Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are susceptible to fouling, which affects their sensitivity, accuracy, and operational lifetime.

- The review consolidates fouling mechanisms with available detection, cleaning, and antifouling strategies, providing a unified overview of their effectiveness and limitations.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Antifouling strategies are essential to ensure the accurate and long-term operation of ISEs.

- Combining physical, chemical, and material-based approaches is crucial to effectively combat fouling phenomena.

Abstract

Real-time monitoring is essential for maintaining water quality and optimizing aquaculture productivity. Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are widely used to measure key parameters such as pH, nitrate, and dissolved oxygen in aquatic environments. However, these sensors are prone to fouling, the non-specific adsorption of organic, inorganic, and biological matter, which leads to potential drift (e.g., 1–10 mV/h), loss of sensitivity (e.g., ~40% in 20 days), and reduced lifespan (e.g., 3 months), depending on membrane formulation and environmental conditions. This review summarizes current research from mostly the last two decades with around 150 scientific studies on fouling phenomena affecting ISEs, as well as recent advances in fouling detection, cleaning, and antifouling strategies. Detection methods range from electrochemical approaches such as potentiometry and impedance spectroscopy to biochemical, chemical, and spectroscopic techniques. Regeneration and antifouling strategies combine mechanical, chemical, and material-based approaches to mitigate fouling and extend sensor longevity. Special emphasis is placed on environmentally safe antifouling coatings and material innovations applicable to long-term monitoring in aquaculture systems. The combination of complementary antifouling measures is key to achieving accurate, stable, and sustainable ISE performance in complex water matrices.

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Regarding the Topic

Verma et al. (2022) and Lindholm-Lehto (2023) provide a comprehensive overview on water quality parameters used for aquaculture, including temperature, dissolved oxygen, salinity, and turbidity [1,2]. Additional information regarding the real-time monitoring of these parameters is given by Lindholm-Lehto (2023) [2]. A general overview of antifoulants used in aquatic environments is given by Parisi et al. (2022) [3], and information on antifoulants used specifically for ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) can be found given by Qi et al. (2022) [4] and Liu et al. (2025) [5]. However, these studies treat fouling mechanisms, detection techniques, cleaning strategies, and antifouling approaches largely separately. To our knowledge, none of the existing reviews combine these aspects into a comprehensive, application-focused approach for long-term deployment of ISEs in aquatic or aquaculture systems. Publications from 2000 to 2025 with emphasis on the last two years were chosen from Google Scholar, with selected keywords regarding ion-selective electrodes, fouling, drift, cleaning, antifouling, and aquaculture. Studies were included when they addressed explicit keywords and excluded when lacking the methodological relevance or explicit discussion of fouling effects. The following section outlines the concept of water quality to understand challenges regarding fouling on ISEs.

1.2. Water Quality

Water quality serves as a key indicator of environmental integrity and ecosystem stability. It reflects the combined effects of natural processes and anthropogenic influences, including industrialization, agricultural runoff, and urbanization [6,7,8]. Understanding and controlling the defining parameters of water quality are therefore fundamental prerequisites for effective monitoring, pollution prevention, and sustainable resource management. Monitoring programmes based on standardized water quality parameters enable the early detection of pollution events and the assessment of remediation strategies. These parameters act as diagnostic indicators that capture both the current state and temporal trends of aquatic environments, thereby supporting water management decisions and ensuring compliance with environmental regulations [6].

Global Context and Importance of Water Quality

The availability or scarcity of freshwater is a major global challenge that increasingly threatens human existence [6,7]. Approximately one third of the world’s drinking water is obtained from surface waters such as rivers, lakes (including dam reservoirs), and canals. These also serve as sinks for the discharge of domestic and industrial wastewater. The disposal of untreated or partially treated wastewater is a worldwide issue and represents a major source of water pollution affecting freshwater bodies [8]. To develop effective strategies for reducing and eliminating pollution, specific water quality parameters must be monitored and maintained within defined limits. These parameters and their continuous monitoring have a significant impact on (i) human well-being (e.g., health, property, access to drinking water) [9], (ii) the environment (e.g., eutrophication, suppression of photosynthetic systems, dam functionality, aquatic ecosystem health) [10,11], and (iii) industrial applications (e.g., dairy, textile, and other wastewater processes) [12,13,14]. In aquaculture, water quality is critical. It directly determines animal health and production efficiency.

1.3. Relevance of Water Quality for Aquaculture

Maintaining good water quality is essential for aquaculture production, as aquatic organisms are directly dependent on their surrounding water for respiration, nutrition, and growth. The industrial cultivation of fish, shellfish, aquatic plants, and other marine organisms such as shrimp in freshwater, saltwater, or brackish environments for human consumption is defined as aquaculture [15]. Reducing inputs (e.g., feed), optimizing outputs, and minimizing pollution make aquaculture an attractive and sustainable alternative to conventional fishing [16]. Aquaculture is one of the fastest-growing food-producing sectors worldwide, now surpassing capture fisheries and accounting for approximately 53% of total production for human consumption [17]. Similarly to agriculture, aquaculture has undergone significant technological transformation in recent decades to meet growing global demands [17]. Ensuring and controlling water quality is crucial for achieving high productivity and maintaining healthy stock. Elevated mortality rates are often linked to poor water quality [18]. Continuous monitoring of physicochemical parameters can reduce production losses by 20–40% [17]. The strong correlation between water quality and the physiological health of cultured organisms means that deviations from optimal conditions can lead to stress, disease, or death [19]. Consequently, precise control of key parameters is vital to sustain both productivity and food quality in aquaculture systems. These critical parameters and their acceptable limits vary widely between species [17] and are particularly complex in multi-species systems [20]. Therefore, real-time monitoring is required to support informed decision-making by operators and prevent water quality deterioration before it impacts animal welfare.

Additionally, water quality can differ significantly between surface water and groundwater. Even local variations in tap or well water (depending on site location [18]) may require pretreatment to achieve optimal cultivation conditions [21]. Such variability underscores the importance of deploying robust, real-time monitoring systems, such as ion-selective electrodes, that can continuously track essential parameters like pH, salinity, or dissolved oxygen in aquaculture environments. Integrating these sensors into recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) or other controlled setups ensures consistent environmental stability, minimizes fouling-related signal drift, and enhances automation for sustainable production. The key parameters of water quality control in aquaculture are listed in the following section.

1.4. Key Water Quality Parameters for Aquaculture

Key water quality parameters for aquaculture typically include the following:

- Temperature,

- Dissolved oxygen (DO),

- Colour/turbidity,

- Electrical conductivity (EC),

- Ozone or Oxidation–reduction potential (ORP),

- pH (pondus hydrogenii), and

- Specific ions or trace elements such as nitrate, sodium, and chloride [1,2].

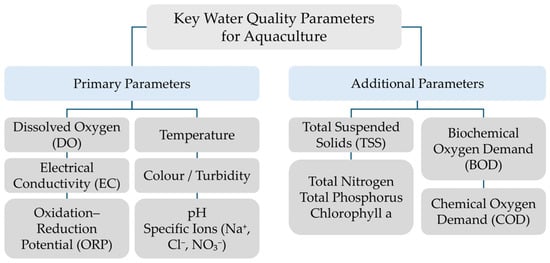

These parameters jointly determine the chemical and biological balance of aquatic environments and directly influence the metabolism, growth, and reproduction of cultured species. Temperature and DO are key regulators of respiration and enzymatic activity, while pH and ORP define the redox conditions that control nutrient availability and ammonia toxicity [22]. Electrical conductivity, salinity, and the presence of dissolved ions (e.g., Na+, Cl−, NO3−) serve as indicators of the overall ionic composition, which affects osmoregulation and stress tolerance in aquatic organisms [22]. Additional relevant parameters include total suspended solids (TSS), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), total nitrogen, total phosphorus, and chlorophyll a (Figure 1) [23].

Figure 1.

Overview of key water quality parameters for aquaculture.

These indicators provide essential insights into organic load, eutrophication potential, and biological productivity in aquaculture systems. Elevated TSS and BOD values may reduce light penetration and oxygen availability, while increased COD reflects the accumulation of oxidizable organic matter. The concentrations of total nitrogen and phosphorus are critical for evaluating nutrient cycling and for preventing excessive algal growth [23]. Continuous monitoring of these parameters in aquaculture is primarily achieved through electrochemical and optical sensor systems, including thermistors, ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), Clark-type oxygen sensors, and nephelometric or conductivity probes. Integration of these sensors in RAS enables real-time control of water quality and early detection of fouling or chemical imbalance, ensuring stable operational conditions for aquatic organisms [22,23].

