Abstract

The extraction of the light stripe center is a pivotal step in line-structured light vision measurement. This paper addresses a key challenge in the online measurement of train wheel treads, where the diverse and complex profile characteristics of the tread surface lead to uneven gray-level distribution and varying width features in the stripe image, ultimately degrading the accuracy of center extraction. To solve this problem, a region-adaptive multiscale method for light stripe center extraction is proposed. First, potential light stripe regions are identified and enhanced based on the gray-gradient features of the image, enabling precise segmentation. Subsequently, by normalizing the feature responses under Gaussian kernels with different scales, the locally optimal scale parameter (σ) is determined adaptively for each stripe region. Sub-pixel center extraction is then performed using the Hessian matrix corresponding to this optimal σ. Experimental results demonstrate that under on-site conditions featuring uneven wheel surface reflectivity, the proposed method can reliably extract light stripe centers with high stability. It achieves a repeatability of 0.10 mm, with mean measurement errors of 0.12 mm for flange height and 0.10 mm for flange thickness, thereby enhancing both stability and accuracy in industrial measurement environments. The repeatability and reproducibility of the method were further validated through repeated testing of multiple wheels.

1. Introduction

Machine vision-based technology has been extensively employed in dimensional metrology systems. In this technology, object-related information is captured via image sensors, with key features extracted through edge detection, deep learning, and other relevant techniques, enabling dimensional measurement and surface defect identification [1,2,3]. As a specialized branch of machine vision, line-structured light vision sensing technology been widely embraced in train wheelset profile measurement owing to its inherent merits of non-contact operation, high precision, and reliable sensing performance [4,5,6]. In such a system, a line-structured light pattern is projected onto the wheel tread surface by a laser, and the stripe image containing profile information is captured by an industrial camera. The tread profile is then reconstructed through light stripe center extraction and coordinate transformation [7,8]. The accuracy of light stripe center extraction directly influences the accuracy of the measurement process. Therefore, numerous studies on light stripe center extraction have been carried out in recent years, and the relevant methods are primarily categorized into geometric center methods and energy center methods [9,10,11]. Geometric center methods typically include the threshold method [12], extreme value method [13], edge method [14], refinement extraction [15], and improvements based on these approaches [16]. These methods are based on the assumption that the light stripe center coincides with its geometric center, offering straightforward implementation and high computational efficiency. However, they often ignore the actual gray intensity distribution of the light stripe on the measured surface. Energy center methods include the gray centroid method [9,17], curve fitting [18], directional template methods [19], and algorithms based on the Hessian matrix [20,21,22]. These methods characterize the light stripe’s intensity distribution based on its gray-level distribution, treating the stripe center as the intensity peak. Such approaches generally exhibit greater stability against interference and higher accuracy. Over the past few years, the Hessian matrix, which characterizes the gray-level gradient distribution in images, has been extensively utilized by researchers worldwide for light stripe center extraction and image segmentation [23,24,25]. As a key parameter for Hessian matrix computation, the standard deviation (σ) of the Gaussian convolution kernel influences the accuracy and stability of light stripe center extraction by modulating the degree of image smoothing [26,27,28]. Traditional Steger methods employ a Gaussian kernel with a fixed σ value, which fails to adapt to images with significant variations in stripe width, leading to reduced center extraction accuracy and measurement errors. Zhao et al. [29] employed regional segmentation to process complex patterns, applied tailored convolution operations to different regions to enhance stripe quality, and extracted the stripe center by operating on specific areas with corresponding convolution kernels. Li et al. [30] proposed a hardware-oriented algorithm that estimates the local stripe width and optimal Gaussian kernel size via pixel traversal for center extraction. To address the challenge of light stripe center extraction on highly reflective surfaces, Bo et al. [26] proposed using a BPNN (Back Propagation Neural Network) to estimate local stripe widths and build an adapted Hessian matrix for precise sub-pixel center calculation. Peng et al. [31] employed a modified YOLOv8 network to segment light stripes and estimate their widths. Subsequently, multi-scale Gaussian templates were constructed based on the estimated widths to achieve sub-pixel center extraction. Jiang et al. [32] adopted a U-Net architecture to segment light stripes from complex backgrounds, followed by the application of the Steger algorithm for precise sub-pixel center extraction. However, current methods have not yet achieved an optimal balance among adaptability, efficiency, and practicality: traditional approaches struggle to flexibly handle varying stripe widths and measured surfaces with complex, rich features, while deep learning–based methods are constrained by their reliance on large datasets, substantial computational resources, and system complexity. Therefore, a universal and adaptive approach for light stripe center extraction that is independent of extensive training data retains substantial research value and industrial significance.

To address the challenges of low accuracy and stability in extracting stripe centerlines caused by varying stripe widths and non-uniform grayscale distributions in industrial applications, a multi-scale adaptive center extraction method is proposed to improve the accuracy and stability of center extraction by achieving scale matching between Gaussian kernel parameters σ and stripe width w. First, the feature responses of the light stripe at multiple σ scales are calculated to enhance stripe features and achieve stripe segmentation. Then, by adaptively selecting the optimal σ from normalized multi-scale eigenvalues, a scale parameter best matching the local stripe width is determined for center extraction, enabling sub-pixel coordinate acquisition. By integrating multi-scale light stripe gradient features, this method effectively addresses the issues of uneven gray-level distribution and varying stripe widths in the image, exhibiting high stability and accuracy.

