Abstract

Small mammals play a central role in northern ecosystems, yet their diversity and habitat associations remain poorly documented in the subarctic mountains of northwestern Canada. I assessed small mammal assemblages across elevational and habitat gradients in Tombstone Territorial Park, located in the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone. My objectives were to document small mammal diversity and habitat associations. In 2005, small mammals were sampled at 27 sites representing seven common habitat types, ranging from lowland boreal forest to subalpine shrublands and alpine tundra. Twelve species of voles, lemmings, mice, and shrews were captured. Species richness and relative abundance were highest in lowland habitats and declined with increasing elevation. Alpine habitats supported fewer, highly specialized species. Several species were restricted to lowland habitats, whereas two species occurred exclusively in alpine tundra. Canonical correspondence analysis revealed a separation of species assemblages based primarily on moisture. These findings demonstrated that moisture, elevation, and habitat type structured small mammal assemblages in this northern mountain landscape. As a first approximation of small mammal assemblages in the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone, I provide a historical baseline for detecting recent and future ecological change. Climate change may facilitate the range expansion of lowland species and alter alpine assemblages, with potential consequences for community composition, trophic interactions, and ecosystem processes, highlighting the importance of small mammal monitoring in a rapidly warming subarctic.

1. Introduction

Globally, small mammals have been considered useful ecological indicators of ecosystem health and integrity, including in Africa [1,2,3,4], Europe [5,6,7,8,9], North America [10,11,12,13,14,15,16], South America [17], and Asia [18]. In northern terrestrial ecosystems, small mammals occupy a central role because they influence vegetation dynamics, predator populations, and the flow of energy through food webs [15,16,19,20,21]. Rodents and shrews are often the most abundant mammals in northern terrestrial ecosystems and can exert strong bottom-up effects, particularly during periods of high population density [15,16,19,20,21]. Despite their global ecological significance, small mammal communities in northern mountain landscapes remain comparatively understudied, especially across elevational and habitat gradients that span forested lowlands to alpine tundra.

Mountain landscapes present sharp environmental gradients over relatively short spatial scales, including changes in temperature, moisture, vegetation structure, and snow cover, making them hotspots for biodiversity [22,23,24,25]. These gradients can structure small mammal assemblages by constraining species distributions and shaping patterns of diversity and abundance [9,26,27,28]. In northern mountainous regions, where climatic conditions are severe, such gradients may be especially important in determining habitat associations. Understanding how faunal assemblages vary broadly across habitats is essential for establishing baseline ecological knowledge and for assessing responses to climatic change [29,30,31].

In northwestern Canada, most research on high latitude assemblages of small mammals has been conducted across various boreal and arctic ecozones [11,32,33]. In contrast, small mammal assemblages in the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone, situated between more southern boreal and more northern arctic ecozones, have received relatively little attention. Although several museum collection campaigns documented species presence in the northern Yukon [34,35,36], more systematic assessments of small mammal diversity, relative abundance, and habitat associations within the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone are unavailable. A national status report on trends in the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone considered the state of food webs and explicitly concluded that a critical information gap exists regarding small mammals, which are not monitored [37]. Indeed, among 1167 studies published between 1900 and 2021 on the broad topic of “ecosystems, biodiversity and wildlife” in Canada’s mountainous ecozones, <1% of those studies were conducted in the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone [25].

The Taiga Cordillera Ecozone is characterized by rugged topography, extensive alpine terrain, discontinuous permafrost, and a mosaic of boreal forest and tundra habitats [37,38]. Tombstone Territorial Park (hereafter, Tombstone), located in central Yukon, Canada, provides an exceptional opportunity to examine subarctic small mammal assemblages across a range of habitat types within this ecozone, as the park encompasses extensive lowland boreal forests, shrublands, sub-alpine communities, and diverse alpine tundra habitats [39,40]. This heterogeneity provides a pristine landscape for assessing how small mammals partition habitats and how assemblage composition changes along elevational, moisture, and vegetative gradients that are characteristic of mountainous landscapes both regionally and globally [23,26].

Baseline inventories of small mammals are particularly important in protected areas [1,3,4,18,41,42,43], where long-term ecological monitoring increasingly requires quantitative reference conditions [44]. Northern regions are experiencing rapid climatic warming, with associated changes in vegetation, permafrost, snow, and other environmental conditions [13,37,40] that are likely to alter small mammal distributions and community structure. For instance, a landscape trend analysis using remotely sensed data between 1986 and 2021 indicated that 24% of Tombstone experienced significant landscape change, including increased wetting, vegetation succession, wildfires, and insect outbreaks [40], all of which may influence the composition and distribution of small mammal assemblages. Documenting patterns of diversity and habitat associations is therefore essential for detecting change and for interpreting shifts in species ranges and assemblage composition. As such, the objectives of my study were to (1) document the diversity of small mammal species and the composition of assemblages in Tombstone; (2) compare species richness, diversity, and evenness among common lowland, sub-alpine, and alpine habitat types; (3) evaluate habitat associations and niche breadth of the most common species; (4) test the response of species composition to moisture and an elevational gradient; and (5) assess similarity among assemblages across habitat types.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Established in 1999, Tombstone Territorial Park (64.5° N, 138.5° W) protects 2200 km2 of scenic viewscapes and undisturbed wildlife habitat in the Ogilvie Mountains of central Yukon, Canada. Much of the park is above treeline (≥800 m above sea level [mASL]); however, extensive tracts of boreal forest occur along major river corridors and valleys at lower elevations [39,40]. Elevation ranges from 416 to 2344 mASL. Vast alpine plateaus occur between rugged mountain peaks and ridges. Tombstone comprises three bioclimatic zones, which are distributed based on elevation and include Subarctic Woodland, Subarctic Subalpine, and Subarctic Alpine Tundra [45,46].

