Abstract

Background and Objectives: The history of facial fillers is very broad, ranging from the use of various materials to modern technologies. Although procedures are considered safe, complications such as skin inflammation, infection, necrosis, or swelling may occur. It is crucial for specialists to be adequately prepared, inform patients how to prepare for corrective procedures, adhere to high safety standards, and continually educate. The goal of this systematic review is to identify complications arising during facial wrinkle correction procedures, as well as to explore safety and potential prevention strategies. Materials and methods: The review of the scientific literature followed the PRISMA guidelines. The search was performed in a single scientific database: PubMed. Considering predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, articles evaluating the safety of dermal fillers used for facial wrinkle correction, complications, and treatment outcomes were selected. The chosen articles were published from 15 February 2019 to 15 February 2024 (last search date: 25 February 2024). The selected articles compared the complications, product safety, and result longevity of various dermal fillers used for facial wrinkle correction. Results: In thirty-eight articles, which involved 3967 participants, a total of 8795 complications were reported. The majority of complications occurred after injections into the chin and surrounding area (n = 2852). Others were reported in lips and the surrounding area (n = 1911) and cheeks and the surrounding area (n = 1077). Out of the 8795 complications, 1076 were adverse events (AE), including two severe AE cases: mild skin necrosis (n = 1) and abscess (n = 1). There were no cases of vascular occlusion, visual impairment, or deaths related to the performed procedures. A total of 7719 injection site reactions were classified as mild or temporary, such as swelling (n = 1184), sensitivity (n = 1145), pain (n = 1064), bleeding (n = 969), hardening/stiffness (n = 888), nodules/irregularities (n = 849), and erythema (redness) (n = 785). Conclusions: Facial wrinkle correction procedures are generally safe and effective and the results can last from 6 to 24 months, depending on the dermal filler material and its components used. The most common complications after dermal filler injection usually resolve spontaneously, but if they persist, various pharmacological treatment methods can be used according to the condition, and surgical intervention is generally not required.

1. Introduction

In 2019, approximately 1.6 million dermal filler injections were performed, representing a 78% increase compared to 2012 [1]. Although filler procedures are considered safe, there are potential risks and complications. According to a study conducted by Akash A. Chandawarkar et al., complications occur at a rate of 1:100 to 1-4:10000, depending on the filler material used [2]. Complications associated with the use of dermal fillers are relatively rare, as evidenced by the steadily increasing number of procedures performed annually in the United States [3]. The most frequently encountered complications include inflammation (16.0%), swelling (14.1%), infection (13.4%), pain (7.9%), and erythema (5.5%), while necrosis accounted for 3.5% of adverse events. Analysis indicates that the proportion of complications such as swelling, pain, and erythema has decreased in the MAUDE (Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience, USA) database, but there is greater concern over reports of severe complications, such as infection and tissue necrosis [1]. Although such complications are rare, undesirable outcomes, including esthetic (deformities, scarring, etc.) and psychological effects, can be long-lasting [4,5].

Facial dermal fillers are substances injected into the skin to restore lost volume, smooth lines and wrinkles, and enhance facial contours. They can be classified based on their composition, longevity, and application area. Here is a detailed classification [6,7,8,9,10]:

- Based on Composition

- 1.1

- Hyaluronic Acid (HA) Fillers

- Description: HA is a naturally occurring substance in the skin that helps maintain hydration and volume. These fillers are popular due to their natural-looking results and reversibility with hyaluronidase.

- Longevity: 6 to 18 months.

- 1.2

- Calcium Hydroxylapatite (CaHA) Fillers

- Description: CaHA is a mineral-like compound found in bones. These fillers provide a more robust fill and stimulate collagen production.

- Longevity: Up to 18 months.

- 1.3

- Poly-L-Lactic Acid (PLLA) Fillers

- Description: PLLA is a biodegradable synthetic substance. These fillers work by stimulating collagen production, resulting in gradual and long-lasting volume restoration.

- Longevity: Up to 2 years.

- 1.4

- Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) Fillers

- Description: PMMA is a biocompatible synthetic substance. These fillers provide permanent volume correction by forming a collagen scaffold around the microspheres.

- Longevity: Permanent.

- 1.5

- Autologous Fat Injections

- Description: Fat is harvested from the patient’s body (typically abdomen or thighs) and then purified and injected into the face.

- Longevity: Permanent with a variable resorption rate.

- Based on Longevity

- 2.1

- Temporary Fillers

- Examples: Hyaluronic Acid Fillers

- Description: Lasts 6 to 18 months, providing temporary volume and wrinkle reduction.

- 2.2

- Semi-Permanent Fillers

- Examples: Calcium Hydroxylapatite, Poly-L-Lactic Acid

- Description: Lasts 1 to 2 years, offering longer-lasting results but not permanent.

- 2.3

- Permanent Fillers

- Examples: Polymethylmethacrylate, Autologous Fat Injections

- Description: Provides long-lasting to permanent results, ideal for patients seeking a more enduring solution.

- Based on Application Area

- 3.1

- Lip Fillers

- Description: Specifically formulated to add volume and definition to the lips.

- 3.2

- Cheek Fillers

- Description: Designed to restore volume to the cheeks and midface area.

- 3.3

- Nasolabial Fold Fillers

- Description: Target the deep lines running from the nose to the mouth.

