Abstract

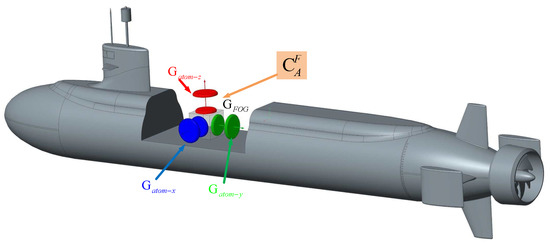

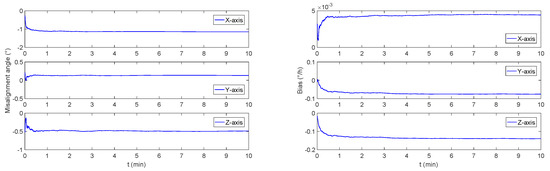

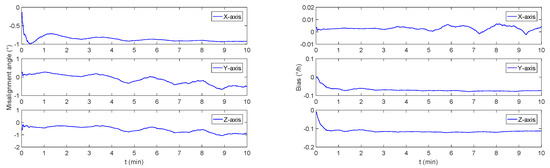

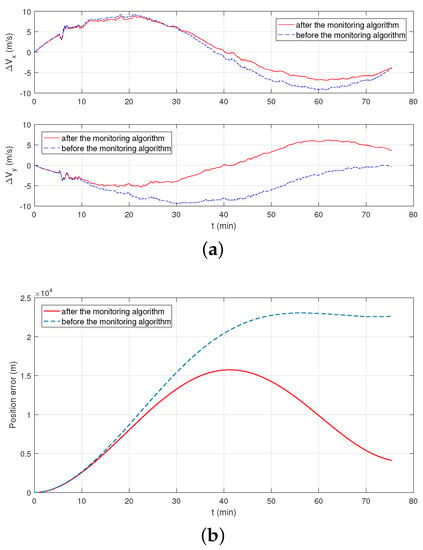

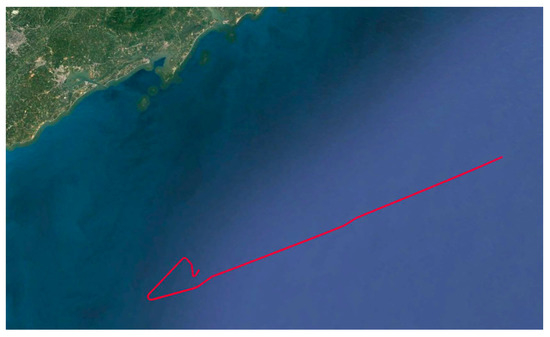

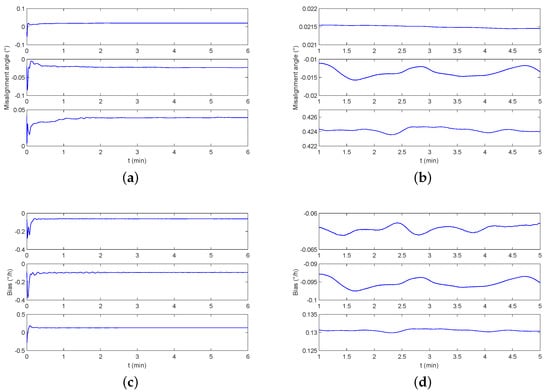

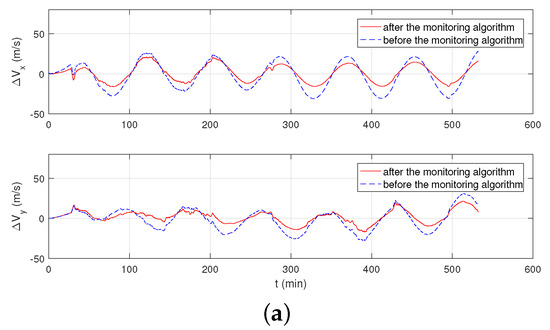

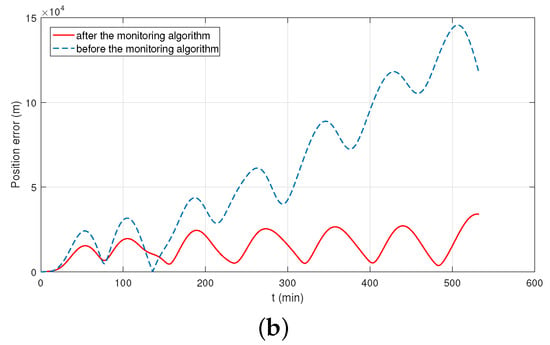

The implementation principle of a typical three-pulse cold atom interference gyroscope is introduced in this paper. Based on its configuration and current research status, the problems of cold atom interference gyro are pointed out. The data-rate is insufficient, and it is difficult to achieve high dynamic measurement. Then, based on these two limitations, a novel design of the monitoring navigation system of the cold atom interference gyroscope (CAIG) and an intermediate-grade inertial measurement unit (IMU) was proposed to obtain the long-term position result without GPS signals, such as the Inertial Navigation System (INS) in underwater vehicles. While the CAIG was used as the external gyro, the bias of IMU and the misalignment angle between the CAIG-frame and the IMU-frame are obtained through filtering technique. The simulation test and field test demonstrated the improvements of the long-term positioning accuracy of the INS.

1. Introduction

Due to its advantages of complete autonomy, undisturbed, large-amount of output information, and robust real-time performance, the Inertial Navigation System (INS) has irreplaceable benefits in both military and civilian fields, and the application requirements continue to promote the development of inertial sensors. Since the accuracy of gyroscopes and accelerometers directly affects the accuracy of positioning and attitude output of Strapdown Inertial Navigation Systems (SINSs) [1,2,3,4], the development of inertial navigation technology can approximately rely on the advance of two inertial sensor technologies, especially for the gyroscope.

The first-generation gyroscope is represented by electrostatic rate gyro and mechanical gyro [5,6,7]. At present, the bias stability of mechanical gyros is better than /h). The second-generation gyroscope is represented by the ring-laser gyroscope and the fiber-optic gyroscope (FOG), and the bias stability is better than h) [8,9]. As a representative of the newest generation of gyro, the cold atom interference gyroscope is based on the Sagnac effect of the atomic de Broglie wave, and its theoretical precision may reach h) [10]. Even though the current cold atomic gyro has many problems to be resolved from practical engineering applications, it has significant precision merits and considerable application prospects.

