Abstract

Metric temporal logic (MTL) is a popular real-time extension of linear temporal logic (LTL). This paper presents a new simple SAT-based bounded model-checking (SAT-BMC) method for MTL interpreted over discrete infinite timed models generated by discrete timed automata with digital clocks. We show a new translation of the existential part of MTL to the existential part of linear temporal logic with a new set of atomic propositions and present the details of the new translation. We compare the new method’s advantages to the old method based on a translation of the hard reset LTL (HLTL). Our method does not need new clocks or new transitions. It uses only one path and requires a smaller number of propositional variables and clauses than the HLTL-based method. We also implemented the new method, and as a case study, we applied the technique to analyze several systems. We support the theoretical description with the experimental results demonstrating the method’s efficiency.

1. Introduction

This paper is a full version of the extended abstract published in informal proceedings of the 25th International Workshop on Concurrency, Specification and Programming [1]. Improvements and extensions compared to that paper are listed in Appendix A.

There are many ways to check the model. Hardware- and software-based systems are increasingly used in safety-critical situations to control and connect physical systems, e.g., simple cardiac pacemakers or very complex space rockets. The complexity and criticality of systems also increase the need for effective verification techniques.

The specification language and the system model usually depend on the type of property we want to verify. Suppose we want to verify the discrete-time execution properties of a system. In that case, discrete-time logic may be the correct specification choice, and the system may best be represented as a discrete timed automaton.

Integrating specialized components is fundamental to many embedded engineering projects. The behavior of these components is often specified in informal timing diagrams that engineers interpret during interface hardware and software design [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The timed automata are one of the models that enable the formal modeling of those components.

Timed automata (TA) [8] are finite-state automata augmented with a finite set of variables called clocks. The clocks are used to measure the elapsed time. Timed automata are very convenient for modeling and reasoning about timed systems: they combine a powerful formalism with advanced expressiveness and efficient algorithmic and tool support. The timed automata formalism is applied to the analysis of software and asynchronous circuits [9] and real-time control programs [10].

The model-checking technique is widely used in sensor verification [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The sensor networks are modeled, e.g., by the network of timed automata, and their properties are specified in terms of temporal logic.

One of the most famous frameworks in the specification and verification of computer systems is temporal logic. There are many types of temporal logic to express the requirements of the systems: computation tree logic (CTL) [11], soft real-time CTL (RTCTL) [12], linear temporal logic (LTL) [13], and metric temporal logic (MTL) [14].

Linear temporal logic (LTL) allows expressing properties about each execution of a system, such as the fact that any occurrence of a problem eventually triggers the alarm. Metric temporal logic (MTL) extends LTL by constraining the temporal operators with time intervals. It was introduced by Koymans [14] in 1990 and has appeared as a real-time specification formalism. MTL has two main semantics: “continuous” and “pointwise” [15,16,17,18]. The pointwise semantics is based on timed words, the widespread interpretation for systems modeled as timed automata [8]. Both semantics have been extensively studied [15,16,17,18]. MTL allows expressing, for example, that any occurrence of a problem in a system will trigger the alarm within at most five units of time. Here, we consider MTL with pointwise semantics interpreted over linear discrete infinite digital-clock models [19] generated by timed automata with integer time.

Bounded model checking [20,21,22] (BMC) is one of the symbolic model-checking techniques designed for finding witnesses for existential properties or counterexamples for universal properties. Its main idea is to consider a model reduced to a specific depth. The method works by mapping a BMC problem to the satisfiability problem (SAT). The MTL satisfiability and model-checking problems are undecidable over interval-based semantics [23]. It has led to various restrictions being considered on MTL to recover decidability [24,25].

We provide a new, efficient method of the bounded model-checking technique for metric temporal logic properties of timed automata with digital clocks, which can be successfully used to verify sensor networks.

Developing new model-checking techniques for a network of automata is an essential research direction. It is due to the fact that timed automata are used to verify the modes of, often, life-critical time systems. Systems and their properties are becoming more and more complex. It results in developing model-checking methods that will work faster than the older methods. To be successfully applied, these methods should be faster than the old ones and use as little memory as possible. However, they should also be easy to implement and understand so that everything is evident at the design stage of such a method. For such a reason, in this paper, we developed a completely new and much faster method of bounded model checking than the one presented in [26].

The main contributions of the paper are as follows:

- Defining the translation of the existential model-checking problem for MTL to the existential model-checking problem for linear temporal logic with additional propositional variables (this logic is denoted by );

- Clarification of the steps of the new method;

- Proving the correctness of the above translation;

- Defining bounded semantics for ;

- Defining the BMC algorithm;

- Implementing the new method;

- A detailed experimental evaluation of the old and the new methods on two earlier presented benchmarks: a timed generic pipeline paradigm (TGPP) and a timed train controller system (TTCS),

- Modeling a dining philosophers problem with time as the timed dining philosophers problem (TDPP);

- A detailed experimental evaluation of the old and the new methods on TDPP.

In this paper, we used the weakly monotonic semantics [27] for timed automata with digital clocks [19,27]. The main steps of our new method for MTL and TA with discrete time can be described as follows: first, the infinite timed model is reduced to a finite model. Next, the MTL formulae are translated to formulae [1], and eventually, since the interval modalities in MTL appear as literals in the formula, existential properties are reduced to a satisfiability problem (SAT). Our method’s main advantages are that the translation from MTL to requires neither new clocks nor new transitions. Moreover, our BMC method needs only one path, whereas the BMC method from [26] needs many paths depending on a given formula . Thus, one may expect that our method is much more effective since the intuition is that an encoding that results in fewer variables and clauses is usually easier to solve.

We evaluate the BMC method using a timed generic pipeline paradigm (TGPP), a timed train controller system (TTCS), and the timed dining philosophers problem (TDPP), which we model by a network of discrete timed automata and compare with the corresponding method [26].

Related Work

Timed automata were introduced in the early 1990s by Alur and Dill [8] to model real-time systems. Timed automata cause the specification and verification of models of real-time systems to be easier. The two primary semantics are discussed in the literature: the discrete-time and dense-time semantics [8]. However, the dense-time semantics is more natural from a real-life point of view. It allows us to model real-time systems easily.

Our choice of time domain is , the set of natural numbers. In our method, the key property of the time domain is its discreteness, which implies that a finite amount of events can happen at different times in any interval of nonzero length. There are many methods for verifying real-time systems using discrete-time models [12,28,29,30,31]. Authors of [19] established that the timed reachability problem has the same answer, irrespective of the choice between and under certain restrictions.

The other formalisms for discrete time modeling apart from discrete timed automata were presented, such as durational transition graphs (DTG [32]) and embedded system modeling language (EMLAN [33]).

Discrete time models were also widely used for modeling systems’ behaviors [34,35,36,37,38].

MTL has been widely discussed in the literature. Checking properties expressed in MTL in timed automata is still an actual research topic [39,40,41,42,43,44]. In [45], the authors took into account MTL over the . They also used the pointwise semantics over the and considered two semantic variants: the non-strict and strict semantics. They devised two translations from MTL to LTL:

- The time difference translation for strict semantics, where new propositional variables encode time differences between states (the time difference translation is similar to the method presented in [1]).

