Abstract

Nanoemulgels have emerged as a promising hybrid drug delivery system that integrates the advantages of nanoemulsions and gels, offering enhanced drug penetration, prolonged residence time, and improved patient compliance. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the therapeutic applications of nanoemulgels in wound healing, microbial infections, skin cancer, and various dermatological disorders. The article begins with an overview of skin architecture and its implications for cutaneous drug delivery, followed by a clear distinction between transdermal and topical drug delivery systems. The mechanisms of drug transport into and through the skin are discussed in detail, highlighting the role of nano-sized carriers, particularly nanoemulsions, in overcoming the stratum corneum barrier. Mechanistic insights into nanocarrier-mediated cutaneous drug transport and their versatility as dermal delivery platforms are described. The formulation aspects of nanoemulgels, including their components and both high-energy and low-energy methods for nanoemulsion preparation, are critically discussed to elucidate their impact on formulation performance. An overview of in vitro characterization techniques and biological screening methods employed to evaluate nanoemulgel performance is presented, along with a tabulated compilation of relevant patents to highlight translational progress. Finally, current challenges, regulatory considerations, and future perspectives are discussed, underscoring the potential of nanoemulgels as a versatile and effective platform for advanced topical drug delivery.

Keywords:

nanoemulsion; nanoemulgel; topical; preparation; wound healing; skin cancer; evaluation; patents 1. Introduction

The fundamental aim of topical drug delivery is to maximize local therapeutic effects in the skin, such as in the treatment of inflammation, infections, pruritus, psoriasis, and dermatitis. These formulations are designed to deliver the therapeutic actives to act at or near the site of application rather than entering the general circulation, thereby resulting in lower overall exposure and a reduced risk of adverse effects [1]. Both topical and transdermal drug delivery systems face notable challenges, including a slow onset of action and the risk of skin irritation, which may vary depending on skin condition. A major limitation of cutaneous drug delivery is the skin’s intrinsic barrier function, which restricts penetration to protect the body from external insults, such as particulate matter, microorganisms, and drugs [2]. A major challenge in skin drug delivery is achieving adequate drug absorption, as only a limited proportion of the administered dose successfully penetrates the stratum corneum (SC) [3]. The effectiveness of skin drug delivery depends mainly on the nature of the drug molecule as well as on advanced design and formulation strategies that enhance permeation across the skin [4]. Since skin properties vary among individuals and across different body sites, and can be further altered by environmental exposure, and skin disorders, site-specific considerations are essential during formulation design to ensure effective drug delivery performance. For instance, age-related changes in skin, including reduced water content and lower enzymatic activity, significantly affect drug transport, leading to decreased permeation of hydrophilic molecules, altered prodrug activation, and increased deposition of nanoparticles [5]. Therefore, the successful design of skin-based delivery systems requires careful consideration of these variables to ensure optimal drug penetration and therapeutic effectiveness.

2. Skin Structure and Barriers

2.1. Skin Architecture and Its Implications for Cutaneous Drug Delivery

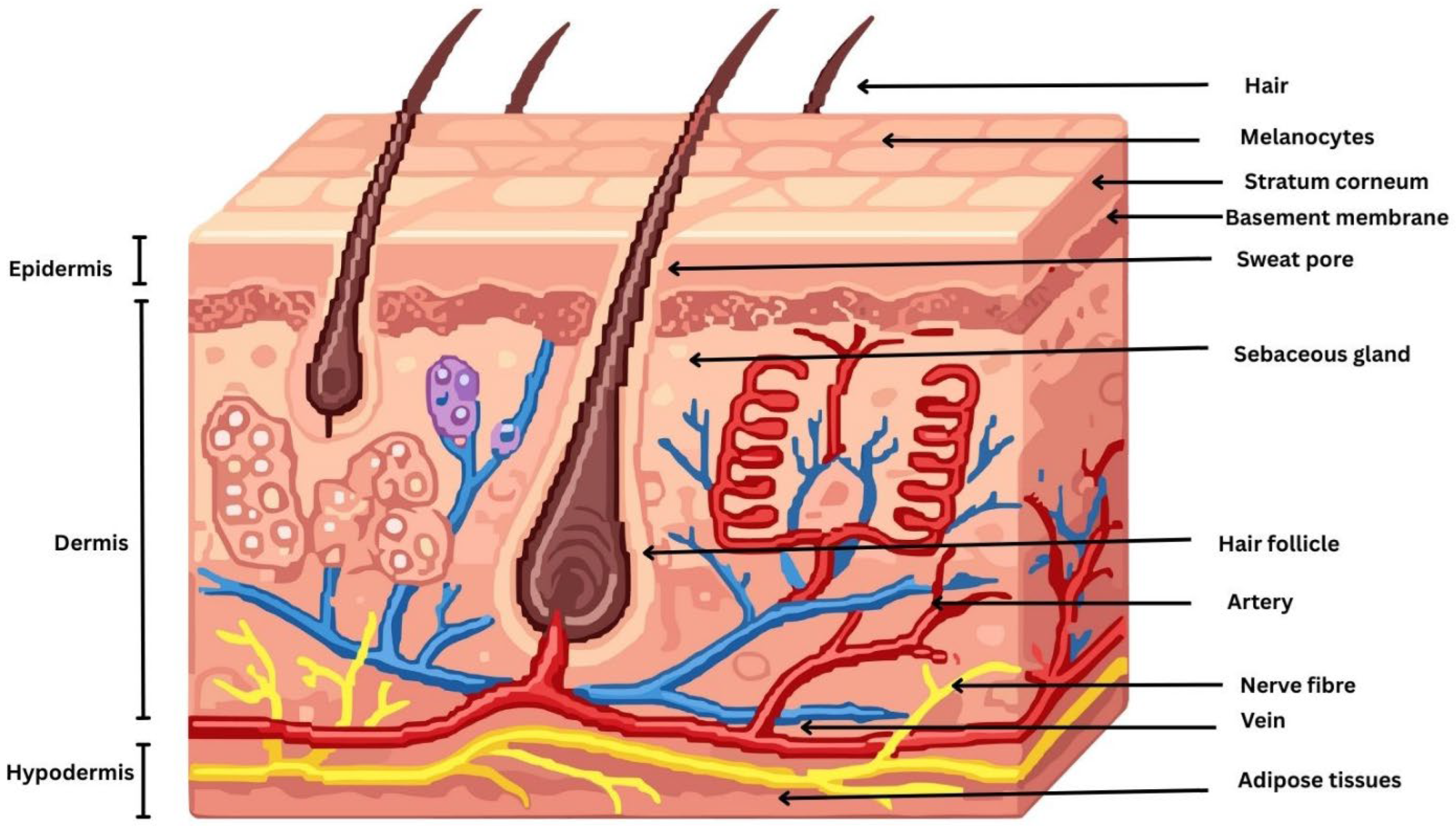

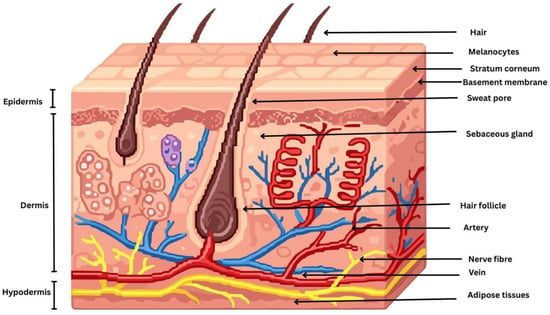

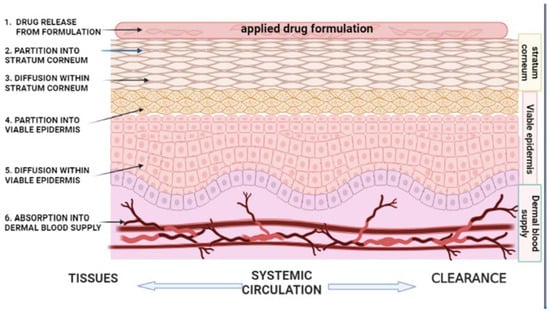

The skin is a complex, multifunctional organ composed of three principal anatomical layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the hypodermis. These layers are structurally and functionally distinct, working synergistically to provide a protective barrier, regulate thermoregulation, facilitate sensory perception, and support immunological and metabolic functions of the body [6]. Topical drug delivery primarily targets the epidermis and superficial dermis, where most localized skin disorders originate. The epidermis consists of the stratum basale, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and SC, with drugs intended to act mainly within the viable epidermal layers. The stratum basale contains keratinocytes, melanocytes, and merkel cells, while the stratum spinosum and stratum granulosum are rich in differentiating keratinocytes and langerhans cells involved in immune regulation. The SC is a highly keratinized outer skin layer, approximately 10–20 µm thick and composed of 15–30 corneocyte layers organized in a characteristic brick-and-mortar architecture, which constitutes the primary barrier to topical drug delivery [7]. The epidermal basement membrane is a specialized interface that anchors the epidermis to the underlying dermis and plays a critical role in maintaining skin structural integrity and stability [8]. Disruption of this membrane can impair skin architecture, cellular metabolism, and regenerative capacity, leading to a range of skin disorders and, in severe cases, contributing to the development of serious dermatological diseases. Beneath the epidermis lies the dermis, a thicker and structurally complex layer composed predominantly of connective tissue rich in collagen and elastic fibers synthesized by sparsely distributed fibroblasts, which together provide mechanical strength and elasticity to the skin [9]. The dermis contains blood vessels, nerves, skin appendages, and specialized sensory cells that support skin function and sensory perception. Blood vessels are predominantly located in the dermis; however, under pathological conditions such as warts, nevi, and skin cancers, vascular proliferation and extension toward the epidermis may occur [10]. Below the dermis lies the hypodermis, or subcutaneous tissue, the deepest layer of the skin. Skin properties are influenced by environmental factors (e.g., UV radiation, pollutants, and toxins), lifestyle factors (e.g., diet and smoking), and physiological factors (e.g., aging, hormonal changes, and stress), which may disrupt skin homeostasis and contribute to dermatological disorders, including acne, skin melanoma, dermatitis, eczema, and psoriasis [11,12]. Understanding the structural and cellular composition of these layers is essential for designing effective topical drug delivery systems that achieve localized therapeutic action [13]. A schematic diagram illustrating the morphology of the skin is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the morphology of the skin.

