Abstract

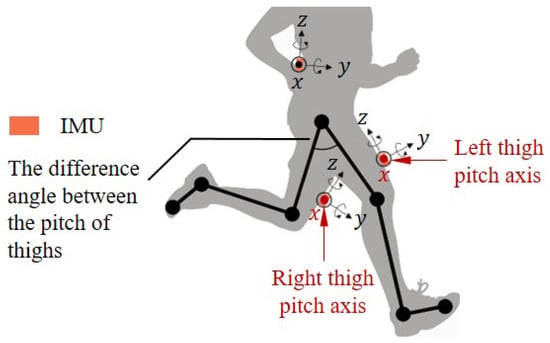

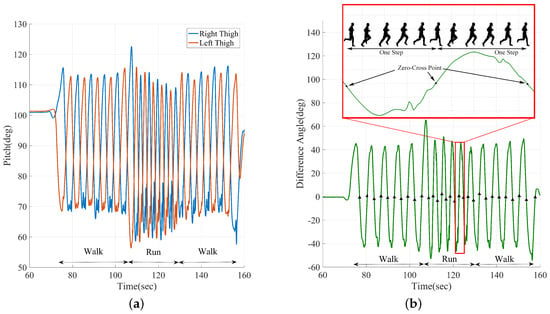

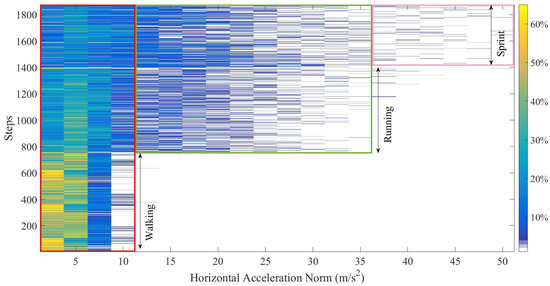

The combination of biomechanics and inertial pedestrian navigation research provides a very promising approach for pedestrian positioning in environments where Global Positioning System (GPS) signal is unavailable. However, in practical applications such as fire rescue and indoor security, the inertial sensor-based pedestrian navigation system is facing various challenges, especially the step length estimation errors and heading drift in running and sprint. In this paper, a trinal-node, including two thigh-worn inertial measurement units (IMU) and one waist-worn IMU, based simultaneous localization and occupation grid mapping method is proposed. Specifically, the gait detection and segmentation are realized by the zero-crossing detection of the difference of thighs pitch angle. A piecewise function between the step length and the probability distribution of waist horizontal acceleration is established to achieve accurate step length estimation both in regular walking and drastic motions. In addition, the simultaneous localization and mapping method based on occupancy grids, which involves the historic trajectory to improve the pedestrian’s pose estimation is introduced. The experiments show that the proposed trinal-node pedestrian inertial odometer can identify and segment each gait cycle in the walking, running, and sprint. The average step length estimation error is no more than 3.58% of the total travel distance in the motion speed from 1.23 m/s to 3.92 m/s. In combination with the proposed simultaneous localization and mapping method based on the occupancy grid, the localization error is less than 5 m in a single-story building of 2643.2 m.

1. Introduction

The inertial pedestrian navigation system has a wide range of applications in hotspots such as firefighting, indoor security, tunnel patrols, and other fields. These practical applications typically require pedestrians to repeatedly move vigorously in the same indoor environment, such as running and sprint, rather than just regular walking. The reliable navigation information can guarantee the smooth execution of tasks and the safety of personnel in these fields. Although great progress has been made in recent years, there remain various challenging problems such as unbounded accumulative heading error and the capability in dealing with the drastic motions.

The zero-velocity update (ZUPT) algorithm has been widely applied in the field of inertial pedestrian navigation because it is suitable for the foot-mounted IMU case to compensate for traveled distance error during normal walking by introducing heuristic periodic zero velocity corrections [1]. In addition, a method fusing the navigation information of dual foot-mounted ZUPT-aided INSs was proposed [2]. This method is based on the intuition that the distance of separation between right and left foot INSs cannot be longer than a quantity known as foot-to-foot maximum separation. Shi improved the foot-to-foot maximum separation model and advanced an ellipsoid model [3].

