Abstract

Phosphate minerals have long been used for the production of phosphorus-based chemicals used in many economic sectors. However, these resources are not renewable and the natural phosphate stocks are decreasing. In this context, the research of new phosphate sources has become necessary. Many types of wastes contain non-negligible phosphate concentrations, such as wastewater. In wastewater treatment plants, phosphorus is eliminated by physicochemical and/or biological techniques. In this latter case, a specific microbiota, phosphate accumulating organisms (PAOs), accumulates phosphate as polyphosphate. This molecule can be considered as an alternative phosphate source, and is directly extracted from wastewater generated by human activities. This review focuses on the techniques which can be applied to enrich and try to isolate these PAOs, and to detect the presence of polyphosphate in microbial cells.

1. Introduction

Phosphorus is an essential element required for food production. It has been estimated that about 19.7 MT of phosphorus were extracted from phosphate rocks in 2000. About 15.3 MT were used to produce fertilizers out of this total production. The global growing population induces a progressive increase of fertilizers’ requirement, which means an increasing need for phosphate (P). In this context, the establishment of circular economy applicable to P resources appears obvious [1]. Europe does not have significant P mines and must import ores from the other continents. The total P-reserves have been estimated at 67,000 Tg, and Morocco owns 75% of these known deposits. The remaining percentage mainly belongs to China and the USA. This geopolitical context can generate unexpected increases of fertilizers’ prices, which occurred in 2008 [2]. It is, therefore, necessary to find new P sources. Some wastes contain recoverable P, such as wastewater. A growing attention has been paid to the research of new techniques to remove P from it. More specifically, enhanced biological phosphorus removal (EBPR) is currently applied in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). Sewage sludge resulting from wastewater treatment contains significant quantities of P. This is due to the presence of phosphate accumulating organisms (PAOs) [3]. PAOs have been studied in many research papers. Under specific conditions, these microorganisms can store P as polyphosphate (Poly-P). This ability has been found in bacteria, microalgae, and fungi [3,4,5].

This article focuses on bacterial PAOs and investigates the difficulties encountered in isolation attempts. It presents an inventory of analytical techniques which can be used to detect the presence of PAOs and Poly-P.

2. Techniques for the Isolation of PAOs

The methods used to detect and identify the PAOs are mainly based on the detection of Poly-P and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA). However, the detection of Poly-P itself is much more reliable. Prior to the detection of the polymers which are specific of PAOs (mainly Poly-P), an enrichment step of microorganisms is required. The original samples are mostly collected in WWTPs, in which the metabolism of PAOs is used to remove free phosphate from wastewater by accumulating it as Poly-P [6]. However, it is important to note that the maximal efficiency of PAOs is far from being reached in common EBPR plants.

2.1. Isolation of PAOs

Poly-P is the main form of phosphate accumulation. However, other forms of phosphate storage can be encountered. These components were investigated in a previous review [7]. The P storage compounds can be mineral or organic and depend on the type of microorganism. Low-solubility orthophosphate compounds are the simplest forms of P-accumulation. Some archaea can precipitate MgPO4OH·4H2O (such as Halobacterium salinarium and Halorubrum distributum). These strains concentrate P from aqueous solution during their growth phase. Brevibacteria can also accumulate P as intracellular NH4MgPO4·6H2O. Finally, cyanobacteria accumulate P in their sheaths, combined with calcium. The second type of P storage compounds is organic. Teichoic acid is synthesized by bacteria and is composed of polyol and glycosyl polyol residues bound by phosphodiester bonds. It has been suggested that this molecule is a phosphate reserve. The yeast Kuraishia capsulata can also store phosphate in extracellular phosphomannan [7].

However, in most microorganisms, inorganic Poly-P is the main P reserve, composed of three to several hundred phosphate units. This molecule is a polymeric reserve which also plays a role in the regulation of enzymatic activities, the expression of many genes and the stress adaptation process [7]. Many studies report trials of isolation of PAOs. Acinetobacter was isolated from an EBPR plant, but subsequent studies using culture-independent techniques revealed that this bacterium had a small, but significant, effect in the process. Microlunatus phosphovorus was also isolated and proposed as a PAO, but did not show their characteristics (presence of PHA granules). Molecular techniques allowed to identify Candidatus Accumulibacter phosphatis (Rhodocyclus-related bacteria) as an important subclass involved in P removal at the lab scale, but it was never isolated in pure culture. This subclass is considered as the model showing all the characteristics of a typical bacterial PAO. It is important to note the diversity of this subclass, including two types (I and II), and seven clades in Type II (IIA, IIB, IIC, IID, IIE, IIF and IIG). A recent paper reported the existence of two new clades (IIH and III) and concluded that the configuration of WWTPs has a direct impact on the structure of PAO communities [8]. However, the attempts of isolation of true PAOs have not been successful so far [9].

Some screening techniques have been proposed. Morohoshi et al. [10] developed a method based on the detection of PAOs by the apparition of a blue color due to the hydrolysis of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate on agar plates. Chaudhry and Nautiyal [11] also developed a visual technique based on the use of Toluidine blue-O dye in agar plates containing sodium citrate as the main carbon source. It is important to note that it has not been possible to isolate pure microorganisms seen as true PAOs so far, although many efforts have been made in this respect. This is due to the symbioses in microbial consortia, broken by the isolation techniques.

