Abstract

The Internet of Drones (IoD) is an emerging industry that offers convenient services for humans due to the high mobility and flexibility of drones. The IoD substantially enhances human life by enabling diverse drone applications across various domains. However, a malicious adversary can attempt security attacks because communication within an IoD environment is conducted through public channels and because drones are vulnerable to physical attacks. In 2023, Sharma et al. proposed a physical unclonable function (PUF)-based authentication and key agreement (AKA) scheme for the IoD. Regrettably, we discover that their scheme cannot prevent impersonation, stolen verifier, and ephemeral secret leakage (ESL) attacks. Moreover, Sharma et al.’s scheme cannot preserve user untraceability and anonymity. In this paper, we propose a secure and lightweight AKA scheme which addresses the shortcomings of Sharma et al.’s scheme. The proposed scheme has resistance against diverse security attacks, including physical capture attacks on drones, by leveraging a PUF. Furthermore, we utilize lightweight operations such as hash function and XOR operation to accommodate the computational constraints of drones. The security of the proposed scheme is rigorously verified, utilizing “Burrows–Abadi–Needham (BAN) logic”, “Real-or-Random (ROR) model”, “Automated Validation of Internet Security Protocols and Application (AVISPA)”, and informal analysis. Additionally, we compare the security properties, computational cost, communication cost, and energy consumption of the proposed scheme with other related works to evaluate performance. As a result, we determine that our scheme is efficient and well suited for the IoD.

1. Introduction

The “Internet of Drones (IoD)” [1] is considered as a prominent industry that is shaping the future of human life through the diverse applications and capabilities of drones. With their high mobility and flexibility, drones are ideally suited for performing tasks across various domains [2]. Drones provide effective alternatives for performing tasks that are labor-intensive or challenging for human operators. The IoD is a network architecture which coordinates drone access and manages their operations within the Internet [3]. Generally, the IoD architecture consists of a control station server (CSS), drones, and remote users. The CSS acts as the control center, overseeing drone operations to ensure appropriate functionality and facilitating communication between drones and remote users. Drones are equipped with various sensors, computational capabilities, and communication modules and can connect to a CSS via the Internet to execute a range of tasks [4]. Drones can be deployed in various environments and provide a wide range of services, including traffic monitoring, aerial photography, delivery, rescue, and surveillance [5]. Drones collect the surrounding data and transmit them to a CSS or share it with remote users through CSS arbitration [6]. This interconnected structure enables drones to offer convenient services to remote users who benefit from enhanced functionality.

Although the IoD presents various advantages for enhancing human life, it still encounters several critical challenges requiring resolution. In the IoD architecture, communication between drones, remote users, and the CSS occurs through public channels [7]. This exposes the IoD system to potential attacks comprising replay, eavesdropping, insider, and man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks [8,9]. Additionally, drones are susceptible to unauthorized physical access as they operate in open airspace [10]. A malicious attacker can hijack or physically capture a drone to obtain sensitive data and attempt to disrupt drone operation by injecting malicious payloads. Such breaches can compromise user privacy and lead to substantial security risks. To address these vulnerabilities, various security technologies have been proposed for IoD environments, such as intrusion detection system and anti-jamming [11,12,13]. In this paper, we focus on the authentication and key agreement (AKA) to preserve privacy, determinate identity of network participants, and establish secure communication channels between users and drones. Another pressing challenge is lightweight computation for drones. Drones have limitations of processing capabilities and database capacity [14], which makes them differ from a CSS, which operates in environments with abundant computing power and storage. Computations are completed within a constrained timeframe to eliminate time delay as the IoD services rely on real-time operation. As a result, it is indispensable to design a secure and lightweight AKA scheme for the IoD in order to guarantee efficient performance while maintaining data security and computational efficiency.

In recent years, various AKA schemes have been proposed to provide security for IoD environments [15,16,17,18]. However, such schemes suffer from challenges in lightweight operation and resistance to security vulnerabilities, including physical attacks, which are important issues in IoD environments. To overcome these vulnerabilities, Sharma et al. [19] proposed a physical unclonable function (PUF)-based AKA scheme for the IoD in 2023. Their scheme considered the computational limitations of drones by employing the hash function, exclusive-OR (XOR), and PUF. Sharma et al. argued that their scheme defends numerous adversarial attacks, including privileged insider, MITM, replay, and drone capture attacks. Unfortunately, we demonstrate that their scheme cannot prevent impersonation, stolen verifier, and ephemeral secret leakage (ESL) attacks. Specifically, the session key shared by the user and the drone is exposed by an adversary, compromising mutual authentication. Furthermore, their scheme fails to guarantee user untraceability and anonymity. Therefore, we propose a robust and secure AKA scheme that addresses the flaws of Sharma et al.’s scheme. The proposed scheme defends diverse attacks containing drone capture, impersonation, stolen verifier, and ESL attacks. Moreover, the proposed scheme adopts a PUF that is similar to the approach utilized in Sharma et al.’s scheme. Drones can generate a secret key masked with “challenge–response” pair and protect the data stored in their memory using the key. The proposed scheme achieves enhanced security mitigating the security shortcomings of Sharma et al.’s scheme. Our scheme effectively prevents various security threats including impersonation, stolen verifier, and ESL attacks while introducing additional security properties. Moreover, the proposed scheme achieves a better balance between security and cost efficiency. Compared to Sharma et al.’s scheme, our scheme offers improved security without compromising performance or practicality.

1.1. Contributions

This study offers the following major contributions:

- We analyze Sharma et al.’s scheme and indicate the security weaknesses related to impersonation, stolen verifier, and ESL attacks of their scheme. Furthermore, we demonstrate that their scheme does not guarantee mutual authentication, user untraceability, and anonymity.

- We suggest a lightweight and secure AKA scheme to mitigate the drawbacks of Sharma et al.’s scheme. The proposed scheme adopts one-way hash functions and XOR operations, which are suitable for drones with limited computing power. Additionally, we incorporate a PUF to manage the data stored in drones securely and prevent unauthorized accesses to drones.

- We demonstrate that our scheme ensures the robustness against numerous attacks by performing informal analysis. Moreover, we conduct “Burrows–Abadi–Needham (BAN) logic”, “Real-or-Random (ROR) model”, and “Automated Validation of Internet Security Protocols and Application (AVISPA)”, which represent the resilience of our scheme formally.

- We prove that our scheme achieves cost efficiency with respect to computational cost, communication cost, and energy consumption by conducting a comparison between the proposed scheme and other relevant schemes.