Since the first implementation of the atom-based interferometer at Stanford University in 1991 [11], atomic cooling and steering technology has developed rapidly. At present, with the atomic excitation, capture, manipulation, and the continuous reduction of the limit temperature of the atom cloud, atomic material wave related technologies have received extensive attention, and successively realized new prototypes such as atomic fountain clocks [12,13,14,15,16] and atomic gravimeters [17,18,19,20,21], have both surpassed the precision of traditional ones. It is worth noting that, due to the technology limitations, cold atom interferometers are mainly used for constant measurements, such as gravitation constants, local gravity, and measurement of basic physical constants [22,23,24,25,26]. Based on the measurement principle of CAIG, which is explained in Section 2, its dynamic measurement range is insufficient to perform a dynamic navigation test. In particular, the data-rate of CAIG cannot realize an independent inertial navigation system, and most of them are used to measure the earth’s rotation constant [10,27,28,29,30].

As the newest-generation sensor for rotation measurement, the CAIG with ultra-high precision potential leads to a breakthrough of IMUs, at the same time, it brings opportunities to solve long-term positioning problem of underwater vehicles without GPS signals. The CAIG‘s advantage lies in long-term stability, repeatability, and extremely high expected sensitivity. Unfortunately, its data-rate is too low to compose an INS till now. This insufficient data-rate will lead to algorithmic solution error. At the same time, the limited dynamic range of the CAIG cannot meet the requirement of accurately capturing the dynamic information of the carrier [31,32]. On the other hand, FOG is an advanced inertial sensor for rotation measurement of carriers. It obtains the advantages of high data-rate and large dynamic range. However, due to the limited improvement, the FOG cannot satisfy the long-term accuracy requirements in terms of bias stability and repeatability. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies about combining CAIG and FOG. In this paper, a novel monitoring navigation method for CAIG is proposed, and dedicated to combining the benefits of the CAIG and FOG to improve the positioning accuracy of the SINS. When the underwater vehicle is in a lower dynamic environment, the CAIG is used to estimate the bias of the FOG. Otherwise, a mature SINS of FOG is used for navigation in a highly dynamic environment. This monitoring navigation method with lower requirements of CAIG’s data rate, and the CAIG’s measurement accuracy is fully utilized under the limited dynamic range.

