Foraging Habitat Selection of Shrubland Bird Community During the Dry Season in Tropical Dry Forests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

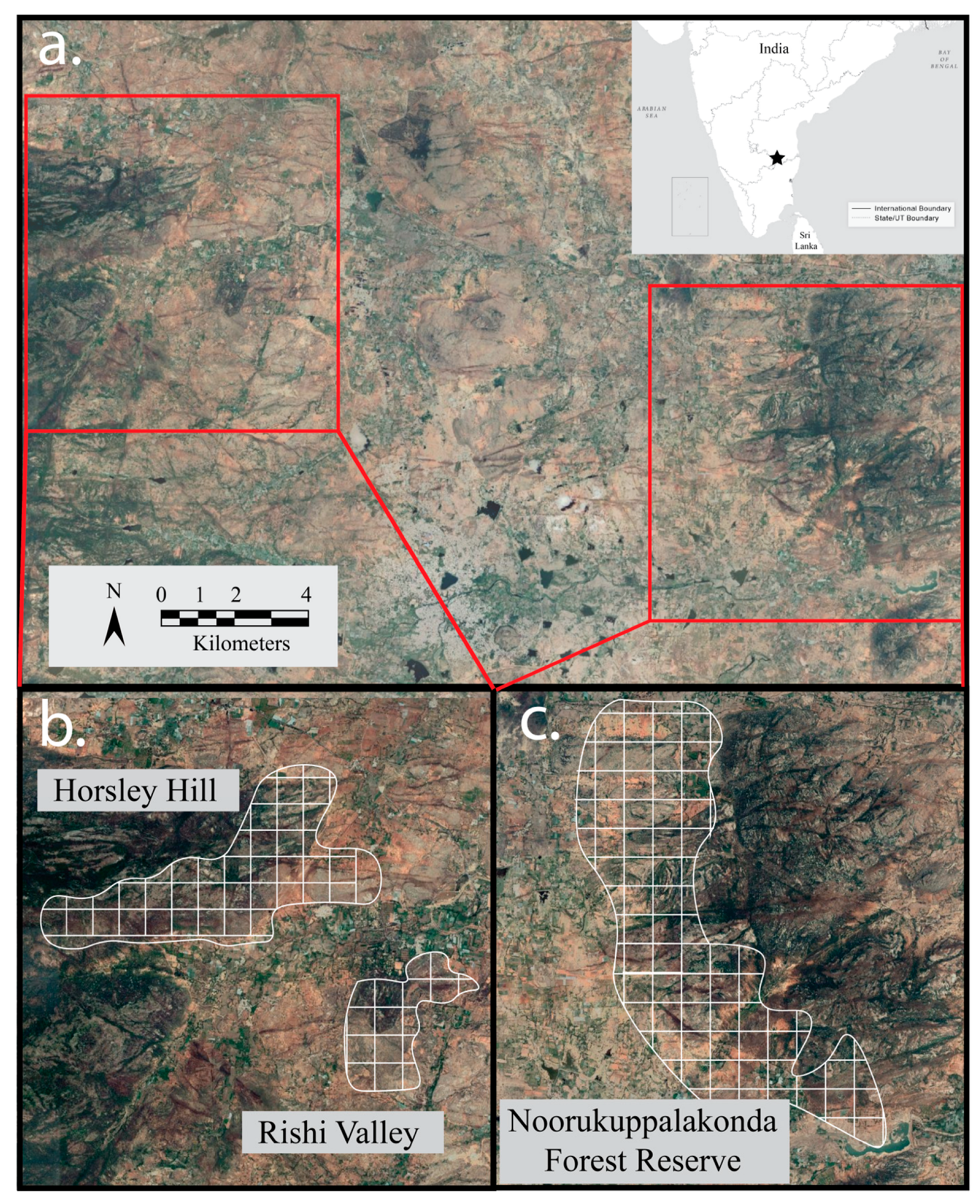

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Study Species

2.3. Bird Surveys and Microhabitat Vegetation Data

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

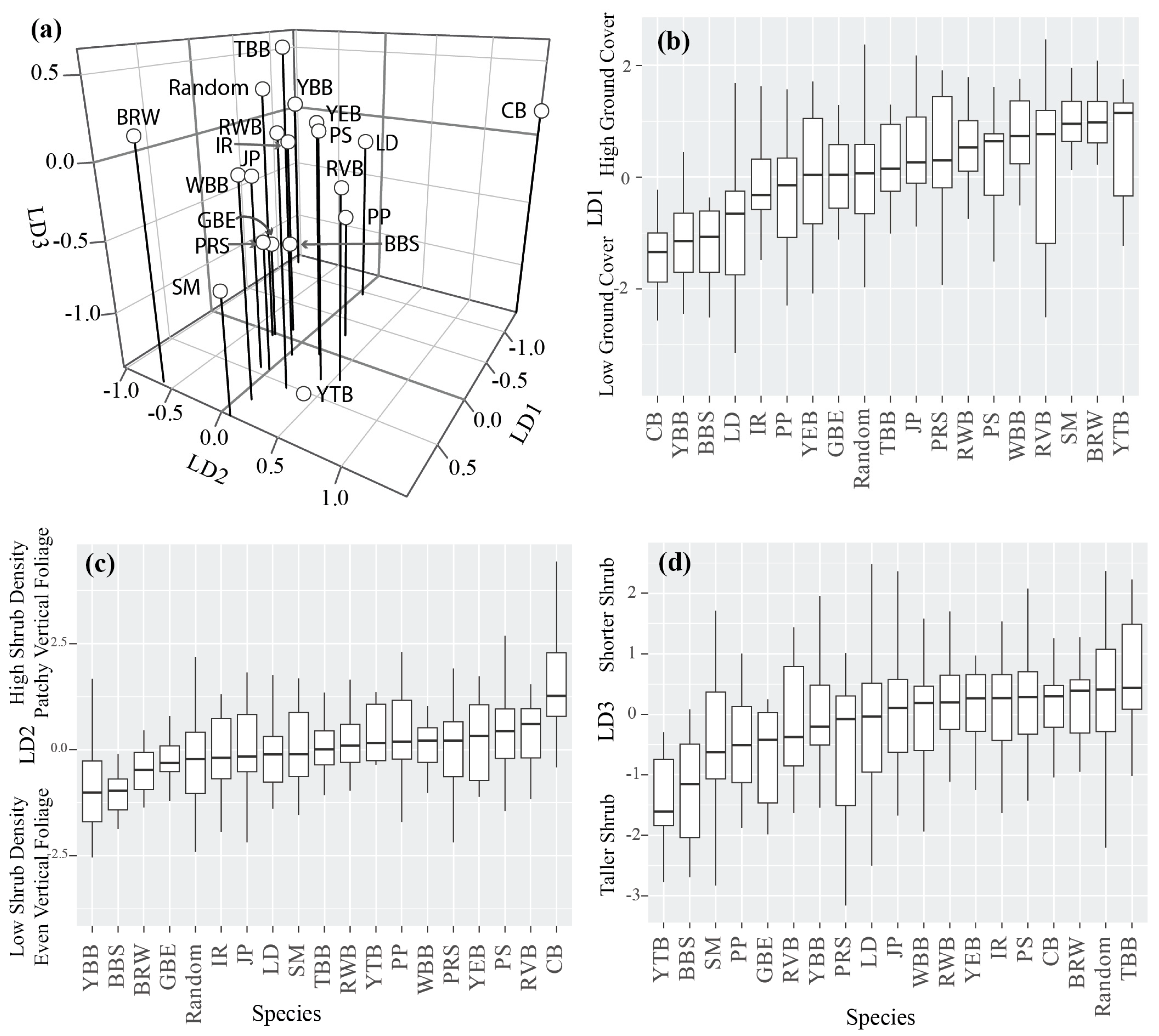

3.1. Microhabitat Selection and Characteristics of Preferred Foraging Sites

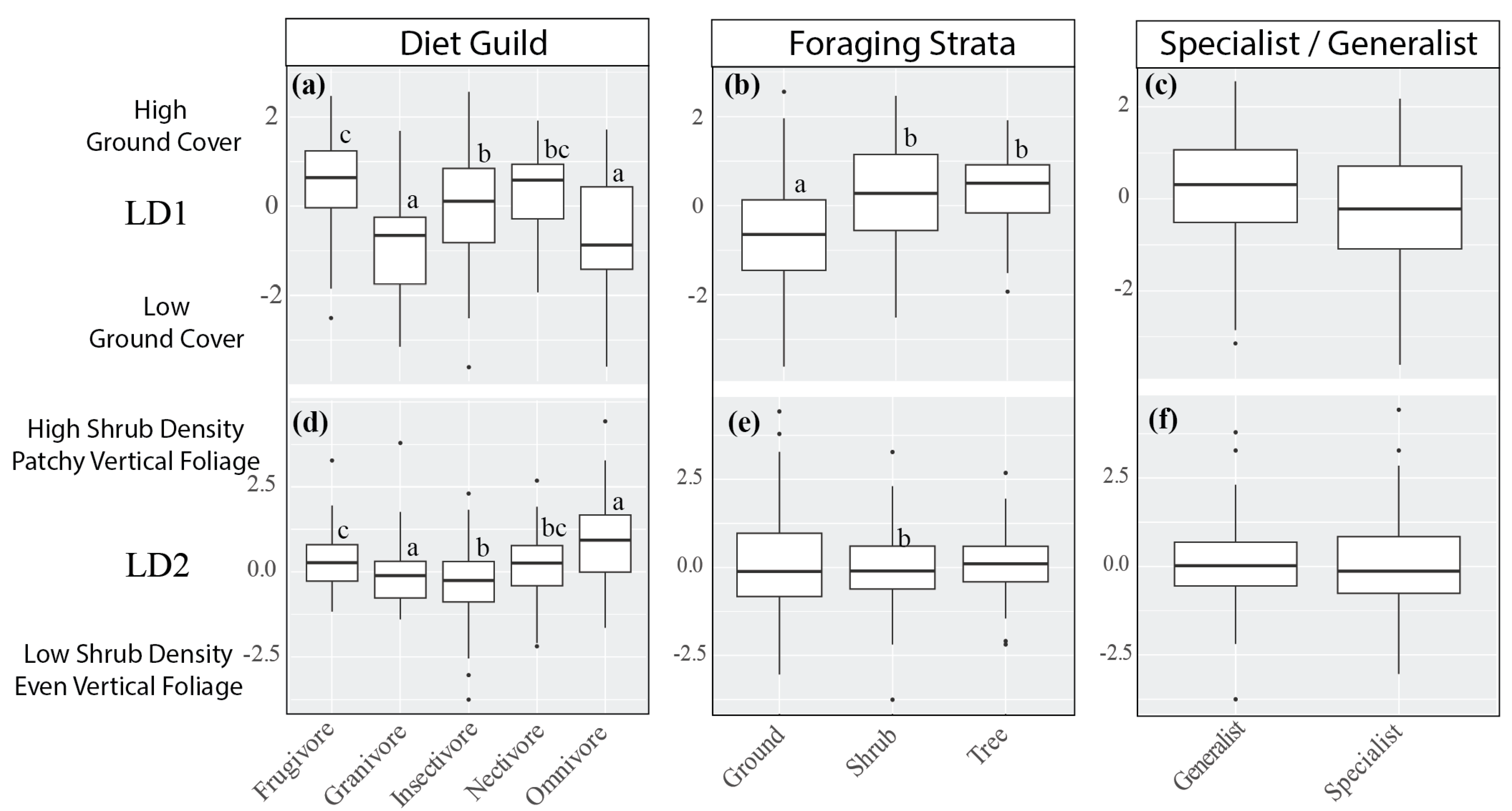

3.2. Effect of Diet Guild, Foraging Strata, and Specialist/Generalist Species

3.3. Association Between Bird Species and Plant Species

4. Discussion

4.1. Plant Associations

4.2. Conservation Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayhoe, K.; Wake, C.P.; Huntington, T.G.; Luo, L.; Schwartz, M.D.; Sheffield, J.; Wood, E.; Anderson, B.; Bradbury, J.; DeGaetano, A. Past and future changes in climate and hydrological indicators in the US Northeast. Clim. Dyn. 2007, 28, 381–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenhouse, N.L.; Matthews, S.; McFarland, K.; Lambert, J.; Iverson, L.; Prasad, A.; Sillett, T.S.; Holmes, R.T. Potential effects of climate change on birds of the Northeast. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2008, 13, 517–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.; Tignor, M.; Miller, H. IPCC fourth assessment report (AR4). Clim. Change 2007, 374. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, M.; Johnson, D.H.; Shaffer, J.A. Variability in vegetation effects on density and nesting success of grassland birds. J. Wildl. Manag. 