Abstract

Octachlorinated metal phthalocyanines (MPcCl8, M = Co, Zn, VO) represent an underexplored class of functional materials with promising potential for chemiresistive sensing applications. This work is the first to determine the structure of single crystals of CoPcCl8, revealing a triclinic (P-1) packing motif with cofacial molecular stacks and an interplanar distance of 3.381 Å. Powder XRD, vibrational spectroscopy, and elemental analysis confirm phase purity and isostructurality between CoPcCl8 and ZnPcCl8, while VOPcCl8 adopts a tetragonal arrangement similar to its tetrachlorinated analogue. Thin films were fabricated via physical vapor deposition (PVD) and spin-coating (SC), with SC yielding highly crystalline films and PVD resulting in poorly crystalline or amorphous layers. Electrical measurements demonstrate that SC films exhibit n-type semiconducting behavior with conductivities 2–3 orders of magnitude higher than PVD films. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations corroborate the experimental findings, predicting band gaps of 1.19 eV (Co), 1.11 eV (Zn), and 0.78 eV (VO), with Fermi levels positioned near the conduction band, which is consistent with n-type character. Chemiresistive sensing tests reveal that SC-deposited MPcCl8 films respond reversibly and selectively to ammonia (NH3) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) at room temperature. ZnPcCl8 shows the highest NH3 response (45.3% to 10 ppm), while CoPcCl8 exhibits superior sensitivity to H2S (LOD = 0.3 ppm). These results suggest that the films of octachlorinated phthalocyanines produced by the SC method are highly sensitive materials for gas sensors designed to detect toxic and corrosive gases.

1. Introduction

Halogenated phthalocyanine-based materials have shown great potential for use in a variety of applications, including organic field-effect transistors, sensors, and biologically related applications [1,2,3]. The development of new materials based on MPcHalx is always a focus, as it allows for further improvement of the performance characteristics and expansion of the application areas of these materials. Their inherent chemical and thermal stability, combined with tunable electronic properties, also makes them valuable building blocks for covalent organic frameworks [4,5,6,7].

Halogenation is known to enhance oxidative stability by shifting oxidation potentials to the anodic region [8] and significantly improves sensitivity toward reducing gases such as ammonia and hydrogen sulfide [2,9]. In recent years, fluoro-substituted metal phthalocyanines (MPcFx, x = 4, 8, 16) have attracted considerable research interest, with numerous studies reporting on their structural [10,11], thermal [12,13], optical [14], and electrical properties [15], as well as their application in thin-film electronic devices [16]. In contrast, investigations into chloro-substituted MPcClx have largely focused on synthetic methodologies and optical characteristics, while systematic studies of their crystal structures and thin-film morphology, particularly in technologically relevant thickness ranges, remain comparatively scarce. This disparity is partly attributable to the historical use of chlorinated phthalocyanines as green organic pigments in industrial applications [17,18,19].

Nevertheless, chlorinated MPcs exhibit promising functional properties beyond pigmentation. For instance, chlorinated bis(phthalocyaninates) of rare-earth metals display strong absorption in the 680–700 nm range within the so-called “therapeutic window” for photodynamic therapy and demonstrate enhanced superoxide anion generation compared to their non-halogenated analogues [20,21]. Moreover, certain mixed halogen derivatives, such as MCl2PcF16, MCl2PcCl16, and MF2PcCl16 (M = Sn, Ge), have been shown to possess optical limiting capabilities [22]. Nonlinear optical behavior has also been reported for lanthanide-based octachlorinated phthalocyanines [23].

Research on thin films of chlorinated phthalocyanine has primarily addressed ultrathin layers (typically <5 nm), emphasizing interfacial interactions with substrates and surface phenomena [24,25,26]. However, there is a notable gap in understanding the structural and morphological characteristics of thicker films (50–200 nm), despite their widespread use as active layers in organic field-effect transistors (OFETs) and chemiresistive sensors. Notably, tetrachloro-substituted ZnPcCl4 has demonstrated superior sensitivity toward ammonia compared to both unsubstituted and fluorinated analogues, highlighting the potential of chlorinated MPcs in chemical sensing [2].

Our previous work has contributed to this field through structural investigations of single crystals and thin films of tetrachloro-substituted phthalocyanines with Cl-substituents in peripheral (MPcCl4-p, M = Zn, VO) and non-peripheral (MPcCl4-np, M = Zn, VO) [2,27]. Additionally, VOPcCl16 films have been evaluated as active components in OFET architectures [28]. At the same time, structure and properties of octachloro-substituted phthalocyanines have not been extensively studied, even though synthetic protocols for Cu(II), Co(II), Ni(II), and Zn(II) octachlorophthalocyanines have been well established [29]. To date, only the Lyubovskaya group has reported a structure of crystalline anionic salt of an octachlorinated derivative: {cryptand(Na+)}2[SnIVCl2(TPyzPzCl84−)]2−·2C6H4Cl2 (triclinic, P1−) [30].

Conductivity studies of chloro substituted cobalt phthalocyanines were provided by Achar and co-workers [31]. It was found that CoPcCl8 exhibits a linear variation in electrical conductivity in the temperature range 30–200 °C. The room temperature electrical conductivities observed for CoPcCl4, CoPcCl8 and CoPcCl16 are 104, 102 and 106 times higher than CoPc complex (CoPcCl16 ˃ CoPcCl4 ˃ CoPcCl8 ˃ CoPc). The sensor properties of octachloro-substituted metal phthalocyanines have also been practically unstudied. Bouvet and his group of researchers prepared bilayer configuration organic heterojunctions based on octachlorinated metallophthalocyanines (MPcCl8; M = Co, Cu and Zn) as a sublayer and lutetium bis-phthalocyanine (LuPc2) as a top layer [32]. While the metal has little effect on baseline device performance, it dictates the NH3 sensing mechanism: CoPcCl8 enables n-type response to NH3, CuPcCl8 shows p-type response, ZnPcCl8 exhibits ambipolar behavior. In our recent work we investigated the effect of the central metal ion on crystal features and conductivity for MPcF8 (M = Co, Zn, VO) [33]. The lateral DC conductivity of ZnPcF8 and VOPcF8 films was similar, whereas the conductivity of CoPcF8 films was significantly higher.

Thus, an analysis of the literature has shown that films of octachloro-substituted phthalocyanines and especially structure-property-sensor performance correlation are insufficiently studied in comparison with fluoro-substituted analogues. Their crystallographic structure, film morphology, and chemiresistive properties remain virtually unexplored, despite expectations that eight chlorine atoms strongly withdrawing electrons can cause profound changes in the electronic structure and intermolecular interactions compared with tetrachlorinated or fluorinated analogues. Unlike MPcF8 derivatives, where the high electronegativity and small size of fluorine favor planar, densely packed structures, the larger van der Waals radius and polarizability of chlorine in MPcCl8 can contribute to a different type of packing and, as a result, charge transfer. Moreover, the combined inductive effect of the eight chlorines is expected to significantly stabilize the boundary orbitals, potentially narrowing the band gap and shifting the Fermi level towards the conduction band, thereby providing n-type semiconductor properties that are rare among conventional phthalocyanines.

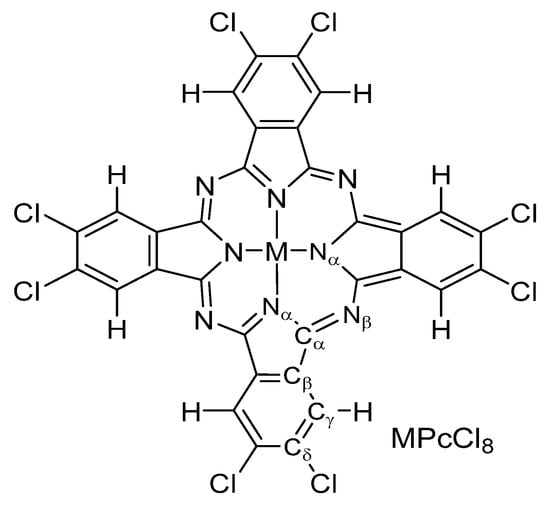

In the present study, we address these critical gaps by reporting the synthesis of octachloro-substituted metal phthalocyanines MPcCl8 (M = Co, Zn, VO; Figure 1) and, for the first time, the single-crystal X-ray structure of CoPcCl8. All compounds were thoroughly characterized by elemental analysis, vibrational spectroscopy (IR and Raman), electronic absorption spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction to confirm chemical composition and purity. Thin films were fabricated via both vacuum thermal evaporation and spin-coating techniques. The physicochemical properties of the bulk materials and their corresponding thin films were systematically investigated. Finally, the sensing performance of these films was evaluated as active layers in chemiresistive sensors for the detection of ammonia (NH3) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

Figure 1.

Structure of MPcCl8 (M = Co, Zn, VO).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Octachloro-Substituted Metal Phthalocyanines

MPcCl8 (M = Co, Zn, VO) were synthesized via a solution-based cyclotetramerization method. In a typical procedure, 4,5-dichlorophthalonitrile (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, CAS 139152-08-2, ≥99%) and the corresponding metal chloride (CoCl2, ZnCl2, or VOCl3 Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were refluxed in 1-chloronaphthalene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, CAS 90-13-1, ≥85 %) under constant stirring for 2 h. The crude products were purified using a Soxhlet extractor with sequential extraction in diethyl ether, acetone, and ethanol (24 h) (solvents were purchased from AO REAKHIM, Moscow, Russia) to remove unreacted precursors and by-products. The resulting complex was then heated under vacuum (10−5 Torr) at 300 °C. Final yields ranged from 55% to 70%. All compounds were characterized by elemental analysis, vibrational spectroscopy (IR and Raman), and X-ray diffraction to confirm chemical composition and purity. Elemental analysis results:

CoPcCl8 yield 71.3%. Elemental Anal. Calcd. for C32H8N8Cl8Co: C, 45.4; N, 13.2; H, 1.0. Found: C, 45.5; N, 12.9; H, 1.3.

ZnPcCl8 yield 69.5%. Elemental Anal. Calcd. for C32H8N8Cl8Zn: C, 45.0; N, 13.1; H, 1.0. Found: C, 45.1; N, 13.3; H, 1.3.

VOPcCl8 yield 54.7%. Elemental Anal. Calcd. for C32H8N8Cl8VO: C, 43.9; N, 12.8; H, 1.0. Found: C, 44.0; N, 12.4; H, 1.2.

Elemental analyses (C, H, N) were performed using a Thermo Finnigan Flash 1112 analyzer (Thermo Finnigan Italia S.p.A. Milan, Italy). IR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Vertex 80 FT-IR spectrometer (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) in transmission mode (KBr pellets).

2.2. Thin Film Fabrication

Thin films of MPcCl8 were prepared using two complementary techniques: spin-coating (SC) and physical vapor deposition (PVD). Films were deposited onto glass substrates (Deltalab, Barcelona, Spain, 18 × 18 mm) and glass substrates with interdigitated Pt electrodes (Metrohm DropSens, Oviedo, Asturias, Spain). Prior to deposition, the substrates were cleaned sequentially with sulfuric acid, distilled water and acetone, then boiled in isopropanol for 20 min, and finally dried at ambient temperature.

Spin-coating: A solution of 3.0 mg of MPcCl8 in 400 µL of tetrahydrofuran (THF, AO REAKHIM, Moscow, Russia) was deposited dropwise onto cleaned substrates using a microdispenser (Thermo Scientific, Saint-Petersburg, Russia). Films were formed by spinning at 2000 rpm for 60 s using an Elmi CM-6M centrifuge (SIA «ELMI», Riga, Latvia).

Physical vapor deposition: Films were thermally evaporated under high vacuum (10−5 Torr) using a VUP-5M deposition system. The MPcCl8 powders were evaporated at 450 °C for 2 h, resulting in uniform films with nominal thicknesses of about 50–80 nm.

2.3. Structural and Morphological Characterization

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) of CoPcCl8 was performed on a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer (Billerica, MA, USA) (equipped with an Incoatec IµS 3.0 microfocus CuKα X-ray source (λ = 1.54178 Å) and a PHOTON III CPAD detector mounted on a three-circle kappa goniometer. A needle-shaped crystal (70 × 5 µm) was selected from the as-synthesized product. Data collection strategy consisted of several standard ω-scans with 0.5° wide frames. Temperature of single crystal sample was kept at 150 K during the experiment by an Oxford Cryosystems Cryostream 800 plus open-flow nitrogen cooler (Oxford Cryosystems, Oxford, UK). Data processing, including unit cell determination, integration, and multi-scan absorption correction, was performed using APEX3 v.2019.1-0 software package (Madison, WI, USA) [34]. Obtained hklF dataset was processed in Olex2 v.1.5 [35], with SHELXT v.2018/2 [36] and SHELXL v.2018/3 [37] used for structure solution and refinement, respectively. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically, but ISOR restraints had to be placed on all carbon and nitrogen atoms due to the poor quality of the diffraction data. Hydrogen atoms were placed in idealized positions and refined using the “riding” model. Final CIF was deposited to the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under No. 2503921 and can be downloaded for free at www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures (accessed on 18 November 2025).

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns of polycrystalline samples and thin films were collected on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Billerica, MA, USA) (CuKα radiation, λ = 1.5406 Å) equipped with a LynxEye XE-T silicon strip detector. Powder samples were gently ground in an agate mortar with a minimal amount of ethanol and spread as a thin layer on flat surface of a standard sample holder. Diffraction data were recorded over a 2θ range of 3–40° with a step size of 0.02°.

