Host-Defense Peptides with Therapeutic Potential from Skin Secretions of Frogs from the Family Pipidae

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Family Pipidae

3. Peptides with Antimicrobial Activity

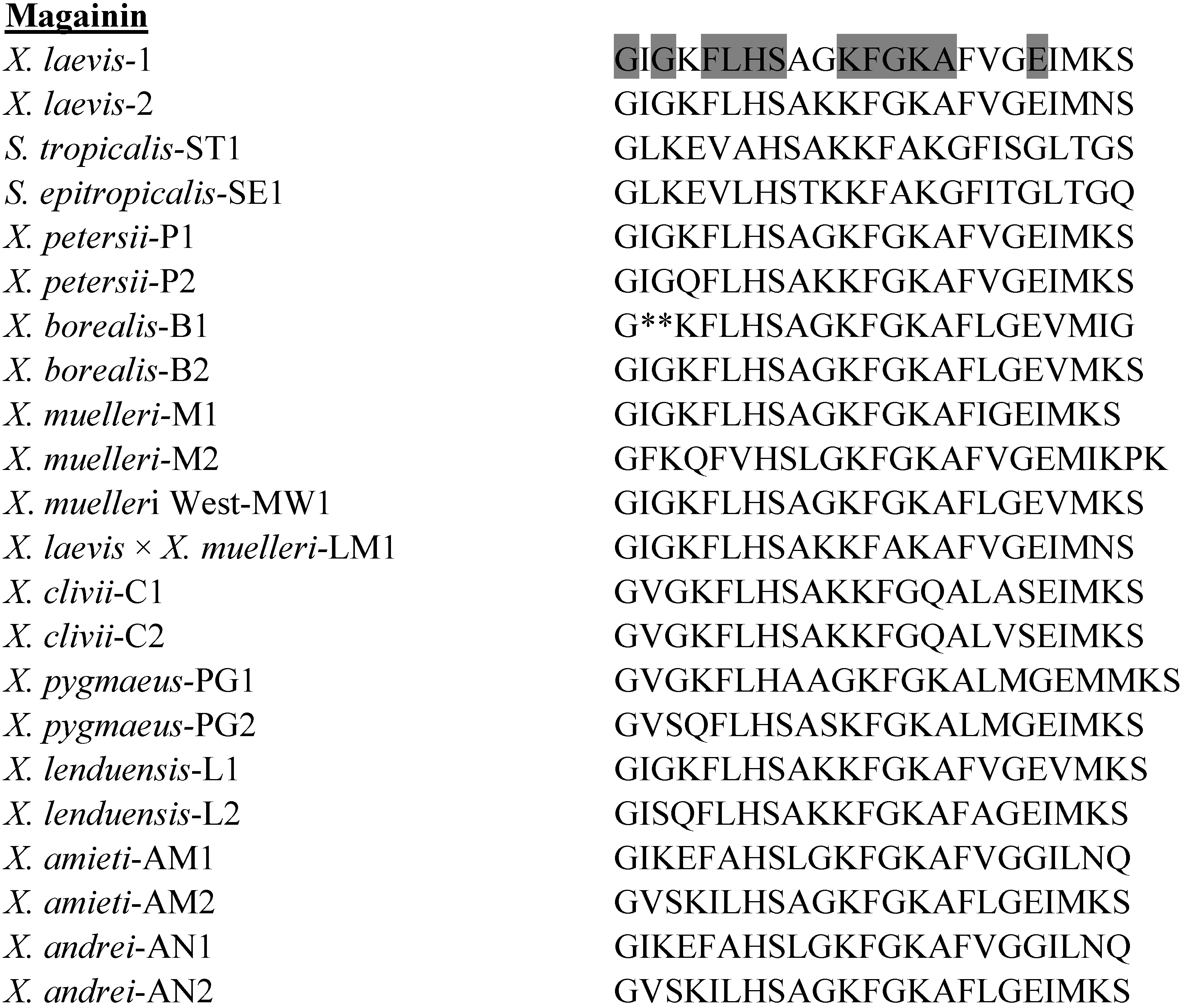

