Abstract

The evolution of intelligent manufacturing has had a profound and lasting effect on the future of global manufacturing. Industry 4.0 based smart factories merge physical and cyber technologies, making the involved technologies more intricate and accurate; improving the performance, quality, controllability, management, and transparency of manufacturing processes in the era of the internet-of-things (IoT). Advanced low-cost sensor technologies are essential for gathering data and utilizing it for effective performance by manufacturing companies and supply chains. Different types of low power/low cost sensors allow for greatly expanded data collection on different devices across the manufacturing processes. While a lot of research has been carried out with a focus on analyzing the performance, processes, and implementation of smart factories, most firms still lack in-depth insight into the difference between traditional and smart factory systems, as well as the wide set of different sensor technologies associated with Industry 4.0. This paper identifies the different available sensor technologies of Industry 4.0, and identifies the differences between traditional and smart factories. In addition, this paper reviews existing research that has been done on the smart factory; and therefore provides a broad overview of the extant literature on smart factories, summarizes the variations between traditional and smart factories, outlines different types of sensors used in a smart factory, and creates an agenda for future research that encompasses the vigorous evolution of Industry 4.0 based smart factories.

1. Introduction

With its introduction in Germany in 2011, Industry 4.0 instantly became the focus of a global world that promoted the computerization of manufacturing [1]. Industry 4.0 has revolutionized the manufacturing process, leading to intelligent manufacturing promising self-sufficient manufacturing processes by using machines and devices that communicate with each other through digital connectivity [2,3]. Although most of the design philosophies and technologies of Industry 4.0, such as the internet of things (IoT), cyber-physical systems (CPSs), and artificial intelligence are already in use, most firms lack insight into the wide set of technologies offered by Industry 4.0 that provide devices with seamless connectivity, interoperability, visibility, and intelligence capabilities.

Applications in traditional manufacturing are stand-alone and segregated [4], and lack automated monitoring and control capabilities [5]. There are a series of distinct and independent steps, including marketing, product development, manufacturing, and distribution to customers [1]. As a result, the reuse of systems, and the integration of physical and digital systems, in traditional manufacturing is poor [6]. Some advanced manufacturing strategies, such as intelligent manufacturing, flexible manufacturing, and agile manufacturing have the potential to overcome the drawbacks of traditional manufacturing [7,8,9]. These manufacturing schemes are the pioneers of Industry 4.0 smart manufacturing, where machines and products interact with each other without, or with minimal, human control [4,6].

Manufacturing industry plays a crucial role in the evolution of modern society. Industry 4.0, which is the pioneer of smart factories, has access to various advanced technologies such as big data analytics, artificial intelligence, advanced robotics, 3D printing, and cloud computing [1,3]. The vast implementation of computer numerical control (CNC) and industrial robots has enabled a flexibility in manufacturing systems [10,11,12]; whereas computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided processing planning (CAPP) have made computer integrated manufacturing practical [13,14]. The actual uses of the IoT have enabled manufacturers to adopt digital transformations from different prospects, such as efficient productivity, automation, customer focus, competitive advantages, and enhancing the value chain and rapid returns [15,16].

In an attempt to understand the efficient use of the IoT in the manufacturing industry, it is imperative to recognize the different technologies, especially sensors that make the performance of manufacturing firms efficient in using Industry 4.0. By combining everyday objects with connected devices through IoT, it is possible to gather information, analyze it, and create an action that learns from processes. The focal objective of the concept of Industry 4.0 is to characterize highly digitized manufacturing processes, where flow of information amid different devices is controlled in an environment with very limited human intervention [3,5,17]. Cloud-based IoT platforms have the ability to connect the real world with the virtual world, enabling companies to manage IoT device connectivity and flexibility [18]. In addition, the IoT architecture must be flexible enough to operate different wireless protocols and accommodate additions of new sensor inputs (e.g., USB) [19]. This can also be acknowledged in terms of physical flexibility, which can include wearable devices, carry devices, battery usage, etc. [7]. The use of sensors makes this achievable.