- 3.4

- Under-Eye Fillers

- Description: Used to treat tear trough deformities and hollows under the eyes.

- 3.5

- Chin and Jawline Fillers

- Description: Enhance the chin and define the jawline for a more contoured appearance.

- 3.6

- Forehead and Temple Fillers

- Description: Restore volume and smooth out wrinkles in the forehead and temple areas.

Classification of Complications Associated with Facial Dermal Fillers

Facial dermal fillers, while generally safe, can lead to various complications. These complications can be categorized based on their timing (immediate, early, and late), severity, and nature (esthetic, inflammatory, and systemic) [9,11].

- Based on Timing

- 1.1

- Immediate Complications (Within hours to days)

- Pain and Discomfort: Mild to moderate pain at the injection site.

- Redness and Swelling: Common, typically subsiding within a few days.

- Bruising: Caused by needle trauma, usually resolves within a week.

- Allergic Reactions: Rare, can cause localized or systemic reactions.

- 1.2

- Early Complications (Within days to weeks)

- Infection: Redness, swelling, and tenderness persisting beyond a few days may indicate infection.

- Nodules and Lumps: Palpable lumps under the skin due to filler material or inflammation.

- Asymmetry: Uneven results from the filler distribution.

- 1.3

- Late Complications (weeks to months)

- Granulomas: Chronic inflammatory nodules that can form around the filler material.

- Migration: Movement of the filler from the original injection site.

- Persistent Edema: Ongoing swelling in the treated area.

- Based on Severity

- 2.1

- Mild Complications

- Bruising

- Temporary Redness and Swelling

- Minor Discomfort

- 2.2

- Moderate Complications

- Infection

- Persistent Nodules

- Asymmetry

- 2.3

- Severe Complications

- Vascular Compromise: Includes tissue necrosis due to accidental injection into blood vessels, leading to tissue death.

- Blindness: Rare but serious, resulting from filler entering retinal arteries.

- Severe Allergic Reactions: Anaphylaxis, requiring immediate medical attention.

- Based on Nature

- 3.1

- Esthetic Complications

- Overfilling: Excessive filler resulting in an unnatural appearance.

- Underfilling: Insufficient filler leading to inadequate correction.

- Irregularities and Contour Deformities: Uneven distribution of filler.

- 3.2

- Inflammatory Complications

- Acute Inflammation: Immediate response to the injection.

- Chronic Inflammation: Long-term response, often leading to granuloma formation.

- Infection: Bacterial infection requiring antibiotics or drainage.

- 3.3

- Systemic Complications

- Allergic Reactions: Localized (e.g., itching, redness) or systemic (e.g., anaphylaxis).

- Vascular Complications: Vascular occlusion leads to tissue necrosis or more severe outcomes like blindness.

- Autoimmune Responses: Rare, but fillers can trigger autoimmune responses in susceptible individuals.

The aim of this systematic review of the scientific literature is to examine the data presented in scientific sources about facial dermal fillers and investigate the safety and potential complications associated with facial wrinkle correction procedures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Review Protocol

This study was conducted in alignment with the guidelines set forth by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The PICO methodology was applied to formulate the research question, considering the study’s population, intervention, control, and outcomes, and the problem question was developed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the problem question formulation using the PICO analysis method.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria for Articles

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Scientific articles not older than 5 years were selected. Studies are described in full articles in English and Lithuanian. Studies involving people who underwent facial wrinkles correction with dermal fillers, evaluating safety and frequency of complications, and applying complication treatment. Randomized controlled trials and review studies. Studies involving humans.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Studies with fewer than 30 subjects. Studies on wrinkle correction fillers outside the facial area. Systematic reviews of scientific literature, meta-analyses, case studies, poster presentations, conference presentations, abstracts, expert opinions. Studies involving animals, deceased individuals, or models. Studies describing complications not related to facial dermal filler injections.

2.3. Search Strategy

The search for scientific publications suitable for the systematic review of scientific literature was conducted by two researchers, with a third researcher consulted in case of differences or conflicts during the research. The search was carried out in four scientific literature databases: PubMed, Medline, ScienceDirect, and Cochrane. Selected articles were published from 1 February 2019 to 1 February 2024 (the last data search was conducted on 3 March 2024).

The selection of publications was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, scientific articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, and titles and abstracts were reviewed to remove publications not relevant to the chosen topic. In the second stage, the full texts of the articles were read, analyzed, and either included in the systemic review or excluded based on the established inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment in Research

The risk of bias assessment in randomized trials was conducted using the “RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomized Trials” questionnaire [12]. This tool is designed to evaluate the level of bias in a publication and its suitability for inclusion in systematic reviews when assessing randomized trials.

The assessment of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions was conducted using the “Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool” questionnaire [13]. This tool is designed to evaluate the level of bias in a publication and its suitability for inclusion in systematic reviews when assessing non-randomized studies.

2.5. Criteria for Evaluating the Results of Articles

The following criteria were evaluated in selected scientific publications:

- Injection site reactions (ISR), a type of adverse event (AE) occurring specifically at the site where facial filler was injected. Common examples include redness, swelling, and pain. These reactions are typically mild and resolve spontaneously.

