Abstract

HIV and parasite infections accelerate biological aging, resulting in immune senescence, apoptosis and cellular damage. Telomere length is considered to be one of the most effective biomarkers of biological aging. HIV and parasite infection have been reported to shorten telomere length in the host. This systematic review aimed to highlight work that explored the influence of HIV and parasite single infections and coinfection on telomere length. Using specific keywords related to the topic of interest, an electronic search of several online databases (Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, Science Direct and PubMed) was conducted to extract eligible articles. The association between HIV infection or parasite infection and telomere length and the association between HIV and parasite coinfection and telomere length were assessed independently. The studies reported were mostly conducted in the European countries. Of the 42 eligible research articles reviewed, HIV and parasite single infections were independently associated with telomere length shortening. Some studies found no association between antiretroviral therapy (ART) and telomere length shortening, while others found an association between ART and telomere length shortening. No studies reported on the association between HIV and parasite coinfection and telomere length. HIV and parasite infections independently accelerate telomere length shortening and biological aging. It is possible that coinfection with HIV and parasites may further accelerate telomere length shortening; however, this is a neglected field of research with no reported studies to date.

1. Introduction

Since 2000, the world’s life expectancy has increased; however, huge discrepancies remain within and across countries [1]. Sub-Saharan African countries, particularly those with poor socioeconomic status and healthcare facilities, have the lowest life expectancy rate in the world and are heavily burdened with infectious diseases [2]. Several viral (human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus, Cytomegalovirus and hepatitis C virus-2), bacterial (tuberculosis) and parasitic (malaria and soil-transmitted helminths) infections are highly endemic in sub-Saharan Africa and frequently coinfect the same host [3]. These infections can intensify oxidative stress and inflammation, leading to immune senescence, apoptosis, cellular damage and accelerated biological aging [4].

Telomere length is a hallmark of biological aging in the body [5]. A shorter telomere length may indicate that a host is biologically aging at a faster rate. Telomeres are double-stranded DNA sequences composed of the highly conserved guanine-rich hexonucleotide repeat expansion 5′-TTAGGG-3′. These nucleoprotein complexes are located at the termini of chromosomes and maintain chromosomal stability and integrity during cell division and replication [6]. The telomerase enzyme plays a role in telomere length elongation and maintenance in germ cells. Somatic cells lack telomerase activity, resulting in telomere length shortening with the progression of age [6]. Telomere length is a biomarker for biological aging and is concomitantly shortened with human aging [7]. Telomere shortening occurs in certain cell types and is linked to increased mitosis, especially during the presence of chronic infections and inflammatory conditions [8]. In response to infections, key immune cells like T cells, B cells and macrophages multiply rapidly to strengthen the body’s immune response [9]. Continued infections or inflammatory signals can cause continuous cell activation and division cycles. With each cell division, telomeres shorten due to the end-replication problem, where DNA polymerase is unable to fully replicate the ends of linear chromosomes. This process is further enhanced by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-6, which promote the growth of immune cells. Specifically, IL-6 stimulates the development and proliferation of T and B cells [10]. These powerful cytokines create a persistent inflammatory environment that spurs immune cells to undergo repeated rounds of division, resulting in telomere shortening. Infection and inflammation pose a threat to cells in certain tissues. To compensate for cell loss, the body triggers compensatory proliferation, prompting surviving cells to divide. In damaged tissues, stem and progenitor cells undergo increased mitosis to facilitate tissue healing and renewal [11]. If telomerase activity is inadequate to fully compensate for telomeric DNA loss during cell division, accelerated cell turnover may hasten telomere shortening. Replicative senescence begins when telomeres reach a critical length and continue to shrink with each successive cell division [12].

The shortening of telomeres resulting from natural processes (e.g., stress and cellular aging) reflects a competing and non-exclusive causal pathway linking the rate of aging and immunological responses [13]. Cumulative oxidative stress and chronic inflammation together with genetic and epigenetic modifications can trigger aberrant telomere length shortening, leading to chromosomal instability, gene expression changes, impaired cellular function and viability, biological aging and cellular senescence [14]. Senescent cells, also known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), stop dividing but remain metabolically active and often release inflammatory chemicals [15]. The accumulation of senescent cells accelerates telomere shortening in neighboring cells by sustaining a cycle of damage and compensatory proliferation [16]. This process leads to tissue malfunction and persistent inflammation [16]. Chronic viral infections such as HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C continuously activate immune cells and cause their proliferation [17]. For example, HIV infection causes T-cell turnover and prolonged immunological activation, resulting in significant telomere shortening in T cells. Prolonged immunological responses are triggered by persistent bacterial infections like tuberculosis, which promote the growth of macrophages and lymphocytes, leading to telomere attrition in these cells [18]. Depending on the species and host response, parasitic diseases like leishmaniasis can either cause chronic inflammation, which increases cell turnover and telomere shortening, or limit reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, which promotes telomere stability [19].

The process of telomere shortening is influenced by a multitude of cellular and molecular processes [20]. These encompass telomerase activity, the DNA damage response, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, the inherent constraints of DNA replication and the regulation of telomere-binding proteins. During DNA replication, the 3′ ends of linear chromosomes are not fully replicated by DNA polymerase, leaving a small single-stranded overhang [21]. With each cell division, the degradation of this overhang causes the telomeres to gradually shrink. The end-replication issue causes a cell’s telomeres to slightly shorten with each division. Following numerous divisions, telomeres attain a certain length, which triggers a DNA damage response and results in replicative senescence, a condition in which cells cease to divide but retain metabolic activity [22].

Oxidative DNA damage, particularly in the telomeres, can be brought on by ROS produced during cellular metabolism or in response to environmental stress [23]. Guanine, found abundantly in telomeric DNA, is particularly susceptible to oxidative damage, leading to telomere shortening and strand breakage [24]. Chronic inflammation can trigger the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, which induce oxidative stress and support cell growth [25]. The activation of signaling pathways like NF-κB by these cytokines can lead to increased ROS production and telomere damage.

