Abstract

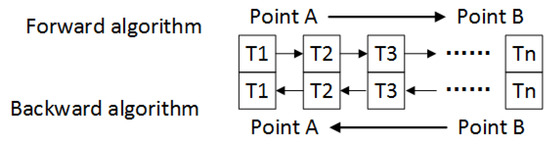

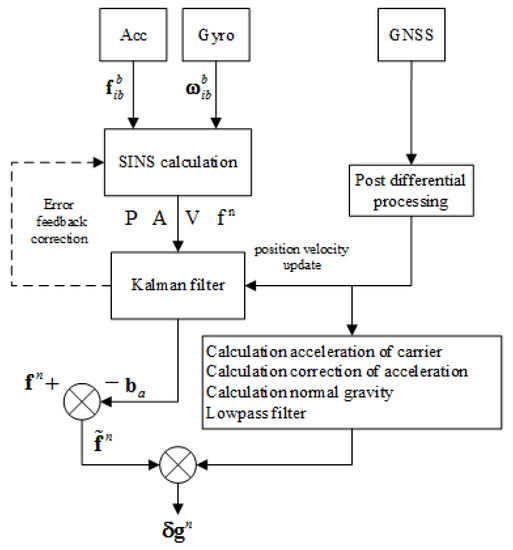

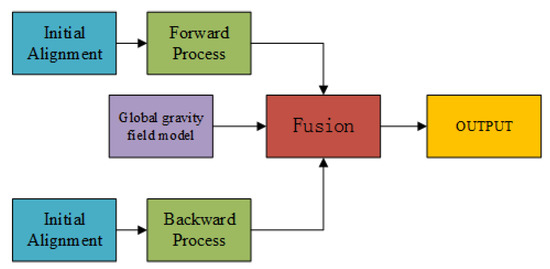

Strapdown airborne gravimetry is an efficient way to obtain gravity field data. A new method has been developed to improve the accuracy of airborne vector gravimetry. The method introduces a backward strapdown navigation algorithm into the strapdown gravimetry, which is the reverse process of forward algorithm. Compared with the forward algorithm, the backward algorithm has the same performance in the condition of no sensor error, but has different error characteristics in actual conditions. The differences of the two algorithms in the strapdown gravimetry data processing are presented by simulations, which show that the two algorithms have different performance in the horizontal attitude measurement and convergence of integrated navigation filter. On the basis of detailed analysis, the procedures of accuracy improvement method are presented. The result of this method is very promising when applying to an actual flight test carried out by a SGA-WZ02 strapdown gravimeter. After applying the proposed method, the repeatability of two gravity disturbance horizontal components were 1.83 mGal and 1.80 mGal under the resolution of 6 km, which validate the effectiveness of the method. Furthermore, the wavenumber correlation filter is also discussed as an alternative data fusion method.

1. Introduction

The information of Earth’s gravity field is important in geophysics, geodesy, resource exploration, etc. [1]. In order to accurately determine the information of the gravity field, there are several methods, such as satellite gravimetry, airborne gravimetry, shipborne gravimetry and ground gravimetry [2]. The satellite gravimetry can achieve the task of determination high precision global gravity field, but it cannot obtain the gravity information in the high frequency band. The ground gravimetry is the initial and the most classical method to survey the gravity field, the shortcoming of which is inefficiency and confined to the terrain. Shipborne gravimetry, just as its name, uses a ship to measure the gravity field information. Among all the gravity measurement methods, airborne gravimetry is an effective method to collect high precision and high resolution large areas gravity field datum [3].

There are different types of airborne gravimeters to achieve the task of airborne gravimetry and noted that the different principles are used in different airborne gravimetry systems. This means that the stable platform technology is used in GT series gravimeters, AIRGrav gravimeter and Cheken–AM gravity system [4,5], while a Strapdown Inertial Navigation System (SINS) is used in SISG and SGA-WZ [6,7]. Furthermore, the airborne gravimeter can be divided into scalar gravimeter and vector gravimeter according to the target of measurement. The GT gravimeter and Cheken–AM gravity system are scalar gravimeters, while the AIRGrav gravimeter, SISG and SGA-WZ can obtain the gravity vector information.

The platform gravimeter was firstly used in the gravimetry survey. The GT gravimeter was developed by the GT company (Moscow, Russia) and completed more than 200,000 kilometers scalar gravimetry task all over the world, with a precision of 0.6 mGal (mGal ≈ 10−5 m/s2) under the resolution of 3 km [8]. The AIRGrav gravimeter can measure the three components of gravity field aided by Canadian Gravimetric Geoid 2005 (CGG05) [9]. The repeatability of vertical components can reach the 0.2 mGal and the repeatability of horizontal was about 2 mGal [9].