- Adverse Event (AE) is a broad term describing any unwanted occurrence, whether in appropriately or inappropriately administered facial filler. Therefore, all ISRs are AEs, but not all AEs are ISRs. For instance, prolonged ISR beyond physiological norms can become an AE. All adverse reactions can range in severity from mild (redness, swelling, etc.), to moderate (asymmetry, nodules, etc.), to severe (allergic reactions, vascular occlusion, blindness, infection, etc.), as well as short-term and long-term. AEs can manifest throughout the body and are not limited to the injection site.

- Safety of products used in facial wrinkle correction procedures during clinical trials. Safety evaluation during clinical trials is crucial for several reasons: safeguarding consumer welfare, compliance with regulatory requirements, development of improved products, long-term effects, and others.

2.6. Data Systematization and Analysis

Data Search Results

During the initial stage of searching scientific publications using a selected combination of keywords, 1418 publications were found. Applying selection criteria (publications not older than 5 years, not systematic reviews or meta-analyses, another type of review, and no duplicates), 65 articles were obtained. During this stage, the titles and abstracts of these publications were reviewed. After this stage, publications were excluded due to a mismatch with the topic (n = 16), leaving 49 publications that were selected for full-text analysis.

During the second stage of searching scientific articles, three publications were excluded because their full text was inaccessible, resulting in 46 articles being read and analyzed. Applying exclusion criteria, publications were rejected because the study included fewer than 30 participants (n = 8). A total of 38 publications were included in the systematic review [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. The search process diagram, following PRISMA requirements, is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Systematic review article search process diagram.

2.7. Risk of Bias Evaluation

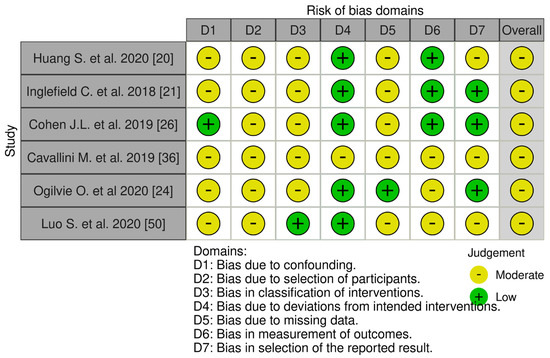

Systematic risk of bias assessment utilized the following tools: “RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials” for randomized trials, and the “Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool” for non-randomized clinical studies. The majority (n = 27, 84.38%) of selected randomized trials exhibited low risk of bias, with 15.62% (n = 5) showing moderate risk [32,44,47,49,51]. All non-randomized clinical studies showed moderate risk of bias (n = 6, 100%). Randomized and non-randomized studies with moderate risk of reporting bias did not influence the conducted systematic review. A visual assessment of systematic biases in randomized and non-randomized studies, using the “Risk-of-bias Visualization (robvis)” tool [52], is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Systematic risk assessment of non−randomized clinical trials [20,21,24,26,36,50].

Figure 3.

Assessment of Systematic Risk in Randomized Controlled Trials, refs. [14,15,16,17,18,19,22,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,51].

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Studies

This systematic review included 38 studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. The majority (n = 32) of selected studies were randomized controlled trials, and six were non-randomized clinical trials [20,21,26,36,37,50]. Most studies had two allocated groups: one control and one experimental, while several studies did not provide complete information [20,21,22,36,37,50].

All studies examined procedures for facial wrinkle correction, detailing the type of filler and technique used, their safety, and reported procedure-related complications. Detailed characteristics of the studies included in the review are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary overview of results from studies included in the systematic review.

3.2. Characteristics of the Study Population

In total, 3967 patients were studied, including 243 (6.13%) men and 3621 (91.28%) women; three studies did not provide this data [23,40,51], accounting for 103 participants (2.60%). Authors reported age distribution differently across studies, some providing only means while others varied in age range, thus this criterion was not included in the systemic review.

The most common inclusion criteria in the articles for patient enrollment were the presence of facial wrinkles under study, absence of systemic diseases, no prior corrective procedures, absence of scars or tendency for scarring, and known allergies to materials used in the study (e.g., lidocaine or hyaluronic acid).

The most common exclusion criteria in the articles for patient exclusion were pregnancy, breastfeeding, planning to conceive during the study period, use of certain medications (e.g., anticoagulants), known hypersensitivity, and other factors that could influence study results such as facial inflammation and prior specific facial procedures (e.g., laser or chemical facial procedures). Other authors additionally specified these exclusion criteria: psychiatric disorders or emotional instability [30], sun-damaged facial skin [32,36], smoking [39].

In five studies (n = 5; 13.16%), inclusion or exclusion criteria were not specified [23,25,37,43,44].

3.3. Review of Studied Areas, Materials, Sites of Injection, and Instruments

Based on the data from studies included in the systematic review, the majority of facial wrinkle correction procedures utilized materials based on hyaluronic acid (n = 30; 78.95%). Other materials used in studies included polycaprolactone (n = 3; 7.89%), poly-L-lactic acid (n = 2; 5.26%), and others (n = 3; 7.89%).

