Abstract

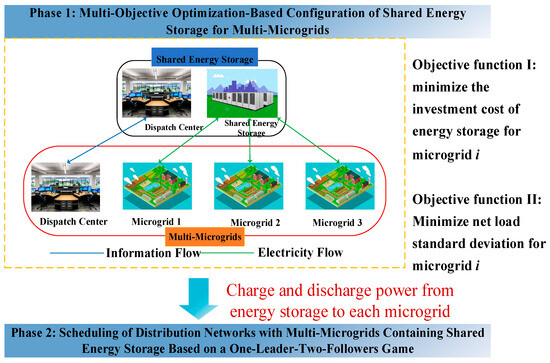

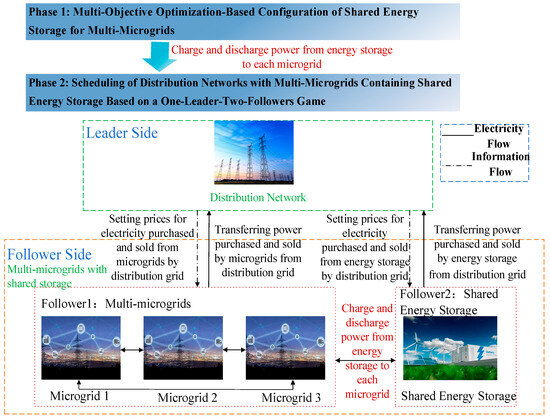

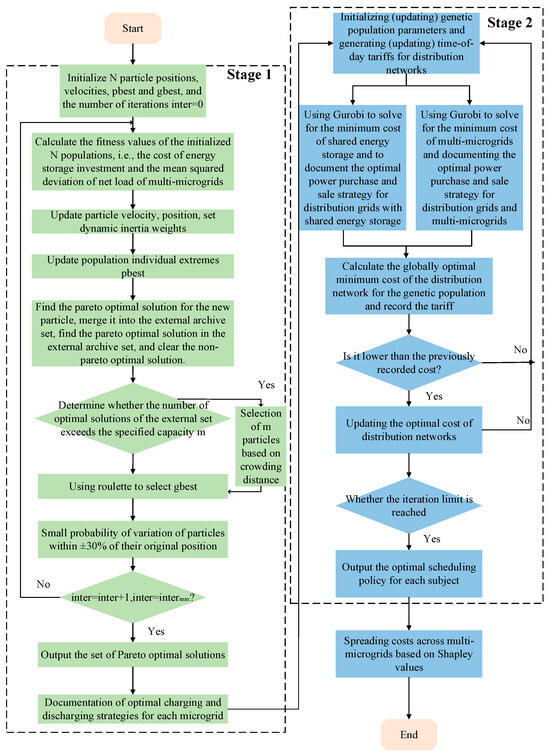

Under the carbon peaking and carbon neutrality target background, efficient collaborative scheduling between distribution networks and multi-microgrids is of great significance for enhancing renewable energy accommodation and ensuring stable system operation. Therefore, this paper proposes a collaborative optimization method for the operation of distribution networks and multi-microgrids with shared energy storage based on a multi-body game. The method is modeled and solved in two stages. In the first stage, a multi-objective optimization configuration model for shared energy storage among multi-microgrids is established, with optimization objectives balancing the randomness of renewable energy fluctuations and the economics of each microgrid undertaking shared energy storage. The charging and discharging interactive power of energy storage and each microgrid at various time periods are obtained and passed to the second stage. In the second stage, with the distribution network as the leader and shared energy storage and multi-microgrids as followers, a game optimization model with one leader and 2 followers is established. The model is solved based on an outer-layer genetic algorithm nested with an inner-layer solver to determine the electricity purchase and sale prices among the distribution network, multi-microgrids, and shared energy storage at various time periods, thereby minimizing operational costs. Finally, based on the power interaction of microgrids to measure their contributions, an improved Shapley value cost allocation method is proposed, effectively achieving a balanced distribution of benefits among the distribution network, shared energy storage, and multi-microgrids, thereby improving overall operational revenue. Meanwhile, a new method for calculating the shared energy storage capacity and the upper limit of charging and discharging power based on a game framework was proposed, which can save 37.23% of the power upper limit and 44.89% of the capacity upper limit, effectively saving the power upper limit and capacity upper limit.

