Abstract

(1) Background and Objectives: The COVID-19 pandemic influenced the management of patients with immune-mediated rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (imRMDs) in various ways. The goal of our systematic review was to determine the influence of the first period of the COVID-19 pandemic (February 2020 to July 2020) on the management of imRMDs regarding the availability of drugs, adherence to therapy and therapy changes and on healthcare delivery. (2) Materials and Methods: We conducted a systematic literature search of PubMed, Cochrane and Embase databases (carried out 20–26 October 2021), including studies with adult patients, on the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the management of imRMDs. There were no restrictions regarding to study design except for systematic reviews and case reports that were excluded as well as articles on the disease outcomes in case of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Two reviewers screened the studies for inclusion, and in case of disagreement, a consensus was reached after discussion. (3) Results: A total of 5969 potentially relevant studies were found, and after title, abstract and full-text screening, 34 studies were included with data from 182,746 patients and 2018 rheumatologists. The non-availability of drugs (the impossibility or increased difficulty to obtain a drug), e.g., hydroxychloroquine and tocilizumab, was frequent (in 16–69% of patients). Further, medication non-adherence was reported among patients with different imRMDs and between different drugs in 4–46% of patients. Changes to preexisting medication were reported in up to 33% of patients (e.g., reducing the dose of steroids or the cessation of biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs). Physical in-office consultations and laboratory testing decreased, and therefore, newly implemented remote consultations (particularly telemedicine) increased greatly, with an increase of up to 80%. (4) Conclusions: The COVID-19 pandemic influenced the management of imRMDs, especially at the beginning. The influences were wide-ranging, affecting the availability of pharmacies, adherence to medication or medication changes, avoidance of doctor visits and laboratory testing. Remote and telehealth consultations were newly implemented. These new forms of healthcare delivery should be spread and implemented worldwide to routine clinical practice to be ready for future pandemics. Every healthcare service provider treating patients with imRMDs should check with his IT provider how these new forms of visits can be used and how they are offered in daily clinical practice. Therefore, this is not only a digitalization topic but also an organization theme for hospitals or outpatient clinics.

1. Introduction

In 2019, the novel coronavirus “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Corona Virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)” was identified in China [1]. Coronaviruses have led to several critical disease outbreaks in the past. Important to mention are the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in China in 2002 and of middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS) on the Arabian Peninsula in 2012 and in Korea in 2015. While these former disease outbreaks were geographically localized, SARS-CoV-2 spread rapidly over countries, causing a worldwide pandemic [2]. The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 was subsequently named coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) [3,4]. At the beginning of the pandemic, the focus was primarily on an infection of the lungs with pneumonia and pneumonitis occurring, as well as the associated problems in severe cases such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). By now, COVID-19 is known to be a multisystem infectious disease that affects different organ systems [5]. The course of COVID-19 ranges from mild to severe and critical cases (depending on risk factors) often requiring intensive care. Risk factors for a severe disease course are cardiovascular risk factors, chronic lung diseases, male sex, age over 65 years, obesity, high-dose corticosteroid use, and immunodeficiency or immunosuppressive medication [6]. Patients with immune-mediated rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (imRMDs) including inflammatory arthropathies (rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies), connective tissue diseases or vasculitis are at a higher risk of infections especially due to the use of immunosuppressive medication [7].

COVID-19 and the following pandemic have therefore raised concerns amongst rheumatologists, especially regarding immunocompromised patients. Data from 2021 show that the risk for infection with SARS-CoV-2 is not increased [7] or only slightly [8] elevated in patients with imRMDs compared to the general population, but, if infected, the risks for hospitalization or for a severe disease course and death are increased by a factor of 1.58 to 2.92 [9]. Regarding medication, most conventional synthetic (csDMARD), biological (bDMARD) and targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (tsDMARDs) do not seem to increase the risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 or the risk of poor outcomes of COVID-19, the exceptions being glucocorticoids > 10 mg/day, rituximab, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and potentially Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKis) [9].

The disease course of patients with imRMDs and SARS-CoV-2 infection has been studied widely, but systematic reviews describing the influence of the pandemic on the treatment of imRMDs are lacking.

The aim of this systematic review is to describe the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the management of imRMDs during the first wave from February 2020 to July 2020 regarding availability of drugs, adherence and changes in medications, on the access to rheumatological care and medications and on the use of other healthcare delivery forms.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [10]. A comprehensive search was carried out in PubMed, Cochrane and Embase databases regarding publications from 1 December 2019 to 31 October 2021. We used specific MeSH headings and additional keywords to identify studies (see search strategy in Supplementary File S1).

