Abstract

The influence of wind on the maneuverability of sea-going vessels is a known factor limiting their maneuverability, especially in the case of very large vessels. Adverse weather conditions often limit the maneuverability of vessels or even make it impossible to enter the port. This results in longer delivery times for transported goods as well as measurable material losses for both carriers and their owners. This situation is often caused by a lack of information on differences in the prevailing weather conditions at the entrance to the port and at the seaport itself. There are simulation tools, such as the methods of computational fluid dynamics (CFD), which, after their appropriate adaptation and use in a virtual environment, have become important decision-making tools supporting the port administration when deciding about the movement of vessels. In this article, the authors present the results of research aimed at adapting one of the CFD methods for the needs of maritime navigation. The effects of the work were verified in a virtual environment and were successfully implemented in the port waters of Gdansk, Poland.

1. Introduction

The issue of the influence of wind on the behavior of a vessel in sea areas is documented in the subject-related literature. The most frequently examined research problem is its impact on the marine environment and maritime transport as a function of its direction and speed. The results of the analyses can be found in [1,2], for example. Hydro-meteorological conditions, which are interdependent, significantly influence the development of maritime transport. This problem is described even in extremely rarely frequented parts of the globe such as the Arctic; the problems in these latitudes are described in [3]. Wind also determines the level of safety in air transport; the problems in air navigation are outlined, for example, in [4]. Collecting long-term measurement data and analyzing their impact on various forms of navigation is very costly, and in the case of preparing port infrastructure construction projects, it is often not sufficient for their proper development. Therefore, modern navigation and maneuvering simulators have become the basic tool supporting design works. The design of a new port infrastructure is always verified in a virtual environment, as iterated in [5,6,7]. The authors also used this tool during the navigational analysis of the construction of a footbridge in Gdansk (Poland), as can be found in [8], or during the preparation of the virtual model of the Deep Water Container Terminal in Gdańsk. The results of using the navigation simulator are presented in [9]. However, the area of the authors’ interest includes not only the environmental conditions for the functioning of sea transport, but also the construction of virtual models of real vessels in the navigation simulator environment. In order to create a virtual model of a vessel, it is also necessary to understand its susceptibility to meteorological conditions, including the effects of wind [10].

