Abstract

Background and Objectives: This project was developed from anecdotal evidence of varied practices around antibiotic prescribing in dental procedures. The aim of the study was to ascertain if there is evidence to support whether antibiotic (AB) use can effectively reduce postoperative infections after dental implant placements (DIPs). Materials and Methods: Following PRISMA-P© methodology, a systematic review of randomised controlled clinical trials was designed and registered on the PROSPERO© database. Searches were performed using PubMed®, Science Direct® and the Cochrane© Database, plus the bibliographies of studies identified. The efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics, independent of the regimen used, versus a placebo, control or no therapy based on implant failure due to infection was the primary measured outcome. Secondary outcomes were other post-surgical complications due to infection and AB adverse events. Results: Twelve RCTs were identified and analysed. Antibiotic use was reported to be statistically significant in preventing infection (p < 001). The prevention of complications was not statistically significant (p = 0.96), and the NNT was >5 (14 and 2523 respectively), which indicates that the intervention was not sufficiently effective to justify its use. The occurrence of side effects was not statistically significant (p = 0.63). NNH was 528 indicating that possible harm caused by the use of ABs is very small and does not negate the AB use when indicated. Conclusion: The routine use of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infection in dental implant placement was found to be not sufficiently effective to justify routine use. Clear clinical assessment pathways, such as those used for medical conditions, based on the patients’ age, dental risk factors, such as oral health and bone health, physical risk factors, such as chronic or long-term conditions and modifiable health determinants, such as smoking, are required to prevent the unnecessary use of antibiotics.

1. Introduction

A dental implant (DI) placement (DIP) procedure, with artificial root placement, is the substitution of one or more missing or defective natural teeth. It has become the definitive therapy for the restoration of entire dental arches or for partially and fully edentulous patients [1]. DI surgery can be performed in an ambulatory (outpatient) setting using local or general anaesthesia depending upon the individual preferences, health statutes and case complexity [2]. The most common fabrication materials for DIs are metals and metal alloys, polymers and ceramics [3]. Metals and metal alloys have been widely used due to advantages over other materials, including good mechanical properties, biological compatibility and excellent corrosion resistance [3,4,5].

To function successfully, the implant must be surrounded by healthy and stable tissues [4,5,6]. DIP has become a routine treatment option due to its high survival and success rates, offering a predictable solution for tooth replacement [7,8]. Large-scale studies reported survival rates between 97% and 75% over 10 years and 20 years, respectively [9,10]. Although its success rate is very high, failures requiring removal occasionally occur [11,12].

Several factors influence the DI failure rate, including poor quantity and quality of bone, inappropriate prosthesis design, inadequate number of DIs, the absence or loss of implant integration with hard and soft tissues and the practitioner’s experience. Patient-related predictors of DIP failure include an advanced age, systemic diseases, smoking, unresolved caries or infection, poor oral hygiene and parafunctional habits [13]. Lifestyle-related factors may lead to the disrupted activation of tissue healing (e.g., smoking status negatively affects the oral microbial profile and alters the microvascular environment) [14].

The DI can be made in a single step, which is called immediate loading [15]. DIP can be impacted by the presence of a bacterial load at the time of the surgery [16]. The most common organisms in endodontical procedures are Propionibacterium acnes, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus intermedius, Wolinella recta and Prophyromonas and Prevotella species. Non-integrated or failed implants exhibit a mixed flora type of infection, such as the Gram-negative anaerobic rods Bacteroides spp. and Fusobacterium spp. [17]. Other species identified in failed implants are Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Prophyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia [18]. The primary criteria for assessing the successful osseointegration and survival of DIs are the implant mobility, preimplant bone loss (>1.5 mm) and the condition of the surrounding soft tissue (e.g., suppression, bleeding, pain) and infection. Patient satisfaction with the appearance, presence of discomfort and ability to function normally are used to determine the DI success [19].

Existing guidance is limited; prophylactic antibiotic use is not recommended in otherwise healthy individuals but may be required in those with risk factors and/or co-morbidities, but in current studies, the variations in the design and methodology used and how the outcomes were measured has made it difficult to combine or to produce clear evidence to inform the development of guidance for the appropriate use of antibiotics in DIP or the timing of their use. This review highlights these variations and limitations and provides recommendations for greater standardisation of methods and outcome measures in future studies to build a clearer base of evidence for practice in at-risk patient groups.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review aims to assess the efficacy and safety of ABs among patients undergoing DI placement procedures. The review objectives included the identification of the type of ABs used, understanding how effective ABs are in reducing or preventing infection in DIPs and what is the incidence rate of AB adverse effects.

A systematic review was designed and implemented to investigate the efficacy and safety of ABs (independent of the type of ABs used, dose administered and timing of course of administration (preoperatively, postoperatively or both), as part of treatment, with or without AB therapy (no treatment or placebo) on DI failure and postoperative complications during DIP procedures.

The study protocol followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-P©, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada) statement and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviewers’ methodological guidelines (Cochrane collaboration, Oxford, UK) [20]. This systematic review was registered in the PROSPERO© (National Institute of Health, York, UK) database CRD42021269522. All statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan®) statistical software version 5.4.1 (Cochrane collaboration, Oxford, UK). Risk ratios (RRs) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported for dichotomous outcomes. To calculate the pooled RRs of the different studies, the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (M-H2) and 95% CI for effect measurement in meta-analysis was employed. Meta-analysis was used to combine outcome data from different studies using random effects or a fixed effect model [21].

The results were aggregated using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (M-H2). The efficacy of the AB was assessed using the risk ratio (RR). The pooled RR with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was chosen as the effect size.

The effectiveness of the treatment with ABs to prevent infection, which can lead to implant failure or implant complications, was assessed using the number needed to treat (NNT), and safety was assessed by calculating the number needed to treat to cause harm (NNH), where an NNT of 1–5 is desirable [22,23]. All decimals in the NNT have been rounded up to the nearest whole number.

The statistical unit for “implant failure by patients”, “post-operative infection” and AB adverse events was the number of patients. The statistical unit for implant failure by implant was the number of implants. No restriction criteria were applied for the definition of each outcome reported in this review.

