Abstract

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV) are proving to be a promising platform design for multidisciplinary autonomous operability with a wide range of applications in marine ecology and geoscience. Here, two novel contributions towards increasing the autonomous navigation capability of a new AUV prototype (the Guanay II) as a mix between a propelled vehicle and a glider are presented. Firstly, a vectorial propulsion system has been designed to provide full vehicle maneuverability in both horizontal and vertical planes. Furthermore, two controllers have been designed, based on fuzzy controls, to provide the vehicle with autonomous navigation capabilities. Due to the decoupled system propriety, the controllers in the horizontal plane have been designed separately from the vertical plane. This class of non-linear controllers has been used to interpret linguistic laws into different zones of functionality. This method provided good performance, used as interpolation between different rules or linear controls. Both improvements have been validated through simulations and field tests, displaying good performance results. Finally, the conclusion of this work is that the Guanay II AUV has a solid controller to perform autonomous navigation and carry out vertical immersions.

1. Introduction

The ocean interior is invisible to the human eye and comprehension is poor due to the limited range of light, making deep-sea operations inaccessible to humans. With respect to the importance of the oceans on Earth, their habitat and communities contained therein are significantly under-surveyed in time and space [1]. Consequently, our perception of marine ecosystems is fragmented and incomplete. Scattered vessel-assisted sampling methodologies (i.e., ROVs, AUVs or more classic trawling) do not allow changes in communities’ composition (and hence detectable biodiversity) upon species behavior and their spatio-temporal modulation (i.e., under the form of massive and rhythmic populational displacements [2,3]). Robotic platform developments are therefore increasingly pursued to increase the autonomy of monitoring marine environments and their biological components [4,5,6,7].

While autonomy in space and terrestrial robots has seen a significant increase in technological research and derived applications, the underwater domain is still mostly operating in a teleoperated manner. In this development, Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV) are proving to be a promising design for multidisciplinary autonomous operability [8] with a wide range of applications in marine ecology and geoscience [9]. Autonomous navigation capability through depths and over and within complex seabed morphologies is a critical aspect for successful missions, but the absence of an underwater global positioning system (GPS) has forced the development of acoustic modem communicability [10,11].

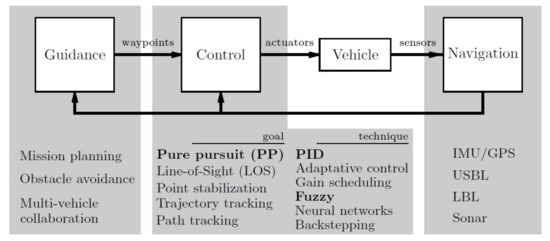

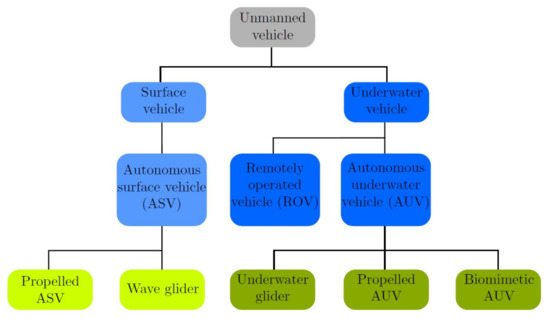

Over the last few years, different autonomous vehicles have been developed to cover all the necessities and requirements for underwater research [12], which can be grouped into different types of classifications. For example, one can try to classify vehicles that have the same type of power supply as in [13]. However, an interesting method for AUV classification is through the propulsion method, which influences the design of the model and navigation controls most; see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Underwater vehicles’ classification.

A particular case of AUV is the AUV glider [14] (p. 407), which uses small changes in its buoyancy in conjunction with wings to convert vertical motion to horizontal motion. While this method is unsuitable for high maneuverability scenarios, it significantly increases the range and duration of its operations, which can be extended from hours to weeks or months, due to its low power consumption.

Other studies have focused on biomimetic AUVs, which copy propulsion systems directly from the animal world [15]. However, the most common and extended propulsion system is through propellers. These vehicles use thrusters that realize their movement due to possessing high maneuverability capabilities and velocity. Therefore, they are usually used for inspection, underwater mapping or intervention [16].

In general, two methods can be found related to vectorial propulsion navigation systems. The first one uses fixed thrusters oriented over the vertical plane. This method is the most common and can be found in a various vehicles, such as [17]. The second method uses a system that can change the angle of the propulsion vector. Some studies have focused on a single thruster design, which can be oriented in different directions, where a joint development between MBARI (Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute) and Bluefin Robotics [18] has to be highlighted in this area, among others studies that have used this idea, such as [19]. On the other hand, some studies have used different orientable thrusters, increasing the AUV’s maneuverability (e.g., [20]).

This paper presents the development and improvement of an AUV, the Guanay II, which is a mix between a glider and a propelled vehicle, especially in the area of its navigation control. Most of the state of the art works [21,22,23] design the controllers referencing the hydrodynamic model of the vehicle when it travels at a specific forward velocity in order to simplify the control design. While this is true for a vehicle that habitually navigates in open sea, variations in velocity can be significant in areas near the coast, on the sea floor or in the interior of ports and canals.

Some of the works that propose a solution to this problem use techniques based on Lyapunov functions [24,25]. These solutions lead to a loss of simplicity of the control laws. Moreover, these non-linear techniques do not enjoy the same diffusion and popularity as their linear counterparts.

An alternative is the work of Silvestre and Pascoal [26], where they design linear controllers for different forward velocities and thereafter use a gain scheduling controller to integrate them. Other works focused on using the advantages of gain scheduling controllers, but applying a fuzzy framework to manage them (e.g., [27,28]). However, they use a linguistic interpretation to calculate the parameters of the controller, rather than an analytic procedure.

Finally, in [29], a comparison of the fuzzy controller technique in regard to gain scheduling is presented. They show that fuzzy controllers have similar performances when compared to gain scheduling ones. Thus, because fuzzy controllers perform well, in this work, the use of the type TSK in order to manage different linear controllers designed for specific conditions of forward velocity is proposed, where its analytic development has also been studied. This approach has also been used recently in others papers (e.g., [30]), where the navigation performance was simulated with 6 DOF. However, real field tests are also presented here.

