Abstract

Background and Objectives: Chronic knee pain (cKP) affects approximately 25% of adults worldwide, with prevalence increasing over recent decades. While conventional treatments have clinical limitations, several types of electrical stimulation have been suggested to improve patients’ quality of life. The electrical stimulation literature contains inadequate patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) data. Encouraging preliminary H-Wave® device PROMs results for chronic neck, shoulder, and low back pain have previously been published. This PROMs study’s goal is to similarly assess the efficacy of H-Wave® device stimulation (HWDS) in patients with differing knee disorders. Materials and Methods: This is an independent, retrospective, observational cohort study analyzing H-Wave® PROMs data, prospectively and sequentially collected over 4 years. In total, 34,192 pain management patient final surveys were screened for participants who were at least 18 years old, used H-Wave® for any knee-related disorder, reporting chronic pain from 90 to 730 days, with device treatment duration from 22 to 365 days. PROMs included effects on function, pain, sleep quality, need for medications, ability to work, and patient satisfaction; additional data includes gender, age (when injured), chronicity of pain, prior treatments, and frequency and length of device use. Results: PROMs surveys from 34,192 HWDS patients included 1143 with “all knee”, 985 “knee injury”, and 124 “knee degeneration” diagnoses. Reported improvements in function/ADL (96.51%) and work performance (84.63%) were significant (p < 0.0001), with ≥20% pain relief in 86.76% (p < 0.0001), improving 2.96 points (average 0–10 NRS). Medication use decreased (69.85%, p = 0.0008), while sleep improved (55.33%) in knee injury patients. Patient satisfaction measures exceeded 96% (p < 0.0001). Subgroup analysis suggests that longer device use and shorter pain chronicity resulted in increased (p < 0.0001) HWDS benefits. Conclusions: HWDS PROMs data analysis demonstrated similarly encouraging outcomes for cKP patients, as previously reported for several other body regions. Knee injury and degeneration subgroups had near-equivalent benefits, as observed for all knee conditions. Despite many reported methodological limitations, which limit causal inference and preclude broader recommendations, HWDS appears to potentially offer several benefits for refractory cKP patients, requiring further studies.

1. Introduction

Knee pain affects up to 25% of adults, with reported prevalence increasing almost 65% over the past two decades [1,2]. The incidence of chronic knee pain (cKP, 19%) ranks second behind chronic low back pain (cLBP, 23%), just ahead of chronic shoulder pain (cSP, 16%), which collectively results in significant societal disability and healthcare expense [3]. A large Swedish registry study concluded that while there is a need for more relevant evidence-based clinical guidelines, and even though LBP was the most common diagnosis, knee osteoarthritis accounted for the highest number of visits and utilization of physiotherapy resources [4]. The primary pain generators in the knee are complex, with receptors being identified within synovium, ligaments, capsule, subchondral bone, and surrounding soft tissues, but not in articular cartilage; regulation occurs at the spinal and cortical level, influenced by psychosocial factors [5].

While cKP is often initiated with injury/trauma, arthritis is the primary cause in those over 50 years of age, where prosthetic surgery may eventually be required [6,7,8,9]. Medications including narcotics, corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and acetaminophen are often used, in combination with multiple non-surgical treatments like physical therapy, intra-articular injections (steroidal and hyaluronic acid), radiofrequency or cryoneurolysis nerve ablation, and possibly regenerative medicine alternatives (platelet-rich plasma and mesenchymal stem cells) [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Corticosteroids and opioids may provide temporary relief, but have problematic side effects, failing to target specific pain generators [13,14,15,16,17].

Electrical stimulation (ES) alternatives for knee pain include transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), H-Wave device stimulation (HWDS), interferential current (IFC) or therapy (IFT), pulsed electromagnetic field therapy (PEMF), and neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) [13,14,15]. A meta-analysis of 27 clinical trials, including six forms of ES (HWDS not included)—citing significant methodological problems of heterogeneity and small sample sizes—suggested that IFC might offer some benefits for knee osteoarthritis [18]. Another systematic review/meta-analysis of TENS for knee osteoarthritis suggested that active TENS resulted in slightly greater pain relief than sham TENS, and that it might enhance other interventions (e.g., physical therapy), although it was ineffective for pain associated with stiffness [19]. In contrast, a high-quality Swiss multicenter randomized clinical trial (n = 220) demonstrated no difference in outcomes or benefits between TENS and placebo TENS for knee osteoarthritis [20]. This reconfirms several Cochrane systematic reviews that continue to be unable to confirm TENS’ effectiveness for knee osteoarthritis or general pain conditions [21,22]. This is in accordance with another more recent review, which reported no additional benefits in pain relief or function from TENS compared to sham treatment coupled with exercise and education programs, where a significant placebo effect was noted [23]. TENS for other body areas has shown only short-lived marginal improvement in reported pain, 0.884/10 on the Visual Analog Scale, with no related improvement in quality of life (QoL) or function measures [13,14,15,24,25]. One review highlighted only general short-term pain relief with transcranial direct current stimulation [26]. A recent meta-analysis reported inadequate evidence for NMES coupled with exercise for management of knee osteoarthritis in terms of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [27].

The H-Wave® device has been cleared by the FDA for 15 specific indications, under four classifications, including chronic, post-surgical, acute, and temporary pain; relaxation of muscle spasm, prevention or retardation of disuse atrophy, increasing local blood circulation, muscle re-education, immediate post-surgical stimulation of calf muscles to prevent venous thrombosis, maintaining or increasing range of motion; anesthesia in general dentistry; and muscle spasms associated with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) [13,14,15].

Numerous H-Wave® studies have reported significant improvements in function, pain, sleep, and QoL [13,14,15]. HWDS uses a unique proprietary, biphasic exponentially decaying waveform (0–35 mA current, 0–35 V voltage at 1000 ohms load, ultra-long 5000-microsecond pulse duration), having low-frequency (2 Hz) and high-frequency (60 Hz) modes [13,14,15]. Multiple mechanisms of action of both modes have been described in detail in related HWDS publications, which involve physiological soft tissue benefits and potent analgesic effects [13,14,15]. Further HWDS studies are warranted since reported clinical outcomes have been more robust than for other forms of ES.

Specialty societies have encouraged studies involving PROMs, which are increasingly respected for evidence-based quality. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) reflect honest assessments of patient health conditions [28]. The National Quality Forum (NQF) states that “PROs can be any description of the patient’s condition, behavior, or experience with treatment that arises straight from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s answer by a clinician or anyone else” [28]. PROMs specify the “instruments, metrics, or tools utilized (e.g., scales, single-item measures) for evaluation of patient-reported health status” [29].

