Enhancements and On-Site Experimental Study on Fall Detection Algorithm for Students in Campus Staircase

Abstract

1. Introduction

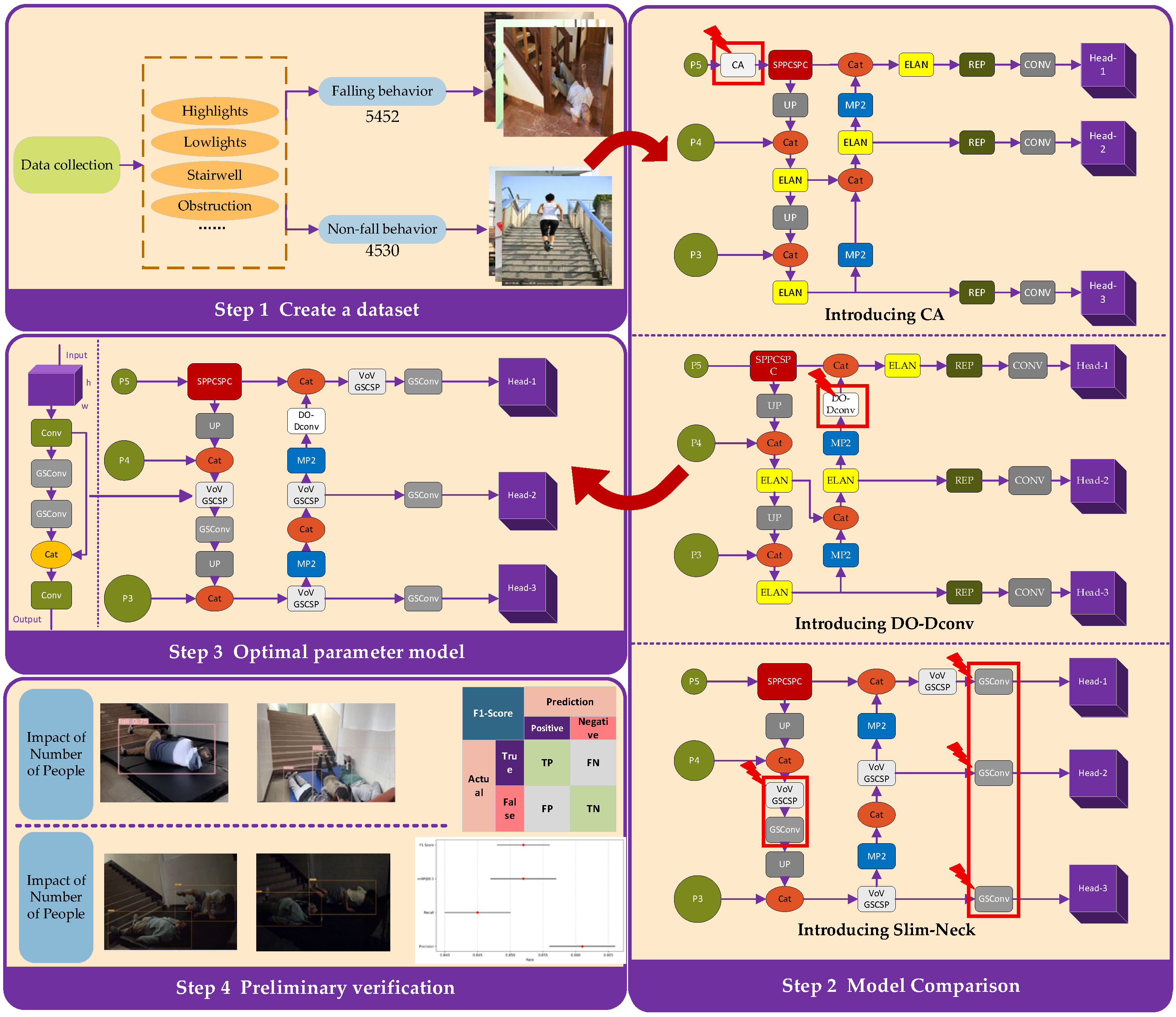

2. Methods

2.1. Establish a Campus Staircase Fall Dataset

2.2. Comprehensive Improvement Scheme for Campus Staircase Fall Recognition Model

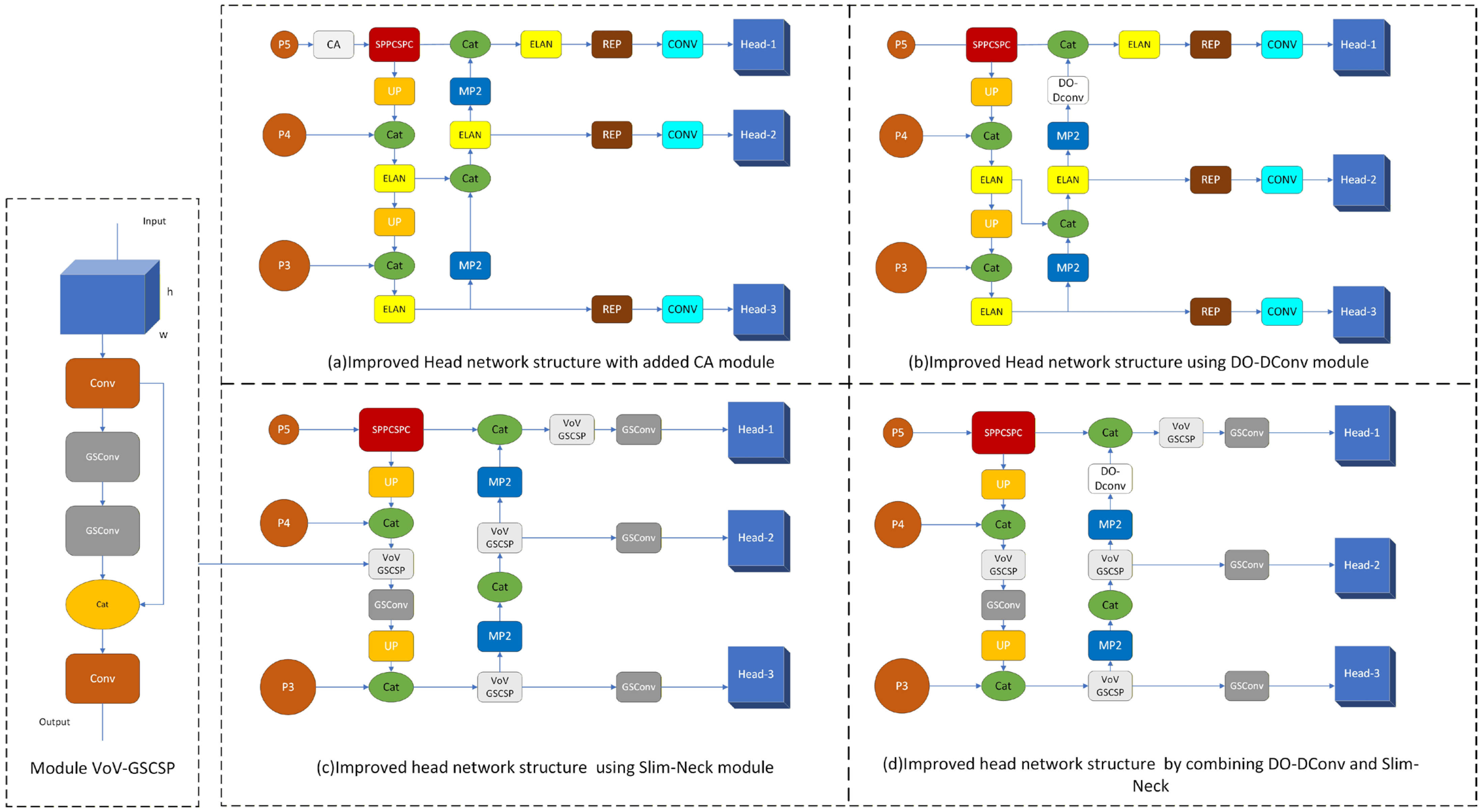

2.2.1. Improved YOLOv7 Algorithm Combined with CA

2.2.2. Improved YOLOv7 Algorithm Combined with DO-DConv

2.2.3. Improved YOLOv7 Algorithm Combined with Slim-Neck

- (1)

- Replace SC with the lightweight convolution method GSConv. The calculation cost of GSConv is only 60% to 70% of that of SC.

- (2)

- The cross-stage partial network (GSCSP) module VoV-GSCSP is designed using a one-time aggregation method, which reduces the complexity of computation and network structure while maintaining sufficient precision, as shown in Figure 2. Usually, to effectively reduce FLOPs, VoV-GSCSP modules can be used to replace the ELAN and REP modules in the Neck layer [37].

2.2.4. Improved YOLOv7 Algorithm Combining DO-DConv and Slim-Neck

2.3. Numerical Experiments

2.3.1. Numerical Experiment Purpose and Environment

2.3.2. Model Training

2.4. Preliminary Validation

2.4.1. Preliminary Validation Purpose and Scheme

- (1)

- Experimental groups with different numbers of people.

- (2)

- Different experimental groups under different luminance conditions.

2.4.2. Experimental Software

2.4.3. Experimental Process

- (1)

- Open the object detection tool, click ‘Select Weights’, and select the best trained model, which is best. pt.

