Abstract

Sago pondweed (Stuckenia pectinata (L.) Börner) is a genetically and ecologically diverse submerged macrophyte, notable for its versatile reproductive characteristics, with a broad global distribution, excluding only the Arctic and Antarctic regions. This cosmopolitan species remains underexplored genetically in Lithuania compared to some other European regions. The aim of this study was to investigate the state and distribution of genetic diversity across Lithuanian river populations. We analyzed genetic variation in ten riverine populations using both simple sequence repeats (SSRs) and intersimple sequence repeats (ISSR). Genetic distances between genotypes and populations, as revealed by SSR markers, correlated with those determined using ISSR markers, confirming consistency across the two marker systems. STRUCTURE analysis revealed the presence of two distinct genotype pools. Our study demonstrated that the majority of genetic variation resides within populations, with an FST value of 0.212 (SSR) and a ΦPT value of 0.352 (ISSR). These findings suggest high genetic differentiation among populations. The absence of a relationship between genetic diversity and hydrochemical or hydromorphological parameters at plant collection sites suggests that the population structure of this species is shaped primarily by evolutionary and/or demographic mechanisms, rather than by local environmental hydrochemical conditions. Overall, this study revealed high within-population genetic diversity and underlying genetic structure in S. pectinata populations across Lithuanian rivers.

1. Introduction

Small and medium-sized rivers constitute a significant portion of Europe’s waterways, and their health significantly affects the ecosystems within or near the river. International agreements such as the Ramsar Convention, Natura 2000, and the EC Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) [1] have been established to safeguard the most valuable water ecosystems [2]. For the sustainable development of these resources, it is essential to have comprehensive knowledge about them. The state of the riverine ecosystem is closely associated with the state of the freshwater plant (macrophyte) species inhabiting it. Macrophytes are the fundamental components of stream and riverine ecosystems, which experience multiple anthropogenic stressors. They provide food and shelter for a variety of animals. Macrophytes also significantly impact water quality. They stabilize sediments, participate in the cycling and storage of nutrients, enrich water with oxygen, absorb excess nitrogen and phosphorus, and release substances that inhibit water blooms [3,4,5,6,7]. However, in certain ecological situations, macrophytes (especially invasive ones) can overgrow water bodies, reduce current velocity, and degrade water quality [8,9].

Among submerged keystone macrophytes, Sago pondweed Stuckenia pectinata (L.) Börner is an important and ecologically and genetically diverse species distributed across all geographic zones except the Arctic and Antarctic regions [10,11,12,13,14]. S. pectinata engages in a variety of reproductive strategies. This species reproduces sexually by seeds and asexually by tubers, rhizomes, and stem (shoot) fragments [3,5,13]. Sago pondweed demonstrates high morphological and ecological plasticity, enabling it to thrive in various habitats, including various freshwater sources and brackish coastal marine sites, as well as in waters with varying trophic conditions [10]. This species is widely used as a model organism in ecological research [3,7,8,10,11,14]. For example, Janauer [11] reported that eutrophication alters certain metabolic parameters of S. pectinata. Nolet et al. [15] analyzed the impact of Tundra swans foraging on sago pondweed tubers. The authors reported a positive relationship between giving-up density and water depth [15]. S. pectinata is considered an indicator species for eutrophicated waters, but it also grows in waters with low total phosphorus levels, indicating that it may not be a reliable indicator of eutrophic conditions [16]. In the first studies of genetic diversity, isozyme markers were analyzed, and the results indicated high population differentiation, low genetic polymorphism, and a significant impact of vegetative reproduction on population structure [17,18]. In this work [17], some genetic differentiation between brackish water and freshwater genotypes was observed. For later studies, the advancement of molecular markers enabled a more comprehensive analysis of population genetic diversity. For example, using DNA markers, Mader et al. [19] reported relatively high clonal diversity and emphasized the importance of sexual reproduction in the genetic variation in S. pectinata. Hangelbroek et al. [20] used random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers and reported a surprisingly high number of genets in the S. pectinata population from Lake Lauwersmeer in the Netherlands. The high degree of clonal diversity indicated that sexual reproduction is significant in sago pondweed populations. The genetic parameters of the population are affected by various biotic and abiotic factors. The authors indicated that factors such as water depth, silt content, and tuber predation by Bewick’s swans reduce clonal diversity. In their 2002 study, King et al. [21] analyzed the polymorphisms of ISSR loci in populations of S. pectinata around the Baltic Sea. The authors reported that lower levels of population differentiation on the southeastern Swedish coast can be associated with significant waterfowl migration through this area.

Nies and Reusch [22], using SSR markers, conducted a study in Germany to examine how habitat configuration and environmental conditions affect the population structure of S. pectinata. They reported genetic divergence between populations from different habitats, specifically the Baltic Sea coast and inland lakes. The authors also concluded that the greater connectivity in Baltic Sea populations than in lake populations was the primary reason for the more significant genetic differentiation observed in lake populations. Triest and Fénart [23] reported that the diversity patterns of S. pectinata differ at Woluwe River (Belgium) sites and in the ponds of the river catchment and may be impacted by their habitat being subject to stress. The clonal diversity of S. pectinata was greater at the pond sites. In addition, the authors reported moderate genetic differentiation among the studied populations. Most identified clones were site specific, except for some proximate sites that shared a few clones. The impact of habitat type on genetic diversity was also evaluated by Han et al. [24] using amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers. Genetic differences were detected between S. pectinata populations from two lakes with different trophic levels (eutrophic and oligotrophic) in China. Age and local adaptations to varying environmental conditions, such as salinity, were also hypothesized as factors contributing to the divergence of S. pectinata s.l. in the lakes of southern Siberia, Russia, by Volkova et al. [25], on the basis of variability in the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer region (ITS). SSR and ISSR loci studies revealed high genetic diversity and significant differentiation among S. pectinata populations in Iran, with distinct clustering based on geographic region [26,27]. In this study, river, wetland, and lake populations were surveyed. The authors reported that the genetic makeup of certain populations is influenced by geographical barriers such as mountain ranges and desert zones. This makes them significant independent evolutionary lineages and important for conservation efforts [26]. Fehrer et al. [28] investigated the taxonomy of the genus Stuckenia by sequencing nuclear ribosomal regions as well as chloroplast intergenic spacers. Their study revealed two main lineages within this genus. The authors reported that both interspecific hybridization and intraspecific hybridization are common, with the resulting hybrids displaying varying levels of fertility. Additionally, environmentally induced variation must also be considered during taxonomic studies. Two major genotypes of S. pectinata were identified in the study. Triest et al. [29] investigated the genetic structure of S. pectinata using samples from Europe and Africa. By employing nuclear SSR markers, complete chloroplast genome sequences, and rRNA sequences, the researchers confirmed the existence of two main gene pools: genotype 1a, which includes European populations, and genotype 1b, which consists of populations from the African Rift lakes. Further analysis revealed additional subdivisions within lineage 1a, distinguishing two potential gene pools associated with different habitats: freshwater and brackish water. These findings suggest that contemporary populations reflect ancient genetic differentiation, highlighting the importance of considering genetic identity in ecological and reproductive studies of this widespread species.

