OH* 3D Concentration Measurement of Non-Axisymmetric Flame via Near-Ultraviolet Volumetric Emission Tomography

Abstract

1. Introduction

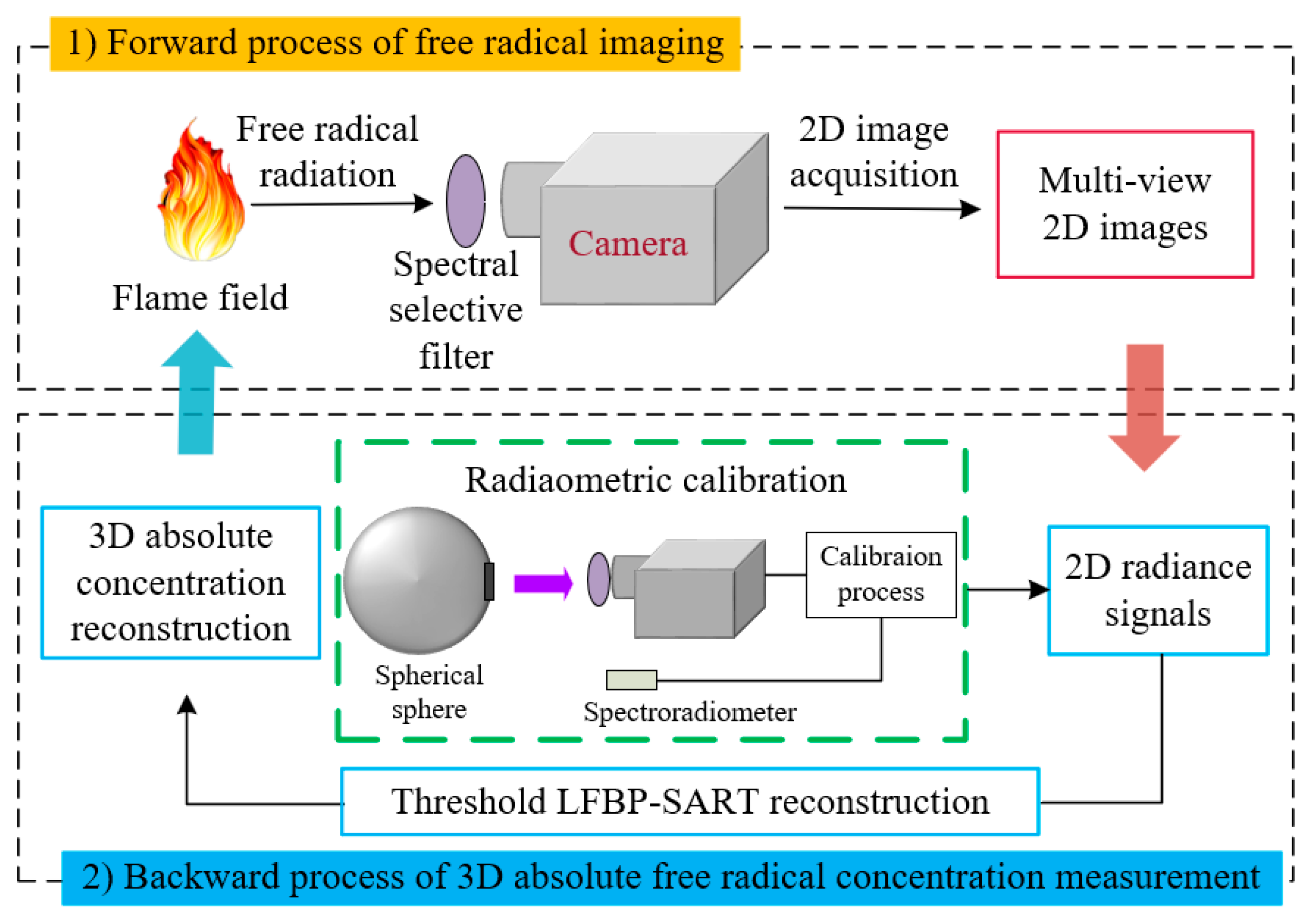

2. Theoretical Imaging Model and Quantitative Measurement Method

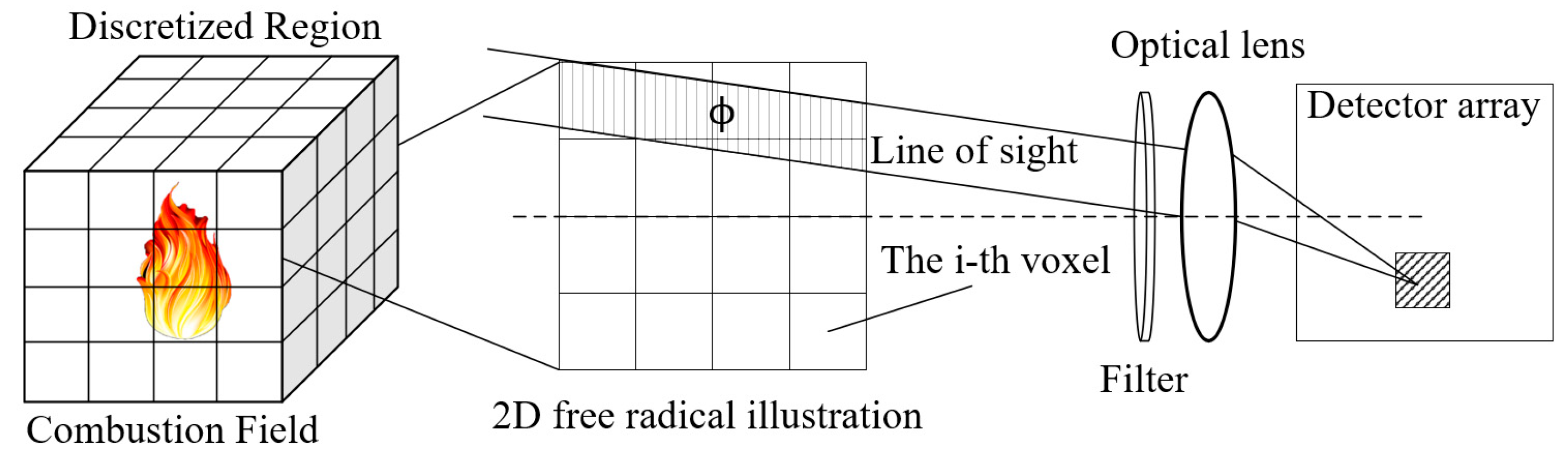