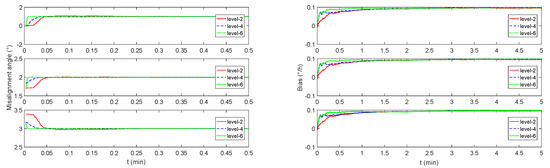

In Section 2, the configuration of the CAIG is introduced, and the reasons for the lack of dynamic measurement and the data rate are explained. In Section 3, the design of the monitoring navigation system is introduced, and simulation analysis in Section 4 shows the conditions to realize a fast and accurate monitoring system. Section 5 shows the results of land vehicle experiments and ship experiments, with a significant improvement of the positioning accuracy. In order to reduce the amount of calculation and visually show the effect of this monitoring system [33,34], the classic Kalman filter is chosen to obtain the optimal solution of the time-invariant linear system.

2. Three-Pulse Cold Atom Interferometer for Rotational Measurement

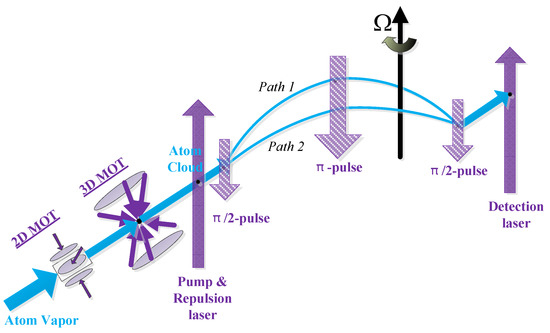

The configuration of the rotation measurement based on the cold atom interferometer mainly includes three-pulse design and four-pulse design. In order to easily realize the triaxial measurement, the three-pulse opposite projection configuration is selected as an example in this paper. As shown in Figure 1, the implementation of CAIG is mainly divided into atom cloud preparation, cooling, state selection, and velocity selection process, interference process, and final atomic state detection. Among them, the imprisonment and manipulation of the atom cloud are all realized by laser control technique, which requires a precise optical system for frequency, phase and light emphasizing. In order to achieve better measurement accuracy and reduce the influence of the external environment, we hope that the external environment of the atomic interference gyroscope achieves vacuum, low temperature, magnetic shielding, and vibration isolation.

Figure 1.

System implementation of cold atom interference gyroscope.

2.1. Atomic Cooling and Trapping Progress

In order to reduce the interference errors caused by the atom position error, velocity distribution and other factors to the interference result, the atom in the initial state of steam needs to be cooled to the extremely low temperature of the -level and trapped as an easy-to-manipulate atom cloud [35,36,37]. The existence time is prolonged through this progress.

When a precise laser illuminates an atom, as long as the oscillation frequency of the atom is equal to the frequency of the laser, the atom absorbs photons and undergoes a transition to reach an excited state. Depending on the principle of energy conservation, the momentum of the atom itself is greatly reduced. On the other hand, the atomic state in the excited state is extremely difficult to maintain, then it will also spontaneously radiate out photons. These photons are emitted to all directions. Accompanied by photon emission, the momentum of the atoms by further losses. In short, atomic cooling is the process by which the laser’s constant action on the atom slows it down. In the same way, we can achieve precise control of the velocity and direction of atoms through precise control of the laser, so-called the atomic manipulation [38].