Previously published PROMs studies on H-Wave® efficacy for neck, shoulder, and non-specific chronic low back pain reported equivalent positive outcomes, regardless of body area [13,14,15]. This was not surprising, since the initially reported cLBP outcomes (n = 2711) turned out to be notably similar to those for “all diagnoses” (n = 11,503) [13]. We now hypothesize that HWDS outcomes for cKP will also be similarly encouraging, with the goal of demonstrating significant benefits for pain, function, sleep quality, and drug cessation, with secondary objectives to perform subgroup analyses in patients with knee injury versus degeneration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Design

As more fully described in previous publications, the manufacturer of H-Wave® (Electronic Waveform Lab, Inc., Huntington Beach, CA, USA) routinely and consecutively collects proprietary outcome survey data from user patients, consisting of validated pain and single-item (valid by definition) PROMs. The rationale for the study design is that it takes advantage of large sample sizes and direct patient-reported outcomes, despite various methodological limitations. Over a 4-year period (2019–2022), 34,192 pain management patients returned surveys, where only the most recently submitted ones per patient were analyzed for this study’s purposes. The prospective data was retrospectively evaluated for statistical significance, independently, externally, and without interference, with Electronic Waveform Lab, Inc. allowing the analysis of the untampered raw dataset [13,14,15]. The institutional review board of South Texas Orthopaedic Research Institute, according to the Declaration of Helsinki, approved this study (STORI051624-1, 1 October 2024). The informed consent to gather data and assess it for publication was prospectively obtained from the participating patients. No protected health information (PHI) was analyzed or reported. Electronic Waveform Lab, Inc. gave consent for this entire raw dataset to be independently reviewed, without interference.

This study strictly targets H-Wave® device use for any identified knee disorder in patients 18 years and older, with pain chronicity prior to HWDS initiation from 90 to 730 days (3–24 months), with device treatment duration from 22 to 365 days. Diagnoses included ankylosis, left/right knee; bilateral primary osteoarthritis of knee; bucket-handle tear of medial meniscus; chondromalacia; chondromalacia patellae; chronic instability of knee; complex tear of lateral/medial meniscus, current injury; contusion of left/right knee; derangement of posterior horn of medial meniscus, old tear/injury; osteoarthritis of knee; other bursitis of knee; other instability, left/right knee; other internal derangements of left/right knee; other meniscus derangement; other specified joint disorders, left/right knee; other spontaneous disruption of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL); other spontaneous disruption of medial collateral ligament (MCL); other tear of lateral/medial/unspecified meniscus; pain in left/right/unspecified knee; patellar tendinitis; patellofemoral disorders; plica syndrome; presence of artificial knee joint; peripheral tear of lateral/medial meniscus; sprain of ACL; sprain of lateral/medial collateral ligament (LCL/MCL); sprain of other specified parts of left/right knee; sprain of posterior cruciate ligament (PCL); sprain of unspecified collateral/cruciate ligament; sprain of unspecified site; stiffness of left/right knee; strain of left/right quadriceps muscle, fascia, and tendon; tear of articular cartilage; traumatic arthropathy, left/right knee; unilateral post-traumatic osteoarthritis; unilateral primary osteoarthritis, left/right knee; unspecified internal derangement of left/right knee; and unspecified tear of unspecified meniscus. All non-knee-related diagnoses were excluded.

For the first knee injury subgroup analysis, the inclusion criteria included patients with bucket-handle tear of medial meniscus; chronic instability of knee; complex tear of lateral/medial meniscus, current injury; derangement of posterior horn of medial meniscus, old tear/injury; other instability, left/right knee; other meniscus derangement; other spontaneous disruption of ACL; other spontaneous disruption of MCL; other tear of lateral/medial/unspecified meniscus; pain in left/right/unspecified knee; peripheral tear of lateral/medial meniscus; sprain of ACL; sprain of LCL/MCL; sprain of other specified parts of left/right knee; sprain of PCL; sprain of unspecified collateral ligament; sprain of unspecified cruciate ligament; sprain of unspecified site; strain of left/right quadriceps muscle, fascia, and tendon; tear of articular cartilage; traumatic arthropathy, left/right knee; unilateral post-traumatic osteoarthritis; and unspecified tear of unspecified meniscus. For the second knee degeneration subgroup analysis, inclusion criteria included patients with ankylosis, left/right knee; bilateral primary osteoarthritis of knee; osteoarthritis of knee; presence of artificial knee joint; stiffness of left/right knee; and unilateral primary osteoarthritis, left/right knee. The exclusion criteria for both subgroups were identical, including all non-knee-related diagnoses.

All participants received consistent and standardized training for proper H-Wave® device home use. Primary study outcomes include H-Wave® effects on self-reported pain, medication usage, function/activities of daily living (ADL), and sleep. Secondary outcomes include work performance, patient satisfaction, and device preference compared to prior treatment. A checklist of STROBE Epidemiology Reporting (for observational studies) was strictly followed.

2.2. Data Collection

The participants answered specific questions (Figure S1) regarding their experiences with HWDS, specifically related to effects on function/ADL, pain, medication usage, work, sleep, prior treatments, and device satisfaction, obtained using a previously published questionnaire [13,14,15]. Additionally, gender, age (when injured), pain duration, and specifics of device use were queried. The survey instrument, while proprietary, included several validated PROMs, like Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) pain measures, and single-item questions derived from general (not knee-specific) function outcome instruments, including the Oswestry Disability Index. Many patients completed several survey questionnaires during their treatment, so to avoid duplication and provide consistency, only the final completed survey per participant was analyzed. Also, missing or repeated survey responses were excluded from the data analysis.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Consistent with previous related studies, the independent data analyses consisted of an initial univariate distributional, correlation/association, and contingency table, applying several logistic and linear regression methods on all participant covariates. A stepwise model selection technique resulted in a statistically significant (≤5% significance) and parsimonious model. The statistical programming language R, along with SAS JMP, was employed for data pre-processing and analysis. While linear regressions were performed with stepwise model selection techniques, diagnostics and assessments were completed to check the normality assumption of the residuals [13,14,15].

An a priori power calculation was not performed, justified by the study’s design as a retrospective, descriptive analysis of an existing, large, consecutively collected PROMs database. The objective was to report real-world outcomes to provide robust preliminary evidence for the planning of future, adequately powered, prospective randomized controlled trials.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

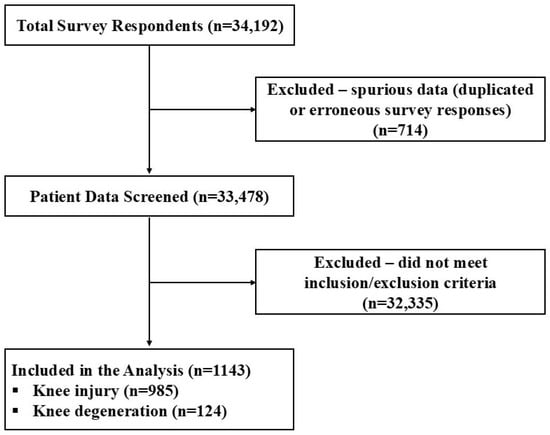

Out of 34,192, 1143 knee participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were subject to data assessment. Gender distribution was fairly uniform, with a slightly lower proportion of females (47.59%) than males (52.41%) (Figure 1, Table 1). Average age at date of injury and onset of HWDS treatment were 47.96 ± 11.59 and 48.82 ± 11.61 years (±standard deviation), respectively. Average reported pain length and H-Wave® duration of use were 310.85 ± 179.25 and 93.33 ± 65.55 days, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Inclusion/exclusion flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of H-Wave® device stimulation (HWDS) intervention cohort.

