Molecular Triggers of Yeast Pathogenicity in the Yeast–Host Interactions

Abstract

1. Introduction

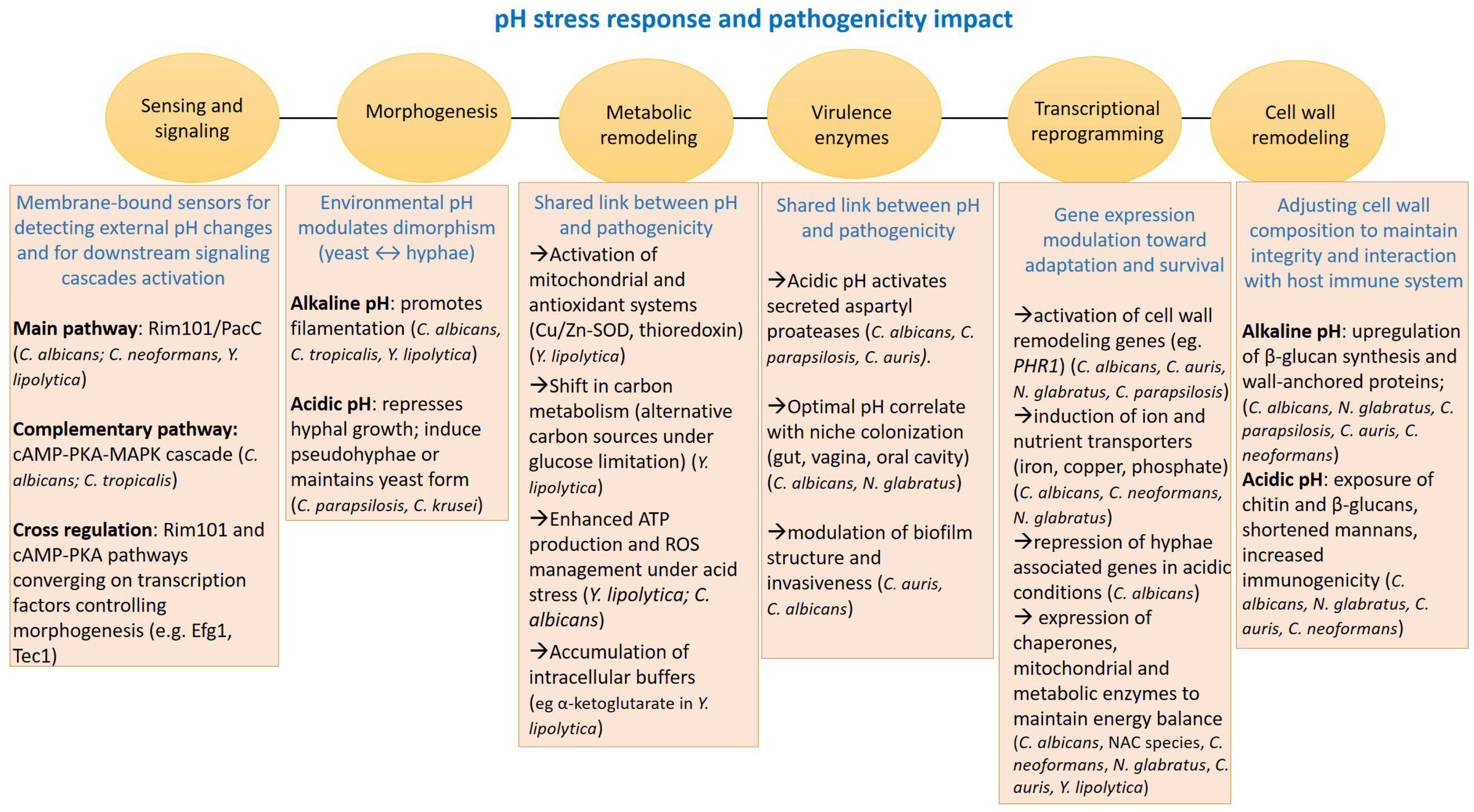

2. Adaptation to pH Shift

2.1. Alkaline pH

2.2. Acidic pH

2.3. pH Homeostasis

3. CO2 Sensing and Response to Oxygen Limitation

3.1. CO2 Exposure

3.2. Oxygen Limitation. Hypoxia

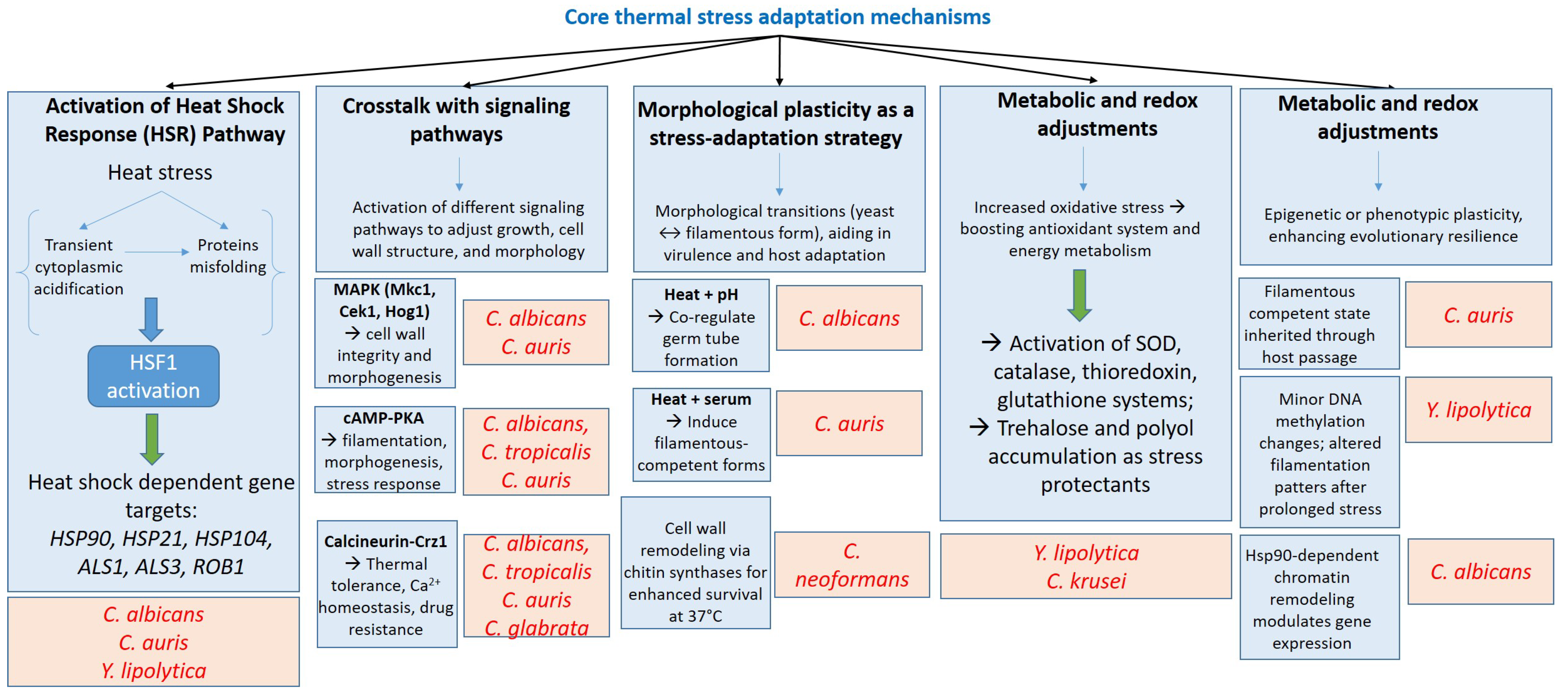

4. Thermotolerance Mechanisms

5. Metabolic Adjustment to Nutrient Conditions

5.1. Carbon Substrates

5.2. Nitrogen Substrate

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alves, R.; Barata-Antunes, C.; Casal, M.; Brown, A.J.P.; Van Dijck, P.; Paiva, S. Adapting to Survive: How Candida Overcomes Host-Imposed Constraints during Human Colonization. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, D. Candida albicans, Plasticity and Pathogenesis. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 41, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, A.; Honore, P.M.; Puerta-Alcalde, P.; Garcia-Vidal, C.; Pagotto, A.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C.; Verweij, P.E. Invasive Candidiasis: Current Clinical Challenges and Unmet Needs in Adult Populations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, Y.; Chew, S.Y.; Than, L.T.L. Candida glabrata: Pathogenicity and Resistance Mechanisms for Adaptation and Survival. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.; Negri, M.; Henriques, M.; Oliveira, R.; Williams, D.W.; Azeredo, J. Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis: Biology, Epidemiology, Pathogenicity and Antifungal Resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Shu, T.; Mao, Y.-S.; Gao, X.-D. Characterization of the Promoter, Downstream Target Genes and Recognition DNA Sequence of Mhy1, a Key Filamentation-Promoting Transcription Factor in the Dimorphic Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Curr. Genet. 2020, 66, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pristov, K.E.; Ghannoum, M.A. Resistance of Candida to Azoles and Echinocandins Worldwide. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deorukhkar, S.C.; Saini, S.; Mathew, S. Virulence Factors Contributing to Pathogenicity of Candida tropicalis and Its Antifungal Susceptibility Profile. Int. J. Microbiol. 2014, 2014, 456878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupančič, J.; Babič, M.N.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. High Incidence of an Emerging Opportunistic Pathogen Candida parapsilosis in Water-Related Domestic Environments. In Fungal Infection; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rupert, C.B.; Rusche, L.N. The Pathogenic Yeast Candida parapsilosis Forms Pseudohyphae through Different Signaling Pathways Depending on the Available Carbon Source. mSphere 2022, 7, e00029-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gaviria, M.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Current Aspects in the Biology, Pathogeny, and Treatment of Candida krusei, a Neglected Fungal Pathogen. IDR 2020, 13, 1673–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.V.; Holt, A.M.; Nett, J.E. Mechanisms of Pathogenicity for the Emerging Fungus Candida auris. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, 1011843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allert, S.; Schulz, D.; Kämmer, P.; Großmann, P.; Wolf, T.; Schäuble, S.; Hube, B. From Environmental Adaptation to Host Survival: Attributes That Mediate Pathogenicity of Candida auris. Virulence 2022, 13, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.-K.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. What Makes Yarrowia lipolytica Well Suited for Industry? Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbes, S.; Amouri, I.; Trabelsi, H.; Neji, S.; Sellami, H.; Rahmouni, F.; Ayadi, A. Analysis of Virulence Factors and in Vivo Biofilm-Forming Capacity of Yarrowia lipolytica Isolated from Patients with Fungemia. Med. Mycol. 2017, 55, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieniuk, B.; Fabiszewska, A. Yarrowia lipolytica: A Beneficious Yeast in Biotechnology as a Rare Opportunistic Fungal Pathogen: A Minireview. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliehe, M.; Ntoi, M.A.; Lahiri, S.; Folorunso, O.S.; Ogundeji, A.O.; Pohl, C.H.; Sebolai, O.M. Environmental Factors That Contribute to the Maintenance of Cryptococcus neoformans Pathogenesis. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogaran, Y.; Ramasamy, P. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii Species in Urban Tropics: A Comprehensive Review of Pathogenicity and Resistance. Microbe 2025, 8, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwell, K.J.; Boysen, J.H.; Xu, W.; Mitchell, A.P. Relationship of DFG16 to the Rim101p pH Response Pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Wilson, R.B.; Mitchell, A.P. RIM101-Dependent and-Independent Pathways Govern pH Responses in Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnaud, C.; García-Oliver, E.; Wang, Y.; Maubon, D.; Bailly, S.; Despinasse, Q.; Cornet, M. The Rim Pathway Mediates Antifungal Tolerance in Candida albicans through Newly Identified Rim101 Transcriptional Targets, Including Hsp90 and Ipt1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensen, E.S.; Martin, S.J.; Li, M.; Berman, J.; Davis, D.A. Transcriptional Profiling in Candida albicans Reveals New Adaptive Responses to Extracellular pH and Functions for Rim101p. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1335–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Albrecht-Eckardt, D.; Brunke, S.; Hube, B.; Hünniger, K.; Kurzai, O. A Core Filamentation Response Network in Candida albicans Is Restricted to Eight Genes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 58613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollomon, J.M.; Grahl, N.; Willger, S.D.; Koeppen, K.; Hogan, D.A. Global Role of Cyclic AMP Signaling in pH-Dependent Responses in Candida albicans. mSphere 2016, 1, e00283-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazier, V.E. EFG1, Everyone’s Favorite Gene in Candida albicans: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 855229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, S.; Hamideh, M.; Weinstock, A.; Qasim, M.N.; Hazbun, T.R.; Sellam, A.; Thangamani, S. Transcriptional Control of Hyphal Morphogenesis in Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res. 2020, 20, foaa005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias-Paz, I.U.; Pérez-Hernández, S.; Tavera-Tapia, A.; Luna-Arias, J.P.; Guerra-Cárdenas, J.E.; Reyna-Beltrán, E. Candida albicans the Main Opportunistic Pathogenic Fungus in Humans. Rev. Argent. De Microbiol. 2023, 55, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, H.; Laing, J.; Paterson, L.; Walker, A.W.; Gow, N.A.; Johnson, E.M.; Brown, A.J. The Environmental Stress Sensitivities of Pathogenic Candida Species, Including Candida auris, and Implications for Their Spread in the Hospital Setting. Med. Mycol. 2020, 58, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.; Araújo, D.; Ribeiro, E.; Henriques, M.; Silva, S. Candida albicans Adaptation on Simulated Human Body Fluids under Different pH. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Gonçalves, B.; Vilas Boas, D.; Oliveira, H.; Henriques, M.; Azeredo, J.; Silva, S.Â. Candida tropicalis Biofilm and Human Epithelium Invasion Is Highly Influenced by Environmental pH. FEMS Pathog. Dis. 2016, 74, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idnurm, A.; Walton, F.J.; Floyd, A.; Reedy, J.L.; Heitman, J. Identification of ENA1 as a Virulence Gene of the Human Pathogenic Fungus Cryptococcus neoformans through Signature-Tagged Insertional Mutagenesis. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.H.; Sephton-Clark, P.; Tenor, J.L.; Toffaletti, D.L.; Giamberardino, C.; Haverkamp, M.; Perfect, J.R. Gene Expression of Diverse Cryptococcus Isolates during Infection of the Human Central Nervous System. mBio 2021, 12, e0231321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekova, V.Y.; Kovalyov, L.I.; Kovalyova, M.A.; Gessler, N.N.; Danilova, M.A.; Isakova, E.P.; Deryabina, Y.I. Proteomics Readjustment of the Yarrowia lipolytica Yeast in Response to Increased Temperature and Alkaline Stress. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epova, E.; Guseva, M.; Kovalyov, L.; Isakova, E.; Deryabina, Y.; Belyakova, A.; Zylkova, M.; Shevelev, A.; Epova, E.; Guseva, M.; et al. Identification of Proteins Involved in pH Adaptation in Extremophile Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. In Proteomic Applications in Biology; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-953-307-613-3. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Campo, F.M.; Domínguez, A. Factors Affecting the Morphogenetic Switch in Yarrowia lipolytica. Curr. Microbiol. 2001, 43, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, T.; He, X.-Y.; Chen, J.-W.; Mao, Y.-S.; Gao, X.