3.1. Magainins

3.2. Peptide Glycine-Leucine-Amide (PGLa) Peptides

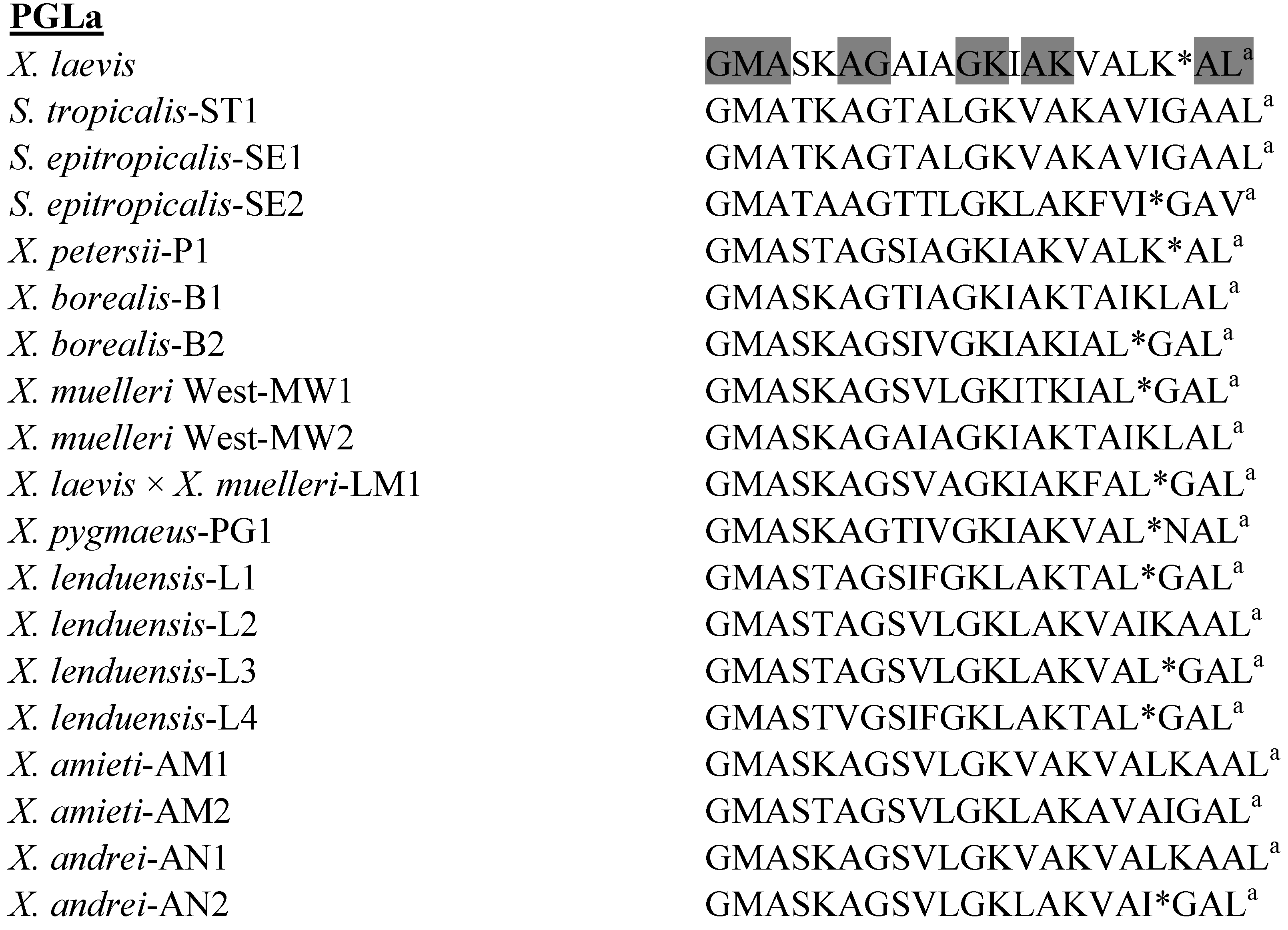

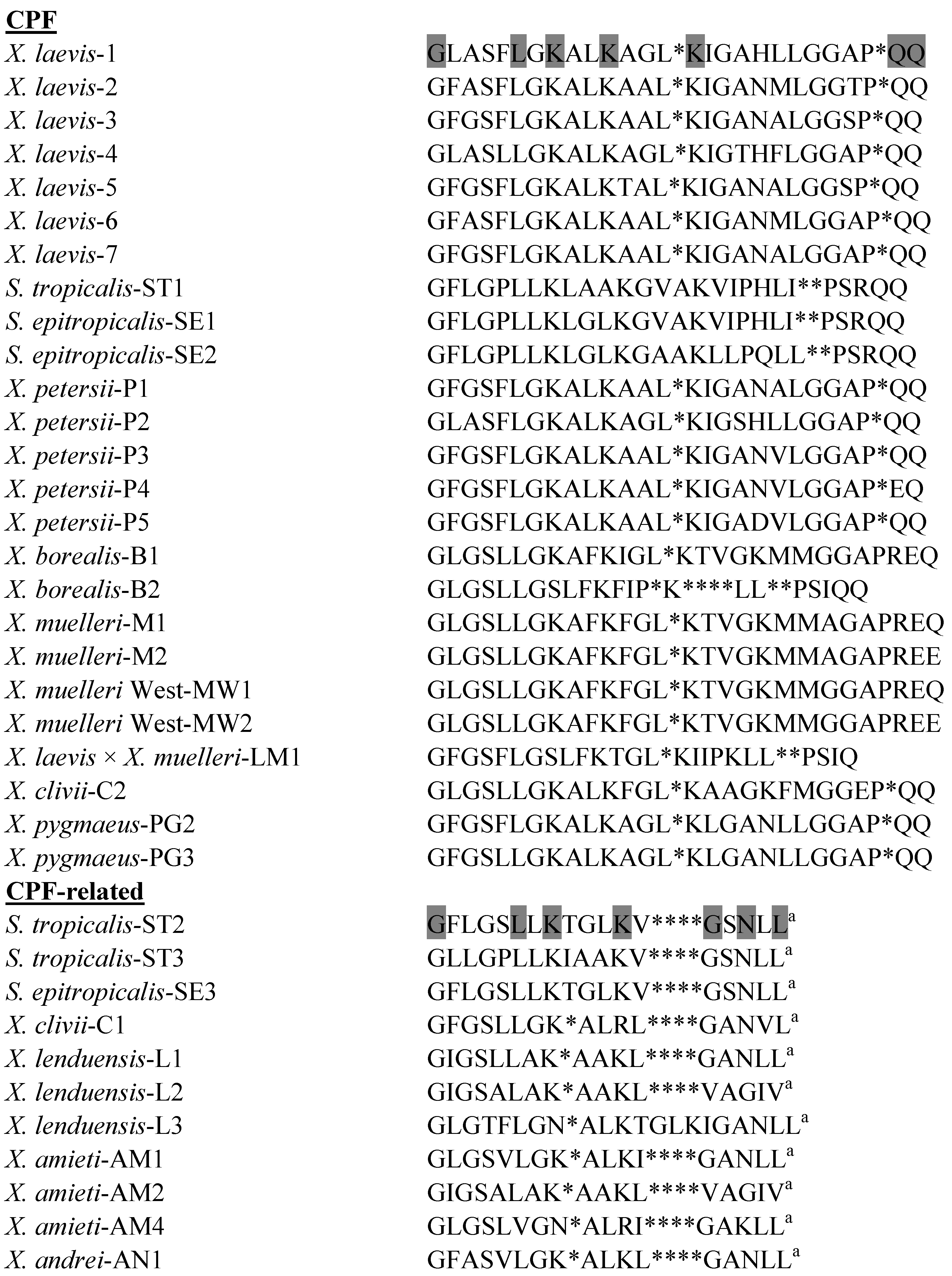

3.3. Caerulein Precursor Fragment (CPF) Peptides

3.4. Xenopsin Precursor Fragment (XPF) Peptides