This mechanism considers the separation constraints both in horizontal and vertical directions, which is more effective to correct the pedestrian height error. Since these methods require a long enough period of stationary time for the foot to recognize the stationary state, correct for velocity and attitude errors, and apply the separation constraints. During running and sprint, however, this stationary time is very short or even non-existent. Therefore, these methods cannot achieve the same positioning accuracy in running and sprint as in normal walking.

Another pedestrian inertial navigation method is the pedestrian dead reckoning method (PDR), which estimates the pedestrian’s step length and heading, and performs dead reckoning to track the pedestrian’s position. However, with the current state of the art of MEMS technology, the accuracy of accelerators and gyroscopes are not good enough for deriving step length and heading estimation over longer terms due to their large biases and scale factors.

Several mathematical models for indirect stride/step length estimation in the PDR algorithm. Compared with ZUPT, the indirect stride/step length estimation could restrain the accumulated error caused by the measurement noise of inertial devices after integration.

The inverted pendulum model is widely used to estimate step length in these PDR systems [4]. The geometric construction among leg length, waist vertical displacement, and step length are considered. However, the basic assumption that there always at least one foot on the ground during pedestrian movement is valid in drastic movement. The more complex models are mostly based on the statistic correlation between the step length and the acceleration of the pedestrian. For instance, the linear relation of acceleration variance, step frequency, and step length [5], and the nonlinear model between step length and maximum and minimum value of acceleration in each step [6]. These step length estimation techniques fitted the statistic features and step length in a small range, but would cause large step length error during hybrid speed motion.

As for head estimation error correction, combining both gyroscope and magnetometer inputs has yielded some success since the two sensors have complementary error characteristics—gyroscopes give poor long-term orientation, while magnetometers are subject to short-term [7,8,9]. Nevertheless, the geomagnetic field is badly disturbed by magnetic disturbances from indoor iron structures and electronic equipment. Another approach is heuristic drift reduction (HDR), assuming that many man-made walkways have straight-line features. The HDR method estimates the likelihood that the user is walking along a straight line [10,11]. If that likelihood is high, HDR applies a correction to the gyro output that would result in a reduction of drift if indeed the user was walking along a straight line. Although HDR doesn’t require landmarks to be known in advance, the basic assumption is too restrictive for complex irregular layout buildings.

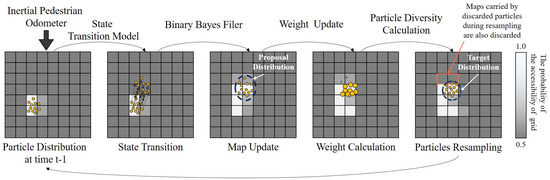

Map matching could correct not only the heading estimation but also position estimation [12,13,14]. The use of environmental knowledge imposes boundary constraints on a user’s predicted motion. By using a particle filter algorithm, sub-meter tracking accuracy was achieved. However, a significantly increased amount of information needs to be provided as prior knowledge of the system for the particle filter to be effective. Robertson proposed a new Bayesian estimation approach for simultaneous mapping and localization for pedestrians based on the odometer with foot-mounted inertial sensors, called “FootSLAM”, in which the long term inertial position error is corrected efficiently using the built map of the explored area, especially when this area is revisited over time [15]. Based on FootSLAM, a series of simultaneous mapping and localization methods for pedestrians that combining the map with other information are developed. Such as Wi-SLAM [16], PlaceSLAM [17], MagSLAM [18], and SignalSLAM [19]. Moreover, Hardegger presented another kind of simultaneous mapping and localization algorithm for pedestrians using inertial sensors based on semantic landmark called ActionSLAM [20]. This method is a specific instantiation of the FastSLAM framework optimized to operate with action landmarks like open/close door, reading, brushing teeth, etc. Hardegger expanded the application of this method in different ways. [21] presented a 3D version of ActionSLAM and [22] developed a unified Bayesian framework for ActionSLAM.

The occupancy grid map is an important representation model in the mobile robot environment mapping application, proposed by Moravec and Elfes [23]. This model divides the environment where the robot is located into several neat grids and extracts the status of each grid to determine the environmental accessibility. In recent years, the FastSLAM method based on the occupancy grid using a laser range sensor has been widely applied in the field of robotic navigation. This method uses a laser range sensor to perceive the external environment and estimate the occupancy grid map of the environment. By utilizing the constructed map, the algorithm can effectively correct the positioning error of the robot. However, considering the size and cost of laser range sensors, it is not suitable for pedestrian positioning applications. For this reason, this paper proposes to construct a virtual range sensor using the inertial odometer information to sense the accessible area in the environment and construct the occupancy grid map to deal with the accumulated error of the inertial odometer.