Tombstone is within the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone, which occupies much of the northern half of the Yukon. At 352,089 km2, it is the most northern and smallest ecozone within Canada’s boreal forest [37]. Geologically, the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone contains the northernmost arc of the Rocky Mountains and is characterized by steep, rugged topography interspersed by narrow valleys, much of which is underlaid by permafrost [37,38]. Land cover broadly consists of low vegetation and barren (i.e., tundra; 45%), shrubland (33%), forests (18%), burned areas (3%), and glaciers (1%; [37]). The climate is continental subarctic, meaning it is strongly seasonal, with extremely cold, long, dark winters and short, cool summers. Mean annual temperature is −5 °C, with a mean July temperature of 9 °C [38]. Mean annual temperatures have risen about 2 °C in the past 50 years, resulting in dynamic patterns of vegetation change [37,45]. Average annual precipitation is ~700 mm, much of which falls as snow [37,38]. A diverse range of subarctic mammals occur in this ecozone, including collared pikas (Ochotona collaris), hoary marmots (Marmota caligata), arctic ground squirrels (Urocitellus parryii), wolverines (Gulo gulo), grizzly bears (Ursus arctos), thinhorn sheep (Ovis dalli), and caribou (Rangifer tarandus) [47,48].

2.2. Small Mammal Trapping

Between 8 and 29 July 2005, small mammals were trapped at 27 sites distributed across seven common habitat types in Tombstone, including lowland conifer forest (n = 4 sites), lowland wet shrub (n = 4), sub-alpine shrub (n = 3), wet alpine tundra (n = 5), dry alpine tundra (n = 4), alpine drainage (n = 3), and alpine ridge (n = 4; [39]; Figure 1). These habitat types corresponded with the bioclimatic zones of the Yukon [46]. Specifically, lowland conifer forests and lowland wet shrub sites were located in the Subarctic Woodland bioclimatic zone; subalpine shrub sites were in the Subarctic Subalpine; and the sites in the four alpine habitat types were in the Subarctic Alpine Tundra bioclimatic zone.

At each of the 27 sampling sites, two traplines were established, each consisting of 25 trapping stations spaced ~15 m apart. Traplines were separated by ≥100 m. At each trapping station, a Victor and a Museum Special (Woodstream Corp., Lititz, PA, USA) snap trap were set within 2 m of each other. The traps used targeted smaller rodents and shrews and were previously tested for small mammals in our study region [49]. Snap traps were set in locations that increased the likelihood of capturing small mammals, such as runways or areas adjacent to rock outcrops or downed logs. Traps were baited with a mixture of peanut butter, rolled oats, and milk powder, and checked each morning for three consecutive days. My study design provided for 54 traplines and a potential sampling effort of 8100 trap nights (TN) across the 27 sites surveyed.

Trapping enabled the collection of voucher specimens and positive identification of specimens, which is essential for biodiversity research [4,41,42,49]. Captured specimens were frozen in the field and later identified in the laboratory to species, based on morphological (pelage coloration and body shape) and dental characteristics, using regionally appropriate keys [50,51]. Voucher specimens were archived in the Museum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico (Albuquerque, NM, USA [36]), or the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto, ON, Canada [47]).

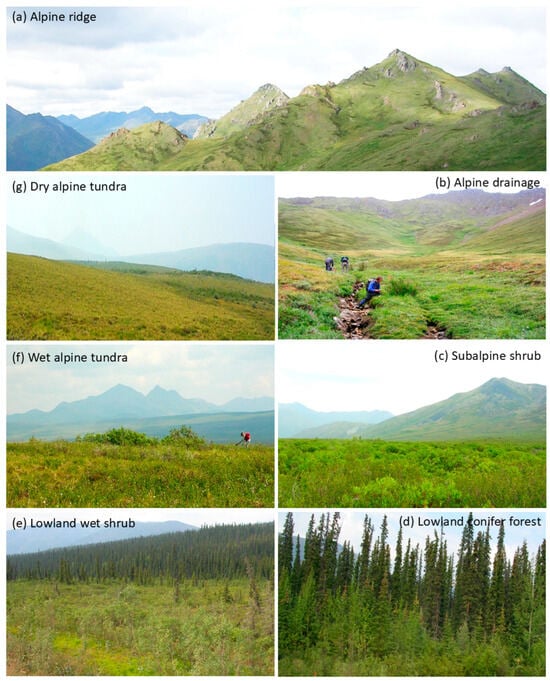

Figure 1.

Photographs of study sites in each of the seven common habitat types sampled for small mammals in Tombstone Territorial Park, Yukon, Canada, during summer 2005. Habitat types included (a) alpine ridge, (b) alpine drainage, (c) subalpine shrub, (d) lowland conifer forest, (e) lowland wet shrub, (f) wet alpine tundra, and (g) dry alpine tundra. Tombstone Territorial Park is located within the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone. Images of people have been modified for privacy and security reasons. Photos by the author.

2.3. Analyses

Sampling among habitat types was uneven (Table 1). To correct this, capture data were standardized using a capture per unit effort (CPUE) as an index of relative abundance. I calculated the number of captures per species per 100 TN for each trapline. The number of effective TN per trapline was adjusted to account for traps that were not available to capture target species using the formula provided by Nelson and Clark [52].

Table 1.

Summary data per habitat type, test statistics, and niche breadth for 12 species of small mammals captured in Tombstone Territorial Park, central Yukon, during July 2005. Values for each species in each habitat are the mean number of captures per 100 trap nights (±SD). Real values are provided in parentheses in each cell. Species richness and estimated species richness (SChao1) by habitat type are also provided. Test statistics are from a Kruskal–Wallis test (H).

Several community-level metrics were calculated, using the equations provided by Krebs [53] and implemented in the software Ecological Methodology (ver. 7). For each habitat type, I calculated species richness, diversity, and evenness. Species richness was simply a tally of the total number of species captured in each habitat type. Chao1 (SChao1) was used to estimate species richness, including the number of species not observed, based on the number of singletons and doubletons observed per habitat type. Diversity was calculated using Brillion’s index (H), and evenness was calculated using Camargo’s index (E′). To examine the niche breadth of individual species, I calculated Levin’s niche breadth measure (B), also using Ecological Methodology (ver. 7).

