1. Introduction

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a general term for a collection of neuromuscular and musculoskeletal pathologies that include temporomandibular joint (TMJ), masticatory muscles, and supporting structures [

1]. Although prevalence data vary, it is believed that between 3.2 and 15% or 17.6% of individuals suffer with TMD, with women between the ages of 20 and 40 having a greater frequency, approximatively 2.1 times more than men [

2,

3]. TMD peaks during the reproductive years in women [

4]. The prevalence of TMD in young people and adolescents ranges from 20% to 60% [

5].

The etiology of TMD is multi-factorial, both in terms of biological, psychological, and environmental factors, and it often overlaps with other syndromes, including headaches, fibromyalgia, and syndromes of chronic pain [

6,

7]. Risk factors for temporomandibular disorders were female gender, depression, anxiety, stress, sleep disturbances, obstructive sleep apnea, headache, migraine, and other chronic pains [

8,

9]. In adolescence, the etiology of TMD can include dental anomalies, bad habits, growth abnormalities, and stress [

10].

The symptoms of TMD include pain in the TMJ and masticatory muscles [

11], joint sounds (crepitus and clicking), locking [

12,

13,

14] restrictions on jaw mobility [

15,

16,

17], and disc displacement (DD) [

18,

19,

20,

21].

The diagnosis of TMD is a complex process that requires a comprehensive evaluation of the TMJ signs and symptoms, acquired through clinical tests, examinations, and medical image analyses [

22]. Imaging modalities for the evaluation of TMD include panoramic imaging, arthrography, computed tomography (CT) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis is a chronic degenerative disease that can result from TMD, TMJ disc displacement, trauma, functional overload, and developmental anomalies [

27]. It affects the cartilage, the subchondral bones, the synovial membrane, and other hard and soft tissues [

28], with manifestations such as bone remodeling and cartilage damage [

29].

The equilibrium of the masticatory system can be disrupted by a variety of factors; however, one factor generates significant debate. Occlusal disharmonies are recognized as an etiological factor, but the extent and manner in which they contribute to TMD remain unclear [

30]. Occlusal dynamics affect multiple interfaces, including the teeth, periodontium, masticatory muscles, and the temporomandibular joint. The mechanical stress exerted on these interfaces can compromise their integrity [

31]. Occlusal interferences and occlusal dysfunctions can lead to orthopedic joint instability and the hyperactivity of the masticatory muscles, which can result in TMD [

32].

The relationship between occlusion and TMD remains ambiguous, which has resulted in conflicting study findings [

33,

34]. The clinical signs of TMD have been correlated with certain occlusal factors and parafunctional habits: occlusal variables that increase the likelihood of different signs of TMD may be interferences in centric relation (CR), discrepancy between midline ≥ 2 mm, ≤10 contacts during maximum intercuspation, interferences on the non-working (passive) side and overjet ≥ 5 mm [

35], parafunctional habits (grinding and clenching), occlusal tooth wear [

36,

37,

38], and unilateral posterior crossbite [

38,

39,

40]. TMD has been also associated with deep overbite [

35,

41], posterior scissor bite, angle class II malocclusion [

35,

42], anterior open bite [

43], unstable occlusion [

44], neck posture [

45], and excessive overjet [

46].

Functional malocclusions have a greater influence on cranio-mandibular dysfunction than morphologic malocclusions [

47]. To differentiate TMD patients from those who function normally, however, no unique occlusal characteristic was feasible [

48,

49]. A biological organism will continuously adapt to various morphologic elements until equilibrium is achieved [

34]. Changes in head posture impact the balance of occlusal contacts [

34].

Previous research in occlusion and TMD varies and tends to be based on individual variables or specific inclusion criteria that limit generalizability [

50]. TMD classification variability and methodological inconsistencies are significant contributors to incompatible findings [

51]. The goal of this scoping review was to map the literature and clarify the role of occlusion in the development of TMD. This study’s objectives were to find a relationship between temporomandibular dysfunction and occlusal balance and understand how the occlusion influences temporomandibular joint pathology and/or masticatory and cervical muscle symptoms.

4. Discussion

Our scoping review managed to extract a synthesis of the existing literature on TMD and various parameters. The studies included in this review represent a range of geographical locations, and thus include subjects with various social, cultural, and geographical backgrounds, possibly allowing for controlling for genetic, environmental, and behavior-related factors that could affect the disorder. Study types were observational (comparative, prospective, retrospective, cross-sectional, and case–control studies). Publications have linked a range of causative factors for temporomandibular dysfunction, including a change in vertical occlusal dimension and posterior edentulous spaces, occlusal abnormalities, dento-maxillary malocclusions, angle classes, pain, spasms, and the female gender.