When telomeres reach a critically short length, they trigger the activation of repair proteins such as ATM and ATR [14,26]. Repeated damage response can result in cellular aging or apoptosis. While telomeres form protective T-loops to shield themselves, any damage or disruption to these structures can lead to further shortening. Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, can influence telomere length and telomerase function [27]. For instance, methylation of the TERT gene’s promoter region can constrain telomerase activity. The sheltering complex comprises essential proteins such as POT1, TRF1 and TRF2, which play a crucial role in protecting telomeres from being identified as DNA breaks [28]. Dysregulation of these proteins can lead to accelerated shortening and disruption of telomeres. Additionally, damage to DNA, specifically extremely short telomeres, can trigger the activation of the tumor suppressor protein p53, resulting in senescence, apoptosis or cell cycle arrest [29]. Persistent p53 activation due to chronic telomere shortening has been linked to tissue deterioration and aging. Inflammation and stress induce cellular reactions involving the AP-1 transcription factor and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, potentially leading to increased ROS generation and telomere degradation [30]. Moreover, telomere length plays a crucial role in affecting the process of autophagy, essential for cell maintenance [31]. If a cell has short telomeres, it may undergo HIV and parasitic infections that can result in oxidative stress and inflammation [4,32].

HIV infection is linked to immunological activation and chronic inflammation, which causes immune cells’ telomeres to shorten and their production of ROS to increase [33]. Infections like HIV can affect telomere shortening through various routes, including enzymatic and signaling pathways. Increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS) can occur during infection when the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway is activated [34]. Consequently, ROS cause oxidative damage to DNA, including telomeres. Another signaling route triggered during infections that may result in elevated ROS generation is the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway [35]. ROS produced by the immune system can directly harm telomere-associated DNA [23]. Due to their high guanine concentration, repeated DNA regions known as telomeres are especially vulnerable to oxidative damage [23]. The chromosome-ending enzyme telomerase, responsible for appending telomeric repeats, can become dysfunctional due to prolonged exposure to oxidative stress [36]. As a result, telomere maintenance and repair are unsuccessful.

During HIV-1 infection, pro-inflammatory Th1 cytokines (IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α) are often upregulated while anti-inflammatory Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-10) are normally downregulated [37]. These alterations are a reflection of the complex interactions that affect immunological dysfunction and disease progression between the virus and the host immune system. Immunological senescence is characterized by low numbers of naïve T cells, higher frequencies of differentiated CD28−CD57+ T cells with reduced proliferative ability, a reduced CD4/CD8 ratio, oligoclonal expansion of CD8 T cells and gradual shortening of telomeres [38]. It has been reported that HIV infection accelerates the shortening of the telomere length in an individual, thus leading to biological aging [39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

Cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-10 and IL-13 have a role in regulating immunological responses during parasitic infections [46,47]. They play a role in downregulating the immunological inflammatory response, attracting and activating immune cells, promoting the development of the immunoglobulin E response and eliminating parasites [46]. Various immune cells, including mast cells, eosinophils and T-helper cells, produce these cytokines. The type 2 (Th2) immune response, which includes B-cell-produced antibodies like IgA and IgE plus cytokines like IL4, is the hallmark of the immunological response to helminths such as Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, and the hookworms Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale [48]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin-12 (IL-12), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), are produced in large quantities in response to protozoan parasites (Plasmodium spp., Trypanosoma spp., Entamoeba spp. and Toxoplasma gondii) and are essential for the activation of macrophages and the destruction of intracellular parasites [49]. Furthermore, CD4+ T cells play a major role in the immune response to protozoan parasites through the release of cytokines that activate macrophages and promote parasite elimination [50]. Inflammatory diseases and parasites can produce more reactive oxygen species (ROS), which may increase the rate of telomere attrition [51]. It was indeed found that parasitic infections lead to telomere length shortening and accelerated biological aging [51,52,53,54,55,56,57].

Parasite infections have been suggested to influence the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection because they have modulatory effects on the human immune system [58]. As a result, those who are afflicted are proposed to be more susceptible to HIV-1 infection and less able to handle it [58]. Chronic parasitic infection may inhibit the immune system’s defenses against HIV-1, while concomitant immunological activation may cause HIV-1-infected individuals to lose CD4 cells more quickly [59]. Furthermore, HIV-1-specific CD4+ and CD8+ proliferation and cytokine production may be suppressed by immunoregulation in response to parasite infection, which may impair control of HIV-1 replication and may enhance cellular vulnerability to HIV-1 infection as well [60]. Malnutrition and anemia, also associated with telomere shortening, were reported in individuals coinfected with HIV and parasites [61].

In contrast to how parasites interact with their hosts, HIV negatively impacts the host by impairing immune functions. With respect to human disease, parasitic-mediated immune regulation may have both advantageous and disadvantageous effects [62].

Enzymes, structural proteins, transport proteins, signaling proteins, receptors, chaperones, ion channels and apoptotic proteins are essential for immune response and cellular function. Their changes during infections can substantially affect the course of a disease. HIV and parasites frequently target or modify enzymes, which are crucial catalysts in metabolic pathways that enable their survival and replication [63]. For example, HIV protease breaks down viral polyproteins into useful proteins required for virus assembly. Similarly, parasite enzymes such as proteases facilitate the invasion of host tissue and the uptake of nutrients [64]. Maintaining the integrity and functionality of cells depends on structural proteins, which include those that make up the extracellular matrix and cytoskeleton. HIV can alter cytoskeletal proteins, limiting immune cell movement and promoting cellular dysfunction [65]. The extracellular matrix might change due to parasites. Chaperones support the folding and stability of proteins, which is essential for preserving cellular function under stress [66]. To guarantee that viral or parasitic proteins fold correctly and support the creation and maintenance of infections, HIV and parasites may take over host chaperones. Apoptotic proteins control the process of programmed cell death, which is essential for tissue homeostasis and immunological responses [67]. To extend host cell survival and promote viral replication or parasite survival within host tissues, HIV and parasites can interfere with apoptotic pathways [68].

ART effectively controls active viral infection by reducing HIV replication in plasma to undetectable levels [69]. Nevertheless, it fails to eliminate latent HIV reservoirs, which means that chronic immune activation and ongoing low-level viral activity exist [69]. HIV-positive people may have persistent immunological dysfunction despite viral suppression, characterized by dysregulated immune signaling pathways and altered cytokine profiles [70]. These factors can impact immune surveillance and responses against opportunistic diseases, such as parasites. Although antiretroviral therapy (ART) is an effective means of inhibiting active HIV replication and enhancing immune function in those under treatment, HIV latency, telomere shortening, immune dysregulation, changed cytokine profiles and signaling pathway activation all contribute to persistent immunological deficits and heightened vulnerability to parasitic infections [71].