- (2)

- Click on ‘Initialize Model’. When ‘Model loading completed’ appears, proceed to the next step.

- (3)

- Click on ‘Camera Detection’.

- (4)

- Participants start the experiment, and each experimental scheme is conducted 10 times.

- (5)

- After completing the action, click ‘End Detection’. Repeat steps 3 and 4 until all participants have completed the corresponding number of groups in the experiment.

3. Results

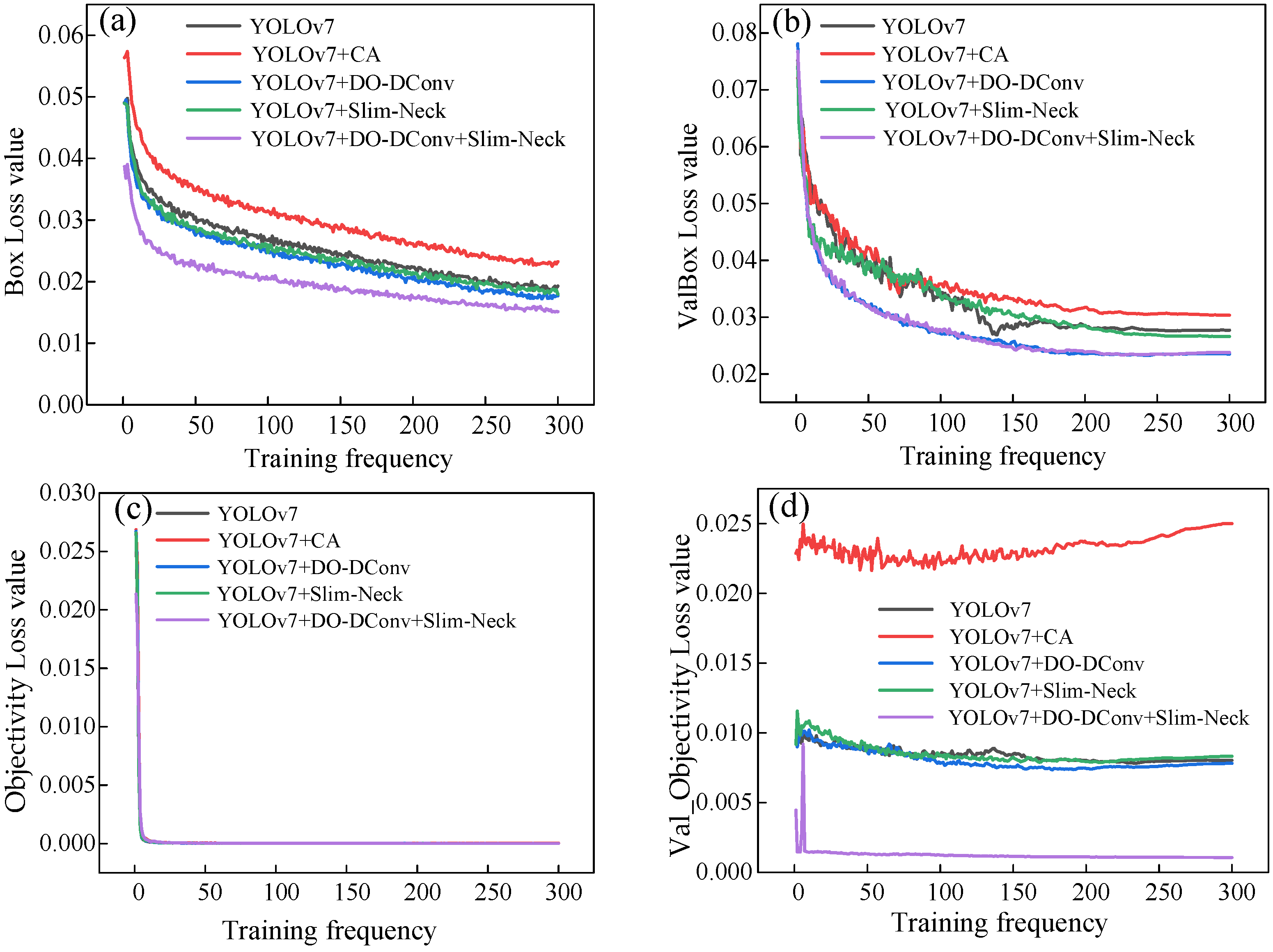

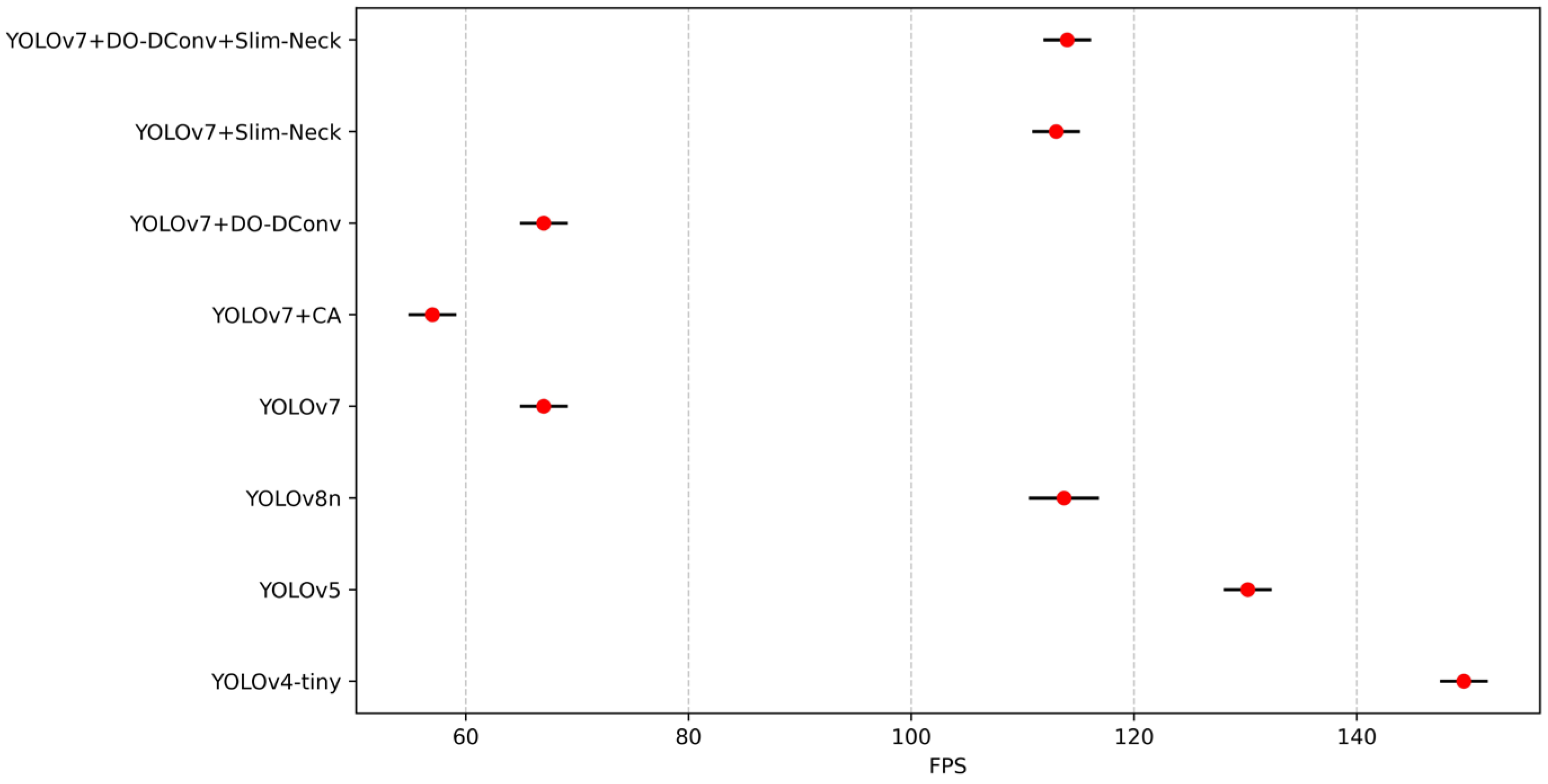

3.1. Numerical Experimental Results

3.2. Preliminary Validation Results

- (1)

- Different groups with different numbers of people.

- (2)

- Different luminance groups.