Normality of abundance and community metric data were assessed with Shapiro–Wilk tests. None of these metrics were normally distributed (p ≤ 0.017), so non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to test for differences in species richness, relative abundance, diversity, and evenness among habitat types. Where H-values indicated significant differences (p < 0.05), pairwise comparisons using Dwass–Steel–Chritchlow–Fligner post hoc tests were performed. I used Mann-Whitney U-tests to compare species richness, relative abundance, diversity, and evenness between the two lowland habitats and the five alpine habitats. Systat (ver. 13) was used for statistical analyses.

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA), an ordination technique, was used to elucidate species and assemblage’s responses to an elevational gradient (continuous) and moisture (categorical: mesic and xeric). Permutation tests (999 permutations) were used to test the significance of the first two canonical correspondence analysis axes (CCA1 and CCA2), which are linear combinations of elevation and moisture from the CCA, with CCA1 being the primary axis that explains the largest variation in the constrained inertia (variation). Permutation tests were also used to assess the effects of moisture and elevation. The CCA and permutation tests were conducted using the package ‘vegan’ (ver. 7.2) in R [54].

Similarity between small mammal assemblages in the different habitat types was evaluated by calculating Sørensen’s (SS) and Renkonen’s (RS) similarity coefficients. Sørensen’s index is based on the presence of species, whereas Renkonen’s index is based on proportions of species in each assemblage. For Sørensen’s index, coefficients closer to 1 indicate very similar assemblages, whereas 0 represents complete dissimilarity [53]. Renkonen’s index measures percent similarity and varies from 0 to 100, with 0 representing incomplete similarity and 100 complete similarity [53]. To further examine similarity among small mammal assemblages, I used Systat (ver. 13) to conduct a hierarchical cluster analysis, using an agglomerative procedure (Ward’s linkage method), to aggregate species assemblages found in the habitat types into clusters based on similarity.

3. Results

3.1. Captures

A total of 266 small mammals, representing 12 species, were captured during 7711 TN of sampling effort (3.42 captures per 100 TN) in Tombstone. Capture rates for each species per habitat type are in Table 1. Arctic ground squirrels disabled many traps at the alpine ridge and dry alpine tundra sites, reducing effective sampling effort in those habitats. Northern red-backed voles (Clethrionomys rutilus) constituted the most captures (47.4%), followed by tundra voles (Alexandromys oeconomus; 17.8%), masked shrews (Sorex cinereus; 17.8%), northern montane shrews (Sorex obscurus; 7.2%), western meadow voles (Microtus drummondii; 3.4%), long-tailed voles (Microtus longicaudus, 1.9%), tundra shrews (Sorex tundrensis, 1.2%), brown lemmings (Lemmus trimucronatus, 1.2%), taiga voles (Microtus xanthognathus, 0.8%) northern bog lemmings (Mictomys borealis, 0.8%), deermice (Peromyscus maniculatus, 0.8%), and collared lemmings (Dicrostonyx nuntakensis, 0.4%).

3.2. Species Assemblages

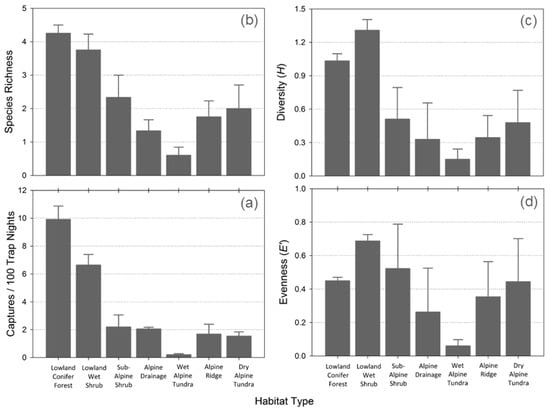

Species assemblages differed significantly among the seven habitat types based on abundance and several community metrics. CPUE varied among the seven habitat types (H6 = 22.226, p = 0.001; Figure 2a); post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that lowland conifer forest and lowland wet shrub sites both had significantly greater CPUE than alpine drainage, wet alpine tundra, and alpine shrub sites (p ≤ 0.007). Test results for species richness across the seven habitat types were similar to those for CPUE, with a significant difference across the seven habitat types (H6 = 17.972, p = 0.006; Figure 2b) and the same differences between habitat types reflected in significant post hoc pairwise comparisons (p ≤ 0.007). Estimated species richness (SChao1) was ≤1 additional species for all habitats except lowland conifer forest, where 4.5 additional species were estimated to be present (Table 1). Brillouin’s index (H) revealed that diversity was statistically different across all habitat types (H = 12.834, p = 0.046). Diversity was highest in lowland habitats and declined with elevation (Figure 2c). Diversity was lowest in wet alpine habitats and similar to species richness, which was greater in lowland wet shrub than in lowland conifer forest. Despite these differences, no post hoc comparisons of diversity among habitat types were significantly different, despite large variation among the means (Figure 2c). Camargo’s index of evenness (E′) followed similar patterns to species richness and diversity; however, the difference across the seven habitat types was not statistically significant (H = 8.833, p = 0.183), likely due to high variability within habitat and small sample sizes (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Mean (±SD) community metrics including (a) species richness, (b) diversity (Simpson’s H), (c) evenness (Camargo’s E′), and (d) captures per 100 trap nights, for small mammal assemblages in seven common habitat types in Tombstone Territorial Park, Yukon, Canada, summer 2005.

More broadly, based on elevation alone, both richness (U = 7.0; p < 0.001) and abundance (CPUE; U = 0.1; p < 0.001) were significantly greater in the two lowland habitat types than in sub-alpine and alpine habitats. There was no statistical difference in diversity (U = 109.0; p = 0.067) or evenness (U = 50.000; p = 0.148) based on elevation. Mesic alpine habitats, including alpine drainage and wet alpine tundra, supported the lowest richness and abundance (Figure 2); however, CPUE, richness, diversity, or evenness were statistically different between xeric or mesic sites (U > 65.5; p > 0.217).