2005, 69, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breshears, D.D.; Cobb, N.S.; Rich, P.M.; Price, K.P.; Allen, C.D.; Balice, R.G.; Romme, W.H.; Kastens, J.H.; Floyd, M.L.; Belnap, J. Regional vegetation die-off in response to global-change-type drought. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15144–15148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albright, T.P.; Pidgeon, A.M.; Rittenhouse, C.D.; Clayton, M.K.; Flather, C.H.; Culbert, P.D.; Wardlow, B.D.; Radeloff, V.C. Effects of drought on avian community structure. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 2158–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillett, T.S.; Holmes, R.T.; Sherry, T.W. Impacts of a global climate cycle on population dynamics of a migratory songbird. Science 2000, 288, 2040–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyland, F.; Baudry, J.; Ghersa, C. Short-term effects of a severe drought on avian diversity and abundance in a Pampas Agroecosystem. Austral Ecol. 2019, 44, 1340–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzyna, M.A.; Porter, W.F.; Maurer, B.A.; Zuckerberg, B.; Finley, A.O. Landscape fragmentation affects responses of avian communities to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 2942–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cody, M.L. Habitat Selection in Birds; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wiens, J.A. Pattern and process in grassland bird communities. Ecol. Monogr. 1973, 43, 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Newton, W.E.; Lingle, G.R.; Chavez-Ramirez, F. Influence of grazing and available moisture on breeding densities of grassland birds in the central Platte River Valley, Nebraska. Wilson J. Ornithol. 