To enhance the capability of the inertial pedestrian navigation system in dealing with the drastic motions and address the unbounded accumulated positioning error, this paper proposed a triple-node IMUs pedestrian inertial navigation system with an occupancy grid-based FastSLAM algorithm. The triple-node IMUs are composed of one waist-worn IMU and two thighs-worn IMUs. The thighs-worn IMUs are utilized to detect and segment the gait. To estimate the step length accurately for drastic motions, we introduce the horizontal acceleration probability distribution function into a step length estimation process to address the issue that the statistic feature fitting method cannot deal with drastic motion with a large speed range. Furthermore, we construct a virtual range sensor to precept the external environment and introduce it into an occupancy grid-based FastSLAM algorithm to correct the long-term position error of the inertial odometer.

This paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, the wearable trinal-IMUs pedestrian navigation system is described. The inertial simultaneous localization and occupancy grid mapping is discussed in Section 3. Analysis of both experiments and results is given in Section 4. Finally, the conclusions and future work are summarized in Section 5.

4. Results

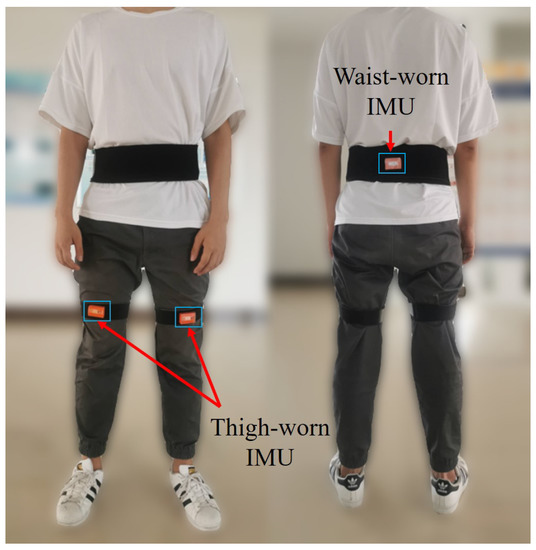

To validate the application effect of the proposed inertial pedestrian occupancy grid-based FastSLAM, several different experiments were conducted on different testers. As illustrated in Figure 7, three MTw (Xsens) inertial measurement units were attached to the pedestrian’s thighs and waist. The six-axis inertial data of each sensor were output at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz. The inertial information was recorded in a laptop during the test and post-processed by the software developed in MATLAB environment according to the algorithm presented above.

Figure 7.

Illustration of the trinal-IMU pedestrian navigation system sensors deployment.

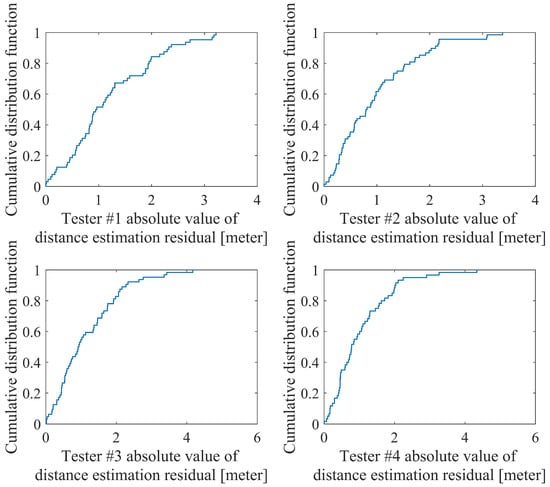

4.1. Validation of the Step Length Estimation for Drastic Motions

The first test was designed to verify whether the proposed step length estimation method was suitable enough for regular walking, running, and sprint motions. Four testers, including two males and females, were asked to walk, run, and sprint along a 55.8 m straight track at least 12 times for each motion. After calculating the step length estimation parameters for each tester, the cumulative distribution function of the absolute value of the distance estimation residual is shown in Figure 8. The root mean square error of each step length estimation in this process is shown in Table 1. In Figure 8, 93.8%, 95.6%, 92.2%, and 95.0% of the four pedestrian’s different motions absolute distance estimation residuals are in the range of [–3 m,3 m] (5% of 55.8 m). In addition, it can be seen from Table 1 that the proposed method has better adaptability to higher speed motion under the premise of obtaining average accuracy under low-speed motion and the characteristics of the distribution of the residuals of the step length estimates for each step are generally consistent with a Gaussian distribution. Therefore, in the state transition Equation (23), the Gaussian distribution can be used to describe the noise characteristics of the step length control vector.

