Abstract

In contemporary semiconductor manufacturing, wafer-handling robots are essential for achieving high-speed and high-precision wafer transportation. However, the demand for rapid motion and lightweight design introduces flexible transmission components that are prone to residual vibrations, which degrade positioning accuracy and system stability. To address this challenge, this paper proposes a vibration-suppression trajectory planning method based on the Gray Goose Optimization (GGO) algorithm. The proposed algorithm integrates grouped global search with local optimization capabilities, making it well suited for solving multi-objective optimization problems. Comparative tests conducted on eight randomly selected multimodal benchmark functions from the CEC2013 test suite verify the effectiveness and robustness of the GGO algorithm. Establishing a multi-objective function that considers both motion time and vibration energy enables the GGO algorithm to determine the switching time points of an S-shaped velocity profile, thereby generating smooth trajectories with continuous velocity and acceleration. By varying different initial conditions, the trade-off between motion time and vibration energy is systematically analyzed with respect to angular displacement, initial acceleration, and time-weighting factors. Simulation results indicate that the planned trajectories exhibit negligible displacement variation under zero-mean disturbances. The velocity error remains within 0.1 deg·s−1, and the acceleration error is confined within 0.2 deg·s−2. Consequently, Pareto-optimal solutions are successfully obtained with respect to both motion time and residual vibration energy.

1. Introduction

The wafer transport robotic arm is an important actuator in semiconductor manufacturing equipment, and its performance directly affects production throughput and yield. As semiconductor process nodes continue to shrink, stringent requirements are placed on the robotic arm’s positioning accuracy, stability, and operational efficiency [1,2,3]. Traditional time-optimal trajectory planning methods often focus on achieving the fastest point-to-point motion of the robotic arm’s end effector while neglecting the issue of residual vibrations at the end effector caused by the flexible characteristics of the transmission system. Such vibrations can lead to a decrease in the positioning accuracy of the robotic arm’s end effector, and in severe cases, may cause wafer displacement or breakage, resulting in reduced productivity and significant economic losses [4,5]. Therefore, efficient and precise vibration-suppression trajectory planning has become one of the core technologies in the development of advanced wafer robots.

The vibration suppression methods for robotic arms can be categorized into passive and active vibration suppression. Passive vibration suppression primarily involves optimizing the topology to improve mass distribution, using lightweight, stiff materials to enhance the equivalent stiffness, and incorporating damping devices and energy-absorbing components to suppress vibrations through physical mechanisms. These passive vibration suppression schemes do not require external energy input, are cost-effective, but have limited adaptability to time-varying operating conditions, making them difficult to meet the requirements of wafer transport robotic arms [6]. Active vibration suppression, on the other hand, reduces the vibrations of the robot by improving control strategies, thereby enhancing motion precision and stability. PID control, with its simple and intuitive structure and low implementation difficulty, is widely used in the motion control of industrial robots to suppress elastic vibrations in robotic arms. Yang C et al. employed PID fuzzy control to suppress elastic vibrations in flexible robotic arms, improving the positioning and control accuracy of piezoelectric flexible arm ends [7]. Guo et al. proposed a tracking control system integrating an incremental PID controller and a sliding mode robust controller, which demonstrated stronger accuracy, stability, and anti-interference capabilities compared to traditional PID control [8]. In addressing similar robotic arm control problems, Wazzan utilized PID sliding mode control combined with a genetic algorithm to tune controller parameters, effectively improving the performance of the robotic arm’s PID controller [9]. Despite the simplicity and intuitiveness of these control methods, these controllers are often optimized based on specific models, and their control parameters are difficult to meet the requirements for high precision and stability, especially when dealing with complex robotic arm structures or variable working environments.

Recently, researchers have commonly employed vibration suppression trajectory optimization to address the limitations of both passive and active vibration suppression, providing a more cost-effective and universally applicable solution for robotic arm vibration control. This approach has become one of the key research focuses in the field of robotic arm control [10]. These methods formulate trajectory planning as a multi-objective or constrained optimization problem by simultaneously considering system dynamics, motion time, energy consumption, joint smoothness, and end-effector vibration, and they commonly introduce metaheuristic optimization algorithms to search for optimal solutions. These optimization algorithms, inspired by natural phenomena and biological behaviors, offer new approaches for solving trajectory planning and constrained optimization problems of this nature [11]. The development of metaheuristic optimization algorithms can be broadly divided into two directions: global search and local optimization. Among them, the Genetic Algorithm (GA) is widely used in various global search optimization problems due to its strong capability in handling complex constraints, combinatorial optimization, and global exploration. Xu Qiang et al. proposed a genetic algorithm combined with a simulated annealing mechanism, which further improved the optimization accuracy, shortened the robotic arm’s motion time, and enhanced its work efficiency [12]. Meanwhile, Kheshti et al. applied genetic algorithms to adjust the gain optimization of sliding mode controllers, reducing the time required for a manipulator arm to complete a predefined motion trajectory [13]. However, the computational model of genetic algorithms is relatively complex, and its use has certain limitations. In contrast, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) has a simpler algorithm structure and stronger local optimization capability. In this context, Wu N et al. proposed an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm (RTPPSO) to optimize the robotic arm’s joint angles or path. By introducing an adaptive weight strategy, they significantly improved the robotic arm’s work efficiency [14]. However, when solving complex problems with multiple dimensions, strong constraints, and strong coupling, PSO is prone to accuracy degradation and insufficient global search capability due to the influence of random disturbances [15,16,17]. Researchers have proposed various new optimization algorithms and introduced different solution strategies to address the shortcomings of these two algorithms. Yue et al. applied a gray wolf optimization algorithm with a probabilistic disturbance strategy to solve the time-optimal problem. This optimization strategy effectively balanced the weight between local optimization and global search [18]. However, the gray wolf population may converge around suboptimal individuals, leading to premature convergence issues [19,20]. Pu Q et al. introduced an improved wild dog optimization algorithm for robotic arm time-impact optimization [21,22], but they did not perform tests for solving high-dimensional problems using the wild dog optimization algorithm. Additionally, to improve global search capability and address the issue of search direction disturbance, Lv Yun peng et al. proposed an inverse kinematics solver based on a multi-strategy improved dung beetle optimization algorithm. However, this improved algorithm has not been applied to the multi-objective vibration optimization direction [23]. Widyianto Agus et al. addressed the issue of the shipboard two-degree-of-freedom robotic arm being affected by environmental factors and proposed a real-time tuning of PD control parameters based on an ant colony algorithm, significantly improving the stability of shipboard equipment [24]. Abro et al. combined ant colony optimization’s pheromone learning with the Denavit–Hartenberg (DH) method to develop a robotic arm error model, further enhancing the accuracy of global search and improving the reliability and accuracy of industrial robotic systems [25]. However, the ant colony algorithm is heavily dependent on the initial model, making it difficult to avoid local optimal solutions. The Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) introduced a random spiral search step, eliminating the need for crossover and mutation operators, with a simpler program structure. Wang Fang et al. applied a hybrid whale optimization algorithm to optimize the time-impact optimal trajectory of industrial robotic arms, using fifth-order B-splines for interpolation planning of motion trajectories in joint space [26]. However, the performance of this algorithm significantly deteriorates in a multi-constraint environment and requires further integration with various improvement strategies [27]. The Graylag Goose Optimization (GGO) algorithm introduced a group migration strategy [28], demonstrating strong search capabilities in multi-objective problems and efficient local optimization when facing suboptimal solutions. Ashish Sharma et al. conducted eight multi-objective benchmark tests, with the results showing that the Multi-Objective Graylag Goose Optimization (MOGGO) algorithm exhibited excellent performance in terms of convergence [29].