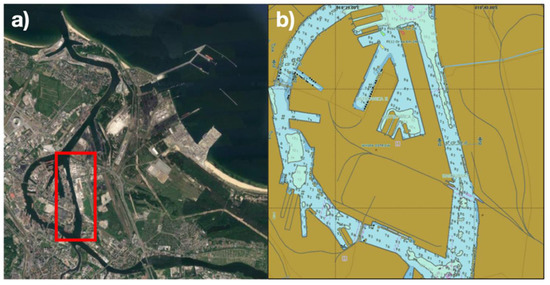

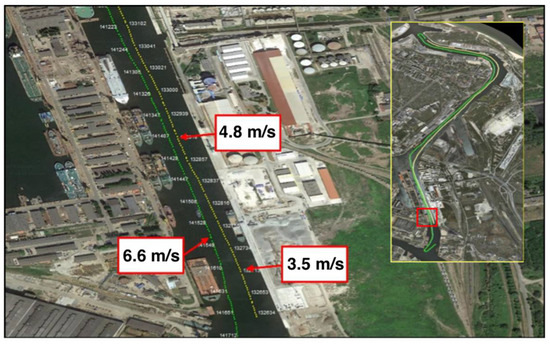

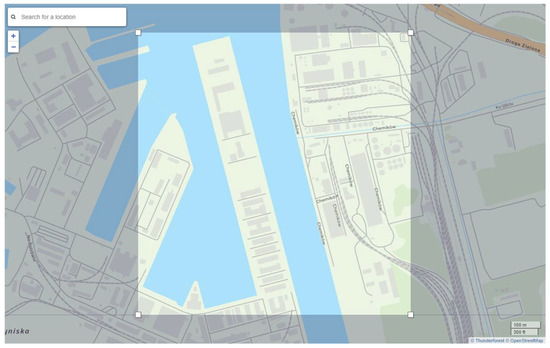

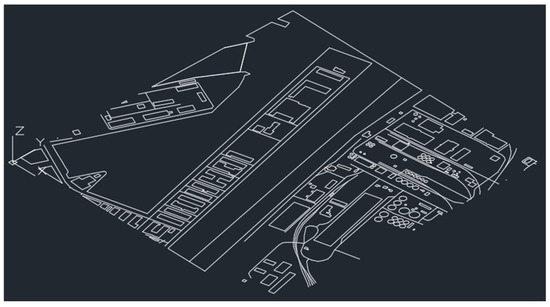

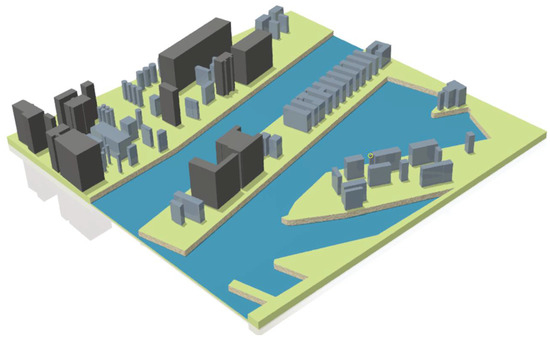

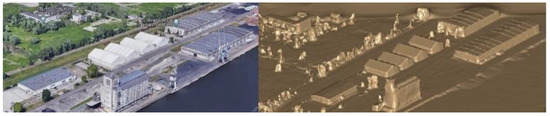

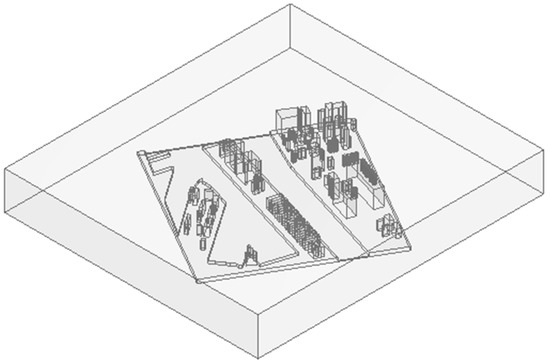

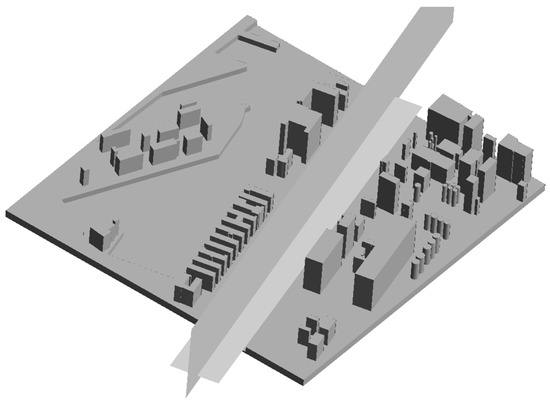

The issue of the influence of wind on a vessel’s behavior is an important aspect during the implementation of simulation tests. Proper vessel drift assessment for simulated weather conditions has a key impact on safe navigation. This is a particularly important factor when maneuvering in a port and on approach to ports. Currently, a common approach is the use of navigation and maneuvering simulators to assess the correctness of design assumptions for newly designed and reconstructed port waters, as outlined in [11]. Such projects require the implementation of detailed navigational analyses, one of the elements of which are simulation studies. Their goal may be, among other aspects, to determine the maximum dimensions of a vessel that can safely maneuver in a selected body of water [12]. Modern navigation and maneuvering simulators used during analyses made in port waters most often do not take into account the detailed impact of port buildings and other onshore infrastructure on the disturbance of the wind field. They use simple air flow models for coastal areas and buildings. Detailed turbulence models are included only for the calculation of forces between vessels [13]. To ensure a high level of credibility of simulation tests, maneuvering data should be recorded on real vessels, the virtual equivalents of which are used during the tests. For this purpose, one can use measurement sets that provide necessary data for analyses. For example, the set described in [14] allows the data necessary for the adaptation of the virtual vessel model that is available in the simulator environment for the purposes of design analyses to be obtained. At the stage of conducting analyses in the simulator environment, one should also have detailed knowledge about the distribution of the wind field. This is especially important during tests inside the port basin, where buildings and port infrastructure have a significant impact on the weakening of the wind field, and thus the change of the vessel’s maneuvering parameters. Currently, research teams most often use the approach of considering only the basic wind model available in simulators during research. The simulation assumes a constant wind speed and direction [15], which is in line with the current requirements. However, this approach does not provide real knowledge about the possibility of maneuvering vessels in the area under research, because the vessel behaves differently in open water and in the port under the same hydro-meteorological conditions. During this research, the aim of which was to determine the impact of buildings on the change of wind speed and direction in the Kashubian Canal in Gdansk (Poland), the authors decided to apply an innovative approach to the implementation of simulation studies, with a particular focus on navigational analyses. The effects of the work are the content of this article, which presents the use of CFD applications [16]. The use of this application allows us to obtain a detailed distribution of the wind field in the research area under consideration. The stages comprising the creation of three-dimensional models of port facilities and vessels [8,10] are very important elements of this process. In order to verify the possibility of using the CFD module, a number of real studies were carried out with the use of our own measurement platform [17], the results of which were compared with simulation studies. The results of the conducted tests and final analyses made it possible to develop new port procedures and increase the parameters of vessels that can operate at Gdansk Bulk Terminal (GBT) in the Kashubian Canal in Gdansk.

