Abstract

Climate warming is one of the most pressing global changes, with profound consequences for biodiversity, ecosystem functioning, and the provision of ecosystem services. Although warming is expected to alter soil nutrient cycling and plant community structure, the mechanisms through which it reshapes ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) remain insufficiently understood. Here, we conducted a 3-year field warming experiment in an alpine grassland to assess how warming influences plant diversity, soil nutrients, and their joint effects on EMF. We found that plant α-diversity declined in both control and warming groups in 2021 and partially recovered by 2023, though recovery was weaker under warming. In contrast, β-diversity (turnover) showed a continuous increasing trend under warming across years, although differences from the control were not statistically significant. EMF, evaluated with single- and multi-threshold approaches, exhibited a consistent decline, with warming accelerating this reduction and producing more complex bimodal fluctuations within intermediate threshold ranges (55–75% and 80–90%). Warming also restructured the functional drivers of EMF: soil organic carbon (SOC) and available nitrogen (AN) emerged as dominant regulators, whereas the contributions of total nitrogen and turnover weakened. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that warming not only alters biodiversity patterns and ecosystem functions but also reshapes the soil–plant–function feedbacks that sustain EMF. By identifying SOC and AN as critical mediators, this study highlights a mechanistic pathway through which climate warming may undermine ecosystem resilience and long-term sustainability, providing insights essential for predicting terrestrial ecosystem responses under future climate scenarios.

1. Introduction

Global climate warming is reshaping ecosystems worldwide, driving profound changes in biodiversity, community composition, and the delivery of ecosystem services [1,2]. One key scientific challenge is to understand how warming influences the ability of ecosystems to simultaneously sustain multiple ecological processes—a property referred to as ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF). EMF integrates diverse ecological functions, including primary productivity, nutrient cycling, carbon storage, and biodiversity maintenance, and is increasingly recognized as a unifying framework for evaluating ecosystem resilience and sustainability under global change [3,4]. Recent studies across a range of ecosystems have shown that EMF can be strongly shaped by biodiversity [5], soil physicochemical properties, and microbial communities [6], highlighting the need to identify the mechanisms and drivers that regulate multifunctionality under changing environments [7,8]. Despite this growing interest, substantial gaps remain. First, most existing work has emphasized long-term gradual warming processes [9,10], while the ecological impacts of short-term warming events—arguably more frequent under climate extremes—remain underexplored. Such short-term warming may trigger rapid shifts in community composition, plant growth, and soil nutrient cycling, thereby altering EMF in ways distinct from gradual warming [11]. Second, current research often treats multifunctionality as a descriptive measure of overall performance [12], without systematically assessing the relative contributions of individual functions to EMF [13,14]. Addressing these knowledge gaps is crucial for advancing both theoretical understanding and practical ecosystem management.

The Tibetan Plateau, often referred to as the “Roof of the World” and the “Water Tower of Asia,” provides an ideal natural laboratory to investigate these questions. As one of the most climate-sensitive regions globally [15], it has already experienced significant warming and associated ecological changes [2]. Previous studies in this region have focused primarily on the effects of warming on single ecosystem functions such as soil carbon emissions [16] or plant productivity [17], and only a few have examined EMF under long-term warming conditions [18,19]. However, the responses of EMF to short-term warming events, as well as the key ecological factors driving these responses, remain largely unknown. Clarifying these mechanisms in such a fragile ecosystem not only is of regional importance but also provides broader insights into how ecosystems worldwide may respond to rapid climate fluctuations, thereby offering critical guidance for biodiversity conservation and sustainable ecosystem management.

This study focuses on the response mechanisms of EMF under short-term warming conditions on the Tibetan Plateau, aiming to systematically address the following key scientific questions: (1) Does short-term warming significantly affect species diversity? (2) How does short-term warming affect the overall level of EMF and its relationship with ecosystem functions? (3) Under short-term warming conditions, do the contributions of different ecological functions (such as diversity, soil organic carbon (SOC), total nitrogen (TN), available nitrogen (AN), etc.) to multifunctionality change? Therefore, this study will rely on a field temperature control experiment platform, integrating multidimensional ecological data such as plant diversity and soil functional indicators, to comprehensively assess the pathways through which short-term warming affects EMF.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sampling

The warming experiment in this study was conducted in Bailang Village, Kazi Township, Lhasa City, China (29°59′ N, 91°17′ E, 3900 m) (Figure 1). The area has an average annual precipitation of 390.9 mm and a mean annual air temperature of 7.9 °C [20], with an average annual evaporation of about 1440 mm. The vegetation is dominated by Pennisetum centrasiaticum, Tripogon bromoides, Kobresia pygmaea, and Carex atrofusca [21]. This region is characterized by a typical plateau temperate semi-arid climate, with dry and cool conditions, abundant sunlight, long and cold winters, and short and cool summers [22].

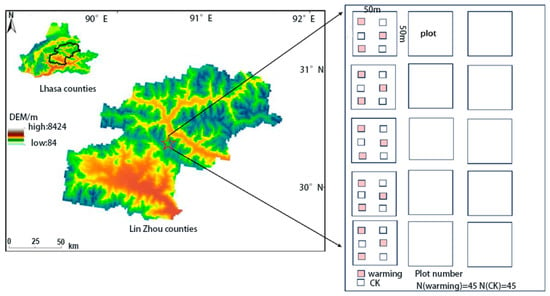

Figure 1.