In summary, this paper introduces the GGO algorithm into the vibration suppression trajectory optimization problem of wafer transport robotic arms, providing a new feasible solution for multi-objective trajectory optimization. This study constructs the end dynamics equation of the flexible lower arm and integrates a multi-objective optimization model involving motion time, energy, and impact. Based on the multi-objective GGO algorithm, the trajectory parameters are solved, aiming to generate a set of Pareto-optimal trajectories with superior overall performance, offering a novel and efficient solution to improve the performance of the wafer transport system.

2. Establishment of the Dynamics Model for Wafer Transport Robotic Arm

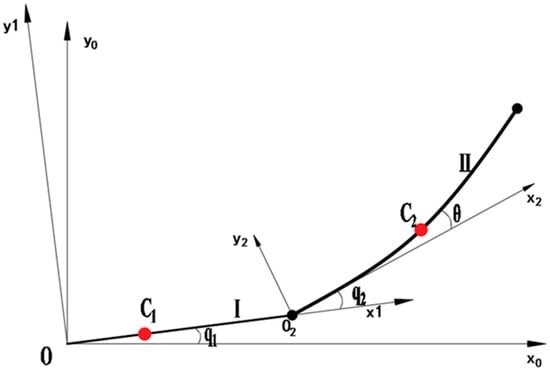

In this study, the wafer transport robotic arm mainly consists of two links [30,31]. The upper (first) link is rigidly connected to the motor, while the lower (second) link is driven by another motor via a flexible steel belt inside the upper link, which can be regarded as a flexible motion joint. During motion, only the bending stress of the steel belt is considered. The end-effector is coupled to the posture of the upper link through the steel belt embedded inside the lower link. As shown in Figure 1, q1 and q2 denote the rotational joint angles defined by the DH parameters, whereas θ represents the elastic deformation angle of the flexible transmission element.

Figure 1.

Motion Model of Wafer Transport Robotic Arm.

Table 1 shows the simplified model of the wafer transport robot, which consists of the rigid link I (upper arm) and the flexible link II (lower arm). The world coordinate system X0OY0 is established with the base as the origin, the coordinate system X1OY1 is set at the end-point of link I (upper arm), and the coordinate system X2O2Y2 is established at the end-point of link II (lower arm). C1 and C2 represent the center of mass of the two links. q1 is the rotation angle of the primary arm, q2 is the rotation angle of the secondary arm, and θ is the deformation of the flexible lower arm. The structural parameters of the wafer transfer robotic arm in this study are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

D-H Parameter Table of the Wafer Handling Robot Arm.

Table 2.

Parameters of Components of the Wafer Transport Robotic Arm.

First, based on the Lagrange method, the dynamic equations of a planar two-degree-of-freedom rigid robot are established. First, the robot’s potential energy equation is analyzed. The robot’s forearm can be regarded as a flexible arm rod, and its elastic potential energy can be expressed as

Here, the θ refers to the ideal angle of the forearm when no deformation occurs. Since the robot prototype moves parallel to the ground throughout, gravitational potential energy is not taken into account. The kinetic energy expression includes both the rotational kinetic energy of each link and the translational kinetic energy of the link centers of mass.

Then the total kinetic energy of the robotic arm is:

I1 and I2 represent the moments of inertia of the link about its center of mass. Since both the upper arm and forearm rotate around their joints, the moments of inertia of the upper arm and forearm are:

The Lagrange function of the robotic arm is:

Based on the Lagrange function, the Lagrange equations are further applied to each generalized coordinate.

The Lagrange dynamic equation of the lower arm is:

The Lagrange dynamic equation of the upper arm is:

The dynamic model of the wafer transfer robot system is:

In Equation (7), the stiffness term k(q2 − θ) represents the restoring torque induced by the elastic deformation of the flexible transmission and is applied to the corresponding joint equation.

3. Vibration Suppression Trajectory Planning for Robotic Arms Based on Graylag Goose Algorithm

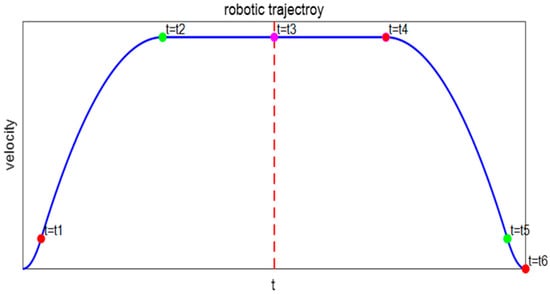

Existing robot trajectory planning methods include cubic and quintic polynomial trajectory planning algorithms [32,33,34], T-shaped and S-shaped acceleration-deceleration trajectory planning algorithms, and B-spline trajectory planning algorithms. During the operation of a wafer handling manipulator, the start and end positions are known, while the motion states during the process are unknown. This study uses a cubic polynomial interpolation method to plan the motion trajectory [35]. This method combines the low impact and high stability of S-shaped trajectory planning with the low computational load of T-curve planning. It is easy to program and debug, has high reliability, and can avoid sudden changes in acceleration, thereby effectively suppressing vibrations at the manipulator’s end. As shown in Figure 2, the polynomial trapezoidal interpolation curve trajectory is defined over the interval (0, t6). The robotic arm first experiences smooth startup acceleration, the acceleration decreases beginning at time t1, and reaches constant velocity at time t2. If t = t4, the speed begins to decelerate until it reaches 0 at t6, achieving a smooth stop. The trajectory expression is given in Equation (8).

