Near-Field Target Detection with Range–Angle-Coupled Matching Based on Distributed MIMO Radar

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. The Technology of Designing Transmitting Waveform

2.2. Far-Field and Near-Field Division Technology

2.3. Spatial Coherent Accumulation Technique

3. Problem Description

3.1. Signal Model for Distributed MIMO Radar

3.1.1. Near-Field Targets

3.1.2. Targets Position Coordinates

3.1.3. TTDs Within a Single Pulse

3.1.4. TTDs Within One CPI Duration

3.2. Multi-Dimensional Signal Model

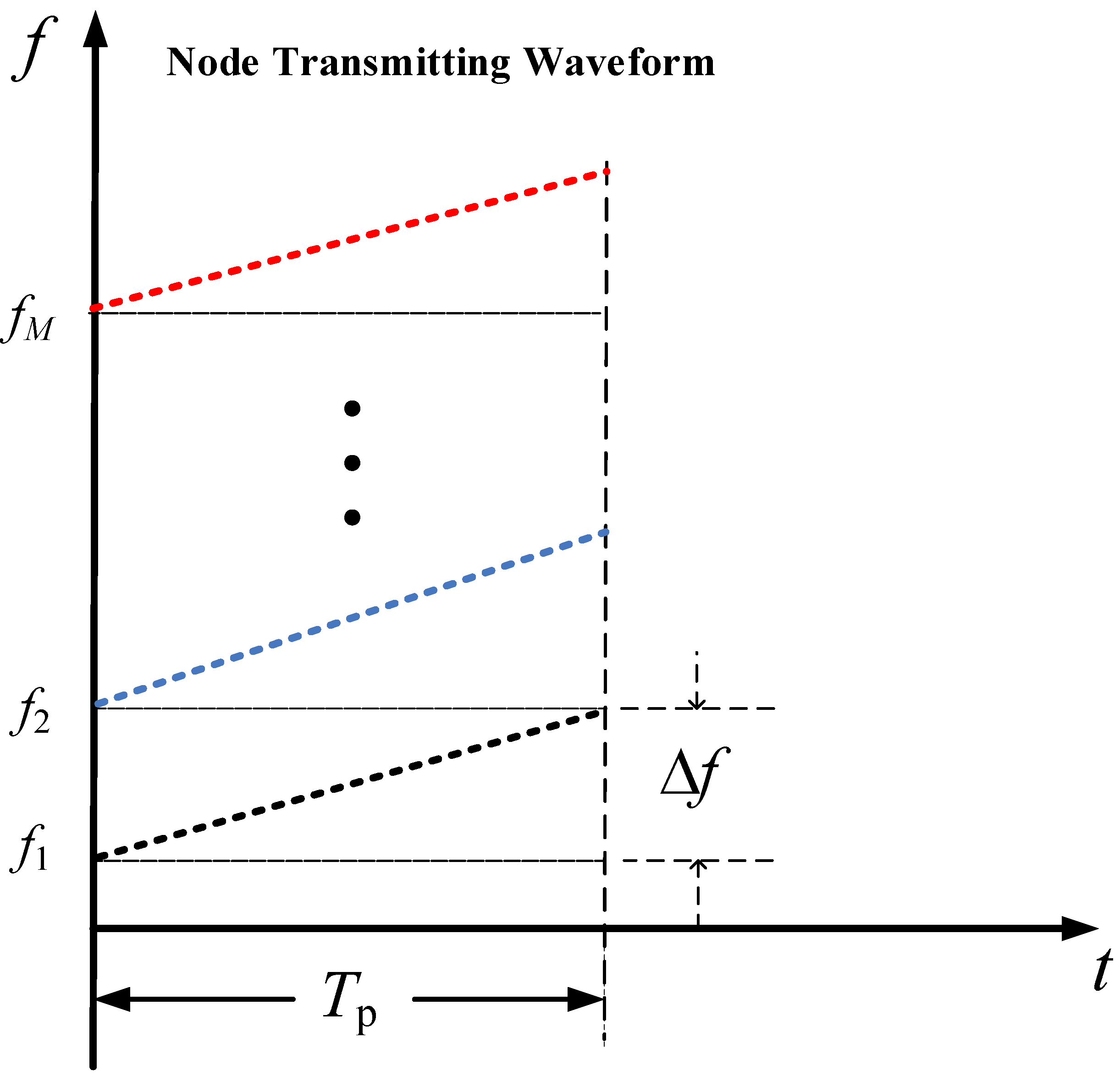

3.2.1. FD-LFM Transmitting Signal Model

3.2.2. Receiving Echo Signal Model

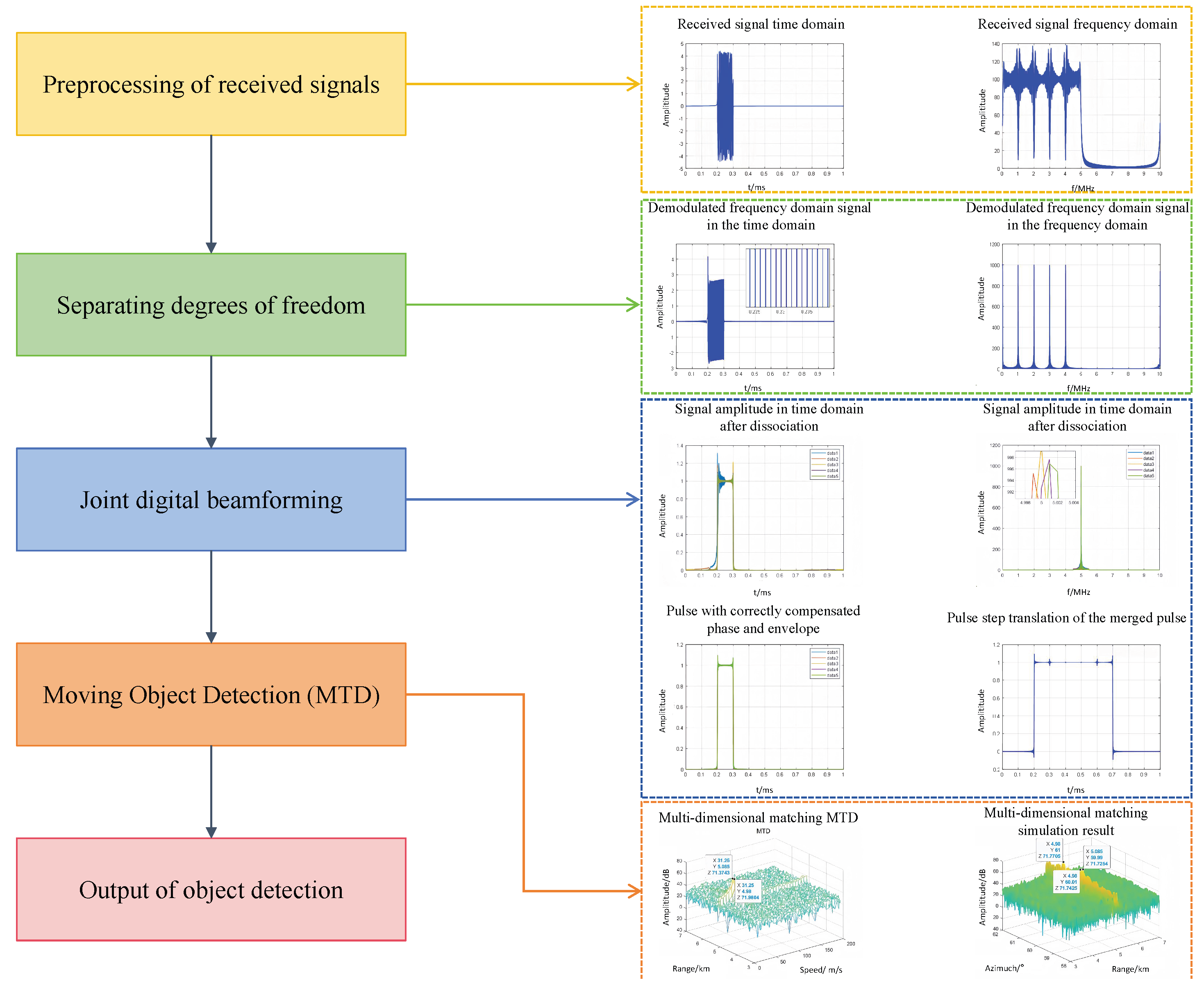

4. Scheme Design of Multi-Dimensional Matching Processing for Distributed MIMO Radar

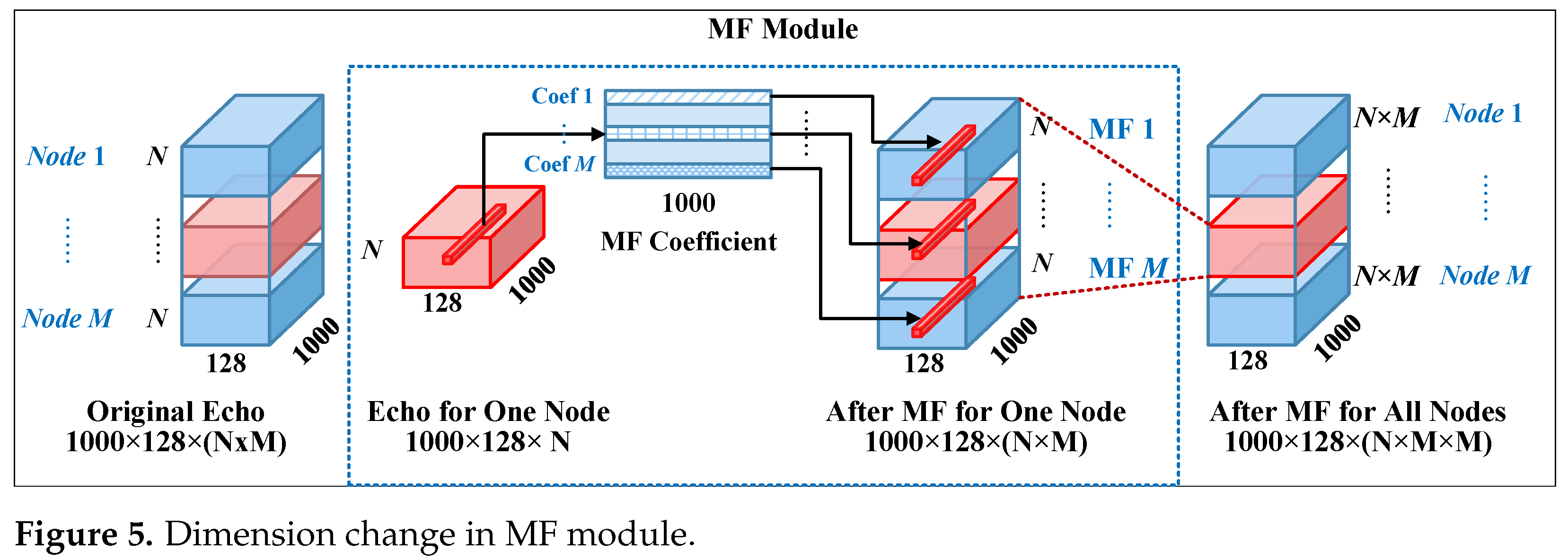

4.1. Transmitted Signal Separation at the Receiving End

4.1.1. Frequency–Domain Representation of the Received Baseband Echo Signal