The isolation attempts have tested many enrichment media containing acetate and citrate as carbon sources [6,12,13,14]. Next, phosphate uptake assays must be achieved in order to confirm the P-accumulation ability of the strain isolated. At this level, the mechanisms of P-accumulation as Poly-P (aerobic /anoxic conditions) and P-release (anaerobic conditions) in bacteria have been described well. However, it must be kept in mind that many parameters affect the capacity of P-accumulation, such as time of anaerobic and aerobic/anoxic phases, pH, temperature, volatile fatty acid composition, PO43−, SO42−, NH4+, K+, Na+, Mg2+, Ca2+, and other metal ion concentrations [11,12,15].

These mechanisms have a direct impact on isolation strategies. Firstly, an anaerobic step is necessary to remove Poly-P before undertaking phosphate uptake assays [6]. Secondly, the detection of Poly-P can be performed only after having grown the bacterial strains in aerobic conditions.

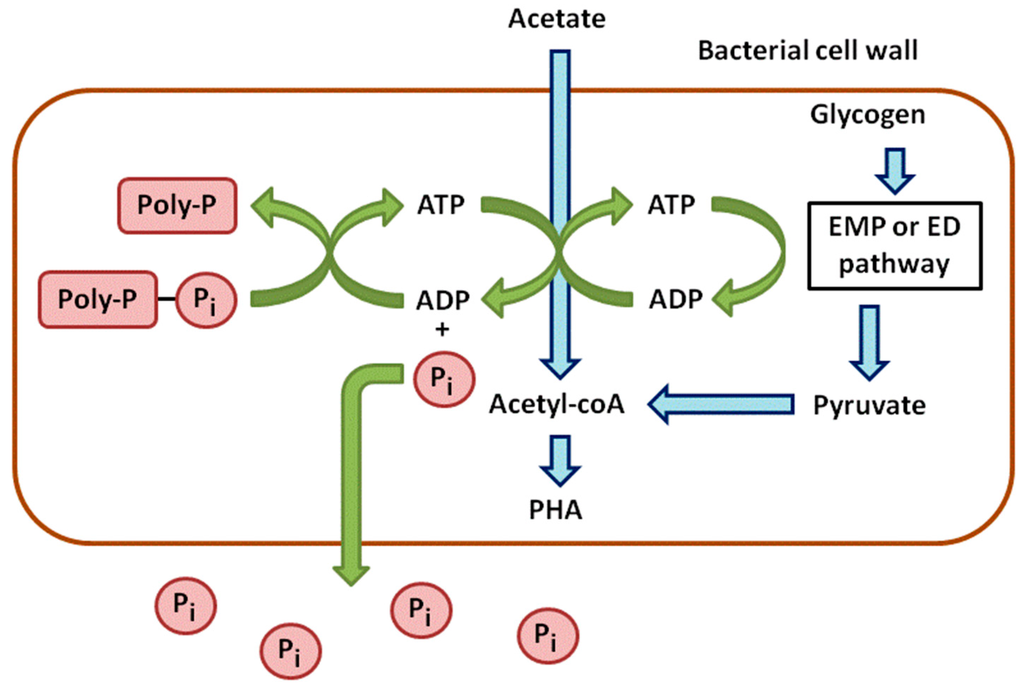

Anaerobic phases can be considered as stress conditions for PAOs. They take up the carbon sources and store them to cope with a potentially long-term absence of oxygen (Figure 1). In wastewater, acetate is the main carbon source and is converted into Acetyl-CoA. This reaction requires energy provided by the hydrolysis of ATP, leading to ADP and the release of P in the medium. Acetyl-CoA is next metabolized into β-hydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), which are carbon storage compounds [9].

Figure 1.

Anaerobic metabolism of phosphorus in phosphate accumulating bacteria.