With the breakthroughs of inertial technology, the research on strapdown gravimetry stemmed from the 1990s. Using a math platform instead of physical platform, the strapdown gravimeter has a lower cost, smaller size and simpler structure than the platform gravimeters. In addition, the strapdown gravimeter can directly measure the gravity disturbance vector. The first airborne gravimeter, SISG, was developed by the University of Calgary [7]. The presented results showed that accuracies of approximately 4 mGal and 6 mGal can be achieved for the vertical and horizontal gravity components by taking advantage of a new algorithm in the inertial frame and wavenumber coefficient filter (WCF) [10]. Moreover, the navigation-grade SINS could be regarded as a strapdown gravimeter and show 0.5–3.2 mGal precision in scalar gravimetry [11]. Through thermal calibration and correction, the accuracy of navigation-grade SINS was superior to 2 mGal when used as a gravimeter [12]. The SGA-WZ series gravimeter is the strapdown gravimeter developed by a National University of Defense Technology. After optimizing the stability and the environment adaptability, the vertical gravity disturbance accuracy new generation of SGA-WZ gravimeter is better than 1 mGal under the resolution of 3 km [13]. In addition, the France Aerospace Lab has developed an absolute shipborne gravimeter and the precision is superior to 1 mGal [14].

The scalar gravimetry is almost mature, the accuracy of which can satisfy the requirements of most applications at present [15]. However, the vector gravimetry still has a great potential in the accuracy promotion for researchers to strive. For example, wavelet decomposition was used to decline the error in the vector gravimetry and the accuracy was about 7 mGal [16]. In addition, the artificial neural network was also applied into vector gravimetry [17]. After algorithm optimization, the repeatability of the data collected by Calgary could directly reach 4–8 mGal in three directions, which was improved to 2–4 mGal after applying WCF [18]. To reduce the negative effect of the gravity vector itself on the measurement, the iterative method was presented in the different research and showed promising results [19]. The high precision gravity model, for example EGM2008, was introduced into vector gravimetry to correct the low frequency error [20].

WCF is a widely used method to eliminate the measurement error in gravimetry and former research has shown its excellent performance. However, the application of WCF needs at least two repeated lines and an empirical threshold, which means low efficiency and restrictions. In this study, the backward strapdown inertial navigation algorithm was introduced into vector gravimetry. The backward algorithm was widely used in the fast initial alignment of autonomous underwater vehicle navigation [21]. When compared with a forward strapdown inertial navigation algorithm, the backward algorithm has the same performance in an ideal condition and different error characteristics in actual sensor error conditions [22]. The prerequisite of repeat lines in WCF is not needed because the data could be processed separately by the forward and backward algorithm. Based on the different characteristics, the weighted equation from optimal linear smoothing could be taken into application to fuse the results from the forward algorithm and backward algorithm [23].

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the backward strapdown inertial navigation algorithm and the principle of strapdown gravimetry. Both the simulations about the different characteristics of two algorithms and the proposed accuracy improvement method are presented in Section 3. An airborne gravimetry flight test using SGA-WZ02 is used to elaborate the actual performance of the method in Section 4. Section 5 discusses possible situations in the application of the method, which include using WCF instead of the variance weighted equation, the performance under different resolutions and the absence of gravity field model information. Finally, conclusions are drawn in Section 6.

4. The Actual Improvement in an Airborne Strapdown Gravimetry Test

4.1. Test Description

The survey was carried out in the Xinjiang Province of China using SGA-WZ02 in 2015. The gravimetry system was mounted on a Cessna208 aircraft, which was a fixed-wing aircraft with an autopilot. In addition, a GT-2A gravimeter participated in the test. The properties of SGA-WZ02 were shown in Table 2 and the picture of SGA-WZ02 and cabin was shown in Figure 10 [30]. Three GNSS receivers were used for the differential kinematic positioning, one of the receivers was located on the airplane and the others were located on the roof as ground stations. All of the GNSS receivers installed on the ground and on the airplane were NOVATEL OEMV3 (Calgary, AB, Canada). Use WAYPOINT to obtain differential GNSS position result, and then the velocity and acceleration are obtained by the position difference method. Lever arm, which was used to transform the sensitive center of the GNSS receiver to the SINS sensitive center, was m in the i-frame. Moreover, the ground vector gravimetry was unavailable in this test, so we regarded the gravity disturbance information at the tarmac as mGal.

Table 2.

Properties of SGA-WZ02.

Figure 10.

Appearance of SGA-WZ02 and the picture of the flight cabin.