Location of the study site and experimental design. “CK” indicates control plots without warming treatment. “N” indicates the number of plots.

2.2. Experimental Design

In 2010, we fenced the grassland in the study area for this research. The experiment started in 2020, with 15 fenced plots of equal size (50 m × 50 m) established within the fence. Each fence contained three warming treatment plots using Open Top Chambers (OTCs) [23] and three control plots (Figure 1). The structure of the OTCs was designed as a hexagonal prism, with a hexagonal cross-section. The top opening is smaller than the bottom opening, with a top diameter of 0.8 m and a bottom diameter of 1.2 m. The height of the structure is 0.5 m, and the light transmission rate can reach up to 90%. The OTC walls were made of transparent polycarbonate plates (5 mm thickness), which are commonly used in passive warming experiments due to their high light transmittance and durability. Vegetation and soil sampling for this study was conducted from July to September 2020, with 2020 as the starting year. Additional sampling was conducted in July to September of 2021 and 2023 for the second and third sampling events. According to regional meteorological reports for the Tibetan Plateau, the year 2021 experienced unusually low temperatures and reduced precipitation during the growing season, whereas conditions in 2023 were closer to the long-term average. In each subplot, a 50 cm × 50 cm frame was set up at the center to non-destructively investigate plant species composition, species abundance, species diversity, and plant cover. To determine aboveground biomass (AGB), we harvested all standing vegetation from an adjacent 25 cm × 25 cm quadrat that was randomly located within each subplot in each sampling year, dried the material in an oven at 80 °C for 48 h, and then weighed it. In total, 15 fenced plots were established, each containing three warming and three control subplots, resulting in 45 subplots per treatment. Vegetation surveys were conducted in all subplots in 2020, 2021, and 2023, yielding 45 plot-year observations per treatment (n = 45) used in the diversity and EMF analyses. Soil samples were collected once per year from each subplot in September, resulting in the same number of soil samples per treatment and year. The soil samples were sieved through a 2 mm mesh and then analyzed for soil parameters, including physical and chemical properties and major nutrient components.

2.3. Ecosystem Function and Multifunctionality Assessment

For the single-threshold approach, we first standardized each function to its observed maximum value and, for each fixed threshold (T), expressed as a percentage of the maximum observed value, counted the number of functions in each plot that exceeded T. Separate regressions were then fitted for each fixed threshold. Here, ‘percent of maximum’ refers to the threshold expressed as a percentage of the maximum observed value of each ecosystem function across all plots and years. Thus, a given function is considered achieved in a plot only when its value exceeds the specified percentage of its global maximum. EMF was defined as this count [24]. For the multi-threshold approach, we repeated this procedure across a series of thresholds ranging from 10% to 90% of the maximum and evaluated how the slope of the relationship between diversity and EMF varied along this gradient [25]. For the averaging approach, we standardized all nine functions using min–max normalization and then calculated EMF as the arithmetic mean of the standardized functions for each plot [26]. We considered nine ecosystem functions related to productivity, soil nutrient cycling, and biodiversity: aboveground biomass (AGB), soil organic carbon (SOC), soil total nitrogen (TN), soil available nitrogen (AN), soil available phosphorus (AP), soil pH, α-diversity (Shannon index), species richness index, and β-diversity (turnover). Among these functions, SOC, TN, AN, AP, and pH were used as proxies for soil carbon and nutrient cycling functions, and were incorporated into the calculation of EMF rather than analyzed as stand-alone response variables. All calculations were performed in R (version 4.4.1) using the “multifunc” package (version 0.10.0).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We calculated species diversity, including the Shannon-Wiener diversity index () [27] and the Margalef species richness index () [28], and β-diversity(turnover) is calculated in pairs for each plot between 2020 and 2021 and between 2021 and 2023 [29], using the following formulas:

S represents the number of species in the sample plot; N denotes the total number of individuals across all species in each quadrat; i refers to the ith species in the quadrat; and Pi is the relative importance value of the ith species.

a is the number of species shared sampling of the same plot in different years. b represents the number of species unique to sample 1. c indicates the number of species unique to sample 2.

Firstly, we compared the observed (calculated) values of α-diversity (Shannon index), species richness index, and β-diversity (turnover) between the control and warming groups across years. Next, for Mantel tests, Euclidean distance matrices were calculated among plots for EMF and for each individual function (plot-by-plot distances based on raw values), and Mantel r was computed between the EMF matrix and each function matrix. In addition, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to describe pairwise linear relationships among individual ecosystem functions and between EMF and single functions for visualization and interpretation. We used the “glmm.hp” (version 0.2.2) package in R (version 4.4.1) to perform hierarchical partitioning. The relative importance of each ecosystem function was calculated as the independent contribution of that predictor divided by the sum of independent contributions across all predictors and expressed as a percentage. We selected hierarchical partitioning because many of the candidate predictors, particularly soil physicochemical properties such as SOC, TN, AN, and AP, are inherently intercorrelated, leading to multicollinearity in conventional regression models. Such multicollinearity can bias parameter estimates and obscure the true relative importance of individual predictors. The “glmm.hp” (version 0.2.2) package implements hierarchical partitioning, which decomposes the total explained variance into components uniquely attributable to each predictor and components shared among correlated predictors. By quantifying the independent contribution of each driver to EMF, this approach allowed us to robustly resolve the relative importance of soil nutrients and diversity metrics and to test whether warming shifts the system from a diffuse, multifactor control of multifunctionality to a more concentrated control by a few key factors. Finally, we used general linear models (GLMs) to examine the relationship between ecosystem functions and both ecosystem functions and EMF. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to compare the differences in ecosystem function indicators across diversity indices. Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed to check for significant differences (p < 0.05), and the “ggplot2” (version 3.4.4) package in R (version 4.4.1) was used for data visualization [30]. All analyses were based on 45 sample plot observations per treatment (n = 45).

