Abstract

The concept of a metric dimension was proposed to model robot navigation where the places of navigating agents can change among nodes. The metric dimension of a graph G is the smallest number k for which G contains a vertex set W, such that and every pair of vertices of G possess different distances to at least one vertex in W. In this paper, we demonstrate that for . This indicates that in these types of hex derived sensor networks, the least number of nodes needed for locating any other node is four.

1. Introduction

A task in robot navigation is to obtain the position immediately, whenever we want to know it. Suppose that a robot navigating in a sensor network is able to automatically obtain the distances to a collection of landmarks, then we can find a subset of nodes in the network such that the robot’s position in the network is uniquely identified. In order to achieve this, the concept of “landmarks in a graph” was developed [1], and later was extended to the “metric dimension”, in which one considers networks in the graph-structure framework.

Let be a k-dimensional Euclidean space and be the integer set. Assume . Every graph we consider is simple and connected and contains neither multiple edges nor loops. For two vertices of a graph , we denote by (or simply by ) the distance between and , i.e., the number of edges in the shortest path from to . For a positive integer , we call u a t-neighbor of v if . We call the set the t-neighbourhood of v, and let and . In particular, is called the open neighborhood of v and simply denoted by , and is the closed neighborhood of v. The degree of a vertex v is the cardinality of and denoted by .

Given a positive integer k and an ordered set , for a vertex , we regard the k-vector as the metric representation of v with respect to S. If any two distinct vertices of G do not have the identical representation with respect to S, then we call S a resolving set (RS) of G. The metric basis of G is the RS of G with the smallest cardinality. A metric basis of cardinality k is also called a k-metric basis. The metric dimension of G, denoted by , is defined as the cardinality of a metric basis.

For convenience, we summarize the symbols we use in Table 1.

Table 1.

The symbols used in this paper.

Due to their important applications and theoretical studies, various versions of metric generators have been proposed, which contribute deep insights into the mathematical properties of the metric dimension involving distances in graphs. Many authors have introduced different variations of metric generators—such as independent resolving sets [2], local metric sets [3], resolving dominating sets [4], strong resolving sets [5], k-metric generators [6], and a mixed metric dimension [7]—and their properties have been studied.

The subject of determining of a graph G was initially studied by Harary, et al. [8], and Slater [9] independently proved that determining of a graph G is an NP-complete problem [10]. The metric dimension has been extensively studied not merely for the computational intractability, but also for its applications in many fields, such as robot navigation [1], telecommunication, chemistry [2,11], and combinatorial optimization [4,12,13,14,15,16,17], among many others.

Honeycomb networks are a variant of meshes and tori that play an essential role in the areas of image processing, cellular phone base stations, computer graphics, and mathematical chemistry [18,19,20], because they have more attractive structural properties with respect to their diameter, degree, the total number of edges, the bisection width, and cost. Stojmenovic [20] and Parhami [21] analyzed the topological descriptors of honeycomb networks and presented an united formulation for the honeycomb. In Reference [18], based on honeycomb and hexagonal meshes, Manuel et al. introduced two new hexagonal networks, which have more interesting properties and features over certain honeycomb networks and meshes. Manuel et al. [18] posed an interesting open question to determine whether the metric dimensions of these kinds of hex-derived networks (HDNs) are between three and five. Xu and Fan [22] gave a proof and showed that the metric dimensions of the hex-derived networks and are either three or four. However until now, the exact metric dimension of these networks is still unknown. In this paper, we solve this problem for networks by showing that for .

The main contributions of this paper are listed as follows:

- We propose a vector coloring scheme to study properties of some networks with metric dimension three. By applying this approach we succeed to process hex-derived networks. Therefore, the proposed approach is a promising approach to determine if a network has metric dimension three.

- The hexagonal networks are popular mesh-derived parallel architectures, which are also a kind of sensor network and widely used in computer graphics and cellular phone base stations. Inspired by the important applications of hex-derived network, Manuel et al. started to study the metric dimension of hex-derived networks. They proposed an open problem to determine whether the metric dimension of a kind of hex-derived networks lies between three and five. Xu and Fan showed that it is less than five. In this paper, we apply our approach to completely solve this problem.