For subgroup analysis, the inclusion criteria were met by 985 knee injury patients (Figure 1). Gender distribution showed a lower proportion of females (46.60%) than males (53.40%). Average age at date of injury and onset of HWDS treatment were 47.66 ± 11.55 and 48.50 ± 11.56 years, respectively. Average reported pain length and H-Wave® duration of use were 306.78 ± 178.09 and 93.15 ± 65.80 days, respectively (Table 1).

Only 124 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria with knee degeneration (Figure 1). Gender distribution showed a lower proportion of females (41.13%) than males (58.87%). Average age at date of injury and onset of HWDS treatment were 52.42 ± 10.72 and 53.47 ± 10.80 years, respectively. Average reported pain length and H-Wave® duration of use were 380.42 ± 199.22 and 92.80 ± 66.80 days, respectively (Table 1).

In summary, while both subgroups appear to be similar across several demographic characteristics, the knee degeneration group had an older, more predominantly male population and longer pain chronicity compared to the knee injury group, with identical HWDS usage.

3.2. Device Usage

Of the 1143 knee patients, 1111 utilized the device twice a day (1.91 ± 0.89), and 1094 used it five and a half days a week (5.67 ± 1.61). Of 1129 patients with available data, over half (52.52%) used it for 30–45-min treatment sessions.

Of the 985 knee injury patients, 958 utilized the device twice a day (1.90 ± 0.89), and 944 used it five and a half days a week (5.66 ± 1.61). Of 974 patients with available data, over half (53.18%) used it for 30–45-min treatment sessions.

Of the 124 patients with knee degeneration, 119 utilized the device twice a day (1.93 ± 0.71), and 118 used it five and a half days a week (5.64 ± 1.71). Of 122 patients with available data, over half (53.28%) used it for sessions lasting 30 to 45 min.

3.3. Insurance Mix

This knee investigation cohort mostly comprised workers’ compensation claimants (n = 1021, 89.48%). Other claimants included personal injury (n = 86, 7.54%), auto injury (n = 32, 2.81%), and Tricare patients (n = 2, 0.17%).

A similar mix was observed in knee injury patients, with 88.71% workers’ compensation (n = 872), 8.34% personal injury (n = 82), 2.75% auto injury (n = 27), and 0.20% Tricare (n = 2) claimants. In contrast, patients with knee degeneration included 98.39% workers’ compensation (n = 122) and 1.61% auto injury claimants (n = 2).

3.4. Concomitant Home Exercise Program

Of 1100 patients with available data, over two-thirds (n = 776, 70.55%) participated in home exercise, with the others (n = 324, 29.45%) not doing so. Of 947 patients with knee injury, over two-thirds (n = 668, 70.54%) participated in home exercise, with the others (n = 279, 29.46%) not doing so. Of 120 patients with knee degeneration, two-thirds (n = 80, 66.67%) participated in home exercise, with the others (n = 40, 33.33%) not doing so.

3.5. Primary Outcome Measures

3.5.1. Pain Reduction

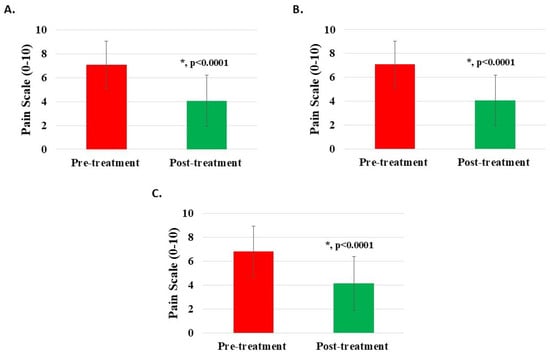

The pre-treatment Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) for 1130 knee patients averaged 7.06 ± 1.98 (95% confidence interval: 6.94, 7.17), while post-treatment (for 1127) averaged 4.07 ± 2.14 (95% confidence interval: 3.94, 4.20). The improvement difference between post-treatment and pre-treatment (for 1125) was 2.96 ± 1.77 (95% confidence interval: 2.86, 3.06). An NRS difference of 2 or more was statistically significant (p < 0.0001) (Figure 2A, Table 2). Half (n = 257, 50.59%) of the patients with NRS ratings of 8 or higher (n = 508, 44.96%) before treatment reduced to 5 or less after treatment.

Figure 2.

Pain reduction post-treatment with H-Wave® device stimulation for (A) all knee disorders, (B) knee injury, and (C) knee degeneration. A difference of 2 or more points was statistically significant for all groups (*, p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Analysis of primary and secondary outcome measures. * Demonstrates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

For subgroup analysis, the pre-treatment NRS for 974 patients with knee injury averaged 7.09 ± 1.95 (95% confidence interval: 6.97, 7.21), while post-treatment (for 972) averaged 4.07 ± 2.12 (95% confidence interval: 3.94, 4.21). The improvement difference between post-treatment and pre-treatment (for 971) was 2.99 ± 1.76 (95% confidence interval: 2.88, 3.10). An NRS difference of 2 or more was statistically significant (p < 0.0001) (Figure 2B, Table 2). Half (n = 223, 51.15%) of the knee injury patients with NRS ratings of 8 or higher before treatment reduced to 5 or less following treatment. Likewise, the pre-treatment NRS for 123 patients with knee degeneration averaged 6.85 ± 2.11 (95% confidence interval: 6.47, 7.22), while post-treatment (for 122) averaged 4.14 ± 2.25 (95% confidence interval: 3.74, 4.54). The improvement difference between post-treatment and pre-treatment (for 122) was 2.72 ± 1.74 (95% confidence interval: 2.41, 3.03). An NRS difference of 2 or more was statistically significant (p < 0.0001) (Figure 2C, Table 2). Only 22 patients (41.51%) with knee degeneration with NRS ratings of 8 or higher before treatment reduced to 5 or less following treatment.

