Abstract

Background and Objectives: The present study aimed to elucidate the distribution and the prognostic implications of tumor–stroma ratio (TSR) in various malignant tumors through a meta-analysis. Materials and Methods: This meta-analysis included 51 eligible studies with information for overall survival (OS) or disease-free survival (DFS), according to TSR. In addition, subgroup analysis was performed based on criteria for high TSR. Results: The estimated rate of high TSR was 0.605 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.565–0.644) in overall malignant tumors. The rates of high TSR ranged from 0.276 to 0.865. The highest rate of high TSR was found in endometrial cancer (0.865, 95% CI 0.827–0.895). The estimated high TSR rates of colorectal, esophageal, and stomach cancers were 0.622, 0.529, and 0.448, respectively. In overall cases, patients with high TSR had better OS and DFS than those with low TSR (hazard ratio (HR) 0.631, 95% CI 0.542–0.734, and HR 0.564, 95% CI 0.0.476–0.669, respectively). Significant correlations with OS were found in the breast, cervical, colorectal, esophagus, head and neck, ovary, stomach, and urinary tract cancers. In addition, there were significant correlations of DFS in breast, cervical, colorectal, esophageal, larynx, lung, and stomach cancers. In endometrial cancers, high TSR was significantly correlated with worse OS and DFS. Conclusions: The rate of high TSR was different in various malignant tumors. TSR can be useful for predicting prognosis through a routine microscopic examination of malignant tumors.

1. Introduction

Pathological examination is performed through the interpretation of glass slides with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. In the pathological assessment of malignant tumors, the primary tumor, regional lymph node, and distant metastasis are evaluated according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual [1]. Tumor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and resection margin involvement are evaluated in daily practice. Useful parameters for predicting the patient’s prognosis should have easy identification, high reproducibility, and less discrepancy between investigators. An epithelial tumor is composed of the tumor and surrounding stroma. Interaction between tumor cells and intra- and peritumoral stroma is important in tumor progression [2]. Evaluating these interactions can be useful for understanding tumor behavior. Stroma includes various components, such as immune cells, fibroblasts, and the extracellular matrix [3,4,5,6]. The tumor–stroma ratio (TSR), defined as the proportion of tumor area in the overall tumor, has been studied as a histologic assessment [2,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. TSR is assessed by microscopic observation with H&E staining and is a method that can be sufficiently evaluated in routine pathology laboratories. However, the impact of the proportion of stroma is not clear in terms of whether it accelerates or suppresses tumor progression. Recently, the prognostic implications of TSR have been exhibited for various malignant tumors [2,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. In colorectal cancers, low stroma was associated with less frequent vascular and perineural invasion and distant metastasis [45]. HIF-1α was found to be highly expressed in stroma-high tumors, with correspondingly high microvessel density in colorectal cancers. There is no conclusive information on the prognostic impacts of TSR in various malignant tumors. TSR is divided into high TSR (stroma-low) and low TSR (stroma-high) by evaluation criteria. In previous studies, the evaluation criteria of TSR affected high TSR rates [2,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. If the evaluation criteria are different, the prognostic implications of TSR can differ. The evaluations of TSR have been shown to have good interobserver agreement [58] but may be more influenced by criteria. In addition, there are carcinomas that require more careful evaluation, such as lung cancer, where the amount of stroma can be inherently different between histological subtypes. It is difficult to evaluate the implications of TSR from individual studies. It is important to determine the direction of further research and analysis from a comprehensive analysis. A meta-analysis study using previous literature can be useful in obtaining comprehensive information.

We investigated high TSR rates of various malignant tumors according to malignant tumor evaluation criteria. The correlations between TSR and survival were elucidated through the subgroup analysis based on malignant tumors. The high TSR rates and prognostic impact of TSR according to evaluation criteria were analyzed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Published Study Search and Selection Criteria