-D. The pH-Responsive Transcription Factors YlRim101 and Mhy1 Regulate Alkaline pH-Induced Filamentation in the Dimorphic Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. mSphere 2021, 6, e00179-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mio, T.; Yamada-Okabe, T.; Yabe, T.; Nakajima, T.; Arisawa, M.; Yamada-Okabe, H. Isolation of the Candida albicans Homologs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae KRE6 and SKN1: Expression and Physiological Function. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 2363–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, E.; Yamaguchi, M.; Ono, M.; Kawabata, S. In Vitro Acid Resistance of Pathogenic Candida Species in Simulated Gastric Fluid. Gastro Hep Adv. 2025, 4, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.K.; Pandey, A.; Sahoo, D. Biotechnological Potential of Yeasts in Functional Food Industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 83, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, G.; Li, S.; Bing, J.; Liu, L.; Tao, L. The Rfg1 and Bcr1 Transcription Factors Regulate Acidic pH–Induced Filamentous Growth in Candida albicans. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01789-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chen, G.; Wu, L.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Chen, C. Coordinated Regulation of pH Alkalinization by Two Transcription Factors Promotes Fungal Commensalism and Pathogenicity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrington, S.L.; Sorsby, E.; Mahtey, N.; Kumwenda, P.; Lenardon, M.D.; Brown, I.; Hall, R.A. Adaptation of Candida albicans to Environmental pH Induces Cell Wall Remodelling and Enhances Innate Immune Recognition. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, 1006403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangl, I.; Beyer, R.; Pap, I.-J.; Strauss, J.; Aspöck, C.; Willinger, B.; Schüller, C. Human Pathogenic Candida Species Respond Distinctively to Lactic Acid Stress. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhruddin, K.S.; Perera Samaranayake, L.; Egusa, H.; Ngo, H.C.; Pesee, S. Profuse Diversity and Acidogenicity of the Candida-Biome of Deep Carious Lesions of Severe Early Childhood Caries (S-ECC). J. Oral Microbiol. 2021, 13, 1964277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, R. Exploring Small Heat Shock Proteins (sHSPs) for Targeting Drug Resistance in Candida albicans and Other Pathogenic Fungi. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 15, 6067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bras, G.; Satala, D.; Juszczak, M.; Kulig, K.; Wronowska, E.; Bednarek, A.; Karkowska-Kuleta, J. Secreted Aspartic Proteinases: Key Factors in Candida Infections and Host-Pathogen Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naglik, J.; Albrecht, A.; Bader, O.; Hube, B. Candida albicans Proteinases and Host/Pathogen Interactions. Cell. Microbiol. 2004, 6, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, G.C.; Barbosa, P.F.; Ramos, L.S.; Branquinha, M.H.; Santos, A.L. Impact of pH, Temperature and Exogenous Proteins on Aspartic Peptidase Secretion in Candida auris and the Candida haemulonii Species Complex. Pathogens 2025, 14, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuzbashev, T.V.; Yuzbasheva, E.Y.; Sobolevskaya, T.I.; Laptev, I.A.; Vybornaya, T.V.; Larina, A.S.; Matsui, K.; Fukui, K.; Sineoky, S.P. Production of Succinic Acid at Low pH by a Recombinant Strain of the Aerobic Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 107, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aréchiga-Carvajal, E.T.; Ruiz-Herrera, J. The RIM101/pacC Homologue from the Basidiomycete Ustilago Maydis Is Functional in Multiple pH-Sensitive Phenomena. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Herrera, J.; Sentandreu, R. Different Effectors of Dimorphism in Yarrowia lipolytica. Arch. Microbiol. 2002, 178, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.B.; Yang, H.L.; Yan, R.M.; Zhu, D. Influence of Environmental and Nutritional Conditions on Yeast–Mycelial Dimorphic Transition in Trichosporon cutaneum. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2017, 31, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, H.S.; Hayek, S.R.; Frye, J.E.; Abeyta, E.L.; Bernardo, S.M.; Parra, K.J.; Lee, S.A. Candida albicans Pma1p Contributes to Growth, pH Homeostasis, and Hyphal Formation. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, M.; Battu, A.; Kaur, R. Aspartyl Proteases in Candida glabrata Are Required for Suppression of the Host Innate Immune Response. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 6410–6433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairwa, G.; Kaur, R. A Novel Role for a Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored Aspartyl Protease, CgYps1, in the Regulation of pH Homeostasis in Candida glabrata. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 79, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vylkova, S.; Carman, A.J.; Danhof, H.A.; Collette, J.R.; Zhou, H.; Lorenz, M.C. The Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans Autoinduces Hyphal Morphogenesis by Raising Extracellular pH. mBio 2011, 2, e00055-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danhof, H.A.; Lorenz, M.C. The Candida albicans ATO Gene Family Promotes Neutralization of the Macrophage Phagolysosome. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 4416–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, H.; Moriguchi, D.; Matsushika, A. Characterization of Low pH and Inhibitor Tolerance Capacity of Candida krusei Strains. Fermentation 2025, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, H.; Matsushika, A. Transcription Analysis of the Acid Tolerance Mechanism of Pichia Kudriavzevii NBRC1279 and NBRC1664. Fermentation 2023, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatebayashi, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Tomida, T.; Nishimura, A.; Takayama, T.; Oyama, M.; Kozuka-Hata, H.; Adachi-Akahane, S.; Tokunaga, Y.; Saito, H. Osmostress Enhances Activating Phosphorylation of Hog1 MAP Kinase by Mono-phosphorylated Pbs2 MAP2K. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e103444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.L.; Wilson, D.; Hube, B. Candida albicans Pathogenicity Mechanisms. Virulence 2013, 4, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarathna, D.H.; Lionakis, M.S.; Lizak, M.J.; Munasinghe, J.; Nickerson, K.W.; Roberts, D.D. Urea Amidolyase (DUR1, 2) Contributes to Virulence and Kidney Pathogenesis of Candida albicans. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 48475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celińska, E. “Fight-Flight-or-Freeze”—How Yarrowia lipolytica Responds to Stress at Molecular Level? Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 3369–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Wan, H.; Chen, H.; Fang, F.; Liu, S.; Zhou, J. Proteomic Analysis of the Response of α-Ketoglutarate-Producer Yarrowia lipolytica WSH-Z06 to Environmental pH Stimuli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 8829–8841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Su, C.; Solis, N.V.; Filler, S.G.; Liu, H. Synergistic Regulation of Hyphal Elongation by Hypoxia, CO2, and Nutrient Conditions Controls the Virulence of Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, R.A.; Sordi, L.; MacCallum, D.M.; Topal, H.; Eaton, R.; Bloor, J.W.; Mühlschlegel, F.A. CO2 Acts as a Signalling Molecule in Populations of the Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, 1001193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostál, J.; Blaha, J.; Hadravová, R.; Hubálek, M.; Heidingsfeld, O.; Pichová, I. Cellular Localization of Carbonic Anhydrase Nce103p in Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentland, D.R.; Davis, J.; Mühlschlegel, F.A.; Gourlay, C.W. CO2 Enhances the Formation, Nutrient Scavenging and Drug Resistance Properties of C. Albicans Biofilms. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottier, F.; Leewattanapasuk, W.; Kemp, L.R.; Murphy, M.; Supuran, C.T.; Kurzai, O.; Mühlschlegel, F.A. Carbonic Anhydrase Regulation and CO2 Sensing in the Fungal Pathogen Candida glabrata Involves a Novel Rca1p Ortholog. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelar, G.M.; Pradhan, A.; Ma, Q.; Hickey, E.; Leaves, I.; Liddle, C.; Rodriguez Rondon, A.V.; Kaune, A.-K.; Shaw, S.; Maufrais, C.; et al. A CO2 Sensing Module Modulates β-1,3-Glucan Exposure in Candida albicans. mBio 2024, 15, e01898-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klengel, T.; Liang, W.-J.; Chaloupka, J.; Ruoff, C.; Schröppel, K.; Naglik, J.R.; Eckert, S.E.; Mogensen, E.G.; Haynes, K.; Tuite, M.F.; et al. Fungal Adenylyl Cyclase Integrates CO2 Sensing with cAMP Signaling and Virulence. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 2021–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan-Canh, T.; Penninger, P.; Seiser, S.; Khunweeraphong, N.; Moser, D.; Bitencourt, T.; Kuchler, K. Carbon Dioxide Controls Fungal Fitness and Skin Tropism of Candida auris. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-H.; Wu, H.; Wang, R.-R.; Wang, Q.; Shu, T.; Gao, X.-D. The TORC1–Sch9–Rim15 Signaling Pathway Represses Yeast-to-Hypha Transition in Response to Glycerol Availability in the Oleaginous Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Mol. Microbiol. 