We selected articles in English or German including adult patients with imRMDs that evaluated the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general management of imRMDs (influence on adherence or changes in medications), on the access to rheumatologically care and medications, and on the use of other healthcare delivery forms. There were no restrictions regarding study design except for systematic reviews and case reports that were excluded as well as articles on the disease outcomes in case of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Studies found were screened independently by two reviewers (MS, SBa) for inclusion. In the first phase, the studies were screened for title and abstract, followed by full-text screening and data extraction. In case of disagreements, a consensus was reached after discussion between the two raters. Quality rating was performed according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence [11]. Covidence systematic review software (version of 2021, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) [12] was used as the literature management program and Zotero (version 6, Corporation for Digital Scholarship, Fairfax, VA, USA) as reference management software [13].

Because no randomized controlled trials were published and data were very heterogeneous, no meta-analysis was performed. Out of the included studies, two clusters of “influences of COVID-19 pandemic” were formed and analyzed further regarding: (i) the influence on the medical management of imRMDs; (ii) influences on healthcare delivery regarding imRMDs.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

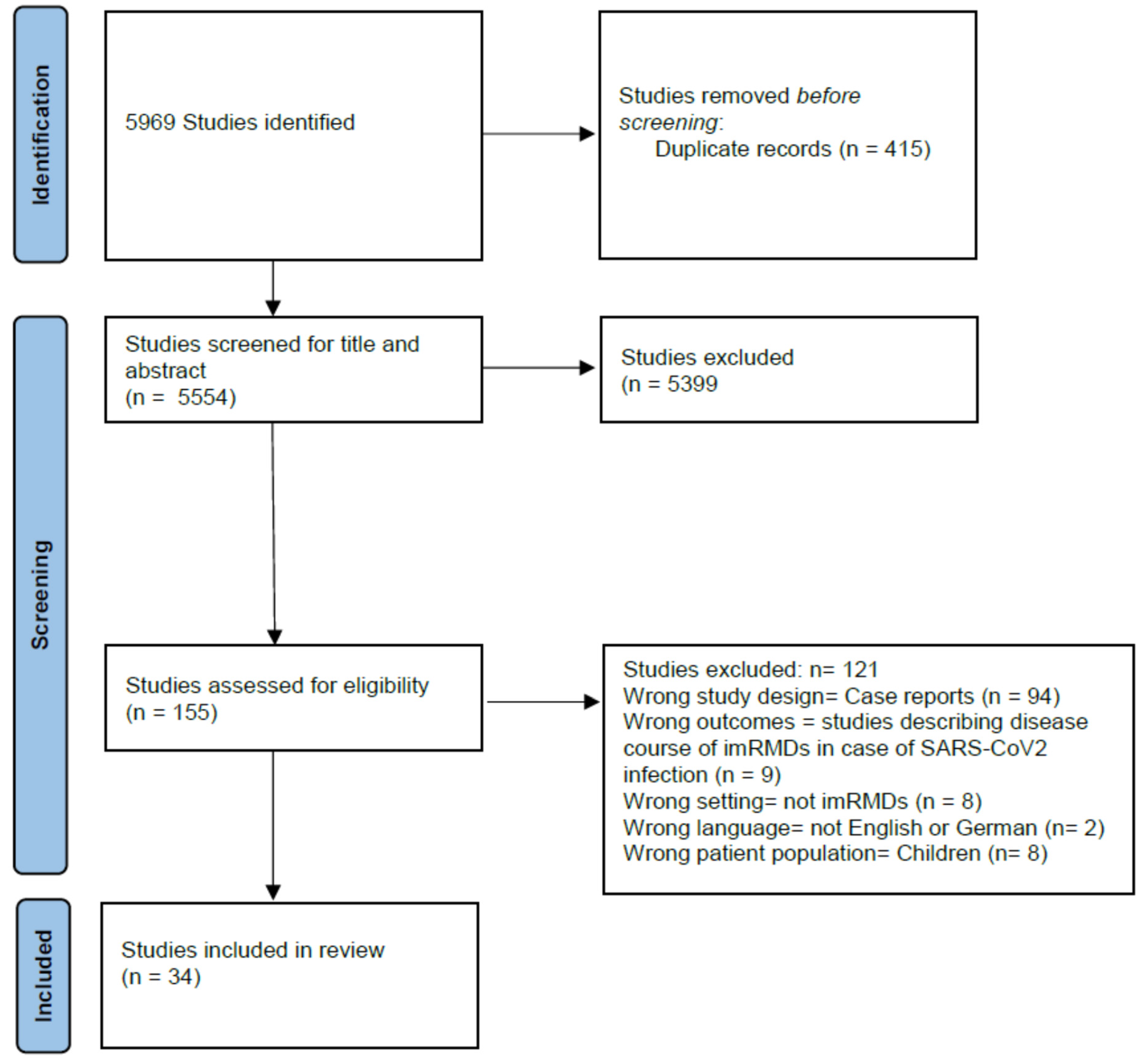

The search strategy identified 5969 potentially relevant studies. Based on title and abstract and after removal of duplicates, 155 studies were assessed in full-text screening. A final total of 34 studies with data from 182,746 patients and from 2018 rheumatologists were included in the systematic review. Figure 1 shows the study flow according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [10].

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

3.2. Study Characteristics and Levels of Evidence

The majority of included studies were surveys or questionnaires [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], which are evidence grade IV according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence [11]. One was a cohort study, graded level III [48].

3.3. Studies Origin

Seventeen studies were from Europe [15,16,18,19,21,22,24,28,29,30,31,37,39,41,42,46,47], three from Africa [14,17,34], ten from North America [23,25,26,27,33,35,36,38,45,48,49] and five from Asia [20,32,40,43,44]. Details of the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48].

3.4. Outcomes

3.4.1. Influence on the Medical Management of imRMDs

- (a)

- Non-availability of drugs

The non-availability of rheumatic medication was a prevalent issue, important examples being hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and tocilizumab. Shortages or difficulties in the availability of HCQ was an issue in 16–69% of patients [14,15,17,20,23,30,47], with the highest level reported from India [20]. Shortages of tocilizumab was reported in 14% of patients [45,47].

