Abstract

This research unveils a cutting-edge navigation system for deep space missions that utilizes cosmic microwave background (CMB) sensor readings to enhance spacecraft positioning and velocity estimation accuracy significantly. By exploiting the Doppler-shifted CMB spectrum and integrating it with optical measurements for celestial navigation, this approach employs advanced data processing through the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF), enabling precise navigation amid the complexities of space travel. The simulation results confirm the system’s exceptional precision and resilience in deep space missions, marking a significant advancement in astronautics and paving the way for future space exploration endeavors.

1. Introduction

As humanity continues its quest to unravel the mysteries of the cosmos, the number of deep space missions has remarkably increased [1,2,3]. This surge in exploration is driven by an innate desire to understand our place in the Universe and seek solutions to Earth-bound challenges through the lens of space discovery. The assertion that lunar, martian, asteroid, and comet explorations could yield profitable returns for private entities has been discussed in depth in the literature [4,5,6]. Furthermore, some space agencies, like National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), have outlined a clear directive to expand our reach to the moon’s surface and into the depths of space [7].

This ambitious roadmap underlines the importance of advancing deep space navigation capabilities, which remains a significant open problem in the field of astronautics [8]. The current navigation techniques for this scenario predominantly rely on Earth-based measurements to determine the spacecraft’s position [9]. However, the distances involved in deep space missions challenge the efficacy of navigational signal broadcasting. Increased distances result in more significant errors in spacecraft location determination. Additionally, greater distances reduce downlink rates, necessitating more extended periods to receive signals from spacecraft. This situation underscores the complexities and limitations inherent in long-range signal emission.

Considering these difficulties, autonomous navigation (AutoNav) has been designed to reduce dependence on systems that rely on Earth, allowing for more adaptable navigation and possibly lowering the costs and complexities of mission planning [3]. A crucial element of this approach is optical navigation (OpNav), which uses images to help the spacecraft navigate. OpNav is mainly used in two different methods [10]. First, it predicts the expected location of a target’s image in a photo based on the spacecraft and the target’s positions and velocities, camera orientation, and optical specifications. Second, it involves processing digital pictures to find the exact coordinates of the celestial bodies captured in these images.

Other innovative AutoNav methods, such as X-ray navigation (XNAV) and gamma-ray source localization-induced navigation and timing (GLINT), have been explored recently [11,12], utilizing naturally occurring signals. XNAV is a method where a spacecraft’s position and velocity are determined using X-ray signals from pulsars, calculated through the differences in time of arrival (TOA) of these signals. GLINT, focusing on gamma-ray bursts from deep space, assists in continuously updating a spacecraft’s location and movement. Unlike XNAV’s approach to calculating absolute spacecraft positioning, GLINT specializes in determining the relative distance between an observer and a reference point aligned with the direction of a distant cosmic source.

Each navigation technique presents distinct challenges and may only be suitable for some stages of a mission or different missions [13]. For instance, critical maneuvers often require real-time data, whereas extended phases like cruising emphasize utmost accuracy to minimize the need for significant corrections. The diverse requirements for precision and immediate data across various stages of deep space missions call for a navigation system that amalgamates data from multiple sources. In essence, a multi-source information fusion approach becomes indispensable [14]. Consequently, a composite navigation strategy, which harnesses sensors to assess both position and velocity, can markedly enhance the precision and reliability of deep space navigation systems. Furthermore, as of the current writing, no comparable method has been identified in the existing literature, highlighting the novelty and contribution of this work to the space field.

This paper introduces an innovative navigation system for deep space exploration that leverages the unique characteristics of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) as a novel reference signal. It is combined with celestial navigation (CeleNav) to create a comprehensive solution. This method marks a substantial advancement in navigation via signal of opportunity (NAVSOP), offering a paradigm shift towards fully autonomous navigation. By harnessing naturally occurring signals, this innovative technology equips spacecraft to ascertain their status and position independently, a capability that remains effective irrespective of the spacecraft’s distance from its starting point.

The use of the Doppler effect in reference signals for navigation is not new. Two methods stand out within the NAVSOP signals, which occur due to natural events. One utilizes the Doppler shift of the solar spectra [15], and the other employs the relativistic Doppler effect on stars [16]. Both methods face technological challenges in their implementation [16,17]. The use of the CMB differs from these methods as it employs different types of sensors, such as bolometers and radiometers, which also have technological difficulties, as is discussed later.

The structure of this article is designed to guide the reader through a comprehensive study. Section 2 delves into the theoretical underpinnings of the CMB, highlighting its pivotal role as a navigational aid in the space. Section 3 outlines translating CMB signals, considered previously filtered from foreground noise, into a quantifiable measure of spacecraft velocity. Section 4 includes a preliminary discussion on the feasibility of measuring the CMB. Section 5 introduces our innovative navigation system, which synergistically combines CMB data with traditional CeleNav techniques to enhance accuracy in deep space navigation significantly. Section 6 presents an array of simulation results alongside a discussion of the practical implications of our findings, firmly positioning our research at the forefront of astronautical science and future exploratory missions. Concluding the article, Section 7 briefly summarizes our key outcomes and outlines prospective avenues for further investigation.

3. Methodology for CMB Velocity Determination

The concept of CMB serving as a navigational signal is rooted in its unique properties and relevant theoretical frameworks. CMB’s isotropic nature, omnipresence, and inherent anisotropies resulting from the Doppler effect make it a compelling candidate for a navigational beacon for interstellar travel.

