Abstract

Islands subjected to anthropogenic disturbance are highly susceptible to alien plant invasions. However, the alien floral diversity of China’s islands has been insufficiently studied, hindering its control. Weizhou Island (northern South China Sea) has experienced long-term human exploitation. We inventorized its alien, naturalized, and invasive vascular plants (based on herbarium specimen data for 2018–2024 and surveys of 112 plots); analyzed species composition, origins, life forms, and habitats; and conducted an invasive species risk assessment. This identified 203 aliens, including infraspecific and hybrid taxa, 129 (63.5%) naturalized and 71 (55.0% of the naturalized species) invasive. The aliens were dominated by the Fabaceae, Asteraceae, and Euphorbiaceae, particularly genera such as Euphorbia, Senna, and Portulaca, originating primarily in North America, Oceania, and Africa. Perennial herbs were the most common lifeform, followed by annual herbs and shrubs. Invasion hotspots were primarily abandoned farmland, roadsides, and agricultural lands. Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process, we classified the 71 invasive species as representing high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk (20, 16, and 35 species, respectively). Bidens pilosa, Ageratum conyzoides, Opuntia dillenii, and Leucaena leucocephala pose severe threats to the island ecosystem. This first complete inventory of the alien flora on Weizhou Island offers critical insight into the management of invasive alien plants in island ecosystems.

1. Introduction

A hallmark of the Anthropocene is the escalating threat of human-mediated biological invasions to global biodiversity, economies, and public health [1,2,3]. The latest assessment of invasive alien species has revealed that over 37,000 introduced species have established populations worldwide, including more than 3500 invasive species [4]. Globally, at least 13,939 plant species (representing 3.9% of the extant vascular flora) have naturalized beyond their native ranges [5,6]; of these, approximately 2500 are considered invasive [7]. Although most introduced species fail to establish self-sustaining populations in the wild, a significant proportion successfully naturalize as their populations grow [8]. Detailed inventories of occurrence records are essential for managing problematic alien species [2,9].

Invasive species constitute a subset of naturalized species, which are in turn a subset of aliens [10]. Elucidating the relationships among these three groups is critical for predicting and preventing biological invasion. Naturalization occurs when intentionally or unintentionally introduced aliens overcome abiotic and biotic barriers to their survival and reproduction [11]. Naturalized plants may become invasive only when they produce sufficiently reproductive offspring in their new habitats [1]. Compiling complete inventories of naturalized species for specific countries or regions, along with comparative studies of regional naturalized flora, is an effective way to elucidate plant invasion patterns and a primary step in developing invasive species management strategies [5,9]. Over the past decade, the global distribution data of alien, naturalized, and invasive species across various taxonomic groups has been progressively refined [5,12,13,14,15]. For instance, Spampinato et al. [16] documented 382 alien plant species in Calabria (Southern Italy), including 127 naturalized and 48 invasive species. Iran hosts 311 alien vascular plants, of which 167 are naturalized and 13 are invasive [17], whereas Pakistan has 400 alien taxa, of which 117 are naturalized and 103 are invasive [18]. Complete inventories of alien plants are essential for addressing key questions in invasion biology and conducting risk assessment [15]. Comprehensive documentation of alien, naturalized, and invasive plants at national or regional scales provides vital data for comparative studies of alien flora, yielding novel insights into the global patterns and dynamics of plant invasions.

Islands serve as ideal natural laboratories for studying biological evolution, ecology, and climate change. Their unique environmental characteristics foster distinct biotic assemblages, while presenting substantial challenges to survival [19,20]. Global urbanization efforts and expanding tourism and trade in island territories [21], coupled with heightened vulnerability to typhoons, storm surges, and other natural disasters, have compromised the limited self-regulatory capacity of island ecosystems. This has precipitated environmental degradation and the loss of biodiversity [22]. The inherent fragility of island ecosystems renders them particularly susceptible to native species displacement and ecosystem service deterioration following alien species introductions [19,20,23]. These perturbations often result in the phenomenon known as “biotic homogenization”, which involves taxonomic and functional simplification [2,6,24]. Islands experience disproportionately worse impacts from biological invasions than mainland areas [25,26,27,28]. Numerous alien species, introduced intentionally or accidentally, have naturalized on islands, with some becoming invasive. These invaders have driven extensive extinctions of native species, while fundamentally altering trophic interactions and insular biodiversity patterns [29]. Despite these threats, recent research has focused predominantly on distribution of alien species in mainland areas [10,16,17,18], with comparatively limited attention given to heavily developed island ecosystems [19,20]. Accurate monitoring, documentation, and reporting of the alien species taxonomy, abundance, and traits on islands are critical. Such efforts facilitate the development by conservation agencies and governmental bodies of effective management strategies, encompassing habitat restoration, invasive species eradication, and ex situ conservation initiatives, that aim to mitigate biodiversity loss in island ecosystems [28].