4.1.2. Frequency–Domain Representation of the Separated Transmitter Signals

4.1.3. Frequency-Domain Representation of the Reference Signal

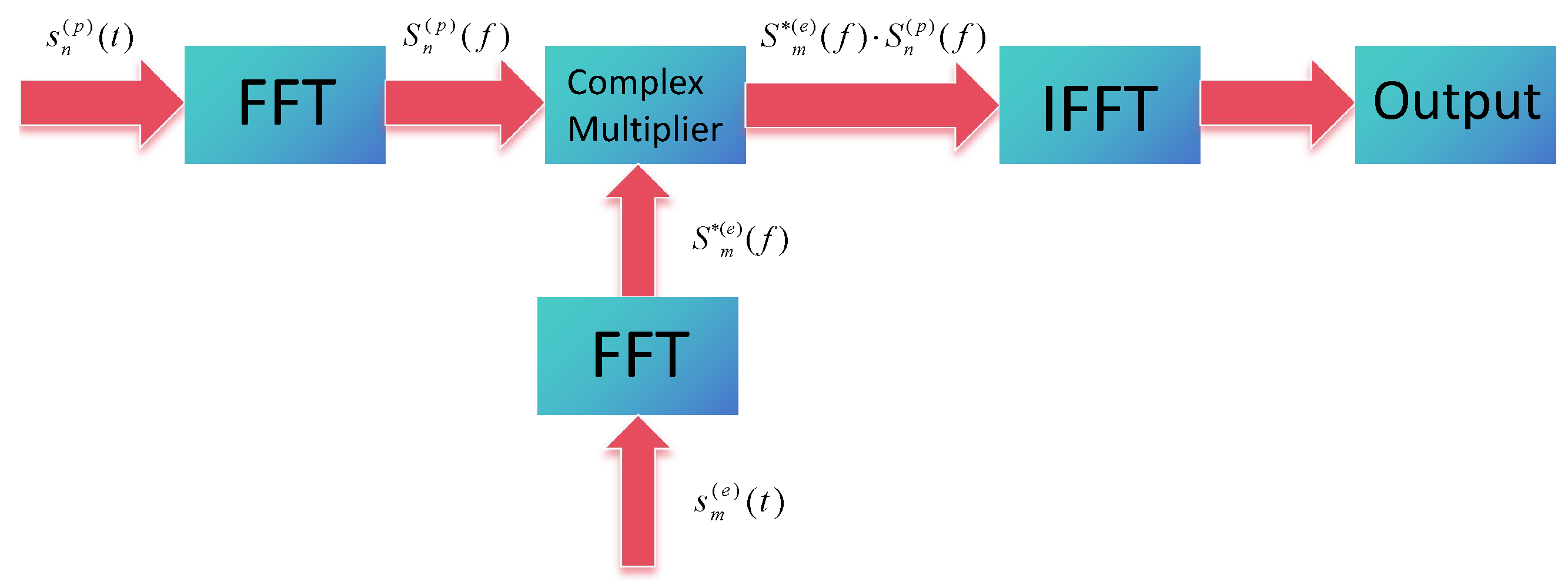

4.1.4. Frequency–Domain Matched Filter Processing

4.2. Design of the Compensation Function

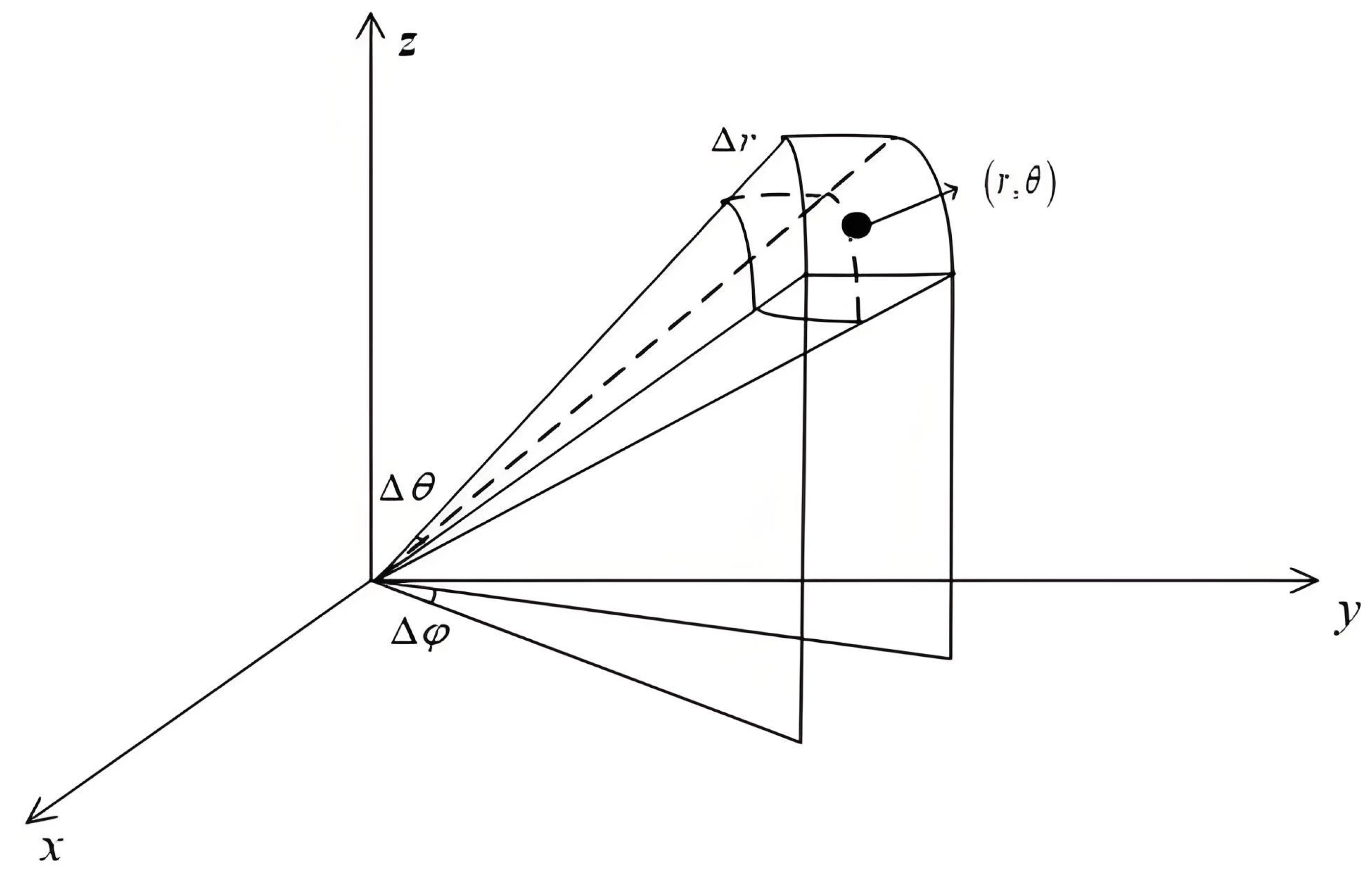

4.2.1. 3D Grid Division of Airspace Detection

4.2.2. Accurate Compensation Based on the 3D Grid Resolution Units

4.3. Joint Digital Beamforming

4.4. Moving Target Detection