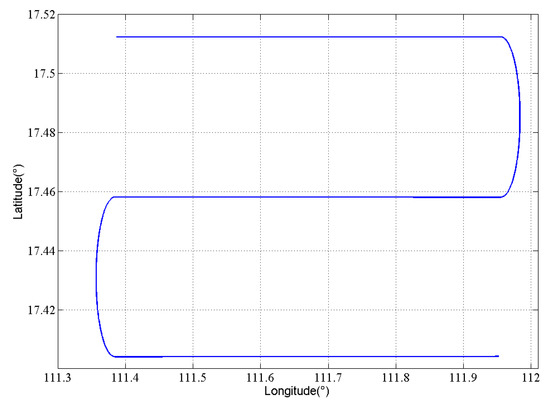

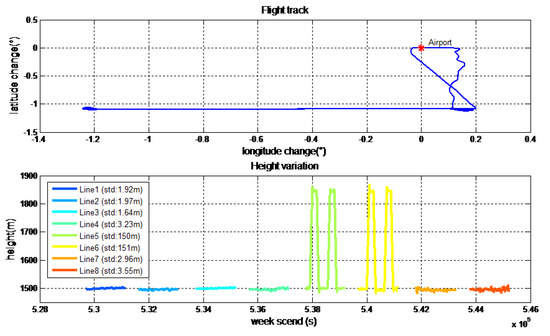

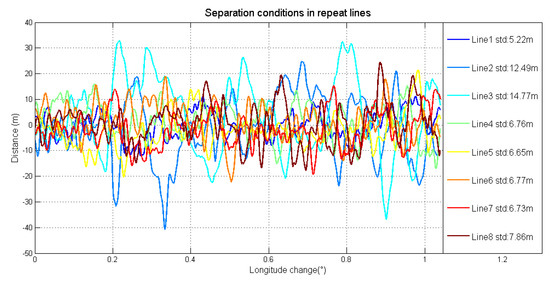

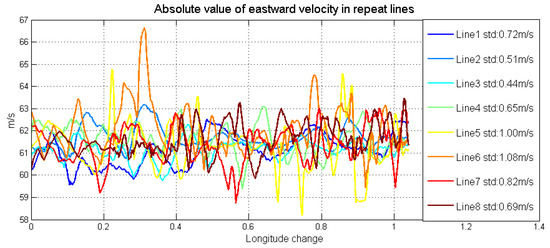

The detailed characters of flight were shown in Table 3. Each survey line was about 80 km, whose ends were extended 3 km to eliminate the boundary effect of low-pass filter. In this airborne gravimetry test, the maximum distance between survey area and airport was less than 140 km. Figure 11 is the flight trajectory and height variations in lines. There are eight lines in this flight, among which the fifth and sixth lines are the undulated flight to test the performance of SGA-WZ02 in extremely turbulent conditions. Thus, what we are more concerned about is the result of the normal lines (lines 1–4, 7, 8). The air flow condition was getting worse during the test. Figure 12 is the northward separation conditions and Figure 13 is the absolute value of eastward velocity. The trajectory of lines 2 and 3 have not been well controlled when compared with other lines, and the speed in lines 5 and 6 is not very stable due to undulating flight.

Table 3.

Characteristics of flight tests.

Figure 11.

Path of flight test and height variation in lines.

Figure 12.

Northward separation conditions in repeat lines.

Figure 13.

Absolute value of eastward velocity in repeat lines.