2. General Characteristics of Computational Fluid Dynamics

Computational fluid dynamics is a computer method of analysis that uses numerical methods and enables the fast, efficient, and accurate simulation of fluid flow and heat transfer in complex geometric systems [18]. Due to the discretization and numerical solution of partial differential equations describing the flow, it is possible to approximate the distribution of velocity, pressure, temperature, and other parameters in the flow. CFD methods are successfully used in numerical analyses with the aim of better understanding complex phenomena related to fluid movement. Thus, CFD methods are also widely used in engineering design in order to improve existing solutions or to create new ones [18]. Computational fluid dynamics is a branch of fluid mechanics that uses numerical analysis and algorithms to solve problems related to fluid flows. High-performance computers are used to make calculations required to simulate the interaction of liquids and gases with surfaces defined by boundary conditions. CFD is based on the Navier–Stokes equations. The equations resulting from the application of Newton’s second law to fluid motion, together with the assumption that the stress in a fluid is the sum of the diffusive viscous component and the pressure component, describe how the velocity, pressure, temperature, and density of a moving fluid are correlated [16].

Through CFD analysis, we can understand the flow and heat transfer throughout the design process. The basic methodology of any engineering CFD analysis is based on several procedures [16]:

- Understanding the flow model;

- Checking the adopted model;

- Model optimization.

Numerical fluid flow simulations are now widely used in various fields of science. Research and engineering teams use CFD in the following applications, among others [19,20,21,22,23,24]:

- Forecasting weather and warning against natural disasters;

- Vehicle design—improving aerodynamic properties;

- Designing the environment in an energy-saving and safe manner;

- Design and maintenance of pipeline networks in an optimal manner;

- Treatment and prevention of diseases, including diseases of the veins.

Commercially available CFD calculation software uses several main flow modeling methods. For the present research problem, the most reliable models are as follows:

- Large-eddy simulation (LES) and detached-eddy simulation (DES)The LES method allows us to adjust the precision of calculations to the problem undergoing research. Using this method, we obtain a numerical mapping of the wind effect on structures closest to the real impact. This method simulates vortices of a size similar to the size of the mesh element of the model grid. The basic limitations of the LES method are the computational capabilities of computers and time consumption.

- Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes solvers (RANS)The most frequently used method in calculations is the RANS method (in particular, the k-ε turbulence model), which is much faster [25]. It is a mathematical model based on average variable values for both steady state and dynamic flows. The RANS model can be used when simple buildings are considered.

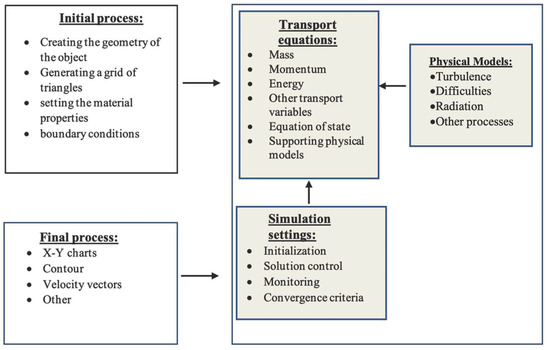

There are many computer programs available to solve the research problems related to CFD. These programs, depending on their complexity, can be free or commercial. However, when generalizing the way these applications work, the process of solving the problem is very similar.

