Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is increasingly recognized as a significant comorbidity in people living with HIV (PWH), contributing to increased morbidity and mortality. Epidemiological studies indicate that PWH have a 1.2–2-fold higher risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and other CVD events compared to HIV-negative individuals. While the mechanisms underlying HIV-associated CVD are not fully understood, they are likely to include a combination of cardiovascular-related adverse effects of HIV medications, vascular dysfunction caused by HIV-induced monocyte activation, and cytokine secretion, in addition to existing comorbidities and lifestyle choices. This comprehensive review examines the complex relationship between HIV infection and CVD, highlighting key pathophysiological mechanisms such as chronic immune activation, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and the role of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in promoting cardiovascular risk. Alongside conventional risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, HIV-specific elements, especially metabolic abnormalities associated with ART, significantly contribute to the development of CVD. Prevention strategies are crucial, focusing on the early identification and management of cardiovascular risk factors as well as optimizing ART regimens to minimize adverse metabolic effects. Clinical guidelines now recommend routine cardiovascular risk assessment in PWH, emphasizing aggressive management tailored to their unique health profiles. However, challenges exist in fully understanding the cardiovascular outcomes in this population. Future research directions include exploring the role of inflammation-modulating therapies and refining sustainable prevention strategies to mitigate the growing burden of CVD in PWH.

1. Introduction

In 2023, 39.9 million patients were living with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Most of them are adults aged 15 years or older, 38.6 million. Children aged 0 to 14 years form a small proportion of all patients with HIV, 1.4 million. Women and girls constituted 53% of the total patients with HIV (PWH). In 2023, 86% (ranging from 69% to 98%) of individuals living with HIV were aware of their HIV status. Moreover, around 5.4 million individuals remained unaware of their HIV status [1].

HIV is a retrovirus from the genus Lentivirus that targets human T-cells [2,3]. It can use reverse transcription to convert its RNA genome into DNA. The DNA integrates into the genome of the host cell, promoting the virus’s growth and survival inside the human body. Chronic infection mainly affecting CD4+ T-cells is characterized by increasing lymphocyte death. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a disorder characterized by specific symptoms resulting from immune system failure due to a reduced T-cell count [4].

PWH persistently exhibits an increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD), encompassing systolic heart failure (HF), atherosclerotic heart disease, and diastolic HF, compared to the general population [5,6,7,8,9]. Several mechanisms contributing to heightened atherogenesis and HF have been suggested, including elevated systemic inflammation, impaired autophagy, oxidative stress, direct impacts of viral proteins, inflammasome activation, and endoplasmic reticulum stress [10,11]. Observational studies have identified HIV viremia, immunosuppression, and HIV-associated dyslipidemia as variables that may predispose people with HIV to CVD [5,7,8,12,13,14,15].

Access to life-sustaining combination ART enables individuals with HIV to live longer, thereby elevating their risk for age-related illnesses, including CVD. According to the ATHENA cohort, 78% of PWH will be diagnosed with CVD, and the median age on ART is expected to rise from 43.9 years in 2010 to 56.5 years by 2030 [16]. Compared with HIV-uninfected individuals, people living with HIV have a higher relative risk of myocardial infarction—approximately 1.7-fold (RR~1.7) based on pooled estimates from recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses [17]. For both type 1 and type 2 acute MI events, the higher RR persists in people with viral suppression and may be more prominent in women than in men when it comes to coronary heart disease (CHD) [18]. Despite reduced absolute incidence of acute MI in those with fewer risk factors, the RR of acute MI remains elevated in PWH, including those in optimal heart health [19]. Ischaemic stroke constitutes over 80% of all strokes in individuals with HIV, with the remainder attributed to hemorrhagic stroke [20].

So, we performed this study to elucidate the pathophysiology, risk factors in PWH, and clinical guidelines for the prevention and management of these cases.

2. Pathophysiology of HIV and Its Association with Cardiovascular Diseases

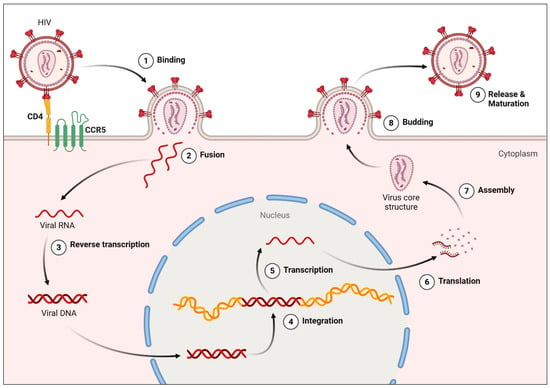

HIV undergoes multiple critical phases upon entering and persisting within a host organism. The host cell initially interacts with gp120, the viral envelope glycoprotein, via the CD4+ receptor and a chemokine co-receptor (CCR5 or CXCR4). This interaction facilitates viral attachment, fusion, and entry into the host cell. Reverse transcriptase, integrase, protease, and other enzymes are among the several enzymes that are released into the host cell’s cytoplasm during this process. By transforming the viral RNA genome into double-stranded DNA, reverse transcriptase helps integrate viral DNA into the host genome. This integration is an essential tactic the virus employs to escape the human immune system. Viral RNA and proteins are generated via transcription and translation of the integrated provirus. These are then released from the cell by budding. Immune cells inevitably disappear as the host cell’s function gradually declines. When the host’s immune system is significantly weakened, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) emerges, characterized by opportunistic infections and increased cancer susceptibility [21,22] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

HIV Replication Cycle. Step 1 involves engagement between the viral envelope glycoprotein gp120 and the host CD4 receptor, followed by viral attachment, fusion, and entry into the host cell. In step 3, reverse transcriptase converts viral RNA into double-stranded DNA, a process targeted by nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), which block viral DNA synthesis and prevent integration. The resulting viral DNA is integrated into the host genome, where transcription and translation produce viral RNA and proteins. Accumulation of viral products ultimately compromises host cell function, leading to depletion of CD4+ T-cells. Created in BioRender. Hetta, H. (2026) https://BioRender.com/yjca9s9 (accessed on 22 January 2026).

HIV infection disrupts gut mucosal integrity, leading to microbial translocation and systemic exposure to microbial products. Dysbiosis in the gut microbiome contributes to elevated circulating levels of metabolites such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), which has been linked to endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and accelerated atherogenesis in both the general population and PWH. These findings suggest that gut-derived metabolites may serve as mechanistic mediators connecting HIV-induced immune activation with cardiovascular risk. Recent studies found that higher plasma levels of the gut microbiome–related metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) were associated with greater progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis in people living with HIV, with positive correlations to biomarkers of monocyte activation and inflammation (e.g., sCD14, sCD163) [23]. Studies have investigated TMAO in relation to inflammation, microbial dysbiosis, and immune activation in HIV cohorts, reflecting the complex relationship between gut microbiota–derived metabolites and systemic immune responses in HIV infection [24]. The microbiota-dependent metabolite TMAO was found to correlate with markers of monocyte activation and microbial translocation in untreated HIV-infected individuals, suggesting a possible link between microbial products and cardiovascular risk modulators in HIV [25].