2.2. Drug Transport Pathways Across the Skin

The SC forms a strong hydrophobic barrier that restricts the penetration of exogenous substances, including drugs and toxins [14]. This barrier function arises from flattened, keratin-rich corneocytes embedded in intercellular ceramide-based lipid bilayers that restrict molecular penetration. Modifying key stages of percutaneous absorption, particularly partitioning and diffusion, can enhance drug delivery to the skin [15]. Drug diffusion across this barrier occurs through a combination of lateral movement within lipid domains and trans-bilayer transport [16]. Computational modeling studies have demonstrated that diffusion within the SC lipid bilayers is predominantly lateral and occurs at rates significantly higher than perpendicular diffusion, thereby facilitating the transport of highly lipophilic molecules [17]. Effective percutaneous delivery requires that a drug reaches the skin surface in adequate amounts and at an appropriate rate. Permeation across the SC requires drugs to possess balanced solubility in both lipid and aqueous phases, a low molecular weight (typically <500 Da), and moderate lipophilicity (log P) ranging between 1 and 3 [18]. Among these factors, lipophilicity and molecular weight are the most influential determinants of skin permeability, as quantitatively described by the Potts and Guy equation, log P = −6.3 + 0.71 log Ko/w − 0.061 MW [19]. The dissolution and diffusion of drug molecules through the skin are significantly influenced by physicochemical properties such as melting point, pKa (dissociation constant), and overall charge [20].

Skin penetration in cutaneous drug delivery occurs primarily through three pathways: transcellular, paracellular (intercellular), and appendageal routes, with the extent of penetration governed by the physicochemical properties of both the drug and nanocarrier [21]. In the transcellular route, molecules pass directly through corneocytes, alternating between hydrophilic intracellular domains and lipophilic membrane regions. Because this pathway favors small, lipophilic, and uncharged molecules, permeation is strongly influenced by a drug’s partition coefficient, molecular weight, and solubility within SC lipids [22]. Although this pathway is the most direct, repeated transitions between aqueous and lipid phases limit its contribution to overall absorption, making it a minor route unless nanocarriers enhance membrane fluidity or improve drug solubility [23]. In the paracellular route, drug molecules diffuse through the tortuous lipid channels between densely packed keratinocytes, a process that avoids cellular damage and favors lipophilic compounds. However, the hydrophilic molecules face significant resistance due to the highly ordered lamellar lipid structure of the SC [24]. The transappendageal or follicular pathway contributes only ~0.1% of the total surface area, which involves drug penetration through hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and sweat ducts. It facilitates the entry of macromolecules, peptides, proteins, vaccines, and ionic compounds that poorly permeate the lipid-rich SC, with hair follicles acting as reservoirs for sustained delivery and sweat ducts providing hydrophilic pathways for charged molecules [25]. Nonetheless, its relevance is growing for nanoparticle-based delivery, vaccines, and targeted follicular therapy, where particle size, charge, and flexibility influence follicular uptake and retention. Although the appendageal route represents a small percentage of the skin surface, hair follicles and sebaceous glands serve as efficient low-resistance pathways, acting as reservoirs that retain nanoparticles and support sustained or targeted delivery, particularly for lipophilic drugs used in topical conditions [26].

Although the penetration of highly hydrophilic actives into the SC remains debated, evidence suggests the existence of an alternative corneocytary diffusion pathway involving corneocyte remnants and corneodesmosomes [27,28]. Small hydrophilic molecules (e.g., short peptides) can diffuse into the SC and corneocyte-associated regions, and their transport may be enhanced by hydrophilic diffusion enhancers such as N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, 2-pyrrolidone, and Transcutol®. This pathway also offers potential for nano-based topical delivery systems, as appropriately engineered nanocarriers may modify local microenvironments to improve hydration and facilitate the delivery of larger hydrophilic biomolecules into the skin. Together, these mechanisms determine drug localization within the skin and are critical considerations in the design of effective topical formulations aimed at achieving localized therapeutic action.

3. Strategies of Skin-Based Drug Delivery

3.1. Transdermal and Topical Approaches

Transdermal and topical drug delivery systems both utilize the skin as a route of administration but differ in their therapeutic objectives and formulation design [29]. Transdermal drug delivery is intended to transport active pharmaceutical ingredients across the skin and into the systemic circulation to produce systemic effects and is commonly employed for drugs requiring sustained release, such as hormones (e.g., estradiol, testosterone), analgesics (e.g., fentanyl, buprenorphine), nicotine, antianginal agents (e.g., nitroglycerin), antihypertensives (e.g., clonidine), antiemetics (e.g., scopolamine), and antiparkinsonian agents such as rotigotine [30]. In contrast, topical drug delivery is primarily designed to exert localized therapeutic effects at or near the site of application, with minimal systemic absorption. This route is widely used for the treatment of dermatological conditions, including infections, inflammation, wound healing and skin disorders, and is optimized to enhance local drug retention rather than systemic pharmacokinetic control [31]. Topical drug delivery for skin diseases has traditionally relied on conventional formulations such as creams, ointments, lotions, gels, and pastes, which are effective for delivering drugs to superficial skin layers but often suffer from limitations including poor skin penetration, low drug stability, and variable therapeutic efficacy [32]. In recent years, nanotechnology-based delivery systems such as liposomes, niosomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, nanostructured lipid carriers, polymeric nanoparticles, and nanoemulsions have gained significant attention due to their ability to enhance skin penetration, improve drug solubility and stability, provide controlled drug release, and reduce local and systemic adverse effects [33,34,35].

3.2. Physiological and Physicochemical Determinants of Percutaneous Drug Absorption

Skin physiology plays a crucial role in percutaneous drug absorption, with variations in the thickness and lipid composition of the SC across different anatomical sites significantly influencing drug permeation [36]. Studies evaluating various chemically formulated gels and solutions demonstrated that percutaneous absorption varies by body region and is influenced by both the physicochemical properties of the formulation and the site of application [37]. Higher absorption was observed from the head, neck, and genital areas, while the trunk, back, and thighs showed comparatively lower uptake. Percutaneous absorption is enhanced in preterm neonates, infants, and young children due to better epidermal hydration, a thinner and more highly perfused SC, and a larger body surface area to body mass ratio, necessitating cautious use to avoid overdosage [38]. Ceramides are essential components of the SC lipid matrix and play a critical role in maintaining skin barrier integrity by limiting transepidermal water loss and restricting the penetration of external substances [39]. Different ceramide subclasses influence the skin barrier to varying extents; for example, ceramide NS is associated with barrier impairment, whereas ceramide NP is linked to intact and healthy skin. Molecular dynamics simulations show that NP-containing membranes have much lower water permeability than NS-containing membranes due to structural differences, confirming their role in skin permeability control. The density of dermal capillary blood vessels influences systemic drug uptake by maintaining a favorable concentration gradient, while hair follicles and sweat ducts provide alternative pathways that enhance drug penetration via the transfollicular route [40]. In addition, increased body temperature promotes vasodilation and elevated skin blood flow, resulting in higher absorption rates. A computational heat–mass transfer model showed that increasing skin temperature enhances transdermal drug absorption, with a 10 °C rise causing about a two-fold increase in nicotine uptake due to diffusion through the SC [41]. The model also demonstrated effective dermal clearance via capillaries and accurately predicted human pharmacokinetic data under normal and elevated temperatures. The use of occlusive systems enhances SC hydration, leading to increased dermal and transdermal drug absorption by swelling corneocytes, altering lipid organization, raising skin temperature, and increasing blood flow, making occlusive systems highly relevant in drug delivery [42].

A general classification system was developed to relate drug skin permeation and retention to key physicochemical properties and drug–lipid interactions, providing a theoretical basis for the rational design and evaluation of topical and transdermal drug delivery systems [43]. Topical formulations aim for high skin retention with minimal systemic absorption to reduce side effects, whereas transdermal systems and some topical products are designed to deliver drugs into the systemic circulation or subcutaneous tissues with lower skin retention to avoid local irritation [43]. However, drug permeation and skin retention occur simultaneously, and even locally applied drugs may enter systemic circulation [44]. Conventional topical formulations rely on passive diffusion and are suitable only for low molecular weight, moderately lipophilic, and highly potent drugs administered at low doses. Drug–vehicle interaction techniques such as prodrug selection, ion pairing, eutectic system formation, and thermodynamic enhancement represent second-generation transdermal strategies designed to enhance skin absorption without damaging deeper skin tissues [45]. The prodrug approach enhances skin absorption by increasing drug hydrophobicity through covalent modification, allowing better penetration of the SC and subsequent conversion to the active drug after absorption [46]. Ion pairing improves transdermal delivery of ionized drugs by forming neutral complexes that enhance SC permeation and dissociate after skin penetration to release the active drug [47]. Despite their advantages, drug–vehicle interaction methods have limitations, including potential toxicity from unpredictable prodrug metabolism, possible toxicity of linking agents or byproducts, complex and limited synthesis processes, and continued reliance on passive diffusion, with the SC remaining a major barrier to transdermal drug delivery [48].