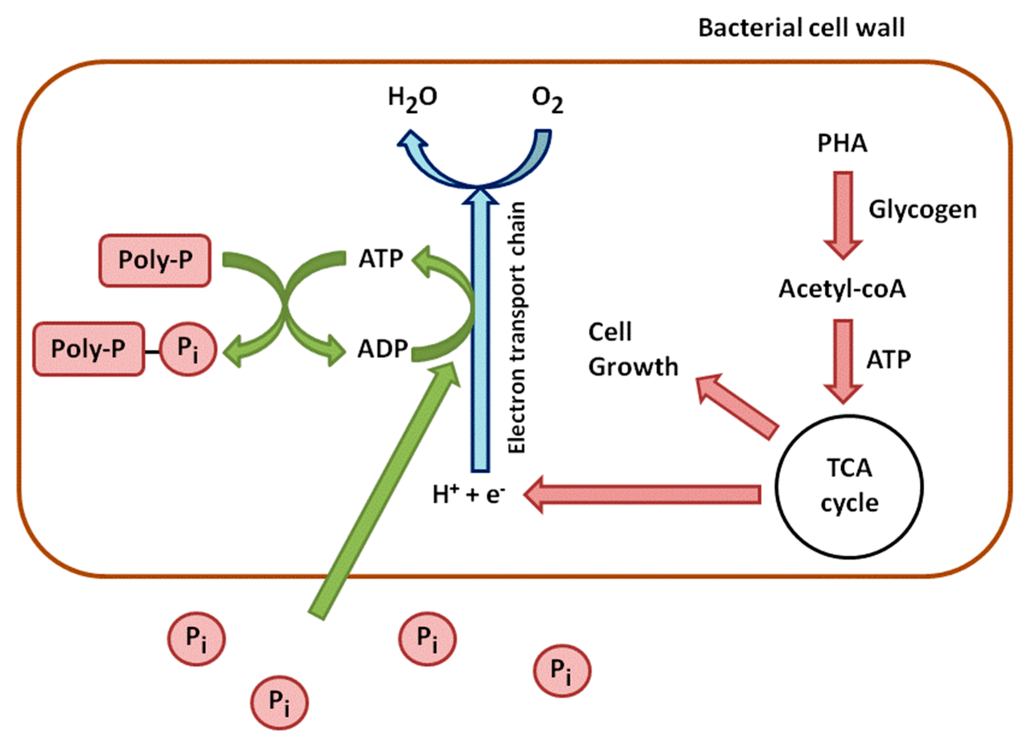

In aerobic conditions, this trend is reversed. PHAs are used for cell growth and the reconstitution of the Poly-P reserves (Figure 2). They are degraded, which leads to the synthesis of Acetyl-CoA, processed through the TCA cycle. The TCA cycle produces energy from oxidation and carbon for new cell growth. A part of this energy is used to take up soluble P from the environment and to incorporate it into Poly-P. Another part of carbon and energy is used to regenerate glycogen [16].

Figure 2.

Aerobic metabolism of phosphorus in phosphate accumulating bacteria.

The case of phosphate accumulating microalgae and mycetes has much less been investigated. However, it has been determined that microalgae accumulate P under stress conditions in specific organites: the acidocalcisomes [17].

The techniques applied to detect Poly-P in microorganisms are diversified and were reviewed in several articles [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Here, we propose a global overview of the methods which can be applied to the detection of PAOs and Poly-P.

2.2. Poly-P Detection and Identification of PAOs

The methods used to detect Poly-P in microbial cells are diversified. The technique used depends on the information required (detection, quantification, degree of polymerization (DP)). They can focus on the PAOs or the Poly-P molecule itself. The methods applicable are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inventory of techniques applied to the detection of PAOs and Poly-P.

2.2.1. Staining Techniques—Light and Epifluorescence Microscopy (LEM)

The most common techniques consist in dying Poly-P with chemicals and observing the Poly-P granules with a light or fluorescence microscope. These qualitative methods were the first used and are still being applied, owing to their simplicity. Loeffler’s methylene blue staining is based on the affinity of anionic Poly-P with methylene blue. The bonds between the dying molecules and Poly-P lead to a specific pink-violet color. Toluidine blue can be used instead of methylene blue because its metachromatic properties are identical. Neisser staining, the second common method, also uses methylene blue combined with a counterstaining solution (Bismark brown or Chrysoidin Y). This protocol improves the detection efficiency by increasing the contrast between Poly-P and the other cell components. Neisser staining protocol leads to a purple color for Poly-P, while the other cellular components are yellowish-brown. Regardless of what technique is used, methylene blue requires an acidic pH to improve the linkages with Poly-P [19]. Neutral red is a pH-sensitive dye, as well. It is used as a probe which detects acidic cellular compartments, such as the ones which contain Poly-P (under the form of “volutin” granules). The neutral form of neutral red is membrane-permeable, while the protonated form is not. Consequently, the acidic compartments tend to accumulate neutral red and can be observed through fluorescence microscopy. The accumulation can be detected on the basis of the absorbance shift: neutral red shows a λmax of 450 nm at pH 8.1 while its protonated form shows a λmax of 535 nm at pH 5.3 [24]. The case of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), another dying molecule, has been reported in many research articles. This dye stains Poly-P granules with a yellow fluorescence when used at high concentrations (see the part “Flow cytometry”). However, DAPI is not specific: it also stains other polymeric ions, such as DNA and lipids [20]. DAPI-DNA fluorescence is blue, but both DAPI-Poly-P and DAPI-lipids show a yellow fluorescence. The fluorescence of DAPI-lipids is shorter in time than the one of DAPI-Poly-P [25]. High DAPI concentrations induce a high fluorescence background, and lower DAPI concentrations coupled with a longer incubation time can be applied [19]. Due to its lack of specificity, the detection of Poly-P with DAPI can be performed after having checked that the reserves of PHA have been totally consumed. This storage polymer can be detected with Sudan black and Nile blue [19]. Other marginal dyes were mentioned in some articles, such as tetracycline (fluorescence based on the linkage with Poly-P) and Fura-2 (fluorescence depending on the competition of Mn2+ affinity with Fura-2 and Poly-P) [26,27].

2.2.2. Flow Cytometry (FC)

Flow cytometry has been cited in many research articles relating to the analysis of Poly-P, mainly with DAPI. The staining reaction is exactly the same as in fluorescence microscopy, but flow cytometry brings much more data [28]. DAPI stains the cells with Poly-P contents higher than 400 μmol/g (dry weight) under a concentration of at least 18 μM (5 to 50 μg/mL). It is considered that a lower concentration in DAPI (0.24 to 5 μM) leads to a blue fluorescence related to bacterial DNA only, while the fluorescence due to Poly-P is yellow and induced by higher DAPI concentrations [27]. Flow cytometry allows the measuring and analysis of multiple physical characteristics, and the particles of interest can be separated from another to make further analyses through cell sorting [28]. Flow cytometry has already been used to detect Poly-P in bacterial cells but also in mammal cells [29]. This technique can be used to locate the Poly-P granules inside the living cells. Many research articles cited DAPI in the topic of Poly-P research [27,28,29,30,31]. Tetracycline can also be used to detect Poly-P through flow cytometry. This antibiotic and its derivatives are usually used in medicine as a labelling molecule for the assessment of calcium deposition. The association of diamagnetic divalent cations (Mg2+, Ca2+) with tetracycline leads to a green fluorescence (emission wavelength of 515 nm), with an excitation wavelength of 390 nm at a neutral pH [27]. This protocol was applied in several research articles [27,32,33].