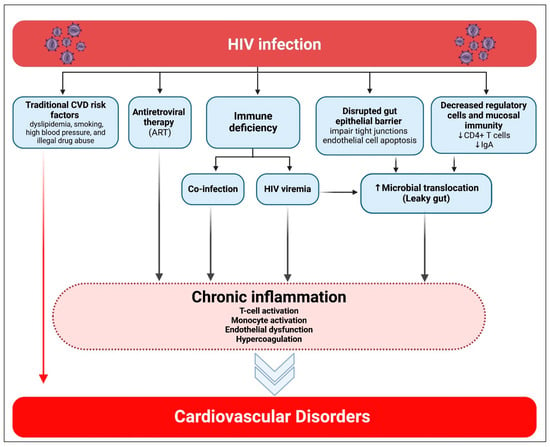

Mechanisms are anticipated to vary by type and subtype of CVD as well as by geographical region, influenced by factors such as availability to ART, lifestyle, endemic comorbidities, and genetic predispositions [26]. However, among PWH across various regions, two prevalent factors contributing to CVD risk are identified (Figure 2). The first factor is increased systemic immunological activation, which has theoretical significance in the pathophysiology of both CHD, MI, and HF. HIV represents a paradoxical condition of immunological suppression alongside increased systemic immune activation [27]. ART effectively suppresses viremia; nevertheless, contemporary ART inadequately reduces systemic immune activation and vascular inflammation. In PWH, indicators of systemic monocyte activation have been associated with arterial inflammation, which catalyzes both vascular and cardiac disease. A second significant contributor to CVD risk among PWH is metabolic dysregulation, potentially linked to HIV infection, HIV-related immunological activation, and/or the administration of specific ART [28,29]. According to recent findings, immune cells and adipocytes residing in adipose tissue play a role in the immune response to HIV infection [30,31]. Adipose tissue may serve as a reservoir for HIV in virologically suppressed persons because it contains infected CD4+ T cells and macrophages [31,32]. Furthermore, even in the face of viral suppression, HIV proteins are still present in the blood and adipose tissue. Research conducted in vitro suggests that adipocytes exposed to HIV proteins produce proinflammatory mediators [31,33]. HIV results in metabolic inefficiency and subcutaneous adipose tissue fibrosis, which produce ectopic fat redistribution to the visceral area. Visceral fat buildup increases the risk of CVD and causes insulin resistance [28]. Apart from the effects of ART, the direct association between adipose tissue and HIV results in a proinflammatory state and a disturbed metabolic and hormonal environment that increases the risk of CVD and other HIV-related non-communicable comorbidities [32].

Figure 2.

Association of HIV infection with cardiovascular diseases. Created in BioRender. Hetta, H. (2026) https://BioRender.com/opk308x (accessed on 22 January 2026).

HIV affects blood lipid levels, metabolism, and glucose homeostasis in addition to adipose tissue. HIV replication has a direct impact on host lipid metabolism. In a T cell line (in vitro), it induces cellular enzymes that enhance fatty acid synthesis, increase low-density lipoproteins (triglycerides), dysregulate lipid transport, oxidize lipids, and broadly alter lipid metabolic pathways [34]. Consistent with these mechanistic insights, higher HIV RNA levels were associated with lower LDL cholesterol and higher VLDL cholesterol and triglycerides. A history of AIDS-defining events was linked to higher total cholesterol, VLDL cholesterol, and triglyceride concentrations. Regarding glucose homeostasis, higher CD4+ counts were associated with less evidence of insulin resistance, suggesting that more advanced HIV disease is associated with less favorable lipid and glucose profiles [34,35]. Conversely, a Japanese cohort of men living with HIV (MHIV) patients who had not received treatment revealed a correlation between higher CD4+ counts and greater HDL- and LDL-C values [36]. Despite low LDL-C levels during the active replication phase, diminished HDL-C and elevated VLDL-C and triglycerides may elucidate the pro-atherogenic effects of HIV. So, HIV exemplifies a model disease for elucidating the roles of immunological activation and metabolic imbalance in the progression of CHD, MI, and HF [37].

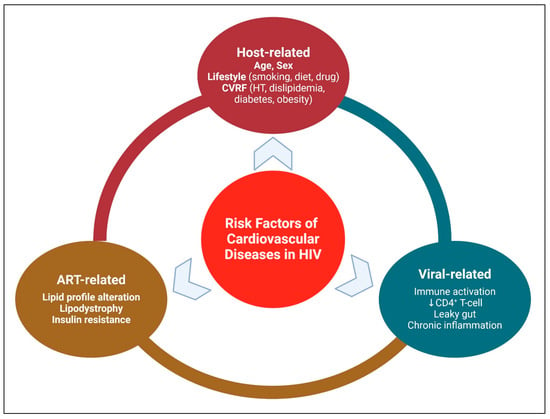

3. Risk Factors of Common Cardiovascular Diseases in HIV

Common risk factors of CVD in HIV can be categorized into 3 main categories: Patient-related, viral-related, and ART-related (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Diseases in HIV. Created in BioRender. Hetta, H. (2026) https://BioRender.com/ng596ew (accessed on 22 January 2026).

3.1. Cardiovascular Risk Stratification in HIV-Positive Patients

Population studies have firmly demonstrated that there are sex variations in the risk pathways for CVD [38]. Furthermore, different sexes experience HIV infection differently in terms of how it causes immunological activation and/or metabolic dysregulation [39,40]. Together, these two variables suggest that there are sex disparities in both HIV-related CV risk and CVD risks among PWH. Analyzing sex-specific characteristics associated with HIV-associated CVD risk is crucial for the successful implementation of HIV-specific CVD prevention strategies for both sexes. Women living with HIV (WHIV) exhibit the highest level of systemic immune activation as compared to MHIV, non-HIV-positive males, and women living without HIV [40]. WHIV, compared to MHIV, typically exhibits unique patterns of metabolic dysfunction [41]. Concurrent general population research indicates that women exhibit greater susceptibility than men to heightened immunological reactivity and distinct patterns of metabolic instability. Consequently, a deeper understanding of sex-specific processes of CVD risk in WHIV may provide insights into similar mechanisms in women within the general population.

In high-income countries, sex-stratified analyses of myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease incidence indicate that women living with HIV may have a disproportionately higher risk of HIV-associated cardiovascular complications compared with men. Triant et al. studied data from the Partners Healthcare System in the United States (US) regarding MI rates among 1,044,598 control participants (59 percent female) and 3851 PWH individuals (30 percent female) who were followed up from 1996 to 2004 [42]. Concerning WHIV, MHIV, non-HIV-infected women, and non-HIV-infected men, the unadjusted incidence rates of MI per 1000 person-years were 12.71, 10.48, 4.88, and 11.44, respectively. After adjusting for conventional CVD risk variables, the RR of MI in WHIV compared to those without was 2.98 (95% Cl 2.33–3.75), and the associated risk for MHIV compared to those without was 1.40 (95% Cl 1.16–1.67) [42]. Sex-stratified analyses from a French cohort produced similar results, corroborating the heightened risk of HIV-related CHD and MI in women [43].

In a high-income country, sex disparities in MI subtype presentations in perinatally HIV-positive individuals are highlighted by recent research conducted by Crane et al. [44]. To determine the likelihood of any clinical MI, Crane’s team evaluated data from 26,909 PWH patients who underwent testing at one of six US medical sites between 1996 and 2014. 288 occurrences were classified as definite or probable type II MI, while 362 instances were classified as definite or likely type I MI throughout the cohort. The subtype distribution in WHIV who had MI was 46% (69/150) type I and 54% (81/150) type II, suggesting that type II was slightly more common. On the other hand, the subtype distribution of MHIV people who had MI was 41% (207/500) type II and 59% (293/500) type I, suggesting a minor predominance of type I. Although type II MI is associated with rates of major adverse cardiovascular events, cardiovascular death, and all-cause mortality that are comparable to those observed after type I MI, as reported in a large general population study by Gaggin et al. [45], its overall prognosis remains unfavorable, in part due to the absence of standardized, evidence-based treatment strategies. This highlights the urgent need for public health initiatives to develop preventative methods for high-risk populations. These strategies must be considered in an understanding of sex-specific and population-specific physiology.