In order to obtain a better signal-to-noise ratio, we should prepare the atom cloud to reach the magnitude of to atoms. As shown in Figure 1, vapor becomes an atomic cloud through the action of 2D-MOT and 3D-MOT. After the capture zone, the number of atom clouds is continuously reduced due to factors such as the diffusion of cold atom clouds and the collision of various cavity walls. Furthermore, when there is background atom gas in the vapor chamber, the probe light will emit a large amount of stray fluorescence, which will increase the background noise and decrease the signal-to-noise ratio.

In short, considering the importance of atom cloud preparation and its requirements, the atom cloud preparation process with high reliability is an important guarantee for achieving high precision of the atomic gyro. This is the reason why we use more time to get more atoms into the interference area, eventually led to a lower data rate of CAIG.

2.2. Atomic State-Selection Progress

In the process of atomic interference, the interference is usually selected to the D2 line of , so that the atom enters the specific cycle between the ground state and the excited state, and gives the rotation information according to the population of atoms in each energy state. To avoid the effects of stray atoms and to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, the progress of atomic state-selection is necessary [39].

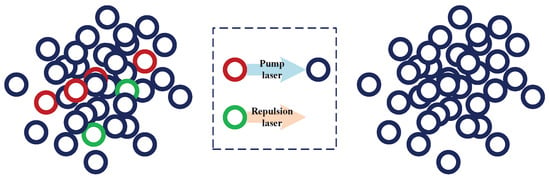

Depending on the complex energy state structure of , atoms at each state can only absorb the specific frequency and then transit to a excited state. The selected interference progress is between . Before the interference progress, the pump laser is used to transfer the available atoms of other energy levels , as is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Atomic state-selection Technique.

In addition, there are other atoms that will reduce the signal-to-noise ratio of the interference result due to changes in their sensitive magnetic fields. They are generally blown away by repulsion laser, and finally a pure atom cloud is obtained and trapped in a three-dimensional magneto-optical trap, and then they are ready to enter the interference region.

2.3. Atomic Interference Progress

In this section, a three-pulse interferometer is taken as an example to introduce the interference progress of CAIG. When the action laser is detuned to , the most simplified transition probability with the Raman frequency can be obtained by

It can be seen that the transition probability fluctuates with the laser duration t. When the duration of the pulse is , then half of the atoms will undergo state transition, and this pulse is called ‘-pulse’. The ‘-pulse’ is used as a splitter mirror in the optical interferometry. On the other hand, When the duration of the pulse is , then all of the atoms will undergo state transition, and this pulse is called ‘-pulse’. The ‘-pulse’ is used as a reflecting mirror in the optical interferometry. In the atomic interference region, three pairs of Raman laser are used as a splitter mirror, reflect mirror, and splitter mirror in the optical interferometry. In summary, we can control the atom cloud by controlling the Raman pulses to realize the atomic interferometer shown in Figure 1.

Interferometric gyroscopes [40], including optical interference gyros and cold atomic interference gyros, are based on the Sagnac effect, as shown in (2). The core issue of interferometric gyroscopes is to measure and separate the phase shift caused by the rotation.

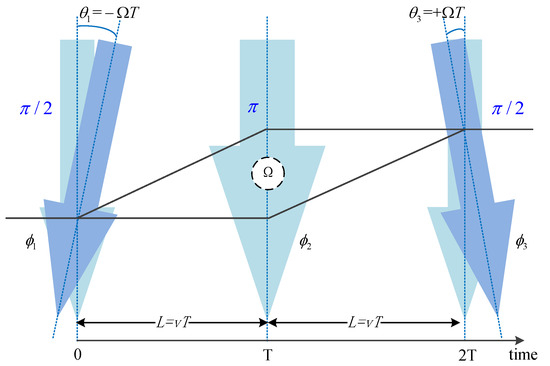

As shown in Figure 3, the phase shift caused by the rotation caused by the Doppler effect is

where is the phase from the ith pulse, , related to the wave vector , the atomic position , and the random phase of the pulse . Due to the Doppler effect, a slight deflection of the pulse occurs when the pulse acts on the atom, . When we ignore random phases, there are

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the Doppler effect.