Recently, Industry 4.0 based manufacturing processes have attracted a lot of attention from academia [5,6,7,20], with the main focus on different areas such as sustainability, organizational structure, lean manufacturing, product development, and strategic management within the manufacturing industry. Researchers have investigated the relationship between different optimal control models and an Industry 4.0 based smart factory system [9]. Comprehensive work has been done in analyzing the benefits, challenges, and risks involved with implementing smart factories. The majority of the extant literature focuses on the contributions and threats of IoT related to flexibility, transparency, information sharing, connectivity, traceability, and tracking within Industry 4.0. While a lot of research has been carried out with a focus on analyzing the performance, processes, and implementation of Industry 4.0 based smart factories, it has been found that most firms still lack in-depth insight into the difference between traditional and smart factory systems, as well as the wide set of different sensor technologies associated with Industry 4.0. This paper tries to fill this gap by identifying the different sensor technologies of Industry 4.0 available, and identifying the differences between traditional and smart factories. In addition, this paper reviews existing research that has been done on Industry 4.0; therefore, provides a broad overview of the extant literature on Industry 4.0, summarizes the variations between traditional and smart factories, and creates an agenda for future research that encompasses the vigorous evolution of Industry 4.0.

2. Smart Factory

Although automation has become a crucial part of the factory, innovative manufacturers have taken the opportunity to take it to a whole new level through the application of IoT and artificial intelligence in production processes. With enhancing the complexity of cyber physical systems, the physical machines and business processes have combined with automation to give rise to complex optimization decisions that were made traditionally by humans [5,21,22]. This has enabled manufacturers to integrate the floor decisions and perceptions with the supply chain, giving birth to what we now call a smart factory. The introduction of mechanical manufacturing equipment marked the first industrial revolution, followed by the development of the mass production of goods [13]. The digital revolution was considered to be the adoption of increased automation and control in manufacturing processes by using electronics and IT [12]. The adoption of IoT in these processes has given rise to the deviation of the centralized factory system to a decentralized system [12,13,14]. This technology has enabled machines and industries to go through a self-optimization and reconfiguration, to adapt their behavior to changes in orders and operating conditions [23,24]. The core of smart factories is the technology that makes data collection possible. This technology includes intelligent sensors, motors, and robotics which are employed on the production and assembly lines of the manufacturing industry [17].

Smart Factory vs. Traditional Factory

In order to meet drastic changes in customer demands, the manufacturing process requires abilities that help in adjusting product type and production capacity, to enable the handling of multiple product varieties [25]. Manufacturing should have adequate functionality, scalability, and connectivity with customers and suppliers to meet such challenges. Traditional factories lack capabilities that allow them to monitor and control automated and complex manufacturing to enable efficient production of customized products [26]. Traditional factories have stand-alone and segregated applications with less integration of the production system, product life cycle, and value chain. Consequently, there is poor reuse of systems and integration between real and virtual systems in a traditional set-up. A general concept of a smart factory can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Concept of a smart factory.

The smart factory is an upgrade from old-fashioned automation to a linked and flexible system, and which constitutes a continual data stream through highly connected operations and production systems which can learn and adapt to changing demands [26,27,28]. These factories can assimilate data from physical, operational, and human assets to drive manufacturing, maintenance, inventory tracking, digitization of operations, and other activities in manufacturing systems [29]. The main aim of smart factories is to use intelligent production systems and suitable engineering methods for the successful and interconnected implementation of production facilities [25,30]. It is an engineering system that operates on interconnection, collaboration, and execution. Interconnecting devices in smart factories allow the exchange of information, recognize and assess situations, and integrate the physical world with the digital world, making smart factories adaptive in nature [23,31]. In other words, the smart factory integrates physical and cyber technologies and makes the involved technologies more accurate, enhancing the performance, quality, controllability, management, and transparency of the manufacturing processes. In such a smart factory environment, the manufacturer has the ability to meet customer requirements by changing the production specifications and other settings of the machines at the last minute. This ability is not present in traditional factories [32] (Table 1). The true feature of a smart factory lies in its capability to readjust and evolve along with the growing needs of the organization [32,33]. These needs can be categorized into: changing customer demands, emergence of new markets, development of new products and services, enhanced productive approaches to operations, and use of advanced technologies in maintenance processes [13,34,35]. The ability to tailor and learn from real-time data makes smart factories more receptive and predictive, to avoid operational downtime and other possible failures in processes [12,29].

Table 1.

Key differences between the traditional manufacturing factory and smart factory.

A smart factory is characterized by four intelligent features:

- Sensors: these are devices that have the ability to self-organize, learn, and maintain environmental information to analyze behaviors and abilities. Therefore, sensors can make decisions that enable them to adjust to changes in the environment.

- Interoperability: through interconnection between different devices, coordination between them can be enhanced, allowing flexibility in configuration protocols of the production system.