2. Light Stripe Image Acquisition and Analysis

2.1. Measurement System Structure

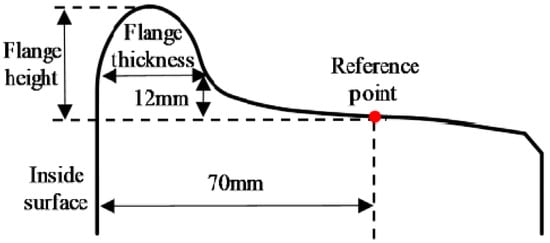

The geometric parameters of train wheel profiles mainly include flange height and flange thickness. The LM-type wheel profile commonly used in China, along with its parameter definitions, is illustrated in Figure 1. At a distance of 70 mm from the inner side of the wheel, a point is designated as the reference point. The vertical distance from the reference point to the flange top is defined as the flange height. The horizontal width of the flange, measured 12 mm above the reference point, is defined as the flange thickness.

Figure 1.

Definition of wheel profile geometric parameters.

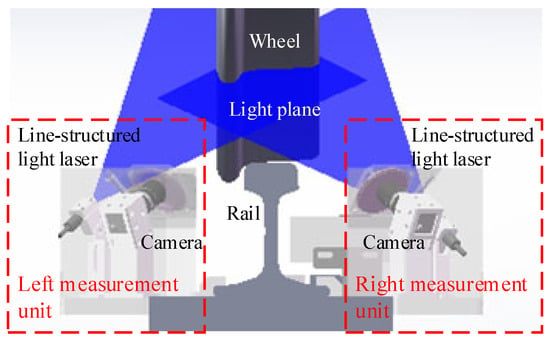

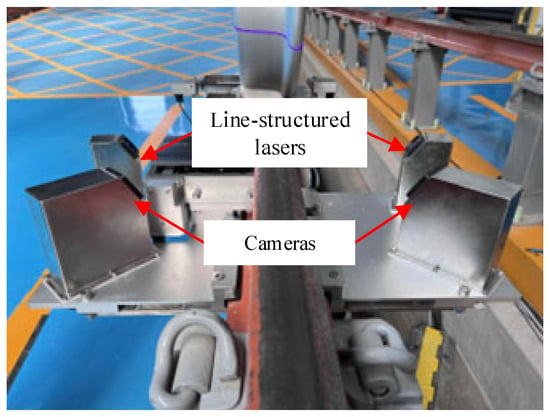

A wheel profile measurement system was designed to achieve online non-contact detection of the tread profile, as illustrated in Figure 2. The system comprises left and right measurement units installed symmetrically along the rail. Each unit integrates a line-structured-light laser and an industrial camera, forming a vision sensor. Two sets of line-structured-light lasers project structured light onto the wheel tread from both sides of the rail, covering the complete profile. Cameras on each side capture images of the profile light stripes from specific angles. The center coordinates of the stripes are extracted from the images of both sides and are then converted into real-world profile coordinates using pre-calibrated camera parameters. Finally, key profile parameters are calculated according to their defined specifications.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the wheel profile measurement system.

2.2. Light Stripe Feature Analysis

An ideal line-structured light stripe exhibits varying widths without significant distortion or fluctuation, smooth and continuous gray-level transitions with high contrast against the background, and the distribution of normal light intensity is usually approximately a Gaussian distribution [18,33]. However, due to contact wear between the wheel and rail, the surface roughness of the wheel tread varies by region, leading to non-uniform reflectivity. This variability poses a major challenge for accurate measurement using laser vision sensors, as it induces stripe width variations and uneven gray-level distribution, thereby degrading the quality of acquired stripe images. Such degradation interferes with subsequent light stripe segmentation and center extraction, ultimately reducing the accuracy of both center extraction and profile detection [34,35].

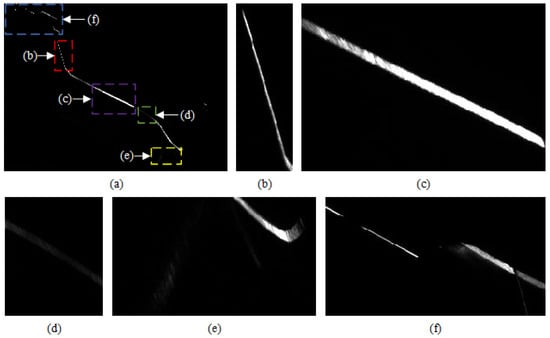

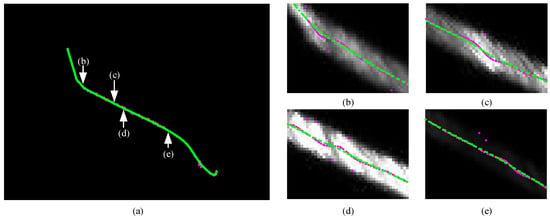

The real wheel light stripe images acquired from the on-site experiment are shown in Figure 3. It can be seen that the light stripes in different regions exhibit distinct characteristics.

Figure 3.

Characteristics of light stripe images from actual wheel treads. (a) Schematic diagram of regions corresponding to different stripe characteristics; (b) Narrow stripe; (c) Wide stripe; (d) Low-gray-value stripe; (e) Stray spots; (f) Stripe from other components.

- (1)

- Significant variation in light stripe width

Due to the relative positioning of the laser and camera, the width of the light stripe varies across the image, ranging from 5 to 21 pixels. Specifically, regions farther from the camera, such as the outer side of the wheel shown in Figure 3b, appear narrower, whereas regions closer to the camera, such as the tread reference point shown in Figure 3c, appear wider. These variations in stripe width, combined with non-smooth gray-level transitions and varying stripe curvature, lead to center extraction errors when using the conventional Steger method with a fixed σ.

- (2)

- Uneven gray-level distribution.