Figure 8.

The cumulative distribution function of absolute value of distance estimation residual.

Table 1.

Step length estimation RMS error of three models.

These results indicate that it is applicable to utilize the proposed method to estimate the step length both in walking, running, and sprint motions. Once the parameters are determined in the initialization procedure, for example, walking along a track in different motions, the step length can be estimated in real-time.

4.2. Evaluation of the Occupancy Grid-Based FastSLAM for Inertial Pedestrian Navigation

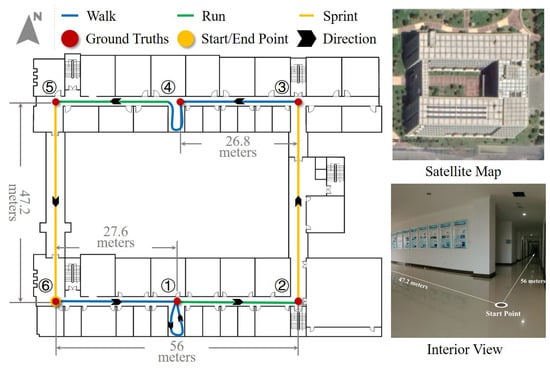

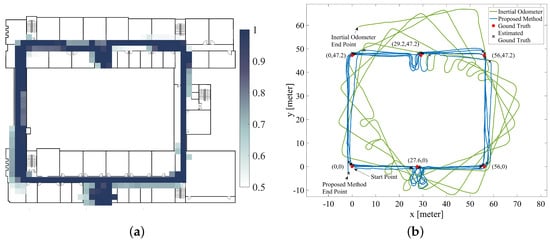

In order to evaluate the occupancy grid-based FastSLAM for inertial pedestrian navigation algorithm, the indoor experiments were conducted in a rectangular area of the building in Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics. As shown in Figure 9, the route is 1083.5 m long and includes two-room walking path. The starting position and ending position are the same point. We select six turners with prior position information as ground truth points to assess the pedestrian position error. Testers were asked to move along the pre-established route five laps in hybrid motion modes, including normal walking, running, and sprint, as illustrated in Figure 9. In this test, 500 particles are selected, and the edge length of the grid is 2 m.

Figure 9.

The occupancy grid-based FastSLAM experiment environment and designed path.

Figure 10a presents the estimated occupancy gird map using the proposed method. The colored grid is the normalized result of the sum of the probability maps carried by all the particles, with white indicating the probability that the grid is passable is 0.5, and dark blue indicating the probability that the grid is passable is 1. Figure 10b compares the estimated trajectory from the inertial odometer (blue line) and the estimated trajectory from the proposed SLAM method (green line). It should be noted that the green curve is the expected distribution of all particles at each moment, rather than the final posterior distribution of all pedestrian pose sequences as shown by most SLAM methods. In other words, once time t is experienced, the expected position in the graph at time t will not change due to the subsequent optimization process. The reason we do this is that in most scenarios the user is most concerned with the accuracy of navigation at the moment. The expectation of posterior distribution of posture at all final moments after optimization has a smaller error than the above method, which may mislead the researchers’ evaluation of the navigation system.

Figure 10.

(a) inertial occupancy grid-based FastSLAM map; (b) the trajectory of inertial pedestrian odometer and the trajectory of inertial pedestrian odometer integrated with occupancy grid-based FastSLAM.