- The gap translation for the strict semantics uses a new propositional variable, called gap, to encode the jumps between states. The gap is intended to be true in LTL states corresponding to unmapped time points in MTL models. The main idea for their translation is to map each timed state sequence into a state sequence. Both LTL translations are exponential in the size of the MTL input formula due to the binary encoding of the numbers in the intervals.

In [26], the authors investigated a SAT-based BMC method for MTL that is also interpreted over linear discrete infinite time models generated by discrete timed automata. They translated the existential model-checking problem for MTL into the existential model-checking problem for a variant of linear temporal logic (called HLTL). They also provided a SAT-based BMC technique for HLTL. The presented translation requires as many new clocks as there are intervals in a given formula. It also requires adding exponential resetting transitions and many paths that depend on a given MTL formula. The complexity of the satisfiability and model-checking problems for fragments of MTL concerning different semantic models were studied in [46] and in [15]. MTL expressiveness was extensively discussed in [17,47,48]. The BMC problem for MTL properties of timed automata with the dense time was discussed in [49]. However, experimental results have shown that this is not feasible.

Additionally, other types of logic were used for the specification of discrete-time systems, such as QsCTL [29], which extends CTL [11] with quantitative bounded temporal operators and is a variant of RTCTL [11], discrete-time CTL [33], and HyperLTL [50], which is a temporal logic for hyper-properties, which allows reasoning about multiple execution paths simultaneously.

2. Discrete Timed Automata and MTL

In this paper, we used the weakly monotonic semantics [27] for timed automata with digital clocks [19,27]. The paper [19] shows that bounded invariance MTL properties and bounded-response MTL properties are digitizable. That is why we consider timed automata with digital clocks.

The formalism of timed automata was defined in [8] by Alur and Dill for representing systems with real-time constraints. A timed automaton is a finite automaton which manipulates finitely many variables called clocks.

2.1. Discrete Timed Automata

Let be the set of natural numbers, and . We assume a finite set of variables, called clocks. Each clock is a variable ranging over . A clock valuation is a total function that assigns to each clock x a non-negative integer value . The set of all the clock valuations is denoted by . For , the valuation is defined as , and , . By , we denote a delay of time units. For , denotes the valuation such that ; let , , and . The set of clock constraints over the set of clocks is defined by the abstract grammar:

Definition 1.

A discrete timed automaton (DTA for short) is a tuple

- is a finite set of actions,

- is a finite set of locations,

- is the initial location,

- is a finite set of clocks,

- is a transition relation,

- is a state invariant function,

- is a set of atomic propositions, and

- is a valuation function assigning to each location a set of atomic propositions true in this location.

Each , denoted by , represents a transition from ℓ to on the action σ. is the set of the clocks to be reset upon this transition, and is the enabling condition for t.

2.2. Product of a Network of Discrete Timed Automata

A network of discrete timed automata can be composed into a global (product) discrete timed automaton [51] in the following way. The transitions of the discrete timed automata that do not correspond to a shared action are interleaved, whereas the transitions labeled with a shared action, are synchronized.

Let , be a non-empty and finite set of indices, be a family of discrete timed automata such that and for . Moreover, let . The parallel compositioni of the family of discrete timed automata is the discrete timed automaton = such that:

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

and a transition is defined as follows:

2.3. Concrete Model

The semantics of the DTA is defined by associating with it a transition system, which we call a concrete model.

Definition 2.

Let be a DTA, and a clock valuation such that , .

The concrete model for is a tuple

- is the set of the concrete states.

- is the initial state.

- A valuation function is defined as for each state is a transition relation on Q defined by action and time transitions as follows.

- For and :

- 1.

- Action transition: if there is a transition such that and and ,

- 2.

- Time transition: iff and .

Let us observe that for the considered set of clock constraints , the condition of the time transition can be replaced by a simpler one. Namely, and .

A path in is an infinite sequence of concrete states such that for all , for some . Such a definition of the path permits two consecutive actions to be performed one after the other, i.e., no time has to elapse between two consecutive actions. It means that we are dealing with the point-based weakly monotonic integer-time semantics.

From now on, for a path , by , we denote the state .

2.4. MTL Logic

MTL [14,15] (metric LTL) is the extension of LTL in which temporal operators are replaced by its time-constrained versions. MTL can express many time constraints. For example, we can express a system property: if a system is in the state q, then it will be in the state exactly 3 time units later.

2.4.1. Syntax

We begin with some preliminary definitions. Let be an atomic proposition and the set of all the intervals in of the form or , where and , and let . Observe that we do not exclude one-element intervals since can be expressed as . The MTL logic in positive normal form is defined in the following way:

The operators and are called bounded until and bounded always, respectively, and they are read as “until in the interval ” and “always in the interval ”. The operator is defined in the standard way: .

2.4.2. Semantics

There are two possible semantics for metric temporal logic: the “pointwise” semantics and the “continuous” semantics [15]. In the pointwise approach, temporal assertions are interpreted only at time points where the action happens in the observed timed behavior of a system. In the continuous one, it is allowed to assert formulae at arbitrary time points between actions as well. In the presented method, we use the pointwise semantics.

Let be a DTA, and the concrete model for . For a path , let , i.e is a set of indices of time transitions. Now, we define a function such that, for all , . For all , the function returns the value of the global time (called “duration” in [15]).

Here and in what follows, we use the convention to omit the model from expressions with ⊨ for the sake of brevity.

Definition 3.

Let α and β be MTL formulae. The satisfaction relation , which defines truth of an MTL formula in the concrete model along a path ρ starting at position , is defined inductively:

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

For simplicity of notation, we write instead of . Therefore, we shall write for . An MTL formula is existentially valid in the model , which is denoted as , if and only if for some path starting in the initial state of . Determining whether an MTL formula is existentially valid in a given model is called the existential model-checking problem.

3. Bounded Model Checking

The verification method presented in this paper is based on the translation of MTL formula to formula. We extend a standard logic by adding an extra set of propositional variables. We compare our new method with the corresponding method presented in [26].

3.1. The Translation

The set of all the clock valuations is infinite, which means that the model has an infinite set of states. We need to abstract the proposed model before we can apply the BMC technique.

3.1.1. Abstract Model

Let be a discrete timed automaton with . For each , let be the largest constant appearing in any clock constraint involving clock and used in the state invariants and guards of . Two clock valuations v and in are equivalent, which is denoted by , if and only if for each either and or and and .

It is easy to see that the relation ≃ is an equivalence relation, which enables us to construct a finite abstract model.

To this end, we define the set of possible values of clock in the abstract model as for . Moreover, for two clock valuations v and in , we say that is the time successor of v (denoted ) as follows: for each ,

Definition 4.

Let be a discrete timed automaton. The abstract model for is a tuple

- is the set of abstract states;

- is the initial state;

- is a valuation function such that for all , if and only if ;

- , where is a transition relation defined by the time and action transitions.

- −

- The time transition is defined as if and only if , and .

- −

- The action transition is defined as follows: for any , if and only if there exists a transition such that , and .

Definition 5.