3.3. Habitat Associations

No species were captured across all habitat types (Table 1). Several species were restricted to one or two habitat types, including tundra shrews, deer mice, taiga voles, long-tailed voles, bog lemmings, brown lemmings, and collared lemmings. Only northern red-backed voles, tundra voles, masked shrews, montane shrews, and meadow voles were captured in sufficient numbers for species-level analyses (Table 1). Lowland habitats supported tundra shrews, deer mice, meadow voles, long-tailed voles, and northern bog lemmings, whereas brown lemmings and Ogilvie Mountains collared lemmings were captured exclusively in alpine tundra. Levin’s niche breadth (B) was greatest for tundra voles, northern red-backed voles, and masked shrews, which occurred across the widest range of habitat types, and lowest for species restricted to few habitats (Table 1).

Captures of all four species with sufficient numbers to permit analyses differed significantly between the habitat types (p ≤ 0.021; Table 1). Masked shrews were found predominantly in the two lowland habitat types but were also captured in subalpine shrub and dry alpine tundra habitat types, albeit in low numbers (Table 1). The relative abundance of montane shrews was significantly higher in lowland wet shrub sites than in other sites. Red-backed voles were captured in all habitat types except alpine drainages; however, they were ≥4.6 times more abundant in lowland conifer forest than in the other habitat types (Table 1). Tundra voles were captured significantly more in lowland wet shrub and alpine drainage sites and were not found in xeric sites (Table 1).

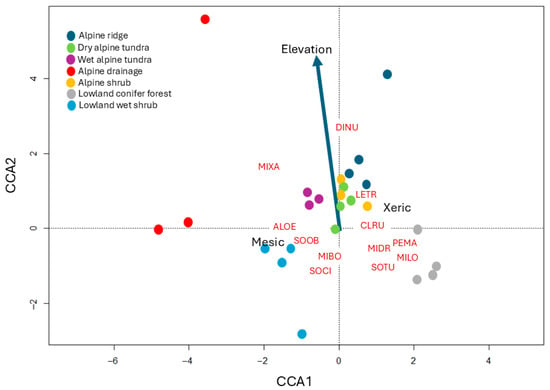

Canonical correspondence analysis indicated that the first two canonical axes (CCA1, CCA2) jointly explained 22.1% of the total constrained inertia in species composition among sites. The first canonical axis accounted for 78.9% of the constrained inertia and was statistically significant (F = 4.91; p = 0.004) based on permutation tests. The second canonical axis (CCA2) explained 21.1% of the inertia and was not statistically significant (F = 1.48; p = 0.109). Permutation tests additionally indicated that moisture was the primary environmental variable structuring community composition (F = 4.85; p = 0.001), and that elevation was not significant (F = 1.38; p = 0.165). Species distributions along the first canonical axis indicated clear differentiation based on distance to moisture centroids (Figure 3), with several taxa showing alignment toward either wet or dry extremes (e.g., collared lemmings and masked shrews). Several other species were positioned near the origin, indicating that they were weakly associated with the two predictors (e.g., red-backed voles and montane shrews).

In general, species assemblages were most similar among the lowland sites and least similar between the lowland conifer forest and the highest-elevation sites, specifically alpine drainage and alpine ridge sites (Table 2). However, Sørensen’s and Renkonen’s indices showed differences in the strength and direction of similarity across several habitat pairings (Table 2). For instance, Sørensen’s index indicated high similarity between lowland conifer forest and lowland wet shrub small mammal assemblages based on presence, whereas Renkonen’s index suggested dissimilarity based on the proportions of each species present in those same assemblages. An additional divergence between the two indices included for the assemblages in lowland conifer forest and alpine ridge, and lowland conifer forest and dry alpine tundra, habitat types (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Biplot of a canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) ordination for 12 species of small mammals captured and 25 sites sampled at Tombstone Territorial Park, Yukon, Canada, using two environmental predictors: elevation (m ASL) and moisture (binary: xeric and mesic). Sites are plotted as points according to the legend, and species are identified by four-letter codes (see Table 1). Two wet alpine tundra sites were not included in the CCA because they had no captures of small mammals. The first axis (CCA1) explained 78.9% of the constrained variation among sites, and the second axis (CCA2) explained 21.1%. Species and sites near the origin indicate a comparatively weak association with the two environmental predictors. Five species were rare (<5 captures each, including: DINU, LETR, MIBO, MIXA, and PEMA), so their placement by ordination should be considered exploratory.

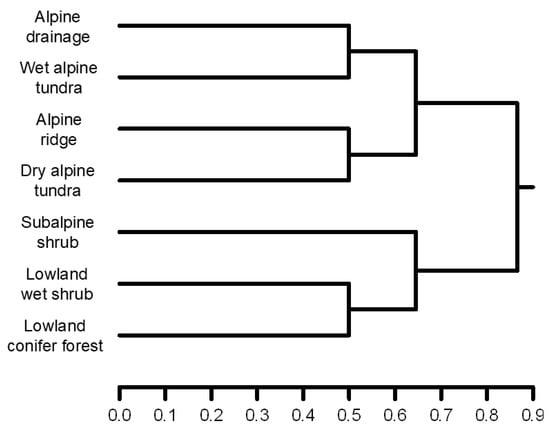

A hierarchical cluster analysis of a species presence matrix, using Ward’s linkage method, separated lowland and subalpine shrub habitats from alpine habitat sites, which were the least similar in their species assemblages (Figure 4), with lowland wet shrub and lowland conifer being close together. Within alpine habitats, small mammal assemblages were further separated based on moisture (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Matrix of similarity coefficients for small mammal assemblages in seven habitat types in Tombstone Territorial Park, Yukon, Canada. Values above shaded cells are from Renkonen’s index, and those below the shaded cells are from Sørensen’s index. Values of 0 indicate complete dissimilarity, while those of 1 (Sørensen) or 100 (Renkonen) represent complete similarity [54].