1.2. Organization

We discuss associated studies for the IoD in Section 2. We provide an explanation of the IoD architecture model, adversary model, and the properties of a PUF in Section 3. We revisit Sharma et al.’s scheme in Section 4. We conduct a cryptanalysis of Sharma et al.’s scheme to verify that their scheme has security vulnerabilities in Section 5. We propose a secure and cost-effective AKA scheme for the IoD, which remedies the flaws identified in Sharma et al.’s scheme in Section 6. We assess the resilience of the proposed AKA scheme by adopting various examination methods in Section 7. We highlight the robustness and efficiency through a comparative analysis between the proposed and relevant schemes in Section 8. Finally, we wrap up our study with concluding remarks in Section 9.

2. Related Works

The IoD is a rapidly growing industry that attracts significant attention, prompting researchers to develop AKA schemes for secure IoD communication. In 2021, Nikooghadam et al. [20] devised an AKA scheme for smart city surveillance to construct secure communication between user and drone. They used elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) to enhance energy costs more than traditional public-key cryptosystems (e.g., RSA). Unfortunately, Alzahrani et al. [21] indicated that Nikooghadam et al.’s scheme cannot defend stolen verifier and insider attacks, and that it also lacks user anonymity and untraceability. They proposed an AKA scheme between a user and drone that addresses the security vulnerabilities of Nikooghadam et al.’s scheme. However, their scheme still suffers from security attacks, including drone capture and insider attacks, and cannot ensure security properties, including user anonymity, message integrity, and confidentiality [22]. Tanveer et al. [23] presented an AKA protocol for the IoD environment using ECC. They utilized AEGIS and ECC to enhance their scheme. However, the scheme cannot prevent impersonation and drone capture attacks [24]. Dwivedi et al. [25] propounded a data delivery AKA scheme for tactile Internet-enabled IoD. Their scheme employs ECC and blockchain, providing security for various attacks. It also provides user anonymity, unlinkability, and data immutability. However, previously proposed schemes [20,21,23,25] use ECC, which involves high-complexity computation unsuitable for drones. Because drones are constraint with regard to their computing power, a lightweight authentication protocol is required for the IoD.

Therefore, many researchers have focused on designing protocols with lightweight computational overhead. Ali et al. [26] devised a biometric-based AKA scheme between user and drone for smart city surveillance. Their scheme used lightweight operations such as hash function, XOR operation, and symmetric encryption. Regrettably, the scheme has weaknesses related to server session key disclosure, spoofing, and forgery attacks [27]. Chaudhary et al. [28] designed an anonymous AKA scheme for the IoD. Their scheme uses only an XOR operation and a one-way hash function for computational efficiency. Unfortunately, their scheme is vulnerable to user impersonation attacks and cannot preserve user privacy protection. Lee et al. [29] propounded a lightweight AKA protocol for the IoD using a one-way hash function and an XOR operation. Although they assert that their scheme rectifies the vulnerabilities of Chaudhary et al.’s scheme and is resistant against numerous attacks, it is still susceptible to the physical attacks of drones. Hussain et al. [30] also presented a lightweight authentication protocol for the IoD environment using symmetric encryption, a one-way hash function, and an XOR operation. The analysis of their scheme shows that it can prevent various attacks. However, it cannot defend against impersonation attacks and physical attacks on drones. Pratap et al. [15] suggested an AKA scheme between a user and a drone for the IoD that addresses the resource limitation issue of drones by utilizing hyperelliptic curve cryptography (HECC). Unfortunately, their scheme is susceptible to drone capture attacks. Although all of these schemes [15,26,28,29,30] are computationally efficient, they exhibit security drawbacks, particularly a susceptibility to drone capture attacks.

To mitigate the risk of physical attack on drones, numerous researchers have carried out studies. Zhang et al. [16] propounded a key management scheme for the IoD. They considered restricted computing power and physical security issue of drones using a PUF and lightweight operations. Tanveer et al. [17] proposed a biometric-based AKA scheme securing information within the IoD infrastructure. They adopted a PUF, a hash function and symmetric encryption to provide secure communication between users and drones. Tanveer et al. [18] also devised a PUF-based authentication scheme, establishing a session key between users and drones. Using a PUF, a hash function, and AEGIS, their scheme addresses the susceptibility and resource constraints of drone communication. Sharma et al. [19] suggested a lightweight and physical attack-resistant AKA scheme for the IoD environment. Regrettably, we identified that Sharma et al.’s has limitations in defending user impersonation, stolen verifier, and ESL attacks. Moreover, user anonymity and untracability are not preserved in their scheme. Therefore, we propose a robust and lightweight AKA scheme to address the shortcomings in Sharma et al.’s scheme. Table 1 represents the summary of the related schemes.

Table 1.

Summary of the proposed scheme and related schemes.

3. Preliminaries

In this part, we explain essential concepts and background for a comprehensive understanding of the proposed scheme. We describe the system model, adversary model and the PUF.

3.1. System Model

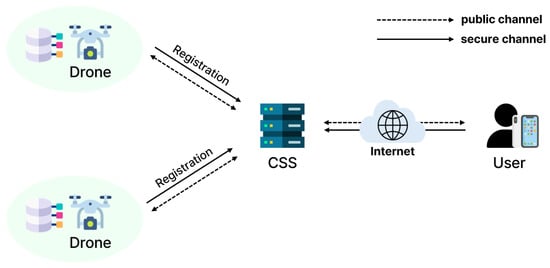

Figure 1 illustrates the IoD architecture. There are three entities in the proposed system model: control station server (CSS), remote users, and drones. These entities communicate through wireless channels.

Figure 1.

System model for the IoD.

- The CSS is a fully trusted entity. The CSS possesses abundant resources and extensive memory capabilities for controlling system networks. First, the CSS initializes the entire system and registers users and drones. Sensitive data related to users and drones and the information collected by drones are stored in its database. Users and drones authenticate with the mediation of the CSS.

- Remote users need to authenticate with the CSS to access the data stored in the CSS and utilize convenient services. After mutual authentication support from the CSS, users also can directly access the real-time information gathered by drones.

- Drones are deployed in open airspace and gather surrounding information. The information collected by drones is transmitted to the CSS for further processing. PUFs which are embedded in drones protect the secret parameters stored in drones. If a drone is captured, the PUF will be unusable and authentication with the user or the CSS cannot be completed. Additionally, drones have limited resources and memory capabilities.

3.2. Adversary Model

In this paper, we evaluate the security of AKA scheme by adopting the widely operated threat models “Dolev-Yao (DY)” [31] and “Canetti-Krawczyk (CK)” [32]. The DY and CK models provide the assumptions used to characterize the potential of an adversary. A malicious adversary can delete, insert, eavesdrop, revise, and re-transmit messages sent through a public channel. Moreover, can obtain and expose session state and temporary session keys or the master key of the CSS. Based on following assumptions, we assess the security of the proposed scheme.