2017, 104, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellam, A.; Hoog, M.; Tebbji, F.; Beaurepaire, C.; Whiteway, M.; Nantel, A. Modeling the Transcriptional Regulatory Network That Controls the Early Hypoxic Response in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 2014, 13, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, M.; Burgain, A.; Tebbji, F.; Sellam, A. Transcriptional Control of Hypoxic Hyphal Growth in the Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 11, 770478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Synnott, J.M.; Guida, A.; Mulhern-Haughey, S.; Higgins, D.G.; Butler, G. Regulation of the Hypoxic Response in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 2010, 9, 1734–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgain, A.; Tebbji, F.; Khemiri, I.; Sellam, A. Metabolic Reprogramming in the Opportunistic Yeast Candida albicans in Response to Hypoxia. mSphere 2020, 5, e00913-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerner, C.; Vellanki, S.; Strauch, J.L.; Cramer, R.A. Recent Advances in Understanding the Human Fungal Pathogen Hypoxia Response in Disease Progression. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 77, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Lee, Y.H. Hypoxia: A Double-Edged Sword during Fungal Pathogenesis? Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Avelar, G.M.; Bain, J.M.; Childers, D.S.; Larcombe, D.E.; Netea, M.G.; Shekhova, E.; Munro, C.A.; Brown, G.D.; Erwig, L.P.; et al. Hypoxia Promotes Immune Evasion by Triggering β-Glucan Masking on the Candida albicans Cell Surface via Mitochondrial and cAMP-Protein Kinase A Signaling. mBio 2018, 9, e01318-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, B.; Driesch, D.; Krüger, T.; Garbe, E.; Gerwien, F.; Kniemeyer, O.; Vylkova, S. Impaired Amino Acid Uptake Leads to Global Metabolic Imbalance of Candida albicans Biofilms. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Meena, R.C.; Kumar, N. Functional Analysis of Selected Deletion Mutants in Candida glabrata under Hypoxia. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlé, D.; Hegarty, B.; Bossard, P.; Ferré, P.; Foufelle, F. SREBP transcription factors: Master regulators of lipid homeostasis. Biochimie 2004, 86, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, B.G.M.; Pinto, A.P.; Passos, J.C.D.S.; Da Rocha, J.B.T.; Alberto-Silva, C.; Costa, M.S. Diphenyl Diselenide Suppresses Key Virulence Factors of Candida krusei, a Neglected Fungal Pathogen. Biofouling 2022, 38, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, B.L.; Stewart, E.V.; Burg, J.S.; Hughes, A.L.; Espenshade, P.J. Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein Is a Principal Regulator of Anaerobic Gene Expression in Fission Yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 2817–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Lin, X. A PAS Protein Directs Metabolic Reprogramming during Cryptococcal Adaptation to Hypoxia. mBio 2021, 12, e03602-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellou, S.; Makri, A.; Triantaphyllidou, I.-E.; Papanikolaou, S.; Aggelis, G. Morphological and Metabolic Shifts of Yarrowia lipolytica Induced by Alteration of the Dissolved Oxygen Concentration in the Growth Environment. Microbiology 2014, 160, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoumi, A.; Bideaux, C.; Guillouet, S.E.; Allouche, Y.; Molina-Jouve, C.; Fillaudeau, L.; Gorret, N. Influence of Oxygen Availability on the Metabolism and Morphology of Yarrowia lipolytica: Insights into the Impact of Glucose Levels on Dimorphism. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 7317–7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentel, M.; Piškur, J.; Neuvéglise, C.; Ryčovská, A.; Cellengová, G.; Kolarov, J. Triplicate Genes for Mitochondrial ADP/ATP Carriers in the Aerobic Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica Are Regulated Differentially in the Absence of Oxygen. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2005, 273, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Xin, C.; Li, M.J.; Song, Z. Response and Regulatory Mechanisms of Heat Resistance in Pathogenic Fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 5415–5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.D.; Farrer, R.A.; Tan, K.; Miao, Z.; Walker, L.A.; Cuomo, C.A.; Cowen, L.E. Hsf1 and Hsp90 Orchestrate Temperature-Dependent Global Transcriptional Remodelling and Chromatin Architecture in Candida albicans. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, H.; Shapiro, R.S.; Cowen, L.E. Cdc28 Provides a Molecular Link between Hsp90, Morphogenesis, and Cell Cycle Progression in Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Meara, T.R.; Cowen, L.E. H Sp90-dependent Regulatory Circuitry Controlling Temperature-dependent Fungal Development and Virulence. Cell. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jara, M.; Frias-De-Diego, A.; Petit, R.A.; Wang, Y.; Frias, M.; Lanzas, C. Genomic Dynamics of The Emergent Candida auris: Exploring Climate-Dependent Trends. In Open Forum Infectious Diseases; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2025; p. 441. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H.; Iyer, K.R.; Pardeshi, L.; Muñoz, J.F.; Robbins, N.; Cuomo, C.A.; Cowen, L.E. Genetic Analysis of Candida auris Implicates Hsp90 in Morphogenesis and Azole Tolerance and Cdr1 in Azole Resistance. mBio 2019, 10, e02529-18, Erratum in mBio 2019, 10, e00346-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacometti, R.; Kronberg, F.; Biondi, R.M.; Passeron, S. Catalytic Isoforms Tpk1 and Tpk2 of Candida albicans PKA Have Non-redundant Roles in Stress Response and Glycogen Storage. Yeast 2009, 26, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, R.S.; Uppuluri, P.; Zaas, A.K.; Collins, C.; Senn, H.; Perfect, J.R.; Cowen, L.E. Hsp90 Orchestrates Temperature-Dependent Candida albicans Morphogenesis via Ras1-PKA Signaling. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, N.; Cowen, L.E. Roles of Hsp90 in Candida albicans Morphogenesis and Virulence. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2023, 75, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. A Fungus among Us: The Emerging Opportunistic Pathogen Candida tropicalis and PKA Signaling. Virulence 2018, 9, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, S.G.; Shafiq, A.; Hakim, S.T.; Anjum, Y.; Kazm, S.U. Effect of Growth Media, pH and Temperature on Yeast to Hyphal Transition in Candida albicans. Open J. Med. Microbiol. 2013, 3, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, H.; Won, D.; Bahn, Y.S. Signaling Pathways Governing the Pathobiological Features and Antifungal Drug Resistance of Candida auris. mBio 2025, 16, e02475-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, K.T.; Lee, M.H.; Cheong, E.; Bahn, Y.S. Adenylyl Cyclase and Protein Kinase A Play Redundant and Distinct Roles in Growth, Differentiation, Antifungal Drug Resistance, and Pathogenicity of Candida auris. mBio 2021, 12, e0272921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Bing, J.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, T.; Du, H.; Huang, G. Filamentation in Candida auris, an Emerging Fungal Pathogen of Humans: Passage through the Mammalian Body Induces a Heritable Phenotypic Switch. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Konieczka, J.H.; Springer, D.J.; Bowen, S.E.; Zhang, J.; Silao, F.G.S.; Heitman, J. Convergent Evolution of Calcineurin Pathway Roles in Thermotolerance and Virulence in Candida glabrata. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2012, 2, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.J.; Chang, Y.L.; Chen, Y.L. Calcineurin Signaling: Lessons from Candida Species. FEMS Yeast Res. 2015, 15, fov016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-J.; Liu, D.-H.; Zhong, J.-J. Interesting Physiological Response of the Osmophilic Yeast Candida krusei to Heat Shock. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2005, 36, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, W.J.; Reedy, J.L.; Cramer, R.A., Jr.; Perfect, J.R.; Heitman, J. Harnessing Calcineurin as a Novel Anti-Infective Agent against Invasive Fungal Infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak-Szymendera, M.; Skupien-Rabian, B.; Jankowska, U.; Celińska, E. Hyperosmolarity Adversely Impacts Recombinant Protein Synthesis by Yarrowia lipolytica—Molecular Background Revealed by Quantitative Proteomics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekova, V.Y.; Dergacheva, D.I.; Isakova, E.P.; Gessler, N.N.; Tereshina, V.M.; Deryabina, Y.I. Soluble Sugar and Lipid Readjustments in the Yarrowia lipolytica Yeast at Various Temperatures and pH. Metabolites 2019, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Gu, Y.; Du, G.; Zhang, J.; Xu, P.; Li, J. Conferring Thermotolerant Phenotype to Wild-Type Yarrowia lipolytica Improves Cell Growth and Erythritol Production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 3117–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Chi, P.; Zou, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xu, S.; Bilal, M.; Fickers, P.; Cheng, H. Metabolic Engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica for Thermoresistance and Enhanced Erythritol Productivity. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 176, Correction in Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak-Szymendera, M.; Pryszcz, L.P.; Białas, W.; Celińska, E. Epigenetic Response of Yarrowia lipolytica to Stress: Tracking Methylation Level and Search for Methylation Patterns via Whole-Genome Sequencing. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pénicaud, C.; Landaud, S.; Jamme, F.; Talbot, P.; Bouix, M.; Ghorbal, S.; Fonseca, F. Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Yarrowia lipolytica to Dehydration Induced by Air-Drying and Freezing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, V.; Sexton, J.A.; Johnston, M. A Glucose Sensor in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 2006, 5, 1726–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, J.A.; Brown, V.; Johnston, M. Regulation of Sugar Transport and Metabolism by the Candida albicans Rgt1 Transcriptional Repressor. Yeast 2007, 24, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, J.C.; Bahn, Y.S.; Den Berg, B.; Heitman, J.; Xue, C. Nutrient and Stress Sensing in Pathogenic Yeasts. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.S.; Desa, M.N.M.; Sandai, D.; Chong, P.P.; Than, L.T.L. Growth, Biofilm Formation, Antifungal Susceptibility and Oxidative Stress Resistance of Candida glabrata Are Affected by Different Glucose Concentrations. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 40, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ende, M.; Wijnants, S.; Dijck, P. Sugar Sensing and Signaling in Candida albicans and Candida glabrata. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancedo, J.M. The Early Steps of Glucose Signalling in Yeast. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 673–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.B.; Wang, Y.; Baker, G.M.; Fahmy, H.; Jiang, L.; Xue, C. The Glucose Sensor-like Protein Hxs1 Is a High-Affinity Glucose Transporter and Required for Virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 64239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.S.; Betancourt-Quiroz, M.; Price, J.L.; Toffaletti, D.L.; Vora, H.; Hu, G.; Perfect, J.R. Cryptococcus neoformans Requires a Functional Glycolytic Pathway for Disease but Not Persistence in the Host. mBio 2011, 2, e00103-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronstad, J.; Saikia, S.; Nielson, E.D.; Kretschmer, M.; Jung, W.; Hu, G.; Attarian, R. Adaptation of Cryptococcus neoformans to Mammalian Hosts: Integrated Regulation of Metabolism and Virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 2012, 11, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabina, J.; Brown, V. Glucose Sensing Network in Candida albicans: A Sweet Spot for Fungal Morphogenesis. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buu, L.M.; Chen, Y.C. Impact of Glucose Levels on Expression of Hypha-Associated Secreted Aspartyl Proteinases in Candida albicans. J. Biomed. Sci. 2014, 21, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackey, E.; Vipulanandan, G.; Childers, D.S.; Kadosh, D. Comparative Evolution of Morphological Regulatory Functions in Candida Species. Eukaryot. Cell 2013, 12, 1356–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesely, E.M.; Williams, R.B.; Konopka, J.B.; Lorenz, M.C. N-Acetylglucosamine Metabolism Promotes Survival of Candida albicans in the Phagosome. mSphere 2017, 2, e00357-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunasekera, A.; Alvarez, F.J.; Douglas, L.M.; Wang, H.X.; Rosebrock, A.P.; Konopka, J.B. Identification of GIG1, a GlcNAc-Induced Gene in Candida albicans Needed for Normal Sensitivity to the Chitin Synthase Inhibitor Nikkomycin Z. Eukaryot. Cell 2010, 9, 1476–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanumantha Rao, K.; Paul, S.; Ghosh, S. N-Acetylglucosamine Signaling: Transcriptional Dynamics of a Novel Sugar Sensing Cascade in a Model Pathogenic Yeast, Candida albicans. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, M.; Su, C.; Dong, B.; Lu, Y. Candida albicans Exploits N-Acetylglucosamine as a Gut Signal to Establish the Balance between Commensalism and Pathogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, L.; Yuan, S.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Yan, Y. NGT1 Is Essential for N-Acetylglucosamine-Mediated Filamentous Growth Inhibition and HXK1 Functions as a Positive Regulator of Filamentous Growth in Candida tropicalis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamiu, A.T.; Albertyn, J.; Sebolai, O.M.; Pohl, C.H. Update on Candida krusei, a Potential Multidrug-Resistant Pathogen. Med. Mycol. 