Figure 2.

Velocity planning S-shaped curve.

Let the angular displacement of the wafer transport robotic arm be A, then its displacement equation can be expressed in Equation (9).

For the convenience of deriving the formula, we replace part of the polynomial in the displacement formula with P and Q, as shown in Equations (10) and (11).

The rate of change in jerk directly affects the efficiency of these energy losses, especially during the initial impact or rapid change stages. In a vibration system, the integral over time of the square of the jerk reflects the residual vibration energy of the system during rapid start-stop processes. To quantitatively evaluate vibration suppression performance, Equation (12) defines the residual vibration energy as the time integral of the squared jerk. Since jerk represents the rate of change in acceleration, minimizing this index effectively suppresses high-frequency excitation and residual oscillations during rapid start–stop motions.

In this study, the planned velocity profile is designed to be symmetric with respect to the mid-time instant t3. As a result, the jerk-related vibration energy contributed by the second half of the motion [t3, t6] is identical to that of the first half [t0, t3]. Therefore, for conciseness, Equation (12) evaluates the vibration energy over [t0, t3], and the total vibration energy over the complete motion interval [t0, t6] can be obtained.

The multi-objective optimization function is:

Optimization is the process of finding the best solution to a problem among all possible alternatives [36,37,38]. The Graylag Goose Optimization (GGO) algorithm, as an emerging metaheuristic algorithm, is inspired by the intelligent behaviors of gray geese during long-distance migration, such as efficient formation flying, cooperative resting, and dynamic leadership. The algorithm simulates mechanisms like “leader goose switching,” “flock following,” and “energy conservation,” enabling a finer balance between convergence accuracy and optimization speed.

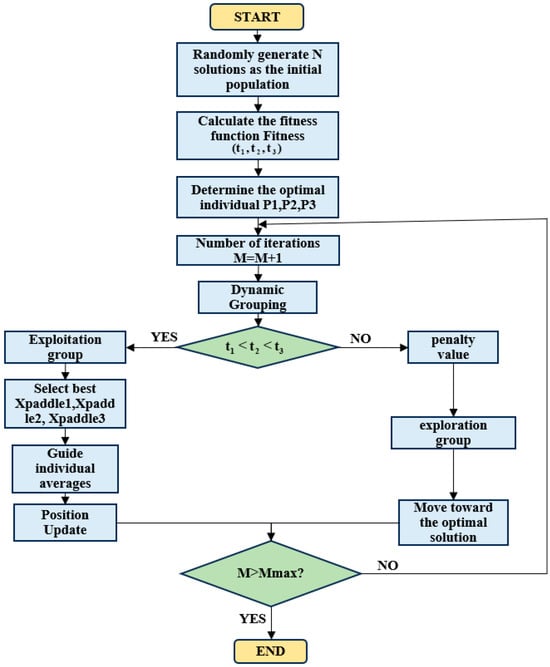

The Graylag Goose Optimization (GGO) algorithm consists of two stages: global exploration and local optimization. Based on the constraints of the objective function, a fitness function is defined. After setting the population size, all randomly generated individuals enter the initial exploration group. The population is then sorted according to fitness values, and the top N solutions in terms of fitness are defined as the exploitation group, while the remaining poorer solutions form the exploration group. Individuals that meet the fitness function criteria are assigned to the “exploitation group,” whereas those that do not are given high penalty values and re-enter the exploration group to search for solutions. The initial parameters of the population are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Origin Parameter of graylag goose population.

First, randomly generate N arbitrary solutions. The individual position update strategy of the Graylag Goose Optimization Algorithm is divided into two parts: global search by the exploration group and local optimization by the exploitation group. If an individual’s value does not meet the requirements of the fitness function, assign a high penalty value to that individual.

Explore group global search:

Strategy 1: Move toward the global best solution Xbest.

The r1 and r2 is random Vector

Strategy 2: Guided by Three Random Geese.

Partial optimization by the development team

Strategy 1: The three-sentinel geese seek the average value, where the sentinel geese individuals are selected from the three best solutions in the group based on fitness.

Strategy 2: Perturbation Near the Current Optimal Solution.

If the maximum number of iterations is reached, it is considered that the final solution has been achieved, and the iteration stops, exporting the current optimal solution. And its logical sequence diagram is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Logical Flowchart of the Graylag Goose Optimization Algorithm.

4. Algorithm Testing and Analysis

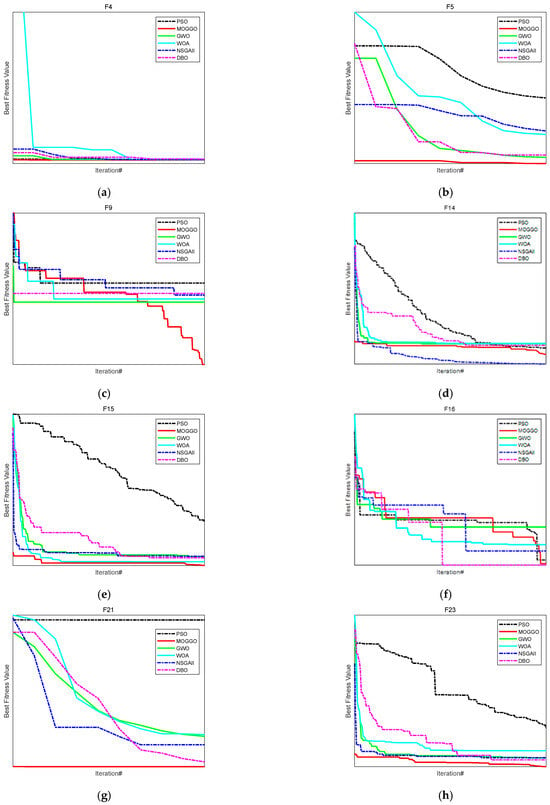

To verify the performance of the multi-objective GGO function in different workspaces, five metaheuristic optimization algorithms—Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [14], Gray Wolf Optimizer (GWO) [18], Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [26], Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGAII) [10], and Dung Beetle Optimization (DBO) [23]—were added on the MATLAB 2022B platform for comparison with the multi-objective GGO function. Two unimodal functions, four multimodal functions, and two composite functions from the CEC2013 benchmark test set were selected as objective functions, as shown in Table 4. The performance of the multi-objective GGO algorithm was evaluated by comparing the results of the test set runs.