Apathin the abstract model is a sequence of states such that for each , either or , for some action .

For a given path , denotes the j-th state of the path , denotes the j-th prefix of the path ending with . Given a path one can define a function such that, for each , is equal to the number of time transitions on the prefix .

Definition 6.

Let be the concrete model for and the abstract model for . We say that a state in the concrete model , and a state in the abstract model areequivalent, which is denoted by , if and only if and .

It is well-known [52] that the relation ≅ is weak-time-bisimulation equivalent between the concrete model and the abstract model. The reason is that one can replace one -value time transition in the concrete model by individual transitions in the abstract model, whereas individual transitions in the abstract model can be replaced by one -value time transition in the concrete model.

3.1.2. MTL Semantics in the Abstract Model

Definition 7.

The satisfiability relation , which defines the truth of an MTL formula in the abstract model along the abstract path π with the starting point m at the depth , is inductively defined as follows:

- ,

- ,

- iff ,

- iff ,

- and ,

- or ,

- ,

- iff implies .

In the above definition, m does not play itself a part in the satisfaction relation. However, this notation is helpful for Definition 8.

Theorem 1

(The equivalence of the semantics in the concrete and abstract models). Let be the abstract model for the discrete timed automaton and the concrete model for . Then, for each MTL formula φ, the following equivalence holds: .

Proof.

The proof of Theorem 1 follows from the definition of the satisfiability relation and the weak-timed-bisimulation equivalence of the models and . □

3.1.3. Logic

Let be the set of all intervals and a set of the new propositional variables. An formula in the negation normal form is defined by the following grammar:

Definition 8.

The satisfaction relation , which defines the truth of an formula in the abstract model along the abstract path π at the position m, at depth is inductively defined as follows:

- ,

- ,

- iff ,

- iff ,

- iff ,

- iff ,

- iff and ,

- iff or ,

- iff and ,

- iff .

An formula is existentially valid in the abstract model , denoted as , if and only if on some path starting in the initial state of .

3.1.4. The Translation from MTL to

Two translations from MTL to were described in [45]. However, in the first translation, the new propositional variables encode time differences between states, and in the second translation a new propositional variable called gap encodes the jumps between states. In the translation presented below, we use global time approach [1]. However, in [1] the strongly monotonic semantics was used.

Definition 9.

Let , and α, β a MTL formulae. The translation from MTL to is defined as a function by the following equations:

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- , and

- = .

The translation of the operator follows from its definition in terms of the operator. Observe that the translation of literals, as well as logical connectives, is straightforward. The translation of the operator ensures that the formula holds at some point in the interval (it is expressed by the requirement ) and holds everywhere before holds. Similarly, the translation of the operator ensures that holds at every point in the interval (it is expressed by the requirement ).

The translation from EMTL to E is more straightforward than the one presented in [48], e.g., TPTL expressiveness is higher than . In our case, we do not need this extension of the logic to solve the given problem.

Theorem 2.

Let be a discrete timed automaton, φ an MTL formula, and the abstract model for . Then if, and only if .

4. Proof of the Theorem 2

A proof of the Theorem 2 follows directly from the Lemmas 1 and 2.

Lemma 1.

Let be a discrete timed automaton, φ an MTL formula, an abstract model for discrete timed automaton , and π an abstract path in the abstract model . If , then .

Proof.

We proceed by induction on the length of a given formula.

Assume that . Consider the following cases:

- . Because , it is obvious that . Therefore, .

- , where . Thus, . Therefore, .

- . From the definition of the satisfiability relation (Definition 7) it follows that and . By inductive hypothesis, we obtain and . Therefore, , and hence .

- . From the definition of the satisfiability relation (Definition 7) it follows that or . By inductive hypothesis, we obtain that or . Therefore, , and hence .

- . Assume that . From the definition of the satisfiability relation (Definition 7), it follows that and and , for some . By inductive hypothesis, we obtain and , for some and , for all . Therefore, , for some , and , for all . Therefore, we conclude that .

- . Assume that . From the definition of the satisfiability relation (Definition 7), it follows that implies , which means that , for all . By inductive hypothesis, we obtain , for all . Hence, , for all . From the semantics of , it follows that . So, we can conclude that .

□

Lemma 2.

Let be a discrete timed automaton, φ an MTL formula, an abstract model for the discrete timed automaton , and π an abstract path in the abstract model . If , then .

Proof.

We proceed by induction on the length of a given formula.

- . Since , it follows that . Therefore, .

- , where . Then . Therefore, .

- . Thus, . From the definition of the satisfiability relation (Definiton 8) it follows that and . By inductive hypothesis, we obtain and . Hence, and thus .

- . Then . From the definition of the satisfiability relation (Definition 8) it follows that or . By inductive hypothesis, we obtain or . Hence, , and thus .

- . Assume that . From the definition of the translation, it follows that . From the definition of the satisfiability relation 8, it follows that and , for some . Therefore, and , for some . From the inductive hypothesis, we obtain and , thus and . Thus, we conclude that .

- . Assume that . From the definition of the translation, it follows that . From the definition of the satisfiability relation or , which means or , for all . By inductive hypothesis, we obtain or , which is equivalent to . Therefore, .

□

Proof of Theorem 2.

(⟹) Assume that . Therefore, , for some abstract path in such that . It means that . From Lemma 1, it follows that . Therefore, , for . Thus .

(⟸) Assume that . Hence, , for some abstract path in such that . It means that . From Lemma 2, it follows that . Therefore, , for . Thus . □

4.1. Bounded Semantics

To define the bounded semantics, we need to represent infinite paths in the abstract model using k-paths and loops [20,21].

Definition 10.

Let be an abstract model, and . A k-path is a pair , which is also denoted as , where π is a finite sequence of the abstract states such that for each , either or , for some . Moreover, every action transition is preceded by at least one time transition. A k-path is a loop, written as for short, if and .

If a k-path is a loop, it represents the infinite path of the form , where and . We denote this unique path by . Note that for each , .

Given a path , one can define a function such that for each , is equal to the number of time transitions on the prefix . Note that for each , gives the value of the global time in the j-th state.

In the definition of bounded semantics for variables from , one needs to use only a finite prefix of the sequence . Namely, for a k-path that is not a loop, the prefix of the length k is needed, and for a k-path that is a loop, the prefix of the length is needed.

Definition 11

(Bounded semantics). Let be the abstract model, a k-path in , , and . The relation is defined inductively as follows:

The proof of Lemma 3 below is based on induction on the length of the given formula. It is analogous to the proof of Lemma 7 from the paper [20].

Lemma 3.

Let be a discrete timed automaton, φ an formula, and the abstract model for the automaton . For each formula φ, each path in , each and each , if , there exists a path such that and and or and .

The proof of the Lemma 4 below is based on the well-known fact that if the LTL formula is true on some infinite path, it is also true on an infinite path of the form , where u and v are finite sequences of states [20].

Lemma 4.

Let be a discrete timed automaton, φ an formula, the abstract model for the automaton , π a path in the abstract model, and . For each formula φ, each and each , if , there exists a path such that .

An formula existentially k-holds in the model , written as , if and only if for some path starting at the initial state.