5. Numerical Simulations and Experimental Results

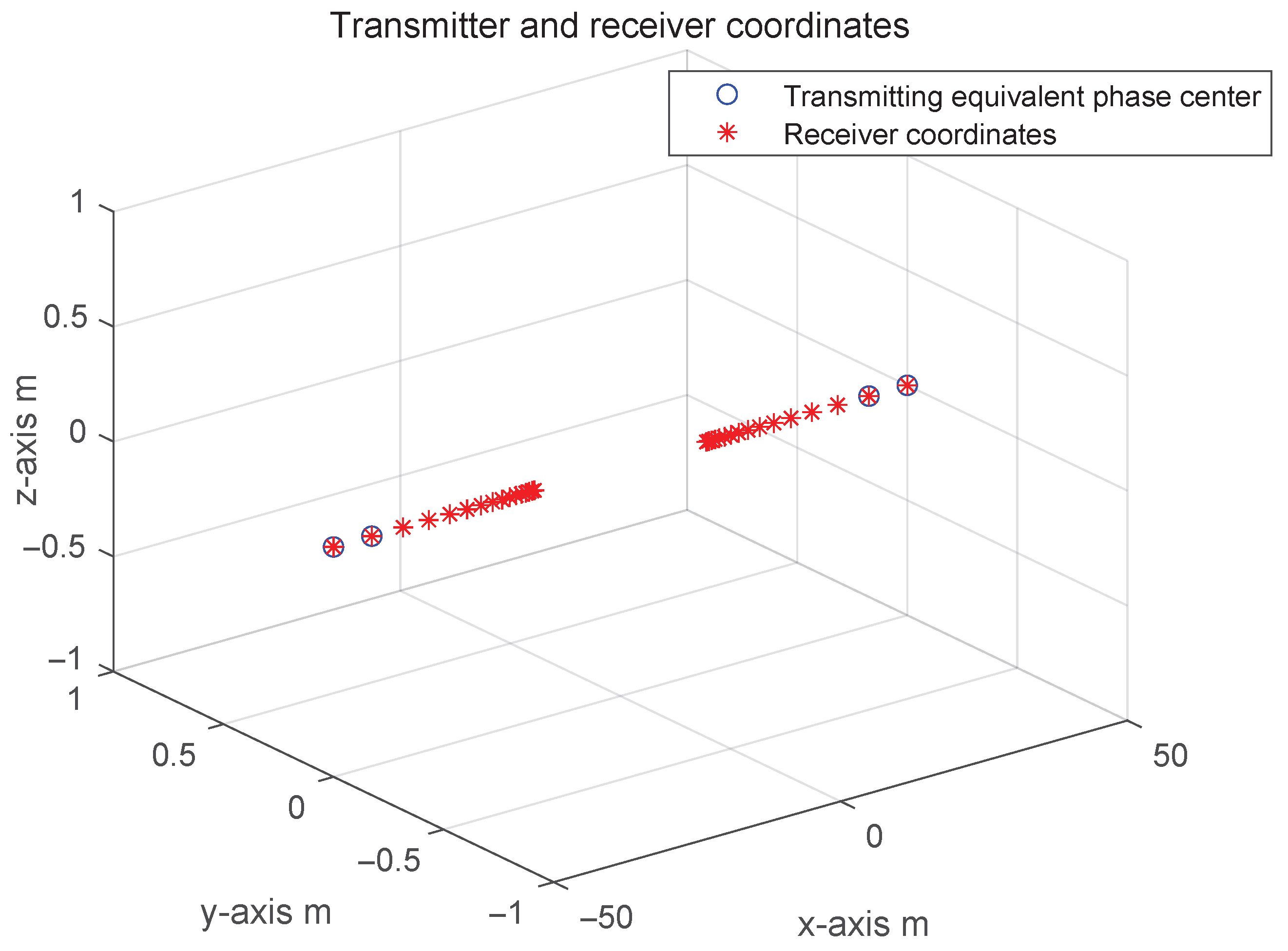

5.1. Numerical Simulation of Near-Field Multi-Dimensional Matching Processing Scheme

5.1.1. Simulation Setting

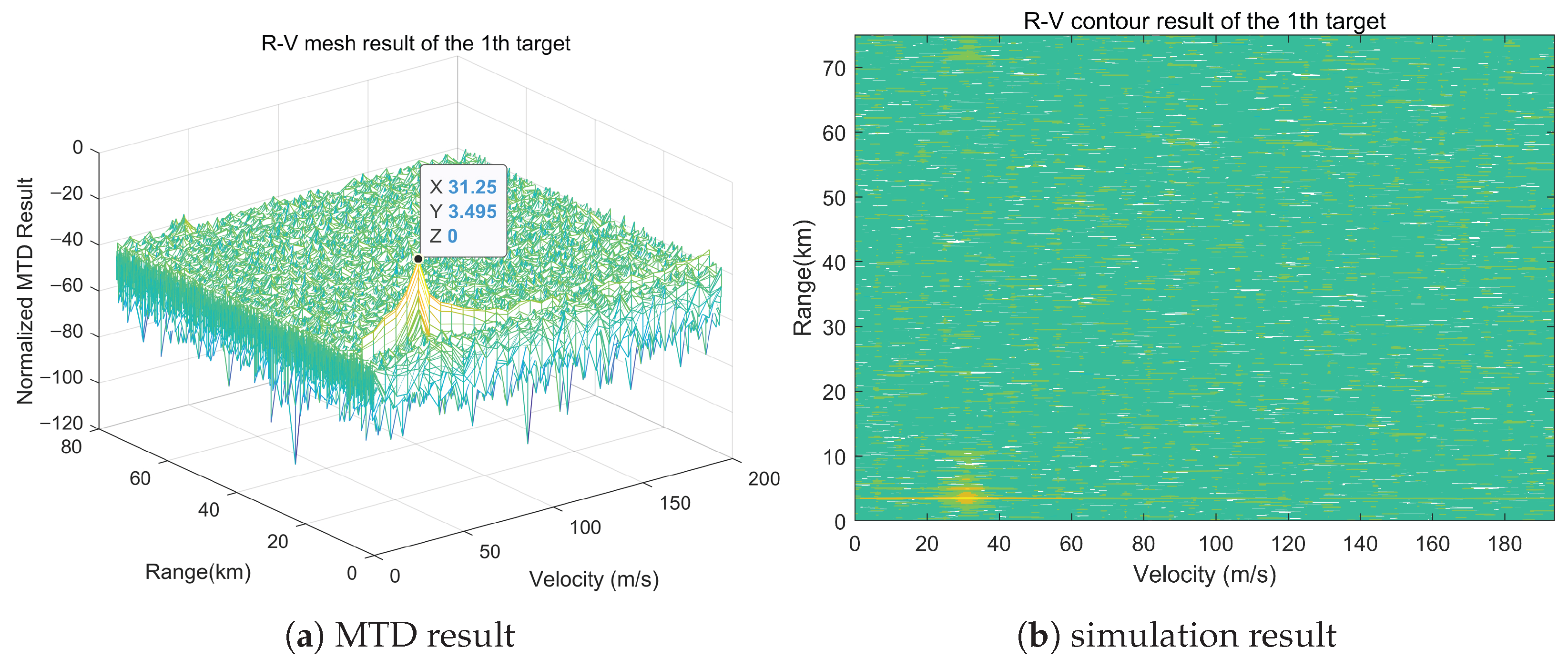

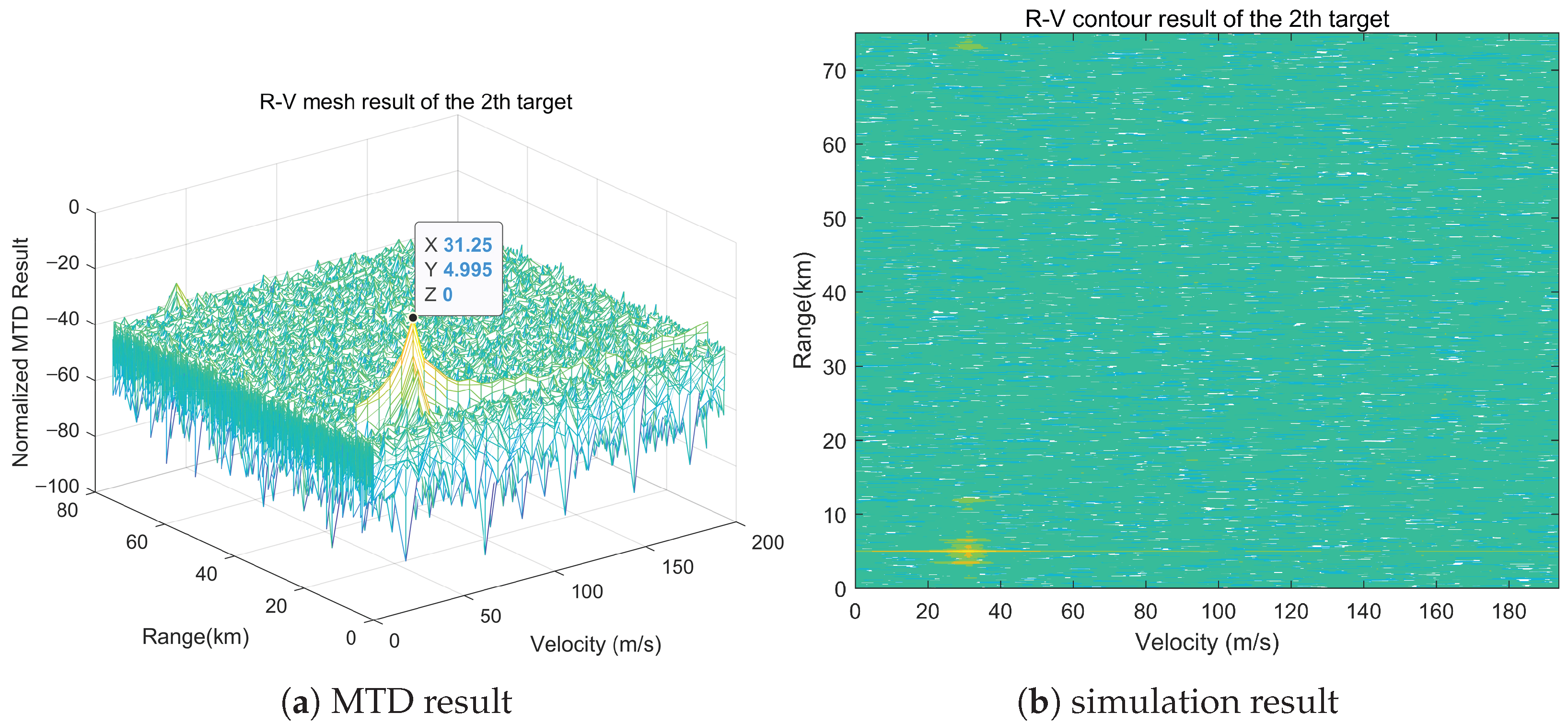

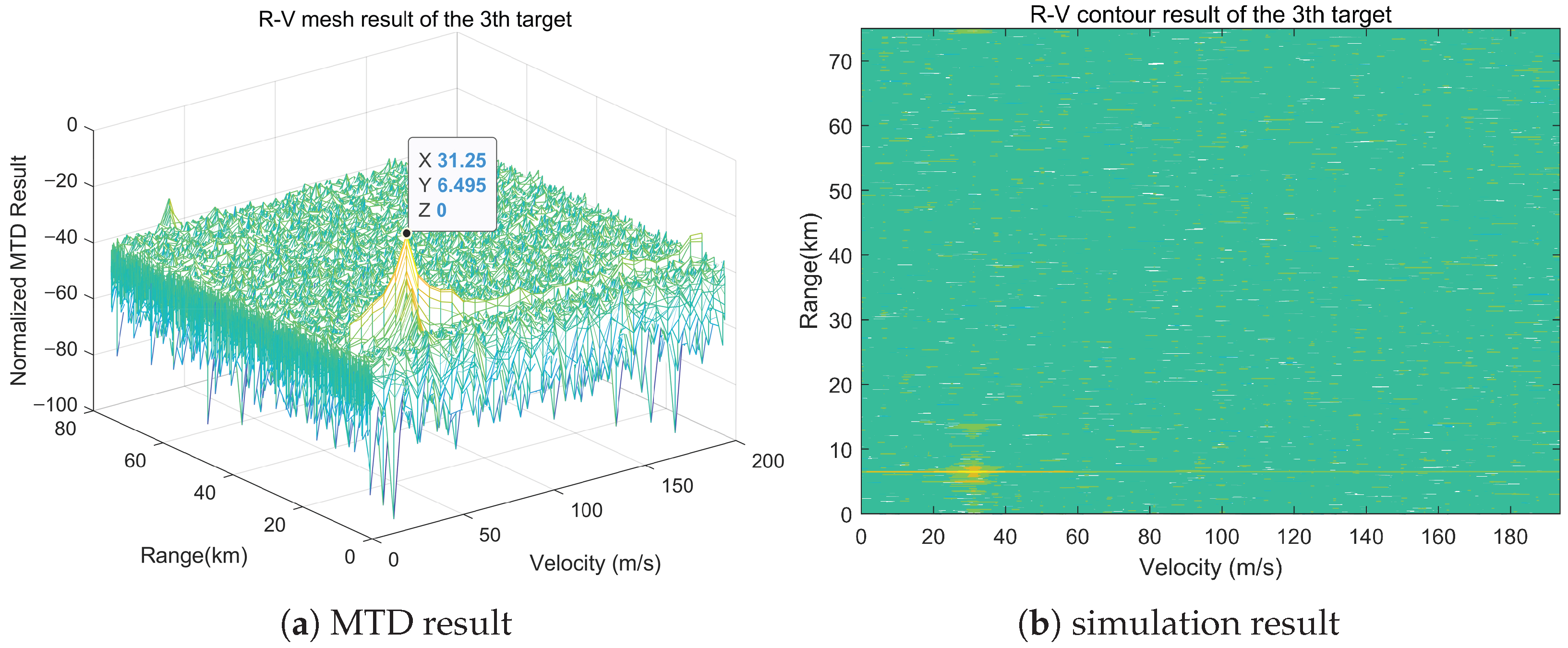

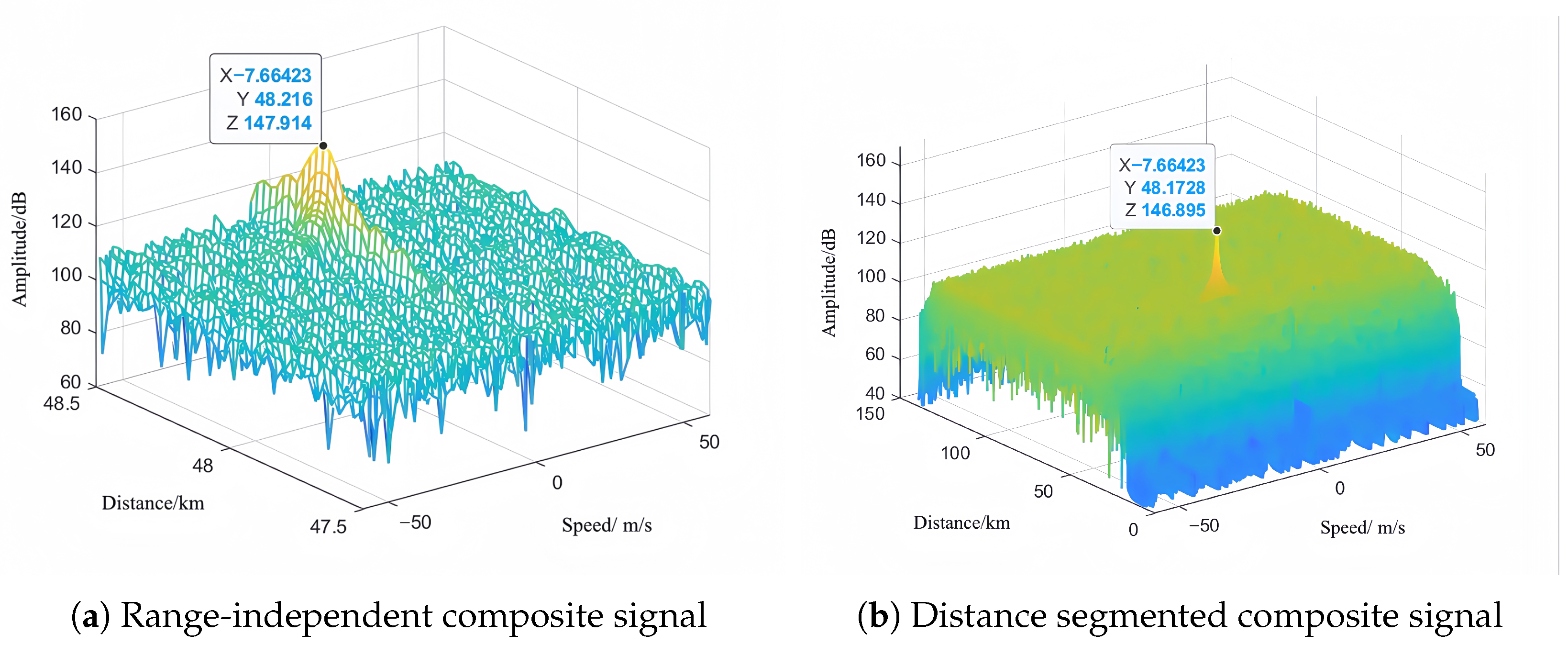

5.1.2. Simulation Analysis

5.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

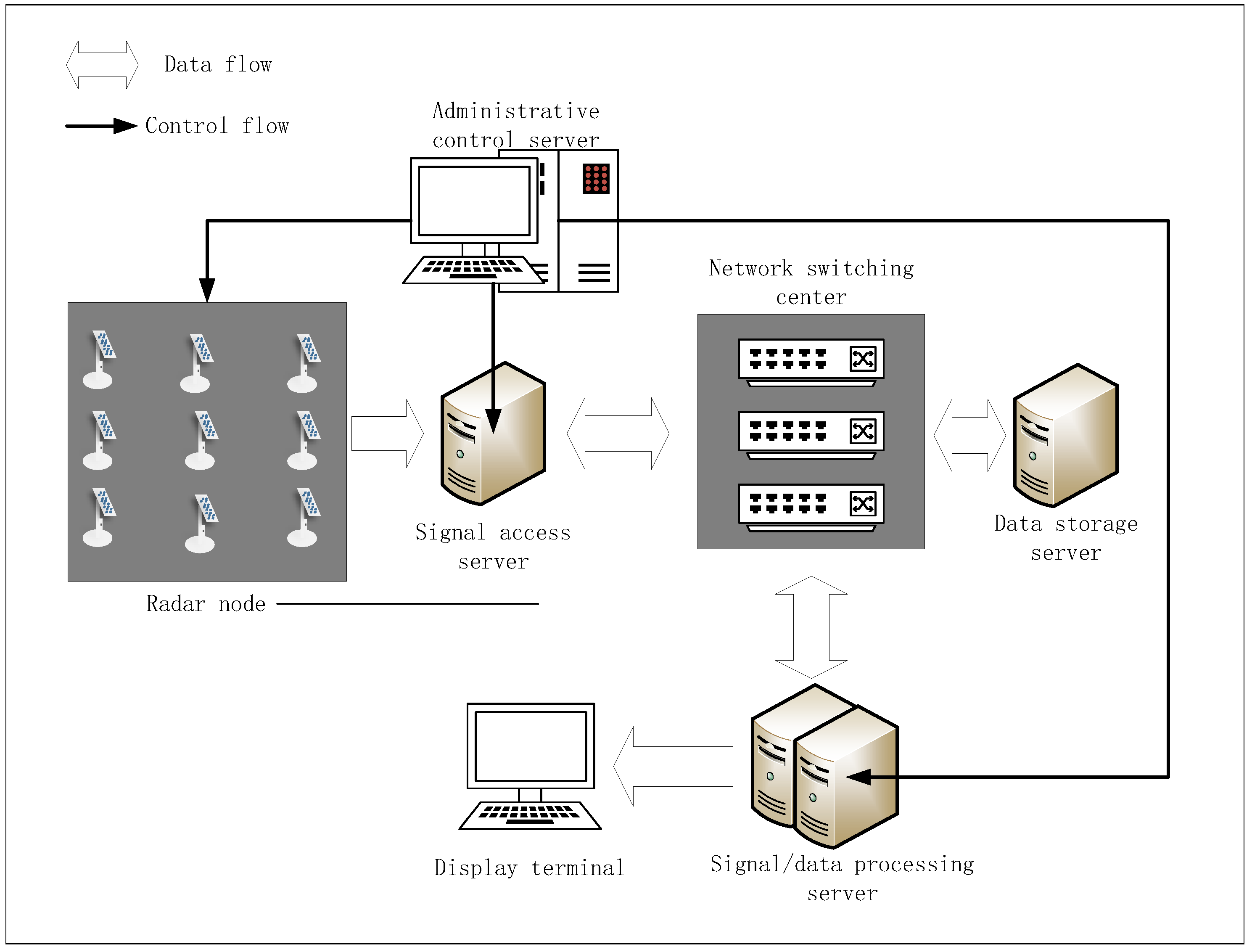

