Abstract

Hypericum kouytchense Lévl is a semi-evergreen plant of the Hypericaceae family. Its roots and seeds have been used in a number of traditional remedies for antipyretic, detoxification, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and antiviral functions. However, to date, no bioactivity compounds have been characterized from the insect gall of H. kouytchens. In this study, we evaluated the antiviral activities of different extracts from the insect gall of H. kouytchen against cathepsin L, HIV-1 and renin proteases and identified the active ingredients using UPLC–HRMS. Four different polar extracts (HW, H30, H60 and H85) of the H. kouytchense insect gall exhibited antiviral activities with IC50 values of 10.0, 4.0, 3.2 and 17.0 µg/mL against HIV-1 protease; 210.0, 34.0, 24.0 and 30.0 µg/mL against cathepsin L protease; and 180.0, 65.0, 44.0 and 39.0 µg/mL against human renin, respectively. Ten compounds were identified and quantified in the H. kouytchense insect gall extracts. Epicatechin, eriodictyol and naringenin chalcone were major ingredients in the extracts with contents ranging from 3.9 to 479.2 µg/mg. For HIV-1 protease, seven compounds showed more than 65% inhibition at a concentration of 1000.0 µg/mL, especially for hypericin and naringenin chalcone with IC50 values of 1.8 and 33.0 µg/mL, respectively. However, only hypericin was active against cathepsin L protease with an IC50 value of 17100.0 µg/mL, and its contents were from 0.99 to 11.65 µg/mg. Furthermore, we attempted to pinpoint the interactions between the active compounds and the proteases using molecular docking analysis. Our current results imply that the extracts and active ingredients could be further formulated and/or developed for potential prevention and treatment of HIV or SARS-CoV-2 infections.

1. Introduction

Viral infection is when a virus invades the body and replicates inside host cells, then produces toxins and causes disease [1]. Antiviral drugs target different stages of viral invasion, including recognition, fusion, entry and genome proliferation [2,3,4]. Cathepsin L protease (Cat L PR) plays an important role in the viral entry of SARS-CoV-2 by activating the spike protein in endosome or lysosome, and has been regarded as a key antiviral drug design target for SARS-CoV-2.

It has been shown that SARS-CoV-2 replication resembles HIV assembly and similar functional proteins are employed [5,6]. Thus, HIV protease inhibitors could be effective against SARS-CoV-2. In the latest guidelines, lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r), a protease inhibitor approved for the treatment of HIV, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, is repurposed for the treatment of COVID-19 [7,8]. Furthermore, other HIV protease (HIV-PR) inhibitors, such as Nelfinavir, Atazanavir and Darunavir, exhibited potent inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication [3,4,9,10,11,12]. Although vaccination has been undertaken globally, the world is still facing a big challenge in reduced efficacy of the vaccines towards SARS-CoV-2 variant strains. Continued research and development of antiviral agents, for either prophylactic or treatment purposes, is critical to human health even when COVID-19 is transitioning from pandemic to endemic.