4. Discussion

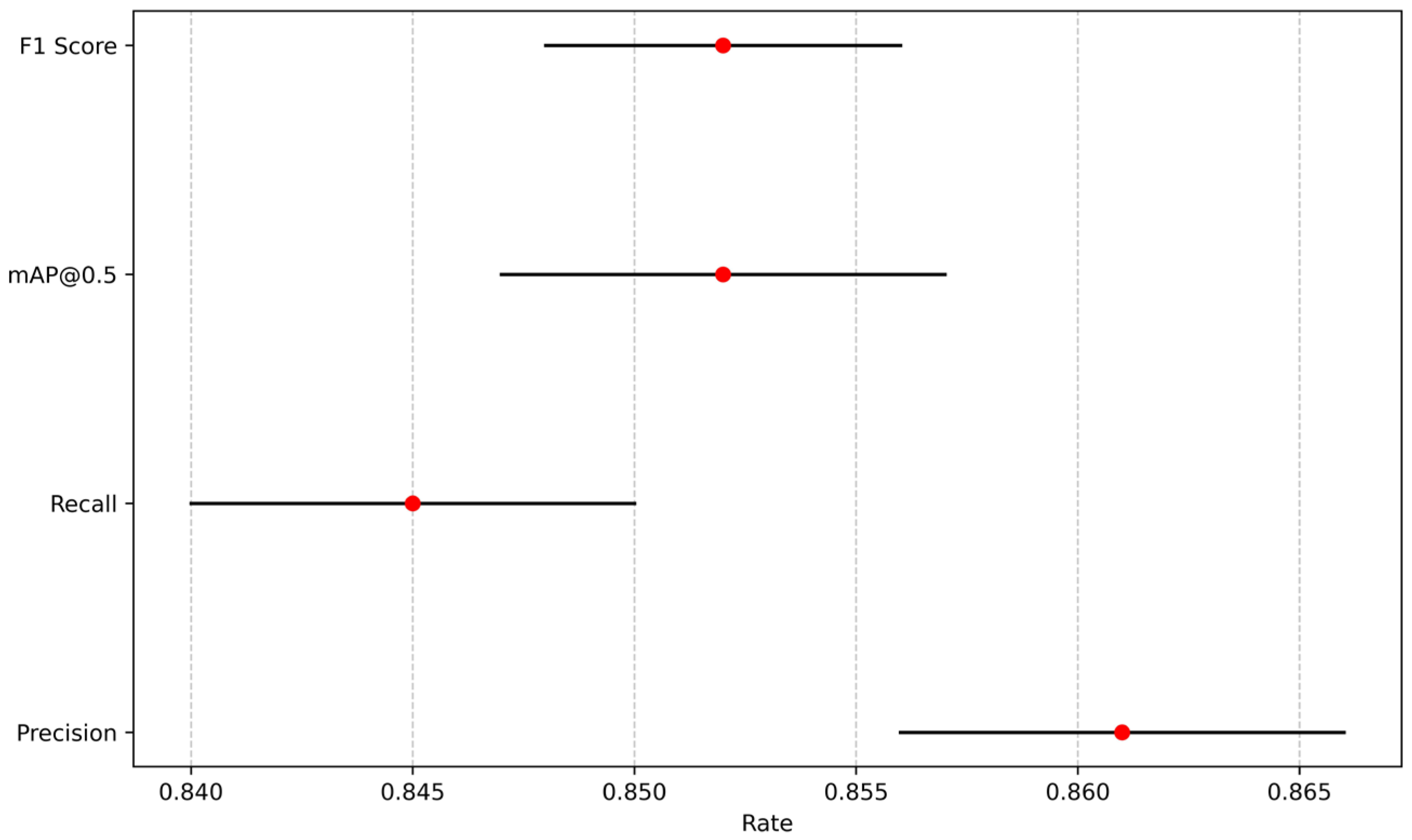

4.1. Performance Comparison of the Different Models

4.2. Analysis of the Impact of Population Changes

4.3. Analysis of the Impact of Changes in Light Intensity

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, M.; Dong, H.; Zhao, Y.; Ioannou, P.A.; Wang, F.-Y. Optimization of crowd evacuation with leaders in urban rail transit stations. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 4476–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gong, J.; Yu, P.; Shen, S. Modeling, simulation and analysis of group trampling risks during escalator transfers. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2016, 444, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lu, T.; Jiao, W.; Shi, C. An extended model for crowd evacuation considering crowding and stampede effects under the internal crushing. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2023, 625, 129002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-l.; Zhou, X.-b. The occurrence laws of campus stampede accidents in China and its prevention and control measures. Nat. Hazards 2017, 87, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Xie, Z. Study on campus stampede causes and prevention based on 24Model-AHP. Safety 2022, 43, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Song, Y.; Liu, J.; Liang, B.; Liu, X. Stampede Prevention Design of Primary School Buildings in China: A Sustainable Built Environment Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, E.; Sufian, A.; Dutta, P.; Leo, M. Vision-based human fall detection systems using deep learning: A review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 146, 105626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.-C.; Chen, M.-J.; Lee, C.-H.; Kung, L.-C.; Huang, J.-T. Fall recognition based on an IMU wearable device and fall verification through a smart speaker and the IoT. Sensors 2023, 23, 5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Hu, S. Skeleton-based fall detection with multiple inertial sensors using spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; Liu, H.; Qu, D.; Zhang, Z. Human falling detection algorithm based on multisensor data fusion with SVM. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2020, 2020, 8826088. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Ni, X.; Zhao, G.; Ma, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, H.; Xiong, C.; Wang, L.; Liang, S. A wearable action recognition system based on acceleration and attitude angles using real-time detection algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2017 39th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 11–15 July 2017; pp. 2385–2389. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, N.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, X.; Jin, Z. Falling motion detection algorithm based on deep learning. IET Image Process. 2022, 16, 2845–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, H.; Xue, B.; Zhou, M.; Ji, B.; Li, Y. Depth-Based Human Fall Detection via Shape Features and Improved Extreme Learning Machine. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2014, 18, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medel, J.R.; Savakis, A. Anomaly Detection in Video Using Predictive Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.00390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultani, W.; Chen, C.; Shah, M. Real-World Anomaly Detection in Surveillance Videos. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 6479–6488. [Google Scholar]