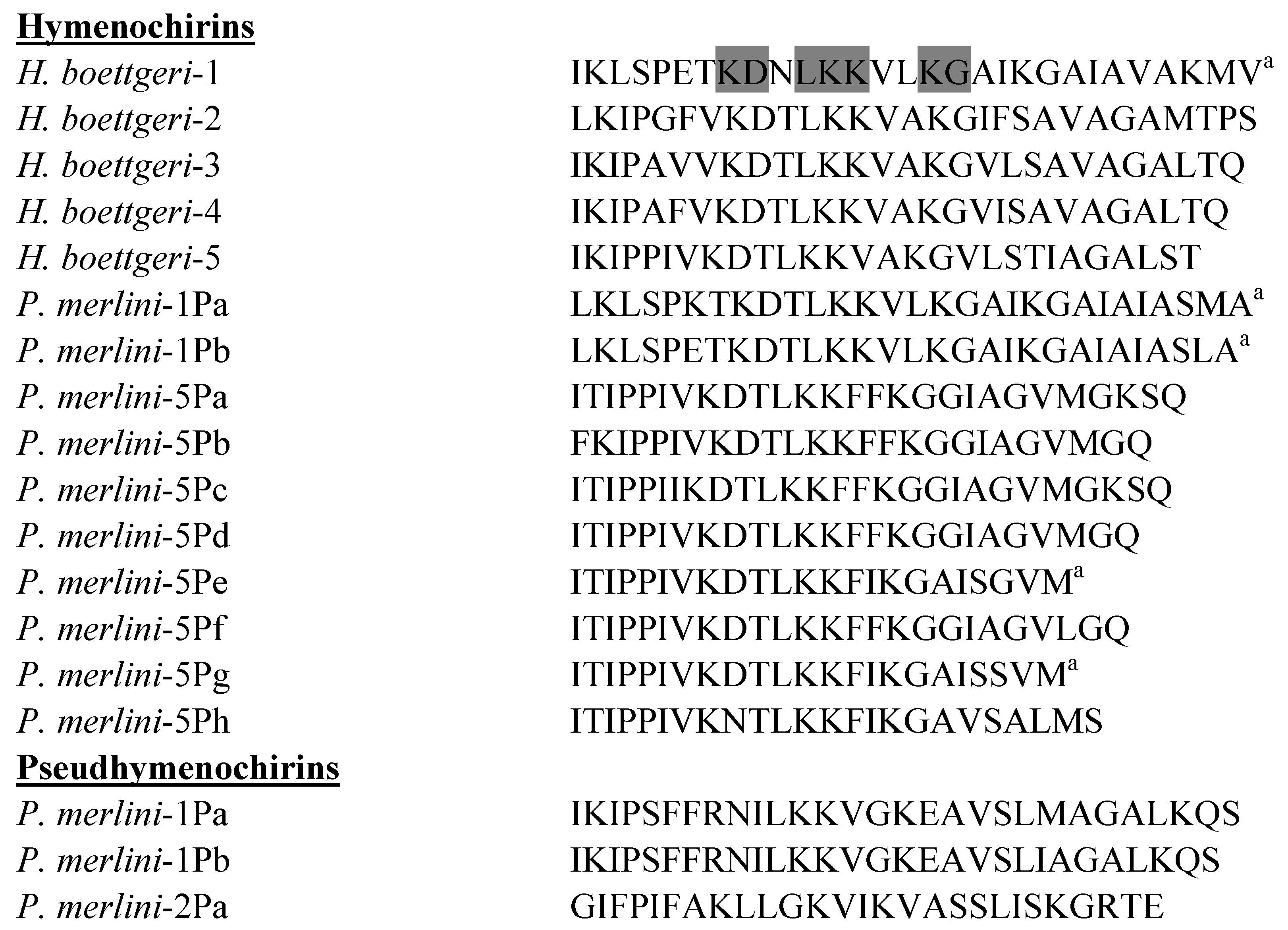

3.5. Hymenochirins

4. Peptides with Anti-Cancer Activity

5. Peptides with Anti-Viral Activity

6. Conclusions

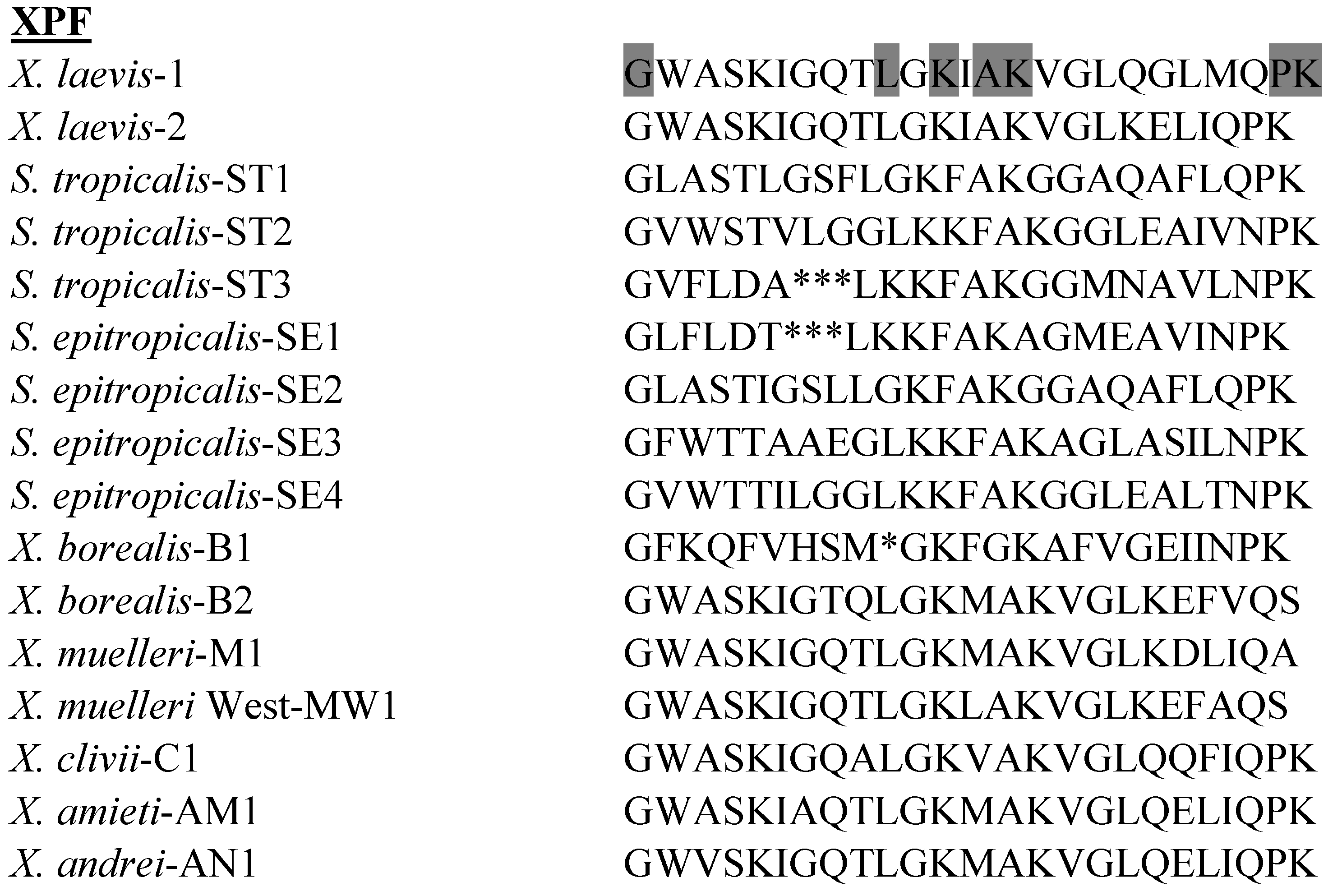

| Peptide | E. coli ATCC 25726 | S. aureus ATCC 25923 | MRSA isolates | A. baumannii isolates | S. maltophilia isolates | K. pneumoniae isolates | LC50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [G4K]CPF-ST3 | 12.5 | 6.25 | ND | 1.6–3.1 | ND | ND | >500 |