2. Real-Time Monitoring of Water Quality Parameters: Concepts and Applications

Real-time monitoring refers to the continuous observation and acquisition of data for specific parameters while a process is running [24]. It has been implemented in various industrial and environmental applications, such as health monitoring (e.g., heart disease, blood pressure, diabetes) [25], nutrient monitoring [26], bioreactors [27], wastewater treatment [28], and aquaculture [29]. Today, a wide variety of techniques are available for water quality monitoring, including sensors, analytical technologies (chromatography, mass spectrometry), biochemical and molecular methods (immunoassays, PCR assays, culture-based techniques), and biophysical technologies (biosensors and nano sensors) for detecting environmental contaminants [15]. A small comparison regarding their performance advantages and disadvantages is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of different methods to detect water quality parameters and their advantages and disadvantages regarding performance.

3. Sensor Technologies for Water Quality Monitoring and Process Control

Sensor technologies play a fundamental role in advancing scientific understanding, process automation, and operational control. They enable timely intervention and corrective action in critical situations. For instance, precision aquaculture, based on sensor networks, can help minimize or prevent the negative environmental impacts of aquaculture activities [30]. Water quality sensors are used to evaluate process efficiency, optimize the performance of treatment and purification systems, and assess the ecological health of rivers, lakes, and wastewater streams. Despite their advantages, sensors are highly susceptible to fouling and biofouling in aqueous environments, which deteriorates sensor performance, increases maintenance requirements, degrades data quality, and consequently raises operational costs [31].

While sensors are widely used in terrestrial applications, their deployment in aquatic environments remains limited due to challenges such as high salinity (corrosion), fouling and biofouling, and the loss of waterproof integrity [16,30].

Kruse (2018) classifies chemical sensors into four main categories [32]:

- Mechanical transduction sensors detect physical deformations, pressure, or flow variations and convert them into measurable signals, often applied in flow rate or turbidity monitoring.

- Optical transduction sensors utilize light absorption, fluorescence, or scattering to determine parameters such as turbidity, colour, or dissolved organic matter.

- Electrochemical transduction sensors convert chemical or ionic activities into electrical signals and include potentiometric, amperometric, and conductometric systems. Among these, ISEs are widely used for monitoring pH, ionic strength, and nutrient concentrations in aquatic environments.

- Electrical transduction sensors measure variations in impedance, capacitance, or conductivity caused by chemical or biological interactions, offering high sensitivity in complex matrices.

A comparison of the sensor categories is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages (regarding performance) of different methods to detect water quality parameters.

Among these, electrochemical sensors, redox-related parameters (e.g., DO, ORP), and particularly ISEs (pH and other ions) are the most widely used [32].

4. Ion-Selective Electrodes: Structure, Function, and Operational Principles

To achieve accurate, real-time monitoring of critical water quality parameters such as pH, nitrate, and other ions, specialized electrochemical sensors known as ISEs are employed. ISEs are designed to selectively detect target ions in aqueous solutions [33] and are widely used in various online monitoring applications worldwide to measure ions such as nitrate [34], titanium [35], lead [36], ammonium, lithium, sodium, potassium, caesium, silver, calcium, copper, cadmium, iron, cerium, chloride, sulphate, and phosphate [37]. They are increasingly integrated into automated systems, including titration setups and nutrient management platforms [38,39]. The selectivity is enabled by semi-permeable membranes, which allow the passage of only specific ions of interest [40].

4.1. General Structure and Working Principle

ISEs typically consist of two half-cells:

- a measuring half-cell, equipped with an ion-selective membrane that determines ion permeability, and

- a reference half-cell, usually containing an Ag/AgCl electrode.

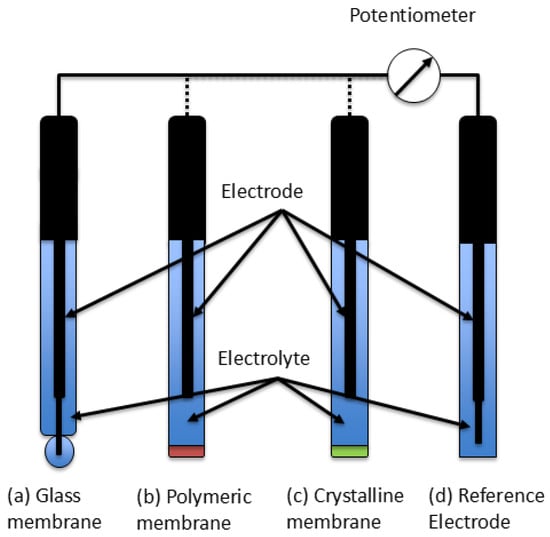

Each half-cell contains an electrode immersed in an electrolyte solution (e.g., KCl) [41]. The potential difference between the two electrodes follows the Nernst equation and is thus proportional to the ion concentration or activity [42]. A schematic representation of a typical ISE setup is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Working principle of a potentiometric ion-selective electrode, with a (a) glass membrane, (b) polymeric membrane, (c) crystalline/solid-contact membrane, and (d) reference electrode.

Common ISEs integrate both half-cells into a single probe body (e.g., made of PEEK) with a sensing tip in contact with the sample solution [43].

Three main types of ISEs can be distinguished:

- ISEs with a glass membrane (e.g., multi-component chalcogenide for Pb2+ selectivity),

- ISEs with a polymeric ion-selective membrane, and

- ISEs with a crystalline or solid-state ion-selective membrane [44].

4.2. Glass Membrane Ion-Selective Electrodes

A standard pH electrode (glass electrode) detects protons (H+) or hydronium ions (H3O+) using an ion-selective glass membrane [45]. The sensor measures a pH-dependent potential difference across the membrane when immersed in a solution. This potential difference between the measuring and reference electrodes is proportional to the pH value according to the Nernst equation [46]. The response time of an ISE is defined as the time between immersion of the sensing element in the sample and the moment when the potential reaches a steady state within ±1 mV (or 90% of its final value), and can be so short that the associated electronics become the limiting factor.

4.3. Polymeric Ion-Selective Membranes

Polymeric ion-selective membranes typically consist of the following components [47,48]:

- Polymer matrix—provides mechanical stability and forms the base structure for other components (commonly poly(vinyl chloride), PVC);

- Plasticizer—softens the polymer matrix and enhances ion mobility and flexibility (e.g., phthalates such as dioctyl phthalate);

- Ionophore—an embedded ion carrier that binds specific ions, ensuring selectivity (e.g., quinazoline derivatives such as dibutyl(8-hydroxyquinolin-2-yl)methyl phosphonate); and

- Ion exchanger/lipophilic additive—facilitates ion exchange, maintains electroneutrality, and improves membrane conductivity and selectivity (e.g., potassium tetrakis(p-chlorophenyl)borate).

4.4. Solid-State and All-Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrodes

Solid-state ISEs (e.g., based on supercapacitor materials such as nickel cobalt sulphide) do not contain a liquid electrolyte [49]. Consequently, they are easier to miniaturize, are not prone to evaporation, and exhibit reduced potential drift compared to conventional ISEs, since there is no volume change in the electrolyte. However, they can be sensitive to pressure and temperature variations [50]. In these sensors, ion-to-electron transduction occurs via solid contact between the ion-selective membrane and the electronically conductive substrate [50].

4.5. Construction and Sensor Body Materials

Beyond serving as a protective barrier against contamination (e.g., of the internal electrolyte) and shielding the half-cells, the sensor body material itself significantly influences measurement stability. Certain components (e.g., from a PVC body) may leach into the ion-selective membrane, reducing ion selectivity, and vice versa [51]. A trade-off must therefore be made: materials such as PTFE and PEEK offer excellent inertness and chemical resistance but poor membrane adhesion, whereas PVC provides superior adhesion but lower chemical resistance [51].

4.6. Laboratory vs. Field

A comparison of ISE-type sensors with colorimetric methods such as the phenate method and the salicylate method in aquacultures to determine the total ammonia nitrogen in RAS showed a less accurate correlation (R2 ranging from 0.919 to 0.996) for ISEs in comparison to the phenate and salicylate methods (R2 = 0.996), whilst ISEs provided larger detection rates (0.05–14,000 ppm for NH3 ISE and 0.04–14,000 ppm for NH4+ ISE in comparison to 0.02–5 ppm for Nessler’s reaction) without the use of chemicals/dyes which alter the medium (e.g., rise in pH) [52]. Furthermore, concentrations above 5 ppm exceed the limit of detection of the salicylate method (1 ppm), the phenate method (2 ppm), and Nessler’s reaction (5 ppm) [52], which are offline and hence geographically and temporally divided from the process.