Table 4.

CEC Function Test Results.

In Table 4, a subset of benchmark functions from the CEC2013 test suite is selected to evaluate the optimization performance of the proposed algorithm. Specifically, functions F4 and F5 are representative unimodal functions used to assess exploitation capability and convergence accuracy, whereas F9, F14, F15, F16, F21, and F23 are multimodal or composite functions designed to evaluate global search ability and robustness against local optima.

These functions cover different landscape characteristics, including high dimensionality, strong nonlinearity, and multiple local minima, which are consistent with the complexity of multi-objective trajectory optimization problems in robotic systems.

Based on the original Gray Goose Optimization (GGO) algorithm, this study further develops an improved multi-objective variant to better address the dual-objective vibration suppression trajectory optimization problem.

It should be noted that the proposed Multi-Objective Gray Goose Optimization (MOGGO) algorithm is an improved version of the original GGO algorithm. In this study, a Logistic chaotic map is introduced to enhance the diversity of the initial population, while a Gaussian (normal) disturbance mechanism is incorporated during the optimization process to improve global exploration ability and avoid premature convergence. In addition, the original single-objective GGO framework is extended to handle multi-objective optimization, making it suitable for solving the dual-objective vibration suppression trajectory planning problem. The results of the CEC2013 test set are shown in Figure 4. The results indicate that MOGGO performs the best overall on the CEC2013 test functions, significantly outperforming the comparison algorithms in terms of convergence speed, solution accuracy, and stability.

Figure 4.

Convergence Curves for a Subset of the CEC2013 Test Functions.

As shown in Figure 4a–h, the convergence behaviors of different algorithms are compared on benchmark functions F4, F5, F9, F14, F15, F16, F21, and F23. Overall, MOGGO demonstrates faster convergence speed and better solution accuracy across most test functions. In unimodal functions, the MOGGO rapidly reaches the optimal region, while in multimodal and complex functions, it maintains stable convergence and effectively avoids premature stagnation. In contrast, PSO, WOA, GWO, and NSGA-II generally exhibit slower convergence or are more prone to local optima. These results indicate that MOGGO achieves a better balance between global exploration and local exploitation.

(1) Set the forearm to rotate 120°, with the motor’s starting acceleration at 20 deg/s2. On the MATLAB platform, set the population size and number of iterations, define the main loop function of the algorithm and the displacement equation, and establish it as a fitness function according to the strict constraint t1 < t2 < t3. The fitness function can be expressed as:

Among them, 1 and 2 are the target weight values, and e is the penalty value. In Equation (19), w1 and w2 denote the weighting coefficients for motion time and residual vibration energy, respectively, satisfying w1 + w2 = 1. These parameters allow flexible trade-offs between efficiency and vibration suppression according to different operational requirements.

It is triggered when an individual does not satisfy the condition t1 < t2 < t3, and is randomly assigned a larger value to make the individual enter the exploration group to perform a deep search.

(2) Establish the relationship between t1, t2, and total time t3, and use the central difference method to derive the acceleration of the forearm. Construct an energy cost function. By combining this function with the displacement equation and assigning weight values, a composite multi-objective function is obtained. Through global search by the exploration group and local optimization by the utilization group, the current optimal solution is determined. If the maximum preset number of iterations is reached, the iteration stops.

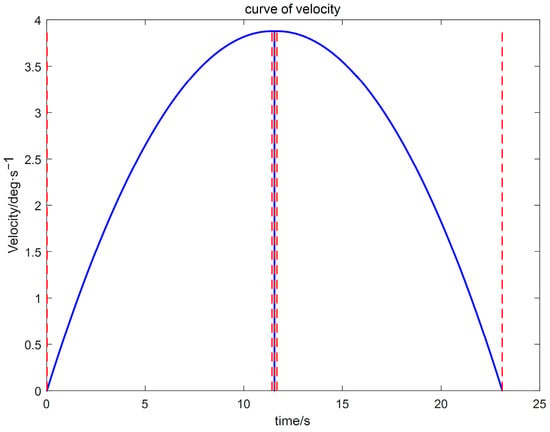

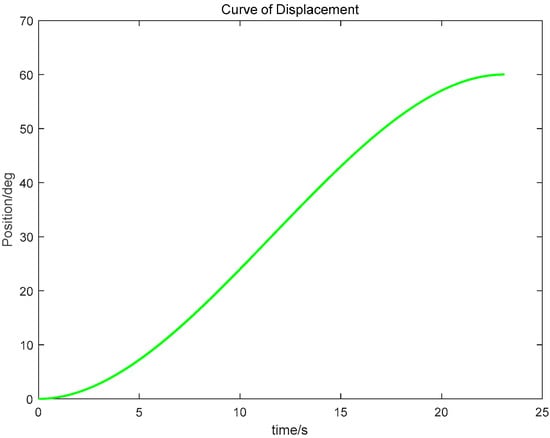

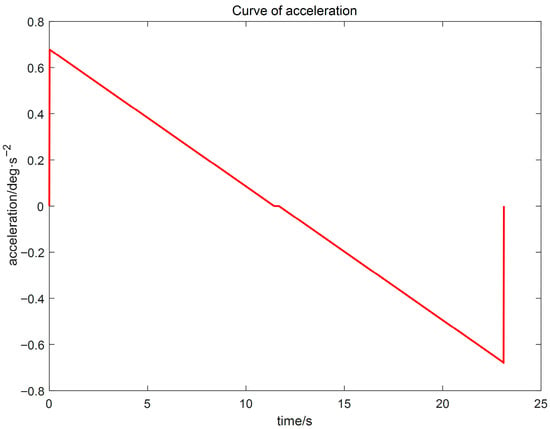

(3) Using the proposed GGO-based optimization under the prescribed constraints, the optimal switching times t1 and t2 were determined. The resulting kinematic profiles (velocity, displacement, acceleration, and jerk versus time) were then generated in MATLAB for subsequent analysis, as presented in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 5.

Velocity trajectory planning profile.

Figure 6.

Displacement–time trajectory profile.

Figure 7.

Acceleration–time profile.