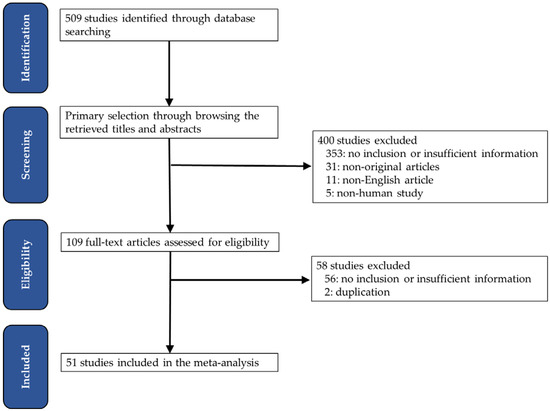

Relevant articles were obtained by searching the PubMed database through 15 February 2023. The following keywords were used in the search: “(tumor–stroma ratio or carcinoma–stroma ratio) AND (cancer or tumor or malignancy or neoplasm or carcinoma) AND (prognosis or prognostic or survival)”. The titles and abstracts of all searched articles were screened for inclusion and exclusion. Included articles had information on the correlation between TSR and survival in malignant tumors. However, non-original articles, such as case reports and review articles, were excluded. Articles not written in English were not included in the present study. Finally, 51 eligible articles were included in the meta-analysis (Table 1). The PRISMA checklist is shown in Supplementary Table S1. In addition, we evaluated eligible studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, and the results are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of eligible studies.

Table 2.

Results of quality assessment using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for eligible studies.

2.2. Data Extraction

All data were extracted from 51 eligible studies [2,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. Extracted data included the author’s information, study location, number of patients analyzed, and high TSR evaluation criteria. The number and survival rates of high and low TSR were also investigated. For the quantitative aggregation of the survival results, the correlation between TSR and survival was analyzed according to the hazard ratio (HR) using one of three methods. In studies that did not take note of HRs or confidence intervals (CIs), these variables were calculated from the presented data using the HR point estimate, the log-rank statistic or its p-value, and the O-E statistic (the difference between the number of observed and expected events) or its variance. If those data were unavailable, HR was estimated using the total number of events, the number of patients at risk in each group, and the log-rank statistic or its p-value. Finally, if the only useful data were in the form of graphical representations of survival distributions, survival rates were extracted at specified times to reconstruct the HR estimate and its variance under the assumption that patients were censored at a constant rate during the time intervals [59]. The published survival curves were read independently by two authors to reduce reading variability. The HRs were then combined into an overall HR using Peto’s method [60]. Two independent authors obtained all data (Pyo J.S. and Kim N.Y.).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

The meta-analysis was performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software package (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). The high TSR rate was investigated in various malignant tumors. TSR’s prognostic impact was evaluated, dividing survival into overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS). Heterogeneity between the studies was checked by the Q and I2 statistics and expressed as p-values. Additionally, sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the heterogeneity of eligible studies and each study’s impact on the combined effects. In the meta-analysis, because the eligible studies used various malignant tumors and populations, a random-effects model rather than a fixed-effects model was more suitable. Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were used; if significant publication bias was found, the fail-safe N and trim–fill tests were also used to confirm the degree of publication bias. The results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Selection and Characteristics of the Studies

- A primary search using the PubMed database found 509 relevant articles. In screening and reviewing, 409 were excluded due to inapplicable or insufficient information. Among the remaining articles, 49 reports were excluded for the following reasons: non-original articles (n = 31), non-human studies (n = 5), a language other than English (n = 11), and articles including duplicated patients (n = 2) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow chart of the searching strategy.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the searching strategy.

3.2. Prevalence of High Tumor–Stroma Ratio

The estimated high TSR rate was 0.605 (95% CI 0.565–0.644) in overall tumors (Table 3). The highest rate of high TSR was found in endometrial cancer (0.865, 95% CI 0.827–0.895). Other female genital tract cancers, the cervical and ovary cancers, showed 0.785 (95% CI 0.713–0.842) and 0.601 (95% CI 0.417–0.761), respectively. The estimated rates of colorectal, esophageal, and stomach cancers were 0.622 (95% CI 0.556–0.683), 0.529 (95% CI 0.312–0.736), and 0.448 (95% CI 0.387–0.509), respectively. Breast cancers showed a high TSR of 50.1%. Next, subgroup analysis based on criteria for high TSR was performed because eligible studies used various criteria for high TSR. The criteria ranged from 30% to 70%. The high TSR rates for <50%, 50%, and >50% cut-off subgroups were 0.624 (95% CI 0.515–0.721), 0.609 (95% CI 0.567–0.649), and 0.399 (95% CI 0.302–0.506), respectively.