2008, 120, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemuth, N.D.; Solberg, J.W.; Shaffer, T.L. Influence of moisture on density and distribution of grassland birds in North Dakota. Condor 2008, 110, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, K.V.; Dokter, A.M.; Blancher, P.J.; Sauer, J.R.; Smith, A.C.; Smith, P.A.; Stanton, J.C.; Panjabi, A.; Helft, L.; Parr, M. Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 2019, 366, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshwal, A. Ecology and Conservation of Shrubland Bird Communities in the Eastern Ghats of India. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jetz, W.; Wilcove, D.S.; Dobson, A.P. Projected impacts of climate and land-use change on the global diversity of birds. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, 1211–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekercioglu, C.H. Functional extinctions of bird pollinators cause plant declines. Science 2011, 331, 1019–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekercioglu, C.H.; Schneider, S.H.; Fay, J.P.; Loarie, S.R. Climate change, elevational range shifts, and bird extinctions. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loarie, S.R.; Duffy, P.B.; Hamilton, H.; Asner, G.P.; Field, C.B.; Ackerly, D.D. The velocity of climate change. Nature 2009, 462, 1052–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International, B. IUCN Red List for Birds. Available online: https://datazone.birdlife.org (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Ali, S.; Ripley, S.D.; Dick, J.H. Compact Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 1987; p. 890. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.V.; Osman, M.; Mishra, P. Development and application of a new drought severity index for categorizing drought-prone areas: A case study of undivided Andhra Pradesh state, India. Nat. Hazards 2019, 97, 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D. Conserving Biodiversity Outside Protected Areas: Analysis of a Potential Wildlife Corridor in Chittoor District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Master’s Thesis, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, R.M.; Roy, P.S.; Chakravarthi, V.; Sanjay, J.; Joshi, P.K. Long-term land use and land cover changes (1920–2015) in Eastern Ghats, India: Pattern of dynamics and challenges in plant species conservation. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 85, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Officer, C.P. (Government of Andhra Pradesh). Hand Book of Statistics 2016 Chittoor District; Government of Andhra Pradesh: Chittoor District, India, 2016; pp. 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Manea, A.; Sloane, D.R.; Leishman, M.R. Reductions in native grass biomass associated with drought facilitates the invasion of an exotic grass into a model grassland system. Oecologia 2016, 181, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Brown, J.F.; Verdin, J.P.; Wardlow, B. A five-year analysis of MODIS NDVI and NDWI for grassland drought assessment over the central Great Plains of the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, M. Effects of drought on birds in the Kalahari, Botswana. Ostrich-J. Afr. Ornithol. 2004, 75, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, E.O. Seasonal changes in the invertebrate litter fauna on Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Rev. Bras. Biol. 1976, 36, 643–657. [Google Scholar]