Hypericum kouytchense Lévl, “Da Guo Lu Huang” in Chinese, is an herbal plant used in traditional Chinese medicine. Its seeds and roots possess antipyretic, detoxification, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and antiviral functions and are suggested for the treatment of tumors, jaundice, dysentery, amenorrhea and irregular menstruation in the “List of Chinese Herbal Medicine in Guizhou”. Furthermore, water or ethanol extract of H. kouytchense is widely utilized by local people in preparing a decoction or medicinal bath for the treatment of hepatitis, sore throat, epithysitis and injuries [13]. Pilepić and Maleš analyzed the polyphenol content in 18 Hypericum species and found that H. kouytchense has the highest content of 16.88% [14]. Several lines of evidence showed that Hypericum species possess antiviral functions. The bioactive secondary metabolites in these species, such as xanthones, ketides and dibenzo-1,4-dioxane derivatives, exhibited antiviral activities against herpes simplex viruses [15]. Acylphloroglucinols from H. sampsonii showed potent inhibition against HIV with EC50 of 0.97~2.97 μM and selectivity index of 4.80~7.70 [16]. Biyouyanagin A, a prenylated acylphloroglucinol from H. chinense, selectively suppressed HIV replication in H9 lymphocytes with a therapeutic index (TI) value higher than 31.3 [17]. Naphthodianthrones, including hypericin and pseudohypericin, also possess antiviral activity against various enveloped viruses [18]. It is noteworthy that the antiviral activity of hypericin is enhanced upon exposure to light, and this activity employs multiple functional modes including inhibition of viral budding [18,19]. Since the insect gall of H. kouytchense exhibits a better profile for the anti-inflammatory, antiviral and anticancer functions than the seeds and roots, we undertook the current study to evaluate the inhibitory activities of four polar extracts and ten compounds from the insect gall of H. kouytchense Lévl. Seven compounds showed strong inhibitory activities against HIV-1 PR. However, only hypericin exhibited strong inhibition of Cat L PR. Hypericin and naringenin chalcone were identified to be the major protease inhibitors in the four extracts. Specifically, hypericin was present in high amounts and showed the most potent inhibitions against both proteases. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on the antiviral function of the H. kouytchense Lévl insect gall, and our results may help in developing novel dual protease inhibitors.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Inhibition of HIV-1 and Cat L PRs by H. kouytchense Insect Gall Extracts

The four extracts of the insect galls of H. kouytchense were evaluated for their inhibitory effects towards HIV-1 PR (aspartic protease) and Cat L PR (cysteine protease). As shown in Table 1, HW, H30, H60 and H85 were potent inhibitions of HIV-1 PR with respective IC50 values of 10.0, 4.0, 3.2 and 17.0 µg/mL. For Cat L PR, H30, H60 and H85 showed potent inhibition with IC50 values of 34.0, 24.0 and 30.0 µg/mL, respectively. However, HW only showed moderate inhibition of Cat L PR with an IC50 value of 210.0 µg/mL. The inhibitory effects of these extracts were much weaker than that of the positive control (cathepsin L inhibitor, IC50: 6.8 × 10−4 µg/mL). The most potent extract, H60, possessed less than 0.003% of the activity of the positive control. This implies that H. kouytchense insect gall extracts might be more selective towards inhibiting HIV-1 proteases over Cat L proteases. To evaluate the physiological toxicity of the extracts, we measured the inhibitory activities of these extracts towards another human aspartic protease, renin. H30, H60 and H85 exhibited potent inhibitions of renin with IC50 values of 65.0, 44.0 and 39.0 µg/mL, respectively. However, HW showed only moderate inhibition of renin with an IC50 value of 180.0 µg/mL. The inhibitory activities of these extracts were lower than that of the positive control (renin inhibitor, IC50: 0.9 µg/mL), with H85 having about 2.3% of the activity of the positive control. Thus, we may conclude that the inhibitory activities of H. kouytchense insect gall extracts for HIV-1 PR are better than those for Cat L PR, and the HW extract was low toxicity.

Table 1.

The IC50 values of H. kouytchense insect gall extracts against HIV-1, Cat L and renin PRs (n = 3).