Whilst most analytical methods provide offline data, sensors excel through their implementation inside the process and thus field deployment, hence providing real-time inline data. Accurate prediction of water quality parameters for improved management is a current challenge in the aquaculture industry [53]. Real-time monitoring generates large volumes and diverse types of data [17], which enable the anticipation and prediction of changes in water quality parameters [17]. Moreover, warnings and automated alarms can be established based on prior monitoring experience [16]. Further advantages and limitations of ISEs are stated in the following section.

4.7. Advantages and Limitations of ISEs

Potentiometric ISEs typically exhibit rapid response times, as fast as 3 s, and long operational lifetimes, e.g., up to two months for Fe2+-ISEs [54]. In general, ion-selective electrodes offer significant advantages in terms of accuracy, measurement speed, cost, and sensitivity compared to analytical techniques such as UV/VIS spectroscopy for detecting specific ionic activities on-site [55]. Modern ISEs are also cost-competitive with UV/VIS and UV sensors in applications such as activated sludge processes, where they monitor nitrate and nitrite concentrations and thus aid in aeration control [56].

Beyond analytical precision, ISEs also offer several practical advantages in real-time process monitoring. In comparison with optical or amperometric sensors, ISEs operate without reagents or gas-phase calibration. They are not influenced by colour or turbidity, consume minimal power, and can be easily miniaturized and integrated into multiparameter sensor arrays [55,56,57]. Their compact, robust design enables long-term in situ measurements in harsh aquatic environments, where high salinity or turbidity may interfere with optical systems. These features make ISEs particularly suitable for continuous monitoring and automated control of key parameters such as pH, nitrate, and ammonium in aquaculture and wastewater treatment processes [56,58]. Furthermore, broad selectivity of ionophores leads to a broad range of parameters covered by ISEs.

However, their long-term stability remains limited by membrane fouling, drift, and temperature sensitivity, necessitating periodic cleaning and recalibration [58,59]. Further limitations regarding ISEs are as follows:

- Unlike methods such as chromatography, ISEs detect only free ions (e.g., F−), reflecting ionic activity, while bound or complexed species (e.g., fluorides) remain undetected in complex solutions [60]. To provide better correlations regarding the ionic strength of the solution, ionic strength adjuster can be used prior to calibration, thus imitating field conditions.

- At high concentrations, increased ionic strength reduces the activity of the target ion, leading to a nonlinear relationship between activity and concentration [57]. Usage of the ISE in the linear range is usually stated by the producer as its operating range, which may be insufficient in salt water or industrial waters.

- Interference effects occuring from ions with similar charge and size—for instance, NO3−-ISEs are affected by IO3− and I− [61], while NH4+-ISEs suffer from H+ interference [62]. This effect is crucial for multi-ion systems such as aquacultures, saltwater, and wastewater, where cross-ion interferences falsify measurements. To address the problem, a cross-ion compensation via modelling or multi-sensor systems can be established.

- Some ISEs (like lead-ISE) operate in a small process range (e.g., working range pH = 4.0–6.9) [63]. Often, the ion-selective membrane (ISM) of the ISE destabilizes in low or high pH or salinity, hence their performance may be restricted.

- Potential drift in open-circuit measurements necessitates frequent calibration and long conditioning times prior to operation—sometimes even daily or more often [59]. ISEs should be used according to the maximum operating time, hence long-term usage beyond operating time can be critical.

- The ionophore-based polymer membranes (often PVC) are highly susceptible to mechanical stress and fouling/biofouling in complex media, which limits their performance in continuous applications [58]. Furthermore, plasticizers are prone to leaching, affecting aquatic lifeforms but also the stability and maintenance frequency of ISEs.

- Finally, the sensitivity of conventional potentiometric ISEs is limited by the Nernst equation (~59.2 mV per decade for monovalent ions), making it difficult to detect narrow concentration ranges (e.g., Na+ in blood: 135–145 mmol/L) or very small variations (e.g., ocean acidification: −0.002 pH units per year) with sufficient reliability [64]. Further preparation of the solutions or non-Nernstian approaches can help detect these narrow changes.

Despite these drawbacks, ISEs remain among the most versatile and practical tools for ion detection—and one of their most recognized challenges continues to be fouling.

5. Fouling Mechanisms on Ion-Selective Electrodes

Fouling describes the undesired deposition of molecules like proteins, lipids, and microorganisms on the electrode surface (or in case of ISE also on the ion-selective membrane), leading to drifts in signals, prolonged response times, lower sensitivity, and shorter lifespan of the sensor [60,61]. Further, reproducibility and limit of detection can be affected by fouling [62].

Determining an exact fouling degree, fouling rate, or fouling layer formation rate is usually difficult due to the complexity of the media composition (colloidal deposits and biofouling). Factors that can affect the extent of fouling include the composition, temperature, and flow properties of the medium; pH value; the (membrane) material; and the design of sensors and thus surfaces like membranes of sensors that are in contact with the medium. Other factors, such as geographical position, salinity, light, silt, competition between organisms, and others, can have a strong influence on fouling rates in specific applications [59]. To evade fouling, a trend towards single-use sensors is rising [62].

In this review paper, fouling is categorized into three different groups: organic fouling, the deposition of organic molecules (e.g., proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, other organic matter); inorganic fouling, the precipitation or crystallization of salts, hydroxides, or mineral deposits; and biological fouling (biofouling), the attachment and proliferation of microorganisms, extracellular polymeric substances, and macrofouling.

In aquaculture systems, particularly in RAS, these fouling mechanisms are of major practical relevance. The continuous monitoring of parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen, ammonium, or nitrate exposes ISEs to nutrient-rich and biologically active environments, which strongly promote both organic and biofouling. Such processes can cause sensor drift and reduced accuracy, directly influencing the reliability of water quality management and, consequently, the health and productivity of cultured species.

Whilst many works have documented fouling on ISEs regarding a qualitative approach, few works look at quantitative fouling kinetics, such as fouling deposition rates in correlation to environmental parameters. Cecchoni et al. state a lag phase of 1 week without appreciable effects of NH4+ ISE in activated sludge processes and suggest cleaning routines of 1 week; ongoing usage leads to an exponential increase in response time of the sensor, and after approximately 1 month a plateau in fouling is reached [65]. Over time, a change from reversible fouling (2–4 weeks) to irreversible fouling (3–5 months) occurs, and response times remain slow and show the ageing of the electrode even after cleaning [65]. Furthermore, Grzegorczyk et al. (2018) suggest a Gompertz-sigmoidal-function-like biofilm growth kinetics, with a short initial running-in phase and exponential growth followed by a saturation phase, providing examples for lag phases (λ = 2.8 ± 0.2 d for initial extracellular polymeric substances and λ = 6.4 ± 0.4 d for late extracellular polymeric substances, respectively) and specific growth rates (0.27 ± 0.009 h−1 for biochemical preconditioning, 2.80 ± 0.2 d−1 for initial extracellular polymeric substances, and 6.4 ± 0.009 d−1 for late extracellular polymeric substances, respectively) [66]. Lyu et al. (2020) state drifts for solid-contact ISEs from 0.0117 mV/h to 1.4 mV/h [67], which depend strongly on both membrane formulation and environmental conditions. Furthermore, membrane-blocking is notable via drifting of ISEs in wastewaters after 20–48 h.

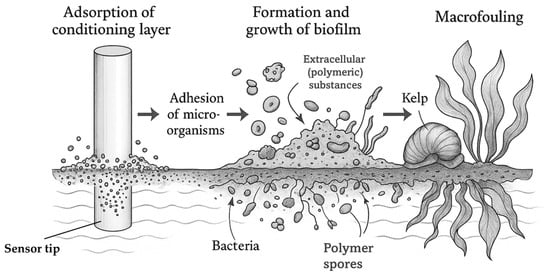

5.1. Biofouling Processes and Formation Mechanisms

Biofouling (analogous to fouling) is defined as the unwanted accumulation of organisms (and biofilms) on exposed, submerged, or partially submerged sensor surfaces [68,69]. Generally, the phenomenon manifests itself wherever a non-sterile medium encounters a surface and provides adapted, undesirable properties (technical, health-related, or environmental) [31]. Among other things, biofouling leads to reduced efficiency of plant components, increased risk of contamination from biofoulants, increased likelihood of corrosion, and an increase in the probability of failure of plant components [31,70]. Biofouling occurs more frequently in warm regions/seasons like the tropics, as temperature directly affects growth of fouling species (increasing in summer and decreasing in winter, respectively) [71]. It usually consists of four stages, as shown in Figure 3: adsorption of a conditioning layer (I.), adhesion of microorganisms (e.g., bacteria) (II.), formation and growth of a biofilm (III.), and macrofouling (IV.)