The topology of MPcCl8 films was studied in the semi-contact mode using the NTEGRA Prima II atomic force microscope (NT-MDT, Moscow, Russia). The MFM-01 probe was used with the following parameters: probe length—225 μm, width—28 mm, thickness—3 μm, force constant—1–5 N/m, and resonant frequency—47–90 kHz.

2.4. Quantum-Chemical Calculations

Quantum-chemical computations of the band structure for MPcCl8 crystals (where M = Co, Zn, and VO) were carried out using the OpenMX package (version 3.9) based on density functional theory (DFT) [38], with the PBE functional employed for the exchange-correlation energy [39]. The calculations utilized norm-conserving pseudopotentials [40,41,42,43,44,45] and an optimized pseudo-atomic orbital basis set labeled as “standard” in OpenMX [46,47]. Due to the closed-shell configuration of zinc, spin-unpolarized calculations were performed for ZnPcCl8. In contrast, spin-polarized DFT+U calculations were applied to CoPcCl8 and VOPcCl8, following Dudarev’s approach [48,49]. A Hubbard U parameter of 5 eV was selected, consistent with values previously established in the literature for analogous phthalocyanine systems. In particular, comprehensive studies on Co-phthalocyanine (CoPc) have demonstrated that the Ueff value in the range of 4–6 eV provides optimal agreement with experimental valence-band photoelectron spectroscopy data and hybrid functional (e.g., B3LYP, HSE06) results for the position and ordering of Co 3d states, as well as structural and magnetic properties [50,51,52]. A value of Ueff = 6 eV was explicitly shown to best reproduce both the experimental bond lengths and the Co 3d spectral features in CoPc [50], while a systematic comparison across transition-metal phthalocyanines confirmed that the appropriate Ueff was system-dependent and typically falls within 4–6 eV for Co-containing systems [51]. Similarly, for vanadyl phthalocyanines, U ≈ 5 eV has been successfully used to capture the correct electronic structure and magnetic behavior [53]. Given the strong structural and electronic similarity between unsubstituted CoPc/VOPc and their octachlorinated derivatives, the choice of U = 5 eV (within ±1 eV of the values validated in prior work) is well-justified for reliably describing the correlated 3d electrons in CoPcCl8 and VOPcCl8. Additionally, dispersion effects were accounted for using the DFT-D3 correction [54,55]. Structural relaxation was performed until the residual forces on atoms fell below 3 × 10−4 a.u.

Furthermore, electrical transport properties were derived from the computed band structures. Special attention was given to the variation in the Seebeck coefficient with chemical potential. These estimates were made within the Boltzmann transport formalism [56] using the BoltzTraP code (version 1.2.5) [57].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of CoPcCl8, ZnPcCl8, and VOPcCl8

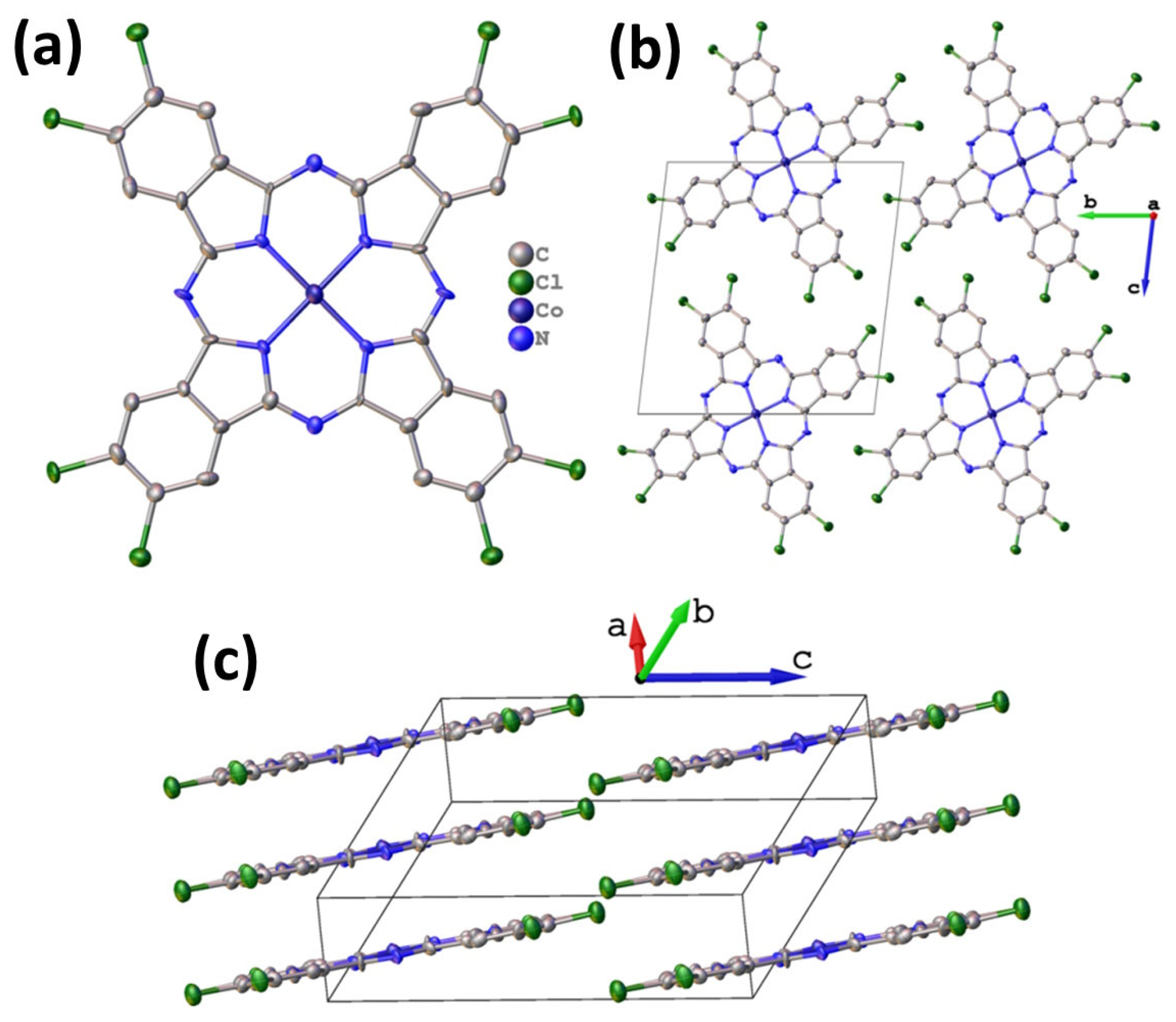

3.1.1. Crystal Structure of CoPcCl8

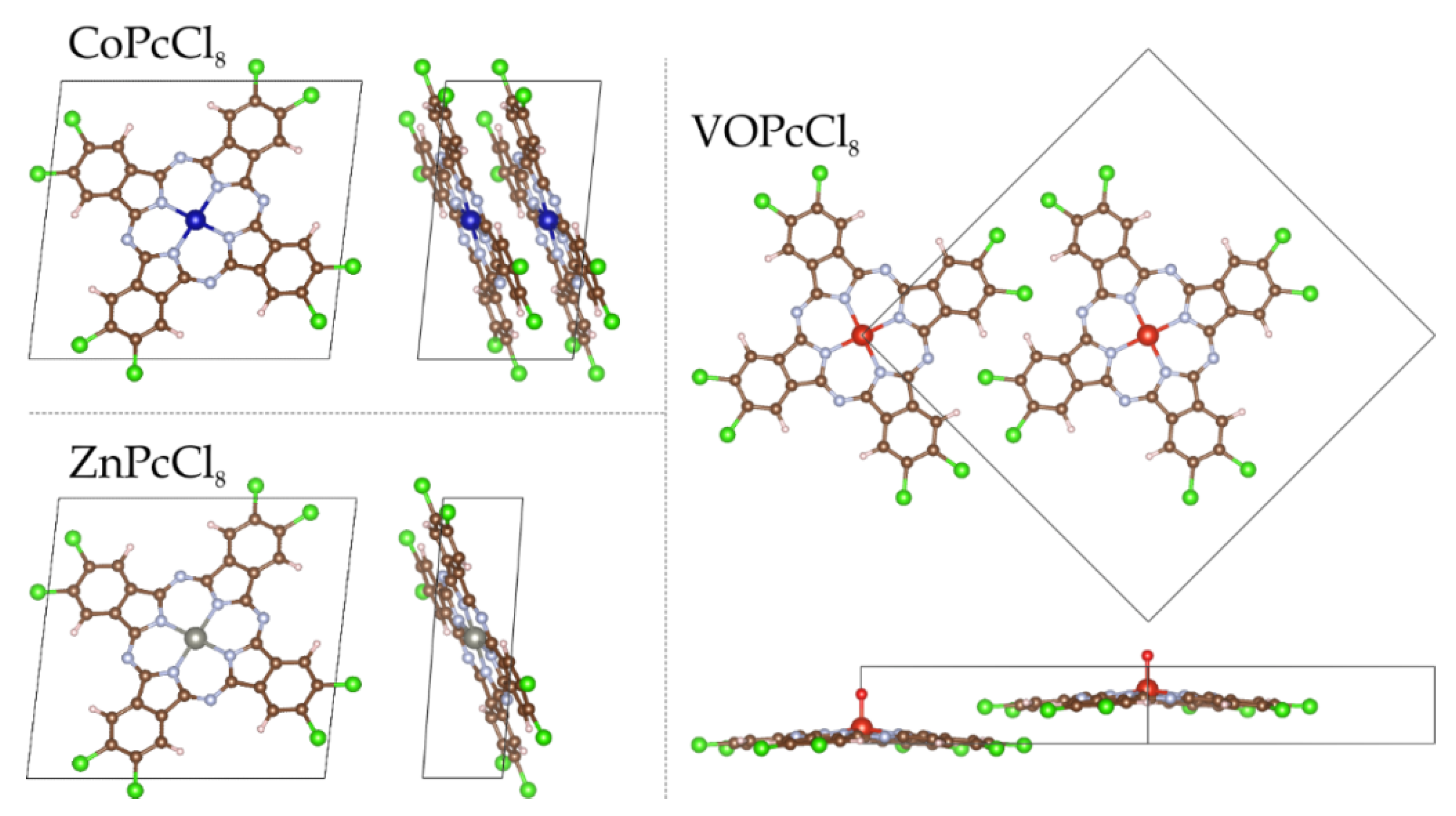

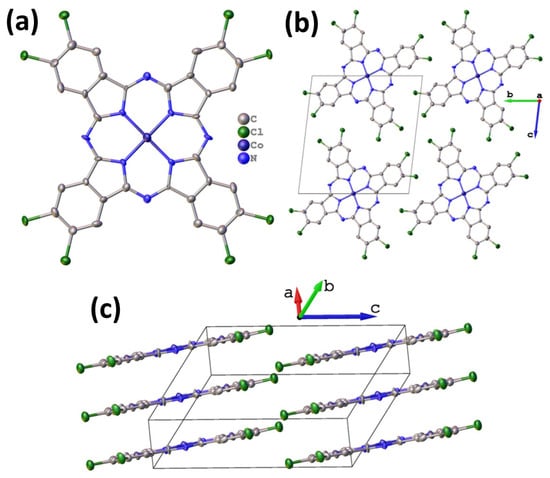

Octachlorinated metal phthalocyanines exhibit significantly lower volatility compared to their fluoro-substituted analogues. Consequently, obtaining high-quality single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis is exceptionally challenging. Nevertheless, a small needle-shaped crystal of CoPcCl8 was fortuitously identified in the crude synthesis product, enabling the first single-crystal structure determination of an octachloro-substituted cobalt phthalocyanine. Despite the modest quality of the diffraction data attributable to the crystal’s small size and potential disorder the inherent rigidity of the phthalocyanine macrocycle allowed for a chemically reasonable structural model to be refined without imposing geometric restraints. Unit cell parameters and refinement details are summarized in Table 1. CoPcCl8 crystallizes in the P-1 space group with Z = 1. The structure is isostructural with its fluoro-substituted analogue CoPcF8 [33], confirming that halogen substitution at the peripheral positions does not alter the fundamental packing motif in this series. The molecules are packed in uniform stacks along the a axis (Figure 2) with an interplanar distance of 3.381 Å between adjacent macrocycles and a packing angle (defined as an angle between the packing direction and the normal to the molecule plane) of 24.18°.

Table 1.

Unit cell parameters and refinement details for CoPcCl8.

Figure 2.

Molecular structure (a) and packing diagrams (b,c) for CoPcCl8.