4.2. The Improvement Results after the Forward and Backward Algorithm Data Fusion

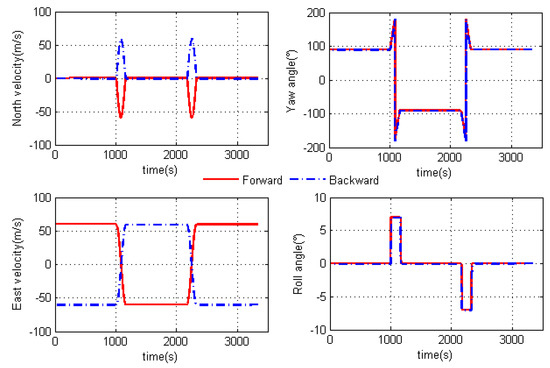

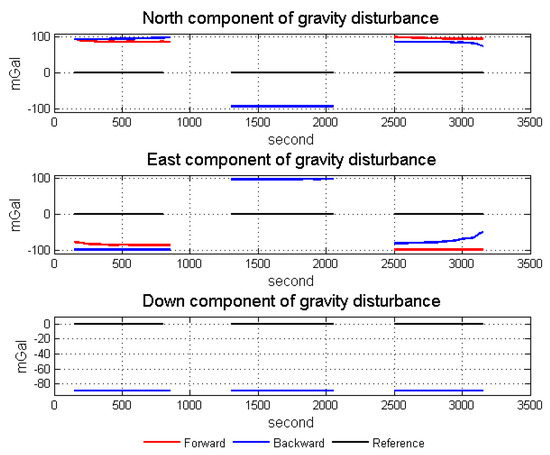

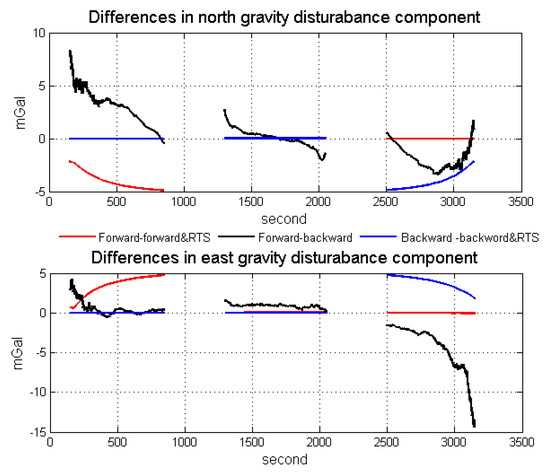

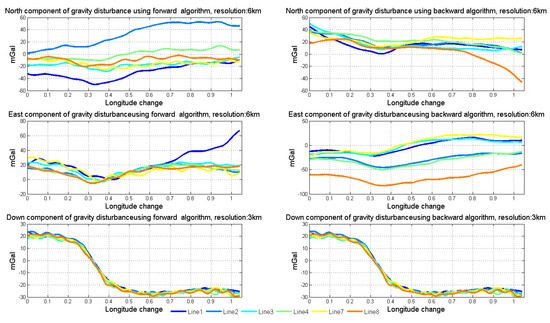

Using the method of strapdown vector gravimetry shown in the former section, we could get the result of airborne gravimetry. During data processing, we use both forward algorithm and backward algorithm to calculate the data collected by SGA-WZ02. The results of normal lines are shown in Figure 14. In order to testify the quality of gravimetry in repeat lines, the repeatability of the gravity disturbance vector can be calculated by Equations (13) and (14) [31]. Equation (13) describes the repeatability of certain lines and Equation (14) is the total repeatability of repeat lines. The repeatability results are shown in Table 4.

Figure 14.

Results of normal lines using two algorithms.

Table 4.

Repeatability results of repeat lines (mGal).

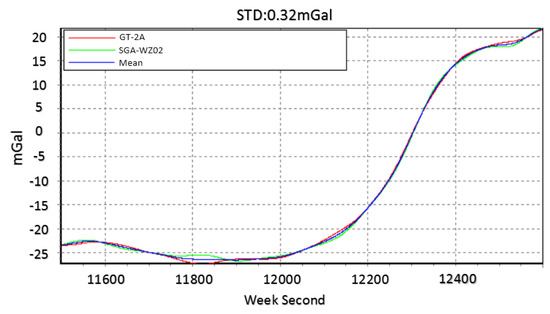

The down component is in 3 km resolution, while the north and east components are in 6 km resolution. Figure 15 shows the mean values of vertical components among normal lines in SGA-WZ02 and GT-2A gravimeters [30]. The repeatability in a down component is much better than that of north and east components because the attitude error mainly impacts the horizontal of gravity disturbance. Thus, we mainly talked about the horizontal components of gravity disturbance in this paper.

Figure 15.

Mean value of vertical component among normal lines in GT-2A and SGA-WZ02.

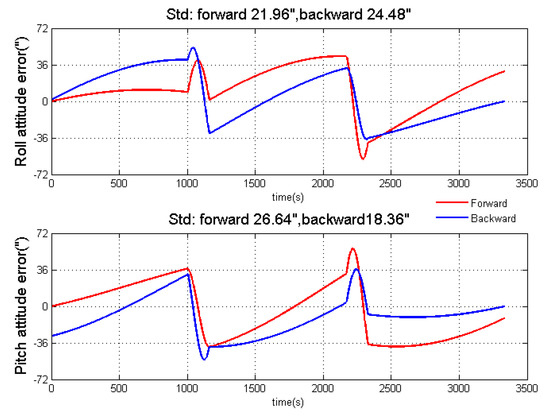

As the simulation points out that the accuracy of north component of gravity disturbance, which is mainly related to the pitch angle error, obtained from the backward algorithm is better than that obtained from the forward algorithm, while the accuracy of the east component of gravity disturbance, which is mainly related to the roll angle error, obtained from the forward algorithm is better than that obtained from the backward algorithm. Obviously, using the north component resulting from the backward algorithm and the east component resulting from the forward algorithm is the simplest way to get better measurement results. However, this way cannot meet the requirements of high accuracy applications and there is a better way to combine the two algorithms.

where is the repeatability of repeat line j, is the different value between the mean value at point i and the value in repeat line j at point i, N is the total data point number of common part of repeat lines, M is the total line number of repeat line flight, and is the repeatability of total repeat line.

Except the difference in the accuracy of two horizontal components, the advantages of two algorithms are the complementarity in the gravimetry. Before fusing the two results, we use EIGEN-6C4, the low frequency part of which only comes from satellite gravimetry to correct the error in low frequency [32]. The method of using gravity model to improve the vector gravimetry has been shown as a reference, in which the result of linear fitting is regarded as the low frequency component and the remaining part as the high frequency component [20]. Equation (15) describes the frequency separation method. Thus, the gravity disturbance can be divided into three parts: bias, linear part and high frequency part, as shown in Equation (16). The bias is obtained from the ground gravimetry and upward extension, the linear coefficient is obtained by gravity field model and the high frequency part is obtained by the data fusion result from the forward algorithm and backward algorithm. The full order EIGEN-6C4 was used to obtain the gravity field model data. Meanwhile, the bias part was also obtained from EIGEN-6C4 because the ground gravity data was unavailable in this flight test:

where is the high frequency part of gravity disturbance, is the origin result of gravity disturbance and is the linear fitting result of gravity disturbance.

where is the result of gravity disturbance, is the bias from the ground gravimetry and upward extension algorithm, is the linear coefficient obtained by the gravity field model, is the variation of distance and is the high frequency part of gravity disturbance obtained by the data fusion.