3.2. HIV-Specific Risk Factors (e.g., Chronic Immune Activation, ART Side Effects)

HIV’s early attack on mucosal CD4+ T cells in the gastrointestinal tract disrupts the epithelial barrier, allowing bacteria and microbial products to translocate into the portal and systemic circulation, thereby generating persistent immune activation. Biomarkers such as soluble CD14 (sCD14) and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP) reflect the degree of microbial translocation and have been linked to increased risk of CVD. Longitudinal cohort studies have shown that elevated sCD14 and LBP levels correlate with endothelial dysfunction, subclinical atherosclerosis, and higher incidence of cardiovascular events, providing quantitative evidence of their predictive value in HIV-associated CVD risk assessment [46,47,48]. Growing data indicates that HIV is linked to the movement of bacteria and other microbiological products from the intestines into the bloodstream, giving support to this idea. Even in individuals with virological suppression, this situation prolongs endothelial damage, persistent immunological activation, and CVD [49,50,51,52]. In PWH with suppressed viremia, microbial translocation may provoke a distinct immune activation profile characterized by elevated levels of CD38(+) CD8(+) T cells and soluble thrombomodulin, a hallmark of endothelial activation [53]. Microbial translocation has been linked to an increased risk of thrombosis and hypercoagulability, in addition to ongoing immunological activation, which could lead to CVD. Studies revealed that macrophages and platelets in PWH often express tissue factor, an activator of the coagulation cascade; lipopolysaccharides and flagellin can stimulate monocytes to produce tissue factor [54].

Microbial dysbiosis and the movement of bacteria and microbial metabolites in PWH have been linked to several mechanisms. Initially, the virus both directly and indirectly targets circulating and mucosal CD4+ T cells by activating cytotoxic CD8+ T cells to destroy infected CD4+ T cells. Early in the course of an infection, the number of CD4+ mucosal T cells in the gastrointestinal tract decreases [50]. Secondly, HIV may impair tight connections between enterocytes, as previously documented in simian immunodeficiency virus infection [55]. These events erode the mucosal barrier of the gastrointestinal tract, allowing commensal bacteria and their components to enter the bloodstream. HIV also causes crypt hyperplasia, bacterial overgrowth, and villous atrophy, which all affect gastrointestinal lumen permeability [51]. Because PWH have fewer intestinal immunoglobulin (Ig)A-producing B-cells, their luminal IgA levels are lower, which puts them at risk for bacterial overgrowth and translocation [56].

3.3. Traditional Cardiovascular Risk Factors (e.g., Smoking, Hypertension)

Compared with the general population, people living with HIV have a higher prevalence of traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as dyslipidemia, diabetes, smoking, and hypertension [57,58,59]. With a prevalence ranging from 4.8% to 73.4% in HIV patients, hypertension is a major risk factor for CVD [57]. Compared to Caucasians, African American PWH are more likely to have blood pressure regulation issues, which increases their vulnerability to adverse CV outcomes [60]. Endothelial function and integrity are altered by HIV-induced chronic inflammation, and the renin-angiotensin system is dysregulated in response to ART [61,62]. The prevalence of dyslipidemia among PWH ranges from 7.7% to 73.4%, with an average of 39.5% [57]. In this patient group, dyslipidemia may be caused by several mechanisms, such as hepatic de novo lipogenesis and increased basal lipolysis, reduced insulin efficiency in preventing adipocyte lipolysis, and impaired peripheral fatty acid trapping [63]. Moreover, PWH with diabetes mellitus or insulin resistance had a higher frequency of hyperlipidemia. Reduced HDL-C and high LDL-C are the markers of dyslipidemia in this population, with hypertriglyceridemia being the most common abnormality, particularly after ART initiation [64].

Older, rarely used ART might cause body fat to redistribute, showing up as either lipohypertrophy with increasing visceral fat or lipoatrophy in the face and limbs [65]. Because lipodystrophy is linked to hypertriglyceridemia, decreased HDL-C, dyslipidemia, increased insulin resistance, and diabetes mellitus, it is a substantial risk factor for CVD [65]. With a range of 0.5% to 39.1%, the average prevalence of diabetes mellitus is 7.24% [57]. It is associated with lipodystrophy, a low CD4+ count (<200 cells/μL), and the use of some older ART [66,67].

Smoking is prevalent among PWH, with a prevalence rate of 33% (ranging from 0% to 67%), resulting in significant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, a significant correlation exists between illegal drug use and CVD in those living with HIV [57]. Heroin, marijuana, cocaine, and methamphetamine are the most often used illegal substances in this population [68]. All of these substances can cause arrhythmias and coronary atherosclerosis. A developing problem among MHIV who have sex with males is chemsex, which is described as the use of recreational drugs (including cocaine, ketamine, mephedrone, gamma-hydroxybutyrate/gamma-butyrolactone, and crystal methamphetamine) to enhance sexual experiences [69]. Although the CV implications of chemsex remain unexamined, this practice may negatively impact the CV system, particularly through the direct effects of these substances on cardiac function [70].

In addition to patient-related factors, emerging evidence suggests that genetic polymorphisms in inflammatory genes, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, may contribute to sex-specific disparities in CVD risk among WHIV. These variants can influence levels of systemic inflammation and immune activation, potentially exacerbating the cardiovascular impact of HIV and ART in this population. Although current data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in PWH remain limited, these findings highlight an important avenue for future research and suggest that integrating genetic risk factors could eventually support personalized risk stratification and targeted prevention strategies [71,72,73,74].

5. Prevention and Management of Cardiovascular Diseases in HIV

Clinical data on CVD prevention strategies among HIV-positive people are essential in this context. Several studies conducted over the last 20 years have assessed the impact of statin treatment on several subclinical indicators of atherosclerosis and inflammation in HIV patients. The findings from these trials on vascular inflammation have been inconsistent. Nevertheless, statins seem to diminish specific inflammatory indicators and, as anticipated, lower atherogenic lipid levels (e.g., LDL-C) in PWH [94,99]. The effectiveness of statins in preventing severe atherosclerotic CHD endpoints in PWH is better understood thanks to the results of the randomized trial to prevent vascular events in HIV (REPRIEVE). Those with HIV who are at low to moderate risk of atherosclerotic CVD were randomized at random in REPRIEVE to receive a placebo or pitavastatin. 7500 PWH have been enrolled in this trial. The trial reported that the individuals had a median age of 50 years; the median CD4+ T cell count was 621 cells/mm3, and 5250 out of 5997 participants (87.5%) with available data had an HIV RNA result below quantitation. The REPRIEVE trial was stopped early following a recommendation by the Data and Safety Monitoring Board because pitavastatin significantly reduced the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) in PWH over a median follow-up of 5.1 years. 91 participants (2.3%) in the pitavastatin group and 53 participants (1.4%) in the placebo group reported experiencing muscle-related symptoms; 206 people (5.3%) and 155 participants (4.0%), respectively, reported having diabetes mellitus. This means HIV-infected participants administered pitavastatin exhibited a reduced risk of MACEs compared to those receiving a placebo, across a median follow-up period of 5.1 years [100].

The results of the REPRIEVE trial have had immediate and substantial implications for clinical practice. In contrast to earlier strategies that restricted statin therapy primarily to PWH at high estimated cardiovascular risk, the demonstrated reduction in MACEs with pitavastatin in a predominantly moderate- and low-risk population has prompted a paradigm shift toward broader primary prevention [100]. Accordingly, the updated European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) guidance recommends considering statin therapy for primary prevention in PWH with moderate and low cardiovascular risk, reflecting the trial’s demonstrated benefit [101]. These updated recommendations highlight the importance of proactive cardiovascular prevention strategies in PWH, even in the absence of overt high-risk profiles.

In comparison to statins, there is even greater ambiguity over other CVD prevention strategies for PWH. Current studies, which are not yet sufficiently powered for clinical objectives, are assessing the efficacy of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors in patients with HIV. A prospective study aimed to assess the correlation between HIV-related dyslipidemia in PWH on protease inhibitors and PCSK9, a key regulator of LDL-C homeostasis. In addition to 90 HIV-negative controls who were age and sex-matched, 103 HIV-positive patients had their plasma PCSK9 levels measured both before and after initiating PI-based ART. ELISA was used to measure PCSK9. The results showed that after using protease inhibitors for a median of 14 months, PCSK9 levels in HIV-positive people did not increase and were consistently greater than in controls at all time points assessed (adjusted p value before and after: <0.05). Total cholesterol, LDL-C, and HDL-C levels increased after protease inhibitors were added; however, LDL-C levels stayed lower than those of the control group. When compared to immunodeficiency and the severity of HIV disease, PCSK9 levels showed a positive correlation at baseline, as demonstrated by the HIV-1 viral load (p = 0.01), CD4 T-cell count <200/μL (p = 0.002), and stage C HIV disease (p = 0.0002). Protease inhibitor-treated individuals showed a higher correlation between PCSK9 levels and glycemia, HDL-C, LDL-C, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and then with HIV-related factors. This suggests that HIV-positive individuals have higher PSCK9 levels. HIV may have an effect, as evidenced by the correlation between PCSK9 levels and infection severity in ART-naive patients. When PI-containing ART was initiated, PCSK9 levels associated with dyslipidemia in virologically suppressed individuals were comparable to those observed in controls [102].