3. Results

3.1. The Effect of Warming on the Diversity of Alpine Grasslands

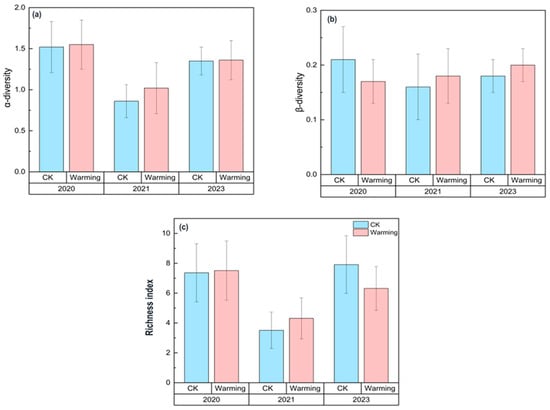

The α-diversity showed no significant differences between the CK and the warming treatment (Figure 2). However, both groups experienced a noticeable decline in 2021. Although there was some increase in 2023, the diversity levels did not return to the initial levels of 2020. After a significant decrease in 2021, the Richness index showed a more noticeable recovery trend in the CK, while the warming group exhibited a relatively limited recovery (Figure 2). The β-diversity (turnover) analysis revealed that, during the three-year experiment, the CK showed a slight decline followed by a gradual increase, while the warming group showed a continuous upward trend in β-diversity, whereas the CK exhibited a decline followed by recovery (Figure 2). Notably, during the periods from 2020 to 2021 and from 2021 to 2023, the β-diversity of the warming group showed higher mean values than that of the CK, although the differences were not statistically significant (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in the α-diversity, richness index, and β-diversity under control (CK) and warming conditions in 2020, 2021, and 2023. (a) α-diversity (Shannon index); (b) β-diversity (turnover); (c) richness index. The blue bars represent the control group, and the pink bars represent the warming group. Each bar is accompanied by error bars, indicating the standard error (SE).

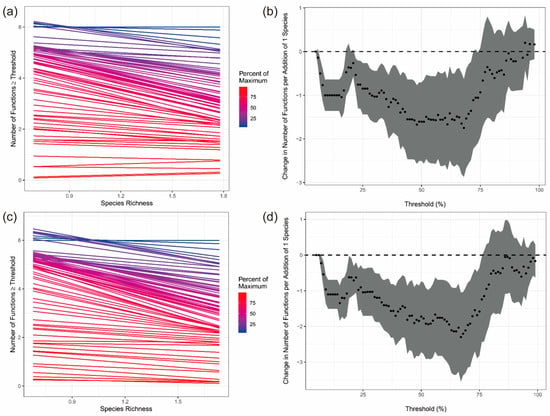

3.2. The Relationship Between Ecosystem Multifunctionality and Diversity

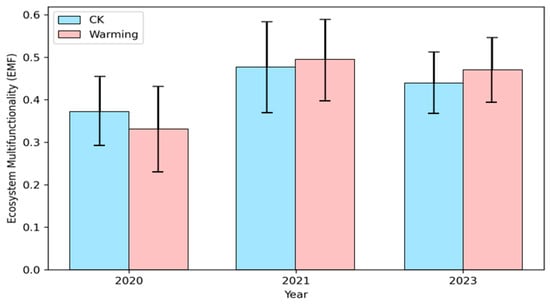

The single-threshold analysis showed that the number of functions exceeding the threshold generally decreased with lower species richness in both treatments (Figure 3a,c). This negative relationship was stronger under warming treatment, indicating that multifunctionality was more sensitive to species loss when temperature increased. The multi-threshold analysis further revealed that the diversity–multifunctionality relationship depended strongly on the threshold level (Figure 3b,d). At low thresholds, slopes were close to zero, meaning most functions easily met the threshold regardless of diversity. At intermediate thresholds (around 50–70%), slopes were most negative, showing that biodiversity had its strongest effect on sustaining multifunctionality. At high thresholds (>80%), slopes increased again, forming a clear bimodal pattern. This bimodal pattern was more pronounced under warming, suggesting that warming enhances the threshold sensitivity of multifunctionality and reduces functional stability at medium–high performance levels. The mean-based analysis of nine ecosystem function indicators showed that mean EMF increased from 2020 to 2021 and declined slightly in 2023 in both treatments. Although warming tended to show higher mean EMF values in 2021 and 2023, the overlap of SD bars indicates that warming did not result in a statistically significant difference in average EMF (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Effects of plant diversity on ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) under control (CK) and warming treatments. Panels (a) and (c) show single-threshold relationships between species richness and the number of functions exceeding fixed thresholds (10–90% of the maximum) under CK and warming, respectively. Panels (b) and (d) show threshold-dependent diversity effects (slopes) under CK and warming, respectively. Points indicate slope estimates, shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals, and the dashed line denotes zero effect. Sample size: n = 45.