The premise, established early in the 20th century by Hasenöhrl and Von Mosengeil, that an observer moving relative to a thermal bath perceives radiation differently forms the basis of this concept [30]. However, deriving the amplitude of the effect in temperature is not straightforward. The works carried out by Condon and Harwit [36], Heer and Kohl [38], and Peebles and Wilkinson [39] achieved this derivation using transformations of energy and angles and their relationship. In this research, the derivation follows a more straightforward path, the one used in [37]. It starts evoking the Lorentz-invariance of distribution functions of particles of momentum in phase space [42].

Therefore, considering two reference systems, one fixed in the observer (f subscript) and the other one at rest with the last scattering surface (s subscript):

In that regard, if an observer is moving, the Lorentz transformation for the energy of the photon, , is

in which c is the velocity of the light, is the velocity of the observer, p is the magnitude of the momentum, and is the direction of the observation.

Applying this to a blackbody distribution function and using Lorentz-invariance of distribution functions reveals

where h is Planck’s constant, k is Boltzmann’s constant, T is the absolute temperature, and is the photon’s energy.

This implies an equation representing the directionality of the temperature measurement as

Consequently, an observer moving relative to the CMB rest frame perceives a Doppler-shifted CMB spectrum, hotter (blue-shifted) in the direction of motion and colder (red-shifted) in the opposite direction.

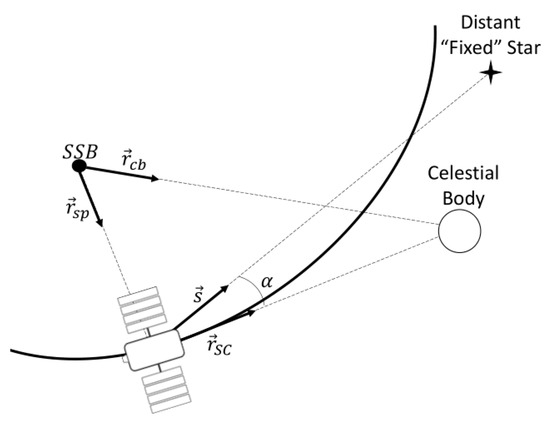

It is worth mentioning that in the case of a measurement made by a spacecraft on an interplanetary journey in the solar system, the velocity to be considered in Equation (6) is the sum of the spacecraft’s velocity to the SSB, and the velocity of the SSB to the last scattering surface, :

The latter velocity is known to be 370 km/s toward [43], where l is the galactic longitude and b is the galactic latitude.

Therefore, because of the nonlinearities in Equation (6), it is essential to understand the impact of variations in the variables and the effects on the temperature measurement. The two topics to highlight are velocity magnitude and velocity direction.

Increasing the velocity magnitude causes the temperature measurement to deviate further from the monopole temperature, and higher velocities imply a greater difference. A measurement more aligned with the velocity also shows a temperature deviation greater than the monopole temperature. This occurs because the velocity’s perpendicular component influences the measurement less, as inferred from Equation (6).

Expanding on Equation (2), which is a model of the CMB sky signal measured by a sensor, and incorporating Equation (6) for the term , since it shows the deformation caused by the Doppler effect on the temperature measurement, a novel equation is formulated to establish a relationship between the spacecraft’s velocity and the temperature measurement. Including noise, , in this model is critical, as it accounts for the inherent imperfections in foreground models that need to be extracted from the sky signal. There are other factors, including, but not limited to, systematic errors introduced during the calibration and filtering of raw sky data. Therefore, it can be noticed that

Thus, filtering techniques are crucial in data analysis for minimizing the impact of and , significantly improving the raw data quality. This approach is instrumental in reducing noise and outliers, yielding a clearer and more accurate depiction of the underlying patterns or trends in the data. The primary aim is to distill essential information from the data while preserving its original structure. Following the application of a filter, Equation (8) can be reformulated for an estimate of the CMB’s temperature, , ready for use in estimation algorithms or for analytical solutions:

Addressing Equation (9) analytically poses significant challenges due to the complexity of solving nonlinear systems. This necessitates the use of advanced mathematical strategies and sophisticated computational algorithms. Techniques like optimization or iterative processes, especially those derived from the Newton method [44], are particularly effective in navigating these nonlinear equations [45]. However, the unique conditions of this analysis add layers of complexity, such as the critical ratio, which could lead to a singular Jacobian matrix and significantly affect numerical accuracy, especially with values nearing zero.

Moreover, the precision of initial estimates becomes a considerable challenge, notably in the early phases of determining a spacecraft’s trajectory or position [46]. The current state of CMB measurement technology requires sensors to be directed at a specific point in space for extended periods to amplify the signal-to-noise ratio and filter out extraneous noise [20]. However, advancements in sensor technology, as described in [41], hint at the possibility of new sensing methods that could circumvent these limitations.

Given these considerations, the unscented Kalman filter (UKF) was selected for its ability to mitigate Gaussian noise while maintaining the integrity of the original dataset. Unlike other filters, the UKF does not require solving the nonlinear equations directly and offers resilience in scenarios of sporadic sensor input. This choice underscores the UKF’s versatility in handling complex data analysis tasks, offering a robust solution to the intricate problem of accurately estimating states in the presence of nonlinear dynamics and measurement uncertainties.

6. Simulation and Analysis

The intricate exploration of cosmic environments requires rigorous testing and validation procedures for the methodologies devised. In this context, simulations provide a safe and controllable environment to evaluate and fine-tune the proposed methods. The significance of the testing phase is amplified when dealing with novel approaches, such as utilizing CMB for deep space spacecraft navigation.

