Abstract

Corn silk (Stigma Maydis) has been utilized as an important herb against obesity by Chinese, Korean, and Native Americans, but its phytochemicals and mechanisms(s) against obesity have not been deciphered completely. This study aimed to identify promising bioactive constituents and mechanism of action(s) of corn silk (CS) against obesity via network pharmacology. The compounds from CS were identified using Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and were confirmed ultimately by Lipinski’s rule via SwissADME. The relationships of the compound-targets or obesity-related targets were confirmed by public bioinformatics. The signaling pathways related to obesity, protein-protein interaction (PPI), and signaling pathways-targets-bioactives (STB) were constructed, visualized, and analyzed by RPackage. Lastly, Molecular Docking Test (MDT) was performed to validate affinity between ligand(s) and protein(s) on key signaling pathway(s). We identified a total of 36 compounds from CS via GC-MS, all accepted by Lipinski’s rule. The number of 36 compounds linked to 154 targets, 85 among 154 targets related directly to obesity-targets (3028 targets). Of the final 85 targets, we showed that the PPI network (79 edges, 357 edges), 12 signaling pathways on a bubble chart, and STB network (67 edges, 239 edges) are considered as therapeutic components. The MDT confirmed that two key activators (β-Amyrone, β-Stigmasterol) bound most stably to PPARA, PPARD, PPARG, FABP3, FABP4, and NR1H3 on the PPAR signaling pathway, also, three key inhibitors (Neotocopherol, Xanthosine, and β-Amyrone) bound most tightly to AKT1, IL6, FGF2, and PHLPP1 on the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Overall, we provided promising key signaling pathways, targets, and bioactives of CS against obesity, suggesting crucial pharmacological evidence for further clinical testing.

1. Introduction

Obesity is a serious health issue worldwide because it is involved in the main causes of comorbidity and mortality, including diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, atherosclerosis, and some cancers [1,2]. Obesity is characterized by the accumulation of excessive adipose tissues in the body, leading to energy imbalance, alteration of appetite hormones, and insulin resistance [3,4]. Clinically, the criteria of obesity is the that Body Mass Index (BMI) is equal to 30.0 or higher [5]. Obesity can present at all ages, globally, a report announced that the number of overweight and obese individuals will be projected to be 1.35 billion and 573 million by 2030 [6,7].

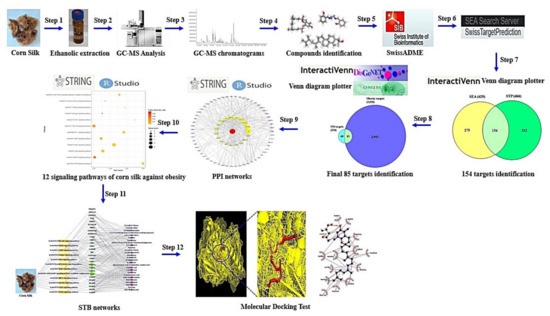

The most optimal therapeutic strategy against obesity is to inhibit the accumulation of fat in the body as well as to suppress the appetite with special medication [8,9]. At present, a representative drug of anti-obesity is Orlistat (PubChem ID: 3034010), used to decrease the absorption of fatty acid in intestine by inhibiting gastric and pancreatic lipase [10]. In addition, some medications (diethylpropion, fenfluramine, sibutramine, rimonabant) with appetite suppression efficacy have been prescribed to alleviate obesity in most countries [11]. However, most anti-obesity drugs have serious adverse events such as steatorrhea, flatulence, headache, and hypoglycemia [12]. Natural herbal plants are good resources with less side effects, compared to synthetic drugs [13]. Most recently, osmotin is characterized by a natural plant protein with antifungal efficacy, which is homologous functionally to adiponectin for preventing an excess of fatty acids in the body [14,15]. However, even though these are derived from herbal plants, protein drugs are susceptible to degradation and are not given orally due to poor bioavailability [16]. Some anti-obesity natural organic small compounds (<500g/mol) have been isolated from marine sponges: Palinurin (from Ircinia variabilis) [17], Dysidine (from Dysidea villosa) [18], Questinol and citreorosein (from Stylissa flabelliformis) [19], and Phorbaketal A (from Phorbas sp.) [20]. Other resources are land herbal plants with diverse anti-obesity organic small compounds: Curcumin (from Curcuma longa rhizome), Carnosic acid and carnosol (from Salvia officinalis leaves), Epigallocatechin 3-O gallate (from Camellia sinensis), Ursolic acid (from Actinidia arguta root), and Crocetin and crocin (from Gardenia jasminoides fruits) [21]. Currently, the majority of drug candidates in herbal plants are dependent on their main parts such as leaves, roots, and fruits. On the other hand, we suggest that medicinal utilization of agricultural substances is a good approach to identify their value. Of these, a report demonstrated that some flavonoids and phenolics from the 50% ethanolic corn silk (CS) extracts have potent anti-obesity efficacy, leading to anti-adipogenesis and lipolysis [22]. However, commonly, bioavailability improvement of phenolic compounds including flavonoids should be applied to accomplish pharmacological functions through leading-edge delivery system [23]. From this point of view, we need to establish a new methodology and concept to analyze anti-obesity on CS. At present, drug-like compound(s), target(s), and signaling pathway(s) of CS against obesity have not been reported. Thus, the studies on drug-like compounds and promising mechanism(s) of CS against obesity should be strengthened to provide pharmacological evidence to support its therapeutic application in alleviating obesity. Network pharmacology is a significant methodology to elucidate multiple components such as signaling pathways, targets, and compounds [24]. Network pharmacology is a key to decipher multiple targets of herbal bioactive compounds [25]. With the rapid progression of network pharmacology, the unveiling of interaction between multi-components and multi-targets gives us a clue to illustrate pathogenesis [26]. Moreover, the network pharmacology analysis in holistic perspectives is an effective approach to develop compounds for the treatment of metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus (DM), and obesity [25]. The aim of this study is to investigate the signaling pathways, targets, and compounds of CS against obesity. Firstly, compounds from ethanolic CS extract have been identified by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and screened by Lipinski’s rule to identify Drug Like Compounds (DLCs). Then, targets related to DLCs or obesity collected using public bioinformatics, and overlapping targets between DLCs and obesity targets were identified. Secondly, the protein-protein interaction (PPI) based on overlapping targets was constructed by RPackage. Next, a bubble chart used to visualize the Rich factor on overlapping targets was built by RPackage. Thirdly, relationships between signaling pathways, targets, and DLCs were visualized by RPackage. Finally, Molecular Docking Test (MDT) was performed to understand the best affinity between targets and DLCs on key signaling pathways. The concise workflow is exhibited in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research process of network pharmacology analysis of CS against obesity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Extracts Preparation