- (b)

- Non-adherence to medication

Non-adherence to prescribed drugs was another issue. Non-adherence was very heterogeneously defined in the different studies as changing medication, the adaptation of dose or intervals without professional health advice or stopping medication or the irregular intake of medication without professional health advice. The overall non-adherence rate among all included studies was 4–46% of patients [16,26,29,30,31,32,43]. High rates of non-adherence were reported by four studies [20,21,24,33], with the highest level (46% of patients) reported from India [20].

A Swiss study [16] comparing the medication adherence of patients with different imRMDs before and during the pandemic found only slight adherence reductions. A significant increase in non-adherence was only seen in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) (13% medication non-adherence in pre-COVID-19 period versus 20% during the first wave). The lowest level of medication non-adherence was reported from Denmark [21]. In this study, compliance with medication was compared between the start of the first lockdown to three months later, when society was gradually reopened. Low levels of non-adherence were reported (4–6% at the start of the lockdown versus 2–4% three months later). Further, there was a direct correlation of the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infections in the general population and medication non-adherence: the higher the incidence of COVID-19, the lower the medication adherence [24].

- (c)

- Drugs changed or stopped

The drugs mostly changed or stopped were bDMARDs and JAKi [28,32]. Low-dose prednisolone and csDMARDs were the least likely medications to be stopped. Longer disease durations of the underlying rheumatic disease and higher disease activity were significantly associated with medication discontinuation [19]. Disease flares were described in high proportions of the patients (63–74%) who had stopped their DMARDs [15,18].

Many studies reported reasons for changes in medication-taking. The following factors were significantly associated with changes in at least one medication due to patients’ fear of COVID-19 [21]: male sex (odds ratio (OR) 1.51, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.21–1.89), age > 80 years compared to <39 years (OR 0.11, 95% CI 0.006–0.52), lower education (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.45–0.69), being employed (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.16–1.99) and the use of bDMARDs (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.02–3.81).

Regarding different rheumatologic diseases, a study from India [43] found that 43% of patients with inflammatory arthritis, 31% with systemic lupus erythematodes (SLE) and 13% with inflammatory myositis and scleroderma (p < 0.05) stopped their treatment. Further detailed information regarding non-adherence to or the non-availability of medication is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Rates of non-adherence and of difficulties obtaining medication regarding different immune-mediated RMDs.