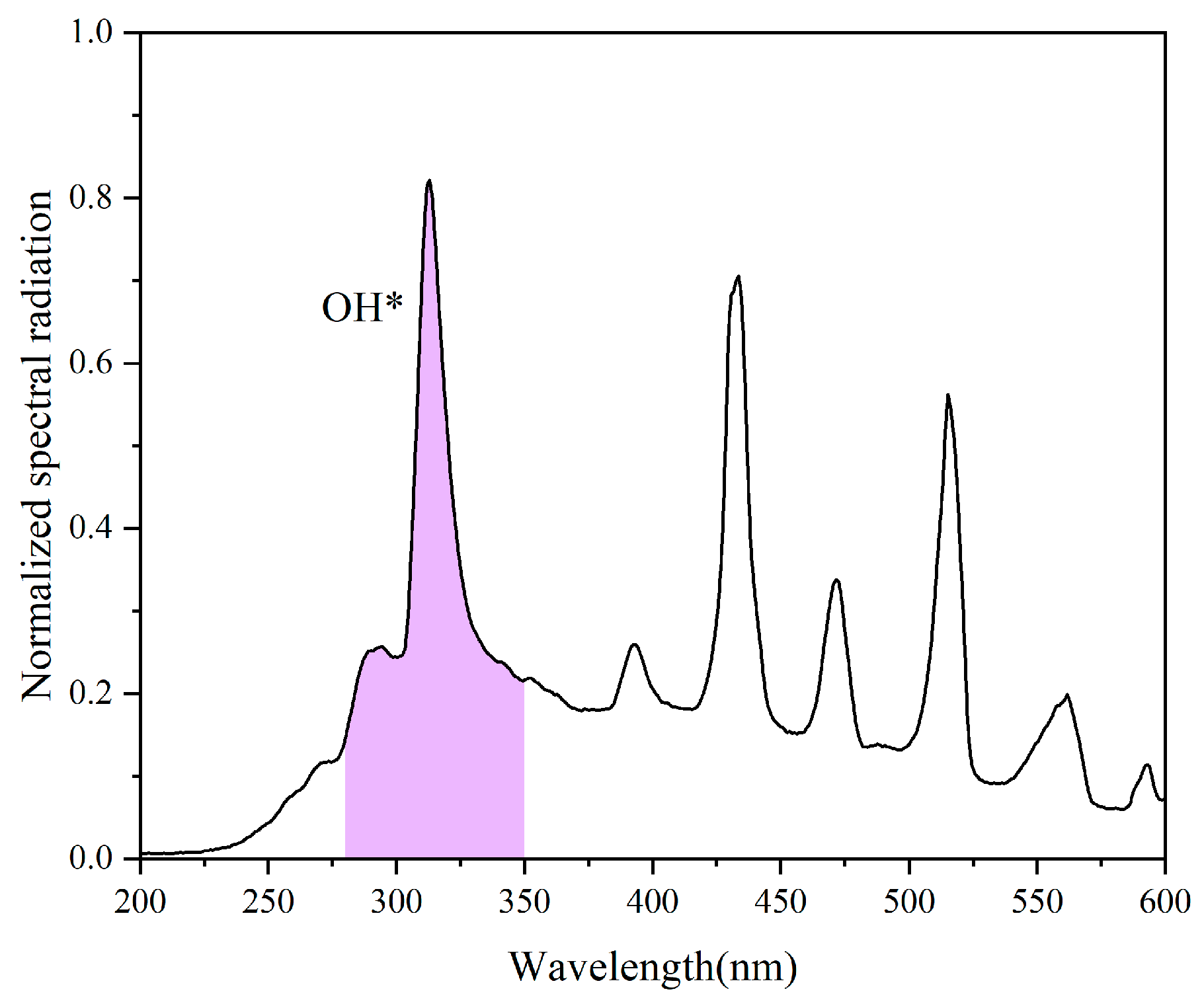

2.1. Three-Layer Imaging Model of Free Radicals

2.2. Absolute Concentration Measurement Based on Radiometric Calibration and Threshold-Constrained LFBP-SART

3. Experimental Setup