The most common areas chosen for wrinkle correction in studies were the nasolabial folds (n = 17). Less frequently treated areas included cheeks and surrounding regions (n = 8), lips and perioral wrinkles (n = 7), chin and surrounding area (n = 5), periorbital area (n = 2), inter-brow area (n = 3), mid-face region (n = 3), and lateral orbital area (n = 2). Eleven studies selected more than one facial wrinkle [20,21,24,25,26,31,32,35,36,37,44]. Detailed characteristics of the studies included in the review are presented in Table 2.

The most common site for injecting fillers for facial wrinkle correction was the dermis (n = 16), followed by the subcutaneous layer (n = 14), periosteum (n = 8), and other locations (n = 3). Ten studies did not specify the injection site. Thirteen studies involved multiple injection sites [14,17,18,21,22,24,25,26,27,30,34,35,42].

A 27G needle was most frequently used (n = 15) for injecting the study material into the target area. Other needle sizes used were 30G (n = 7), 32G (n = 4), and 25G (n = 3), and the instrument was unspecified in 12 studies. Several studies employed cannulas of varying sizes (n = 3). Six studies allowed for the use of multiple needle or cannula sizes [14,21,25,34,44,49]. Needle lengths were mostly unspecified (n = 23) in the studies, while 14 studies used ½ inch (12.7 mm) needles, and in 2 studies, needles of lengths 1.0–1.5 inches (25.4–38.1 mm) and 3/16 inch (4.76 mm) were used.

3.4. Overview of Complications Reported in Studies

In the studies, injection site reactions (ISR) and adverse events (AE) were recorded. ISRs are interpreted as potential physiological responses and are typically anticipated before corrective procedures, while AEs are complications exceeding those anticipated in studies or prolonged ISRs and all other related phenomena associated with the study.

This systemic review identified 8795 complications of varying degrees, with 7719 ISRs and 1076 AEs. The distribution of Injection Site Responses among selected studies included: edema (n = 1184; 15.34%), sensitivity (n = 1145; 14.83%), pain (n = 1064; 13.78%), hematoma (n = 969; 12.55%), induration (n = 888; 11.50%), nodules/irregularities (n = 849; 11.00%), erythema (n = 785; 10.17%), pruritus (n = 439; 5.69%), changes in color or pigmentation (n = 324; 4.20%), and other (n = 72; 0.93%).

Among the adverse events (AEs) recorded in selected studies, the distribution was as follows: pain (n = 211; 19.61%), hematoma (n = 210; 19.52%), edema (n = 194; 18.03%), erythema (n = 121; 11.25%), nodules/irregularities (n = 54; 5.02%), sensitivity (n = 35; 3.25%), lump (n = 33; 3.07%), induration (n = 27; 2.51%), color changes (n = 25; 2.32%), headache or migraine (n = 22; 2.04%), pruritus (n = 19; 1.77%), and other (n = 125; 11.62%). AEs in the “other” category, comprising 11.62% (n = 125), included: acne (n = 16; 1.49%), nodule (n = 16; 1.49%), bleeding (n = 10; 0.93%), paresthesia (n = 9; 0.84%), cellulitis (n = 7; 0.65%), inflammation (n = 7; 0.65%), speech disorder (n = 6; 0.56%), abscess (n = 6; 0.56%), and other AEs (n = 48; 4.46%) such as petechiae (n = 3; 0.28%), rhinitis (n = 2; 0.19%), hemorrhage (n = 2; 0.19%), cough (n = 1; 0.09%), cyst (n = 1; 0.09%), bronchitis (n = 1; 0.09%), papule (n = 1; 0.09%), toothache (n = 1; 0.09%), etc. Mild necrosis was observed only once (n = 1; 0.09%) among AEs in all selected studies. In one study, one patient required hospitalization due to an AE [14]. There were no recorded deaths, vision impairments, or complete losses of sensitivity in the study area.

In two studies focusing on nasal and peri-nasal corrections, 2755 ISRs and 97 AEs [14,18] were observed, comprising 32.43% (n = 2852) of all complications in the systemic review. Distribution of ISRs: sensitivity—517, swelling—439, pain—428, induration—373, nodules/irregularities—305, hematoma—290, itching—233, erythema—108, and color changes—62. Distribution of AEs: pain—20, lump—10, inflammation—7, swelling—7, abscess—6, acne—6, cellulitis—6, speech disorder—6, and other—29.

For corrections performed on the lips and peri-labial areas, 1911 documented complications (21.73%) were recorded: ISR—1790 and AE—121 [16,17,22,39,40,43]. Distribution of ISRs: hematoma—276, swelling—258, erythema—221, nodules/irregularities—217, induration—217, sensitivity—213, pain—146, color changes—135, and other—107. Distribution of AEs: hematoma—32, pain—27, nodules/irregularities—26, swelling—19, and other—17.

Following mid-facial area corrections (cheeks and peri-cheek areas), 1077 complications (12.25%) were documented: 918 ISRs and 159 AEs [27,32,35,41,42]. Distribution of ISRs: erythema—135, swelling—125, nodules/irregularities—124, hematoma—116, pain—106, sensitivity—106, induration—95, color changes—66, and itching—45. Distribution of AEs: pain—60, swelling—33, erythema—22, hematoma—14, headache—9, and other—21.