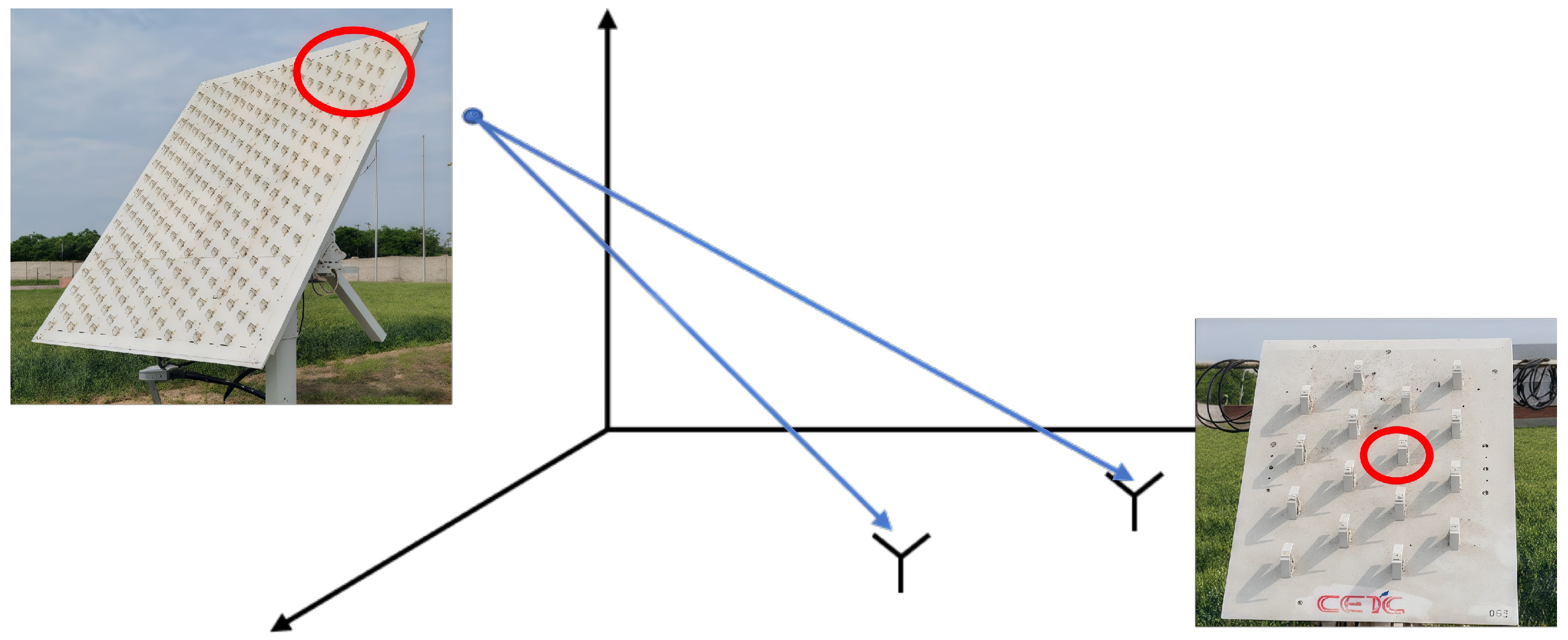

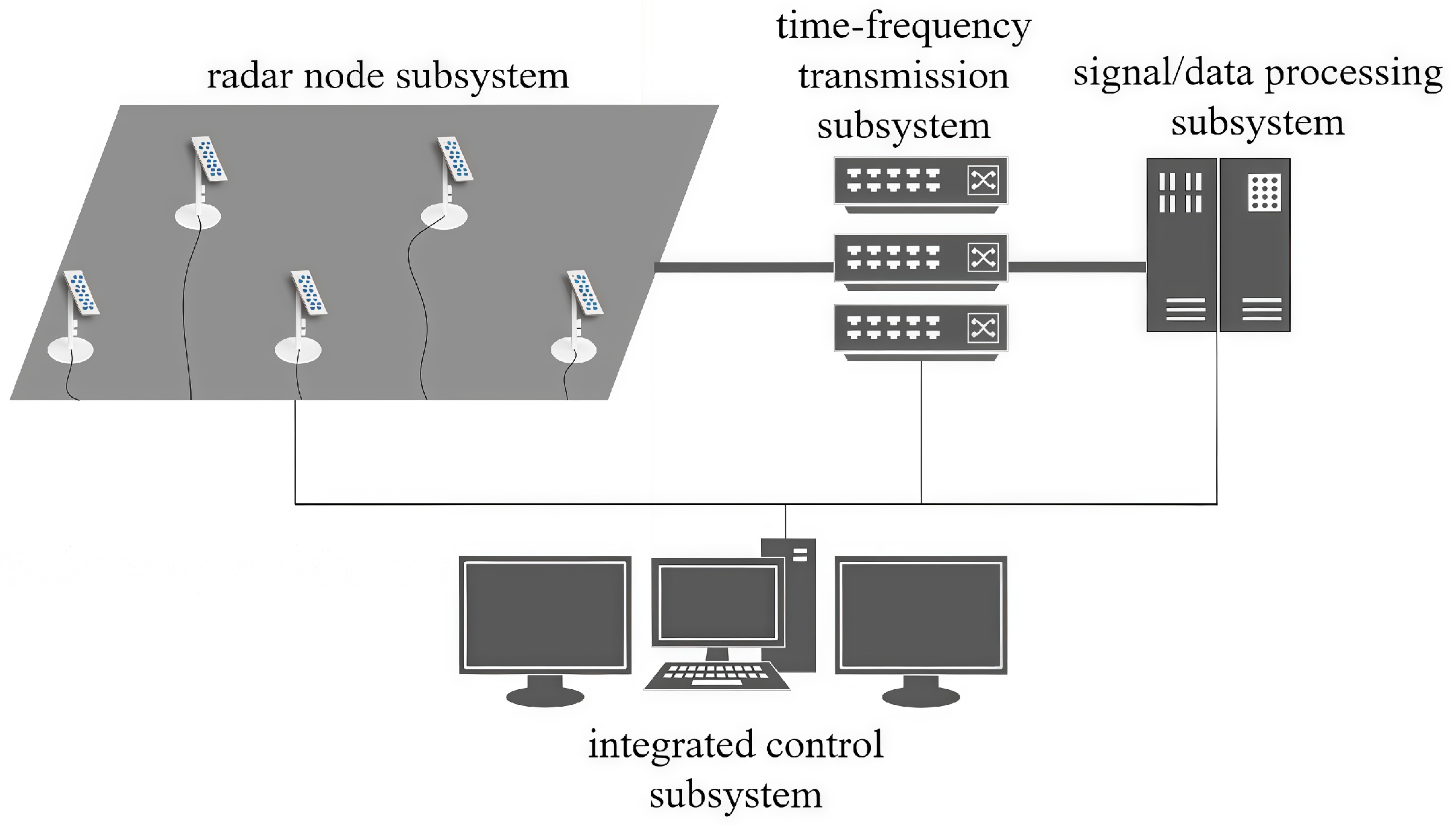

5.2.1. Basic Components of Distributed MIMO Radar System

5.2.2. Heterogeneous Platform for Signal/Data Processing

Experimentation Plan and Procedure

- Use the task planning client software to check the expected node to be used in the cluster node settings, fill in the GPU server to which the node data flows in the attribute settings, and then select the task planning to assign and select the corresponding pre-set task template to the node. Dispatch tasks, and set the task mode to real-time task after the task is successfully assigned.

- After accomplishing the echo transmission preparation, initiate the corresponding signal processing task on the deployed server and start receiving data for real-time processing.

- Observe the civil aircraft on the ADS-B software, accessed on 10 January 2022 wait for the aircraft to enter into the detection range of the radar, and observe the display and control software.