2. HDN1 Networks

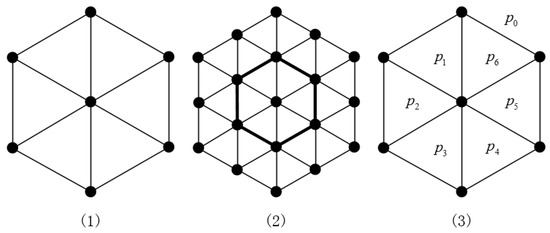

In this section, we describe the definition of networks. We follow the presentation in Reference [22]. The concept of a hexagonal mesh was introduced by Chen et al. [19]. Recall that a planar graph is a graph that can be drawn such that no edges cross each other. An n-dimensional hexagonal mesh for , denoted by HX(n), is a planar graph which consists of a collection of triangles as shown in Figure 1. The 2D hexagonal mesh HX(2) is made up of 6 triangles (see Figure 1(1)). The 3D hexagonal mesh HX(3) is constructed from HX(2) by including additional triangles around the boundary of HX(2) (see Figure 1(2)). Similarly, HX(n) is established by including additional triangles around the boundary of HX(1).

Figure 1.

Schematics of n-dimensional hexagonal meshes, HX(n): (1) HX(2), (2) HX(3), and (3) all of the faces in HX(2).

In a planar graph, there are many faces of G. If two faces p and q share at least one edge, they are said to be adjacent, or p is a neighbor of q. If a planar graph contains exactly one unbounded face, it is called the outer face of the graph. For example Figure 1(3) shows that has seven faces , for which is adjacent to and ; and is an outer face. These definitions can be found in Reference [22].

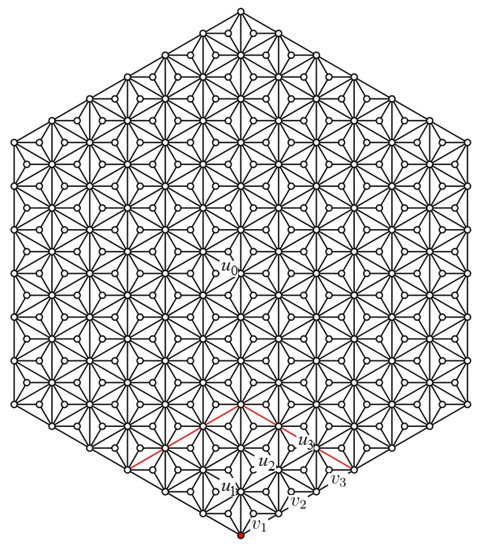

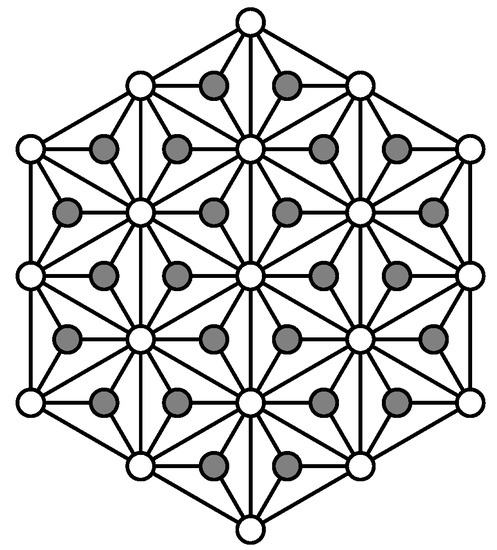

Given a graph HX(n), we use to denote the set of non-outer faces of HX. Now, for each , we add a new vertex which is located in the face p and connects with the three vertices of p. The resulting graph is . As an example, can be found in Figure 2, where the gray vertices are the additional vertices based on HX(3).

Figure 2.

Hex-derived network, .

Suppose that is a neighbor of p for each and have a one-to-one mapping to , respectively. If the vertices of p and are joined with , then we obtain . It is clear that contains as a subgraph. For , we also view and collectively as .

The central vertex of is denoted by . For an integer i, we adopt the following notations:

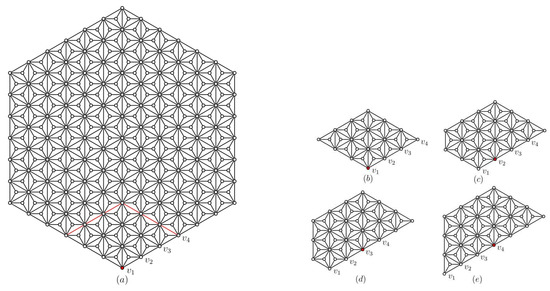

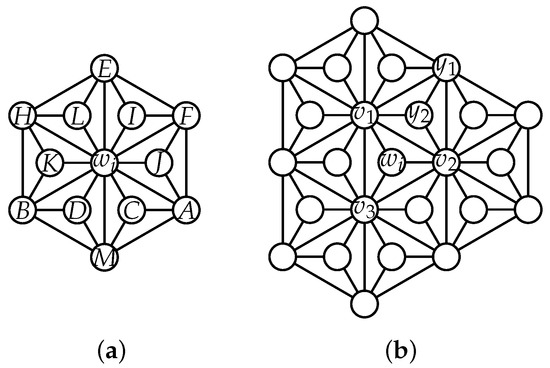

In order to understand the idea clearly, we take the network described in Figure 3a as an example, which has the nodes . Assume we use as landmarks, then a robot, which knows the distances from each element in S, can obtain its own location in this network at any time. For instance, if the distance vector from is , then it is located at the position C because the distance vectors from are pairwise distinct.

Figure 3.

(a) and (b) some vertices in .

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we provide a proof to show that for , this indicates that in this type of hex-derived sensor network, the least number of nodes needed to locate any other node is four. This solves an interesting open problem proposed in References [18,22].

Author Contributions

Methodology, P.W.; Formal Analysis, Z.S.; Investigation, E.Z.; Data Curation, Z.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Z.S.; Writing—Review and Editing, P.W., E.Z. and L.C.; Visualization, L.C.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 61602118, No. 61572010 and No. 61472074), the Fujian Normal University Innovative Research Team (No. IRTL1207), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (No. 2017J01738), and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2018A0303130115).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Khuller, S.; Ragavachari, B.; Rosenfeld, A. Landmarks in graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 1996, 70, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartrand, G.; Saenpholphat, V.; Zhang, P. The independent resolving number of a graph. Math. Bohem. 2003, 128, 379–393. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, F.; Phinezyn, B.; Zhang, P. The local metric dimension of a graph. Math. Bohem. 2010, 135, 239–255. [Google Scholar]

- Sebö, A.; Tannier, E. On metric generators of graph. Math. Oper. Res. 2004, 29, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oellermann, O.R.; Peters-Fransen, J. The strong metric dimension of graphs and digraphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 2007, 155, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Rasua, R.; Yero, I.G. k-metric antidimension: A privacy measure for social graphs. Inform. Sci. 2016, 328, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelenc, A.; Kuziak, D.; Taranenko, A.; Yero, I.G. Mixed metric dimension of graphs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2017, 314, 429–438. [Google Scholar]

- Harary, F.; Melter, R.A. On the metric dimension of a graph. Ars Comb. 1976, 2, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, P.J. Leaves of trees. Congr. Numer. 1975, 14, 549–559. [Google Scholar]

- Garey, M.R.; Johnson, D.S. Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beerliova, Z.; Eberhard, F.; Erlebach, T.; Hall, A.; Hoffmann, M.; Mihal’ak, M.; Ram, L.S. Network Discovery and Verification. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2006, 24, 2168–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Sheikholeslami, S.M.; Wu, P.; Liu, J.B. The metric dimension of some generalized Petersen graphs. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2018, 2018, 4531958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raicu, I.; Palur, S. Understanding torus network performance through simulations. In Proceedings of the Greater Chicago Area System Research Workshop; 2014. Available online: http://datasys.cs.iit.edu/reports/2014_GCASR14_paper-torus.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2018).

- Watkins, M. A theorem on Tait colorings with an application to the generalized Petersen graph. J. Comb. Theory 1969, 6, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, I.; Rahim, M.T.; Kashif, A. Families of regular graphs with constant metric dimension. Util. Math. 2007, 75, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, M.; Baig, A.Q.; Shafiq, M.K. On metric dimension of generalized Petersen graphs P(n, 3). Ars Comb. 2014, 117, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Naz, S.; Salman, M.; Ali, U.; Javaid, I.; Bokhary, S. On the constant metric dimension of generalized Petersen gpraphs P(n, 4). Acta Math. Sin. 2014, 30, 1145–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, P.; Rajan, B.; Rajasingh, I.; Monica, M.C. On minimum metric dimension of honeycomb networks. J. Discret. Algorithm 2008, 6, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.S.; Shin, K.G.; Kandlur, D.D. Addressing, routing, and broadcasting in hexagonal mesh multiprocessors. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1990, 39, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojmenovic, I. Honeycomb networks: Topological properties and communication algorithms. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 1997, 8, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhami, B.; Kwai, D.M. A unified formulation of honeycomb and diamond networks. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2001, 12, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Fan, J. On the metric dimension of HDN. J. Discret. Algorithm 2014, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).