Table 2.

Matrix of similarity coefficients for small mammal assemblages in seven habitat types in Tombstone Territorial Park, Yukon, Canada. Values above shaded cells are from Renkonen’s index, and those below the shaded cells are from Sørensen’s index. Values of 0 indicate complete dissimilarity, while those of 1 (Sørensen) or 100 (Renkonen) represent complete similarity [54].

| Habitat Type | Lowland Conifer Forest | Lowland Wet Shrub | Subalpine Shrub | Alpine Ridge | Wet Alpine Tundra | Dry Alpine Tundra | Alpine Drainage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowland conifer forest | 18 | 84 | 73 | 33 | 72 | 6 | |

| Lowland wet shrub | 0.80 | 16 | 20 | 39 | 30 | 43 | |

| Subalpine shrub | 0.62 | 0.67 | 72 | 39 | 78 | 6 | |

| Alpine ridge | 0.18 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 33 | 72 | 6 | |

| Wet alpine tundra | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.40 | 33 | 67 | |

| Dry alpine tundra | 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.33 | 6 | |

| Alpine drainage | 0.18 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.17 |

Figure 4.

Results of a hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s linkage to group small mammal assemblages in seven habitat types in Tombstone Territorial Park based on their similarity.

4. Discussion

4.1. Species Diversity

While the diversity and distribution of small mammals in the Yukon are relatively well known [55], assemblages and habitat associations in the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone are not. My study provides one of the first approximations of small mammal diversity, community composition, and habitat associations in Tombstone Territorial Park, or elsewhere in the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone. To my knowledge, no similar systematic sampling has occurred in the ecozone since my sampling in 2005, nor has this work been replicated in Tombstone. Most records of small mammals in the region come from opportunistic trapping for museum collections rather than standardized sampling across habitat types [34,36]. Within this context, a key finding of this study was that the small mammal fauna of Tombstone was relatively diverse, with three shrew species and nine small rodent species documented. Although likely underrepresented in my sampling, species richness was consistent with expectations for a subarctic region positioned between boreal and arctic ecozones. Estimated species richness was comparable to that reported from the Boreal Cordillera Ecozone ~400 km to the south [32] and exceeded that documented at the Low Arctic Ecozone ~460 km farther north [33], suggesting a transitional fauna shaped by both boreal and arctic influences.

Estimated species richness was greater than observed species richness for all habitats sampled, particularly for lowland conifer forests, with the exception of alpine ridges. Notably, several species previously recorded in or near Tombstone were not captured during this study, including the western pygmy shrew (Sorex eximius; [56]), Holarctic least shrew (Sorex minutissimus; [35]), western water shrew (Sorex navigator; [57]), singing vole (Microtus miurus; [34]), and, potentially, the meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius). Reasons for these absences likely reflected my selection of trap type, habitat-specific sampling gaps, and natural population cycles rather than true absence. For instance, extremely small shrew species, including the western pygmy shrew and the Holarctic least shrew, are poorly sampled with snap traps and are more effectively detected with pitfall trapping [57,58,59]. Future trapping campaigns could incorporate pitfall trapping to more effectively sample smaller shrews. The absence of western water shrews likely reflects limited sampling in riparian habitats, where this semi-aquatic species is typically restricted [60,61]. The failure to capture singing voles, despite prior records in the park, may result from their low densities, patchy distribution, and asynchronous population cycles, combined with the single-year duration and limited spatial replication [62,63]. Failure to capture meadow jumping mice in Tombstone, which is at the northern edge of their range, may be a function of all of the reasons above [64,65,66], or they are simply restricted to boreal ecozones found further south.

The capture of an Ogilvie Mountains collared lemming and deer mice was notable. Collared lemmings have a patchy, highly localized distribution, which appears confined to high-altitude, alpine habitats within the park [46]. The capture of deer mice in Tombstone represents a modest—but noteworthy—northward range extension [34,55]. Although deer mice are often dominant members of boreal small mammal communities [11,14,32], evidence from other systems suggests limited niche overlap with microtine rodents due to temporal and dietary partitioning [67,68,69]. Regardless, monitoring will be required to determine whether deer mice have increased in abundance and distribution over the elapsed time since my sampling, and whether concomitant shifts in small mammal assemblages have or will occur if deer mouse populations in Tombstone increase.

4.2. Species Assemblages

Patterns in species richness, abundance, diversity, and evenness indicated that small mammal assemblages in Tombstone are structured by moisture and elevation gradients. Richer and more abundant assemblages in lowland habitats were more diverse and less even, likely reflecting greater primary productivity, deeper organic soils, higher vegetation complexity, and more moderate temperatures. Vegetative cover in boreal forest and shrub communities likely buffers small mammals from temperature extremes in more open alpine habitats and provides concealment from avian predators. Moreover, snow cover in forested and shrub communities was likely more stable and less prone to being wind blown, providing an additional buffer against low winter temperatures. Lowland habitats likely supported a wider range of ecological niches given greater heterogeneity in microclimates and more abundant and diverse food availability [11,32] than subalpine or alpine habitats. In contrast, assemblage complexity declined with increasing elevation, consistent with patterns observed in other northern mountain systems, where colder temperatures, shorter growing seasons, and reduced habitat heterogeneity and food availability constrain the abundance and richness of small mammal assemblages [23,26,28].

Differences among community metrics highlight contrasting aspects of structuring assemblages across habitats. Alpine and mesic habitats supported few species at low abundance, resulting in low diversity but relatively high evenness, a pattern characteristic of environmentally harsh systems where only a small number of species can persist [60,70,71]. In contrast, lowland conifer forest supported high species richness and abundance but lower evenness, reflecting numerical dominance by a subset of species. These dominance patterns are typical of more productive boreal systems, where red-backed voles and deer mice typically account for a large proportion of individuals [32].