Figure 4.

The time-related variation in ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) based on the average values of 9 ecosystem function indicators. Blue represents the control group (CK); purple represents warming treatment (Warming). Each bar is accompanied by error bars, indicating the standard deviation (SD).

3.3. The Effect of Warming on the Relationship Between Single Ecosystem Function and Ecosystem Multifunctionality

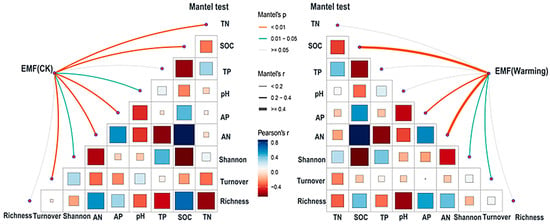

In the control group, the significant correlations between EMF and soil factors as well as plant diversity indices were mainly observed in key factors such as total nitrogen, soil organic carbon, available phosphorus, available nitrogen, and plant species turnover (Figure 5). In contrast, in the warming group, the correlation between EMF and soil organic carbon, available nitrogen was further strengthened (p < 0.01), while the relationship between total nitrogen and EMF shifted from significant (p < 0.01) to non-significant (p ≥ 0.05). Additionally, the positive correlation between turnover and EMF also weakened, with the significance level decreasing from p < 0.01 to 0.01< p < 0.05 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) of warming and control affected by the changes in soil nutrients and plant diversity. The color of the connecting lines represents Mantel test p-values (orange, p < 0.01; green,0.01 ≤ p < 0.05; gray, p ≥ 0.05), and line thickness indicates the magnitude of Mantel’s r (thicker lines denote stronger correlations). Node color (from dark blue to red) represents the Pearson correlation coefficient between each factor and EMF, with blue indicating negative and red indicating positive correlations. The sample size is 45, and EMF was calculated using the averaging approach.

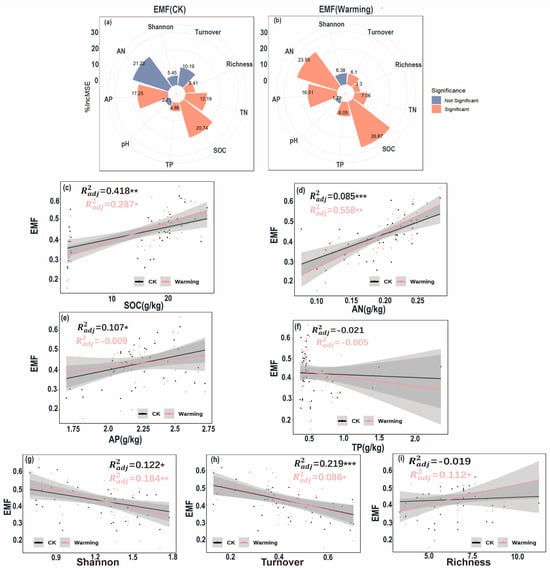

3.4. Key Ecosystem Functions Driving Ecosystem Multifunctionality Changes

In the control group, available nitrogen, available phosphorus, and soil organic carbon were the three most influential factors on EMF, with relative importance values of 21.22%, 17.25%, and 20.74%, respectively (Figure 6a), with available phosphorus and soil organic carbon showing significant driving effects. In contrast, in the warming group, this driving pattern changed significantly: the importance of available nitrogen, increased to 23.95%, becoming a significant driving factor, while the influence of soil organic carbon also significantly increased to 26.87% (Figure 6b), and both factors jointly became the most critical drivers of EMF. After warming treatment, the driving effects of various physicochemical factors on EMF generally increased, whereas the driving effects the control group were relatively weak and the factors were more widely distributed (Figure 6a,b). Further analysis revealed that under different treatment conditions, EMF showed significant positive linear correlations with soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, and available nitrogen (p < 0.01; Figure 6c–f). EMF exhibited a significant negative linear relationship with α-diversity (p < 0.01; Figure 6g), but no significant correlation with β-diversity (p > 0.05; Figure 6h). All significant relationships in the warming group showed higher coefficients of determination (R2), indicating that their correlation strengths were generally stronger than those the control group.

Figure 6.

The importance and significance of ecosystem functions on changes in ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) under control conditions (a) and warming conditions (b), and the relationships between ecosystem function indicators (c–i) and ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) under control and warming conditions, with orange representing the warming group and blue representing the control group. EMF was calculated using the averaging approach. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Warming on the Diversity and Community Structure of Alpine Grasslands

The impact of warming on grassland ecosystems exhibits significant temporal heterogeneity, particularly in terms of species diversity and community structure, which are especially complex. Studies show that there were no significant differences in α-diversity between the control group and the warming group, which may be attributed to the buffering effect of alpine ecosystems against short-term warming [31]. This result is consistent with existing research [32], which indicates that short-term warming often fails to surpass the stability threshold of an ecosystem, leading to no significant changes in α-diversity. Notably, in 2021, both groups showed a significant decline in α-diversity, which we hypothesize is closely related to extreme climate anomalies characterized by unusually low temperatures and reduced precipitation on the Tibetan Plateau in that year [33]. By 2023, although α-diversity in both groups had recovered, it remained significantly lower than the baseline level of 2020, revealing that the recovery process of alpine ecosystems after damage is characterized by a clear lag and incompleteness [34]. This delayed recovery may result from multiple mechanisms: the reorganization of interspecies competition that has led to a new niche structure and the long-term characteristics of community succession, among others [8].