When line-structured light is projected onto a tread with non-uniform surface roughness, significant differences in the gray level of the light stripe arise [36,37]. In particular, regions subjected to long-term wheel-rail contact exhibit increased reflectivity due to wear, causing the gray-level of the stripe to approach that of the background, as seen in the flange root region shown in Figure 3d. This makes it difficult for image segmentation methods based on gray-level thresholding to distinguish the stripe from background noise, further complicating center extraction.

- (3)

- Stray spots caused by complex profile geometry.

Owing to the complex curvature of the wheel profile, stray light spots may appear along the circumferential direction in regions such as the wheel flange, as illustrated in Figure 3e. These spots interfere with accurate centerline extraction and compromise measurement accuracy.

- (4)

- Interference from other components.

In practical applications, adjacent components such as axle boxes and brake shoes located on the outer side of the wheel can produce extraneous light stripes in the image, as shown in Figure 3f. To avoid affecting the subsequent calculation of wheel profile parameters, these irrelevant light stripes must be removed.

Given that the online measurement of geometric parameters for train wheelsets is a dynamic process, train speed fluctuates and measurement positions are inconsistent. Additionally, the impact of ambient light is variable, which further intensifies the variations in the width and gray-level distribution of the light stripes. Therefore, a targeted light stripe centerline extraction method is urgently needed. Based on the aforementioned light stripe characteristics, this paper proposes a corresponding centerline extraction method to achieve accurate, highly anti-interference light stripe centerline extraction for on-site measurement images.

3. Multiscale Adaptive Method for Light Stripe Center Extraction

3.1. Principle of the Multi-Scale Adaptive Mechanism

The standard deviation σ of the Gaussian convolution kernel determines the spatial scale of its smoothing effect on light stripes, and σ is positively correlated with the smoothing effect. In conventional laser stripe processing methods, such as the Steger algorithm, the core parameter σ must satisfy [38,39]. Under this condition, the second-order derivative exhibits a unique minimum within the stripe interval [−w, w], which corresponds to the stripe center. Qi et al. evaluated the statistical behavior of the Steger method in extracting the center of light stripes and concluded that the distribution of center extraction behavior in light stripe images follows a normal distribution [40]:

where μ represents the true center of the light stripe, and σl represents the standard deviation of the extracted center position, which can be expressed as:

where σ represents the Gaussian kernel parameter, SNR represents the signal-to-noise ratio of a stripe image.

It can be seen from Equation (2) that the smaller the σl corresponds to more stable the center extraction results. When considering the confidence interval, σl can be used to characterize the accuracy of center extraction. For light stripes with different widths, a fixed σ yields drastically different smoothing effects. For narrow stripes, a large fixed σ tends to cause over-smoothing, blurring the inherent gray gradient of the strip and thereby reducing the center extraction accuracy. For stripes matching σ, the Gaussian kernel can effectively suppress noise without blurring the gray gradient features, resulting in the highest accuracy. For wide stripes, a small fixed σ fails to sufficiently suppress noise in the wide gradient region, thereby greatly reducing accuracy.

With the stripe width w fixed, adjusting σ directly modulates the balance between noise suppression and feature preservation. As σ increases from small to large values, the accuracy increases first and then decreases. For small σ values, the smoothing effect is insufficient, making gradient calculations highly sensitive to noise, increasing errors in center extraction. When σ is matched to w, the Gaussian kernel effectively suppresses noise, while retaining the stripe’s intrinsic gradient features, thereby maximizing the accuracy of center extraction. For large σ values, excessive smoothing can blur geometric details such as curvature and inflection points, and mix directional information from different positions, resulting in increased center extraction errors.

However, for images with variations in stripe widths, a fixed σ value cannot adapt to such complexity [23,26,41]. Given the aforementioned challenges, for laser stripe images with varying widths, the adoption of a fixed Gaussian kernel standard deviation σ inevitably degrades the center extraction accuracy; additionally, uneven grayscale distribution of the stripe itself and low contrast between the stripe and the background further exacerbate the difficulty of precise stripe segmentation. These issues collectively restrict the practical applicability of baseline methods in dynamic measurement scenarios, rendering the development of a targeted improvement scheme imperative.

The core of the multi-scale adaptive mechanism for stripe center extraction lies in the scale matching between the Gaussian kernel parameter σ and the stripe width w, a dynamic balance that achieves noise suppression and feature preservation. The proposed region-adaptive multiscale extraction method is implemented as follows:

- (1)

- Calculate the multiscale Hessian matrix and the gray gradient features of the light stripe image.

- (2)

- Achieve light stripe region localization and segmentation through multiscale adaptive feature enhancement.

- (3)

- Precisely locate the sub-pixel coordinates of the light stripe through adaptive Gaussian scale selection based on maximizing the normalized multiscale eigenvalues.