Pain reduction of 20% or more has been previously considered as a reasonable estimate for the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for H-Wave® [15]. Of 1125 knee subjects, 976 (86.76%) documented post-treatment pain relief of 20% or more (p < 0.0001) (Figure 3A). Of 971 patients with knee injury, 847 (87.23%) documented post-treatment pain relief of 20% or more (p < 0.0001) (Figure 3B). Of 122 patients with knee degeneration, 102 (83.61%) documented post-treatment pain relief of 20% or more (p < 0.0001) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Pain relief of at least 20% post-treatment with H-Wave® device stimulation for (A) all knee disorders, (B) knee injury, and (C) knee degeneration. This was statistically significant for all groups (*, p < 0.0001).

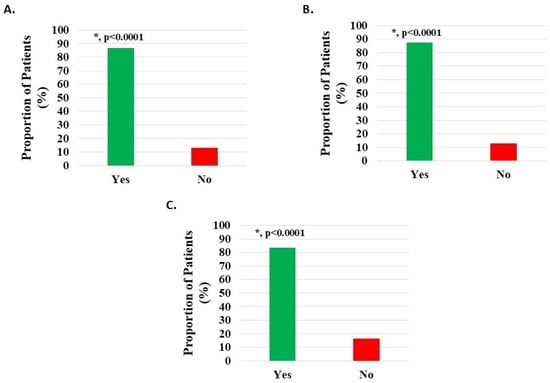

3.5.2. Function/ADL Improvement

Of 1090 HWDS knee subjects (excluding 53 with missing survey data, Table S1), 1052 (96.51%) documented statistically significant improvement (p < 0.0001) in post-treatment function (Figure 4A, Table 2).

Figure 4.

Improvement in function/ADL post-treatment with H-Wave® device stimulation for (A) all knee disorders, (B) knee injury, and (C) knee degeneration. The improvement was statistically significant for all groups (*, p < 0.0001).

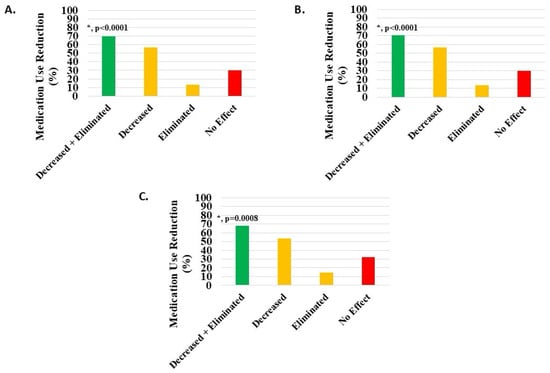

3.5.3. Medication Usage Decrease

Of 806 knee patients (excluding 337 with missing data), 70% (n = 563, 69.85%) reported a statistically significant (p = 0.0008) reduction or cessation of pain medication use. Post-treatment, 457 patients (56.70%) reduced and 106 (13.15%) eliminated pain medications (Figure 5A, Table 2).

Figure 5.

Decrease or elimination in use of pain medications post-treatment with H-Wave® device stimulation for (A) all knee disorders, (B) knee injury, and (C) knee degeneration. Decreased + eliminated versus no effect was statistically significant for all groups (*, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001, and p = 0.0008, respectively).

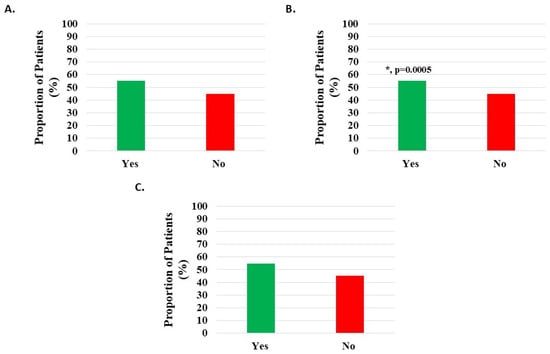

3.5.4. Sleep Improvement

Of 1143 knee subjects, 630 (55.12%) indicated sleep quality improvement; however, this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 6A, Table 2).

Figure 6.

Improvement in quality of sleep post-treatment with H-Wave® device stimulation for (A) all knee disorders, (B) knee injury, and (C) knee degeneration. The improvement was statistically significant for only the knee injury group (*, p = 0.0005).

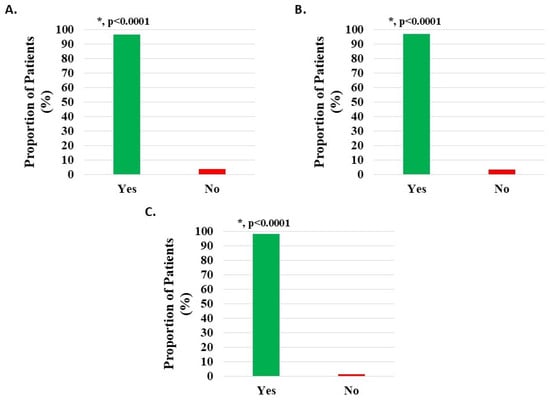

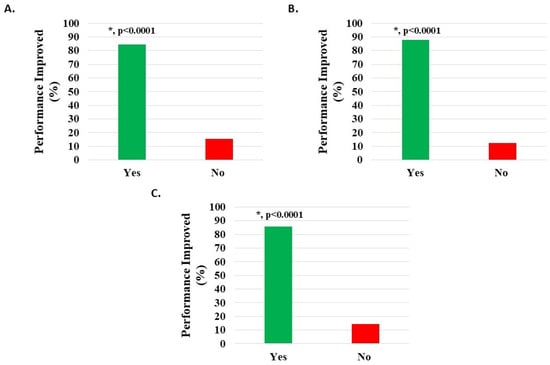

3.6. Secondary Outcome Measures

3.6.1. Work Status and Performance

Of 1083 knee subjects (excluding 60 with missing data), 634 (58.54%) were off work when starting H-Wave®, while 235 (21.70%) performed modified work, and 214 (19.76%) were in full-time work. Of the 634 subjects off work, 339 related this to their injury, and of these, 143 (42.18%) indicated that H-Wave® had assisted their return to work. Data analysis from those not working suggested that the larger the difference between reported pain levels before and after HWDS, the more likely HWDS was to help them return to work (p < 0.0001, 95% confidence interval: 0.274, 0.607). Of 423 subjects (excluding 26 with missing survey data) performing full or modified work, 358 (84.63%) reported statistically significant (p < 0.0001) improvement in performance at work following treatment with H-Wave® (Figure 7A, Table 2). Additional analysis suggested that H-Wave® is more likely to improve performance at work for those whose pain was reduced by at least 20% after treatment (odds ratio = 25.215; 95% confidence interval: 11.461, 57.888).

Figure 7.

Improvement in work performance in patients on full or modified duty post-treatment with H-Wave® device stimulation for (A) all knee disorders, (B) knee injury, and (C) knee degeneration. The improvement was statistically significant for all groups (*, p < 0.0001).