As for the plant species richness, the sharp decline in 2021 is likely causally linked to a regional cold and dry period, with extreme low temperatures and markedly reduced precipitation [33]. In 2023, the control group exhibited a strong recovery capacity, while the warming group’s recovery was significantly constrained. This difference suggests that sustained warming, by intensifying environmental stress (such as soil drought [9] and nutrient imbalance [35]), may have surpassed the ecological adaptation threshold of certain species, thereby inhibiting the natural recovery process of the community. Although our three sampling years captured the pre-disturbance baseline (2020), the immediate decline (2021), and the partial recovery (2023), the lack of observations in 2022 prevents us from resolving the exact shape of the recovery trajectory (e.g., whether it was rapid and linear or delayed and asymptotic). A key limitation of our study is the lack of observations in 2022, which prevents us from reconstructing the full recovery trajectory. Therefore, our conclusion that warming constrained the recovery of species richness refers specifically to the constrained end-state in 2023 rather than to the entire recovery pathway.

Regarding community structure, the changes in β-diversity clearly show treatment differences: the warming group exhibited a continuous upward trend in β-diversity. Although this pattern suggests a potential effect of warming on species reorganization, the differences between treatments were not statistically significant, and thus this interpretation should be treated with caution [36]. Meanwhile, the control group showed a “V”-shape pattern—an initial decline caused by extreme weather events in 2021 [33], followed by a recovery—reflecting the resilience of the natural ecosystem [10]. These findings collectively suggest that climate warming not only directly affects the survival and adaptability of alpine meadow species, but also reshapes the ecosystem’s heterogeneity and dynamic evolutionary trajectory across multiple spatiotemporal scales by altering community construction mechanisms.

4.2. The Impact of Warming on Ecosystem Multifunctionality

Warming has led to a decline in EMF, but this change exhibits significant phase-dependent and threshold effects, with the impact on EMF showing phase fluctuations. Through the analysis results from the single-threshold method and the multi-threshold method, it is evident that the warming has a clear difference in its effect mechanisms on EMF and species diversity across different threshold intervals. Firstly, the analysis using the single-threshold method shows that under warming conditions, EMF exhibits a significant downward trend, and the magnitude of this decline is notably greater than that of the control group. This result suggests that increased temperature may have a negative impact on ecosystem functions. Warming, by intensifying climate change pressure [7], has led to the deterioration of growth, survival, and reproduction conditions for certain species [37], especially those adapted to lower temperatures, limiting their functional performance [38]. Furthermore, warming may alter the competitive relationships between species [39], with some species gradually disappearing due to their inability to adapt to the new environment, thereby reducing the stability and diversity of ecosystem functions [40]. Secondly, the analysis using the multi-threshold method reveals a negative correlation between EMF and species diversity. In the multi-threshold analysis, the diversity–multifunctionality effect curves displayed a bimodal pattern, with two distinct ranges (55–75% and 80–90% thresholds) where the slope of the relationship between diversity and the number of functions exceeding the threshold changed direction. Intermediate thresholds around 55–75% correspond to moderate performance levels of most functions, whereas very high thresholds (80–90%) reflect the capacity of a subset of functions to reach near-maximal values. The enhanced fluctuations of diversity effects within these ranges under warming suggest that medium-to-high multifunctionality states are particularly sensitive to temperature-induced shifts in species composition and soil processes, consistent with a nonlinear ecosystem response to warming. In the early stages of the ecosystem, warming may have initially promoted the growth and reproduction of certain species, temporarily enhancing multifunctionality [41]. However, as temperature continues to rise and the ecosystem gradually adapts, increased competition between species and the growth limitations of some species may lead to a subsequent decline in ecosystem functions [42]. In the warming group, a slight downward trend observed particularly in the 55–75% and 80–90% threshold intervals may be due to disturbances in ecosystem stability brought about by temperature changes within these specific threshold ranges. Small fluctuations in temperature could cause imbalances in species composition and ecosystem functions, leading to more complex dynamic changes [43].