3.2. Multiscale Feature Computation

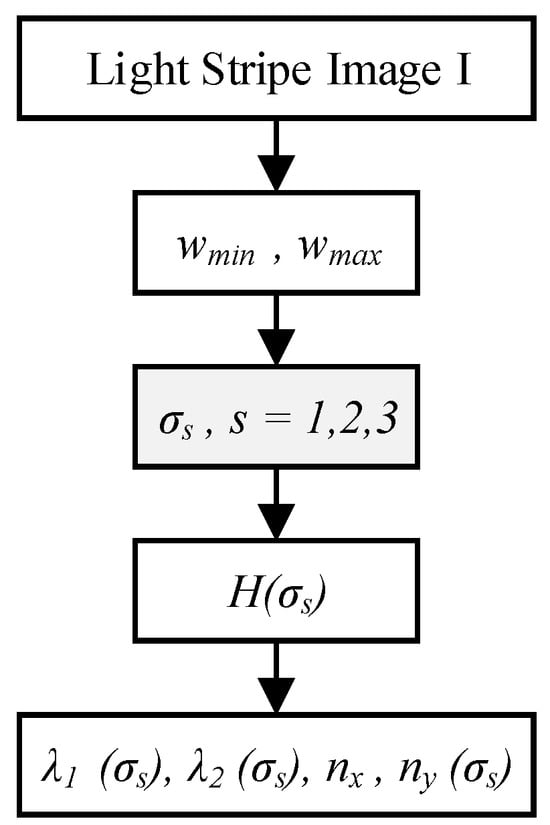

The Hessian matrix of the light stripe image I is computed using a multiscale Gaussian convolution kernel. The steps are illustrated in Figure 4:

Figure 4.

Flowchart of multiscale feature computation.

First, based on the width range of the light stripe [wmin, wmax], three scale parameters σs (s = 1, 2, 3) are calculated to cover the expected stripe widths. These scale parameters must satisfy the condition , and are specifically defined as: ,, .

Subsequently, the Hessian matrix H(σs) at each scale is obtained by convolving the image I with the second-order derivatives of the Gaussian function G (σs).

where Ixx, Iyy, and Ixy represent the second-order partial derivatives of the image.

At the center of the light stripe, the eigenvalue λ1 (where |λ1| > |λ2|) of H(σ) typically reaches a minimum, reflecting a significant variation in the gray-level gradient of the stripe. Its corresponding eigenvector (nx, ny) indicates the normal direction of the stripe.

3.3. Multiscale Adaptive Light Stripe Enhancement and Segmentation

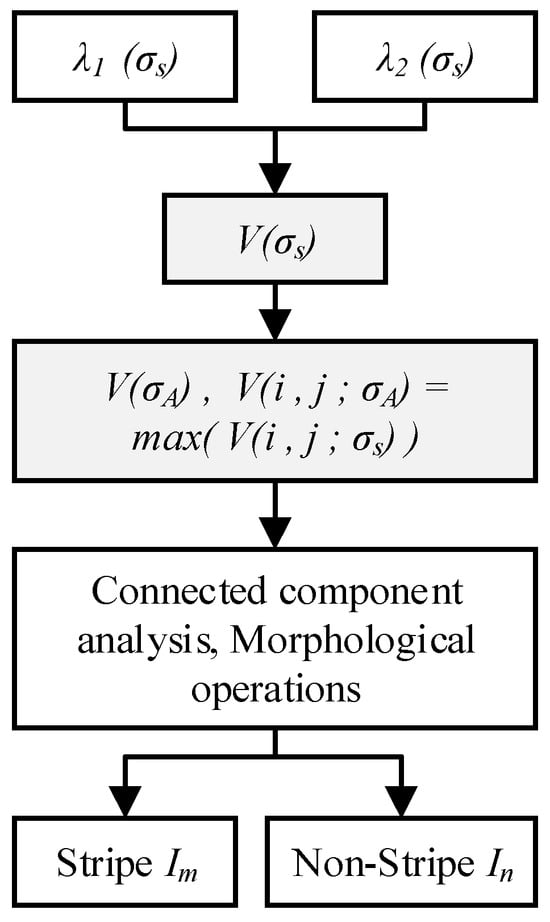

To address the difficulty in segmenting light stripes caused by non-uniform gray-level and varying widths distribution, a feature response is constructed using multiscale Hessian eigenvalues, which not only enhances stripe features but also facilitates robust segmentation. The corresponding steps are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of light stripe enhancement and segmentation.

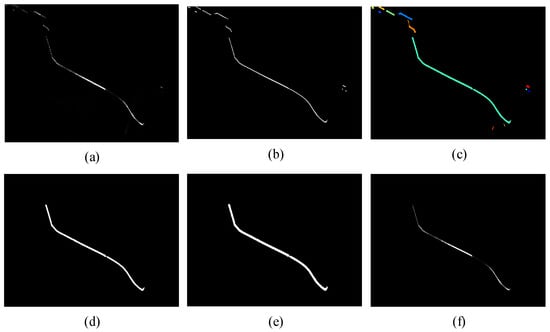

First, the multiscale stripe response V(σs) is calculated. Based on the multiscale eigenvalues λ1 (σs) and λ2 (σs), the feature response function defined in Equation (4) is constructed. This function suppresses the circularity features of the stripe according to Equation (5) and attenuates low-gray-level features according to Equation (6). Consequently, it effectively preserves stripe information and characteristics within complex image backgrounds. Specifically, it yields high response values for stripes with varying widths and gray levels while outputting low response values for background noise and stray spots, leading to effective feature enhancement [42]. The original image and the enhancement result are shown in Figure 6a and Figure 6b, respectively. It can be seen that the low-gray-level regions of the light stripe are effectively enhanced, thereby preventing the loss of stripe information during segmentation and center extraction.

where RA represents the circularity feature of the pixel, used to filter out isolated points and non-linear stray spots; S is employed to suppress low-gray-level background noise; β and c are adjustable parameters that regulate the sensitivity of RA and S, respectively.

Figure 6.

Light stripe segmentation process. (a) Original image; (b) Feature-enhanced result, where different colors represent different connected domains; (c) Connected components; (d) Stripe-connected component; (e) Stripe region mask; (f) Segmented stripe image.

Subsequently, an adaptive multiscale response selection is performed. For each pixel in the image, the maximum response value max(V(i, j, σs)) across all scales is selected. This yields the maximum response map V(σA), which achieves enhanced characterization of the light stripe features.