2.2.3. Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH) Analysis

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is rather linked to the microorganisms themselves and is based on the use of labelled probes which can detect DNA or RNA molecules in situ. This technique is applicable to the identification of microorganisms, the study of gene expression and the study of ecophysiology, which is particularly interesting in the case of PAOs [34]. However, the technique suffers from disadvantages due to its specificity: the sequence of the target molecules and their abundance are required, and the probes must also penetrate the cells with a sufficient efficiency [28]. Albertsen et al. [35] used quantitative FISH with 32 oligonuclotide probes to investigate the composition of the bacterial communities in Danish EBPR plants. FISH analysis allows targeting of specific bacterial clades. Such probes were used to detect the presence of Accumulibacter, a well-known PAO [36,37]. It can also be used to determine the location of PAOs in complex samples [38]. FISH analysis may be combined with other techniques such as in the study of Liu et al. [39], which used DAPI staining, electron microscopy, and X-ray analysis as complementary techniques. The labelled cells can be observed through microscopy techniques [40], but flow cytometry is also applicable. This combination was used in the study of Kim et al. [41] to separate four Accumulibacter clades with Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS). Another possible combination is FISH/micro-autoradiography ((MAR)-FISH), which used labelled substrates (3H, 14C) to investigate the assimilation of nutrient sources according to the conditions used [42].

2.2.4. Extraction Procedures and Polyphosphate Quantification (EXT)

Many articles report extraction procedures of Poly-P followed by its quantification. This procedure is applied to microorganisms the ability to accumulate Poly-P of which has been confirmed. Several problems must be considered: inorganic Poly-P is usually combined with other macromolecules, such as nucleic acids and proteins; the Poly-P solubility depends on the chain length and the presence of cations; the cellular breakdown required to extract Poly-P may lead to undesired modifications, such as changes in chain length, concentrations, and linkage to inorganic molecules. The extraction procedures were reviewed before [20]. The extraction of Poly-P from living cells and the subsequent phosphate (resulting from Poly-P hydrolysis) measurement can be made through different techniques. An extraction by NaOH followed by an acidic hydrolysis with HCl was performed by Aravind et al. [12], before phosphate measurement by the method of molybdate reagent and ascorbic acid. Another research article reported the extraction of different Poly-P fractions (acid-soluble with HClO4, salt-soluble with NaClO4 and HClO4, and alkali-soluble with NaOH) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, before the digestion by HClO4 [43,44]. Poly-P can also be extracted by the method of alkaline hypochlorite [11]. Jimenez-Nuñez et al. [29] used a digestion technique using RNase and DNase followed by an extraction with phenol-chloroform. Next, exopolyphosphatase was used to assess the Poly-P concentration. The extraction with boiling water was also tested, but this technique leads to a partial hydrolysis of Poly-P, which is not desired until the true hydrolysis step [20]. The analysis of phosphate resulting from the hydrolysis step can also be achieved by ion chromatography and inductively coupled plasma (ICP) atomic emission spectrometry (AES) [22,23].

2.2.5. Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE)

Gel electrophoresis can provide data about the DP of Poly-P and requires a Poly-P extraction procedure. The samples must be treated to obtain a soluble form of Poly-P. Cation-exchange resins can be used to reach these conditions, and the migration of standards allows to assess the size of Poly-P molecules. A 6%–30% polyacrylamide gel with 7 M urea was used in several research articles [29,43,44]. Next, the gels can be stained for visualization (Toluidine blue) [44]. Another publication reports the use of PAGE added with DAPI, which led to a yellow fluorescence, while nucleic acids and glycosaminoglycans fluoresced blue [45].

2.2.6. Electron Microscopy (EM)

Electron microscopy is a powerful technique which allows to visualize and locate the Poly-P granules inside cells. The technique used alone cannot quantify the concentrations in Poly-P, but confirms the presence of Poly-P granules. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is usually used with other techniques, such as staining protocols [22,23]. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) can be used to detect high-density granules, such as Poly-P [46]. Electron microscopes are usually equipped with X-ray detectors, which can confirm the elementary composition of the material and the composition of Poly-P granules [43]. Another article reports a complete analysis of phosphate granules in fossil bacteria through several microscopy techniques (SEM, STEM, and Scanning Transmission X-ray Microscopy) [47]. Such a combination was also used in another work which studied the accumulation of Poly-P in Comamonadaceae through SEM combined with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy [48]. A metallization can be applied to the samples to improve the performance of electron microscopy, with osmium tetroxide as in a previous study [13]. Another article investigated the structure of precipitated phosphate minerals (struvite) produced by phosphate forming bacteria through SEM and field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) [49].

2.2.7. X-Ray Analysis Techniques (X-RAY)

X-ray analysis provides information about the composition of the samples and is usually combined with electron microscopes. Energy-dispersive X-ray microanalysis was previously used to assess the composition of Poly-P granules observed through electron microscopy (abbreviated by EM-EDX) [46]. Such combination was used in many studies [43,47,48]. However, the treatments applied before the observation stage must be limited to prevent P losses from the cells [20]. X-ray analyses highlighted the effect of redox conditions on different types of Poly-P: the polymers associated with Mg and K are more easily metabolized than the ones associated with Ca, which means that this latter type of phosphate storage is not influenced by the presence or absence of aerobic conditions [20]. Another useful combined technique is X-ray fluorescence spectromicroscopy, a combination of X-ray spectroscopy and X-ray microscopy. This method was found to be able to elucidate the spatial concentration and speciation of elements at submicron scale in minimally-prepared particulate samples including individual cells. It can analyze thicker samples than electron microscopy and is less restrictive during the preparation procedure [22,23]. The technique developed by Rivadeneyra et al. [49] used an X-ray diffractometer to study struvite crystals produced in culture media. This device allowed to determine the qualitative and quantitative composition of the salts produced by bacteria [49].