This work, therefore, establishes innovations at the level of hardware and software navigation, to potentiate AUV autonomous operability, by adding novel vectorial propulsion insight to across-depth navigation and trajectory control. Vectorial propulsion systems are widely used, especially in Remotely-Operated Vehicles (ROVs). However, in AUVs, those methods are, comparatively, less implemented. From a trajectory control systems design point of view, advances in the use of methods for motion control that rely heavily on fuzzy techniques are presented.

The following sections are structured as follows: the main architecture of Guanay II is described in Section 2, where the horizontal and vertical navigation and propulsion systems are presented; Section 3 develops the inner and outer loops, describing the control of the thrusters and navigation capabilities in the horizontal plane; finally, in Section 4, the results are presented, the outcomes of both simulations and field test trials. To conclude, discussions and conclusions are presented in Section 5 and Section 6, consecutively.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Guanay II AUV Architecture

The Guanay II AUV (Figure 2) is a vehicle under permanent development constructed by SARTI Research group (www.cdsarti.org) from the Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya (UPC, www.upc.edu). This vehicle was initially designed to perform water-column measurements. With high surface stability through its fin stabilizers mounted in the hull, the Guanay II can navigate on the sea surface and perform vertical immersions to take measurements of different water parameters, such as Conductivity, Temperature and Depth (CTD). The immersion system consists of a piston-engine mechanism varying the buoyancy according to a remotely-enforced schedule (see below), which can take 1.5 L of sea water. The propulsion system consists of one main 300-W nominal power thruster (a Seaeye SI-MCT01-B) and two smaller lateral thrusters to control the direction of the vehicle (Seabotix BTD150). These devices are controlled by an on-board embedded computer and communicated with radio frequency modems to the user station.

Figure 2.

The Guanay II AUV [31] docked at the SARTI (Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya (UPC)) harbor facilities. Image taken during field tests at the Olympic Canal in Castelldefels.

Manufactured with fiberglass, the hull of Guanay II was designed to give the maximum stability in horizontal navigation. Taking into account that the main part of the vehicle’s mission is navigating on the sea surface, the Guanay II incorporates different fins to give the necessary stability to navigate through the waves. This is an important difference with respect to other AUV, which are designed to navigate mostly underwater.

On the other hand, to maximize the efficiency, the hull follows the Myring profile [32], which allows good performance in navigation through the water due to its low drag coefficient. Moreover, different blocks of foam can be added to obtain the desired flotation, and by moving the position of the ballast system, located at the bottom, the attitude can be adjusted.

2.2. Mathematical Model for Autonomous Navigation

A mathematical model for the autonomous navigation capability of Guanay II AUV has been elaborated in order to simulate the performance of the vehicle in open loop and to design controllers. However, modeling a marine vehicle, which is moving inside a turbulent fluid, is a complex task. In general, one can encounter two main difficulties: the selection of the coefficients and secondly their calculation. Different studies have been done to solve these problems [33,34,35].

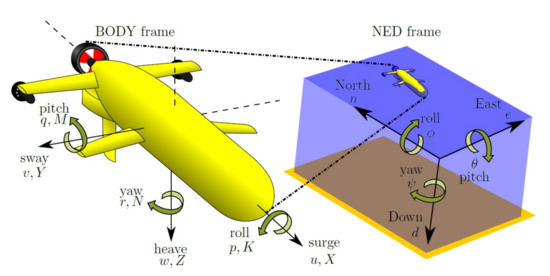

The forces and torques that generate the vehicle’s accelerations are represented in an equation, which is given as a function of the velocity vector . Figure 3 shows the vehicle coordinates, velocities and forces. Moreover, the rigid body dynamics must take into account the Coriolis and centrifugal effects. For simplicity, they are usually calculated in the body frame. Using all of these considerations, the dynamics of the vehicle can be described as follows, as is proposed in [33].

Figure 3.

Body frame and NED frame representation of linear velocities , forces , angular velocities , attitude and torque .

2.3. Horizontal Navigation and Propulsion System

In order to simplify the model, the Six Degrees Of Freedom (DOF) model can be uncoupled into a 3 DOF, where the Guanay II AUV moves only on the surface: surge, sway and yaw. The movement in the other coordinates can be disregarded. This method, known as the divide and conquer strategy, is a common strategy in these types of problems. In this situation, the velocity vector becomes , where u and v represent the body-fixed linear velocity on the x-axis (surge) and y-axis (sway), respectively, and r represents the body-fixed angular velocity on the z-axis (yaw).

Using this configuration, the control inputs consist of a force for surge movement using the three thruster, and a torque for yaw movement using the lateral thrusters as follows:

where is the distance from the lateral thrusters to the central axis and , and are the forces of the main, left and right thrusters, respectively. All these parameters, which will introduce boundaries on the vehicle’s performance, have to be considered when designing the navigation control (e.g., the maximum velocity or the breaking speed, as well as its turn radius).

2.4. Vertical Navigation and Propulsion System

Vertical immersion capability is ensured by an engine-piston set, able to collect and eject 1.5 L of water, which means that it modifies 1.5 kg of Guanay II’s density [36]. Although this system has a slow dynamic behavior, typically tens of seconds, it has a very low power consumption, where energy is used only at the beginning and end of the immersion. Moreover, because no thrusters are used, this method causes low turbulence. Therefore, it is very useful for low power consumption vehicles, such as gliders, and to perform water-column measurements, where no mixing between layers is desired.

Nevertheless, a new thruster vector control system has been designed and implemented to increase Guanay II’s performance and usability. This system can be used to navigate the vehicle during an immersion, as in [37]. The proposed system consists of adjusting the angle between the lateral thrusters and the hull through actuators. Consequently, the pitch angle of the vehicle can be controlled with this modification.