Variation in niche breadth further illustrates species-specific responses to habitat heterogeneity. Species such as tundra voles, northern red-backed voles, and masked shrews occurred across multiple habitat types, indicating relatively broad ecological tolerances and flexibility in habitat use [32,71,72,73,74,75]. In contrast, species with narrow niche breadths were restricted to particular environments, including alpine specialists such as Ogilvie Mountains collared lemmings and brown lemmings, whose distributions closely aligned with cold, open tundra [21,63,76,77]. The absence of any species across all seven habitat types sampled and the separation between lowland and alpine assemblages revealed through a cluster analysis indicated a moderate–strong effect of habitat as a primary driver structuring assemblages.

4.3. Habitat Associations and Assemblage Similarity

Habitat associations and assemblage similarity analyses further emphasized the importance of environmental gradients in structuring small mammal communities in Tombstone. Assemblages differed markedly among lowland, subalpine, and alpine habitats, with species richness and relative abundance declining with elevation and assemblage composition shifting from diverse communities of shrews and voles in lowland environments to depauperate, specialized assemblages in alpine tundra. Several species were restricted to lowland habitats, including meadow voles, long-tailed voles, and northern bog lemmings, highlighting the importance of boreal forests and shrub communities for maintaining regional small mammal diversity.

Assemblages also varied along a mesic–xeric gradient, with a CCA indicating that moisture was the primary environmental predictor structuring assemblages in Tombstone. The contrast between the results from the CCA and ANOVAs indicated that moisture did not affect community parameters; rather, it was associated with species turnover—the replacement of more xerophylous with more hygrophilous species. However, several species and assemblages (sites) were near the origin, indicating weak association with the two axes. Overall, however, wet alpine tundra and alpine drainage sites supported fewer species and lower relative abundance than drier conifer forest, alpine ridge, and tundra habitats. Poor drainage, saturated soils, and prolonged snow cover in mesic alpine environments may limit burrowing opportunities and reduce overwinter survival for some species [62,70], whereas drier habitats may provide more stable subnivean conditions and forage availability during the brief growing season.

Together, these patterns demonstrate that elevation, moisture, and vegetation structure interact to shape distinct small mammal assemblages across the landscape. Similar patterns of community turnover along gradients have been reported from other boreal regions, suggesting that relatively small changes in vegetation structure, moisture, and snow conditions may result in pronounced shifts in small mammal assemblages [11,78]. By documenting consistent habitat associations and assemblage turnover across environmental gradients, my data contribute to a broader understanding of how small mammal communities are organized in northern mountain ecosystems.

5. Conclusions

My study provides the first quantitative assessment of subarctic small mammal assemblages and habitat associations in the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone, a vast ecological region where small mammals have not been well studied, and monitoring assemblages has been identified as a priority but remains non-existent [36,37]. As such, it provides an important historical baseline for a region where ecological data remain sparse [25,37]. That said, the spatial scope of my sampling was limited, and further sampling at other sites within the Taiga Cordillera Ecozone would increase resolution and allow for generalization. My key finding was that small mammal communities in Tombstone Territorial Park were structured by elevation, moisture, and habitat type, with diverse and comparatively abundant assemblages concentrated in lowland boreal habitats and increasingly depauperate, specialized assemblages occurring in alpine environments. Species exhibited marked differences in niche breadth, ranging from habitat generalists occupying multiple vegetation types to specialists restricted to cold, open alpine tundra. These patterns suggest that ongoing climate-driven changes—such as warming temperatures, altered snow regimes, shrubification, and permafrost loss—are likely to restructure subarctic small mammal assemblages by facilitating upslope and northward range expansions of lowland-associated species while potentially reducing habitat availability for tundra and alpine specialists. Such shifts may have cascading effects on predator–prey dynamics, food webs, and ecosystem processes [29,30]. By documenting patterns of diversity, habitat association, and assemblage similarity, this study provides a historic reference against which recent and future changes can be evaluated, highlighting the value of protected areas like Tombstone for long-term monitoring in a rapidly warming subarctic.