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of biofouling processes and formation mechanisms on an ion-selective electrode sensor tip.

Figure 3 illustrates the continuous development of biofouling, from the adsorption of an initial conditioning layer to bacterial adhesion, biofilm development, and macrofouling. Within a short time (1 min–1 h [72]), proteins and carbohydrates adsorb to a submerged surface (e.g., stainless steel [73]) in an aqueous environment. In this process, no continuous film is formed; instead, strongly varying, heterogeneous sections with different thicknesses develop [71]. This can lead to a slight increase in membrane resistance regarding ISEs. Next (1 h–1 d [72]) bacteria attach to the surface and form colonies which secrete extracellular (polymeric) substances (mainly proteins and polysaccharides, e.g., hexoses [71]) and a biofilm forms on the surface (1 d–1 w [72]), which induces a measurable drift for ion-selective electrodes. The biofilm is heterogeneous, varies according to the composition of the bacterial strains/microorganisms, and traps other isolated organisms, such as spores of algae or fungi [71], leading to a delayed response time of electrodes. Finally (2 w–1 m [72]), larger marine organisms, such as mussels or kelp, settle on the surface. This phenomenon is called macrofouling and takes place over a period of days to weeks [71] and can lead to partial or complete loss of ISE signals.

Biofouling is a complex process that can lead to the formation of widely varying biofilms depending on the prevailing conditions, such as the properties of the medium, including pH and organic composition in the form of lipids, proteins, and polysaccharides; the presence of bacteria, other microorganisms; and their metabolites, and multicellular species or large marine organisms [74,75]. Furthermore, the choice of surface hardness influences biofouling development: most aquatic fouling organisms tend to prefer hard surfaces, with approximately 127,000 identified species on hard surfaces and 30,000 on soft surfaces, respectively [76]. In addition, factors such as wettability (hydrophilic, hydrophobic, superhydrophilic, and superhydrophobic), colour, and micro texture also affect biofilm composition [76]. Moreover, biofouling communities vary temporally (due to seasonality in populations, arrival of new recruits, and growth periods) and spatially on a small and large scale (due to planktonic events, positional choices of attachment and settlement, mortality, and environmental influences) [77].

In aquaculture systems, biofouling is the dominant fouling type. Sensors used in fish tanks or RAS loops are continuously exposed to microbial populations, feed residues, and metabolic by-products. Biofilm formation on ISE membranes can rapidly lead to signal drift, delayed response times, or complete sensor failure. The high organic load and nutrient availability in aquaculture water further accelerate microbial attachment and biofilm maturation, making biofouling control a key challenge for reliable water quality monitoring.

5.2. Biofilm Development and Structural Characteristics

Some organisms are able to perform biofouling without an existing biofilm (e.g., barnacles of the genus Amphibalanus amphitrite) [75]. If a biofilm is formed, it appears as a film that contains algae, bacteria and/or fungi, and organic and inorganic substances, separating them from the surrounding environment. Generally, a biofilm is formed in four stages: 1. Attachment, 2. Proliferation, 3. Maturation, and 4. Dispersion [78]. The properties and structure of the biofilm vary greatly due to different biofilm organisms, physical conditions (including hydrodynamics, temperature, and surface properties), and chemical conditions (inhibiting substances, nutrient levels, and surface composition) [79]. Other factors that influence biofilm formation include pH, EC, DO concentration, region, season, light, and thereby depth of a water body [80]. A biofilm can significantly increase the tolerance of organisms to stressful environmental influences, which reduces the effectiveness of cleaning strategies [74].

Biofilms in aquaculture environments develop not only on sensors but also on tank walls, pipelines, and filtration units, where they affect both water quality and measurement accuracy. Once formed on ISE membranes, they can entrap nutrients and metabolites, locally altering ionic strength and pH. Such changes may result in sensor misreadings that compromise automated control processes such as aeration, feeding, and water recirculation in RAS.

5.3. Fouling Effects on Ion-Selective Electrode Membranes

Ion-selective electrodes often use a polymeric semi-permeable membrane, which is ion-selective, hence permeable only to a specific kind of ion. A correlation between fouling in membrane technology, especially regarding (ion-exchange) polymeric membranes [81], and fouling on ion-selective electrodes (here a PTFE membrane) [65] can be established.

According to Qi et al. (2022), fouling on ion-selective electrodes arises from nonspecific adsorption of substances onto the membrane [4]. Polymeric ISEs mostly suffer fouling of lipophilic sources (e.g., proteins, lipids, microorganisms, and oil) due to their liquid-like hydrophobic surface. Selectivity, stability, and lifetime of sensors can be influenced by fouling [4]. General influences of different fouling types according to Qi et al. (2022) are represented in Table 3 [4].

Table 3.

Summary of reported fouling effects on ISEs.

On one hand, sensors can be completely inactivated, e.g., by blocking semi-permeable membranes [82]. On the other hand, fouling (biofilm growth) can be limited to a maximum degree or level (here, a total population of 105/mm2 was noted as the maximum limit; further exposure to fouling media does not affect the fouling layer/resistance) [83]. In aquaculture environments, such fouling-induced sensor inactivation directly affects operational control. Faulty readings of pH, ammonium, or nitrate can lead to suboptimal oxygenation, feed dosing, or recirculation control. Therefore, understanding fouling effects on ISE membranes is essential for maintaining accurate and continuous real-time monitoring in RAS and similar systems.

5.4. Impact of Fouling and Biofouling on Sensor Performance

Biofouling, in combination with inorganic or organic fouling, significantly affects the response time of pH sensors [65,79]. Diffusion limitations to and from the membrane, as well as blockage of the electrode’s liquid junction, can occur. Fouling layers increase the effective membrane thickness, thereby extending the diffusion path for ions to reach the electrode surface. At the same time, they raise the membrane resistance, analogous to the resistance-in-series model known from membrane technology, resulting in a prolonged sensor response time [79]. Moreover, the buffering capacity of biofilms and their secreted substances can further influence the sensor’s reaction kinetics. Biofilms also alter the local pH value at the electrode surface, reducing measurement accuracy and sensitivity, and may even distort sensor readings [31,79]. Interestingly, visible biofouling on sensors has been reported predominantly at depths lower than 75 m [84].

Fouling of electrodes in electrochemical analyses can affect their analytical characteristics, including sensitivity, detection limit, reproducibility, and reliability, thereby influencing the overall process performance [85]. Electrode fouling refers to the passivation of the electrode surface by adsorbed foulants, forming a progressively impermeable layer that prevents analytes from reaching the electrode surface [85].

Fouling typically occurs at specific surface features, such as edges or sites with favourable physicochemical properties, and can be driven by hydrophilic, hydrophobic, and/or electrostatic interactions, depending on the chemistry of both the foulant and the electrode [85]. Hydrophilic fouling tends to be more reversible, whereas hydrophobic fouling is often more persistent, as hydrophobic interactions are entropically favourable in aqueous environments due to the exclusion of water molecules, a phenomenon known as the hydrophobic effect [85].

Potentiometric ion-selective electrodes are generally unaffected by changes in electrode surface area, but their potential stability may still be influenced by surface processes such as biofouling [86]. Therefore, the detection of fouling is essential for the effective regeneration or cleaning of ISEs, as well as for the development of preventive antifouling strategies.