The simulation results indicate that the proposed polynomial interpolation–based trajectory planning method enables the manipulator’s angular velocity to vary continuously and smoothly throughout the entire motion. This significantly mitigates mechanical vibration and impact induced by abrupt velocity variations, thereby helping to reduce oscillations of the end-effector. Moreover, the method imposes a lower computational burden on the control system, and the acceleration variation can be interpreted more intuitively substituting the optimal solution t3 into the energy cost function, the optimal vibration energy index under the prescribed weight constraint can be obtained. The double-parabola–trapezoidal velocity planning profile derived from the Graylag Goose Optimization (GGO) parameters is shown in Figure 5. Overall, the profile is relatively smooth, with no abrupt changes in velocity. Moreover, as indicated by the displacement curve in Figure 6 and the acceleration curve in Figure 7, the angular variation is gradual, and the acceleration exhibits no pronounced fluctuations.

5. Comparison Under Different Initial Input Conditions

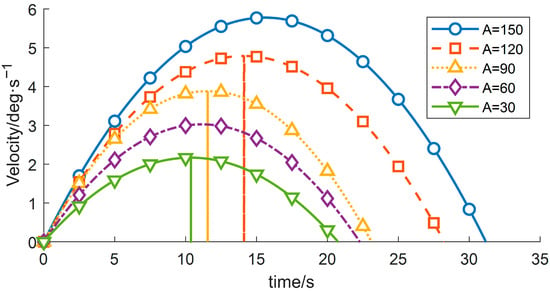

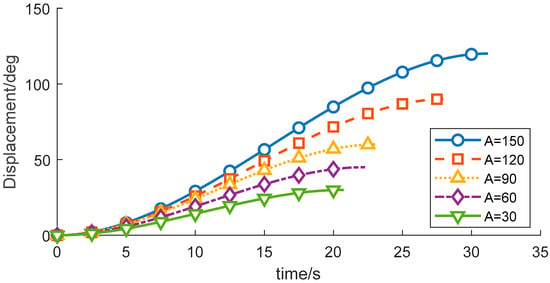

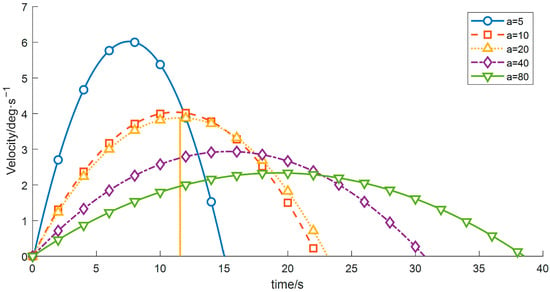

(1) By modifying the motion range of the wafer-transfer manipulator, i.e., varying the angular displacement A, the corresponding trajectories and the residual vibration energy can be rapidly fitted through iterative computation. With all other conditions unchanged, the experimental results are summarized in Table 5 and Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Table 5.

Variation in Objective Function Values of Wafer Transfer Robot Arm at Different Displacements.

Figure 8.

Velocity-time profiles for different planned displacements.

Figure 9.

Displacement-time profiles for different planned displacements.

Figure 10.

Acceleration-time profiles for different planned displacements.

As indicated in Table 5, the residual vibration energy is strongly influenced by the total angular displacement. When the angular change increases from 60° to 90°, the residual vibration energy rises by 103.28%. Therefore, constraining the forearm angular variation to within 60° can significantly suppress vibrations induced by the flexible joint.

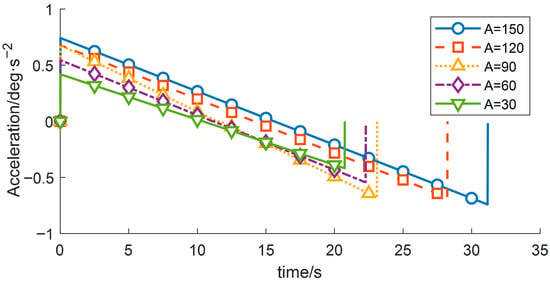

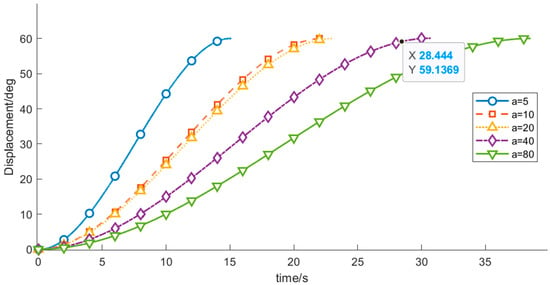

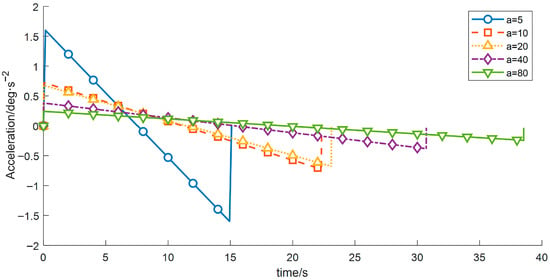

(2) To investigate the influence of the start-up acceleration on the motion performance and vibration characteristics of the wafer-transfer manipulator, comparative experiments were conducted by varying the start-up acceleration a while keeping the other control parameters constant. The results are listed in Table 6 and Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Table 6.

Variation in Objective Function Values of Wafer Transfer Robot Arm at Different Startup Acceleration.

Figure 11.

Velocity-time profiles for different start acceleration.

Figure 12.

Displacement–time profiles for different start acceleration.

Figure 13.

Acceleration–time profiles for different start acceleration.

As shown in Table 6, as a increases from 5 to 80, the overall operation time exhibits a decreasing trend, whereas the vibration energy index increases rapidly in a nonlinear manner. These results demonstrate that a larger start-up acceleration is beneficial for reducing the operation time and improving transfer efficiency. However, excessive start-up acceleration introduces stronger impact loads and excites high-frequency modes of the manipulator, leading to a substantial increase in vibration. Hence, a typical trade-off exists between efficiency and vibration suppression. Considering both efficiency and stability, a start-up acceleration of approximately a ≈ 20 deg/s2 can be regarded as a compromise range that balances operation time and vibration mitigation, and this range is advantageous for subsequent optimization and analysis.