2.1. Search Strategy

Search strategies utilised a combination of keywords using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). No language limits were applied (date of last search: 17 January 2022). Publications included within PubMed© were searched since January 2000 until 17 January 2022.

The following term combination was used in the PubMed©, Science Direct® and Cochrane© databases: ((Dental Implant insertion OR dental implants OR dental implant OR dental implant surgery OR Dental surgery OR dental implant placement OR oral implant surgery OR implant surgery [MeSH Terms]) AND (Implant failure OR implant loss OR Implant survival OR implant survival)) AND (Antimicrobial or antibacterial or antibacterial or antibiotics or antibiotic)) AND (randomised controlled trials OR controlled clinical trial OR randomised controlled trials OR random allocation OR single-blind method OR single-blind method OR double-blind method OR clinical trial OR clinical trials OR placebos OR placebo-controlled randomised clinical trial) AND (efficacy OR Effect OR effectiveness)) AND (“Antimicrobial” or “antibiotics”, “prophylactic” OR “prophylaxis” OR “pre-operative” OR “preoperative” OR “peri operative” OR “postoperative” OR “preventative”). Issues of interest, according to the study population, intervention, comparative group, outcome measured and study design (PICOS [24]), were as follows:

(P): Healthy adult patients over 15 yrs. Of any gender subjected to DIP.

(I): Oral or systemic AB, independent of the type of ABs used, dose administered and timing of administration (preoperatively and/or postoperatively).

(C): AB versus no AB treatment or control or placebo.

(O): Type of outcome measures: Primary outcome of interest was the post-implant infection leading to implant failure; secondary outcomes: other post-surgical complications due to infection and AB adverse events.

(S): Primary care, community or hospital setting.

2.2. Selection Criteria

Studies were included in the review when they were as follows:

- Double-blind and placebo-controlled randomised clinical trial.

- Patients over 15 years of age.

- Patients undergoing DIP procedure/s.

- Only oral or systemic route of AB administration.

Studies comparing the use of any AB, independent of the type of ABs used, dose administered, timing of course of administration (preoperatively, postoperatively or both; alone or no treatment or control with no AB use) following the DIP procedure.

Studies were excluded from the review when they were as follows:

- Systematic and meta-analysis review.

- Studies conducted prior to the year 2000.

- Comparative AB therapy with no placebo/control.

- Trials comparing AB therapy versus another AB.

2.3. Selected Studies Summary

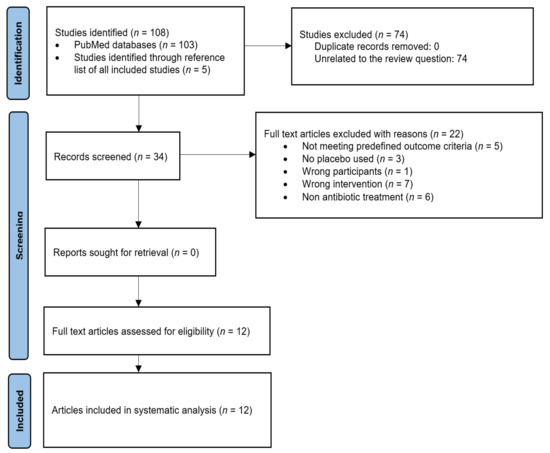

The initial search yielded 103 studies. An additional five RCTs were identified through a manual search of the similar articles and reference lists of included studies. After an investigation of titles and then abstracts, 74 articles were considered to be ineligible for inclusion. The full texts of 34 eligible articles were then reviewed, and 22 were excluded, leaving 12 studies that accurately fit the inclusion criteria. Selected RCTs were read in full text, by two independent reviewers. A PRISMA flowchart of the screening process for the systematic review and meta-analysis was developed (Figure 1). Following a review of these articles, 12 RCTs met the criteria for inclusion in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart showing the article selection process.

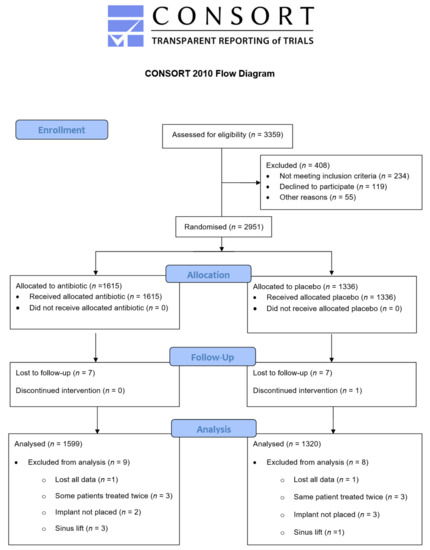

A flow diagram of the included study population, reported according to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT, The EQUATOR Network and UK EQUATOR Centre, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, University of Oxford, Botnar Research Centre, Windmill Road, Oxford, OX3 7LD, UK) is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram.

3. Results

Five corresponding authors were contacted for clarification of the study design via e-mail inquiries [25,26,27,28,29], and two authors were contacted for clarification on the number of patients with implant failure, who provided the missing data; however, three authors did not respond [26,27,28]. Table 1 and Table 2 describe the characteristics of the included studies and the reviewer comments. Six studies identified DI failure by number of patients, eight studies investigated the number of implants failed by the DI, eight assessed comparative data on postoperative complications and five reported data on the total adverse events that occurred between groups during the study period. Due to the small number of studies included in this meta-analysis, a funnel plot was not assessed [30].

Table 1.

Implant studies summary.

Table 2.

The intervention effect of selected studies.

Informed consent was reported in all studies except in Abu-Ta’a et al. [32] and Laskin et al. [37]. Only Caiazzo et al. [25], Esposito et al. [31], Durand et al. [29] and Esposito et al. [36] did not describe their ethical clearance or approval. Six studies reported both participant consent and ethics approvals [26,27,28,33,34,35].