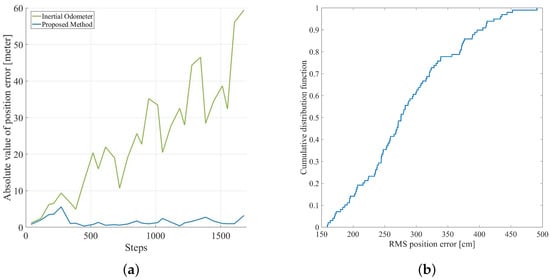

The tester was asked to go through some ground truths mentioned above; during the test, the tester recorded the number of steps taken before the moment through ground truths. The estimation of the position of these ground truths is shown in the black cross in the figure; meanwhile, the red circles indicate the true position of the ground truths. Figure 11a illustrates some of the main characteristics of the positioning error and the number of times pedestrian passes the ground truths, in which the positioning error of the inertial odometer (green line) accumulated over time and the positioning error of proposed inertial occupancy gird-based FastSLAM is always kept at a low level. The final absolute return position error is 59.41 m and 3.22 m, respectively, and the relative error is 5% and 0.3%, respectively.

Figure 11.

(a) the absolute value of position error of inertial pedestrian odometer and inertial pedestrian odometer integrated with occupancy grid-based FastSLAM; (b) the RMS position error cumulative distribution of inertial pedestrian odometer integrated with occupancy grid-based FastSLAM.

In order to eliminate the influence of the Monte Carlo particle sampling randomness to the location result, we have processed the above data 100 times, and the cumulative distribution of the RMS position error between the trajectory and the ground truths are shown in Figure 11b. It can be seen from the graph that the probability of average error less than 4 m is 89.9%.

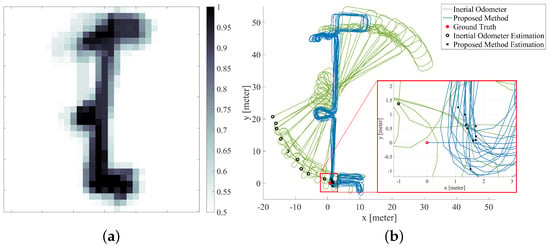

The second experimental scenario is a random walk in multiple rooms. The experimental route consisted of multiple turns, which posed a challenge for heading estimation. The tester was asked to walk around the multiple rooms randomly, and return to the starting point after every certain time. We used the starting point as ground truth to evaluate the positioning accuracy of the system. The parameter settings of the system remained the same as in the previous experiment.

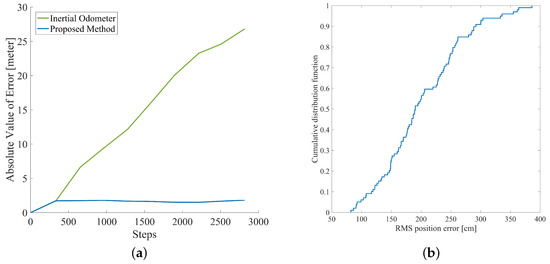

Figure 12a shows the map constructed by the proposed method based on the testers’ movements. Figure 12b compares the estimates of pedestrian trajectories from the inertial odometer and the proposed method. The green line shows the positioning results of the inertial odometer and the blue line shows the positioning results of the proposed method. It can be seen that the heading of the inertial odometer gradually diverges, while the heading estimate of the proposed method is very stable. The red point is the starting point of navigation and also the ground-truth of the path, the black circle indicates the ground truth estimate of the inertial odometer, and the black cross indicates the ground truth estimate of the proposed method. The variation of the RMS ground truth estimation error over time is shown in Figure 13a, where the green line is the absolute value of the ground truth estimation error of the inertial odometer, and the proposed method corresponds to the blue line. It can be seen that the positioning error of the proposed method does not increase with time, effectively eliminating the cumulative error of the inertial odometer.

Figure 12.

(a) inertial occupancy grid-based FastSLAM map; (b) the trajectory of inertial pedestrian odometer and the trajectory of inertial pedestrian odometer integrated with occupancy grid-based FastSLAM.

Figure 13.

(a) the absolute value of position error of inertial pedestrian odometer and inertial pedestrian odometer integrated with occupancy grid-based FastSLAM; (b) the RMS position error cumulative distribution of inertial pedestrian odometer integrated with occupancy grid-based FastSLAM.

Similarly, in order to eliminate the influence of the randomness of Monte Carlo particle sampling on the localization results, we processed this data set 100 times, and the cumulative distribution function of the RMS position error is shown in Figure 13b; the proposed method has an error of less than 3.36 m at a 95.96% confidence interval.