In previous studies, S. pectinata populations from various water sources, including seashores, lakes, ponds, river stretches, and wetlands, have been investigated. The focus of our study was river populations whose disturbance levels and water physicochemical characteristics varied. The natural river network in Lithuania has undergone significant changes, largely because of economic activity in the 20th century [30]. Rivers were deepened, dredged, straightened, regulated, and dammed [31]. The reclamation and drainage of wetlands between 1950 and 1990 had the most significant impact. Only approximately 17% of the riverbeds remain in their natural state. Anthropogenic modifications of rivers significantly affect the health and sustainability of river ecosystems, particularly by impacting plant components. For instance, the construction of dams and water abstraction reduce water flow and alter the hydrological regime, leading to a reduction in the overall extent of river ecosystems [32] and harming riverine communities [33,34]. These anthropogenic river alterations may also lead to genetic fragmentation and genetic drift. Additionally, obstacles created in the riverbed and changes in the flow regime cause variations in the frequency of macrophytes [35], hinder hydrochory dispersal [36], and can affect seedling survival [37]. River regulation also influences the genetic structure and dispersal patterns of plant populations [38] and increases the invasion of alien species [39,40,41].

Given the extensive anthropogenic alterations of Lithuanian rivers and the limited genetic research on S. pectinata in this region, we aimed to evaluate how genetic variation is distributed across riverine populations. We hypothesized that the genetic diversity and structure of S. pectinata are shaped primarily by evolutionary and demographic mechanisms, such as genetic drift, clonality, and limited dispersal, rather than by local hydrochemical or hydromorphological factors. To test this hypothesis, we: (1) assessed the level and distribution of genetic diversity using SSR and ISSR markers; (2) compared the congruence of both marker systems; (3) analyzed genetic differentiation and structure among populations using AMOVA, PCoA, and STRUCTURE; (4) evaluated correlations between genetic diversity parameters and hydrochemical or hydromorphological indices; and (5) interpreted the results in terms of ecological adaptation for Lithuanian freshwater systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

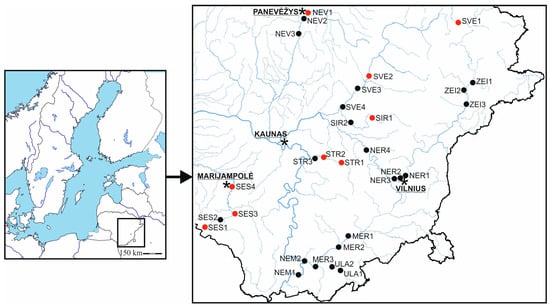

Samples of plant material were collected between 2016 and 2017 from the rivers, mainly in south and east Lithuania. The rivers varied in size, basin area, discharge, and extent of riverbed modification (see Figure 1 and Table S1). The sampling site codes for the plant collection locations shown in Figure 1 are detailed in Table S1.

Figure 1.

Map of 30 sampling sites for Stuckenia pectinata located in ten different rivers in Lithuania. Sites are classified according to river modification status: red dots indicate sites located in modified river stretches, whereas black dots indicate sites in natural river stretches. The star indicates the location of the nearest city.

ISSR polymorphisms were analyzed in 10 populations, whereas SSR analysis was conducted on a smaller sample size in 9 populations from different rivers. There were a total of 30 sampling sites, with 2 to 4 sites per river. The samples were collected at least 5 m apart from each other. The plant material was placed in a cooler with ice for transportation to the laboratory. Once present, the specimens were re-evaluated taxonomically following the guidelines of Wiegleb and Kaplan [42].

2.2. DNA Analysis

DNA was isolated from 100 mg of fresh leaves from 381 S. pectinata plants using a modified CTAB method [43]. For SSR analysis, 15–24 plants from each population and 7–8 plants from each site were used, for a total of 151 plants. Nine microsatellite loci, Potpect24, Potpect26, Potpect28, Potpect32, Potpect34, Potpect37, Potpect39, Potpect40, and Potpect42, previously identified by Nies and Reusch [44], were analyzed. These loci exhibited variation among Lithuanian populations and were analyzed in 151 individuals from nine populations. PCR was conducted using a Mastercycler ep gradient (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) according to the protocol outlined by Nies and Reusch [22]. This involved an initial denaturation step of 12 min at 94 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 4 s at 72 °C, with a final elongation step of 2 min at 72 °C. Each locus was amplified in separate reactions. The reaction consisted of a 10 μL mixture containing 1 μL of 10 × DreamTaq buffer, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 150 μM dNTP mix, 0.2 μM of each primer (with the forward primer labeled with 6-Fam, Hex or Cy3), 2.0 U of DreamTaq DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics, Vilnius, Lithuania), and 20 ng of DNA. Genotyping was performed using an Applied Biosystems Genetic Analyzer 3500. Peaks were scored using GeneMapper software version 6 (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), with a custom size standard GeneScan™ 600 LIZ™ (Applied Biosystems, Inc., USA) as a reference for fragment sizes. To ensure the reproducibility of DNA amplification, twenty samples were run in duplicate for all the loci.

For ISSR analysis, 20 oligonucleotide primers were tested across 24 S. pectinata genotypes from different sites, and eight ISSR primers that generated clear, reproducible DNA bands were selected. For the initial phase, the same 151 plants as in the SSR assay were analyzed. On the basis the obtained results, the study was expanded to include 351 individuals from 10 populations, which were analyzed using the selected primers ISSR I-32, ISSR I-34, ISSR I-50a, ISSR A, ISSR D, ISSR O, UBC 810, and UBC 890. PCRs were conducted in a total volume of 10 μL as described previously [45]. The reaction mixture included 10× DreamTaq buffer, 200 μM dNTPs, 300 μM MgCl2, 20 ng of genomic DNA, 5 μM primer, and 0.5 U of DreamTaq polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics, Vilnius, Lithuania). ISSR-PCR was performed in a Mastercycler ep gradient (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 7 min, followed by 32 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, an annealing step at the specific temperature for each ISSR primer for 45 s, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min. The reaction was completed with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. All reactions were independently repeated at least twice, and only reliably repeated DNA bands were analyzed. A negative control was included in each amplification experiment. PCR products were analyzed using 1.5% agarose gels in 0.5× TBE buffer at a constant voltage of 3.0 V/cm for 5 h. DNA was visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Amplification products were recorded and analyzed using the BioDocAnalyze System (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany). The molecular size of the amplified DNA fragments was determined using GeneRuler™ DNA Ladder Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics, Vilnius, Lithuania).