1. Introduction

In the context of the “dual carbon” strategy, integrated energy microgrids have achieved rapid development due to their significant advantages in replacing fossil fuels with clean energy and promoting low-carbon and sustainable energy development. Consequently, the issue of optimal operation of integrated energy microgrids has become a focal point of research [1,2]. As the number of microgrids continues to increase, a new development paradigm of multi-microgrid joint scheduling is gradually emerging [3]. However, the coupling and interaction mechanisms between multi-microgrids and multi-energy flows are complex, and various uncertainties, such as those from energy sources and loads, are superimposed, posing unprecedented challenges to traditional optimal operation methods [4].

Scholars have achieved a series of accomplishments in the field of optimal operation research for multi-microgrids. Ref. [5] established a day-ahead low-carbon economic scheduling model for integrated energy multi-microgrids, aiming to minimize the operational costs of microgrids and promote the low-carbon operation of the system. Ref. [6] proposed a multi-microgrid scheduling strategy for electricity-hydrogen-integrated energy multi-microgrids, considering real-time energy supply and demand states and power interaction states of energy storage. With the advancement of the “dual carbon” goals, the pressure on renewable energy consumption has further increased. As a flexible resource, energy storage can effectively mitigate the intermittency of renewable energy. However, multi-microgrids face high costs in configuring energy storage. In recent years, the concept of shared energy storage has gradually emerged, providing a new approach for the development of multi-microgrid energy storage [7,8]. Ref. [9] proposed an optimal scheduling method for integrated energy multi-microgrids considering shared energy storage, which reduced the operational costs of multi-microgrids by coordinating the interactive electric power between each microgrid and shared energy storage. However, this study set the parameters on the shared energy storage side to fixed values, resulting in overly idealized outcomes. The Ref. [10] established a bi-level optimal configuration model for integrated energy multi-microgrids considering shared energy storage, verifying the economic advantages of multi-microgrid shared energy storage over individually built energy storage by each microgrid. Both Refs. [11,12] introduced demand response mechanisms on the user side, incorporated shared energy storage, and rationally allocated capacity to each microgrid, demonstrating the synergistic effect of shared energy storage and demand response in enhancing the low-carbon economic performance of multi-microgrids. The above literature focuses on the capacity allocation and operational strategies of shared energy storage in multi-microgrid scheduling, failing to consider the issue of benefit allocation between shared energy storage and multi-microgrids, as well as seeking a balance between using energy storage to smooth fluctuations and improving the economy.

When addressing energy trading issues, game theory serves as an effective tool, providing valuable insights into the challenging problem of benefit allocation among multiple entities [13,14]. Ref. [15] proposes an optimal scheduling model for multi-microgrid-shared energy storage systems, utilizing energy storage to smooth out the fluctuations from renewable energy sources integrated into each microgrid and allocating the capacity of shared energy storage in a reasonable way to ensure the maximization of benefits for both individual microgrids and the shared energy storage. The Ref. [16] constructs a cooperative game model encompassing the economic benefits of microgrids and energy storage, aiming to maximize the benefits for all parties involved and achieve a win-win situation. Both of the above-mentioned literature establish traditional game structures for multi-microgrids and shared energy storage, treating each entity as an equally powerful player. However, in real-world scenarios, complex cooperation or competition relationships exist among multiple entities. The Ref. [17] introduces a mixed-game bi-level scheduling model considering the coordination between microgrids and shared energy storage. The upper level establishes a leader-follower game framework with microgrids as leaders and prosumers as followers, while the lower level establishes a cooperative game framework between prosumers and shared energy storage. This model reflects the complex game relationships among microgrids, prosumers, and shared energy storage while ensuring the benefits of multiple entities. However, when exploring the game relationships between multi-microgrids and shared energy storage, the aforementioned literature fails to fully consider the participation of distribution networks and does not fully leverage the characteristics of multi-microgrid grid connection by incorporating the tripartite consideration of shared energy storage, multi-microgrids, and distribution networks into game-based scheduling.