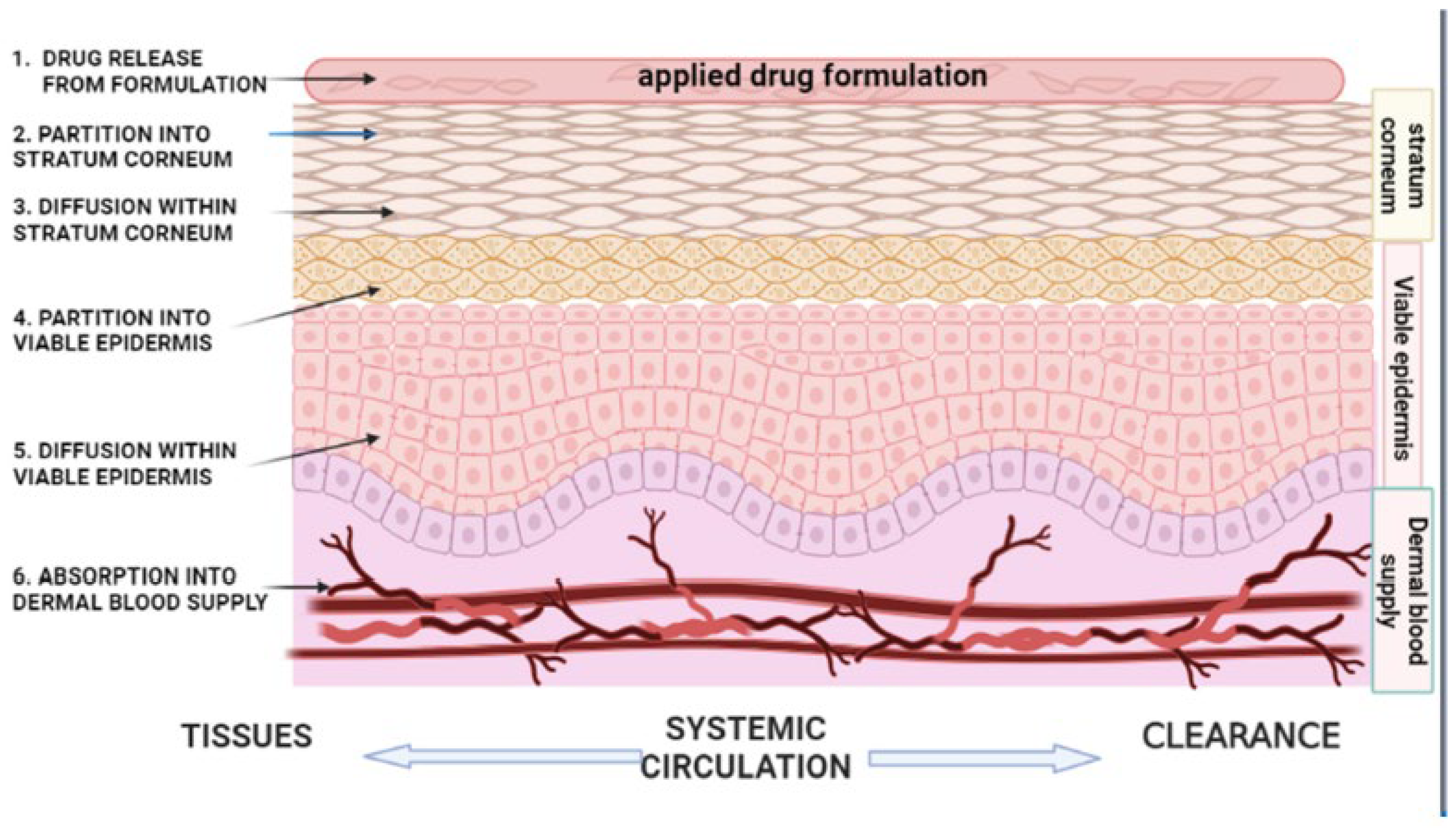

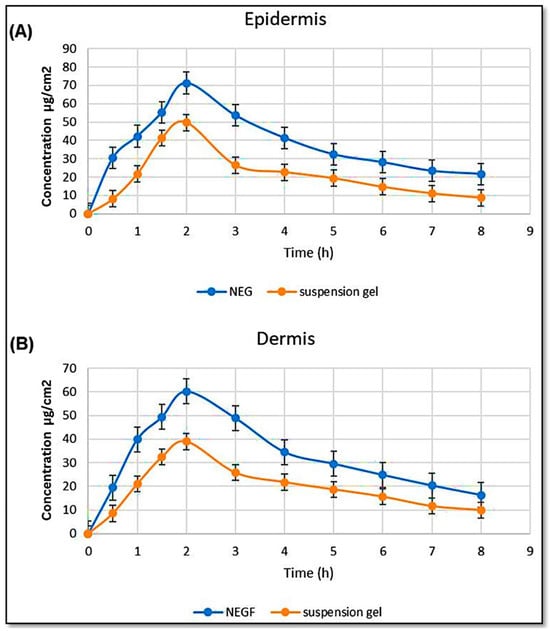

Mathematical models based on Fick’s law of diffusion are commonly applied to quantify drug transport across the skin under steady-state conditions. The steady-state flux (J) of a drug is described by: J = dq/dt = DPCv/h where q is the cumulative amount of drug permeated per unit area over time (t); D denotes the diffusion coefficient within the skin; P is the partition coefficient between the drug, vehicle, and skin; C is the drug concentration in the vehicle; and h corresponds to the thickness of the skin barrier. This relationship highlights the critical influence of both physicochemical drug properties and skin barrier characteristics on topical and transdermal drug delivery performance [49]. The diffusion coefficient and effective skin thickness are physiologically determined parameters that critically affect the physicochemical processes underlying transdermal molecular transport [50]. Percutaneous absorption begins with the release of the drug from the formulation into the SC, a process largely governed by the drug’s thermodynamic activity, with higher activity levels leading to enhanced dermal penetration [51]. The efficacy of topical drug delivery is governed by the drug’s solubility in both the formulation vehicle and the lipid matrix of the SC, which controls its ability to overcome the SC barrier [52]. As the SC constitutes the primary rate-limiting barrier to skin permeation, drugs released from the vehicle must first partition into SC lipids and proteins before diffusing into the viable epidermis and dermis. This partitioning behavior is quantitatively described by the partition coefficient, defined as the ratio of drug concentration in the SC to that in the vehicle [53]. Drug–vehicle and skin–vehicle interactions critically influence drug release and skin permeation by affecting solute availability, release rate, partitioning behavior, and the diffusional resistance and hydration of the SC, thereby modulating overall transdermal flux [54]. An illustration explaining the sequential steps involved in percutaneous drug absorption is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the kinetics of percutaneous drug absorption. The process involves: (1) release and partitioning of the drug from the applied topical formulation vehicle; (2,3) partitioning into and diffusion of the drug across the stratum corneum, which represents the rate-limiting step for most drugs; (4,5) partitioning into and diffusion through the viable epidermis, constituting the rate-limiting step for highly lipophilic drugs; and (6) uptake of the drug into the dermal microcirculation, followed by entry into the systemic circulation for distribution and clearance. This figure is adapted from [45], used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

4. Nanocarrier-Based Systems for Cutaneous Drug Delivery

4.1. Nanocarriers in Skin Delivery

Nanovesicles are nanosized lipid or surfactant-based bilayer vesicles, such as liposomes, ethosomes, transfersomes, transethosomes, niosomes, cubosomes, invasomes, and phytosomes, that enhance drug penetration through the skin by improving drug solubilization, modulating and fluidizing SC lipids, providing protection against drug degradation, and enabling controlled and targeted transdermal drug delivery. Nanovesicular systems enhance dermal and transdermal drug delivery through distinct yet complementary mechanisms [55]. Polymeric micelles, formed by the self-assembly of amphiphilic block copolymers, enhance dermal and transdermal drug delivery by solubilizing poorly water-soluble drugs within their hydrophobic core, improving formulation stability, and enabling controlled release, although their skin penetration is generally limited without the use of penetration-enhancement strategies [56]. Lipid–polymer hybrid nanoparticles combine the stability and controlled release of polymeric cores with the skin affinity of lipid shells, resulting in enhanced penetration and prolonged drug action [57,58]. Nanoemulsions enhance percutaneous drug delivery by improving drug solubility, increasing skin permeation, and facilitating controlled transport across the SC while maintaining skin barrier integrity [59,60]. A comparative evaluation of nanoemulsions and other nanocarrier systems used for cutaneous drug delivery is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative assessment of nanoemulsions and alternative nanocarriers in cutaneous drug delivery.