2.3. Data Analysis

Considering the small size of the studied rivers and the compact location of the sampling sites, all the samples from the same river were treated as belonging to the same population (Table S1). This is also based on expected genetic connectivity driven by clonal growth and the downstream dispersal of vegetative propagules in riverine macrophytes. Samples from multiple sites within the same river were pooled and treated as a single population, reflecting expected genetic connectivity driven by clonal growth and the downstream dispersal of vegetative propagules in riverine macrophytes. Although S. pectinata is a hexaploid species, Nies and Reusch [22] reported that the microsatellite loci behave as if they are diploid. It is believed that the microsatellite loci of Stuckenia evolved independently within the genome on different pairs of chromosomes. Therefore, the resulting allele data matrix was constructed on the basis of this assumption. Potential scoring errors (stuttering, large-allele dropout, and null alleles) were assessed using MICROCHECKER v. 2.2.3 [46] on the basis of deviations from expected heterozygote frequencies and repeat motif structure (1000 Monte Carlo iterations, 95% CI). These analyses did not reveal consistent evidence of null alleles, large allele dropout, or stutter-related scoring errors across loci. Therefore, all loci were retained for downstream analyses.

Reproducible DNA bands produced by ISSR-PCR were scored and compiled into a binary data matrix for further analysis. The presence of a DNA band was represented by a 1, whereas its absence was represented by a 0. Monomorphic bands were excluded from the analysis. The genotyping error of the ISSR markers was assessed on 20 blind samples, as described by Patamsytė et al. [47], and estimated at 1.2% (35 differences in 2955 comparisons). Nonreproducible DNA bands were identified in the consensus samples and eliminated from the analysis of all the samples.

Genetic diversity parameters and differentiation were evaluated across various genotypes (genets). Identical genotypes (ramets) within specific sites were excluded from these assessments to prevent the overestimation of allelic frequencies caused by large clones. Clones were determined using the multilocus matches function in GenAlEx version 6.5 [48]. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was assessed for each locus and population using GENEPOP v4.7.5. Exact tests for codominant microsatellite loci were conducted with a Markov chain algorithm involving 1000 dememorization steps, 100 batches, and 1000 iterations per batch. Significance across loci and populations was determined using Fisher’s combined probability test. The inbreeding coefficient (Fis) and genetic differentiation (FST) were calculated using FSTAT v2.9.4 [49]. The total number of alleles (Na), the number of effective alleles (Ne), and Shannon’s index were calculated using POPGENE 1.31. GenAlEx v. 6.5 was used to determine the number of different SSR alleles recorded in each population (Nd), to calculate the observed heterozygosity (Ho) and expected heterozygosity (He), and to perform principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). The ISSR band richness (Br) and the proportion of polymorphic bands (PLP, at a 5% level) for standardized sample sizes, were analyzed using AFLPDIV v. 1.1 [50]. Genetic diversity parameters, such as Na, Ne, I, He, and P, were calculated from ISSR data for populations and sites separately. Genotypic richness (GR) was calculated for the populations using the following formula [51]: R = (G − 1)/(n − 1), where G represents the different genotypes at a studied site and n represents the total number of individuals sampled from all the studied sites. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was used to measure genetic variability among and within populations of S. pectinata. This AMOVA was conducted using GenAlEx v. 6.5, with significance testing performed through 999 permutations.

The genetic structure describes how allele and genotype frequencies are spatially or hierarchically distributed across populations or sampling units. The genetic structure and degree of admixture among various genotypes and populations, based on ISSR markers, were evaluated using the Bayesian clustering method incorporated in the software STRUCTURE version 2.3.4. An admixture model was employed for this analysis [52]. The likelihood L(K) and the values of K (∆K) were computed for sites ranging from K = 1 to 30 and for populations from K = 1 to 10. The optimal number of clusters (K) was identified following the criteria established by Evanno et al. [53], with the aid of STRUCTURE HARVESTER [54]. The methodology included an initial burn-in period consisting of 20,000 steps, followed by 40,000 iterations of the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method, with ten independent replicates conducted for each analysis.

The Mantel test, as implemented in GenAlEx v. 6.5, was conducted using 999 random permutations to evaluate the influence of geographical distance on population genetic structure. Correlations were calculated between estimates of genetic distance (FST or ΦPT) for pairs of sites and the corresponding pairwise geographic distances between those sites, based on data obtained from microsatellite and ISSR markers.

To analyze differences between groups of sites categorized by river modification status (Table S1), we used IBM SPSS Statistics v.23 for Windows and performed the Mann–Whitney U test. We assessed Pearson correlations between genetic diversity parameters Na, Ne, I, He, P, and average values of indices of water chemical and physical characteristics for ten years (2008–2017) near sampling sites (pH, dissolved oxygen, BOD7, NH4-N, NO2-N, NO3-N, mineral N, total N, PO4-P, total P, and specific electrical conductivity (SEC)). Additionally, we evaluated whether there was a correlation between the genetic diversity parameters of S. pectinata populations and river length (L), basin size (S), and discharge (D).

3. Results

3.1. SSR Analysis of S. pectinata Populations

SSR analysis was conducted on plants from nine populations. Nine SSR loci yielded 78 alleles (Table 1).

Table 1.

Genetic parameters of nine microsatellite loci of S. pectinata analyzed across nine populations.

Among them, 14 alleles were identified at the Potpect26 locus, with the highest number reported per locus in this study. The least number of alleles (5) was identified at the Potpect28 locus. The average number of alleles identified per locus was 8.67. The number of plants studied per population varied from 15 (NEM population) to 24 (NER population). Among the studied plants, 52 unique genotypes were identified, along with 25 multiclonal genotypes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genotypic characteristics of S. pectinata plants studied across nine different populations based on an analysis of nine SSR loci.

The highest number of unique genotypes (9) was found in NEM and NER populations. Only one multilocus genotype was identified in each of the three populations (NEM, ZEI, and SVE). The largest clone was distributed among two populations, NEV and SVE. The SVE population was monomorphic. The average number of SSR alleles identified per primer per population was 3.086 ± 0.142, ranging from 1.667 (SVE) to 4.111 (NEM) (Table S2).

When ramets were excluded from the analysis, the number of analyzed populations was reduced to eight. In this case, the average number of studied genotypes per population was 9.5, and the average number of alleles per population was 3.264 ± 0.248. This parameter varied among populations from 1.889 (ULA) to 4.111 (NEM). A comparison of observed heterozygosities (HO) among the populations showed similar variations, ranging from 0.642 ± 0.104 (ZEI) to 0.821 ± 0.063 (NER), as shown in Table 3. Deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium were observed (p < 0.01) at most loci across all populations, mainly due to heterozygote excess. Fis values in all populations were negative (Table 3).

Table 3.

Genetic diversity parameters of the examined S. pectinata populations based on an analysis of nine microsatellite loci.