The Shapley value method is a traditional cooperative game allocation method, some studies have proposed a gain allocation model based on the improved Shapley value method by combining the influencing factors of optimal scheduling with the introduction of comprehensive correction coefficients based on the Shapley value method [18], and such improvements can more accurately measure the value of the individual’s contribution, but they cannot overcome the problem of combinatorial explosion inherent in the application of the Shapley value method to large-scale systems, but cannot overcome the combinatorial explosion problem inherent in the Shapley value method when applied to large-scale systems [19]. Cooperative game parsimony algorithms have been proposed for solving the problem of allocating cooperative gains to large-scale interests. The Ref. [20] proposes to utilize the Aumann–Shapley (A–S) value method to allocate the cooperative power gains of a total of 100 hydropower plants in the Brazilian hydropower system; The Ref. [21] applies the maximum–minimum cost remaining saving (MCRS) method to the Yalong River Basin wind-photovoltaic-hydroelectricity-nine interest-body system. The maximum–minimum cost remaining saving method was applied to the problem of gaining electricity allocation of the wind-solar-water-nine benefit system in the Yalong River basin. Compared with the Shapley value method, MCRS is faster and occupies less memory. The above cooperative game parsimony algorithm can better overcome the combinatorial explosion problem in the gain allocation of large-scale subjects of interest and possesses computational efficiency, but it cannot reflect the individual advantages when utilizing the currently proposed efficiency algorithm for gain allocation. The major features of these methods are summarized in Table 1

Table 1.

Major features of decomposition methods.

Based on the problems of the above research, this paper constructs a cooperative optimization and operation method of distribution network-containing shared energy storage multi-microgrids based on a multi-body game, considering the three-way interaction of distribution networks, shared energy storage, and multi-microgrids, and the main contributions are as follows:

- (1)

- A collaborative optimization method for the operation of distribution networks and multi-microgrids with shared energy storage is proposed, based on a multi-body game framework. This method is modeled and solved in two stages. In the first stage, a multi-objective optimization configuration model and its corresponding solution algorithm are established. These are used to determine the charging and discharging powers of energy storage to each microgrid at various time periods. The results from this stage are then passed to the second stage. The use of energy storage helps effectively reduce the fluctuation of net load in microgrids while minimizing the cost of shared energy storage borne by each microgrid. This achieves a balance between smoothing renewable energy fluctuations and enhancing economic benefits among multi-microgrids.

- (2)

- In the second stage of the proposed method, a game structure is formed with one leader (the distribution network) and 2 followers (shared energy storage and multi-microgrids). This structure ensures that the scheduling of the three parties can achieve collaboration and equitable distribution of benefits. Consequently, the overall performance is enhanced, promoting effective and equitable operation within the distribution network and multi-microgrids system.

- (3)

- A new method for calculating the capacity of shared energy storage and the upper limits of charging and discharging powers based on a game-theoretic framework is proposed. Compared to the traditional approach of summing up the individually set storage capacities for each microgrid, the new method can more effectively utilize the upper limits of storage power and capacity, thereby enhancing resource utilization efficiency.

- (4)

- An improvement to the Shapley value method is proposed, where the interactive power among microgrids is used as a basis to measure their contributions to the alliance. This improvement can more accurately reflect the individual advantages of microgrids within the alliance and provides a new perspective for addressing the issue of revenue allocation among multi-microgrids.

This paper is constituted of 6 sectors. The multi-objective optimization-based configuration of shared energy storage for multi-microgrids will be stated in Section 2. Section 3 describes a scheduling model of distribution networks with multi-microgrids containing shared energy storage based on a one-leader-two-follower game. Section 4 presents a calculation method of the capacity of shared energy storage and power upper limits for charging and discharging of shared energy storage in a gaming framework. Section 5 gives the case analysis. This paper will provide a comprehensive conclusion in Section 6.

5. Case Analysis

5.1. Case Parameter Settings

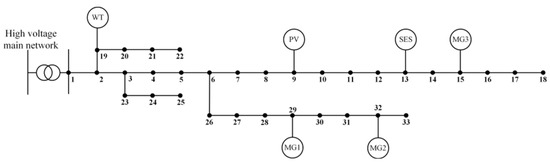

In order to verify the validity of the model and methodology developed in this paper, a simulation test was conducted using the improved IEEE33 node system. As shown in Figure 5, node 1 of the distribution network is connected to the higher-level grid and equipped with a wind farm and a PV plant, which are connected to nodes 19 and 9, respectively. Three microgrids, MG1, MG2, and MG3, are connected to node 29, node 32, and node 15, respectively, and shared energy storage is connected to node 13.

Figure 5.

Improved IEEE33 nodal graph for distribution network-multi-microgrids with shared energy storage.