| PGLa-AM1 | 12.5 | 25 | ND | 4–32 | 2–16 | ND | >500 |

| CPF-AM1 | 12.5 | 6.25 | ND | 2–8 | 2–8 | 25 | 150 |

| CPF-C1 | 6.25 | 6.25 | ND | 3.1 | ND | 25 | 140 |

| CPF-SE2 | 40 | 2.5 | 2.5 | ND | ND | ND | 50 |

| CPF-SE3 | 40 | 2.5 | 5 | ND | ND | ND | 220 |

| [E6k,D9k] hymenochirin-1B | 3.1 | 1.6 | 3.1–6.25 | 1.6 | 0.8–3.1 | 3.1–6.25 | 300 |

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Savard, P.; Perl, T.M. A call for action: Managing the emergence of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the acute care settings. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 25, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M. The contribution of skin antimicrobial peptides to the system of innate immunity in anurans. Cell Tissue Res. 2011, 343, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M. Structural diversity and species distribution of host-defense peptides in frog skin secretions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011, 68, 2303–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.T.Y.; Gellatly, S.L.; Hancock, R.E. Multifunctional cationic host defence peptides and their clinical applications. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011, 68, 2161–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammill, W.M.; Fites, J.S.; Rollins-Smith, L.A. Norepinephrine depletion of antimicrobial peptides from the skin glands of Xenopus laevis. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2012, 37, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.F.; Pokorny, A. Mechanisms of antimicrobial, cytolytic, and cell-penetrating peptides: From kinetics to thermodynamics. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 8083–8093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, Y. Alpha-helical cationic antimicrobial peptides: Relationships of structure and function. Protein Cell 2010, 1, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennessen, J.A.; Woodhams, D.C.; Chaurand, P.; Reinert, L.K.; Billheimer, D.; Shyr, Y.; Caprioli, R.M.; Blouin, M.S.; Rollins-Smith, L.A. Variations in the expressed antimicrobial peptide repertoire of northern leopard frog (Rana pipiens) populations suggest intraspecies differences in resistance to pathogens. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2009, 33, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Al-Ghaferi, N.; Abraham, B.; Leprince, J. Strategies for transformation of naturally-occurring amphibian antimicrobial peptides into therapeutically valuable anti-infective agents. Methods 2007, 42, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Vasil, A.I.; Hale, J.D.; Hancock, R.E.; Vasil, M.L.; Hodges, R.S. Effects of net charge and the number of positively charged residues on the biological activity of amphipathic alpha-helical cationic antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers 2008, 90, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, K. Control of cell selectivity of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1788, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.R. Amphibian Species of the World: An Online Reference, Version 5.6. 2013, Electronic Database. American Museum of Natural History: New York, USA. Available online: http://research.amnh.org/herpetology/amphibia/index.php (accessed on 13 January 2014).

- Frost, D.R.; Grant, T.; Faivovich, J.; Bain, R.H.; Haas, A.; Haddad, C.F.B.; de Sá, R.O.; Channing, A.; Wilkinson, M.; Donnellan, S.C.; et al. The amphibian tree of life. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2006, 297, 1–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.J.; Kelley, D.B.; Tinsley, R.C.; Melnick, D.J.; Cannatella, D.C. A mitochondrial DNA phylogeny of African clawed frogs: Phylogeography and implications for polyploid evolution. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004, 33, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.J. Genome evolution and speciation genetics of clawed frogs (Xenopus and Silurana). Front. Biosci. 2008, 13, 4687–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irisarri, I.; Vences, M.; San Mauro, D.; Glaw, F.; Zardoya, R. Reversal to air-driven sound production revealed by a molecular phylogeny of tongueless frogs, family Pipidae. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewick, A.J.; Chain, F.J.; Heled, J.; Evans, B.J. The pipid root. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelants, K.; Bossuyt, F. Archaeobatrachian paraphyly and pangaean diversification of crown- group frogs. Syst. Biol. 2005, 54, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelants, K.; Gower, D.J.; Wilkinson, M.; Loader, S.P.; Biju, S.D.; Guillaume, K.; Moriau, L.; Bossuyt, F. Global patterns of diversification in the history of modern amphibians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez, A.M. The Fossil Record of the Pipidae. In The Biology of Xenopus; Tinsley, R.C., Kobel, H.R., Eds.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kobel, H.R.; Loumont, C.; Tinsley, R.C. The Extant Species. In The Biology of Xenopus; Tinsley, R.C., Kobel, H.R., Eds.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, B.J.; Greenbaum, E.; Kusamba, C.; Carter, T.F.; Tobias, M.L.; Mendel, S.A.; Kelley, D.B. Description of a new octoploid frog species (Anura: Pipidae: Xenopus) from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with a discussion of the biogeography of African clawed frogs in the Albertine Rift. J. Zool. 2011, 283, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymowska, J.; Fischberg, M. A comparison of the karyotype, constitutive heterochromatin, and nucleolar organizer regions of the new tetraploid species Xenopus epitropicalis Fischberg and Picard with those of Xenopus tropicalis Gray (Anura, Pipidae). Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1982, 34, 49–157. [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff, M. Magainins, a class of antimicrobial peptides from Xenopus skin: Isolation, characterization of two active forms and partial cDNA sequence of a precursor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 5449–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, B.W.; Poulter, L.; Williams, D.H.; Maggio, J.E. Novel peptide fragments originating from PGLa and the caerulein and xenopsin precursors from Xenopus laevis. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 5341–5349. [Google Scholar]