Corn silk (CS) were collected from (latitude: 36.683084, longitude: 128.512617), Gyeongsangbuk-do, Korea, in July 2021. The CS were dried in a shady zone at room temperature (20–22 °C) for 7 days, and dried CS powder was made using an electric blender. Approximately 20 g of CS powder was soaked in 1000 mL of 100% ethyl alcohol (Daejung, Siheung city, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) for 15 days and repeated 3 times to achieve a high yield rate. The solvent extract was collected, filtered with Whatman filter paper No. 1 (Whatman, Model no. WF1-1850, UK Maidstone) and evaporated using a vacuum evaporator (IKA- RV8, Staufen city, Germany) at 40 °C. The yield after evaporating was 1.98 g (Yield rate: 0.99%), which was calculated as follows:

Yield (%) = (Dried CS weight/Evaporated extraction weight) × 100

2.2. GC-MS Analysis Condition

Agilent 7890A (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to perform GC-MS analysis. GC was equipped with a DB-5 (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) capillary column (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Initially, the instrument was maintained at a temperature of 100 °C for 2.1 min. The temperature rose to 300 °C at a rate of 25 °C/min and was maintained for 20 min. Injection port temperature and helium flow rate were ensured as 250 °C and 1.5 mL/min, respectively. The ionization voltage was 70 eV. The samples were injected in split mode at 10:1. The MS scan range was set at 35–900 (m/z). The fragmentation patterns of mass spectra were compared with those stored in the W8N05ST Library MS database (analyzed 7 September 2021). The percentage of each compound was calculated from the relative peak area of each compound in the chromatogram [27].

2.3. GC-MS Compounds in CS and Screening of DLCs

The chemical constituents in CS were detected via GC-MS analysis, which were input into PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 9 September 2021) to identify SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) format. The screening of DLCs is based on Lipinski’s rule via SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) (accessed on 9 September 2021). Additionally, topological polar surface area (TPSA) to measure cell permeability of compounds was identified by SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/, accessed on 9 September 2021). Commonly, its cut-off value to evaluate cell permeability is typically less than 140 Å2 [28].

2.4. Identification of Target Proteins Associated with Bioactives or Obesity

The bioactives confirmed by Lipinski’s rule put the SMILE format into two two public cheminformatics: Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA) (accessed on 10 September 2021) [29] and SwissTargetPrediction (STP) (accessed on 10 September 2021) [30] with “Homo Sapiens” mode. The relationship between target proteins and bioactives were obtained by the two cheminformatics, which demonstrated their use as significant tools to be validated experimentally: A total of 80% out of the novel drug candidates line up with the SEA result, and the promising target proteins of cudraflavone C were identified through STP, thereby, its biological activities were validated by the experiment [31,32]. Altogether, we confirmed that novel potential ligands and target proteins would be identified using the validated data. The target proteins related to obesity were collected by two public bioinformatics DisGeNET (https://www.disgenet.org/search, accessed on 13 September 2021) and OMIM (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim) (accessed 13 September 2021). The overlapping target proteins between DLCs from CS and obesity-related target proteins were identified and visualized on InteractiVenn [33]. Then, we visualized it on Venn Diagram Plotter.

2.5. PPI Construction of Final Target Proteins and Identification of Rich Factor

The interaction of the final overlapping target proteins was identified by STRING analysis (https://string-db.org/, accessed 14 September 2021) [34]. The number of nodes and edges were identified by PPI construction and thus, signaling pathways involved in overlapping target proteins were explicated by the RPackage bubble chart illustration. On the bubble chart, two key signaling pathways of CS against obesity were finalized.

2.6. The Construction of STB Network

The STB networks were visualized as a size map, based on a degree of value. In the network map, green rectangles (nodes) represented the signaling pathways; yellow triangles (nodes) represented the target proteins; red circles (nodes) represented the bioactives. The size of the yellow triangles stood for the number of relationships with signaling pathways; the size of red circles stood for the number of relationships with target proteins. The assembled network was constructed by utilizing RPackage.

2.7. Bioactives and Target Proteins Preparation for MDT

The bioactives related to the two key signaling pathways were converted. sdf from PubChem into. pdb format utilizing Pymol, and thus they were converted into. pdbqt format via Autodock. The number of the six proteins on the PPAR signaling pathway, i.e., PPARA (PDB ID: 3SP6), PPARD (PDB ID: 5U3Q), PPARG (PDB ID: 3E00), FABP3 (PDB ID: 5HZ9), FABP4 (PDB ID: 3P6D), and NR1H3 (PDB ID: 2ACL), and the number of the seven proteins on PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, i.e., AKT1 (PDB ID: 3O96), IL6 (PDB ID: 4NI9), VEGFA (PDB ID: 3V2A), PRKCA (PDB ID: 3IW4), FGF1 (PDB ID: 3OJ2), FGF2 (PDB ID: 1IIL), and PHLPP1 (not available in the PDB) were identified on STRING via RCSB PDB (https://www.rcsb.org/, accessed 16 September 2021). The proteins were chosen as. PDB format were converted into. pdbqt through Autodock (http://autodock.scripps.edu, accessed on 17 September 2021).

2.8. MDT of Bioactives on Target Proteins Related to Two Key Signaling Pathways

The ligand molecules were docked with target proteins using autodock4 by setting-up 4 energy range and 8 exhaustiveness as default to obtain 10 different poses of ligand molecules [35]. The center of each target protein on PPAR signaling pathway was PPARA (x = 8.006, y = −0.459, z = 23.392)), PPARD (x = 39.265, y = −18.736, z = 119.392), PPARG (x = 2.075, y = 31.910, z = 18.503), FABP3 (x = −1.215, y = 46.730, z = −15.099), FABP4 (x = 7.693, y = 9.921, z = 14.698).

The center of each target protein on PI3K-Akt signaling pathway was Akt1 (x = 6.313, y = −7.926, z = 17.198), IL6 (x = 11.213, y = 33.474, z = 11.162), VEGFA (x = 38.009, y = −10.962, z = 12.171), PRKCA (x = −14.059, y = 38.224, z = 32.319), FGF1 (x = 9.051, y = 22.527, z = −0.061), FGF2 (x = 26.785, y = 14.360, z = −1.182), PHLPP1 (x = −3.881, y = 1.398, z = 2.661). The active site’s grid box size was x = 40 Å, y = 40 Å, z = 40 Å. The detailed information of 2D binding was identified by LigPlot+ 2.2 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/software/LigPlus/, accessed 18 September 2021) [36]. After MDT, bioactives with the lowest Gibbs free energy were selected to depict the bioactive-protein complex in Pymol.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Properties of Chemical Compounds from Corn Silk (CS)

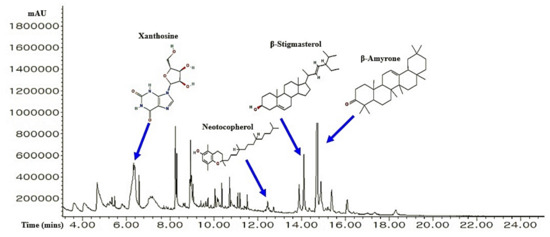

A total of 36 chemical compounds from CS were detected through GC-MS analysis (Figure 2), and compound name, retention time, peak area, PubChem ID, and taxonomic classification are presented in Table 1. All 36 chemical compounds were accepted by Lipinski’s rule (Molecular Weight ≤ 500 g/mol; Moriguchi octanol-water partition coefficient ≤ 4.15; Number of Nitrogen or Oxygen ≤ 10; Number of NH or OH ≤ 5), including TPSA value (< 140 Å2) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

A typical GC-MS peaks of CS ethanolic extract and the number of four key bioactives.