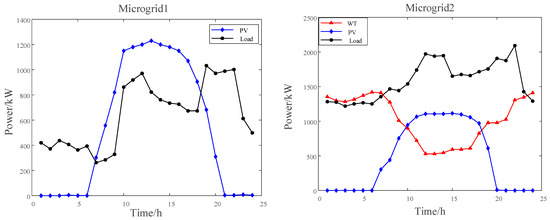

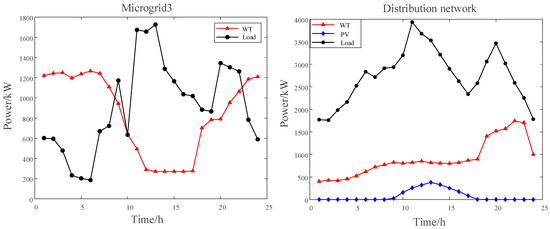

The new energy generation and load curves of the distribution network and each microgrid are shown in detail in Appendix A Figure A1, and the specific parameters of the distribution network and shared energy storage are listed in Appendix A Table A1. In the simulation process, the number of populations of the genetic algorithm is set to 20, and the number of iterations is 100.

In the case study of our paper, sensors play a critical role in monitoring and optimizing distribution networks, energy storage systems, and microgrids. The real-time data on power and voltage, essential for our analysis, were accurately captured by sensors embedded in the equipment. These data enable precise real-time decision-making and optimization, enhancing the efficiency and reliability of the integrated energy systems. By leveraging sensor information, we achieve a more responsive and balanced operation of the multi-microgrids, highlighting the transformative impact of sensor technology in modern energy management.

5.2. Energy Efficiency Analysis of Game Scheduling for Distribution Networks-Multi-Microgrids with Shared Energy Storage

The proposed method in Section 3.5 is utilized to solve the proposed game model, and the iteration results are shown in Table 2. The results converge when the genetic algorithm is iterated about 90 times. During the iterative process, the distribution network on the subject side, as a leader, usually has more goals and decision-making power, and they are able to strategize and have a significant impact on the overall gaming situation, so their costs are gradually reduced. Shared energy storage and distribution networks, as followers, are subject to the actions and strategies of the leader and can usually only be dispatched according to the leader’s decisions, hence their slightly elevated costs. After the 95th iteration, the costs of all three parties almost no longer change, proving that the strategies of all three parties are the same and they cannot unilaterally adjust their own strategies alone to realize the growth of greater benefits, i.e., the leader’s strategy and the follower’s best-response strategy match each other to reach the equilibrium of the game.

Table 2.

Genetic algorithm iteration result.

Table 3 shows the time-sharing tariffs set by the distribution network, and the prices in the valley, flat, and peak segments show a gradual upward trend, while the price of electricity sold by the distribution network to the user is always higher than the price of electricity purchased by it in each specific time period, and this pricing mechanism effectively guarantees the economic and stable operation of the distribution network.

Table 3.

Time-of-day tariffs set by the distribution network.

In order to verify the validity of the proposed one-master-two-follower game model, the distribution network is taken as the leader, and whether the shared energy storage and multi-microgrids respond to the time-sharing tariffs formulated by the distribution network as the follower is taken into consideration, and three operation schemes are set up for the comparative analysis, as shown in Table 4. Based on the solution results, the tripartite costs of the three operation schemes are compared, as shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

Comparison of three operation schemes.

Table 5.

Comparison of the tripartite costs of the three operating schemes.

In Scheme 2, the distribution network and the multi-microgrid form a master-slave game. Compared with Scheme 1, the shared energy storage cannot respond to the time-of-day tariff set by the distribution network and cannot utilize its remaining capacity after charging and discharging to the multi-microgrid, so the cost of the distribution network and the shared energy storage is elevated, and the cost of the multi-microgrid is almost unchanged.

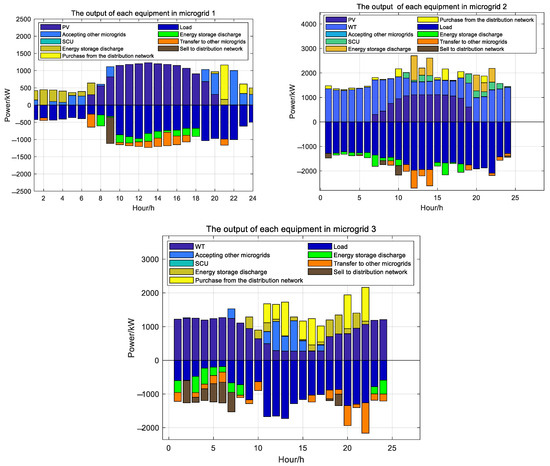

In Scheme 3, shared energy storage and multi-microgrids are dispatched separately according to fixed tariffs. Compared with Scheme 1, shared energy storage and multi-microgrids cannot respond to the time-sharing tariffs set by the distribution network, and they can only make adjustments to their own strategy of purchasing and selling electricity to the distribution network, i.e., purchasing electricity when the price of electricity is low and selling electricity when the price of electricity is high so that all three parties’ costs are elevated. Therefore, it is proved that the distribution network as a leader and shared energy storage and multi-microgrids as a follower in Scheme 1, forming a one-master-two-slave game pattern strategy, is most reasonable. The output diagram of each device in each microgrid is shown in Appendix A Figure A3.