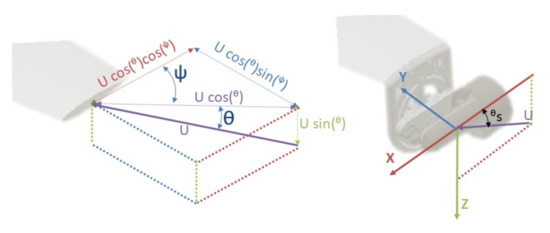

Similarly as before, the 3 DOF simplified model in the vertical plane can be derived, where the velocity vector state represents the body-fixed linear velocities on the x-axis (surge) and z-axis (heave) and the body-fixed angular velocity on the y-axis (pitch), respectively. These velocities are controlled by the input , which contains a force for surge movement using the three thrusters, and a torque for pitch movement and heave movement using the lateral thrusters. However, the force of the lateral thrusters has to be decomposed on its x-axis and z-axis due to their rotation movement (Figure 4). Using this vector movement, the control input is defined as:

where is the angle of the lateral thrusters and is the distance between the lateral thrusters and the center of buoyancy of the vehicle.

Figure 4.

Vector decomposition of the lateral propulsion vector (left) and the propulsion vector of the lateral thrusters of Guanay II AUV (right).

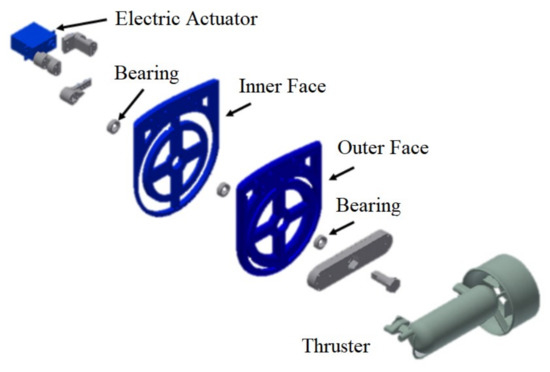

The rotation movement is provided by an electric actuator, which is coupled to the thruster through a mechanical frame (Figure 5). This new mechanism is capable of providing degrees of movement on the Guanay II AUV’s lateral thrusters.

Figure 5.

Parts of the structure designed to obtain a thruster vector control on the vertical plane.

With this new implementation, Guanay II now has full maneuverability, which allows us to control the vehicle in the horizontal and vertical plane.

4. Results

First of all, the results obtained with the vertical navigation and propulsion system explained in Section 2 are presented. Finally, the results of the automatic navigation control in the horizontal plane are presented, which is explained in Section 3. In both cases, simulations and field tests have been carried out.

4.1. Vertical Navigation Results

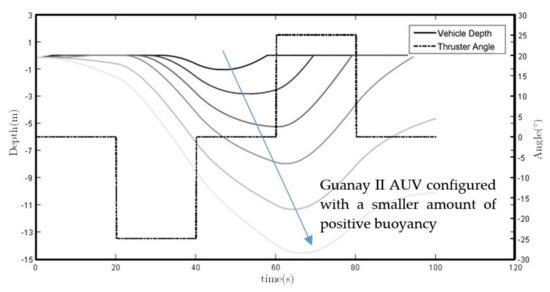

With the new thruster vector control system designed, Guanay II has now full maneuverability, which allows us to control the vehicle in the horizontal and vertical plane. Its performance was simulated using the vehicle’s mathematical model explained above (see Equations (1) and (3)), whose values for the vertical plane obtained the results presented in Figure 22. In this simulation, the strong influence that the initial buoyancy has on the system is shown, whereas with high positive buoyancy, the thrusters cannot submerge the vehicle; the vehicle cannot be brought back to the surface without a positive buoyancy.

Figure 22.

The vehicle’s vertical plane trajectory simulation with different buoyancy configurations, using the lateral thrusters at and degrees of inclination. This simulation shows that if the vehicle has a low buoyancy, the thrusters may not have enough force to bring the vehicle back to the surface. Therefore, careful buoyancy adjustment is mandatory before each mission.

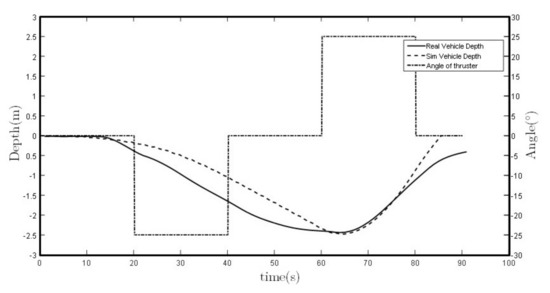

Finally, field tests have been conducted to compare and validate the simulations. Different immersions with different types of buoyancy levels, thruster force and thruster angles have been used to observe its performance, validating this method to control the depth of the Guanay II vehicle during an immersion trajectory. Figure 23 shows a comparison between a simulation and a real vehicle performance as an example.

Figure 23.

Vehicle’s vertical plane trajectory performance comparison between simulation and field test.

Some small deviations between the simulation and the field test are observed. These can be caused by a difference between the adjustment of the model coefficients and the final configuration of the AUV, such as its buoyancy position or the real inclination of the lateral thrusters during the test.

4.2. Horizontal Navigation Results

Here, the final results of both inner and outer loop controllers are presented.

