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.G.; Thompson, W.F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980, 8, 4321–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 72, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrios, G.N. Parasitism and disease development. In Plant Pathology Pathology, 5th ed.; Agrios, G.N., Ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kongcharoen, N.; Kaewsalong, N.; Dethoup, T. Efficacy of fungicides in controlling rice blast and dirty panicle diseases in Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nujthet, T.; Jantasorn, A.; Dethoup, T. Biological efficacy of marine-derived Trichoderma in controlling chili anthracnose and black spot disease in Chinese kale. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 166, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Methods for Determining Bactericidal Activity of Antimicrobial Agents; approved guideline; CLSI document M26-A; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).