2.2. Characterization of Selective Compounds in the H. kouytchense Insect Gall Extracts by UPLC–MS and UV–Vis Methods

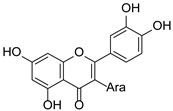

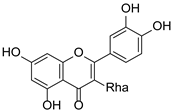

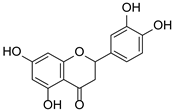

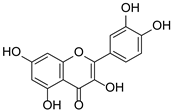

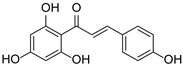

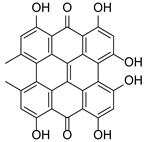

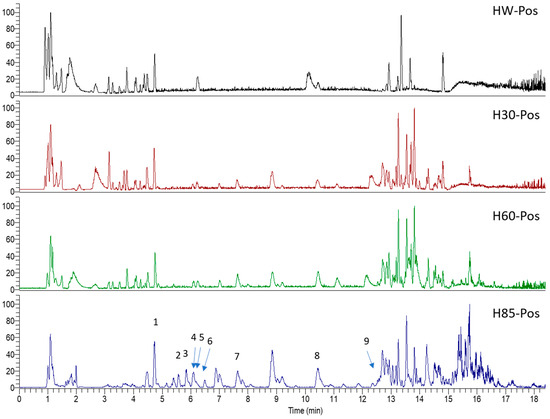

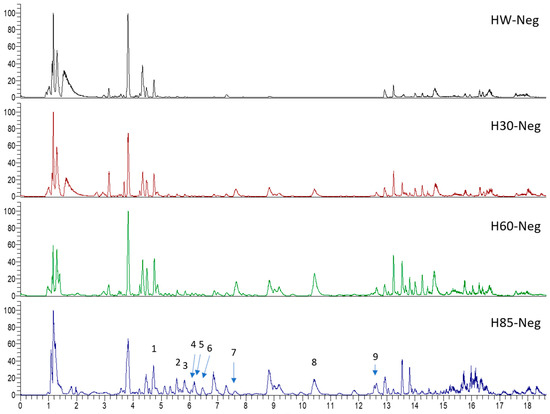

Hypericum species contain a wide range of active ingredients, including prenylated acylphloroglucinols, meroterpenes, ketides, and dibenzo-1,4-dioxane derivatives [20]. Ten selected active compounds were profiled in the four extracts of H. kouytchense insect gall using UPLC–MS (Figure 1 and Figure 2 and Table 2). The 10 compounds were epicatechin, rutin, hyperoside, taxifolin-7-rhamnoside, quercetin-3-O-arabinose, quercitrin, eriodicytiol, quercetin, hypericin and naringenin chalcone. As shown in Table 3, epicatechin and naringenin chalcone were present in much higher quantities than the other compounds in the extracts. In addition, rutin, hyperoxide, taxifolin-7-rhamnoside, quercitrin, eriodicytiol and quercetin were present in concentrations higher than 5 μg/mg in H85, and quercetin, eriodicytiol and hypericin were present in concentrations higher than 9 μg/mg in H60.

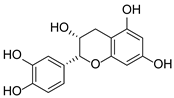

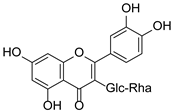

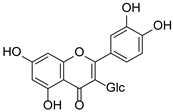

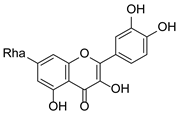

Figure 1.

Ten selected active compounds in H. kouytchense insect gall extracts analyzed by UPLC–MS (positive mode).

Figure 2.

Ten selected active compounds in H. kouytchense insect gall extracts analyzed by UPLC–MS (negative mode).

Table 2.

Properties of the 10 selected active compounds in the H. kouytchense insect gall extracts.

Table 3.

Content of the 10 active compounds in the extracts of H. kouytchense insect galls (µg/mg).

2.3. Inhibition of HIV-1 and Cat L PRs by the Active Compounds from the H. kouytchense Insect Gall Extracts

To identify potential components responsible for the antiviral effects of H. kouytchense insect gall, we measured the inhibitory activities of the 10 active compounds against HIV-1 and Cat L PRs. As shown in Table 4 and Table 5, at a concentration of 1000.0 µg/mL, all compounds except rutin, quercetin and quercetin-3-arabinoside showed good inhibitions of HIV-1 PR, especially hypericin and naringenin chalcone, with IC50 values of 1.8 and 33.0 µg/mL, respectively. Towards Cat L PR, only hypericin, a dimeric anthraquinone, showed moderate inhibitory activity, with an IC50 value of 17,100.0 µg/mL. Thus, hypericin could be used as a lead compound in developing dual protease inhibitors with higher selectivity towards both HIV-1 and Cat L PRs.