4.3. The Relationship Between Ecosystem Function and Ecosystem Multifunctionality

Warming has significantly altered the structure and effect intensity of the main driving factors of EMF, highlighting the importance of soil physicochemical properties in regulating ecosystem functions under climate change [44]. It is important to note that the Mantel test and hierarchical partitioning provide complementary information. The Mantel r values quantify the overall coupling strength between EMF and each ecosystem factor, whereas the hierarchical partitioning scores represent the unique variance in EMF independently explained by each predictor. Under the warming conditions, both the Mantel correlations and the independent relative importance of SOC and AN increased (Figure 5 and Figure 6a,b), indicating that these variables not only became more tightly coupled to EMF, but also exerted stronger mechanistic control over multifunctionality. This joint strengthening of coupling and control underpins our conclusion that warming restructures the driver network from a diffuse, multifactor regime to one dominated by a small set of key soil properties. The results show that in the control group, AN, AP, and SOC are the primary factors influencing EMF, but their driving effects on EMF are relatively balanced and the driving mechanisms are relatively loose. Under the warming conditions, this pattern changes significantly, with AN importance increasing to 23.95% and the influence of SOC rising to 26.87%, both becoming significant driving factors for changes in EMF. This significant change is likely closely related to the profound impact of warming on soil physicochemical properties [45]. Firstly, an increase in temperature accelerates the decomposition of soil organic carbon, enhancing its activity and thereby increasing the rates of changes in carbon and nitrogen [46]. Under the warming conditions, the synergistic enhancement of functions such as organic carbon degradation, nitrogen cycling, and phosphorus transformation promotes an overall increase in EMF [47]. The enhanced significance of available nitrogen also indicates that warming promotes the release and transformation of nitrogen, likely through enhanced soil physicochemical properties that improve nitrogen absorption and assimilation, thereby enhancing functions related to nitrogen metabolism [48]. Although AP did not become the most significant factor in the warming group, it still maintained a positive impact on EMF, which may be due to the relatively complex mechanism by which warming affects phosphorus, regulated by factors such as soil pH, moisture conditions, and organic acid release [49]. Moreover, in the control group, EMF was correlated with several factors, but due to the relatively stable environment and low soil nutrient release rate, the driving mechanisms of EMF were weakly correlated and dispersed. Under the warming conditions, the coupling relationship between physicochemical factors and EMF became stronger, indicating that the system’s feedback mechanisms were more sensitive and concentrated. EMF showed significant positive linear relationships with SOC, AN, and AP (p < 0.01), indicating that these key soil nutrients play a central role in maintaining ecosystem functional diversity and promoting the coordination of ecological processes [50]. At the same time, EMF showed a significant negative correlation with α-diversity, EMF was strongly and positively associated with SOC, TN, and especially AN (Figure 6c–f), indicating that plots with high multifunctionality tended to exhibit accelerated nutrient cycling and higher productivity. Under the warming conditions, increased nitrogen availability is likely to favor fast-growing, nitrophilous species that can rapidly exploit enhanced resource fluxes. Such a selection effect allows a few functionally specialized and highly productive species to dominate ecosystem processes and drive high EMF, while simultaneously suppressing the coexistence of other species through intensified competition, which may reflect that, as functionality increases, plant communities tend to converge in function [38], with some functionally dominant species leading the ecological processes and suppressing overall community diversity. This phenomenon is more common when resource supply is abundant or environmental selection pressures are enhanced [51]. Therefore, our results suggest that warming significantly strengthens the coupling relationship between soil nutrients and EMF, shifting the driving mechanism from “multifactor dispersion” to “key factor concentration,” especially highlighting the important regulatory role of SOC and AN in maintaining EMF under the warming conditions. The diversity of β-diversity increases significantly under the warming conditions, but its relationship with EMF is still not significant, further confirming this conclusion. The increase in β-diversity mainly reflects species replacement rather than functional changes. The functional contributions of many species acquired or lost under warming are relatively weak, resulting in limited impact on EMF. In addition, warming enhances the dependence of EMF on soil properties (SOC and AN), while weakening the impact of turnover, indicating a shift from diversity driven to soil driven multifunctionality.