- can steal a smart device of a remote user and and use power analysis attacks to retrieve secret credentials stored in the device [33,34].

- can be a legitimate user of the system or an outsider and can attempt various attacks using obtained information.

- can steal the verification table stored in the CSS and can attempt various attacks using obtained information.

- can attempt a variety of attacks, including MITM, privileged insider, replay, and impersonation attacks.

3.3. Physical Unclonable Function

The microstructure of the hardware exhibits unique physical deviations generated by manufacturing disparities. The PUF depends on the characteristic property of the microstructure. The PUF can be considered as fingerprint of the hardware. A PUF includes a unique input–output pair called the “challenge–response” pair. We can use a unique response for authentication and key generation. In this paper, we illustrate the operation of a PUF as . The notation C indicates a challenge and R indicates a response. We describe the attributes of the PUF as follows:

- A PUF is an unclonable circuit. It is impossible for any to satisfy .

- While can be computed easily, determining R for a given C within polynomial time is computationally infeasible.

- The output of a PUF is unpredictable [35].

In the proposed scheme, we adopt a PUF to prevent unauthorized physical accesses on drones and protect secret information stored in their memory. Drones can use PUF responses as a secret key using its uniqueness.

4. Review of Sharma et al.’s Scheme

An overview of Sharma et al.’s scheme is provided here. Table 2 summarizes the key notations utilized in Sharma et al.’s scheme. The following outlines its details:

Table 2.

Notations.

4.1. Initialization Phase

Initially, the CSS chooses its identity , a secret key , and a one-way hash function . Then, the CSS calculates a pseudo-identity and publishes and .

4.2. Drone Registration Phase

- Step 1:

- picks its identity and a challenge C, and computes . Then, sends to the CSS through a secure channel.

- Step 2:

- The CSS calculates after receiving the message and stores in the database. Then, the CSS transmits to securely.

- Step 3:

- saves to a database.

4.3. User Registration Phase

- Step 1:

- selects and . Then, transmits to the CSS securely.

- Step 2:

- The CSS computes and upon receiving the message. The CSS sends to through a secure channel after storing in the database.

- Step 3:

- calculates and . Finally, stores .

4.4. Authentication and Key Agreement Phase

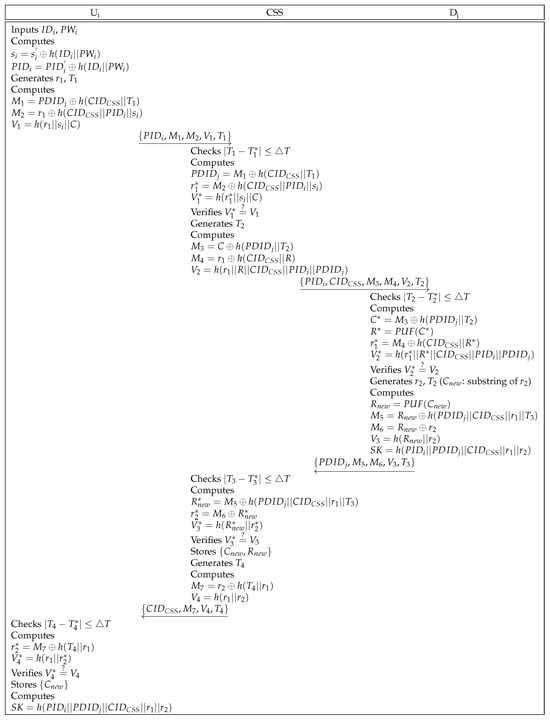

First, the user transmits an authentication request message to the CSS. The CSS mediates between the user and the drone , verifying whether and are legitimate or not. Finally, and share a session key for establishing secure communication. Figure 2 indicates the processes of authentication and key agreement.

Figure 2.

Authentication and key agreement phase of Sharma et al.’s scheme.

- Step 1:

- inserts identity and password , and computes , and . Then, generates a random number and timestamp and calculates , , and . Further, sends the message to the CSS through an open channel.

- Step 2:

- The CSS first checks whether is valid or not. If it is valid, the CSS retrieves against and computes , , and . Then, the CSS verifies that is equal to . If they are identical, the CSS generates a timestamp , and calculates , , and . The CSS transmits over a public channel.

- Step 3:

- verifies the legitimacy of . If it is legitimate, computes , , , and . Then, checks whether and are equal or not. After checking the equality, generates a random number and a timestamp . is a substring of . After that, calculates , , , , and , and sends to the CSS through a public channel.

- Step 4:

- The CSS checks the validity of . If it is valid, the CSS calculates , , and . Further, the CSS compares with . If they are equal, the CSS stores in the database and generates a timestamp . The CSS computes and , and transmits to .

- Step 5:

- verifies that is legitimate. If legitimate, computes and . Then, checks that is equal to . If they are equal, stores and establishes the session key .

5. Cryptanalysis of Sharma et al.’s Scheme

Cryptanalysis is conducted to indicate that Sharma et al.’s scheme cannot prevent impersonation, stolen verifier, ESL attacks and cannot ensure user anonymity and untraceability. The detailed steps are outlined as follows:

5.1. User Impersonation Attack

A malicious adversary impersonates a legitimate user using the secret parameters extracted from user’s smart device. Then, establishes a session key with a drone. The details are outlined below.

- Step 1:

- can exploit a power analysis attack to extract the secret information stored on the user’s smart device, under the assumptions described in Section 3.2.

- Step 2:

- eavesdrops on transmitted through a public channel and obtains . Then, can calculate .

- Step 3:

- generates a number randomly and a timestamp , and calculates the request messages , , and .

- Step 4:

- The CSS receives the request message and delivers the random number of to . Then, computes a session key and transmits to the CSS.

- Step 5:

- The CSS authenticates and sends the message to . Finally, obtains and computes .

5.2. Stolen Verifier Attack

Under the CK model, can access the verification table stored in the database of the CSS. Further, can access the pseudo-identities of each of and entities, because they are transmitted through an open channel and not updated. To compute the session key between and , calculates and , where and are sent through an open channel. Finally, can obtain the session key .

5.3. Ephemeral Secret Leakage Attack

In Sharma et al.’s scheme, and establish a session key using the pseudo-identities of each entity and the random numbers generated by and . Therefore, if gains those values, can calculate the session key shared between and . Under the CK model, can acquire the ephemeral random numbers generated during a session. Furthermore, can eavesdrop on the pseudo-identities sent through an open channel. As a result, can derive the session key .