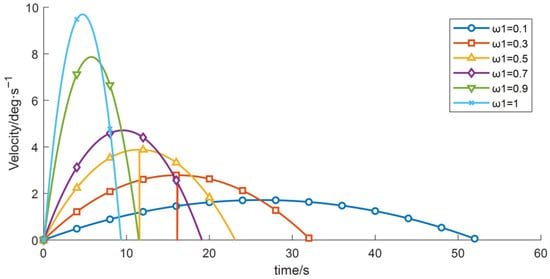

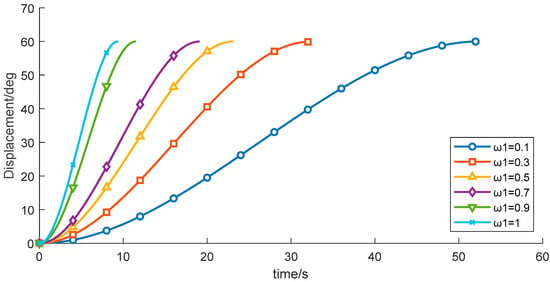

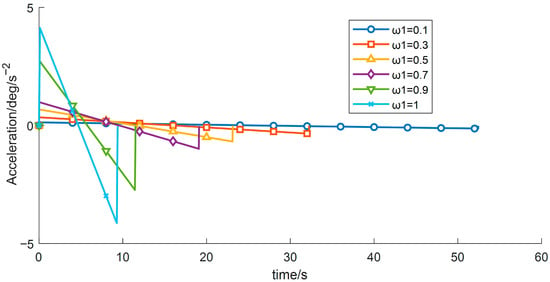

(3) With the other control parameters unchanged, comparative experiments were performed by varying the time-weighting factor w1, the results are shown in Table 7 and Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16. The experimental data indicate that, under the given constraints and operating conditions, increasing w1 gradually reduces the total time obtained from the objective function. When w1 > 0.9, the trajectory duration decreases markedly, while the vibration energy index increases sharply.

Table 7.

Variation in Objective Function Values of Wafer Transfer Robot Arm at Different Time Weight.

Figure 14.

Velocity-time profiles for different time weight.

Figure 15.

Displacement–time profiles for different start acceleration time weight.

Figure 16.

Acceleration–time profiles for different time weight.

Table 7 shows that the sensitivity of both the total operation time and the vibration energy index to w1 is relatively low, and the current optimization results therefore lie in an approximately flat Pareto region. Overall, although increasing the time weight reduces the operation time, it may induce higher vibration energy, implying greater instability and/or energy consumption.

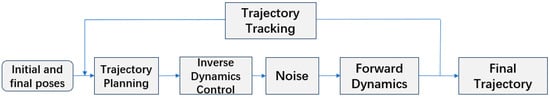

6. Simulation Analysis Based on Simulink

In this study, a Simulink-based trajectory simulation platform was Established. The optimal trajectory parameters obtained from the optimization algorithm were imported into the platform to simulate and evaluate the manipulator’s stability under external disturbances. The external disturbance shown in Figure 17 is modeled as a bounded random torque applied to the joint actuator to emulate unmodeled dynamics and environmental perturbations in wafer-handling operations. The disturbance is defined as:

where ξ(t) is a zero-mean bounded random process and τmax denotes the disturbance bound. In the Simulink implementation, ξ(t) is generated using a random source (e.g., a band-limited noise or uniform random sequence) and then constrained by saturation to ensure |τd(t)| ≤ τmax. This bounded setting provides a physically meaningful robustness test while avoiding unrealistically large excitation.

Figure 17.

Robotic Arm Simulation System Flowchart.

This represents unmodeled dynamics and external perturbations typically encountered in industrial wafer-handling environments.

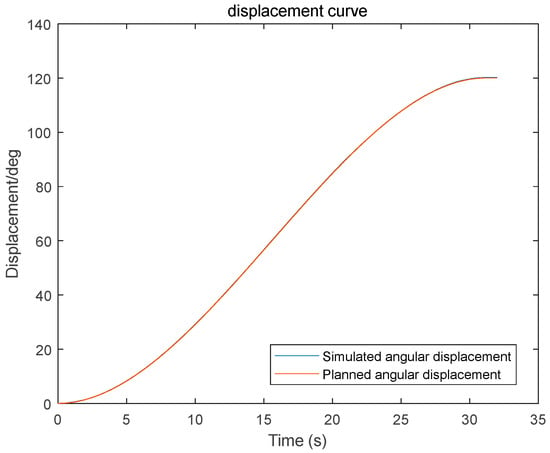

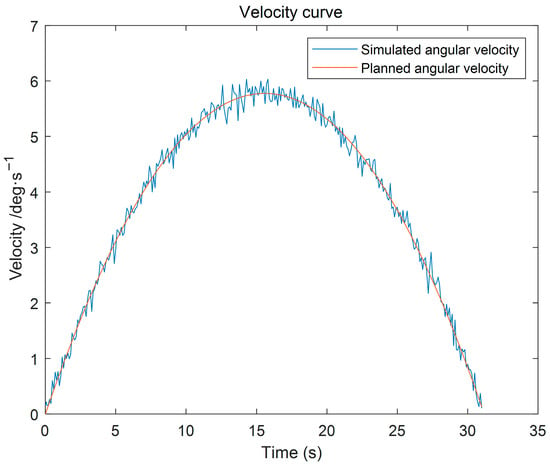

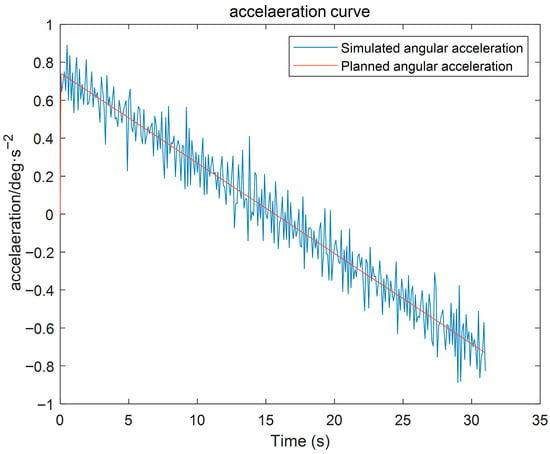

To control the robot motion, the Simulink control program first initializes the system by setting the manipulator coordinates to the prescribed initial state [39]. Based on the planned trajectory parameters obtained from the preceding simulations, a smooth-function output module is constructed to generate the reference profiles of the joint angle, angular velocity, and angular acceleration. Meanwhile, a random disturbance module is connected externally to provide an excitation torque, which is applied as the external input torque τ to the dynamic planning module. A closed-loop control function is then established according to the governing dynamic equations. The output angular acceleration is integrated twice to obtain the simulated angular velocity and angular displacement, and the resulting data are exported to spreadsheets. Furthermore, inverse kinematics is employed to inversely infer the effect of the external disturbance and back-calculate the corresponding driving torque, thereby completing the closed-loop simulation test module [40]. In this study, angular displacement, angular velocity, angular acceleration, and joint torque are adopted as evaluation metrics to assess the time-planning performance and vibration-suppression capability of the wafer-transfer robot using the Simulink test platform. The integrated simulation platform is executed, and the Scope outputs are exported to the workspace via the To Workspace function, yielding the simulation results shown in Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20.