5. Conclusions

Warming significantly reshaped the relationship between plant diversity and EMF, along with its underlying drivers. Over three years, α-diversity declined in both groups, with slower recovery under the warming conditions, while β-diversity increased persistently in the warmed plots. EMF decreased in both groups but exhibited greater volatility under warming, showing a bimodal pattern in multi-threshold analysis. Soil properties, particularly soil organic carbon and available nitrogen, emerged as dominant drivers of EMF in warmed plots, whereas total nitrogen and turnover rate weakened in influence. Notably, EMF correlated positively with soil organic carbon, available phosphorus, and available nitrogen but negatively with α-diversity, with no significant link to β-diversity. These findings highlight a shift in ecosystem regulation under the warming conditions—from dispersed drivers (e.g., total nitrogen, Turnover) to concentrated control by soil organic carbon and available nitrogen—underscoring the sensitivity of functional pathways to climate change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C. and J.W. (Junxi Wu); methodology, J.C. and M.X.; formal analysis, J.C.; data curation, J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C., J.W. (Junye Wu) and C.L.; writing—review and editing, J.C., J.W. (Junxi Wu), Z.K., M.X., Y.Z., Z.W., F.S., J.W. (Junye Wu), X.D. and C.L.; visualization, J.C.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Application and Fundamental Research Project of Qinghai Province (2023-ZJ-766).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zekai Kong was employed by the company Cabio Synbio Technology (Wuhan) Company Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, S.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Xu, K.L.; Zhang, J.L. Impact of Climate Change on Alpine Phenology over the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau from 1981 to 2020. Forests 2023, 14, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.K.; Chen, H.; Levy, J.K. Spatiotemporal vegetation cover variations in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau under global climate change. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2008, 53, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, P.; van der Plas, F.; Soliveres, S.; Allan, E.; Maestre, F.T.; Mace, G.; Whittingham, M.J.; Fischer, M. Redefining ecosystem multifunctionality. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, D. Research progress on urban forest ecosystem services and multifunctionality. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 11557–11566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X.; Hu, D.; Wang, H.F.; Jiang, L.M.; Lv, G.H. Scale Effects on the Relationship between Plant Diversity and Ecosystem Multifunctionality in Arid Desert Areas. Forests 2022, 13, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, D.; Chen, X.L.; Hou, J.F.; Zhao, F.C.; Li, P. Soil properties and microbial functional attributes drive the response of soil multifunctionality to long-term fertilization management. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 192, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.P.; Niu, H.L.; Zhang, S.P.; Chen, X.Z.; Xia, X.S.; Zhang, Y.W.; Lu, X.J.; He, B.; Wu, T.W.; Song, C.Q.; et al. Higher warming rate in global arid regions driven by decreased ecosystem latent heat under rising vapor pressure deficit from 1981 to 2022. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 371, 110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Yu, C.Q.; Fu, G. Warming reconstructs the elevation distributions of aboveground net primary production, plant species and phylogenetic diversity in alpine grasslands. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Qin, R.M.; Zhang, S.X.; Yang, X.Y.; Xu, M.H. Effects of long-term warming on the aboveground biomass and species diversity in an alpine meadow on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau of China. J. Arid Land 2020, 12, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H.; Willis, C.G.; Klein, J.A.; Ma, Z.; Li, J.Y.; Zhou, H.K.; Zhao, X.Q. Recovery of plant species diversity during long-term experimental warming of a species-rich alpine meadow community on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 213, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Dong, S.K.; Gao, Q.Z.; Zhou, H.K.; Liu, S.L.; Su, X.K.; Li, Y.Y. Effects of short-term and long-term warming on soil nutrients, microbial biomass and enzyme activities in an alpine meadow on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 76, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Lei, X.D.; He, X.; Gao, W.Q.; Guo, H. Multiple mechanisms drive biodiversity-ecosystem service multifunctionality but the dominant one depends on the level of multifunctionality for natural forests in northeast China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 542, 121101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölting, L.; Jacobs, S.; Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Maes, J.; Norström, A.; Plieninger, T.; Cord, A.F. Measuring ecosystem multifunctionality across scales. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 124083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, H.B.; Lai, J.D.; Zhang, R. Effects of Biodiversity and Its Interactions on Ecosystem Multifunctionality. Forests 2024, 15, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, W. Spatiotemporal Distribution and Influencing Factors of Ecosystem Vulnerability on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.K.; Wang, X.; Yang, G.H.; Han, X.H.; Zhu, L.; Liu, R.T. Short-term warming-induced increase in non-microbial carbon emissions from semiarid abandoned farmland soils. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 47, e02676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.X.; Zhang, Y.D.; Huang, M.; Tao, B.; Guo, R.; Yan, C.R. Effects of climate warming on net primary productivity in China during 1961–2010. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 6736–6746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.J.; Zhou, H.K.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.W.; Li, Y.Z.; Qiao, L.L.; Chen, K.L.; Liu, G.B.; Ritsema, C.; et al. Long-term warming impacts grassland ecosystem function: Role of diversity loss in conditionally rare bacterial taxa. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinfuku, M.S.; Domeignoz-Horta, L.A.; Choudoir, M.J.; Frey, S.D.; Mitchell, M.F.; Ranjan, R.; Deangelis, K.M. Seasonal effects of long-term warming on ecosystem function and bacterial diversity. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.L.; Li, F.F.; Gong, T.L.; Gao, Y.H.; Li, J.F.; Qiu, J. Reasons behind seasonal and monthly precipitation variability in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and its surrounding areas during 1979∼2017. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.X.; Wu, J.X.; Wu, J.J.; Guo, Y.J.; Lha, D.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, X.Z. Heavy Grazing Altered the Biodiversity-Productivity Relationship of Alpine Grasslands in Lhasa River Valley, Tibet. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 698707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.R.; Guo, L.L.; He, B.; Lyu, Y.L.; Li, T.W. The stability of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau ecosystem to climate change. Phys. Chem. Earth 2020, 115, 102827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Sun, W.; Yu, C.Q.; Zhang, X.Z.; Shen, Z.X.; Li, Y.L.; Yang, P.W.; Zhou, N. Clipping alters the response of biomass production to experimental warming: A case study in an alpine meadow on the Tibetan Plateau, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2015, 12, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.L.; Ding, J.; Li, C.Y.; Yan, Z.Z.; He, J.Z.; Hu, H.W. Microbial functional attributes, rather than taxonomic attributes, drive top soil respiration, nitrification and denitrification processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 139479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.L.; Ding, J.; Zhu, D.; Hu, H.W.