- Soravia, E.; Martini, G.; Zasloff, M. Antimicrobial properties of peptides from Xenopus granular gland secretions. FEBS Lett. 1988, 228, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, L.T.; Barker, W.C. Relationship of promagainin to three other prohormones from the skin of Xenopus laevis: A different perspective. FEBS Lett. 1988, 233, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Al-Ghaferi, N.; Ahmed, E.; Meetani, M.A.; Leprince, J.; Nielsen, P.F. Orthologs of magainin, PGLa, procaerulein-derived, and proxenopsin-derived peptides from skin secretions of the octoploid frog Xenopus amieti (Pipidae). Peptides 2010, 31, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechkarska, M.; Ahmed, E.; Coquet, L.; Leprince, J.; Jouenne, T.; Vaudry, H.; King, J.D.; Takada, K.; Conlon, J.M. Genome duplications within the Xenopodinae do not increase the multiplicity of antimicrobial peptides in Silurana paratropicalis and Xenopus andrei skin secretions. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D Genomics Proteomics 2011, 6, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechkarska, M.; Ahmed, E.; Coquet, L.; Leprince, J.; Jouenne, T.; Vaudry, H.; King, J.D.; Conlon, J.M. Antimicrobial peptides with therapeutic potential from skin secretions of the Marsabit clawed frog Xenopus borealis (Pipidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 152, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Mechkarska, M.; Ahmed, E.; Leprince, J.; Vaudry, H.; King, J.D.; Takada, K. Purification and properties of antimicrobial peptides from skin secretions of the Eritrea clawed frog Xenopus clivii (Pipidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2011, 153, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.D.; Mechkarska, M.; Coquet, L.; Leprince, J.; Jouenne, T.; Vaudry, H.; Takada, K.; Conlon, J.M. Host-defense peptides from skin secretions of the tetraploid frogs Xenopus petersii and Xenopus pygmaeus, and the octoploid frog Xenopus lenduensis (Pipidae). Peptides 2012, 33, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechkarska, M.; Ahmed, E.; Coquet, L.; Leprince, J.; Jouenne, T.; Vaudry, H.; King, J.D.; Conlon, J.M. Peptidomic analysis of skin secretions demonstrates that the allopatric populations of Xenopus muelleri (Pipidae) are not conspecific. Peptides 2011, 32, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.D.; Mechkarska, M.; Meetani, M.A.; Conlon, J.M. Peptidomic analysis of skin secretions provides insight into the taxonomic status of the African clawed frogs Xenopus victorianus and Xenopus laevis sudanensis (Pipidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D Genomics Proteomics 2013, 8, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechkarska, M.; Meetani, M.; Michalak, P.; Vaksman, Z.; Takada, K.; Conlon, J.M. Hybridization between the tetraploid African clawed frogs Xenopus laevis and Xenopus muelleri (Pipidae) increases the multiplicity of antimicrobial peptides in the skin secretions of female offspring. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D Genomics Proteomics 2012, 7, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechkarska, M.; Prajeep, M.; Leprince, J.; Vaudry, H.; Meetani, M.A.; Evans, B.J.; Conlon, J.M. A comparison of host-defense peptides in skin secretions of female Xenopus laevis × Xenopus borealis and X. borealis × X. laevis F1 hybrids. Peptides 2013, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Soto, A.; Knoop, F.C.; Conlon, J.M. Antimicrobial peptides isolated from skin secretions of the diploid frog, Xenopus tropicalis (Pipidae). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2001, 1550, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Roelants, K.; Fry, B.G.; Ye, L.; Stijlemans, B.; Brys, L.; Kok, P.; Clynen, E.; Schoofs, L.; Cornelis, P.; Bossuyt, F. Origin and functional diversification of an amphibian defense peptide arsenal. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Mechkarska, M.; Prajeep, M.; Sonnevend, A.; Coquet, L.; Leprince, J.; Jouenne, T.; Vaudry, H.; King, J.D. Host-defense peptides in skin secretions of the tetraploid frog Silurana epitropicalis with potent activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Peptides 2012, 37, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechkarska, M.; Prajeep, M.; Coquet, L.; Leprince, J.; Jouenne, T.; Vaudry, H.; King, J.D.; Conlon, J.M. The hymenochirins: A family of antimicrobial peptides from the Congo dwarf clawed frog Hymenochirus boettgeri (Pipidae). Peptides 2012, 35, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Prajeep, M.; Mechkarska, M.; Coquet, L.; Leprince, J.; Jouenne, T.; Vaudry, H.; King, J.D. Characterization of the host-defense peptides from skin secretions of Merlin’s clawed frog Pseudhymenochirus merlini: Insights into phylogenetic relationships among the Pipidae. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D Genomics Proteomics 2013, 8, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmerhorst, E.J.; Reijnders, M.; van’t Hof, W.; Veerman, C.; Nieuw-Amerongen, A.V. A critical comparison of the hemolytic and fungicidal activities of cationic antimicrobial peptides. FEBS Lett. 1999, 449, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imura, Y.; Choda, N.; Matsuzaki, K. Dagainin 2 in action: Distinct modes of membrane permeabilization in living bacterial and mammalian cells. Biophys. J. 2008, 95, 5757–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamba, Y.; Ariyama, H.; Levadny, V.; Yamazaki, M. Kinetic pathway of antimicrobial peptide magainin 2-induced pore formation in lipid membranes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 12018–12026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epand, R.F.; Maloy, W.L.; Ramamoorthy, A.; Epand, R.M. Probing the “charge cluster mechanism” in amphipathic helical cationic antimicrobial peptides. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 4076–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasloff, M.; Martin, B.; Chen, H.C. Antimicrobial activity of synthetic magainin peptides and several analogues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 910–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, J.H.; Rodriguez, B.; Houghten, R.A. The magainins: Sequence factors relevant to increased antimicrobial activity and decreased hemolytic activity. Pept. Res. 1988, 1, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.Y.; Kang, J.H.; Lee, M.K.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, Y.; Hahm, K.S. Cecropin A—Magainin 2 hybrid peptides having potent antimicrobial activity with low hemolytic effect. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 1998, 44, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, P.C.; Barry, A.L.; Brown, S.D. In vitro antimicrobial activity of MSI-78, a magainin analog. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 1213–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; MacDonald, D.L.; Holroyd, K.J.; Thornsberry, C.; Wexler, H.; Zasloff, M. In vitro antibacterial properties of pexiganan, an analog of magainin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 782–788. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; MacDonald, D.; Henry, M.M.; Hait, H.I.; Nelson, K.A.; Lipsky, B.A.; Zasloff, M.A.; Holroyd, K.J. In vitro susceptibility to pexiganan of bacteria isolated from infected diabetic foot ulcers. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1999, 35, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, B.A.; Holroyd, K.J.; Zasloff, M. Topical versus systemic antimicrobial therapy for treating mildly infected diabetic foot ulcers: A randomized, controlled, double-blinded, multicenter trial of pexiganan cream. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwahori, A.; Hirota, Y.; Sampe, R.; Miyano, S.; Takahashi, N.; Sasatsu, M.; Kondo, I.; Numao, N. On the antibacterial activity of normal and reversed magainin 2 analogs against Helicobacter pylori. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1997, 20, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, E.A.; Rana, F.; Blazyk, J.; Modrzakowski, M.C. Bactericidal activity of magainin 2: Use of lipopolysaccharide mutants. Can. J. Microbiol. 1990, 36, 582–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genco, C.A.; Maloy, W.L.; Kari, U.P.; Motley, M. Antimicrobial activity of magainin analogues against anaerobic oral pathogens. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2003, 21, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, F.L.; Jacob, L.S. Effects of magainins on ameba and cyst stages of Acanthamoeba polyphaga. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1992, 36, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmerhorst, E.J.; Reijnders, I.M.; van’t Hof, W.; Simoons-Smit, I.; Veerman, E.C.; Amerongen, A.V. Amphotericin B- and fluconazole-resistant Candida spp., Aspergillus fumigatus, and other newly emerging pathogenic fungi are susceptible to basic antifungal peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 702–704. [Google Scholar]