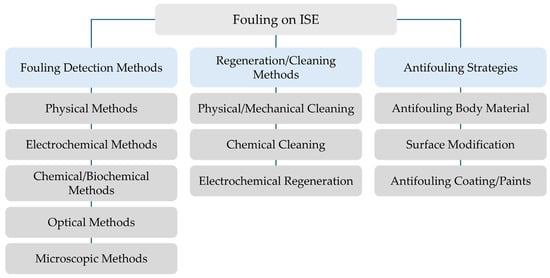

Figure 4 shows the operational logic to manage fouling on ion-selective electrodes. First, fouling detection is needed and performed by means of physical, electrochemical, and chemical/biochemical methods. After determining the fouling degree, appropriate regeneration/cleaning methods, such as physical/mechanical, chemical, and electrochemical cleaning/regeneration, are applied. To further ensure long-term stability of the ISE, preventive antifouling strategies (e.g., antifouling coatings, surface modifications, membrane engineering) are implemented.

Figure 4.

Schematics of fouling on ISEs covering detection methods, regeneration/cleaning approaches, and prevention strategies.

5.5. Implementation of ISEs in RAS

The practical implementation of ISEs in RAS derives from three key performance indicators: (i) long-term drift, (ii) mean time between cleaning events, and (iii) the percentage of out-of-range readings.

Long-term drifting is a crucial parameter regarding long-term deployment of ISEs. Dissolved oxygen sensors and pH sensors drift approximately 2–5% over 6–12 months despite regular calibration; conventional ammonia ISEs exhibit a 3% drift over six months [87]. Yet, these values differ due to variables like membrane formulation and environmental conditions. Further usage of ISEs can lead to more frequent calibration to secure “accurate” measurements [87]. Operational longevity of ISEs stated by producers range from several months up to a year, depending on calibration frequency and medium composition. The mean time between calibration varies from daily (e.g., pH ISE Mettler Toledo InPro) to bi-weekly (NH3 ISE from Orion™) [87]. The percentage of out-of-range readings are not systematically reported in scientific studies.

A cleaning procedure should be implemented if the sensor’s slope varies by 10% of the initial slope or drifts by 5 mV, while recalibration could be used in the case of a slope deviation of 5% or an offset deviation of 5 mV. Furthermore, a sensor health score combining slope fidelity, drift stability, baseline offset, and response time performance, as well as impedance integrity, noise level, and redundancy consistency can help compare the health of sensors. Replacement may be required once the sensor’s slope differs by 15–20%.

In general, the hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions with proteins, surface-blocking, and lipophilicity of the ISM determine whether the ISM is subjected to fouling by proteins, polysaccharides, or lipids, respectively [5]. Long-term drift and cleaning frequency change regarding these parameters.

Within aquaculture monitoring systems, such as RAS, these effects manifest as gradual sensor drift and delayed signal response, complicating automated feedback loops controlling aeration or dosing. Continuous exposure to organic waste, biofilms, and microbial metabolites further accelerates these fouling mechanisms. Effective fouling management on ISEs is therefore critical for ensuring stable, long-term, and accurate monitoring of water quality in aquaculture operations. To implement ISEs in RAS, operational thresholds or control indicators should be used to determine calibration, cleaning, and replacement frequency. Such indicators could be the critical comparison of fouling rates and their influence on performance, Nernst slope deviation, baseline/offset drift, response time, potential drift (reference electrode stability), leakage/internal electrolyte level, and slope consistency across multi-point calibration.

6. Detection and Monitoring Methods for Fouling on Ion-Selective Electrodes

The detection and mitigation of fouling on sensors—particularly ISEs—are crucial for ensuring long-term measurement stability and accuracy. Various methods exist to identify different types of fouling phenomena and to assess their extent and severity, but only a few are for sensor surfaces. Fouling detection depends strongly on the process environment and surrounding operational parameters. For instance, biofouling can be detected by monitoring the conductivity of the medium via conductometry, since the conductivity of culture media correlates with microbial growth and fermentation activity [88].

In aquaculture monitoring systems, early detection of fouling on ISEs is vital for maintaining stable real-time measurements of key parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen, or ammonium. Biofilm formation on sensor surfaces can cause drift or delayed response, leading to misinterpretation of water quality data and consequently to inefficient control of aeration or feeding regimes. Reliable fouling detection techniques therefore contribute directly to the health management and productivity of aquaculture systems, particularly RAS.

Common fouling detection techniques for sensors, including ISEs, comprise the following (see Figure 4):

- Physical methods such as quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) [50] and surface plasmon resonance (SPR);

- Electrochemical methods such as potentiometry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) [50];

- Chemical and biochemical methods including staining with dyes or radioactive labelling [86];

- Optical techniques such as UV/VIS and fluorescence microscopy; and

- Microscopic techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [50] and atomic force microscopy (AFM);

Blaen et al. (2016) additionally reported reflected light microscopy and X-ray diffraction (XRD) for characterizing the membrane surface of ISEs [26]. A comparison of sensitivity, reproducibility, and suitability of different detection methods is listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of methods to detect fouling on ISEs regarding sensitivity, reproducibility, early detection, inline, and suitability for aquacultures and notes.

Chemical cleaning followed by analysis of removed foulants can also provide quantitative and qualitative insights into the degree of fouling. Importantly, even partial surface coverage by fouling can significantly impair electrode performance [26]

6.1. Physical and Optical Methods for Fouling Detection

In many cases, fouling effects can be observed visually [89]. Colorimetric ion-selective sensors, for example, exhibit colour shifts due to changes in chromophores when the target analyte also acts as a foulant. Hence, a sensor immersed in a standard solution should display a characteristic colour change [90].

Chemical staining techniques employing dyes such as Carnoy’s solution, toluidine blue, or SYTO 9 are used to visualize bacterial growth and biofouling on sensor surfaces [89,91]. Subsequent analysis via (confocal) laser scanning microscopy enables high-resolution detection of stained biofilm structures [92]. Other optical methods, including UV/VIS spectroscopy and image analysis, are also applied, although results should be interpreted cautiously, as they may not linearly correlate with fouling severity [83].

Raman spectroscopy can detect fouling on both amperometric and potentiometric ISEs [93], while field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) provides detailed surface characterization [94]. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), also known as electron spectroscopy for chemical analysis (ESCA), can determine membrane composition and chemical binding states [26].

The quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) is another valuable method for fouling quantification. It measures mass changes on the sensor surface by comparing the resonance frequency before and after exposure [95]. QCM can also be used for real-time monitoring of mass accumulation during fouling processes [96].

In aquaculture applications, such physical detection methods can reveal biofilm accumulation on submerged ISEs before critical signal drift occurs. For instance, QCM-based monitoring could be adapted for in situ evaluation of fouling rates in nutrient-rich aquaculture water, helping operators schedule cleaning or regeneration cycles before measurement failure affects stock management.

6.2. Electrochemical Methods for Fouling Detection

Indirect monitoring of parameters such as EC or pH can provide early indicators of fouling. A correlation between conductivity and biofouling growth has been established, as conductometric methods enable the detection of bacterial activity on sensors [97]. In harsh operational environments—such as under highly acidic or alkaline conditions—changes in pH, combined with exposure time, can be used to estimate an additional fouling rate. While low pH (<4) increases inorganic precipitation and membrane swelling, high pH (>10) increases hydroxide precipitation and the adsorption of proteins. High salinity leads to faster colonization by halophilic organisms and densification of extracellular polymeric substances; high organic load accelerates the formation of extracellular polymeric substances and biofilm thickening. These processes are strongly influenced by flow limitations (stagnant zones, increased attachment, and diffusion limitation) and temperature (accelerated microbial and biofilm growth).

Because ion-selective electrodes operate based on electrochemical reactions, a variety of electrochemical techniques can be employed for fouling assessment, including the following [98]:

- Chronopotentiometry,

- Chronoamperometry,

- Pulse amperometry,

- Differential pulse voltammetry,

- Conductometry, and

- Polarization measurements.

Using a combination of these techniques provides a more comprehensive and reliable evaluation of fouling on ISEs. Different sensor types (e.g., potentiometric or amperometric) require specific detection methods suited to their transduction mechanism.

Usually, sensors exhibit a nonlinear performance decline over time: initial fouling may have little effect, but once a critical fouling threshold is reached, a rapid and disproportionate decrease in sensitivity, stability, and lifespan occurs. Such behaviour can be visualized and monitored in real time [83].

In aquaculture water monitoring, electrochemical methods, particularly EIS and potentiometric analysis, are well suited for continuous observation of sensor stability in RAS loops. Detecting impedance changes or potential shifts in situ allows early recognition of biofilm growth and supports timely sensor maintenance, reducing the risk of inaccurate pH or ammonium readings that could endanger fish health. A comparison of different fouling detection methods for ISE is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of methods to detect fouling on ISE regarding response time, maintenance frequency, cost, tolerance to salinity and temperature, and durability.