5.2.3. Experimentation Evaluation Metrics

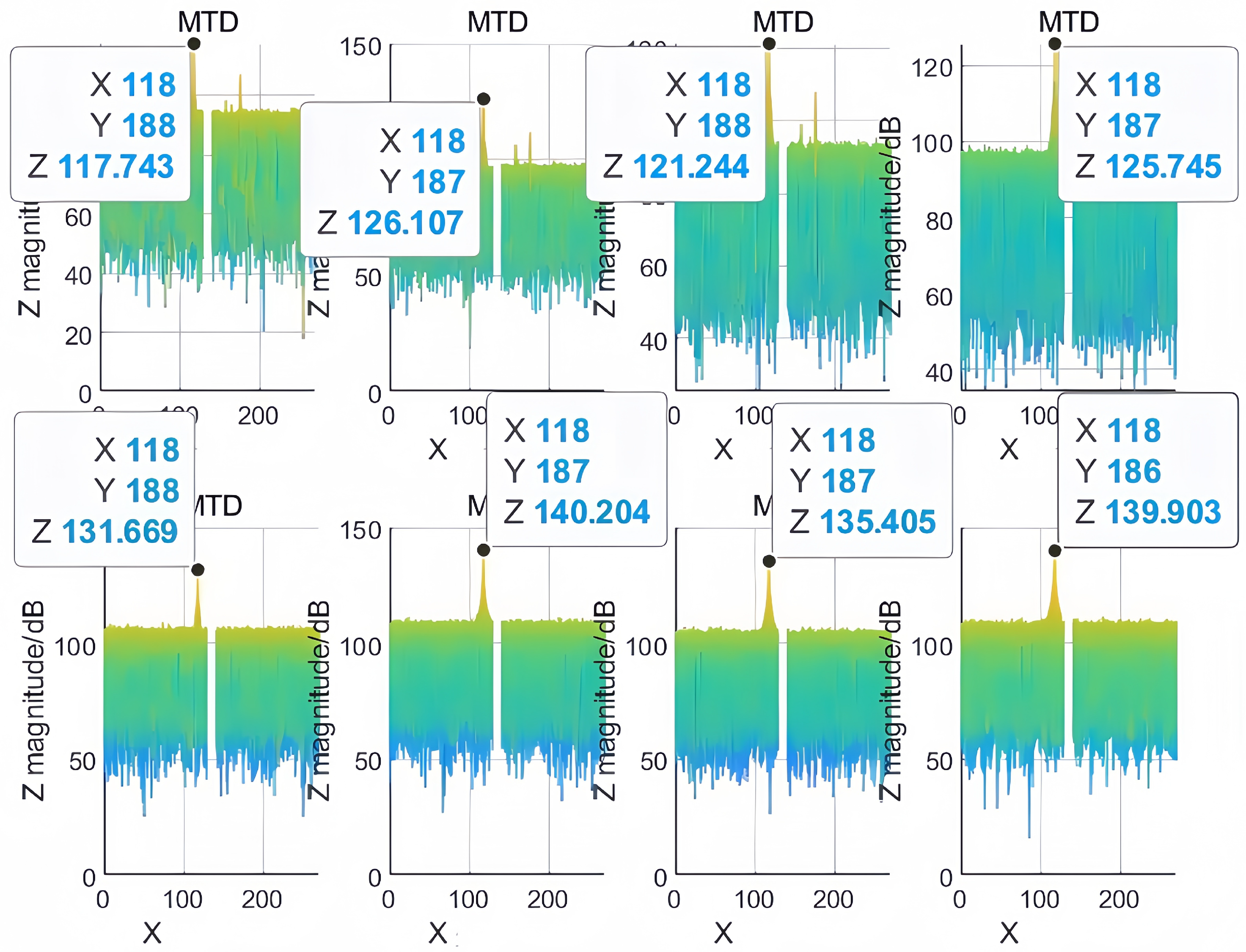

5.2.4. Experimentation Results of Real-Time Processing Program

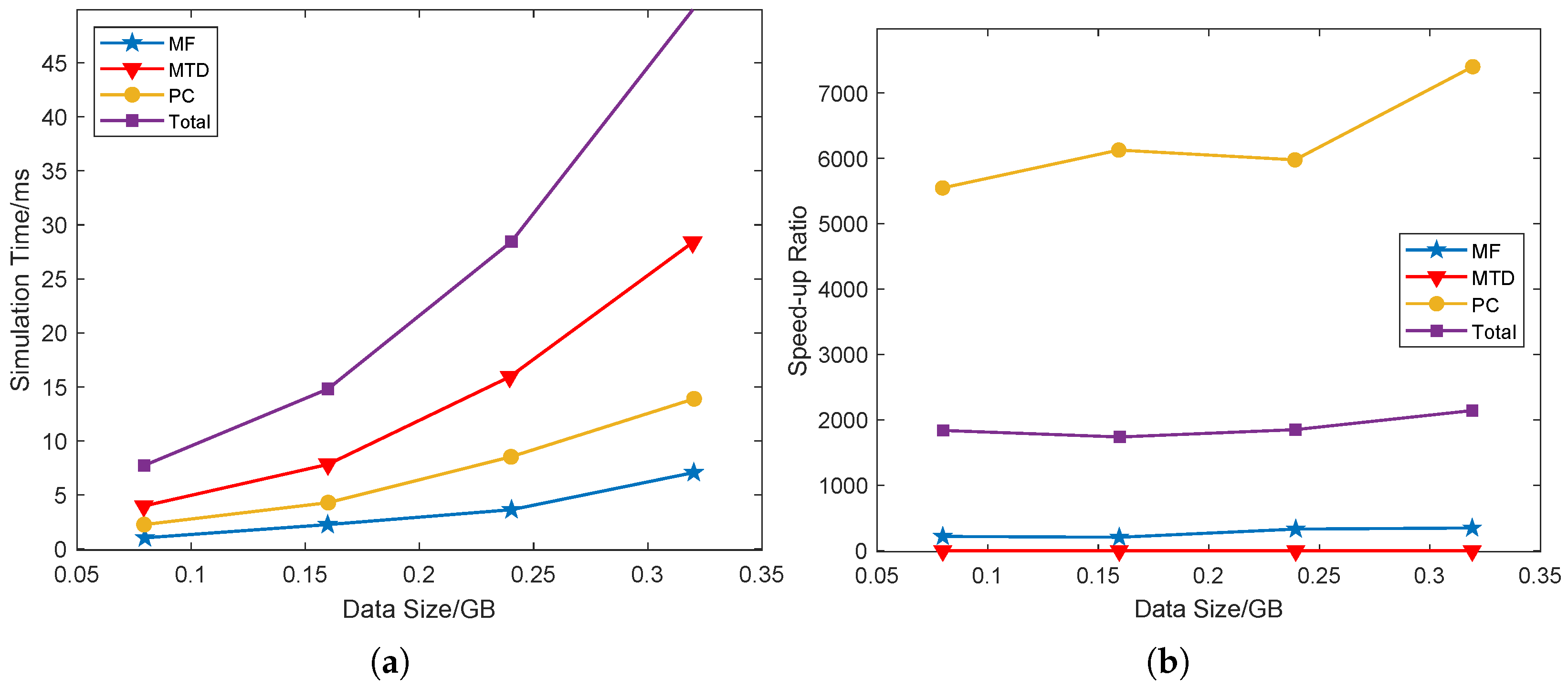

Performance Analysis of GPU Acceleration

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Frequency–Domain Representation of the Transmitting Signal at the Transmitting End