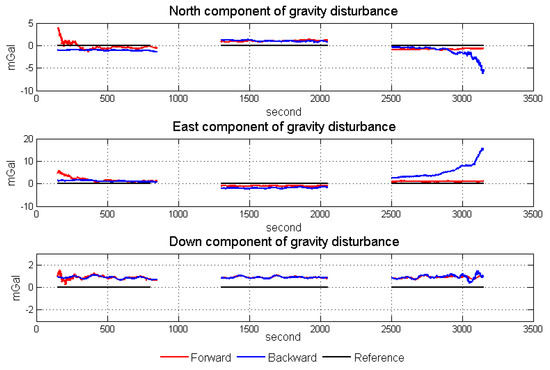

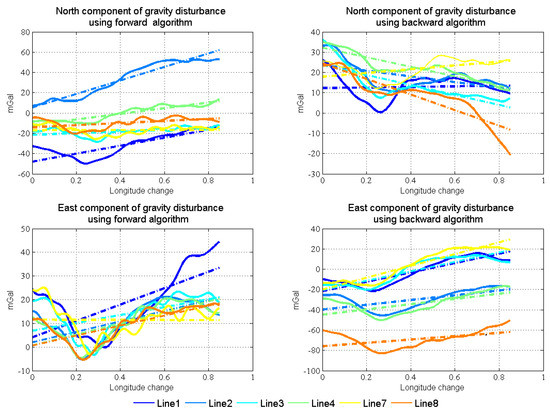

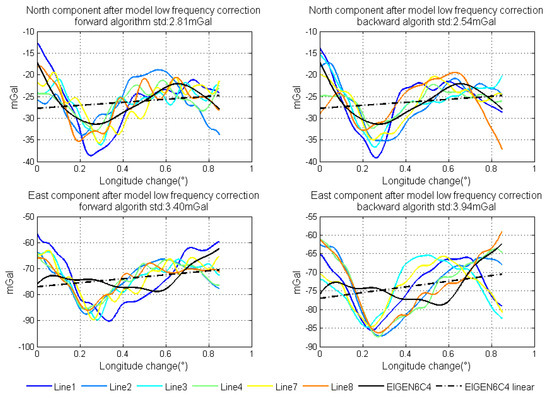

Figure 16 shows the linear fitting results of the two horizontal components. Figure 17 shows the north and east components of gravity disturbance after correction by the gravity model. After correcting the error in the low frequency band, the repeatability has been promoted a lot in all conditions and the different performances between the two algorithms still exist. The north component obtained from the backward algorithm and the east component obtained from the forward algorithm are better than those obtained from another algorithm. Thus, there is considerable potential for accuracy improvement by fusing the data from two algorithms.

Figure 16.

Two horizontal components’ linear fitting results in normal lines.

Figure 17.

North and east components of gravity disturbance after correction by model.

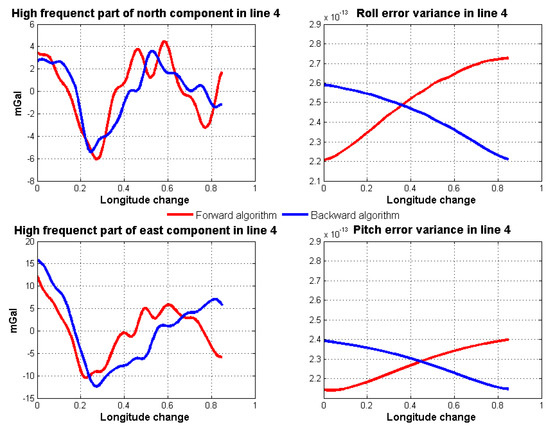

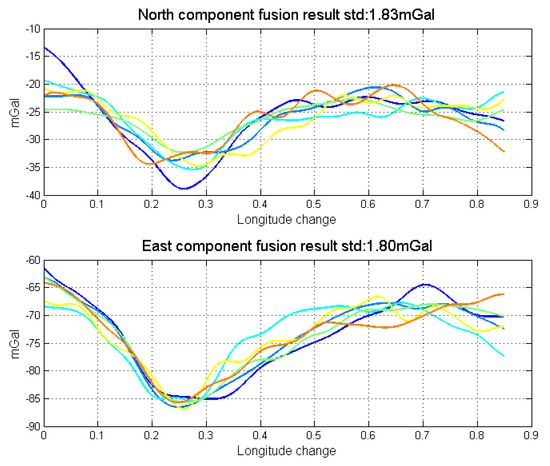

Through gravity model correction, the error in low frequency, especially specific measurement error, has been largely eliminated. The residual error mainly stems from the attitude error. The residual error in the north component was mainly caused by the east attitude (pitch) error, while the residual error in the east component mainly originated from the north attitude (roll) error. Thus, variance of north and east attitude error in the Kalman filter could be used as a weight in the optimal linear smoothing. Figure 18 shows the estimated variances of attitude error and the high frequency part of gravity disturbance horizontal components in line 4. As shown in Equations (10) and (11), if the variance is larger, the final result is less affected by corresponding results. The fusion results by the method are shown in Figure 19. The detail repeatability in 6 km resolution is shown in Table 5. After the application of the method, the repeatability of gravity disturbance horizontal components can reach the 1.83 mGal and 1.80 mGal under resolution of 6 km. Compared with the results shown in Figure 14, there are obvious improvements in the repeatability of both components and the clutter signal is also reduced, which prove the effectiveness of the accuracy improvement method.

Figure 18.

Estimated variances of attitude error and high frequency part of gravity disturbance horizontal components in line 4.