5. Discussion

The main purpose of this study is to develop a multi-IMU inertial pedestrian odometer integrating with the occupancy grid-base FastSLAM approach to improve the performance of the inertial pedestrian navigation system on drastic motions. The traditional PDR based inertial pedestrian navigation system has advantages including no additional infrastructure needed and no radio frequency interference but has disadvantages including the inaccurate step length estimation on drastic motions such as running and sprint, and unbounded error on heading estimation. We suggested a simple step detection and segment approach by detecting the zero-crossing of the pitch of thighs. Meanwhile, a step length estimation method for drastic motion based on the pdf of the waist-worn horizontal acceleration norm is proposed. These two methods together constitute an inertial pedestrian odometer adapted to drastic motions. The experiments on different testers on different speed motions indicate that the proposed inertial pedestrian odometer can provide the step length estimation with the same precision as the slow one when the pedestrian is moving fast. Moreover, we extended the occupancy grid-based FastSLAM algorithm to the inertial navigation system. By constructing a virtual range observer, the simultaneous positioning and mapping of pedestrians can be realized by relying on inertial odometer without any additional sensors. The experiment results indicate that the proposed inertial occupancy grid-based FastSLAM can accurately construct the map of the passable area, and the system can effectively restrain the course error divergence of pedestrian inertia odometer. This method can provide long-term and high-precision pedestrian positioning information without increasing the cost, which is of great significance for the practical application of pedestrian inertial navigation.

The proposed method can improve the long-term accuracy of inertial pedestrian navigation system. However, there are still some limitations in this study. Firstly, the inertial occupancy grid-based FastSLAM utilizes the historic trajectory information to correct the positioning and heading error which means that the position and heading errors are corrected only when the pedestrian revisits the area they have already visited. Secondly, the determination of the initial position is not considered in this study. We focus on solving the issue of accumulative error rather than the initial position. Nevertheless, according to the basic principles of inertial navigation, the initial position error will be gradually coupled to the attitude estimation. On the one hand, it will lead to an increase of course estimation error; on the other hand, it will lead to inaccurate waist attitude estimation, which will affect the step length estimation, which limits the application of the system in larger areas.

For the first limitation, we can use the historical trajectory of multiple people to correct map estimation and user location estimation by studying the method of multi-pedestrian collaborative SLAM. For the second limitation, the combination of GPS and the inertial system can be used to obtain the absolute position of pedestrians through the satellite navigation system before they enter the blocked area of the satellite.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a triple-node IMU inertial pedestrian odometer which improves the accuracy of inertial pedestrian localization in dealing with drastic motions. Compared to the traditional PDR system, the proposed approach can provide the step length estimation with the same precision as normal walking when the pedestrian is running or sprinting. Moreover, we extended the occupancy grid-based FastSLAM, which is commonly used in a vision-based navigation system, to the inertial pedestrian navigation by constructing a virtual range sensor to precept the external environment. The combination of these two methods could estimate step length accurately and eliminate the accumulated positioning error of the inertial pedestrian odometer. Less than 5 m positioning accuracy in a single-story building of 2643.2 is achieved. In future work, we plan to extend the single inertial occupancy grid-based FastSLAM method to the multi-pedestrian collaborative SLAM method.