References

- Hoft, D.J. Solid state transmit/receive module for the PAVE PAWS (AN/FPS-115) phased array radar. In Proceedings of the 1978 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 27–29 June 1978; pp. 239–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, L. The status quo and development trend of Russian tactic phased array radar. Fire Control Command. Control 2007, 32, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y. Review of the evolution of phased-array radar. SHS Web Conf. 2022, 144, 02008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Zhang, J.; Shaikh, Z.S.; Wang, J.; Ren, W. Four-dimensional (4D) millimeter wave-based sensing and its potential applications in digital construction: A review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Shi, J.; Su, Y.; Deng, M. A survey of collocated MIMO radar. J. Radars 2022, 11, 805–829. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, H.T.; Alves, D.I.; Machado, R.; Passaro, A. A Methodology for Assessing Data Augmentation Effectiveness for Target Classification in SAR Images. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf24), Denver, CO, USA, 6–10 May 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.C.; Lan, P.; Deng, Y.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xing, M.; Zhang, Y. Multichannel Back Projection (MC-BP) Algorithm and Its Accelerated Form for HRWS SAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5222116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Jiao, Z.; Shen, G.; Xing, M.; Gashinova, M. A Multiangle MIMO-SAR Fusion Imaging Method Based on Improved Range Migration Algorithm and Improved Geographic Information Scale Invariant Feature Transform Algorithm. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 13938–13949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Development and key technologies of bistatic/multistatic radars. Radar ECM 2013, 33, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Montebugnoli, S.; Pupillo, G.; Salerno, E. A potential integrated multiwavelength radar system at the Medicina radiotelescopes. In Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Space Debris, Darmstadt, Germany, 30 March–2 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wen, F.; He, J.; Truong, T.K. Coarray Tensor Train Decomposition for Bistatic MIMO Radar with Uniform Planar Array. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2025, 73, 5310–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Shi, J.; Wen, F.; Zheng, Z. Higher-order tensor decomposition for 2D-DOD and 2D-DOA estimation in bistatic MIMO radar. Signal Process. 2025, 238, 110196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, F.; Shi, J.; Gui, G.; Yuen, C.; Sari, H.; Adachi, F.; Lin, Y. Joint DOD and DOA estimation for NLOS target using IRS-aided bistatic MIMO radar. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 15798–15802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, S.; Cuomo, K.; McHarg, J.; Robey, F.; Weikle, D. Distributed coherent aperture measurements for next generation BMD radar. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Sensor Array and Multichannel Signal Processing Workshop, Waltham, MA, USA, 12–14 July 2006; pp. 390–393. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Cao, Z.; Lu, Y. Basic research and principle verification of distributed array coherent synthesis radar. In Proceedings of the 12th National Radar Conference, Wuhan, China, 7–11 May 2012; pp. 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, K.; Yin, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, W. Range and DOA estimation of near-field sources via the fourth-order statistics. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Taipei, Taiwan, 24–27 May 2009; pp. 2465–2468. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Li, R.; Han, C.; Liu, X.; Xue, L.; Tao, M. How to differentiate between near field and far field: Revisiting the Rayleigh distance. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2025, 63, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Lu, W.; Xiong, H.; Ding, H.; He, Q.; Zhao, D.; Wan, J.; Xing, F.; You, Z. Onboard cooperative relative positioning system for Micro-UAV swarm based on UWB/Vision/INS fusion through distributed graph optimization. Measurement 2024, 234, 114897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhoglu, M.A.; Alp, Y.K.; Akyon, F.C. Deep learning for radar signal in electronic warfare systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf20), Virtual, 21–25 September 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.J. Stealth Communication Via Smart Ultra-Wide-Band Signal in 5G, Radar, Electronic Warfare, etc. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation and North American Radio Science Meeting, Virtual, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 1825–1826. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Shi, J.; Fei, T.; Zong, B. Joint detection threshold optimization and illumination time allocation strategy for cognitive tracking in a networked radar system. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2022, 70, 5833–5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, H.; Farina, A. Multistatic and networked radar: Principles and practice. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf21), Virtual, 8–14 May 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Haugstvedt, H.; Jacobsen, J.O. Taking fourth-generation warfare to the skies? An empirical exploration of non-state actors’ use of weaponized unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs—‘drones’). Perspect. Terror. 2020, 14, 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zeng, C.; Wang, H.; Liao, G. Networked Radar System: A More Advanced Radar Detection Platform. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Frontiers of Electronics, Information and Computation Technologies (ICFEICT), Yangzhou, China, 26–29 May 2023; pp. 506–512. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Qi, Z.; Ye, Z.; Wan, Y.; Li, L. Research on cooperative detection technology of networked radar based on data fusion. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd China International SAR Symposium (CISS), Shanghai, China, 3–5 November 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sakhnini, A.; De Bast, S.; Guenach, M.; Bourdoux, A.; Sahli, H.; Pollin, S. Near-field coherent radar sensing using a massive MIMO communication testbed. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 6256–6270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miran, E.A.; Oktem, F.S.; Koc, S. Sparse reconstruction for near-field MIMO radar imaging using fast multipole method. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 151578–151589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuso, V.J.; Schneible, R.A.; Zhang, Y.; Wicks, M.C. Distributed apertures for robustness in radar and communications (DARC). In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarCon), Arlington, VA, USA, 10–15 May 2015; pp. 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.W.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Lu, X.; Dong, C. Radar network time scheduling for multi-target ISAR task with game theory and multiagent reinforcement learning. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 21, 4462–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammartino, P.F.; Baker, C.J.; Griffiths, H.D. Frequency diverse MIMO techniques for radar. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2013, 49, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guermandi, D.; Shi, Q.; Dewilde, A.; Derudder, V.; Ahmad, U.; Spagnolo, A.; Ocket, I.; Bourdoux, A.; Wambacq, P.; Craninckx, J.; et al. A 79-GHz 2×2 MIMO PMCW radar SoC in 28-nm CMOS. IEEE J.-Solid-State Circuits 2017, 52, 2613–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X. A multi-carrier frequency random-transmission chirp sequence for TDM MIMO automotive radar. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 3672–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.Q.; Feger, R.; Bechter, J.; Pichler-Scheder, M.; Hahn, M.H.; Stelzer, A. Fast-chirp FDMA MIMO radar system using range-division multiple-access and Doppler-division multiple-access. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2020, 69, 1136–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Wei, G.; Ren, J.; Wang, X.; Fei, Z. Enhancing the orthogonality of polyphase signal with multi-pulse joint processing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 9656–9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Yoon, Y.-J.; Jung, J.; Kim, S.-C. Novel multiplexing scheme for resolving the velocity ambiguity problem in MIMO FMCW radar using MPSK code. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 75234–75244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Su, J.; He, C.; Tao, M.; Fan, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, S. Phase-coded passive jamming suppression via squaring nonlinear transform and fractional Fourier transform. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 61, 1942–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Wei, G.; Shao, J.; Wang, X.; Fei, Z. Design of orthogonal polyphase code set based on multi-pulse joint processing. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 8901–8913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigsnering, M.; Zoubir, A.M. Fast wideband near-field imaging using the non-equispaced FFT with application to through-wall radar. In Proceedings of the 2011 19th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Barcelona, Spain, 29 August–2 September 2011; pp. 1708–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.R.; Godara, L.C.; Hossain, M.S. Robust near field broadband beamforming in the presence of steering vector mismatches. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Wireless and Microwave Technology Conference (WAMICON), Cocoa Beach, FL, USA, 15–17 April 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.-p.; Jiao, Y.-m.; Zhang, C.-z. Robust near-field beamforming with worst case performance based on convex optimization. In Proceedings of the 5th Global Symposium on Millimeter-Waves (GSMM), Harbin, China, 27–30 May 2012; pp. 608–611. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; He, P.; Cui, A.; Wang, H.; Zhou, H.; Xu, Z. DOA estimation ambiguity resolution method for near field distributed array. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th Int. Conf. Intell. Comput. Signal Process (ICSP), Xi’an, China, 9–11 April 2021; pp. 870–875. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Gao, X.; Liu, W.; Chen, H.; Wang, G.; Qin, Y. Localization of mixed far-field and near-field incoherently distributed sources using two-stage RARE estimator. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 1482–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, A.; Ying, M.; Kanhere, O.; Rappaport, T.S.; Chafii, M. ISAC Imaging by Channel State Information using Ray Tracing for Next Generation 6G. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Electromagn. Antennas Propag. 2025, 1, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, K.M.; Coutts, S.D.; McHarg, J.C.; Robey, F.C.; Pulsone, N.B. Wideband Aperture Coherence Processing for Next Generation Radar; Technical Report; MIT Lincoln Laboratory: Lexington, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brookner, E. Phased-array and radar breakthroughs. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Radar Conference, Waltham, MA, USA, 17–20 April 2007; pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Brookner, E. Phased-array and radar astounding breakthroughs—An update. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Radar Conference, Rome, Italy, 26–30 May 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, M.; Dai, L. Near-Field Wideband Beamforming for Extremely Large Antenna Arrays. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 13110–13124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, R.E.; Metcalf, J.G.; Ruyle, J.E.; McDaniel, J.W. Wideband measurement techniques for extracting accurate RCS of single and distributed targets. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 6001512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizitiu, I.; Anton, L.; Popescu, F.; Iubu, G. The synthesis of some NLFM laws using the stationary phase principle. In Proceedings of the 2012 10th International Symposium on Electronics and Telecommunications, Timisoara, Romania, 15–16 November 2012; pp. 377–380. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Deng, Y.K.; Loffeld, O.; Nies, H.; Walterscheid, I.; Espeter, T.; Klare, J.; Ender, J.H.G. Processing the azimuth-variant bistatic SAR data by using monostatic imaging algorithms based on two-dimensional principle of stationary phase. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 3504–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zeng, C.; Lan, L.; Liao, G.; Zhu, S.; Chen, B. Synthesis of Large Sparse Sensor Arrays Utilizing RIEA (Relaxed-Intensified Exploration Algorithm) for Optimal UAVs Beamforming. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 8509815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Liang, J.; Fan, X.; So, H.C. A unified sparse array design framework for beampattern synthesis. Signal Process. 2021, 182, 107930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, A.; Gautam, S.; Aggarwal, R. Performance Improvement in Target Detection Using Various Techniques in Complex Matched Filter in Radar Communication. In Micro-Electronics and Telecommunication Engineering: Proceedings of 4th ICMETE 2020, Ghaziabad, India, 26–27 September 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Dai, W.; Zhang, G.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Jia, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Bai, Z.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Frequency-domain deconvolution adaptive noise cancellation DOA estimation algorithm based on matched filtering. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 9505210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, T.; He, Y.; Dan, Y.; Yin, J.; Ma, B.; Yang, J. GPU-Oriented Designs of Constant False Alarm Rate Detectors for Fast Target Detection in Radar Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5231214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Radar Parameters | Numerical Value | Unit of Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Transmit nodes | 4 | Unit |

| Receive nodes | 32 | Unit |

| Transmit carrier frequency | 1.5 | GHz |

| Pulse Repetition Period | 500 | us |

| Pulse width | 50 | us |

| Signal bandwidth | 1 | MHz |

| Stepped frequency | 1 | MHz |

| Sampling frequency | 10 | MHz |

| CPI pulse number | 32 | Unit |

| Target Parameters | Target 1 | Target 2 | Target 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 3.5 km | 5.0 km | 6.5 km |

| Azimuth | 60° | 60° | 61° |

| Speed | 31 m/s | 30 m/s | 30 m/s |

| SNR | −20 dB | −20 dB | −20 dB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, Z.; Liao, G.; Tao, H. Near-Field Target Detection with Range–Angle-Coupled Matching Based on Distributed MIMO Radar. Sensors 2025, 25, 7003. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25227003

Cheng Q, Zhang Y, Zeng C, Zhou Z, Liao G, Tao H. Near-Field Target Detection with Range–Angle-Coupled Matching Based on Distributed MIMO Radar. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):7003. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25227003

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Quanrun, Yuhong Zhang, Cao Zeng, Zhigang Zhou, Guisheng Liao, and Haihong Tao. 2025. "Near-Field Target Detection with Range–Angle-Coupled Matching Based on Distributed MIMO Radar" Sensors 25, no. 22: 7003. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25227003

APA StyleCheng, Q., Zhang, Y., Zeng, C., Zhou, Z., Liao, G., & Tao, H. (2025). Near-Field Target Detection with Range–Angle-Coupled Matching Based on Distributed MIMO Radar. Sensors, 25(22), 7003. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25227003