China ranks among the countries with flora most severely affected by invasive alien plants (IAPs) [30]. Current floristic inventories document 14,710 alien plant species nationwide, including 984 naturalized and 391 invasive taxa [31]. However, while plant invasions have been well studied for mainland China, they remain poorly examined for its island ecosystems. Luo et al. [32] comprehensively surveyed IAPs on Pingtan Island (Fujian Province, China), identifying 104 invasive species and developing a risk assessment framework for island-specific invasion threats. Xie et al. [33] recorded 142 IAPs (spanning 102 genera and 38 families) across 77 islands of Fujian Province, China, identifying the proportions of built-up and agricultural areas, island size, and maximum elevation as the primary drivers of invasive species richness and growth patterns. Despite China’s national invasive species census [30], island invasion data remain limited in terms of detail and comprehensiveness. Although some studies have focused on IAPs on islands [19,32,33], broader alien and naturalized species pools on islands have rarely been investigated. This knowledge gap hinders the early detection of potential invaders and delays targeted management.

Guangxi, in southern China, is among the provinces most severely affected by biological invasions [34]. The number of IAPs in Guangxi increased from 74 in 2008 [35] to 180 in 2019 [36], with these species causing significant harm to local ecosystems. Weizhou Island, in the northern South China Sea, is the largest island in Guangxi [37]. Owing to its unique geographical location and natural landscape, the island has become a representative area for coastal tourism development and socioeconomic transformation in Guangxi Province [38]. Its geographical and climatic conditions, combined with a thriving tourism industry, and highly disturbed habitats create favorable conditions for the introduction, establishment, and spread of alien plants, posing significant risks of plant invasion. However, the composition of alien, naturalized, and invasive plants on Weizhou Island remains poorly understood, hindering the development of effective prevention and control measures against invasive species on this island.

To address this gap, we comprehensively inventorized the alien, naturalized, and invasive vascular plants on Weizhou Island, using plant specimen data and survey data for 112 plots. We aimed to examine the taxonomic composition, origins, life forms, and habitat preferences of its alien flora, to conduct an IAP risk assessment and to recommended management strategies for IAPs on islands. These findings provide new insights for the prevention and management of IAPs on Weizhou Island, thereby promoting the healthy development of the island ecosystem.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

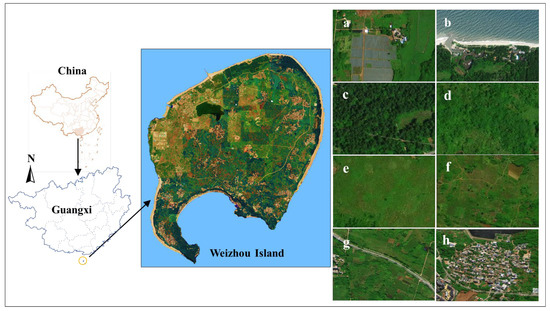

Weizhou Island (20°54′–21°10′ N, 109°00′–109°15′ E; Figure 1) falls administratively within Guangxi Province. With its nearest point 40 km from the mainland, the island covers a total area of 24.74 km2, reaching a maximum elevation of 79 m a.s.l. [37,39]. The island has a South Asian tropical maritime climate, with frequent typhoons and torrential rains during summer and autumn. This island has an average annual temperature of 22.6 °C, with January being the coldest month (15.3 °C) and July the warmest (28.9 °C). With an annual precipitation of 1380.2 mm and relative humidity averaging 82.0%, it ranks as one of Guangxi’s warmest and wettest regions [39]. As China’s youngest volcanic island, volcanic rock formations constitute >95.0% of its lithology. The soils are predominantly volcanic in origin, with basalt-derived lateritic red earth and sandy loam as the primary parent materials, and are characterized by high concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium [40]. In the northeast, the island is mostly cultivated, while orchards dominate in the central and southern areas. Forests (consisting mainly Casuarina equisetifolia, Leucaena leucocephala, and Acacia confusa plantations) are distributed primarily along the northern and southern coastal zones [39]. The island has a permanent population of 15,000, with densely populated areas clustered in the western sector. As a renowned Chinese 5A-class national tourist attraction, Weizhou Island received approximately 2.1353 million visitors in 2023 [38].

Figure 1.

Location and eight habitat types of Weizhou Island in the northern South China Sea. (a), agricultural land; (b), coastal zone, (c), plantation; (d), shrubland; (e), grassland; (f), abandoned farmland; (g), roadside; (h), residential area.