- Quinayás Burgos, C.A.; Quintero Benavidez, D.F.; Ruíz Omen, E.; Narváez Semanate, J.L. Sistema de detección de caídas en personas utilizando vídeo vigilancia. Ingeniare. Rev. Chil. De Ing. 2024, 28, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, F.; Gao, S.; Chang, C.; Zhang, X. Experimental and Numerical Study on Rapid Evacuation Characteristics of Staircases in Campus Buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, J.; Krüger, T.; Röhling, H.M.; Jelusic, A.; Mansow-Model, S.; Schniepp, R.; Wuehr, M.; Otte, K. Accuracy and repeatability of the Microsoft Azure Kinect for clinical measurement of motor function. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, X.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, C. A Lightweight Human Fall Detection Network. Sensors 2023, 23, 9069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Huaping, D. Research on artificial intelligence early warning and diversion system for campus crowding and stampede accidents. Informatiz. Res. 2021, 47, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, P.; Qian, H.; Chu, S. SlimYOLOv4: Lightweight object detector based on YOLOv4. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2022, 19, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjalawe, Y.; Makhadmeh, S.N.; Almiani, M.; Al-E’Mari, S. HyperFallNet: Human Fall Detection in Real-Time Using YOLOv13 with Hypergraph-Enhanced Correlation Learning. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 177111–177126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjalawe, Y.; Fraihat, S.; Abualhaj, M.; Al-E’Mari, S.R.; Alzubi, E. Hybrid Deep Learning for Human Fall Detection: A Synergistic Approach Using YOLOv8 and Time-Space Transformers. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 41336–41366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Wu, H.; Li, Y. Fall Detection in Videos with Trajectory-Weighted Deep-Convolutional Rank-Pooling Descriptor. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 4135–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Yao, C.; Min, W.; Han, Q.; He, K.; Yang, Z.; Lei, X.; Guo, B. A novel fall detection framework with age estimation based on cloud-fog computing architecture. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 24, 3058–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. An Improved YOLOv7 Lightweight Detection Algorithm for Obscured Pedestrians. Sensors 2023, 23, 5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, H.; Qi, W.; Xie, H. Little-YOLOv4: A Lightweight Pedestrian Detection Network Based on YOLOv4 and GhostNet. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 5155970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shan, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y. Patient-level anatomy meets scanning-level physics: Personalized federated low-dose ct denoising empowered by large language model. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 5154–5163. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.T.; Huang, C.-L.; Hsu, S.-C. Slip and fall event detection using Bayesian Belief Network. Pattern Recognit. 2012, 45, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiang, X. DBF-YOLO: A fall detection algorithm for complex scenes. Signal Image Video Process. 2025, 19, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Marinov, Z.; Baur, R.; Zhong, Z.; Düger, R.; Stiefelhagen, R. OmniFall: A Unified Staged-to-Wild Benchmark for Human Fall Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.19889. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13713–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z. Improved YOLOv7 for small object detection algorithm based on attention and dynamic convolution. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Xu, W. Insulator-defect detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv7. Sensors 2022, 22, 8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, M.; Chen, Y.; Lischinski, D.; Cohen-Or, D.; Chen, B.; Tu, C. DO-Conv: Depthwise Over-Parameterized Convolutional Layer. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 3726–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, Q. Slim-neck by GSConv: A better design paradigm of detector ar-chitectures for autonomous vehicles. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.02424. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Wan, Q.; Tian, S.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J. Equipment Identification and Localization Method Based on Improved YOLOv5s Model for Production Line. Sensors 2022, 22, 10011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Act | Examples of Partial Dataset Images | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Falling | Falling forward | Falling backward | Falling sideways | ||

|  |  | |||

| Non falling | Running | Walking | Standing | Squatting | |

|  |  |  | ||

| Obstruction |  |  |  | ||

| Actions in the Dark |  |  |  | ||

| Falling down the stairs |  |  |  | ||

| Serial Number | Improvement Scheme | Dataset | Performance Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | YOLOv7 + CA | Self-Constructed Dataset | Precision, recall rate, mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95, F1 score Model complexity: GPU consumption, Parameter quantity, GFLOPs, training duration |