One study reported preoperative antibacterial mouthwash [27], three studies reported postoperative oral hygiene [35,36,37] and six studies reported that patients had pre- and postoperative oral hygiene [25,28,29,31,32,33]. One study reported both preoperative oral hygiene and the intravenous or intramuscular administration of 4 mg of dexamethasone for the postoperative period [26]. One RCT did not report on oral hygiene [34]. Seven implemented additional therapies with anti-inflammatory and pain relief medications postoperatively [25,26,27,28,29,33,35], whilst five studies did not use additional therapies [31,32,34,36,37]. The type of analgesic used was not described in the study by Tan et al. [27].

Only four studies evaluated the number of supplemental analgesics between the intervention and control groups over the post-operative time points. The number of analgesics consumed in patients who were not given AB was statistically significant in the study by Nolan et al. [33]. However, the number of supplemental analgesics taken by the participants in each group was not significant in Tan et al. [27], Payer et al. [28] and Durand et al. [29]. The remaining studies did not evaluate the pain medication use [25,26,31,32,34,35,36,37].

Standard surgical procedures were performed in seven studies [26,27,28,29,32,33,35], whilst five did not describe their surgical protocol [25,31,34,36,37]. There were seven studies that included smokers [26,27,28,31,32,33,36]. A low level of smoking (<20) was not associated with a risk of postoperative infection and consequent implant failure in six studies. However, the study conducted by Abu-Ta’a et al. [32] included patients who were heavy smokers (>40 cigarettes/day) in their study, and the results indicated that this level of smoking affected the outcome. Five studies did not report on participants’ smoking status [25,29,34,35,37].

Five studies reported that surgery was performed by oral and maxillofacial surgeons [25,26,27,28,34]. Implantologists performed the procedures in Durand et al. [29] and odontologists in the Abu Ta’a et al. [32] study. Dentists were reported in two other studies [31,36]. However, in the Nolan et al. [33] study, the procedure was performed by two postgraduate students supervised by an experienced periodontist. Laskin et al. [37] and Khoury et al. [35] did not report on who performed the procedure. Five studies implemented a one-stage implant installation protocol without the need for a second-stage procedure to expose the implant [27,29,31,32,35]. Six studies implemented two-stage surgery [25,26,28,33,36,37]. The study by Kashani et al. [34] employed both one- and two-stage procedures.

The trial by Payer et al. [28] was supported by a grant from the Foundation of International Team for Implantology (ITI Foundation). Funding for the trial by Anitua et al. [26] was provided by the Biotechnology Institute, Vitoria, Spain. The study by Laskin et al. [37] was USA government-supported research, and there were no restrictions on study design. The studies of Esposito et al. [36] and Esposito et al. [31] did not declare a funding source; however, the placebo and ABs used were donated by a drug company manufacturing generic preparations. These companies were not involved in the design of the study, in the data evaluation or in commenting on the manuscript. Seven studies did not report external funding [25,27,29,32,33,34,35].

No sample size calculation was reported in four studies [32,33,35,37]. Six described their sample size calculation but stated that their planned sample was not achieved leaving their studies insufficiently powered to confirm significance [25,26,28,29,31,36]. Two studies did not indicate whether their calculated sample was achieved [27,34]. All studies reported on the AB type and regimens. No study reported on the agent used as a placebo.

Six studies assessed implant failure as a main outcome in their trial. Each study reporting different definitions of implant failure. Only Nolan et al. [33] did not define “implant failure” in their study.

Caiazzo et al. [25]: implant failure is mechanical implant removal due to the lack of osteointegration.

Esposito et al. [31]: implant failure is an implant mobility measured manually and/or any infection dictating implant removal. The study also reported the number of patients with implant-supported prostheses, and the number of events for prosthetic failure was added to the total number of implant failure events. Prostheses failure was defined as prostheses that could not be placed or prosthesis failure (if secondary to implant failures).

Abu Ta’a et al. [32]: defined a failed implant as the presence of signs of infection and/or radiographic peri-implant radiolucencies that could not respond to a course of ABs and/or judged a failure after performing an explorative flap surgery by an experienced periodontologist.

Kashani et al. [34]: defined implant failure as the removal of an implant for any reason, from implant placement to abutment connection or prosthetic treatment.

Esposito et al. [36]: defined implant failure as implant mobility of each implant, measured manually, and/or any infection dictating implant removal. The study also reported the number of patients with implant-supported prostheses, and the number of events for prosthetic failure was added to the total number of implant failure events. The prostheses failure was defined as prostheses that could not be placed or prosthesis failure if secondary to implant failures.

Four studies did not define postoperative complications [25,34,35,37], whilst eight evaluated the postoperative complications as a main outcome. However, in three studies, the number of events in each group was not reported and only the p value was stated [27,28,33].

Esposito et al. [31]: postoperative complications defined as any complications, such as wound dehiscence, suppuration, fistula, abscess and osteomyelitis.

Anitua et al. [26]: the diagnosis of the presence of postoperative infections or post-implant infection been carried out using clinical criteria, which include inflammation, pain, heat, fever and discharge.

Abu Ta’a et al. [32]: postoperative infection was defined as the presence of purulent drainage (pus) or fistula in the operated region, together with pain or tenderness, localised swelling, redness and heat or fever of more than 38 °C.

Nolan et al. [33]: different variables used to identify post-operative infection and postoperative mortality were defined as swelling, bruising, wound dehiscence and suppuration.

Tan et al. [27]: postsurgical complications defined as flap closure, pain, swelling, suppuration and implant instability.

Payer et al. [28]: post-surgical complication defined as pain, swelling, implant instability, purulent discharge and flap closure.

Durand et al. [29]: postoperative surgery-associated morbidity defined as swelling, bruising(ecchymosis) and suppression.

Esposito et al. [36]: biological complications defined as any biological complications, such as wound dehiscence, suppuration, fistula, abscess and osteomyelitis.

Three studies reported zero adverse events [26,31,32]. Three studies did not define the postoperative AB adverse events [26,29,32]. Two studies defined medication-related adverse events as any postoperative events, such as erythema multiforme, urticaria, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea [31,36]. Other studies neither described adverse events nor reported on their prevalence [25,27,28,33,34,35,37].

3.1. Quality Assessment of the Selected Studies

The quality assessment tool of the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP, McMaster University 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, ON, Canada, L8S 4K1) [38] was used to examine each study against six components. The study quality was assessed independently by two reviewers. Table 3 shows the global quality rating. All studies were classed as moderate–strong.