5.4. User Anonymity and Untraceability

can eavesdrop the message sent through a public channel in accordance with the adversary model described in Section 3.2. In the AKA phase of Sharma et al.’s scheme, and the CSS transmit through a public channel. At the end of the AKA phase, they do not update . Therefore, Sharma et al.’s scheme lacks the ability to preserve user untraceability and anonymity.

6. Proposed Scheme

Here, we detail our AKA scheme for the IoD, designed with PUF technology. The proposed scheme comprises the following phases: (1) initialization, (2) registration, (3) authentication and key agreement, and (4) password update. Users and drones register themselves to the CSS and share a session key with arbitration of the CSS. Detailed steps are outlined as follows.

6.1. Initialization

The CSS selects as a one-way hash function, along with a secret key and an identity . Then, the CSS publishes .

6.2. Drone Registration Phase

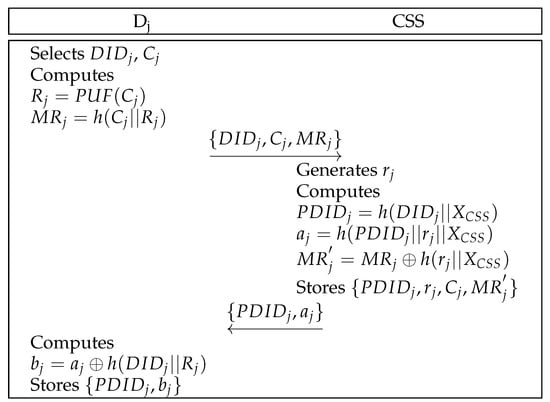

A drone registers itself with the CSS before authentication. Figure 3 represents the procedures of drone registration. Details are outlined below.

Figure 3.

Drone registration of the proposed scheme.

- Step 1:

- chooses its identity and a challenge C, and computes and . Then, sends to the CSS securely.

- Step 2:

- The CSS generates a random number , and calculates , , and after receiving the message. Then, the CSS stores in a database and transmits to securely.

- Step 3:

- computes , and saves to a database.

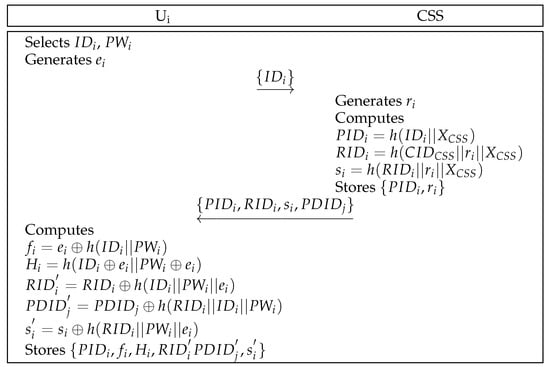

6.3. User Registration Phase

A user registers themselves with the CSS before authentication. Figure 4 shows the comprehensive steps of user registration. The following steps outline the details of this process.

Figure 4.

User registration of the proposed scheme.

- Step 1:

- First, selects an identity and a password . Further, generates a number randomly and transmits to the CSS securely.

- Step 2:

- Upon receiving the message, the CSS generates a number randomly and calculates , , and . The CSS sends to through secure channel after it stores in the database.

- Step 3:

- calculates , , , , and . Finally, stores in the database.

6.4. Authentication and Key Agreement Phase

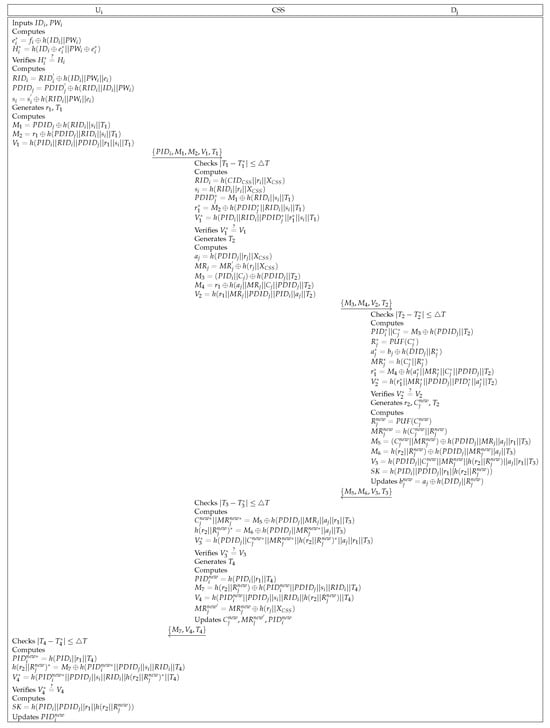

Authentication between and is established in this phase. After the authentication, they share a session key with the mediation of the CSS. Figure 5 depicts the details of the AKA phase.

Figure 5.

Authentication and key agreement phase of the proposed scheme.

- Step 1:

- inserts his/her identity and password , and computes and . Then, compares whether and are equal or not. If they are equal, login is completed. calculates , , and . Then, selects a random number and a timestamp , and calculates , , and . Further, sends a message to the CSS through an open channel.

- Step 2:

- The CSS first checks whether is valid or not. If it is valid, the CSS retrieves against and computes , , , , and . Then, the CSS verifies that is equal to . If they are equal, the CSS generates a timestamp and retrieves against . Then, the CSS calculates , , , , and . The CSS transmits over a public channel.

- Step 3:

- verifies the legitimacy of . If it is legitimate, computes , , , , , and . Then, checks whether and are equal or not. If they are equal, generates a random number , a new challenge and a timestamp . After that, calculates , , , , , and , and sends to the CSS through a public channel.

- Step 4:

- The CSS checks the validity of . If it is valid, the CSS calculates , , and . Further, the CSS compares with . After checking the equality, the CSS generates a timestamp and computes , , , and . Then, the CSS transmits to and updates .

- Step 5:

- verifies that is legitimate. If it is legitimate, computes , and . Then, checks whether is equal to . If they are equal, updates and computes the session key .

6.5. Password Update Phase

- Step 1:

- inputs his/her identity and password , and computes and . Then, compares that and are equal or not. If they are equal, login is completed.

- Step 2:

- inserts new password . Then, calculates , , , , and . Finally, stores to the database.

7. Security Analysis

Here, we discuss the approach to verifying the resilience of the proposed scheme. To formally validate the robustness of our scheme, we employ “BAN logic”, “RoR model”, “AVISPA”, and informal analysis. The results demonstrate that our scheme effectively resists various attacks while ensuring critical security requirements comprising mutual authentication, user anonymity, and untraceability. Further details are provided below.