4.1. TMJ Involvement Correlated with Posterior Edentulism and VDO Changes

The following inferences can be drawn from the literature: the loss of posterior support and secondary occlusal vertical dimension shifts contribute to the development and progression of TMD [

79,

81]. The loss of occlusal stability in untreated edentulous spaces can produce compensatory neuromuscular adaptations, increased loading of joints, and occlusal disharmony, all of them proven to be TMD contributing factors [

35]. The progression of TMD with compromised VDO underlines occlusal collapse in a biomechanical manner, with aging groups at a high risk [

54]. Based on these observations, early interventions in terms of prosthetics for restoration of edentulous spaces and maintaining a functional VDO could be critical in preventing and controlling symptoms of TMD. Long-term occlusal rehabilitation and its role in preventing the progression of TMD have to be addressed in future studies.

4.2. The Influence of Occlusal Abnormalities on the Temporomandibular Joint

The identified papers show the important role of occlusal stability in TMJ functionality. Occlusal discrepancies such as increased overjet, overbite, and premature contacts have been seen to cause the excessive loading of joints and changed mandibular function, all contributing to increased symptoms of TMD [

35,

57,

60,

78]. Asymmetric mandibular movements and mandibular occlusal contact discrepancies (MI-CR) may be due to osteoarthritis, and it can be postulated that long-term occlusal disharmony can cause disease in joints [

59]. Bruxism, dental wear, and unilateral mastication have a strong relationship with TMD [

61]. Parafunction can cause and maintain disease in joints and muscles and cause occlusal disharmony. Based on these observations, occlusal realignment, functional rehabilitation, and early intervention for occlusal interferences can have a significant role in preventing and managing TMD.

4.3. The Influence of Occlusal Abnormalities and Malocclusions on the Temporomandibular Joint

The selected papers suggest malocclusions and occlusal abnormalities have a significant contribution to TMJ dysfunction through a disruption in mandibular movements and an increase in joint tension. Open bite and crossbite have been observed to affect joint stability, most likely through a lack of occlusal support and secondary adaptations in joints, ligaments, and muscles [

63,

73,

74,

75]. Malocclusion variation in TMJ function between angle classes shows discrepancies in the sagittal plane have an impact on joint mobility, with hypermobility in cases of angle class II/1 and hypomobility in cases of angle class III, and could lead to long-term destructive processes [

72]. Increased overjet and overbite and bruxism have been observed to contribute to TMD occurrence [

69]. Occlusal discrepancies and malocclusion must be resolved in an attempt to prevent or at least minimize TMD development. Untreated malocclusions could predispose an individual to long-term secondary muscular and joint pain. Occlusal balancing, occlusal adjustment, and/or restoration could become a critical consideration in TMJ maintenance and function.

4.4. Relationship Between Joint Impairment and Angle Class

The literature reveals that occlusal classifications make a significant etiological contribution towards temporomandibular disorder development, with specific malocclusion types predisposing subjects towards pathology in joints and muscles. A low prevalence of TMD in angle class I subjects reveals a role for a harmonious occlusion in TMJ stability [

35], in contrast with increased susceptibility in angle class II subjects towards joint pain, sounds, and myofascial pain [

77,

78]; these results suggest that mandibular retrusion and the changed position of the condylar head produce a strain in occlusal disharmony in angle class II subjects. Angle class II and III malocclusions both have a relation with painful myofascial symptoms [

64]. Discrepancies in both sagittal and vertical dimensions contribute towards both joint instability and strain in the muscles and reveal a contribution of malocclusion and occlusal imbalance in TMJ pathology.

4.5. Relationship Between Masticatory Muscle Pain and Contracture

These studies validate significant occlusal discrepancies, muscle dysfunction, and TMD pain, supporting the multi-faceted etiology of the disorder. The association between dento-maxillary malocclusions and orofacial pain [

55] and between occlusal disharmony and overload in masticatory muscles validates changed occlusal function in the causation of myalgia and restriction in function. The association between increased masticatory myalgia in skeletal class II and III malocclusions [

64] and in deep bite and crossbite [

66,

78] validates occlusal disharmony in causing strain in muscles. A high prevalence of palpation myalgia in TMD subjects [

56,

61,

80] validates the significant muscular contribution in the disorder, with variable groups of muscles having variable types of myalgia in relation to occlusal disharmony and functional adaptations. Muscle spasm, mandibular deviation, and progressive impairment in masticatory muscles validate the long-term contribution of muscle dysfunction in increased symptoms in TMD [

72], with long-term impact for joint stability. All these studies validate the use of multidimensional evaluations in TMD, taking both occlusal and muscular factors into consideration, and early intervention programs in occlusal correction, relaxation in muscles, and behavior therapy for occlusal disharmony, myalgia, and improvement in function.