Of 935 knee injury subjects (excluding 50 with missing data), 547 (58.50%) were off work when starting H-Wave®, while 205 (21.93%) performed modified work, and 183 (19.57%) were in full-time work. Of the 547 subjects off work, 289 related this to their injury, and of these, 128 (44.29%) indicated that H-Wave® had assisted their return to work. Data analysis from those not working suggested that the larger the difference between pain levels before and after HWDS, the more likely HWDS was to help them return to work (p < 0.0001, 95% confidence interval: 0.227, 0.572). Of 359 subjects (excluding 29 with missing survey data) performing full or modified work, 315 (87.74%) reported statistically significant (p < 0.0001) improvement in performance at work following treatment with H-Wave® (Figure 7B, Table 2). Additional analysis suggested that H-Wave® is more likely to improve performance at work for those whose pain was reduced by at least 20% after treatment (odds ratio = 22.117; 95% confidence interval: 8.516, 59.712).

Of 119 knee degeneration subjects (excluding 5 with missing data), 74 (62.18%) were off work when starting H-Wave®, while 19 (15.97%) performed modified work, and 26 (21.85%) were in full-time work. Of the 74 subjects off work, 37 related this to their injury, and of these 37, 14 (37.84%) indicated that H-Wave® had assisted their return to work. Of 42 subjects (excluding 3 with missing survey data) performing full or modified work, 36 (85.71%) reported statistically significant (p < 0.0001) improvement in performance at work following treatment with H-Wave® (Figure 7C, Table 2). Additional analysis suggested that H-Wave® is more likely to improve performance at work for those whose pain was reduced by at least 20% after treatment (odds ratio = 61.999; 95% confidence interval: 6.077, 1624.832).

3.6.2. Prior Treatment and Preference for HWDS

Of 1143 knee subjects, 1121 (98.07%) used other treatment modalities prior to H-Wave® (p < 0.0001). Of 1092 patients (excluding 51 with missing data), 743 (68.04%) reported that H-Wave® was significantly (p < 0.0001) more helpful than prior treatments, while 328 (30.04%) noted similar efficacy, and 21 (1.92%) less efficacy (Table 2).

Of 985 knee injury subjects, 967 (98.17%) used other treatment modalities prior to H-Wave® (p < 0.0001). Of 944 patients (excluding 41 with missing data), 654 (69.28%) reported that H-Wave® was significantly (p < 0.0001) more helpful than prior treatments, while 277 (29.34%) noted similar efficacy, and 13 (1.38%) less efficacy (Table 2).

Of 124 knee degeneration subjects, 123 (99.19%) used other treatment modalities prior to H-Wave® (p < 0.0001). Of 118 patients (excluding 6 with missing data), 78 (66.10%) reported that H-Wave® was significantly (p < 0.0001) more helpful than prior treatments, while 36 (30.51%) noted similar efficacy, and 4 (3.39%) less efficacy (Table 2).

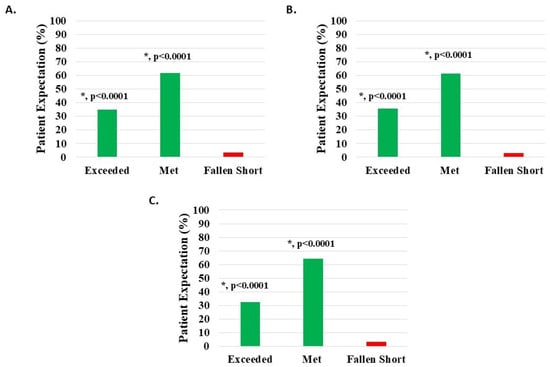

3.6.3. Patient Expectations

Of 1094 knee subjects (excluding 49 with missing data), 1056 (96.53%) reported that HWDS met or exceeded expectations; 674 (61.61%) noted met expectations and 382 (34.92%) exceeded expectations, both statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Expectations were not met in 38 patients (3.47%) (Figure 8A, Table 2).

Figure 8.

Level of patient expectations, where the proportion reporting H-Wave® device stimulation either exceeded or met expectations, was statistically significant (*, p < 0.0001) for all groups analyzed: (A) all knee disorders, (B) knee injury, and (C) knee degeneration.

Of 942 knee injury patients (excluding 43 with missing data), 912 (96.82%) reported that HWDS met or exceeded expectations; 578 (61.36%) noted met expectations and 334 (35.46%) exceeded expectations, both statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Expectations were not met in 30 patients (3.18%) (Figure 8B, Table 2).

Of 120 knee degeneration patients (excluding 4 with missing data), 116 (96.67%) reported that HWDS met or exceeded expectations; 77 (64.17%) noted met expectations and 39 (32.50%) exceeded expectations, both statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Expectations were not met in four patients (3.33%) (Figure 8C, Table 2).

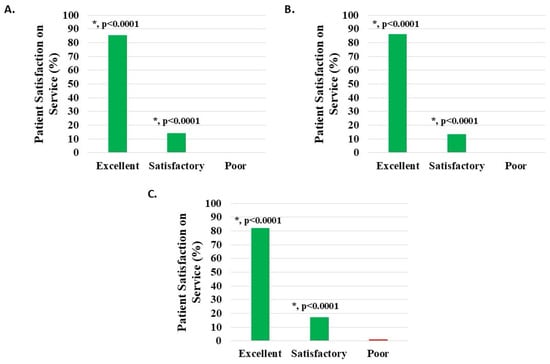

3.6.4. Patient Satisfaction with Service

Of 1114 knee subjects (excluding 29 with missing data), 1109 (99.55%) reported that the H-Wave® team service was satisfactory or excellent; 158 (14.18%) noted satisfactory and 951 (85.37%) excellent, both statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Poor service was noted in five patients (0.45%) (Figure 9A, Table 2).

Figure 9.

Level of patient satisfaction with service, where the proportion reporting H-Wave® device stimulation instruction to be excellent or satisfactory was statistically significant (*, p < 0.0001), for all groups analyzed: (A) all knee disorders, (B) knee injury, and (C) knee degeneration.

Of 958 knee injury subjects (excluding 27 with missing data), 955 (99.69%) reported that the H-Wave® team service was satisfactory or excellent; 130 (13.57%) noted satisfactory and 825 (86.12%) excellent, both statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Poor service was noted in three patients (0.31%) (Figure 9B, Table 2).

Of 122 knee degeneration subjects (excluding 2 with missing data), 121 (99.18%) reported that the H-Wave® team service was satisfactory or excellent; 21 (17.21%) noted satisfactory and 100 (81.97%) excellent, both statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Poor service was noted in one patient (0.82%) (Figure 9C, Table 2).