Funding

This work was funded by the Government of Yukon.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Trapping was conducted in compliance with ethical and professional standards as per the guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists [79], and under a park permit. Institutional review was provided by the Government of Yukon (521-303020-170-01) and approved under the Yukon Wildlife Act (permits #0037 and #8121; 19 May 2005).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to Daniel Clyde. I thank B. Bell, B. Cadsand, M. Clyde, M. Kienzler, P. Kukka, D. Nagorsen, S. Nielsen, K. O’Donovan, S. Powell, T. Pretzlaw, L. Randall, K. Russell, and M. Smith for assistance in the field or lab. H. Miller ran the CCA in R. I thank D.W. Nagorsen and B.G. Slough for helpful discussions. J. Frisch, C. Hunt, T. Pretzlaw, and E. Val provided logistical support. This paper was improved by the comments of two anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Avenant, N.L. Small mammal community characteristics as indicators of ecological disturbance in the Willem Pretorius Nature Reserve, Free State, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 2000, 30, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Avenant, N.L. The potential utility of rodents and other small mammals as indicators of ecosystem integrity of South African grasslands. Wildl. Res. 2011, 38, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venance, J. Small mammal communities in the Mikumi National Park, Tanzania. Hystrix 2009, 20, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Negesse, M.; Yazezew, D.; Degefe, G.; Getachew, G. Species composition, relative abundance and distribution of rodents in Wof-Washa Natural State Forest, Ethiopia. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 39, e02283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, I.; Freixas, L.; Arrizabalaga, A.; Díaz, M. The efficiency of two widely used commercial live-traps. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 66, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, I.; Raspall, A.; Arrizabalaga, A.; Díaz, M. SEMICE: An unbiased and powerful monitoring protocol. Mamm. Biol. 2018, 88, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balčiauskas, L.; Balčiauskienė, L.; Stirkė, V. Mow the grass at the mouse’s peril: Diversity of small mammals in commercial fruit farms. Animals 2019, 9, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balčiauskas, L.; Pilāts, V.; Timm, U. Mammal fauna changes in Baltic countries during last three decades. Diversity 2025, 17, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirichella, R.; Ricci, E.; Armanini, M.; Gobbi, M.; Mustoni, A.; Apollonio, M. Small mammals in a mountain ecosystem: The effect of topographic, micrometeorological, and biological correlates on their community structure. Community Ecol. 2022, 23, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M. Abundance, diversity, and community structure of small mammals in forest fragments in Prince Edward Island National Park, Canada. Can. J. Zool. 2001, 79, 2063–2071. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.; Venier, L. Small mammals as bioindicators of sustainable boreal forest management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 208, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, C.; Patton, J.L.; Conroy, C.J.; Parra, J.L.; White, G.C.; Beissinger, S.R. Impact of a century of climate change on small mammal communities in Yosemite National Park, USA. Science 2008, 322, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, P.; Lundrigan, B.L.; Hoffman, S.M.G.; Haraminac, A.P.; Seto, S.H. Climate-induced changes in the small mammal communities of the Northern Great Lakes region. Glob. Change Biol. 2009, 15, 1434–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.S. Comparative efficacy of Longworth, Sherman, and Ugglan live-traps for capturing small mammals in the Nearctic boreal forest. Mammal Res. 2016, 61, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, C.J.; Boutin, S.; Boonstra, R.; Murray, D.L.; Jung, T.S.; O’Donoghue, M.; Gilbert, B.S.; Kukka, P.M.; Taylor, S.D.; Morgan, T.; et al. Long-term monitoring in the boreal forest reveals high spatio-temporal variability among primary ecosystem constituents. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1187222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, C.J.; Kenney, A.J.; Gilbert, B.S.; Boonstra, R. Long-term monitoring of cycles in Clethrionomys rutilus in the Yukon boreal forest. Integr. Zool. 2024, 19, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, A.L.; Gentile, R.; Bonvicino, C.R.; Crisostomo, C.F.; Silveira, M.; D’Andrea, P.S. Environmental determinants of the taxonomic and functional alpha and beta diversity of small mammals in forest fragments in southwestern Amazonia, Brazil. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 58, e03445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunde, D.P.; Son, N.T.; Musser, G.G. A survey of small mammals from Huu Lien Nature Reserve, Lang Son Province, Vietnam. Mammal Study 2007, 32, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, R.; Krebs, C.J. Population dynamics of red-backed voles (Myodes) in North America. Oecologia 2012, 168, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, R.; Boutin, S.; Jung, T.S.; Krebs, C.J.; Taylor, S. The impact of rewilding, species introductions and climate change on the structure and function of the Yukon boreal forest ecosystem. Integr. Zool. 2018, 13, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs, C.J. Lemming population fluctuations around the Arctic. Proc. R. Soc. B 2024, 291, 20240399. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körner, C. Mountain biodiversity, its causes and function. Ambio 2004, 33, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C. The use of altitude in ecological research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, G.; Hanley, K. The state of mountain research in Canada. J. Mt. Sci. 2022, 19, 3013–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.H. Mammals on mountaintops: Nonequilibrium insular biogeography. Am. Nat. 1971, 105, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickart, E.A. Elevational diversity gradients, biogeography and the structure of montane mammal communities. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2001, 10, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, C.M. Elevational gradients in diversity of small mammals. Ecology 2005, 86, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francl, K.E.; Hayhoe, K.; Saunders, M.; Maurer, E.P. Ecosystem adaptation to climate change: Small mammal migration pathways in the Great Lakes states. J. Great Lakes Res. 2010, 36, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, C.J.; Boonstra, R.; Gilbert, B.S.; Kenney, A.J.; Boutin, S. Impact of climate change on the small mammal community of the Yukon boreal forest. Integr. Zool. 2019, 14, 528–541. [Google Scholar]