Table 3.

The estimated rates of high tumor–stroma ratio in various malignant tumors.

3.3. Correlation between High Tumor–Stroma Ratio and Survival

In overall cases, high TSR was significantly correlated with better OS and DFS compared to low TSR (HR 0.631, 95% CI 0.542–0.734, and HR 0.564, 95% CI 0.476–0.669, respectively; Table 4 and Table 5). Significant correlations with OS were found in breast, cervical, colorectal, esophageal, head and neck, ovary, stomach, and urinary tract cancers. In addition, there were significant correlations of DFS in breast, cervical, colorectal, esophageal, laryngeal, lung, and stomach cancers. However, in endometrial and pancreas cancers, high TSR was significantly correlated with a worse prognosis. In subgroup analysis based on evaluation criteria, there were significant correlations between high TSR and better OS and DFS in the subgroups with criteria <50% and 50%. In the subgroup with criteria >50%, patients with high TSR had a better OS, but not DFS, compared to patients with low TSR.

Table 4.

The correlation between high tumor–stroma ratio and overall survival in various malignant tumors.

Table 5.

The correlation between high tumor–stroma ratio and disease-free survival in various malignant tumors.

4. Discussion

In the present meta-analysis, the rates of high TSR were evaluated in various malignant tumors. In addition, the correlation between TSR and survival was investigated through a meta-analysis. Previous studies used variable methods for evaluating TSR. The criterion for high TSR is usually 50% through visual inspection. Therefore, a meta-analysis is more useful for understanding the prognostic implication of TSR. The present study is the first meta-analysis, to the best of our knowledge, to elucidate the prognostic impacts of TSR according to malignant tumors and evaluation criteria.

Regardless of the origin of epithelial tumors, malignant tumors initiate through invasion into the basement membrane and progress to the stroma. This process induces changes in the characteristics of the stroma, including fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition, through the production of cytokines and enzymes with the surrounding stroma [61,62,63,64]. Therefore, in malignant tumors, the interaction between tumor cells and stroma is important [33]. Malignant tumors have intratumoral stroma and an interface with peritumoral stroma. The definition of TSR is the proportion of tumor area in the overall tumor, including the stroma. Tumors with low TSR, which have abundant stroma, are considered active interactions between tumor cells and stroma. The tumor growth and progression are associated with the tumor microenvironment [65]. However, the detailed evaluation of the tumor environment through hematoxylin and eosin staining can be limited. TSR can be considered as a simplified analysis of the interaction between tumor cells and stroma. Therefore, the assessment of TSR may be applicable for predicting the prognosis through the routine evaluation of histology.

Recently, assessments using image analyzers have been increasingly used in research and practice. Evaluation of TSR is performed through various methods, including eyeballing and the use of a digital image analyzer [15]. The assessment of TSR can be affected by multiple factors, including the discrepancy between investigators. The evaluation criteria for high TSR are yet to be elucidated. To diminish the discrepancy caused by various factors, an image analyzer is used for evaluating TSR. The value of TSR can be different according to the evaluation foci within the tumor. The evaluation area can also affect the value of TSR, and two-tier or three-tier classification can affect the prognostic impact of TSR. Further cumulative studies for the prognostic implication of TSR gradients by evaluation criteria will be needed.

Most eligible studies investigated the evaluation criterion of 50% for high TSR. However, the previous meta-analysis showed no results for evaluation criteria [66]. With the increasing cut-off for high TSR, the rate of high TSR is lowering. The rates of high TSR were 0.624, 0.609, and 0.399 in the <50%, 50%, and >50% cut-off subgroups, respectively. In the present study, patients with high TSR had better OS and DFS than those with low TSR in the <50% and 50% cut-off subgroups. However, in the subgroup with criteria >50%, patients with high TSR had a better OS, but not DFS. In the assessment of OS in criteria >50%, colorectal cancers are only included. However, in the assessment of DFS in criteria >50%, one breast cancer study and one colorectal cancer study were included. Among these studies, there was no significant correlation between high TSR and better prognosis in a study on only breast cancer [50]. In subgroup analysis, breast cancers showed a significant correlation between high TSR and better DFS (Table 5). Although there may be a difference in the degree of HR, it can be considered that there is no significant difference in the relationship with prognosis according to the criteria.