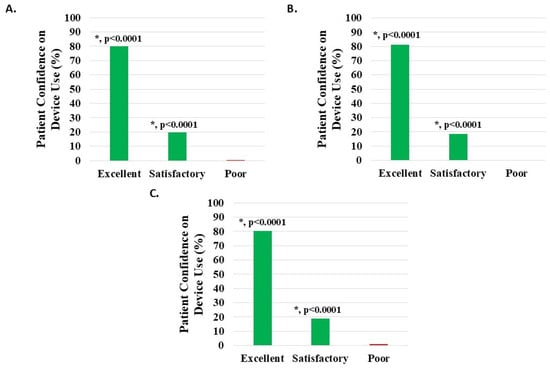

3.6.5. Patient Confidence in Device Use

Of 1112 knee subjects (excluding 31 with missing data), 1108 (99.64%) reported device usage confidence to be satisfactory or excellent; 218 (19.60%) noted satisfactory and 890 (80.04%) excellent, both statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Poor confidence was noted in four patients (0.36%) (Figure 10A, Table 2).

Figure 10.

Level of patient confidence in device use, where the proportion reporting H-Wave® device stimulation use on their own being excellent or satisfactory was statistically significant (*, p < 0.0001) for all groups analyzed: (A) all knee disorders, (B) knee injury, and (C) knee degeneration.

Of 956 knee injury subjects (excluding 29 with missing data), 953 (99.69%) reported device usage confidence to be satisfactory or excellent; 178 (18.62%) noted satisfactory and 775 (81.07%) excellent, both statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Poor confidence was noted in three patients (0.31%) (Figure 10B, Table 2).

Of 122 knee degeneration subjects (excluding 4 with missing data), 121 (99.18%) reported device usage confidence to be satisfactory or excellent; 23 (18.85%) noted satisfactory and 98 (80.33%) excellent, both statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Poor confidence was noted in one patient (0.82%) (Figure 10C, Table 2).

3.7. Outcomes Based on Treatment Period

Three subgroups were stratified by number of days of H-Wave® use, including a “trial period” from 22 to 35 days (3 to 5 weeks), an “early treatment period” from 36 to 98 days (5 to 14 weeks), and a “late treatment period” from 99 to 365 days (14 to 52 weeks); sample sizes were 320 (28%), 299 (26.16%), and 524 (45.84%) knee patients, respectively. Outcomes were generally consistent regardless of treatment duration, although device use for longer periods correlated with more pain relief, medication cessation, improved sleep, and better work performance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of treatment duration on outcome measures.

Additional findings were observed through supplementary multiple regression analyses of statistical significance, where duration of both device use and pain chronicity were important variables affecting the outcomes. Statistically significant inferences include the following:

- Device usage over longer periods resulted in greater pain reduction (p < 0.0001);

- Less pain reduction occurred with longer chronicity of pain (p < 0.0001);

- The greater the difference in reported pain level before and after treatment, the more likely HWDS improved sleep (p < 0.0001);

- Function/ADL improved more when pain levels were reduced by at least 20% following treatment (p < 0.0001).

3.8. Outcomes Based on Longer Pain Chronicity

The outcomes reported above represent the study restriction of pain chronicity between 3 and 24 months, but an analysis was also performed, including more chronic patients up to 36 months. Sample size for “all knee diagnoses” increased from 1143 to 1352 patients. Outcomes were equivalent for improvements in function/ADL (96.51% at 2 years, 96.35% at 3 years), work performance (84.63% at 2 years, 84.92% at 3 years), and medication reduction (69.85% at 2 years, 68.42% at 3 years). While other results remained positive after adding the additional patients, slightly less robust outcomes were observed in average reported pain level reduction (2.96% at 2 years, 2.55% at 3 years), return-to-work (42.18% at 2 years, 31.07% at 3 years), and sleep improvement (55.12% at 2 years, 48.99% at 3 years).

4. Discussion

This is a PROMs study of the potential effectiveness of HWDS for treatment of chronic knee pain conditions. Surveys meeting the study criteria included those from 1143 “all knee diagnoses” patients, with subgroup analyses performed for 985 knee injury and 124 degenerative knee conditions (e.g., osteoarthritis, stiffness, and joint replacement). As previously and consistently demonstrated for low back, neck, and shoulder conditions—primarily in injured workers [13,14,15]—clinical outcomes were positive and encouraging. Given the magnitude of reported improvements in function, pain, sleep, and decreased medication use, HWDS appears to be a reasonable consideration for otherwise difficult-to-treat refractory painful knee conditions resulting from injury or degeneration.

The most common site of musculoskeletal pain is the back, followed by the knee, which accounts for almost 4 million visits annually to primary care providers (many more directly to specialists), where physical disability rises with age and becomes more symptomatic in areas of higher social deprivation [1,2,3]. Osteoarthritis (OA) and related degenerative conditions are progressive by nature, accounting for significant disability, with a highly variable incidence of pain and a poor correlation to imaging; treatment is not definitive, as surgery often fails to guarantee improvement [2,3]. Physical therapy, corticosteroid injection, and viscosupplementation have been most widely studied for non-surgical knee treatment, while nerve ablation (thermal, radiofrequency, and cryoneurolysis) and geniculate artery synovial embolization are alternatives currently under study [12]. Intra-articular injections have demonstrated mild effects lasting limited periods of time, prompting research in regenerative medicine—particularly platelet-rich plasma or mesenchymal stem cells—in the hopes of achieving more durable pain relief [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Electrical stimulation (ES) has gained interest as an alternative non-surgical, non-invasive management modality, either used stand-alone or as an adjunct. Some authors suggest that interferential current (IFC) might offer the most promise for knee OA, while others more recently have reported robust improvements in general function and chronic pain with HWDS [13,14,15,18]. In contrast, TENS, the most prescribed form of ES, has been demonstrated to be relatively ineffective for knee OA pain, despite promising pre-clinical studies [20,30]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses comparing different forms of ES for knee pain remain limited, with almost no direct comparisons between devices, limiting definitive guidelines support [18,20,21]. As an example, Clinical Practice Guidelines for non-surgical treatment of knee OA by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons only offer limited recommendations for TENS, PEMF, and percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [31].

PROMs are being increasingly reported as a measure of treatment effectiveness, efficiency, and patient satisfaction, providing essential outcomes from the patient’s perspective, supporting value-based healthcare models [32]. As observed in the previously published shoulder PROMs study, HWDS for the knee appears to be similarly effective, not only to positive shoulder outcomes, but also to those reported for chronic spinal pain [13,14,15]. Differences in treatment effects between knee injury and degenerative (primarily OA) conditions were minimal. Pain chronicity up to 24 months was reported, consistent with earlier publications on low back and neck, but data was additionally analyzed for up to 36 months (increasing sample size), with only minor notable differences in statistical outcomes. Workers’ compensation claimants dominated the study cohort—patients who generally have poorer treatment outcomes—but even so, knee outcomes were similarly compelling, consistent with multiple previous HWDS studies.