2.2. Field Survey

We conducted an extensive plant specimen collection [16] on Weizhou Island during 12 field surveys across different seasons from 2018 to 2024. Based on the island’s land-use types and vegetation conditions, and with reference to habitat classification method used for other island [32], we classified its habitats into eight categories: agricultural land, coastal zones, plantations, shrubland, grassland, abandoned farmland, roadsides, and residential areas. Across these habitat types, we collected 2352 plant specimens and deposited them in the herbarium of Nanning Normal University. Each specimen was annotated with taxonomic information, habitat type, and collection location [16]. Additionally, from July to August 2023–2024, we conducted plot surveys of the eight habitat types using plot sizes of 2 m × 2 m and 5 m × 5 m. In total, 46 survey sites were selected (four to nine sites per habitat type), with two to four plots at each site, resulting in 112 plots. Within each plot, we recorded the taxonomic composition of all plant species, the numbers of individuals, average height, coverage, abundance, and habitat type [32].

2.3. Identification as Alien, Naturalized, or Invasive

In studies of alien species, the definitions of “non-native,” “non-indigenous,” “naturalized,” and “invasive” are often conflated [41,42], leading to discrepancies in the reported abundances and impact ranges of aliens [43]. To better characterize the composition of plants on Weizhou Island, we adopted the following definitions: “alien” refers to species introduced beyond their natural native distribution range [44]. “Naturalized” (or “established”), a subset of “alien,” refers to plants that can form self-sustaining populations and complete multiple life cycles without direct human intervention [45]; and “invasive,” a subset of “naturalized,” refers to plants that exhibit high reproductive output and can spread over considerable distances [45]. Based on the collected specimen records and plot survey data, and referring to Lin et al. [31] and Hao and Ma [46], we inventorized the alien, naturalized, and invasive vascular plants on Weizhou Island. The native origins of the species were identified, following Lin et al. [31], as North America, Africa, South America, Asia, Europe, or Oceania. Life forms (tree, shrub, woody vine, herbaceous vine, annual herb, perennial herb, and bamboo) were determined based on field observations and using the approach of Lin et al. [31]. The habitat preferences of the invasive species were identified based on the habitat characteristics of the specimen collection sites and on plot locations.

2.4. Data Analysis

We employed Sankey diagrams to visualize the top ten families and genera, along with seven life form types, based on their species contributions to the alien flora. Additionally, chord diagram was used to display the six phytogeographic origins of the alien flora. All figures were generated using Origin 2023 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

Invasion Risk Assessment, a tool for proactively identifying high-risk plants with potential ecological or economic impacts, forms the foundation for alien species risk management [47]. The risk assessment evaluates invasive species across multiple dimensions, including invasion history, environmental adaptability, growth traits, biological characteristics, dispersal mechanisms and capacity, potential hazards and impacts, and difficulties in containment and quarantine. Here, we adopted the Analytic Hierarchy Process-based framework, a widely used weighting-based decision-making method that hierarchically quantifies criteria and combines qualitative and quantitative analyses, to assess alien plant invasion risk [48]. The final risk levels were classified using composite scores (p-values, maximum 100) derived from a hierarchical evaluation system comprising seven primary indicators, 17 secondary indicators, and 55 tertiary indicators [32,48,49]. The total P value reflects the sum of the weighted indicator scores and correlates positively with risk magnitude. This early warning system categorizes risks into three tiers: high-risk (p ≥ 40), requiring enhanced control measures and strict quarantine protocols; moderate-risk (33 ≤ p < 40), requiring preventive intervention; and low-risk (p < 33), requiring monitoring but no immediate action [48].