When the actual rotation axis is not perpendicular to the interference plane, (5) is corrected into (6). Defining equivalent interference area , (5) is converted into . Therefore, the Doppler effect phase shift caused by rotation is equal to the Sagnac phase expression of (2), where ℏ is the reduced Planck constant. On the other hand, it can be seen that the interference area A is proportional to the square of the pulse interval time T, that is how the time domain atomic gyro increases its sensitivity.

Based on the above principle of rotation measurement, the output phase of the atomic gyro in the laboratory consists of several parts, as shown in (7).

where is the phase part caused by gravity, is the phase part caused by rotation, is the phase correction when gravity is not parallel to the actual rotation axis, and is the Random phase introduced by three pulses, .

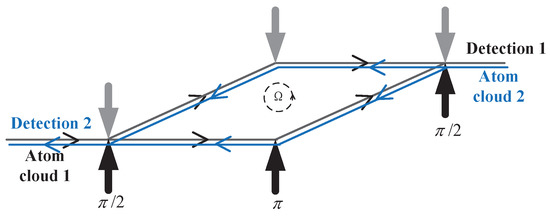

Typical dual interference loops with opposite-projectile atom clouds are shown in Figure 4, and we can get a phase shift from each loop. As shown in (8), we can process the two-loop data output to obtain the common mode part and the differential mode part.

Figure 4.

Dual interference loops with opposite-projectile atom clouds.

In two interference loops, the equivalent loop area vector . Then the phase shift related to the rotation is successfully extracted by

2.4. Fluorescence Detection Progress

After the interference process, the population of the atomic state is obtained by fluorescence detection progress [41]. The ratio of atoms in two ground state and is calculated and converted into the transition probability result of the interference process.

The absorption imaging technique is adopted here, and the fluorescence multiplier is received by the photomultiplier tube, and the total number of atoms at different energy states is obtained by time domain integration, in another word, the ratio of the population is obtained. In the specific implementation process, it is necessary to detect the laser light intensity and frequency to obtain precise control, and also needs to isolate stray light isolation, external temperature, and electromagnetic field isolation treatment.

It is worth noting that during the probing process, we need a unique and determined period from the conversion of the ratio of the population to the phase result . In order to achieve dynamic measurements, it is common to reduce the scale factor to obtain a larger range of interference phase result which is from larger angular velocity variations. In order to maintain the system accuracy of the cold atom interference gyroscope, only a small dynamic measurement range can be obtained, and it still cannot be independently used for the dynamic measurement.

6. Conclusions

The monitoring navigation system proposed in this paper can achieve an approximate stable estimation of gyro’s bias drift under general dynamic conditions, and compensated to the SINS to obtain a better positioning result. However, due to the defects of CAIG’s dynamic measurement range, it is still necessary to use FOG for navigation in a highly dynamic environment. With the further development of CAIG, the increase in data rate can further accelerate the monitoring estimation progress. Furthermore, a closer combination of FOG and CAIG can be realized, and a rough range of phases can be exactly realized by FOG to achieve high precision under high dynamics measuring.

Considering the current research status of cold atom interference gyroscopes, there are still some limitations in the sea test under this monitoring model. For example, the sampling rate will limit the timing and estimation effect of the position calibration after the monitoring process, and the data delay between the two gyros will directly affect the estimation error. Another important point is that the dynamic performance of the cold atom interference gyroscope is insufficient. Due to CAIG‘s accuracy is proportional to the scale factor, the higher measurement accuracy means a greater possibility that the phase results will appear on other interference stripes, and greatly affecting the measurement performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L.; Data curation, Q.L.; Formal analysis, L.Z.; Methodology, L.Z.; Project administration, W.G. and R.L.; Supervision, W.G.; Validation, R.L., Z.Y. and S.L.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51509063, 61503090, 51709068, 61573117,11674362), Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (Grant No. F2015031), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2018M631920), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. HIT.MKSTISP.2016 03), Postdoctoral Foundation of Heilongjiang Province Government (No. LBH-Z17094, LBH-Z17091), the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Hubei Province of China under Grant No. 2018CFA082, the National Defense Science and Technology Innovation Project of China and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAIG | Cold Atom Interference Gyroscope |

| FOG | Fiber-optic Gyroscope |

| INS | Inertial Navigation System |

| SINS | Strapdown Inertial Navigation System |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| PWCS | Piece-wise Constant Systems |