Here, knee pain reduction with HWDS was almost 3 (2.96) on a scale of 10, significantly higher than TENS (0.88/10) for generalized conditions [13,14,15]. Specifically, pain reduction of 20% or more (MCID) was reported by 87% of knee patients. Improvements in function were self-reported in almost 97%, with work performance in those working improving in almost 85%. Almost 70% of patients on medications decreased or stopped them, with sleep improvement reported by 55% of knee injury participants. The lack of statistical significance for sleep improvement in the knee degeneration group can be attributed to the limited sample size, instead of an absence of true therapeutic effect. Patient satisfaction was 97% or higher for expectations, service, and confidence with the device. Moreover, an analysis including additional patients with pain chronicity beyond two and up to three years found equivalent outcomes for function/ADL, work performance, and medication reduction, while slightly lower average pain level reduction, return-to-work times, and sleep improvements were noted. This is similar to prior low back, neck, shoulder, and other HWDS publications, where it has been repeatedly demonstrated that longer duration of pain leads to a lower reduction in reported pain [13,14,15].

Adverse events (AEs), either mild or severe, were not specifically analyzed in this database, even though patients could report them under comments (question #13, Figure S1). The manufacturer methodically collects AE occurrences separately from the survey, mostly consisting of minor skin irritation beneath the adhesive lead pads. Prior non-PROMs H-Wave studies have consistently reported rare and benign safety issues, typical of FDA-approved Class II devices [13,14,15].

Limitations and Future Directions

The authors fully acknowledge that this is a single-center, observational, retrospective analysis of a convenience sample, primarily workers’ compensation claimants, necessitating a guarded generalization of the findings. A priori sample size calculation was not performed due to the retrospective design. However, the large cohort of over 1000 patients supports generating hypotheses for future studies. The manuscript reports all relevant outcomes and 95% confidence intervals. For the primary pain outcome, we currently report a mean NRS reduction of 2.96 points (95% CI: 2.86, 3.06).

Additional limitations beyond the retrospective design (prospective data collection) and possible risk of selection bias (workers’ compensation cohort) include lack of a control group and inherent risk of bias in the manufacturer-distributed survey (voluntary convenience). No BMI was determined for either group. Concurrent treatments, with the exception of home exercise, were not specifically reported, nor were any co-morbidities, further confounding interpretation. This study also lacks the computation of T-scores. Additionally, this study lacks a formal power calculation and has the potential for residual confounding from non-adjusted descriptive analyses, acknowledging that the one-year maximum treatment duration analyzed constitutes a limitation on long-term follow-up. Inclusion criteria included differing pathophysiologies such as acute injuries, chronic degeneration, post-traumatic osteoarthritis, and post-arthroplasty, with different expected responses.

The proprietary survey instrument was partially unvalidated, although it included valid NRS and multiple single-item questions. Specific instruments such as KOOS, WOMAC, and the Oxford Knee Score would be more appropriate for future condition-specific studies. The final survey was defined as only the final completed survey per participant to provide consistency and prevent patient duplication, although this approach could be a source of inherent survivorship and responder bias. Study improvements might have included data collected from individual participants over time and more specific safety reporting.

Multivariate analyses were performed using stepwise linear and logistic regression models to identify parsimonious models from participant covariates. While these models attempt to account for some variables, the reliance on descriptive statistics for primary outcomes and the retrospective nature of this study mean that potential confounders, such as concurrent treatments (other than recorded home exercise), were not completely controlled for, where the lack of comprehensive adjustment could potentially affect the interpretability, warranting the recommendation of guarded generalization of the results.

The current data format and absence of certain auxiliary information prevented the quantification of response rates relative to device distribution, a comparison between responders and non-responders, and a comprehensive sensitivity analysis comparing early versus final surveys. Regarding a substantial proportion of missing data, such data is neither missing at random (MAR) nor missing completely at random (MCAR), suggesting systematic missingness, requiring the use of a transparent complete case analysis by excluding cases with missing values during subgroup analysis, acknowledging that this reduces generalizability (external validity) and may result in risk of estimation bias.

Further randomized prospective knee-specific clinical trials would help to additionally confirm these HWDS PROMs findings.

5. Conclusions

Analysis of the H-Wave® PROMs data collected sequentially over 4 years suggested positive benefits for cKP patients. At least 20% pain relief or greater was reported in 86% of cKP participants, with an almost 3-point (2.96) decrease following treatment (0–10 NRS scale). Participants reported function/ADL improvement in 96%, while performance of working patients improved in 85%. Additionally, use of pain medication was stopped or decreased in 70%, with sleep improving in 55% of knee injury patients (Figure S2). Almost all cKP patients indicated met or exceeded expectations (96.53%), satisfaction with service (99.55%), and confidence in device use (99.64%). Outcomes for both subgroups, knee injury and degeneration, were very similar to those of all knee conditions. Longer device use seemed to be predictive of greater pain relief, while longer pain chronicity slightly reduced HWDS’ effectiveness. Despite many methodological limitations, which limit causal inference and preclude broader clinical recommendations, this unique form of ES appears to be promising for refractory cKP, suggesting the need for further higher-quality randomized controlled trials for more specific indications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/medicina62010075/s1, Figure S1: H-Wave® outcome and usage questionnaire; Figure S2: Summary of H-Wave® device stimulation reported outcomes for (A) all knee disorders, (B) knee injury, and (C) knee degeneration; Table S1: Summary of missing data across all groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and S.M.N.; methodology, A.G., D.H. and S.M.N.; software, D.H.; formal analysis, A.G., D.H. and S.M.N.; data curation, D.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., D.H. and S.M.N.; writing—review and editing, A.G., D.H. and S.M.N.; supervision, A.G.; project administration, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of South Texas Orthopaedic Research Institute (protocol code STORI051624-1 and 1 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

A.G. and S.M.N. are consultants for Electronic Waveform Lab, Inc. D.H. has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Author Ashim Gupta was employed by the company Future Biologics. Future Biologics has no conflict of interest with the submitted work. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial re-lationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| cKP | Chronic knee pain |

| PROMS | Patient-reported outcome measures |

| HWDS | H-Wave® device stimulation |

| ADL | Activities of daily living |

| cLBP | Chronic low back pain |

| cSP | Chronic shoulder pain |

| ES | Electrical stimulation |

| PEMF | Pulsed electromagnetic field therapy |

| IFC | Interferential current |

| IFT | Interferential therapy |

| TENS | Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation |

| NMES | Neuromuscular electrical stimulation |

| PROs | Patient-reported outcomes |

| NQF | National Quality Forum |

| PHI | Protected health information |

| ACL | Anterior cruciate ligament |

| MCL | Medial cruciate ligament |

| LCL | Lateral cruciate ligament |

| PCL | Posterior cruciate ligament |

| NRS | Numeric Rating Scale |

| MCID | Minimal clinically important difference |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| MCAR | Missing completely at random |