There are limited studies on the association between telomere length and parasite single infection. In addition, although there are no reported studies on the association between telomere length and HIV and parasite coinfection, data from studies investigating the association between telomere length and HIV [39,41,42,43,44,45,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100] and parasite [51,52,53,54,55,56,57] single infections support the hypothesis that HIV and parasite coinfection may further accelerate telomere length shortening and biological aging. Furthermore, investigating the connection between telomere length and HIV–parasite coinfection is crucial to determine whether biological aging can further be accelerated by parasites and viral infections, which will also aid in the development of efficient treatments and vaccines. This systematic review aims to summarize the effects of HIV infections on telomere length, helminth infections on telomere length and HIV–helminth coinfections on telomere length. However, articles on the latter (dual infection), which is the focus of our work, could not be found upon searching the literature during the study period of 1990–2024.

2. Method

This systematic review compiled relevant information from published studies investigating whether HIV and parasite single infection and coinfection influence telomere length shortening. A narrative approach was used to review relevant and available data on this topic. This systematic review was registered under PROSPERO (reference: CRD42024535337).

2.1. Search Strategy

Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, Science Direct and PubMed were used to search for relevant studies using the following keywords: “Telomere length and Human Immunodeficiency Virus/HIV infection”, “telomere length and parasite/parasitic infection” and “telomere length and Human Immunodeficiency Virus/HIV and parasite/ parasitic infection”. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines were followed to analyze and report the relevant studies. Articles published in the English language from January 1990 to May 2024 were included.

2.2. Study Selection, Study Quality, and Data Extraction

To identify appropriate literature based on tittles, abstracts and full texts, exclusion and inclusion criteria were followed by the main author (E.D.M). The eligibility of the literature was verified and accepted by the co-authors (J.M., P.N. and Z.L.M.-K.) The quality of the relevant data retrieved from the literature was divided into four categories: high, moderate, poor and extremely low [101]. This was evaluated using the grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluations (GRADE) system [102].

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

Articles published in January 1990–May 2024.

Published in English.

Human and animal studies.

Cohort, case-controlled studies and cross-sectional studies.

Articles reporting on telomere length and HIV infection.

Articles reporting on telomere length and parasite infection.

Articles reporting on telomere length and HIV and parasite coinfection.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Articles published prior to January 1990.

Reviews, research letters, conference abstracts, book chapters and editorial corrections.

Articles not published in English.

Studies including major chronic infections and diseases.

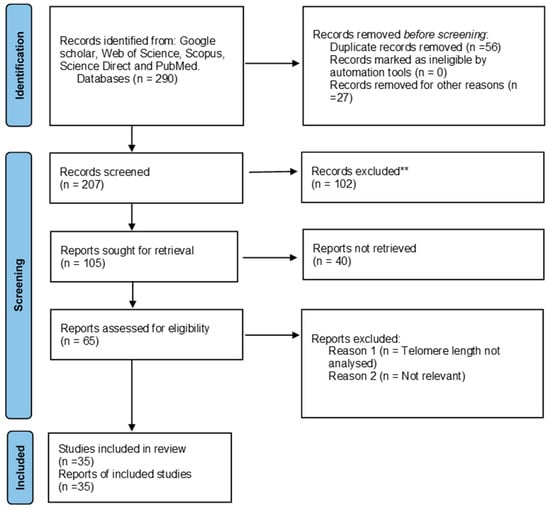

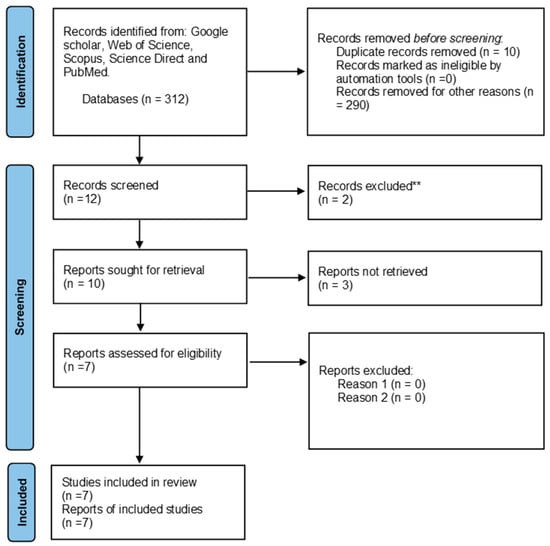

The search criteria yielded a total of 290 articles for telomere length and HIV and 312 articles for telomere length and parasites in the previously mentioned databases. Of the 290 articles, 234 were retrieved after removing duplicated studies and further evaluated based on the eligibility criteria. Of the 65 reports assessed for eligibility, only 35 reports were included in the review that summarizes data found on the association between HIV and telomere length. Additionally, of the 312 articles, 302 were retrieved after removing duplicated studies and further evaluated based on the eligibility criteria. Of the 10 reports assessed for eligibility, only 7 were included in the review that summarizes data found on the association between HIV and telomere length. There were no studies reporting the association between telomere length and HIV and parasite coinfection. A PRISMA 2020 flow diagram was used to record the whole selection process (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the article selection process used to collect, screen and identify eligible data of relevant articles based on telomere length and HIV. ** Not related to the study.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the article selection process used to collect, screen and identify eligible data of relevant articles based on telomere length and parasites. ** Not related to the study.

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes all studies investigating the association between telomere length and HIV infection. Table 2 summarizes all studies investigating the association between telomere length and parasite infections.

Table 1.

Studies associating HIV infection with telomere length.

Table 2.

Studies associating parasite infection with telomere length.

There were no published studies investigating whether HIV and parasite coinfection influence telomere length shortening.

4. Discussion

This is the first systematic review to investigate the association between HIV and parasite single infection and coinfection and telomere length. Shorter telomere length was associated with HIV single infection [41,42,43,44,45,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100] and parasite single infection [51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. No studies report on the association between HIV and parasite coinfection and telomere length.