7.1. BAN Logic

BAN logic is regarded as a standard analytical approach which is utilized to substantiate formally whether mutual authentication is achieved in AKA schemes. It has been extensively utilized by researchers to demonstrate the mutual authentication of various protocols. In this section, we first introduce the key notations and foundational rules of BAN logic. Subsequently, BAN logic analysis is applied to the proposed scheme. The primary BAN logic notations used in this study are summarized in Table 3. Further details of the analysis are as follows:

Table 3.

Notations in BAN logic.

7.1.1. Rules

The fundamental BAN logic rules utilized in this paper are outlined below.

Message meaning rule (MMR):

Nonce verification rule (NVR):

Jurisdiction rule (JR):

Freshness rule (FR):

Belief rule (BR):

7.1.2. Idealized Forms

Idealized forms are defined as below.

- :

- :

- :

- :

7.1.3. Goals

The security goals used to verify the guarantee of mutual authentication comprise the following:

- Goal 1:

- Goal 2:

- Goal 3:

- Goal 4:

7.1.4. Assumptions

Assumptions are defined as follows:

- :

- :

- :

- :

- :

- :

- :

- :

- :

- :

- :

- :

7.1.5. Proof

The procedure for the proof is described as follows:

Step 1: According to , we can obtain .

Step 2: By applying and to the MMR, we can obtain .

Step 3: By applying to the FR, we can obtain .

Step 4: By applying and to the NVR, we can obtain .

Step 5: According to , we can obtain .

Step 6: By applying and to the MMR, we can obtain .

Step 7: By applying to the FR, we can obtain .

Step 8: By applying and to the NVR, we can obtain .

Step 9: According to , we can obtain .

Step 10: By applying and to the MMR, we can obtain .

Step 11: By applying to the FR, we can obtain .

Step 12: By applying and to the NVR, we can obtain .

Step 13: According to , we can obtain .

Step 14: By applying and to the MMR, we can obtain .

Step 15: By applying to the FR, we can obtain .

Step 16: By applying and to the NVR, we can obtain .

Step 17: We can obtain from , , and because the session key is .

Step 18: By applying and to the JR, we can obtain .

Step 19: We can obtain from , , and because the session key is .

Step 20: By applying and to the JR, we can obtain .

7.2. RoR Model

This section demonstrates the application of the RoR model to the proposed scheme. The RoR model is a well-known formal analysis that can verify whether an authentication protocol provides the semantic security of a session key [36,37,38]. Before explaining the application of the RoR model to the proposed scheme, we describe its basic concepts and notations. Under the RoR model, executes queries that can attempt both active and passive attacks to reveal the session key. We describe the queries executed by , as detailed below. We denote three participants—a user, a drone, and a CSS—as , , and , respectively. The notation is defined as a participant instance of a user, a drone, and a CSS.

- Execute (, , ): Using this query, eavesdrops on messages transmitted over a public channel among , , and .

- Send (, M): A message M can be transmitted to participant by to receive a response message.

- CorruptMD (): This query denotes smart device stolen attacks. can attempt to extract the secret parameters stored in a user’s smart device.

- Test (): Using this query, determines if the speculative session key is a real session key or a random string. A fair coin c is flipped at the beginning of this query. obtains when returns a real session key and when returns a random string. Otherwise, receives a null. is considered the winner of the game if can judge whether the value output by is the session key or a random string.

Theorem 1.

Consider to attempt to compromise the proposed scheme within polynomial time. Let denote the advantage that successfully distinguishes the session key from a random string. Consequently, we obtain the result of the advantage as follows:

and are defined as the output range of the PUF and the hash function . Additionally, and denote the number of and queries executed by , respectively.

Proof.

The semantic security of the session key is verified as demonstrated in a series of games . indicates the possibility that correctly distinguishes c in .

- : attempts an eavesdropping attack by conducting an query. Further, runs queries to determine if the acquired value is a session key or not. must know , , and to acquire the session key . However, these values cannot be obtained by eavesdropping attacks. This means that has no advantage to be gained through an query. Therefore, the probability of winning is equal to that of winning .

- : In this game, runs and queries to expose the session key. The transmitted messages can be modified by . However, should find a hash collision to win the game because all transmitted messages are masked by a one-way function . Therefore, the advantage that can gain at the end of is obtained based on the birthday paradox.

- : Similar to , runs and queries. Due to security properties of the PUF described in Section 3.3, cannot obtain an advantage after conducting .

- : In this game, conducts queries to extract the secret parameters from a user’s smart device, exploiting power analysis attacks. Further, aims to derive the session key . However, each parameter consists of a user’s identity and password . Therefore, should guess the identity and password simultaneously. We can induce the following equation by adopting Zipf’s law [39]:To win the game, has to guess the bit c after finishing all games. Because has no advantage in guessing c, we derive Equation (6).Equation (7) is obtained from Equations (1) and (2).Equation (8) is obtained based on Equations (6) and (7).Equation (9) is obtained using the triangle inequality of Equation (8).Finally, the result is obtained by multiplying Equation (9) by 2.Consequently, Theorem 1 is verified. □

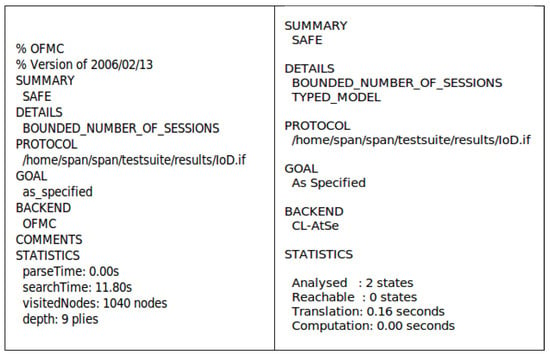

7.3. AVISPA Tool

This section presents the key data flow of AVISPA, highlighting the security verification of the proposed scheme. AVISPA is a widely accepted simulation tool used to prove whether a protocol is secure against replay attacks and MITM attacks. “High-Level Protocol Specification Language (HLPSL)” is a language used to execute a protocol in AVISPA based on a role. First, the HLPSL2IF translator converts the code written in HLPSL into an “Intermediate Format (IF)”. Then, AVISPA executes a simulation using four back-end models: “on-the-fly model checker (OFMC)”, “SAT-based model checker (SATMC)”, “constraint logic-based attack searcher (CL-AtSe)”, and “tree automata based on automatic approximations for the analysis of security protocols (TA4SP)”. If the IF is placed into the back-end by the translator, the back-end generates and summarizes the analysis result as an “output format (OF)”. An authentication protocol can resist MITM and replay attacks if the summary of OF represents “SAFE”.