- Janzen, D.H. Sweep samples of tropical foliage insects: Effects of seasons, vegetation types, elevation, time of day, and insularity. Ecology 1973, 54, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabuddin, G.; Kumar, R. Effects of extractive disturbance on bird assemblages, vegetation structure and floristics in tropical scrub forest, Sariska Tiger Reserve, India. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 246, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesio, L. Effects of human subsistence activities on forest birds in northern Kenya. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.J.; McComb, W.C.; Vega, R.; Raphael, M.G.; Hunter, M. Bird habitat relationships in natural and managed forests in the west Cascades of Oregon. Ecol. Appl. 1995, 5, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L. Tropical forest recovery: Legacies of human impact and natural disturbances. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 6, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, A.; Stephenson, S.L.; Panwar, P.; DeGregorio, B.A.; Kannan, R.; Willson, J.D. Foraging habitat selection of shrubland bird community in tropical dry forest. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International, B. Important Bird Areas Factsheet: Horsley Hills. Available online: http://datazone.birdlife.org/site/factsheet/horsley-hills-iba-india (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- International, B. Important Bird Areas Factsheet: Noorukuppalakonda Reserve Forest. Available online: http://datazone.birdlife.org/site/factsheet/noorukuppalakonda-reserve-forest-iba-india (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Champion, S.H.; Seth, S.K. A Revised Survey of the Forest Types of India; Manager of Publications: Delhi, India, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Center, M.N.C.F. Mahalanobis National Crop Forecast Center. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/partnership/mahalanobis-national-crop-forecast-centre/ (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Tobias, J.A.; Sheard, C.; Pigot, A.L.; Devenish, A.J.; Yang, J.; Sayol, F.; Neate-Clegg, M.H.; Alioravainen, N.; Weeks, T.L.; Barber, R.A. AVONET: Morphological, ecological and geographical data for all birds. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 25, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI. ArcGIS Desktop; Environmental Systems Research Institute: Redlands, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- James, F.C.; Shugart, H.H., Jr. A quantitative method of habitat description. Audubon Field Notes 1970, 24, 727–736. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.G. Distribution of summer birds along a forest moisture gradient in an Ozark watershed. Ecology 1977, 58, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.A. Measuring shrubland vegetational structure using avian habitats as an example. J. Ark. Acad. Sci. 1992, 46, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D.S.; Weatherhead, P.J. A test of the hierarchical model of habitat selection using eastern massasauga rattlesnakes (Sistrurus c. catenatus). Biol. Conserv. 2006, 130, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A. Estimating normalization transformations with bestNormalize. R J. 2021, 13, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- James, F.C. Ordinations of habitat relationships among breeding birds. Wilson Bull. 1971, 83, 215–236. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, J.E.; Robinson, S.K.; Levey, D.J. Squeezed at the top: Interspecific aggression may constrain elevational ranges in tropical birds. Ecology 2010, 91, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, K.L.; Rotenberry, J.T.; Redak, R.A.; Allen, M.F. Habitat shifts of endangered species under altered climate conditions: Importance of biotic interactions. Glob. Change Biol. 2008, 14, 2501–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frith, D.; Frith, C. Seasonality of litter invertebrate populations in an Australian upland tropical rain forest. Biotropica 1990, 22, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNab, B.K. The structure of tropical bat faunas. Ecology 1971, 52, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, M.; Thomas, D. Dry-season overlap in activity patterns, habitat use, and prey selection by sympatric African insectivorous bats. Biotropica 1980, 12, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cady, S.M.; O’Connell, T.J.; Loss, S.R.; Jaffe, N.E.; Davis, C.A. Species-specific and temporal scale-dependent responses of birds to drought. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 2691–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, G.-R. Adapted behaviour and shifting ranges of species—A result of recent climate warming? In “Fingerprints” of Climate Change; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Macías-Duarte, A.; Montoya, A.B.; Méndez-González, C.E.; Rodríguez-Salazar, J.R.; Hunt, W.G.; Krannitz, P.G. Factors influencing habitat use by migratory grassland birds in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico. Auk 2009, 126, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antos, M.J.; Bennett, A.F.; White, J.G. Where exactly do ground-foraging woodland birds forage? Foraging sites and microhabitat selection in temperate woodlands of southern Australia. Emu-Austral Ornithol. 2008, 108, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.J.; Whittingham, M.J.; Bradbury, R.B.; Wilson, J.D.; Kyrkos, A.; Buckingham, D.L.; Evans, A.D. Foraging habitat selection by yellowhammers (Emberiza citrinella) nesting in agriculturally contrasting regions in lowland England. Biol. Conserv. 2001, 101, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.J.; George, T.L. Song post and foraging site characteristics of breeding Varied Thrushes in northwestern California. Condor 2000, 102, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.T.; Robinson, S.K. Tree species preferences of foraging insectivorous birds in a northern hardwoods forest. Oecologia 1981, 48, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, C.J. Foliage structure influences foraging of insectivorous forest birds: An experimental study. Ecology 2001, 82, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remsen, J.V.; Robinson, S.K. A classification scheme for foraging behavior of birds in terrestrial habitats. Stud. Avian Biol. 1990, 13, 144–160. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, B.J.; FitzGibbon, S.I.; Wilson, R.S. New urban developments that retain more remnant trees have greater bird diversity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 136, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, W.W. Energetics and thermoregulation by small passerines of the humid, lowland tropics. Auk 1997, 114, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, W.W.; Greene, E. Thermoregulatory responses of bridled and juniper titmice to high temperature. Condor 1998, 100, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, G.C.; Sharma, S.; Vishvakarma, S.C.; Samant, S.S.; Maikhuri, R.K.; Prasad, R.C.; Palni, L.M. Ecology and use of Lantana camara in India. Bot. Rev. 2019, 85, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L.G.; Plucknett, D.L.; Pancho, J.V.; Herberger, J.P. The World’s Worst Weeds; University Press: Honululu, HI, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Aravind, N.; Rao, D.; Ganeshaiah, K.; Uma Shaanker, R.; Poulsen, J.G. Impact of the invasive plant, Lantana camara, on bird assemblages at Malé Mahadeshwara Reserve Forest, South India. Trop. Ecol. 2010, 51, 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, C.J.; Norton, D.A.; Hobbs, R.J. Grazing effects on plant cover, soil and microclimate in fragmented woodlands in south-western Australia: Implications for restoration. Austral Ecol. 2000, 25, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, S.; McIntyre, S.; McIvor, J.; Heard, K.M. Managing & Conserving Grassy Woodlands; CSIRO publishing: Canberra, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vickery, P.D.; Herkert, J.R. Recent advances in grassland bird research: Where do we go from here? Auk 2001, 118, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterjohn, B.G.; Sauer, J.R. Population status of North American grassland birds from the North American breeding bird survey. Stud. Avian Biol. 1999, 19, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Species Code | N | Feeding Guild | Foraging Stratum | Preference for Shrub Forest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common Babbler | Argya caudata | CB | 18 | Omnivore | Ground | Specialist |