Figure 18.

Robotic Arm Displacement Curve.

Figure 19.

Robotic Arm Velocity Curve.

Figure 20.

Robotic Arm Acceleration Curve.

As indicated by the simulation results in Figure 18, the planned joint angular displacement profile of the forearm joint is in close agreement with the simulated tracking angular displacement over the entire motion interval. The two curves almost overlap in the initial stage, the acceleration and constant-velocity transition stage, and the final deceleration stage, exhibiting an overall smooth S-shaped trajectory. In terms of tracking performance, the tracking angular displacement shows no evident overshoot or oscillation throughout the motion, and the steady-state error at the end is virtually negligible, demonstrating that the system achieves favorable dynamic response characteristics and high steady-state accuracy.

As shown by the simulation results in Figure 19, the planned angular velocity of the forearm joint agrees well with the simulated tracking angular velocity over the entire motion interval, with only a negligible deviation observed in the vicinity of the peak velocity. No evident overshoot or oscillation is observed, indicating that the controller can accurately track the desired angular-velocity command and that the system exhibits high velocity-tracking accuracy and stability. Such a smooth velocity profile is beneficial for reducing vibration levels in the joint and links, and it also prevents inertial impacts induced by abrupt acceleration/deceleration, which is crucial for maintaining posture stability and operational safety during wafer handling.

Furthermore, the planned and tracked angular accelerations of the forearm joint remain highly consistent throughout the motion, as shown in Figure 19. Only minor local high-frequency fluctuations are present, and no abrupt spikes or severe reverse jumps are detected. Therefore, the proposed planning method can fundamentally suppress structural vibrations of the manipulator, thereby supporting the stable operation of the wafer-transfer robot.

Based on the simulation results shown in Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20, the vibration suppression performance of the proposed trajectory planning method is further validated. Compared with conventional polynomial-based trajectory planning approaches, the planned joint angular displacement, velocity, and acceleration profiles exhibit smooth transitions without evident oscillations or abrupt fluctuations. In particular, the angular-displacement fluctuation is constrained within 0.01 deg/s, quantitatively indicating effective disturbance rejection and enhanced dynamic smoothness, thereby supporting the vibration-suppression effect of the proposed jerk-minimization trajectory planning strategy.

Moreover, by introducing the proposed improved multi-objective Gray Goose Optimization (MOGGO) algorithm, the solution quality of the dual-objective vibration suppression trajectory optimization problem is significantly enhanced, benefiting from improved population diversity and global search capability.

To further evaluate the robustness of the proposed method, random external torque disturbances are introduced into the system. Under such disturbances, the tracking responses remain highly consistent with the planned trajectories, and no significant overshoot or residual oscillation is observed during acceleration, constant-velocity, or deceleration phases. In particular, the angular velocity fluctuation is effectively constrained within a small range, indicating that high-frequency vibration components are significantly suppressed. These results confirm that minimizing the jerk-based vibration energy index leads to improved dynamic smoothness and enhanced vibration suppression capability of the wafer-handling robotic arm.

7. Conclusions

This paper addresses the micro-vibration problem of wafer transfer robotic arms and proposes and validates a vibration suppression trajectory optimization method based on the Graylag Goose Optimization (GGO) algorithm. After theoretical derivation and simulation tests, the following conclusions are drawn:

(1) This study established and analyzed the dynamic model of the wafer transfer robotic arm based on the Lagrange method, providing a theoretical foundation for vibration suppression trajectory planning. The model fully considers the flexible dynamic characteristics of the robotic arm and accurately describes the system’s dynamic behavior.

(2) By combining a multi-segment polynomial trajectory planning method with a residual vibration energy dissipation equation, a multi-objective optimization function targeting both time-optimal performance and vibration energy was constructed. By reasonably setting weight coefficients according to working conditions, a multi-objective coordinated optimization was achieved to ensure trajectory smoothness and minimal residual vibration energy.

(3) Simulation results show that when solving the dual-objective vibration suppression trajectory optimization, introducing the proposed improved multi-objective Gray Goose Optimization (MOGGO) algorithm effectively solves the dual-objective problem. The results indicate that the derived trajectory, when subjected to random external disturbances, maintains speed fluctuations basically within 0.01 deg/s, demonstrating good vibration suppression performance.

However, this study only performed Pareto optimization for two objectives and has not been extended to higher-dimensional, multi-objective optimization problems. Moreover, it is limited to SIMULINK and MATLAB simulation environments. Future work will expand to validation on a PLC platform and further explore the algorithm’s applicability under more complex operating conditions and with additional optimization objectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J.; Software, P.H.; Formal analysis, P.H.; Writing—original draft, P.H.; Writing—review & editing, P.H.; Supervision, Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Basic Scientific Research Project of Higher EducationInstitutions of Liaoning Province (grant number JYTQN2023064).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chandu, H.S. A Survey of Semiconductor Wafer Fabrication Technologies: Advances and Future Trends. Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 2023, 10, 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Kang, R.; Dong, Z.; Gao, S. Ultraprecision machining for single-crystal silicon carbide wafers: State-of-the-art and prospectives. J. Adv. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 2025010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.; Sharma, A.; Singh, A.K. Silicon wafers; its manufacturing processes and finishing techniques: An overview. Silicon 2022, 14, 12031–12047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Tang, L.; Cong, D.; Qiao, J. AcArm: A Novel Semiconductor Wafer Handling Robot. In Proceedings of the 2023 China Semiconductor Technology International Conference (CSTIC), Shanghai, China, 26–27 June 2023; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Oberhans, S.; Heiss, W.; Pietsch, G.J. Crystal Damage and Surface Morphology in Industrial Diamond Wire Slicing of 300 mm Monocrystalline Silicon Wafers for Microelectronic Devices. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2025, 10, 2401432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Park, J.; Bae, M.; Park, D.; Park, C.; Do, H.M.; Choi, T.; Kim, D.H.; Kyung, J. Advanced 2-DOF counterbalance mechanism based on gear units and springs to minimize required torques of robot arm. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 6320–6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanga, C.; Banb, L. Vibration control of piezoelectric flexible manipulator based on machine vision and improved PID. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Computer Applications (ICPECA), Shenyang, China, 22–24 January 2021; pp. 886–888. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Li, Z.; Sun, G. The robot arm control based on RBF with incremental PID and sliding mode robustness. In Proceedings of the 2019 WRC Symposium on Advanced Robotics and Automation (WRC SARA), Beijing, China, 21–22 August 2019; pp. 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wazzan, A.N.; Basil, N.; Raad, M.; Mohammed, H.K. PID controller with robotic arm using optimization algorithm. Int. J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 7, 3746–3751. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Xia, Q.; Chen, M.; Cheng, S. Multi-objective optimal trajectory planning for robotic arms using deep reinforcement learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Cao, J.; Peng, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Wang, S. ELM-PSO-GA based inverse solution algorithm for robotic arm. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference of Clean Energy and Electrical Engineering (ICCEEE), Changchun, China, 18–21 July 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, J.; Hu, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Xing, Z. Trajectory Optimization of Robotic Arm Based on Improved Simulated Annealing Genetic Algorithm. J. Syst. Simul. 2025, 37, 404–412. [Google Scholar]