- Integration: robots and artificial intelligence (AI) allow smart factories to have a high level of integration among processes. AI, along with the integration of human intellectual capabilities, enables factories to perform analysis and decision making.

- Virtual reality (VR) techniques: as one of the high-level components of smart factories, VR facilitates human–machine integration by virtualizing manufacturing processes using computers, signal processing, animation technology, intelligent reasoning, prediction, and simulation and multimedia technologies.

3. Key Sensing Technologies in a Smart Factory

Smart factories are comprised of intelligent machines, devices, and control equipment that monitor vital parameters of the manufacturing processes [5]. These improvements have not only altered the factory floor infrastructure, promoting steady and precise collaboration between machines, but have also altered machinery requirements, increasing demand for reliable sensors [10]. This section gives brief information about the key sensors used in a smart factory.

3.1. Passive Sensors

The current manufacturing system is defined by different technologies, however the main technologies used are sensors, actuators, effectors, controllers, and control loops [36]. A vital role is played by sensors in a smart factory, as they collect and implement accurate data into the manufacturing processes to enhance product quality. Sensors are electrical, opto-electrical, or electronic devices consisting of sensitive materials that help to determine the presence of a particular entity or function [37]. In many cases, a physical stimulus is transformed into an electrical signal using sensors, which then can be evaluated and analyzed for making decisions about the operations being carried out [5,36]. Recent developments in sensor technology have enabled manufacturers to control and acquire data like never before.

Sensors can operate either actively or passively [36,38]. When operating actively, a particular physical stimulus is required for the sensor to work. For example, color identification sensors are active as they need visible light to illuminate the object so that the sensor can receive a physical stimulus. In the passive instance, the physical stimulus is already present and does not have to be provided [38]. For example, infrared devices are passive as the stimulus is already being generated from infrared radiation that is linked with the temperature of a body.

Several types of sensors have been developed and used successfully in industrial process control. Smart factories use a variety of sensor types, from basic temperature to humidity monitoring to sophisticated position and product sensing [39,40]. These sensors make manufacturing efficient by helping in advance factory operations, such as moving products, controlling robotic and milling processes, and sensing environmental factors. The main measurement and control parameters in a factory environment are temperature, position, force, pressure, and flow [40].

3.1.1. Temperature Sensors

As temperature directly affects material properties and product quality, it is one of the crucial parameters to be measured and controlled in industrial plants. A temperature sensor is a device that has the ability to collect temperature concerned information from a resource, and then changes it into information that can be understood by another device [41]. These sensors have the ability to measure the thermal characteristics of gases, liquids, and solids. Several temperature sensors have been developed in recent years which can be used in electrically and chemically hostile environments. These sensors can be divided into two groups: (1) low-temperature sensors, with a range of −100 to +400 °C, using sensing materials such as phosphors, semi-conductors, and liquid crystals; and (2) high-temperature sensors with a range of 500 to 2000 °C, based on blackbody radiations [25,40,42]. Table 2 shows the different sub-types of temperature sensor, along with their key features.

Table 2.

Key features of temperature sensors.

3.1.2. Pressure Sensors

Pressure sensors have the ability to capture pressure changes and transform them into an electrical signal, where the applied pressure defines its quantity. These are electro-mechanical devices that identify force in gases or liquids and provide control signals to display devices [25,37,43]. These sensors can also be used to detect atmospheric changes [51]. For example, barometric pressure sensors have the ability to detect changes in the atmosphere that are helpful for the prediction of weather patterns and changes. Another example is vacuum sensors, which are used when pressure in a vacuum is below atmospheric pressure levels, which can be difficult to detect using mechanical methods. Table 3 shows the different sub-types of pressure sensors along with their key features.

Table 3.

Key features of pressure sensors.

3.1.3. Position Sensors

These sensors are used to sense the positions of valves, doors, throttles etc. These sensors are equipped with location tracking abilities that help to determine the precise positions of work-in-progress, tools, and other production-relevant items within the facility [57,58]. Motion sensors (which trigger actions such as illuminating a floodlight by detecting movement of an object) and proximity sensors (which detect that an object has come within the range of a sensor) are worth mentioning as they serve functions similar to position sensors [59,60]. Table 4 shows the different sub-types of position sensors along with their key features.

Table 4.

Key features of position sensors.