In the nasolabial fold area, 744 complications (8.46%) occurred, with 600 ISRs and 144 AEs [15,28,30,33,38,45,47,48,49]. Distribution of ISRs: pain—160, swelling—127, sensitivity—83, erythema—81, itching—64, hematoma—52, papule—26, and color changes—7. Distribution of AEs: swelling—63, color changes—18, erythema—15, pain—15, hematoma—9, sensitivity—7, and other—17.

In other facial areas, following wrinkle correction procedures, 2211 (25.14%) complications were documented: 317 (3.60%) in the periocular region [34,50,51], 29 (0.33%) in the lateral orbital area [23], and 1865 (21.21%) in studies where facial fillers were used in multiple facial areas simultaneously.

3.5. An Overview of Treatment Methods for Complications Reported in Studies

In most selected studies, information on treatment was predominantly spontaneous (n = 26; 60.47%), without any intervention by researchers, involving resolution or healing of injection site reactions or adverse reactions. Treatment of complications was not mentioned in nine studies (n = 9; 20.93%). Among the reported treatments requiring researcher intervention, the most common was hyaluronidase treatment (n = 3; 6.98%), used for persistent inflammation in the study area, unresolved nodules, and cysts [14,18,24]. Additionally, antibiotic therapy was applied (n = 2; 4.65%), systemic steroids (n = 1; 2.33%), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (n = 1; 2.33%), and mometasone furoate glucocorticoid (n = 1; 2.33%) [14,24,34,42]. In one study by Kenneth Beer and others, a patient was hospitalized, and an abscess was drained [14].

3.6. Overview of Safety Findings from Studies

According to data presented in the conclusions of thirty-eight reviewed studies, the materials used in the studies were mostly evaluated as safe or with minimal safety concerns (n = 29; 76.32%). The effectiveness of the materials used in correcting wrinkles in the facial area under study was mentioned in twenty-two conclusions (n = 22; 57.89%), and they were well tolerated in four conclusions (n = 4; 10.53%).

It was noted in the conclusions that the results of the materials used in the studies last at least 6 months [26,36] but can last for up to 24 months [20,42]. Persistence at 12 months was mentioned in five studies (n = 5; 13.16%) [14,24,27,34,49]. However, the most common procedure’s long-term results were not specified (n = 23; 60.53%).

In seven (n = 7; 18.42%) studies’ conclusions, it is emphasized that additional research or long-term monitoring of the obtained results is necessary [15,16,21,33,36,50,51]. In one study (n = 1; 2.63%), it is mentioned that the use of stereophotogrammetry in further research would be beneficial for more accurately evaluating the results.

4. Discussion

This systematic review analyzed 38 scientific publications, including 32 randomized trials and 6 non-randomized clinical trial studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. The main objective of this work was to review the data presented in scientific sources about facial dermal fillers and to investigate the safety of facial wrinkle correction and potential complications associated with the procedure.

The majority of dermal fillers studied in the publications (n = 35; 92.11%) were temporary (results typically lasting from 6 to 18 months), two (5.26%) were semi-permanent (results typically lasting up to 24 months and longer) [36,49], and one (2.63%) was permanent [51]. Based on studies conducted by other authors, it can be concluded that as facial tissues continuously change, safer materials are those that can be biologically degraded more quickly by the body over time, resulting in fewer long-term complications [53]. Additionally, many authors consider safer those materials that can be broken down in case of unforeseen complications, such as hyaluronic acid filler with hyaluronidase, thereby avoiding surgical intervention which can leave scars, cause psychological consequences, or lead to other complications associated with such interventions.

Corrective procedures involving facial dermal fillers can lead to adverse events. While most consequences can be mild, such as ISRs (e.g., erythema, swelling, pain) and disappear over time, rare (e.g., vision impairment or tissue necrosis) and severe complications cannot be ignored as their effects can be irreversible (e.g., blindness, scarring) or life-threatening. In this systematic review, there was no significant number of severe complications, such as vascular occlusion, tissue necrosis, vision impairment, and infection, which can significantly impact quality of life and health, as described in the literature and other studies [53,54]. Specialists must be aware of all these risks and properly inform patients about potential risks, as timely detection and appropriate treatment can prevent severe and irreversible consequences.

In this systematic review, the most common negative tissue reactions at the injection site resolved spontaneously, and some adverse events were treated with s, NSAIDs, hyaluronidase, etc. Only one patient (0.003%) required treating due to an abscess that needed special treatment, including intravenous antibiotics and abscess drainage. Thus, it can be concluded that a specialist must have appropriate education, be able to provide emergency care, and know where and when to refer patients to other specialists if severe complications develop.

Common injection site reactions included edema, sensitivity, pain, hematoma, induration/stiffness, nodules/irregularities, and erythema. These accounted for 89.17% of the complications.

Among the adverse events, the most common were pain, hematoma, edema, erythema, nodules/irregularities, sensitivity, and lumps. Together, these accounted for 79.75% of these complications.

The included studies did not establish a connection between the use of cannulas and a reduced risk of complications compared to the use of needles due to the small sample size. Therefore, more studies are needed to evaluate this. According to other researchers, the use of cannulas for filler injection may reduce the incidence of bruising. These authors believe that the sharp tip of the needle can cause more tissue trauma [55]. Although both needles and cannulas can be used for facial corrective procedures, cannulas may be safer and reduce the risk of intravascular complications [56].