Table 3.

Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool rating for individual studies.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

3.2.1. Implant Failure Not Prevented by the Use of ABs, by Number of Implants

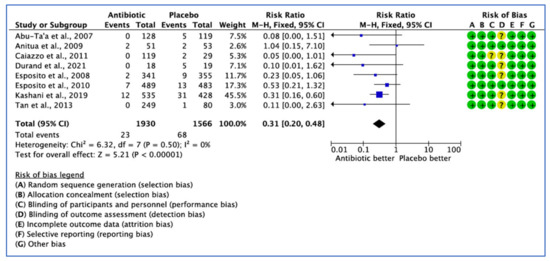

Eight studies evaluated the efficacy of AB treatment. Eight studies analysed the number of implants failed. Out of 1930 implants placed in the AB group, 23 failures were reported against 68 failures from 1566 implants inserted in the placebo group.

As the heterogeneity estimate was low (I2 = 0%), the fixed effect model was used. The pooled estimate RR of 0.31 (95% CI, 0.20–0.48) was significant in the fixed effect model (p < 0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of comparison between AB and placebo, which gives a summary estimate (centre of diamond) and its 95% confidence interval CI (width of diamond) for the number of failed implants by implant. Statistical method: Mantel-Haenszel with fixed-effect model [25,26,27,29,31,32,34,36].

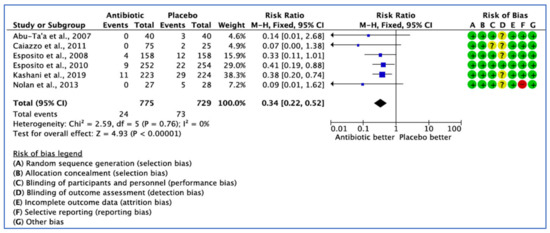

3.2.2. Implant Failure Not Prevented by the Use of ABs, by Patient

Six studies assessed implant failure by the number of patients in their trial, each reporting different definitions of implant failure outcomes. Only the trial conducted by Nolan et al. [33] did not define the implant failure outcome in their study. The fixed effect model was used because I2 < 25%, and the pooled estimate RR of 0.341 (95% CI, 0.22–0.52) was significant (p < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of comparison between AB and placebo, which gives the summary estimate (centre of diamond) and its 95% confidence interval CI (width of diamond) based on implant failure by patients. Statistical method: Mantel-Haenszel with fixed-effect model [25,31,32,33,34,36].

3.2.3. Postoperative Complications Analysis

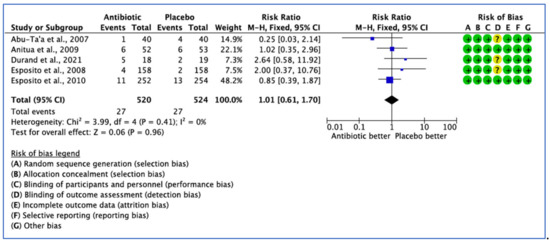

Eight clinical trials provided comparative data on the efficacy of AB treatment compared with the placebo, control or no AB treatment in patients undergoing implant placement based on postoperative complications. However, three studies did not report on the number of events in each group, with only the p value being stated [27,28,33]. Postoperative complications were reported in only five studies. The overall results show that there was no statistical significance difference for postoperative complications between the groups (p = 0.89). The fixed effect model was used because I2 < 25% giving a pooled estimate RR of 1.01 (95% CI, 0.61–1.70), with p = 0.96—not significant (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of comparison between AB and placebo, which gives the summary estimate (centre of diamond) and its 95% confidence interval CI (width of diamond) based on postoperative complications. Statistical method: Mantel-Haenszel with fixed-effect model [26,29,31,32,36].

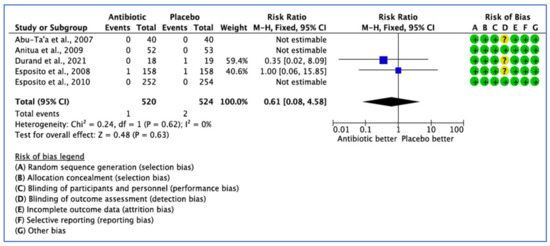

3.2.4. Postoperative Antibiotic Adverse Events Analysis

Five studies reported data on the efficacy of AB treatment compared with placebo, control or no AB treatment based on total adverse events. Three studies reported zero adverse events related to the use of ABs [26,31,32]. Three did not define the postoperative AB adverse events [26,29,32]. In three studies [26,31,32], AB adverse events were appropriately assessed, but no events occurred in both groups (Figure 6). The 95% CI (0.08–5.04) is very wide, indicating a lack of confidence that AB use would affect adverse events (p = 0.63).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of comparison between AB and placebo, which gives the summary estimate (centre of diamond) and its 95% confidence interval CI (width of diamond) based on postoperative adverse events. Statistical method: Mantel-Haenszel with fixed effect model [26,29,31,32,36].

3.2.5. Narrative Analysis of Other Outcomes

There was no significant difference between AB and NOAB groups in implants (p = 0.993) in five studies [25,31,32,34,36] or prothesis failure (p > 0.999) in two studies [31,36].

The terms implant success or implant survival were used interchangeably, with no specific criteria or definition given in most studies. In the study by Laskin et al. [37], the implant survival status was assessed from the time of placement to 36 months according to previous implant experience of the surgeon, implant coating, bone density; patient age, race and gender, incision type, mobility of the implant at placement and use of chlorhexidine; and health status. When implant survival rates were compared according to the patient age, it was observed that patients in all age groups who were provided preoperative AB treatment reported higher implant survival, except in the under 30 group. When implant survival rates were compared according to surgeon’s’ previous implant surgery experience, those surgeons with greater than 50 implant placements prior to the study had a slightly higher implant survival rate of 2.9% when preoperative ABs were used. In addition, a less experienced surgeon (<50 previous implant placements) had an even greater increase in the survival rate of 7.3% when preoperative ABs were used. When implant survival rates were compared according to the use of chlorhexidine in conjunction with preoperative ABs, its use improved implant survival by only 0.9% when preoperative ABs were provided, whereas without preoperative AB coverage, implant survival improved by 5.8%. Comparing both preoperative ABs and chlorhexidine to not using either, there was a substantial increase of 7.8% in implant survival [25,26,27,31,32,33,34,37]. Five studies did not specify the success rate [28,29,35,36].