Table 1.

A list of the detected 36 bioactives from CS through GC-MS.

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties of 36 bioactives for Lipinski’s rule, bioavailability, and cell membrane permeability.

3.2. Identification of Overlapping Target Proteins between SEA and STP Linked to 36 Compounds

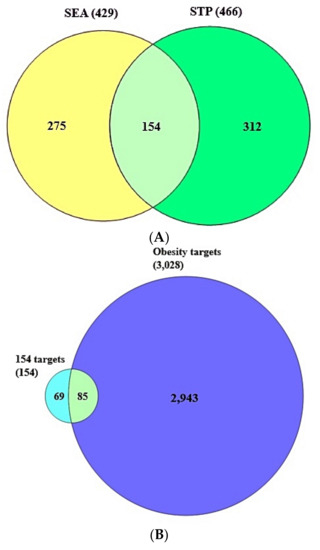

A total of 429 target proteins from SEA and 466 target proteins from STP linked to the abovementioned 36 compounds were identified through SMILES format (Supplementary Table S1). The results of the Venn diagram exhibited that 154 overlapping target proteins were overlapped between SEA and STP public databases (Supplementary Table S1) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) A total of 154 overlapping targets between SEA (429 targets) and STP (466 targets). (B) A total of 85 final targets between the 154 overlapping targets and obesity-related targets (3028 targets).

3.3. The Final Overlapping Target Proteins between Obesity-Related Target Proteins and the 154 Overlapping Target Proteins

As shown in Supplementary Table S2, a total of 3028 target proteins associated with obesity were retrieved by DisGeNet and OMIM databases. The Venn diagram displayed that a total of 85 target proteins overlapped between obesity related to 3028 target proteins and 154 overlapping target proteins (Supplementary Table S2) (Figure 3B).

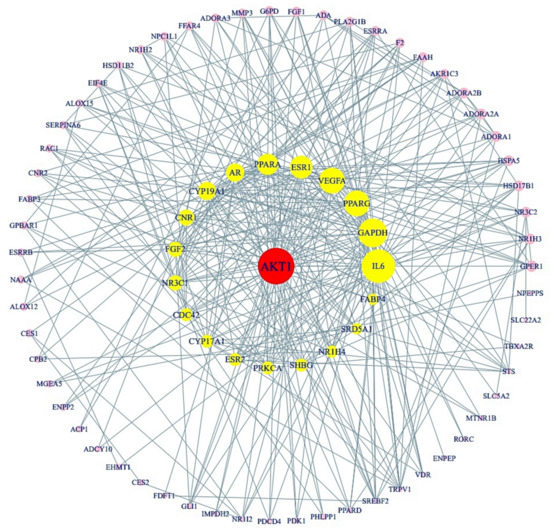

3.4. Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) from Final 85 Target Proteins

Using STRING analysis, 79 out of 85 target proteins were correlated closely with each other with 79 nodes and 357 edges (Figure 4). The eliminated 6 target proteins (RNASE2, SLC22A6, GSTK1, PAM, OXER1, and THRA) did not interact with the 85 target proteins. In the PPI network, the AKT1 target protein had the greatest degree of centrality (43) and was considered as the hub target protein (Table 3).

Figure 4.

PPI networks (79 nodes, 357 edges). The size of the circle represents degree of values.

Table 3.

The degree value of 79 targets in PPI.

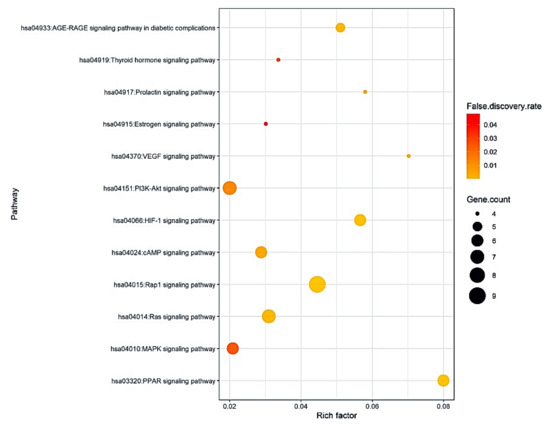

3.5. The 12 Signaling Pathways and Identification of Two Key Pathways of CS against Obesity

The results of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis showed that 85 target proteins were related directly to 12 signaling pathways (False Discovery Rate < 0.05). The 12 signaling pathways were implicated with occurrence and development of obesity, suggesting that these pathways might be important signaling pathways of CS against obesity. The description of the 12 signaling pathways was represented in Table 4. In addition, a bubble chat suggested that both the PPAR signaling pathway with the highest rich factor and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway with the lowest rich factor might be key signaling pathways of CS against obesity (Figure 5).

Table 4.

Targets in 12 signaling pathways enrichment associated with obesity.

Figure 5.

A bubble chart of 12 signaling pathways associated with progression and development of obesity.

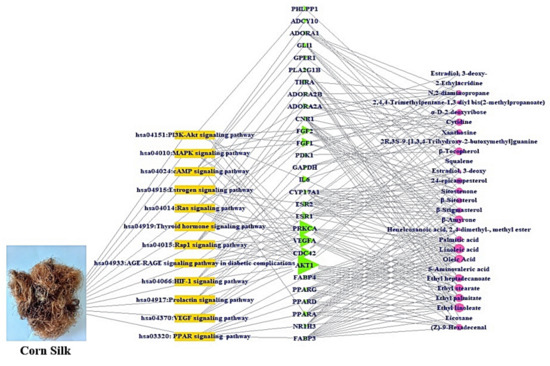

3.6. The Construction of a Signaling Pathway-Target Protein-Bioactive (STB) Networks

A signaling pathway-target protein- bioactive (STB) network of CS was exhibited in Figure 6. There were 12 signaling pathways, 28 targets, and 27 bioactives (67 nodes, 239 edges). The nodes stood for a total number of each component: signaling pathways, target proteins, and bioactives. The edges represent relationships of the three components. The STB network indicated that each component of the network is a significant element with therapeutic efficacy against obesity. The AKT1 is the uppermost target with the greatest degree value (11) among 12 signaling pathways (Table 5). Noticeably, a sole signaling pathway not to be connected to AKT1 was the PPAR signaling pathway with the highest rich factor.