Finally, light stripe segmentation is performed. The maximum response map V(σA) is converted into a binary image using a response threshold Vth. Connected component analysis is then conducted based on pixel connectivity, with the result shown in Figure 6c. By analyzing the size and shape features of the connected components, the component corresponding to the light stripe is identified, as illustrated in Figure 6d. At this stage, the connected component containing the light stripe retains its positional information. Morphological operations are applied to fill small holes within the stripe region, forming a mask of the stripe area, as seen in Figure 6e. Finally, the light stripe region image Im is extracted using this mask, while pixels in other non-stripe regions In are set to zero, thereby completing the segmentation, shown in Figure 6f. The segmented light stripe image is then used for subsequent center extraction tasks.

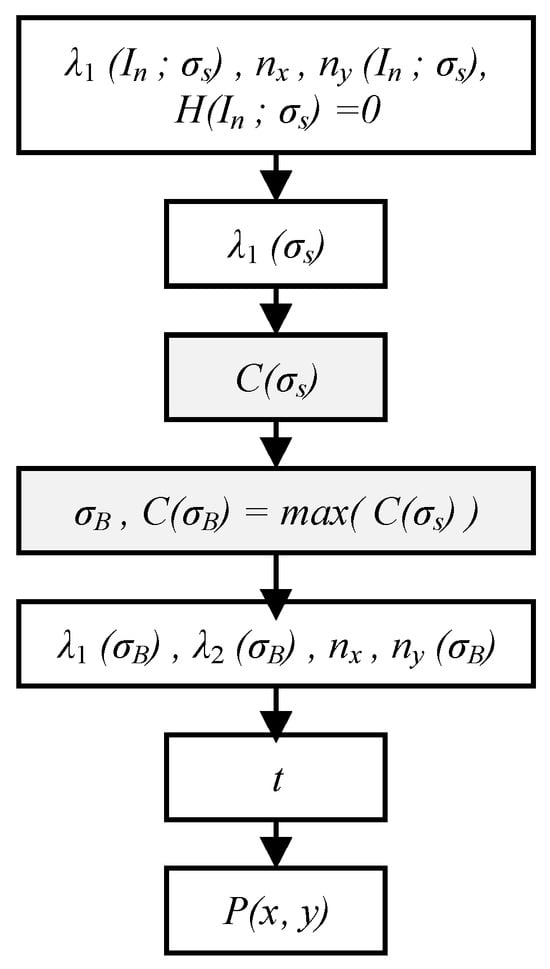

3.4. Multiscale Adaptive Light Stripe Center Extraction

The procedure for light stripe center extraction is illustrated in Figure 7. First, the stripe features λ1, nx, ny, and H in the non-stripe region In are set to zero. Next, the Gaussian kernel σA best suited to the local stripe width is determined. Since smaller σ values yield larger eigenvalues λ1 within the stripe region, the eigenvalues λ1 must be normalized using Equation (7) during the adaptive multiscale feature selection [43]. The normalization operator C(σs) compensates for the attenuation of the gray gradient and eigenvalues caused by larger scales, ensuring comparability of eigenvalues across different scales.

Figure 7.

Flowchart of multiscale adaptive center extraction.

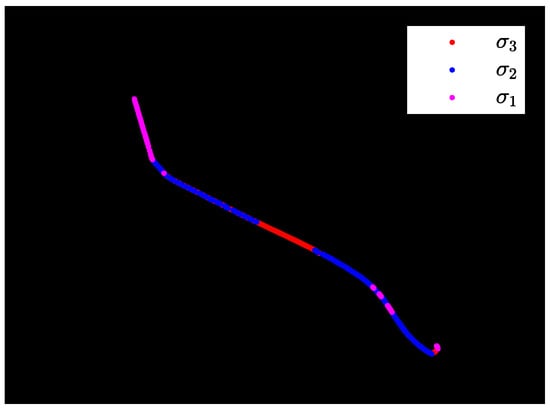

In this step, the scale parameter σB corresponding to the maximum normalized operator max(C(σs)) optimally matches the local stripe width. Figure 8 shows the optimal σ selected for different regions of a light stripe. This approach achieves precise adaptation to complex scenes with globally inconsistent stripe widths, effectively overcoming the limitation of the traditional Steger algorithm, where a fixed Gaussian kernel size cannot adapt to varying stripe widths, which leads to reduced center extraction accuracy.

Figure 8.

Optimal Gaussian kernel for different light stripe regions.

Next, the sub-pixel offset of the light stripe center is calculated. A second-order Taylor expansion is performed at the initially located stripe center coordinates P0(x0, y0) using the eigenvector and the Hessian matrix corresponding to σB. The sub-pixel offset t at this point is computed according to Equation (8):

where nx and ny represent the normal vector of the light stripe at the point, and Ix, Iy, Ixx, Ixy, and Iyy denote the first- and second-order derivatives of the pixel’s gray value, respectively.

Finally, the sub-pixel coordinates P(x, y) of the light stripe center are calculated. The pixel-level coordinates are integrated with the sub-pixel offset according to Equation (9). The constraint in Equation (10) eliminates redundant information from the multiscale adaptive selection process, achieving high-accuracy light stripe coordinate extraction

The center extraction results of the proposed method and the Steger method are compared as shown in Figure 9, marked in green and purple, respectively. Subfigures (b)–(e) provide magnified views of the center extraction results. When a small σ is used, two symmetric minima of the second derivative may form on both sides of the stripe coordinate, resulting in spurious center points in the output. Additionally, extracting the center from stripes with non-smooth gray-level variations introduces further errors. Conversely, a large σ tends to smooth corner regions of the stripe into arcs, causing the extracted centerline to lose genuine geometric detail, while excessive blurring in narrow stripe regions leads to deviations in the center coordinates. The proposed method overcomes these limitations by performing region-adaptive selection of the stripe width based on multiscale maximum normalized eigenvalues, thereby improving the accuracy of center extraction.