In this paper, we use two back-ends, “OFMC” and “CL-AtSe”, for the AVISPA simulation of the proposed scheme. There are three roles (, , and ) in HLPSL, and we describe session and environment roles within those three roles. The secrecy of the secret parameter and the appropriateness of mutual authentication are checked in each session. Figure 6 represents the simulation results, showing that the summaries present “SAFE” using the “OFMC” and “CL-AtSe” back-end models. Hence, replay and MITM attacks cannot be successfully performed by .

Figure 6.

AVISPA simulation result under OFMC and CL-AtSe.

7.4. Informal Analysis

We analyze the proposed scheme informally to demonstrate the robustness related to numerous attacks. We also confirm that the proposed scheme achieves security requirements, including mutual authentication, perfect forward secrecy, user anonymity and untraceability.

7.4.1. Impersonation Attack

At the start of the AKA phase, transmits the request message to the CSS first. must compute the message to impersonate . Under the adversary model, can obtain the secret information stored in the smart device of . However, cannot compute because they are masked by . should guess and simultaneously to obtain . It is computationally infeasible. As a result, our scheme prevents impersonation attacks.

7.4.2. Stolen Verifier Attack

The CSS stores verification table in its database. According to the CK model, suppose that steals the verification table. After obtaining the verification table, can use the values to calculate the session key . However, cannot obtain the secret parameter without knowing the secret key . Although has , cannot calculate and . Thus, the proposed scheme can defend stolen verifier attacks.

7.4.3. Ephemeral Secret Leakage Attack

accesses to the ephemeral secrets and , which are generated by and in the AKA phase. Further, aims to acquire the session key . Even if obtains the random secrets and , still does not know and . cannot acquire and without the secret key and , which are masked by the master key of the CSS and the PUF response of . Hence, our scheme can resist against ESL attacks.

7.4.4. Replay Attack

All the messages are hashed with timestamps during the AKA phase of the proposed scheme. Even if intercepts a message transmitted through an open channel and tries to resend the message, cannot reuse the message because each entity verifies the validity of the timestamp in every session. If a timestamp is not in a legitimate range, authentication will fail. Hence, the proposed scheme can defend replay attacks.

7.4.5. Man-in-the-Middle Attack

After intercepting the message that or transmit to the CSS, generates a random number and a timestamp, and attempts to modify the message to send another valid message. However, cannot calculate the message because does not know the secret parameters and shared between and the CSS. Since and are masked by the master key of the CSS and stored in a user’s smart device securely, cannot obtain them. In a similar way, also cannot compute the message due to the secrecy of . Therefore, our scheme is resistant to MITM attacks.

7.4.6. Privileged Insider Attack

The registration request message of , can be intercepted by a privileged adversary . Then, attempts to obtain the secret values and using . Even if obtains , cannot calculate and because they are hashed with the master key of the CSS . Each of the parameters necessary for calculating the session key are encrypted with and . Therefore, cannot successfully defend against privileged insider attacks.

7.4.7. Drone Capture Attack

can attempt to derive the session key after intercepts a drone and extracts the information . However, cannot obtain the session key due to the secure property of the PUF. must obtain and to calculate the session key. However, these values are masked by the PUF response . It is impossible to compute for . Additionally, the proposed scheme updates to in every session. Thus, our scheme is robust to drone capture attacks.

7.4.8. Mutual Authentication

, and the CSS verify the legitimacy of the message during the AKA phase. The CSS and authenticate each other by checking that is equal to and is equal to . Similarly, the CSS and authenticate each other by verifying whether and are equal or not, and whether and are equal or not. If the values are not identical, the authentication process is terminated. and mutually authenticate each other and share a session key through CSS arbitration. Hence, mutual authentication is preserved in the proposed scheme.

7.4.9. User Anonymity and Untraceability

The identity of is transmitted through a secure channel one time when registers itself to the CSS. Then, the CSS calculates a user’s pseudo-identity and sends it to . In the AKA phase, only is used during communication. After terminating the key agreement, and the CSS update to new a pseudo-identity . Thus, our scheme provides user anonymity and untraceability.

7.4.10. Perfect Forward Secrecy

According to the adversarial assumptions described in Section 3.2, can obtain the mater key of the CSS . uses to calculate the session key . However, and are transmitted while being encrypted by secret keys and . Even if gains , cannot obtain and . As a result, the proposed scheme guarantees perfect forward secrecy.

8. Performance Analysis

We present a performance comparison between the proposed scheme and related schemes. We estimate “security properties”, “computational cost”, “communication cost” and “energy consumption” of the proposed scheme and show that our scheme offers enhanced robustness and efficiency compared to others.

8.1. Security Properties

We examine the proposed scheme and comparable other schemes [15,16,17,18,19] regarding security features. We contemplate the following security functionalities: : “resistance to impersonation attack”, : “resistance to stolen verifier attack”, : “resistance to ESL attack”, : “resistance to replay attack”, : “resistance to MITM attack”, : “resistance to privileged insider attack”, : “resistance to drone capture attack”, : “ensuring user anonymity and untraceability”, : “ensuring perfect forward secrecy”, : “performing BAN logic”, : “performing RoR model”, and : “performing AVISPA”. We summarize the comparative analysis in Table 4. The proposed scheme achieves abundant security properties that are necessary for IoD communication.

Table 4.

Security properties.

8.2. Computational Costs

This section focuses on analyzing the computational cost of the proposed scheme compared to other related works [15,16,17,18,19]. We quote the work using ubuntu 12.04.1 LTS 32-bit operating system, 2048 MB of RAM, and Intel Pentium Dual CPU E2200 2.20 GHz processor [15]. , , , , and represent HECC divisor multiplication, fuzzy extractor function, symmetric encryption/decryption, AEGIS (AEAD scheme), PUF, and hash function. Table 5 depicts the execution time of the operations. We disregard the time cost of XOR and concentration operations, have extremely low computation costs [40]. In the proposed scheme, a user requires , a CSS requires , and a drone requires . Therefore, the total time overhead incurred by each entity is . Similarly, we also compute the computational costs of the related schemes and compare them with our scheme. We represent the result of the comparison in Table 6. Although the proposed scheme incurs a slightly higher computation time than [16,19], the proposed scheme provides enhanced security. Zhang et al.’s scheme [16] is vulnerable to replay and privileged insider attacks, as outlined in Table 4. In the IoD environment, can illegally control the drones to carry out malicious operations by resending intercepted authentication messages. can also cause malfunctions or disruptions in drone operations to manipulate the IoD system through privileged insider attacks. Therefore, the security drawbacks of their scheme are fatal in IoD environments. Additionally, Sharma et al.’s scheme cannot withstand impersonation, stolen verifier, and ESL attacks, as demonstrated above. Therefore, our scheme has an efficient balance in terms of time cost and security.

Table 5.

Execution time.

Table 6.

Computational costs.