The primary objective of the simulations conducted in this section is to verify the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed integrated navigation system. These simulations examine the novel concept of exploiting the CMB’s unique properties to estimate the velocity of a spacecraft in deep space.

The simulations incorporate more realistic conditions, focusing on the full scope of the navigation system. This phase considers the coordinate frame for spacecraft navigation using the SSB Cartesian coordinate system defined by , where represents the plane of the ecliptic, with the center at the SSB and the reference epoch J2000. Furthermore, it entails introducing noise and a range of potential error sources into the simulation to mimic real-world environments. The aim is to evaluate the method’s capability and precision in scenarios more accurately, reflecting some real-world conditions, specifically targeting complete position and velocity estimation situations, and building upon the theoretical framework and deductions outlined in Section 5 for the UKF filter.

The results derived from these simulations elucidate the proposed method’s performance and potential, helping identify its strengths and weaknesses. This analysis also uncovers potential areas for further research and improvement, providing a solid foundation for future studies aiming to refine and optimize the proposed method.

6.1. Initial Conditions for the Simulation

The scenario simulated is a navigation journey from Earth to Mars. Some of the parameters and conditions of the simulation were based on similar simulations [78,79,80], which, despite having differences in sensors and applications, generally shared similar ideas. This approach was taken to validate and compare the results obtained in this study. The spacecraft’s initial position and velocity in the SSB Cartesian system are detailed in Table 1 and were determined using the Jet Propulsion Laboratory Horizons System [81]. It is important to highlight that a journey with such initial position and velocity parameters requires approximately 180 days to complete. The date considered was 15 April 2023. The spacecraft considered has a mass of 500 kg and a sectional surface area of 1 m2.

Table 1.

The initial position and velocity for both simulation phases considering the coordinate frame for spacecraft navigation as the SSB ecliptic J2000 system.

The reference orbit for this simulation is created using the general mission analysis tool (GMAT), considering all planetary bodies as point mass perturbations and accounting for solar flux drag. The UKF was implemented using MATLAB. An important part of this phase is the introduction of initial position and velocity errors, set at 10 km and 10 m/s, respectively, in all directions. These errors serve as the worst-case scenario. This approach examines the resilience and adaptability of the navigation system under unfavorable scenarios.

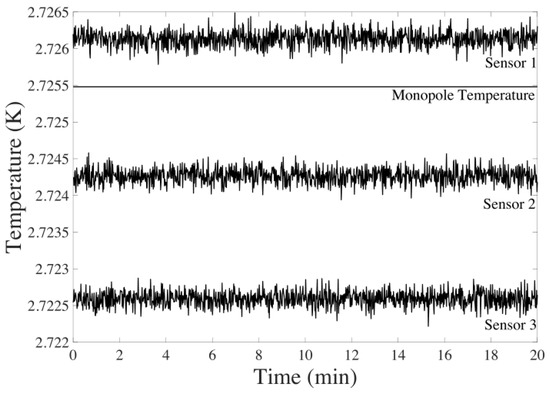

The synthetic CMB data are produced following Equation (6). The noise in this scenario is modeled as a Gaussian distribution with a zero mean and a standard deviation of 100 K. This accounts for temperature fluctuations () and minor noise that may arise during the foreground elimination step [26].

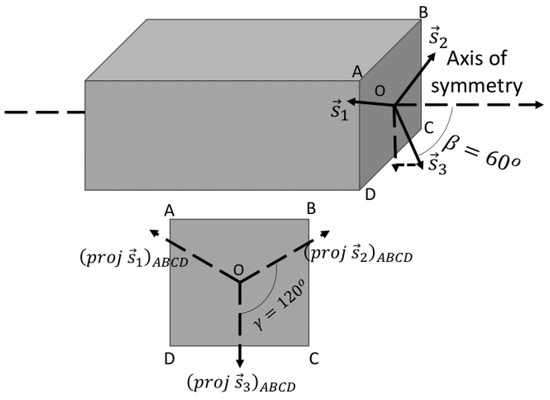

Furthermore, three CMB sensors are considered, and the placement of these sensors is at a 60° angle relative to the spacecraft’s axis of symmetry (Figure 3). They are positioned equidistantly from each other; in this case, the angle between them is 120°.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the CMB sensor’s placement on the spacecraft.

An example of the data generated for three sensors can be viewed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

CMB signal generated with 100 for 20 min of flight.

6.2. CeleNav Method

The first method, UKF within just CeleNav sensors, is presented to enhance the comparative analysis. This examination concentrates explicitly on utilizing Venus, Mars, and Earth as reference celestial bodies, providing a focused context for understanding the efficacy of UKF in this setting. It uses the group (as per Equation (22)) as the only measurement model.

Notably, it introduces a pointing error to simulate the mistakes in finding the center of the observed celestial body. The error is characterized by a fixed angular magnitude of arcseconds, with its direction, , being uniformly distributed in Plane , as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematics of the pointing errors applied to the CeleNav method simulation caused by mistakes in finding the center of the observed celestial body.