3.1.4. Force Sensors

Force sensors are designated to translate applied forces (such as tensile, compressive force, etc.) into electric signals which reflect the degree of force [63,64]. These signals are then sent to indicators, controllers, or computers that inform operators about the processes, or serve as inputs that help to achieve control over machinery and processes. A variety of force sensors are being used in smart factories depending on the type of force being measured [65]. For instance, load cells measure compressive forces, strain gauges measure the internal resistance forces, and force sensing resistors measure the rate of change of an applied force. Table 5 shows the different sub-types of force sensors, along with their key features.

Table 5.

Key features of force sensors.

3.1.5. Flow Sensors

These sensors have the ability to sense the movement of gases, liquids, or solids within a pipe or a conduit. These sensors have extensive uses in processing industries, and allow operation of the machinery at an optimum performance level [67,68]. A flow sensor can be electronic, using ultrasonic detection of the flow, or partially mechanical [69]. For instance, flow sensors in automobiles measure air intake in the engine and adjust fuel delivery to the fuel injectors in order to provide optimum fuel to the engine. Flow sensors are also used in medical ventilators, where the correct rate of delivery of air and oxygen to patients is needed for respiration [70]. Table 6 shows the different sub-types of flow sensors along with their key features.

Table 6.

Key features of flow sensors.

3.2. Smart Sensors

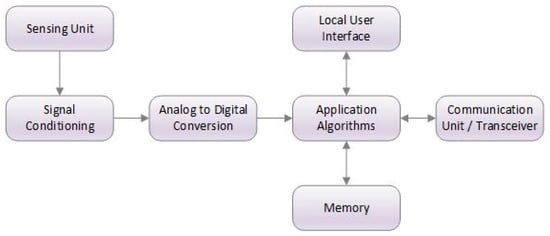

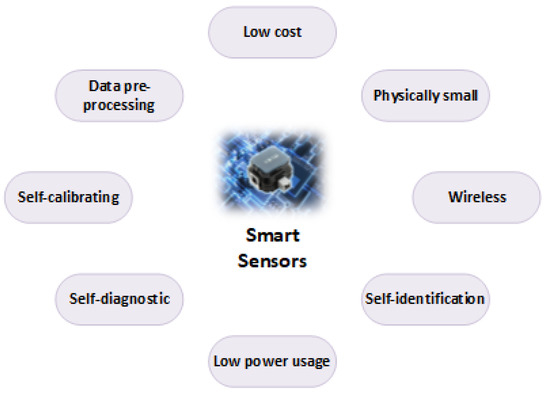

Among other recent advances in technology, smart sensors have been in the spotlight in terms of their potential significance and wide range of application areas. With the integration of computing and IoT in industrial processes, ordinary sensors have been transformed into smart sensors providing them with abilities to carry out complex calculations with collected data [37,40]. Apart from increased capabilities, smart sensors have also become remarkably small and exceedingly flexible, turning bulky machines into high-tech intel. Equipped with signal conditioning, embedded algorithms, and digital interfaces, smart sensors have become devices with detection and self-awareness capabilities [25,72]. These sensors are built as IoT components that convert real-time information into digital data that can be transmitted to a gateway [36,73]. These abilities allow smart sensors to predict and monitor real time scenarios and take corrective actions in an instant. Complex multi-layered operations such as collecting raw data, adjusting sensitivity, and filtering, motion detection, analysis, and communication are the main functions of intelligent sensors [38]. For instance, wireless sensor networks (WSNs) are one of the applications of smart sensors, whose nodes are connected with one or more other sensors and sensor hubs, making a communication technology of some kind. In addition, information from multiple sensors can be combined to deduce conclusions about an existing problem; for instance, temperature and pressure sensor data can be used to infer the onset of a mechanical failure. Figure 2 shows the building blocks of a typical smart sensor [41], while Figure 3 summarizes the key features of smart sensors [51,72].

Figure 2.

Smart sensor building blocks.

Figure 3.

Features of a smart sensor.

3.2.1. Calibration Capability

The ability of a sensor to determine its normal function is termed calibration capability [39]. Self-calibration is simple in many cases, and different calibration techniques are available for different types of sensors:

- Sensors with an electric output carry out calibration by using a known reference of voltage level.

- Sensors such as load cells used for weighing systems can adjust their output to zero when no force is being applied [27].

- Other sensors can use look-up tables for calibration. However, to carry out calibration using look-up tables, a huge amount of memory capacity must be available to store correction points due to the large volume of data gathered during the process. On the contrary, an interpolation method is preferable in which a small matrix of correction points is required [35].