2.2.8. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (NMRS)

This non-invasive and non-destructive technique requires labelled substrates (31P) and is applied to PAOs to study their physiology. The labelled substrates are included in Poly-P granules, which allows assessing the substrate degradation, and the synthesis of end-products and metabolites in only one sample [28]. The method can be applied to liquid (culture media) and solid samples and provides an excellent overview of the molecules containing phosphorus (Poly-P but also orthophosphate, pyrophosphate, phosphate mono- and di-esters, phosphonates). However, the interference caused by the heterogeneous physical and chemical properties of the samples and the association of P containing molecules with metallic ions (iron, manganese) must be highlighted. Another point is the similarity of linkage in Poly-P and other molecules containing phosphoanhydride bonds, such as nucleotides. Consequently, NMR usually provides results of the distribution of chemical linkages detected in the sample considered without providing data about the real Poly-P concentration [23]. NMR can also be coupled with bioreactors to follow up the concentrations in P containing metabolites [21]. A recent research article investigated the P transfers under aerobic and anaerobic conditions through NMR spectroscopy and studied the extracellular polymeric substances, focusing on Poly-P [50]. This work showed that NMR can be used as a relevant quantitative technique applicable to the study of PAOs.

2.2.9. RAMAN Spectromicroscopy (RAM)

RAMAN spectromicroscopy requires a simple preparation protocol of samples and may be used with complementary molecular techniques [22,23]. Near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy was first found to be able to provide precious data about carbon, carbonate, N, and P in sediments [51]. RAMAN spectromicroscopy is a related technique which allowed to identify and quantify Poly-P and other storage polymers involved in phosphate accumulation in individual bacterial cells. It also identified orthophosphate, trimers, hexamers, and other oligomers on the basis of the specificity of spectra [23]. RAMAN spectroscopy was also found to be a reliable technique applicable to the study of microbiota composition [52]. More specifically, a research article reports the successful use of RAMAN spectromicroscopy to investigate the dynamics of intracellular Poly-P in PAOs in EBPR process [53]. Further research was applied to Poly-P, PHA, and glycogen, and developed a reliable technique to assess the intracellular distribution and dynamics of these polymers in different metabolic stages of the EBPR process [54]. Another research paper described RAMAN spectromicroscopy as a powerful tool to identify bacteria as PAOs or GAOs on the basis of their intracellular polymers [23]. Indeed, GAOs and PAOs are known to compete to consume carbon sources, and their metabolic properties relating to phosphorus are completely different. GAOs do not participate in the P-removal process [15].

2.2.10. Enzyme Assays (EA)

The metabolism of Poly-P depends on the activity of different types of enzymes. It is synthesized in bacterial cells by Poly-P kinases (PPK1 and PPK2) and degraded by exopolyphosphatase (PPX). A first technique to detect Poly-P in samples consists in using a yeast exopolyphosphatase on the extract and measuring the resulting phosphate concentration. Another enzyme assay is based on the action of PPK, which converts ADP to ATP in the presence of Poly-P [21]. After the enzymatic hydrolysis, the reaction products can be analyzed by thin-layer chromatography or gel electrophoresis [46]. Other techniques based on the activity of Poly-P-glucokinase and Poly-P AMP phosphotransferase were also reported [20]. Such enzyme assays require a good quality of the extract supposed to contain Poly-P.

2.2.11. Cryoelectron Tomography and Spectroscopic Imaging (CTSI)

This technique was used in the study of Comolli et al. [55] to investigate polymeric structures in Caulobacter crescentus and Deinococcus grandis. Here, the study of subcellular structure and subcellular bodies in whole bacteria was undertaken. This combination led to the identification of P-rich and carbon-rich bodies in Caulobacter crescentus, and provided structural information without altering the granules. P-rich granules were also detected in Deinococcus grandis.

2.2.12. Mass Spectrometry (MS)

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was tested on orthophosphate, pyrophosphate, tripolyphosphate, and tetrapolyphosphate [21]. This technique shows a high selectivity and does not require pre-separation steps. However, this method was not really investigated on samples extracted from EBPR experiments or pure cultures of PAOs.

2.2.13. Proteic Affinity (PA)

Saito et al. [56] developed a proteic affinity technique which leads to the detection of Poly-P. The principle is based on the use of a recombinant Poly-P binding domain (PPBD) of an exopolyphosphatase from Escherichia coli. The PPBD showed a high affinity for long-chain Poly-P and a low affinity for short-chain Poly-P. The technique was found to be able to locate Poly-P by an immunocytochemical method.