4.2. Mechanistic Insights into Nanocarrier-Mediated Cutaneous Drug Delivery

Nanocarrier-based cutaneous delivery systems enhance drug permeation by leveraging multiple physicochemical and biological mechanisms that help to overcome the formidable barrier of the SC. Their nanoscale particle size allows intimate contact with the skin surface, thereby improving adhesion and occlusion and facilitating passage through narrow intercellular channels. A recent study demonstrated that cell-penetrating peptide-decorated curcumin-loaded nanoemulsions with nanoscale droplet sizes (<100 nm) significantly enhanced skin penetration by facilitating transport through intercellular lipid pathways of the SC, while confocal laser scanning microscopy confirmed predominant drug retention within the epidermal layers and hair follicles in psoriatic skin, highlighting the superiority of optimized nanoemulsion systems over conventional formulations for cutaneous drug delivery [61]. Understanding how nanaocarrier properties influence skin penetration is crucial for improving dermal drug delivery, yet the role of particle size remains debated because it differs across nanoparticle types [62]. Reported optimal sizes for follicular penetration vary widely, for example, about 640 nm for PLGA particles [63], 80 nm for nanoemulsions [64], and 40–250 nm for polystyrene nanoparticles [65], showing that size effects are highly material-dependent. Mechanistic studies showed that particle size ~100 nm and the viscosity of the aqueous phase in oil-in-water emulsions strongly affect the penetration of poorly soluble, low-permeability ceramides into the epidermis and dermis [66].

Although surface charge is known to influence nanocarrier skin penetration, there is no clear agreement on which charge is most effective. The skin is generally considered negatively charged due to the abundance of anionic lipids in the SC [67]. Some studies report that neutral nanocarriers penetrate more efficiently, suggesting that positively charged particles may be trapped in superficial layers and negatively charged ones may be repelled by the skin barrier [68]. Other findings show that cationic nanomedicines exhibit strong electrostatic attraction to the negatively charged skin surface, enhancing retention and potentially improving treatment outcomes for dermatological disorders. A study investigating luteolin-loaded cationic nanoemulsions (CNEs) demonstrated that electrostatically charged nanocarriers significantly enhance transdermal delivery and skin retention [69]. The optimized formulation (CNE4), with a nanoscale droplet size (~112 nm) and positive zeta potential (+26 mV), showed superior stability, drug release, and ex vivo skin permeation compared with anionic nanoemulsions and drug suspension. Notably, cationic nanoemulsions achieved markedly higher permeation flux and drug deposition within skin layers, attributed to nanosization, surfactant-induced modulation of the SC lipid matrix, and electrostatic interactions with negatively charged skin components, highlighting their potential for improved cutaneous drug retention and transdermal therapy. Another study demonstrated that miconazole nitrate-loaded cationic nanoemulsion gels provided significantly higher skin permeation and dermal drug retention than anionic systems across artificial membranes, EpiDerm, and rat skin [70]. The enhanced performance of cationic formulations was attributed to electrostatic interactions with skin components, optimized formulation composition, and increased skin hydration, with imaging studies confirming deeper penetration, supporting their potential for treating deep-seated fungal infections. Conversely, negatively charged clove oil nanoemulsions demonstrated prolonged antibacterial activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus [71]. Despite the absence of electrostatic attraction, the anionic droplets appeared to self-assemble with bacterial membranes and interact with intracellular components, contributing to their sustained antimicrobial effect.

Deformability of nanoparticles can be enhanced by incorporating membrane-softening agents like deoxycholic acid, allowing carriers to better navigate complex biological environments and improve drug delivery efficiency. Increased deformability is particularly valuable for enhancing skin penetration without disrupting the SC barrier [72]. System deformability, particularly in ultraflexible vesicles such as transfersomes and ethosomes, enables particles to squeeze through constricted intercellular spaces under hydration gradients or osmotic forces, significantly enhancing penetration. Ionic liquids enhance deeper skin penetration by fluidizing SC lipids, improving drug solubility and partitioning into skin layers, increasing nanoemulsion droplet flexibility, and boosting skin hydration. These combined effects open intercellular pathways and facilitate more efficient transport of drugs into deeper epidermal regions. A potent dacarbazine derivative, HIT-1, showed strong anti-melanoma activity, and an oil-in-oil ionic liquid nanoemulsion was developed using the highly permeable, biocompatible L-pyrrolidone carboxylic acid-matrine ionic liquid (P-M IL) to enhance delivery [73]. Among the formulations, HIT-1/PM-ME-1-1 achieved the best skin penetration and antitumor effects, effectively activating apoptosis pathways and stimulating immune responses. Nanoemulsions have been shown to interact with the SC lipid matrix, effectively fluidizing intercellular lipids and reducing barrier resistance, which helps to create alternative permeation pathways and facilitates deeper drug penetration into the skin layer [74].

Due to their small particle size, nanocarriers adhere strongly to the SC, forming an occlusive layer that enhances skin hydration, loosens corneocyte packing, widens intercellular spaces, and consequently improves permeant penetration across the skin barrier [75]. Additionally, studies reported that nanoemulsions create an occlusive effect due to the fluid lipids in their matrix [76].

Many nanocarriers, such as microemulsion and nanoemulsion, incorporate surfactants or lipid components that transiently disrupt or fluidize the SC lipid matrix, reducing its packing density and thereby lowering the diffusional resistance [77]. Furthermore, many nanocarriers enhance drug solubility and thermodynamic activity, creating a strong concentration gradient that drives transdermal flux. In some systems, such as flexible vesicles, nanoparticles, and lipid nanosystems such as nanoemulsion, they have the ability to localize within hair follicles which provides an additional reservoir for sustained release and deeper follicular delivery. It was reported that clove oil-based minoxidil nanoemulsions enhanced follicular drug penetration by more than 26-fold compared with control formulations, highlighting their strong potential for targeted topical treatment of alopecia [78]. Collectively, these mechanisms including size-dependent permeation, SC disruption, hydration enhancement, charge-mediated interactions, and structural deformability enable nanocarrier systems to markedly improve dermal penetration and systemic absorption compared with conventional topical formulations.

4.3. Nanoemulsions as Versatile Platforms for Dermal Drug Delivery

Nanoemulsions are increasingly recognized as superior carriers for dermal and transdermal drug delivery due to their nanosized droplet structure, which provides a large surface area, improved solubilization of poorly water-soluble drugs, and enhanced dispersion within the skin [79]. The dermal and transdermal efficacy of nanoemulsion-based systems has also been demonstrated for water-soluble drugs, such as levamisole [80]. Their small droplet size and surfactant components facilitate greater drug partitioning into and permeation across the SC, overcoming its barrier limitations more effectively than many other nanocarriers [81]. In addition, nanoemulsions can be formulated with stable kinetic properties and flexible composition, allowing both localized dermal retention and systemic transdermal uptake depending on the therapeutic goal [81,82]. Compared with rigid nanoparticles or vesicular systems, their formulation simplicity, physical stability, and ability to incorporate a wide range of hydrophilic as well as hydrophobic actives make them particularly advantageous for both research and clinical translation in skin delivery applications. Nanoemulsions are well recognized in topical drug delivery due to their ability to form uniform films on the skin and effectively overcome the SC barrier, thereby enhancing dermal penetration and drug retention [83]. Numerous in vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated the feasibility and effectiveness of micro and nanoemulsions for skin drug delivery, supporting their application as lipid-based topical formulations [84,85,86]. In addition, nanoemulsions may be integrated into other nanoscale delivery platforms, such as vesicular systems or lipid carriers, where they can function as internal or external phases to enhance drug loading, stability, and skin permeation. Phonophoresis uses ultrasound to enhance transdermal drug absorption by disrupting the SC, and a 2020 clinical study demonstrated that phonophoresis-assisted nanoemulsion delivery significantly improved drug permeation, safety, and therapeutic outcomes in knee chondropathies [87]. Microneedling is a minimally invasive technique that enhances cutaneous delivery by creating microscopic channels in the SC using fine needle arrays or rollers, typically without significant pain or bleeding. Studies have demonstrated that pretreatment of the skin with microneedles significantly improves the transdermal delivery of nanoemulsion-based systems, such as MF59-adjuvanted influenza formulations, by increasing antigen penetration into deeper skin layers [88].