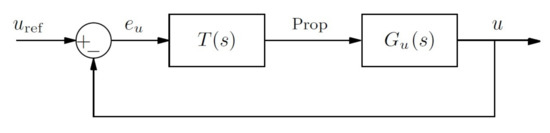

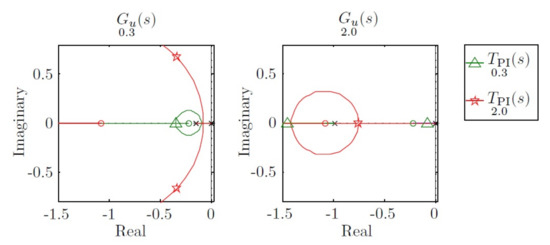

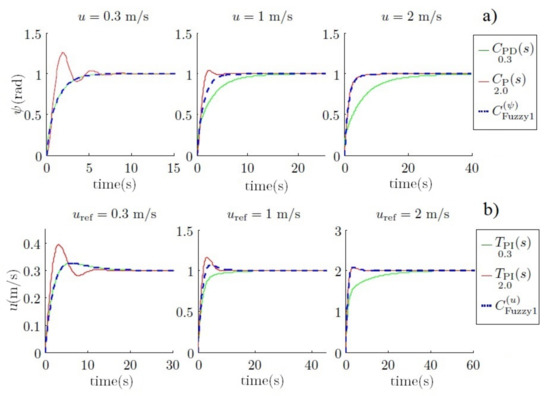

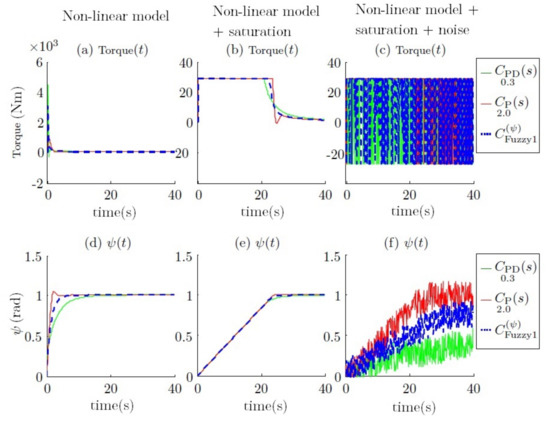

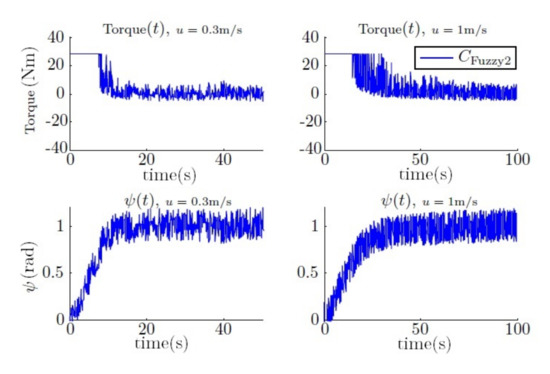

4.2.1. Inner Loop Simulations Using the Fuzzy Controller

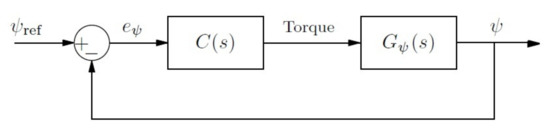

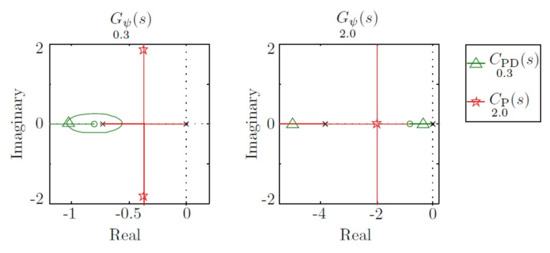

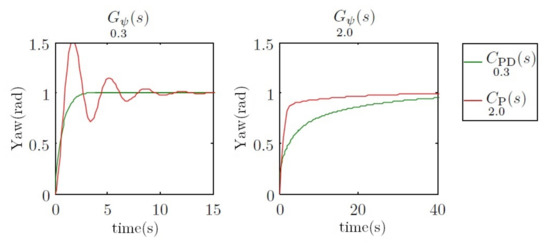

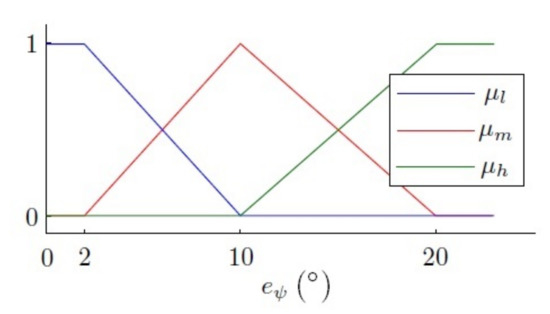

After different simulations, it is concluded that a large gain helps to achieve a specific angle faster, but in contrast, a low gain helps to reduce the switching torque on the thrusters. Therefore, the fuzzy controller is presented as an interpolation between them regarding the yaw error. The simulation result can be observed in Figure 24, where its performance can be observed, and compared with the results presented in the previous section (see Figure 15).

Figure 24.

Step response of the yaw and torque using the fuzzy controller.

Finally, Table 2 resumes the performance of compared to the other proportional controllers.

Table 2.

Comparison of the settling time and noise in the torque using the fuzzy controller and proportional controllers.