Several studies reported telomere length shortening in HIV-infected humans [41,42,43,44,71,80,81,83,87,90,91]. These studies also support the idea that biological aging in HIV-infected individuals can be accelerated by telomere attrition, chronic inflammatory environment, immune activation, mitochondrial dysfunction and altered epigenetic patterns. HIV infection results in chronic immune activation, oxidative stress and inflammation [81]. Premature telomere length shortening after HIV infection may be caused by a number of variables, including oxidative stress, HIV viral Tat proteins, persistent immunological activation, inflammation and combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) [80]. HIV infection was associated with shorter LTL [73]. Several studies assessed the association between HIV infection and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells; they observed telomere shortening in CD4+ and CD8+ during HIV infection in participants [88,92,96,97,99]. Chronic immune activation continues even in HIV-positive patients whose antiretroviral medication effectively suppresses viral replication [106].

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in antiretroviral therapy may also cause accelerated telomere shortening as they inhibit telomerase activity [107]. Adults infected with HIV had shorter telomeres, increased levels of immunological activation, increased regulatory T cells, and increased CD4+ cells that expressed PD-1, even after receiving ART [89]. At clinically achievable concentrations, tenofovir (TDF) was discovered to be the most powerful telomerase inhibitor and to cause the greatest amount of telomere shortening [93]. Furthermore, individuals treated with tenofovir for four years showed reduced telomerase in CD4+ cells and lower telomere length in CD8+ cells [100]. Individuals receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) with efavirenz had significantly shorter telomeres than those receiving nevirapine [74]. Delaying the start of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in HIV-positive individuals, even by a few weeks, was associated with significant and persistent TL shortening [76]. On the contrary, the study presented in [78] reported that introducing ART in an HIV-infected individual limits the amount of the viral reservoir and stops telomere shortening and premature immune senescence. An increase in telomere length was observed in HIV participants who are on ART [75]. Studies [42,45,88,95] that found no correlation between ART and telomere length indicate that HIV-1 itself, rather than exposure to ART, is the source of rapid telomere shortening.

The relative telomere length of newborn leukocytes was reported to be influenced by maternal HIV infection or antiretroviral therapy exposure [72]. Regardless of the prophylactic treatment, telomere shortening was noted in 44.3% of children exposed to HIV in utero, but not infected with the virus [77]. HIV-infected children and adolescents had shorter telomeres in peripheral blood cells than age-matched HIV-uninfected participants [87,88]. Furthermore, among the children infected with HIV, the telomeres of the viremic children were shorter than those of the aviremic children [88,95]. The fact that children who test positive for HIV-1 have higher percentages of both activated and senescent CD8 cells, which inversely correlate with telomere length, provides additional evidence for the association between immunosenescence and biological aging [78].

Despite a lack of research and documentation regarding the relationship between the parasites and telomere length in infected humans, studies on parasite and telomere length in animals show that parasite infections might have an impact on telomere length shortening. A study on blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus), discovered that chronic infection with haemosporidians that cause avian malaria and malaria-like illness was related to shorter telomeres in females compared to males [53]. Another study discovered that chronic malaria infection increased telomere shortening and shortened lifespan in mice [56]. According to [52], very low parasite exposure causes inflammation and oxidative stress, which accelerate telomere shortening and cellular senescence. According to [54], blood and tissue samples from the liver, lungs, spleen, heart, kidney, and brain of birds showed concurrent telomere shortening due to malaria infection. The study also found that compared to the control group, the blood of experimentally infected birds showed faster telomere attrition after infection. Similar findings were observed in [55], which discovered that human telomere shortening is caused by malaria infection. Haemosporidian Leucocytozoon parasitic infection was observed in tawny owls; infected owls had shorter telomere lengths than uninfected owls [57]. The relationship between telomere length and parasite (Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae) load was investigated in wild brown trout (Salmo trutta) [24]. The Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae parasite is known to cause proliferative kidney disease (PKD). PKD symptoms and the parasite load were linked to growth delays, and no significant associations between parasite burden and telomere length or antioxidant (AO) levels were discovered. Furthermore, these findings indicated that the various elements of the AO responses are linked to kidney hyperplasia and development, and that telomere length may represent quality in terms of an individual’s capacity to grow despite the parasite infection. Findings from the above-mentioned studies suggest that parasite infection can accelerate telomere length shortening in both humans and animals.

Since there are no studies investigating the association between HIV and parasite coinfection and telomere length, the findings above thus support our hypothesis that HIV and parasite coinfection indeed further accelerates telomere shortening. Future research should concentrate more on the relationship between telomere length and soil-transmitted helminth infections, human parasite infections, and the effects of parasite abundance on host telomere length.

5. Limitations

The studies on the association of parasites and telomere length were more based on malaria infection and animals, rather than humans, which might weaken the strength of our findings since different parasites affect different hosts in different ways. Th1 and Th2 cells, which are the most important factor in HIV and helminth coinfection, were not reported in the included studies. More reported studies were conducted in European countries, so regions like sub-Saharan Africa that have high HIV and parasite prevalence were less studied. The current study reported only articles that were written in English. There are no studies reporting the association between HIV and parasite coinfection and telomere length. There was a size imbalance between the studied groups [43,44,45,78,82,88,89,91,92,94,95,96]. Confounders such as sociodemographic factors and biochemical and full blood count parameters were not adjusted in some of the reported studies [43]. The required information on telomere length dynamics can be obtained by long-term studies, which also help validate or disprove the idea that early environmental factors influence an adult’s susceptibility to prevalent diseases. Some studies did not compare HIV-infected and uninfected individuals [74]. In regard to assessing the association of different types of ART in HIV-infected individuals, the study periods should be years longer, since ART takes more time to influence telomerase and telomere length [93]. Guidance on how to promote better aging in HIV-positive patients can be obtained by understanding these mechanisms.

6. Conclusions

The present study found that HIV and parasite single infections accelerate telomere length shortening. From the data retrieved in the reported studies, we can hypothesize that HIV and parasite coinfection accelerates telomere length shortening. HIV and parasite coinfections negatively impact the host immune system, and, paying attention to the documentation or studies conducted, these infections receive less attention. More studies should be conducted on the association of telomere length and HIV and helminth coinfections and other coinfections. Additionally, how the treatments used for these infections affect telomerase and telomere length should be studied as well. These studies can help in producing new suitable treatments for chronic infections and biological aging.

Furthermore, there is a large gap in genomics. Human genomes and infections, genome integrity caused by infections and coinfections, telomere length, and coinfections, mainly HIV and helminths, should be given more attention. Since some species of helminths result in cancer, further studies should focus on the association between cancer, helminths, HIV, and other infections, as well as the shortening of the telomere length.