The clinical diagnosis of an infected surgical wound was specified by Caiazzo et al. [25] as internal and external oedema and internal and external erythema, pain, heat and exudate. In Anitua et al. [26], the presence of infection was recorded at 3 days, 10 days, 1 month and 3 months after the implant placement. Six patients in AB and six patients in placebo groups experienced post-operative infections (not significant). Abu-Ta’a et al. [32] reported that patients self-reported infection using a mirror. One patient from the AB group and four patients in the NOAB groups developed post-operative infections, but significance was not reported. In Nolan et al. [33], post-operative morbidity (swelling, bruising, wound dehiscence and suppuration) was recorded on days 2 and 7 by the same examiner using Boolean variables: post-operative swelling and grading its severity, recorded by two independent examiners, where 0 was no swelling, 1 means mild swelling, 2 means moderate swelling and 3 means severe swelling. Post-operative bruising was significantly higher in the placebo group after 2 days, but not by day 7 post-operatively (p = 0.99). Two patients presented with suppuration, both of whom received a placebo preoperatively (not significant p = 0.49).

Esposito et al. [36] reported complications, such as wound dehiscence, suppuration, fistula, abscess and osteomyelitis, which were measured after one week, two weeks and four months after implant placement, in which they found 11 patients in the AB group had postoperative complications vs. 13 patients in placebo group. Two flap dehiscence events occurred in the placebo group at one week, and four events were observed in the AB group (not significant p = 0.684). Two weeks after implant placement, one peri-implant mucositis was reported in the placebo group and one flap dehiscence in the AB group (not significant p = 0.1). Four months after implant placement, two cases were reported in the placebo group and one mobile implant (provoking severe pain) occurred in the AB group (not significant p = 0.623). Post-surgical complications reported by Tan et al. [27] include flap closure, pain, swelling, suppuration, and implant stability assessed by trained standardised examiners. Postsurgical complications were reported at one week, two weeks and one month after implant installation. Concerning the flap closure, 5% of patients in the placebo group did not achieve complete wound closure compared to 0% for the three other groups. There was no significant difference reported in all other follow-up points by all groups. Of all patients, 17% experienced postoperative pain at one week following implant placement, indicating no statistically significant difference among all AB groups (p > 0.05). The presence of swelling was reported in 21.4% of all subjects at week one (27% in ABs group and 17.5% in placebo). This resulted in no statistically significant difference among all groups at any time (p > 0.05). Payer et al. [28] performed clinical measurements at 1, 2, 4 and 12 weeks after surgery and found no significant differences in flap closure, pain, swelling, pus and implant stability of the operation site between the two treatment groups at any time over the post-operative observation period. The clinical diagnosis of postoperative surgery-associated morbidities was evaluated by Durand et al. [29] after 1, 3 and 16 weeks and 1 year. Postoperative swelling was measured using a form graded as follows: 0, no swelling; 1, mild swelling; 2, moderate swelling; and 3, severe swelling. Bruising, suppuration and wound dehiscence were evaluated dichotomously. The authors were contacted for the missing information about swelling and bruising in intervention and placebo groups, and they provided all data requested. Regarding suppuration, two participants in the AB group had suppuration at the one-week examination and were asked to rinse with 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate twice daily for two weeks but no ABs were used. No more suppuration was reported at the three-week follow-up. There were no significant differences in postoperative morbidities between the intervention and placebo groups (p = 0.230).

In the study by Anitua et al. [26], patient records of smoking habits showed that 10 patients in the AB and 8 patients in the placebo group were smokers. However, the smoking habits variable was not associated with a higher risk of postoperative infection. Fifty percent of studies did not report on complications, and the other 50% reported no significant statistical differences between groups for all types of measured complications (swelling, bruising, wound dehiscence, pain and suppuration) [25,26,27,28,29,33,34,35,36,37].

No AB-related adverse events were reported in three studies [26,31,32]. In the study by Durand et al. [29], no definition of adverse events was given. Only one participant in the placebo group reported adverse events (diarrhoea) two days after implant placement. In the study by Esposito et al. (2008), one week after implant placement, one adverse event occurred in the placebo group (itching for one day) and one in the AB group (diarrhoea and somnolence); however, no significant difference was reported (p = 0.1), and no major complications linked to the use of ABs occurred. Seven studies did not report on AB-related adverse events [25,27,28,33,34,35,37].

In the study by Payer et al. [28], the patient self-reported outcomes used a visual analogue scale (VAS) (0–10) every day for the first two postoperative weeks. Results from mean and median VAS scores of bleedings, swelling and pain revealed no significant difference at day 14 (p > 0.05), but the mean VAS scores decreased over time (p < 0.001). The patients of Tan et al. [27] self-reported outcomes at days 1, 7 and 14. There was no statistically significant difference among study AB groups for bleeding, swelling, pain and bruising, indicating no superiority for the prophylactic regimen (p > 0.05). All other studies did not report on this outcome [25,26,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Nolan’s [33] patients kept records of the number of paracetamol 500 mg tablets taken for one week, and a VAS question was used for reporting. Higher postoperative VAS scores were recorded by the placebo group after two days postoperatively, and the difference between groups was significant (p = 0.003 at first day and p < 0.001 after 7 days). Durand’s [29] patients were given daily diaries to evaluate their postoperative pain severity for 1 week postoperatively, using self-administered questionnaires (VAS score). The median VAS score was 2 in the control group and 0 in the AB group. The overall median pain severity observed in both groups during the first seven days after surgery was considered mild. However, the perceived pain intensity difference in participants taking the postoperative placebo was statistically significant on the fourth day at noon (p = 0.047) and at night (p = 0.036) and on the 5th day at night (p = 0.036), indicating that patients in the postoperative placebo group experienced significantly more pain. However, it is worth noting that their control group experienced a longer implant surgery duration and higher number of implants inserted compared to those in their AB group. Durand et al. [29] reported that the mean number of supplemental analgesics taken by the participants in each group was 1.5 ± 4.5 tablets, and for those in the placebo group, it was 1.0 ± 2.8 tablets at the 1-week follow-up, which was not significant.