5.3. Energy Efficiency Analysis of Scheduling with Multiple Microgrids Containing Shared Energy Storage

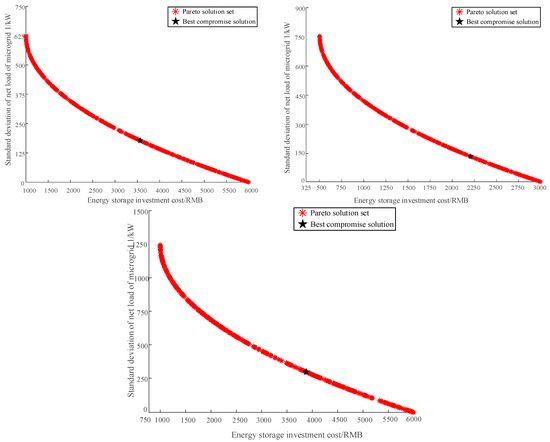

Based on the multi-objective particle swarm algorithm to solve the energy storage allocation model, the final Pareto front is shown in Appendix A Figure A2, from which the optimal compromise solution is selected based on Equations (2) and (3) as the optimal scheduling result.

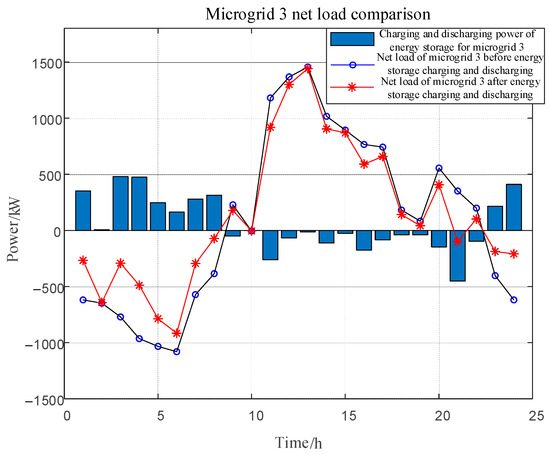

Figure 6 shows the net load fluctuation before and after sharing energy storage in each microgrid, and Table 6 shows the standard deviation of net load and energy storage investment cost before and after sharing energy storage in microgrids. The blue bar represents the charging and discharging power of the energy storage in microgrid i. Greater than 0 means that the energy storage is charging and the net load of the microgrid increases, while less than 0 means that the energy storage is discharging and the net load of the microgrid decreases.

Figure 6.

Net load fluctuations before and after sharing energy storage across microgrids.

Table 6.

Comparison of standard deviation of net load and storage investment cost before and after sharing energy storage in microgrids.

The standard deviation of net load was reduced by 52.9%, 48.6%, and 54.5% for microgrid 1, microgrid 2, and microgrid 3, respectively. It can be seen that the proposed model fully incentivizes the role of energy storage, effectively smoothing out the net load fluctuation caused by the anti-peaking characteristic of the new energy. During the low-load hours, the energy storage system stores power to alleviate the pressure of power abandonment on the grid, while during the peak-load hours, it releases power to fill the power supply gap. This mechanism helps to balance the difference between supply and demand on the grid and significantly improves the stability and reliability of the grid.