- Westerhoff, H.V.; Zasloff, M.; Rosner, J.L.; Hendler, R.W.; de Waal, A.; Vaz Gomes, A.; Jongsma, P.M.; Riethorst, A.; Juretić, D. Functional synergism of the magainins PGLa and magainin-2 in Escherichia coli, tumor cells and liposomes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995, 228, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohner, K.; Prossnigg, F. Biological activity and structural aspects of PGLa interaction with membrane mimetic systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1788, 1656–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, E.; Zerweck, J.; Wadhwani, P.; Ulrich, A.S. Synergistic insertion of antimicrobial magainin-family peptides in membranes depends on the lipid spontaneous curvature. Biophys. J. 2013, 104, L9–L11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Sonnevend, A.; Pál, T.; Vila-Farrés, X. Efficacy of six frog skin-derived antimicrobial peptides against colistin-resistant strains of the Acinetobacter baumannii group. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2012, 39, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Galadari, S.; Raza, H.; Condamine, E. Design of potent, non-toxic antimicrobial agents based upon the naturally occurring frog skin peptides, ascaphin-8 and peptide XT-7. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2008, 72, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasinghage, A.P.; Conlon, J.M.; Hewage, C.M. Development of potent anti-infective agents from Silurana tropicalis: Conformational analysis of the amphipathic, alpha-helical antimicrobial peptide XT-7 and its non-haemolytic analogue [G4K]XT-7. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.S.; Bevins, C.L.; Brasseur, M.M.; Tomassini, N.; Turner, K.; Eck, H.; Zasloff, M. Antimicrobial peptides in the stomach of Xenopus laevis. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 19851–19857. [Google Scholar]