6.3. Potentiometric Evaluation of Fouling Effects

The functionality of ISEs can be evaluated using potentiometric measurements by recording electrode responses at various standard concentrations [98]. Changes caused by fouling can be identified through variations in electrode slope, while electrode ageing can be indicated by a gradual increase in internal resistance. For example, the slope of a new electrode may decrease from 60 mV/decade in a standard solution to 40 mV/decade after extended use, indicating a measurable degree of fouling [99]. Temperature control is essential during such measurements, as a 10 K variation can approximately double the electrical resistance.

A straightforward method for fouling detection involves measuring the direct current (DC) resistance of the ion-selective membrane. Fouling correlates proportionally with increasing resistance until a critical threshold is reached, after which the resistance rises sharply. Typical membrane resistance values are 10–20 MΩ for membranes containing functional ionophores, 2–4 MΩ for those with ion-exchanger inclusion, and 300 MΩ for membranes without ionophores [100].

A promising in situ technique combines potentiometry with null ellipsometry, allowing real-time monitoring of biofouling via both the electrode potential and the corresponding ellipsometric signal, which reflects the amount of adsorbed protein (e.g., bovine serum albumin) [86]. Chronopotentiometry is another electrochemical method in which a controlled current is applied between two electrodes, and the potential of one electrode is measured over time relative to a reference electrode. Fouling of ISEs leads to changes in the bulk resistance of the electrode, making chronopotentiometry a useful tool for evaluating membrane resistance and fouling progression [101,102].

For aquaculture monitoring, potentiometric analysis is particularly relevant, as it directly evaluates sensor performance under real-water conditions. Continuous observation of electrode slopes and resistance trends can serve as diagnostic indicators for biofilm growth or salt deposition, both of which affect the accuracy of nutrient and oxygen monitoring in intensive aquaculture systems.

6.4. Amperometric Detection and Fouling Assessment

Amperometry is an electrochemical technique used to determine the concentration of redox-active species [103]. Pulsed amperometry, employing a periodic voltage waveform, enhances sensor robustness and can even serve as an electrochemical cleaning method for noble metal electrodes [104]. Fouling of Clark-type dissolved oxygen sensors can be assessed by measuring the oxygen transfer time across the membrane of the Clark cell. In this approach, one electrode operates continuously under steady-state conditions for oxygen detection, while another is energized intermittently to detect fouling effects. However, this method still requires reference calibration (lookup tables) to compensate for fouling-induced deviations [105].

Within aquaculture, amperometric approaches are essential for maintaining accurate dissolved oxygen readings. Since oxygen is a critical parameter in RAS operation, detecting membrane fouling through amperometric signals allows proactive cleaning or recalibration, ensuring stable oxygen supply for aquatic organisms.

6.5. Voltametric Techniques for Evaluating Electrode Fouling

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) is an electrochemical technique in which the potential of the working electrode is cyclically varied while the resulting current is recorded relative to a reference electrode [106]. This method has been widely used to determine fouling rates on various electrode materials, including carbon electrodes [107] and reference electrodes such as Ag/AgCl [108]. Applied to aquaculture sensors, cyclic voltammetry could serve as a diagnostic method to assess the degree of electrode passivation or biofilm formation on reusable sensor tips, supporting the design of maintenance schedules and surface treatment protocols for long-term use.

6.6. Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for Real-Time Fouling Monitoring

Electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is a well-established technique for detecting and quantifying fouling. It has been applied to real-time monitoring of fouling in membrane processes [109] and can also be used to assess fouling on electrode surfaces, as fouling layers alter the magnitude and phase of the impedance response [110]. Fouling-induced changes in impedance provide direct insight into surface deposition phenomena within sensor housings [110]. EIS can also indicate biofilm formation by applying a sinusoidal voltage signal to the electrode and monitoring the temporal response; variations in impedance spectra correspond to microbial growth and biofilm development [97]. Additionally, EIS enables the determination of fouling layer thickness by quantifying the electrical resistance associated with the deposited film. Experimental results have shown that biofouling contributes to the overall charge transfer resistance of ion-selective electrodes, thereby reducing ion permeability and impairing signal stability [111].

In aquaculture environments, EIS is particularly promising for non-invasive, real-time evaluation of sensor integrity. Continuous impedance tracking could provide early warning of biofilm buildup on ISEs, allowing corrective actions before data drift impacts automated control of water quality and fish health.

6.7. Critical Comparison of Fouling Detection Methods

As mentioned, various methods can be used to detect fouling on surfaces, like ISE-type sensors, but only a few are suitable for aquacultures and even fewer work inline. Highly sensitive laboratory equipment (QCM, SPR, SEM, AFM) provide reproducible, highly valued information, but are difficult to operate and need specialized equipment and sample preparation, hence providing a rather laboratorial approach. Optical methods are partly practical for aquacultures; their insensitivity (UV/VIS, turbidity) can lead to falsified conclusions, while other methods (fluorescence microscopy) require expensive equipment and/or dyes. Electrochemical methods are quite suitable for real-time monitoring of fouling on ISEs and are field-proven, whilst EIS is very sensitive and detects biofilm growth; however, additional hardware is needed, as well as expertise in evaluation. Potentiometric fouling detection is quite simple and provides only general fouling information without distinguishing between different fouling types.

7. Regeneration and Cleaning Methods for Ion-Selective Electrodes

The long-term operation of ISEs often results in surface contamination through organic, inorganic, and biological deposits that impair sensor accuracy, response time, and stability. Cleaning and regeneration methods are therefore essential to restore the electrode’s functionality by removing or mitigating accumulated foulants and reestablishing baseline performance. These methods differ in mechanism and intensity—ranging from mechanical and chemical to electrochemical or acoustic cleaning approaches—and are selected based on the electrode type and the nature of fouling. In aquaculture applications, where sensors are continuously exposed to nutrient-rich and biologically active media, effective regeneration protocols are indispensable to maintain measurement reliability and ensure accurate monitoring of critical parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen, and ammonium.

Hereby it is necessary to differentiate between reversible and irreversible sensor fouling. Reversible fouling refers to foulants which can easily be removed (e.g., with preconditioning and routine maintenance) like conditioning a CO32−-ISE for 15 h in Na2CO3 after being fouled by sodium alginate to regain the initial slope response, while irreversible fouling (like slime or macrofouling) cannot be cleaned off easily and needs further cleaning methods, such as mechanical, chemical, physical (and ultrasonic), electrochemical, integrated, and advanced cleaning methods [31].

7.1. Electrode Preconditioning and Routine Maintenance

Sensor drift and electrode dissolution can be mitigated by conditioning the ion-selective electrode in the sample matrix before measurements [78]. Additionally, electrodes can be rinsed or equilibrated in a low-analyte concentration solution between measurements to restore the baseline potential [112]. Reversible foulants can be removed via this method. Frequent cleaning and recalibration are essential for ISEs used in long-term monitoring applications, as they maintain sensor stability and measurement accuracy [112].

In aquaculture systems, where sensors are continuously exposed to nutrient-rich and biologically active water, regular conditioning and recalibration are vital to sustain data reliability. Frequent cleaning between measurement cycles minimizes biofilm accumulation and stabilizes readings of key parameters such as pH and ammonium, ensuring accurate process control and safeguarding aquatic species in RAS.

7.2. Mechanical Cleaning Approaches

Mechanical cleaning—such as the use of wipers or brushes—is an effective method for removing biofouling without damaging sensitive sensor components. Such systems should be designed to be removable or replaceable for long-term deployment [31,71].

Once a critical fouling degree is reached, foulants tend to adhere irreversibly even outside the sample matrix. Therefore, crystalline ISEs (e.g., pH glass electrodes) often require mechanical polishing, whereas polymeric ISEs typically demand membrane replacement [112]. Water jet cleaning has also been established for removing superficial deposits from non-delicate sensor components [71].

In aquaculture applications, mechanical cleaning systems, such as automated wipers integrated into submerged sensor probes, can significantly reduce biofouling during continuous operation. The ability to remove accumulated biomass without disassembling sensors is particularly beneficial for RAS environments, where uninterrupted real-time monitoring of water quality is essential.

7.3. Chemical Cleaning and Regeneration

For solid-state ISEs, chemical cleaning agents can restore electrode performance.

- Ascorbic acid treatment of sulphate-contaminated membranes reestablishes electrode response.