Theorem 3 shows that for some specific bound, bounded and unbounded semantics are equivalent. The proof of Theorem 3 follows directly from Lemmas 3 and 4.

Theorem 3.

Let be the abstract model and φ an formula. Then, if and only if there exists a such that .

Example 1.

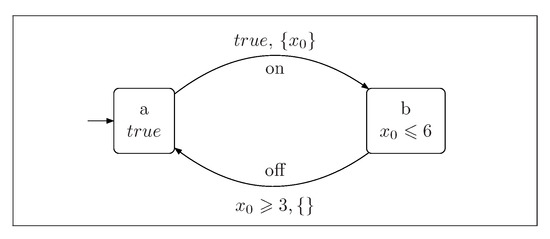

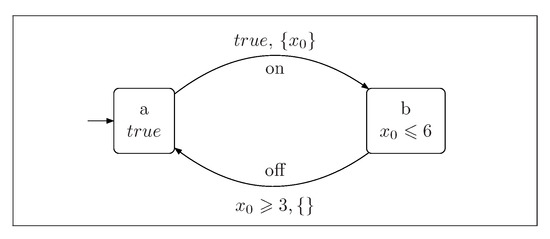

Figure 1 shows an automaton modeling a simple light switch. It consists of two locations, and b. When the action is performed, the clock is reset. The automaton can stay in the location b until the valuation of the clock is less or equal to 6. The transition from location b to location a (action off) can be performed when the valuation of the clock is greater than 3.

Figure 1.

The simple light switch.

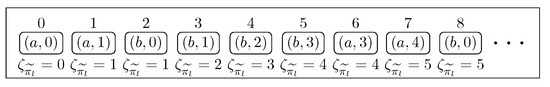

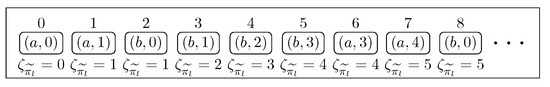

Figure 2 shows an abstract path in the abstract model for the simple light switch. Under the states, we show the global time at the given position.

Figure 2.

An example of the path.

Example 2.

Let us check the satisfiability of formula for the case when is not a loop. Let , , and .

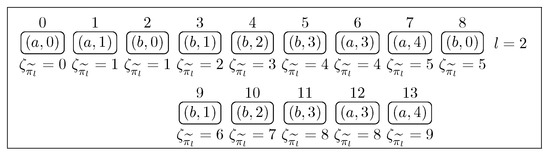

Figure 3 shows an example of the path, which is a loop. Note that for and , , and . Under the states, we show the global time in the given state.

Figure 3.

An example of the k-path, which is a loop.

Example 3.

Let us check the satisfiability of formula for the case when is a loop and . Let , , , and .

Example 4.

Let us check the satisfiability of the formula for the case when is a loop and . Let , , , and .

4.2. Translation to SAT

The last step of our method is the standard one ([26,53]). It consists in encoding the transition relation of and the formula . The only novelty lies in the encoding of the finite prefix of the sequence .

Let be the abstract model for the automaton , be the formula, and a bound. The formula encodes a bounded semantics of the formula . It is defined over the same set of the propositional variables as the propositional formula .

The definition of the formula assumes that, states and actions in the abstract model , and passage of time are encoded symbolically. This is possible if the set of states and the set of actions are finite. Formally, each symbolic abstract state is represented by a vector, of propositional variables, where the length r depends on the number of states in the abstract model. This vector is called a symbolic state. Each action is represented by a vector of propositional variables, where the length t depends on number of local actions in . It is called a symbolic action.

A pair consisting of a sequence of the symbolic transitions and a symbolic number is called a symbolic k-path. Let be a pair which represents a symbolic k-path: , where is a symbolic state, for , and is a symbolic number, which is a vector of propositional variables with . Moreover, let , for , be a symbolic action.

Let and be two different symbolic states, a symbolic action and a symbolic number. To define the formula , we use the following auxiliary propositional formulae: encodes a state in the abstract model , encodes the equality of two global states, encodes an action transition in , encodes a time transition in , , for encodes the relation ∼ between j and , and encodes the existence of a loop for path at position l.

The propositional formula , encodes the unfolding of the transition relation of the abstract model to the depth k in the following way:

The next step of the method is the translation of the formula into the propositional formula . To translate the formula to SAT problem, we use the auxiliary propositional formulae defined in [53] and the propositional formula . The formula encodes the condition that says that the difference of the symbolic global time at the depth d and in the starting point m on the symbolic path belongs to the interval .

Definition 12

(The translation from to SAT). Let be the abstract model, an formula, and a bound. The translation of the formula on the path starting at point m at the depth d is defined inductively:

Theorem 4.

Let be the abstract model. Then for every , at the depth , if, and only if, the propositional formula is satisfiable.

The proof of the above theorem is analogous to the proofs presented in [26,53].

5. Experimental Results

In this section, we experimentally evaluate the performance of our new translation (We performed our experimental results on a computer equipped with I7-3770 processor, 32 GB of RAM, and the operating system Arch Linux. All the benchmarks together with instructions on how to reproduce our experimental results can be found at the web page https://tinyurl.com/satbmc4dtta-emtl, accessed on 3 November 2022). Our SAT-based BMC algorithm is implemented as a standalone program written in the programming language C++. We compared the new method with the corresponding one from [26]. For both methods, we used the state-of-the-art Kissat SAT solver [54]. We conducted the experiments using the slightly modified TGPP [26], the TTCS [26], and TDPP, and we compared our result with the results generated using the implementation from [26].

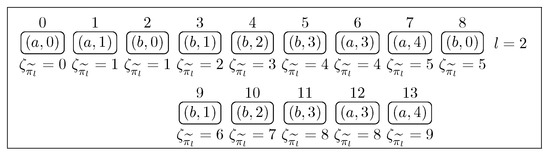

5.1. Timed Dining Philosophers

As the first benchmark, we used the well-known dining philosophers problem [55], and we extended it using clocks. The system consists of n discrete timed automata, each of which models a philosopher, together with n automata, each of which models a fork, together with one automaton which models the lackey. The latter automaton is used to coordinate the philosophers’ access to the dining room. In fact, this automaton ensures that no deadlock is possible. The global system is obtained as the parallel composition of the components, which are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The TDPP system.

We assume that one unit of time represents 30 min. A philosopher has to think at least 30 min (1 time unit, ) and at most 2 h and 30 min (5 time units ). He also has to eat for, at most, one hour (2 time units, ), but he also can finish eating earlier ().

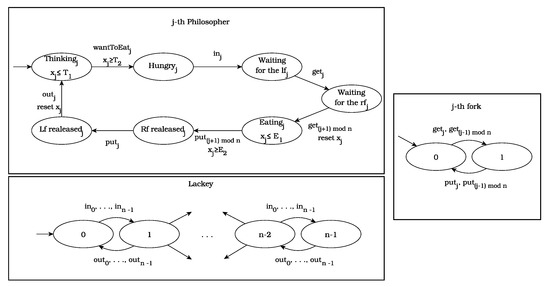

Let us consider the following formulae:

- . At least one philosopher will eventually eat and put down both forks.