Figure 6.

STB networks (67 nodes, 239 edges). Yellow rectangle: signaling pathway; green triangle: target; pink circle: bioactive.

Table 5.

The degree value of 28 targets in STB.

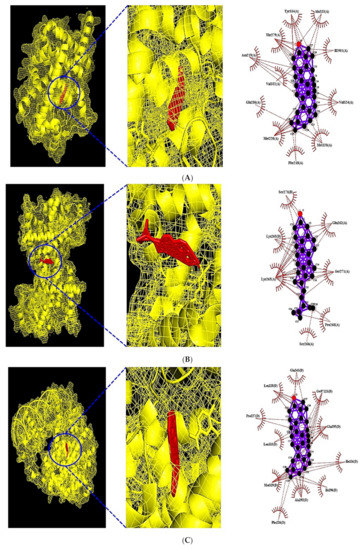

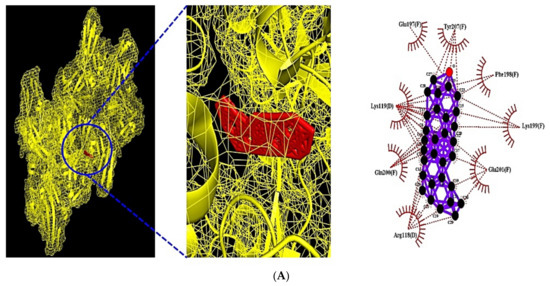

3.7. MDT of 6 Target Proteins, 2 Key Bioactives, and 9 Positive Controls on PPAR Signaling Pathway

Through MDT analysis, it was unveiled that PPARA(PDB ID: 3SP6) was associated with 9 bioactives: (1)β-Amyrone, (2) Squalene, (3) Ethyl palmitate, (4) Heneicosanoic, 2,4-dimethyl-,methyl ester, (5) Oleic acid, (6) Ethyl linoleate, (7) Palmitic acid, (8) Linoleic acid, and (9) (Z)-9-Hexadecenal, PPARD (PDB ID: 5U3Q) was related to 8 bioactives: (1) β-Stigmasterol, (2) β-Sitosterol, (3) Heneicosanoic, 2,4-dimethyl-,methyl ester, (4) Ethyl linoleate, (5) Linoleic acid, (6) Oleic acid, (7) Palmitic acid, and (8) (Z)-9-Hexadecenal, PPARG (PDB ID: 3E00) was connected to 6 bioactives: (1) β-Amyrone, (2) Ethyl linoleate, (3) Linoleic acid, (4) Oleic acid, (5) Palmitic acid, and (6) (Z)-9-Hexadecenal, FABP3 (PDB ID: 5HZ9) was associated with 12 bioactives: (1) β-Amyrone, (2) Heneicosanoic, 2,4-dimethyl-,methyl ester, (3) Eicosane, (4) Ethyl stearate, (5) Ethyl heptacecanoate, (6) Ethyl linoleate, (7) Ethyl palmitate, (8) Linoleic acid, (9) (Z)-9-Hexadecenal, (10) Oleic acid, (11) Palmitic acid, and (12) 5-Aminovaleric acid, FABP4 (PDB ID: 3P6D) was related to 11 bioactives: (1) β-Amyrone, (2) Heneicosanoic, 2,4-dimethyl-,methyl ester, (3) Ethyl stearate, (4) Ethyl palmitate, (5) Ethyl heptacecanoate, (6) Ethyl linoleate, (7) 5-Aminovaleric acid, (8) Oleic acid, (9) Linoleic acid, (10) Palmitic acid, and (11) (Z)-9-Hexadecenal, and NR1H3 (PDB ID: 2ACL) was connected to 9 bioactives: (1) β-Amyrone, (2) β-Stigmasterol, (3) β-Sitosterol, (4) Estradiol, 3-deoxy, (5) Sitostenone, (6) 24-epicampesterol, (7) Ethyl linoleate, (8) Linoleic acid, and (9) Oleic acid.

It was observed that β-Amyrone had the highest affinity on five out of six target proteins: −16.1 kcal/mol on PPARA (PDB ID: 3SP6), −14.0 kcal/mol on PPARG (PDB ID: 3E00), −21.5 kcal/mol on FABP3 (PDB ID: 5HZ9), −13.2 kcal/mol on FABP4 (PDB ID: 3P6D), and −15.4 kcal/mol on NR1H3 (PDB ID: 2ACL). Interestingly, the highest affinity on PPARD (PDB ID: 5U3Q) was β-Stigmasterol with −10.8 kcal/mol. The docking detail information is enlisted in Table 6. Additionally, MDT was performed to compare bioactives with positive controls (Table 7). The results of MDT suggested that β-Amyrone on PPARA (PDB ID: 3SP6), PPARG (PDB ID: 3E00), and NR1H3 (PDB ID: 2ACL) had better affinity than the current positive controls. Moreover, it has been shown that β-Stigmasterol on PPARD (PDB ID: 5U3Q) had greater affinity than Cardarine used as an anti-obesity drug. The other two target proteins were not positive controls compared with β-Amyrone. Collectively, both β-Amyrone and β-Stigmasterol of CS on obesity were potential ligands to activate the PPAR signaling pathway. Its complex figures are depicted in Figure 7.

Table 6.

Binding energy and interactions of potential bioactives on the PPAR signaling pathway.

Table 7.

Binding energy and interactions of potential bioactives on the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway.

Figure 7.

(A) MDT of β-Amyrone (PubChem ID: 612782) on PPARA (PDB ID: 3SP6). (B) MDT of β-Stigmasterol (PubChem ID: 6432745) on PPARD (PDB ID: 5U3Q). (C) MDT of β-Amyrone (PubChem ID: 612782) on PPARG (PDB ID: 3E00). (D) MDT of β-Amyrone (PubChem ID: 612782) on FABP3 (PDB ID: 5HZ9). (E) MDT of β-Amyrone (PubChem ID: 612782) on FABP4 (PDB ID: 3P6D). (F) MDT of β-Amyrone (PubChem ID: 612782) on NR1H3 (PDB ID: 2ACL).