- (d)

- Influence on the treating rheumatologist

Lastly, there was also an influence of the pandemic on the treating physician regarding medication. Rheumatologists reduced the dose of steroids in 23–36% of patients [14,47], and in 17% of patients, steroids were stopped completely [14]. In contrast, csDMARDs were stopped only rarely (in 2% of patients) [14], whereas bDMARDs were stopped more frequently (in 33% of patients) [15]. In a few cases, drug application intervals of bDMARDs were extended [28]. Moreover rheumatologists were hesitant to start a bDMARD in 75% [47] or a tsDMARD in 14% [14] of cases.

3.4.2. Influences on Healthcare Delivery

- (a)

- Avoidance of in-person visits

George et al. [27] and Banerjee et al. [36] reported the avoidance of laboratory testing in 42% and 47% of patients, respectively. Patients with imRMDs were significantly less likely to avoid in-person visits (OR 0.79 (95% CI 0.70–0.89)) or laboratory tests compared to patients with non-autoimmune RMDs (35% versus 39%, OR 0.84 (95% CI 0.73–0.96)) [26,48]. Other factors associated with the avoidance of in-person visits and laboratory testing were older age, low socioeconomic status, living in urban areas or in countries with higher COVID-19 activity and regarding medication receiving a bDMARD or JAKi [48].

From the patients’ perspective, high levels of unwillingness to healthcare visits were reported (21–86%) [14,15,27,30,36]. The highest levels with 86% of patients unwilling to attend the hospital were reported from Turkey [30]. An inability to communicate with or to see the rheumatologist was also frequently reported by 7% [21] to 39% [20] of patients [17,20,21,25,30].

- (b)

- Alternative types of visits

Singh et al. [45] reported an increase in alternative types of visits to the rheumatologist related to COVID-19 compared to the pre-COVID-19 era, such as telephone visits (plus 53%), video-based Veterans Affairs Video Connect (VVC) visits (plus 44%) and clinical video tele-health (CVT) visits with a facilitator (plus 29%). Bos et al. [46] reported telephone visits to be the most commonly used form of remote consultation, with 80% of rheumatologists using exclusively telephone consultations. In-person visits were conducted only in special circumstances, such as for joint aspiration [46].

4. Discussion

This systematic review showed that COVID-19 influenced healthcare behavior in patients with imRMDs, as well as in rheumatologists and other doctors during the first pandemic wave from February to July 2020. In many cases, patients or doctors discontinued established medication. Further, the pandemic resulted in a collapse of supply chains, causing the non-availability of medication, especially in the case of HCQ and tocilizumab. Healthcare appointments took place less frequently than usual, and telehealth emerged as a solution, with remote consultations with physicians or with newly established telerehabilitation services.

Medication non-adherence was a common problem among patients. A possible explanation could be the low availability of remote consultations at the beginning of the pandemic, resulting in feelings of insecurity with patients stopping their medication as a self-management strategy. The classes of medication that were discontinued most frequently were bDMARDs and JAKi [26,30], possibly because these immunosuppressive medications are considered the most dangerous regarding infections.

Between different imRMDs, relevant differences in non-adherence to medication have been reported. Low numbers of non-adherence were reported in patients with vasculitis [37,38]. Patients with vasculitis are usually aware of the disease course with serious relapses in the absence of maintenance therapy, which results in an adherence to treatment [38]. Another factor increasing medical compliance is that parenteral treatments are often only possible in the hospital setting and are therefore not postponed by patients.

The sudden discontinuation of anti-rheumatic therapy is a relevant issue because it can lead to disease flares. A large proportion of patients with different imRMDs reported a flare after modifying their treatment [15,18]. This supports the recommendation of not stopping treatment during the pandemic in situations other than suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection because resulting disease flares and higher requirements for glucocorticoids could increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection [36].

The pandemic, and mostly the fear of infection with SARS-CoV-2, had a severe influence on the medication behavior of rheumatologists. A large proportion of rheumatologists reduced the dose or frequency of steroids [14,47,49], many changed DMARDs [14,22] or stopped them [14,15] and there was hesitancy to start new DMARDs [47,49].

N. Rebić et al. conducted a systematic review about the adherence to medication in patients with imRMDs [49]. They described non-adherence rates of 6.5–34.2% and discontinuation rates of 2–31.4% which are similar rates compared to the overall non-adherence rate of 4–46% in our systematic review. They found slightly higher numbers of physicians who reduced the dose of steroids (23–56% vs. 23–36% in our review), and they also reported of a reluctance to start bDMARDs or tsDMARDs.