3. Results

3.1. Floral Composition

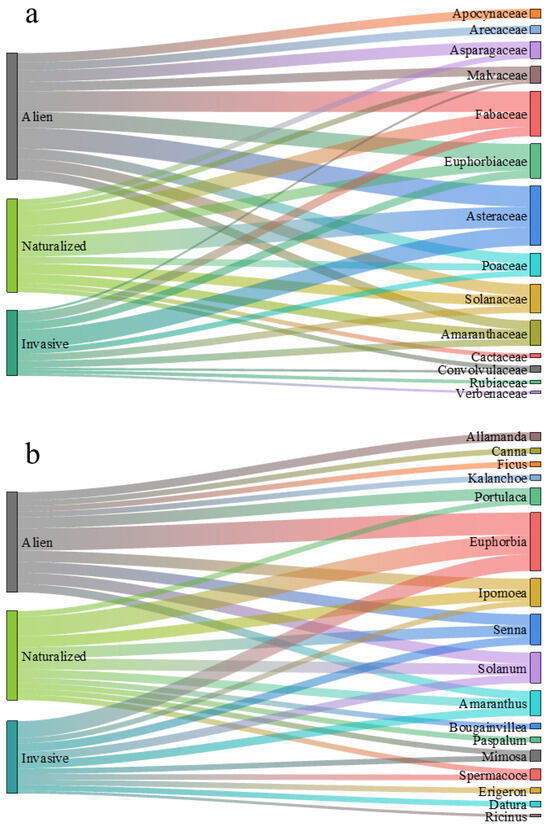

We identified 203 alien vascular plant species (in 55 families and 162 genera) on Weizhou Island, including 129 naturalized species (41 families and 100 genera) and 71 invasive species (48 families and 55 genera) (Appendix A Table A1). Asteraceae, Fabaceae, and Euphorbiaceae exhibited dominated among the alien, naturalized, and invasive species (Figure 2a). Monotypic families (i.e., those containing only one species) accounted for 22, 18, and 14 families in the alien, naturalized, and invasive species pools, respectively (Appendix A Table A1). At the genus level, Euphorbia, Senna, and Amaranthus were the most species-rich genera across all categories (Figure 2b), whereas monotypic genera numbered 137, 83, and 46 for alien, naturalized, and invasive species, respectively (Appendix A Table A1). Among the alien plants, naturalization rates reached 100.0% in Asteraceae (18 species), 100.0% in Amaranthaceae (eight species), 90.0% in Solanaceae (10 species), and 73.0% in Fabaceae (18 species), whereas their respective invasion rates were 88.9%, 75.0%, 60.0%, and 44.0%. All three alien species of Amaranthus were found to be invasive. In contrast, naturalization rates of 87.5%, 100.0%, and 100.0% were observed for Euphorbia (eight species), Senna (four species), and Solanum (four species), respectively, with invasion rates of 75.0%, 75.0%, and 60.0%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Top ten families (a) and genera (b) in terms of number of species contributing to the alien flora on Weizhou Island.

3.2. Origin

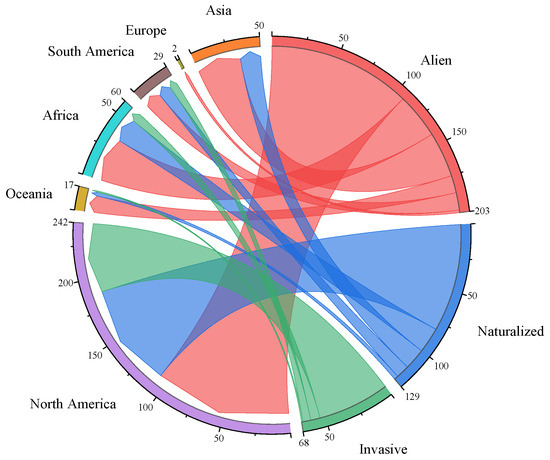

The alien plants on Weizhou Island originated primarily from North America (107 species), Africa (34), Asia (34), South America (13), Oceania (13), and Europe (2) (Figure 3, Appendix A Table A1). Among the naturalized plants, 81 species were native to North America, 19 to Africa, 16 to Asia, 10 to South America, and three to Oceania, with no European-origin naturalizations (Figure 3, Appendix A Table A1). The invasive species were predominantly from North America (54 species), contrasting sharply with lower counts from Africa (7), South America (6), Asia (3), and Oceania (1) (Figure 3, Appendix A Table A1). Notably, 50.5% of the North American and 46.2% of the South American alien plants identified were invasive (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phytogeographic origins of the alien flora on Weizhou Island.

3.3. Life Form

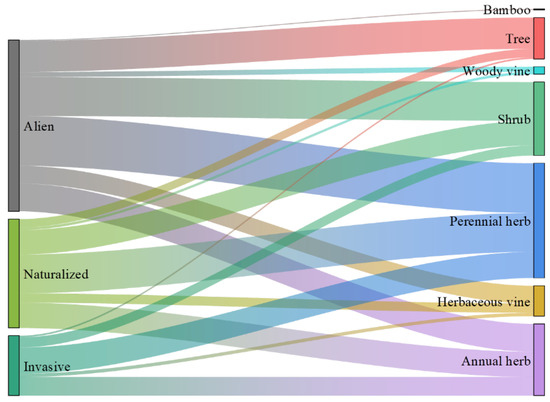

The alien flora of Weizhou Island was dominated by perennial herbs (59 species), followed by shrubs (46), trees (37), annual herbs (33), and herbaceous vines (21), with only six woody vine and one bamboo species recorded (Figure 4, Appendix A Table A1). Among the naturalized plants, perennial herbs (46 species), annual herbs (30), and shrubs (29) were the most prevalent, whereas herbaceous vines (11), trees (10), and woody vines (3) were less common, and no bamboo species were naturalized (Figure 4, Appendix A Table A1). Invasive species were similarly dominated by perennial herbs (31 species) and annual herbs (22), with 12 shrub species but only four herbaceous vines, two trees, and no woody vines being invasive (Figure 4, Appendix A Table A1). Of the aliens, 66.7% of the annual herbs and 52.5% of the perennial herbs were invasive, compared with 21.8% of the shrubs, 19.0% of the herbaceous vines, and 5.4% of the trees (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Life forms of the alien flora on Weizhou Island.