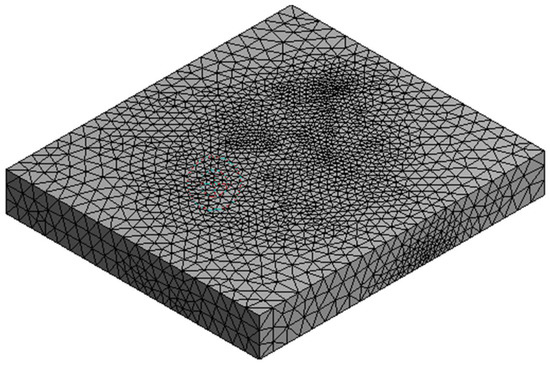

Figure 1 shows a simulation scheme using the ANSYS Fluent computer application [26] consisting of three basic elements of computer calculations.

Figure 1.

The simulation diagram in ANSYS Fluent.

Many turbulence models are used when using CFD applications to calculate fluid flow or air mass distribution. Basically, these models are classified according to the main equation and the numerical method. The most commonly used models of turbulence in computer applications are as follows:

- k-epsilon (k-ε);

- k-omega (k-ω);

- SST;

- SSG Reynolds.

As presented, for example in [27], the k-epsilon (k-ε) turbulence model is the most commonly used model in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and is used to simulate average flow characteristics for fully turbulent flow conditions. Therefore, this model was used in this research project. The model is based on two equations; in the first of which the transported variable is turbulent kinetic energy (k). In the second equation, however, the transport variable is the dissipation rate of turbulent kinetic energy (ε). It is worth mentioning that the model uses wall functions and is characterized by good convergence. It has low efficiency for complex flows with strong pressure gradients or a complex flow path. The model is highly developed and accurate despite many limitations. It includes sub-models to take into account compressibility, elasticity, etc. They are a great advantage of this model. It is worth mentioning that it is suitable for complex flows involving rapid changes in fluid parameters, moderate turbulence, or local disturbances (e.g., the detachment of the boundary layer, and turbulence behind flowing bodies).

The k-omega (k-ω) model is one of the most commonly used models of turbulence. It is a two-equation model, meaning that it contains two additional transport equations to represent turbulent flow properties. As in the k-epsilon turbulence model, wall functions are used here, and there is good convergence. Another advantage of this model is its high accuracy for internal flows and curves. The k-ω turbulence model is characterized by high efficiency compared with the models from the k-ε group, in terms of simulating the phenomena that occur in the boundary layer, flow disturbances, and flows at low Reynolds numbers. The k-omega model includes sub-models that take into account the compressibility of fluids and the transition state between laminar and turbulent flow, often used in the aerospace industry and rotating machinery (publication).

Menter’s shear stress transport model (SST) is a combination of two models: k-ε (in the outer boundary layer region) and k-ω (in the inner boundary layer region). It consists of two equations and is commonly referred to as a hybrid model due to the combination of two models. The shear stress transport formula (SST) combines the best features of the two components of this combination. It is a smooth transition from the standard k-ω model used in the boundary layer to the k-ε model as it moves away from the flow-limiting surface. The use of the k-ω formula in the inner parts of the boundary layer makes the model fit directly to the wall through a viscous sublayer; therefore, the k-ω SST model can be used without any additional damping functions [20]. The k-ω SST model unfortunately produces excessively high levels of turbulence in regions with high normal stress, such as stagnant regions and regions with high acceleration. This tendency is admittedly much less distinct than in the case of the normal k-ε model. It contains a modified turbulent viscosity formulation to account for the transport effect in terms of major shear stresses.