Different non-compliance rates to medical visits were reported between the different studies [22,30]. Patients with autoimmune RMDs were significantly less likely to avoid in-person visits and laboratory tests compared to patients with non-autoimmune rheumatic diseases [26,48]. These results may be explained with the fact that patients with imRMDs needed close monitoring because of their disease as well as their immunosuppressive treatment and the fear of an infection with SARS-CoV-2 was a more dominant factor determining behavior. Interestingly, a study from North America [48] reported a normalization of the rates of follow-up visits a few months after the start of the pandemic, suggesting a rapid adaptation of patients and doctors to the pandemic circumstances.

The COVID-19 pandemic posed many challenges, but it also opened new opportunities for the development of healthcare systems. Because of the environmental risk factors for acquiring a SARS-CoV-2-infection before vaccines existed, practical steps to reduce the infection risk were introduced, including social distancing, hand hygiene and use of face masks [9]. As a consequence of social distancing, patient consultations were performed remotely whenever possible, leading to an increase in telehealth care. Prior to 2019, telehealth care was very rare or non-existent, but its use grew rapidly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, there were huge differences between different countries in the implementation of telehealth. Data from the USA and Australia showed an increase in telehealth, whereas data from India reported that only a small proportion of patients were aware that telehealth existed, and even fewer used it. It is likely that many patients with imRMDs, especially those from non-urban parts of emerging countries, had no access to telehealth care during the COVID-19 pandemic. A major goal of telehealth was to try to avoid disruption of healthcare and to prevent patients from stopping their medication. In addition, telephone and video-based consultations were preferred in “stable patients” with known disease courses and without the need for changing immunosuppressive medication [45].

Based on our personal experience, we believe that telehealth was a valuable tool to avoid disruption in healthcare and to prevent medication non-adherence in these special circumstances. However, since the pandemic period is over, the rate of telehealth consultations went back, and the advantages of telehealth and remote consultations are only seen in patients who have mobility difficulties to reach the treating physician’s office. In these situations, telehealth and remote consultations are still a valuable instrument to increase or hold adherence to medications.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. Although most studies were of low evidence grade (III or IV), data from 182,746 patients and 2018 interviewed rheumatologists were included. Together with the fact that studies from four different continents and different countries were included, these large numbers paint a global picture of the influence of the pandemic on imRMDs. The influence covers a broad spectrum of issues occurring during the COVID-19 pandemic, including compliance with medication, the shortage of certain medications and problems with the delivery of healthcare. In addition, new aspects are described, such as telemedicine and telerehabilitation services, which were set up as substitutes for former in-person routine care. The study also has limitations. First, regarding the heterogeneity of the reported outcomes and the study designs, it was not possible to carry out a meta-analysis and to evaluate the results statistically using odds ratios. Inhomogeneous reporting and differences in research methodology between the studies made comparisons difficult, and a generalization of the results may not be suitable. Furthermore, definitions of non-adherence with medication varied between studies. Therefore, it was demanding to extract and compare the different results rationally. Most of the included studies were surveys, which leads to some typical limitations regarding the study design. Surveys may lead to inclusion biases, as patients who are more interested or worried about COVID-19 are generally more willing to participate. The responses are self-reported and cannot be verified. Survivorship bias is also probable as very sick or deceased patients cannot participate. Further, patients with a relatively higher socioeconomic status have a greater online presence and affinity to online surveys and are therefore probably overrepresented. As many of the results were published only as case reports and congress abstracts, those results were not included in the present study. Important information may therefore have been missed. Finally, this review shows only results regarding the influence on the treatment of imRMDs of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic lasting February 2020 to July 2020.

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic influenced the management of patients with imRMDs, especially during the first wave from February 2020 to July 2020. The influence of the pandemic was diverse regarding adherence to medication, shortage of some medications, adherence to doctor visits or laboratory testing and governmental interventions. To preserve adherence to healthcare, the COVID-19 pandemic was a starting point for new healthcare systems. Remote and telehealth consultations were implemented. These new forms of healthcare delivery should be spread and implemented worldwide to routine clinical practice to be ready for future pandemics. Every healthcare service provider treating patients with imRMDs should check with his IT provider how these new forms of visits can be used and how they are offered in daily clinical practice. Therefore, this is not only a digitalization topic but also an organization theme for hospitals or outpatient clinics.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/medicina60040596/s1, Supplementary File S1: Search Strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis and investigation, M.S. and S.B.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and S.B.; supervision, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Kliniken Valens.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