3.2. ISSR Analysis of S. pectinata Populations

In the initial phase, eight ISSR primers were utilized to analyze the same nine populations and genotypes as in the SSR polymorphism study. These primers successfully identified 146 polymorphic and scorable amplified DNA bands, with a total of 18.25 bands detected per primer (Table S3). The sizes of these DNA bands varied from 380 to 2000 bp. The average polymorphism per primer across all samples was 73.27%. The average polymorphism per population was 32.65 ± 5.39% (Table S4). Private DNA bands were observed in ULA and SES populations. The average number of observed alleles per locus (Na) was found to be 1.326 ± 0.054, and the average number of effective alleles (Ne) was 1.196 ± 0.035. The expected heterozygosity (He) was estimated at 0.123 ± 0.020, and the average Shannon’s index was calculated to be 0.180 ± 0.029.

We assessed the correlation of genetic distances between genotypes obtained by ISSR and SSR markers, yielding a correlation coefficient of r = 0.592 and a p-value of 0.001. Furthermore, we examined the correlations between ΦPT matrices obtained from these markers, which resulted in a statistically significant correlation of r = 0.619 with a p-value of 0.001. Given the correlation between the genetic distances determined with both types of markers, we conducted a larger study using only ISSR markers. We analyzed 381 plants from 10 different populations using 8 ISSR primers, which identified 159 polymorphic ISSR bands. From this analysis, we identified 287 unique genotypes (genets). The parameters of population genetic diversity were determined using these genotypes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Genetic diversity parameters of the examined S. pectinata populations based on an analysis of 159 ISSR loci.

The analysis of these genets revealed an average polymorphism of ISSR loci in the population of 41.76% ± 5.49%. The highest polymorphism was observed in the NER population at 68.55%, while the lowest was in the STR population at 18.24%. When rarefaction was performed on populations of 8 individuals, the highest PLP5% value (0.686) was observed in the NER population, while the lowest (0.182) was found in the STR population. The band richness (Br [8]) was also highest (1.526) in the NER population and the least (1.159) in the STR population. Additionally, the average number of observed alleles (Na) was 1.418 ± 0.055, and the average number of effective alleles (Ne) was 1.260 ± 0.034. The average Shannon’s index (I) was 0.223 ± 0.029, and the average expected heterozygosity (He) was 0.150 ± 0.019. All of these parameters (Na, Ne, I, and He) reached the highest values in the NER population and the lowest in the STR population.

3.3. Population Genetic Structure

An analysis of the genetic structure among eight populations of S. pectinata, conducted using SSR markers, indicated an average genetic differentiation (FST = 0.212). Additionally, an AMOVA revealed that a significant portion of genetic variability exists within the populations themselves (ΦPT = 0.352). In a subsequent analysis involving ISSR markers and double the number of genotypes from ten populations, it was again found that a greater share of genetic variability resides within populations (ΦPT = 0.432) (Table S5). In the hierarchical analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA), the genetic differentiation observed between the regions (river basins) was 20%. The genetic structure of ten populations was assessed using PCoA and STRUCTURE.

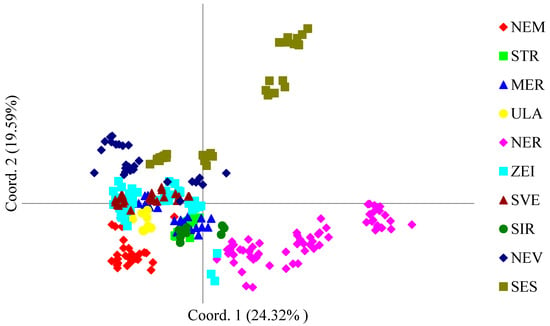

In general, based on the PCoA of ISSR markers, genotypes were grouped into two or three main clusters. The results of the PCoA indicated that most of the population genotypes formed a common genetic pool and tended to intermingle. However, a portion of the SES and NER populations exhibited significant differences compared to the other groups (Figure 2). The first coordinate axis accounted for 24.32% of the total variability, the second for 19.59%, and the third for 16.23%.

Figure 2.

The grouping of S. pectinata plants from 10 populations is shown in the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plot on the basis of 159 polymorphic ISSR loci. The site codes correspond to those explained in Table 2.

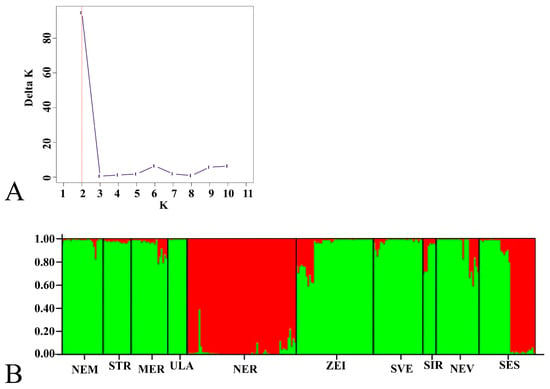

Using the STRUCTURE software to evaluate the genetic structure of the populations, the highest DeltaK value was identified at K = 2 (94,6) (Figure 3A). This suggests that the genetic structure consists of two distinct genotype pools, represented here in two colors: green and red (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

The genetic structure of S. pectinata populations based on ISSR markers. (A). The most probable (K = 2) number of genotype clusters in the studied S. pectinata populations, determined using Evanno’s Delta K method. (B). Genetic structuring of S. pectinata populations at K = 2, as revealed by STRUCTURE analysis. The codes below the bar indicate the populations as listed in Table 4. Each individual is represented by a thin vertical line, with the color corresponding to its assignment to one of the K clusters. Black lines separate the different populations.

The red cluster comprised the genotypes of the NER population (NER1-NER4 sites) and some genotypes from the SES population (SES3 and SES4 sites). The SES population was heterogeneous, containing genotypes from both clusters. The eight remaining populations were grouped into the green cluster, with varying levels of admixture from the red genotype pool in all populations except for ULA.

The Mantel test revealed no significant correlation (r = 0.09; p > 0.05, r = 0.297; p > 0.05) between geographical distances and genetic distances among the sites, as evaluated using both SSR and ISSR markers, respectively.

3.4. A Comparison of Genetic Diversity and Habitat Parameters

To better understand the potential relationships between water chemical parameters and population genetic parameters, we calculated the latter for each plant collection site (Table S6). This study examined genetic parameters, including P%, Br, Nd, Na, Ne, I, and He, for each site. Our analysis of data concerning water physicochemical characteristics revealed that the lowest levels of dissolved oxygen (O2) were found at the NEV2, SES2, SIR1, and NEV3 sites (Table S7). The highest biochemical oxygen demand over a 7-day period (BOD 7) occurred at the NER3, SES4, NEM1, NEM2, NER4, and SES2 locations. Regarding nutrient concentrations, the highest levels of ammonium nitrogen (NH4-N) were observed at SES2, followed by SES4 and NER3. For nitrite nitrogen (NO2-N), the highest concentrations were found at MER1 and MER2, while nitrate nitrogen (NO3-N) levels peaked at NEV3 and NEV1. The total nitrogen levels were highest at NEV3, NEV1, NEV2, and SES4, and total phosphorus concentrations were highest at SES4, SES2, SES3, and SIR2. The pH levels ranged from 7.78 at NEV1 to 8.41 at STR3. However, we found no statistically significant correlation (Pearson correlation, p > 0.05) between the genetic parameters of S. pectinata and the physicochemical water characteristics of the sites (Table S8). The comparison of genotypic richness between natural and modified river stretches revealed no statistically significant difference between the two habitat types. Although genotypic richness tended to be higher in natural river stretches (mean rank = 6.40) than in modified stretches (mean rank = 4.60), the Mann–Whitney U test indicated that this difference was not significant (U = 8.0, Z = −0.95, p = 0.343). This suggests that river modification does not lead to a clear reduction in genotypic richness. Additionally, we assessed the relationship between population genetic diversity parameters and factors such as river basin size, river length, discharge, and river modification; however, no significant correlations were detected.