In conclusion, prevention of HIV–helminth coinfection should be our priority, followed by educating the citizens about these kinds of coinfections and how to prevent them. Citizens should also be encouraged to take regular tests, as many citizens are unknowingly infected. To save money and state resources on vaccines for coinfections, supplements or treatments for healthy telomerase should be created.

Author Contributions

E.D.M.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing original draft and reviewing and editing; J.M.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, validation and reviewing and editing; P.N.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation and reviewing and editing; Z.L.M.-K.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation and reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by SAMRC (ZLMK MSC grant number: HDID5149/KR/2021) through its Division of Research Capacity Development under the Research Capacity Development Initiative from funding received from the South African National Treasury. The content and findings reported/illustrated are the sole deduction, view and responsibility of the researchers and do not reflect the official position and sentiments of the SAMRC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was sought from the University of KwaZulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BE351/19, approval date: 24 January 2022; BREC/00004901/2022, approval date: 19 December 2022). The study was also approved by the Department of Health, eThekwini District and KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Department of Health.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the SAMRC for providing funding for this research and NRF for providing funding for the main author. They would also like to extend their thanks to the study participants, the staff at the HCT clinic and the eThekwini District and KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Departments of Health for their support throughout the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, W.; Kowal, P.; Naidoo, N. Trends in Health and Well-Being of the Older Populations in SAGE Countries: 2014–2015. International Population Reports. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Wan-He-5/publication/330205643_Trends_in_Health_and_Well-Being_of_the_Older_Populations_in_SAGE_Countries/links/5c33dcc792851c22a36382b2/Trends-in-Health-and-Well-Being-of-the-Older-Populations-in-SAGE-Countries.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2024).