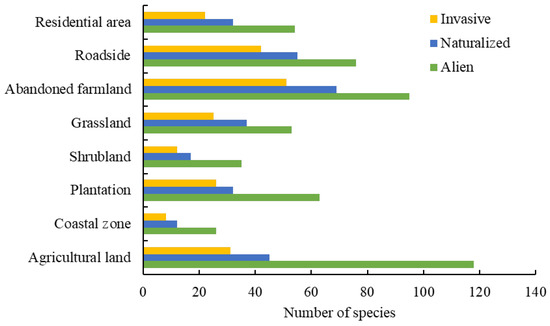

3.4. Habitat

All eight habitat types on Weizhou Island harbored a substantial number of alien plant species (Figure 5). Alien species were predominantly found on agricultural land (118 species), abandoned farmland (95), roadsides (76), and plantations (63). Notably, alien species exhibited higher naturalization rates on abandoned farmland (69 species, 72.6%), roadsides (55, 72.4%), and grassland (37, 69.8%) and lower rates on agricultural land (38.1%) and in coastal zones (46.1%). Invasive species were most prevalent in abandoned farmland (51 species), roadsides (42), and agricultural lands (31) and less common in shrublands (12) and coastal zones (8). On roadsides, abandoned farmland, and grassland, 55.3%, 53.7%, and 47.2% of the aliens were invasive (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Alien flora species distribution by habitats for Weizhou Island.

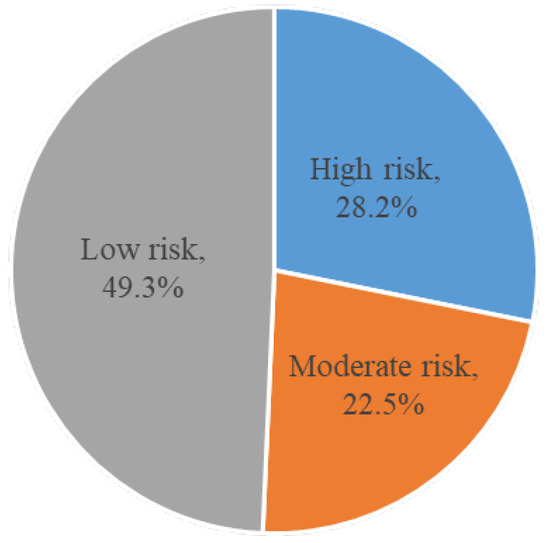

3.5. Risk Assessment

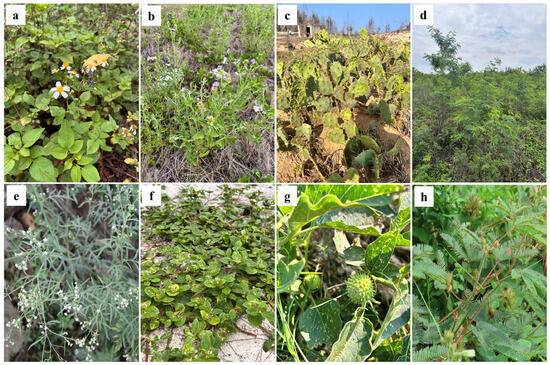

Based on risk assessment, 20 (28.2%) of the 71 IAPs were classified as high-risk (p ≥ 40) (Figure 6, Appendix A Table A1). These included Bidens pilosa (Figure 7a), Ageratum conyzoides (Figure 7b), Opuntia dillenii (Figure 7c), and Leucaena leucocephala (Figure 7d). Sixteen species (22.5%), including Parthenium hysterophorus (Figure 7e), Richardia scabra (Figure 7f), Datura stramonium (Figure 7g), and Mimosa pudica (Figure 7h), were categorized as moderate-risk (33 ≤ p < 40) (Figure 6, Appendix A Table A1). The remaining 35 species (49.3%), including Mirabilis jalapa, Pilea microphylla, Gomphrena celosioides, and Hydrocotyle verticillata, were classified as low-risk (p < 33) (Figure 6, Appendix A Table A1).

Figure 6.

Invasion Risk Assessment levels of the invasive alien plants on Weizhou Island, with species numbers.

Figure 7.

Photographs of selected invasive alien plants on Weizhou Island. (a), Bidens Pilosa; (b), Ageratum conyzoides; (c), Opuntia dillenii; (d), Leucaena leucocephala; (e), Parthenium hysterophorus; (f), Richardia scabra; (g), Datura stramonium; (h), Mimosa pudica.