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Ma, Y.B.; He, J.Z.; Zhu, Y.G. Rare microbial taxa as the major drivers of ecosystem multifunctionality in long-term fertilized soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 141, 107686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Lee, T.M. Altitude dependence of alpine grassland ecosystem multifunctionality across the Tibetan Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, S.H. Species-diversity measurement—Choosing the right index. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1991, 6, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y. Generalized Species Richness Indices for Diversity. Entropy 2022, 24, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastazini, V.A.G.; Galiana, N.; Hillebrand, H.; Estiarte, M.; Ogaya, R.; Peñuelas, J.; Sommer, U.; Montoya, J.M. The impact of climate warming on species diversity across scales: Lessons from experimental meta-ecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2021, 30, 1545–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrnes, J.E.K.; Gamfeldt, L.; Isbell, F.; Lefcheck, J.S.; Griffin, J.N.; Hector, A.; Cardinale, B.J.; Hooper, D.U.; Dee, L.E.; Duffy, J.E. Investigating the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem multifunctionality: Challenges and solutions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.B.; Sun, H.B.; Peng, F.; Zhang, H.Y.; Xue, X.; Gibbons, S.M.; Gilbert, J.A.; Chu, H.Y. Characterizing changes in soil bacterial community structure in response to short-term warming. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 89, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.F.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.M.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.J.; Wang, L.F.; Chen, Q.M. Short-term warming shifts microbial nutrient limitation without changing the bacterial community structure in an alpine timberline of the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Geoderma 2020, 360, 113985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Wang, G.F. Assessment of the hazard of extreme low-temperature events over China in 2021. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2022, 13, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.S.; Yu, C.Q.; Fu, G. Asymmetric warming among elevations may homogenize plant α-diversity and aboveground net primary production of alpine grasslands. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1126651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.; Liang, H.F.; Guo, S.Q.; Fan, Z.H.; Li, H.B.; Ma, M.S.; Zhang, S.Q. Adaptive regulation of microbial community characteristics in response to nutrient limitations under mulching practices across distinct climate zones. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 248, 106465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.B.; Wu, S.; Yang, L.B.; Liu, Y.Z.; Gao, M.L.; Ni, H.W. Short-Term Simulated Warming Changes the Beta Diversity of Bacteria in Taiga Forests’ Permafrost by Altering the Composition of Dominant Bacterial Phyla. Forests 2024, 15, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, I.; Svenning, J.C.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Balslev, H. Effects of Warming and Drought on the Vegetation and Plant Diversity in the Amazon Basin. Bot. Rev. 2015, 81, 42–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.X.; Yang, W.; Tian, L.H.; Qu, G.P.; Wu, G.L. Warming differentially affects above- and belowground ecosystem functioning of the semi-arid alpine grasslands. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 170061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektas, B.; Thuiller, W.; Saillard, A.; Choler, P.; Renaud, J.; Colace, M.P.; Della Vedova, R.; Münkemüller, T. Lags in phenological acclimation of mountain grasslands after recent warming. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 3396–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, P.B.; Bridgham, S.D.; Pfeifer-Meister, L.E.; DeMarche, M.L.; Johnson, B.R.; Roy, B.A.; Bailes, G.T.; Nelson, A.A.; Morris, W.F.; Doak, D.F. Climate warming threatens the persistence of a community of disturbance-adapted native annual plants. Ecology 2021, 102, e03464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antiqueira, P.A.P.; Petchey, O.L.; Romero, G.Q. Warming and top predator loss drive ecosystem multifunctionality. Ecol. Lett. 2018, 21, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.L.; Cheng, Z.; Alatalo, J.M.; Zhao, J.X.; Liu, Y. Climate Warming Consistently Reduces Grassland Ecosystem Productivity. Earths Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossena, M.; Yvon-Durocher, G.; Grey, J.; Montoya, J.M.; Perkins, D.M.; Trimmer, M.; Woodward, G. Warming alters community size structure and ecosystem functioning. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2012, 279, 3011–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.; Ma, Q.H.; Liu, X.D.; Xu, Z.Z.; Zhou, G.S.; Shi, Y.H. Short- and long-term warming alters soil microbial community and relates to soil traits. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 131, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.P.; Ding, M.J.; Zhang, H.; Zou, T.; Huang, P.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zeng, H.; Xiong, J.X.; Cheng, L.Y.; et al. Thresholds for the relationships between soil trace elements and ecosystem multifunctionality in degraded alpine meadows. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 391, 109743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.X.; Ouyang, Z.; Maxim, D.; Wilson, G.; Kuzyakov, Y. Lasting effect of soil warming on organic matter decomposition depends on tillage practices. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 95, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.T.; Liang, J.Y.; Hale, L.E.; Jung, C.G.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J.Z.; Xu, M.G.; Yuan, M.T.; Wu, L.Y.; Bracho, R.; et al. Enhanced decomposition of stable soil organic carbon and microbial catabolic potentials by long-term field warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 4765–4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, C.M.; Latimer, J.; Brice, D.J.; Childs, J.; Vander Stel, H.M.; Defrenne, C.E.; Graham, J.; Griffiths, N.A.; Malhotra, A.; Norby, R.J.; et al. Whole-Ecosystem Warming Increases Plant-Available Nitrogen and Phosphorus in an Ombrotrophic Bog. Ecosystems 2023, 26, 86–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.W.; Zhang, T.; Guo, J.X. Warming and nitrogen deposition accelerate soil phosphorus cycling in a temperate meadow ecosystem. Soil Res. 2020, 58, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, C.; Bender, S.F.; Widmer, F.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Soil biodiversity and soil community composition determine ecosystem multifunctionality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5266–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traill, L.W.; Lim, M.L.M.; Sodhi, N.S.; Bradshaw, C.J.A. Mechanisms driving change: Altered species interactions and ecosystem function through global warming. J. Anim. Ecol. 2010, 79, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.