3.2.2. Self-Diagnosis of Faults

Smart sensors carry out self-diagnosis by observing internal signals for evidence of faults. Differentiating between normal measurement deviations and sensor faults can be a challenge for some sensors [72]. This challenge is overcome by storing multiple measured values around a set-up point and calculating minimum and maximum values for the measured quantity [51]. In order to measure the impact of sensor fault on the measured quantity, uncertainty techniques are used. This enables the continuation of using a sensor after the fault has arisen.

3.3. Nuclear Sensors

Nuclear sensors are very uncommon [37,74] due to two reasons: they are costly and have strict safety regulations for their use. Recent developments have made the availability of low-level radiation sources for safe use of these sensors [37]. Table 7 summarizes the pros and cons of these sensors.

Table 7.

Key features of nuclear, micro, and nano sensors.

3.4. Micro-Sensors (MEMS Sensors)

Micro-sensors contain two and three dimensional micro-machined structures that are a part of microelectromechanical system (MEMS) devices [74,75]. These sensors can be regarded as small sized transducers, as they convert mechanical signals from an energy source into electrical form. Currently, sensors that measure temperature, pressure, force, speed, sound, magnetic field, optical, biomedical, and chemical features are being used successfully by industries [37,74]. Table 7 summarizes the main characteristics of these sensors.

3.5. Nano-Sensors (NEMS)

Nano-sensors, based on nanotechnology, are the most recent development in sensing technology [72,75]. These are a part of nano-elctromechanical system (NEMS) devices which include nano-actuators as well. Table 7 gives a summary of these sensors.

4. Conclusions

This paper has discussed the different types of sensor technology used in the manufacturing industry, specifically in smart factories. An extensive review of the extant literature is also presented on the technology lead smart factory. Key differences between a smart factory and traditional factory have been highlighted. Use of sensors, interoperability of different IoT devices, integration of robotics and AI, and use of VR techniques were found to be the key intelligent features of a smart factory. As sensors are an important component of a smart factory, the main sensor types and their sub-types, along with their characteristics, materials, uses, application areas, advantages and disadvantages have been identified in this paper. Sensors and Wi-fi are changing the way people communicate with the surrounding world, bringing a new era of connectivity, termed the internet of things. This technology has the potential to provide virtually boundless opportunities to businesses and communities, with enhanced connectivity and use of collected data. With the help of these technologies, data flow is integrated between partners, suppliers, and customers, as well as organizations to develop a finalized product according to customer demands. Manufacturers around the world are beginning to realize the importance of sensors, and the benefits of merging traditional operations and IoT. Therefore, a developing trend for the smart factory is human–machine collaboration. This paper attempted to provide a broad overview of the extant literature on Industry 4.0, summarizing the variations between traditional and smart factories, and the main sensors used within a smart factory setup.