4. Discussion

4.1. Status of Alien Flora on Weizhou Island

This study identified 203 alien vascular plant species (in 55 families and 162 genera), including 129 naturalized species (41 families and 100 genera) and 71 invasive species (48 families and 55 genera); 63.5% of the alien species were naturalized, and 55.0% of the naturalized species were invasive. Recent surveys have indicated that Weizhou Island hosts 608 vascular plant species (126 families and 427 genera) [50]; alien plants therefore constitute 33.4% of the total flora, whereas naturalized and invasive species account for 21.2% and 11.7%, respectively. Notably, although Weizhou Island (24.74 km2) represents only 0.01% of Guangxi’s land area (237,600 km2), it harbors 39.4% of its 180 documented IAPs [36]. While Pingtan Island (324.13 km2 in Fujian province) has 104 invasive species, Weizhou has 68.3% as many [32], despite covering only 7.6% of its area, with high levels of species similarity between the two islands. Invasive species typically have a magnified impact on small islands, owing to their smaller populations of native species [26,27,28]. Our findings provide evidence that small islands such as Weizhou Island face worse plant invasions than mainland areas or larger islands such as Pingtan, which is consistent with previous findings [20,23,27]. The high proportions of alien, naturalized, and invasive vascular plants on Weizhou Island suggest that it has experienced acute biological invasions, potentially leading to ecosystem damage. The urgent implementation of invasive species management strategies is imperative for mitigating further biodiversity loss in small island ecosystems.

Among the alien, naturalized, and invasive plants on Weizhou Island, Asteraceae, Fabaceae, and Euphorbiaceae exhibited the highest species richness, with these families exhibiting high rates of invasiveness. The genera with the most invasive species were Euphorbia, Senna, Amaranthus, and Solanum, revealing that Weizhou Island shares compositional similarities in terms of invasive plant families and genera with mainland China [10,31,51] and other islands [19,32]. Notably, Asteraceae, Fabaceae, and Poaceae, among the world’s largest plant families, are major contributors to global [5] and regional [16,31] alien flora. Their widespread introduction is closely tied to their economic value; approximately 50.0% of alien Asteraceae species in China were introduced as ornamentals and 42.0% of Poaceae species as forage crops, whereas Fabaceae species were introduced primarily as ornamentals or fodder [51]. Reproductive capacity and dispersal efficiency are critical determinants of invasion success [34]. Alien plants must produce and disseminate sufficient numbers of propagules in novel environments to establish invasive populations [52]. Consequently, the dominance of Asteraceae, Fabaceae, and Euphorbiaceae is linked to their superior long-distance dispersal capacity, establishment success, colonization ability, and environmental adaptability [53].

The majority of the alien plants on Weizhou Island originated from North America, Africa, and Asia, with naturalized and invasive species exhibiting the same pattern. The geographical origins of naturalized species may influence their invasiveness in newly introduced regions [54]. The origins of the alien plants in this study are consistent with the reported origins of non-native flora in China and other islands [31,32]. IAPs from similar climatic zones as the invaded island exhibit stronger adaptability and higher rates of colonization and dispersal [18]. Studies suggest that most of its invasive species on an island originate from within the same climatic zone as the island [19,20,23]. Within Weizhou Island’s alien flora, species from North America dominate, primarily because their naturalization success is enhanced by climatic and biogeographic similarities. China and North America share numerous analogous environments and associated biomes, which may increase their mutual susceptibility to immigrant species. The surge in trade between China and the Americas over recent decades has likely facilitated a substantial increase in the introduction of plant propagules from North America [34,55]. The high proportions of alien, naturalized, and invasive plants from Africa and Asia on Weizhou Island are similarly related to climatic conditions, trade, and tourism.

Perennial herbs dominate the alien flora of Weizhou Island, with 66.7% of perennial and 52.5% of annual herbaceous alien species becoming invasive, while shrubs and lianas exhibit lower invasion rates (e.g., 5.4% for trees). This is consistent with the global tendency for herbaceous taxa to dominate among alien, naturalized, and invasive plant assemblages [5]. Similar herbaceous dominance characterizes the alien flora of both China and Guangxi [31,36]. The perennial life history, often associated with vegetative reproduction and clonal growth, may contribute significantly to invasion success [56]. Herbaceous aliens exhibit better competitive ability and greater phenotypic plasticity than most native species, owing to their rapid reproduction, high seed output, efficient dispersal of small propagules, and strong invasive capacity [57]. The limited occurrence of naturalized and invasive woody plants (trees and shrubs) likely relates to their deliberate introduction for horticulture, timber production, and coastal erosion control, with subsequent escape from cultivation. However, the invasive tree species Leucaena leucocephala has become dominant in some plant communities on Weizhou Island, causing significant ecological impacts.