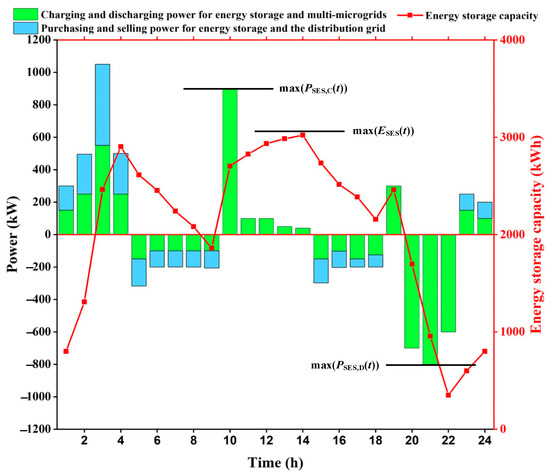

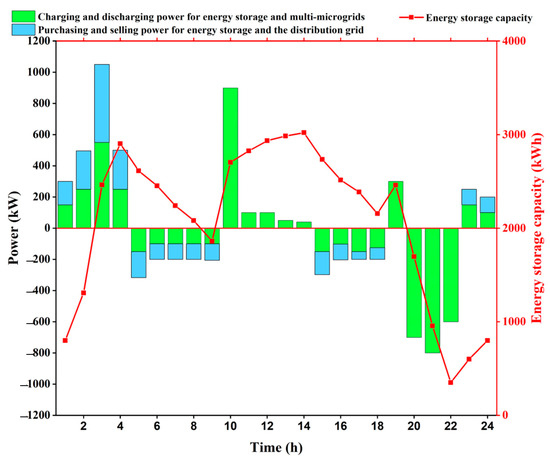

The energy storage charging and discharging power and capacity are shown in Figure 7. The green bar represents the charging and discharging power of energy storage and multi-microgrid, which is greater than 0 on behalf of energy storage charging from multi-microgrid and less than 0 on behalf of energy storage discharging to multi-microgrid; the blue bar represents the purchasing and selling power of energy storage and distribution network, which is greater than 0 on behalf of energy storage purchasing power from distribution network and less than 0 on behalf of energy storage selling power to distribution network.

Figure 7.

Energy storage charging and discharging power and capacity display.

The energy storage absorbs power from the multi-microgrids during the valley hours 1:00–4:00 and 23:00–24:00, and since the price of power sold from the distribution network is low at this time, the energy storage purchases power from the distribution network; the energy storage discharges power to the multi-microgrids during the peak hours 5:00–9:00 and 15:00–18:00, and since the price of power purchased from the distribution network is high at this time, the energy storage sells power to the distribution network, 10:00–14:00, 19:00–22:00 are the usual periods, the energy storage does not interact with the distribution network for power, and only meets the charging and discharging demand of the multi-microgrids.

Table 7 shows the comparison of the charging and discharging power and capacity upper limits for the microgrid demand, the actual energy storage, and the energy storage settings. The sum of the upper power and capacity limits of energy storage for each microgrid demand is 1349.32 kW and 5483.09 kW·h, respectively.

Table 7.

Comparison of microgrid demand, actual energy storage, and storage-set charging and discharging power and capacity limits.

Using the new method of calculating the capacity and charging/discharging power upper limit of shared energy storage under the game framework proposed in this paper, the charging/discharging power of each microgrid is aggregated and summed to obtain the net charging/discharging power. When the net charging and discharging power is provided by the shared energy storage, the actual required upper limit of storage power and upper limit of capacity are 846.94 kW and 3021.81 kW·h, respectively, which are smaller than the sum of the upper limit of storage power and upper limit of capacity demanded by each microgrid. Among them, the upper power limit saves 37.23%, and the upper capacity limit saves 44.89%. Meanwhile, it is smaller than the factory-set power and capacity upper limits of the energy storage battery, in which the power upper limit saves 29.42% and the capacity upper limit saves 62.23%. It shows that the provided shared energy storage model can use energy storage resources more efficiently and provides a useful reference for shared energy storage operating companies.

5.4. Validity Analysis of Improved Shapley Value Method

The cost comparison between microgrids before and after participating in the alliance is shown in Table 8. The total operating cost after the establishment of the microgrid alliance is RMB 8664.06, which realizes a reduction of 3.6% compared with the total cost of each microgrid operating independently before the alliance. At the same time, the costs shared by each microgrid after the alliance is also reduced compared to the independent operation, which fully proves that the alliance reaches the game equilibrium state and realizes the optimization of economic benefits.

Table 8.

Comparison of costs before and after Microgrid’s participation in the Alliance.

The comparison between the traditional Shapley value method and the improved Shapley value method is shown in Table 9. It can be seen that compared with the traditional Shapley value method, the improved Shapley value method measures the contribution to the coalition through the interaction power between microgrids, and the cost of microgrid 2 is elevated by 14.7% due to the lower interaction power between microgrid 2 and other microgrids, and the cost of microgrids 1 and 3 is reduced by 12.0% and 5.06%, respectively, due to the interaction power between microgrid 1 and microgrid 3 being higher. Power is higher, so the cost of microgrid 1 and microgrid 3 is reduced by 12.0% and 5.06%, respectively, and the overall cost of multi-microgrids is reduced by 1.06%, which not only reflects the advantages of microgrids individually in the coalition but also provides effective ideas for the problem of distributing the benefits of multi-microgrids. At the same time, the solution time was reduced by 134 s, verifying the short-time performance of the improved method.