3.1. Two-Dimensional Imaging Setup for Bunsen Burner Flame

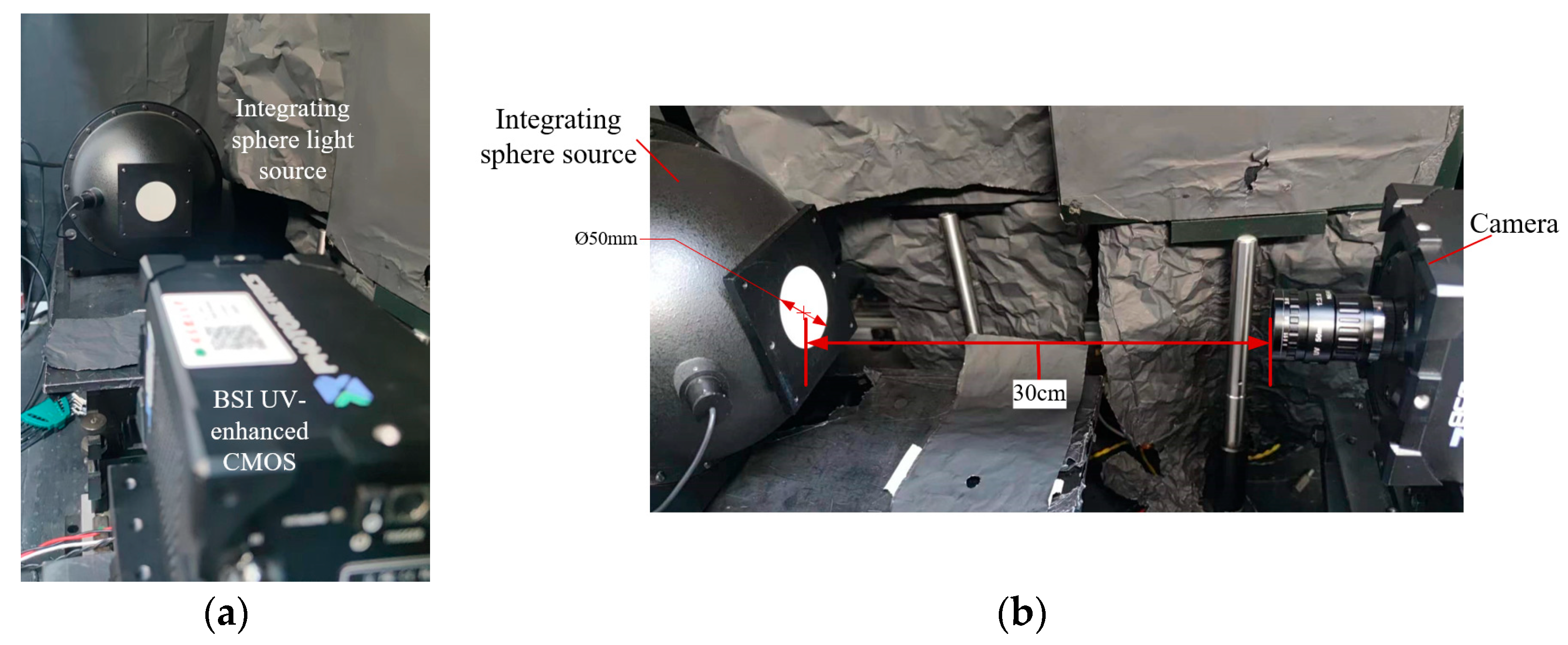

3.2. Radiometric Calibration System

4. Results and Discussion

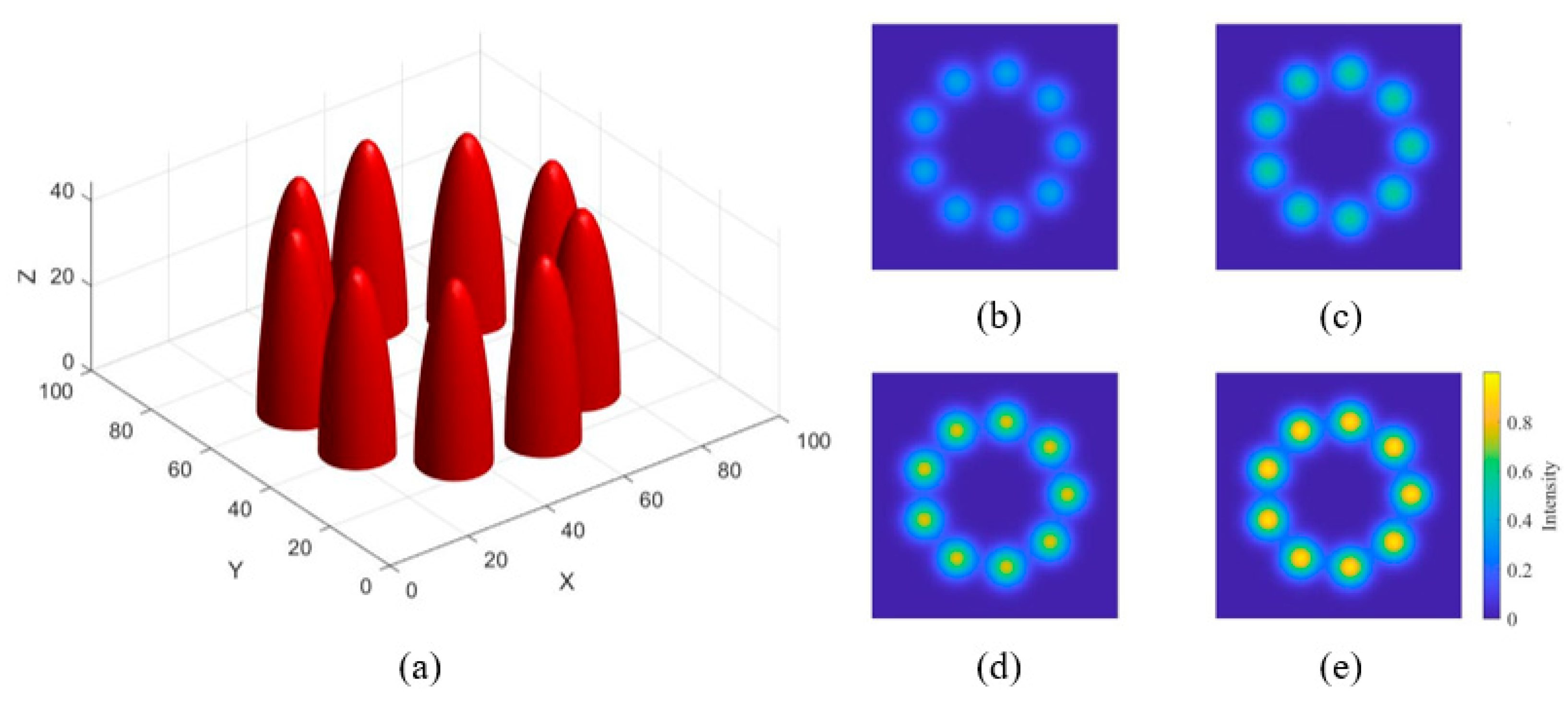

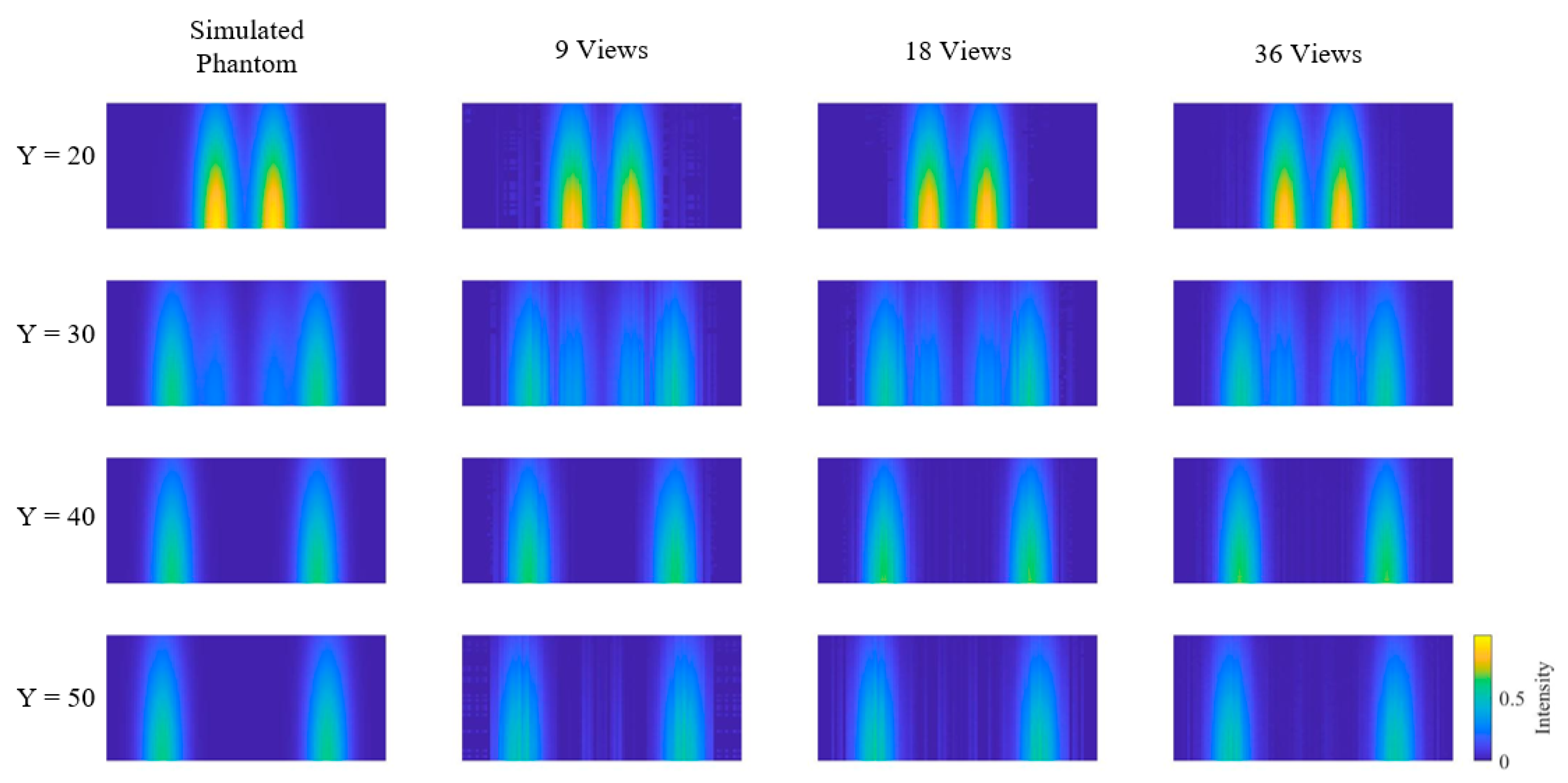

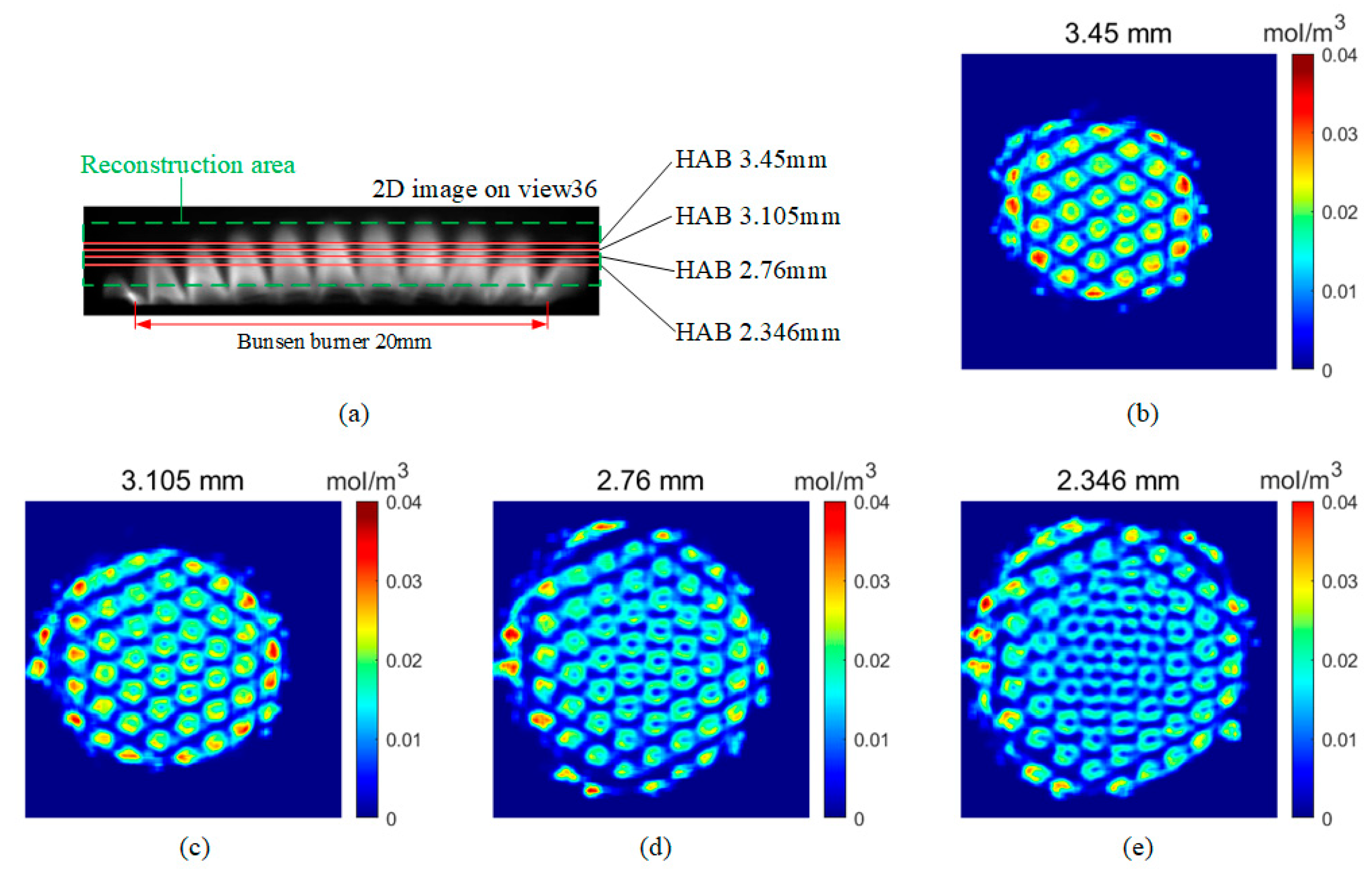