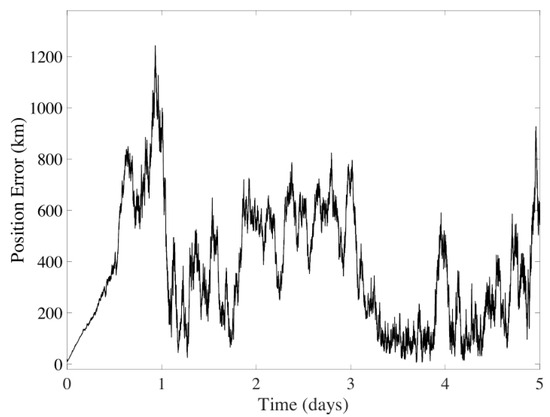

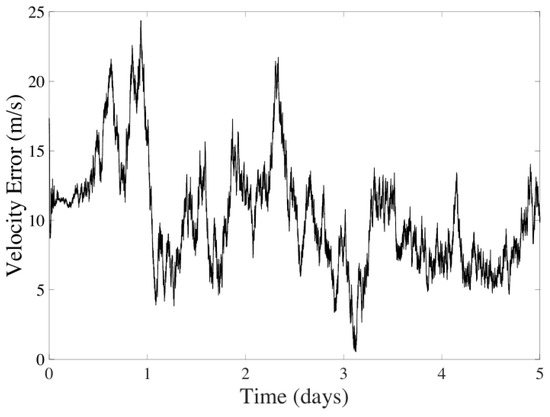

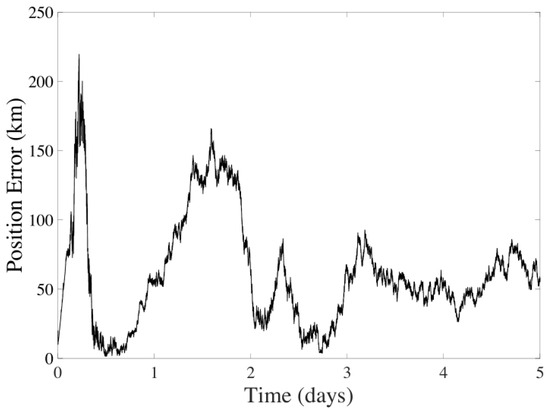

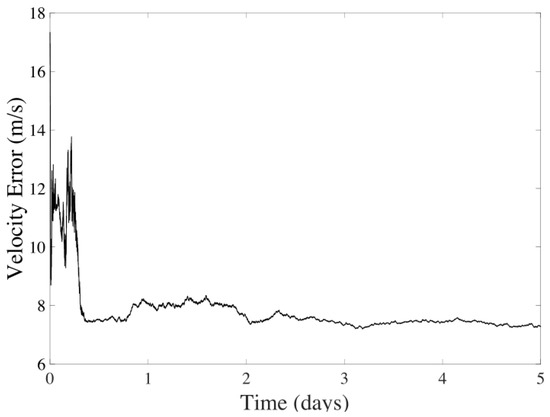

The filter results for five days of navigation are displayed in Figure 6 and Figure 7. It is observed that the average error for the position is km, and for velocity, it is m/s, discarding the instabilities of the filter during the first day. The method’s performance shows significant variability due to errors and the spatial gap between the spacecraft and celestial bodies.

Figure 6.

Position error in the UKF considering CeleNav sensors over five days of navigation between Earth and Mars.

Figure 7.

Velocity error in the UKF considering CeleNav sensors over five days of navigation between Earth and Mars.

Accuracy enhancement is possible by using closer, smaller celestial bodies like Mars’ moons as reference points, which can significantly minimize errors in pinpointing the centers of celestial bodies and in distance measurement, as highlighted in [78]. However, their applicability is restricted chiefly to Mars-focused missions. This research maintains a broader, more generalized approach to ensure a more universally applicable navigation method, aiming to develop a versatile and efficient system across the solar system, thereby maximizing its usefulness in various space exploration contexts. Therefore, it will not be made a particular enhancement to the actual method.

6.3. CMB Method

Next, the UKF filter using only CMB sensors is presented. Consequently, the measurement model is exclusively employed (Equation (20)). The synthetic data used for these sensors are consistent with what is depicted in Figure 4.

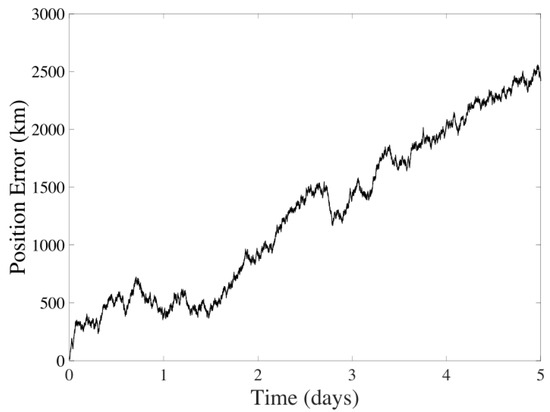

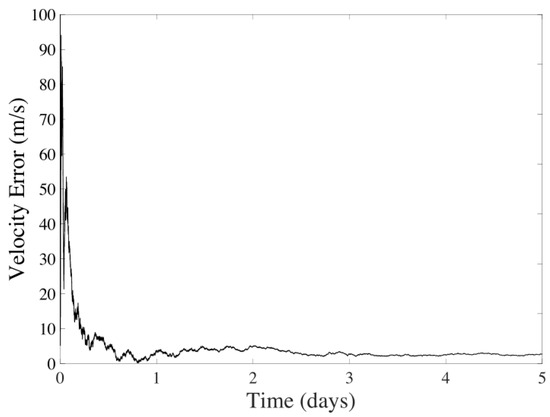

As shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, there is a noticeable decrease in velocity error over five days while the positional data diverges. It is observed that the average error for the position is km, and for velocity, it is m/s.