- . Eventually, every second philosopher (starting with the first one) eats.

- . Every second philosopher (starting with the first one) always eats in the end.

All these formulae are existentially valid in the model of TDPP.

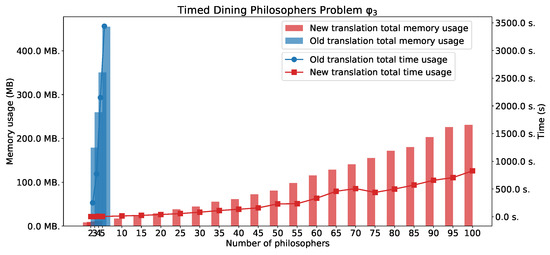

Figure 5 shows experimental results for and . For the simple eventually formula we can observe that time usage for the method based on the old translation is better than for the method based on the new one. However there is a noticeable difference in memory usage. In this case, the new method is better. For the formulae and , we can see the advantages of the new method.

Figure 5.

TDPP with n philosophers: and .

Figure 6 shows experimental results for .

Figure 6.

The TDPP with n philosophers: .

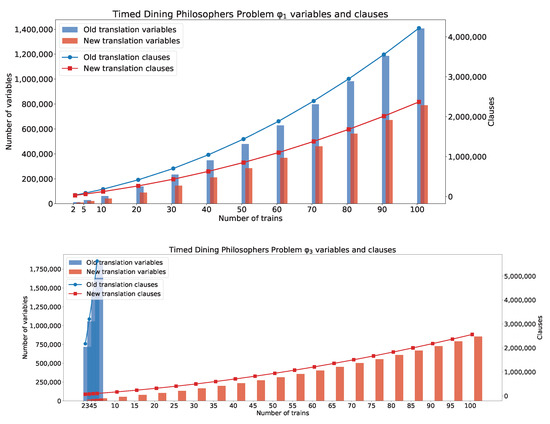

Figure 7 shows generated clauses and variables for and .

Figure 7.

The TDPP with n philosophers clauses and variables: and .

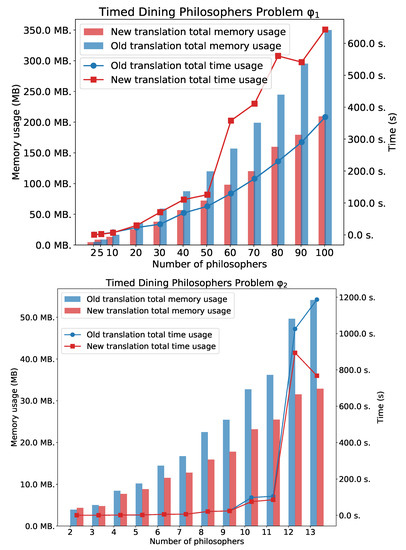

5.2. Timed Generic Pipeline Paradigm

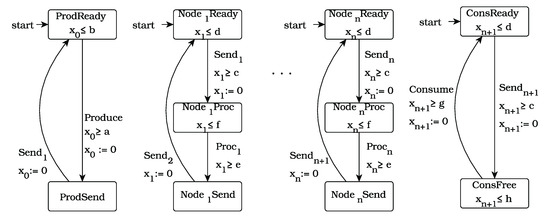

The TGPP (Figure 8) discrete timed automata model [26] consists of a producer producing data within the time interval () or being inactive, a consumer receiving data within the time interval () or being inactive within the time interval (), and a chain of n intermediate nodes which can be ready for receiving data within the time interval (), processing data within the time interval () or sending data. We assume that and , where n represents number of nodes in the TGPP.

Figure 8.

The TGPP system.

To compare our experimental results with [26], we tested the TGPP discrete timed automata model on the following MTL formulae that existentially hold in the model of TGPP (n is the number of nodes). In the below formulae, we use , , , and for , , , and respectively. Moreover, we write for . Let us consider the following formulae:

- . It states that always either the producer has sent the data or the consumer has received the data.

- . It states that eventually in time less then , it is always the case that the producer is ready to send the data or the consumer has received the data.

- . It states that the Consumer infinitely often eventually receives the data in time less than units.

All these formulae are existentially valid in the model of TGPP.

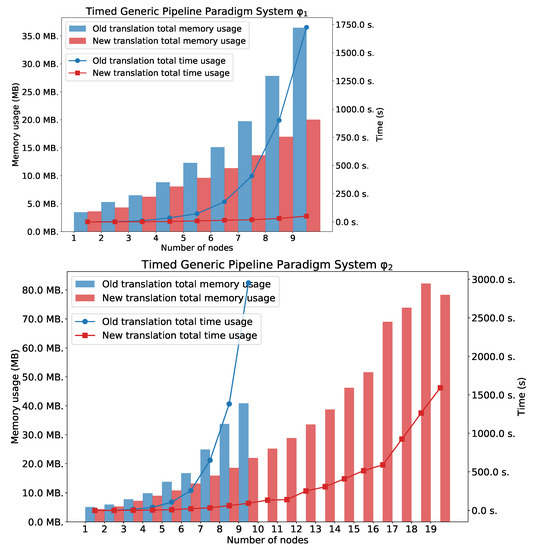

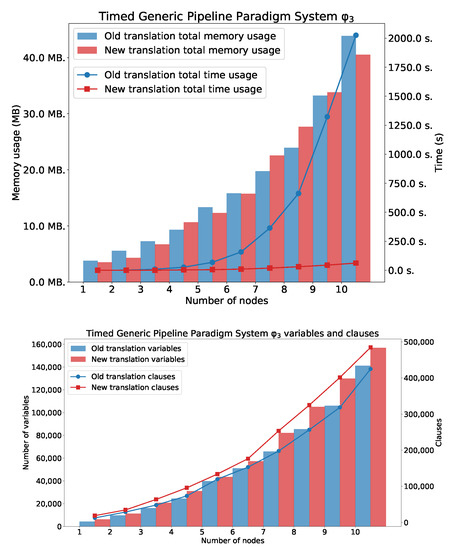

Charts in Figure 9 show the total time usage and total memory usage for TGPP needed for verification and . In both cases, the new method outperforms the old one. For , the -based method was able to verify the system with 19 nodes, and the HLTL-based method was able to verify the system only with 9 nodes. For , the memory usage is similar in both cases. However, the time usage for the old method exponentially grows. The second plot shows the number of generated clauses and variables.

Figure 9.

and : TGPP with n nodes.

Charts in Figure 10 shows the total time usage and total memory usage for TGPP needed for verification . The second plot shows the number of generated clauses and variables.

Figure 10.

Results for : TGPP with n nodes. Number of variables and clauses for .