Figure 19.

Data fusion results by the accuracy improvement method.

Table 5.

Repeatability of data fusion results (mGal).

5. Discussion

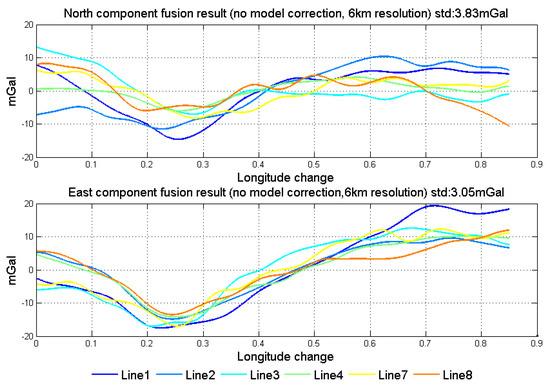

The effectiveness and practicability has been validated by an actual strapdown gravimetry test. In this section, WCF is compared with the optimal linear smoothing as an alternative data fusion method. The results of horizontal gravity disturbance in higher resolutions are also presented. Furthermore, the performance of the accuracy improvement method under the condition of the no gravity field model correction is discussed.

5.1. Apply Wavenumber Correlation Filter to Fuse the Results from Two Algorithms

The optimal linear smoothing is successfully applied to the combination of forward and backward algorithms. Another method for taking advantage of both forward and backward algorithms is wavenumber correlation filter (WCF) [10]. The basic hypothesis of the WCF is that the measurement results should be tightly correlated, while the systematic errors should be less correlated. The WCF decomposes time domain data into frequency bands using Fourier transformation, and then computes the correlation coefficients at the same frequency point that follows Equation (17):

where is the correlation coefficients at frequency point k, is the Fourier transformation result of data series X at frequency point k and is the Fourier transformation result of data series Y at frequency point k.

Based on the correlation coefficients and a given threshold T, if the correlation coefficient is smaller than the threshold at certain frequency, the component at that frequency is considered to be the noise. In order to extract signals that are directly correlated, WCF filters only pass the frequency components, at which the is larger than the threshold, and then it is eliminated according to Equation (18). Finally, the gravity signal reconstruction can be achieved by an inverse Fourier transform. When the WCF was applied in gravimetry, it usually fused data from two different repeat lines to reduce error, which is inefficient. Fortunately, combining the data from forward and backward algorithms can largely solve the problem of inefficiency:

where T is threshold and is the frequency domain data after filtering.

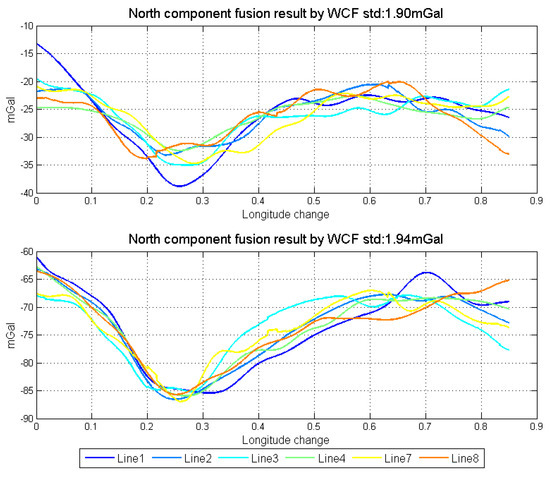

Fusing the data from forward and backward algorithms meets the requirement of WCF and can conquer the premise of repeat lines. When use WCF to eliminate the error, threshold selection is directly related to the performance of the filter. Figure 20 shows the results of using WCF to fuse the data, in which the threshold is given as −0.6. Comparing the two fusion methods, the optimal linear smoothing algorithm is better than WCF. It is because WCF is the average algorithm in the frequency domain after eliminating the weak correlated components, in which the characteristics of the data itself are also not considered.

Figure 20.

Data fusion results by WCF.

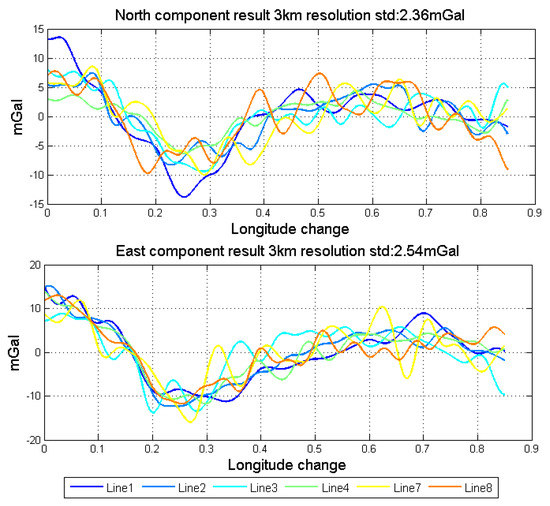

5.2. The Result in Higher Resolution

As mentioned, the vector gravimetry suffers more from the attitude error when compared with the scalar gravimetry. In the actual flight test, the repeatability of scalar results in normal lines could reach 1 mGal under the resolution of 3 km, while the repeatability of horizontal components of gravity disturbance vector results is about 1.8 mGal under the resolution of 6 km after data fusion. When we improve the resolution, the repeatability will reduce to some degree. Changing the cut-off frequency of the low pass filter, the repeatability of different resolutions are shown in Table 6. Figure 21 shows the results in 3 km resolution. Although the performance dose not decline much with the improvement of resolution, the noise part of the gravity disturbance vector signal significantly enhanced. This phenomenon is mainly caused by the insufficient attitude measurement accuracy. Thus, the essential way to improve the accuracy of vector gravimetry is to develop the proper algorithm, such as Refs. [18,19]. Another fundamental approach is to use the higher performance sensors, especially high precision gyroscopes, the bias stability of which should be better than 0.002 deg/h or even higher.