Tan et al. [27] reported no significant difference in analgesic consumption groups. Paracetamol three times a day for two days after surgery was recommended by Payer et al. [28]. The percentage of patients who took analgesics did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) between the two treatment groups. The other studies did not report on this outcome [25,26,31,32,34,35,36,37].

The postoperative use of rescue ABs was reported by Kashani et al. [34]. Seven patients with 10 implants required postoperative AB treatment. Of 10 infected implants, seven healed after 10 days of ABs, whereas three implants were lost and subsequently reoperated. Six of the seven patients were in the NOAB group. Esposito et al. [36] reported that two AB-group and one placebo-group patients required postoperative ABs. All other studies did not report on this outcome [25,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,35,37].

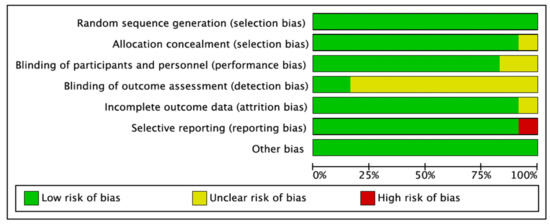

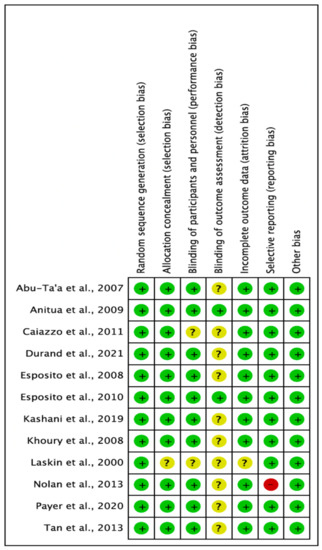

3.2.6. Risk of Bias

This was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias (RoB) assessment tool [39]. The risk of bias summary is illustrated in Figure 7 and Figure 8. Eleven studies had a low RoB [25,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36], while one study presented a high RoB [37].

Figure 7.

Risk of bias graph: review of authors’ judgments on each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. Green denotes features at a low risk of bias, red denotes a feature at a high risk of bias, and yellow denotes features at an unclear risk of bias.

Figure 8.

Each risk of bias item for each included study. Green denotes features at a low risk of bias, red denotes a feature at a high risk of bias, and yellow denotes features at an unclear risk of bias (Abu-Ta’a [32], Anitua [26], Caiazzo [25], Durand [29], Esposito [36], Esposito [31], Kashani [34], Khoury [35], Laskin [37], Nolan [33], Payer [28], Tan [27]).

3.2.7. Number Needed to Treat Calculation

To Prevent Implant Failure Due to Infection, by Implant

NNT: 32. This is >5, which indicates that the intervention (use of prophylactic ABs) is not effective in preventing infection [22,23].

To Prevent Implant Failure Due to Infection by Patient

NNT: 14. The number of patients needed to treat (NNT) with antimicrobial prophylaxis to prevent one implant failure due to infection in previous studies was indicated as from 25 to 48 [40,41]. This review found that 14 patients undergoing DIP surgery need to receive ABs in order to prevent one implant failure due to infection occurring. The NNT is more than 5, which indicates that the intervention (use of prophylactic ABs) is not effective in preventing infection [22,23].

To Prevent Complications Due to Infection

NNT: 2523. The NNT is more than 5, which indicates that the intervention (use of prophylactic ABs) is not effective in preventing complications caused by infection [22,23].

To Cause Adverse Events

NNH: 528. The NNH is not a negative figure but more than 5, which means that the possible harm caused by the use of ABs exists, but it is very small and does not negate AB use when required [22,23].

4. Discussion

The major limitation of this systematic review is the small number of well-designed randomised controlled trials on the efficacy of ABs for DIP surgery identified. This may in part be due to this unfunded study not having the resources for wider searching or obtaining translations of non-English language publications. However, the RCTs that were included covered a range of countries and different healthcare systems and thus reflect a wide range of practices. The trials were well documented RCTs rated with a low RoB. This review provided evidence broadly supporting the administration of prophylactic ABs in those undergoing implant surgeries. When implant failure due to infection was analysed by implants, it was noted that the implants placed in the AB group were 67% more likely to survive than those when receiving placebo, indicating that implants placed in the placebo group were three times more likely to fail. In the studies, 3496 implants were placed in both groups; 23 failed in the AB groups and 68 in the placebo group. The effectiveness analysis of implant failure by implant suggests an antibiotic NNT of 32 to prevent one implant loss from occurring. This broadly agrees with the recommendations of the fourth European Association for Osseointegration Consensus 2015 [42].

When implant failure due to infection was analysed by patients, statistically beneficial results were found for the administration of ABs compared to those with controls. However, for the postoperative complications, no evidence of AB use benefit was found. Differences in clinical efficacy of Abs based on postoperative complications did not demonstrate significance due to the variability and small sample sizes of included studies. The most suggested AB was amoxicillin 2 g, but there is insufficient evidence to recommend this specific dosage. The number of adverse events occurring in those receiving ABs was not significantly different from that in those who received no ABs, confirming that ABs are safe to use when indicated. From 12 included trials, 6 reported a significant difference between ABs and placebo [29,31,33,34,35,37]. In contrast, the remaining studies showed no significant benefit [25,26,27,28,32,36]. Nolan et al. [33] reported that the number of implants placed appeared to significantly affect the osseointegration of DIPs and that when more implants were placed, the surgery duration was longer.