4.4. Nanoemulgels for Topical Drug Delivery

Despite offering several advantages, including favourable physicochemical properties and improved drug thermodynamic stability, nanoemulsions suffer from inherently low viscosity, which limits their spreadability, bioadhesion, and residence time on the skin surface [89]. This fluid nature often results in rapid runoff, nonuniform film formation, and insufficient contact with the SC, thereby reducing drug absorption efficiency and contributing to dose variability, which collectively hinder their clinical translation for topical and transdermal applications. To overcome these limitations, nanoemulsions are incorporated into three-dimensional hydrogel networks to form nanoemulgels, thereby improving viscosity, spreadability, adhesiveness, residence time on the skin, and patient acceptability while retaining the penetration-enhancing properties. As topical or transdermal administration systems, they function as drug reservoirs, facilitating the controlled release of the drug from the dispersed phase to the external or continuous phase, and subsequently onto the skin [90]. Typically formulated using aqueous or hydroalcoholic bases and polymeric gelling agents such as carbomers, cellulose derivatives, or poloxamers, nanoemulgels entrap nanoemulsion droplets within a hydrated polymer matrix, thereby increasing viscosity, improving structural integrity, promoting sustained drug release, improved local drug concentration at the application site thereby resulting in overall performance [91,92]. From a physicochemical standpoint, this structural integration enhances kinetic stability by restricting droplet mobility and Brownian motion, which reduces the frequency of droplet collisions and mitigates destabilization processes such as coalescence, flocculation, and creaming, while polymer–surfactant interactions at the oil–water interface may further strengthen interfacial films through steric stabilization [93]. In addition, polymer–surfactant interactions can also change microstructure and drug partitioning, so polymer and surfactant levels should be optimized for each drug [94]. Although molecular diffusion-driven phenomena such as Ostwald ripening may still occur, the gel matrix significantly retards droplet growth by limiting macroscopic movement of the dispersed phase. Moreover, the hydrogel network plays a critical role in modulating drug release kinetics, as drug transport from nanoemulgels typically follows a multistep mechanism involving partitioning from the internal oil phase, diffusion through the polymeric gel matrix, and subsequent permeation across the skin barrier. This multilevel barrier often results in sustained or controlled drug release, enhanced skin retention, and prolonged local drug concentrations, making nanoemulgels particularly advantageous for dermal and transdermal delivery of drugs with short biological half-lives, frequent dosing requirements, or narrow therapeutic windows [95]. Importantly, increasing viscosity can enhance residence time, but excessive gel strength may reduce spreadability and hinder drug diffusion/permeation; hence, an optimal balance between retention and release/permeation is required for consistent therapeutic performance [96]. Accordingly, nanoemulgel development should be supported by practical performance testing, evaluation of skin tolerability and irritancy. In summary, nanoemulsion-based hydrogels effectively overcome limitations of conventional drug formulations and have gained increasing research interest due to their ease of application, good spreadability, non-sticky nature, safety, and therapeutic effectiveness.

5. Components of Nanoemulsion

The composition and maximum allowable concentrations of FDA-approved excipients used in nanoemulsion formulations are determined by the intended route and purpose of administration. The development of nanoemulsions is therefore restricted to components that are considered safe and generally recognized as safe (GRAS), including oils, surfactants, emulsifying agents, polymers, viscosity and density modifiers, and ripening inhibitors. Current evidence suggests that systemic exposure to most nanoemulgel excipients after topical use is typically low because the SC restricts the penetration of many surfactants and, especially, large hydrophilic polymers [97]. Since human pharmacokinetic data for nanoemulgel excipients after skin penetration are limited, regulators rely on conservative exposure assumptions, excipient history of use (e.g., Inactive Ingredients Database), irritation/sensitization testing, and, when needed, systemic safety assessments based on estimated exposure.

5.1. Oil Phase

The oil phase represents a critical component, as it serves as the primary solubilizing medium for lipophilic drugs and exerts a decisive influence on droplet size, drug loading capacity, release kinetics, and overall formulation stability [98]. The selection of an appropriate oil phase is guided by drug solubility, the required hydrophilic–lipophilic balance (HLB), the intended site of action, and safety considerations [99]. In dermal and transdermal systems, the oil phase also plays a key role in modulating skin permeation by interacting with SC lipids; certain oils act as penetration enhancers by disrupting the highly ordered lipid domains of the skin barrier, thereby facilitating drug transport [100]. For dermal applications, oils that favour localized drug retention with minimal systemic absorption are generally preferred, whereas transdermal formulations typically employ oils with strong permeation-enhancing capabilities [101]. When natural oils are used, HLB values greater than 10 generally favor the formation of oil-in-water nanoemulsions, while values below 10 tend to result in water-in-oil systems. The selection of an appropriate oil phase requires balancing its drug-solubilizing capacity with its ability to form a stable nanoemulsion system [102].

Typically, oil-in-water nanoemulsions contain 5–20% dispersed oil phase, although lipid concentrations as high as 70% have been reported in certain systems [103]. Due to their optical and mechanical characteristics, lipid-based interfacial films may be relatively thick, brittle, and translucent. Re-esterified fractions obtained from natural fixed oils such as coconut, sesame, sunflower, and cottonseed oils categorized as long, medium, and short-chain triglycerides are widely employed as oil phases to optimize solubilization and stability in nanoemulsion systems [104]. In addition, a wide range of synthetic lipids such as Capryol® 90, triacetin, isopropyl myristate, palm oil esters, isopropyl palmitate, Labrafil M1944CS, Maisine 35-1, Miglyol® 812, and Captex derivatives are frequently utilized in nanoemulsion formulations due to their favorable solubilization and formulation properties [105]. These lipid-based excipients are commonly classified as oil-phase components or lipophilic co-surfactants rather than conventional surfactants. Owing to their low HLB values and amphiphilic nature, these excipients enhance drug solubilization, facilitate self-emulsification, and contribute to nanoemulsion stability while also acting as penetration enhancers in dermal and transdermal formulations. Natural oils are widely used as oil-phase components in nanoemulsion formulations due to their excellent biocompatibility, ability to solubilize lipophilic drugs, and function as natural penetration enhancers. For example, cinnamon oil has been employed as the oil phase to dissolve tadalafil in a transdermal nanoemulgel developed for the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon, demonstrating effective transdermal delivery and offering a patient-friendly alternative to oral therapy [81]. Many essential oils also possess intrinsic antimicrobial and antioxidant properties that can improve formulation stability and therapeutic performance [106]. Nanoemulsions formulated with oils of very low aqueous solubility, and with optimized interfacial compositions, exhibit suppressed Ostwald ripening and improved kinetic stability, highlighting the importance of both interfacial properties and phase solubility in maintaining droplet uniformity over time. This interplay between interfacial flexibility and phase solubility is a key focus in contemporary nanoemulsion research aimed at enhancing long-term stability across pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic applications [107]. In summary, oil selection must balance drug solubilization with the intended dermal or transdermal effect, since highly permeation-enhancing oils may also increase irritation and reduce local retention [108]. Oils with higher aqueous solubility can promote Ostwald ripening, so long-term stability requires low-solubility oils and optimized interfacial composition. The key oil-phase components used in dermal and transdermal nanoemulsion formulations are depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of oil phases used in nanoemulsion systems for dermal and transdermal drug delivery.

5.2. Emulsifying Agents

The primary function of emulsifying agents is to facilitate nanoemulsion formation through multiple mechanisms, including reduction in interfacial tension, formation of a rigid interfacial film that acts as a mechanical barrier, and development of an electrical double layer that prevents droplet–droplet interactions. These mechanisms collectively maintain kinetic stability by inhibiting flocculation, creaming, coalescence, and phase separation [105]. The interfacial layer between the oil and water phases is critical for emulsion stability, as its physicochemical properties largely determine the behaviour of dispersed droplets. Characteristics such as interfacial layer thickness, structure, interactions among adsorbed emulsifiers, and interfacial rheological properties play a key role in the formation and stabilization of emulsions [109]. The polysaccharide emulsifier (e.g., pectin, alginate, xanthan, octenyl succinic anhydride) forms a thick interfacial layer that stabilizes the emulsion primarily through spatial repulsive forces. In contrast, globular proteins (e.g., soya and whey protein isolate, ovalbumin, bovine serum albumin) create thinner interfacial layers that stabilize emulsion droplets via a combination of electrostatic interactions and steric repulsion. Electrostatic stabilization occurs when emulsifying agents impart surface charges to dispersed droplets, creating repulsive forces that prevent coalescence, while steric stabilization is achieved when non-ionic surfactants or polymers form a protective, hydrated layer around droplets that acts as a physical barrier [110]. Electrostatic stabilization is sensitive to pH and electrolyte concentration, whereas steric stabilization is more robust under varying physiological conditions. In some formulations, emulsifying agents provide electrosteric stabilization by combining both mechanisms, resulting in enhanced emulsion stability. Phospholipids, commonly used as emulsifiers in the form of lecithin, are amphiphilic molecules that stabilize emulsions by adsorbing at the oil–water interface and reducing interfacial tension through interfacial film formation and electrostatic repulsion [111]. The selection of an appropriate emulsifier and its concentration is critical and should consider both the HLB and critical packing parameter, as these factors govern the formation of a stable, coherent, and flexible interfacial film that effectively prevents droplet coalescence [112]. Moreover, optimization of critical process parameters such as mixing conditions, order of addition, and temperature guided by Quality by Design principles, is essential to ensure consistent product quality and performance [113]. Based on the nature of the interfacial film formed, emulsifying agents may be classified as surface-active agents that form monomolecular films, hydrocolloid-based emulsifiers that produce multimolecular films, or finely divided solids that stabilize interfaces through particulate films. Proteins have been shown to act as effective emulsifiers in oil-in-water nanoemulsions by providing combined steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion; however, their stabilizing efficiency is highly sensitive to pH and ionic strength, particularly near their isoelectric point, where aggregation may occur [113]. In contrast, polysaccharides are generally less suitable for nanoemulsion stabilization due to their high-water solubility and moisture absorption, which result in poor barrier properties in liquid formulations [114]. Emulsifier performance is strongly influenced by conditions such as pH, ionic strength, temperature, and dilution, which can reduce interfacial stability in real-use settings [115]. Although higher surfactant levels may improve stability, they can increase irritation risk, so emulsifier choice must balance stability with safety and scalability [116].