Table 4.

Inhibition of Cat L PR by the 10 active compounds in H. kouytchense insect gall extracts (n = 3).

Table 5.

Inhibition of HIV-1 PR by the 10 active compounds in H. kouytchense insect gall extracts (n = 3).

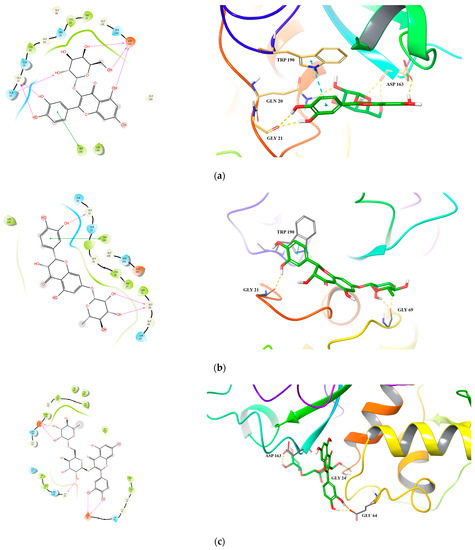

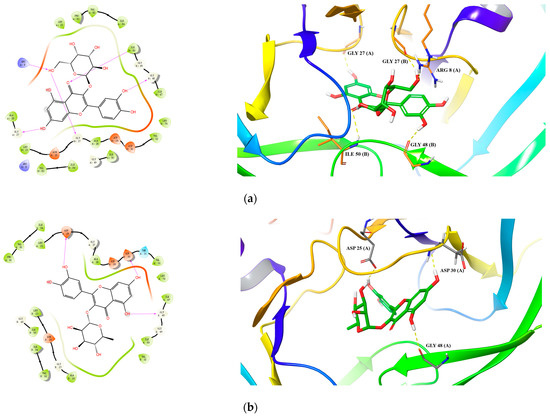

2.4. Molecular Docking

For Cat L PR, we observed good binding affinity for six compounds with docking scores less than −6.0 and glide emodel values less than −50.0 kcal/mol, with hyperoside, taxifolin-7-O-rhamnoside and rutin being the top three (Table 6 and Figure 3). For hyperoside, six hydrogen bonds were formed with the active site residues Gly 21 and Asp 163. In addition, the benzene ring of hyperoside formed a π–π stacking with residue Typ 190 (Figure 3a). For taxifolin-7-O-rhamnoside, three hydrogen bonds were formed with residues Gly 69 and Gly 21 and a π–π stacking with residue Typ 190 (Figure 3b). For rutin, which had the lowest interaction energy of −79.958 kcal/mol, three hydrogen bonds were formed between the rutinoside group and residues Asp 163 and Gly 24 and two hydrogen bonds were formed between the 3’,4´-dihydroxyl of B ring and residue Glu 64 (Figure 3c).

Table 6.

Docking of the 10 active compounds in the H. kouytchense insect gall extracts, along with the positive control cathepsin L inhibitor, against Cat L PR.

Figure 3.

Predicted 2D and 3D binding models of cathepsin L protease with Hyperoside (a), Taxifolin-7-O-rhamnoside (b), Rutin (c) and Hypericin (d) by molecular docking.