References

- Xia, X.W.; Sun, Q. Initial Alignment Algorithm Based on the DMCS Method in Single-Axis RSINS with Large Azimuth Misalignment Angles for Submarines. Sensors 2018, 18, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K. A Robust SINS/VO Integrated Navigation Algorithm Based on RHCKF for Unmanned Ground Vehicles. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 56828–56838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, F.; Gao, W.; Wang, Y. An Improved Strapdown Inertial Navigation System Initial Alignment Algorithm for Unmanned Vehicles. Sensors 2018, 18, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Tian, Y.; Diao, M. Cooperative Localization Algorithm based on Hybrid Topology Architecture for Multiple Mobile Robot System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Cabuz, C.; Minami, K.; Esashi, M. Silicon resonant angular rate sensor using electromagnetic excitation and capacitive detection. J. Micromech. Microeng. 1995, 5, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderkvist, J. Micromachined gyroscopes. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 1994, 43, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A. Modern Inertial Technology: Navigation, Guidance, and Control; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lefevre, H.C. The Fiber-Optic Gyroscope; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Diao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Cooperative Localization Algorithm for Multiple Mobile Robot System in Indoor Environment Based on Variance Component Estimation. Symmetry 2017, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavson, T.; Bouyer, P.; Kasevich, M. Precision rotation measurements with an atom interferometer gyroscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasevich, M.; Chu, S. Atomic interferometry using stimulated Raman transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 67, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerginov, V.; Nemitz, N.; Weyers, S.; Schröder, R.; Griebsch, D.; Wynands, R. Uncertainty evaluation of the caesium fountain clock PTB-CSF2. Metrologia 2009, 47, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, F.; Calonico, D.; Calosso, C.E.; Godone, A.; Micalizio, S.; Costanzo, G.A. Accuracy evaluation of ITCsF2: A nitrogen cooled caesium fountain. Metrologia 2014, 51, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavner, T.P.; Donley, E.A.; Levi, F.; Costanzo, G.; Parker, T.E.; Shirley, J.H.; Ashby, N.; Barlow, S.; Jefferts, S. First accuracy evaluation of NIST-F2. Metrologia 2014, 51, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Chen, W.; Liu, K.; Liu, N.; Suo, R.; Li, T. Design of the new NIM6 fountain with collecting atoms from a 3D MOT loading optical molasses. In Proceedings of the 2015 Joint Conference of the IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium & the European Frequency and Time Forum (FCS), Denver, CO, USA, 12–16 April 2015; pp. 492–494. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, F.; Li, M.; Lin, P.; Chen, W.; Liu, N.; Lin, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, K.; Suo, R.; Li, T. NIM5 Cs fountain clock and its evaluation. Metrologia 2015, 52, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasevich, M.; Chu, S. Measurement of the gravitational acceleration of an atom with a light-pulse atom interferometer. Appl. Phys. B 1992, 54, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malossi, N.; Bodart, Q.; Merlet, S.; Lévèque, T.; Landragin, A.; Dos Santos, F.P. Double diffraction in an atomic gravimeter. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 013617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlet, S. Détermination aBsolue De G Dans Le Cadre De L’expérience De La Balance Du Watt. Ph.D. Thesis, Observatoire de Paris, Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Merlet, S.; Bodart, Q.; Malossi, N.; Landragin, A.; Dos Santos, F.P.; Gitlein, O.; Timmen, L. Comparison between two mobile absolute gravimeters: Optical versus atomic interferometers. Metrologia 2010, 47, L9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Senger, A.; Hauth, M.; Freier, C.; Schkolnik, V.; Peters, A. A mobile high-precision absolute gravimeter based on atom interferometry. Gyroscopy Navig. 