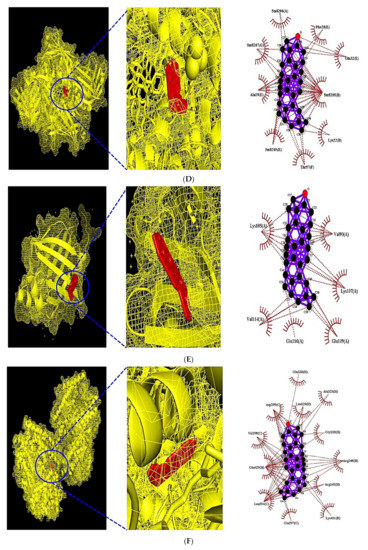

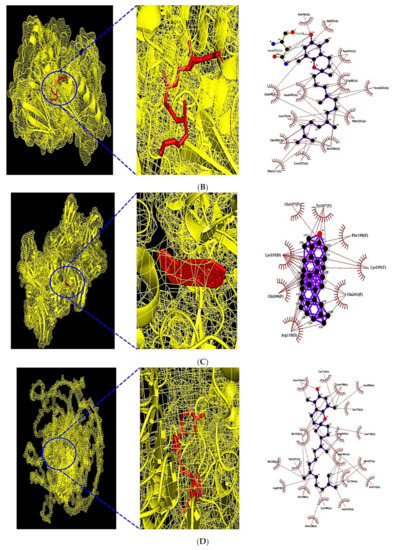

3.8. MDT of 7 Target Proteins, 3 Key Bioactives, and 15 Positive Controls on PI3K-Akt1 Signaling Pathway

Through MDT analysis, it was revealed that AKT1 (PDB ID: 3O96) was related to a sole bioactive: (1) Neotocopherol, IL6 (PDB ID: 4NI9) was associated with 3 bioactives: (1) Xanthosine, (2) 2-Ethylacridine, and (3) Linoleic acid, VEGFA (PDB ID: 3V2A) was connected to (1) Ethyl palmitate, (2) Ethyl heptadecanoate, (3) Ethyl stearate, (4) Ethyl linoleate, and (5) α-D-2-deoxyribose, PRKCA (PDB ID: 3IW4) was linked to 9 bioactives: (1) Ethyl palmitate, (2) Ethyl heptadecanoate, (3) Ethyl linoleate, (4) 2,4,4-Trimethylpentane-1,3-diyl bis(2-methylpropanoate), (5) Linoleic acid, (6) Ethyl stearate, (7) (Z)-9-Hexadecenal, (8) Palmitic acid, and (9) Oleic acid, FGF1 (PDB ID: 3OJ2) was related to 4 bioactives: (1) Sitostenone, (2) 24-epicampesterol, (3) Cytidine, and (4) α-D-2-deoxyribose, FGF2 (PDB ID: 1IIL) was associated with 7 bioactives: (1) β-Amyrone, (2) β-Stigmasterol, (3) Sitostenone, (4) 24-epicampesterol, (5) β-Sitosterol, (6) Cytidine, and (7) α-D-2-deoxyribose, and PHLPP1 was linked to a sole bioactive: (1) Neotocopherol. It was observed that Neotocopherol on AKT1 (PDB ID: 3O96), Xanthosine on IL6 (PDB ID: 4NI9), and β-Amyrone on FGF2 (PDB ID: 1IIL) had the highest affinity among bioactives from CS as well as better affinity than positive controls. The docking detail information is enlisted in Table 8. On the other hand, both Ethyl palmitate had the highest affinity on VEGFA (PDB ID: 3V2A), Sitostenone had the highest affinity on FGF1 (PDB ID: 3OJ2), and lower affinity than BAW2881 and Suramin, which were used as the positive controls, respectively. At present, it was observed that PHLPP1 was not enlisted in PDB, and had valid affinity with β-Amyrone (−7.2 kcal/mol). The detailed affinity value was exhibited in Table 9. The Autodock program was able to assemble active (Gibbs free energy of binding < −6.0 kcal/mol), suggesting that it had highly predictive affinity [37]. Comprehensively, Neotocopherol, Xanthosine, and β-Amyrone of CS on obesity were potential ligands to inhibit PI3K-Akt1 signaling pathway. Its complex figures are depicted in Figure 8.

Table 8.

Comparative binding energy between the most stable bioactive(s) and positive control(s) on the PPAR signaling pathway.

Table 9.

Comparative binding energy between the most stable bioactive(s) and positive control(s) on the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway.

Figure 8.

(A) MDT of Neotocopherol (PubChem ID: 86052) on AKT1 (PDB ID: 3O96). (B) MDT of Xanthosine (PubChem ID: 64959) on IL6 (PDB ID: 4NI9). (C) MDT of β-Amyrone (PubChem ID: 612782) on FGF2 (PDB ID: 1IIL). (D) MDT of Neotocopherol (PubChem ID: 86052) on PHLPP1.