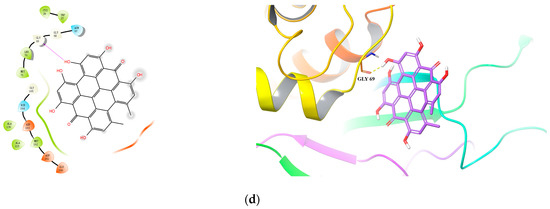

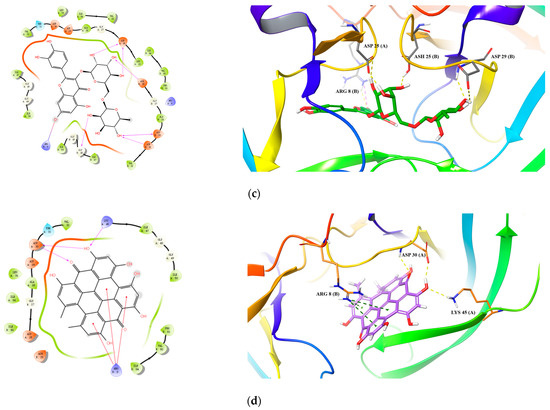

For HIV-1 PR, all 10 active compounds provided reasonably good docking results (Table 7 and Figure 4). For hyperoside, its hydroxyls and carbonyls formed five hydrogen bonds with residues Arg 8(B), Gly 27(B), Gly 48(B) and Ile 50(B) (Figure 4a). For quercitrin, three hydrogen bonds were formed between its hydroxyl groups and residues Asp 25(A), Asp 30(A) and Gly 48(A) (Figure 4b). For rutin, we identified six hydrogen bonds between its hydroxyl groups and residues Asp 25(A), Ash 25(B), Gly 48(B), Asp 29(B) and Asp 30(B) and a salt bridge with Abg 8(B) (Figure 4c).

Table 7.

Docking of the 10 active compounds in the H. kouytchense insect gall extracts, along with positive control pepstatin A, against HIV-1 PR.

Figure 4.

Predicted 2D and 3D binding models of HIV-1 Protease with Hyperoside (a), Quercitrin (b), Rutin (c) and Hypericin (d) through molecular docking.

Specifically, for hypericin (the most potent compound against both HIV-1 and Cat L PRs), one hydrogen bond was formed between one of its hydroxyl groups and residue Gly 69 in Cat L PR (Figure 3d). Its hydroxyl and carbonyl groups formed four hydrogen bonds with residues Asp 30(A) and Lys 45(A) and a π–cation interaction between its benzene ring and residue Arg 8(B) in HIV-1 PR (Figure 4d). However, hypericin is sensitive to UV–Vis light and, thus, the docking results may not necessarily represent its real mechanism of action against HIV-1 and Cat L PRs. Further studies are warranted to identify the active form of hypericin and illustrate how it inhibits HIV-1 and Cat L PRs.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material

Insect gall of H. kouytchense was collected from Guiyang (Guizhou Province, China) in March 2020 and authenticated by Professor Qing Wen Sun, Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (GUTCM). The voucher specimen (no. 202003/GLH) has been deposited at GUTCM.

3.2. Reagents and Instruments

Reference compounds (>98% purity), epicatechin, rutin, hyperoside, taxifolin-7-O-rhamnoside, quercetin-3-O-arabinose, quercitrin, eriodicytiol, quercetin, hypericin and naringenin chalcone, were purchased from Chengdu De Rui Ke Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China). UPLC-QTOF-MS was performed on a Thermo Scientific UltiMate 3000 UHPLC system equipped with a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Focus Orbitrap (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) with reagents CH3CN and HCOOH in LC–MS grade and propan-2-ol and CH3OH in HPLC grade. DMSO (>99.9% purity) for activity assay was purchased from Solarbio Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). The fluorescence was detected using a BioTek Synergy II Microplate Reader (Biotec Co., Minneapolis, MN, USA).

3.3. Sample Preparation

Following our previously reported protocols [21], the air-dried insect gall of H. kouytchense Lévl was powdered and subsequently extracted three times with water or CH3OH–H2O (30:70, 60:40 and 85:15) for 1 h under reflux to obtain the HW, H30, H60 and H85 extracts, respectively. Concentration of the extract was 10 mg/mL for chemical profiling analysis and 100 mg/mL for quantitative data acquisition. All sample solutions were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min before testing.

3.4. Fluorimetric HIV-1, Cat L and Renin PRs Inhibition Assay

The inhibitory activities against HIV-1, Cat L and Renin PRs were assayed by fluorimetric methods using our previously published protocols [21,22].