While aspects of the smart factory have been successfully implemented in several key industries (e.g., the chemical industry), it has been found that there are technological, cost, and knowledge barriers to the broader implementation of sensors across manufacturing [20]. These barriers also include standardization, cyber security, and risk concerns, which may enhance organizational resistance to automation within the factory. In terms of standardization, two Industry 4.0 reference architectures have been standardized, namely, Reference Architecture Model Industry 4.0, from the International Electrotechnical Commission, and Industrial Internet Reference Architecture, from the Object Management Group. A discussion on these standardized architectures and the compatibility of each Industry 4.0 proposal to these standards is needed. Moreover, the concept of digital twin in the manufacturing system configuration stage, which can enable the validation of system performance in a semi-physical simulation manner, is gaining interest. The digital twin conducts a direct test and validation that can quickly locate the problem and malfunctioning part, rectify the design mistakes, and test the workability of equipment in the system execution [76,77]. In addition, a deficiency of labor skills and manufacturer technical willingness relative to available technologies can be limiting. It has been revealed that there is a scarcity of studies that address these issues. Furthermore, artificial intelligence, block chain, cloud computing, and big data analytics (also known as ABCD) are known for the generation of information technology [76]. The employment of blockchain in smart factories is known to enable increased security, enhanced traceability, and reduced costs [76,77]. These features along with standardization and cyber security issues need a detailed study and therefore, are identified as a future extension of this work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K., N.R. and S.A.; methodology, T.K. and S.A.; formal analysis, T.K.; investigation, T.K.; resources, N.R. and M.U.-R.; data curation, T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K. and S.A.; writing—review and editing, T.K. and M.U.-R.; visualization, T.K.; supervision, N.R. and S.A.; funding acquisition, N.R.; project administration, N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chang, W.; Ellinger, A.E.; Kim, K.; Franke, G.R. Supply chain integration and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis of positional advantage mediation and moderating factors. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, B.; Umair, M.; Shah, G.A.; Ahmed, E. Enabling IoT platforms for social IoT applications: Vision, feature mapping, and challenges. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 92, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo-Branco, I.; Cruz-Jesus, F.; Oliveira, T. Assessing Industry 4.0 readiness in manufacturing: Evidence for the European Union. Comput. Ind. 2019, 107, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Xie, Y.; Xue, W.; Chen, Y.; Fu, L.; Xu, X. Smart factory in Industry 4.0. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2020, 37, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lass, S.; Gronau, N. A factory operating system for extending existing factories to Industry 4.0. Comput. Ind. 2020, 115, 103128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Yin, Y.; Xue, W.; Shi, H.; Chong, D. Intelligent supply chain performance measurement in Industry 4.0. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2020, 37, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.M.; Hussein, D.; Park, S.; Han, S.N.; Crespi, N. The Cluster between Internet of Things and Social Networks: Review and Research Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, L.; Filippini, R. Organizational and managerial challenges in the path toward Industry 4.0. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, G.L.; Giglio, R.; Van Dun, D.H. Industry 4.0 adoption as a moderator of the impact of lean production practices on operational performance improvement. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2019, 39, 860–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimini, C.; Pirola, F.; Pinto, R.; Cavalieri, S. A human-in-the-loop manufacturing control architecture for the next generation of production systems. J. Manuf. Syst. 2020, 54, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Qi, Q.; Liu, A.; Kusiak, A. Data-driven smart manufacturing. J. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 48, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkesmann, M.; Wilkesmann, U. Industry 4.0—organizing routines or innovations? VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2018, 48, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrouf, F.; Ordieres, J.; Miragliotta, G. Smart factories in Industry 4.0: A review of the concept and of energy management approached in production based on the Internet of Things paradigm. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia, 9–12 December 2014; pp. 697–701. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, J.; Kaur, K. A fuzzy approach for an IoT-based automated employee performance appraisal. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2017, 53, 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zanella, A.; Bui, N.; Castellani, A.; Vangelista, L.; Zorzi, M. Internet of things for smart cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014, 1, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemaghaei, M.; Ebrahimi, S.; Hassanein, K. Data analytics competency for improving firm decision making performance. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2018, 27, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, G.B.; Ayala, N.F.; Frank, A.G. Industry 4.0 innovation ecosystems: An evolutionary perspective on value cocreation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 228, 107735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehami, J.; Nawi, M.; Zhong, R.Y. Smart automated guided vehicles for manufacturing in the context of Industry 4.0. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 26, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydiner, A.S.; Tatoglu, E.; Bayraktar, E.; Zaim, S. Information system capabilities and firm performance: Opening the black box through decision-making performance and business-process performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M. The future of manufacturing industry: A strategic roadmap toward Industry 4.0. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 29, 910–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, F.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, F.; Yin, Q.; Ni, X. The architecture of cloud maufacturing and its key technologies research. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing and Intelligence Systems, Beijing, China, 15–17 September 2011; pp. 259–263. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Song, C.; Ji, Y.; Shih, M.-W.; Lu, K.; Zheng, C.; Duan, R.; Jang, Y.; Lee, B.; Qian, C.; et al. Toward Engineering a Secure Android Ecosystem. ACM Comput. Surv. 2016, 49, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalenogare, L.S.; Benitez, G.B.; Ayala, N.F.; Frank, A.G. The expected contribution of Industry 4.0 technologies for industrial performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 204, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manavalan, E.; Jayakrishna, K. A review of Internet of Things (IoT) embedded sustainable supply chain for industry 4.0 requirements. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 127, 925–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, J.L.C.; Wu, J.; Long, C.; Lin, Y.-B. Ubiquitous and Low Power Vehicles Speed Monitoring for Intelligent Transport Systems. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 5656–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, H. Smart Grid. Encycl. Sustain. Technol. 2017, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Gattullo, M.; Scurati, G.W.; Fiorentino, M.; Uva, A.E.; Ferrise, F.; Bordegoni, M. Towards augmented reality manuals for industry 4.0: A methodology. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2019, 56, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punithavathi, P.; Geetha, S.; Karuppiah, M.; Islam, S.H.; Hassan, M.M.; Choo, K.-K.R. A lightweight machine learning-based authentication framework for smart IoT devices. Inf. Sci. 2019, 484, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.; Mussomeli, A.; Laaper, S.; Hartigan, M.; Sniderman, B. The smart Factory. Responsive, adaptive, connected manufacturing. Deloitte 2014, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kimani, K.; Oduol, V.; Langat, K. Cyber security challenges for IoT-based smart grid networks. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2019, 25, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.G.; Dalenogare, L.S.; Ayala, N.F. Industry 4.0 technologies: Implementation patterns in manufacturing companies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 210, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A.; Sokolov, B.; Werner, F.; Ivanova, M. A dynamic model and an algorithm for short-term supply chain scheduling in the smart factory industry 4.0. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrifoglio, R.; Cannavale, C.; Laurenza, E.; Metallo, C. How emerging digital technologies affect operations management through co-creation. Empirical evidence from the maritime industry. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 28, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, H.; Baines, T.; Smart, P. The servitization of manufacturing: A systematic literature review of interdependent trends. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 33, 1408–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyingyong, V.; Olsson, R.; Cho, J.-W.; Hidell, M.; Sjodin, P. IoT-Grid: IoT Communication for Smart DC Grids. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Washington, DC, USA, 4–8 December 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Herrojo, C.; Paredes, F.; Mata-Contreras, J.; Martín, F. Chipless-RFID: A review and recent developments. Sensors 2019, 19, 3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, L.; Dehe, B. Defining and assessing industry 4.0 maturity levels-case of the defence sector. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 29, 1030–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulloni, V.; Donelli, M. Chipless RFID Sensors for the Internet of Things: Challenges and Opportunities. Sensors 2020, 20, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, B.; Yoon, J.S.; Um, J.; Suh, S.H. The architecture development of Industry 4.0 compliant smart machine tool system (SMTS). J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 1837–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landaluce, H.; Arjona, L.; Perallos, A.; Falcone, F.; Angulo, I.; Muralter, F. A Review of IoT Sensing Applications and Challenges Using RFID and Wireless Sensor Networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.N.; Le Tuan, L.; Tuan, M.N.D. Smart-building management system: An Internet-of-Things (IoT) application business model in Vietnam. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 141, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadechkar, A.; Riba, J.-R.; Moreno-Eguilaz, M.; Perez, J. SmartConnector: A Self-Powered IoT Solution to Ease Predictive Maintenance in Substations. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 11632–11641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, H.; Bajwa, I.S.; Amin, R.U.; Sarwar, N.; Jamil, N.; Malik, M.G.A.; Mahmood, A.; Shafi, U. An IoT-Based Intelligent Wound Monitoring System. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 144500–144515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Junior, A.; Casas, J.; Marques, C.; Pontes, M.J.; Frizera, A. Application of Additive Layer Manufacturing Technique on the Development of High Sensitive Fiber Bragg Grating Temperature Sensors. Sensors 2018, 18, 4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, J.P. Temperature sensor characteristics and measurement system design. J. Phys. E Sci. Instrum. 1984, 17, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.D.; Merken, P.; Vandewal, M. Enhanced Accuracy of CMOS Smart Temperature Sensors by Nonlinear Curvature Correction. Sensors 2018, 18, 4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herter, J.; Wunderlich, V.; Janeczka, C.; Zamora, V. Experimental Demonstration of Temperature Sensing with Packaged Glass Bottle Microresonators. Sensors 2018, 18, 4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Lu, Z.; He, Q.; Lv, P.