4. Discussion

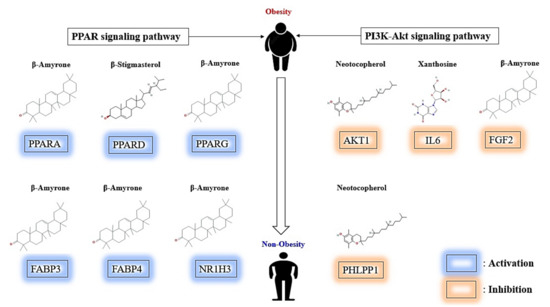

β-Amyrone, out of 36 bioactives from CS, was associated with the number of 6 target proteins on both the PPAR signaling pathway and the PI3K-Akt1 signaling pathway, considered as key signaling pathways of CS on obesity. Noticeably, it was unveiled that β-Amyrone (a triterpenoid derivative) on PPARA (PDB ID: 3SP6), PPARG (PDB ID: 3E00) and FGF2 (PDB ID: 1IIL) had better affinity than the positive controls. Likewise, the β-Stigmasterol on PPARD (PDB ID: 5U3Q) had better affinity than Cardarine, which is used as an anti-obesity drug. A report demonstrated that α,β-amyrin, as a triterpenoid derivative homologous to β-Amyrone, inhibits adipocyte differentiation by inactivating PPARG [38]. Another animal test showed that treatment of α,β-amyrin had a significant decrease in the level of blood glucose, serum triglyceride, and total cholesterol [39]. It implies that β-Amyrone might also be a potential ligand to exert an anti-adipogenic effect. A previous study showed that Stigmasterol significantly alleviated high-fat western-style fat (HFWD) induced fatty liver and metabolic disorders, including an increased level of hepatic total lipids, cholesterol, and triacylglycerols [40]. Furthermore, a report demonstrated that the activator of PPARA, PPARD, and PPARG is of great anti-obesity therapeutics due to the regulation of fat and gluconeogenesis [41]. Additionally, a report showed that the NR1H3 agonist makes good efficacy on the enhancement of reverse cholesterol transport, elevation of glucose uptake, and blocking of pro-inflammatory factors [42]. Additionally, Neotocopherol related directly to AKT1, considered as a hub target, had better affinity than two positive controls (AT13148, Afuresertib). There is a noticeable animal study indicating that knock-out of Akt1 elevates energy expenditure and, conversely, decreases the body weight of mice [43]. Another research shows that Akt1 null mice improved their insulin sensitivity and, thereby, elevated insulin secretion [44]. It could be speculated that the inhibitor of Akt1 might play a significant role to attenuate metabolic disorders, including obesity. The Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGFA) is overexpressed in obese subjects while inhibitors of VEGF induced anti-proliferation of adipocytes induces weight loss [45,46]. The Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 (FGF2) is elevated in the context of obesity, the disruption of which leads to an increase of thermogenesis with higher energy expenditure and stable lipid maintenance [47,48]. It implies that the inhibitors of VEGFA and FGF2 might be potential ligands against obesity. The STB networks exhibited that the therapeutic effect of CS on obesity was directly associated with 27 bioactives. The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of 27 bioactives shows that 12 signaling pathways were related to the occurrence and development of obesity, suggesting that these signaling pathways might be the pharmacological mechanisms of ABBR against obesity. The relationships of 12 signaling pathway with obesity were shortly discussed as follows. Advanced Glycation End Product-Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Product (AGE-RAGE) signaling pathway in diabetic complications: the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway influences the oxidative stress related to a diabetic complication, the inhibition of which is a therapeutic strategy for obesity [49,50]. Thyroid hormone signaling pathway: The elevated thyroid hormone levels attenuate the sensitivity of insulin to dampen hepatic glucose production and accelerates the glucose uptake in muscle cells [51]. It has been implicated that excessive thyroid hormone level leads to metabolic disorders, including obesity. Prolactin signaling pathway: It has been documented that prolactin level is increased in obese (17.75 ± 9.15 μg/L) subjects by comparison with subjects of normal weight (13.57 ± 9.03 μg/L) [52]. Estrogen signaling pathway: There is an observational outcome that estrogens play a crucial role in the occurrence of progression of female obesity, primarily via thyroid dysfunction and control of the hypothalamus [53]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathway: A report shows that inactivation of VEGF enhances the insulin sensitivity in high-fat-diet mice, which is an efficient approach to ameliorate obesity [54]. Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase–Protein Kinase B (PI3K-Akt) signaling pathway: A report demonstrated that inactivation of PI3K alleviates morbid overweight in obese mice and monkeys, indicating that the inhibitors did not induce drug resistance and adverse effects [55]. Additionally, alliin (40 μg/mL) as an inhibitor of Akt, inhibits adipogenesis by downregulating Akt [56]. Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1) signaling pathway: The attenuation of HIF1-α alleviates glucose intolerance caused by obesity through diminishing Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) [57]. Cyclic Adenosine MonoPhosphate (cAMP) signaling pathway: the elevation of cAMP level is linked to adipocyte differentiation as a negative factor of severe overweight, berberine known as cAMP inhibitor alleviates anti-obesity by lowering blood glucose, lipid, and body weight [58]. Repressor activator protein 1 (Rap1) signaling pathway: from two groups of mice fed a high fat diet, mice with functional Rap1 gain weight, in contrast, mice that deleted Rap1 remarkably reduced their body weight [59]. Renin-Angiotensin System (RAS) signaling pathway: a research shows that erucin is a bioactive compound isolated from broccoli, known as a Ras inhibitor, and has potent anti-obesity efficacy by inhibiting adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cell line [60]. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway: MAPK, also known as ERK, the inhibition of which is a significant target to alleviate obesity via inhibiting adipogenic differentiation on MAPK signaling pathway [61]. Another research demonstrated that wedelolactone with inhibitory effect on MAPK signaling pathway ablates the adipocyte differentiation [62]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) signaling pathway: a report demonstrated that PPAR activator is therapeutic strategy to alleviate obesity via burning fat brown adipose tissue (BAT), thereby diminishing the fat overload [63].

Besides, our study provided that 11 out 12 signaling pathways associated with AKT1 might have inhibitory effects for the alleviation of obesity, including PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. In contrast, PPAR signaling pathway of CS on obesity is a sole activator mechanism, not related to AKT1. According to a bubble chart, PPI, and STB networks results, we identified 2 signaling pathways, 13 targets, and 27 bioactives, and thus MDT verified that 4 bioactives (β-Amyrone, β-Stigmasterol, Neotocopherol, and Xanthosine) among 27 bioactives could stably bind to the targets, indicating that CS might activate the PPAR signaling pathway, and inactivate PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Moreover, the final 4 bioactives have better stable affinity than the positive controls. To sum things up, we adopted 2 key signaling pathways (PPAR signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway), 10 targets (PPARA, PPARD, PPARG, FABP3, FABP4, NR1H3, AKT1, IL6, FGF2, and PHLPP1), and 4 bioactives (β-Amyrone, β-Stigmasterol, Neotocopherol, and Xanthosine) (see Figure 9). We removed three complexes (VEGFA-Ethyl palmitate, PRKCA- Ethyl palmitate, and FGF1-Sitostenone) with lower affinity than the positive controls. Hence, in the viewpoint of network pharmacology, this research elucidates promising signaling pathways, targets, and bioactives of CS against obesity, supporting a pharmacological basis for additional experimental validation.

Figure 9.

Summary representation of key findings in the study.

5. Conclusions

Overall, this study demonstrated the potential signaling pathways, targets, and bioactives in treating obesity based on network pharmacology analysis. We identified 2 key signaling pathways (PPAR signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway), 13 targets (PPARA, PPARD, PPARG, FABP3, FABP4, NR1H3, AKT1, IL6, VEGFA, PRKCA, FGF1, FGF2, and PHLPP1), and 4 bioactives (β-Amyrone, β-Stigmasterol, Neotocopherol, and Xanthosine) of CS against obesity. A total of 10 out of 13 targets have better affinity or valid value in comparison with the positive controls: PPARA, PPARD, PPARG, FABP3, FABP4, NR1H3, AKT1, IL6, FGF2, and PHLPP1. The AKT1 with the highest degree value was considered as the uppermost target, Neotocopherol was a critical bioactive that was bound most stably to AKT1. Notably, β-Amyrone as an activator could dock well with PPARA, PPARG, FABP3, FABP4, NR1H3 on the PPAR signaling pathway, in contrast, β-Amyrone as an inhibitor could dock stably with FGF2 on the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. This study shows that β-Amyrone of CS might have dual-efficacy to alleviate obesity. To conclude, we described the therapeutic evidence to expound key signaling pathways, targets, and bioactives of CS against obesity. However, there are still limitations to our analysis, which needs to be further improved, through either in vitro or in vivo. Last but not least, our analysis did not consider the expression of the target gene practically after treating the selected compounds, which should be implemented in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cimb43030133/s1, Table S1: The 154, 466, and 154 targets from SEA, STP, and overlapping targets between SEA and STP, respectively. Table S2: The number of 3028 targets associated with obesity and the number of 85 final targets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, data curation, writing—original draft, K.-K.O.; software, investigation, data curation, K.-K.O. and M.A.; validation, writing—review and editing, M.A.; supervision, project administration, D.-H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

International Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and

its Supplementary Materials).