For original data reported in this systematic review, we refer to the original publications.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| axSpA | axial spondyloarthritis |

| csDMARDs, bDMARDs, tsDMARDs | conventional synthetic, biological and targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs |

| CVT | clinical video telehealth |

| HCQ | hydroxychloroquine |

| imRMDs | immune-mediated Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases |

| JAKi | Janus kinase inhibitors |

| MMF | mycophenolate mofetil |

| NSAIDs | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PsoA | psoriasis arthritis |

| RA | rheumatoid arthritis |

| SLE | systemic lupus erythematodes |

| VVC | video-based Veterans Affairs Video Connect |

References

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.E.; Li, Z.; Chiew, C.J.; Yong, S.E.; Toh, M.P.; Lee, V.J. Presymptomatic Transmission of SARS-CoV-2—Singapore, January 23–March 16, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleem, A.; Samad, A.B.A.; Slenker, A.K. Emerging Variants of SARS-CoV-2 and Novel Therapeutics Against Coronavirus (COVID-19). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570580/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- World Health Organisation. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; Sehgal, K.; Nair, N.; Mahajan, S.; Sehrawat, T.S.; Bikdeli, B.; Ahluwalia, N.; Ausiello, J.C.; Wan, E.Y.; et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, R.T.; Lynch, J.B.; del Rio, C. Mild or Moderate COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landewé, R.B.M.; Kroon, F.P.B.; Alunno, A.; Najm, A.; Bijlsma, J.W.; Burmester, G.R.R.; Caporali, R.; Combe, B.; Conway, R.; Curtis, J.R.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management and vaccination of people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in the context of SARS-CoV-2: The November 2021 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 1628–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grainger, R.; Kim, A.H.J.; Conway, R.; Yazdany, J.; Robinson, P.C. COVID-19 in people with rheumatic diseases: Risks, outcomes, treatment considerations. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’silva, K.M.; Serling-Boyd, N.; Wallwork, R.; Hsu, T.; Fu, X.; Gravallese, E.M.; Choi, H.K.; Sparks, J.A.; Wallace, Z.S. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and rheumatic disease: A comparative cohort study from a US ‘hot spot’. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 1156–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence (March 2009)—Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), University of Oxford. Available online: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009 (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Covidence. Covidence—Better Systematic Review Management. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 24 December 2023).