5.3. Surfactant/Cosurfactant

Surfactants and co-surfactants play a pivotal role in the formation and stabilization of nanoemulsions by markedly reducing interfacial tension between the immiscible oil and aqueous phases and facilitating the generation of nanosized droplets. The flexibility and resilience of the interfacial film formed by surfactant molecules are critical for the kinetic stability of nanoemulsions, as the interfacial film can rapidly reorganize following mechanical disturbance, maintain coverage of nascent oil–water interfaces, and reduce interfacial tension gradients that drive droplet coalescence [117]. Surfactants adsorb at the oil–water interface to form a dynamic interfacial film, while co-surfactants penetrate and fluidize this film, increasing its flexibility and enabling spontaneous curvature necessary for nanoemulsion formation. Short and medium-chain alcohols such as ethanol, butanol, pentanol, isopropanol, and propylene glycol were used as cosurfactants to lower interfacial tension and enhance interfacial fluidity, while also modifying the solubility of both the aqueous and oil phases through phase partitioning [118]. For instance, co-surfactants, typically short-chain alcohols or glycols, penetrate the surfactant monolayer, reduce packing constraints, and increase interfacial fluidity and elasticity, thereby facilitating spontaneous emulsification and minimizing droplet coalescence [119]. Other cosolvents/cosurfactants included polyethylene glycol (PEG) 400 and Transcutol® HP. The synergistic action of surfactant and co-surfactant also expands the nanoemulsion existence region in pseudo-ternary phase diagrams and enhances the solubilization of lipophilic drugs within the interfacial region. Additionally, the presence of a co-surfactant allows for a reduction in the total surfactant concentration, thereby improving biocompatibility and reducing irritation potential. Collectively, these effects contribute to improved kinetic stability, enhanced drug loading capacity, and overall performance of nanoemulsions across different delivery systems, including dermal and transdermal routes. The preparation of nanoemulsions is significantly influenced by the selection and concentration of an appropriate surfactant, which facilitates rapid adsorption at the oil–water interface and stabilizes the newly formed nanoscale droplets that are subjected to high Laplace pressure often in the range of 10–100 atmosphere [120]. In addition to these interfacial effects, Ostwald ripening remains a dominant destabilization mechanism in nanoemulsions, driven by molecular diffusion of oil from smaller to larger droplets due to differences in chemical potential at curved interfaces.

Depending on their HLB, non-ionic surfactants such as polysorbates (Tween® 20, 80), sorbitan esters (Span® series), Lauroglycol®90, Cremophor®EL, or Cremophor®RH 40 are most commonly employed due to their greater physicochemical stability, safety, formulation flexibility, low toxicity, relative insensitivity to pH and ionic strength, superior emulsification efficiency, steric stabilization, and biocompatibility [59,121,122]. Polyoxyethylene sorbitan esters (Tween 20, 40, 60, and 80) are commonly used to stabilize oil-in-water (o/w) nanoemulsions, owing to their high HLB values. Combining high-HLB (e.g., Tween 80) and low-HLB (e.g., Span 20) non-ionic surfactants has been shown to improve interfacial film flexibility, resulting in smaller droplet size, enhanced stability, and controlled drug release through the SC. Non-ionic surfactants are increasingly paired with oils such as medium-chain triglycerides, isopropyl myristate, or essential oils, enhancing skin permeation while maintaining formulation mildness [123]. A recent pharmaceutics review notes that non-ionic surfactants dominate many nanoemulsion/microemulsion studies, largely due to pH insensitivity and established safety and it frames current formulation practice around commonly accepted non-ionic systems and ternary diagram approaches [124]. In contrast, sorbitan esters (Span 20, 40, 60, and 80), with lower HLB values, are frequently utilized as co-surfactants in water-in-oil (w/o) systems. Polyoxyethylene ether surfactants such as Brij® 97 provide strong steric stabilization through hydrated PEG chains, enhancing nanoemulsion stability [125]. Polyglycerol esters of fatty acids exhibit high emulsification efficiency and improved tolerance to environmental stress conditions, while sugar-based surfactants such as sucrose monopalmitate are favored for their excellent safety profile, biodegradability, and regulatory acceptance. As reported in the literature, the irritation potential of surfactants is closely related to their aggregation behavior [126]. Highly irritating surfactants such as cocamidopropyl betaine and sodium alkyl benzene sulfonate form smaller and less stable aggregates, whereas moderately irritating surfactants such as lauroyl glucoside and sodium lauroyl sarcosinate form larger, more stable self-assembled structures in aqueous solutions.

Conversely, anionic surfactants (e.g., sodium lauryl sulfate, sodium dodecyl sulfate) and cationic surfactants (e.g., β-lactoglobulin) primarily stabilize nanoemulsion droplets through electrostatic repulsive forces, thereby reducing droplet aggregation. However, their performance is highly dependent on pH and ionic strength, and charge screening in the presence of electrolytes may compromise emulsion stability. Moreover, ionic surfactants are associated with membrane disruption, protein denaturation, and mucosal irritation at higher concentrations, which limits their applicability in formulations requiring elevated surfactant levels, particularly for parenteral, ocular, and mucosal delivery systems. Zwitterionic surfactants such as lecithin exhibit high interfacial activity and form compact interfacial films due to the presence of both positive and negative charges within the same molecule. These surfactants offer advantages including biodegradability, foam stability, low critical micelle concentration, high water solubility, and reduced irritation and toxicity compared to ionic surfactants. Nevertheless, their widespread pharmaceutical use is often constrained by higher production costs and variability in composition compared to synthetic non-ionic surfactants [127]. It is worth noting that even if small amounts of synthetic surfactants (e.g., Poloxamers) reach the viable epidermis/dermis and enter systemic circulation, these excipient classes are widely used and well evaluated in safety assessments. Any systemically absorbed PEG-like fractions are generally expected to be cleared mainly via renal excretion, with clearance influenced by molecular weight [128].

A liquid crystal nanoemulsion is a novel emulsion system in which emulsifier molecules self-assemble at the oil–water interface into a lamellar liquid crystalline structure resembling the lipid organization of the SC. Such nanoemulsions can be prepared by microfluidization of liquid crystal emulsions stabilized with hydrogenated lecithin and phytosterols, while retaining their ordered lamellar interfacial structure [129]. A recent study suggest replacing/combining conventional ethoxylated non-ionics with sugar-based surfactants such as alkyl polyglucosides and related glucosides (e.g., coco-glucoside) to improve biodegradability and skin/ocular tolerability while maintaining emulsification performance [130]. Another work highlights polyglycerol-based nonionic surfactants used with microfluidization, where formulation components (e.g., glycerol) and surfactant architecture are tuned to achieve uniform, small droplet sizes and improved stability [131].

Surfactant/cosurfactant selection improves droplet size and stability but may increase irritation or membrane disruption, particularly with alcohol cosurfactants and ionic surfactants [132]. Electrostatic stabilization can fail in electrolyte-rich or diluted conditions, and Ostwald ripening may still compromise long-term stability unless oil solubility and interfacial composition are optimized.

5.4. Auxiliary Agents

In addition to the fundamental components, pharmaceutical nanoemulsions often include auxiliary excipients to improve formulation performance and stability [133]. For example, cosolvents such as propylene glycol or PEG derivatives are used to enhance drug solubility and reduce interfacial tension, while viscosity-modifying polymers, including polysaccharides and proteins, are commonly incorporated into nanoemulsions to enhance stability and improve textural properties [134]. In nanoemulsions containing a lower-density oil phase, density modifiers or ripening inhibitors, such as sucrose acetate isobutyrate, are added to prevent creaming [135]. Additionally, incorporation of highly hydrophobic long-chain triglycerides into the dispersed phase reduces oil solubility in the aqueous phase and suppresses Ostwald ripening, which is particularly important in oil-in-water nanoemulsions formulated with slightly water-soluble oils such as essential oils and flavor compounds [104]. Furthermore, preservatives and antioxidants are incorporated to inhibit microbial growth and oxidative degradation, respectively, and buffers or pH modifiers ensure physiological compatibility and maintain stability during storage and administration [136,137]. In specialized systems, solubilizers (soluplus®) and penetration enhancers/cosolvents (carbitol®, dimethylacetamide), targeting ligands (e.g., hyaluronic acid, folic acid, ceramides, and arginine–glycine–aspartic acid peptides), or cryoprotectants (e.g., trehalose, mannitol, and polyvinylpyrrolidone) may be included to optimize bioavailability, site-specific delivery, or stability during drying processes [138]. These additional components are critical in tailoring nanoemulsion formulations for diverse therapeutic applications and improving their physicochemical and biological performance. Auxiliary excipients can improve nanoemulsion stability and performance, but they also add formulation complexity and may introduce compatibility, safety, and regulatory challenges.