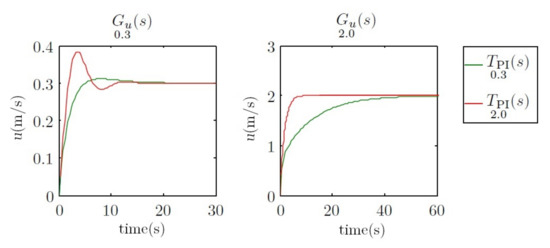

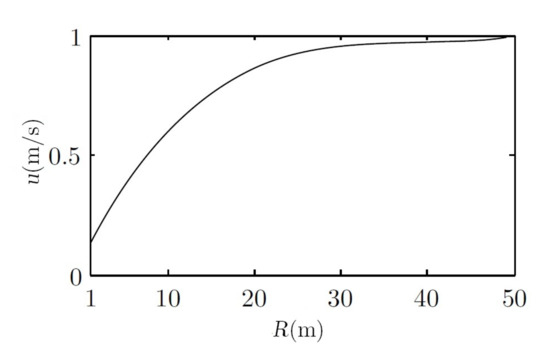

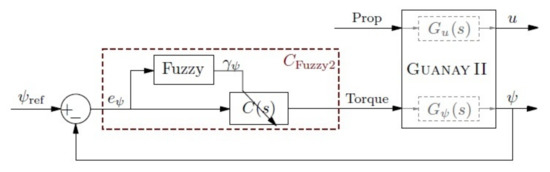

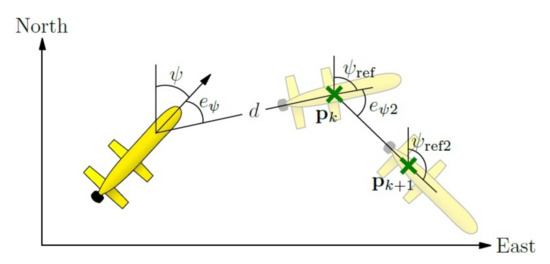

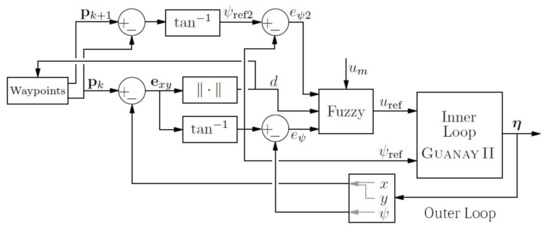

4.2.2. Outer Loop Simulations Using Fuzzy Controllers

For these simulations, three mission velocities have been chosen, 0.3 m/s, 0.6 m/s and 1 m/s. For the inner loop, and have been used to control the velocity and yaw, respectively.

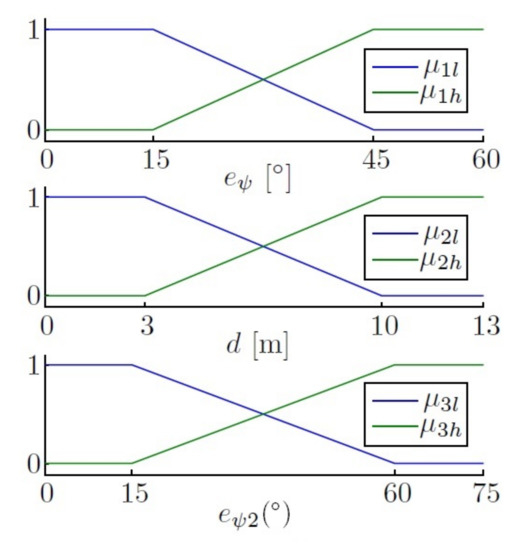

Figure 25 shows the response of the vehicle and the way in which the fuzzy controller reduces the velocity of the vehicle when it is near a waypoint, maintaining a good performance for all the velocities. This performance can be shown especially at higher velocities.

Figure 25.

(a) Responses using the pure pursuit regarding the radius of curvature. (b) Responses using pure pursuit with the fuzzy controller.

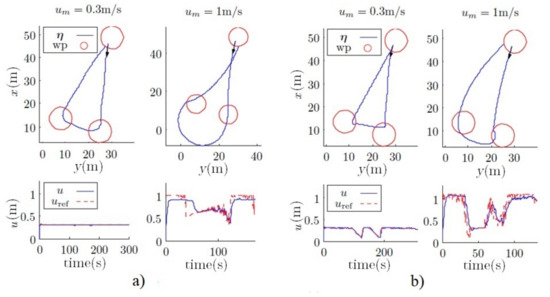

4.2.3. Field Tests

To validate the results obtained through simulations, different field tests have been carried out on both open sea around the OBSEA underwater cabled observatory area (www.obsea.es) [43], as well as in calm waters. The results presented here were taken in the Olympic Canal of Catalonia, which is both very calm and large. For these simulations, the controls have been used in the inner loop to control the velocity and the pure pursuit with a fuzzy control as the outer loop.

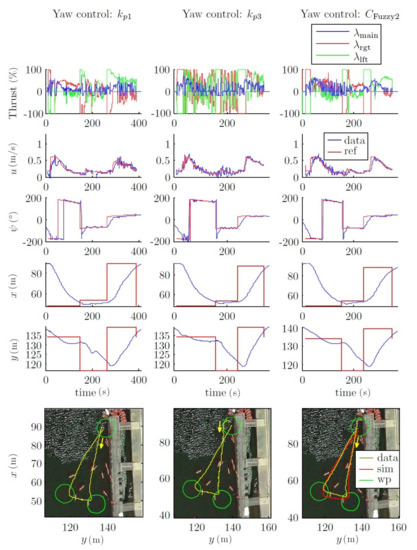

For example, Figure 26 shows a field test with a mission velocity equal to 0.6 m/s, using three types of controller to control the yaw: two proportional controllers, and ; and the fuzzy control . For both and , the thrusters were not saturated by the control action. Moreover, achieves the yaw reference more quickly than the other controllers.

Figure 26.

Field tests. Outer loop fuzzy control. Comparison of with proportional controllers. Path 1. u = 0.6 m/s. Where data is the real data acquired during the test, sim is the simulation results, and wp are the way-points to reach.

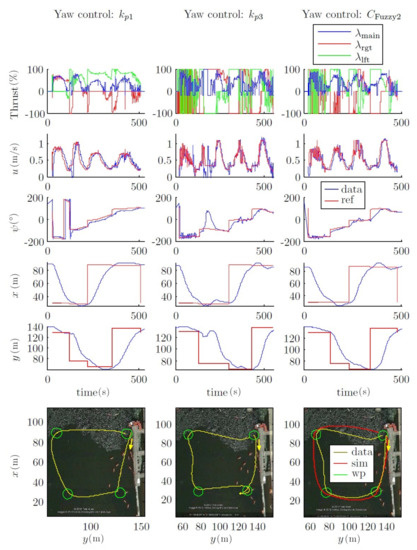

This dynamic could also be observed in Figure 27, where the path of the field test was designed with more distance between waypoints and with a mission velocity equal to 1 m/s. This can be observed on and the yaw chart.

Figure 27.

Field tests. Outer loop fuzzy control. Comparison of with proportional controllers. Path 2. u = 1 m/s.