Acknowledgments

This research was acknowledged by the Department of Bio-Health Convergence, College of Biomedical Science, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 24341, Republic of Korea.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest declared.

Abbreviations

| cAMP | cyclic Adenosine MonoPhosphate; |

| CS | Corn Silk; |

| DLCs | Drug Like Compounds (DLCs); |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus; |

| FGF1 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 1; |

| FGF2 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 2; |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry; |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-Like Peptide-1; |

| HIF-1 | Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1; |

| HFWD | High-Fat Western-style fat Diet; |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase; |

| MDT | Molecular Docking Test; |

| PI3K-Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase–Protein Kinase B; |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor; |

| PPARA | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha; |

| PPARD | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Delta; |

| PPARG | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma; |

| PPI | Protein Protein Interaction (PPI); |

| Rap1 | Repressor activator protein 1; |

| RAS | Renin Angiotensin System; |

| SEA | Similarity Ensemble Approach; |

| STB | Signaling pathways-Targets-Bioactives; |

| STP | SwissTargetPrediction; |

| TPSA | Topological Polar Surface Area; |

| VEGFA | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A. |

References

- González Jiménez, E. Obesity: Etiologic and pathophysiological analysis. Endocrinología y Nutrición 2013, 60, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.K.; Adnan, M.; Ju, I.; Cho, D.H. A network pharmacology study on main chemical compounds from Hibiscus cannabinus L. leaves. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 11062–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racette, S.B.; Deusinger, S.S.; Deusinger, R.H. Obesity: Overview of Prevalence, Etiology, and Treatment. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Lancha, L.O.; Campos-Ferraz, P.L.; Lancha, A.H. Junior Obesity: Considerations about etiology, metabolism, and the use of experimental models. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2012, 5, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczmarski, R.J.; Flegal, K.M. Criteria for definition of overweight in transition: Background and recommendations for the United States. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjaja, N.A.; Prihaningtyas, R.A. Determinants of Food Choice in Obesity. Indones. J. Public Health 2020, 15, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, T.; Yang, W.; Chen, C.S.; Reynolds, K.; He, J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barja-Fernandez, S.; Leis, R.; Casanueva, F.; Seoane, L. Drug development strategies for the treatment of obesity: How to ensure efficacy, safety, and sustainable weight loss. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2014, 8, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.J.; Tschöp, M.H.; Wilding, J.P.H. Anti-obesity drugs: Past, present and future. Dis. Models Mech. 2012, 5, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, D.A.M.; Yanovski, D.J.A.; Calis, D.K.A. Orlistat, a New Lipase Inhibitor for the Management of Obesity. Pharmacotherapy 2000, 20, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Cheung, B.M.Y. Pharmacotherapy for obesity. Br. J. Clin.Pharmacol. 2009, 68, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P. Anti-obesity drugs: A review about their effects and their safety. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2012, 11, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Onakpoya, I.J.; Posadzki, P.; Eddouks, M. The safety of herbal medicine: From prejudice to evidence. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 316706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T. Therapeutic properties of the new phytochemical osmotin for preventing atherosclerosis. Vessel Plus 2020, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.G.; Kim, M.W.; Jo, M.H.; bin Abid, N.; Kim, M.O. Adiponectin homolog osmotin, a potential anti-obesity compound, suppresses abdominal fat accumulation in C57BL/6 mice on high-fat diet and in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 43, 2422–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaji, J.; Patole, V. Protein and Peptide Drug Delivery: Oral Approaches. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 70, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.; Pérez, D.I.; Martínez, A.; Castro, A.; Gómez, G.; Fall, Y. The first enantioselective synthesis of palinurin. Chem. Commun. 2009, 22, 3252–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, H.; Shen, X. A sesquiterpene quinone, dysidine, from the sponge Dysidea villosa, activates the insulin pathway through inhibition of PTPases. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2009, 30, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noinart, J.; Buttachon, S.; Dethoup, T.; Gales, L.; Pereira, J.A.; Urbatzka, R.; Freitas, S.; Lee, M.; Silva, A.M.S.; Pinto, M.M.M.; et al. A New Ergosterol Analog, a New Bis-Anthraquinone and Anti-Obesity Activity of Anthraquinones from the Marine Sponge-Associated Fungus Talaromyces stipitatus KUFA 0207. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.J.; Lee, K.T.; Rho, J.R.; Choi, J.H. Phorbaketal A, Isolated from the Marine Sponge Phorbas sp., Exerts Its Anti-Inflammatory Effects via NF-κB Inhibition and Heme Oxygenase-1 Activation in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Macrophages. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 7005–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karri, S.; Sharma, S.; Hatware, K.; Patil, K. Natural anti-obesity agents and their therapeutic role in management of obesity: A future trend perspective. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 110, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiittianan, R.; Chayopas, P.; Rattanathongkom, A.; Tippayawat, P.; Sutthanut, K. Anti-obesity potential of corn silks: Relationships of phytochemicals and antioxidation, anti-pre-adipocyte proliferation, anti-adipogenesis, and lipolysis induction. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 23, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme, P.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Espino, J.; Garrido, M. Plant Phenolics: Bioavailability as a Key Determinant of Their Potential Health-Promoting Applications. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Bi, F.; Sun, Z. A network pharmacology approach to determine the underlying mechanisms of action of Yishen Tongluo formula for the treatment of oligoasthenozoospermia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yuan, G.; Pan, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, H. Network Pharmacology Studies on the Bioactive Compounds and Action Mechanisms of Natural Products for the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Cai, Y.; Cai, X.; Zheng, X.; Cao, D.; Ye, F.; Xiang, Z. A Network Pharmacology Approach to Understanding the Mechanisms of Action of Traditional Medicine: Bushenhuoxue Formula for Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.K.; Adnan, M.; Cho, D.H. A network pharmacology analysis on drug-like compounds from Ganoderma lucidum for alleviation of atherosclerosis. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsson, P.; Kihlberg, J. How Big Is Too Big for Cell Permeability? J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1662–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, M.J.; Roth, B.L.; Armbruster, B.N.; Ernsberger, P.; Irwin, J.J.; Schoichet, B.K. Relating protein pharmacology by ligand chemistry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: Updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Chaput, L.; Villoutreix, B.O. Virtual screening web servers: Designing chemical probes and drug candidates in the cyberspace. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, 1790–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, H.-C.; Chung, F.F.-L.; Lim, K.-H.; Yap, V.A.; Bradshaw, T.D.; Hii, L.-W.; Tan, S.-H.; See, S.-J.; Tan, Y.-F.; Leong, C.-O.; et al. Cudraflavone C Induces Tumor-Specific Apoptosis in Colorectal Cancer Cells through Inhibition of the Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase (PI3K)-AKT Pathway. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heberle, H.; Meirelles, G.V.; da Silva, F.R.; Telles, G.P.; Minghim, R. InteractiVenn: A web-based tool for the analysis of sets through Venn diagrams. BMC Bioinform. 2015, 16, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: Protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanal, P.; Patil, B.M.; Chand, J.; Naaz, Y. Anthraquinone Derivatives as an Immune Booster and their Therapeutic Option Against COVID-19. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2020, 10, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laskowski, R.A.; Swindells, M.B. LigPlot+: Multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Modeling 2011, 51, 2778–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shityakov, S.; Förster, C. In silico predictive model to determine vector-mediated transport properties for the blood–brain barrier choline transporter. Adv. Appl. Bioinform. Chem. AABC 2014, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Melo, K.M.; de Oliveira, F.T.B.; Costa Silva, R.A.; Gomes Quinderé, A.L.; Marinho Filho, J.D.B.; Araújo, A.J.; Barros Pereira, E.D.; Carvalho, A.A.; Chaves, M.H.; Rao, V.S.; et al. α, β-Amyrin, a pentacyclic triterpenoid from Protium heptaphyllum suppresses adipocyte differentiation accompanied by down regulation of PPARγ and C/EBPα in 3T3-L1 cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1860–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.A.; Frota, J.T.; Arruda, B.R.; de Melo, T.S.; de Castro Brito, G.A.; Chaves, M.H.; Rao, V.S. Antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of α, β-amyrin, a triterpenoid mixture from Protium heptaphyllum in mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Dai, Z.; Liu, A.B.; Huang, J.; Narsipur, N.; Guo, G.; Kong, B.; Reuhl, K.; Lu, W.; Luo, Z.; et al. Intake of stigmasterol and β-sitosterol alters lipid metabolism and alleviates NAFLD in mice fed a high-fat western-style diet. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2018, 1863, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moller, D.E.; Berger, J.P. Role of PPARs in the regulation of obesity-related insulin sensitivity and inflammation. Int. J. Obes. 2003, 27 (Suppl. S3), S17–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurencikiene, J.; Rydén, M. Liver X receptors and fat cell metabolism. Int. J. Obes. 2012, 36, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Easton, R.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Monks, B.R.; Ueki, K.; Kahn, C.R.; Birnbaum, M.J. Loss of Akt1 in mice increases energy expenditure and protects against diet-induced obesity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzi, F.; Xu, L.; Zuellig, R.A.; Boller, S.B.; Spinas, G.A.; Hynx, D.; Chang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Hemmings, B.A.; Tschopp, O.; et al. Differential Effects of Protein Kinase B/Akt Isoforms on Glucose Homeostasis and Islet Mass. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhawans, P.; Behl, T.; Bhardwaj, S. Angiogenesis in obesity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 126, 110103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, D.T.; Farb, M.G.; Kikuchi, R.; Karki, S.; Tiwari, S.; Bigornia, S.J.; Bates, D.O.; LaValley, M.P.; Hamburg, N.M.; Vita, J.A.; et al. Anti-Angiogenic Actions of VEGF-A165b, an Inhibitory Isoform of VEGF-A, in Human Obesity. Circulation 2014, 130, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boothby-Shoemaker, W.; Benham, V.; Paithankar, S.; Shankar, R.; Chen, B.; Bernard, J.J. The Relationship between Leptin, the Leptin Receptor and FGFR1 in Primary Human Breast Tumors. Cells 2020, 9, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Huang, C.; Liu, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, M.; Hou, M.; Liu, Y.; Lin, H. FGF2 disruption enhances thermogenesis in brown and beige fat to protect against obesity and hepatic steatosis. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, A.M.; Simpson, C.L.; Stewart, J.A. The Role of AGE/RAGE Signaling in Diabetes-Mediated Vascular Calcification. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 6809703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellegounder, D.; Zafari, P.; Rajabinejad, M.; Taghadosi, M.; Kapahi, P. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and its receptor, RAGE, modulate age-dependent COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. A review and hypothesis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 98, 107806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandurska-Stankiewicz, E. Thyroid hormones—Obesity and metabolic syndrome. Thyroid Res. 2013, 6, A5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bernard, V.; Young, J.; Binart, N. Prolactin—A pleiotropic factor in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grantham, J.P.; Henneberg, M. The Estrogen Hypothesis of Obesity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.E.; Meoli, C.C.; Mangiafico, S.P.; Fazakerley, D.J.; Cogger, V.C.; Mohamad, M.; Pant, H.; Kang, M.-J.; Powter, E.; Burchfield, J.G.; et al. Systemic VEGF-A Neutralization Ameliorates Diet-Induced Metabolic Dysfunction. Diabetes 2014, 63, 2656–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Molina, A.; Lopez-Guadamillas, E.; De Cabo, R.; Serrano, M. Pharmacological Inhibition of PI3K Reduces Adiposity and Metabolic Syndrome in Obese Mice and Rhesus Monkeys. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Chen, K.; Dong, H.; Yang, J.; Yoshizawa, M.; Kagami, H.; Li, X. Alliin inhibits adipocyte differentiation by downregulating Akt expression: Implications for metabolic disease. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Riopel, M.; Cabrales, P.; Bandyopadhyay, G.K. Hepatocyte-specific HIF-1 ablation improves obesity-induced glucose intolerance by reducing first-pass GLP-1 degradation. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, H.; Deng, R.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L. Berberine Suppresses Adipocyte Differentiation via Decreasing CREB Transcriptional Activity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, K.; Xu, P.; Cordonier, E.L.; Chen, S.S.; Ng, A.; Xu, Y.; Morozov, A.; Fukuda, M. Neuronal Rap1 Regulates Energy Balance, Glucose Homeostasis, and Leptin Actions. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 3003–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.Y.; Seo, S.G.; Yang, H.; Yu, J.G.; Suk, S.J.; Jung, E.S.; Ji, H.; Kwon, J.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, K.W. Anti-adipogenic effect of erucin in early stage of adipogenesis by regulating Ras activity in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.H.; Karadeniz, F.; Lee, J.I.; Seo, Y.; Kong, C.-S. Artemisia princeps Inhibits Adipogenic Differentiation of 3T3-L1 Pre-Adipocytes via Downregulation of PPARγ and MAPK Pathways. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 24, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Jang, H.-Y.; Park, E.H.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, J.-M.; Kim, E.-K.; Yea, K.; Kim, Y.-H.; Lee-Kwon, W.; Ryu, S.H.; et al. Wedelolactone inhibits adipogenesis through the ERK pathway in human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 113, 3436–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, B.; Pawlak, M.; Lefebvre, P.; Staels, B. PPARs in obesity-induced T2DM, dyslipidaemia and NAFLD. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 13, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).