2.2.14. “Omics” Techniques (OMICS)

Omics techniques have been widely used in many studies over the past decade. Here, we present some applications of those data-rich methods to the study of PAOs. Metagenomics is mainly based on the analysis of 16S rRNA extracted from complex microbiotas, and is perfectly applicable to the study of the strains involved in the EBPR process [57]. This technique was combined with quantitative FISH in a previous work and was applied to the bacterial community involved in EBPR process [35]. Metatranscriptomics, based on the analysis of mRNA sequences, has also been used to investigate the EBPR process. Such study was successfully applied to the research of Poly-P kinase sequences and focused on Accumulibacter [58]. Finally, metaproteomics provides data about the expression of proteins in complex samples, but the results obtained by this method must be considered carefully. Genes are regulated at the transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels, and another point comes from the short half-life of gene products. Consequently, metaproteomics’ data should not be considered alone [57]. The study of Wilmes et al. [59] reported a metaproteomic analysis of bacterial consortia according to the efficiency of the EBPR process. A successful EBPR process led to the detection of a majority of Accumulibacter, while the failure of the process led to a majority of α-Proteobacteria [58,59]. The study of Wexler et al. [60] used radiolabelled metaproteomics to investigate the effect of anaerobic and aerobic conditions on the EBPR process. Another combined study was based on proteogenomics and assessed the role of Accumulibacter in the EBPR process, taking the other co-existing strains into account. The metaproteome was found to be very close in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, and denitrification, fatty acid cycling and the glyoxylate bypass were revealed to have an important role in the EBPR process [59].

Table 2 summarizes the specificities of each technique described above.

Table 2.

Specificities of techniques applied to the detection of PAOs and Poly-P.

3. Conclusions

Analytical techniques focusing on the isolation or the detection of Poly-P are quite diversified. However, there is evidence that the culture of pure PAOs requires more investigation, and the enrichment of phosphate-accumulating consortia is an alternative to this constraint. This method requires a perfect understanding of the effect of environmental conditions on PAOs in order to establish phosphate accumulation-oriented consortia. This field is still lacking knowledge, although the general metabolism has been described in many publications. Flow cytometry is also a powerful technique applicable to the concentration of PAOs. Screening the genes responsible for phosphate accumulation is another solution which could lead to the engineering of phosphate-accumulating strains, more efficient than the wild-types. In these conditions, the accumulation of phosphate should be feasible without requiring specific conditions, such as aeration rate or the presence of specific components. Then, the recovery of phosphate from wastewater or other types of liquid effluents will be much easier.

Acknowledgments

This project has received European Regional Development Funding through INTERREG IVB “Investing in opportunities”. This work was supported by the BioRefine Project (INTERREG IVB NWE Programme) (ref. 320J-BIOREFINE) and the RENEW Project (ref. 317J-RENEW).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADP | Adenosine Diphosphate |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| CTSI | Cryoelectron Tomography and Spectroscopic Imaging |

| DAPI | 4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole |

| DP | Degree of Polymerisation |

| EA | Enzyme Assays |

| EBPR | Enhanced Biological Phosphorus Removal |

| EM | Electron Microscopy |

| EM-EDX | Electron Microscopy—Energy-dispersive X-ray |

| ESI-MS | Electrospray Ionisation Mass Spectrometry |

| EXT | Extraction procedures |

| FACS | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting |

| FC | Flow Cytometry |

| FESEM | Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FISH | Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization |

| GAO | Glycogen Accumulating Organism |

| ICP-AES | Inductively Coupled Plasma—Atomic Emission Spectrometry |

| LFM | Light and Epifluorescence Microscopy |

| MAR | Micro-autoradiography |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| MT | Megaton |

| NMRS | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy |

| OMICS | “Omics” techniques |

| P | Phosphate |

| PA | Proteic Affinity |

| PAGE | Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| PAO | Phosphate Accumulating Organism |

| PHA | Polyhydroxyalkanoate |

| Poly-P | Polyphosphate |

| PPBD | Polyphosphate Binding Domain |

| PPK | Polyphosphate kinase |

| PPX | Exopolyphosphatase |

| RAM | Raman spectromicroscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| STEM | Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid |

| Tg | Teragram |

| WWTP | Wastewater Treatment Plant |

| X-RAY | X-ray analysis techniques |

References

- Wilfert, P.; Kumar, P.S.; Korving, L.; Witkamp, G.-J.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. The relevance of phosphorus and iron chemistry to the recovery of phosphorus from wastewater: A review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 9400–9414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoumans, O.F.; Bouraoui, F.; Kabbe, C.; Oenema, O.; van Dijk, K.C. Phosphorus management in Europe in a changing world. Ambio 2015, 44, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirota, R.; Kuroda, A.; Kato, J.; Ohtake, H. Bacterial phosphate metabolism and its application to phosphorus recovery and industrial bioprocesses. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2010, 109, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, N. Biological Phosphorus Removal by Microalgae in Waste Stabilisation Ponds; Massey University: Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.; Gan, J.; Hu, B. Screening of Phosphorus-Accumulating Fungi and Their Potential for Phosphorus Removal from Waste Streams. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 177, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, L.L.; Li, D.; Li, X.K.; Huang, R.X.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Xia, G.Q. Phosphorus accumulation by bacteria isolated from a continuous-flow two-sludge system. J. Environ. Sci. 2007, 19, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulakovskaya, T.V.; Vagabov, V.M.; Kulaev, I.S. Inorganic polyphosphate in industry, agriculture and medicine: Modern state and outlook. Process. Biochem. 2012, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Graham, D.W.; Tamaki, H.; Zhang, T. Dominant and Novel Clades of Candidatus Accumulibacter phosphatis in 18 Globally Distributed Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment Plants. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oehmen, A.; Lemos, P.C.; Carvalho, G.; Yuan, Z.; Keller, J.; Blackall, L.L.; Reis, M.A.M. Advances in enhanced biological phosphorus removal: From micro to macro scale. Water Res. 2007, 41, 2271–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morohoshi, T.; Yamashita, T.; Kato, J.; Ikeda, T.; Takiguchi, N.; Ohtake, H.; Kuroda, A. A Method for Screening Polyphosphate-Accumulating Mutants Which Remove Phosphate Efficiently from Synthetic Wastewater. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2003, 95, 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, V.; Nautiyal, C.S. A high throughput method and culture medium for rapid screening of phosphate accumulating microorganisms. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 8057–8062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravind, J.; Saranya, T.; Kanmani, P. Optimizing the Production of Polyphosphate from Acinetobacter Towneri. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2015, 1, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Khoi, L.Q. Isolation and Phylogenetic Analysis of Polyphosphate Accumulating Organisms in Water and Sludge of Intensive Catfish Ponds in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Am. J. Life Sci. 2013, 1, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naili, O.; Benounis, M.; Benammar, L. Screening of Bacteria Isolated from Activated Sludges for Phosphate Removal from Wastewater. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. 2015, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Pratt, S.; Batstone, D.J. Phosphorus recovery from wastewater through microbial processes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 878–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchobanoglous, G.; Stensel, D.; Tsuchihashi, R.; Burton, F. Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Resource Recovery; Eddy, M., Ed.; McGraw-Hill Education-Europe: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulsada, Z.K. Evaluation of Microalgae for Secondary and Tertiary Wastewater Treatment. Ph.D. Thesis, Carleton University Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eixler, S.; Selig, U.; Karsten, U. Extraction and detection methods for polyphosphate storage in autotrophic planktonic organisms. Hydrobiologia 2005, 533, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafim, L.S.; Lemos, P.C.; Levantesi, C.; Tandoi, V.; Santos, H.; Reis, M.A.M. Methods for detection and visualization of intracellular polymers stored by polyphosphate-accumulating microorganisms. J. Microbiol. Methods 2002, 51, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupfer, M.; Glöss, S.; Schmieder, P.; Grossart, H.P. Methods for detection and quantification of polyphosphate and polyphosphate accumulating microorganisms in aquatic sediments. Int. Rev. Hydrobiol. 2008, 93, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.N.; Gómez-García, M.R.; Kornberg, A. Inorganic polyphosphate: Essential for growth and survival. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 605–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majed, N.; Chernenko, T.; Diem, M.; Gu, A.Z. Identification of functionally relevant populations in enhanced biological phosphorus removal processes based on intracellular polymers profiles and insights into the metabolic diversity and heterogeneity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 5010–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majed, N.; Li, Y.; Gu, A.Z. Advances in techniques for phosphorus analysis in biological sources. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezawa, T.; Smith, S.E.; Smith, F.A. Differentiation of polyphosphate metabolism between the extra- and intraradical hyphae of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 2001, 149, 555–563. [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi, D.; Dumas, M.D. Caractérisation Morphologique et Physiologique de la Biomasse des Boues Activées par Analyse d’ Images; Institut National Polytechnique de Lorraine: Nancy, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, B.; Münkner, J.; Oliveira, M.P.; Leitão, J.M.; Müller, W.E.; Schröder, H.C. A novel method for determination of inorganic polyphosphates using the fluorescent dye fura-2. Anal. Biochem. 1997, 246, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günther, S.; Trutnau, M.; Kleinsteuber, S.; Hause, G.; Bley, T.; Röske, I.; Harms, H.; Müller, S. Dynamics of polyphosphate-accumulating bacteria in wastewater treatment plant microbial communities detected via DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2- phenylindole) and tetracycline labeling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 2111–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günther, S.; Röske, I.; Bley, T. Population Structure and Dynamics of Polyphosphate Accumulating Organisms in a Communal Wastewater Treatment Plant; Technischen Universität Dresden: Dresden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Nuñez, M.D.; Moreno-Sanchez, D.; Hernandez-Ruiz, L.; Benítez-Rondán, A.; Ramos-Amaya, A.; Rodríguez-Bayona, B.; Medina, F.; Brieva, J.A.; Ruiz, F.A. Myeloma cells contain high levels of inorganic polyphosphate which is associated with nucleolar transcription. Haematologica 2012, 97, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günther, S.; Hübschmann, T.; Rudolf, M.; Eschenhagen, M.; Röske, I.; Harms, H.; Müller, S. Fixation procedures for flow cytometric analysis of environmental bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 2008, 75, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyauchi, R.; Oki, K.; Aoi, Y.; Tsuneda, S. Diversity of nitrite reductase genes in “Candidatus accumulibacter phosphatis”-dominated cultures enriched by flow-cytometric sorting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5331–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günther, S.; Koch, C.; Hübschmann, T.; Röske, I.; Müller, R.A.; Bley, T.; Harms, H.; Müller, S. Correlation of community dynamics