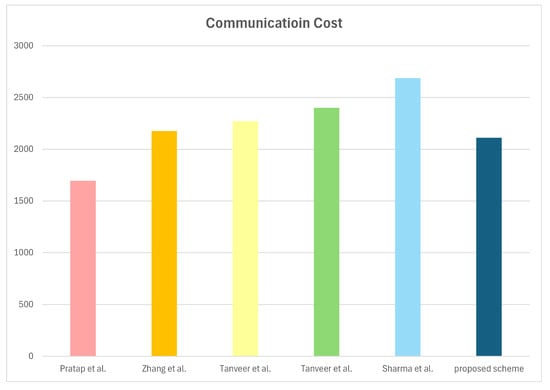

8.3. Communication Costs

We conduct a comparison of communication costs between our scheme and associated schemes [15,16,17,18,19]. In this paper, we consider the size of the PUF response, authentication parameter, hash function output, random number, identity, AES block, MC, HECC divisor, PUF challenge, and timestamp as 320 bits, 256 bits, 160 bits, 160 bits, 160 bits, 128 bits, 128 bits, 80 bits 32 bits, and 32 bits, respectively. In the proposed scheme, all entities transmit four messages, including , , , and . The communication costs of the messages are , , , and . Therefore, the total number of bits is . We also compute the communication costs of relevant approaches. Table 7 and Figure 7 represent the communication costs of the proposed scheme and relevant approaches. The comparative analysis indicates a high communication efficiency of the proposed scheme.

Table 7.

Communication costs.

Figure 7.

Communication costs [15,16,17,18,19].

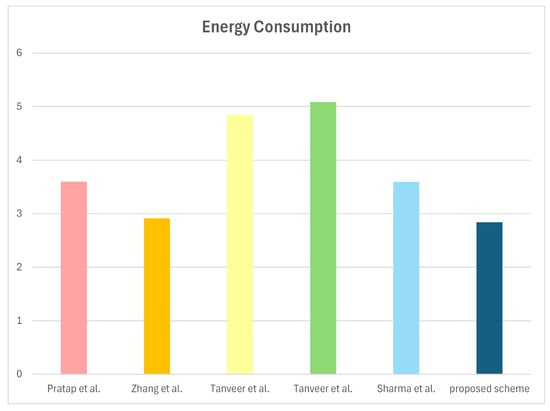

8.4. Energy Consumption

Energy consumption can be calculated with . Based on the equation, we estimate the energy overhead of our scheme with relevant schemes [15,16,17,18,19]. denotes the energy consumption during computation and denotes the energy consumption during communication [41]. According to test works conducted in [42] and the execution time in Table 5 measured by the equipment described in Section 8.2, we can compute the energy consumption for the “HECC divisor”, “fuzzy extractor”, “symmetric encryption/decryption”, “AEGIS”, “PUF”, and “hash function” to be , , , , and , respectively. Additionally, according to [42], communication energy consumption can be calculated as , where denotes the number of bytes sent by the communication entity and denotes the number of bytes received by the communication entity. Further, we assume that energy costs of sending and receiving message are , and [43]. Therefore, the energy consumption of the proposed protocol during computation and communication are calculated to be , and . Consequently, the proposed scheme incurs the energy consumption of . Comparison of energy consumption with associated schemes is depicted in Table 8 and Figure 8. The proposed scheme demonstrates more sustainable energy consumption compared to other related schemes.

Table 8.

Energy consumption.

Figure 8.

Energy consumption [15,16,17,18,19].