| MAR | Missing at random |

References

- Nuer, A.; Yang, Y.; Sun, B.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Lu, W. Progression and influencing factors of knee osteoarthritis based on a multi-state Markov model: Data from OAI. Osteoarthr. Cartil. Open 2025, 8, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliddal, H.; Hartkopp, A.; Beier, J.; Conaghan, P.G.; Henriksen, M. A prospective, open-label, clinical investigation of a single intra-articular polyacrylamide hydrogel injection in participants with knee osteoarthritis: A 5-year extension study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urwin, M.; Symmons, D.; Allison, T.; Brammah, T.; Busby, H.; Roxby, M.; Simmons, A.; Williams, G. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: The comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1998, 57, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Östlind, E.; Larsson, C.; Eek, F. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders and physiotherapy utilization in primary care—A registry-based study in Sweden. BMC Prim. Care 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviv, B.; Bronak, S.; Thein, R. The complexity of pain around the knee in patients with osteoarthritis. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2013, 15, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lohrasbi, E.; Babaie, S.; Hamedfar, H.; Pourzeinali, S.; Farshbaf-Khalili, A.; Toopchizadeh, V. Regenerative Therapy in Osteoarthritis Using Umbilical Cord-Origin Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Critical Appraisal of Clinical Safety and Efficacy Through Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Stem Cells Int. 2025, 2025, 4261166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Santiuste, M.; Vaquerizo García, V.; Pareja Esteban, J.A.; Prado, R.; Padilla, S.; Anitua, E. Plasma Rich in Growth Factors (PRGF) Versus Saline Intraosseous Infiltrations Combined with Intra-Articular PRGF in Severe Knee Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Double-Blind Multicentric Randomized Controlled Trial with 1-Year Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryliński, Ł.; Brylińska, K.; Woliński, F.; Sado, J.; Smyk, M.; Komar, O.; Karpiński, R.; Prządka, M.; Baj, J. Trace Elements-Role in Joint Function and Impact on Joint Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Cheng, T.; Yu, X. The Impact of Trace Elements on Osteoarthritis. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 771297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensa, A.; Bianco Prevot, L.; Moraca, G.; Sangiorgio, A.; Boffa, A.; Filardo, G. Corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, platelet-rich plasma, and cell-based therapies for knee osteoarthritis—Literature trends are shifting in the injectable treatments’ evidence: A systematic review and expert opinion. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2025, 25, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choffat, C.; Chung, P.C.S.; Cachemaille, M. Interventional pain management for knee pain. Rev. Med. Suisse 2020, 16, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, D.T.; Piechowiak, R.; Nissman, D.; Bagla, S.; Issacson, A. Current Concepts and Future Directions of Minimally Invasive Treatment for Knee Pain. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2018, 20, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwood, S.M.; Han, D.; Gupta, A. H-Wave® Device Stimulation for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) Study. Pain. Ther. 2024, 13, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Han, D.; Norwood, S.M. H-Wave® Device Stimulation for Chronic Neck Pain: A Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) Study. Pain Ther. 2024, 13, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norwood, S.M.; Han, D.; Gupta, A. H-Wave Device Stimulation Benefits Chronic Shoulder Pain in an Observational Cohort Study of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanasirisombat, K.; Boontanapibul, K.; Pinitchanon, P.; Pinsornsak, P. Betamethasone and Triamcinolone Acetonide Have Comparable Efficacy as Single Intra-Articular Injections in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Double-Blinded, Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seah, K.T.M.; Neufeld, M.E.; Howard, L.C.; Garbuz, D.S.; Masri, B.A. Injection-Based Therapies for the Management of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2025, 107, 2437–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Li, H.; Yang, T.; Deng, Z.H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, G.H. Electrical stimulation for pain relief in knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015, 23, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhu, F.; Chen, W.; Zhang, M. Effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in people with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2022, 36, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenbach, S.; Jüni, P.; Hincapié, C.A.; Schneider, C.; Meli, D.N.; Schürch, R.; Streit, S.; Lucas, C.; Mebes, C.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; et al. Effect of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) on knee pain and physical function in patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: The ETRELKA randomized clinical trial. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2022, 30, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutjes, A.W.; Nüesch, E.; Sterchi, R.; Kalichman, L.; Hendriks, E.; Osiri, M.; Brosseau, L.; Reichenbach, S.; Jüni, P. Transcutaneous electrostimulation for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2009, CD002823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, W.; Wand, B.M.; Meads, C.; Catley, M.J.; O’Connell, N.E. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for chronic pain—An overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2, CD011890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shtroblia, V.; Petakh, P.; Kamyshna, I.; Halabitska, I.; Kamyshnyi, O. Recent advances in the management of knee osteoarthritis: A narrative review. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1523027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, J.J.; Cherian, J.J.; Gam, C.U.; Chughtai, M.; Mistry, J.B.; Elmallah, R.K.; Harwin, S.F.; Bhave, A.; Mont, M.A. A Meta-Analysis of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation for Chronic Low Back Pain. Surg. Technol. Int. 2016, 28, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- National Guideline Centre (UK). Evidence Review for Electrical Physical Modalities for Chronic Primary Pain: Chronic Pain (Primary and Secondary) in Over 16s: Assessment of All Chronic Pain and Management of Chronic Primary Pain; NICE Evidence Reviews Collection; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tungushpayev, M.; Viderman, D. Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on pain and pain-related outcomes: An umbrella review. Korean J. Pain 2025, 38, 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, M.T.X.; Guesser Pinheiro, V.H.; Alberton, C.L. Effectiveness of neuromuscular electrical stimulation training combined with exercise on patient-reported outcomes measures in people with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiother. Res. Int. 2024, 29, e2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, F.J.; Rivera, S.C.; Liu, X.; Manna, E.; Denniston, A.K.; Calvert, M.J. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in trials of artificial intelligence health technologies: A systematic evaluation of ClinicalTrials.gov records (1997–2022). Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e160–e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, K.J.; Brox, W.T.; Naas, P.L.; Tubb, C.C.; Muschler, G.F.; Dunn, W. Musculoskeletal-based patient-reported outcome performance measures, where have we been-where are we going. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2019, 27, e589–e595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.T.; Santos, M.M.; Reis, K.L.M.D.C.; Oliveira, L.R.; DeSantana, J.M. Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation in Animal Model Studies: From Neural Mechanisms to Biological Effects for Analgesia. Neuromodulation 2024, 27, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, R.H.; Fillingham, Y.A. AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline Summary: Management of Osteoarthritis of the Knee (Nonarthroplasty), Third Edition. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 30, e721–e729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Chen, A.F.; Durst, C.R.; Debbi, E.M. Optimal Utilization of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in Total Joint Arthroplasty. JBJS Rev. 2024, 12, e24.00121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.