4. Discussion

Our study of the S. pectinata population in Lithuanian rivers revealed that both molecular markers are informative for analyzing genetic diversity. Nybom [55] emphasized that a minimum fourfold excess of dominant markers is necessary to achieve comparable resolution and statistical power to that of codominant markers, thereby reducing bias in marker-based comparisons [55,56]. Following this recommendation, our analysis included nine SSR loci as codominant markers and 159 ISSR loci as dominant markers. The Mantel test revealed a strong and significant concordance in population genetic diversity estimates between the two marker systems. Notably, studies employing two or more marker systems are quite common [2,56,57,58,59,60,61]. The use of two or more molecular markers provides a more detailed insight into the allocation of genetic diversity among populations and the evolutionary factors that shape their genetic structure [56]. This approach helps avoid biases arising from the specific molecular nature and distribution of certain markers within a species’ genome. A significant correlation between markers suggests compatibility and indicates that the observed DNA polymorphism is largely independent of marker-specific factors and is influenced by key evolutionary forces such as genetic drift and migration [56,58].

4.1. Genetic Diversity

In our study, within-population genetic variation estimated by SSR markers was generally greater than that estimated by ISSR markers and showed greater dispersion. The percentage of polymorphic SSR loci was more than twice as high (97.22%) as that of ISSR loci, which was 41.76%. This finding supports earlier observations regarding the superior resolution of codominant markers in capturing intrapopulation variability [55,56].

As previously mentioned, the genetic diversity of S. pectinata is relatively high and cannot be solely attributed to vegetative propagation. Clones are common within populations, which is a characteristic typical of species that depend on vegetative reproduction. Usually, clones are specific to a site. However, one clone was found in three different locations. High genotypic richness in some rivers (MER, SES, NEM, SIR, ZEI, and NER) suggests that sexual recruitment occasionally produces new genotypes, which then spread through clonal growth. Rivers with the highest genotypic richness and the greatest number of unique genotypes also exhibit relatively high allelic richness and expected heterozygosity, indicating a greater contribution from sexual reproduction. S. pectinata propagules from these rivers could be used as starting material in cases of river restoration. Using SSR markers, we examined 151 individuals and identified 78 SSR alleles. This number of alleles is greater than that reported by Triest and Fénart [23] and Nies and Reusch [44], who reported 56 and 65 alleles, respectively, but fewer than the 130 alleles reported by Abassi et al. [26]. Triest and Fénart [23] collected plants from a small section of the Woluwe River in Belgium, spanning approximately 10 km. In contrast, the populations studied by Abassi et al. [26] were separated by distances of up to 1200 km, including barriers such as deserts and mountains. The geographical distribution of the populations in our study resembled that of Nies and Reusch [44], who analyzed 192 individuals and examined 40 genotypes from the Baltic Sea and nearby lakes. The fact that our study involved nine different rivers may have contributed to the greater number of identified alleles.

Our studies indicated that the Fis value for all the populations was negative, which suggests an excess of heterozygotes. This phenomenon might be attributed to selective forces that increase the adaptability of heterozygotic genotypes [62]. Heterozygote excess across loci does not align with a typical Wahlund effect and instead indicates the widespread occurrence of clonal reproduction. Because S. pectinata mainly reproduces vegetatively, long-lived clonal genotypes may retain the genetic signature of historically successful, possibly heterozygous founders. Another possibility is that recurring bottlenecks, followed by clonal expansion, may help maintain high-fitness, heterozygous individuals. Previously, it has been suggested [10,23,63] that the preservation of macrophyte species at a specific river site relies primarily on the presence of long-lived clones. Heterozygote excess in S. pectinata was also observed at several sites in the Woluwe River catchment by Triest and Fénart [23].

4.2. Genetic Differentiation and Population Structure

In terms of genetic differentiation, the FST value (FST = 0.212) obtained in our study was comparable with those reported in Belgium and Germany. Triest and Fénart [23] reported an FST value of 0.165, whereas Nies and Reisch [22] reported an FST of 0.234 for freshwater lake populations. According to the authors, compared with Baltic Sea populations of S. pectinata, which are not separated by geobarriers, lake populations exhibit greater genetic differentiation due to physical isolation. The higher FST value in our study can be explained by the greater isolation among S. pectinata populations from different Lithuanian rivers, than among populations from the Woluwe River catchment, the latter of which are located in proximity to each other. Furthermore, the FST values reported by Abbasi et al. [26] were higher, at 0.336. This greater differentiation, as noted by the authors, can be attributed to the significantly greater isolation of Iranian populations, which were separated by mountains and deserts, and the ecological diversity of their habitats. The genetic differentiation among S. pectinata populations, as revealed in our study using ISSR markers, was notably greater (ΦPT = 0.352; ΦPT = 0.432). This can be attributed to the impact of the dominant marker system. In some cases, compared with codominant markers, dominant markers indicate a greater level of genetic differentiation [20,55].

The results of the principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) and STRUCTURE analysis of the Lithuanian S. pectinata populations are similar. The PCoA plot indicates that the NER population and some genotypes from the SES population are located outside the main genotype cluster. Additionally, the STRUCTURE analysis separated these two genotype groups into a distinct genotype pool, represented by the red cluster. Our findings indicate that genetic differences among the river populations of S. pectinata are likely caused by genetic drift and possibly due to local adaptation [22,23]. Research by several authors [22,29,64,65] has demonstrated that habitat and local conditions affect population differentiation and separation in principal coordinate analysis graphs. Both genotype pools were present in natural and modified river sites, suggesting that the site disturbance status did not affect this genotype grouping. The absence of significant statistical differences suggests that historical colonization and drift might have a larger impact than recent river modifications on shaping the current genetic structure. Isolation by distance was not identified as a primary factor, as the Mantel test did not reveal a significant correlation between genetic and geographic distances among sites (p > 0.05). The two genotype pools (K = 2) identified in our STRUCTURE analysis may be associated with the genetic lineages described by Fehrer et al. [28] in their taxonomic and molecular study of the genus Stuckenia. These authors revealed two lineages (African and European) within S. pectinata, and identified intraspecific hybrids in Central Europe. Recently, Triest et al. [29] revealed subdivision within the European gene pool, which was interpreted as reflecting historical divergence between freshwater and brackish ecotypes. Our results show that the NER population and some of the SES population form a distinct genetic cluster and may thus represent remnants of this ancient differentiation, which is potentially linked to local adaptation to different salinity or hydrological conditions. Although all the Lithuanian sites examined here are in freshwater systems, the persistence of distinct genetic lineages could reflect historical connectivity with brackish water systems of the Baltic Basin or long-term reproductive isolation among populations in different river systems. This interpretation is consistent with the findings of Fehrer et al. [28], who reported that interspecific and intraspecific hybridization, as well as environmentally induced phenotypic variation, are common in Stuckenia, suggesting that the genetic structure observed in our data may also encompass adaptive differentiation rather than purely neutral processes. Additionally, while the two clusters we detect are consistent with the existence of multiple gene pools within the European range, our dataset does not include the same markers and geographic coverage as Triest et al. [29], and we therefore cannot assign our clusters unambiguously to their identified ecotypes.