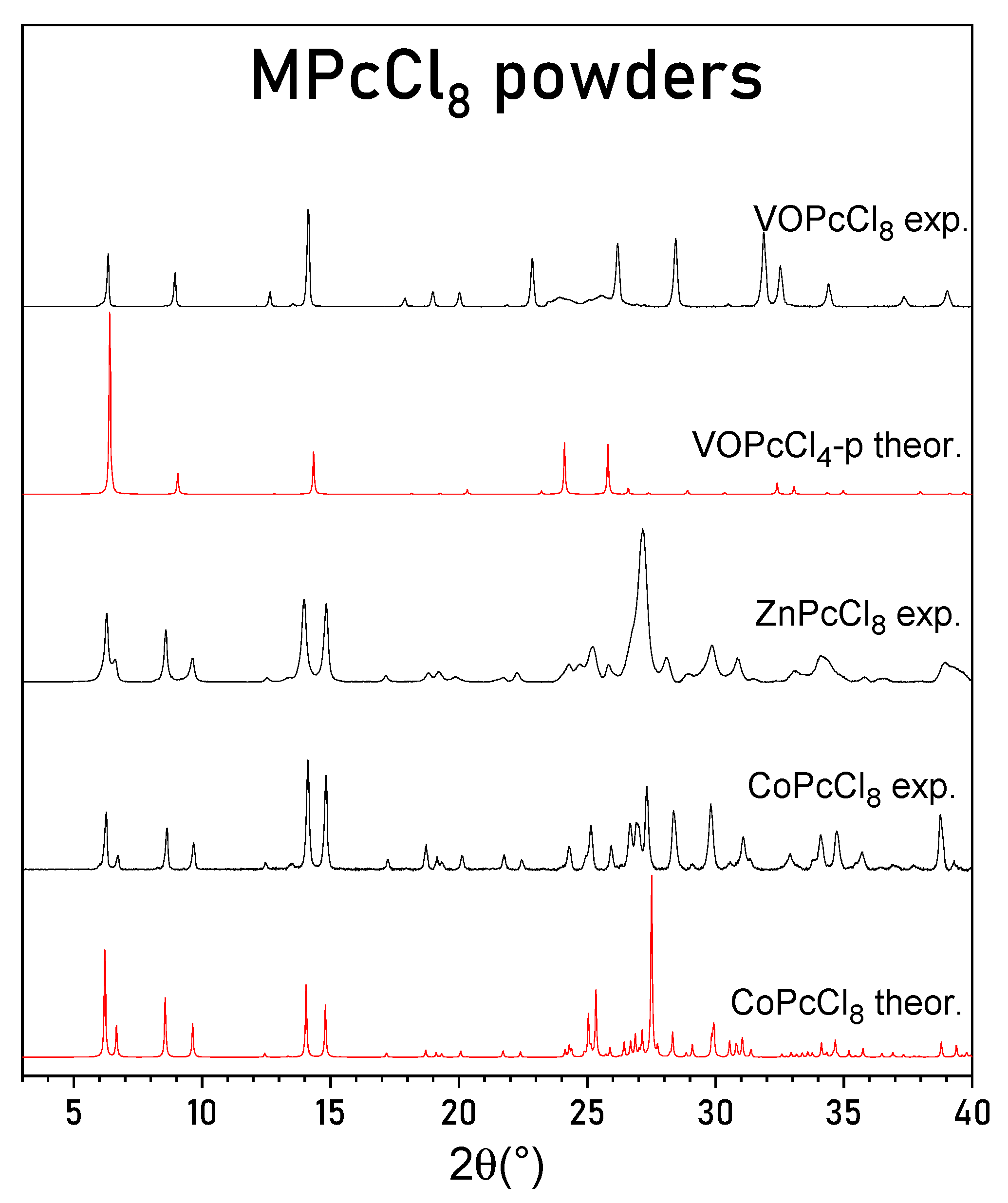

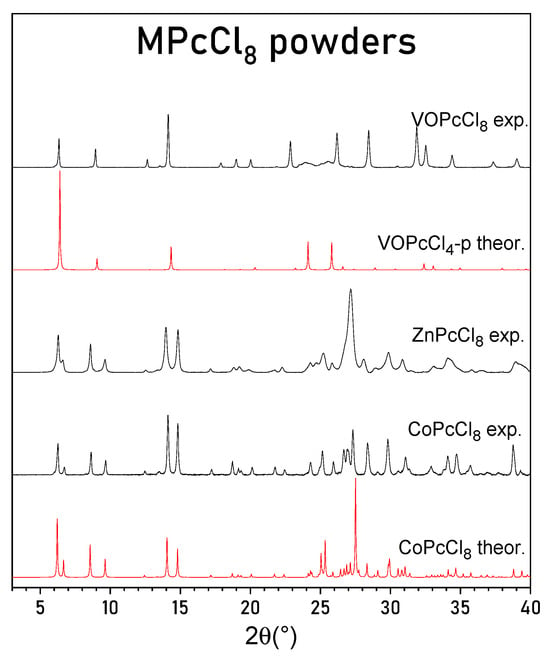

3.1.2. Powder XRD Analysis of CoPcCl8, ZnPcCl8, and VOPcCl8

PXRD patterns of CoPcCl8, ZnPcCl8, and VOPcCl8 are presented in Figure 3, in comparison with theoretical patterns calculated from the single-crystal structure of CoPcCl8 and from the known structure of VOPcCl4-p [27]. The experimental PXRD pattern of CoPcCl8 shows good agreement with the pattern simulated from its single-crystal structure. No extraneous diffraction peaks are observed, confirming that the polycrystalline sample consists of a single crystalline phase without detectable impurities.

Figure 3.

Experimental powder diffraction patterns for CoPcCl8, ZnPcCl8 and VOPcCl8 and calculated diffraction patterns for CoPcCl8 and VOPcCl4-p.

Although the crude product of ZnPcCl8 exhibited a similar morphology—dark violet, needle-like crystals with a metallic luster—the crystals were substantially smaller, precluding even unit cell determination by single-crystal methods. Nevertheless, the PXRD pattern of ZnPcCl8 closely resembles that of CoPcCl8, indicating that these compounds are isostructural. Leveraging the CoPcCl8 structural model, we successfully indexed the diffraction peaks of ZnPcCl8 and refined its unit cell parameters, which are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Unit cell parameters for ZnPcCl8 and VOPcCl8.

The PXRD pattern of VOPcCl8 closely matches the calculated pattern for tetragonal VOPcCl4-p, indicating that VOPcCl8 also adopts a tetragonal unit cell with molecules arranged in stacks along the c axis. It is worth noting that the peaks on the VOPcCl8 diffraction pattern are not uniform. Two peaks in the 23–26° 2θ region are significantly broader than the others. These two peaks correspond to the (011) and (121) crystallographic planes and are the only peaks with an l index not equal to zero observed on the diffraction pattern. Their broadening suggests the presence of stacking faults or orientational disorder along the c-axis. A similar phenomenon has been reported for VOPcCl4-p, where vanadyl phthalocyanine molecules stack in a head-to-tail fashion with random “up”/“down” orientations, leading to diffuse scattering and a highly disordered structural model. Using the VOPcCl4-p crystal structure data, we indexed the VOPcCl8 diffraction pattern and refined its tetragonal unit cell parameters (Table 2).

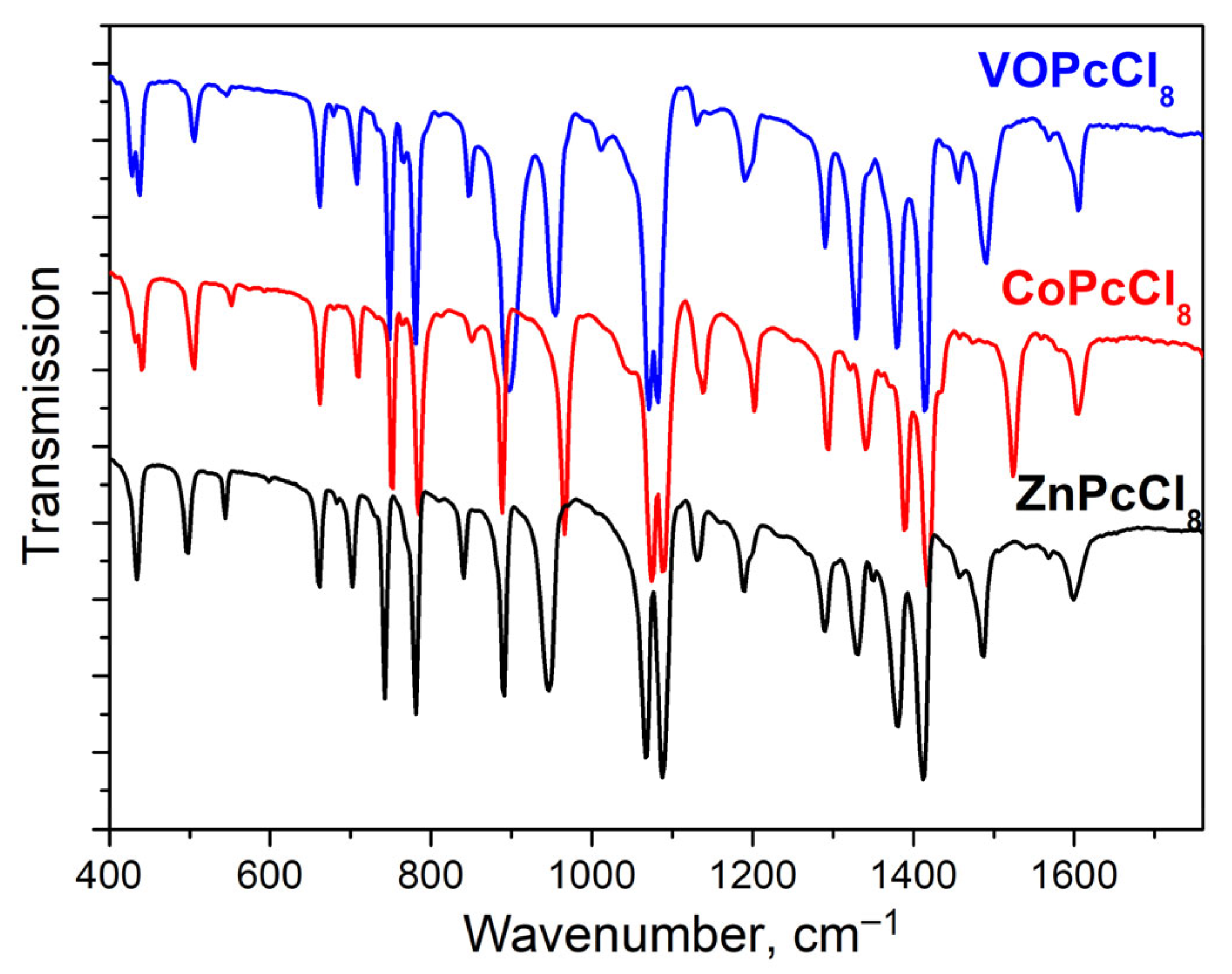

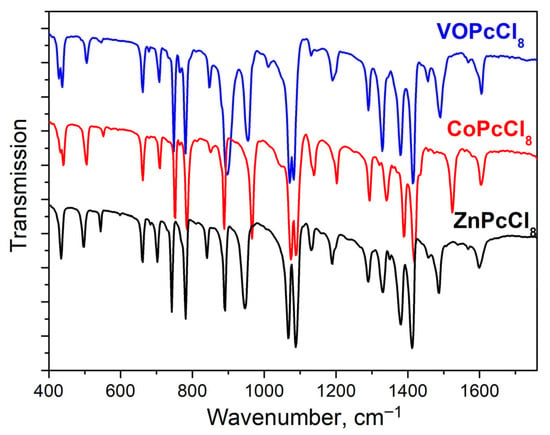

3.1.3. IR Spectra of MPcCl8

IR spectra of MPcCl8 were also studied (Figure 4). Band assignments supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations are summarized in Table 3. Most vibrational modes originate from the phthalocyanine macrocycle and show minimal frequency shifts across the series (M = Co, Zn, VO). However, several key bands exhibit metal-dependent frequency variations. Like MPc and MPcFx derivatives [58], the bands sensitive to the central metal are located in the spectral range from 1350 to 1550 cm−1, as they are associated with vibrations of atoms forming the inner cavity of the macrocycle. Apart from this, V = O vibrations is observed at 1012 cm−1.

Figure 4.

MPcCl8 IR-spectra in KBr pellets.

Table 3.

Assignments of the most intense bands in IR spectra of MPcCl8.

3.2. Structural and Functional Characterization of CoPcCl8, ZnPcCl8, and VOPcCl8 Thin Films

Thin films of MPcCl8 (M = Co, Zn, or VO) were prepared using two distinct deposition techniques: physical vapor deposition (PVD) and solution-based spin-coating (SC) from dichloromethane. The structural properties of these films were investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD), and their morphological and sensing characteristics were further analyzed using atomic force microscopy (AFM) and chemiresistive measurements.