5.3. Timed Train Controller System

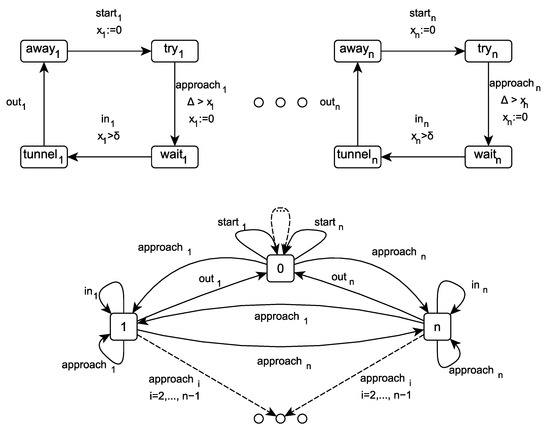

The TTCS (Figure 11) consists of n (for ) trains , each one using its own circular track for traveling in one direction and containing its own clock , together with controller C used to coordinate the access of trains to the tunnel through which all trains have to pass at a certain point. There is only one track in the tunnel, so trains arriving from each direction cannot use it in the same time. There are signals on both sides of the tunnel, which can be either red or green. All trains notify the controller when they request entry to the tunnel or when they leave the tunnel. The controller controls the color of the displayed signal, and the behavior of the scenario depends on the values and ( makes it incorrect—the mutual exclusion does not hold).

Figure 11.

The TTCS system.

Controller C has locations, with the location 0 being the initial one. The action of train denotes the passage from the location away to the location where the train wishes to obtain access to the tunnel. This is allowed only if controller C is in location 0. Similarly, train synchronizes with controller C on action , which denotes setting C to location , as well as , which denotes setting C to location 0. Finally, action denotes the entering of train into the tunnel.

Moreover, we assume the following set of propositional variables: .

Let us consider the following formulae:

- . It expresses that the system violates the mutual exclusion property.

- . It expresses that the first train can infinitely often and from any state enter the tunnel in time less than .

- . It expresses that the first train is infinitely often in the tunnel and outside the tunnel in time less than .

All these formulae are existentially valid in the model of TTCS.

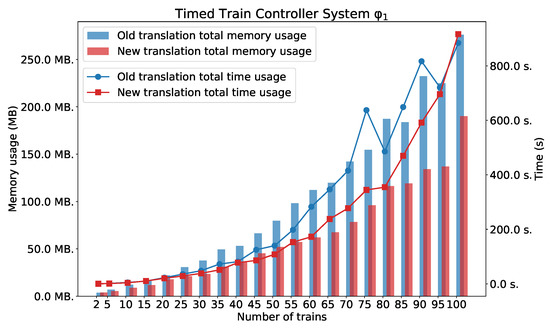

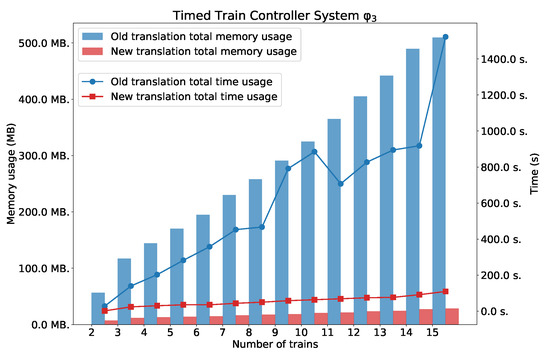

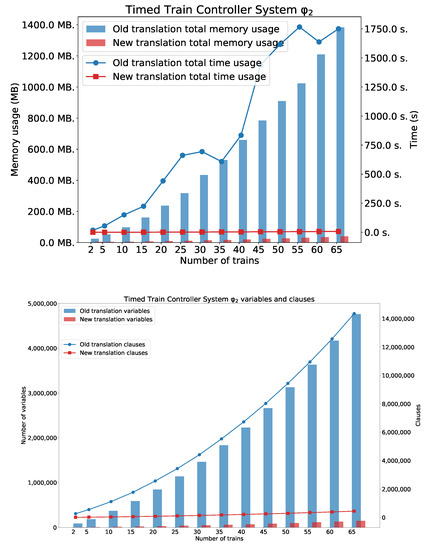

As we can see in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, the new method surpasses the old one. As we expected, the difference between the two methods is smaller for the simple formula that expresses reachability problem (). However, a significant difference can be seen for the formulae and . Figure 14 also shows the number of clauses and variables for the new and the old method. As we can see, the numbers of variables and clauses grow exponentially for the old method.

Figure 12.

: TTCS with n trains.

Figure 13.

: TTCS with n trains.

Figure 14.

Results for . Number of variables and clauses for and TTCS with n trains.

6. Statistics

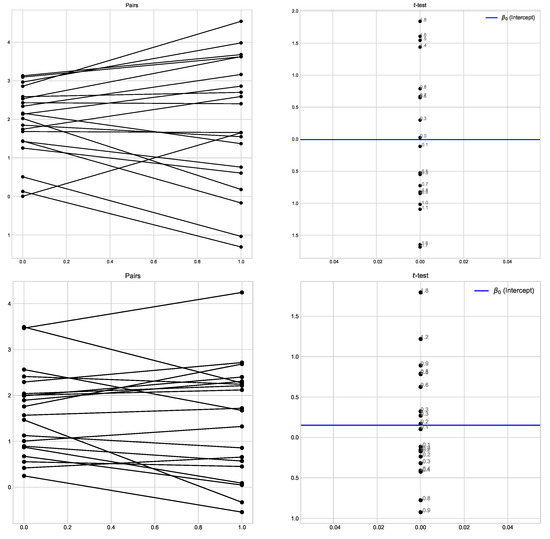

We performed one- and two-sided Wicoxon tests for DPTT (Figure 15). Tests showed that the new method outperforms the old one: the new method used less time (), and used less memory ().

Figure 15.

TDPP: Pairs Wilcoxon plots for total time usage and total memory usage for , , and .

We performed the two-sided and one-sided Wilcoxon tests for all the experiments. As a dataset, we took the whole set of the experimental results (note that we deleted some results in the figures in Section 5 to make them clear—whole data can be found in the .tar.xz file we delivered).

7. Conclusions

In this work, we proposed a new SAT-based BMC for soft real-time systems modeled by discrete time automata with digital clocks and for properties expressible in metric temporal logic with semantics over discrete time automata with digital clocks.

The first step of this method is translating the existential model-checking problem for MTL into the existential model-checking problem for logic by replacing temporal operators with intervals (MTL) with temporal operators and new propositional variables corresponding to these intervals (). The second step is translating the existential model-checking problem for into the satisfiability problem for the propositional formulae. The efficiency of the new method is due to the fact that only one additional clock for measuring global time is needed, unlike the earlier method [26], which translates the existential model-checking problem for MTL into the existential model-checking problem translation to HLTL.

The earlier method [26] needs to add to a timed automaton one extra clock, one extra path, and an extra transition for each occurrence of the temporal operator in the formula.

We implemented our method as a standalone program written in the programming language C++. This implementation allowed us to experimentally evaluate and compare the new approach with the old one.

The experimental results show that our approach is significantly better than the approach based on translation to HLTL. The new method substantially reduces the conjunction normal form (CNF) formula’s size, an input formula for the SAT solver. The reduced size of the CNF formula causes the SAT solver to use much less time and memory to determine the satisfiability of the input formula.

In future work, we plan to extend our method by adding discrete data [56]. We also would like to improve and develop and prove the method presented in [49].