A different implant system was used in all trials, and no statistically significant differences were reported for the success or failure of osseointegration. Most studies implemented a variety of single and combined additional therapies with anti-inflammatory and pain-relief medications postoperatively to manage postoperative pain following DIP surgery. The Esposito et al. [31] study found a correlation between immediate post-extractive implants and the number of failed implants and concluded that patients who received immediate post-extractive implants were more likely to fail compared with patients receiving delayed implants. The study of Nolan et al. [33] reported that longer procedures showed a modest correlation with post-operative pain (on VAS scores), interference of daily activities and the number of analgesics used. Only one study found smoking to have affected the outcome results, and heavy smoking was associated with an increased risk of implant failure. This does not rule out moderate smoking as a risk factor for failed implants. Abu Ta’a et al. [32] reported on parafunctions, finding they would increase the risk of implant failure. In this review, only one study addressed immediate post-extractive implants as a potential risk of failed implants. In most of the studies, the implant surgery was performed by oral and maxillofacial surgeons for placement of the implant. In one study by Nolan et al. [33], the implant surgical procedure was performed by two postgraduate students supervised by an experienced periodontist; however, the results of the study appear to be unaffected. Regarding the surgical protocol of one-stage and two-stage surgeries, none of the studies found significant factors associated with one- or two-stage surgeries with the failure or success of an implant. It is worth noting that emerging technologies, such as laser, photo-disinfection and airflow, etc., will contribute to infection risk reduction [new]. All studies implemented additional therapies with chlorhexidine oral rinse pre- and postoperatively or administered analgesic before and after implant surgery, which could have affected the results of the review. The studies also reported maintaining a high standard of infection control in surgical procedures. The results from this review were compared to previous studies (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of findings with previous systematic reviews.

5. Limitations

The limitation of this systematic review is the small number of well-designed randomised controlled trials on the efficacy of ABs for DIP surgery available for review to date.

In addition, due to the small number of studies included, the funnel plot was not used. Thus, it was not possible to objectively evaluate the publication bias in these meta-analyses. All RCTs that were included in these meta-analyses were conducted in various countries with different healthcare systems. Therefore, drawing definitive conclusions about the effects of ABs is a problem.

The study search was completed in January 2022; it is planned that a new systematic review will be conducted to cover studies published in 2022 and 2023.

6. Conclusions

Antibiotic use was reported to be statistically significant in preventing infection (p < 001), but not significant in the prevention of complications (p = 0.96), and the NNT was larger than 5 (14 and 2523 respectively), which indicates that the intervention is not sufficiently effective to justify its routine use. The occurrence of side effects was not significant (p = 0.63), and the NNH was 528, indicating that the possible harm is very small and does not negate the AB use when required. Given that the studies only evaluated healthy men and women, the study can be applied to systemically and periodontally healthy individual undergoing straightforward oral implant surgery placement under sterile conditions. It is important that future studies are rigorously designed and adequately powered to better inform future practice around the secondary outcomes and for complex patients with co-morbidities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M. and E.T.; methodology, H.M. and E.T.; software, E.T.; validation, H.M., E.T. and P.A.B.; formal analysis, H.M., E.T. and P.A.B.; investigation, E.T.; resources, E.T.; data curation, E.T. and H.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M., E.T. and P.A.B.; writing—review and editing, H.M., E.T. and P.A.B.; visualization, H.M., E.T. and P.A.B.; supervision, H.M. and P.A.B.; project administration, H.M.; funding acquisition, N/A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