4. Construction of a Measuring Set for Real Measurements

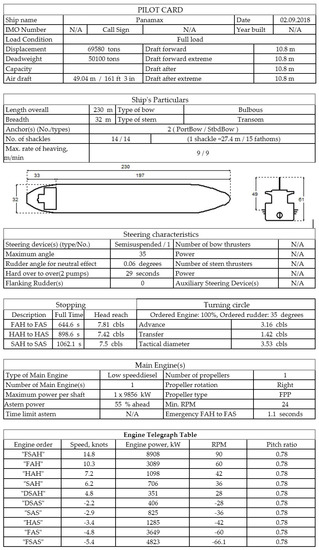

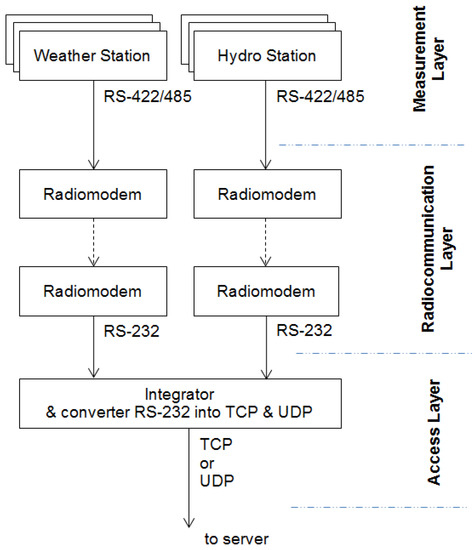

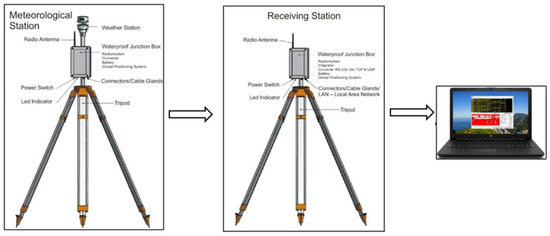

In order to obtain real measurement data, it is necessary to have an appropriate measurement set. A device must enable the registration of actual hydrometeorological conditions in selected parts of the water area at the same time. An important element of this process is the timing of the measurements for the purpose of their later comparison with the results obtained outside the port. For the purposes of this research, the authors of the article designed and built a set of mobile meteorological stations. The principle of the system is based on radio data transmission from the measuring stations to the receiving station. Figure 2 shows elements of the system used during statistic and dynamic tests.

Figure 2.

Weather data recording system: (a)—during static test, (b)—before dynamic test.

The developed weather data recording system enables both static and dynamic measurements. The main sensor for measuring the weather is the AIRMAR 150WX sensor. This model is recommended for moving applications in which the real and apparent winds are different. It includes additional sensors such as a 10 Hz GPS receiver, which gives the course over ground (COG), speed over ground (SOG) and position a solid-state two-axis compass and a three-axis accelerometer for pitch and roll, as well as a field-replaceable relative humidity sensor. It is equipped with configurable digital data outputs RS232, RS422, and the controller area network (CAN BUS), ensuring universal weather monitoring. Figure 3 shows a diagram of the weather data recording system.

Figure 3.

Block diagram of the measurement system.

The data recorded by the weather station are transmitted to the receiving station. Measurement data are recorded with the use of the “RealTerm” tool, which is a specialized application for capturing, controlling, and debugging complex data streams, both binary and of other types. The method of data transmission is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Method of data transmission.

6. Results of Simulation Analyses

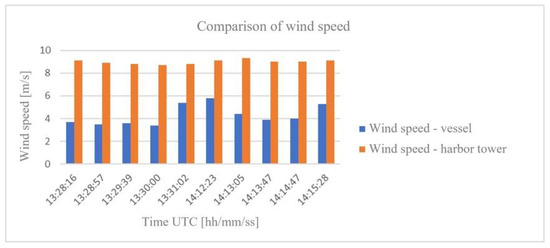

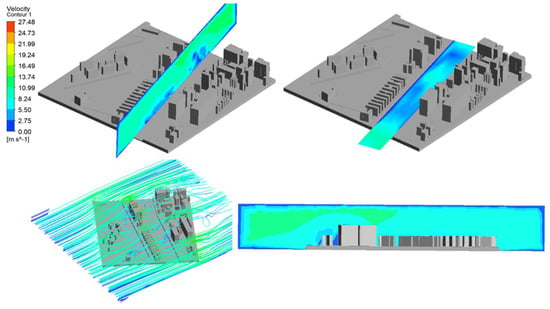

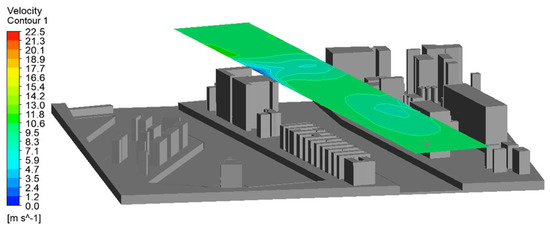

After making all the configurations and setting the input parameters, such as the boundary conditions in the simulation program, the simulations were performed. The input parameters of the wind in terms of its direction and speed were the values entered from the “port” column, which reflected the wind measurements at the Harbor Master’s Office tower, without taking into account the port buildings. The simulation results are presented in Table 3 and illustrated in Figure 16.

Table 3.

CFD simulation results for the height of the port wharf.