and process parameters as a tool for the prediction of the stability of wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehlig, L.; Petzold, M.; Heder, C.; Gunther, S.; Muller, S.; Eschenhagen, M.; Roske, I.; Roske, K. Biodiversity of Polyphosphate Accumulating Bacteria in Eight WWTPs with Different Modes of Operation. J. Environ. Eng. 2013, 139, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Yang, Q.; Luo, K. Biological phosphorus removal from real wastewater in a sequencing batch reactor operated as aerobic/extended-idle regime. Biochem. Eng. J. 2013, 77, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertsen, M.; Benedicte, L.; Hansen, S.; Saunders, A.M.; Nielsen, P.H. A metagenome of a full-scale microbial community carrying out enhanced biological phosphorus removal. ISME J. 2012, 2012, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broch, S.P. Operation and Control of SBR Processes for Enhanced Biological Nutrient Removal from Wastewater; Universitat de Girona: Girona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Burow, L.C.; Mabbett, A.N.; Blackall, L.L. Anaerobic glyoxylate cycle activity during simultaneous utilization of glycogen and acetate in uncultured Accumulibacter enriched in enhanced biological phosphorus removal communities. ISME J. 2008, 2, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kreuk, M.K.; Heijnen, J.J.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Simultaneous COD, nitrogen, and phosphate removal by aerobic granular sludge. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005, 90, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.T.; Nielsen, A.T.; Wu, J.H.; Tsai, C.S.; Matsuo, Y.; Molin, S. In situ identification of polyphosphate- and polyhydroxyalkanoate-accumulating traits for microbial populations in a biological phosphorus removal process. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 3, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Kim, Y.; Lee, D.; Shim, H.; Kim, J. Characteristics of Denitrifying Phosphate Accumulating Organisms in an Anaerobic-Intermittently Aerobic Process. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2006, 23, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Song, J.J.; Park, W.; Jeon, C.O. Analysis of the fine-scale population structure of “candidatus accumulibacter phosphatis” in enhanced biological phosphorus removal sludge, using fluorescence in situ hybridization and flow cytometric sorting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 3825–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, S.; Ahn, J.; Seviour, R.J. Ecophysiology of polyphosphate-accumulating organisms and glycogen-accumulating organisms in a continuously aerated enhanced biological phosphorus removal process. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 105, 1412–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breus, N.A.; Ryazanova, L.P.; Suzina, N.E.; Kulakovskaya, N.V.; Valiakhmetov, A.Y.; Yashin, V.A.; Sorokin, V.V.; Kulaev, I.S. Accumulation of inorganic polyphosphates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under nitrogen deprivation: Stimulation by magnesium ions and peculiarities of localization. Microbiology 2011, 80, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breus, N.A.; Ryazanova, L.P.; Dmitriev, V.V.; Kulakovskaya, T.V.; Kulaev, I.S. Accumulation of phosphate and polyphosphate by Cryptococcus humicola and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the absence of nitrogen. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012, 12, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.A.; Morrissey, J.H. Sensitive fluorescence detection of polyphosphate in polyacrylamide gels using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindol. Electrophoresis 2007, 28, 3461–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, S.; Jerez, C.A. Copper ions stimulate polyphosphate degradation and phosphate efflux in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 5177–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosmidis, J.; Benzerara, K.; Menguy, N.; Arning, E. Microscopy evidence of bacterial microfossils in phosphorite crusts of the Peruvian shelf: Implications for phosphogenesis mechanisms. Chem. Geol. 2013, 359, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Batstone, D.J.; Keller, J. Biological phosphorus removal from abattoir wastewater at very short sludge ages mediated by novel PAO clade Comamonadaceae. Water Res. 2015, 69, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivadeneyra, A.; Gonzalez-Martinez, A.; Gonzalez-Lopez, J.; Martin-Ramos, D.; Martinez-Toledo, M.V.; Rivadeneyra, M.A. Precipitation of phosphate minerals by microorganisms isolated from a fixed-biofilm reactor used for the treatment of domestic wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 3689–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Lo, V.K.; Thompson, J.R.; Koch, F.A.; Liao, P.H.; Mavinic, D.S.; Atwater, J.W. Recovery of phosphorus from dairy manure: A pilot- scale study. Environ. Technol. 2015, 36, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malley, D.F.; Lockhart, L.; Wilkinson, P.; Hauser, B. Determination of carbon, carbonate, nitrogen, and phosphorus in freshwater sediments by near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy: Rapid analysis and a check on conventional analytical methods. J. Paleolimnol. 2000, 24, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, K.C.; Urlaub, E.; Gapes, J.R. Single-cell analysis of bacteria by Raman microscopy: Spectral information on the chemical composition of cells and on the heterogeneity in a culture. J. Microbiol. Methods 2000, 42, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majed, N.; Matthäus, C.; Diem, M.; Gu, A.Z. Evaluation of intracellular polyphosphate dynamics in enhanced biological phosphorus removal process using Raman microscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 5436–5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majed, N.; Gu, A.Z. Application of Raman microscopy for simultaneous and quantitative evaluation of multiple intracellular polymers dynamics functionally relevant to enhanced biological phosphorus removal processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 8601–8608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comolli, L.R.; Kundmann, M.; Downing, K.H. Characterization of intact subcellular bodies in whole bacteria by cryo-electron tomography and spectroscopic imaging. J. Microsc. 2006, 223, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, K.; Ohtomo, R.; Kuga-Uetake, Y.; Aono, T.; Saito, M. Direct labeling of polyphosphate at the ultrastructural level in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by using the affinity of the polyphosphate binding domain of Escherichia coli exopolyphosphatase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5692–5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, C.M.; O’Leary, N.D.; Dobson, A.D.; Marchesi, J.R. The contribution of “omic”-based approaches to the study of enhanced biological phosphorus removal microbiology: Minireview. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009, 69, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, K.D.; Dojka, M.A.; Pace, N.R.; Jenkins, D.; Keasling, J.D. Polyphosphate Kinase from Activated Sludge Performing Enhanced Biological Phosphorus Removal. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 4971–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmes, P.; Wexler, M.; Bond, P.L. Metaproteomics provides functional insight into activated sludge wastewater treatment. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, M.; Richardson, D.J.; Bond, P.L. Radiolabelled proteomics to determine differential functioning of Accumulibacter during the anaerobic and aerobic phases of a bioreactor operating for enhanced biological phosphorus removal. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 3029–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).