Figure 8.

Position error in the UKF considering CMB sensors over five days of navigation between Earth and Mars.

Figure 9.

Velocity error in the UKF considering CMB sensors over five days of navigation between Earth and Mars.

The divergence is attributed to the method relying solely on measurements related to velocity and the simplistic spacecraft’s state dynamics model. In this model, position is determined through a straightforward integration of velocity, which leads to an accumulation of errors over time. Incorporating position-related measurements into the model could correct this error, but such data are unavailable in the current setup.

An important observation is the sensors’ ability to provide accurate velocity data. In this context, there is no need for a filter to smooth the data, as the current noise level is within the filter’s handling capacity. However, in scenarios where noise types significantly deviate from the Gaussian assumption for or in Equation (8), adopting a dual estimation process, as explored in [75], can become the solution. This work will not explore this, but it can be a starting point for further studies.

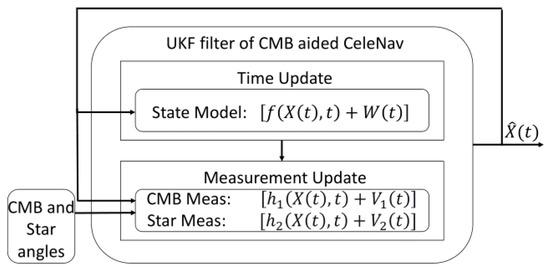

6.4. Hybrid Method

The concluding navigation strategy combines CMB and CeleNav sensors, as depicted in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11, the position and velocity filtering outcomes highlight the UKF’s adeptness at deducing state variables from complex models and sensor inputs. While variations are more pronounced in the position data, a decreasing trend in instability is observed for both variables.

Figure 10.

Position error in the UKF considering CMB-aided CeleNav over five days of navigation between Earth and Mars.

Figure 11.

Velocity error in the UKF considering CMB-aided CeleNav over five days of navigation between Earth and Mars.

This trend underscores the filter’s effectiveness in dynamically estimating states, even within nonlinear systems. Notably, the position error trends demonstrate a move towards stabilization in the initial fluctuations, showcasing the UKF’s capability to handle transient errors and maintain consistent error rates. This stabilization is significantly attributed to the accurate velocity estimations provided by the CMB sensors, which aid the CeleNav sensors in determining a more stable position value. Such evidence solidifies the UKF’s precision and dependability in state estimation amid the challenges posed by nonlinear dynamics and measurement noise complexities.

6.5. Analysis of the Three Methods

Before concluding, verifying whether the simulation results are consistent with other simulations is important. In this research, the position and velocity errors were found to be consistent with those reported in other studies. For example, celestial navigation using stellar spectra shift velocity measurements [80], X-ray-pulsar-aided CeleNav [78], differential X-ray-pulsar-aided CeleNav [78], Doppler-measurement-aided CeleNav [79], and differential Doppler-measurement-aided CeleNav [79] demonstrated similar results. Although the specific values vary based on the characteristics of each navigation system and certain specifics of this research, these comparisons generally support the concordance of the results, helping to verify that no gross simulation errors occurred.

Moreover, it is pertinent to juxtapose the three navigation strategies examined herein. The trio comprises the UKF with CeleNav sensors alone, the UKF with only CMB sensors, and the UKF integrating both CMB and CeleNav sensors. The evaluation is primarily based on the mean error and standard deviation concerning position and velocity, as shown in Table 2. Moreover, an assessment of the inherent pros and cons of each strategy is in order.

Table 2.

The mean and standard deviation for the error in the state variables for different navigation approaches from day 1 to 5.

The first approach, leveraging CeleNav sensors, employs the measurement model (Equation (22)) to capture the orientation and positions of celestial bodies, thus providing detailed data for state estimation. This technique results in mean position and velocity errors of km and m/s, alongside standard deviations of km and m/s, respectively. Although this strategy enhances position accuracy over the second method, it can encounter difficulties in accurately determining the centers of celestial bodies, as highlighted in [78]. Moreover, it necessitates selecting orbits that offer clear visibility of celestial bodies, potentially restricting orbital options.

The second approach utilizes only CMB sensors and follows the measurement model (Equation (20)), capitalizing on the isotropic characteristics of CMB radiation. This facilitates sensor orientation that is aligned with mission goals without limiting orbit selection. It achieves notable accuracy in velocity estimation, with a mean error of m/s and a standard deviation of m/s. However, its disadvantage lies in the position estimation, leading to a significant accumulated error that extrapolates filter capacity, as indicated by a divergence behavior.

The integration of CMB and CeleNav sensors in the hybrid approach leverages the measurement model (Equation (19)), effectively combining the strengths of both types of sensors to mitigate their weaknesses. This collaborative strategy significantly enhances the stability of state variable estimations. Notably, it results in a five-fold decrease in the mean and standard deviation of position error compared to using CeleNav sensors alone. Compared with using CMB sensors exclusively, the hybrid approach demonstrates superior performance, as the latter scenario leads to filter divergence and suboptimal results. The fusion of data from both sensor types consequently yields state estimations for positions prominent to those obtained independently by either sensor type.

For velocity estimation, the hybrid method shows a remarkable improvement in the error standard deviation, almost eleven times better than the CeleNav-only approach and three times better than the CMB-only method. However, the mean velocity error presents a mixed picture: it improves from m/s to m/s compared to the CeleNav-only method. Still, it shows a decline in accuracy from m/s to m/s compared to the CMB-only approach, which is attributed to the higher error rates of CeleNav sensors. Despite this, the hybrid method yields a more stable outcome for velocity estimation. This approach not only boosts the overall accuracy of navigation but also validates the practical application of CMB data in real-time navigation, showcasing the potential of a synergistic sensor strategy.