Overall, the genetic diversity and structure of Lithuanian S. pectinata populations appear to result from a combination of historical divergence, local adaptation, and stochastic evolutionary processes rather than contemporary geographic or environmental factors. The differentiation of the NER and some of the SES populations into a distinct genetic cluster may represent the persistence of ancestral genetic lineages, potentially linked to historical connections with brackish or transitional freshwater systems in the Baltic basin. Despite all the sites being in freshwater systems, the retention of these lineages could suggest limited gene flow and long-term isolation among populations in different river systems. Statistical tests did not reveal strong, consistent differences in the genetic diversity parameters of S. pectinata populations between modified and natural river sites, which may reflect the species’ resilience, differences in the severity of human impacts, or the different timing of the modifications [66,67]. The lack of correlations between genetic diversity indices and hydrochemical parameters likely reflects the manifestation of neutral genetic variation, a disconnect between historical genetic processes and modern environmental conditions, and the strong phenotypic plasticity and clonality of submerged macrophytes. The high within-population variability revealed by SSR markers highlights the ability of S. pectinata to maintain considerable genetic diversity, which may contribute to its ecological plasticity and wide distribution. On the other hand, sometimes genetic composition can respond quickly to environmental changes without noticeable shifts in species abundance [68]. Thus, while S. pectinata is commonly used as a bioindicator species in Europe [6], our results suggest that its genetic diversity and structure primarily reflect historical and intrinsic biological processes rather than current ecological status. Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of considering both the neutral and adaptive components of genetic variation when interpreting population structure and selecting indicator macrophyte species for assessing the ecological status of rivers in monitoring programs.

5. Conclusions

This study provides the first comprehensive assessment of the genetic diversity and structure of Stuckenia pectinata in Lithuanian rivers using complementary SSR and ISSR markers. Both marker systems revealed consistent diversity patterns, with SSRs capturing greater within-population variability and finer-scale genetic resolution. The congruence between markers could suggest that the observed genetic structure reflects evolutionary and demographic processes, including genetic drift, limited dispersal, and clonality. The differentiation of the NER and some of the SES populations likely represents remnants of ancient genetic lineages shaped by historical divergence. The excess heterozygotes observed suggest potential selective advantages contributing to the maintenance of genetic diversity despite predominant vegetative reproduction. No significant correlations were detected between genetic diversity and hydrochemical or hydromorphological factors, indicating the limited influence of the current local environment on the population structure of Sago pondweed. Overall, the high within-population genetic diversity highlights the evolutionary potential and ecological resilience of S. pectinata. However, significant differences in some genetic diversity parameters and genetic richness in Lithuanian rivers highlight the importance of incorporating molecular diversity assessments into freshwater system monitoring programs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d18010026/s1, Table S1: Characteristics of the studied Stuckenia pectinata populations and sites.; Table S2: Genetic diversity parameters of the examined S. pectinata populations based on an analysis of nine microsatellite loci, including clones; Table S3: Primers used for analysis of nine S. pectinata populations, number DNA fragments amplified, number of polymorphic fragments, polymorphism of studied ISSR loci and size of scored ISSR bands; Table S4: Genetic diversity parameters of the nine examined S. pectinata populations based on an analysis of 159 ISSR loci; Table S5: Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) of Stuckenia pectinata populations based on ISSR data; Table S6: Genetic diversity parameters of the 30 examined S. pectinata sites based on an analysis of 159 ISSR loci; Table S7: Water physicochemical characteristics at studied S. pectinata sites; Table S8: Correlation between genetic parameters of S. pectinata across the 30 studied sites and their physicochemical water characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Ž., J.P. and J.B.; methodology, J.P.; software, J.P. and D.N.; formal analysis, D.N. and J.B.; investigation, J.P. and D.Ž.; resources, D.Ž. and J.P.; data curation, J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Ž.; writing—review and editing, D.Ž., J.P. and J.B.; visualization, J.P.; supervision, D.Ž.; funding acquisition, D.Ž. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Council of Lithuania (SIT-2/2015).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Zofija Sinkevičienė of the Flora and Geobotany Laboratory of the Nature Research Center for her expert assistance during field research and taxonomic identification of plants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ramsar Convention Secretariat. Wise use of wetlands: Concepts and approaches for the wise use of wetlands. In Ramsar Handbooks for the Wise Use of Wetlands, 4th ed.; Ramsar Convention Secretariat: Gland, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, N.O.; Krokaitė-Kudakienė, E.; Jocienė, L.; Rekašius, T.; Chernyagina, O.A.; Paulauskas, A.; Kupčinskienė, E. Genetic Differentiation of Reed Canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea L.) within Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Genes 2024, 15, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrat-Segretain, M.H. Strategies of reproduction, dispersion, and competition in river plants: A Review. Vegetatio 1996, 123, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, P.A.; Bhardwaj, A.K.; Bahar, F.A. A Study of Comparative Purification Efficiency of Two Species of Potamogeton (Submerged Macrophyte) In Wastewater Treatment. IJSRP 2013, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.N.; Dong, J.; Fu, Q.Q.; Wang, Y.P.; Chen, C.; Li, J.H.; Li, R.; Zhou, C.J. Allelopathic effects of submerged macrophytes on phytoplankton. Allelopath. J. 2017, 40, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poikane, S.; Portielje, R.; Denys, L.; Elferts, D.; Kelly, M.; Kolada, A.; Mäemets, H.; Phillips, G.; Søndergaard, M.; Willby, N.; et al. Macrophyte assessment in European lakes: Diverse approaches but convergent views of ‘good’ ecological status. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malea, L.; Nakou, K.; Papadimitriou, A.; Exadactylos, A.; Orfanidis, S. Physiological Responses of the Submerged Macrophyte Stuckenia pectinata to High Salinity and Irradiance Stress to Assess Eutrophication Management and Climatic Effects: An Integrative Approach. Water 2021, 13, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganie, A.H.; Reshi, Z.A.; Wafai, B.A. Reproductive ecology of Potamogeton pectinatus L. (= Stuckenia pectinata (L.) Börner) in relation to its spread and abundance in freshwater ecosystems of the Kashmir Valley, India. Trop. Ecol. 2016, 57, 787–803. [Google Scholar]