3.5. Characterization and Content Determination of the Main Active Components in the Extracts

Stock solutions (1.0 mg/mL) of reference compounds, epicatechin, rutin, hyperoside, taxifolin-7-rhamnoside, quercetin-3-O-arabinose, quercitrin, eriodicytiol, quercetin and naringenin chalcone, were prepared in methanol and stored at 4 °C. For each reference compound, an array of standard solutions was prepared from the stock by serial dilution with methanol with final concentrations of 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12, 1.56, 0.78 and 0.39 µg/mL. Stock solution of hypericin (10.0 mg/mL) was prepared in DMSO and stored at −80 °C. A series of solutions used for calibration were prepared in DMSO from the stock with respective final concentrations of 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.05, 0.09, 0.1 and 0.2 mg/mL. Since hypericin is sensitive to light, both stock and calibration solutions were prepared without exposure to light. Chemical profiling of the four extracts (HW, H30, H60 and H85) was obtained with UPLC–Orbitrap–MS using our previously published protocols [21]. A UV–Vis–Microplate assay was applied for determination of hypericin by using a Synergy II microplate reader with detection wavelength of 588 nm. Sample solutions of HW, H30, H60 and H85 were prepared in water, 10% DMSO–water, 10% DMSO–water and 100% DMSO, respectively, with a final concentration of 10 mg/mL. The measurement was carried out in triplicate.

3.6. Docking Studies

The Schrödinger Suite 2021-1 and crystal structures of HIV-1 PR (PDB ID: 1QBS) and Cat L PR (PDB ID: 3OF9) were used in molecular docking analysis following our previously reported protocols [21,23].

4. Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2, the causative pathogen of COVID-19, is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA Betacoronavirus. As of 23 September 2022, it has infected more than 611 million people (confirmed cases) along with nearly 6.51 million deaths globally [24]. The current treatment options for COVID-19 mainly include antiviral drugs and immunotherapy. The genus of Hypericum has broad spectra of secondary metabolites with diverse biological activities. Previously, some bioactive compounds such as emodin, hypericin, hyperoside and/or isoquercitrin, chlorogenic acid, quercetin and quercitrin were observed in the leaves of H. kouytchense [25]. Sixteen chemical components were isolated from acrial parts of H. kouytchense Lévl, including xanthones, pentacyclic terpenoids, anthranone and phenolic acid [26]. However, there is no report on the chemical constituents and antivirus activity of H. kouytchense insect gall. In this study, we evaluated the inhibitory effects of four different extracts (HW, H30, H60, H85) of H. kouytchense insect gall against HIV-1 and Cat L PRs. H60 exhibited the most potent activity against both HIV-1 and Cat L PRs with IC50 values of 3.2 ± 2.97 µg/mL and 24.0 ± 1.44 µg/mL, respectively. Polarity of this fraction is likely to be similar to the most polar fraction of chloroform extracts of H. perforatum, in which active compounds have been identified to inhibit HIV infection [27]. Furthermore, we analyzed the contents of 10 active components in the extracts and measured their respective inhibitory activities against HIV-1 and Cat L PRs. Hypericin, which was highly present (0.1~1.17%) in the extracts, showed the most potent inhibitory activity against both proteases. The content is consistent with that recorded in U.S. Pharmacopeia (0.1~0.3%) or European Pharmacopiea (0.08%). Furthermore, hypericin has been suggested to treat SARS-CoV-2 as it could bind to four different SARS-CoV-2 target sites: spike protein (−9.7 kcal/mol), Mpro (−10.2 kcal/mol), PLpro (−7.8 kcal/mol) and RdRp (−7.6 kcal/mol) [28]. The second most potent compound is naringenin chalcone, which showed a potent inhibition of HIV-1 PR (IC50 = 33.0 ± 4.59 µg/mL). Naringenin chalcone is also the most abundant component in the extracts. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing that naringenin chalcone possesses antiviral function. For the development of more potent antivirus inhibitors from the insect gall of H. kouytchense, further in-depth research will be carried out in our lab.