9. Conclusions

In this paper, we provided the overview of Sharma et al.’s AKA scheme and conducted a security analysis of it. We verified that their scheme is susceptible against user impersonation, stolen verifier, and ESL attacks. Then, we proposed a lightweight and secure AKA scheme for the IoD to rectify the vulnerabilities of Sharma et al.’s scheme. Fundamental necessities required for IoD communication are guaranteed through our scheme. The proposed scheme is robust to numerous adversarial attacks comprising impersonation, stolen verifier, ESL, MITM, replay, drone physical attacks. We consider the resilience of the scheme as well as the resource limitations of drones. The proposed scheme utilizes lightweight operations such as the hash function, XOR operation, and PUF. We verified the secureness of our scheme with informal analysis. We also demonstrated the security of our scheme by formally employing “BAN logic”, “RoR model”, and “AVISPA”. We represented the efficiency of the proposed scheme, comparing it with other associated schemes. The result of our comparison showed that our scheme is highly cost-effective with robustness regarding its computational cost, communication cost, and energy consumption. Therefore, the proposed scheme allows the IoD to provide improved services. It also involves a higher number of message exchanges in the authentication phase compared with other related schemes. However, the overall communication costs remain efficient because each message has a lower cost in comparison to the compared schemes. Moreover, the proposed scheme considers a wide range of security properties and provides robust protection against various security threats. In our future work, we will implement the proposed scheme, optimizing and confirming its scalability and energy efficiency in a practical large-scale IoD environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.; methodology, J.C.; software, D.K. and S.S.; validation, D.K., S.S. and Y.P.; formal analysis, J.C. and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.; writing—review and editing, D.K., S.S. and Y.P.; supervision, Y.P.; project administration, Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (RS-2024-00450915).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gharibi, M.; Boutaba, R.; Waslander, S.L. Internet of drones. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 1148–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Yin, X.; Wang, X.; Hu, J. A review on security issues and solutions of the internet of drones. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2022, 3, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Diabat, A.; Sumari, P.; Gandomi, A.H. Applications, deployments, and integration of internet of drones (iod): A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 25532–25546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K.; Ghaffar, Z.; Nautiyal, L.; Akram, M.W.; Das, A.K.; Alenazi, M.J. A Privacy-Preserving Access Control Protocol for Consumer Flying Vehicles in Smart City Applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.A. VSKAP-IoD: A Verifiably Secure Key Agreement Protocol for Securing IoD Environment. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 58039–58056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Singh, M.; Rewal, P.; Pursharthi, K.; Kumar, N.; Barnawi, A.; Rathore, R.S. Quantum-safe secure and authorized communication protocol for internet of drones. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 16499–16507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahuza, M.; Idris, M.Y.I.; Ahmedy, I.B.; Wahab, A.W.A.; Nandy, T.; Noor, N.M.; Bala, A. Internet of drones security and privacy issues: Taxonomy and open challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 57243–57270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.; Park, Y.; Das, A.K. Design of blockchain-based lightweight V2I handover authentication protocol for VANET. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapat, S.; Gautam, D.; Kumar, P.; Jangirala, S.; Das, A.K.; Park, Y.; Lorenz, P. Secure lattice-based aggregate signature scheme for vehicular Ad Hoc networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 12370–12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, A.; Alzahrani, B.A.; Albeshri, A.; Alsubhi, K.; Nayyar, A.; Chaudhry, S.A. SPAKE-DC: A secure PUF enabled authenticated key exchange for 5G-based drone communications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 5770–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbarayalu, V.; Vensuslaus, M.A. An intrusion detection system for drone swarming utilizing timed probabilistic automata. Drones 2023, 7, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghelani, J.; Gharia, P.; El-Ocla, H. Gradient Monitored Reinforcement Learning for Jamming Attack Detection in FANETs. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 23081–23095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibecchini, S.; Chiti, F.; Pierucci, L. A Lightweight AI-Based Approach for Drone Jamming Detection. Future Internet 2025, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, M.R.; Hamid, N.A.W.A.; Hussin, M.; Zukarnain, Z.A. Comprehensive Review of Drones Collision Avoidance Schemes: Challenges and Open Issues. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 2024, 25, 6397–6426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, B.; Singh, A.; Mehra, P.S. REHAS: Robust and Efficient Hyperelliptic Curve-Based Authentication Scheme for Internet of Drones. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2024, 37, e8333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hsu, C.; Au, M.H.; Harn, L.; Cui, J.; Xia, Z.; Zhao, Z. PRLAP-IoD: A PUF-based robust and lightweight authentication protocol for Internet of Drones. Comput. Netw. 2024, 238, 110118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; Aldosary, A.; Kumar, N.; Aldossari, S.A. SEAF-IoD: Secure and efficient user authentication framework for the Internet of Drones. Comput. Netw. 2024, 247, 110449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; Aldosary, A.; Khokhar, S.u.d.; Das, A.K.; Aldossari, S.A.; Chaudhry, S.A. PAF-IoD: PUF-Enabled Authentication Framework for the Internet of Drones. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 9560–9574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Narwal, B.; Anand, R.; Mohapatra, A.K.; Yadav, R. PSECAS: A physical unclonable function based secure authentication scheme for Internet of Drones. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 108, 108662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikooghadam, M.; Amintoosi, H.; Islam, S.H.; Moghadam, M.F. A provably secure and lightweight authentication scheme for Internet of Drones for smart city surveillance. J. Syst. Archit. 2021, 115, 101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, B.A.; Barnawi, A.; Chaudhry, S.A. A Resource-Friendly Authentication Protocol for UAV-Based Massive Crowd Management Systems. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2021, 2021, 3437373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, H.; Hashim, S.J.; Hashim, F.; Ahamed, S.M.S.; Chaudhary, M.A.; Altarturi, H.H.; Saadoon, M. HOOPOE: High performance and efficient anonymous handover authentication protocol for flying out of zone UAVs. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 10906–10920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; Khan, A.U.; Kumar, N.; Hassan, M.M. RAMP-IoD: A robust authenticated key management protocol for the Internet of Drones. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah, A.; Abbas, G.; Waqas, M.; Tu, S.; Abbas, Z.H.; Muhammad, F.; Chen, S. USAF-IoD: Ultralightweight and Secure Authenticated Key Agreement Framework for Internet of Drones Environment. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 10963–10977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.K.; Abdussami, M.; Amin, R.; Khan, M.K. D3APTS: Design of ECC Based Authentication Protocol and Data Storage for Tactile Internet enabled IoD System With Blockchain. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 4239–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Chaudhry, S.A.; Ramzan, M.S.; Al-Turjman, F. Securing smart city surveillance: A lightweight authentication mechanism for unmanned vehicles. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 43711–43724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, D.; Soni, T.; Singh, S.; Gupta, S.M.C. A Construction of Secure and Efficient Authenticated Key Exchange Protocol for Deploying Internet of Drones in Smart City. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence of Things, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 25–27 October 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 136–150. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, D.; Soni, T.; Vasudev, K.L.; Saleem, K. A modified lightweight authenticated key agreement protocol for Internet of Drones. Internet Things 2023, 21, 100669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.F.; Lou, D.C.; Chang, C.H. Enhancing lightweight authenticated key agreement with privacy protection using dynamic identities for Internet of Drones. Internet Things 2023, 23, 100877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Farooq, M.; Alzahrani, B.A.; Albeshri, A.; Alsubhi, K.; Chaudhry, S.A. An efficient and reliable user access protocol for Internet of Drones. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 59688–59700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolev, D.; Yao, A. On the security of public key protocols. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1983, 29, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canetti, R.; Krawczyk, H. Universally composable notions of key exchange and secure channels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques (EUROCRYPT), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 28 April–2 May 2002; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 337–351. [Google Scholar]

- Kocher, P. Differential power analysis. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology (CRYPTO’99), Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 15–19 August 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J.; Son, S.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.; Park, Y. Design of secure mutual authentication scheme for metaverse environments using blockchain. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 98944–98958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.; Son, S.; Park, K.; Das, A.K.; Park, Y. Design of Blockchain-Based Multi-Domain Authentication Protocol for Secure EV Charging Services in V2G Environments. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 2024, 25, 21783–21795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazid, M.; Bagga, P.; Das, A.K.; Shetty, S.; Rodrigues, J.J.; Park, Y. AKM-IoV: Authenticated key management protocol in fog computing-based Internet of vehicles deployment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 8804–8817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Park, Y. A robust authentication protocol for wireless medical sensor networks using blockchain and physically unclonable functions. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 20214–20228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.; Son, S.; Kim, M.; Lee, J.; Kumar Das, A.; Park, Y. A Secure Self-Certified Broadcast Authentication Protocol for Intelligent Transportation Systems in UAV-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing Environments. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 2024, 25, 19004–19017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Cheng, H.; Wang, P.; Huang, X.; Jian, G. Zipf’s law in passwords. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2017, 12, 2776–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, S.; Wen, K.; Hu, B.; Tan, X.; Xie, Q. Security-Enhanced Lightweight and Anonymity-Preserving User Authentication Scheme for IoT-Based Healthcare. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 9599–9609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; He, Y.; Niu, B.; Li, H.; Wang, H. Match-MORE: An efficient private matching scheme using friends-of-friends’ recommendation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), Kauai, HI, USA, 15–18 February 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, J.; Ma, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Niu, B. EAP-DDBA: Efficient anonymity proximity device discovery and batch authentication mechanism for massive D2D communication devices in 3GPP 5G HetNet. IEEE Trans. Depend. Secur. Comput. 2020, 19, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, A.; Zhong, L. Context-for-wireless: Context-sensitive energy-efficient wireless data transfer. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications and Services, San Juan, PR, USA, 11–14 June 2007; pp. 165–178. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).