- Perchloric acid (HClO4) effectively removes lead sulphate and oxide layers.

- Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) dissolves lead sulphate and enhances lead oxide removal efficiency [26].

Since fouling composition varies depending on the operating environment, cleaning protocols must be specifically tailored to the predominant foulants. Routine physical or chemical cleaning, followed by post-cleaning performance testing, ensures regeneration effectiveness and reproducibility.

In aquaculture environments, chemical regeneration protocols must consider the complex composition of organic and biological foulants, including proteins, polysaccharides, and microbial biofilms. Customized cleaning procedures employing mild and biocompatible reagents, such as diluted EDTA solutions or organic acids, are essential to preserve sensor functionality while preventing the introduction of toxic residues into the aquatic system.

7.4. Physical and Ultrasonic Cleaning Techniques

Alternative cleaning techniques from other industries can be adapted for sensor regeneration. Ultrasonic irradiation has been demonstrated to control biofilm formation, enhance the efficiency of biocides, and facilitate biofilm detachment. Similarly, low-frequency acoustic vibration disrupts larvae attachment and prevents resettlement on sensor surfaces [38].

For aquaculture monitoring systems, physical cleaning methods such as ultrasound present promising non-invasive options for in situ maintenance. Ultrasonic waves can loosen biofilms and particulate fouling without requiring chemical exposure, reducing maintenance time and preventing contamination risks in live fish tanks.

7.5. Electrochemical Cleaning and In Situ Fouling Control

Electrochemical fouling control mitigates fouling by in situ generation of biocides near the electrode surface or by modifying electron transport through the fouling layer [38]. This method can function both as a preventive and regenerative strategy and has shown promise for solid-contact ISEs operating in complex aqueous environments.

In the context of aquaculture, electrochemical cleaning could be integrated into smart sensor platforms to periodically remove surface deposits through controlled potential pulses. This approach allows autonomous regeneration of electrodes and extends operational lifespan under biofouling-prone conditions characteristic of RAS water loops.

7.6. Integrated and Advanced Regeneration Strategies

Chemical cleaning agents such as chlorine, acids, and alkalis are widely used for general fouling removal. However, some of these agents (e.g., chlorination in cooling systems) can produce harmful by-products such as trihalomethanes [71]. Emerging environmentally friendly strategies include the use of bio-based antifouling agents, such as naturally secreted enzymes or extracellular compounds that inhibit the formation of fouling layers.

Because no single cleaning approach fully removes or prevents fouling, combined cleaning strategies, integrating physical, chemical, acoustic, and electrochemical methods, offer the most effective and sustainable long-term antifouling solutions for ion-selective electrodes.

Hybrid cleaning approaches are particularly advantageous for aquaculture systems, where combining gentle physical cleaning methods (e.g., wiping or ultrasound) with periodic electrochemical or enzymatic regeneration minimizes downtime and prevents biofilm stabilization. Sustainable, non-toxic cleaning routines are crucial for maintaining water quality and ensuring compliance with environmental safety standards in fish production environments.

7.7. Critical Comparison of Cleaning Methods

Cleaning methods for fouled ISEs differ widely in their practicability, effectiveness, and impact on the sensor. For long-term usage of ISEs, proper cleaning routines should be established. A list of compared cleaning methods is represented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of methods to clean fouling on ISEs.

Widely spread chemical cleaning is effective against inorganic and organic foulants, but may lead to harsh conditions damaging the sensor (e.g., plasticizer or ion exchanger of ISM). Mild chemicals can be sufficient for sensor cleaning whilst creating neglectable sensor changes, but maintenance frequency or duration may be higher.

The compatibility rating (“safe”, “medium”, “not safe”) refers to the chemical stability of conventional ISE membrane materials exposed to cleaning agents (Table 7).

Table 7.

Comparison of cleaning agents and their compatibility to different materials used in ISE.

The same problem may appear with mechanical cleaning, as wipers or polishing may cause harm to the membrane of the ISE. Enzymatic cleaning methods may be gentler, but are more expensive and tend to work in limited operational ranges with limited stability.

A promising approach is given by electrochemical cleaning methods, as they require no chemical reagents and can be integrated into ISE construction. This approach remains quite experimental, as there are not many sensors with built-in electrochemical cleaning methods.

For RAS, a cleaning method consisting chemical cleaning (conditioning or mild reagents) as well as gentle mechanical cleaning (wiping or polishing) should be considered. Future ISE manufacturers should integrate built-in self-cleaning strategies, like electrochemical cleaning.

8. Antifouling Strategies for Ion-Selective Electrodes

While regeneration methods focus on restoring sensor performance after fouling has occurred, preventive antifouling strategies aim to minimize or entirely prevent foulant accumulation on ISEs. Such measures are particularly valuable for long-term monitoring applications, as they extend sensor lifetime, reduce maintenance frequency, and ensure consistent data quality in complex aquatic environments, though they differ in durability and response time effects.

In RAS, where sensors operate continuously under nutrient-rich and biologically active conditions, preventive strategies are essential to maintain stable monitoring of key parameters such as pH, ammonium, and dissolved oxygen.

Preventive antifouling concepts have been widely developed and implemented across various industrial sectors, including membrane technology [113], heat exchangers [114], and sensor systems [4,31,71,89,115,116,117,118,119,120]. Although many biocidal antifoulants are highly effective, their environmental and health impacts, particularly their non-selective toxicity [121], have driven a shift toward sustainable, environmentally compatible alternatives [122].

8.1. Fundamentals and Mechanisms of Fouling Prevention

Fouling is primarily driven by the physicochemical characteristics of sensor surfaces, including surface roughness, hydrophilicity, surface charge, and surface free energy [4]. Furthermore, the presence of a hydration layer, the ionic strength and pH of a medium, and the exposure towards the medium and light (e.g., UV) influence fouling characteristics. Thus, antifouling effectiveness depends heavily on the choice of sensor materials, surface modification, and coating technologies. Preventive measures also include sample pretreatment, controlled process environments, and optimized calibration routines [4].

In aquaculture monitoring, where high biological activity promotes biofilm formation, controlling these parameters directly influences sensor reliability and reduces the need for frequent recalibration. Coatings or thin films are the most frequently described antifouling methods in the literature [85]. Nature-inspired approaches, such as limiting light exposure to inhibit algal growth, can provide simple, passive antifouling solutions. In practical applications, reducing exposure time (e.g., immersing sensors only during measurement) can further minimize fouling on ISEs [71]. Antifouling systems can generally be classified as biocidal, biomimetic, micro-textured, superhydrophobic, hydrophilic, amphiphilic, hybrid, or active cleaning systems [123].

8.2. Selection of Antifouling Construction Materials for ISEs

The selection of materials for ISE construction determines both mechanical durability and fouling resistance. Common sensor bodies include glass electrodes for standard pH or Na+ measurements; bronze or antimony electrodes for industrial applications [124]; enamelled steel probes for extreme conditions [125]; and optical or hydrogel-based pH probes for specialized systems [126,127].

In aquaculture systems, where sensors are exposed to high salinity variations and organic loading, robust materials such as enamelled steel or carbon composites are particularly advantageous for long-term stability.

Fouling typically results from adsorption of organic molecules or biological cells, leading to signal deterioration and reduced performance [4]. Nanoporous carbon electrodes show superior fouling resistance because large foulants are sterically hindered from entering internal pores [85].

Recent developments focus on carbon-based materials, such as graphene, diamond, and carbon composites, which exhibit high chemical inertness, low protein and lipid affinity, easy surface functionalization, and electrocatalytic activity. These materials are well suited for long-term and in situ measurements [85]. Diamond, e.g., excels in fast response time due to high conductivity, whilst carbon composites show a moderate drift and good biofouling resistance.

Enamelled steel sensors demonstrate outstanding sensitivity and longevity by forming a self-renewing leaching layer that regenerates every one to two weeks in acidic or neutral media. Depending on layer thickness, lifetimes can exceed 100 years, while showing high resistance to solvents, oils, and temperature shocks [125,128]. Thus, enamelled steel excels in durability with a negligible influence on response time. Further promising sensor materials include diamond [129,130,131,132], antimony [133,134], and stainless steel alloys [135,136,137,138]. A list of possible materials for ISE construction is listed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Comparison between possible materials for ISE construction.