Table 9.

Comparison of solution results.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, a cooperative optimization operation model of a distribution network-containing shared energy storage multi-microgrids based on a multi-body game is constructed, aiming to optimize the energy utilization rate of the three parties and improve comprehensive energy efficiency. The model is used for the improved IEEE33 node arithmetic test system, and the following conclusions are drawn by comparing the scheduling results of different operation schemes:

- (1)

- In the first stage, by constructing a multi-objective optimal allocation model and optimization algorithm, the balanced consideration of all objectives is achieved, effectively smoothing out the fluctuation of new energy accessed by each microgrid and reducing the cost of shared energy storage that each microgrid needs to afford.

- (2)

- In the second stage, a one-leader-two-followers game scheduling framework is constructed, which is conducive to promoting cooperation and coordination between the distribution grid, shared energy storage, and multi-microgrids, and realizing the synergy of the three-party scheduling, which can achieve a balanced distribution of the interests of the distribution grid, shared energy storage, and multi-microgrids, and thus increase the overall benefits.

- (3)

- A new method for calculating the upper limit of shared energy storage capacity and charging/discharging power based on a game framework is proposed. Compared with the sum of the energy storage capacity requirements set by each microgrid, the new method is able to realize a saving of 37.23% on the power ceiling and 44.89% on the capacity ceiling; compared with the power and capacity ceilings set by the energy storage batteries at the factory, a saving of 29.42% on the power ceiling and 62.23% on the capacity ceiling is achieved. It shows that the method can be utilized to use energy storage resources more effectively and improve the accuracy of energy storage configuration, thus providing a more economical solution for shared energy storage operating companies.

- (4)

- The Shapley value method is improved by utilizing the interaction power between microgrids to measure their contribution to the coalition. Compared with the traditional Shapley value method, this improvement leads to an increase in the cost of multi-microgrids with lower interaction power and a decrease in the cost of multi-microgrids with higher interaction power, and thus a reduction in the overall cost. The proposed method can fully reflect the individual advantages of microgrids in the coalition, thus providing a strong basis for the distribution of benefits to multi-microgrids.

We plan to focus on several key areas for future research. Firstly, we aim to develop more efficient computational algorithms to address the complexity of the multi-objective optimal allocation model, particularly when dealing with larger and more complex networks. This will enhance the real-time applicability of our model, enabling swift decision-making in practical scenarios. Secondly, we recognize the importance of refining the assumptions and parameters of our game framework to ensure the accuracy of our proposed method for calculating the upper limit of shared energy storage capacity and charging/discharging power. We plan to explore robust validation techniques and adaptive algorithms to improve the reliability of our energy storage configurations. Lastly, we will investigate alternative methods for measuring the interaction power between microgrids, with the goal of refining our improved Shapley value method. By developing more sophisticated interaction metrics, we aim to overcome the challenges associated with accurately quantifying these interactions in complex and diverse energy systems. Overall, these efforts will contribute to advancing the practical application of our energy storage and microgrid optimization strategies.

Author Contributions

H.W.: methodology, conceptualization, mathematical modeling, writing—original draft. G.C.: methodology, numerical calculation, software, writing—original draft. R.J.: methodology, writing—review and editing, analysis, validation. Y.L.: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, analysis, validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2023YFE0114600). We also greatly appreciate the helpful suggestions and comments of editors and reviewers.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used were shared in our paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yan Liang was employed by Xi’an Power Supply Company, State Grid Shaanxi Electric Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Description |

| A–S | Aumann–Shapley |

| MCRS | Maximum–minimum Cost Remaining Saving |

| OM | Operation and maintenance |

| SES | Shared Energy Storage |

| WT | Wind Turbine |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| DN | Distribution Network |

| MG | Microgrid |

| MMG | Multi-Microgrid |

| INV | Investigation |

| SCU | Small coal-fired unit |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

New energy generation and load curves for distribution networks and each microgrid.

Figure A2.

Multi-objective optimization of shared energy storage across microgrids Pareto frontier.

Figure A3.

Output diagram of each equipment in each microgrid.

Table A1.

Distribution grid and shared energy storage parameters.

Table A1.