- Gyasi, R.M.; Phillips, D.R.; Meeks, S. Aging and the Rising Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa and other Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A Call for Holistic Action. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annison, L.; Hackman, H.; Eshun, P.F.; Annison, S.; Forson, P.; Antwi-Baffour, S. Seroprevalence and effect of HBV and HCV co-infections on the immuno-virologic responses of adult HIV-infected persons on anti-retroviral therapy. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohanka, M. Role of oxidative stress in infectious diseases. A review. Folia Microbiol. 2013, 58, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettin, N.; Oss Pegorar, C.; Cusanelli, E. The Emerging Roles of TERRA in Telomere Maintenance and Genome Stability. Cells 2019, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, K.J.; Vasu, V.; Griffin, D.K. Telomere Biology and Human Phenotype. Cells 2019, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Ruiz, C.M.; Gussekloo, J.; Van Heemst, D.; Von Zglinicki, T.; Westendorp, R.G. Telomere length in white blood cells is not associated with morbidity or mortality in the oldest old: A population-based study. Aging Cell 2005, 4, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.M.; Lee, X.W.; Wang, X. Telomere shortening in human diseases. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 3180–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, J.S.; Toapanta, F.R. B and T cell immunity in tissues and across the ages. Vaccines 2021, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kany, S.; Vollrath, J.T.; Relja, B. Cytokines in inflammatory disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayavoo, T.; Murugesan, K.; Gnanasekaran, A. Roles and mechanisms of stem cell in wound healing. Stem Cell Investig. 2021, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.P. Roles of telomere biology in cell senescence, replicative and chronological ageing. Cells 2019, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudeau, M.; Heidinger, B.; Bonneaud, C.; Sepp, T. Telomere shortening as a mechanism of long-term cost of infectious diseases in natural animal populations. Biol. Lett. 2019, 15, 20190190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavia-García, G.; Rosado-Pérez, J.; Arista-Ugalde, T.L.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Telomere length and oxidative stress and its relation with metabolic syndrome components in the aging. Biology 2021, 10, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Qian, P.; Huang, H. Inflammation and aging: Signaling pathways and intervention therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023, 8, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Jat, P. Mechanisms of Cellular Senescence: Cell Cycle Arrest and Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouse, B.T.; Sehrawat, S. Immunity and immunopathology to viruses: What decides the outcome? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoef, J.; Van Kessel, K.; Snippe, H. Immune Response in Human Pathology: Infections Caused by Bacteria, Viruses, Fungi, and Parasites. Nijkamp Parnham’s Princ. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Da-Silva, A.C.; Nascimento, D.D.O.; Ferreira, J.R.M.; Guimarães-Pinto, K.; Freire-De-Lima, L.; Morrot, A.; Decote-Ricardo, D.; Filardy, A.A.; Freire-De-Lima, C.G. Immune Responses in Leishmaniases: An Overview. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiserman, A.; Krasnienkov, D. Telomere Length as a Marker of Biological Age: State-of-the-Art, Open Issues, and Future Perspectives. Front. Genet. 2021, 11, 630186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnell, E.; Pasquier, E.; Wellinger, R.J. Telomere Replication: Solving Multiple End Replication Problems. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 668171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivas, N.; Rachakonda, S.; Kumar, R. Telomeres and telomere length: A general overview. Cancers 2020, 12, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, R.P.; Fouquerel, E.; Opresko, P.L. The impact of oxidative DNA damage and stress on telomere homeostasis. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2019, 177, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Kukreti, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S. Oxidative Stress: Role and Response of Short Guanine Tracts at Genomic Locations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, L.; Prather, E.R.; Stetskiv, M.; Garrison, D.E.; Meade, J.R.; Peace, T.I.; Zhou, T. Inflammaging and oxidative stress in human diseases: From molecular mechanisms to novel treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Nguyen, L.N.T.; Dang, X.; Cao, D.; Khanal, S.; Schank, M.; Thakuri, B.K.C.; Ogbu, S.C.; Morrison, Z.D.; Wu, X.Y.; et al. ATM Deficiency Accelerates DNA Damage, Telomere Erosion, and Premature T Cell Aging in HIV-Infected Individuals on Antiretroviral Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, F.; Forsyth, N.R. Telomerase Regulation: A Role for Epigenetics. Cancers 2021, 13, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lange, T. Shelterin: The protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 2100–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şerifoğlu, N.; Lopes-Bastos, B.; Ferreira, M.G. Lack of telomerase reduces cancer incidence and increases lifespan of zebrafish tp53M214K mutants. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsaves, V.; Leventaki, V.; Rassidakis, G.Z.; Claret, F.X. AP-1 Transcription Factors as Regulators of Immune Responses in Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, P.; Alzahrani, A.M.; Hanieh, H.N.; Kumar, S.A.; Ben Ammar, R.; Rengarajan, T.; Alhoot, M.A. Autophagy and senescence: A new insight in selected human diseases. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 21485–21492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorci, G.; Faivre, B. Inflammation and oxidative stress in vertebrate host–parasite systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, S.; Byrnes, S.; Cochrane, C.; Roche, M.; Estes, J.D.; Selemidis, S.; Angelovich, T.A.; Churchill, M.J. The role of oxidative stress in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Brain Behav. Immun.-Health 2021, 13, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Tran, K.; Reddy, S.P.; Malik, A.B. Reactive Oxygen Species in Inflammation and Tissue Injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1126–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, D.S.A.; Oliver, P.L. ROS Generation in Microglia: Understanding Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, W.C.; Meyerson, M. Telomerase activation, cellular immortalization and cancer. Ann. Med. 2001, 33, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Singh Dhakad, M. Study of TH1/TH2 Cytokine Profiles in HIV/AIDS Patients in a Tertiary Care Hospital in India. J. Med. Microbiol. Diagn. 2016, 5, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, S.G. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011, 62, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, E.C.; Sehl, M.E.; Shih, R.; Langfelder, P.; Wang, R.; Horvath, S.; Bream, J.H.; Duggal, P.; Martinson, J.; Wolinsky, S.M.; et al. Accelerated aging with HIV begins at the time of initial HIV infection. iScience 2022, 26, 107381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, M.; Oursler, K.K.; Xu, K.; Sun, Y.V.; Marconi, V.C. Biological ageing with HIV infection: Evaluating the geroscience hypothesis. Lancet Health Longev. 2022, 3, e194–e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehl, M.E.; Breen, E.C.; Shih, R.; Chen, L.; Wang, R.; Horvath, S.; Bream, J.H.; Duggal, P.; Martinson, J.; Wolinsky, S.M.; et al. Increased Rate of Epigenetic Aging in Men Living with HIV Prior to Treatment. Front. Genet. 2022, 12, 796547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoepf, I.C.; Thorball, C.W.; Ledergerber, B.; Kootstra, N.A.; Reiss, P.; Raffenberg, M.; Engel, T.; Braun, D.L.; Hasse, B.; Thurnheer, C.; et al. Telomere Length Declines in Persons with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Before Antiretroviral Therapy Start but Not After Viral Suppression: A Longitudinal Study Over >17 Years. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.R.; Iudicello, J.E.; Lin, J.; Ellis, R.J.; Morgan, E.; Okwuegbuna, O.; Cookson, D.; Karris, M.; Saloner, R.; Heaton, R.; et al. Telomere length is associated with HIV infection, methamphetamine use, inflammation, and comorbid disease risk. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 221, 108639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J.M.; Fishbane, N.; Jones, M.; Morin, A.; Xu, S.; Liu, J.C.; MacIsaac, J.; Milloy, M.