4.6. Degree of Joint Damage in Females

That female-to-male ratios have consistently been documented in a variety of studies at a level suggesting a gender predisposition, possibly hormonal, anatomical, or functional in etiology. The female–male prevalence for TMD span in a range between 2:1 [

81] and an extreme 20:1 [

54]. Female-related symptoms, such as mandibular deviation during opening and joint sounds, which are present in most cases [

60], point towards a role for such factors in TMD pathophysiology. Muscle pain and the female gender, even in cases with no restriction in mouth opening, underline neuromuscular factors in TMD pathophysiology. Females have a high likelihood of reporting individual symptoms referable to joints, such as hyperlaxity and deviation. All such observations point towards a gender-related consideration in diagnosing and managing TMD, with a consideration for a role for estrogen fluctuations, ligamentous laxity, and variation in female gender-related perception of pain in female patients.

4.7. Comparison with Published Reviews

Recent systematic reviews, such as those conducted by Manfredini et al. (2017) [

82] and Trivedi et al. (2022) [

83], are in agreement with our scoping review in concluding that occlusal considerations alone are not the only associated factor of TMD. While our review shows associations between TMD symptoms and occlusion type (deep bite, crossbite, and angle class II and III relationships), Manfredini et al. identified only mediotrusive interferences as being related to TMD, and in this instance, causation could not be established [

82]. Similarly, in a meta-analysis, Trivedi et al. identified an increased prevalence in TMD sufferers for deep overbite and class II/III relationships, but recognized limitations in making definitive conclusions based upon the fact that the investigations were heterogeneous [

83]. Lekaviciute et al. (2024) [

84] additionally emphasized tooth loss and bruxism as factors associated with TMD, underlying the multi-factorial nature of the disorder, which we have identified in our findings as well. The biggest shortfall in each review, including ours, is still the lack of longitudinal and interventional research to be able to definitively state if occlusal factors have an impact upon TMD occurrence.

4.8. Limitations

A significant limitation is that the studies included in the analysis have a variation in terms of study design, sample, and methodology. Discrepancies in terms of reporting, measurement, and diagnostic criteria can arise, and direct comparisons are not possible. Variability can hinder generalizability and make it unfeasible to make definite statements about causality between occlusal factors and TMD.

Another limitation of this review is that the included studies have an observational nature, and causality between occlusal factors and TMD cannot therefore be confirmed.

Confounders, which are a common issue in observational studies, like parafunctional behavior (bruxism), can have a profound influence upon the occlusion/TMD association as a mediator or as a separate risk factor. Unless they are corrected for, they can distort and not accurately reflect the actual influence of occlusion on TMD and can yield over- or under-estimation.

Whereas the extraction of information focused on key study parameters, an omission of a full evaluation for bias in a review entails that the defects in the methodologies of individual studies could not have been effectively addressed. As mapping current studies is the purpose of this scoping review and not an appraisal of the quality of the evidence, a risk of bias analysis was not performed.