E.T. acknowledges the generous support for her degree fees received from the Coats Foundation Trust (FfWG), and the British Federation of Women Graduates (BFWG) Charitable Foundation. The BFWG is affiliated to the International Federation of University Women. The authors express grateful thanks for the support, reviews, and commentaries provided by: Edward Newton: General and Cosmetic Dentist. GDC No: 271825. George Cherukara: Senior Clinical Lecturer, University of Dundee, Honorary Consultant in Restorative Dentistry, NHS Tayside, Programme Lead MDSc in Prosthodontics. Tom Thayer: Consultant and Hon Lecturer in Oral Surgery, Liverpool University Dental School and Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Misch, C. Dental Implant Prosthetics, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Health Sciences: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.K. Practical Procedures in Implant Dentistry, 2nd ed.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, M.; Singh, Y.; Arora, P.; Arora, V.; Jain, K. Implant biomaterials: A comprehensive review. World J. Clin. Cases 2015, 3, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, M.; Celik, E.; Mete, S.; Serin, F. Computational Intelligence and Soft Computing Applications in Healthcare Management Science; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; p. 322. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, B.; Ladha, K.; Lalit, A.; Naik, B.D. Occlusal Concepts in Full Mouth Rehabilitation: An Overview. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2014, 14, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitzmann, N.; Margolin, M.D.; Filippi, A.; Weiger, R.; Krastl, G. Patient assessment and diagnosis in implant treatment. Aust. Dent. J. 2008, 53, S3–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, M.R. Biologic and mechanical stability of single-tooth implants: 4- to 7-year follow-up. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2001, 3, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, L.; Sadet, P.; Grossmann, Y. A Retrospective Evaluation of 1387 Single-Tooth Implants: A 6-Year Follow-up. J. Periodontol. 2006, 77, 2080–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buser, D.; Dmd, S.F.M.J.; Wittneben, J.; Brägger, U.; Dmd, C.A.R.; Salvi, G.E. 10-Year Survival and Success Rates of 511 Titanium Implants with a Sandblasted and Acid-Etched Surface: A Retrospective Study in 303 Partially Edentulous Patients. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2012, 14, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappuis, V.; Buser, R.; Brägger, U.; Bornstein, M.M.; Salvi, G.E.; Buser, D. Long-Term Outcomes of Dental Implants with a Titanium Plasma-Sprayed Surface: A 20-Year Prospective Case Series Study in Partially Edentulous Patients. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2013, 15, 780–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenlechner, D.; Fürhauser, R.; Haas, R.; Watzek, G.; Mailath, G.; Pommer, B. Long-term implant success at the Academy for Oral Implantology: 8-year follow-up and risk factor analysis. J. Periodontal Implant. Sci. 2014, 44, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, M.; Schmenger, K.; Neumann, K.; Weigl, P.; Moser, W.; Nentwig, G. Long-Term Evaluation of ANKYLOS® Dental Implants, Part I: 20-Year Life Table Analysis of a Longitudinal Study of More than 12,500 Implants. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2013, 17, e275–e286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.A.; Von Fraunhofer, J.A. Success or failure of dental implants? A literature review with treatment considerations. Gen. Dent. 2005, 53, 423. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, L.; Schwartz-Arad, D. The Effect of Cigarette Smoking on Dental Implants and Related Surgery. Implant. Dent. 2005, 14, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenezer, V.; Balakrishnan, K.; Asir, R.D.; Sragunar, B. Immediate placement of endosseous implants into the extraction sockets. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2015, 7, S234–S237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surapaneni, H.; Yalamanchili, P.; Basha, M.; Potluri, S.; Elisetti, N.; Kumar, M.K. Antibiotics in dental implants: A review of literature. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2016, 8, S28–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, R.; Misch, C.E. Avoiding Complications in Oral Implantology; Elsevier: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hupp, J.; Ferneini, E. Head, Neck, and Orofacial Infections, 1st ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Papaspyridakos, P.; Chen, C.-J.; Singh, M.; Weber, H.-P.; Gallucci, G. Success Criteria in Implant Dentistry: A systematic review. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 91, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The UK Faculty of Public Health. Numbers Needed to Treat (NNTs)—Calculation, Interpretation, Advantages and Disadvantages. Available online: https://www.healthknowledge.org.uk/public-health-textbook/research-methods/1a-epidemiology/nnts (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), UK. Number Needed to Treat. Available online: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/ebm-tools/number-needed-to-treat-nnt (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Amir-Behghadami, M.; Janati, A. Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) design as a framework to formulate eligibility criteria in systematic reviews. Emerg. Med. J. 2020, 37, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiazzo, A.; Casavecchia, P.; Barone, A.; Brugnami, F. A Pilot Study to Determine the Effectiveness of Different Amoxicillin Regimens in Implant Surgery. J. Oral Implant. 2011, 37, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; Aguirre, J.J.; Gorosabel, A.; Barrio, P.; Errazquin, J.M.; Román, P.; Pla, R.; Carrete, J.; de Petro, J.; Orive, G. A mul-ticentre placebo-controlled randomised clinical trial of antibiotic prophylaxis for placement of single dental implants. Eur. J. Oral. Implantol. 2009, 2, 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.C.; Ong, M.; Han, J.; Mattheos, N.; Pjetursson, B.E.; Tsai, A.Y.-M.; Sanz, I.; Wong, M.C.; Lang, N.P.; on Behalf of the ITI Antibiotic Study Group. Effect of systemic antibiotics on clinical and patient-reported outcomes of implant therapy—A multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2013, 25, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payer, M.; Tan, W.C.; Han, J.; Ivanovski, S.; Mattheos, N.; Pjetursson, B.E.; Zhuang, L.; Fokas, G.; Wong, M.C.M.; Acham, S.; et al. The effect of systemic antibiotics on clinical and patient-reported outcome measures of oral implant therapy with simultaneous guided bone regeneration. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2020, 31, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, R.; Kersheh, I.; Marcotte, S.; Boudrias, P.; Schmittbuhl, M.; Cresson, T.; Rei, N.; Rompré, P.H.; Voyer, R. Do postoperative antibiotics influence one-year peri-implant crestal bone remodelling and morbidity? A double-blinded randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2021, 32, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Egger, M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: Guidelines on choice of axis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001, 54, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Cannizzaro, G.; Bozzoli, P.; Checchi, L.; Ferri, V.; Landriani, S.; Leone, M.; Todisco, M.; Torchio, C.; Testori, T.; et al. Effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotics at placement of dental implants: A pragmatic multicentre placebo-controlled randomised clinical trial. Eur. J. Oral Implant. 2010, 3, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Ta’A, M.; Quirynen, M.; Teughels, W.; Van Steenberghe, D. Asepsis during periodontal surgery involving oral implants and the usefulness of peri-operative antibiotics: A prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2007, 35, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, R.; Kemmoona, M.; Polyzois, I.; Claffey, N. The influence of prophylactic antibiotic administration on post-operative morbidity in dental implant surgery. A prospective double blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2013, 25, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, H.; Hilon, J.; Rasoul, M.H.; Friberg, B. Influence of a single preoperative dose of antibiotics on the early implant failure rate. A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, S.B.; Thomas, L.; Walters, J.D.; Sheridan, J.F.; Leblebicioglu, B. Early Wound Healing Following One-Stage Dental Implant Placement With and without Antibiotic Prophylaxis: A Pilot Study. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 1904–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Grusovin, M.G.; Coulthard, P.; Oliver, R.; Worthington, H.V. The efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis at placement of dental implants: A Cochrane systematic review of randomised controlled clinical trials. Eur. J. Oral Implant. 2008, 1, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Laskin, D.M.; Dent, C.D.; Morris, H.F.; Ochi, S.; Olson, J.W. The Influence of Preoperative Antibiotics on Success of Endosseous Implants at 36 Months. Ann. Periodontol. 2000, 5, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Ciliska, D.; Dobbins, M.; Micucci, S. A Process for Systematically Reviewing the Literature: Providing the Research Evidence for Public Health Nursing Interventions. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2004, 1, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Sterne, J.A.C. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 6.3; Higgins, J., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.M., Welch, V., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ata-Ali, J.; Ata-Ali, F. Do antibiotics decrease implant failure and postoperative infections? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, M.; Grusovin, M.G.; Worthington, H.V. Interventions for replacing missing teeth: Antibiotics at dental implant placement to prevent complications. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD004152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Klinge, B.; Quirynen, M. The 4th EAO Consensus Conference 11–14 February 2015, Pfäffikon, Schwyz, Switzerland. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2015, 26, iii–iv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canullo, L.; Troiano, G.; Sbricoli, L.; Guazzo, R.; Laino, L.; Caiazzo, A.; Pesce, P. The Use of Antibiotics in Implant Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis on Early Implant Failure. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2020, 35, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Rai, A.; Singh, A.; Taneja, S. Efficacy of preoperative antibiotics in prevention of dental implant failure: A Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 24, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, R.S.; Chambrone, L.; Khouly, I. Prophylactic antibiotic regimens in dental implant failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, e61–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).