8.3. Surface Modification Strategies for ISEs

A promising route to mitigate fouling is surface modification of the ion-selective membrane. Key antifouling characteristics, such as protein resistance, hydrophilicity, zwitterionic behaviour, and biocompatibility, are achieved by tailoring the surface chemistry and topography [116]. The combination of physical (e.g., roughness, charge) and chemical (e.g., coatings, grafted polymers) modifications can create synergistic antifouling effects, preventing microbial settlement and facilitating biofilm detachment [139]. In RAS environments, such surface-modified ISEs can maintain accuracy over longer intervals, reducing sensor replacement frequency and improving operational efficiency.

8.3.1. Physical Surface Modification

Antifouling can be achieved by modifying exposed surfaces to reduce surface energy, introduce repulsive interactions with foulants, or control micro texture [140]. Surface roughness plays a decisive role: smoother surfaces generally reduce bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation, while increased roughness may enhance fouling and affect ion adsorption, selectivity, and membrane charge [111,141]. Surface roughness can be tuned by incorporating additives such as 5% PTFE into polymeric ion-selective membranes [111], which is suitable for production and use in aquaculture.

Biomimetic approaches inspired by marine organisms, such as shark placoid scales, pilot whale skin pores, or dolphin skin elasticity, provide antifouling functionality through micro- and nanostructures, but remain mostly experimental [71,142]. Other natural analogues include fish scales, crab shells, butterfly wings, and tree frog toe pads, which exhibit self-cleaning or anti-adhesive properties [142]. Additionally, modifying the surface charge toward more negative values reduces bacterial adhesion [111], while low-surface-energy coatings hinder microbial bonding and biofilm development [143]. These micro-structured and low-energy surface modifications are especially beneficial for sensors submerged in aquaculture tanks, where bacterial attachment rates are high.

Photocatalytic self-cleaning coatings based on anatase TiO2 exhibit strong antimicrobial and anti-organic fouling properties. Under UV illumination, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated, degrading organic contaminants into water and carbon dioxide [76]. These coatings also form superhydrophilic films, further inhibiting organic adhesion and enhancing antifouling stability on ISE surfaces, but remain semi-practical due to the necessity of UV light [92].

8.3.2. Chemical Surface Modification

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) remains a widely used surface modifier due to its low cost and ready availability. However, zwitterionic coatings have recently gained attention for their superior antifouling performance, offering higher oxidation stability, lower immunogenicity, and improved biocompatibility compared to PEG [116]. Further chemical modifications include metallic nanoparticles, catalytic redox couples, nanoporous electrodes, and polymeric or non-polymeric films, all adaptable for ISE applications [85]. E.g., for biofouling prevention, ISEs coated with copper- and zinc-based layers achieved an average 59% reduction in biofilm formation [84].

Such modifications not only enhance antifouling resistance but also improve electrical stability and ion selectivity of the electrode interface. In aquaculture sensor systems, these coatings have proven to help maintain calibration stability even in biologically active water. To counter oil fouling on ISEs, zwitterionic polymer-based self-cleaning coatings have been developed and successfully applied to calcium ISEs, demonstrating durable antifouling performance [89].

8.4. Antifouling Coatings and Functional Films for ISEs

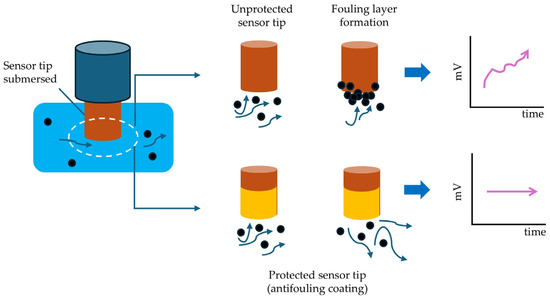

Antifouling coatings serve as physical and chemical barriers between the electrode surface and the surrounding medium, as seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of fouling (drifting) and antifouling (no drift) phenomena on the measuring tip of an ion-selective electrode (ISE), showing protected (yellow, repellent) vs. unprotected (orange, not repellent) surfaces, according to [31].

According to Dafforn et al. (2011), four main coating types are used in marine fouling control: (i.) soluble-matrix coatings, (ii.) contact-leaching coatings, (iii.) self-polishing copolymers, and (iv.) foul-release coatings [69].

For ISEs, current developments include non-stick coatings [38], biocide-impregnated layers [71], magnetic coatings [144], self-sterilizing coatings [145], and maintenance-free, self-polishing polymeric membranes [146]. These coatings minimize direct contact between the sensor surface and foulants. For aquaculture-monitoring probes, such coatings are essential to prevent rapid fouling in nutrient-rich, bioactive waters and to minimize maintenance intervals. However, many traditional antifouling paints release toxic substances into aquatic environments. One historically significant compound is tributyltin (TBT), once the most effective antifouling agent used in marine paints. Due to its extreme toxicity, bioaccumulation, and severe ecological impacts, TBT was banned globally under the IMO “International Convention on the Control of Harmful Anti-Fouling Systems on Ships”. This prohibition marked a fundamental shift toward tin-free and environmentally benign coatings.

Modern antifouling coatings now rely on silicone-based foul-release systems, fluoropolymers, and hydrophilic or zwitterionic polymer films. Biocide-free and naturally derived materials, such as chitosan, cellulose derivatives, and marine-organism extracts, are increasingly used to provide long-term stability with minimal environmental impact [69,147]. Although some coatings still require periodic renewal, embedded additives (e.g., biocides, fungicides, herbicides) continue to support active fouling prevention when applied in safe concentrations.

8.5. Emerging and Bioinspired Antifouling Concepts

Bioinspired antifouling strategies draw from natural defence mechanisms that prevent surface colonization in marine organisms.

- Hydration-layer formation prevents protein adsorption and microbial attachment.

- Micro- and nanostructured surfaces derived from sharks, molluscs, and lotus leaves minimize effective contact areas for biofilms.

- Bioengineered polymers incorporating natural antifouling moieties, such as zwitterions, amino acids, or peptides, represent a sustainable route for future sensor designs.

Hybrid systems combining physical texturing with chemical functionality often achieve synergistic effects, enhancing fouling resistance, self-cleaning ability, and sensor longevity under real operating conditions. Such bioinspired coatings could be directly applied to long-term aquaculture probes, improving monitoring accuracy and reducing manual maintenance. Whilst only superhydrophilic and hydrophilic zwitterionic coatings for use in aquaculture exist, micro-structured surfaces, self-cleaning surfaces, and fish-scale/shark-skin patterns fail to be implemented in aquacultures due to the difficulty of mass production for electrodes, experimental and pre-commercial conditions.

8.6. Environmentally Friendly Antifoulants and Emerging Coating Materials

Growing awareness of the environmental impact of toxic antifouling agents has accelerated research into non-toxic and naturally derived alternatives, particularly in the maritime sector. Modern foul-release coatings frequently employ silicone elastomers, waxes, or oils, while bio-based antifoulants are often derived from marine organisms, such as algae [69]. Typical foul-release materials used in marine applications include silicones, fluoropolymers, and silicone hydrogels [69]. For aquaculture sensors, these environmentally benign coatings are especially valuable to avoid toxic leaching into fish tanks.

Recent studies also explore specialized hydrogels and bacteria-producing extracellular antifouling components as potential alternatives. However, these approaches face challenges such as inconsistent antifouling performance and the complex maintenance of living antifouling systems [71]. The range of antifoulants reported in the literature, including natural compounds, foul-release materials, polymeric and photocatalytic coatings, and metallic or zwitterionic systems, is summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Overview of antifoulant types, sensor applications, and related findings reported in the literature.

Because some organisms (e.g., certain algae) tolerate copper-based antifoulants, booster biocides are often incorporated into paints to enhance efficacy. These coatings are preferred in RAS as they do not release toxic metals, have no pH-dependent toxicity, do not interfere with sensor signals, and in general do not leach toxins that pose mortality risks to the cultivated organism, while also meeting sustainability requirements and thus regulatory pressure.

8.7. Ionic Liquids

To prevent leaching and drifting, multifunctional additives called ionic liquids are used. These liquids are used to exchange conventional lipophilic salts (e.g., KTFPB, DOS, NPOE), which results in less leaching/washing out, a stabilized membrane matrix with less pores and hence less biofilm adhesion, and smoother homogenous surfaces preventing adsorption of proteins and extracellular polymeric substances. Ionic liquids work as ion exchangers, transducers and plasticizers simultaneously, providing a stabilized Nernst slope, less drifting, and less membrane ageing.