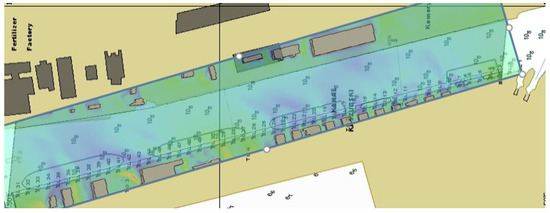

Figure 16.

Simulation results presented by means of a contour map.

Figure 16 shows the simulation results for the vertical and horizontal planes. They were prepared using a contour map.

In order to obtain the most reliable results regarding the use of CFD methods in supporting navigational analyses, additional computer simulations were performed. The simulations were performed to illustrate the wind speed at a different height, and the value adopted during the configuration was the height of 15 m because this is the height of the buildings in the simulated harbor area (Figure 17). The intention was that the wind speed at the height of 15 m, despite the unchanging nature of the buildings of the port, should differ from that calculated on the ground. In this way, another aspect of the problem was highlighted. Vessels moving in the port area have different windage areas depending on their height, which in turn translates into their variable susceptibility to wind in the same wind field. The methodology of using the CFD application enables us to obtain information about the vertical distribution of air masses, which is presented in the figure below, showing the wind speed in relation to the previous simulations.

Figure 17.

The simulation results presented for the horizontal plane at the height of 15 m, whereas Table 4 shows the values for the simulation at a height of 15 m.

The final stage of the work was the implementation of the results obtained from the CFD simulation into the simulator environment. This was achieved by creating a weather zone characterized by a detailed distribution of the wind field. Figure 18 shows a fragment of the simulation scenario with the texture applied to create the weather zone.

Figure 18.

The process of creating a weather zone.

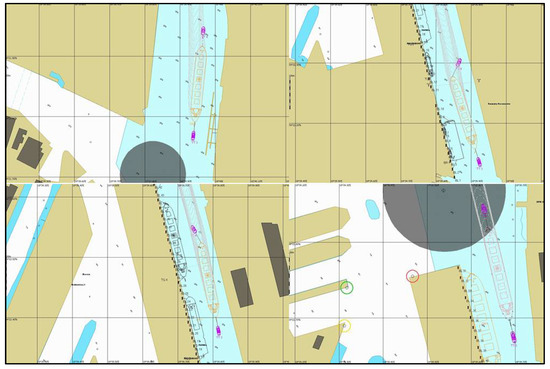

The prepared weather zone was used during simulation tests of the entry of a PANAMAX vessel to the port of Gdansk. The results of one of the series of simulations made for the purposes of the navigational analysis carried out for the Kashubian Canal at the Port of Gdansk are presented below [29,30]. The graphics show the course of the simulation (Figure 19) and the distribution of forces acting on the hull of the vessel towed through the Kashubian Canal (Figure 20 and Figure 21).

Figure 19.

Simulation of a vessel towing in the Kashubian Canal.

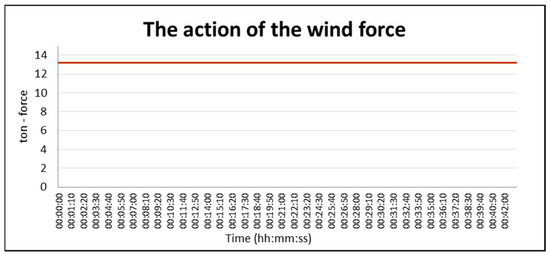

Figure 20.

The force of wind pressure on the vessel’s hull for constant parameters of the weather zone (1 ton force = 9.80665 kN in SI system).

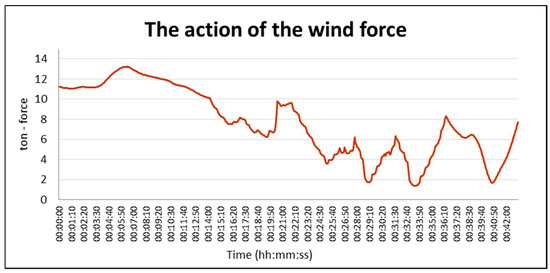

Figure 21.

The force of wind pressure on the vessel’s hull for a detailed distribution of the wind field (1 ton force = 9.80665 kN in SI system).

Figure 20 shows the distribution of forces acting on the hull without a specific weather zone; i.e., for a constant wind direction and speed. Due to the lack of variability of the wind parameters, the wind pressure force was constant at about 13 tons for a vessel, moving at a constant towing speed and a constant course.