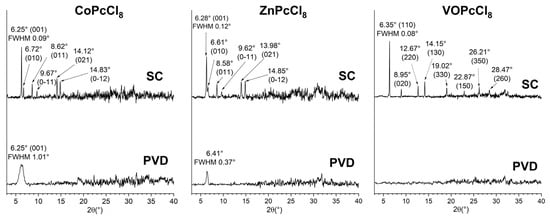

3.2.1. Structural Properties

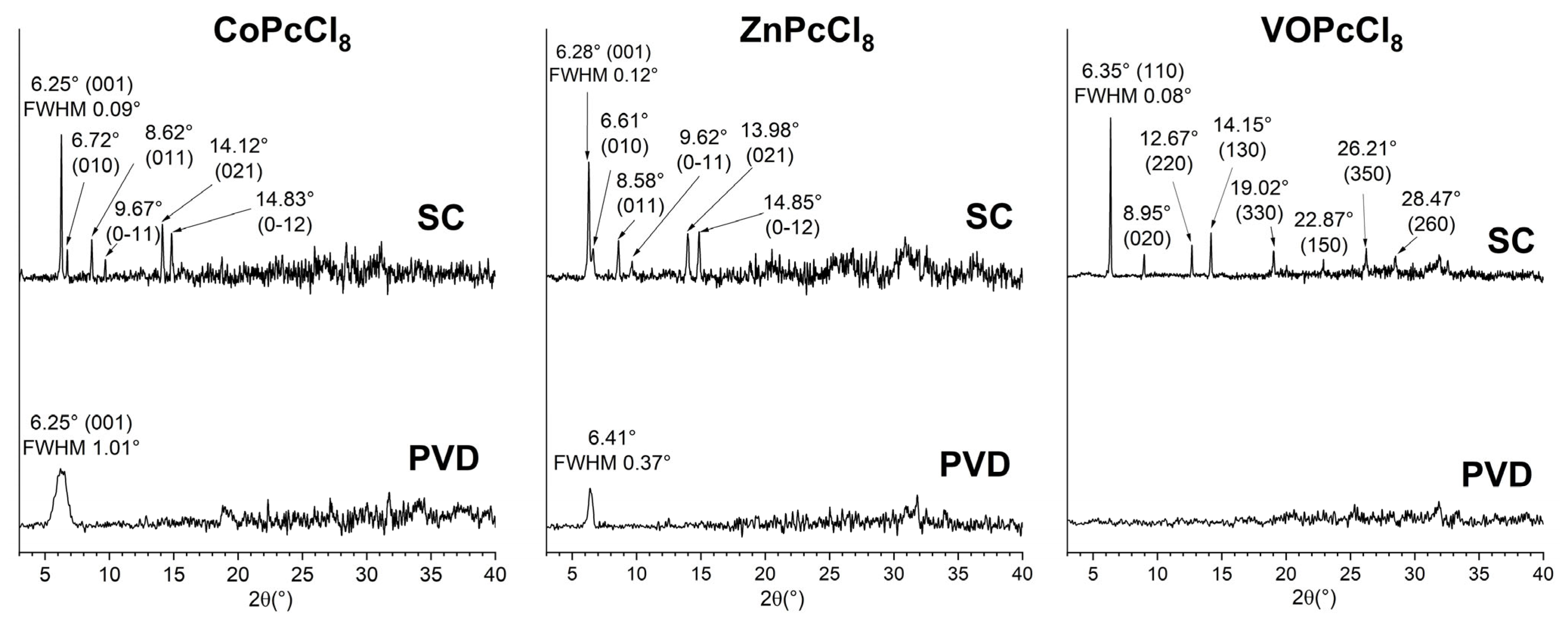

XRD patterns of PVD-deposited CoPcCl8 and ZnPcCl8 exhibit a single broad diffraction peak, indicative of strong molecular orientation but poor crystallinity (Figure 5). In contrast, the PVD film of VOPcCl8 shows no discernible Bragg peaks, suggesting an amorphous structure. The peak position for CoPcCl8 (2θ = 6.25°) aligns closely with the (001) reflection calculated from single-crystal data, confirming that the PVD film retains the same crystalline phase as the bulk polycrystalline powder. Moreover, this alignment allows estimation of the molecular tilt angle relative to the substrate: CoPcCl8 molecules are oriented at approximately 76.8° with respect to the surface plane.

Figure 5.

XRD patterns for PVD and SC of CoPcCl8, ZnPcCl8 and VOPcCl8 films.

In contrast, the ZnPcCl8 PVD film displays a peak at 2θ = 6.41°, which deviates significantly from the expected position based on powder diffraction data. This shift implies the formation of another unknown crystal phase under PVD conditions. Spin-coated films of all three compounds, by comparison, display multiple sharp diffraction peaks that match well with reference powder patterns. This indicates that SC films adopt the same crystalline phase as the bulk powders, exhibit better crystallinity, and lack a preferred orientation. Using the Scherrer equation and accounting for instrumental broadening (0.05°), the coherent scattering region (CSR) sizes were estimated as follows: CoPcCl8: 8 nm (PVD) vs. 190 nm (SC); ZnPcCl8: 24 nm (PVD) vs. 110 nm (SC); VOPcCl8: 240 nm (SC only, as PVD film is amorphous). These results underscore the profound influence of deposition method on both crystallinity and phase formation.

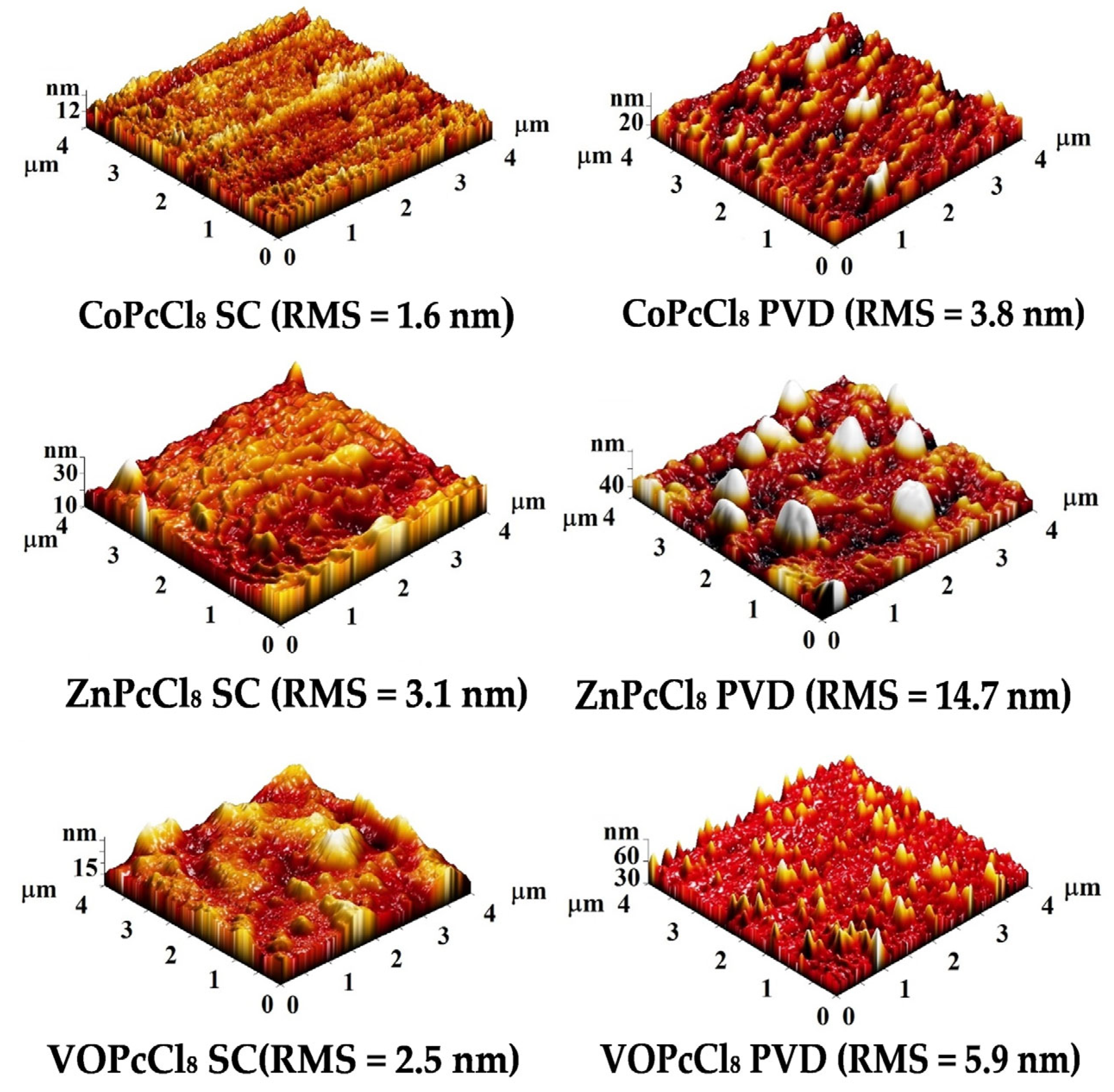

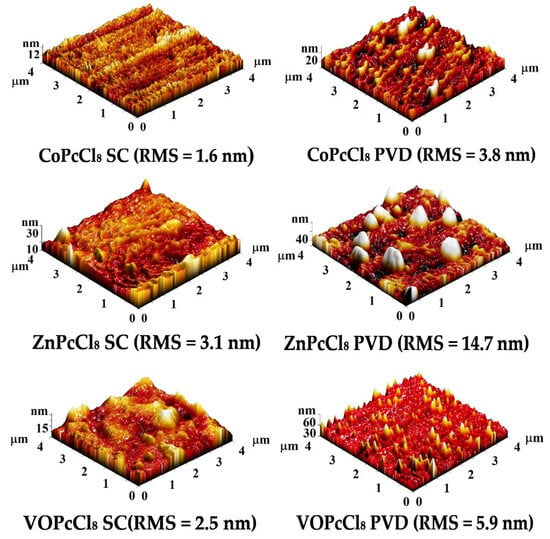

Figure 6 shows AFM topography images of CoPcCl8, ZnPcCl8, and VOPcCl8 prepared by spin-coating (SC) and physical vapor deposition (PVD). SC films have a smoother surface (3D RMS roughness 1.6–3.1 nm) with a homogeneous layered morphology and densely packed crystallites. The CoPcCl8 SC film has the smoothest surface (1.6 nm), indicating excellent film uniformity. PVD films have a rougher surface (3D RMS roughness: 3.8–14.7 nm) showing island-like or columnar growth due to vapor-phase nucleation. The ZnPcCl8 PVD film has the roughest surface (14.7 nm) with large spherical inclusions, while the VOPcCl8 PVD film has sharp needle-like features probably due to the directional influence of the V=O group. The data indicate that both the central metal and the deposition method significantly influence the surface microrelief.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional AFM images of the surface of VOPcCl8, ZnPcCl8 and CoPcCl8 films.