5.5. Gelling Agents

Gelling agents play a crucial role in the conversion of nanoemulsions into nanoemulgels by imparting appropriate viscosity, structural stability, and semisolid consistency required for topical application [139]. These polymers form a three-dimensional network within the continuous phase, entrapping nanoemulsion droplets without compromising their nanoscale characteristics. The incorporation of a suitable gelling agent enhances formulation spreadability, improves physical stability by reducing droplet mobility, and prolongs residence time at the site of application. In addition, certain gelling agents exhibit bioadhesive and permeation-enhancing properties, facilitating prolonged drug–skin contact and improving dermal penetration. The selection of the gelling agent and its concentration significantly influences the rheological behavior, drug release profile, and overall therapeutic performance of nanoemulgels. Carbopol polymers (e.g., Carbopol 940, 934, and Ultrez® 21), typically used at low concentrations (0.1–1.5%), are the most commonly employed gelling agents due to their high thickening efficiency, favorable rheological properties such as spreadability, and excellent compatibility with nanoemulsion systems [140]. Due to their high molecular weight, gelling polymers such as Carbopol® have minimal percutaneous absorption, so they primarily act locally as viscosity modifiers rather than as systemically absorbed or metabolized components [141]. Their widespread use as inactive ingredients in approved products also indicates strong regulatory familiarity when used within acceptable concentration ranges. Cellulose derivatives such as carboxymethyl cellulose (3–6%) and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (2–6%) are also widely utilized owing to their biocompatibility, neutral, resistant to microbial growth, non-irritant nature, and ability to impart desirable pseudoplastic flow behavior. In addition, Pluronic® F127 (20–30%) and chitosan have been explored as alternative gelling matrices, offering thermoreversible gelation, bioadhesive characteristics, and, in some cases, enhanced drug permeation [142]. Collectively, these gelling agents enhance formulation viscosity, physical stability, spreadability, and skin retention, thereby improving topical drug delivery and therapeutic efficacy. Gelling agents enhance stability and skin residence time, but overly high polymer levels can reduce spreadability and drug diffusion, so the viscosity–permeation balance must be optimized [143]. Polymer choice also affects compatibility, pH/ionic sensitivity, microbial risk, and long-term rheological stability, which should be verified under realistic storage and use conditions.

6. Preparation Methods

Nanoemulsions for topical drug delivery are prepared using high-energy or low-energy emulsification methods.

6.1. High Energy Methods

High-energy methods are widely used for nanoemulsion preparation, employing intense mechanical energy to overcome interfacial tension between the oil and aqueous phases and reduce coarse emulsion droplets into stable, uniformly dispersed nano-sized droplets typically ranging between 20 and 200 nm. Common high-energy techniques include high-pressure homogenization (HPH), microfluidization, and ultrasonication.

6.1.1. High Pressure Homogenization

In HPH, the coarse emulsion is forced through a narrow valve under very high pressure, generating shear stress, turbulence, and cavitation that break droplets into nanoscale sizes. For instance, HPH effectively produced stable limonene nanoemulsions by reducing droplet size to the nanoscale through intense shear, cavitation, and droplet collisions, outperforming other emulsification methods and maintaining stability for 28 days at room temperature [144]. A commercial high-pressure valve homogenizer with controllable pressure, nozzle geometry, flow pattern, and back pressure was systematically assessed to identify key operating parameters influencing nanoemulsion formation [145]. The results showed that higher homogenization pressure, multiple passes, increased back pressure, and higher emulsifier-to-oil ratios significantly reduced droplet size, with reverse flow configurations yielding slightly smaller droplets than parallel flow. The technique’s performance also depended on emulsifier type, with plant, animal, and synthetic emulsifiers exhibiting different size reduction efficiencies. Droplet size generally decreases as homogenization pressure, number of passes, back pressure, and the emulsifier-to-oil ratio increase, although the outcome also depends on the flow configuration and the emulsifier type [145].

6.1.2. Ultrasonic Homogenization

It employs acoustic cavitation, where the collapse of microbubbles produces intense shear forces leading to droplet disruption. A study reported that ultrasonic emulsification is an efficient nanoemulsion technique for preparing phase change material nanoemulsion, where the formulation was optimized by controlling key process variables, namely ultrasonic amplitude, treatment time, and surfactant concentration [146]. Among these, surfactant concentration had the greatest influence, followed by ultrasonic amplitude and treatment time, on droplet size and viscosity. At optimized process conditions, ultrasonication produced stable nanoemulsion with droplet sizes around 118 nm, outperforming rotor–stator homogenization and phase inversion temperature (PIT) methods in terms of emulsion stability and lower viscosity, thereby demonstrating its suitability for high-performance nanoemulsion production. A stable water-in-oil nanoemulsion containing a phenolic-rich olive cake extract was prepared using two nanoemulsion techniques, ultrasonic homogenization and rotor–stator mixing and optimized using response surface methodology [147]. Ultrasonic homogenization at 20% amplitude for 15 min produced nanoemulsion with smaller droplet size (~105 nm) and lower polydispersity index (PDI), indicating superior droplet uniformity compared with rotor–stator mixing, which required high shear (20,000 rpm for ~10 min) to achieve a comparable size range.

An in-depth investigation examined the ultrasonication technique and proposed the existence of a constant optimal ultrasonication time that is largely independent of processing conditions [148]. Using oil-in-water nanoemulsion as a model system, the results showed that product parameters (oil and surfactant composition) significantly influenced droplet size and stability, whereas ultrasonication time, beyond a certain point, did not further reduce droplet size. An optimal ultrasonication time of ~10 min was identified and found to be consistent across different amplitudes, volumes, and oil systems. Ultrasonication was effectively used to prepare eucalyptus oil nanoemulsions by optimizing key process parameters, including sonication distance, amplitude, and time [149]. Under optimal ultrasonic conditions, nanoemulsion with a mean droplet size of ~19 nm, narrow size distribution, and high zeta potential were obtained. Ultrasonication significantly enhanced emulsion stability and antimicrobial activity compared to native eucalyptus oil, demonstrating its suitability as a simple and efficient method for nanoemulsion preparation. A recent investigation compared microfluidization and ultrasonication as nanoemulsion techniques by varying key process parameters [150]. Ultrasonication, optimized through amplitude and sonication time, produced smaller droplet sizes and showed superior emulsifying performance, protein adsorption, and thermal and centrifugal stability compared with microfluidization. In contrast, microfluidization, even at higher pressures and multiple cycles, resulted in larger droplets, indicating that ultrasonication was the more effective technique for generating stable, fine emulsions. Many studies suggest an optimal sonication time beyond which further processing gives little additional size reduction, emphasizing process and formulation optimization for reproducibility [148].

6.1.3. Rotor–Stator Emulsification (RSE)

RSE is also referred to as high-speed homogenization or colloid mill variants, employs rapid rotation of a rotor within a stationary stator to create strong shear forces, enabling efficient droplet disruption during the pre-emulsification stage. A study reported that rotor–stator homogenization can be used as an effective alternative to HPH for the production of food-grade nanoemulsions [151]. The study highlighted that, unlike HPH, which are energy and maintenance-intensive and mainly suitable for dilute, low-viscosity systems, RSE can produce dilute to concentrated nanoemulsions with droplet sizes in the range of 100–500 nm. Moreover, it was demonstrated that modified starch produced stable nanoemulsions due to rapid interfacial adsorption, while gum arabic led to larger droplets because of drop–drop coalescence during emulsification. Investigation revealed that hydrodynamic cavitation employing a rotor–stator reactor is an efficient technique for the continuous production of oil-in-water nanoemulsions for skincare applications [152]. The integration of a 3D-printed rotor and optimization of key process and formulation variables including rotor speed, flow rate, surfactant concentrations, and oil content enabled the generation of submicron nanoemulsions (~366 nm). RSE is scalable and practical but often produces larger, less uniform droplets than HPH, sometimes requiring additional processing [153]. High shear may also promote coalescence and thermal/oxidative stress, so emulsifier choice and operating conditions must be optimized for stable nanoemulsions.

6.1.4. High-Pressure Microfluidic Homogenization (Microfluidization)

Microfluidization technique reduces droplet size by forcing the coarse pre-emulsion through microchannels (interaction chambers), where controlled impact, intense shear, and turbulence produce nanoemulsions with narrow size distribution. Microfluidization has been widely employed as an efficient high-energy technique for the preparation of nanoemulsions containing poorly water-soluble bioactive compounds [154]. In this context, andrographolide-loaded nanoemulsions were produced by optimizing homogenization pressure and the number of processing cycles, which enabled control over droplet size, PDI, and surface charge. Optimal nanoemulsions were obtained at 20,000 psi with five cycles, demonstrating that microfluidization is a robust and scalable technique for generating stable, uniform nanoemulsions suitable for topical delivery systems.

6.1.5. Hybrid or Combined High Energy Techniques

An integrated HPH system combining piston-gap and microfluidic technologies demonstrated its effectiveness as an advanced non-thermal nanoemulsification technique for lemon emulsions [155]. Application of this technique at 200–400 MPa reduced droplet size to the sub-500 nm range, enhanced emulsifying efficiency, and produced physically stable nanoemulsions with improved electrostatic stability. In addition, combined high-energy sequences such as ultrasonication followed by HPH, or high-speed mixing prior to HPH are increasingly used to improve process efficiency, reduce the number of homogenization cycles, and achieve superior droplet size uniformity. Comparative evaluation of ultrasound-assisted emulsification (UAE), HPH, and high-speed homogenization showed that UAE and HPH are more effective techniques for producing high-quality protein-stabilized oil-in-water emulsions than high-speed homogenization [156]. Among them, UAE emerged as the superior technique, yielding the smallest droplet size, highest interfacial protein adsorption, and best storage stability, indicating its strong potential for fabricating fine and stable nanoemulsions. An investigation was carried out to evaluate combined ultrasonication and HPH as an efficient technique for preparing stable oil-in-water nanoemulsions with reduced energy input [157]. Sequential application of ultrasonication and HPH at low to medium energy densities produced nanoemulsions with smaller droplet sizes and higher stability than those obtained using individual high-energy ultrasonication or HPH treatments. The results further indicated that ultrasonication prior to HPH was the most effective configuration, highlighting hybrid ultrasonication–HPH processing as a superior and energy-efficient nanoemulsion preparation technique. Thus, microfluidic homogenization and hybrid high-energy approaches can generate nanoemulsions with small droplet size and narrow PDI, improving stability and suitability for topical delivery [158]. However, superiority claims should be interpreted cautiously because performance is formulation-dependent and may be limited by heat and energy input, equipment cost, and instability during thickening with gelling agents arising from pH, electrolytes, and polymer–surfactant interactions.