| 2 | YOLOv7 + DO-DConv | ||

| 3 | YOLOv7 + Slim-Neck | ||

| 4 | YOLOv7 + DO-DConv + Slim-Neck |

| Illuminance | Experimental Group Number | Experimental Group Number | Forward Fall | Backward Fall | Sideways Fall | The Number of Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 422 lux | A | 1 | A | 10 | ||

| 2 | A | 10 | ||||

| 3 | A | 10 | ||||

| A, B | 4 | A | B | 10 | ||

| 5 | A | B | 10 | |||

| 6 | A | B | 10 | |||

| 7 | A, B | 10 | ||||

| 8 | A, B | 10 | ||||

| 9 | A, B | 10 | ||||

| A, B, C | 10 | A, B, C | 10 |

| Illuminance | Experimental Group Number | Forward Fall | Backward Fall | Sideways Fall | The Number of Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 lux | 11 | A | B | 10 | |

| 12 | A | B | 10 | ||

| 13 | A | B | 10 | ||

| 14 | A, B | 10 | |||

| 15 | A, B | 10 | |||

| 16 | A, B | 10 | |||

| 2 lux | 17 | A | B | 10 | |

| 18 | A | B | 10 | ||

| 19 | A | B | 10 | ||

| 20 | A, B | 10 | |||

| 21 | A, B | 10 | |||

| 22 | A, B | 10 |

| Improvement Scheme | GPU Consumption | Parameter Quantity | GFLOPs | Training Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv7 | 2.51 G | 37,218,132 | 105.2 | 17 h |

| YOLOv7 + CA | 2.54 G | 37,969,872 | 119.7 | 21 h |

| YOLOv7 + DO-DConv | 2.52 G | 36,672,340 | 104.7 | 17 h |

| YOLOv7 + Slim-Neck | 2.48 G | 34,246,516 | 38.5 | 14 h |

| YOLOv7 + DO-DConv + Slim-Neck | 2.46 G | 33,113,460 | 38.2 | 13 h |

| Fall Type | Precision | Recall | mAP@0.5 | mAP@0.5:0.95 | F1 Score | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Fall | 86.00% | 84.50% | 85.00% | 53.20% | 85.20% | 63 |

| Backward Fall | 85.30% | 83.20% | 84.40% | 52.50% | 84.20% | 62 |

| Sideways Fall | 87.20% | 85.80% | 86.10% | 54.80% | 86.50% | 65 |

| Average | 86.17% | 84.50% | 85.20% | 53.50% | 85.30% | 63.3 |

| Lighting Condition | Fall Type | Precision | Recall | mAP@0.5 | mAP@0.5:0.95 | F1 Score | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 lux | Forward Fall | 81.20% | 79.60% | 80.50% | 50.30% | 80.40% | 58 |

| Backward Fall | 80.40% | 78.30% | 79.00% | 48.50% | 79.40% | 57 | |

| Sideways Fall | 82.10% | 80.40% | 81.20% | 51.10% | 81.20% | 59 | |

| 2 lux | Forward Fall | 79.60% | 77.10% | 78.30% | 47.10% | 78.40% | 56 |

| Backward Fall | 78.20% | 75.90% | 77.00% | 46.00% | 76.90% | 55 | |

| Sideways Fall | 80.50% | 78.00% | 79.30% | 48.20% | 79.30% | 57 |

| Action | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | False Alarm Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking | 96.70% | 95.30% | 96.00% | 3.00% |

| Running | 95.20% | 93.80% | 94.50% | 3.50% |

| Standing | 97.30% | 96.50% | 96.90% | 1.50% |

| Squatting | 97.60% | 96.70% | 97.10% | 1.80% |

| Improvement Scheme | Precision | Recall Rate | mAP@0.5 | mAP@0.5:0.95 | FPS | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv4-tiny | 76.47% | 83.11% | 81.90% | 51.06% | 149.6 | 0.79 |

| YOLOv5 | 82.63% | 80.18% | 84.90% | 53.56% | 130.2 | 0.81 |

| YOLOv8n | 87.93% | 80.21% | 89.75% | 57.59% | 113.7 | 0.84 |

| YOLOv7 | 81.59% | 83.81% | 85.69% | 54.31% | 67 | 0.83 |

| YOLOv7 + CA | 71.58% | 80.83% | 78.76% | 48.46% | 57 | 0.76 |

| YOLOv7 + DO-DConv | 86.04% | 82.84% | 86.76% | 55.63% | 67 | 0.84 |

| YOLOv7 + Slim-Neck | 85.57% | 85.57% | 86.51% | 54.25% | 113 | 0.84 |

| YOLOv7 + DO-DConv + Slim-Neck | 88.03% | 82.32% | 88.10% | 56.24% | 114 | 0.86 |