Figure 9.

Results of light stripe center extraction for wheel profile. (a) Comparison of center extraction results; (b) Corner region; (c) Region with uneven gray levels; (d) Bright stripe region; (e) Dark stripe region. Green dots represent the center coordinates extracted by the proposed method, while pink dots represent those extracted by the Steger method.

4. Results and Discussion

To validate the accuracy of the proposed method for light stripe center extraction under conditions of non-uniform surface reflectivity, experiments were conducted using the wheel profile measurement system installed at the National Railway Test Center of the China Academy of Railway Sciences. The measurement system mainly consists of an industrial personal computer (IPC) and a sensor module. The control and data processing capabilities of the system are implemented on an Advantech IPC-610L industrial personal computer, (Advantech, Kunshan, China), which is equipped with a 3.4 GHz CPU and 32 GB random access memory (RAM) to ensure stable operation of the proposed algorithm. The sensor module, as illustrated in Figure 10, comprises two line-structured lasers with a wavelength: 405 nm (line widh < 180 μm, divergence angle 45°) to project structured light onto the wheel from both sides of the rail, two Basler acA1600-60gm cameras (Basler AG, Ahrensburg, Germany) with a resolution of 1600 px × 1200 px and an exposure time set to 1200 μs, and Computar M1614-MP2 fixed-focus lenses (CBC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with a 16 mm focal length.

Figure 10.

Structure of the sensor module in the wheel profile measurement system.

Manual measurements of the wheel’s flange height and flange thickness were conducted using a Model LLJ-4A tread profile measuring instrument (Jingyi Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) as a reference. This instrument is widely used in railway engineering, which has a division value of 0.10 mm and an inherent uncertainty of 0.03 mm. To reduce the impact of random errors on the reference value, 9 repeated measurements were performed for each wheel, and the mean value was taken as the reference value.

4.1. Standard Wheel Profile Measurement

First, a repeatability test of profile measurement was conducted using a standard wheel with uniform surface reflectivity. The proposed multiscale adaptive method and the conventional Steger method were applied, respectively. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measurement results of the standard wheel profile (unit: mm).

The proposed method yields slightly higher mean accuracy than the traditional Steger method with a fixed σ. Moreover, both the standard deviation (Std) and the maximum error (ME) of the proposed method are smaller than those of the Steger method, demonstrating higher stability.

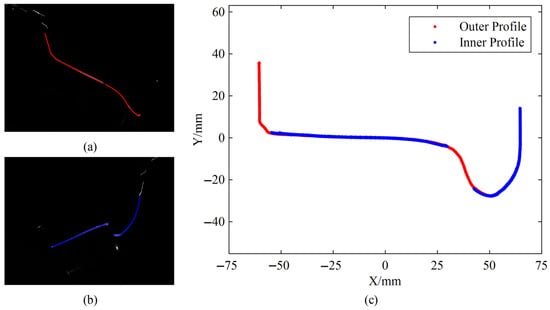

4.2. Real Train Wheelset Measurement

Field test data collected during actual train passes were analyzed. The train passed through the measurement system 9 times at a speed of 5 km/h. The coordinate transformation process for wheel profile measurement is illustrated in Figure 11. First, light stripe centers are extracted from the images captured by the inner and outer cameras, as shown in Figure 11a and b, respectively. Subsequently, the profile coordinates are reconstructed using calibrated parameters, including the camera extrinsic parameters and the light plane equation. The result of this coordinate transformation is displayed in Figure 11c. Finally, profile parameters are calculated based on the definitions.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of wheel profile coordinate transformation. (a) Outer stripe center coordinates; (b) Inner stripe center coordinates; (c) Transformed profile coordinates.

Accuracy tests are performed on the same train wheel image using the proposed method and the Steger method, respectively. First, the proposed method is applied to segment the stripe image. Subsequently, both methods are adopted to extract the stripe centers from the processed image. The results are presented in Table 2. For flange height, the mean value of the measurement results obtained by the proposed method is 27.72 mm with a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.12 mm and a Std value of 0.09 mm, thus exhibiting high precision and excellent reproducibility. In contrast, the mean measurement value of the conventional Steger method is 27.82 mm with an MAE of 0.22 mm and a Std of 0.16 mm, indicating a larger measurement deviation. For flange thickness, the proposed method achieves a mean measurement value of 32.5 mm, an MAE of 0.10 mm and a Std of 0.10 mm. However, the conventional Steger method yields a mean measurement value of 32.62 mm, an MAE of 0.22 mm and a Std of 0.22 mm. The consistent superior performance of the proposed method in both key parameters further verifies its excellent reproducibility and higher precision when processing actual complex light stripe images.

Table 2.

Measurement results of a real train wheelset. (unit: mm).

Additionally, the ME values between the flange height and flange thickness values measured by the proposed method and the manually measured reference values are 0.29 mm and 0.23 mm, respectively. These values meet the 0.4 mm accuracy requirement for dynamic wheel profile measurement in the railway industry. In contrast, the MEs of flange height and flange thickness measured by the conventional Steger method are 0.45 mm and 0.48 mm, respectively, exceeding the industry-specified accuracy threshold. This indicates that the multi-scale adaptive center extraction strategy adopted in the proposed method enhances reproducibility and stability.