3.2.2. Electrical and Sensor Properties

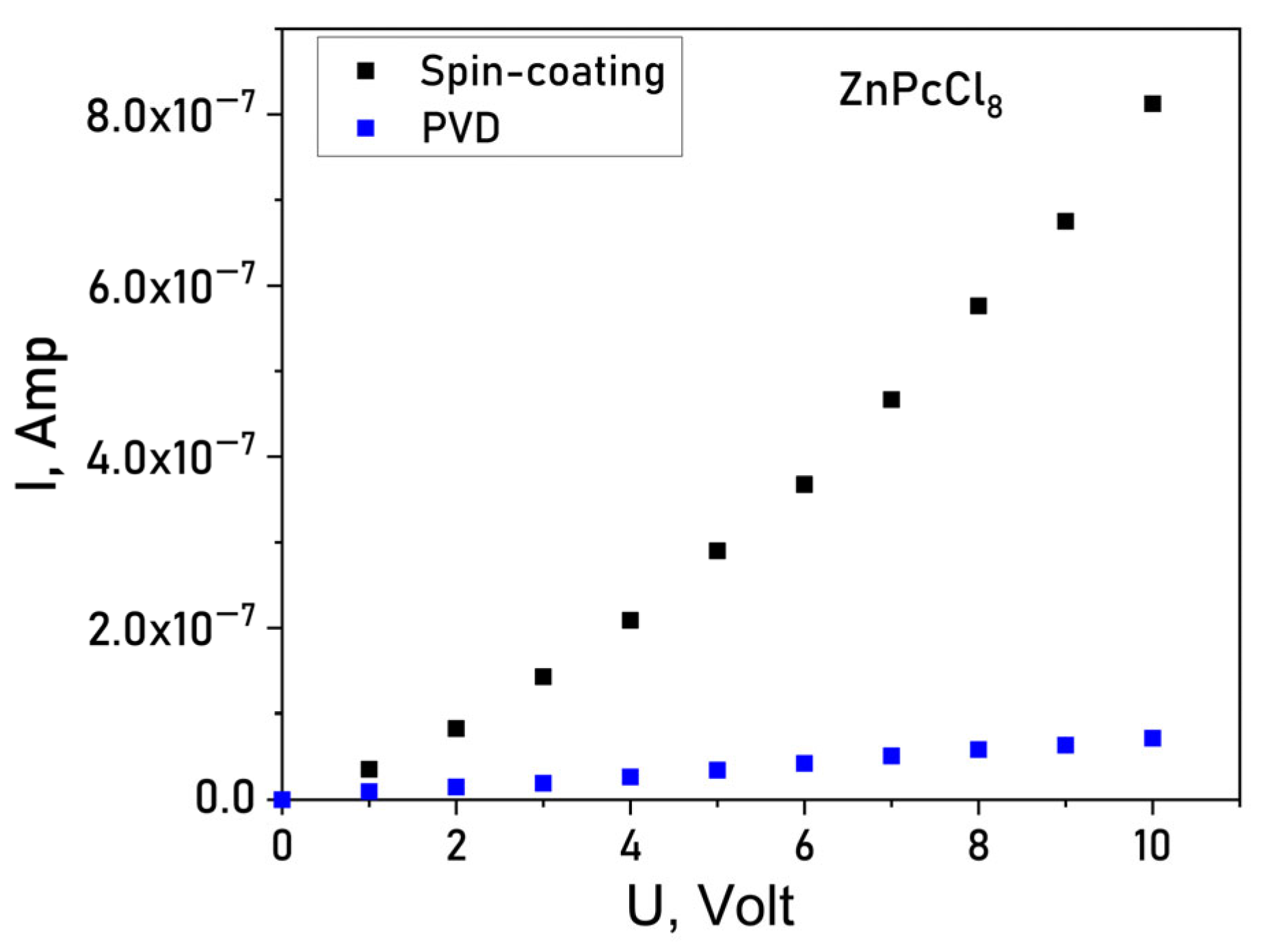

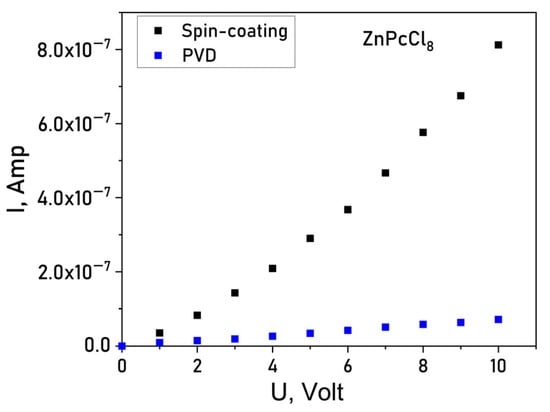

To evaluate the impact of the central metal ion and deposition method on conductivity current-voltage (I–V) characteristics of the films deposited onto glass substrates with interdigitated Pt electrodes using Keithley 236 electrometer. I(V) dependences of a ZnPcCl8 film are shown in Figure 7 as an example. Spin-coated MPcCl8 films displayed lateral DC conductivities in the range of 1 × 10−6–5 × 10−6 Ω−1 m−1. In contrast, PVD-deposited films exhibit markedly lower conductivity (5 × 10−9–6 × 10−9 Ω−1 m−1). The conduction mechanism also differed between deposition methods: PVD films showed ohmic behavior over 0–10 V, whereas SC films followed a space-charge-limited (SCL) conduction model, consistent with their higher crystallinity and grain-boundary-mediated transport. Notably, PVD films demonstrated negligible chemiresistive response and were deemed unsuitable for sensor applications. Consequently, all subsequent gas-sensing studies focused on SC-deposited films.

Figure 7.

Current-voltage (I(V)) dependence for a ZnPcCl8 film.

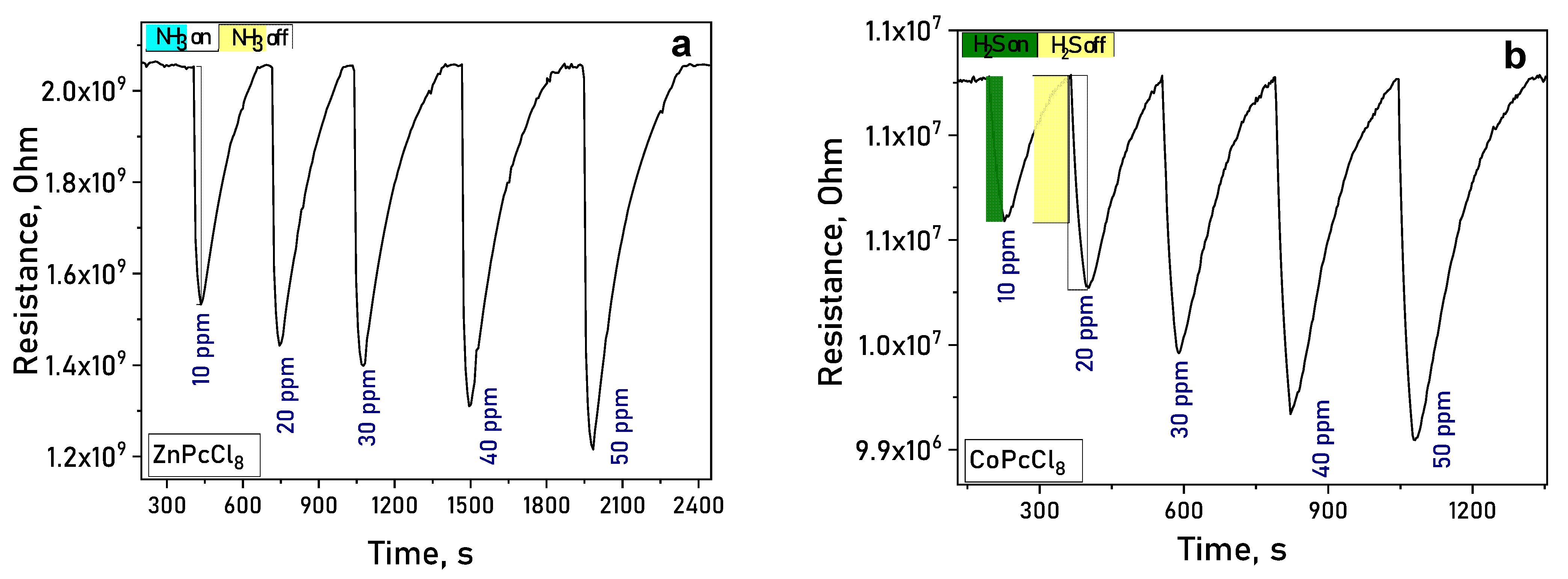

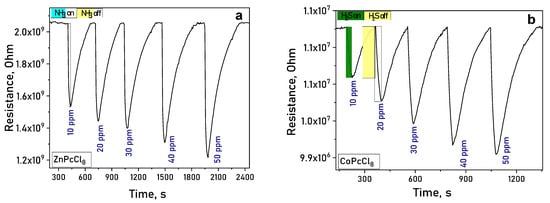

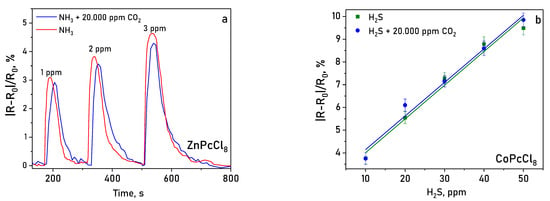

Upon exposure to ammonia (NH3) or hydrogen sulfide (H2S), the electrical resistance of MPcCl8 films decreased reversibly (Figure 8a,b), confirming n-type semiconducting behavior. In atmospheres of NH3 and H2S—both electron-donating gases—the resistance of n-type semiconductor films decreases, whereas the resistance of p-type semiconductors increases [59].

Figure 8.

(a) Change in the resistance of ZnPcCl8 (a) and CoPcCl8 (b) films during the introduction of ammonia and subsequent air purging.

Previous studies have shown that peripherally substituted cobalt phthalocyanine (CoPcCl4-p) exhibits n-type behavior, while its non-peripherally substituted analog (CoPcCl4-np) behaves as a p-type semiconductor [60]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that fluorinated phthalocyanines (MPcFx) can transfer from p-type to ambipolar and ultimately to n-type semiconductors depending on the degree of fluorination [61,62,63]. Chlorosubstituted phthalocyanines have been less extensively investigated. One notable exception is the work of Pakhomov et al. [64], who observed a decrease in the electrical conductivity of CuPcCl16 films upon exposure to NO2. Since NO2 is an electron-withdrawing gas, this decrease in conductivity implies that the majority charge carriers in CuPcCl16 are electrons—indicating n-type behavior—unlike unsubstituted CuPc or peripherally tetrachlorinated CuPcCl4-p, which typically exhibit p-type characteristics. Importantly, semiconducting behavior depends not only on the number and position of halogen substituents but also on the nature of the central metal ion. For instance, whereas CoPcCl4-p behaves as an n-type semiconductor, its zinc analog ZnPcCl4-p exhibits p-type behavior [2]. Additionally, in heterojunction gas sensors using 2,3,9,10,16,17,23,24-octachloro-substituted phthalocyanines as bottom layers, cobalt and copper derivatives showed opposite responses to ammonia [65]: the cobalt complex acted as a p-type material, while the copper analog displayed n-type characteristics. We provide quantum-chemical calculations in attempt to suggest semiconductor behavior of MPcCl8.

3.2.3. DFT Calculation of the Band Structure of CoPcCl8, ZnPcCl8, and VOPcCl8 Crystals

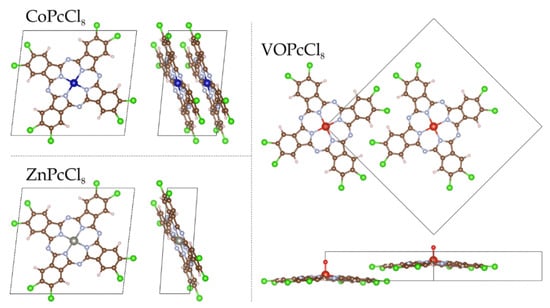

X-ray diffraction data were employed to generate computational models of the MPcCl8 crystals (M = Co, Zn, VO). Initially, the atomic coordinates within each system were relaxed under fixed lattice parameters: for ZnPcCl8 and VOPcCl8, optimizations were performed within the unit cell, whereas for CoPcCl8—a system requiring explicit treatment of spin correlations—a 2 × 1 × 1 supercell was utilized (Figure 9). These calculations were carried out using a Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid of 5 × 5 × 5 to adequately sample the first Brillouin zone [66].

Figure 9.

Top and side views of the geometric structures of MPcCl8 (M = Co, Zn, VO), showing the molecular plane from above and the lateral arrangement of the peripheral atoms from a side perspective.

The crystal structure of CoPcCl8 was modeled using a 2 × 1 × 1 supercell to properly account for the collective spin state of the system. The unit cell of CoPcCl8 contains a single phthalocyanine molecule; a spin-polarized calculation on this unit cell inherently yields a high-spin state (S = 1/2), arising from the unpaired electron localized on the cobalt center. In the 2 × 1 × 1 supercell, which encompasses two molecules, two distinct total spin states become accessible: a singlet state (S = 0) with antiparallel alignment of the Co-centered spins, and a triplet state (S = 1) with parallel alignment. Preliminary calculations revealed that the S = 0 state is energetically favored. Consequently, all subsequent calculations for CoPcCl8 were performed in the spin-singlet configuration.

A similar analysis was carried out for VOPcCl8. In contrast to CoPcCl8, the unit cell of VOPcCl8 already contains two molecules, enabling direct assessment of both parallel and antiparallel spin configurations without the need for a supercell. Preliminary computations confirmed that, likewise, the S = 0 state is more stable than the S = 1 state, due to strong intermolecular exchange interactions between the vanadium centers. Accordingly, all subsequent calculations for VOPcCl8 were also conducted in the spin-singlet state.

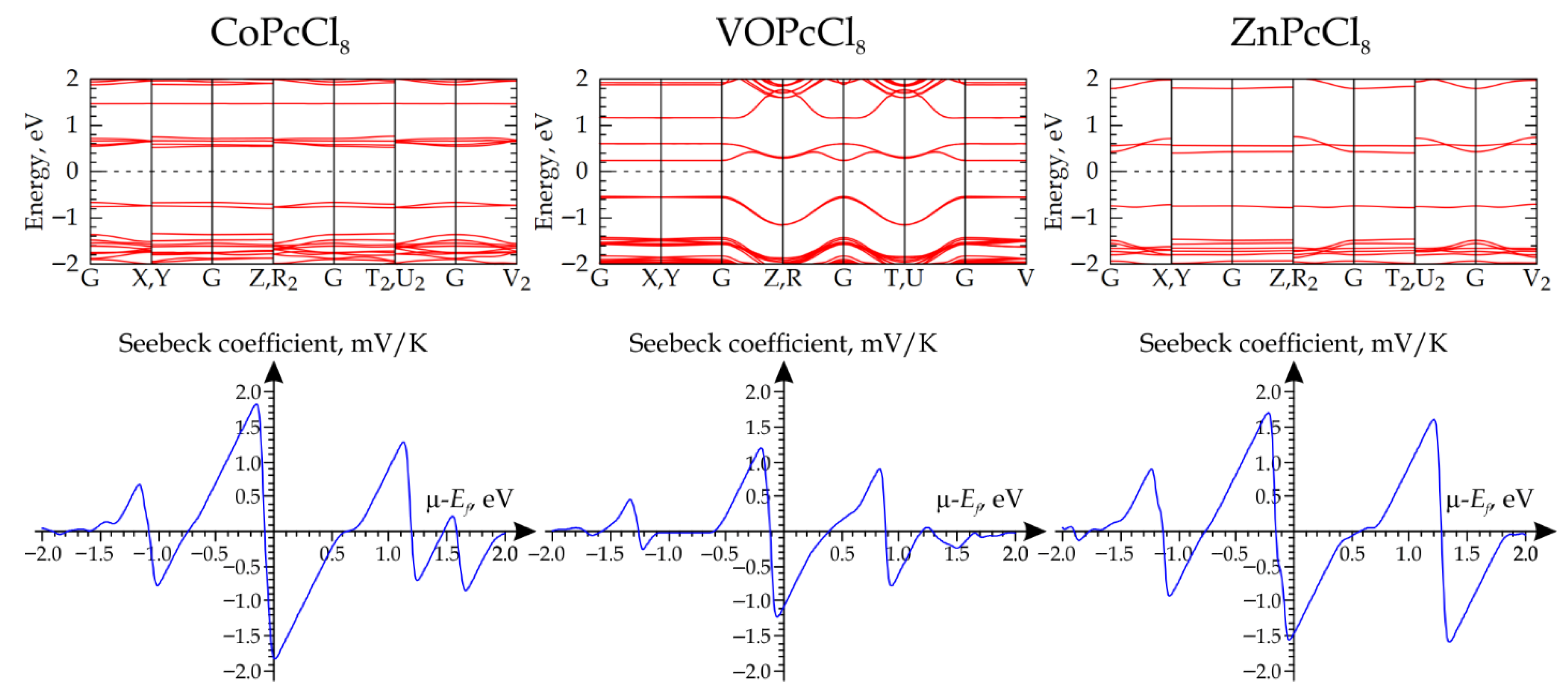

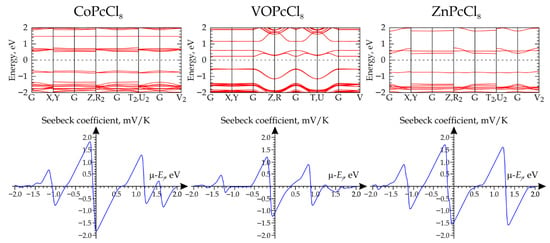

The subsequent step involved computing the electronic band structure, using a 15 × 15 × 15 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid to ensure adequate convergence of the electronic properties. The results indicate that CoPcCl8, VOPcCl8, and ZnPcCl8 are semiconductors with band gaps of 1.187 eV, 0.776 eV, and 1.105 eV, respectively (Figure 10). In all three materials, the Fermi level (EF) lies closer to the conduction band than to the valence band, suggesting n-type semiconductor behavior. The calculations of the electrical transport coefficients reveal a consistent trend: when the chemical potential (μ) is referenced to the EF and set to zero, the Seebeck coefficient assumes negative values across all studied materials (Figure 10). This unambiguously signifies that electrons are the dominant charge carriers under these conditions.