5. Discussion

Increasingly, robotic solutions replace routine jobs on land, in space and in the sea, in industry [44]. In particular, due to the high operational costs and the limited human accessibility to the marine environment, the potential of autonomous robotic actions is even higher than on land. The aim of this paper was to study and develop a new robotized vehicle as a platform in support of applications in marine, geosciences, ecology and archeology, which have been increasingly relying on mechatronic solutions for at-sea operations in the past 30 years [5]. Here, innovations at the level of hardware and software have been established, to potentiate AUV autonomous operability, by adding novel mechatronic insight to across-depth navigation and trajectory control. The study, implementation and then testing of a specific AUV configuration in a real environment have been carried out, which include, but are not limited to, the installation of thrusters. At the same time, the control issues of these kinds of vehicles have been addressed, where comparisons between different navigation systems were carried out through both simulations and field tests. From a control systems design point of view, this work advanced the use of methods for motion control that rely heavily on fuzzy techniques. Taken together, those advancements would contribute to expanding the use of versatile AUV platforms within the framework of fast growing permanent marine ecological monitoring networks, combining fixed and mobile robotic platform designs, which are being deployed to monitor ecologically- or industrial-extractive relevant continental margin and abyssal areas [45]. In this context, our solutions propose a step forward toward AUV autonomy that will eventually lead to an in situ docking at pelagic or benthic fixed nodes.

Vectorial propulsion systems are widely used, especially in Remotely-Operated Vehicles (ROVs). However, in AUVs, those methods are comparatively less implemented. In our study, a clear example for that situation has been described, since our vehicle was potentiated with thruster solutions, which were not commercially available at the standard level. Whereas vectorial propulsion systems are not new (see some other solutions as examples in [46,47]), each vehicle has its own design and characteristic constraints, which have to be carefully taken into consideration prior to customization planning. Therefore, low-cost, off-the-shelf components that had to be adapted to our design have been bought; i.e., to obtain a thruster vector control on the vertical plane, which allows us to adjust the angle between the lateral thrusters and the hull through actuators installed on the rear fins.

From the point of view of the control systems design, the paper presents novel advancements about methods for motion that chiefly rely on fuzzy control techniques through simulations, but also field tests, as a main difference with respect to previously published papers, e.g., [30]. This work clearly showed how the developed algorithms were efficient in enhancing the motion control capabilities. Whereas the navigation control strategy used an already known approach (i.e., the pure-pursuit; see as an example [48]), the implemented methodology through diffuse techniques is entirely new and specifically described in our script.

Most of the works about control systems implement the controllers using the vehicle hydrodynamic model at specific forward velocity to simplify the design [21,22,23]. Whereas this is correct for vehicles that usually navigate in open seas, where velocity is mainly constant, this method should not be used in other scenarios, such as in the interior of harbors and canals. In these situations, the variation of the forward velocity becomes relevant, and it is then important to be able to vary the controller’s working point to adjust the paths to the desired ones. Some authors have designed a two-step control approach [49], which switches between two controls designed for ‘high’ and ‘low’ velocities. However, the decision to change between one controller to the other one is not trivial. To solve this problem, Silvestre and Pascoal [26] use a set of linear controllers adjusted for different forward velocities and then use a gain scheduling controller to integrate them. Here, the same methodology has been followed, but innovatively applying a fuzzy controller, to integrate the different linear controllers. The fuzzy controller allows activation zones to be established, which can be controlled through fuzzy sets. This method showed good navigation performance and was used as interpolation between different rules or linear controls. This approach has also been used recently in other papers (e.g., [30]), where the navigation performance was simulated with 6 DOF.

Here, two controllers have been designed to provide autonomous navigation capabilities: one for the inner loop (dynamic), which is in charge of controlling the thrusters to reach a reference yaw and forward velocity; the other for the outer loop (kinematic), which is in charge of generating the yaw and forward velocity references, according to the waypoints and the vehicle’s current state. With respect to the inner loop, two solutions have been presented for velocity and yaw control based on Type-1 TSK fuzzy controller. These controllers were used to manage, at a higher level, different linear controllers designed for specific scenarios, such as different forward velocities. The inner loop developed to control the vehicle’s velocity and yaw results from a vehicle’s linear model in sections obtained from its non-linear model, where the vehicle’s structural characteristics have to be taken into account. When linear controllers (i.e., PID) are used, diffuse techniques were implemented to provide the adaptive navigation capability. On the other hand, the detailed study, development and identification of a dynamic model were required to take into account the hydrodynamic effects and propeller characteristics, which have also been presented.

With respect to the outer loop, we have presented a solution for pure pursuit navigation, where the radius of curvature of the vehicle is taken into account while trying at the same time to preserve the forward velocity, using also a Type-1 TSK fuzzy controller. The main advantage of this class of non-linear controllers, in front of others such as gain-scheduled ones [26,50], is that it is based on the zonal capacity of the linguistics law. This allows us to adjust the theoretical laws into specific zones and interpret those laws as a function of their different zones. This performance is in contrast to the classic or digital logic one , which operates with discrete values. Moreover, this kind of zonal controller will allow us to include future laws on the vertical plane as an extra zone of functionality.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a new thruster vector control system, which allows depth navigation control. This system was implemented on Guanay II AUV and has been evaluated and tested through different simulations and field tests, which demonstrate the performance of this system and its capability to be used as a vectorial navigation system.

Moreover, a complete study on automatic navigation control has been presented, where two fuzzy controllers have been developed to solve non-linear properties in both inner and outer loop controls; for example, the presence of noise on the yaw measurements introducing fast switching into the thrusters’s control and a fuzzy control based on distance and angle error to the next waypoints to control the vehicle’s velocity, which yields greater accuracy on the trajectory of the vehicle.

All these considerations are shown in the field tests, where two comparative mission velocity (i.e., 0.6 m/s and 1 m/s; see Figure 26 and Figure 27) types of trajectories are represented. In both cases, the forced turn performances (to go to the next waypoint) were greatly increased. This occurred because the forward velocity was reduced when the vehicle reached a waypoint. With respect to the power used by the thrusters, it can be observed that both the and controls did not saturate the thrusters.

Moreover, the simulated trajectory using was very similar to the experimental one. However, the trajectories south-north and west-east had a small deviation during the and the tests (see Figure 27), probably due to a compass misalignment or to the increase of the sea currents in the test canal because of changes in the weather conditions.

On the other hand, the depth navigation performance is shown in Figure 22 and Figure 23, where the influence of the vehicle buoyancy is observed, which should be taken carefully into consideration before each mission.