- Misteli, B.; Pannard, A.; Labat, F.; Fosso, L.K.; Baso, N.C.; Harpenslager, S.F.; Motitsoe, S.N.; Thiebaut, G.; Piscart, C. How Invasive Macrophytes Affect Macroinvertebrate Assemblages and Sampling Efficiency: Results from a Multinational Survey. Limnologica 2022, 96, 125998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanepoel, J.H.; Vermaak, J.F. Preliminary results on the uptake and release of 32P by Potamogeton pectinatus. J. Limnol. Soc. S. Afr. 1977, 3, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janauer, G.A. Veränderungen organischer und anorganischer Inhaltsstoffe in Potamogeton pectinatus L. bei steigender Gewasserbelastung. Metabolic changes in Potamogeton pectinatus L. by enhanced eutrophication. Flora 1979, 168, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijk, R.J. Ecological studies on Potamogeton pectinatus L. III. Reproductive strategies and germination ecology. Aquat. Bot. 1989, 33, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegleb, G.; Brux, H.; Herr, W. Human impact on the ecological performance of Potamogeton species in northwestern Germany. Vegetatio 1991, 97, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernez, I.; Chicouène, D.; Haury, J. Changes of Potamogeton pectinatus clumps under variable, artificially flooded river water regimes. Belg. J. Bot. 2007, 140, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Nolet, B.A.; Langevoord, O.; Bevan, R.M.; Engelaar, K.R.; Klaassen, M.; Mulder, R.J.W.; Van Dijk, S. Spatial variation in tuber depletion by swans explained by differences in net intake rates. Ecology 2001, 82, 1655–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søndergaard, M.; Johansson, L.S.; Lauridsen, T.L.; Jørgensen, T.B.; Liboriussen, L.; Jeppesen, E. Submerged macrophytes as indicators of the ecological quality of lakes. Freshw. Biol. 2010, 55, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, P.; Triest, L. Isozyme polymorphism in the genus Potamogeton (Potamogetonaceae). In Isozymes in Water Plants; Opera Botanica Belgica; Triest, L., Ed.; National Botanical Garden of Belgium: Meise, Belgium, 1991; Volume 4, pp. 89–116. ISBN 9789072619037. [Google Scholar]