2021, 59, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiao, J.; Du, M.; Lei, W.; Yang, W.; Xue, X. Post-Translational Modifications Confer Amphotericin B Resistance in Candida krusei Isolated from a Neutropenic Patient. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1148681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveira-Pazos, C.; Robles-Iglesias, R.; Fernández-Blanco, C.; Veiga, M.C.; Kennes, C. State-of-the-Art in the Accumulation of Lipids and Other Bioproducts from Sustainable Sources by Yarrowia lipolytica. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 22, 1131–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo, M.; Shabbir Hussain, M.; Gambill, L.; Blenner, M. Alternative Substrate Metabolism in Yarrowia lipolytica. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beopoulos, A.; Cescut, J.; Haddouche, R.; Uribelarrea, J.L.; Molina-Jouve, C.; Nicaud, J.M. Yarrowia lipolytica as a Model for Bio-Oil Production. Prog. Lipid Res. 2009, 48, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, S.; Aggelis, G. Yarrowia lipolytica: A Model Microorganism Used for the Production of Tailor-made Lipids. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2010, 112, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seip, J.; Jackson, R.; He, H.; Zhu, Q.; Hong, S.-P. Snf1 Is a Regulator of Lipid Accumulation in Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 7360–7370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhoven, E.J.; Pomraning, K.R.; Baker, S.E.; Nielsen, J. Regulation of Amino-Acid Metabolism Controls Flux to Lipid Accumulation in Yarrowia lipolytica. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 2016, 2, 16005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abghari, A.; Chen, S. Engineering Yarrowia lipolytica for Enhanced Production of Lipid and Citric Acid. Fermentation 2017, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Wang, W.; Knoshaug, E.P.; Chen, X.; Van Wychen, S.; Bomble, Y.J.; Himmel, M.E.; Zhang, M. Disruption of the Snf1 Gene Enhances Cell Growth and Reduces the Metabolic Burden in Cellulase-Expressing and Lipid-Accumulating Yarrowia lipolytica. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 757741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Rao, K.H. Role of Carbon and Nitrogen Assimilation in Candida albicans Survival and Virulence. Microbe 2024, 4, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabas, N.; Morschhäuser, J. Control of Ammonium Permease Expression and Filamentous Growth by the GATA Transcription Factors GLN3 and GAT1 in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.S.; Coelho, C.; Leon-Rodriguez, C.M.; Rossi, D.C.; Camacho, E.; Jung, E.H.; Casadevall, A. Cryptococcus neoformans Urease Affects the Outcome of Intracellular Pathogenesis by Modulating Phagolysosomal pH. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, 1007144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silao, F.G.S.; Ljungdahl, P.O. Amino Acid Sensing and Assimilation by the Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans in the Human Host. Pathogens 2021, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrevens, S.; Zeebroeck, G.; Riedelberger, M.; Tournu, H.; Kuchler, K.; Dijck, P. Methionine Is Required for cAMP-PKA-mediated Morphogenesis and Virulence of Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 2018, 108, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomraning, K.R.; Bredeweg, E.L.; Baker, S.E. Regulation of Nitrogen Metabolism by GATA Zinc Finger Transcription Factors in Yarrowia lipolytica. mSphere 2017, 2, e00038-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Csutak, O.; Corbu, V.M. Molecular Triggers of Yeast Pathogenicity in the Yeast–Host Interactions. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47120992

Csutak O, Corbu VM. Molecular Triggers of Yeast Pathogenicity in the Yeast–Host Interactions. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):992. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47120992

Chicago/Turabian StyleCsutak, Ortansa, and Viorica Maria Corbu. 2025. "Molecular Triggers of Yeast Pathogenicity in the Yeast–Host Interactions" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47120992

APA StyleCsutak, O., & Corbu, V. M. (2025). Molecular Triggers of Yeast Pathogenicity in the Yeast–Host Interactions. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47120992