Figure 21 shows the results of simulation tests for the prepared weather zone with a detailed distribution of the wind field. The curve shows the influence of the weather zone on the weakening of the wind field, i.e., the impact of buildings on the change of wind parameters. The graphic analysis shows the significant drops in wind pressure to values below 2 tons. This has a significant impact on the maneuverability of the vessel and the work of the tugs.

As can be seen in the figures above, there are significant differences in the force of the wind pressure on the vessel according to different parameters of the weather zone. The use of detailed weather information increases the realism of simulation research, especially when conclusions from simulation studies form the basis for building new port infrastructure. The use of CFD applications in modeling weather conditions in navigation and maneuvering simulators may be increasingly widely used in order to increase the level of navigation safety and the reliability of simulation tests.

7. Conclusions

The conducted research confirmed the discrepancy between wind field distribution in sea areas directly adjacent to sea ports and their counterparts in port waters. This situation often causes the port administration to refuse to maneuver large vessels in ports despite favorable weather conditions. Port regulations concerning port traffic usually relate to measurements taken at port entry heads and often restrict their operation. While such a situation is appropriate in small ports, it unnecessarily limits their work in ports with extensive infrastructure and in many port basins.

The use of a simple-to-use computer simulation can improve the port’s operation while ensuring an appropriate level of navigation safety in port basins.

The adaptation of the computational fluid dynamics methods proposed in this article gives the opportunity to present real weather conditions in port waters and can be a useful tool to support the decision-making process and improve the work of large seaports.

The theses made during the research were verified in a navigation and maneuvering simulator by implementing a detailed wind field distribution. The results of the simulation tests showed a satisfactory level of consistency of the wind speed results calculated by the application with the real measurements. This proves the possibility of using the CFD module for the implementation of simulation tests; in particular, navigation analyses.

The results of the simulation studies were implemented in the port of Gdansk, which led to a change in port regulations [29,30]. The change in the regulations made it possible to handle larger vessels by the port, which translated into an increase in the tonnage handled and a reduction in the time of reloading goods.

The use of CFD applications for modeling weather conditions in navigation and maneuvering simulators should be extended in order to increase the level of navigation safety and increase the attractiveness of seaports as important maritime transport hubs. As a result, this will not only accelerate the flow of increasing amounts of goods by sea, but it will also have a positive impact on the natural environment by reducing the pollution generated by other forms of transport.