-J.; Hayashi, K.; Montaner, J.; et al. Longitudinal study of surrogate aging measures during human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion. Aging 2017, 9, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanet, D.L.; Thorne, A.; Singer, J.; Maan, E.J.; Sattha, B.; Le Campion, A.; Soudeyns, H.; Pick, N.; Murray, M.; Money, D.M.; et al. Association between short leukocyte telomere length and hiv infection in a cohort study: No evidence of a relationship with antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, A.; Abdullah, S. Impact of parasitic infection on human gut ecology and immune regulations. Transl. Med. Commun. 2021, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpaka-Mbatha, M.N.; Naidoo, P.; Singh, R.; Bhengu, K.N.; Nembe-mafa, N.; Pillay, R.; Duma, Z.; Niehaus, A.J.; Mkhize-kwitshana, Z.L.; Africa, S.; et al. Immunological interaction during helminth and HIV co-infection: Integrative research needs for sub-Saharan Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2023, 119, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyasu, S.; Moro, K. Type 2 innate immune responses and the natural helper cell. Immunology 2011, 132, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegewald, J.; Gantin, R.G.; Lechner, C.J.; Huang, X.; Agosssou, A.; Agbeko, Y.F.; Soboslay, P.T.; Köhler, C. Cellular cytokine and chemokine responses to parasite antigens and fungus and mite allergens in children co-infected with helminthes and protozoa parasites. J. Inflamm. 2015, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, P.; Kanneganti, T.-D. Immune responses against protozoan parasites: A focus on the emerging role of Nod-like receptors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3035–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, J.; Bruneaux, M.; Panda, B.; Visse, M.; Vasemägi, A.; Ilmonen, P. Telomere length and antioxidant defense associate with parasite-induced retarded growth in wild brown trout. Oecologia 2017, 185, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglar, A.; Reuling, I.J.; Yap, X.Z.; Färnert, A.; Sauerwein, R.W.; Asghar, M. Biomarkers of cellular aging during a controlled human malaria infection. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudyka, J.; Podmokła, E.; Drobniak, S.M.; Dubiec, A.; Arct, A.; Gustafsson, L.; Cichoń, M. Sex-specific effects of parasites on telomere dynamics in a short-lived passerine—The blue tit. Sci. Nat. 2019, 106, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.; Palinauskas, V.; Zaghdoudi-Allan, N.; Valkiūnas, G.; Mukhin, A.; Platonova, E.; Färnert, A.; Bensch, S.; Hasselquist, D. Parallel telomere shortening in multiple body tissues owing to malaria infection. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20161184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.; Yman, V.; Homann, M.V.; Sondén, K.; Hammar, U.; Hasselquist, D.; Färnert, A. Cellular aging dynamics after acute malaria infection: A 12-month longitudinal study. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, M.; Hasselquist, D.; Hansson, B.; Zehtindjiev, P.; Westerdahl, H.; Bensch, S. Hidden costs of infection: Chronic malaria accelerates telomere degradation and senescence in wild birds. Science 2015, 347, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karell, P.; Bensch, S.; Ahola, K.; Asghar, M. Pale and dark morphs of tawny owls show different patterns of telomere dynamics in relation to disease status. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 284, 20171127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkow, G.; Bentwich, Z. HIV and helminth co-infection: Is deworming necessary? Parasite Immunol. 2006, 28, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggena, M.P.; Barugahare, B.; Okello, M.; Mutyala, S.; Jones, N.; Ma, Y.; Kityo, C.; Mugyenyi, P.; Cao, H. T cell activation in HIV-seropositive Ugandans: Differential associations with viral load, CD4+ T cell depletion, and coinfection. J. Infect Dis. 2005, 191, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walson, J.L.; John-Stewart, G. Treatment of helminth co-infection in HIV-1 infected individuals in resource-limited settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, CD006419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpaka-Mbatha, M.N.; Naidoo, P.; Islam, M.; Singh, R.; Mkhize-Kwitshana, Z.L. Anaemia and Nutritional Status during HIV and Helminth Coinfection among Adults in South Africa. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Mawa, P.A.; Kaleebu, P.; Elliott, A.M. Helminths and HIV infection: Epidemiological observations on immunological hypotheses. Parasite Immunol. 2006, 28, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissapatorn, V.; Sawangjaroen, N. Parasitic infections in HIV infected individuals: Diagnostic & therapeutic challenges. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011, 134, 878–897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmid-Hempel, P. Immune defence, parasite evasion strategies and their relevance for “macroscopic phenomena” such as virulence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, E.; Meuser, M.E.; Cunanan, C.J.; Cocklin, S. Structure, Function, and Interactions of the HIV-1 Capsid Protein. Life 2021, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, F.U.; Bracher, A.; Hayer-Hartl, M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 2011, 475, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nano, M.; Montell, D.J. Apoptotic signaling: Beyond cell death. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 156, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, H.-Y.; Lee, C.-Y. Inhibiting viral replication and prolonging survival of hosts by attenuating stress responses to viral infection. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2022, 190, 107753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Picado, J.; Deeks, S. Persistent HIV-1 replication during antiretroviral therapy. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2016, 11, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Cao, W.; Li, T. HIV-Related Immune Activation and Inflammation: Current Understanding and Strategies. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pommier, J.P.; Gauthier, L.; Livartowski, J.; Galanaud, P.; Boué, F.; Dulioust, A.; Marcé, D.; Ducray, C.; Sabatier, L.; Lebeau, J.; et al. Immunosenescence in HIV pathogenesis. Virology 1997, 231, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurashova, N.A.; Vanyarkina, A.S.; Petrova, A.G.; Rychkova, L.V.; Kolesnikov, S.I.; Darenskaya, M.A.; Moskaleva, E.V.; Kolesnikova, L.I. Length of leukocyte telomeres in newborn from HIV-infected mothers. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 175, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ommen, C.E.; Hsieh, A.Y.Y.; Albert, A.Y.; Kimmel, E.R.; Cote, H.C.F.; Maan, E.J.; Prior, J.C.; Pick, N.; Murray, M.C.M. Lower anti-Müllerian hormone levels are associated with HIV in reproductive age women and shorter leukocyte telomere length among late reproductive age women. Aids 2023, 37, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukic, E.; Milasin, J.; Toljic, B.; Jadzic, J.; Jevtovic, D.; Obradovic, B.; Dragovic, G. Association between Combination Antiretroviral Therapy and Telomere Length in People Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Biology 2023, 12, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, F.; Sanfilippo, A.; Fabbiani, M.; Borghetti, A.; Ciccullo, A.; Tamburrini, E.; Di Giambenedetto, S. Blood telomere length gain in people living with HIV switching to dolutegravir plus lamivudine versus continuing triple regimen: A longitudinal, prospective, matched, controlled study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 2315–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffenberg, M.; Engel, T.; Schoepf, I.C.; Kootstra, N.A.; Reiss, P.; Braun, D.L.; Thorball, C.W.; Fellay, J.; Kouyos, R.D.; Ledergerber, B.; et al. Impact of Delaying Antiretroviral Treatment During Primary Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection on Telomere Length. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 1775–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnin, A.; Vizeneux, A.; Nagot, N.; Eymard-Duvernay, S.; Meda, N.; Singata-Madliki, M.; Ndeezi, G.; Tumwine, J.K.; Kankasa, C.; Goga, A.; et al. Longitudinal Follow-Up of Blood Telomere Length in HIV-Exposed Uninfected Children Having Received One Year of Lopinavir/Ritonavir or Lamivudine as Prophylaxis. Children 2021, 8, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalzini, A.; Ballin, G.; Dominguez-Rodriguez, S.; Rojo, P.; Petrara, M.R.; Foster, C.; Cotugno, N.; Ruggiero, A.; Nastouli, E.; Klein, N.; et al. Size of HIV-1 reservoir is associated with telomere shortening and immunosenescence in early-treated European children with perinatally acquired HIV-1. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24, e25847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, A.Y.; Kimmel, E.; Pick, N.; Sauvé, L.; Brophy, J.; Kakkar, F.; Bitnun, A.; Murray, M.C.; Côté, H.C. Inverse relationship between leukocyte telomere length attrition and blood mitochondrial DNA content loss over time. Aging 2020, 12, 15196–15221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minami, R.; Takahama, S.; Yamamoto, M. Correlates of telomere length shortening in peripheral leukocytes of HIV-infected individuals and association with leukoaraiosis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auld, E.; Lin, J.; Chang, E.; Byanyima, P.; Ayakaka, I.; Musisi, E.; Worodria, W.; Davis, J.L.; Segal, M.; Blackburn, E.; et al. HIV infection is associated with shortened telomere length in ugandans with suspected tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, H.; Ambikan, A.T.; Gabriel, E.E.; Akusjärvi, S.S.; Palaniappan, A.N.; Sundaraj, V.; Mupanni, N.R.; Sperk, M.; Cheedarla, N.; Sridhar, R.; et al. Systemic Inflammation and the Increased Risk of Inflamm-Aging and Age-Associated Diseases in People Living with HIV on Long Term Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alejos, B.; Stella-Ascariz, N.; Montejano, R.; Rodriguez-Centeno, J.; Schwimmer, C.; Bernardino, J.I.; Rodes, B.; Esser, S.; Goujard, C.; Sarmento-Castro, R.; et al. Determinants of blood telomere length in antiretroviral treatment-naïve HIV-positive participants enrolled in the NEAT 001/ANRS 143 clinical trial. HIV Med. 2019, 20, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella-Ascariz, N.; Montejano, R.; Rodriguez-Centeno, J.; Alejos, B.; Schwimmer, C.; Bernardino, J.I.; Rodes, B.; Allavena, C.; Hoffmann, C.; Gisslén, M.; et al. Blood Telomere Length Changes After Ritonavir-Boosted Darunavir Combined with Raltegravir or Tenofovir-Emtricitabine in Antiretroviral-Naive Adults Infected with HIV-1. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejano, R.; Stella-Ascariz, N.; Monge, S.; Bernardino, J.I.; Pérez-Valero, I.; Montes, M.L.; Valencia, E.; Martín-Carbonero, L.; Moreno, V.; González-Garcia, J.; et al. Impact of Nucleos(t)ide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors on Blood Telomere Length Changes in a Prospective Cohort of Aviremic HIV-Infected Adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 1531–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyan, S.; Pick, N.; Mai, A.; Murray, M.C.M.; Kidson, K.; Chu, J.; Albert, A.Y.K.; Côté, H.C.F.; Maan, E.J.; Goshtasebi, A.; et al. Premature Spinal Bone Loss in Women Living with HIV is Associated with Shorter Leukocyte Telomere Length. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiau, S.; Strehlau, R.; Shen, J.; Violari, A.; Patel, F.; Liberty, A.; Foca, M.; Wang, S.; Terry, M.B.; Yin, M.T.; et al. Biomarkers of Aging in HIV-Infected Children on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. Am. J. Ther. 2018, 78, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianesin, K.; Noguera-Julian, A.; Zanchetta, M.; Del Bianco, P.; Petrara, M.R.; Freguja, R.; Rampon, O.; Fortuny, C.; Camós, M.; Mozzo, E.; et al. Premature aging and immune senescence in HIV-infected children. AIDS 2016, 30, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimnez, V.C.; Wit, F.W.N.M.; Joerink, M.; Maurer, I.; Harskamp, A.M.; Schouten, J.; Prins, M.; Van Leeuwen, E.M.M.; Booiman, T.; Deeks, S.G.; et al. T-Cell Activation Independently Associates with Immune Senescence in HIV-Infected Recipients of Long-term Antiretroviral Treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, 216–225. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, J.R.; Jarrin, I.; Martinez, A.; Siles, E.; Larrayoz, I.M.; Canuelo, A.; Gutierrez, F.; Gonzalez-Garcia, J.; Vidal, F.; Moreno, S. Shorter telomere length predicts poorer immunological recovery in virologically suppressed hiv-1-infected patients treated with combined antiretroviral therapy. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015, 68, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasa, S.; Fitch, K.V.M.; Petrow, E.B.; Burdo, T.H.; Williams, K.C.; Lo, J.; Côté, H.C.F.; Grinspoon, S.K. Soluble CD163 Is Associated with Shortened Telomere Length in HIV-Infected Patients. Am. J. Ther. 2014, 67, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malan-Müller, S.; Hemmings, S.M.J.; Spies, G.; Kidd, M.; Fennema-Notestine, C.; Seedat, S. Correction: Shorter Telomere Length—A Potential Susceptibility Factor for HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Impairments in South African Woman. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeansyah, E.; Cameron, P.U.; Solomon, A.; Tennakoon, S.; Velayudham, P.; Gouillou, M.; Spelman, T.; Hearps, A.; Fairley, C.; Smit, D.V.; et al. Inhibition of Telomerase Activity by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Nucleos(t)ide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors: A Potential Factor Contributing to HIV-Associated Accelerated Aging. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 207, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathai, S.; Lawn, S.D.; Gilbert, C.E.; McGuinness, D.; McGlynn, L.; Weiss, H.A.; Port, J.; Christ, T.; Barclay, K.; Wood, R.; et al. Accelerated biological ageing in HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: A case-control study. Aids 2013, 27, 2375–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, H.C.F.; Soudeyns, H.; Thorne, A.; Alimenti, A.; Lamarre, V.; Maan, E.J.; Sattha, B.; Singer, J.; Lapointe, N.; Money, D.M.; et al. Leukocyte Telomere Length in HIV-Infected and HIV-Exposed Uninfected Children: Shorter Telomeres with Uncontrolled HIV Viremia. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bestilny, L.J.; Gill, M.J.; Mody, C.H.; Riabowol, K.T. Accelerated replicative senescence of the peripheral immune system induced by HIV infection. AIDS 2000, 14, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolthers, K.C.; Noest, A.J.; Otto, S.A.; Miedema, F.; De Boer, R.J. Normal Telomere Lengths in Naive and Memory CD4+ T Cells in HIV Type 1 Infection: A Mathematical Interpretation. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1999, 15, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushal, S.; Landay, A.L.; Lederman, M.M.; Connick, E.; Spritzler, J.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Kessler, H.; Levine, B.L.; Louis, D.C.S.; June, C.H. Increases in T Cell Telomere Length in HIV Infection after Antiretroviral Combination Therapy for HIV-1 Infection Implicate Distinct Population Dynamics in CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells. Clin. Immunol. 1999, 92, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Palmer, L.D.; Weng, N.P.; Levine, B.L.; June, C.H.; Lane, H.C.; Hodes, R.J. Telomere length, telomerase activity, and replicative potential in HIV infection: Analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from HIV-discordant monozygotic twins. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 185, 1381–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Centeno, J.; Esteban-Cantos, A.; Montejano, R.; Stella-Ascariz, N.; De Miguel, R.; Mena-Garay, B.; Saiz-Medrano, G.; Alejos, B.; Jiménez-González, M.; Bernardino, J.I.; et al. Effects of tenofovir on telomeres, telomerase and T cell maturational subset distribution in long-term aviraemic HIV-infected adults. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, S.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D.; Akl, E.A.; Kunz, R.; Vist, G.; Brozek, J.; Norris, S.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Glasziou, P.; Debeer, H.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cawthon, R.M. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauerwein, R.W.; Roestenberg, M.; Moorthy, V.S. Experimental human challenge infections can accelerate clinical malaria vaccine development. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI H20-A2; Reference Leukocyte (WBC) Differential Count (Proportional) and Evaluation of Instrumental Methods; Approved Standard-Second Edition. Clinical And Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2007.

- Paiardini, M.; Müller-Trutwin, M. HIV-associated chronic immune activation. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 254, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukezalie, K.R.; Thumati, N.R.; Côté, H.C.F.; Wong, J.M.Y. In Vitro and Ex Vivo Inhibition of Human Telomerase by Anti-HIV Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs) but Not by Non-NRTIs. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).