The methods for treating complications were varied, but the most frequently occurring complications spontaneously resolved (60.47%) without investigator intervention. In both the studies reviewed in this systemic review and the results of other researchers’ studies, hyaluronidase was often chosen as the first-line treatment for complications related to hyaluronic acid fillers. Concurrently, medical treatment, depending on the condition, included antibiotics, systemic steroids, NSAIDs, and glucocorticoids [57,58].

In most studies (76.32%) [14,15,16,18,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,28,30,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49], it was concluded that the materials used were safe or had minimal safety-related risks. These safety conclusions were largely consistent with those of other researchers [53,55].

The longevity of the results of facial wrinkle correction varied, with some studies indicating that the effects lasted from several months to 24 months, which was associated with the type of material used and its quantity.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of selected studies on facial wrinkle correction reveals that hyaluronic acid-based materials are the most commonly used. This preference is likely due to the ability to manage varying degrees of complications with hyaluronidase effectively. The nasolabial folds emerged as the most frequently treated anatomical region in these procedures, as highlighted in the systematic review.

While mild, short-term complications were commonly expected and typically resolved on their own, there were instances of moderate to severe complications requiring targeted treatment. Overall, the findings suggest that facial correction procedures are generally safe. However, the outcomes can be significantly influenced by several factors, including the qualifications of the practitioners, the properties of the materials used, variations in techniques and methodologies, and the level of cooperation among patients.

Further research is needed to investigate the long-term safety, effectiveness, and outcomes of these procedures across diverse populations, as well as to explore advanced techniques and materials that may reduce complication rates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J. and D.C.; methodology, D.C.; software D.A., D.C. and A.J.; validation, Z.P. and E.J.; formal analysis, D.C., A.J., and Z.P.; investigation, D.C. and A.J.; resources, E.J., D.R., and Z.P.; data curation, Z.P. and D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C., D.A. and A.J.; writing—review and editing, A.J.; visualization, D.A.; supervision, E.J. and D.R.; project administration, D.R.; funding acquisition, D.R. and E.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No financial support was received, except for article-processing charge (APC) funding: Lithuanian University of Health Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application and approval from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Xiong, M.; Chen, C.; Sereda, Y.; Garibyan, L.; Avram, M.; Lee, K.C. Retrospective analysis of the MAUDE database on dermal filler complications from 2014–2020. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, 1158–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandawarkar, A.A.; Provenzano, D.; Rad, A.N.; Sherber, N.S. Learning curves: Historical trends of FDA-reported adverse events for dermal fillers. Cutis 2018, 102, E20–E23. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, A.E.; Ahluwalia, J.; Song, S.S.; Avram, M.M. Analysis of U.S. Food and Drug Administration Data on Soft-Tissue Filler Complications. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, 958–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjur, J.; Witherow, H. Long-term complications associated with permanent dermal fillers. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 51, 858–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, B.S.F.; De Almeida Balassiano, L.K.; Da Rocha, C.R.M.; De Sousa Padilha, C.B.; Torrado, C.M.; Da Silva, R.T.; Avelleira, J.C.R. Delayed-type Necrosis after Soft-tissue Augmentation with Hyaluronic Acid. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015, 8, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, B.L.; Yu, J.W.; Percec, I. Injectable Fillers. Adv. Cosmet. Surg. 2018, 1, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Fang, W.; Wang, F. Injectable fillers: Current status, physicochemical properties, function mechanism, and perspectives. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 23841–23858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tan, M.; Kontis, T.C. Midface Volumization with Injectable Fillers. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2015, 23, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, G.; Gout, U. Illustrated Guide to Injectable Fillers: Basics, Indications, Uses; Quintessence Publishing: London, UK, 2016; pp. 56–72, 118–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, A.C.; Robinson, J.K.; Rohrer, T.E. Surgery of the Skin: Procedural Dermatology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier/Saunders: London, UK, 2015; pp. 367–389. [Google Scholar]