| Experimental Group Number | First Second | Second Second | Third Second | Fourth Second |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Participant Numbers and Their Confidence Scores | ||||

| 1 | A: 0.71 | A: 0.77 | A: 0.84 | A: 0.92 |

| 2 | A: 0.52 | A: 0.69 | A: 0.76 | A: 0.89 |

| 3 | A: 0.69 | A: 0.78 | A: 0.82 | A: 0.89 |

| 4 | A: 0.74 B: 0.74 | A: 0.63 B: 0.63 | A: 0 B: 0 | A: 0.88 B: 0.88 |

| 5 | A: 0.81 B: 0.72 | A: 0 B: 0.69 | A: 0.69 B: 0.6 | A: 0.91 B: 0.91 |

| 6 | A: 0.77 B: 0.75 | A: 0.6 B: 0.6 | A: 0 B: 0.61 | A: 0.84 B: 0.84 |

| 7 | A: 0.78 B: 0.64 | A: 0.71 B: 0.58 | A: 0.64 B: 0.92 | A: 0.91 B: 0.71 |

| 8 | A: 0.86 B: 0.86 | A: 0.78 B: 0.78 | A: 0 B: 0.65 | A: 0.81 B: 0.82 |

| 9 | A: 0.7 B: 0.64 | A: 0.54 B: 0 | A: 0.61 B: 0.66 | A: 0.71 B: 0.71 |

| 10 | A: 0.78 B: 0.77 C: 0 | A: 0.73 B: 0.63 C: 0 | A: 0.47 B: 0.47 C: 0.27 | A: 0.61 B: 0.64 C: 0.37 |

| Experimental Group Number | First Second | Second Second | Third Second | Fourth Second |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Participant Numbers and Their Confidence Scores | ||||

| 11 | A: 0.62 B: 0 | A: 0.63 B: 0.51 | A: 0 B: 0 | A: 0.79 B: 0.69 |

| 12 | A: 0 B: 0.56 | A: 0 B: 0 | A: 0.5 B: 0.7 | A: 0.75 B: 0.63 |

| 13 | A: 0.75 B: 0.75 | A: 0.81 B: 0.81 | A: 0.72 B: 0.8 | A: 0.71 B: 0.78 |

| 14 | A: 0.65 B: 0.74 | A: 0.66 B: 0.57 | A: 0.86 B: 0.68 | A: 0.76 B: 0.61 |

| 15 | A: 0.69 B: 0.51 | A: 0.56 B: 0.58 | A: 0.7 B: 0.65 | A: 0.81 B: 0.75 |

| 16 | A: 0.71 B: 0.58 | A: 0.73 B: 0.63 | A: 0.82 B: 0.69 | A: 0.87 B: 0.87 |

| 17 | A: 0.56 B: 0.47 | A: 063 B: 073 | A: 0.77 B: 0.7 | A: 0.82 B: 075 |

| 18 | A: 0.54 B: 0.4 | A: 0.73 B: 0.63 | A: 0.3 B: 0 | A: 0.75 B: 0.51 |

| 19 | A: 0.61 B: 0.52 | A: 0.28 B: 0.49 | A: 0.52 B: 0.42 | A: 0.71 B: 0.69 |

| 20 | A: 0.47 B: 0.45 | A: 0.4 B: 0.4 | A: 0.6 B: 0.6 | A: 0.74 B: 0.74 |

| 21 | A: 0.62 B: 0.54 | A: 0.71 B: 0.58 | A: 0.44 B: 0.46 | A: 0.7 B: 0.63 |

| 22 | A: 0.51 B: 0 | A: 0.6 B: 0.5 | A: 0.56 B: 0.52 | A: 0.7 B: 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Yan, L. Enhancements and On-Site Experimental Study on Fall Detection Algorithm for Students in Campus Staircase. Sensors 2025, 25, 7394. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237394

Lu Y, Cui Y, Yan L. Enhancements and On-Site Experimental Study on Fall Detection Algorithm for Students in Campus Staircase. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7394. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237394

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Ying, Yuze Cui, and Liang Yan. 2025. "Enhancements and On-Site Experimental Study on Fall Detection Algorithm for Students in Campus Staircase" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7394. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237394

APA StyleLu, Y., Cui, Y., & Yan, L. (2025). Enhancements and On-Site Experimental Study on Fall Detection Algorithm for Students in Campus Staircase. Sensors, 25(23), 7394. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237394