HIV-positive people were not included in the 2020 American Society of Hematology (ASH) guidelines for antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy. However, given the wealth of information regarding drug–drug interactions (DDIs) between ART and other medications, it is imperative to rigorously evaluate the possible interaction of antithrombotic therapies in PWH. PIs in particular, which make up the ART, have differing effects on the CYP450 liver enzymes that metabolize warfarin. As a result, careful INR monitoring is recommended. Warfarin DDIs vary, with some rising and others lowering levels. Individuals using lopinavir/ritonavir regimens need higher weekly warfarin dosages than those on efavirenz-based regimens, whereas HIV patients receiving therapy for tuberculosis need lower weekly warfarin dosages [103,104].

Recent evidence has explored the role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in populations historically excluded from major clinical trials, including PWH diagnosed with lung cancer [105]. There is a systematic review that synthesized data from multiple observational studies and case series to assess outcomes with programmed death-1 (PD-1) pathway blockade in this unique clinical context. The review demonstrated that PD-1 inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, exhibit comparable efficacy in PWH with lung cancer to that reported in HIV-negative populations, with objective response rates and progression-free survival outcomes aligning with historical benchmarks. Importantly, the safety profile was acceptable, with immune-related adverse events occurring at rates similar to those seen in the general lung cancer population and no consistent evidence of HIV disease progression or significant increases in opportunistic infections during therapy. These findings support the feasibility and clinical utility of PD-1 inhibition in PWH with lung cancer while also underscoring the need for prospective studies to further define long-term outcomes and optimal management strategies in this under-studied group [106].

PIs and pharmacological enhancers that inhibit CYP 450 enzymes have the potential to increase the concentration of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and increase the risk of bleeding. Treatment failure may result from the NNRTIs’ activation of CYP450 enzymes, which lowers the concentration of DOACs [107]. Careful selection should be used to manage interactions depending on patient characteristics; anticoagulants and ART with low risk of bleeding disorders should be used.

Additional anti-inflammatory treatments for patients with HIV are also important. These drugs aim to address gut health to diminish microbial translocation and intestinal inflammation, although they have not consistently influenced inflammation biomarkers in individuals with HIV. Additional therapies evaluated comprise canakinumab, an interleukin-1-beta (IL-1β) antagonist that diminished inflammatory markers and alleviated arterial and bone marrow inflammation in a limited study involving PWH. IL-1 primarily regulates a sequence of pro-inflammatory responses triggered by pathogen-induced tissue damage. Within the IL-1 family, IL-1β induces the overexpression of genes that enhance immune system activity and inflammatory response. Due to the increasing pathophysiological significance of IL-1β in various disease mechanisms, novel biological therapeutics have been discovered in recent years [108]. A drug that targets IL-1β, canakinumab, was recently approved for use in clinical settings. In this regard, the most recent results from the CANTOS trial are encouraging. The results show that, as compared to a placebo, anti-inflammatory treatment with canakinumab at a dosage of 150 mg given every three months significantly decreased the risk of recurrent CV events. These drugs’ ability to decrease cholesterol did not affect the outcomes. If the CANTOS trial’s findings were broadly applicable, they would support the idea that inflammation is the primary cause of atherothrombosis, which would mean that cytokine-targeted therapy is essential for secondary CVD prevention. Moreover, the potential benefits of canakinumab’s exceptional suppression of the inflammatory cascade must be carefully balanced against the drug’s unclear long-term safety profile [109].

Furthermore, methotrexate (MTX) marginally lowered CD8+ T cell counts in HIV-positive patients but did not affect inflammatory markers [110]. Recently, 176 HIV-positive patients on ART completed a low-dose methotrexate (LDMTX) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) to look at the drug’s anti-inflammatory and perhaps cardioprotective effects. The plasma levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, IP-10, d-dimers, CD14, CD163, and fibrinogen did not show any significant changes in response to LDMTX; the only significant change observed was a modest drop in the levels of vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM). Significant drops in circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts were the main immunologic effects of LDMTX [111]. The principal mode of action of these widely used anti-inflammatory medications in PWH is determined by an experimental study. In trial samples, T-cell morphology and other plasma inflammatory markers were assessed. MTX reduced cycling (Ki67+) T cells lacking Bcl-2, whereas plasma inflammatory cytokines stayed essentially unchanged. Through a series of in vitro experiments designed to clarify the mechanisms underlying MTX activity, it was found that MTX inhibited mitochondrial function, T cell proliferation following mechanistic targets of rapamycin (mTOR) activation, and cell cycle entrance rather than effector cytokine production. Daily folic acid administration did not lessen the inhibitory effect in trial participants. Given that the inhibitory effect was reversible with folinic acid, it appears that low-dose MTX predominantly inhibits T cell proliferation in vivo in PWH by dihydrofolate reductase inhibition [112].

In the absence of compelling facts to the contrary, it is recommended to employ risk-based strategies for CVD preventive therapy in PWH, acknowledging that as CVD risk escalates, the absolute and net benefits of statin therapy for CVD prevention also increase. Additionally, it is generally acknowledged that the early beginning of ART aids in managing dyslipidemia alongside the suppression of HIV viremia.

6. Clinical Guidelines and Recommendations on Managing Cardiovascular Risk in HIV Patients

Cardiovascular risk assessment is a cornerstone of preventive care in people with HIV (PWH). Current guidelines recommend estimating the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) using validated tools such as the ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Calculator, as outlined in the 2013 ACC/AHA cardiovascular risk assessment guidelines and the 2018 updates on cholesterol and blood pressure management [113,114]. Cholesterol-lowering therapy is indicated for individuals aged ≥21 years with established ASCVD or LDL-C ≥190 mg/dL, for adults aged 40–75 years with diabetes mellitus regardless of calculated risk, and for those with a 10-year ASCVD risk ≥7.5%.

Given that traditional risk scores tend to underestimate cardiovascular risk in PWH, the American Heart Association recommends adjusting calculated risk upward by approximately 1.5–2-fold to account for HIV-related factors. Alternative tools include the Framingham 10-year CVD risk score (treatment threshold ≥10%) and the HIV-specific D:A:D model (5-year risk ≥3.5%) [110]. More recently, the 2021 ESC/EAS guidelines introduced the SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP models to estimate fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular risk in individuals below and above 70 years of age, respectively, and highlight the increased susceptibility of PWH to coronary and peripheral vascular disease, particularly in those with CD4+ counts below 200 cells/mm3 [115].

Lipid management in PWH should follow ESC/EAS recommendations. Statin therapy is advised for patients with dyslipidemia to achieve LDL-C levels <70 mg/dL with at least a 50% reduction from baseline in high-risk individuals, while more stringent targets (<55 mg/dL) are recommended for those at very high risk or requiring secondary prevention [116]. The European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) 2021 guidelines further recommend annual cardiovascular risk assessment using Framingham or D:A:D scores in men over 40 years and women over 50 years. In PWH without established CVD but with a 10-year risk ≥10%, modification of antiretroviral therapy (ART) should be considered to avoid agents associated with increased cardiovascular risk, such as zidovudine or abacavir [117].