4.9. Study Strengths

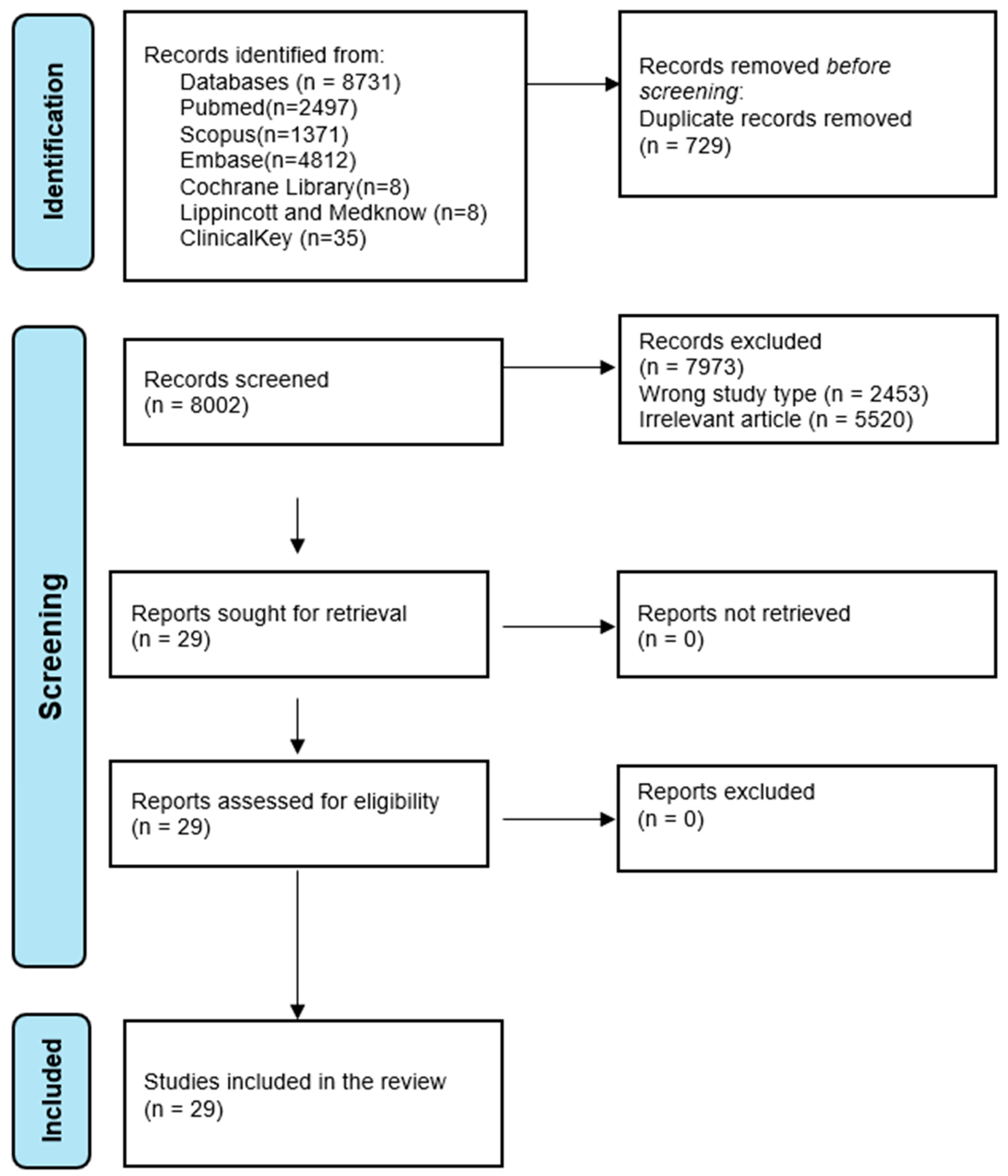

First, this study adheres to the PRISMA-ScR, with a systemic and transparent selection, extraction of information, and reporting. By searching in a range of key databases (PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Embase), a high proportion of relevant studies is captured. By using a search strategy with MeSH terms and synonyms, an increased search sensitivity is achieved, and a high level of issue coverage is assured. Having a variety of types of studies allows for a full mapping of current studies, trends, gaps, and important findings regarding occlusion and TMD. With a variety of occlusal factors, such as malocclusions, overjet, overbite, and occlusal interferences, a holistic view of occlusal factors in developing TMD was considered. One strength the review holds is its novelty, as the literature on occlusal variables and TMD has rarely been charted by other studies, providing and comprehensive summary of the multi-faceted relation.

4.10. Future Research

In the future, more research should be aimed at performing well-designed prospective and interventional studies with established occlusal parameters and TMD classification diagnostic criteria. There is a need for better methodological consistency, including clear definitions, uniform measurement tools, and controls for confounding variables such as bruxism and gender. Longitudinal studies should provide insight into the temporal interaction between occlusal defects and the development or worsening of TMD, an essential missing piece in the current evidence.

This review forms part of an ongoing discussion in occlusion in TMD and is beneficial for clinicians and researchers in providing useful information. By providing an overview of current studies, it forms a basis for future systemic reviews and clinical studies, and aids in formulating more specific therapeutic and diagnostic approaches for TMD management.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review emphasizes the complex occlusal–temporomandibular disorder relation, with a variety of occlusal abnormalities, such as malocclusions, overjet, overbite, crossbite, and occlusal interferences, having a direct relation with masticatory pain and joint dysfunction. Angle class I occlusion seems to have a lesser incidence of TMD, but angle class II and angle class III malocclusions, deep bites, and edentulous spaces have a predisposition towards symptoms of TMD, such as mandibular deviation, masticatory muscle pain, and tenderness. In addition, this study confirms multi-faceted character of TMD, with occlusal factors, combined with parafunction habits and systemic factors, such as aging and gender predisposition. Causality between occlusion and TMD could not be established based on observational studies.