Finally, a controller method for the vertical plane, and its modeling in conjunction with the horizontal plane, to allow more complex trajectories in 3D, should be addressed as future work, as well as the implementation of other controller techniques, such as path following, which would allow the vehicle to follow a specific path instead of simple waypoints.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the project JERICO-NEXTfrom the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 research and Innovation program under Grant Agreement No. 654410. We would also like to thank the Spanish Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad under contract for the Spanish thematic network MarInTech(Ref. CTM 2015-68804-REDT (Instrumentation and Applied Technology for the Study, Characterization and Sustainable Exploration of Marine Environment, MarInTech)) for their financial support. This work has been directed and carried out by members of the Tecnoterra-associated unit of the Scientific Research Council through the Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya, the Jaume Almera Earth Sciences Institute and the Marine Science Institute.

Author Contributions

Ivan Masmitja, Julian Gonzalez, and Cesar Galarza designed and performed the experiments, analysed the data, and contributed writing the paper. Spartacus Gomariz, Jacopo Aguzzi, and Joaquin del Rio conceived the experiments and contributed with the materials and analysis tools.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ramirez-Llodra, E.; Brandt, A.; Danovaro, R.; De Mol, B.; Escobar, E.; German, C.R.; Levin, L.A.; Martinez Arbizu, P.; Menot, L.; Buhl-Mortensen, P.; et al. Deep, diverse and definitely different: Unique attributes of the world’s largest ecosystem. Biogeosciences 2010, 7, 2851–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguzzi, J.; Company, J.B.; Azzurro, E.; Sardà, F. Challenges to the assessment of benthic populations and biodiversity as a result of rhythmic behaviour: Video solutions from cabled observatories. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 2012, 50, 235–286. [Google Scholar]

- Aguzzi, J.; Company, J.B.; Costa, C.; Menesatti, P.; Garcia, J.A.; Bahamon, N.; Puig, P.; Sarda, F. Activity rhythms in the deep-sea: A chronobiological approach. Front. Biosci. 2011, 16, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grémillet, D.; Puech, W.; Garçon, V.; Boulinier, T.; Maho, Y. Robots in Ecology: Welcome to the machine. Open J. Ecol. 2012, 2, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.B.; Pizarro, O.; Steinberg, D.M.; Friedman, A.; Bryson, M. Reflections on a decade of autonomous underwater vehicles operations for marine survey at the Australian Centre for Field Robotics. Annu. Rev. Control 2016, 42, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doya, C.; Chatzievangelou, D.; Bahamon, N.; Purser, A.; De Leo, F.C.; Juniper, S.K.; Thomsen, L.; Aguzzi, J. Seasonal monitoring of deep-sea megabenthos in Barkley Canyon cold seep by internet operated vehicle (IOV). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Thomsen, L.; Aguzzi, J.; Costa, C.; De Leo, F.; Ogston, A.; Purser, A. The Oceanic Biological Pump: Rapid carbon transfer to depth at Continental Margins during Winter. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2045–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, J.J.; Bahr, A. Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Navigation. In Springer Handbook of Ocean Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 341–358. [Google Scholar]