Table 6.

Repeatability in different resolutions (mGal).

Figure 21.

Horizontal components fusion result in 3 km resolution.

5.3. The Repeatability under the Absence of Gravity Field Information

The gravity field model has good accuracy in the low frequency part of the gravity disturbance vector, but the value from the gravity field model usually has a deviation when compared with the true value in a certain area. However, if the accuracy of the gravity field model is poor or the deviation between the gravity field model and true value is no longer constant, what is the performance of the method shown in the paper?

We suppose that the base point information and method of end-matching could be applied in this kind of condition. Thus, after fusing the data from forward and backward algorithms, the mean value could be subtracted from the horizontal components (zero-mean transformation), the result of which is shown in Figure 22. Compared with the result shown in Figure 19, there is clear drift in the two horizontal components, which are mainly caused by the error in the low frequency part. Thus, we can conclude that accurate prior information and high stability accelerometers are very helpful to measure the true gravity field information.

Figure 22.

Results in 6 km resolution under the condition of no gravity field model correction.

In the following research, improvements in algorithms and hardware should be considered at the same time to comprehensively promote the performance of airborne vector gravimetry.

6. Conclusions

The research presented here developed an effective approach for strapdown gravimetry accuracy improvement. The advantages of the method can be summarized as follows:

- The backward algorithm not only shows different characteristics in the standalone inertial calculation, but also has different convergence in the Kalman filter, which provides a backtracking result for the vector gravimetry.

- Fusion of the data from forward and backward algorithms satisfies the precondition of error compensation and the repeat lines are not needed.

- Based on an optimal linear filter, the data can be fused optimally rather than empirically.

The accuracy improvement method was given based on the promising simulation results. Applying to the data from an actual flight test, the improved gravity disturbance vector results can be obtained, especially for the horizontal components. The vertical components is 1 mGal under the resolution of 3 km. After applying the method, the north gravity disturbance component could reach the accuracy of 1.83 mGal and the east gravity disturbance component could reach the 1.80 mGal, both of which is under the resolution of 6 km. For considering the characteristics of the data itself, the optimal linear smoothing algorithm is better than WCF when fusing the results from two algorithms. Furthermore, the repeatability does not decline much with the improvement of resolution. To further test the method, the condition of no gravity field model correction is also presented, in which the method still shows good performance.

For further studies, the accuracy of the gravity disturbance vector obtained from the accuracy improvement method should be compared to the accurate gravity field control data. To fully achieve the goal of high accuracy airborne vector gravimetry, the excellent algorithm and high accuracy hardware system should be applied at the same time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W. (Minghao Wang) and R.Y.; Methodology, M.W. (Minghao Wang) and S.C.; Software, M.W. (Minghao Wang) and S.C.; Validation, J.C., M.W. (Meiping Wu) and K.Z.; Formal Analysis, M.W. (Minghao Wang) and R.H.; Data Curation, M.W. (Minghao Wang), J.C. and R.Y.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.W. (Minghao Wang); Writing—Review & Editing, all authors; Supervision, M.W. (Meiping Wu); Project Administration, J.C. and M.W. (Meiping Wu); Funding Acquisition, J.C., M.W. (Meiping Wu) and K.Z.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2017YFC0601701, 2017YFC0601703, 2016YFC0303002), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 61603401), Funding of Hunan Science and Technology Project (No. 2017RS3045) and Youth Innovation Fund of Key Laboratory of China Aero Geophysical Survey and Remote Sensing Center for Land and Resources (No. 2016YFL07).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the China Aero Geophysical Survey and Remote Sensing Center for Land and Resources for its support with the testing procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The details of the sub-matrix in Equation (8) is shown as follows:

where L is the latitude, H is the height, is the meridian radius of earth and is the prime circle radius of earth.