Author Contributions

B.W.P.: conducted the experimental work, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Y.W.: designed and conducted experimental work and wrote the manuscript. S.M.L. and S.X.X.: conducted the UPLC–MS experiment and analyzed the data. J.W.X., X.Z. and M.C.: conducted experimental work. X.Y.: helped analyze the data. Q.W.S.: identified plant material. J.Y., M.K.S. and Y.Z.: revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Innovation Group Project of Guizhou Province [grant no. Qian Jiao He KY (2021) 018], Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects [grant no. Qian Ke He Zhi Cheng (2020) 4Y213 and ZK (2022) general480], the Research Center of Molecular Bioactivity from Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ethnomedicine [grant no. 3411-4110000520364], the Innovative and Entrepreneurial Project of Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine [grant no. 2019(56)], the Shenzhen Fund for Guangdong Provincial High-Level Clinical Key Specialties [grant no. SZXK059], the Youth Science and Technology Talent Growth Project of Guizhou Province [grant no. Qian Jiao He KY (2022) 253], and the Project of Guizhou Provincial Health Commission [grant no. gzwkj2022-232 and gzwkj2022-467].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article and on request from the author and corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Sample Availability

The samples of plant material, extraction and reference compounds of HK are available from the authors.

Abbreviations

| Cat L PR | cathepsin L protease |

| HIV PR | human immunodeficiency virus protease |

| HW | aqueous extract of H. kouytchense insect gall |

| H30 | 30% methanol extract of H. kouytchense insect gall |

| H60 | 60% methanol extract of H. kouytchense insect gall |

| H85 | 85% methanol extract of H. kouytchense insect gall |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease 2019 |

| HSV | herpes simplex virus |

| LC–MS | liquid chromatograph–mass spectrometer |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| HPLC | high-performance liquid chromatography |

| UPLC–MS | ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| GUTCM | Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine |

References

- Natrual Portfolio: Viral Infection. Available online: https://www.nature.com/subjects/viral-infection (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Guan, W.; Lan, W.; Zhang, J.L. COVID-19: Antiviral agents, antibody development and traditional Chinese medicine. Virol. Sin. 2020, 35, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruijssers, A.J.; Denison, M.R. Nucleoside analogues for the treatment of coronavirus infections. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019, 35, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleemi, M.A.; Ahmad, B.; Benchoula, K.; Vohra, M.S.; Mea, H.J.; Chong, P.P.; Palanisamy, N.K.; Wong, E.H. Emergence and molecular mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV to target host cells and potential therapeutics. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 85, 104583–104596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illanes-Álvarez, F.; Márquez-Ruiz, D.; Márquez-Coello, M.; Cuesta-Sancho, S.; Girón-González, J.A. Similarities and differences between HIV and SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.M.; Cheng, V.C.C.; Hung, I.F.N.; Wong, M.M.L.; Chan, K.H.; Chan, K.S.; Kao, R.Y.T. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: Initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax 2004, 59, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momattin, H.; Al-Ali, A.Y.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A. A systematic review of therapeutic agents for the treatment of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 30, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FintelmanRodrigues, N.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Lima, C.R.; Silva, F.S.; Ferreira, A.C.; Mattos, M.; Freitas, C.S.; Soares, V.C.; Temerozo, J.R.; Miranda, M.D.; et al. Atazanavir Alone or in Combination with Ritonavir, Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Replication and Proinflammatory Cytokine Production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00825-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.J.; Peng, C.; Shi, Y.L.; Zhu, Z.D.; Mu, K.J.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhu, W.L. Nelfinavir was predicted to be a potential inhibitor of 2019-nCov main protease by an integrative approach combining homology modelling, molecular docking and binding free energy calculation. BioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, P.; Tian, S.; Meng, Z.; Yang, L. Insight derived from molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations into the binding interactions between HIV-1 protease inhibitors and SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. ChemRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, R.; Kumari, S.; Pandey, B.; Mistry, H.; Bihani, S.C.; Das, A.; Prashar, V.; Gupta, G.D.; Panicker, L.; Kumar, M. Structural insights into SARS-CoV-2 proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166725–166749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Hao, X.J.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Huang, L.J.; Pei, S.J. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants from the Dragon Boat Festival herbal markets of Qianxinan, southwestern Guizhou, China. Plant Divers. 2020, 42, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilepić, K.H.; Maleš, Z. Quantitative analysis of polyphenols in eighteen Hypericum taxa. Period. Biol. 2013, 115, 459–462. [Google Scholar]