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.M.Z. and A.Z.; methodology, A.M.Z. and A.Z.; software, A.Z.; validation, A.M.Z.; formal analysis, A.M.Z.; proving, A.M.Z.; investigation, A.M.Z. and A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.M.Z. and A.Z.; visualisations, A.M.Z.; supervision, A.Z.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MTL | Metric Temporal Logic |

| HLTL | Hard Reset LTL |

| LTL | Linear Temporal Logic |

| TA | Timed Automata |

| DTA | Discrete Timed Automaton |

| BMC | Bounded Model Checking |

| Linear Temporal Logic with Additional Propositional Variables | |

| TGPP | Timed Generic Pipeline Paradigm |

| TTCS | Timed Train Controller System |

| TDPP | Timed Dining Philosophers Problem |

Appendix A. Improvements and Extensions Compared to the Workshop Paper

- We improved it and proved the main theorem. The workshop paper presented only the idea of the method;

- We improved definitions;

- We changed the semantics: the weakly monotonic semantics seems to be more natural in the case of discrete time. In [1], we used strongly monotonic semantics;

- We redefined the concrete model. The process of creating the concrete model presented in [26] was unnecessarily complicated;

- We redefined the semantics of MTL;

- We showed the translation to SAT for the formula on the path starting at point m at the depth d;

- We extended the experimental section by adding the timed dining philosophers problem (to the best of our knowledge, we modeled TDP for the first time as a network of discrete timed automata—we could find only the modeling using timed Petri nets in the literature).

Appendix B. Code Reproducibility

Appendix B.1. Preliminary

This code was successfully tested on the Linux operating system. Requirements for running the benchmarks: a reasonably modern 64-bit Linux environment with Python 3 installed. As all the programs in our package are statically linked, they do not rely on the particular version of libraries available on the final system.

In order to run the code of the experiments, one needs to download the supplementary material (.tar.xz file attached from https://tinyurl.com/bmc4dtta-mtl, accessed on 3 November 2022) and unpack it:

Once unpacked, one should go to the directory named

that contains the code necessary to replicate all the experiments:

Appendix B.2. Running Experiments

To launch a SAT-based BMC for DTTA and experiment, go to the

directory, where {FORMULA_NR} is a natural number , and {SYSTEM_ACRONYM} is either ‘ttcs’, ‘tgpp’ or ‘tdpl’, and run the bash file all-new-{SYSTEM_ACRONYM}-f{FORMULA_NR}.sh. We report a few usage examples below.

Appendix B.3. Example-TTCS

Let us suppose that we want to verify TTCS system with 25 trains and formula . We have to navigate to the directory ttcs-f1

and then execute the BMC algorithm

The first argument sets the number of trains in the system to 25, and the second argument sets the initial k-path k to 0.

One can also perform all the experiments for the formula using the proper script:

It will perform all the experiments for .

References

- Zbrzezny, A.M.; Zbrzezny, A. Simple Bounded MTL Model Checking for Discrete Timed Automata (Extended abstract). In Proceedings of the 23th International Workshop on Concurrency, Specification and Programming (CS&P 2016), Rostock, Germany, 28–30 September 2016; Volume 1698, pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, T.; Sowmya, A. Analyzing an Embedded Sensor with Timed Automata in Uppaal. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. (TECS) 2013, 13, 44-1–44-26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Jiang, T.; Wang, M.; Tang, X.; Ji, W. Design and model checking of timed automata oriented architecture for Internet of thing. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2020, 16, 1550147720911008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, T.K.; Kristoffersen, K.J.; Larsen, K.G.; Laursen, M.; Madsen, R.G.; Mortensen, S.K.; Pettersson, P.; Thomasen, C.B. Model-checking real-time control programs: Verifying Lego(R) MindstormsTM systems using UPPAAL. In Proceedings of the 12th Euromicro Conference on Real-Time Systems (ECRTS 2000), Stockholm, Sweden, 19–21 June 2000; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, J. Model Checking Timed Safety Instrumented Systems; Research Report TKK-ICS-R3; Helsinki University of Technology, Department of Information and Computer Science: Espoo, Finland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hammal, Y.; Monnet, Q.; Mokdad, L.; Ben-Othman, J.; Abdelli, A. Timed automata based modeling and verification of denial of service attacks in wireless sensor networks. Stud. Inform. Universalis 2014, 12, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mouradian, A.; Augé-Blum, I. Modeling Local Broadcast Behavior of Wireless Sensor Networks with Timed Automata for Model Checking of WCTT. In Proceedings of the WCTT’12, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 4 December 2012; pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Alur, R.; Dill, D. A Theory of Timed Automata. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1994, 126, 183–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozga, M.; Hou, J.; Maler, O.; Yovine, S. Verification of Asynchronous Circuits using Timed Automata. Electr. Notes Theor. Comput. Sci. 2002, 65, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierks, H. PLC-automata: A new class of implementable real-time automata. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2001, 253, 61–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E.M.; Emerson, E.A. Design and Synthesis of Synchronization Skeletons Using Branching-Time Temporal Logic. In Proceedings of the Logics of Programs, Yorktown Heights, NY, USA, 4–6 May 1981; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; Volume 131, pp. 52–71. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, E.A.; Mok, A.K.; Sistla, A.P.; Srinivasan, J. Quantitative Temporal Reasoning. Real-Time Syst. 1992, 4, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pnueli, A. The Temporal Logic of Programs. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Providence, RI, USA, 20–23 October 1977; pp. 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Koymans, R. Specifying Real-Time Properties with Metric Temporal Logic. Real-Time Syst. 1990, 2, 255–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyer, P. Model-checking Timed Temporal Logics. Electr. Notes Theor. Comput. Sci. 2009, 231, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furia, C.A.; Spoletini, P. Tomorrow and All our Yesterdays: MTL Satisfiability over the Integers. In Proceedings of the ICTAC, Istanbul, Turkey, 1–3 September 2008; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5160, pp. 126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, H.; Ouaknine, J.; Worrell, J. On the Expressiveness and Monitoring of Metric Temporal Logic. Logical Methods in Comp. Sci. 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradella, M.; Morzenti, A.; Pietro, P.S. Bounded satisfiability checking of metric temporal logic specifications. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2013, 22, 20:1–20:54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henzinger, T.; Manna, Z.; Pnueli, A. What good are digital clocks? In Proceedings of the ICALP 92: Automata, Languages, and Programming, Wien, Austria, 13–17 July 1992; Kuich, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 545–558. [Google Scholar]

- Biere, A.; Cimatti, A.; Clarke, E.; Zhu, Y. Symbolic Model Checking without BDDs. In Proceedings of the TACAS’99, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 22–28 March 1999; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 1579, pp. 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Biere, A.; Cimatti, A.; Clarke, E.M.; Strichman, O.; Zhu, Y. Bounded Model Checking. Adv. Comput. 2003, 58, 117–148. [Google Scholar]

- Penczek, W.; Woźna, B.; Zbrzezny, A. Bounded Model Checking for the Universal Fragment of CTL. Fundam. Inform. 2002, 51, 135–156. [Google Scholar]

- Alur, R.; Henzinger, T.A. Real-time Logics: Complexity and Expressiveness. In Proceedings of the LICS ’90, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 4–7 June 1990; pp. 390–401. [Google Scholar]