- Mechkarska, M.; Prajeep, M.; Radosavljevic, G.D.; Jovanovic, I.P.; Al Baloushi, A.; Sonnevend, A.; Lukic, M.L.; Conlon, J.M. An analog of the host-defense peptide hymenochirin-1B with potent broad-spectrum activity against multidrug-resistant bacteria and immunomodulatory properties. Peptides 2013, 50, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, J.S.; Hoskin, D.W. Cationic antimicrobial peptides as novel cytotoxic agents for cancer treatment. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2006, 15, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsaki, Y.; Gazdar, A.F.; Chen, H.C.; Johnson, B.E. Antitumor activity of magainin analogues against human lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 3534–3538. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, J.; Retz, M.; Sidhu, S.S.; Suttmann, H.; Sell, M.; Paulsen, F.; Harder, J; Unteregger, G.; Stöckle, M. Antitumor activity of the antimicrobial peptide magainin II against bladder cancer cell lines. Eur. Urol. 2006, 50, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruciani, R.A.; Barker, J.L.; Zasloff, M.; Chen, H.C.; Colamonici, O. Antibiotic magainins exert cytolytic activity against transformed cell lines through channel formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 3792–3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszałka, P.; Kamysz, E.; Wejda, M.; Kamysz, W.; Bigda, J. Antitumor activity of antimicrobial peptides against U937 histiocytic cell line. Acta. Biochim. Pol. 2011, 58, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.A.; Maloy, W.L.; Zasloff, M.; Jacob, L.S. Anticancer efficacy of magainin 2 and analogue peptides. Anticancer efficacy of magainin 2 and analogue peptides. Cancer Res. 1993, 53, 3052–3057. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, Y.; Aoki, M.; Yano, Y.; Matsuzaki, K. Interaction of antimicrobial peptide magainin 2 with gangliosides as a target for human cell binding. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 10229–10235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attoub, S.; Arafat, H.; Mechkarska, M.; Conlon, J.M. Anti-tumor activities of the host-defense peptide hymenochirin-1B. Regul. Pept. 2013, 115, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Albiol Matanic, V.C.; Castilla, V. Antiviral activity of antimicrobial cationic peptides against Junin virus and herpes simplex virus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2004, 23, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchar, V.G.; Bryan, L.; Silphadaung, U.; Noga, E.; Wade, D.; Rollins-Smith, L. Inactivation of viruses infecting ectothermic animals by amphibian and piscine antimicrobial peptides. Virology 2004, 323, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.E.; O’Brien, L.M.; Thwaite, J.E.; Fox, M.A.; Atkins, H.; Ulaeto, D.O. A carpet-based mechanism for direct antimicrobial peptide activity against vaccinia virus membranes. Peptides 2010, 31, 1966–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, D.; Mechkarska, M.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.; Flatt, P.R.; Conlon, J.M. Caerulein precursor fragment (CPF) peptides from the skin secretions of Xenopus laevis and Silurana epitropicalis are potent insulin-releasing agents. Biochimie 2013, 95, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, O.O.; Conlon, J.M.; Flatt, P.R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H. Frog skin peptides (tigerinin-1R, magainin-AM1, -AM2, CPF-AM1, and PGla-AM1) stimulate secretion of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) by GLUTag cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 431, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, J.M.; Mechkarska, M.; Lukic, M.L.; Conlon, J.M. Effects of tigerinin peptides on cytokine production by mouse peritoneal macrophages and spleen cells and by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biochimie 2014, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsaki, A.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J. Emerging drugs for the treatment of sepsis. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2012, 17, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Conlon, J.M.; Mechkarska, M. Host-Defense Peptides with Therapeutic Potential from Skin Secretions of Frogs from the Family Pipidae. Pharmaceuticals 2014, 7, 58-77. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph7010058

Conlon JM, Mechkarska M. Host-Defense Peptides with Therapeutic Potential from Skin Secretions of Frogs from the Family Pipidae. Pharmaceuticals. 2014; 7(1):58-77. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph7010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleConlon, J. Michael, and Milena Mechkarska. 2014. "Host-Defense Peptides with Therapeutic Potential from Skin Secretions of Frogs from the Family Pipidae" Pharmaceuticals 7, no. 1: 58-77. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph7010058

APA StyleConlon, J. M., & Mechkarska, M. (2014). Host-Defense Peptides with Therapeutic Potential from Skin Secretions of Frogs from the Family Pipidae. Pharmaceuticals, 7(1), 58-77. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph7010058