The hybrid UKF approach also promotes operational adaptability. While the CeleNav sensors might falter during specific mission phases, such as when obstructed by planetary shadows or poorly aligned celestial bodies, the CMB sensors maintain consistent performance. Thus, the integration ensures seamless state estimation for the entire mission duration.

Summarizing these findings, the CeleNav method shows a reasonable performance but necessitates orbits with conditions that ensure the visibility of enough celestial objects for navigation; unsuitable orbits may hinder this. The CMB-focused UKF strategy excels in velocity estimation, albeit with limitations in position estimation. Conversely, the integrated UKF method offers a balanced and effective solution, enhancing data utility, reducing errors in position estimation, and ensuring more consistent velocity measurements. This approach also provides a fail-safe mechanism by compensating for potential sensor failures. Its resilience and versatility make it a compelling choice for mission planners seeking the highest navigational accuracy and reliability levels.

7. Conclusions

In essence, this study addresses the complexities of deep space navigation by utilizing CMB signals. It introduces a pioneering navigation system that enables spacecraft to autonomously determine their status, independent of their position within the solar system. Although not extensively tested in various solar system locales, the theoretical underpinnings suggest its universal applicability. The work demonstrates the system’s feasibility and efficiency by exploiting the unique characteristics of the CMB as a novel navigational beacon. This is further enhanced by integrating CMB data with CeleNav techniques, showcasing a harmonious blend of traditional and avant-garde methods for space exploration.

Looking ahead, the scope for further advancement is vast. Prospective developments could explore advanced technologies and operational systems suitable for next-generation CMB navigation frameworks. Enhancing the system’s robustness in high-noise environments through a dual estimation filter is a promising avenue. Additionally, investigating alternative strategies for sensor data integration could significantly refine the navigation system’s precision and dependability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K.d.A., W.G.d.S. and P.C.; methodology, P.K.d.A.; software, P.K.d.A. and A.B.; validation, P.K.d.A., W.G.d.S. and P.C.; formal analysis, P.K.d.A. and W.G.d.S.; investigation, P.K.d.A.; resources, P.C. and A.B.; data curation, P.K.d.A.; writing—original draft preparation, P.K.d.A. and W.G.d.S.; writing—review and editing, P.K.d.A., W.G.d.S., P.C. and A.B.; visualization, P.K.d.A. and A.B.; supervision, W.G.d.S. and A.B.; project administration, P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Deutsch, L.J.; Townes, S.A.; Liebrecht, P.E.; Vrotsos, P.A.; Cornwell, D.M. Deep space network: The next 50 years. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Space Operations, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 16–20 May 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, H.H. The Deep Space Network: Overburdened and underfunded. Phys. Today 2023, 76, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, E.; Speretta, S.; Gill, E. Autonomous navigation for deep space small satellites: Scientific and technological advances. Acta Astronaut. 2022, 193, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, L.; Cropper, M.; Rao, A. Space exploration and economic growth: New issues and horizons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2221341120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, I.A. Lunar resources. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2015, 39, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhu, R.S.; Pelton, J.N.; Nyampong, Y.O.M. The importance of natural resources from space and key challenges. In Space Mining and Its Regulation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurbuchen, T. Science 2020–2024: A Vision for Scientific Excellence; Technical Report; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Deutsch, L.J.; Dowen, A.; Townes, S.; Guinn, J.; Wyatt, E.J.; Levesque, M.; Chang, S. Autonomy for Deep Space Communications and Navigation. In Proceedings of the SpaceOps 2021, Cape Town, South Africa, 3–5 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskaran, S. Autonomous navigation for deep space missions. In Proceedings of the SpaceOps 2012, Stockholm, Sweden, 11–15 June 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, W.M.J. Methods of Optical Navigation. In Proceedings of the AAS/AIAA Space Flight Mechanics Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, 13–17 February 2021. AAS 11–215. [Google Scholar]

- Graven, P.; Collins, J.; Sheikh, S.; Hanson, J.; Ray, P.; Wood, K. XNAV for deep space navigation. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual AAS Guidance and Control Conference, Breckenridge, CO, USA, 1–6 February 2008. AAS 08–054. [Google Scholar]

- Hisamoto, C.S.; Sheikh, S.I. Spacecraft Navigation Using Celestial Gamma-Ray Sources. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2015, 38, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Cui, P.; Crassidis, J.L. Design and optimization of navigation and guidance techniques for Mars pinpoint landing: Review and prospect. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 94, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X. Introduction. In Spacecraft Autonomous Navigation Technologies Based on Multi-Source Information Fusion; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Henderson, T.A.; Hurtado, J.E.; Junkins, J.L. Development of spacecraft orbit determination and navigation using solar Doppler shift. In Proceedings of the AAS/AIAA Space Flight Mechanics Meeting, Ponce, Puerto Rico, 9–13 February 2003. AAS 03–159. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, J.A. StarNAV: Autonomous optical navigation of a spacecraft by the relativistic perturbation of starlight. Sensors 2019, 19, 4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, R.; Wildey, R. Fundamental limitations to optical Doppler measurements for space navigation. In Proceedings of the IRE; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1961; Volume 49, pp. 1655–1659. [Google Scholar]