Figure 10.

Calculated band structures (top row) and corresponding Seebeck coefficient profiles as a function of chemical potential (bottom row) for MPcCl8 crystals (M = Co, VO, Zn).

Previous studies have shown that metal phthalocyanine molecules have two active sites, which means that interaction with analyte molecules can occur through both the central metal atom and the formation of hydrogen bonds between NH3 molecules and peripheral macrocycle atoms [2,27,67]. This interaction induces a redistribution of electronic charge within the phthalocyanine framework, altering its electronic structure and, consequently, its electrical conductivity, which is experimentally observed as a change in film resistance. Given that the investigated MPcCl8 compounds (M = Co, VO, Zn) exhibit n-type semiconducting behavior, the charge transfer mechanism upon NH3 and H2S adsorption proceeds as follows: gas molecules, acting as electron donors, transfer a portion of their electron density to the phthalocyanine macrocycles. This electron donation increases the concentration of the majority charge carriers (electrons) in the conduction band, resulting in a measurable decrease in the electrical resistance of the films.

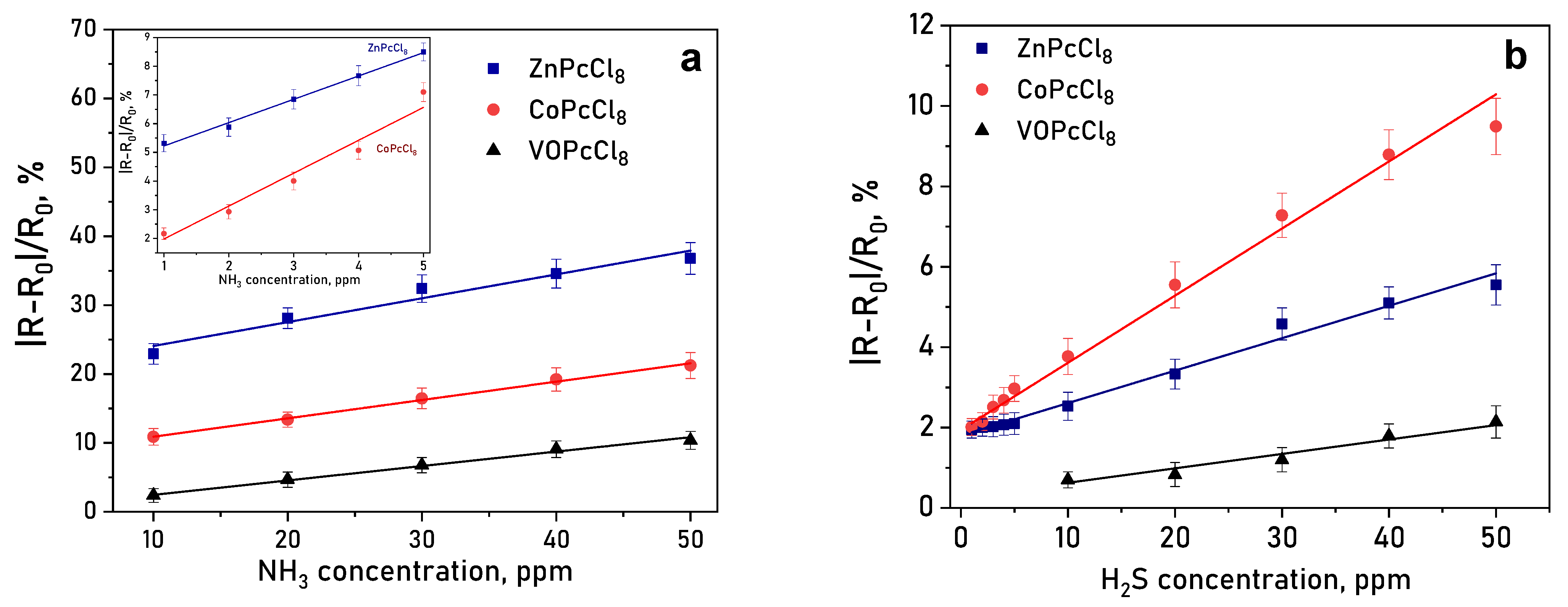

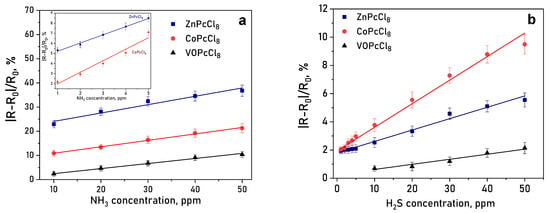

3.2.4. Sensor Characteristics

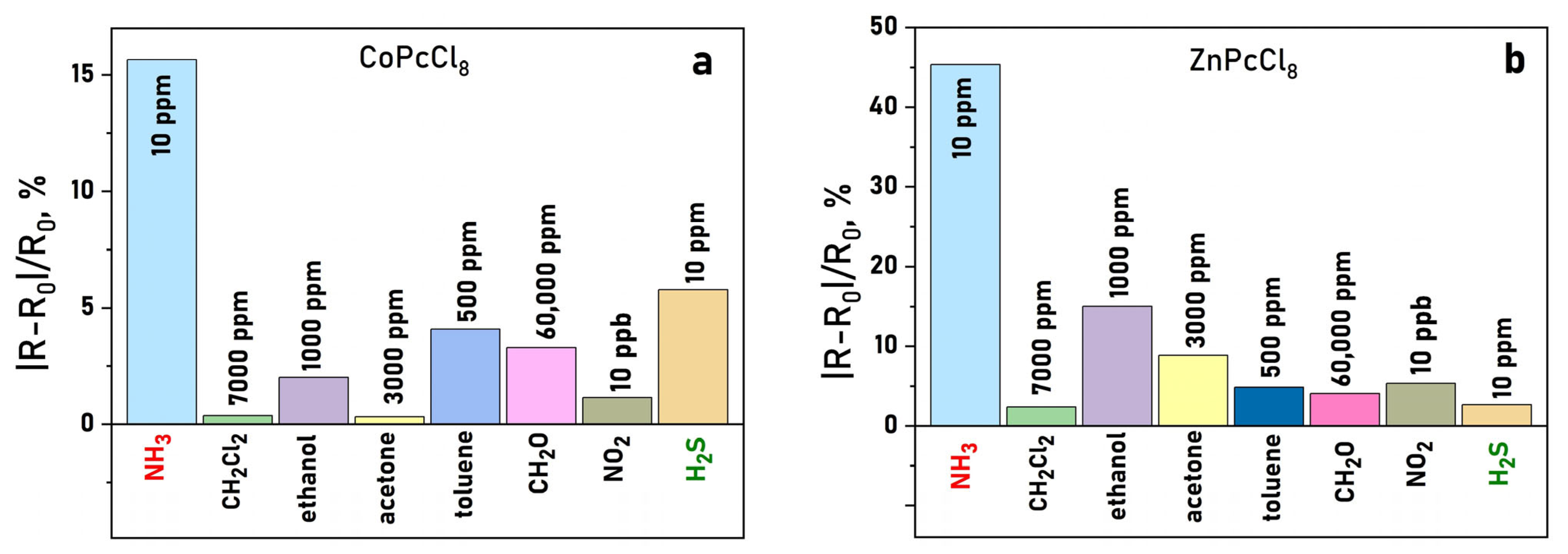

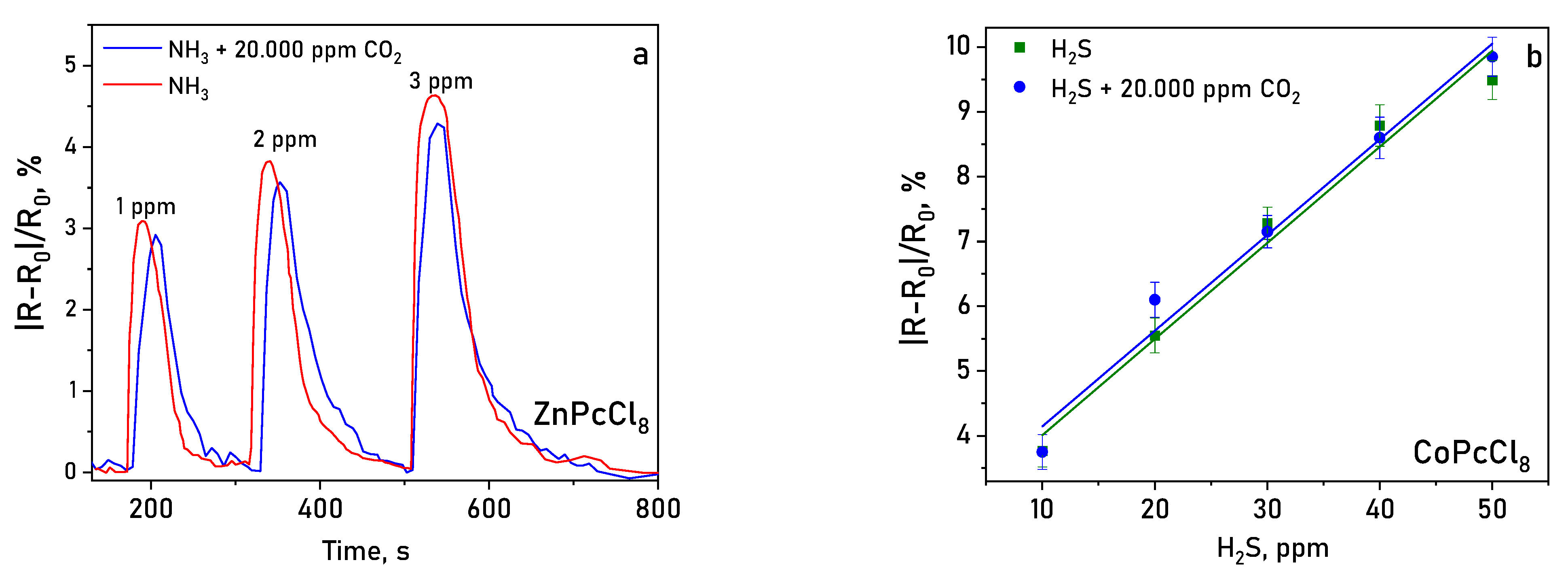

It is important to mention than the response reversible at room temperature, which is important characteristic of chemiresistive sensors. Response and recovery times are summarized in Table 4. A clear dependence on the central metal ion was observed. ZnPcCl8 films exhibited the highest response to NH3—over three times greater than CoPcCl8 (Figure 11a). CoPcCl8 films showed superior sensitivity to H2S (Figure 11b). VOPcCl8 displayed the weakest response to both analytes.

Table 4.

Limit of detection, response and recovery (10 ppm) times for SC MPcCl8.

Figure 11.

(a) Change in the resistance of a CoPcCl8 film during the introduction of hydrogen sulfide and subsequent air purging. (b) Dependence of the sensor response of MPcCl8 films on NH3 (a) and H2S (b) concentration (temperature 25 ± 2 °C, RH = 5%).

The distinct chemiresistive behavior of MPcCl8 toward NH3 and H2S can be attributed to the intrinsic electronic and coordination properties of the central metal ions. Cobalt in CoPcCl8 adopts a redox-active d7 configuration, which allows it to readily engage in charge-transfer interactions with soft Lewis bases. Hydrogen sulfide, with its highly polarizable sulfur atom and available lone pairs, acts as such a ligand and can coordinate to the Co2+ center, facilitating partial electron donation into the phthalocyanine π-system and thereby enhancing n-type conduction. In contrast, Zn2+ in ZnPcCl8 possesses a closed-shell d10 configuration and is redox-inert under ambient sensing conditions. As a hard Lewis acid, Zn2+ preferentially interacts with hard Lewis bases such as ammonia, where the electronegative nitrogen atom provides a localized, high-energy lone pair that forms a relatively stronger donor-acceptor interaction with the Zn center. This interaction effectively modulates the electron population in the conduction band, leading to the pronounced NH3 response observed experimentally. In the case of VOPcCl8, the presence of the axial V=O bond likely sterically blocks direct access of analyte molecules to the vanadium center, while also withdrawing electron density from the macrocycle, thereby reducing its sensitivity to both gases.