| Yellow-billed Babbler * | Argya affinis | YBB | 18 | Insectivore | Ground | Specialist |

| Yellow-eyed Babbler | Chrysomma sinense | YEB | 18 | Omnivore | Shrub | Specialist |

| Tawny-bellied Babbler | Dumetia hyperythra | TBB | 21 | Insectivore | Shrub | Specialist |

| Red-vented Bulbul | Pycnonotus cafer | RVB | 21 | Frugivore | Shrub | Generalist |

| Red-whiskered Bulbul | Pycnonotusjocosus | RWB | 24 | Frugivore | Tree | Generalist |

| White-browed Bulbul | Pycnonotusluteolus | WBB | 15 | Frugivore | Shrub | Specialist |

| Yellow-throated Bulbul * | Pycnonotus xantholaemus | YTB | 7 | Frugivore | Shrub | Specialist |

| Plain Prinia | Prinia inornata | PP | 19 | Insectivore | Shrub | Generalist |

| Jungle Prinia | Priniasylvatica | JP | 19 | Insectivore | Shrub | Specialist |

| Purple-rumped Sunbird | Leptocoma zeylonica | PRS | 18 | Nectarivore | Tree | Specialist |

| Purple Sunbird | Cinnyris asiaticus | PS | 16 | Nectarivore | Tree | Specialist |

| Laughing Dove | Spilopelia senegalensis | LD | 22 | Granivore | Ground | Specialist |

| Indian Robin | Saxicoloides fulicatus | IR | 15 | Insectivore | Ground | Specialist |

| Green Bee-eater | Merops orientalis | GBE | 10 | Insectivore | Tree | Specialist |

| Bay-backed Shrike | Lanius vittatus | BBS | 10 | Insectivore | Shrub | Specialist |

| Blyth’s Reed Warbler ** | Acrocephalus dumetorum | BRW | 20 | Insectivore | Shrub | Specialist |

| Sirkeer Malkoha | Taccocua leschenaultii | SM | 12 | Insectivore | Ground | Specialist |

| Vegetation Characteristic | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| % Rock Cover | 2.74 | <0.001 |

| Shrub Height | 3.58 | <0.001 |

| Diameter at Breast Height | 2.28 | 0.002 |

| Average Shrub Density | 3.27 | <0.001 |

| Average Ground Cover | 4.24 | <0.001 |

| Average Grass Height | 2.23 | 0.002 |

| Stem Evenness | 2.84 | <0.001 |

| Vertical Foliage Evenness | 1.78 | 0.02 |

| Horizontal Foliage Evenness | 3.85 | <0.001 |

| Canopy Height Evenness | 2.37 | 0.001 |

| Average Canopy Height | 1.741 | 0.03 |

| Grass Height Evenness | 1.611 | 0.05 |

| Average Dry Grass Cover | 2.11 | <0.01 |

| Linear Discriminants | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| % of Variation | 31.20 | 18.90 | 15.13 |

| Cumulative % of Variation | 31.20 | 50.10 | 65.23 |

| Variables | LD1 | LD2 | LD3 |

| % Rock Cover | 0.35 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| Shrub Height | −0.03 | 0.53 | −0.97 |

| Diameter Breast Height | 0.46 | −0.02 | 0.00 |

| Average Shrub Density | −0.43 | 0.67 | 0.38 |

| Average Ground Cover | 0.66 | −0.12 | −0.05 |

| Average Grass Height | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.16 |

| Stem Evenness | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.00 |

| Vertical Foliage Evenness | 0.16 | −0.60 | 0.20 |

| Horizontal Foliage Evenness | 0.24 | −0.42 | 0.24 |

| Canopy Height Evenness | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.14 |

| Average Canopy Height | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Grass Height Evenness | −0.10 | 0.02 | 0.41 |

| Average Dry Grass Cover | −0.01 | 0.16 | −0.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Deshwal, A.; Panwar, P.; Becker, B.M.; Stephenson, S.L. Foraging Habitat Selection of Shrubland Bird Community During the Dry Season in Tropical Dry Forests. Diversity 2026, 18, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010025

Deshwal A, Panwar P, Becker BM, Stephenson SL. Foraging Habitat Selection of Shrubland Bird Community During the Dry Season in Tropical Dry Forests. Diversity. 2026; 18(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeshwal, Anant, Pooja Panwar, Brian M. Becker, and Steven L. Stephenson. 2026. "Foraging Habitat Selection of Shrubland Bird Community During the Dry Season in Tropical Dry Forests" Diversity 18, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010025

APA StyleDeshwal, A., Panwar, P., Becker, B. M., & Stephenson, S. L. (2026). Foraging Habitat Selection of Shrubland Bird Community During the Dry Season in Tropical Dry Forests. Diversity, 18(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010025