Optimization of ART is a key strategy for reducing cardiovascular risk. Evidence from large cohorts, including the SMART and D:A:D studies, indicates that certain antiretroviral agents—particularly protease inhibitors such as lopinavir/ritonavir and darunavir, as well as abacavir and didanosine—are associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke [80,98]. In patients at elevated cardiovascular risk, switching to regimens with more favorable cardiometabolic profiles, such as integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), is recommended. The REPRIEVE trial (2023) further underscored the benefit of statin therapy in PWH receiving ART, supporting a combined approach of ART optimization and lipid-lowering therapy for effective cardiovascular prevention [100].

Beyond pharmacologic interventions, cardiovascular risk reduction in PWH requires a comprehensive, multifaceted approach. Lifestyle modification remains foundational and includes smoking cessation, adherence to a heart-healthy diet, regular physical activity, and weight management. These measures reduce traditional cardiovascular risk factors while also improving metabolic and immune health [118]. Equally important is the systematic management of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome, which are highly prevalent in PWH and substantially amplify cardiovascular risk. Regular monitoring and early, aggressive treatment of blood pressure, glycemic control, and lipid abnormalities are essential to prevent long-term cardiovascular complications [119].

Finally, statins play an increasingly important role in primary cardiovascular prevention in PWH. Their use should be guided by individualized risk assessment using tools such as the ASCVD calculator, Framingham score, or D:A:D model, and informed by emerging evidence, including findings from the REPRIEVE trial [100]. In the presence of HIV-specific risk factors, statin therapy may be justified even in individuals classified as having moderate or lower traditional risk, with careful attention to LDL-C targets and potential drug–drug interactions with ART [118,119].

Overall, this integrated approach—combining accurate risk stratification, lifestyle modification, ART optimization, comorbidity management, and appropriate statin therapy—provides a structured framework for improving long-term cardiovascular outcomes in people living with HIV.

7. Future Research Directions

The care of CVD is still controversial. HIV is considered a significant CVD risk factor, so future research should focus on certain elements of the diagnosis and management of CVD in PWH. This includes the investigation of biomarkers potentially linked to early diagnosis and prognosis, alongside innovative therapies aimed at addressing sustained immune activation and inflammation.