The next stages of research currently being carried out by the authors are focused on a wider (than described in this article) use of CFD for navigational analyses as a function of the hydrological conditions prevailing in coastal sea and port areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.C., S.S. and P.Z.; methodology, K.C., S.S. and P.Z.; software, S.S. and P.Z.; validation, K.C. formal analysis, K.C.; investigation, S.S. and P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, K.C., S.S. and P.Z.; visualization, S.S. and P.Z.; supervision, K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The results of the research work presented in this article are a summary of one of the research stages carried out as part of the research project entitled “Research related to the development of the e-navigation concept within maritime transport telematics in the context of the integration of terrestrial and satellite navigation systems and the development of spatial information systems technologies, including their impact on the safety of maritime and inland navigation” (no. WN/2021/PZ/01) and the project entitled “Automation and autonomy of navigation processes as well as the development of navigation and hydrographic systems, devices and technologies”. The study was funded by the Gdynia Maritime University and Polish Naval Academy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available upon request of the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to third party copyright. The measurements were conducted on behalf of a third party.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Xu, S.; Ma, M.; Yin, K.; Tang, S. Risk evaluation system of navigation security based on coupled wind and wave model: A case of study of Qiongzhou strait. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 14, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T. Comparing Winds Near Tropical Oceanic Precipitation Systems with and without Lightning. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasserre, F.; Pelletier, S. Polar super seaways? Maritime transport in the Arctic: An analysis of shipowners’ intentions. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Li, Z.; Ju, T.; Zhang, H. Characteristics of Low-level jets during 2015–2016 and the effect on fog in Tianjin. Atmos. Res. 2020, 245, 105102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucma, S.; Gucma, M. Optimization of LNG terminal parameters for a wide range of gas tanker sizes: The case of the port of Świnoujście. Arch. Transp. 2019, 50, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucma, L.; Gralak, R.; Artyszuk, J.; Boć, R. Applying Simulation Studies to Define Further Development of the Approach Channel to Ystad; Scientific Journals of the Maritime University of Szczecin: Szczecin, Poland, 2018; Volume 54, pp. 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwolan, P.; Czaplewski, K. Methodology of Creation the Simulation Basin based on the Projected Canal through the Vistula Spit. Annu. Navig. 2015, 22, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplewski, K.; Zwolan, P. Construction of virtual models of water areas for navigational analyses. In Proceedings of the European Navigation Conference (ENC 2019), Warszawa, Poland, 9–12 April 2019; IEEE Xplore: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplewski, K.; Zwolan, P. The Virtual Model of Deep Water Container Terminal T2 in Port Gdansk; TransNav: Gdynia, Poland, 2018; Volume 12, pp. 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplewski, K.; Zwolan, P. Constructing and editing virtual models of ships for navigational analyses. In Proceedings of the European Navigation Conference (ENC 2019), Warszawa, Poland, 9–12 April 2019; IEEE Xplore: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łazuga, K.; Quý, N.; Gucma, L. Cost-Effective Design of Port Approaches Using Simulation Methods Based on the Example of a Modernized Port in the Ustka. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplewski, K.; Zwolan, P. The Use of Simulation Methods to Determine the Maximum Dimensions of the Ship Capable to Maneuvering on the Selected Sea Area. Annu. Navig. 2011, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Czaplewski, K.; Zwolan, P. Multicriteria Analysis Method for Evaluation of Vessel Simulation Models in Open Waters. J. Navig. 2019, 72, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplewski, K.; Zwolan, P. A Vessel’s Mathematical Model and its Real Counterpart: A Comparative Methodology Based on a Real-world Study. J. Navig. 2016, 69, 1379–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. Safety Assessment of Navigation Based on Ship Handing Simulator. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS), Liverpool, UK, 14–17 July 2019; pp. 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Von Wendt, J. Computational fluid dynamics. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1992, 40, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Swierczyński, S.; Zwolan, P. Wykorzystanie mobilnej platformy pomiarowej w zastosowaniach nawigacyjnych. Sci. J. Pol. Nav. Acad. 2014, 196, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajishima, T.; Taira, K. Computational Fluid Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-45304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Luxbacher, K.D.; Ragab, S.; Xu, J.; Ding, X. Computational fluid dynamics applied to mining engineering: A review. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2016, 31, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagan, J.; Smierciew, K.; Butrymowicz, D.; Karwacki, J. Comparative study of turbulence models in application to gas ejectors. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2014, 78, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besagni, G.; Inzoli, F. Computational fluid-dynamics modeling of supersonic ejectors: Screening of turbulence modeling approaches. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 117, 122–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toja-Silva, F.; Kono, T.; Peralta, C.; Lopez-Garcia, O.; Chen, J. A review of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations of the wind flow around buildings for urban wind energy exploitation. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2018, 180, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, P.D.; Narracott, A.; von Tengg-Kobligk, H.; Soto, D.A.S.; Hsiao, S.; Lungu, A.; Evans, P.; Bressloff, N.W.; Lawford, P.V.; Hose, D.R.; et al. Computational fluid dynamics modelling in cardiovascular medicine. Heart 2016, 102, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhunny, A.; Lollchund, M.; Rughooputh, S. Wind energy evaluation for a highly complex terrain using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). Renew. Energy 2017, 101, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hooff, T.; Blocken, B.; Tominaga, Y. On the accuracy of CFD simulations of cross-ventilation flows for a generic isolated building: Comparison of RANS, LES and experiments. Build. Environ. 2017, 114, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansys Fluent|Fluid Simulation Software. Available online: https://www.ansys.com/products/fluids/ansys-fluent (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Shirzadi, M.; Mirzaei, P.A.; Naghashzadegan, M. Improvement of k-epsilon turbulence model for CFD simulation of atmospheric boundary layer around a high-rise building using stochastic optimization and Monte Carlo Sampling technique. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2017, 171, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Hydrographic Office. Admiralty Sailing Directions NP18 Baltic Pilot Volume I; UK Hydrographic Office: Tauton, UK, 2020.

- Zwolan at all, Simulation Tests of the Ship Transmission through the Kashubian Channel; Research Project N-4-3-0-01005/2018; Polish Naval Academy: Gdynia, Poland, 2018.

- Zwolan at all, Simulation Tests of the Ship Transmission through the Kashubian Channel Part II; Research Project N-4-1-0-001/2019; Polish Naval Academy: Gdynia, Poland, 2019.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).