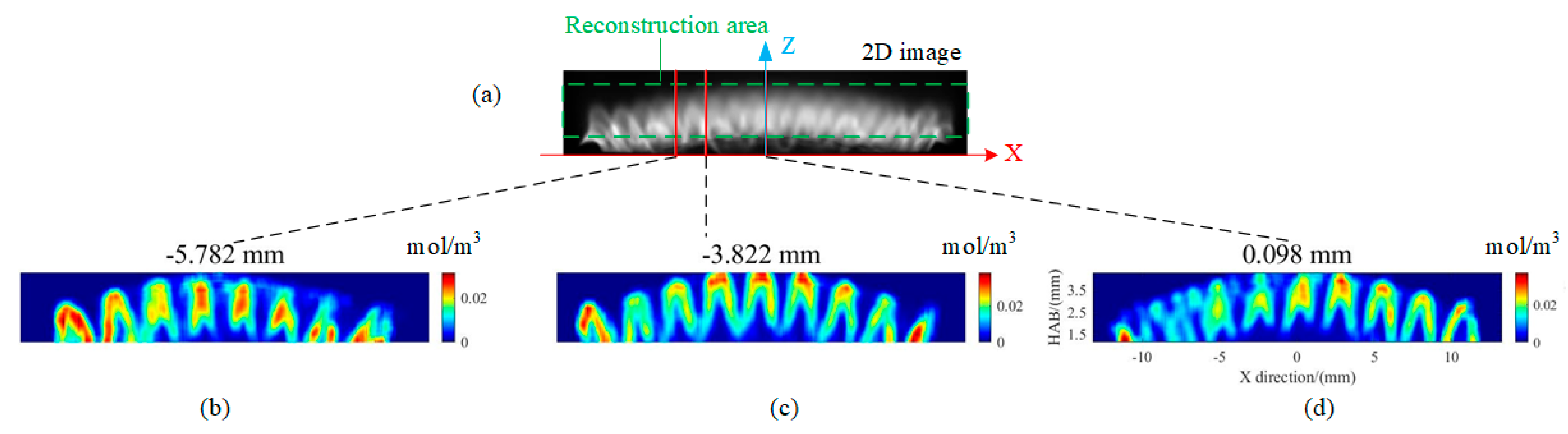

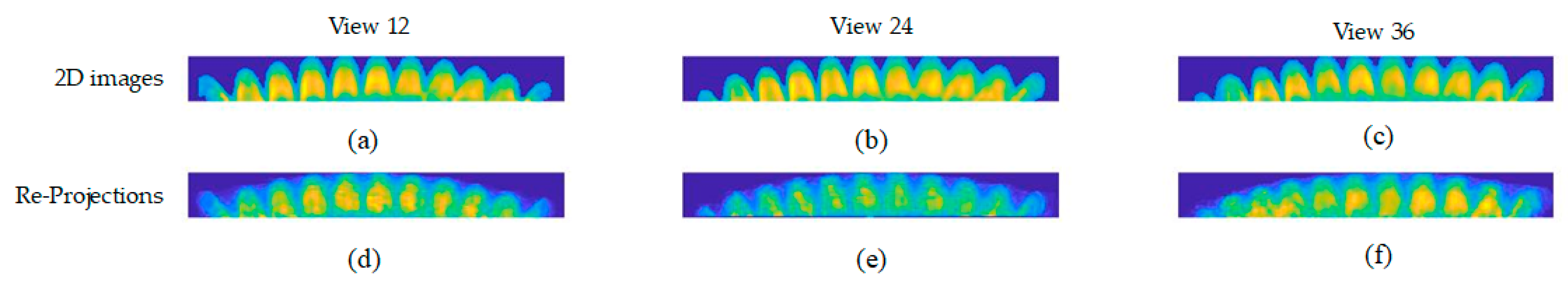

4.1. Reconstruction Results

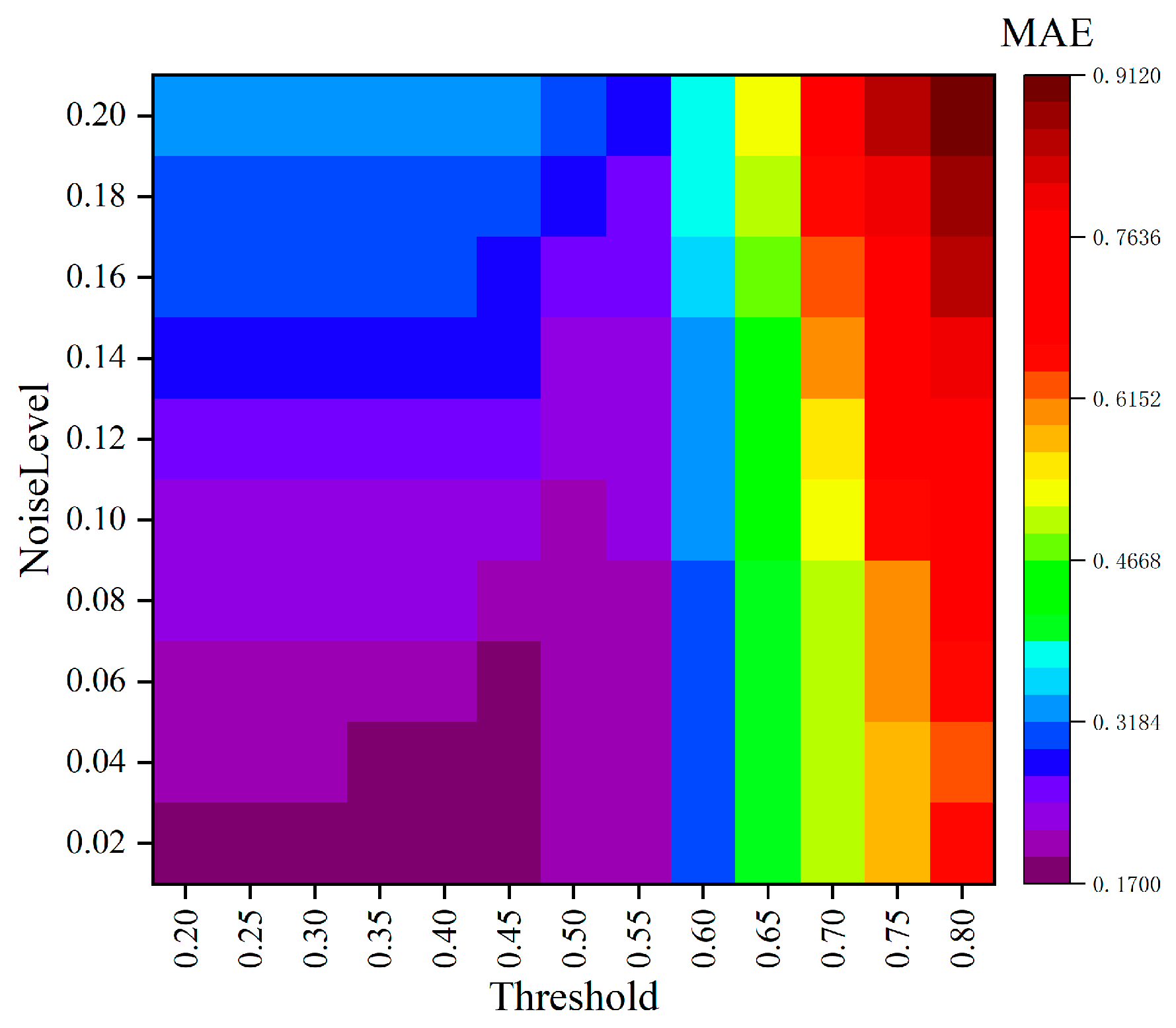

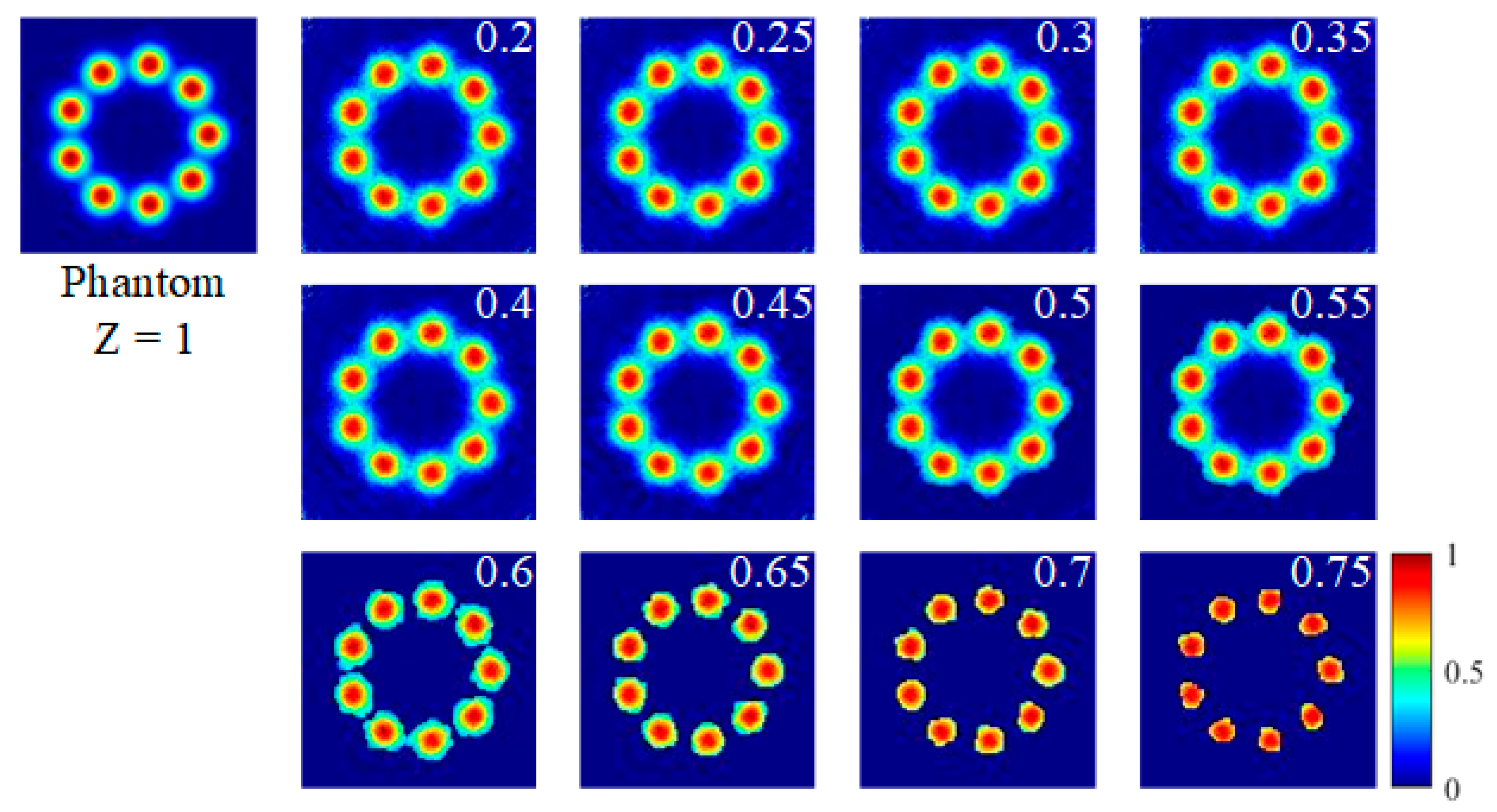

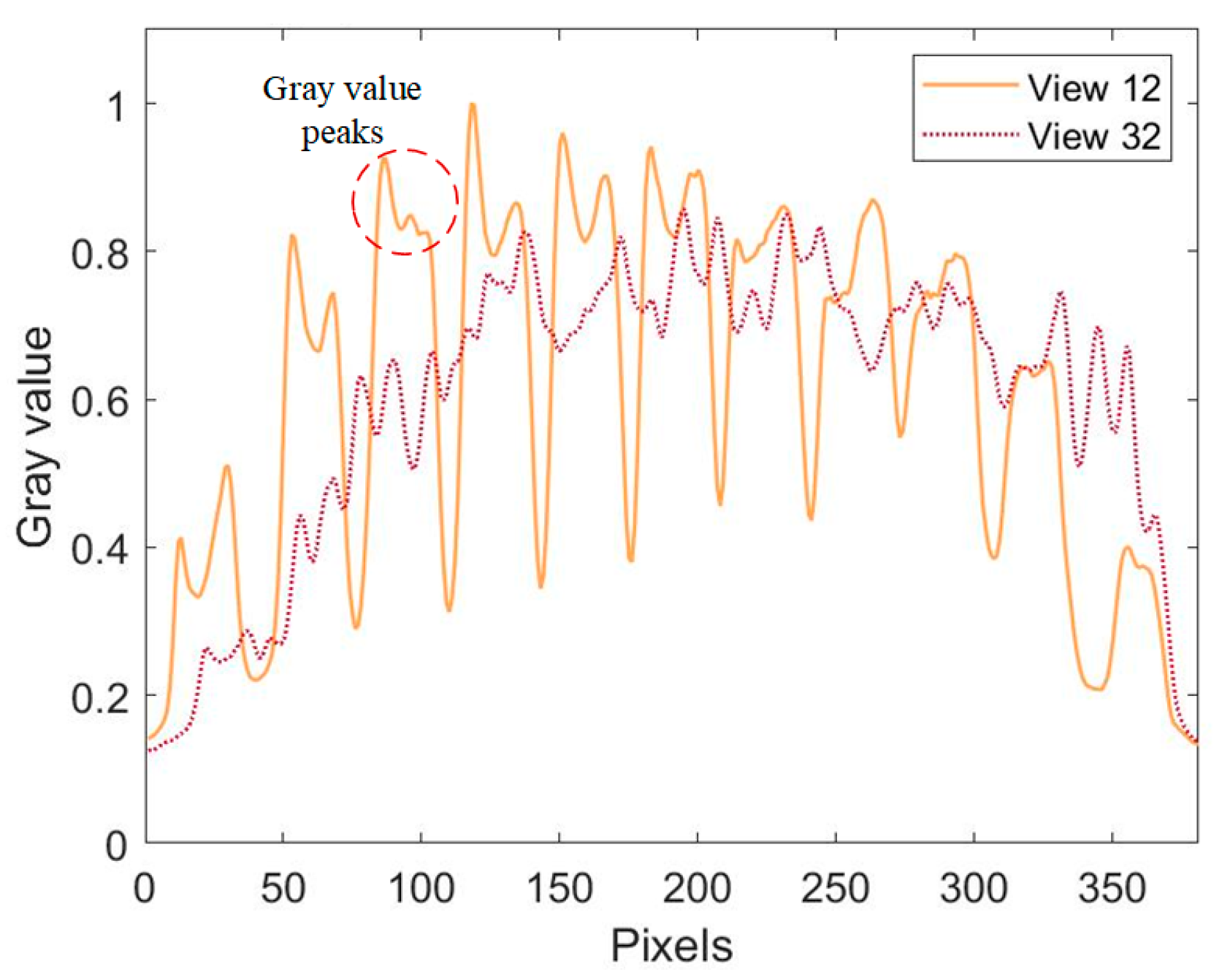

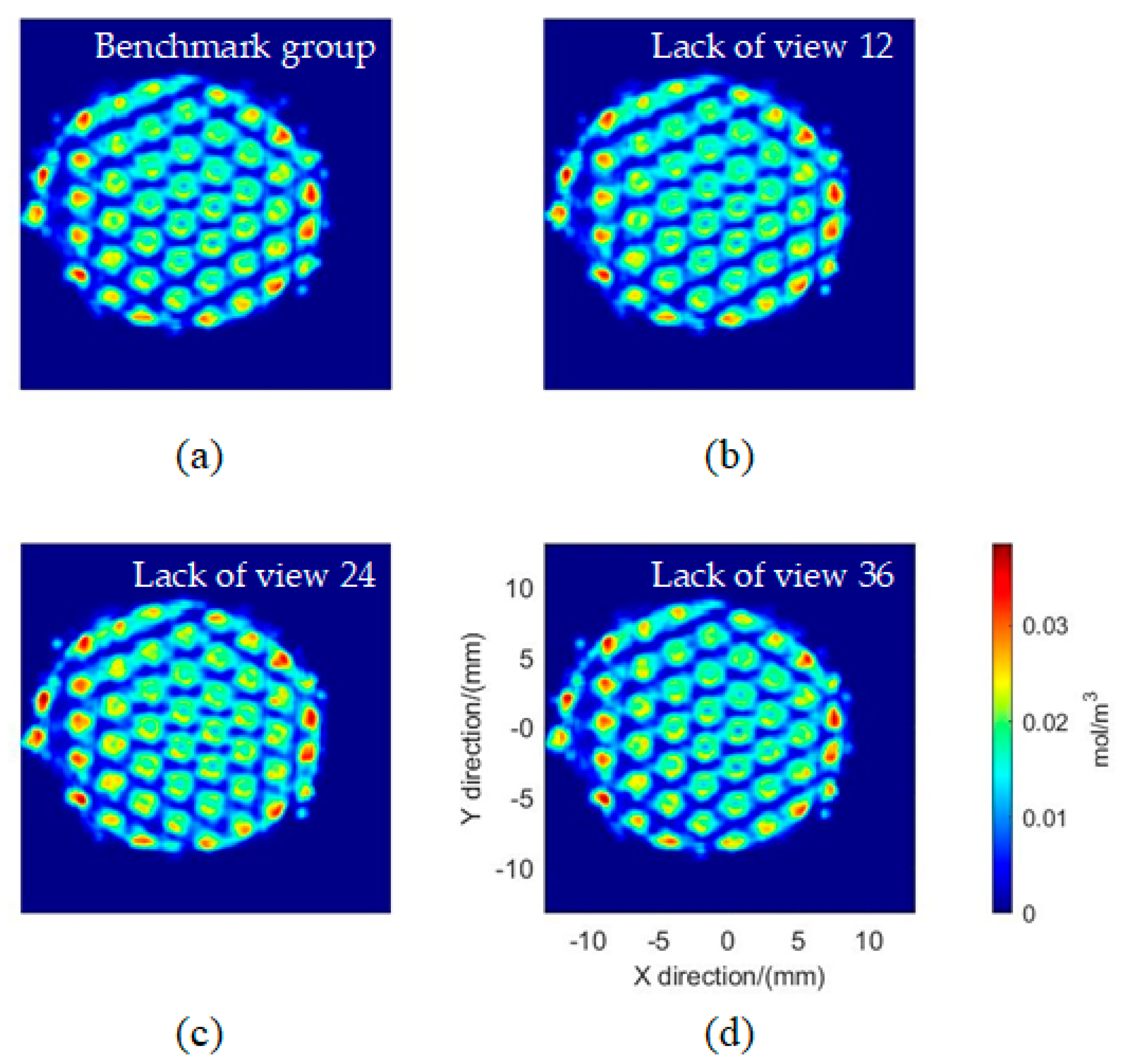

4.2. The Evaluation of Flame Reconstruction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| View Numbers | 9 | 18 | 36 |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | 0.1548 | 0.0925 | 0.0629 |

| CC | 0.9890 | 0.9959 | 0.9982 |

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.3

Appendix B

Appendix B.1

| Instruments | Spectral Range (nm) | Relative Uncertainty (Urel) /Accuracy Class (k) | Certificate Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| White board | 250–2500 | 250–380 nm, 780–2500 nm: Urel = 1.0% (k = 2); 380–780 nm: Urel = 0.44% (k = 2) | GXcl2023–08027 |

| Spectral irradiance standard lamp | 250–2500 | 250–400 nm: Urel = (3.0–1.3)% (k = 2); 400–800 nm: Urel = (1.3–1.2)% (k = 2); 800–2500 nm: Urel = (1.2–3.5)% (k = 2) | GXfs2024–00332 |