- Zotero|Your Personal Research Assistant. Available online: https://www.zotero.org (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Akintayo, R.O.; Akpabio, A.A.; Kalla, A.A.; Dey, D.; Migowa, A.N.; Olaosebikan, H.; Bahiri, R.; El Miedany, Y.; Hadef, D.; Hamdi, W.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 on rheumatology practice across Africa. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batıbay, S.; Koçak Ulucaköy, R.; Özdemir, B.; Günendi, Z.; Göğüş, F.N. Clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic diseases and the effects of the pandemic on rheumatology outpatient care: A single-centre experience from Turkey. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurea, A.; Papagiannoulis, E.; Bürki, K.; von Loga, I.; Micheroli, R.; Möller, B.; Rubbert-Roth, A.; Andor, M.; Bräm, R.; Müller, A.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the disease course of patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases: Results from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management cohort. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziadé, N.; el Kibbi, L.; Hmamouchi, I.; Abdulateef, N.; Halabi, H.; Hamdi, W.; Abutiban, F.; el Rakawi, M.; Eissa, M.; Masri, B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with chronic rheumatic diseases: A study in 15 Arab countries. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 23, 1550–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, F.; Bahier, L.; Tarancón, L.C.; Leboime, A.; Vidal, F.; Bessalah, L.; Breban, M.; D’agostino, M.-A. COVID-19 in French patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases: Clinical features, risk factors and treatment adherence. Jt. Bone Spine 2021, 88, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coskun, B.N.; Yagiz, B.; Pehlivan, Y.; Dalkilic, E. Attitudes of patients with a rheumatic disease on drug use in the COVID-19 pandemic. Adv Rheumatol. 2021, 61, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, J.; Ganapati, A.; Padiyar, S.; Nair, A.; Gowri, M.; Kachroo, U.; Nair, A.; Priya, S. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic and Resultant Lockdown in India on Patients with Chronic Rheumatic Diseases: An Online Survey. Indian J. Rheumatol. 2021, 16, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glintborg, B.; Jensen, D.V.; Engel, S.; Terslev, L.; Pfeiffer Jensen, M.; Hendricks, O.; Østergaard, M.; Rasmussen, S.H.; Adelsten, T.; Colic, A.; et al. Self-protection strategies and health behaviour in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results and predictors in more than 12 000 patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases followed in the Danish DANBIO registry. RMD Open 2021, 7, e001505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glintborg, B.; Jensen, D.V.; Terslev, L.; Pfeiffer Jensen, M.; Hendricks, O.; Østergaard, M.; Engel, S.; Rasmussen, S.H.; Adelsten, T.; Colic, A.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on treat-to-target strategies and physical consultations in >7000 patients with inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology 2021, 60, SI3–SI12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, C.A.; Duculan, R.; Jannat-Khah, D.; Barbhaiya, M.; Bass, A.R.; Mandl, L.A.; Mehta, B. Modifications in Systemic Rheumatic Disease Medications: Patients’ Perspectives during the Height of the COVID-19 Pandemic in New York City. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasseli, R.; Müller-Ladner, U.; Keil, F.; Broll, M.; Dormann, A.; Fräbel, C.; Hermann, W.; Heinmüller, C.-J.; Hoyer, B.F.; Löffler, F.; et al. The influence of the SARS-CoV-2 lockdown on patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases on their adherence to immunomodulatory medication: A cross sectional study over 3 months in Germany. Rheumatology 2021, 60, SI51–S158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, J.S.; Kennedy, K.; Simard, J.F.; Liew, J.W.; Sparks, J.A.; Moni, T.T.; Harrison, C.; Larché, M.J.; Levine, M.; Sattui, S.E.; et al. Immediate effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient health, health-care use, and behaviours: Results from an international survey of people with rheumatic diseases. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021, 3, e707–e714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.D.; Baker, J.F.; Banerjee, S.; Busch, H.; Curtis, D.; Danila, M.I.; Gavigan, K.; Kirby, D.; Merkel, P.A.; Munoz, G.; et al. Social Distancing, Health Care Disruptions, Telemedicine Use, and Treatment Interruption during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Patients with or without Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2021, 3, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.D.; Venkatachalam, S.; Banerjee, S.; Baker, J.F.; Merkel, P.A.; Gavigan, K.; Curtis, D.; Danila, M.I.; Curtis, J.R.; Nowell, W.B. Concerns, Healthcare Use, and Treatment Interruptions in Patients with Common Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Rheumatol. 2021, 48, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyoncu, U.; PehliVan, Y.; Akar, S.; KaşiFoğlu, T.; KiMyon, G.; Karadağ, Ö.; Dalkılıç, H.E.; Ertenli, A.İ.; Kılıç, L.; Ersözlü, D.; et al. Preferences of inflammatory arthritis patients for biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in the first 100 days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 1615–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, K.; Quinn, S.; Turk, M.; O’rourke, A.; Molloy, E.; O’neill, L.; Mongey, A.B.; Fearon, U.; Veale, D.J. COVID-19 and rheumatic musculoskeletal disease patients: Infection rates, attitudes and medication adherence in an Irish population. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyahi, E.; Poyraz, B.