To verify the reproducibility across different wheels, both the proposed method and the Steger method were used to test the images of 8 wheels. The flange height and flange thickness measurement results obtained via the two methods are presented in Table 3 and Table 4. The Std range of flange height measurements from the proposed method is 0.09–0.13 mm, while that from the conventional Steger method is 0.12–0.18 mm. For flange thickness, the Std range of the proposed method is 0.10–0.14 mm, in contrast to 0.22–0.26 mm for the conventional Steger method. It can be seen that for different wheels, the proposed method exhibits higher repeatability and reproducibility than the traditional Steger method with a fixed σ.

Table 3.

Reproducibility measurement results of flange height. (unit: mm).

Table 4.

Reproducibility measurement results of flange thickness (unit: mm).

This is attributed to the uneven wear of train wheels, which induces dynamic variations in both stripe width and gray-level distribution. The conventional method adopts a fixed σ and is sensitive to the width of the light stripe, which ultimately affects the accuracy and integrity of light stripe extraction, resulting in deviations in measurement results. In contrast, the proposed method employs a multi-scale adaptive strategy to match the optimal σ for the light stripe center, which improves the stability and accuracy of center extraction.

While the region-adaptive multiscale approach effectively improves the accuracy and stability of light stripe center extraction, and its effectiveness has been validated through tests, the computational cost increases due to the multiscale Hessian matrix calculations, as well as the additional steps for stripe feature enhancement and segmentation. Tests indicate that a combined procedure using median filtering, Otsu’s method, and connected-component analysis for image denoising and stripe segmentation takes approximately 0.3 s. The conventional Steger method requires about 0.7 s for center extraction alone, yet it fails to achieve accurate stripe segmentation and stable center localization. In comparison, the proposed method spends about 1.4 s on stripe enhancement and segmentation, and an additional 0.6 s for center extraction. Consequently, the total processing time is longer than that of the traditional Steger approach.

5. Conclusions

To address the issue of varying light stripe widths and non-uniform gray-level distribution caused by uneven surface reflectivity in the online measurement of train wheel profiles, this paper proposes a region-adaptive multiscale method for light stripe center extraction. The core of this method lies in its multiscale adaptive mechanism, which essentially functions as a scale-matching strategy between the Gaussian kernel parameter σ and the stripe width w. By leveraging multiscale analysis to adaptively select the optimal σ for stripes with varying widths, this mechanism achieves a balance between noise suppression and feature preservation while enhancing the accuracy of stripe center extraction. Specifically, based on the morphological characteristics of the stripe, the method first enhances stripe features to achieve accurate segmentation. By normalizing the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix, it adaptively determines the optimal scale parameter (σ) that best matches the local stripe width, thereby effectively improving the accuracy and stability of center extraction. This key multiscale adaptive capability allows the method to select the optimal scale for stripe regions of varying widths, effectively resolving the limitation of traditional fixed-kernel approaches that fail to adapt to complex stripe variations and enabling precise identification of the stripe centerline. To validate the method, centerline extraction experiments were conducted on complex stripe images acquired by a line-structured light vision sensing system for wheelset profile measurement, installed at the National Railway Test Center of the China Academy of Railway Sciences. Experimental results demonstrate that for wheels with uniform reflective surfaces, the measurement accuracy of the proposed method is marginally higher than that of the conventional Steger method. Under complex working conditions involving non-uniform wheel surface reflectivity, the proposed method achieves a measurement Std of less than 0.1 mm, a measurement bias of 0.12 mm, and a maximum measurement error below 0.3 mm, exhibiting superior repeatability and accuracy compared to the Steger method with a fixed σ parameter. Reproducibility tests were conducted on the light strip images of different wheels using the proposed method and Steger, respectively. The results showed that the proposed approach enables stable and reliable extraction of the light stripe center, thereby enhancing both stability and accuracy in industrial measurement environments. This research addresses the difficulty of extracting stripe centers from images affected by uneven surface roughness, a key challenge in laser vision sensing for wheelset profile measurement. Leveraging the intrinsic advantages of multiscale feature information, this multiscale adaptive approach achieves stable and accurate extraction of stripe center coordinates under complex operating conditions, providing not only an effective technical solution for high-accuracy wheelset profile measurement but also a valuable reference for similar image processing tasks in laser-based sensing. Additionally, it lays a theoretical foundation for engineering applications of such multiscale adaptive strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, S.L. and Q.H.; software, S.L. and W.F.; validation, S.L.; investigation and data curation, S.L. and B.D.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, Q.H. and Q.F.; supervision, Q.F.; funding acquisition, Q.H. and Q.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51935002).