All eight habitat types on Weizhou Island experienced varying degrees of alien plant invasion, with high species richness observed on abandoned farmland, roadsides, and agricultural land. Anthropogenically modified habitats typically exhibit elevated invasion levels owing to heightened human disturbance and propagule pressure [58]. Compared with mainland areas, island ecosystems exhibit higher rates of habitat occupancy by alien plants and face greater threats from invasive species [19,32]. Alien species dominate on abandoned farmland, roadsides, and agricultural land as the frequent human disturbance associated with these habitats creates many opportunities for colonization [59]. Roads serve dual roles as both reservoirs for invasive plant propagules and dispersal corridors [60]. The development of infrastructure, including roads, ports, urban areas, villages, and modified coastal zones, amplifies propagule pressure while enhancing the dispersal efficiency and colonization potential of alien plants. The diverse habitat types of Weizhou Island may accommodate large numbers of individuals of IAPs, facilitating their dispersal and establishment. This highlights the importance of implementing management strategies to prevent the spread of invasive species and their negative effects in these vulnerable habitats.

4.2. Risk Assessment of IAPs on Weizhou Island

We classified the 71 IAPs as high-risk (20 species, 28.2%), moderate-risk (16 species, 22.5%), and low-risk (35 species, 49.3%). The high-risk alien species have adapted to most of the adverse conditions on Weizhou Island and are extremely common there. For instance, IAPs such as Bidens pilosa, Ageratum conyzoides, Erigeron canadensis, Crassocephalum crepidioides, Symphyotrichum subulatum, Praxelis clematidea, Lantana camara, Spermacoce alata, and Ipomoea cairica dominate in many of the plant communities in and around the island’s villages, exhibiting high population densities and coverage rates. Six species—Lantana camara, Mikania micrantha, Sphagneticola trilobata, Eichhornia crassipes, Leucaena leucocephala, and Opuntia stricta—are among the 100 most invasive alien species globally, according to the IUCN [61]. Leucaena leucocephala and Opuntia stricta have become dominant in the coastal vegetation (Figure 7c,d), displacing the native coastal plants and altering the natural landscape. Originally introduced as fuelwood, Leucaena leucocephala has exhibited rapid growth and strong regenerative capacity over the past decade, spreading across most of the island as the demand for firewood has declined. The recently introduced Mikania micrantha exhibits extreme invasiveness and rapid dispersal and has established populations at multiple sites on the island. Moderate-risk IAPs, including Parthenium hysterophorus, Richardia scabra, Datura stramonium, and Mimosa pudica, have caused localized damage. Introduced ornamental species such as Mirabilis jalapa, Pilea microphylla, and Hydrocotyle verticillata currently pose a low invasion risk but require monitoring owing to their documented impacts in mainland China [46]. The dynamics of their distribution on the island thus require special attention.

Many of these IAPs were introduced to the island for cultivation. Subsequent neglect following their intentional introduction has enabled them to occupy substantial habitats, outcompeting the native flora and impeding its survival and growth [29]. IAPs have severely affected the island’s ecosystems, causing ecological degradation and biodiversity loss, and further unchecked invasion may lead to the replacement and local extinction of indigenous species. Species with documented histories of invasion on oceanic islands are more likely to invade other islands than naturalized alien species [19,20]. Consequently, the naturalized and invasive species identified here likely pose high risks of naturalization or invasion for other South China Sea islands.

4.3. Invasion Mechanisms of Alien Species on Weizhou Island

The exceptionally high richness of naturalized and invasive plants on islands is due to biogeographic (e.g., smaller regional species pools and unsaturated island communities), ecological (e.g., competitively weaker native species), and socioeconomic (e.g., tourism development, farmland abandonment, and coastal anthropogenic activity) factors [19,20,62]. Disturbance intensity (i.e., habitat quality) plays a decisive role in invasion levels, with alien species becoming established more readily in disturbed than in pristine habitats [63,64]. Weizhou Island has endured prolonged intensive anthropogenisation, initially from agricultural expansion and natural resource extraction (e.g., logging), and more recently from urbanization and tourism development [40,50]. These factors are closely associated with the island’s disproportionately high numbers of alien, naturalized, and invasive plants. Weizhou Island has also experienced frequent natural disturbances such as typhoons and tropical storms, which can cause destructive impacts in forests, creating large canopy openings [65]. The current high rates of disturbance, whether anthropogenic or natural, likely facilitate the successful establishment of invasive populations on the island. Most of the naturalized species on the island were intentionally introduced as ornamental, agricultural, or forestry species [66]. Among these, escaped ornamental plants represent the largest source of the naturalized aliens. Considering that plant introductions on the island are driven by the boom in tourism-related landscaping [22,27], this pathway likely constitutes the primary source of naturalized species.