- Gornall, R.; Hollingsworth, P.; Preston, C. Evidence for spatial structure and directional gene flow in a population of an aquatic plant, Potamogeton coloratus. Heredity 1998, 80, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, E.; van Viersen, W.; Schwenk, K. Clonal diversity in the submerged macrophyte Potamogeton pectinatus L. inferred from nuclear and cytoplasmic variation. Aquat. Bot. 1998, 62, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hangelbroek, H.H.; Ouborg, N.J.; Santamaria, L.; Schwenk, K. Clonal diversity and structure within a population of the pondweed Potamogeton pectinatus foraged by Bewick’s Swans. Mol. Ecol. 2002, 11, 2137–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.A.; Gornall, R.J.; Preston, C.D.; Croft, J.M. Population differentiation of Potamogeton pectinatus in the Baltic Sea with reference to waterfowl dispersal. Mol. Ecol. 2002, 11, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nies, G.; Reusch, T.B.H. Evolutionary divergence and possible incipient speciation in post-glacial populations of a cosmopolitan aquatic plant. J. Evol. Biol. 2005, 18, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triest, L.; Fénart, S. Clonal diversity and spatial genetic structure of Potamogeton pectinatus in managed pond and river populations. Hydrobiologia 2014, 737, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Wang, G.; Li, W.; Liu, F. Genetic diversity of Potamogeton pectinatus L. in relation to species diversity in a pair of lakes of contrasting trophic levels. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2014, 57, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkova, P.A.; Kipriyanova, L.M.; Maltseva, S.Y.; Bobrov, A.A. In search of speciation: Diversification of Stuckenia pectinata s.l. (Potamogetonaceae) in southern Siberia (Asian Russia). Aquat. Bot. 2017, 143, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Afsharzadeh, S.; Saeidi, H.; Triest, L. Strong Genetic Differentiation of Submerged Plant Populations across Mountain Ranges: Evidence from Potamogeton pectinatus in Iran. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Afsharzadeh, S.; Saeidi, H. Genetic diversity of Potamogeton pectinatus L. in Iran as revealed by ISSR markers. Acta Bot. Croat. 2017, 76, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehrer, J.; Nagy Nejedlá, M.; Hellquist, C.B.; Bobrov, A.A.; Kaplan, Z. Evolutionary history and patterns of geographical variation, fertility, and hybridization in Stuckenia (Potamogetonaceae). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1042517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triest, L.; Bossaer, L.; Hailu, A.B.; Mäemets, H.; Terer, T.; Tóth, V.R.; Sierens, T.A. Pleistocene legacy of gene pools, ecodemes and admixtures of Stuckenia pectinata (L.) Börner as evidenced from microsatellites, complete chloroplast genomes and ribosomal RNA cistron (Europe, Africa). Aquat. Bot. 2025, 196, 103825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyšniauskienė, R.; Rančelienė, V.; Naugžemys, D.; Rudaitytė-Lukošienė, E.; Patamsytė, J.; Butkauskas, D.; Kupčinskienė, E.; Žvingila, D. Genetic diversity of Nuphar lutea in Lithuanian river populations. Aquat. Bot. 2020, 161, 103–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonskis, J.; Kovalenkovienė, M.; Tamkevičienė, A. Channel network of the Lithuanian rivers and small streams. Ann. Geograph. 2007, 40, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, E.; Fisher, H.S.; Grimm, N.B. Ecosystem expansion and contraction: A desert stream perspective. BioScience 1997, 47, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Moggridge, H.; Warren, P.; Shucksmith, J. The Impacts of ‘run-of-river’ Hydropower on the Physical and Ecological Condition of Rivers. Water Environ. J. 2015, 29, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroita, M.; Flores, L.; Larrañaga, A.; Martínez, A.; Martínez-Santos, M.; Pereda, O.; Ruiz-Romera, E.; Salagaistua, L.; Elosegi, A. Water Abstraction Impacts Stream Ecosystem Functioning via Wetted-Channel Contraction. Freshw. Biol. 2017, 62, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, S.; Arthington, A. Basic Principles and Ecological Consequences of Altered Flow Regimes for Aquatic Biodiversity. Environ. Manag. 2002, 30, 492–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Li, M.; Guo, X.; Yin, M.; Cai, Y.; Yu, X.; Du, N.; Wang, R.; et al. Impacts of the Yellow River and Qingtongxia dams on genetic diversity of Phragmites australis in Ningxia Plain, China. Aquat. Bot. 2021, 169, 103341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanch, S.J.; Ganf, G.G.; Walker, K.F. Tolerance of riverine plants to flooding and exposure indicated by water regime. Regul. Rivers Res. Manag. 1999, 15, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naugžemys, D.; Lambertini, C.; Patamsytė, J.; Butkuvienė, J.; Khasdan, V.; Žvingila, D. Genetic diversity patterns in Phragmites australis populations in straightened and in natural river sites in Lithuania. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 3317–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsford, R.T. Ecological impacts of dams, water diversions and river management on floodplain wetlands in Australia. Austral. Ecol. 2000, 25, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erős, T.; Kuehne, L.; Dolezsai, A.; Sommerwerk, N.; Wolter, C. A systematic review of assessment and conservation management in large floodplain rivers—Actions postponed. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokaitė, E.; Shakeneva, D.; Juškaitytė, E.; Rekašius, T.; Nemaniūtė-Gužienė, J.; Butkuvienė, J.; Patamsytė, J.; Rančelienė, V.; Vyšniauskienė, R.; Duchovskienė, L.; et al. Nitrogen concentration of the aquatic plant species in relation to land cover type and other variables of the environment. Zemdirb. Agric. 2019, 106, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegleb, G.; Kaplan, Z. An account of the species of Potamogeton L. (Potamogetonaceae). Folia Geobot. 1998, 33, 241–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.J. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nies, G.; Reusch, T.B.H. Nine polymorphic microsatellite loci for the fennel Pondweed Potamogeton pectinatus L. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2004, 4, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patamsytė, J.; Naugžemys, D.; Čėsnienė, T.; Kleizaitė, V.; Demina, O.N.; Mikhailova, S.I.; Agafonov, V.A.; Žvingila, D. Evaluation and comparison of the genetic structure of Bunias orientalis populations in their native range and two non-native ranges. Plant Ecol. 2018, 219, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oosterhout, C.; Hutchinson, W.F.; Wills, D.P.M.; Shipley, P. MICRO-CHECKER: Software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol.Ecol. Notes 2004, 4, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patamsytė, J.; Rančelis, V.; Čėsnienė, T.; Kleizaitė, V.; Tunaitienė, V.; Naugžemys, D.; Vaitkūnienė, V.; Žvingila, D. Clonal structure and reduced diversity of the invasive alien plant Erigeron annuus in Lithuania. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2013, 8, 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—An update. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudet, J. FSTAT (Version 2.9.4), a Program to Estimate and Test Population Genetics Parameters. 2003. Available online: http://www2.unil.ch/popgen/softwares/fstat.htm (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Coart, E.; Van Glabeke, S.; Petit, R.J.; Van Bockstaele, E.; Roldán-Ruiz, I. Range-wide versus local patterns of genetic diversity in hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.). Conserv. Genet. 2005, 6, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorken, M.E.; Eckert, C.G. Severely reduced sexual reproduction in northern populations of a clonal plant, Decodon verticillatus (Lythraceae). J. Ecol. 2001, 89, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falush, D.; Stephens, M.; Pritchard, K.J. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Dominant markers and null alleles. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, D.A.; von Holdt, B.M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2012, 4, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nybom, H. Comparison of different nuclear DNA markers for estimating intraspecific genetic diversity in plants. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 1143e1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, S.X.; Mendonça, D.; Lopes, M.S.; Rocha, S.; Monjardino, P.; Monteiro, L.; da Câmara Machado, A. Genetic diversity and population structure of the endemic Azorean juniper, Juniperus brevifolia (Seub.) Antoine, inferred from SSRs and ISSR markers. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2015, 59, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Fahima, T.; Krugman, T.; Beiles, A.; Röder, M.S.; Korol, A.B.; Nevo, E. Parallel microgeographic patterns of genetic diversity and divergence revealed by allozyme, RAPD, and microsatellites in Triticum dicoccoides at Ammiad, Israel. Conserv. Genet. 2000, 1, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariette, S.; Chagné, D.; Lézier, C.; Pastuszka, P.; Raffin, A.; Plomion, C.; Kremer, A. Genetic diversity within and among Pinus pinaster populations: Comparison between AFLP and microsatellite markers. Heredity 2001, 86, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crinò, P.; Pagnotta, M.A. Phenotyping, Genotyping, and Selections within Italian Local Landraces of Romanesco Globe Artichoke. Diversity 2017, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amom, T.; Tikendra, L.; Apana, N.; Goutam, M.; Sonia, P.; Koijam, A.S.; Potshangbam, A.M.; Rahaman, H.; Nongdam, P. Efficiency of RAPD, ISSR, iPBS, SCoT and phytochemical markers in the genetic relationship study of five native and economical important bamboos of North-East India. Phytochemistry 2020, 174, 112330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krokaite, E.; Janulioniene, R.; Jociene, L.; Rekašius, T.; Rajackaite, G.; Paulauskas, A.; Marozas, V.; Kupčinskiene, E. Relating Invasibility and Invasiveness: Case Study of Impatiens parviflora. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 845947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collevatti, R.G.; Grattapaglia, D.; Hay, J.D. Population genetic structure of the endangered tropical tree species Caryocar brasiliense, based on variability at microsatellite loci. Mol. Ecol. 2001, 10, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, L. Why are most aquatic plants widely distributed? Dispersal, clonal growth and small-scale heterogeneity in a stressful environment. Acta Oecol. 2002, 23, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Shen, Y.; Li, M.; Jiang, R.; Cai, L.; Wu, T.; Gao, L.; Wu, M.; He, P. Establishment of Novel Simple Sequence Repeat Markers in Phragmites australis and Application in Wetlands of Nanhui Dongtan, Shanghai. Biology 2025, 14, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Cui, Z.; Shi, W.; Huang, J.; Wang, J. Development of Polymorphic Microsatellite Markers and Identification of Applications for Wild Walnut (Juglans regia L.) in Middle Asia. Diversity 2023, 15, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelton, E.L.G.; McCormick, M.K.; Sievers, M.; Kettenring, K.M.; Whigham, D.F. Stand age is associated with clonal diversity, but not vigor, community structure, or insect herbivory in Chesapeake Bay Phragmites australis. Wetlands 2015, 35, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.O.; Jocienė, L.; Krokaitė, E.; Rekašius, T.; Paulauskas, A.; Kupčinskienė, E. Genetic diversity of Phalaris arundinacea populations in relation to river regulation in the Merkys basin, Lithuania. River Res. Applic. 2018, 34, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoban, S.; Archer, F.I.; Bertola, L.D.; Bragg, J.G.; Breed, M.F.; Bruford, M.W.; Coleman, M.A.; Ekblom, R.; Funk, W.C.; Grueber, C.E.; et al. Global genetic diversity status and trends: Towards a suite of Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs) for genetic composition. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 1511–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.