Data Availability Statement

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baek, K.; Shin, S.; Kim, M.; Oh, J.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, M.D.; So, H. Rapid and precise geometric measurement of injection-molded axial fans using convolutional neural network regression. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 2500364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Gao, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Wu, K. A machine vision-based dimension measurement method of shaft parts with sub-pixel edge. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 055026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profili, A.; Magherini, R.; Servi, M.; Spezia, F.; Gemmiti, D.; Volpe, Y. Machine vision system for automatic defect detection of ultrasound probes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 135, 3421–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, M.Z.; Ahmed, Z.; Chowdhry, B.S.; Baro, E.N.; Hussain, T.; Uqaili, M.A. State-of-the-art wayside condition monitoring systems for railway wheels: A comprehensive review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 13257–13279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunfu, G.; Siyuan, B.; Chongqiu, Z.; Xinsheng, H.; Shiju, E.; Jianfeng, S.; Jijun, G. Research on the line point cloud processing method for railway wheel profile with a laser profile sensor. Measurement 2023, 211, 112640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Niu, G.; Zuo, M. Offline and online measurement of the geometries of train wheelsets: A review. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3523915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yu, T.; Liang, D.; He, Z. A review on 3D measurement of highly reflective objects using structured light projection. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 4205–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Du, H.; Yin, P.; Zhang, Y. Measurement of gear tooth profiles using incoherent line structured light. Measurement 2022, 189, 110450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Kang, W.; Lu, Z. Improved structured light centerline extraction algorithm based on unilateral tracing. Photonics 2024, 11, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Rong, W. Efficient sub-pixel laser centerline extraction via an improved U-Net for structured light measurement. Measurement 2026, 257, 118807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, G.; Liu, G.; Song, Z.; Feng, F.; Liu, B.; Wu, Y. Robust centerline extraction method of laser stripe based on an underwater line scanning lidar. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 188, 108898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, W.; Gao, P.; Xing, H.; Ma, J. Extraction method of a nonuniform auxiliary laser stripe feature for three-dimensional reconstruction of large components. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 6573–6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Kang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, S.; Tan, J. Robust laser stripe extraction for 3D measurement of complex objects. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 065002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, R.; Wang, K. Two-dimensional laser feature extraction based on improved successive edge following. Appl. Opt. 2015, 54, 4273–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Yang, K.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X.; Jiang, T.; Li, C. Laser curve extraction of wheelset based on deep learning skeleton extraction network. Sensors 2022, 22, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wang, W.; Chu, Y. A simple and stable centeredness measure for 3D curve skeleton extraction. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2022, 28, 1486–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J. Laser stripe center detection under the condition of uneven scattering metal surface for geometric measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 2182–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Jing, H.; Guo, A.; Chen, Y.; Song, D. Accurate laser centerline extraction algorithm used for 3D reconstruction of brake caliper surface. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 167, 109743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhao, Y. Edge detection of high-resolution remote sensing image based on multi-directional improved sobel operator. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 135979–135993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yu, D.; Shi, H. Laser stripe extraction for 3D reconstruction of complex internal surfaces. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 5562–5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Huang, J.; Wang, Z.; Duan, Q.; Li, Z.; Gao, J.; Li, Q. Research on the analysis and removal of noise point from fringe center extraction in coded structured light 3D measurement. Measurement 2026, 257, 118923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Deng, X.; Liu, G.; Chen, W. Parallelization strategy of laser stripe center extraction for structured light measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 9524811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, L.; Wan, Y.; Yang, K.; Luo, L. An adaptive weighted width extraction method based on the hessian matrix for high-precision detection of laser stripe centers in low-exposure. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2024, 181, 108436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, F. A high-precision and noise-robust subpixel center extraction method of laser stripe based on multi-scale anisotropic Gaussian kernel. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2024, 176, 108060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Yu, D.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Z. Laser stripe centerline extraction method for deep-hole inner surfaces based on line-structured light vision sensing. Sensors 2025, 25, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Q.; Hou, B.; Miao, Z.; Liu, H.; Lu, X.; Wang, Y. Laser stripe center extraction method base on Hessian matrix improved by stripe width precise calculation. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2024, 172, 107896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Xie, Z. Laser stripe centre extraction method for fuel assembly deformation measurement. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 188, 108893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; He, J.; Li, Y. Center extraction method for reflected metallic surface fringes based on line structured light. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 2024, 41, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Diao, K.; Luo, C. An enhanced centerline extraction algorithm for complex stripes in linear laser scanning measurement. Precis. Eng.-J. Int. Soc. Precis. Eng. Nanotechnol. 2024, 91, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, L.; Long, X.; Chen, Y.; Deng, H.; Yan, F. Hardware-oriented algorithm for high-speed laser centerline extraction based on hessian matrix. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Gu, A.Q.; Zhang, Z.J. Multi-line laser stripe centerline extraction methods for reflective metal surfaces using deep learning and Hessian matrix. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 065403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Fu, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C. Extraction of laser stripe centerlines from translucent optical components using a multi-scale attention deep neural network. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 085404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wu, S.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F. A robust and accurate centerline extraction method of multiple laser stripe for complex 3D measurement. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 58, 102207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, G. Reliable and accurate wheel size measurement under highly reflective conditions. Sensors 2018, 18, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Wang, Y. Three-dimensional measurement of precise shaft parts based on line structured light and deep learning. Measurement 2022, 191, 110837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.-Y.; Chiang, P.-J. Improved structured light system based on generative adversarial networks for highly-reflective surface measurement. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 171, 107783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Zhao, B.; Wang, W.; Xu, X.; Luo, M. Metal surface 3D imaging based on convolutional autoencoder and light plane calibration. Optik 2022, 259, 169007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, C. Unbiased extraction of lines with parabolic and Gaussian profiles. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2013, 117, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, C. An Unbiased Detector of Curvilinear Structures. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1998, 20, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Xie, F. Statistical behavior analysis and precision optimization for the laser stripe center detector based on Steger’s algorithm. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 13442–13449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, K.; Yang, G.; Liu, X.; Du, R.; Li, Y. Real-time uncertainty estimation of stripe center extraction results using adaptive BP neural network. Measurement 2022, 194, 111022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, A.; Morscher, S.; Najafababdi, J.M.; Jüstel, D.; Zakian, C.; Ntziachristos, V. Assessment of hessian-based Frangi vesselness filter in optoacoustic imaging. Photoacoustics 2020, 20, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, G. Image Local Invariant Features and Descriptors; Nation Defense Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.