Although this qualitative picture is in good agreement with experimental trends and established principles of coordination chemistry, further modeling of adsorption geometry, binding energies, and charge transfer pathways, as well as experimental measurements such as X-ray and ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS/UPS), would be useful for more thorough verification. Such analyses could directly probe shifts in core-level binding energies (e.g., N 1s, S 2p, or metal 2p/3p levels) and changes in the work function or valence-band edge upon analyte exposure, offering unambiguous evidence of metal-analyte interaction mechanisms. These investigations represent a natural extension of the current work and are planned for future research.

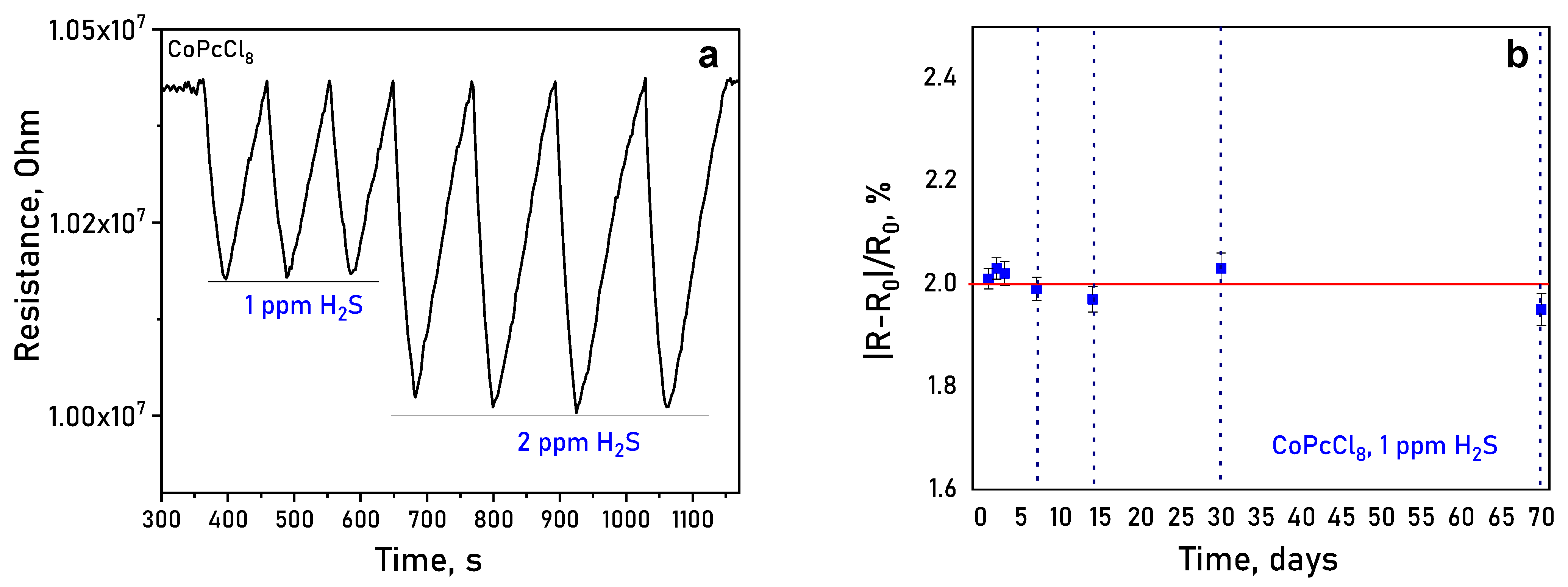

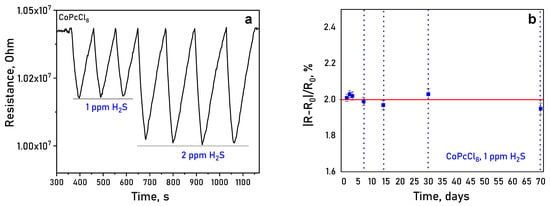

It was shown using CoPcCl8 films as an example that the sensors demonstrated excellent repeatability, with response variations to repeated exposures of 1 and 2 ppm H2S remaining within ±5% (Figure 12a). To confirm the long-term stability the response of the same film to 1 ppm of H2S was measured after 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, 30 and 70 days (Figure 12b). The change in the sensor response did not exceed the measurement error, which indicated long-term response stability.

Figure 12.

(a) Change in the resistance of a CoPcCl8 film during repeated exposures of 1 and 2 ppm H2S (temperature 25 ± 2 °C, RH = 5%); (b) long-term operational results of a CoPcCl8 film sensing material to 1 ppm H2S.

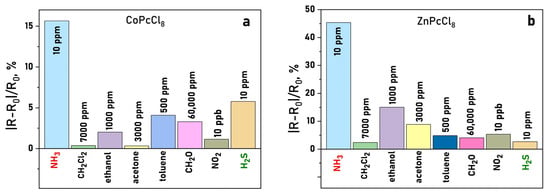

Selectivity tests against common interferents, namely acetone, ethanol, toluene, formaldehyde, dichloromethane, and NO2, revealed that CoPcCl8 and ZnPcCl8 films respond preferentially to H2S and NH3, even when interferents were present at significantly higher concentrations (Figure 13a,b). This highlights their potential for selective detection in complex gas mixtures.

Figure 13.

Sensor response of CoPcCl8 (a) and ZnPcCl8 (b) NH3 (10 ppm), H2S (10 ppm), NO2 (10 ppm), dichloromethane (7000 ppm), ethanol (1000 ppm), formaldehyde (60,000 ppm) and acetone (3000 ppm) (temperature 25 ± 2 °C, RH = 5%).

Layers were tested in a mixture of gases containing 20.000 ppm of CO2 (Figure 14). It was shown that the determination of NH3 and H2S in the presence of carbon dioxide did not lead to a significant change (within the measurement error) in the sensor response measured in air.

Figure 14.

Sensor response of ZnPcCl8 (a) to NH3 (1–3 ppm) and of CoPcCl8 (b) to H2S (10–50 ppm) in the presence of 20.000 ppm CO2 (temperature 25 ± 2 °C, RH = 5%).

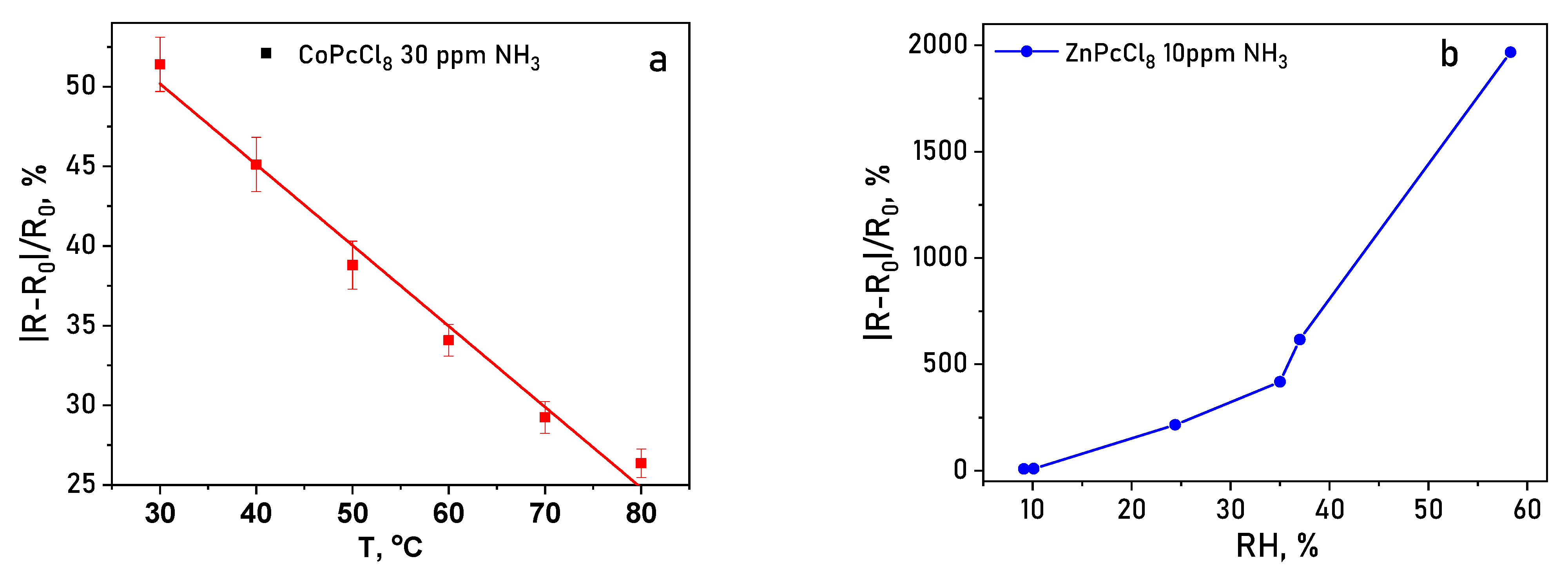

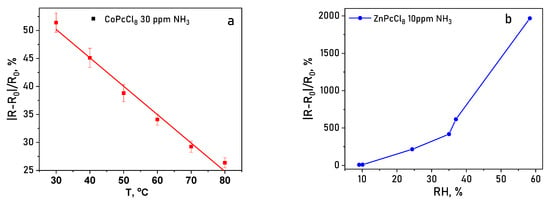

Operating temperature and relative humidity (RH) strongly modulate sensor performance. Increasing temperature from 30 to 80 °C consistently reduced the response value for both CoPcCl8 and ZnPcCl8 (Figure 15a), likely due to accelerated desorption of analyte molecules. Conversely, elevated RH dramatically enhanced sensitivity: at 30% RH, the NH3 response increased by ~50-fold compared to dry conditions, and at 50% RH, the enhancement reached ~250-fold (Figure 15b). This pronounced humidity dependence suggests that water molecules facilitate analyte adsorption or proton-coupled charge transfer processes at the film surface. Therefore, humidity can significantly affect the sensor’s response, and it must be monitored during the measurement process. To mitigate the effects of humidity, various approaches can be employed. These approaches can be broadly categorized into computational and experimental methods. The computational method involves processing the data obtained from humidity sensors using calibration curves created at different humidity levels. In the experimental approach, waterproof membranes are employed to prevent moisture from reaching the gas-sensitive films.

Figure 15.

(a) Temperature dependence (30–80 °C) of the sensor response of the CoPcCl8 toward 30 ppm NH3. (b) Sensor response of a ZnPcCl8 film to 10 ppm NH3 measured at various RH.

Table 5 represents the sensor response of halogen-substituted metal phthalocyanine films to 10 ppm ammonia. It is shown that zinc octachlorophthalocyanine (ZnPcCl8) films prepared by solution-based methods exhibit a sensor response comparable to, and in some cases superior to, that of other variants. Solution-based film deposition methods offer significant advantages over physical vapor deposition, including lower cost, compatibility with flexible and large-area substrates, and the formation of porous/high-surface-area morphologies that can enhance gas sensitivity. These benefits make our SC film promising for fabricating low-cost phthalocyanine-based sensors with superior response characteristics.

Table 5.

Sensor response of the films of halogenated metal phthalocyanines to ammonia (10 ppm).

4. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive investigation of octachlorinated metal phthalocyanines (MPcCl8, M = Co, Zn, VO) as active materials for chemiresistive gas sensors. For the first time, the single-crystal structure of CoPcCl8 was resolved, confirming a triclinic lattice with cofacial molecular stacks. Comparative structural analysis shows that ZnPcCl8 is isostructural with CoPcCl8, whereas VOPcCl8 crystallizes in a tetragonal system, likely influenced by the axial V=O bond. Thin film morphology and crystallinity are critically dependent on the deposition method: spin-coated films exhibit high crystallinity, and phase similarity to bulk powders, while a PVD method yields poorly ordered or amorphous layers with significantly lower electrical conductivity. Consequently, only SC films demonstrated reliable chemiresistive responses. All MPcCl8 SC films displayed n-type semiconducting behavior, as confirmed by both experimental data and DFT-based band structure calculations. Upon exposure to NH3 and H2S, which are both electron-donating gases, the film resistance decreased reversibly, consistent with increased electron concentration in the conduction band. ZnPcCl8 exhibited the highest response to NH3 (45.3% at 10 ppm, LOD = 0.8 ppm), whereas CoPcCl8 showed superior sensitivity to H2S (LOD = 0.3 ppm). As a limitation of these sensors, it should be noted that they are sensitive to humidity, highlighting the importance of environmental conditions in practical deployment: ambient humidity dramatically enhanced sensor response by up to two orders of magnitude. The sensors also demonstrated excellent selectivity against common volatile organic compounds and repeatability over multiple exposure cycles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K., P.K. and T.B.; methodology, D.K. and T.B.; software, P.K.; validation, P.K. and D.K.; formal analysis, P.K., T.K., P.P., D.K. and. A.S.; investigation, P.K., A.S., D.K., P.P. and T.K.; resources, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K., P.P. and T.B.; writing—review and editing, D.K., P.P. and T.B.; visualization, T.K. and P.K.; supervision, T.B.; project administration, D.K.; funding acquisition, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 24-73-10058.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation for the access to the computational cluster.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sánchez Vergara, M.E.; Sánchez Moore, H.I.; Cantera-Cantera, L.A. Investigation of Halogenated Metallic Phthalocyanine (InPcCl and F16CuPc)-Based Electrodes and Palm Substrate for Organic Solid-State Supercapacitor Fabrication. Micromachines 2025, 16, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonegardt, D.; Klyamer, D.; Sukhikh, A.; Krasnov, P.; Popovetskiy, P.; Basova, T. Fluorination vs. Chlorination: Effect on the Sensor Response of Tetrasubstituted Zinc Phthalocyanine Films to Ammonia. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, S.; Farajzadeh, N.; Yasemin Yenilmez, H.; Özdemir, S.; Gonca, S.; Altuntaş Bayır, Z. Fluorinated Phthalocyanine/Silver Nanoconjugates for Multifunctional Biological Applications. Chem. Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202300389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Y.; Cai, P.; Xu, K.; Li, H.; Chen, H.; Zhou, H.-C.; Huang, N. Stable Bimetallic Polyphthalocyanine Covalent Organic Frameworks as Superior Electrocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 18052–18060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, S.; Lou, Y.; Zhao, S.; Tan, Q.; He, L.; Du, M. A copper(II) phthalocyanine-based metallo-covalent organic framework decorated with silver nanoparticle for sensitively detecting nitric oxide released from cancer cells. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 338, 129826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Feng, Y.; Wee, A.G.H.; Zhang, B. Porphyrin- and porphyrinoid-based covalent organic frameworks (COFs): From design, synthesis to applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 435, 213778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Q.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K. New vitality of covalent organic frameworks endued by phthalocyanine: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 527, 216404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmina, E.A.; Dubinina, T.V.; Tomilova, L.G. Recent advances in chemistry of phthalocyanines bearing electron-withdrawing halogen, nitro and: N-substituted imide functional groups and prospects for their practical application. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 9314–9327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyamer, D.; Bonegardt, D.; Basova, T. Fluoro-Substituted Metal Phthalocyanines for Active Layers of Chemical Sensors. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhikh, A.; Klyamer, D.; Bonegardt, D.; Popovetsky, P.; Krasnov, P.; Basova, T. Tetrafluorosubstituted titanyl phthalocyanines: Structure of single crystals and phase transition in thin films. Dye. Pigment. 2024, 231, 112391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzumoto, Y.; Matsuyama, H.; Kitamura, M. Structural and electrical properties of fluorinated copper phthalocyanine toward organic photovoltaics: Post-annealing effect under pressure. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 53, 04ER16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyamer, D.D.; Sukhikh, A.S.; Trubin, S.V.; Gromilov, S.A.; Morozova, N.B.; Basova, T.V.; Hassan, A.K. Tetrafluorosubstituted Metal Phthalocyanines: Interplay between Saturated Vapor Pressure and Crystal Structure. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.G.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, S.R. Synthesis, photophysical and thermal properties of 2,9,16,23-tetrafluoro substituted metallophthalocyanines. Mater. Res. Innov. 2014, 18, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuate Gomez, D.H.; Garzón Román, A.; Sosa Sanchez, J.L.; Zuñiga Islas, C.; Lugo, J.M. Dichloro-tin (IV) hexadeca-fluoro-phthalocyanine (F16PcSnCl2) thin film on porous silicon layers by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis, for possible application in optoelectronics devices. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 85938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Ye, J.; Hu, P.; Wei, F.; Du, K.; Wang, N.; Ba, T.; Feng, S.; Kloc, C. Fluorination of Metal Phthalocyanines: Single-Crystal Growth, Efficient N-Channel Organic Field-Effect Transistors and Structure-Property Relationships. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, Z.; Meunier-Prest, R.; Dumoulin, F.; Kumar, A.; Isci, Ü.; Bouvet, M. Tuning of organic heterojunction conductivity by the substituents’ electronic effects in phthalocyanines for ambipolar gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 332, 129505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.; Singer, B.W.; Perry, J.J. The identification of synthetic organic pigments in modern paints and modern paintings using pyrolysis-gas chromatography—Mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 400, 1473–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Hornbuckle, K.C. Inadvertent Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Commercial Paint Pigments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 2822–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.U.; Kim, C.; Mizuseki, H.; Kawazoe, Y. The Origin of the Halogen Effect on the Phthalocyanine Green Pigments. Chem. Asian J. 2010, 5, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbunova, E.A.; Stepanova, D.A.; Kosov, A.D.; Bolshakova, A.V.; Filatova, N.V.; Sizov, L.R.; Rybkin, A.Y.; Spiridonov, V.V.; Sybachin, A.V.; Dubinina, T.V.; et al. Dark and photoinduced cytotoxicity of solubilized hydrophobic octa-and hexadecachloro-substituted lutetium (III) phthalocyanines. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2022, 426, 113747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavtsev, D.D.; Dubinina, T.V.; Gorbunova, E.A.; Gerasimenko, A.Y. A Method for Fluorescent Diagnosis of Malignant Cutaneous Neoplasms Using Ytterbium Phthalocyanines. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 56, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slodeka, A.; Schnurpfeilb, G.; Wöhrle, D. Optical limiting of germanium(IV) and tin(IV) phthalocyanines in solution and polymer matrices and comparison to an indium(III) phthalocyanine. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2017, 21, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmina, E.A.; Dubinina, T.V.; Borisova, N.E.; Tarasevich, B.N.; Krasovskii, V.I.; Feofanov, I.N.; Dzuban, A.V.; Tomilova, L.G. Dyes and Pigments Planar and sandwich-type Pr (III) and Nd (III) chlorinated phthalocyaninates: Synthesis, thermal stability and optical properties. Dye. Pigment. 2020, 174, 108075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milde, P.; Zerweck, U.; Eng, L.M.; Abel, M.; Giovanelli, L.; Nony, L.; Mossoyan, M.; Porte, L.; Loppacher, C. Interface dipole formation of different ZnPcCl 8 phases on Ag (111) observed by Kelvin probe force microscopy. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 305501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobaru, S.C.; Salomon, E.; Layet, J.-M.; Angot, T. Structural Properties of Iron Phtalocyanines on Ag(111): From the Submonolayer to Monolayer Range. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 5875–5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelberger, A.; Kramberger, C.; Meyer, J.C. Insights into radiation damage from atomic resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy imaging of mono-layer CuPcCl16 films on graphene. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyamer, D.; Sukhikh, A.; Bonegardt, D.; Krasnov, P.; Popovetskiy, P.; Basova, T. Thin Films of Chlorinated Vanadyl Phthalocyanines as Active Layers of Chemiresistive Sensors for the Detection of Ammonia. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basova, T.V.; Kiselev, V.G.; Klyamer, D.D.; Hassan, A. Thin films of chlorosubstituted vanadyl phthalocyanine: Charge transport properties and optical spectroscopy study of structure. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 16791–16798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.R.V.; Keshavayya, J.; Seetharamappa, J. Synthesis, spectral, magnetic and thermal studies on symmetrically substituted metal (II). Dye. Pigment. 2003, 59, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraonov, M.A.; Romanenko, N.R.; Kuzmin, A.V.; Konarev, D.V.; Khasanov, S.S.; Lyubovskaya, R.N. Crystalline salts of the ring-reduced tin (IV) dichloride hexadecachlorophthalocyanine and octachloro-and octacyanotetrapyrazinoporphyrazine macrocycles with strong electron-withdrawing ability. Dye. Pigment. 2020, 180, 108429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achar, B.N.; Mohan Kumar, T.M.; Lokesh, K.S. Synthesis, characterization, pyrolysis kinetics and conductivity studies of chloro substituted cobalt phthalocyanines. J. Coord. Chem. 2007, 60, 1833–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, S.; Ouedraogo, S.; Meunier-Prest, R.; Kumar, A.; Bayo-Bangoura, M.; Bouvet, M. Modulating the Electrical Properties of Organic Heterojunction Devices Based on Phthalocyanines for Ambipolar Sensors. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhikh, A.; Klyamer, D.; Bonegardt, D.; Basova, T. Octafluoro-Substituted Phthalocyanines of Zinc, Cobalt, and Vanadyl: Single Crystal Structure, Spectral Study and Oriented Thin Films. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APEX3; v.2019.1-0. Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2019.

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. B 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Ernzerhof, M.; Burke, K. Rationale for mixing exact exchange with density functional approximations. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105, 9982–9985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, L.; Bylander, D.M. Efficacious Form for Model Pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 48, 1425–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, I.; Bylander, D.M.; Kleinman, L. Nonlocal Hermitian norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotential. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 6728–6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, P.E. Generalized separable potentials for electronic-structure calculations. Phys. Rev. B 1990, 41, 5414–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachelet, G.B.; Hamann, D.R.; Schlüter, M. Pseudopotentials that work: From H to Pu. Phys. Rev. B 1982, 26, 4199–4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troullier, N.; Martins, J.L. Efficient pseudopotentials for plane-wave calculations. II. Operators for fast iterative diagonalization. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 43, 8861–8869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troullier, N.; Martins, J.L. Efficient pseudopotentials for plane-wave calculations. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 43, 1993–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, T. Variationally optimized atomic orbitals for large-scale electronic structures. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67, 155108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, T.; Kino, H. Numerical atomic basis orbitals from H to Kr. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 195113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimov, V.I.; Zaanen, J.; Andersen, O.K. Band theory and Mott insulators: Hubbard U instead of Stoner I. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudarev, S.L.; Botton, G.A.; Savrasov, S.Y.; Humphreys, C.J.; Sutton, A.P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 57, 1505–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Brena, B.; Banerjee, R.; Wende, H.; Eriksson, O.; Sanyal, B. Electronic structure of Co-phthalocyanine calculated by GGA+U and hybrid functional methods. Chem. Phys. 2010, 377, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumboiu, I.E.; Haldar, S.; Lüder, J.; Eriksson, O.; Herper, H.C.; Brena, B.; Sanyal, B. Influence of Electron Correlation on the Electronic Structure and Magnetism of Transition-Metal Phthalocyanines. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 1772–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Sun, Q. Magnetism of Phthalocyanine-Based Organometallic Single Porous Sheet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 15113–15119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, M.; Hayn, R.; Denawi, H.; Ben Chaabane, R. Possibility of a ferromagnetic and conducting metal-organic network. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2018, 453, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, P.B. Boltzmann Theory and Resistivity of Metals. In Quantum Theory of Real Materials; Chelikowsky, J.R., Louie, S.G., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 219–250. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, G.K.H.; Singh, D.J. BoltzTraP. A code for calculating band-structure dependent quantities. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2006, 175, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonegardt, D.; Klyamer, D.; Krasnov, P.; Sukhikh, A.; Basova, T. Effect of the position of fluorine substituents in tetrasubstituted metal phthalocyanines on their vibrational spectra. J. Fluor. Chem. 2021, 246, 109780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, M.R.; Pastrana, L.M.; Sosa, C.D.F.; Marquina, A.M.R.; Izquierdo, J.E.E.; Fonseca, F.J.; de Amorim, C.A.; Paterno, L.G.; Kymissis, I. Organic thin-film transistors as gas sensors: A review. Materials 2021, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyamer, D.; Bonegardt, D.; Sukhikh, A.; Krasnov, P.; Basov, A. Films of tetrachlorosubstituted cobalt phthalocyanines: The effect of the position of substituents and the deposition method on their structure and sensor properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2025. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, X.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Su, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, Y. Single component p-, ambipolar and n-type OTFTs based on fluorinated copper phthalocyanines. Dye. Pigment. 2016, 132, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vebber, M.C.; King, B.; French, C.; Tousignant, M.; Ronnasi, B.; Dindault, C.; Wantz, G.; Hirsch, L.; Brusso, J.; Lessard, B.H. From P-type to N-type: Peripheral fluorination of axially substituted silicon phthalocyanines enables fine tuning of charge transport. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 101, 3019–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, H.; Kelting, C.; Makarov, S.; Tsaryova, O.; Schnurpfeil, G.; Wöhrle, D.; Schlettwein, D. Fluorinated phthalocyanines as molecular semiconductor thin films. Phys. Status Solidi Appl. Mater. Sci. 2008, 205, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhomov, L.G.; Pakhomov, G.L. NO2 interaction with thin film of phthalocyanine derivatives {1}. Synth. Met. 1995, 71, 2299–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, S.; Coulibaly, T.; Meunier-Prest, R.; Bayo-Bangoura, M.; Bouvet, M. P-Type and n-type conductometric behaviors of octachloro-metallophthalocyanine-based heterojunctions, the key role of the metal. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2020, 24, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkhorst, H.J.; Pack, J.D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyamer, D.; Bonegardt, D.; Krasnov, P.; Sukhikh, A.; Popovetskiy, P.; Basova, T. Tetrafluorosubstituted Metal Phthalocyanines: Study of the Effect of the Position of Fluorine Substituents on the Chemiresistive Sensor Response to Ammonia. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.