High-energy methods offer advantages such as good control over droplet size, narrow size distribution, and scalability, making them suitable for pharmaceutical applications, including oral, parenteral, and topical drug delivery systems. However, they may have limitations such as high energy consumption, equipment cost, and potential thermal or mechanical degradation of heat-sensitive drugs. Overall, high-energy methods are robust and reliable approaches for producing pharmaceutically acceptable nanoemulsions with enhanced stability and bioavailability. Table 3 provides an overview of commonly used high-energy methods for nanoemulsion preparation.

Table 3.

An overview of frequently used high-energy methods for nanoemulsion preparation, summarizing their principles, key variables, advantages, and limitations.

6.2. Low Energy Methods

Low-energy emulsification methods are widely employed in the preparation of nanoemulsions intended for cutaneous drug delivery systems due to their simplicity, low cost, and avoidance of sophisticated high-shear equipment. Unlike high-energy methods, these techniques rely on the intrinsic physicochemical properties of the system, such as interfacial tension and phase behavior, to generate nanosized droplets. Such approaches are particularly advantageous for thermolabile drugs, bioactives, and cosmetic–pharmaceutical formulations. Frequently used low-energy methods include phase inversion composition (PIC), PIT, spontaneous emulsification, self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS), DPE, and aqueous titration method.

6.2.1. Phase Inversion Temperature

PIT method exploits the temperature-dependent solubility of surfactants, wherein oil, water, and the surfactant are heated with continuous stirring until the PIT is reached, followed by rapid cooling (e.g., ice-bath quenching) to form nanoemulsions [163]. Nanoemulsions prepared by the PIT method typically employ non-ionic surfactants containing temperature-sensitive polyoxyethylene chains, whose hydration–dehydration behavior governs phase inversion. The hydrophilic–lipophilic behavior of nonionic surfactants is strongly temperature dependent due to changes in the hydration of their poly(oxyethylene) chains. At low temperatures, these surfactants exhibit positive spontaneous curvature, leading to the formation of direct (oil-in-water) structures, whereas at high temperatures, dehydration of the ethoxylate chains results in negative spontaneous curvature and reverse (water-in-oil) structures. At an intermediate temperature, known as the HLB or PIT, the spontaneous curvature approaches zero, promoting the formation of bicontinuous microemulsions or lamellar liquid crystalline phases. At this temperature, ultra-low interfacial tensions are achieved, which significantly enhance emulsification efficiency [164]. Recent evidence shows that surfactants containing short polyoxypropylene chains can also be effective, as their temperature-dependent hydration enables phase inversion [165]. Polyoxypropylene-based surfactants with approximately 2.5–6.1 units produce stable oil-in-water nanoemulsions with spherical droplets in the 20–300 nm range, highlighting the importance of surfactant molecular architecture in PIT-based nanoemulsion formation. It is worthwhile to note that significant non-linear PIT behavior was observed with commercial ethoxylate surfactants, deviating from the assumed linear PIT-composition relationship [166]. This non-linearity, attributed to oil-like components within the surfactants, highlights the limitations of PIT-based linear mixing assumptions and underscores the need to refine hydrophilic–lipophilic deviation predictions for complex commercial surfactant systems. The type of emulsion obtained depends on the relationship between the PIT and the intended storage temperature of the final product, commonly 25 °C for room-temperature formulations. Systems prepared close to the PIT are thermodynamically sensitive; therefore, stability can be improved by incorporating cosurfactants or by adjusting the PIT using inorganic salts [167]. Complete solubilization of the oil phase within a bicontinuous microemulsion during PIT processing results in oil-in-water nanoemulsions with small droplet size and low PDI compared to PIC method [168]. A benidipine-loaded oil-in-water nanoemulsion was successfully developed using the PIT method and optimized by a Box–Behnken design [169]. Optimization of oil, surfactant, and glycerol concentrations produced a stable, transparent nanoemulsion with nanosized droplets (~97 nm), enhanced in vitro drug diffusion, and spherical morphology. Statistical analysis confirmed the significant influence and validity of all formulation variables, demonstrating the effectiveness and cost-efficiency of the PIT method for nanoemulsion development. Similarly, cajeput essential oil nanoemulsions were successfully prepared using the PIT method [170]. Optimization of surfactant type, concentration, oil content, and temperature identified a PIT of ~85 °C, with Tween 80 producing stable nanoemulsions containing up to 10% oil that remained physically stable for over 120 days. PIT-based nanoemulsions are especially suitable for topical and transdermal applications due to their small droplet size, uniformity, and enhanced skin permeation, although careful temperature control is required. Its key limitation is strong temperature and formulation sensitivity since commercial surfactants can show non-linear PIT behavior [166]. In addition, products stored near PIT may be unstable unless PIT is shifted with cosurfactants/salts and tightly controlled.

6.2.2. Phase Inversion Composition

In the PIC method, or emulsion inversion point method, nanoemulsions are formed by gradually changing the system composition, typically through controlled addition of the aqueous phase to a pre-mixed oil–surfactant mixture at constant temperature under gentle stirring [171]. This compositional variation alters the surfactant curvature from favoring water-in-oil to oil-in-water structures, passing through near-zero curvature intermediates such as bicontinuous microemulsions or lamellar phases, ultimately resulting in the formation of nanosized droplets. Numerous studies have associated nanoemulsion formation via the PIC method with phase transitions involving lamellar and/or bicontinuous phases [172]. The manner and duration of transition through these intermediate phases determine the efficiency of emulsification, ultimately influencing both droplet formation and the final size distribution of the nanoemulsion. During the transient stage, controlled water addition and adequate shear are required to ensure efficient droplet breakup, as inadequate mixing or improper residence time can result in polydisperse nanoemulsions [173,174]. Although this procedure appears similar to self-emulsification, the mechanisms differ fundamentally, as PIC involves a progressive change in surfactant spontaneous curvature, whereas self-emulsification occurs without curvature inversion. In contrast, surfactant-free self-emulsification phenomena, such as the Ouzo effect, generally yield nanoemulsions with low oil volume fractions, which can restrict their applicability in pharmaceutical formulations. PIC is particularly attractive for dermatological formulations as it can be performed at ambient temperature, minimizing drug degradation and allowing easy scale-up. Under optimized conditions, the PIC method produced well-dispersed, spherical nanodroplets with very small particle size and low PDI, demonstrating good kinetic stability over storage. This method is also referred to as catastrophic inversion, as it involves a progressive increase in the volume fraction of the dispersed phase. A composition-sensitive polyoxypropylene-based surfactant was employed as an emulsifier to prepare n-dodecane-in-water nanoemulsions via the PIC method [175]. Control of surfactant concentration, oil-to-surfactant ratio, and electrolyte content enabled effective control over droplet size and morphology. These findings demonstrated that the PIC method is a versatile and efficient strategy for producing stable nanoemulsions using composition-responsive surfactants, with strong potential for large-scale and industrial applications. Ginger oil-in-water nanoemulsions were prepared using the PIC method with Tween 80 as the emulsifier [176]. The influence of key processing parameters, including stirring rate and water addition rate, on nanoemulsion characteristics was systematically optimized using response surface methodology.

6.2.3. Spontaneous Emulsification

The spontaneous emulsification or self-nanoemulsification method involves the formation of nanosized droplets when an oil phase containing a surfactant is mixed with an aqueous phase containing a cosurfactant [177]. The rapid diffusion of water-miscible components, such as the solvent, surfactant(s) from the oil phase into the aqueous phase generates intense interfacial disturbances, increasing the oil–water interfacial area. This leads to the spontaneous formation of fine oil droplets when the bicontinuous microemulsion phase disintegrates. Solvents promote nanoemulsion formation both in the presence and absence of surfactants; when surfactants are absent, the phenomenon is termed the ouzo effect [178]. The sequence of component addition does not critically affect the process, as nanoemulsion formation occurs spontaneously due to interfacial instabilities. Surfactant-free microemulsions form at specific compositional ratios within the “pre-ouzo” region [179]. Their dilution without phase transitions enables spontaneous nanoemulsification, a key industrial approach for producing nanoemulsions at a commercial scale. The energy required to form new droplets depends on the interfacial tension and the number and size of droplets formed; systems with lower interfacial tension require less energy to emulsify. In theory, only mild agitation is needed for spontaneous emulsification, as the chemical potential difference between the oil and water phases is sufficient to initiate droplet formation. However, in practice, some formulations require gentle heating or cooling to trigger phase inversion and facilitate emulsification, particularly in temperature-sensitive systems. Despite extensive investigation, the mechanism of spontaneous emulsification remains unclear, as emulsification has been observed even without surfactants, indicating that interfacial turbulence alone does not fully explain the process [180].

6.2.4. Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems (SEDDS)