2011, 2, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixler, J.B.; Foster, G.; McGuirk, J.; Kasevich, M. Atom interferometer measurement of the Newtonian constant of gravity. Science 2007, 315, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadoret, M.; De Mirandes, E.; Cladé, P.; Guellati-Khélifa, S.; Schwob, C.; Nez, F.; Julien, L.; Biraben, F. Combination of Bloch oscillations with a Ramsey-Bordé interferometer: New determination of the fine structure constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 230801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, H.; Peters, A.; Chu, S. A precision measurement of the gravitational redshift by the interference of matter waves. Nature 2010, 463, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, G.; Sorrentino, F.; Cacciapuoti, L.; Prevedelli, M.; Tino, G. Precision measurement of the Newtonian gravitational constant using cold atoms. Nature 2014, 510, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, W. Precision measurement with atom interferometry. Chin. Phys. B 2015, 24, 053702. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavson, T.; Landragin, A.; Kasevich, M. Rotation sensing with a dual atom-interferometer Sagnac gyroscope. Class. Quantum Gravity 2000, 17, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockton, J.; Takase, K.; Kasevich, M. Absolute geodetic rotation measurement using atom interferometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 133001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riou, I.; Mielec, N.; Lefèvre, G.; Prevedelli, M.; Landragin, A.; Bouyer, P.; Bertoldi, A.; Geiger, R.; Canuel, B. A marginally stable optical resonator for enhanced atom interferometry. J. Phys. B Atomic Mol. Opt. Phys. 2017, 50, 155002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.W.; Lu, S.B.; Li, R.B.; Luo, J.; Wang, J.; Zhan, M.S. Calibration of atomic trajectories in a large-area dual-atom-interferometer gyroscope. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 013620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelier, B.; Barrett, B.; Fouché, L.; Chichet, L.; Antoni-Micollier, L.; Porte, H.; Napolitano, F.; Lautier, J.; Landragin, A.; Bouyer, P. Development of compact cold-atom sensors for inertial navigation. Quantum Opt. Int. Soc. Opt. Photonics 2016, 9900, 990004. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkati, M.; Schön, S.; Schlippert, D.; Schubert, C.; Rasel, E. Could cold atom interferometry sensors be the future inertial sensors?—First simulation results. In Proceedings of the Inertial Sensors and Systems (ISS), Karlsruhe, Germany, 19–20 September 2017; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Niu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Shi, C. An in situ hand calibration method using a pseudo-observation scheme for low-end inertial measurement units. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2012, 23, 105104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacambre, J.B.; Narozny, M.; Louge, J.M. Limitations of the unscented Kalman filter for the attitude determination on an inertial navigation system. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Digital Signal Processing and Signal Processing Education Meeting (DSP/SPE), Napa, CA, USA, 11–14 August 2013; pp. 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Lawall, J.; Bardou, F.; Bouchaud, J.P.; Saubamea, B.; Bigelow, N.; Leduc, M.; Aspect, A.; Cohen-Tannoudji, C. Recent Advances in Subrecoil Laser Cooling. AIP Conf. Proc. 1994, 323, 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Allred, J.; Lyman, R.; Kornack, T.; Romalis, M. High-sensitivity atomic magnetometer unaffected by spin-exchange relaxation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89, 130801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, K.C.; Block, S.M. Optical trapping. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2004, 75, 2787–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashkin, A. Optical trapping and manipulation of neutral particles using lasers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 4853–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillot, J.; Gauguet, A.; Büchner, M.; Vigué, J. Optical pumping of a lithium atomic beam for atom interferometry. Eur. Phys. J. D 2013, 67, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyer, P. The centenary of Sagnac effect and its applications: From electromagnetic to matter waves. Gyroscopy Navig. 2014, 5, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, E.; Palmer, R.; Valenzuela, T.; Boyer, V.; Freise, A.; Bongs, K. Fluorescence detection at the atom shot noise limit for atom interferometry. New J. Phys. 2014, 16, 093046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goshen-Meskin, D.; Bar-Itzhack, I. Observability analysis of piece-wise constant systems. I. Theory. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1992, 28, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvesen, N.; Tuck, E.; Faltinsen, O. Ship motions and sea loads. Trans. SNAME 1970, 78, 250–287. [Google Scholar]

- Faltinsen, O. Sea Loads on Ships and Offshore Structures; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).