- Durrer, R. The theory of CMB anisotropies. J. Phys. Stud. 2001, 5, 177–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrer, R. The Cosmic Microwave Background; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.L.; Larson, D.; Weiland, J.L.; Jarosik, N.; Hinshaw, G.; Odegard, N.; Smith, K.; Hill, R.; Gold, B.; Halpern, M.; et al. Nine-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observations: Final maps and results. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2013, 208, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, F.K.; Banday, A.J.; Górski, K.M. Testing the cosmological principle of isotropy: Local power-spectrum estimates of the WMAP data. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2004, 354, 641–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhal, B.S.; Guezmir, A. The Horizon Problem. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1269, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoot, G.F. Nobel Lecture: Cosmic microwave background radiation anisotropies: Their discovery and utilization. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2007, 79, 1349–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Dodelson, S. Cosmic microwave background anisotropies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2002, 40, 171–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, M. Physics of the cosmic microwave background anisotropy. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2015, 24, 1530004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommesen, H.; Andersen, K.J.; Aurlien, R.; Banerji, R.; Brilenkov, M.; Eriksen, H.K.; Fuskeland, U.; Galloway, M.; Mocanu, L.M.; Svalheim, T.L.; et al. A Monte Carlo comparison between template-based and Wiener-filter CMB dipole estimators. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 643, A179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixsen, D.J.; Cheng, E.S.; Gales, J.M.; Mather, J.C.; Shafer, R.A.; Wright, E.L. The Cosmic Microwave Background Spectrum from the Full COBE FIRAS Data Set. Astrophys. J. 1996, 473, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, R.; Ade, P.; Aghanim, N.; Arnaud, M.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Banday, A.; Barreiro, R.; Bartolo, N.; et al. Planck 2015 results—VIII. High Frequency Instrument data processing: Calibration and maps. Astron. Astrophys. 2016, 594, A8. [Google Scholar]

- Kogut, A.; Lineweaver, C.; Smoot, G.F.; Bennett, C.L.; Banday, A. Dipole anisotropy in the COBE DMR first-year sky maps. arXiv, 1993; arXiv:9312056. [Google Scholar]

- Melchiorri, B.; Melchiorri, F.; Signore, M. The dipole anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation. New Astron. Rev. 2002, 46, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenöhrl, F. Zur Theorie der Strahlung in bewegten Körpern. Ann. Phys. 1904, 320, 344–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Mosengeil, K. Theorie der stationären Strahlung in einem gleichförmig bewegten Hohlraum. Ann. Phys. 1907, 327, 867–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, W. Theory of Relativity; Courier Corporation: North Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Penzias, A.A.; Wilson, R.W. Measurement of the Flux Density of CAS a at 4080 Mc/s. Astrophys. J. 1965, 142, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.; Sciama, D. Peculiar velocity of the sun and its relation to the cosmic microwave background. Nature 1967, 216, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, J.J.; Harwit, M. Means of Measuring the Earth’s Velocity through the 3° K Radiation Field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1968, 21, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, M.A. The Compton-Getting effect for cosmic-ray particles and photons and the Lorentz-invariance of distribution functions. Planet. Space Sci. 1970, 18, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heer, C.; Kohl, R. Theory for the Measurement of the Earth’s Velocity through the 3° K Cosmic Radiation. Phys. Rev. 1968, 174, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peebles, P.; Wilkinson, D.T. Comment on the anisotropy of the primeval fireball. Phys. Rev. 1968, 174, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puget, J.L. The planck mission and the cosmic microwave background. In The Universe: Poincaré Seminar 2015; Birkhäuser: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abitbol, M.H.; Ahmed, Z.; Barron, D.; Thakur, R.B.; Bender, A.N.; Benson, B.A.; Bischoff, C.A.; Bryan, S.; Carlstrom, J.E.; Chang, C.L.; et al. CMB-S4 Technology Book, First Edition. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.02464. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1706.02464 (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Klimontovich, Y.L. The Statistical Theory of Non-Equilibrium Processes in a Plasma: International Series of Monographs in Natural Philosophy; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Darling, J. The universe is brighter in the direction of our motion: Galaxy counts and fluxes are consistent with the CMB Dipole. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2022, 931, L14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, C.T. Solving Nonlinear Equations with Newton’s Method; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, S. Fundamentals of Optimization Techniques with Algorithms; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Battin, R.H. An Introduction to the Mathematics and Methods of Astrodynamics; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen, D. The temperature of the cosmic microwave background. Astrophys. J. 2009, 707, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, J.C. Cosmic background explorer (COBE) mission. In Proceedings of the Infrared Spaceborne Remote Sensing of SPIE, San Diego, CA, USA, 11–16 July 1993; Volume 2019, pp. 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Page, L. The MAP satellite mission to map the CMB anisotropy. In Proceedings of the Symposium—International Astronomical Union; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; Volume 201, pp. 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tauber, J.; ESA; the Planck Scientific Collaboration. The Planck mission. Adv. Space Res. 2004, 34, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichiki, K. CMB foreground: A concise review. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2014, 2014, 06B109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abitbol, M.H.; Chluba, J.; Hill, J.C.; Johnson, B.R. Prospects for measuring cosmic microwave background spectral distortions in the presence of foregrounds. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 471, 1126–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommesen, H. Observing the CMB Sky with GreenPol, SPIDER and Planck. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Planck Collaboration; Akrami, Y.; Andersen, K.J.; Ashdown, M.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A.J.; Barreiro, R.B.; Bartolo, N.; Basak, S.; et al. Planck intermediate results—LVII. Joint Planck LFI and HFI data processing. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 643, A42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, L.P.L.; Eskilt, J.R.; Paradiso, S.; Thommesen, H.; Andersen, K.J.; Aurlien, R.; Banerji, R.; Basyrov, A.; Bersanelli, M.; Bertocco, S.; et al. BEYONDPLANCK—XI. Bayesian CMB analysis with sample-based end-to-end error propagation. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 675, A11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroff, M.A.; Addison, G.E.; Bennett, C.L.; Weiland, J.L. Full-sky cosmic microwave background foreground cleaning using machine learning. Astrophys. J. 2020, 903, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorkin, C.; Peiris, H.V.; Hu, W. Testable polarization predictions for models of CMB isotropy anomalies. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 77, 063008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazajian, K.N.; Adshead, P.; Ahmed, Z.; Allen, S.W.; Alonso, D.; Arnold, K.S.; Baccigalupi, C.; Bartlett, J.G.; Battaglia, N.; Benson, B.A.; et al. CMB-S4 Science Book, First Edition. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1610.02743. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1610.02743 (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Galli, S.; Benabed, K.; Bouchet, F.; Cardoso, J.F.; Elsner, F.; Hivon, E.; Mangilli, A.; Prunet, S.; Wandelt, B. CMB Polarization can constrain cosmology better than CMB temperature. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 063504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Hedman, M.M.; Zaldarriaga, M. Benchmark parameters for CMB polarization experiments. Phys. Rev. D 2003, 67, 043004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notari, A.; Quartin, M. Measuring our peculiar velocity by “pre-deboosting” the CMB. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2012, 2012, 026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, L.; Catena, R.; Masina, I.; Notari, A.; Quartin, M.; Quercellini, C. Measuring our peculiar velocity on the CMB with high-multipole off-diagonal correlations. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2011, 2011, 027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.L. Scanning and mapping strategies for cmb experiments. arXiv 1996, arXiv:9612006. [Google Scholar]