Author Contributions

Y.D. designed the study, performed the research, analysed data, and wrote the paper. Z.X. supervised the paper, discussed the results and revised the manuscript. W.L. performed the experiments and revised the manuscript. Z.C. performed the experiments and analysed data. Z.W. performed the experiments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by special zones for National Defense Science and Technology innovation, in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 61673208, Grant 61533008, Grant 61533009, and Grant 61703208), in part by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province under Grant BK20181291, Grant BK20170815, and Grant BK20170767, and in part by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities under Grant NP2018108 and Grant NZ2019007.)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Foxlin, E. Pedestrian tracking with shoe-mounted inertial sensors. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2005, 25, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girisha, R.; Prateek, G.V.; Hari, K.; Handel, P. Fusing the navigation information of dual foot-mounted zero-velocity-update-aided inertial navigation systems. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Signal Processing and Communications (SPCOM), Bangalore, India, 22–25 July 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y. Dual MIMU Pedestrian Navigation by Inequality Constraint Kalman Filtering. Sensors 2017, 17, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousdar Ahmed, D.; Munoz Diaz, E. Loose Coupling of Wearable-Based INSs with Automatic Heading Evaluation. Sensors 2017, 17, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Chen, R.; Chen, Y.; Kuusniemi, H.; Wang, J. An effective Pedestrian Dead Reckoning algorithm using a unified heading error model. In Proceedings of the PLANS 2010: IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium, Indian Wells, CA, USA, 4–6 May 2010; pp. 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Antsaklis, P.; Montestruque, L.; McMickell, M.; Lemmon, M.; Sun, Y.; Fang, H.; Koutroulis, I.; Haenggi, M.; Xie, M.; et al. Design of a Wireless Assisted Pedestrian Dead Reckoning System—The NavMote Experience. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2005, 54, 2342–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D.; Meng, X.L.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, Z.Q. Fusion of Inertial/Magnetic Sensor Measurements and Map Information for Pedestrian Tracking. Sensors 2017, 17, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Qin, K.; Li, Z.; Hu, H. Inertial/magnetic sensors based pedestrian dead reckoning by means of multi-sensor fusion. Inf. Fusion 2018, 39, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cheng, M.; Noureldin, A.; Guo, Z. Research on the improved method for dual foot-mounted Inertial/Magnetometer pedestrian positioning based on adaptive inequality constraints Kalman Filter algorithm. Measurement 2019, 135, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizzo, G.; Ren, L. Position Tracking During Human Walking Using an Integrated Wearable Sensing System. Sensors 2017, 17, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J. Waist mounted Pedestrian Dead-Reckoning system. In Proceedings of the 2012 9th International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots and Ambient Intelligence (URAI), Daejeon, Korea, 26–28 November 2012; pp. 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Liu, K.C.; Cheng, H.C.; Hsu, S.J.; Chan, C.T. Multi-Sensor Fusion Approach for Improving Map-Based Indoor Pedestrian Localization. Sensors 2019, 19, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perttula, A.; Leppakoski, H.; Kirkko-Jaakkola, M.; Davidson, P.; Collin, J.; Takala, J. Distributed Indoor Positioning System With Inertial Measurements and Map Matching. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2014, 63, 2682–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascher, C.; Kessler, C.; Weis, R.; Trommer, G. Multi-floor map matching in indoor environments for mobile platforms. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Sydney, Australia, 13–15 November 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermann, M.; Robertson, P. FootSLAM: Pedestrian Simultaneous Localization and Mapping Without Exteroceptive Sensors-Hitchhiking on Human Perception and Cognition. Proc. IEEE 2012, 100, 1840–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, L.; Robertson, P. WiSLAM: Improving FootSLAM with WiFi. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation, Guimarães, Portugal, 21–23 September 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, P.; Angermann, M.; Khider, M. Improving Simultaneous Localization and Mapping for Pedestrian Navigation and Automatic Mapping of Buildings by Using Online Human-Based Feature Labeling. In Proceedings of the PLANS 2010: IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium, Indian Wells, CA, USA, 4–6 May 2010; pp. 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frassl, M.; Angermann, M.; Lichtenstern, M.; Robertson, P.; Julian, B.J.; Doniec, M. Magnetic maps of indoor environments for precise localization of legged and non-legged locomotion. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013; pp. 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirowski, P.; Ho, T.K.; Saehoon, Y.; MacDonald, M. SignalSLAM: Simultaneous localization and mapping with mixed WiFi, Bluetooth, LTE and magnetic signals. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation, Montbeliard, France, 28–31 October 2013; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardegger, M.; Roggen, D.; Mazilu, S.; Troster, G. ActionSLAM: Using location-related actions as landmarks in pedestrian SLAM. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Sydney, Australia, 13–15 November 2012; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardegger, M.; Roggen, D.; Tröster, G. 3D ActionSLAM: Wearable person tracking in multi-floor environments. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2015, 19, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardegger, M.; Roggen, D.; Calatroni, A.; Tröster, G. S-SMART: A Unified Bayesian Framework for Simultaneous Semantic Mapping, Activity Recognition, and Tracking. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2016, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravec, H.; Elfes, A. High resolution maps from wide angle sonar. In Proceedings of the 1985 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, St. Louis, MO, USA, 25–28 March 1985; pp. 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).