Distribution grid and shared energy storage parameters.

| Equipment Parameter Name | Numbers and Units | Equipment Parameter Name | Numbers and Units | Equipment Parameter Name | Numbers and Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limit of capacity of shared energy storage | 8000 kW·h | Charge/discharge O&M cost per unit of power for energy storage | 0.1542 RMB/kW | Base voltage | 23 kV |

| Upper limit of power of shared energy storage | 1200 kW | Energy storage life | 10 Year | Safe voltage range for each node across the network | [0.95,1.05] p.u |

| Charge/discharge efficiency of energy storage | 95% | System baseline capacity | 100 MVA | Upper limit of branch circuit transmission power capacity | 3000 kW |

| Investment cost per unit capacity of energy storage | 1250 RMB/(kW·h) | Investment cost per unit of power for energy storage | 4375 RMB/kW | Capacity margins for shared energy storage in microgrids | 1.25 |

References

- Zhang, L.; Jin, Q.; Zhang, W.; Chen, L.; Yang, N.; Chen, B. Risk-involved dominant optimization of multi-energy CCHP-P2G-based microgrids integrated with a variety of storage technologies. J. Energy Storage 2024, 80, 110260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, M.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, T.; Fu, L. Multi-agent Stackelberg game trading strategy of electricity-gas multi-energy market considering participation of multi-energy microgrids. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2023, 43, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, W.; Guo, C. Hierarchical optimal configuration of multi-energy microgrids system considering energy management in electricity market environment. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 144, 108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liang, Y.; Jia, R.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Dang, P. Two-stage stochastic optimal scheduling for multi-microgrid networks with natural gas blending with hydrogen and low carbon incentive under uncertain environments. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, L.; Cai, J.; Luan, K.; Yang, B. Day-ahead optimized economic dispatch of CCHP multi-microgrid system considering power interaction among microgrids. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2018, 42, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, Q.; Pu, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, C.; Chen, W. Optimal configuration of an electric-hydrogen hybrid energy storage multi-microgrid system considering power interaction constraints. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2022, 50, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Yang, H. Day-ahead scheduling of community shared energy storage based on federated reinforcement learning. Chin. J. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Lyu, R.; He, J.; Pei, Y.; Qiu, W.; Yang, L.; Lin, Z.; Wen, F. Decentralized trading mechanism for joint frequency regulation of shared energy storage considering incomplete information disclosure. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2023, 47, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z. Optimal eco-nomic scheduling for multi-microgrid system with combined cooling, heating and power considering service of energy storage station. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2019, 43, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, C. Bi-level optimal con-figuration for combined cooling heating and power mul-ti-microgrids based on energy storage station service. Power Syst. Technol. 2021, 45, 3822–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, S.; Mi, L. Bi-level optimal scheduling of multi-microgrid system considering demand re-sponse and shared energy storage. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2023, 43, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Ma, Z. Shared energy storage capacity allocation and dynamic lease model consider-ing electricity-heat demand response. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2021, 45, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G.; Chen, X.; Yuan, H.; Wei, Y.; Li, F. A cooperative game approach for coordinating multi-microgrid operation within dis-tribution systems. Appl. Energy 2018, 222, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Ji, X.; Hu, X.; Cheng, P.; Du, Y.; Liu, M. Autonomous optimized economic dispatch of active distribution system with multi-microgrids. Energy 2018, 153, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xie, S.; Fang, Z.; Li, F.; Cheng, S. Optimal configuration of shared energy storage for multi-microgrid and its cost allocation. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2021, 41, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Ma, Z.; Wang, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, H. Optimal operation of shared energy storage and integrated energy microgrid based on Leader-follower Game Theory. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 47, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Liu, J.; Tang, Z.; Ceng, P.; Jiang, B.; Ma, G. Coordinated optimization of mixed microgrid multi-agent game considering multi-energy coupled shared energy storage. Autom. Elec. Tric. Power Syst. 2024, 48, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Jiang, Y. Wind power fluctuation cost allocation based on improved Shapley value. Power Syst. Technol. 2021, 45, 4387–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, J.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, D. Synergistic benefit allocation method for wind-solar-hydro complementary generation with sampling-based Shapley value estimation method. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2021, 41, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, E.; Barroso, L.A.; Kelman, R.; Granville, S.; Pereira, M.V. Allocation of firm-energy rights among hydro plants: An Aumann–Shapley approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2009, 24, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, J.; Chen, X.; Zhan, Y.; Zhou, L. Cooperative game-based synergistic gains allocation methods for wind-solar-hydro hybrid generation system with cascade hydropower. Energies 2020, 13, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).