- Adachi, S.; Faúndez, M.A.; Arnold, K.; Baccigalupi, C.; Barron, D.; Beck, D.; Beckman, S.; Bianchini, F.; Boettger, D.; Borrill, J.; et al. A Measurement of the Degree-scale CMB B-mode Angular Power Spectrum with POLARBEAR. Astrophys. J. 2020, 897, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Incardona, F. Observing the Polarized Cosmic Microwave Background from the Earth: Scanning Strategy and Polarimeters Test for the LSPE/STRIP Instrument. Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, R.B. 3K: The Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation; Cambridge Astrophysics, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zonca, A.; Franceschet, C.; Battaglia, P.; Villa, F.; Mennella, A.; D’Arcangelo, O.; Silvestri, R.; Bersanelli, M.; Artal, E.; Butler, R.C.; et al. Planck-LFI radiometers’ spectral response. J. Instrum. 2009, 4, T12010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, P. Review of Detector R&D for CMB Polarisation Observations; 43rd Rencontres de Moriond: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, W.; Bock, J.J.; Ganga, K.; Hristov, V.; Hustead, L.; Koch, T.; Lange, A.E.; Paine, C.; Yun, M. Preliminary performance measurements of bolometers for the Planck high frequency instrument. In Proceedings of the Millimeter and Submillimeter Detectors for Astronomy of SPIE, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 22–28 August 2002; Volume 4855, pp. 208–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wertz, J.R.; Everett, D.F.; Puschell, J.J. Space Mission Engineering: The New SMAD; Microcosm Press: Hawthorne, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Passvogel, T.; Crone, G.; Piersanti, O.; Guillaume, B.; Tauber, J.; Reix, J.M.; Banos, T.; Rideau, P.; Collaudin, B. Planck an Overview of the Spacecraft. AIP Conf. Proc. 2010, 1218, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, D. Development of New Tools and Devices for CMB and Foreground Data Analysis and Future Experiments. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, G.; Bishop, G. An Introduction to the Kalman Filter; Technical Report; University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, M.S.; Andrews, A.P. Kalman Filtering: Theory and Practice with MATLAB; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, E.A.; Van Der Merwe, R. The unscented Kalman filter for nonlinear estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2000 Adaptive Systems for Signal Processing, Communications, and Control Symposium (Cat. No. 00EX373), Lake Louise, AL, Canada, 1–4 October 2000; pp. 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Julier, S.J.; Uhlmann, J.K. New extension of the Kalman filter to nonlinear systems. In Proceedings of the Signal Processing, Sensor Fusion, and Target Recognition VI of SPIE, Orlando, FL, USA, 21–25 April 1997; Volume 3068, pp. 182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, M.L.; Bayle, J.B.; Chua, A.J.; Vallisneri, M. Assessing the data-analysis impact of LISA orbit approximations using a GPU-accelerated response model. Phys. Rev. D 2022, 106, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Gui, M.; Fang, J.; Liu, G. Differential X-ray pulsar aided celestial navigation for Mars exploration. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 62, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Gui, M.; Fang, J.; Liu, G.; Dai, Y. A novel differential Doppler measurement-aided autonomous celestial navigation method for spacecraft during approach phase. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2017, 53, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J. A novel autonomous celestial integrated navigation for deep space exploration based on angle and stellar spectra shift velocity measurement. Sensors 2019, 19, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgini, J.D. Status of the JPL Horizons Ephemeris system. In Proceedings of the IAU General Assembly, Honolulu, HI, USA, 3–14 August 2015; Volume 29, p. 2256293. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).