- Droghini, A.; Christie, K.S.; Kelty, R.R.; Schuette, P.A.; Gotthardt, T. Conservation status, threats, and information needs of small mammals in Alaska. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2022, 4, e12671. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, C.J.; Wingate, I. Small mammal communities of the Kluane region, Yukon Territory. Can. Field-Nat. 1976, 90, 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Martell, A.M.; Pearson, A.M. The small mammals of the Mackenzie Delta region, Northwest Territories, Canada. Arctic 1978, 31, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngman, P.M. Mammals of the Yukon Territory; National Museum of Natural Sciences: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J.A.; McLean, B.S.; Jackson, D.J.; Colella, J.P.; Greiman, S.E.; Tkach, V.V.; Jung, T.S.; Dunnum, J.L. First record of the Holarctic least shrew (Sorex minutissimus) and associated helminths from Canada: New light on northern Pleistocene refugia. Can. J. Zool. 2016, 94, 367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J.A.; Galbreath, K.E.; Bell, K.C.; Campbell, M.L.; Carriere, S.; Colella, J.P.; Dawson, N.G.; Dunnum, J.L.; Eckerlin, R.P.; Fedorov, V.; et al. The Beringian Coevolution Project: Holistic collections of mammals and associated parasites reveal novel perspectives on evolutionary and environmental change in the North. Arctic Sci. 2017, 3, 585–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESTR Secretariat. Taiga Cordillera Ecozone+ Evidence for Key Findings Summary: Canadian Biodiversity—Ecosystem Status and Trends 2010; Canadian Councils of Resource Ministers: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ecological Stratification Working Group. A National Ecological Framework for Canada; Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and Environment Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, C.E.; Smith, C.A.S. Vegetation, Terrain and Natural Features in the Tombstone Area, Yukon Territory; Department of Renewable Resources: Whitehorse, YT, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Frappier, R.; Lacelle, D.; Fraser, R.H. Landscape changes in the Tombstone Territorial Park region (central Yukon, Canada) from multilevel remote sensing analysis. Arct. Sci. 2023, 9, 838–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagorsen, D.W.; Peterson, R.L. Distribution, abundance and species diversity of small mammals in Quetico Provincial Park, Ontario. Nat. Can. 1981, 108, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Paitschniak-Arts, M.; Gibson, J. Distribution and abundance of small mammals in Lake Superior Provincial Park, Ontario. Can. Field Nat. 1989, 103, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Simelane, F.N.; Mahlaba, T.A.M.; Shapiro, J.T.; MacFadyen, D.; Monadjem, A. Habitat associations of small mammals in the foothills in the Drakensberg Mountains, South Africa. Mammalia 2018, 82, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran, A.E.; Baillie, S.R.; Buckland, S.T.; Dick, J.M.; Elston, D.A.; Scott, E.M.; Smith, R.I.; Somerfield, P.J.; Watt, A.D. Long-term datasets in biodiversity research and monitoring. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, K.A.; Reid, D.G.; Brown, C.D. Patterns of vegetation change in Yukon. Environ. Rev. 2022, 30, 380–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment Yukon. Bioclimate Zones and Subzones; Government of Yukon: Whitehorse, YT, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, T.S.; Slough, B.G.; Nagorsen, D.W.; Kukka, P.M. New Records of the Ogilvie Mountains collared lemming (Dicrostonyx nunatakensis) in central Yukon. Can. Field Nat. 2014, 128, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannings, S.G.; Jung, T.S.; Skevington, J.H.; Duclos, I.; Dar, S. A reconnaissance survey for collared pika (Ochotona collaris) in northern Yukon. Can. Field Nat. 2019, 133, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.S.; Pretzlaw, T.D. Relative efficiency of two models of snap traps for sampling boreal small mammals. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2022, 46, e1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagorsen, D.W. An Identification Manual to the Small Mammals of British Columbia; Royal British Columbia Museum: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, S.O. The Small Mammals of Alaska: A Field Handbook of the Shrews and Small Rodents; University of Alaska Museum of the North: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, L.; Clark, F.W. Correction for sprung traps in catch/effort calculations of trapping results. J. Mammal. 1973, 54, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, C.J. Ecological Methodology, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Wagner, H.; et al. Vegan, version 2.7; Community Ecology Package. 2013. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Slough, B.G.; Jung, T.S. Diversity and distribution of the terrestrial mammals of the Yukon. Can. Field Nat. 2007, 121, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, T.S.; Pretzlaw, T.D.; Nagorsen, D.W. Northern range extension of the pygmy shrew, Sorex hoyi, in the Yukon Territory. Can. Field Nat. 2007, 121, 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrell, G.H. A northern record of the water shrew, Sorex palustris, from the Klondike River, Yukon Territory. Can. Field Nat. 1986, 100, 391. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, K.N.; Peirce, J.M. Range extensions for the Alaska tiny shrew and pygmy shrew in southwestern Alaska. Northwest. Nat. 2000, 81, 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, T.S.; Slough, B.G. Relative use of xeric boreal habitats by shrews (Sorex spp.). Mammalia 2022, 86, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, A.W.; Pettus, D. Habitat preferences of five sympatric species of long-tailed shrews. Ecology 1966, 47, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, R.E.; Dubois, J.E.; Copeland, H.W.R. Habitat, abundance and distribution of six species of shrews in Manitoba. J. Mammal. 1979, 60, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, R.J. Ecological distributions of small mammals in the De Long Mountains of northwestern Alaska. Arctic 1984, 37, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, C.J.; Wingate, I. Population fluctuations in the small mammals of the Kluane Region, Yukon Territory. Can. Field Nat. 1985, 99, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass, R.J.; McNaughton, A.E.L. A recent record of the meadow jumping mouse, Zapus hudsonius, in the Northwest Territories. Can. Field Nat. 1977, 91, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, R.; Hoyle, J.A. Rarity and coexistence of a small hibernator, Zapus hudsonius, with fluctuating populations of Microtus pennsylvanicus in the grasslands of southern Ontario. J. Anim. Ecol. 1986, 55, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.S.; Powell, T. Spatial distribution of meadow jumping mice (Zapus hudsonius) in logged boreal forest of northwestern Canada. Mamm. Biol. 2011, 76, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, C.; Krebs, C.J. Habitat use and abundance of deer mice: Interactions with meadow voles and red-backed voles. Can. J. Zool. 1985, 63, 1870–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, S.B.; Cichowski, D.B.; Talerico, D.; Krebs, C.J. Summer activity patterns of three rodents in the southwestern Yukon. Arctic 1986, 39, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.O.; Dueser, R.D. Noncompetitive coexistence between Peromyscus species and Clethrionomys gapperi. Can. Field-Nat. 1986, 100, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, W.O. Observations on the bioclimate of some taiga mammals. Arctic 1957, 10, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Batzli, G.O.; Lesieutre, C. Community organization of arvicoline rodents in northern Alaska. Oikos 1995, 72, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, P. Population ecology of two sympatric species of sub-arctic microtine rodents. Ecol. Monogr. 1976, 46, 166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Martell, A.M.; Pearson, A.M. Comparative demography of Clethrionomys rutilus in taiga and tundra in the low Arctic. Can. J. Zool. 1979, 57, 2106–2120. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.D. Dynamics of colonization and abundance in central Alaskan populations of the northern red-backed vole. J. Mammal. 1982, 63, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzli, G.O.; Henttonen, H. Demography and resource use by microtine rodents near Toolik Lake, Alaska, USA. Arct. Alp. Res. 1990, 22, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, C.J.; Boonstra, R.; Kenney, A.J. Population dynamics of the collared lemming and the tundra vole at Pearce Point, Northwest Territories, Canada. Oecologia 1995, 103, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, C.J.; Reid, D.; Kenney, A.J.; Gilbert, S. Fluctuations in lemming populations in north Yukon, Canada, 2007–2010. Can. J. Zool. 2011, 89, 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, D.W. Coexistence of specialist and generalist rodents via habitat selection. Ecology 1996, 77, 2352–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animal Care and Use Committee. Guidelines for the capture, handling, and care of mammals as approved by the American Society of Mammalogists. J. Mammal. 1998, 79, 1416–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.