- Anna, G.; Lianna, B.; Chris, P. Review of whole plant extracts with activity against herpes simplex viruses in vitro and in vivo. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med. 2021, 2, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.C.; Chen, C.M.; Yang, J.; Li, X.N.; Liu, J.J.; Sun, B.; Huang, S.X.; Li, D.Y.; Yao, G.M.; Luo, Z.W.; et al. Bioactive acylphloroglucinols with adamantyl skeleton from Hypericum sampsonii. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 6322–6325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, N.; Okasaka, M.; Ishimaru, Y.; Takaishi, Y.; Sato, M.; Okamoto, M.; Oshikawa, T.; Ahmed, S.U.; Consentino, L.M.; Lee, K.H. Biyouyangin A, an anti-HIV agent from Hypericum chinense L. var. salicifolium. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 2997–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, R.; Abdollahi, M. An update on the ability of St. John’s wort to affect the metabolism of other drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2012, 8, 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meruelo, D.; Lavie, G.; Lavie, D. Therapeutic agents with dramatic antiretroviral activity and little toxicity at effective doses: Aromatic polycyclic diones hypericin and pseudohypericin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 5230–5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, N.; Kashiwada, Y. Characteristic metabolites of Hypericum plants: Their chemical structures and biological activities. J. Nat. Med. 2021, 75, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.W.; Li, S.M.; Xiao, J.W.; Yang, X.; Xie, S.X.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.; Wei, Y. Dual inhibition of HIV-1 and Cathepsin L proteases by Sarcandra glabra. Molecules 2022, 27, 5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Ma, C.M.; Hattori, M. Synthesis of dammarane-type triterpene derivatives and their ability to inhibit HIV and HCV proteases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 3003–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; He, X.M.; Wang, X.T.; Yu, B.; Zhao, S.Q.; Jiao, P.L.; Jin, H.W.; Liu, Z.M.; Wang, K.W.; Zhang, L.R.; et al. Design, synthesis and biological activities of piperidinespirooxadiazole derivatives as α7 nicotinic receptor antagonists. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 207, 112774–112790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report: COVID-19 Partners Platform. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Andrea, K.; Souvik, K.; Selahaddin, S.; Michael, S.; Eva, C. Occurrence and Distribution of Phytochemicals in the Leaves of 17 In vitro Cultured Hypericum spp. Adapted to Outdoor Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1616. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.D.; Lin, Q.X.; Yang, X.-Z. Study on chemical components of H. kouytchense Lévl. J. Yunnan Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2022, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Maury, W.; Price, J.P.; Brindley, M.A.; Oh, C.; Neighbors, J.D.; Wiemer, D.F.; Wills, N.; Carpenter, S.; Hauck, C.; Murphy, P.; et al. Identification of light-independent inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus-1infection through bioguided fractionation of Hypericum perforatum. Virol. J. 2009, 6, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazouri, S.E.; Aanniz, T.; Touhtouh, J.; Kandoussi, I.; Hakmi, M.; Belyamani, L.; Ibrahimi, A.; Ouadghiri, M. Anthraquinone: A promising muti-target therapeutic scaffold to treat Covid-19. Int. J. Appl. Biol. Pharm. 2021, 12, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).