- Kheshti, M.R.; Tavakolpour-Saleh, A.R.; Razavi-Far, R.; Zarei, J.; Saif, M. Genetic Algorithm-Based Sliding Mode Control of a Human Arm Model. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 2968–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Jia, D.; Li, Z.; He, Z. Trajectory planning of robotic arm based on particle swarm optimization algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonoyama, K.; Liu, Z.; Fujiwara, T.; Alam, M.M.; Nishi, T. Energy-efficient robot configuration and motion planning using genetic algorithm and particle swarm optimization. Energies 2022, 15, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, O.E.; Turgut, M.S.; Kırtepe, E. A systematic review of the emerging metaheuristic algorithms on solving complex optimization problems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 14275–14378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, D.; Gupta, M.K.; Sharma, A. Intelligent control of robotic manipulators: A comprehensive review. Spat. Inf. Res. 2023, 31, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Zhai, W. Trajectory planning of the robotic arm using improved grey wolf algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Mechatronics, Robotics, and Artificial Intelligence (MRAI), Jinan, China, 19–21 June 2025; pp. 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, A.; Dalla, V.K. Jerk optimized motion planning of redundant space robot based on grey-wolf optimization approach. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 2687–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodabadi, M.J. An optimal robust fuzzy adaptive integral sliding mode controller based upon a multi-objective grey wolf optimization algorithm for a nonlinear uncertain chaotic system. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 167, 113092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Q.C.; Xu, X.R.; Li, Q.Q.; Zhang, H. Robotic arm time–jerk optimal trajectory based on improved dingo optimization. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lv, X.; Li, Y.; Jing, L.; Fang, X.; Peng, G.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, W. A novel hybrid improved dingo algorithm for unmanned aerial vehicle path planning. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2025, 47, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, S.; Tan, S.; Yang, P.; Zhao, C. Improved dung beetle optimization algorithm based inverse kinematics solution for robotic arm. Robotica 2025, 43, 3488–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyianto, A.; Yazid, E.; Mirdanies, M.; Ardiansyah, R.A.; Ramadiansyah, M.L. Optimization of PD controller using ACO for the trajectory tracking of a ship-mounted two-DOF manipulator system. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Information Technology, Information Systems and Electrical Engineering (ICITISEE), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 13–14 December 2022; pp. 634–638. [Google Scholar]

- Abro, G.E.M.; Mahmoud, E. A Hybrid PSO-ACO Algorithm for Precise Localization and Geometric Error Reduction in Industrial Robots. Instrumentation 2025, 12, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wu, Z.; Bao, T. Time-jerk optimal trajectory planning of industrial robots based on a hybrid WOA-GA algorithm. Processes 2022, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Wang, G.; Ye, H. Optimal Trajectory Planning for Robotic Arm Based on Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Service Robotics (ICoSR), Hangzhou, China, 26–28 July 2024; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- El-Kenawy, E.S.; Khodadadi, N.; Mirjalili, S.; Abdelhamid, A.A.; Eid, M.M.; Ibrahim, A. Greylag goose optimization: Nature-inspired optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Gupta, K.; Jangir, K.; Jain, P.; Malakar, P. Multi-objective Greylag Goose Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Advancement in Computation & Computer Technologies (InCACCT), Gharuan, India, 2–3 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.Y.; Zhao, B.; Sun, R.H. Research on Motion Control and Wafer-Centering Algorithm of Wafer-Handling Robot in Semiconductor Manufacturing. Sensors 2023, 23, 8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, N.; Lee, H.; Shin, J.; Choi, Y.; Cho, K.J.; Rodrigue, H. Hybrid hard-soft robotic joint and robotic arm based on pneumatic origami chambers. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2024, 30, 657–667. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, L.; Apostle, M.; Aveta, F. High-Precision Robotic Arm for Silicon Wafer Handling and Alignment in Small-Scale Semiconductor Fabrication. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 15th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), Yorktown Heights, NY, USA, 17–19 October 2024; pp. 190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Zhou, M.; Abusorrah, A. Virtual cell-based scheduling approach to single-robotic-arm cluster tools subject to wafer residency time constraints. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.T.; Li, T.H.; Chen, M.X.; Lin, S.J.; Yang, C.Y.; Wang, C.W.; Tsao, H.M.; Zhan, C.H. A fully automatic calibration for vision-based selective compliance assembly robot arm and its application to intelligent wafer inspection scheduling. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 50100–50113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zheng, Z. Influence of dynamic accuracy constraints of manipulator of wafer transmission robot on scheduling and control of single-armed cluster tools. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 7714–7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, M.A.A.; Elgohr, A.T.; Khater, H. Path planning for a 6 DOF robotic arm based on whale optimization algorithm and genetic algorithm. J. Eng. Res. 2023, 7, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani Amiri, M.; Ramli, R. Intelligent trajectory tracking behavior of a multi-joint robotic arm via genetic–swarm optimization for the inverse kinematic solution. Sensors 2021, 21, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Xu, Q.; Ju, W.; Zhang, T. Inverse kinematics of large hydraulic manipulator arm based on ASWO optimized BP neural network. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Optimization of energy consumption in industrial robots, a review. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Xie, C. An improved particle swarm optimization algorithm for inverse kinematics solution of multi-DOF serial robotic manipulators. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 13695–13708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.