In a pathological examination, the evaluation criteria of TNM staging differ according to malignant tumors. For example, in lung cancers, the pT stage is evaluated by tumor size and invasion depth [1]. The invasive size, rather than the overall tumor size, was significantly correlated with lung adenocarcinoma [67,68]. In addition, lung adenocarcinoma includes various histologic subtypes, such as lepidic, acinar, micropapillary, papillary, and solid adenocarcinomas. Although these subtypes have variable amounts of stroma, the specific correlation between histologic subtypes and stroma amount is not clear. Evaluating the TSR of lepidic adenocarcinoma, which has similarities with the lung’s normal parenchyma, may not be easy. Ichikawa et al. reported that lung adenocarcinoma with low TSR was significantly correlated with favorable tumor behaviors [19]. However, Xi et al. reported a significant correlation between low TSR and worse prognosis [33]. Xi’s report included adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. However, the prognostic impact based on histologic subtypes of non-small cell lung cancers could not be elucidated in that study. In a previous study, TSR was not correlated with various clinicopathological characteristics, including histologic subtypes, pT stage, pN stage, and pTNM stage [33].

A previous meta-analysis was reported for the prognostic roles of TSR in gastrointestinal tract cancers [66]. There were significant correlations between high TSR and better OS in colorectal, stomach, and liver cancers. However, some discrepancies are present compared to our results. In the current meta-analysis, there was no significant correlation between TSR and OS in liver cancer. The highest and lowest rates of high TSR were found in endometrial cancer (86.5%) and stomach cancer (44.8%), respectively. This discrepancy can be caused by different characteristics of malignant tumors. Endometrial intraepithelial neoplasm, which is a precursor of endometrial cancer, has less stroma compared to the tumor area. Interestingly, for endometrial carcinoma, it was shown that high TSR was significantly correlated with worse OS and DFS. However, cervical cancers showed a significant correlation between TSR and better OS and DFS. In addition, high TSR of ovarian cancers was significantly correlated with better OS. These results suggest that the biology of tumor–stroma interactions may differ amongst cancer types.