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, H. Research on the Temperature Characteristics of the Photoacoustic Sensor of Glucose Solution. Sensors 2018, 18, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; Kimura, S. Plant temperature sensors. Sensors 2018, 18, 4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J. Self-Calibration and Performance Control of MEMS with Applications for IoT. Sensors 2018, 18, 4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, G.; Dou, Y.; Chang, X.; Chen, Y.; Ma, C. Design and Performance Analysis of a Multilayer Sea Ice Temperature Sensor Used in Polar Region. Sensors 2018, 18, 4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monea, B.F.; Ionete, E.I.; Spiridon, S.I.; Ion-Ebrasu, D.; Petre, A.E. Carbon Nanotubes and Carbon Nanotube Structures Used for Temperature Measurement. Sensors 2019, 19, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, W.P.; Smith, J.H. Micromachined pressure sensors: Review and recent developments. Smart Mater. Struct. 1997, 6, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, K.A.; Kulkarni, S.M. Investigation on Influence of Geometry on Performance of a Cavity-less Pressure Sensor. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 417, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessarolo, M.; Possanzini, L.; Campari, E.G.; Bonfiglioli, R.; Violante, F.S.; Bonfiglio, A.; Fraboni, B. Adaptable pressure textile sensors based on a conductive polymer. Flex. Print. Electron. 2018, 3, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, B.; Shu, L.; Tao, X.-M. Flexible pressure sensors for smart protective clothing against impact loading. Smart Mater. Struct. 2013, 23, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.M.; Sohaib, M.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.-M. Crack Classification of a Pressure Vessel Using Feature Selection and Deep Learning Methods. Sensors 2018, 18, 4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, R.V.; Sokolov, O.V.; Bichurin, M.I.; Petrova, A.R.; Bozhkov, S.; Milenov, I.; Bozhkov, P. Strength of multiferroic layered structures in position sensor structures. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 939, 012058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gödecke, M.L.; Bett, C.M.; Buchta, D.; Frenner, K.; Osten, W. Optical sensor design for fast and process-robust position measurements on small diffraction gratings. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2020, 134, 106267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.J.; Carr, A.R.; Charkhabi, S.; Furnish, M.; Beierle, A.M.; Reuel, N.F. Wireless position sensing and normalization of embedded resonant sensors using a resonator array. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 303, 111853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-A.; Kim, J.W.; Kang, C.-S.; Lee, J.Y.; Jin, J. On-machine calibration of angular position and runout of a precision rotation stage using two absolute position sensors. Measurement 2020, 153, 107399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helseth, L.E. On the accuracy of an interdigital electrostatic position sensor. J. Electrost. 2020, 107, 103480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, S.; Zheng, P.; Huang, Z.; Luo, X. Investigation into position deviation effect on micro newton force sensor. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkun, A.; Mishakov, G.; Sharkov, A.; Demikhov, E. The use of a piezoelectric force sensor in the magnetic force microscopy of thin permalloy films. Ultramicroscopy 2020, 217, 113072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastro, A.; Ferrari, M.; Ferrari, V. Double-actuator position-feedback mechanism for adjustable sensitivity in electrostatic-capacitive MEMS force sensors. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 312, 112127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeman, J.O.; Sheil, B.B.; Sun, T. Multi-axis force sensors: A state-of-the-art review. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 304, 111772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, B.; Fatikow, S. Recent advances in non-contact force sensors used for micro/nano manipulation. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2019, 296, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K.; Kratz, H.; Nguyen, H.; Thornell, G. A highly integratable silicon thermal gas flow sensor. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2012, 22, 65015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, A.; Soler, G.J.; DiLuna, M.L.; Grant, R.A.; Zaveri, H.P.; Hoshino, K. A passive, biocompatible microfluidic flow sensor to assess flows in a cerebral spinal fluid shunt. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 312, 112110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekraoui, A.; Hadjadj, A. Thermal flow sensor used for thermal mass flowmeter. Microelectron. J. 2020, 103, 104871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejeian, F.; Azadi, S.; Razmjou, A.; Orooji, Y.; Kottapalli, A.; Warkiani, M.E.; Asadnia, M. Design and applications of MEMS flow sensors: A review. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2019, 295, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cho, H.; Han, S.-I.; Han, A.; Han, K.-H. A disposable microfluidic flow sensor with a reusable sensing substrate. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 288, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, A.B. Size Matters: Problems and Advantages Associated with Highly Miniaturized Sensors. Sensors 2012, 12, 3018–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xing, F.; Chu, D.; Liu, Z. High-Accuracy Self-Calibration for Smart, Optical Orbiting Payloads Integrated with Attitude and Position Determination. Sensors 2016, 16, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkel, M. Smart MEMS: Micro-structures with error-suppression and self-calibration control capabilities. Proc. Am. Control Conf. 2001, 2, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, J.; Yan, D.; Liu, Q.; Xu, K.; Zhao, J.L.; Shi, R.; Wei, L.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X. ManuChain: Combining Permissioned Blockchain With a Holistic Optimization Model as Bi-Level Intelligence for Smart Manufacturing. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Ruan, G.; Jiang, P.; Xu, K.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Liu, C. Blockchain-empowered sustainable manufacturing and product lifecycle management in industry 4.0: A survey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 132, 110112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).