Appendix B.2

References

- Abdin, Z.; Zafaranloo, A.; Rafiee, A.; Mérida, W.; Lipiński, W.; Khalilpour, K.R. Hydrogen as an Energy Vector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesmana, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhu, M.; Xu, W.; Zhang, D. NH3 as a Transport Fuel in Internal Combustion Engines: A Technical Review. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2019, 141, 070703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Liu, J.; Zhao, C.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z. Research on Pre-Ignition in Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engines Based on Characteristic Parameters of Hot Spot. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 65, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhyani, V.; Subramanian, K. Fundamental Characterization of Backfire in a Hydrogen Fuelled Spark Ignition Engine Using CFD and Experiments. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 32254–32270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera-Medina, A.; Marsh, R.; Runyon, J.; Pugh, D.; Beasley, P.; Hughes, T.; Bowen, P. Ammonia–Methane Combustion in Tangential Swirl Burners for Gas Turbine Power Generation. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 1362–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; An, Z.; Wei, X.; Wang, J.; Huang, Z.; Tan, H. Emission Analysis of the CH4/NH3/Air Co-Firing Fuels in a Model Combustor. Fuel 2021, 291, 120135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Khateeb, A.A.; Roberts, W.L.; Guiberti, T.F. Chemiluminescence Signature of Premixed Ammonia-Methane-Air Flames. Combust. Flame 2021, 231, 111508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, F.G.; Aniello, A.; Riber, E.; Schuller, T.; Laera, D. On the Adequacy of OH as Heat Release Marker for Hydrogen–Air Flames. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2024, 40, 105248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Kaminski, C.F. Tomographic Absorption Spectroscopy for the Study of Gas Dynamics and Reactive Flows. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2017, 59, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panoutsos, C.S.; Hardalupas, Y.; Taylor, A.M.K.P. Numerical Evaluation of Equivalence Ratio Measurement Using OH* and CH* Chemiluminescence in Premixed and Non-premixed Methane-air Flames. Combust. Flame 2009, 156, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, M.; Zellhuber, M.; Sattelmayer, T.; Aul, C.J. Determination of the Heat Release Distribution in Turbulent Flames by a Model Based Correction of OH* Chemiluminescence. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2011, 133, 121501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Situ, G. A Survey for 3D Flame Chemiluminescence Tomography: Theory, Algorithms, and Applications. Front. Photonics 2022, 3, 845971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauer, S.J.; Mohri, K.; Yu, T.; Liu, H.; Cai, W. Volumetric Emission Tomography for Combustion Processes. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2022, 94, 101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Tan, J.; Hu, Y. Numerical and Experimental Investigation of Computed Tomography of Chemiluminescence for Hydrogen--Air Premixed Laminar Flames. Int. J. Aerospace Eng. 2016, 2016, 6938145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häber, T.; Suntz, R.; Bockhorn, H. Two-Dimensional Tomographic Simultaneous Multispecies Visualization—Part II: Reconstruction Accuracy. Energies 2020, 13, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Worth, N.; Dawson, J.R. Tomographic Reconstruction of OH* Chemiluminescence in Two Interacting Turbulent Flames. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2012, 24, 024013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Parajuli, P.; Wang, Y.; Kulatilaka, W.D. Hydroxyl Radical Planar Laser-Induced Fluorescence Imaging in Flames Using Frequency-Tripled Femtosecond Laser Pulses. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 4690–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nau, P.; Krüger, J.; Lackner, A.; Letzgus, M.; Brockhinke, A. On the Quantification of OH*, CH*, and C2* Chemiluminescence in Flames. Appl. Phys. B Laser Opt. 2012, 107, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anikin, N.B.; Suntz, R.; Bockhorn, H. Tomographic Reconstruction of 2D-OH∗-chemiluminescence Distributions in Turbulent Diffusion Flames. Appl. Phys. B Laser Opt. 2012, 107, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Song, Y.; Qu, X.; Li, Z.; Ji, Y.; He, A. Three-dimensional Dynamic Measurements of CH* and C2* Concentrations in Flame Using Simultaneous Chemiluminescence Tomography. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 4640–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Li, Z.-H.; Kempf, A.; He, A.-Z. Multi-Directional 3D Flame Chemiluminescence Tomography Based on Lens Imaging. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 1231–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe, J.; Peluso, S.; Szedlmayer, M.; De Rosa, A.; Quay, B.; Santavicca, D. 3-D Chemiluminescence Imaging of Unforced and Forced Swirl-Stabilized Flames in a Lean Premixed Multi-Nozzle Can Combustor. In Proceedings of ASME Turbo Expo 2013: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, San Antonio, TX, USA, 3–7 June 2013; p. V01BT04A053. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Buttsworth, D.; Choudhury, R. Experimental and Numerical Study of OH* Chemiluminescence in Hydrogen Diffusion Flames. Combust. Flame 2018, 197, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, J.; Wan, M.; Zhang, L.; Yao, X. Quantitative Measurement of OH* and CH* Chemiluminescence in Jet Diffusion Flames. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 15922–15930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, J.; Kempf, A. Computed Tomography of Chemiluminescence (CTC): High Resolution and Instantaneous 3-D Measurements of a Matrix Burner. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2011, 33, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, F.; Zeng, H.; Yu, X. Three-Dimensional Flame Measurements with Large Field Angle. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 21008–21018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.H.; Kak, A.C. Simultaneous Algebraic Reconstruction Technique (SART): A Superior Implementation of the Art Algorithm. Ultrason. Imaging 1984, 6, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.J.; Xu, L.A. Ultrasound Tomography System Used for Monitoring Bubbly Gas/Liquid Two-Phase Flow. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 1997, 44, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Lu, G.; Yan, Y. Optical Fiber Imaging Based Tomographic Reconstruction of Burner Flames. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2012, 61, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Q.; Peng, F.; Qin, Z.; Cai, W. Flame Emission Tomography Based on Finite Element Basis and Adjustable Mask. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 40841–40853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Peng, F.; Cai, W. A Reconstruction Method for Volumetric Tomography Within Two Parallel Transparent Plates. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 169, 107699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Z.; Tan, J.; Sun, M.; Cai, Z.; Liu, Y. Combustion Characteristics of a Confined Turbulent Jet Flame. Fuel 2022, 323, 124228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gong, Y.; Wei, J.; Guo, Q.; Wang, F.; Yu, G. Chemiluminescence Diagnosis of Oxygen/Fuel Ratio in Fuel-Rich Jet Diffusion Flames. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 232, 107284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yu, T.; Zhang, M.; Cai, W. Demonstration of 3D Computed Tomography of Chemiluminescence with a Restricted Field of View. Appl. Opt. 2017, 56, 7107–7115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sensitivity Range | Pixel Size | Highest Resolution | Quantum Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 200–1000 nm | 11 μm × 11 μm | 1200 × 1200 | 35%@310 nm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, D.; Zheng, D.; Kang, G.; Cai, Y. OH* 3D Concentration Measurement of Non-Axisymmetric Flame via Near-Ultraviolet Volumetric Emission Tomography. Sensors 2026, 26, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010009

Ma J, Wang L, Chen D, Zheng D, Kang G, Cai Y. OH* 3D Concentration Measurement of Non-Axisymmetric Flame via Near-Ultraviolet Volumetric Emission Tomography. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Junhui, Lingxue Wang, Dongqi Chen, Dezhi Zheng, Guoguo Kang, and Yi Cai. 2026. "OH* 3D Concentration Measurement of Non-Axisymmetric Flame via Near-Ultraviolet Volumetric Emission Tomography" Sensors 26, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010009

APA StyleMa, J., Wang, L., Chen, D., Zheng, D., Kang, G., & Cai, Y. (2026). OH* 3D Concentration Measurement of Non-Axisymmetric Flame via Near-Ultraviolet Volumetric Emission Tomography. Sensors, 26(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010009