There were some limitations in the current meta-analysis. First, high TSR rates based on histologic subtypes of each tumor could not be investigated due to insufficient information. Second, each study was not described for the evaluation area or section. In addition, it is uncertain whether the evaluation foci for TSR are hot spots or representative regions. Third, a comparison between eyeballing and image analyzers could not be performed due to insufficient information on eligible studies. Fourth, we were unable to conduct analyses by criteria subgroup for high TSR for each cancer type due to insufficient information.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results showed that high TSR rates were different between malignant tumors. High TSR was significantly correlated with better survival rates, although some malignant tumors had no correlation or opposite correlation. Our results show that endometrial and pancreatic cancers are correlated with a poor prognosis. TSR can be useful for predicting prognosis through a routine microscopic examination of malignant tumors. Further studies for standardized histopathologic criteria will be needed in the application of TSR.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/medicina59071258/s1, Table S1. PRISMA checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-S.P. and N.Y.K.; methodology, J.-S.P.; software, J.-S.P.; data curation, K.-W.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-S.P. and N.Y.K.; writing—review and editing, D.-W.K.; funding acquisition, D.-W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article was supported by the research fund of the Catholic University of Korea, Industry-Academic Cooperation Foundation (2022-81-001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Karpathiou, G.; Vieville, M.; Gavid, M.; Camy, F.; Dumollard, J.M.; Magné, N.; Froudarakis, M.; Prades, J.M.; Peoc’h, M. Prognostic significance of tumor budding, tumor-stroma ratio, cell nests size, and stroma type in laryngeal and pharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Head Neck 2019, 41, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissell, M.J.; Radisky, D. Putting tumours in context. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremnes, R.M.; Dønnem, T.; Al-Saad, S.; Al-Shibli, K.; Andersen, S.; Sirera, R.; Camps, C.; Marinez, I.; Busund, L.T. The role of tumor stroma in cancer progression and prognosis: Emphasis on carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 2011, 6, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, S.; Ishii, G.; Hashimoto, H.; Kuwata, T.; Nagai, K.; Date, H.; Ochiai, A. Podoplanin-expressing cancer-associated fibroblasts lead and enhance the local invasion of cancer cells in lung adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 137, 784–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, G.; Ochiai, A.; Neri, S. Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of cancer-associated fibroblast within the tumor microenvironment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 99, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, W.D.; Asamura, H.; Bankier, A.A.; Beasley, M.B.; Detterbeck, F.; Flieder, D.B.; Goo, J.M.; MacMahon, H.; Naidich, D.; Nicholson, A.G.; et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Coding T Categories for Subsolid Nodules and Assessment of Tumor Size in Part-Solid Tumors in the Forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification of Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 2016, 11, 1204–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almangush, A.; Heikkinen, I.; Bakhti, N.; Mäkinen, L.K.; Kauppila, J.H.; Pukkila, M.; Hagström, J.; Laranne, J.; Soini, Y.; Kowalski, L.P.; et al. Prognostic impact of tumour-stroma ratio in early-stage oral tongue cancers. Histopathology 2018, 72, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurello, P.; Berardi, G.; Giulitti, D.; Palumbo, A.; Tierno, S.M.; Nigri, G.; D’Angelo, F.; Pilozzi, E.; Ramacciato, G. Tumor-Stroma Ratio is an independent predictor for overall survival and disease free survival in gastric cancer patients. Surg. J. R. Coll. Surg. Edinb. Irel. 2017, 15, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Liu, X. Prognostic Significance of the Tumor-Stroma Ratio in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 589301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courrech Staal, E.F.; Wouters, M.W.; van Sandick, J.W.; Takkenberg, M.M.; Smit, V.T.; Junggeburt, J.M.; Spitzer-Naaykens, J.M.; Karsten, T.; Hartgrink, H.H.; Mesker, W.E.; et al. The stromal part of adenocarcinomas of the oesophagus: Does it conceal targets for therapy? Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kruijf, E.M.; van Nes, J.G.; van de Velde, C.J.; Putter, H.; Smit, V.T.; Liefers, G.J.; Kuppen, P.J.; Tollenaar, R.A.; Mesker, W.E. Tumor-stroma ratio in the primary tumor is a prognostic factor in early breast cancer patients, especially in triple-negative carcinoma patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 125, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, T.J.; van de Velde, C.J.; van Pelt, G.W.; Kroep, J.R.; Julien, J.P.; Smit, V.T.; Tollenaar, R.A.; Mesker, W.E. Prognostic significance of the tumor-stroma ratio: Validation study in node-negative premenopausal breast cancer patients from the EORTC perioperative chemotherapy (POP) trial (10854). Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 139, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourado, M.R.; Miwa, K.Y.M.; Hamada, G.B.; Paranaíba, L.M.R.; Sawazaki-Calone, Í.; Domingueti, C.B.; Ervolino de Oliveira, C.; Furlan, E.C.B.; Longo, B.C.; Almangush, A.; et al. Prognostication for oral squamous cell carcinoma patients based on the tumour-stroma ratio and tumour budding. Histopathology 2020, 76, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geessink, O.G.F.; Baidoshvili, A.; Klaase, J.M.; Ehteshami Bejnordi, B.; Litjens, G.J.S.; van Pelt, G.W.; Mesker, W.E.; Nagtegaal, I.D.; Ciompi, F.; van der Laak, J. Computer aided quantification of intratumoral stroma yields an independent prognosticator in rectal cancer. Cell. Oncol. 2019, 42, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, T.F.; Kjær-Frifeldt, S.; Lindebjerg, J.; Rafaelsen, S.R.; Jensen, L.H.; Jakobsen, A.; Sørensen, F.B. Tumor-stroma ratio predicts recurrence in patients with colon cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huijbers, A.; Tollenaar, R.A.; v Pelt, G.W.; Zeestraten, E.C.; Dutton, S.; McConkey, C.C.; Domingo, E.; Smit, V.T.; Midgley, R.; Warren, B.F.; et al. The proportion of tumor-stroma as a strong prognosticator for stage II and III colon cancer patients: Validation in the VICTOR trial. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2013, 24, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huijbers, A.; van Pelt, G.W.; Kerr, R.S.; Johnstone, E.C.; Tollenaar, R.; Kerr, D.J.; Mesker, W.E. The value of additional bevacizumab in patients with high-risk stroma-high colon cancer. A study within the QUASAR2 trial, an open-label randomized phase 3 trial. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, T.; Aokage, K.; Sugano, M.; Miyoshi, T.; Kojima, M.; Fujii, S.; Kuwata, T.; Ochiai, A.; Suzuki, K.; Tsuboi, M.; et al. The ratio of cancer cells to stroma within the invasive area is a histologic prognostic parameter of lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2018, 118, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairaluoma, V.; Kemi, N.; Pohjanen, V.M.; Saarnio, J.; Helminen, O. Tumour budding and tumour-stroma ratio in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 123, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemi, N.; Eskuri, M.; Herva, A.; Leppänen, J.; Huhta, H.; Helminen, O.; Saarnio, J.; Karttunen, T.J.; Kauppila, J.H. Tumour-stroma ratio and prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labiche, A.; Heutte, N.; Herlin, P.; Chasle, J.; Gauduchon, P.; Elie, N. Stromal compartment as a survival prognostic factor in advanced ovarian carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer Off. J. Int. Gynecol. Cancer Soc. 2010, 20, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yuan, S.L.; Han, Z.Z.; Huang, J.; Cui, L.; Jiang, C.Q.; Zhang, Y. Prognostic significance of the tumor-stroma ratio in gallbladder cancer. Neoplasma 2017, 64, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Guan, X.; Wu, X.; Hao, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Tumor-stroma ratio is an independent predictor for survival in early cervical carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 132, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Z.; Cai, X.; Weng, X.; Xiao, H.; Du, C.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, L.; Xie, H.; Sun, K.; Wu, J.; et al. Tumor-stroma ratio is a prognostic factor for survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients after liver resection or transplantation. Surgery 2015, 158, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascitti, M.; Zhurakivska, K.; Togni, L.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Almangush, A.; Balercia, P.; Balercia, A.; Rubini, C.; Lo Muzio, L.; Santarelli, A.; et al. Addition of the tumour-stroma ratio to the 8th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system improves survival prediction for patients with oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Histopathology 2020, 77, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayiotou, H.; Orsi, N.M.; Thygesen, H.H.; Wright, A.I.; Winder, M.; Hutson, R.; Cummings, M. The prognostic significance of tumour-stroma ratio in endometrial carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Liu, J.; Yang, G.; Li, Y. The tumor-stromal ratio as a strong prognosticator for advanced gastric cancer patients: Proposal of a new TSNM staging system. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsuvareeyakul, T.; Khunamornpong, S.; Settakorn, J.; Sukpan, K.; Suprasert, P.; Intaraphet, S.; Siriaunkgul, S. Prognostic evaluation of tumor-stroma ratio in patients with early stage cervical adenocarcinoma treated by surgery. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 4363–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, T.P.; Oosting, J.; van Pelt, G.W.; Mesker, W.E.; Tollenaar, R.; Morreau, H. Molecular profiling of colorectal tumors stratified by the histological tumor-stroma ratio—Increased expression of galectin-1 in tumors with high stromal content. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 31502–31515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, R.; Baidoshvili, A.; Zoidze, S.; Elferink, M.A.G.; Berkel, A.E.M.; Klaase, J.M.; van Diest, P.J. Tumor-stroma ratio as prognostic factor for survival in rectal adenocarcinoma: A retrospective cohort study. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 9, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelaar, F.J.; van Pelt, G.W.; van Leeuwen, A.M.; Willems, J.M.; Tollenaar, R.A.; Liefers, G.J.; Mesker, W.E. Are disseminated tumor cells in bone marrow and tumor-stroma ratio clinically applicable for patients undergoing surgical resection of primary colorectal cancer? The Leiden MRD study. Cell. Oncol. 2016, 39, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, K.X.; Wen, Y.S.; Zhu, C.M.; Yu, X.Y.; Qin, R.Q.; Zhang, X.W.; Lin, Y.B.; Rong, T.H.; Wang, W.D.; Chen, Y.Q.; et al. Tumor-stroma ratio (TSR) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients after lung resection is a prognostic factor for survival. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 4017–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Yuan, J.P.; Chen, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, L.W.; Xiong, B. Prognostic Significance of the Tumor-Stromal Ratio in Invasive Breast Cancer and a Proposal of a New Ts-TNM Staging System. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 9050631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, M. Tumour Budding and Tumour Stroma Ratio are Reliable Predictors for Death and Recurrence in Elderly Stage I Colon Cancer Patients. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, Z.X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, F.; Cheng, Y.F. The tumor-stroma ratio is an independent predictor for survival in nasopharyngeal cancer. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2014, 37, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xu, J.; Shen, H.; Dong, W.; Ni, Y.; Du, J. Tumor-stroma ratio is an independent predictor for survival in NSCLC. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 11348–11355. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, L.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, S.; Wu, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, Y. The tumor-stroma ratio is an independent predictor of survival in patients with 2018 FIGO stage IIIC squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix following primary radical surgery. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 156, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelnasr, L.S.; El-Rebey, H.S.; Mohamed, A.; Abdou, A.G. The Prognostic Impact of Tumor Border Configuration, Tumor Budding and Tumor Stroma Ratio in Colorectal Carcinoma. Turk. Patoloji Derg. 2023, 39, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessandrini, L.; Ferrari, M.; Taboni, S.; Sbaraglia, M.; Franz, L.; Saccardo, T.; Del Forno, B.M.; Agugiaro, F.; Frigo, A.C.; Dei Tos, A.P.; et al. Tumor-stroma ratio, neoangiogenesis and prognosis in laryngeal carcinoma. A pilot study on preoperative biopsies and matched surgical specimens. Oral Oncol. 2022, 132, 105982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, S.; Banga, P.; Meena, N.; Chauhan, G.; Sakhuja, P.; Agarwal, A.K. Prognostic significance of tumour budding, tumour-stroma ratio and desmoplastic stromal reaction in gall bladder carcinoma. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 76, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Li, D.; Liu, B.; Rao, J.; Meng, H.; Lin, W.; Fan, T.; Hao, B.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Z.; et al. The prognostic value of tumor-stromal ratio combined with TNM staging system in esophagus squamous cell carcinoma. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Cai, H.; Song, F.; Zhu, Y.; Hou, C.; Hou, J. Tumor-stroma ratio is a crucial histological predictor of occult cervical lymph node metastasis and survival in early-stage (cT1/2N0) oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022, 51, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, H.; Kudou, M.; Shiozaki, A.; Kosuga, T.; Shimizu, H.; Kiuchi, J.; Arita, T.; Konishi, H.; Komatsu, S.; Kuriu, Y.; et al. Value of the Tumor Stroma Ratio and Structural Heterogeneity Measured by a Novel Semi-Automatic Image Analysis Technique for Predicting Survival in Patients with Colon Cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, G.; Pyo, J.S.; Kim, N.Y.; Kang, D.W. Clinicopathological Significances of Tumor-Stroma Ratio (TSR) in Colorectal Cancers: Prognostic Implication of TSR Compared to Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α Expression and Microvessel Density. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Su, M.; Xu, Q.; Wang, C.; Yuan, X.; Han, Z. Tumour-stroma ratio is a valuable prognostic factor for oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.Y.; Abdul-Ghafar, J.; Chong, Y.; Yim, K. Calculated Tumor-Associated Neutrophils Are Associated with the Tumor-Stroma Ratio and Predict a Poor Prognosis in Advanced Gastric Cancer. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, B.; Shi, X.; Gao, S.; Ni, C.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, S.; Xu, J.; et al. Pros and Cons: High Proportion of Stromal Component Indicates Better Prognosis in Patients With Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma-A Research Based on the Evaluation of Whole-Mount Histological Slides. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ç.; Okcu, O.; Şen, B.; Bedir, R. An easy and practical prognostic parameter: Tumor-stroma ratio in Luminal, Her2, and triple-negative breast cancers. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2022, 68, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Xiao, F.; Chen, Y.Y.; Yuan, J.P.; Liu, X.H.; Wang, L.W.; Xiong, B. Computerized Assessment of the Tumor-stromal Ratio and Proposal of a Novel Nomogram for Predicting Survival in Invasive Breast Cancer. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 3427–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Jiang, E.; Shang, Z. Prognostic value of tumor-stroma ratio in oral carcinoma: Role of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Oral Dis. 2022, 29, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.V.D.; da Silva Dolens, E.; Paranaíba, L.M.R.; Ayroza, A.L.C.; Gurgel Rocha, C.A.; Almangush, A.; Salo, T.; Brennan, P.A.; Coletta, R.D. Exploring the combination of tumor-stroma ratio, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and tumor budding with WHO histopathological grading on early-stage oral squamous cell carcinoma prognosis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2022, 52, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, M.A.; Philipsen, M.W.; Postmus, P.E.; Putter, H.; Tollenaar, R.A.; Cohen, D.; Mesker, W.E. The prognostic value of the tumor-stroma ratio in squamous cell lung cancer, a cohort study. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2020, 25, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, M.A.; Tilki, M.; Gönültaş, A.; Aker, F.; Kayaoglu, S.A.; Okuyan, G. Is the tumor-stroma ratio a prognostic factor in gallbladder cancer? Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2022, 68, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhong, W.; Li, C.; Hong, P.; Xia, K.; Lin, R.; Cheng, S.; Wang, B.; Yang, M.; Chen, J.; et al. The tumour-associated stroma correlates with poor clinical outcomes and immunoevasive contexture in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma: Results from a multicenter real-world study (TSU-01 Study). Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, D.; Ju, X.; Luo, B.; Guan, F.; He, H.; Yan, H.; Yuan, J. Tumour stroma ratio is a potential predictor for 5-year disease-free survival in breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Ni, X.; Yang, S.; Jiao, P.; Wu, J.; Xiong, L.; Yuan, J.; Wang, J.; Jian, J.; et al. Machine Learning Quantified Tumor-Stroma Ratio Is an Independent Prognosticator in Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Pelt, G.W.; Kjær-Frifeldt, S.; van Krieken, J.H.J.M.; Al Dieri, R.; Morreau, H.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; Sørensen, F.B.; Mesker, W.E. Scoring the tumor-stroma ratio in colon cancer: Procedure and recommendations. Virchows Arch. 2018, 473, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, M.K.; Torri, V.; Stewart, L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 2815–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.; Peto, R.; Lewis, J.; Collins, R.; Sleight, P. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: An overview of the randomized trials. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 1985, 27, 335–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmings, C. Is carcinoma a mesenchymal disease? The role of the stromal microenvironment in carcinogenesis. Pathology 2013, 45, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, J.M.; Sprandio, J.; Cognetti, D.; Luginbuhl, A.; Bar-ad, V.; Pribitkin, E.; Tuluc, M. Tumor microenvironment in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Semin. Oncol. 2014, 41, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.W.; Lim, J.B. Role of the tumor microenvironment in the pathogenesis of gastric carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 1667–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, M.P.; Pauley, R.; Heppner, G. Host microenvironment in breast cancer development: Extracellular matrix-stromal cell contribution to neoplastic phenotype of epithelial cells in the breast. Breast Cancer Res. 2003, 5, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietras, K.; Ostman, A. Hallmarks of cancer: Interactions with the tumor stroma. Exp. Cell Res. 2010, 316, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Song, W.; Wang, K.; Zou, S. Tumor-stroma ratio(TSR) as a potential novel predictor of prognosis in digestive system cancers: A meta-analysis. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2017, 472, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, A.; Motoi, N.; Riely, G.J.; Sima, C.S.; Gerald, W.L.; Kris, M.G.; Park, B.J.; Rusch, V.W.; Travis, W.D. Impact of proposed IASLC/ATS/ERS classification of lung adenocarcinoma: Prognostic subgroups and implications for further revision of staging based on analysis of 514 stage I cases. Mod. Pathol. Off. J. United States Can. Acad. Pathol. Inc. 2011, 24, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warth, A.; Muley, T.; Meister, M.; Stenzinger, A.; Thomas, M.; Schirmacher, P.; Schnabel, P.A.; Budczies, J.; Hoffmann, H.; Weichert, W. The novel histologic International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society classification system of lung adenocarcinoma is a stage-independent predictor of survival. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1438–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).