- Alur, R.; Feder, T.; Henzinger, T.A. The Benefits of Relaxing Punctuality. J. ACM 1996, 43, 116–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, T. Specifying Timed State Sequences in Powerful Decidable Logics and Timed Automata. In Proceedings of the Formal Techniques in Real-Time and Fault-Tolerant Systems, Lübeck, Germany, 19–23 September 1994; pp. 694–715. [Google Scholar]

- Woźna-Szcześniak, B.; Zbrzezny, A. Checking MTL Properties of Discrete Timed Automata via Bounded Model Checking. Fundam. Inform. 2014, 135, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alur, R.; Henzinger, T.A. Logics and Models of Real Time: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Real-Time: Theory in Practice, REX Workshop, Mook, The Netherlands, 3–7 June 1991; de Bakker, J.W., Huizing, C., de Roever, W.P., Rozenberg, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; Volume 600, pp. 74–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozga, M.; Maler, O.; Tripakis, S. Efficient Verification of Timed Automata Using Dense and Discrete Time Semantics. In Proceedings of the Correct Hardware Design and Verification Methods, 10th IFIP WG 10.5 Advanced Research Working Conference, CHARME ’99, Bad Herrenalb, Germany, 27–29 September 1999; Pierre, L., Kropf, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 1703, pp. 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, J.; Kropf, T. Symbolic Verification and Analysis of Discrete Timed Systems. Form. Methods Syst. Des. 2003, 23, 67–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimatti, A.; Griggio, A.; Magnago, E.; Roveri, M.; Tonetta, S. Extending nuXmv with timed transition systems and timed temporal properties. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Aided Verification, New York, NY, USA, 15–18 July 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 376–386. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Abate, A.; Jiang, F.J.; Giacobbe, M.; Xie, L.; Johansson, K.H. Temporal logic trees for model checking and control synthesis of uncertain discrete-time systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2021, 67, 5071–5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussinie, F.; Markey, N.; Schnoebelen, P. Efficient timed model checking for discrete-time systems. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2006, 353, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystosik, A. Embedded Systems Modeling Language. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Dependability of Computer Systems (DepCoS-RELCOMEX 2006), Szklarska Poreba, Poland, 24–28 May 2006; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneel, H.; Kim, B.G. Discrete-Time Models for Communication Systems Including ATM; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 205. [Google Scholar]

- Belta, C.; Yordanov, B.; Gol, E.A. Formal Methods for Discrete-Time Dynamical Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.; Jones, M.; Martin, C. A discrete-time model with vaccination for a measles epidemic. Math. Biosci. 1991, 105, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lu, Y.; Garrido, J. A review of discrete-time risk models. RACSAM-Rev. De La Real Acad. De Cienc. Exactas Fis. Y Nat. Ser. A Mat. 2009, 103, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oli, M.K.; Venkataraman, M.; Klein, P.A.; Wendland, L.D.; Brown, M.B. Population dynamics of infectious diseases: A discrete time model. Ecol. Model. 2006, 198, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaas, K. MTL-Model Checking of One-Clock Parametric Timed Automata is Undecidable. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Synthesis of Continuous Parameters, SynCoP 2014, Grenoble, France, 6 April 2014; André, É., Frehse, G., Eds.; Open Publishing Association: Waterloo, Australia, 2014; Volume 145, pp. 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bae, K.; Lee, J. Bounded model checking of signal temporal logic properties using syntactic separation. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2019, 3, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Vardi, M.Y.; Rozier, K.Y. Satisfiability checking for mission-time LTL. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Aided Verification, New York, NY, USA, 15–18 July 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jonk, R.; Voeten, J.; Geilen, M.; Basten, T.; Schiffelers, R. SMT-based verification of temporal properties for component-based software systems. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.L.; Bersani, M.M.; Rossi, M.; San Pietro, P. Improved Bounded Model Checking of Timed Automata. In Proceedings of the 9th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Formal Methods in Software Engineering, FormaliSE@ICSE 2021, Madrid, Spain, 17–21 May 2021; Bliudze, S., Gnesi, S., Plat, N., Semini, L., Eds.; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, T.; Schupp, S. Controlling Timed Automata against MTL Specifications with TACoS. Sci. Comput. Program. 2022, 225, 102898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustadt, U.; Ozaki, A.; Dixon, C. Theorem Proving for Pointwise Metric Temporal Logic Over the Naturals via Translations. J. Autom. Reason. 2020, 64, 1553–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouaknine, J.; Worrell, J. Some Recent Results in Metric Temporal Logic. In Proceedings of the Formal Modeling and Analysis of Timed Systems, 6th International Conference, FORMATS 2008, Saint Malo, France, 15–17 September 2008; Cassez, F., Jard, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5215, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, D.; Prabhakar, P. On the expressiveness of MTL in the pointwise and continuous semantics. Int. J. Softw. Tools Technol. Transf. 2007, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyer, P.; Chevalier, F.; Markey, N. On the expressiveness of TPTL and MTL. Inf. Comput. 2010, 208, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbrzezny, A.M.; Zbrzezny, A. Checking MTL Properties of Timed Automata with Dense Time using Satisfiability Modulo Theories (Extended Abstract). In Proceedings of the 28th International Workshop on CS&P, Olsztyn, Poland, 24–26 September 2019; Volume 2571. [Google Scholar]

- Bonakdarpour, B.; Prabhakar, P.; Sánchez, C. Model checking timed hyperproperties in discrete-time systems. In Proceedings of the NASA Formal Methods Symposium, Moffett Field, CA, USA, 11–15 May 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 311–328. [Google Scholar]

- Penczek, W.; Półrola, A. Advances in Verification of Time Petri Nets and Timed Automata: A Temporal Logic Approach; Studies in Computational Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Tripakis, S.; Yovine, S. Analysis of Timed Systems Using Time-Abstracting Bisimulations. Form. Methods Syst. Des. 2001, 18, 25–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbrzezny, A. A new translation from ECTL* to SAT. Fundam. Informaticae 2012, 120, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biere, A.; Fazekas, K.; Fleury, M.; Heisinger, M. CaDiCaL, Kissat, Paracooba, Plingeling and Treengeling Entering the SAT Competition 2020. In Proceedings of the SAT Competition 2020–Solver and Benchmark Descriptions, virtual event affiliated with the 23rd International Conference on Theory and Applications of Satisfiability Testing, Alghero, Italy, 5–9 July 2020; Balyo, T., Froleyks, N., Heule, M., Iser, M., Järvisalo, M., Suda, M., Eds.; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2020; Volume B-2020-1, pp. 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Probst, D.K.; Li, H.F. Verifying Timed Behavior Automata with Nonbinary Delay Constraints. In Proceedings of the Computer Aided Verification, Fourth International Workshop, CAV ’92, Montreal, QC, Canada, 29 June–1 July 1992; von Bochmann, G., Probst, D.K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; Volume 663, pp. 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbrzezny, A.; Pólrola, A. SAT-Based Reachability Checking for Timed Automata with Discrete Data. Fundam. Informaticae 2007, 79, 579–593. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).