- Wynn, R.B.; Huvenne, V.A.; Bas, T.P.L.; Murton, B.J.; Connelly, D.P.; Bett, B.J.; Ruhl, H.A.; Morris, K.J.; Peakall, J.; Parsons, D.R.; et al. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs): Their past, present and future contributions to the advancement of marine geoscience. Mar. Geol. 2014, 352, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, G.; Lane, D.M.; Tsiogkas, N.; Spaccini, D.; Petrioli, C.; Kruusmaa, M.; Preston, V.; Salumäe, T. MANgO: Federated world Model using an underwater Acoustic Network. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2017, Aberdeen, UK, 19–22 June 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov, A.Y.; Dubrovin, F.S.; Unru, P.P.; Kulik, S.Y. Experimental research of distance estimation accuracy using underwater acoustic modems to provide navigation of underwater objects. In Proceedings of the 2017 24th Saint Petersburg International Conference on Integrated Navigation Systems (ICINS), St. Petersburg, Russia, 29–31 May 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Manley, J.E. Unmanned Maritime Vehicles, 20 years of commercial and technical evolution. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2016 MTS/IEEE, Monterey, CA, USA, 19–23 September 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Shang, J.; Luo, Z.; Tang, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, J. Reviews of power systems and environmental energy conversion for unmanned underwater vehicles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 1958–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.; Roberts, G. Advances in Unmanned Marine Vehicles; IEE Control Series; Institution of Engineering and Technology: Stevenage, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, S.; Abdelkefi, A. Review of marine animals and bioinspired robotic vehicles: Classifications and characteristics. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 93, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridao, P.; Carreras, M.; Ribas, D.; Sanz, P.J.; Oliver, G. Intervention AUVs: The Next Challenge. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2014, 47, 12146–12159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, M.; Hernández, J.D.; Vidal, E.; Palomeras, N.; Ribas, D.; Ridao, P. Sparus II AUV-A Hovering Vehicle for Seabed Inspection. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2018, 43, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibenac, M.; Kirkwood, W.J.; McEwen, R.; Shane, F.; Henthorn, R.; Gashler, D.; Thomas, H. Modular AUV for routine deep water science operations. In Proceedings of the OCEANS ’02 MTS/IEEE, Biloxi, MI, USA, 29–31 October 2002; Volume 1, pp. 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo, E.; Michelini, R.C.; Filaretov, V.F. Conceptual Design of an AUV Equipped with a Three Degrees of Freedom Vectored Thruster. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2004, 39, 365–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Luo, Q.; Jin, C.; Liang, G. Modeling and diving control of a vector propulsion AUV. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Qingdao, China, 3–7 December 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Valenciaga, F.; Puleston, P.F.; Calvo, O.; Acosta, G.G. Trajectory Tracking of the Cormoran AUV Based on a PI-MIMO Approach. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2007—Europe, Aberdeen, UK, 18–21 June 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Maurya, P.; Desa, E.; Pascoal, A.M.S.; Barros, E.; Navelkar, G.; Madhan, R.; Mascarenhas, A.; Prabhudesai, S.; Afzulpurkar, S.; Gouveia, A.; et al. Control of the Maya Auv in the Vertical and Horizontal Planes: Theory and Practical Results. In Proceedings of the 7th IFAC Conference on Manoeuvring and Control of Marine Craft, MCMC2006, Lisbon, Portugal, 20–22 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Zhou, J.; Bian, X.; Li, J. Fuzzy sliding-mode controller for the motion of autonomous underwater vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, Takamatsu, Japan, 5–8 August 2008; pp. 466–470. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre, L.; Soetanto, D.; Pascoal, A. Nonlinear path following with applications to the control of autonomous underwater vehicles. In Proceedings of the 42nd IEEE International Conference on Decision and Control (IEEE Cat. No.03CH37475), Maui, HI, USA, 9–12 December 2003; Volume 2, pp. 1256–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Breivik, M.; Fossen, T.I. A unified concept for controlling a marine surface vessel through the entire speed envelope. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Symposium on, Mediterrean Conference on Control and Automation Intelligent Control, Limassol, Cyprus, 27–29 June 2005; pp. 1518–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre, C.; Pascoal, A. Depth control of the INFANTE AUV using gain-scheduled reduced order output feedback. Control Eng. Pract. 2007, 15, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Bian, X.; Yan, Z.; Xia, G. The application of self-tuning fuzzy PID control method to recovering AUV. In Proceedings of the 2012 Oceans, Yeosu, Korea, 21–24 May 2012; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, S.W.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, H.J. Design of T-S fuzzy-model-based diving control of autonomous underwater vehicles: Line of sight guidance approach. In Proceedings of the 2012 12th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems, JeJu Island, Korea, 17–21 October 2012; pp. 2071–2073. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, B.A.; Srinivas, Y.; VenkataRamesh, E. Analytical structures of Gain-Scheduled fuzzy PI controllers. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Industrial Electronics, Control and Robotics, Orissa, India, 27–29 December 2010; pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, M.M.; Elshenawy, A.K.; El Singaby, M. Trajectory following and stabilization control of fully actuated AUV using inverse kinematics and self-tuning fuzzy PID. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomáriz, S.; Masmitjà, I.; González, J.; Masmitjà, G.; Prat, J. GUANAY-II: an autonomous underwater vehicle for vertical/horizontal sampling. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2015, 20, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myring, D.F. A Theoretical Study of Body Drag in Subcritical Axisymmetric Flow. Aeronaut. Q. 1976, 27, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, T.I. Guidance and Control of Ocean Vehicles; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Prestero, T. Verification of a Six Degree of Freedom Simulation Model for the Remus Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. Master’s Thesis, University of California at Davis, Davis, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Agudelo, J.G. Contribution to the Model and Navigation Control of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Masmitjà, I.; González, J.; Gomáriz, S. Buoyancy model for Guanay II AUV. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2014, Taipei, Taiwan, 7–10 April 2014; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bluefin-21 Autonomous Underwater Vehicle, General Dynamics Mission Systems. 2017. Available online: http://www.bluefinrobotics.com (accessed on 16 April 2018).

- Fossen, T. Marine Control Systems: Guidance, Navigation and Control of Ships, Rigs and Underwater Vehicles; Marine Cybernetics: Trondheim, Norway, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, G.; Fossen, T.I.; Yoerger, D.R. Underwater Robotics. In Springer Handbook of Robotics; Siciliano, B., Khatib, O., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 987–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, T.; Sugeno, M. Fuzzy identification of systems and its applications to modeling and control. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1985, MC-15, 116–132. [Google Scholar]

- González, J.; Gomáriz, S.; Batlle, C.; Galarza, C. Fuzzy controller for the yaw and velocity control of the Guanay II AUV. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2015, 48, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Agudelo, J.; Masmitjà, I.; Gomáriz-Castro, S.; Batlle, C.; Sarrià-Gandul, D.; del Río-Fernández, J. Mathematical model of the Guanay II AUV. In Proceedings of the 2013 MTS/IEEE OCEANS, Bergen, Norway, 10–13 June 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Aguzzi, J.; Mànuel, A.; Condal, F.; Guillén, J.; Nogueras, M.; Del Rio, J.; Costa, C.; Menesatti, P.; Puig, P.; Sardà, F.; Toma, D.; Palanques, A. The New Seafloor Observatory (OBSEA) for Remote and Long-Term Coastal Ecosystem Monitoring. Sensors 2011, 11, 5850–5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oesterreich, T.D.; Teuteberg, F. Understanding the implications of digitisation and automation in the context of Industry 4.0: A triangulation approach and elements of a research agenda for the construction industry. Comput. Ind. 2016, 83, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danovaro, R.; Aguzzi, J.; Fanelli, E.; Billett, D.; Gjerde, K.; Jamieson, A.; Ramirez-Llodra, E.; Smith, C.R.; Snelgrove, P.V.R.; Thomsen, L.; et al. An ecosystem-based deep-ocean strategy. Science 2017, 355, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammad, M.M.; Elshenawy, A.K.; El Singaby, M.I. Position Control and Stabilization of Fully Actuated AUV using PID Controller. In Proceedings of SAI Intelligent Systems Conference (IntelliSys) 2016; Bi, Y., Kapoor, S., Bhatia, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 517–536. [Google Scholar]

- Allotta, B.; Costanzi, R.; Pugi, L.; Ridolfi, A. Identification of the main hydrodynamic parameters of Typhoon AUV from a reduced experimental dataset. Ocean Eng. 2018, 147, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneydor, N. Chapter 3—Pure Pursuit. In Missile Guidance and Pursuit; Shneydor, N., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 1998; pp. 47–76. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, P.; Silvestre, C.; Oliveira, P. A two-step control approach for docking of autonomous underwater vehicles. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2015, 25, 1528–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminer, I.; Pascoal, A.; Hallberg, E.; Silvestre, C. Trajectory Tracking for Autonomous Vehicles: An Integrated Approach to Guidance and Control. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 1998, 21, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).