- De Maio, M.; Rzany, B. Injectable Fillers in Aesthetic Medicine; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 75–128. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, K.; Kaufman-Janette, J.; Bank, D.; Biesman, B.; Dayan, S.; Kim, W.; Chawla, S.; Schumacher, A. Safe and effective chin augmentation with the hyaluronic acid injectable filler, VYC-20L. Dermatol. Surg. 2021, 47, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, K.R.; Jin, M.; Seok, J.; Yoo, K.H.; Kim, B.J. A randomized, participant- and evaluator-blinded, matched-pair prospective study to compare the safety and efficacy between polycaprolactone-based fillers in the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenen, S.A.; Bauland, C.G.; van der Lei, B.; Su, N.; van Engelen, M.D.; Anandbahadoer-Sitaldin, R.D.; Koeiman, W.; Jawidan, T.; Hamraz, Y.; de Lange, J. Head-to-head comparison of 4 hyaluronic acid dermal fillers for lip augmentation: A multicenter randomized, quadruple-blind, controlled clinical trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, 932–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.; Beer, K.; Cox, S.E.; Palm, M.M.; Kaufman-Janette, J.; Bassichis, B.; Biesman, B.; Joseph, J.; Almegård, B.; Nilsson, A.M.; et al. A randomized, controlled, evaluator-blinded, multi-center study of hyaluronic acid filler effectiveness and safety in lip fullness augmentation. Dermatol. Surg. 2021, 47, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, K.; Moradi, A.; Kaufman-Janette, J.; Ablon, G.; Donofrio, L.; Chapas, A.; Kazin, R.; Rivkin, A.; Rohrich, R.J.; Weiss, R.; et al. A randomized trial to assess effectiveness and safety of a hyaluronic acid filler for chin augmentation and correction of chin retrusion. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 150, 1240E–1248E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Lee, J.H. A single-center, randomized, double-blind clinical trial to compare the efficacy and safety of a new monophasic hyaluronic acid filler and biphasic filler in correcting nasolabial fold. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 2902–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.H.; Tsai, T.F. Safety and Effectiveness of Hyaluronic Acid Fillers with Lidocaine for Full-Face Treatment in Asian Patients. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2020, 19, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglefield, C.; Samuelson, U.E.; Landau, M.; DeVore, D. Bio-Dermal restoration with rapidly polymerizing collagen: A multicenter clinical study. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2018, 38, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkin, A.; Weinkle, S.H.; Hardas, B.; Weiss, R.A.; Glaser, D.A.; Biesman, B.S.; Schumacher, A.; Murphy, D.K. Safety and effectiveness of repeat treatment with VYC-15L for lip and perioral enhancement: Results from a prospective multicenter study. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2019, 39, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, G.J.; Ahn, G.R.; Park, S.J.; Hong, J.Y.; Kim, B.J. A randomized, patient/evaluator-blinded, split-face study to compare the efficacy and safety of polycaprolactone and polynucleotide fillers in the correction of crow’s feet: The latest biostimulatory dermal filler for crow’s feet. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogilvie, P.; Sattler, G.; Gaymans, F.; Belhaouari, L.; Weichman, B.M.; Snow, S.; Chawla, S.; Abrams, S.; Schumacher, A. Safe, effective chin and jaw restoration with VYC-25L hyaluronic acid injectable gel. Dermatol. Surg. 2019, 45, 1294–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman-Janette, J.; Joseph, J.H.; Dayan, S.H.; Smith, S.; Eaton, L.M.; Maffert, P.M. Patient comfort, safety, and effectiveness of Resilient hyaluronic acid fillers formulated with different local anesthetics. Dermatol. Surg. 2022, 48, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.L.; Swift, A.; Solish, N.; Fagien, S.; Glaser, D.A. OnabotulinumtoxinA and hyaluronic acid in facial wrinkles and folds: A prospective, open-label comparison. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2019, 39, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, B.; Mu, X.; Li, L. Lifting the midface using a hyaluronic acid filler with lidocaine: A randomized multi-center study in a Chinese population. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 6710–6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Sun, J.; Wu, S. A multi-center comparative efficacy and safety study of two different hyaluronic acid fillers for treatment of nasolabial folds in a Chinese population. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2019, 18, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzany, B.; Converset-Viethel, S.; Hartmann, M.; Larrouy, J.-C.; Ribé, N.; Sito, G.; Noize-Pin, C. Efficacy and safety of 3 new resilient hyaluronic acid fillers, crosslinked with decreased BDDE, for the treatment of dynamic wrinkles: Results of an 18-month, randomized controlled trial versus already available comparators. Dermatol. Surg. 2019, 45, 1304–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Gong, Y.; Diao, H.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, S.; Shi, Y. Efficacy and safety of two hyaluronic acid fillers with different injection depths for the correction of moderate-to-severe nasolabial folds: A 52-week, prospective, randomized, double-blinded study in a Chinese population. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartier, H.; Hedén, P.; Delmar, H.; Bergentz, P.; Skoglund, C.; Edwartz, C.; Norberg, M.; Kestemont, P. Repeated full-face aesthetic combination treatment with AbobotulinumtoxinA, hyaluronic acid filler, and skin- boosting hyaluronic acid after monotherapy with AbobotulinumtoxinA or hyaluronic acid filler. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohnert, K.; Dorizas, A.; Lorenc, P.; Sadick, N.S. Randomized, controlled, multicentered, double-blind investigation of injectable Poly-l-lactic acid for improving skin quality. Dermatol. Surg. 2019, 45, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, S.H.; Choi, M.E.; Lee, W.J.; Chang, S.E.; Lee, M.W.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, B.J.; Won, C.H. The efficacy and safety of BM-PHA for the correction of nasolabial folds: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, split-face clinical trial. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2021, 32, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabi, S.; Zoumalan, C.; Fagien, S.; Yoelin, S.; Sartor, M.; Chawla, S. A Prospective, multicenter, single-blind, randomized, controlled study of VYC-15L, a hyaluronic acid filler, in adults for correction of infraorbital hollowing. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2021, 41, NP1675–NP1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Baumann, L.; Moradi, A.; Shridharani, S.; Palm, M.; Teller, C.; Taylor, M.; Kontis, T.; Chapas, A.; Kaminer, M.; et al. A randomized, comparator-controlled study of HARC for cheek augmentation and correction of midface contour deficiencies. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2021, 20, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallini, M.; Papagni, M.; Ryder, T.J.; Patalano, M. Skin quality improvement with VYC-12, a new injectable hyaluronic acid: Objective results using Digital Analysis. Dermatol. Surg. 2019, 45, 1598–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogilvie, P.; Safa, M.; Chantrey, J.; Leys, C.; Cavallini, M.; Niforos, F.; Hopfinger, R.; Marx, A. Improvements in satisfaction with skin after treatment of facial fine lines with VYC-12 injectable gel: Patient-reported outcomes from a prospective study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fino, P.; Toscani, M.; Grippaudo, F.R.; Giordan, N.; Scuderi, N. Randomized double-blind controlled study on the safety and efficacy of a novel injectable cross-linked hyaluronic gel for the correction of moderate-to-severe nasolabial wrinkles. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2019, 43, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polacco, M.A.; Singleton, A.E.; Luu, T.; Maas, C.S. A randomized, blinded, prospective clinical study comparing small-particle versus cohesive polydensified matrix hyaluronic acid fillers for the treatment of perioral rhytids. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2021, 41, NP493–NP499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, S.; Frank, K.; Alfertshofer, M.; Cotofana, S. Clinical outcomes after lip injection procedures-Comparison of two hyaluronic acid gel fillers with different product properties. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiades, M.; Palm, M.D.; Kaufman-Janette, J.; Papel, I.; Cross, S.J.; Abrams, S.; Chawla, S. A randomized, multicenter, evaluator-blind study to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of VYC-12L treatment for skin quality improvements. Dermatol. Surg. 2023, 49, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.M.; Lee, W.S.; Yoon, J.; Paik, S.H.; Han, H.S.; Lee, W.J.; Chang, S.E.; Won, C.H.; Kim, B.J. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind comparison of two hyaluronic acid fillers in mid-face volume restoration in Asians: A 2-year extension study. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e14787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, H.; Shamban, A.; Schlessinger, J.; Kaufman-Janette, J.; Joseph, J.H.; Lupin, M.; Draelos, Z.; Carey, W.; Smith, S.; Eaton, L. Efficacy and safety of a new resilient hyaluronic acid filler in the correction of moderate-to- severe dynamic perioral rhytides: A 52-Week prospective, multicenter, controlled, randomized, evaluator-blinded study. Dermatol. Surg. 2022, 48, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braccini, F.; Fanian, F.; Garcia, P.; Delmar, H.; Loreto, F.; Benadiba, L.; Nadra, K.; Kestemont, P. Comparative clinical study for the efficacy and safety of two different hyaluronic acid-based fillers with Tri-Hyal versus Vycross technology: A long-term prospective randomized clinical trial. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palm, M.; Weinkle, S.; Cho, Y.; LaTowsky, B.; Prather, H. A randomized study on PLLA using higher dilution volume and immediate use following reconstitution. J. Drugs. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Peng, T.; Hong, W.-J.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Li, G.; Zheng, W.; Wang, H.; Luo, S.-K. A two-center, prospective, randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of and satisfaction with different methods of ART FILLER® UNIVERSAL injection for correcting moderate to severe nasolabial folds in Chinese individuals. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2023, 47, 1550–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Ren, R.; Bao, S.; Qian, W.; Ma, X.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Fang, R.; Sun, Q.; Tian, Y.; et al. Efficacy and safety of polycaprolactone in treating nasolabial folds: A prospective, multicenter, and randomized controlled trial. Facial Plast. Surg. 2023, 39, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.Y.; Han, H.S.; Yoo, K.H.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, Y.W. Reduced pain with injection of hyaluronic acid with pre-incorporated lidocaine for nasolabial fold correction: A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, active-controlled, split-face designed, clinical study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 3229–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Wu, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, Q. A randomized, multicenter study on a flexible hyaluronic acid filler in treatment of moderate-to-severe nasolabial folds in a Chinese population. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 4288–4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.M.; Zhang, X.; Dong, H.; Wen, C.; Hao, L. Correction of the tear trough deformity and concomitant infraorbital hollows with extracellular matrix/stromal vascular fraction gel. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, e118–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadera, S.; Shome, D.; Kumar, V.; Doshi, K.; Kapoor, R. Innovative approach for tear trough deformity correction using higher G prime fillers for safe, efficacious, and long-lasting results: A prospective interventional study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3147–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazidis, I.; Spyropoulou, G.-A.; Zambacos, G.; Tagka, A.; Rakhorst, H.A.; Gasteratos, K.; Berner, J.E.; Mandrekas, A. Adverse events associated with hyaluronic acid filler injection for non-surgical facial aesthetics: A systematic review of High Level of evidence studies. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2023, 48, 719–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrich, R.J.; Bartlett, E.L.; Dayan, E. Practical approach and safety of hyaluronic acid fillers. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbea, E.; Kidwai, S.; Rosenberg, J. Nonsurgical tear trough volumization: A systematic review of patient satisfaction. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2021, 41, NP1053–NP1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galadari, H.; Weinkle, S.H. Injection techniques for midface volumization using soft tissue hyaluronic acid fillers designed for dynamic facial movement. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannino, M.; Lupi, E.; Bernardi, S.; Becelli, R.; Giovannetti, F. Vascular complications with necrotic lesions following filler injections: Literature systematic review. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 125, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortada, H.; Seraj, H.; Barasain, O.; Bamakhrama, B.; Alhindi, N.I.; Arab, K. Ocular complications post-cosmetic periocular hyaluronic acid injections: A systematic review. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2022, 46, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).