Ç.; Sut, N.; Akdogan, S.; Hamuryudan, V. The psychological state and changes in the routine of the patients with rheumatic diseases during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Turkey: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Rheumatol. Int. 2020, 40, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, M.; Gordon, C.; Harwood, R.; Lever, E.; Wincup, C.; Bosley, M.; Brimicombe, J.; Pilling, M.; Sutton, S.; Holloway, L.; et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the medical care and health-care behaviour of patients with lupus and other systemic autoimmune diseases: A mixed methods longitudinal study. Rheumatol. Adv. Pract. 2021, 5, rkaa072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassen, L.M.; Almaghlouth, I.A.; Hassen, I.M.; Daghestani, M.H.; Almohisen, A.A.; Alqurtas, E.M.; Alkhalaf, A.; Bedaiwi, M.K.; Omair, M.A.; Almogairen, S.M.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on rheumatic patients’ perceptions and behaviors: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 23, 1541–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaracha-Basáñez, G.A.; Contreras-Yáñez, I.; Hernández-Molina, G.; González-Marín, A.; Pacheco-Santiago, L.D.; Valverde-Hernández, S.S.; Peláez-Ballestas, I.; Pascual-Ramos, V. Clinical and bioethical implications of health care interruption during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in outpatients with rheumatic diseases. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abualfadl, E.; Ismail, F.; Shereef, R.R.E.; Hassan, E.; Tharwat, S.; Mohamed, E.F.; Abda, E.A.; Radwan, A.R.; Fawzy, R.M.; Moshrif, A.H.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on rheumatoid arthritis from a Multi-Centre patient-reported questionnaire survey: Influence of gender, rural–urban gap and north–south gradient. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, K.; Pedro, S.; Wipfler, K.; Agarwal, E.; Katz, P. Changes in Disease-Modifying Anti-rheumatic Drug Treatment for Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis in the US during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Three-Month Observational Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; George, M.; Young, K.; Venkatachalam, S.; Gordon, J.; Bs, C.B.; Curtis, D.; Ferrada, M.; Gavigan, K.; Grayson, P.C.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Patients Living with Vasculitis. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2021, 3, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ince, B.; Bektaş, M.; Koca, N.; Ağargün, B.F.; Zarali, S.; Güzey, D.Y.; Ince, A.; Sevdi, M.S.; Yalçinkaya, Y.; Artim-Esen, B.; et al. A single center survey study of systemic vasculitis and COVID-19 during the first months of pandemic. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 2243–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, S.; Morris, A.; Ravi, S.; Floyd, L.; Gapud, E.; Antichos, B.; Dhaygude, A.; Seo, P.; Geetha, D. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with ANCA associated vasculitis. J. Nephrol. 2021, 34, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornet, A.; Andersen, J.; Tani, C.; Mosca, M. Hydroxychloroquine availability during COVID-19 crisis and its effect on patient anxiety. Lupus Sci. Med. 2021, 8, e000496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathi, M.; Singh, P.; Bi, H.P.; Shivanna, A.; Kavadichanda, C.; Tripathy, S.R.; Parthasarathy, J.; Tota, S.; Maurya, S.; Vijayalekshmi, V.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Observations from an Indian inception cohort. Lupus 2021, 30, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, L.; Kharbanda, R.; Agarwal, V.; Misra, D.P.; Agarwal, V. Patient Perspectives on the Effect of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic on Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: An International Patient Survey. JCR J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 27, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, L.; Lilleker, J.B.; Agarwal, V.; Chinoy, H.; Aggarwal, R. COVID-19 and myositis—Unique challenges for patients. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 907–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavadichanda, C.; Shah, S.; Daber, A.; Bairwa, D.; Mathew, A.; Dunga, S.; Das, A.C.; Gopal, A.; Ravi, K.; Kar, S.S.; et al. Tele-rheumatology for overcoming socioeconomic barriers to healthcare in resource constrained settings: Lessons from COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 3369–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavadichanda, C.; Shobha, V.; Ghosh, P.; Wakhlu, A.; Bairwa, D.; Mohanan, M.; Janardana, R.; Sircar, G.; Sahoo, R.R.; Joseph, S.; et al. Clinical and psychosocioeconomic impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients of the Indian Progressive Systemic Sclerosis Registry (IPSSR). Rheumatol. Adv. Pract. 2021, 5, rkab027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.A.; Richards, J.S.; Chang, E.; Joseph, A.; Ng, B. Management of Rheumatic Diseases during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Veterans Affairs Survey of Rheumatologists. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, W.H.; van Tubergen, A.; Vonkeman, H.E. Telemedicine for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic; a positive experience in The Netherlands. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejaco, C.; Alunno, A.; Bijlsma, J.W.; Boonen, A.; Combe, B.; Finckh, A.; Machado, P.M.; Padjen, I.; Sivera, F.; Stamm, T.A.; et al. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on decisions for the management of people with inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: A survey among EULAR countries. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, M.D.; Danila, M.I.; Watrous, D.; Reddy, S.; Alper, J.; Xie, F.; Nowell, W.B.; Kallich, J.; Clinton, C.; Saag, K.G.; et al. Disruptions in Rheumatology Care and the Rise of Telehealth in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Community Practice–Based Network. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebić, N.; Park, J.Y.; Garg, R.; Ellis, U.; Kelly, A.; Davidson, E.; De Vera, M.A. A rapid review of medication taking (‘adherence’) among patients with rheumatic diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 74, 1961–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).