8. Conclusions

HIV infection is intricately linked to an increased risk of CVD, stemming from a combination of chronic inflammation, immune activation, traditional risk factors, and ART-related metabolic changes. The pathophysiology of HIV-associated CVD is multifaceted. The prevention strategies, including optimizing ART regimens to minimize cardiovascular side effects, are critical in reducing the CVD burden in PWH. Current clinical guidelines emphasize early screening for CVD by using biomarkers and aggressive management tailored to the unique needs of PWH. However, further research is required to refine prevention strategies. Future directions should focus on personalized cardiovascular risk management in PWH, incorporating genetic, environmental, and ART-related factors, along with exploring novel therapies targeting inflammation and immune activation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F.H., F.E.A., H.A., S.F.A., S.Q.B., M.A.A., Z.A., A.M.A. (Asma Malwi Alshahrani), E.M.S., A.M.A. (Ali M. Atoom), A.A.A., A.K.A., Y.N.R. and R.S.; literature search, data analysis, curation and visualization, H.F.H., F.E.A., H.A., S.F.A., S.Q.B., M.A.A., Z.A., A.M.A. (Asma Malwi Alshahrani), E.M.S., A.M.A. (Ali M. Atoom), A.A.A., A.K.A., Y.N.R. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation H.F.H., F.E.A., H.A., S.F.A., S.Q.B., M.A.A., Z.A., A.M.A. (Asma Malwi Alshahrani), E.M.S., A.M.A. (Ali M. Atoom), A.A.A., A.K.A., Y.N.R. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, H.F.H., F.E.A., H.A., S.F.A., S.Q.B., M.A.A., Z.A., A.M.A. (Asma Malwi Alshahrani), E.M.S., A.M.A. (Ali M. Atoom), A.A.A., A.K.A., Y.N.R. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS Statistics—Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Gottlieb, M.S. Discovering AIDS. Epidemiology 1998, 9, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farouk, M.; Hetta, H.F.; Abdelghani, M.; Ezzat, R.; Moustafa, E.F.; Hassany, S.; Aboshaera, K.; Abdelwahid, L.; Alboraie, M.; Bazeed, S.; et al. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) Study of Egyptian physicians towards HIV infection: A multicentre study. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2024, 18, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capriotti, T. HIV/AIDS: An Update for Home Healthcare Clinicians. Home Healthc. Now 2018, 36, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erqou, S.; Lodebo, B.T.; Masri, A.; Altibi, A.M.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Dzudie, A.; Ataklte, F.; Choudhary, G.; Bloomfield, G.S.; Wu, W.C.; et al. Cardiac Dysfunction Among People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kari, E.; Go, J.L.; Loggins, J.; Emmanuel, N.; Fisher, L.M. Abnormal Cochleovestibular Anatomy and Hearing Outcomes: Pediatric Patients with a Questionable Cochleovestibular Nerve Status May Benefit from Cochlear Implantation and/or Hearing Aids. Audiol. Neurotol. 2018, 23, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiberg, M.S.; Chang, C.H.; Skanderson, M.; Patterson, O.V.; DuVall, S.L.; Brandt, C.A.; So-Armah, K.A.; Vasan, R.S.; Oursler, K.A.; Gottdiener, J.; et al. Association Between HIV Infection and the Risk of Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction and Preserved Ejection Fraction in the Antiretroviral Therapy Era: Results From the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiberg, M.S.; Chang, C.C.; Kuller, L.H.; Skanderson, M.; Lowy, E.; Kraemer, K.L.; Butt, A.A.; Bidwell Goetz, M.; Leaf, D.; Oursler, K.A.; et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, M.J.; Leyden, W.A.; Xu, L.; Horberg, M.A.; Chao, C.R.; Towner, W.J.; Hurley, L.B.; Quesenberry, C.P., Jr.; Klein, D.B. Immunodeficiency and risk of myocardial infarction among HIV-positive individuals with access to care. J. Acquir. Immune Deficency Syndr. 2014, 65, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearns, A.; Gordon, J.; Burdo, T.H.; Qin, X. HIV-1-Associated Atherosclerosis: Unraveling the Missing Link. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 3084–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remick, J.; Georgiopoulou, V.; Marti, C.; Ofotokun, I.; Kalogeropoulos, A.; Lewis, W.; Butler, J. Heart failure in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and future research. Circulation 2014, 129, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, R.M.; Neilan, A.M.; Tariq, N.; Awadalla, M.; Afshar, M.; Banerji, D.; Rokicki, A.; Mulligan, C.; Triant, V.A.; Zanni, M.V.; et al. Protease Inhibitors and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with HIV and Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, M.; Sheehy, O.; Baril, J.-G.; Lelorier, J.; Tremblay, C.L. Association Between HIV Infection, Antiretroviral Therapy, and Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Cohort and Nested Case–Control Study Using Québec’s Public Health Insurance Database. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2011, 57, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsue, P.Y.; Waters, D.D. HIV infection and coronary heart disease: Mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afolabi, J.M.; Kirabo, A. HIV and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 1512–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, M.; Brinkman, K.; Geerlings, S.; Smit, C.; Thyagarajan, K.; Sighem, A.; de Wolf, F.; Hallett, T.B. Future challenges for clinical care of an ageing population infected with HIV: A modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyawo, O.; Brockman, G.; Goldsmith, C.H.; Hull, M.W.; Lear, S.A.; Bennett, M.; Guillemi, S.; Franco-Villalobos, C.; Adam, A.; Mills, E.J. Risk of myocardial infarction among people living with HIV: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abelman, R.A.; Mugo, B.M.; Zanni, M.V. Conceptualizing the Risks of Coronary Heart Disease and Heart Failure Among People Aging with HIV: Sex-Specific Considerations. Curr. Treat Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paisible, A.L.; Chang, C.C.; So-Armah, K.A.; Butt, A.A.; Leaf, D.A.; Budoff, M.; Rimland, D.; Bedimo, R.; Goetz, M.B.; Rodriguez-Barradas, M.C.; et al. HIV infection, cardiovascular disease risk factor profile, and risk for acute myocardial infarction. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015, 68, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.; Chang, J.L.; O’Carroll, C.B.; Musubire, A.; Chow, F.C.; Wilson, A.L.; Siedner, M.J. Stroke in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-infected Individuals in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): A Systematic Review. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2018, 27, 1828–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, S.; Chun, T.W.; Fauci, A.S. Pathogenic mechanisms of HIV disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011, 6, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, P.M.; Hahn, B.H. Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2011, 1, a006841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Clish, C.B.; Hua, S.; Scott, J.M.; Hanna, D.B.; Burk, R.D.; Haberlen, S.A.; Shah, S.J.; Margolick, J.B.; Sears, C.L. Gut microbial-related choline metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide is associated with progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis in HIV infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 1474–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missailidis, C.; Neogi, U.; Stenvinkel, P.; Trøseid, M.; Nowak, P.; Bergman, P. The microbial metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide in association with inflammation and microbial dysregulation in three HIV cohorts at various disease stages. AIDS 2018, 32, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haissman, J.M.; Haugaard, A.K.; Ostrowski, S.R.; Berge, R.K.; Hov, J.R.; Trøseid, M.; Nielsen, S.D. Microbiota-dependent metabolite and cardiovascular disease marker trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) is associated with monocyte activation but not platelet function in untreated HIV infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Al-Khatib, A.O.; Sabra, T.; Al-Baidhani, S.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Aleigailly, M.A.; Sallam, M. Challenges in Elucidating HIV-1 Genetic Diversity in the Middle East and North Africa: A Review Based on a Systematic Search. Viruses 2025, 17, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, S.G.; Overbaugh, J.; Phillips, A.; Buchbinder, S. HIV infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, C.; Bremer, A.; Alba, D.; Apovian, C.; Koethe, J.R.; Koliwad, S.; Lewis, D.; Lo, J.; McComsey, G.A.; Eckard, A.; et al. Obesity and Fat Metabolism in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Individuals: Immunopathogenic Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.T.; Glesby, M.J. Management of the metabolic effects of HIV and HIV drugs. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2011, 8, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandson, K.M.; Lake, J.E. Fat Matters: Understanding the Role of Adipose Tissue in Health in HIV Infection. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016, 13, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damouche, A.; Lazure, T.; Avettand-Fènoël, V.; Huot, N.; Dejucq-Rainsford, N.; Satie, A.P.; Mélard, A.; David, L.; Gommet, C.; Ghosn, J.; et al. Adipose Tissue Is a Neglected Viral Reservoir and an Inflammatory Site during Chronic HIV and SIV Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeois, C.; Gorwood, J.; Olivo, A.; Le Pelletier, L.; Capeau, J.; Lambotte, O.; Béréziat, V.; Lagathu, C. Contribution of Adipose Tissue to the Chronic Immune Activation and Inflammation Associated with HIV Infection and Its Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 670566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Delfín, J.; Domingo, P.; Wabitsch, M.; Giralt, M.; Villarroya, F. HIV-1 Tat protein impairs adipogenesis and induces the expression and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in human SGBS adipocytes. Antivir. Ther. 2012, 17, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, S.; Yan, J.S.; Lau, A.; Chan, A.S. HIV replication enhances production of free fatty acids, low density lipoproteins and many key proteins involved in lipid metabolism: A proteomics study. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sadr, W.M.; Mullin, C.M.; Carr, A.; Gibert, C.; Rappoport, C.; Visnegarwala, F.; Grunfeld, C.; Raghavan, S.S. Effects of HIV disease on lipid, glucose and insulin levels: Results from a large antiretroviral-naive cohort. HIV Med. 2005, 6, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, F.; Naito, T.; Oike, M.; Imai, R.; Saita, M.; Inui, A.; Mitsuhashi, K.; Isonuma, H.; Shimbo, T. Correlation between HIV disease and lipid metabolism in antiretroviral-naïve HIV-infected patients in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 2012, 18, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsue, P.Y.; Deeks, S.G.; Hunt, P.W. Immunologic basis of cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 205, S375–S382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shufelt, C.L.; Pacheco, C.; Tweet, M.S.; Miller, V.M. Sex-Specific Physiology and Cardiovascular Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1065, 433–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo, M.M.; Altfeld, M. Sex-based differences in HIV type 1 pathogenesis. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, S86–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, A.; Rimmelin, D.E.; Fitch, K.V.; Zanni, M.V. Sex Differences in Select Non-communicable HIV-Associated Comorbidities: Exploring the Role of Systemic Immune Activation/Inflammation. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2017, 14, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, J.E. The Fat of the Matter: Obesity and Visceral Adiposity in Treated HIV Infection. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2017, 14, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triant, V.A.; Lee, H.; Hadigan, C.; Grinspoon, S.K. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 2506–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S.; Mary-Krause, M.; Cotte, L.; Gilquin, J.; Partisani, M.; Simon, A.; Boccara, F.; Bingham, A.; Costagliola, D. Increased risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients in France, relative to the general population. Aids 2010, 24, 1228–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane, H.M.; Paramsothy, P.; Drozd, D.R.; Nance, R.M.; Delaney, J.A.; Heckbert, S.R.; Budoff, M.J.; Burkholder, G.A.; Willig, J.H.; Mugavero, M.J.; et al. Types of Myocardial Infarction Among Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Individuals in the United States. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggin, H.K.; Liu, Y.; Lyass, A.; van Kimmenade, R.R.; Motiwala, S.R.; Kelly, N.P.; Mallick, A.; Gandhi, P.U.; Ibrahim, N.E.; Simon, M.L.; et al. Incident Type 2 Myocardial Infarction in a Cohort of Patients Undergoing Coronary or Peripheral Arterial Angiography. Circulation 2017, 135, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenchley, J.M.; Price, D.A.; Douek, D.C. HIV disease: Fallout from a mucosal catastrophe? Nat. Immunol. 2006, 7, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelesidis, T.; Kendall, M.A.; Yang, O.O.; Hodis, H.N.; Currier, J.S. Biomarkers of microbial translocation and macrophage activation: Association with progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in HIV-1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 206, 1558–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, D.B.; Lin, J.; Post, W.S.; Hodis, H.N.; Xue, X.; Anastos, K.; Cohen, M.H.; Gange, S.J.; Haberlen, S.A.; Heath, S.L. Association of macrophage inflammation biomarkers with progression of subclinical carotid artery atherosclerosis in HIV-infected women and men. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 1352–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomas, C.; Younas, M.; Reynes, C.; Cezar, R.; Portalès, P.; Tuaillon, E.; Guigues, A.; Merle, C.; Atoui, N.; Fernandez, C.; et al. One of the immune activation profiles observed in HIV-1-infected adults with suppressed viremia is linked to metabolic syndrome: The ACTIVIH study. EBioMedicine 2016, 8, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, G.; Tincati, C.; Silvestri, G. Microbial translocation in the pathogenesis of HIV infection and AIDS. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandler, N.G.; Douek, D.C. Microbial translocation in HIV infection: Causes, consequences and treatment opportunities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundura, L.; Cezar, R.; Gimenez, S.; Pastore, M.; Reynes, C.; Sotto, A.; Reynes, J.; Allavena, C.; Meyer, L.; Makinson, A.; et al. Immune profiles of pre-frail people living with HIV-1: A prospective longitudinal study. Immun. Ageing 2024, 21, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, M.; Psomas, C.; Reynes, C.; Cezar, R.; Kundura, L.; Portales, P.; Merle, C.; Atoui, N.; Fernandez, C.; Le Moing, V.; et al. Microbial Translocation Is Linked to a Specific Immune Activation Profile in HIV-1-Infected Adults with Suppressed Viremia. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funderburg, N.T.; Mayne, E.; Sieg, S.F.; Asaad, R.; Jiang, W.; Kalinowska, M.; Luciano, A.A.; Stevens, W.; Rodriguez, B.; Brenchley, J.M.; et al. Increased tissue factor expression on circulating monocytes in chronic HIV infection: Relationship to in vivo coagulation and immune activation. Blood 2010, 115, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estes, J.D.; Harris, L.D.; Klatt, N.R.; Tabb, B.; Pittaluga, S.; Paiardini, M.; Barclay, G.R.; Smedley, J.; Pung, R.; Oliveira, K.M.; et al. Damaged intestinal epithelial integrity linked to microbial translocation in pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infections. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoff, E.N.; Jackson, S.; Wahl, S.M.; Thomas, K.; Peterman, J.H.; Smith, P.D. Intestinal mucosal immunoglobulins during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1994, 170, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grand, M.; Bia, D.; Diaz, A. Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Real-Life Data. Curr. HIV Res. 2020, 18, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touloumi, G.; Kalpourtzi, N.; Papastamopoulos, V.; Paparizos, V.; Adamis, G.; Antoniadou, A.; Chini, M.; Karakosta, A.; Makrilakis, K.; Gavana, M.; et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in HIV infected individuals: Comparison with general adult control population in Greece. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delabays, B.; Cavassini, M.; Damas, J.; Beuret, H.; Calmy, A.; Hasse, B.; Bucher, H.C.; Frischknecht, M.; Müller, O.; Méan, M.; et al. Cardiovascular risk assessment in people living with HIV compared to the general population. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkholder, G.A.; Tamhane, A.R.; Safford, M.M.; Muntner, P.M.; Willig, A.L.; Willig, J.H.; Raper, J.L.; Saag, M.S.; Mugavero, M.J. Racial disparities in the prevalence and control of hypertension among a cohort of HIV-infected patients in the southeastern United States. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baekken, M.; Os, I.; Sandvik, L.; Oektedalen, O. Hypertension in an urban HIV-positive population compared with the general population: Influence of combination antiretroviral therapy. J. Hypertens. 2008, 26, 2126–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduka, C.U.; Stranges, S.; Sarki, A.M.; Kimani, P.K.; Uthman, O.A. Evidence of increased blood pressure and hypertension risk among people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2016, 30, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, T.L.; Grinspoon, S.K. Body composition and metabolic changes in HIV-infected patients. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 205, S383–S390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, D.D.; Hsue, P.Y. Lipid Abnormalities in Persons Living with HIV Infection. Can. J. Cardiol. 2019, 35, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, J.E.; Wohl, D.; Scherzer, R.; Grunfeld, C.; Tien, P.C.; Sidney, S.; Currier, J.S. Regional fat deposition and cardiovascular risk in HIV infection: The FRAM study. AIDS Care 2011, 23, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L.D.; Mathiesen, E.R.; Kronborg, G.; Pedersen, C.; Gerstoft, J.; Obel, N. Risk of diabetes mellitus in persons with and without HIV: A Danish nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wit, S.; Sabin, C.A.; Weber, R.; Worm, S.W.; Reiss, P.; Cazanave, C.; El-Sadr, W.; Monforte, A.; Fontas, E.; Law, M.G.; et al. Incidence and risk factors for new-onset diabetes in HIV-infected patients: The Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposeiras-Roubín, S.; Abu-Assi, E.; Iñiguez-Romo, A. Tobacco, illicit drugs use and risk of cardiovascular disease in patients living with HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2017, 12, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, G.G.; Protopapas, K.; Bernardino, J.I.; Imaz, A.; Curran, A.; Stingone, C.; Shivasankar, S.; Edwards, S.; Herbert, S.; Thomas, K.; et al. Chems4EU: Chemsex use and its impacts across four European countries in HIV-positive men who have sex with men attending HIV services. HIV Med. 2021, 22, 944–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.; Shahmanesh, M.; Gafos, M. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 63, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Li, S.; Ding, Y.; Shi, S. Association of IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-α polymorphisms with acute coronary syndrome risk: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis. BMC Med. Genom. 2025, 18, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, B.T.; Hu, X.; Singh, K.; Haine, L.; Rupert, A.W.; Neaton, J.D.; Lundgren, J.D.; Imamichi, T.; Chang, W.; Lane, H.C. Genome-wide association study of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, D-dimer, and interleukin-6 levels in multiethnic HIV+ cohorts. AIDS 2021, 35, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Flores, C.A.; Pinales-Rangel, J.G.; Santuario-Facio, S.K.; Urraza-Robledo, A.I.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, M.E.; Miranda-Pérez, A.A.; López-Márquez, F.C. Role of Proinflammatory Cytokines and Genetic Factors Related to Metabolic Alterations in People Living with HIV/AIDS. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2024, 44, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, X.; Li, G.; He, Q.; Dai, H.; Ai, C.; Shi, J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to ischemic heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2017, 96, e6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So-Armah, K.; Freiberg, M.S. HIV and Cardiovascular Disease: Update on Clinical Events, Special Populations, and Novel Biomarkers. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018, 15, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, A.G.; Venter, W.D.F. Cardiovascular toxicity of contemporary antiretroviral therapy. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2021, 16, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemulapalli, A.C.; Elias, A.A.; Yerramsetti, M.D.; Olanisa, O.O.; Jain, P.; Khan, Q.S.; Butt, S.R. The Impact of Contemporary Antiretroviral Drugs on Atherosclerosis and Its Complications in People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e47730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatleberg, C.I.; Ryom, L.; Sabin, C. Cardiovascular risks associated with protease inhibitors for the treatment of HIV. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2021, 20, 1351–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Boer, M.A.; Berbée, J.F.; Reiss, P.; van der Valk, M.; Voshol, P.J.; Kuipers, F.; Havekes, L.M.; Rensen, P.C.; Romijn, J.A. Ritonavir impairs lipoprotein lipase–mediated lipolysis and decreases uptake of fatty acids in adipose tissue. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sadr, W.M.; Lundgren, J.; Neaton, J.D.; Gordin, F.; Abrams, D.; Arduino, R.C.; Babiker, A.; Burman, W.; Clumeck, N.; Cohen, C.J.; et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2283–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.V.; Sharma, S.; Achhra, A.C.; Bernardino, J.I.; Bogner, J.R.; Duprez, D.; Emery, S.; Gazzard, B.; Gordin, J.; Grandits, G.; et al. Changes in Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors with Immediate Versus Deferred Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation Among HIV-Positive Participants in the START (Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment) Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charakida, M.; Donald, A.E.; Green, H.; Storry, C.; Clapson, M.; Caslake, M.; Dunn, D.T.; Halcox, J.P.; Gibb, D.M.; Klein, N.J.; et al. Early Structural and Functional Changes of the Vasculature in HIV-Infected Children. Circulation 2005, 112, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, J.M.; Pernerstorfer-Schoen, H.; Weiss, A.; Schindler, K.; Rieger, A.; Jilma, B. Age and sex modulate metabolic and cardiovascular risk markers of patients after 1 year of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Atherosclerosis 2006, 187, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavinger, C.; Bendavid, E.; Niehaus, K.; Olshen, R.A.; Olkin, I.; Sundaram, V.; Wein, N.; Holodniy, M.; Hou, N.; Owens, D.K.; et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease from antiretroviral therapy for HIV: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Huang, D.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, F.; Luo, J. Direct Oral Anticoagulants vs. Vitamin K Antagonists in Atrial Fibrillation Patients at Risk of Falling: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 833329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimala, C.A.; Atashili, J.; Mbuagbaw, J.C.; Wilfred, A.; Monekosso, G.L. Prevalence of Hypertension in HIV/AIDS Patients on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) Compared with HAART-Naïve Patients at the Limbe Regional Hospital, Cameroon. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Lang, S.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, B.; Chopyk, J.; Schwanemann, L.K.; Ventura-Cots, M.; Bataller, R.; Bosques-Padilla, F. Intestinal virome in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2020, 72, 2182–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effros, R.B.; Fletcher, C.V.; Gebo, K.; Halter, J.B.; Hazzard, W.R.; Horne, F.M.; Huebner, R.E.; Janoff, E.N.; Justice, A.C.; Kuritzkes, D.; et al. Aging and infectious diseases: Workshop on HIV infection and aging: What is known and future research directions. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shim, E.; Crespo-Mejias, Y.; Nguyen, P.; Gibbons, A.; Liu, D.; Shide, E.; Poirier, M.C. Cardiomyocytes are Protected from Antiretroviral Nucleoside Analog-Induced Mitochondrial Toxicity by Overexpression of PGC-1α. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2015, 15, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, J.J.; Hosseini, S.H.; Cucoranu, I.; Hoying-Brandt, A.; Green, E.; Johnson, D.; Wittich, B.; Srivastava, J.; Ivey, K.; Fields, E.; et al. Murine cardiac mtDNA: Effects of transgenic manipulation of nucleoside phosphorylation. Lab. Invest. 2009, 89, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Nguyen, P.; Baris, T.Z.; Poirier, M.C. Molecular analysis of mitochondrial compromise in rodent cardiomyocytes exposed long term to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs). Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2012, 12, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J.Y.; Gordon, J.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.Q.; Tilley, D.G.; Gao, E.; Koch, W.J.; Rabinowitz, J.; Klotman, P.E.; et al. Cardiac Dysfunction in HIV-1 Transgenic Mouse: Role of Stress and BAG3. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2015, 8, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnoud, M.A.H.; Chen, W.; Liu, N.; Zhu, W.; Qiao, J.; Chang, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Q.; et al. Correction to: Sirt7-p21 Signaling Pathway Mediates Glucocorticoid-Induced Inhibition of Mouse Neural Stem Cell Proliferation. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 1391–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, M.J. HIV and Cardiovascular Disease: From Insights to Interventions. Top. Antivir. Med. 2021, 29, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crocker, T.F.; Brown, L.; Lam, N.; Wray, F.; Knapp, P.; Forster, A. Information provision for stroke survivors and their carers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 11, CD001919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.; Joyce, V.; Bendavid, E.; Olshen, R.A.; Hlatky, M.; Chow, A.; Holodniy, M.; Barnett, P.; Owens, D.K. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with current exposure to HIV antiretroviral therapies in a US veteran population. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacey, A.; Savinelli, S.; Barco, E.A.; Macken, A.; Cotter, A.G.; Sheehan, G.; Lambert, J.S.; Muldoon, E.; Feeney, E.; Mallon, P.W.; et al. Investigating the effect of antiretroviral switch to tenofovir alafenamide on lipid profiles in people living with HIV. Aids 2020, 34, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryom, L.; Lundgren, J.D.; El-Sadr, W.; Reiss, P.; Kirk, O.; Law, M.; Phillips, A.; Weber, R.; Fontas, E.; d’Arminio Monforte, A.; et al. Cardiovascular disease and use of contemporary protease inhibitors: The D:A:D international prospective multicohort study. Lancet HIV 2018, 5, e291–e300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, J.; Lu, M.T.; Ihenachor, E.J.; Wei, J.; Looby, S.E.; Fitch, K.V.; Oh, J.; Zimmerman, C.O.; Hwang, J.; Abbara, S.; et al. Effects of statin therapy on coronary artery plaque volume and high-risk plaque morphology in HIV-infected patients with subclinical atherosclerosis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet HIV 2015, 2, e52–e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinspoon, S.K.; Fitch, K.V.; Zanni, M.V.; Fichtenbaum, C.J.; Umbleja, T.; Aberg, J.A.; Overton, E.T.; Malvestutto, C.D.; Bloomfield, G.S.; Currier, J.S.; et al. Pitavastatin to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease in HIV Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaratnam, J.; Van Bremen, K.; Behrens, G.; Boccara, F.; Cinque, P.; Gisslén, M.; Guaraldi, G.; Konopnicki, D.; Kowalska, J.; Mallon, P. European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) Interim Guidance on the Use of Statin Therapy for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in People with HIV. 2024. Available online: https://www.eacsociety.org/media/eacs_interim_guidance_on_statin_use_for_primary_prevention_cvd_in_people_with_hiv_2.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Boccara, F.; Ghislain, M.; Meyer, L.; Goujard, C.; Le May, C.; Vigouroux, C.; Bastard, J.P.; Fellahi, S.; Capeau, J.; Cohen, A.; et al. Impact of protease inhibitors on circulating PCSK9 levels in HIV-infected antiretroviral-naive patients from an ongoing prospective cohort. Aids 2017, 31, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.M.; Chane, T.; Patel, M.; Chen, S.; Xue, W.; Easley, K.A. Warfarin therapy in the HIV medical home model: Low rates of therapeutic anticoagulation despite adherence and differences in dosing based on specific antiretrovirals. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012, 26, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaggya, C.; Nalwanga, D.; Von Braun, A.; Nakijoba, R.; Kambugu, A.; Fehr, J.; Lamorde, M.; Castelnuovo, B. Challenges in achieving a target international normalized ratio for deep vein thrombosis among HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis: A case series. BMC Hematol. 2016, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatawi, A.D.; Alaqyl, A.B.; Alalawi, R.J.; Alqarni, R.S.; Sufyani, R.A.; Alqarni, G.S.; Alqarni, R.S.; Albalawi, J.H.; Alsharif, R.A.; Alatawi, G.I.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Cancer: A Systematic Scoping Review. Diseases 2025, 13, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetta, H.F.; Alatawi, Y.; Alanazi, F.E.; Alattar, A.; Alshaman, R.; Alshareef, H.; Alatawi, Z.; Alatawi, M.S.; Albalawi, J.H.; Alosaimi, G.A. Evaluating the Safety and Efficacy of PD-1 Inhibitors in HIV Patients Diagnosed with Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabourin, A.A.; Patel, T.; Saad, S.; Renner, E.; Mouland, E.; Adie, S.; Ha, N.B. Management of anticoagulation in patients with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency virus. Thromb. Res. 2021, 200, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinarello, C.A. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood 2011, 117, 3720–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.R.; Abbasi, Z.; Fatima, M.; Ochani, R.K.; Shahnawaz, W.; Asim Khan, M.; Shah, S.A. Canakinumab and cardiovascular outcomes: Results of the CANTOS trial. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2018, 8, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, M.J.; Hsue, P.Y.; Benjamin, L.A.; Bloomfield, G.S.; Currier, J.S.; Freiberg, M.S.; Grinspoon, S.K.; Levin, J.; Longenecker, C.T.; Post, W.S. Characteristics, Prevention, and Management of Cardiovascular Disease in People Living With HIV: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 140, e98–e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsue, P.Y.; Ribaudo, H.J.; Deeks, S.G.; Bell, T.; Ridker, P.M.; Fichtenbaum, C.; Daar, E.S.; Havlir, D.; Yeh, E.; Tawakol, A.; et al. Safety and Impact of Low-dose Methotrexate on Endothelial Function and Inflammation in Individuals with Treated Human Immunodeficiency Virus: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study A5314. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 68, 1877–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.L.; Clagett, B.M.; Moisi, D.; Yeh, E.; Morris, C.D.; Ryu, A.; Rodriguez, B.; Stein, J.H.; Deeks, S.G.; Currier, J.S.; et al. Methotrexate Inhibits T Cell Proliferation but Not Inflammatory Cytokine Expression to Modulate Immunity in People Living With HIV. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 924718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goff, D.C., Jr.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Bennett, G.; Coady, S.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Gibbons, R.; Greenland, P.; Lackland, D.T.; Levy, D.; O’Donnell, C.J.; et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014, 129, S49–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; de Ferranti, S.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 3168–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EACS. EACS Guidelines, 11th ed.; European AIDS Clinical Society: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnapalan, M.; Lindsey, B.B.; Greig, J. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: A clinical update. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2024, 74, 428–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV Infection. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. Afr. J. Med. Pract. 1998, 5, 79–104.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.