References

- Schwarz, K.P.; Li, Z. An Introduction to Airborne Gravimetry and Its Boundary Value Problems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 312–358. [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg, R.; Olesen, A.V. Airborne Gravity Field Determination; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Skourup, H.; Forsberg, R.; Sørensen, S.L.S.; Andersen, C.J.; Schäfer, U.; Liebsch, G.; Ihde, J.; Schirmer, U. Strengthening the Vertical Reference in the Southern Baltic Sea by Airborne Gravimetry. Int. Assoc. Geod. Symp. 2009, 133, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Glennie, C.L.; Schwarz, K.P.; Bruton, A.M.; Forsberg, R.; Olesen, A.V.; Keller, K. A comparison of stable platform and strapdown airborne gravity. J. Geod. 2000, 74, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, A.M.; Hammada, Y.; Ferguson, S.; Schwarz, K.P. A Comparison of Inertial Platform, Damped 2-axis Platform and Strapdown Airborne Gravimetry. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Kinematic Systems in Geodesy Geomatics and Navigation the Banff, Banff, AB, Canada, 5–8 June 2001; pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S.K.; Meiping, W.U.; Zhang, K.D.; Cao, J.L. The first airborne scalar gravimetry system based on SINS/DGPS in China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2013, 56, 2198–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Schwarz, K.P. Flight test results from a strapdown airborne gravity system. J. Geod. 1998, 72, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, O. GT-1A and GT-2A Airborne Gravimeters: Improvements in Design, Operation, and Processing from 2003 to 2010; Canadian Micro Gravity Ltd.: Aurora, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, S.; Sander, L.; Ferguson, S. SGL AIRGrav anomaly detection from modeling and field data using advanced acquisition and processing. In Proceedings of the Gem Beijing, Beijing, China, 10–13 October 2011; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, J.H.; Jekeli, C. A new approach for airborne vector gravimetry using GPS/INS. J. Geod. 2001, 74, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Strapdown INS/DGPS airborne gravimetry tests in the Gulf of Mexico. J. Geod. 2011, 85, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, D.; Nielsen, J.E.; Ayres-Sampaio, D.; Forsberg, R.; Becker, M.; Bastos, L. Drift reduction in strapdown airborne gravimetry using a simple thermal correction. J. Geod. 2015, 89, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiping, W.; Xihua, Z.; Jvliang, C.; Kaidong, Z.; Shaokun, C.; Ruihang, Y.; Minghao, W.; Junbo, T. The New Airborne Gravimeter Using the “Strapdown+Platform” Scheme. PNT 2017, 4, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bidel, Y.; Zahzam, N.; Blanchard, C.; Bonnin, A.; Cadoret, M.; Bresson, A.; Rouxel, D.; Lequentrec-Lalancette, M.F. Absolute marine gravimetry with matter-wave interferometry. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampietro, D.; Mansi, A.; Capponi, M. A New Tool for Airborne Gravimetry Survey Simulation. Geosciences 2018, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Moving Base INS/GPS Vector Gravimetry on a Land Vehicle. Ph.D. Thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Comparing the Kalman filter with a Monte Carlo-based artificial neural network in the INS/GPS vector gravimetric system. J. Geod. 2009, 83, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senobari, M.S. New results in airborne vector gravimetry using strapdown INS/DGPS. J. Geod. 2010, 84, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhang, K.; Wu, M.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y. An iterative method for the accurate determination of airborne gravity horizontal components using strapdown inertial navigation system/global navigation satellite system. Geophysics 2015, 80, G119–G129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhang, K.; Wu, M. Improving airborne strapdown vector gravimetry using stabilized horizontal components. J. Appl. Geophys. 2013, 98, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, W.; Lu, J.W.L. A Fast SINS Initial Alignment Scheme for Underwater Vehicle Applications. J. Navig. 2013, 66, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Yan, W.; Xu, D. On reverse navigation algorithm and its application to SINS gyro-compass in-movement alignment. In Proceedings of the Control Conference, CCC 2008, Kunming, China, 16–18 July 2008; pp. 724–729. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, D.; Potter, J. The optimum linear smoother as a combination of two optimum linear filters. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1969, 14, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titterton, D.; Weston, J. Strapdown Inertial Navigation Technology. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2005, 20, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Nassar, S.; El-Sheimy, N. Two-Filter Smoothing for Accurate INS/GPS Land-Vehicle Navigation in Urban Centers. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2010, 59, 4256–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, K.P.; Wei, M. Some Unsolved Problems in Airborne Gravimetry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Guo, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L. EGM 2008 and Its Application Analysis in Chinese Mainland. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2009, 38, 283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Sampietro, D.; Capponi, M.; Mansi, A.H.; Gatti, A.; Marchetti, P.; Sansò, F. Space-Wise approach for airborne gravity data modelling. J. Geod. 2017, 91, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, F.; Tao, X.; Duan, R. New optimal smoothing scheme for improving relative and absolute accuracy of tightly coupled GNSS/SINS integration. GPS Solut. 2017, 21, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, M.; Cai, S.; Zhang, K.; Cong, D.; Wu, M. Optimized Design of the SGA-WZ Strapdown Airborne Gravimeter Temperature Control System. Sensors 2015, 15, 29984–29996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.H.; Xiong, S.Q.; Zhou, J.X.; Zhou, X.H. The research on quality evaluation method of test repeat lines in airborne gravity survey. Chin. J. Geophys. 2008, 51, 1538–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerste, C.; Bruinsma, S.; Abrikosov, O.; Lemoine, J.M.; Marty, J.C.; Flechtner, F.; Dahle, C.; Neumayer, H.; Barthelmes, F.; König, R. ESA’s Release 5 Gravity Field Model by the Direct Approach and its Part in the Combined Model EIGEN-6C4. In Proceedings of the AGU Fall Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–19 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).