5. Conclusions

By providing the first complete inventory of the alien, naturalized, and invasive plants on Weizhou Island, this study contributes to bridging the knowledge gap regarding the occurrence of alien species on South China Sea islands. In total, 203 IAP (55 families and 162 genera), 129 naturalized species (41 families and 100 genera), and 71 invasive species (48 families and 55 genera) were found on Weizhou Island, accounting for 33.4%, 21.2%, and 11.7% of the island’s vascular flora, respectively. Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Amaranthaceae, Solanaceae, and Poaceae dominated the alien, naturalized, and invasive flora. The predominant life forms were perennial and annual herbs, with North America being the most common origin, likely due to the island’s tropical climate and climatic similarity to North America. This finding highlights the need for strict control of the introduction of alien herbaceous plants into America. Invasive species were identified in all of the island’s habitat types, with higher abundances on abandoned farmland, roadside areas, and agricultural land. Risk assessment identified 20 high-risk, 16 moderate-risk, and 35 low-risk species. Priority species for management included Bidens pilosa, Ageratum conyzoides, Opuntia dillenii, and Leucaena leucocephala. This inventory enriches the global data on island alien flora and will support future monitoring, risk assessment, and invasion management. These findings are critical for protecting island ecosystems and promoting sustainable ecological development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W.; methodology, H.W., X.W., and L.B.; software, H.W.; validation, H.W.; formal analysis, H.W.; investigation, H.W., X.W., and L.B.; resources, H.W., X.W., and L.B.; data curation, H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W. and X.W.; writing—review and editing, H.W. and L.B.; visualization, H.W.; supervision, H.W.; project administration, H.W.; funding acquisition, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Opening Foundation of Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Resources Use in Beibu Gulf Ministry of Education (Nanning Normal University) and the Guangxi Key Laboratory of Earth Surface Processes and Intelligent Simulation (Nanning Normal University), grant number NNNU-KLOP-K2526.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

An inventory of alien flora on Weizhou Island in the northern South China Sea.

Table A1.

An inventory of alien flora on Weizhou Island in the northern South China Sea.

| Species Name | Family | Status | Life Form | Origin | Risk Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruellia simplex | Acanthaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | North America | |

| Justicia gendarussa | Acanthaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | Asia | |

| Thunbergia alata | Acanthaceae | Naturalized | Herbaceous vine | Africa | |

| Amaranthus spinosus | Amaranthaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 38 |

| Amaranthus polygonoides | Amaranthaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 22 |

| Alternanthera philoxeroides | Amaranthaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | South America | 47 |

| Gomphrena globosa | Amaranthaceae | Naturalized | Annual herb | North America | |

| Celosia argentea | Amaranthaceae | Naturalized | Annual herb | Africa | |

| Dysphania ambrosioides | Amaranthaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 34 |

| Gomphrena celosioides | Amaranthaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | South America | 27 |

| Amaranthus viridis | Amaranthaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 33 |

| Hippeastrum striatum | Amaryllidaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | South America | |

| Annona squamosa | Annonaceae | Casual alien | Tree | North America | |

| Allamanda schottii | Apocynaceae | Casual alien | Woody vine | North America | |

| Thevetia peruviana | Apocynaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | North America | |

| Plumeria rubra | Apocynaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | North America | |

| Nerium oleander | Apocynaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | Africa | |

| Allamanda cathartica | Apocynaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | North America | |

| Calotropis procera | Apocynaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | Africa | |

| Catharanthus roseus | Apocynaceae | Invasive | Shrub | Africa | 40 |

| Allamanda blanchetii | Apocynaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | North America | |

| Syngonium podophyllum | Araceae | Naturalized | Herbaceous vine | North America | |

| Epipremnum aureum | Araceae | Casual alien | Herbaceous vine | Oceania | |

| Colocasia esculenta | Araceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | Asia | |

| Schefflera macrostachya | Araliaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Oceania | |

| Hydrocotyle verticillata | Araliaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 24 |

| Araucaria cunninghamii | Araucariaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Oceania | |

| Roystonea regia | Arecaceae | Casual alien | Tree | North America | |

| Ravenea rivularis | Arecaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | Africa | |

| Wodyetia bifurcata | Arecaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Oceania | |

| Archontophoenix alexandrae | Arecaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Oceania | |

| Dypsis lutescens | Arecaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | Africa | |

| Washingtonia filifera | Arecaceae | Casual alien | Tree | North America | |

| Phoenix sylvestris | Arecaceae | Naturalized | Tree | Asia | |

| Chlorophytum comosum | Asparagaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | Africa | |

| Asparagus densiflorus | Asparagaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | Africa | |

| Furcraea foetida | Asparagaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | North America | |

| Sansevieria trifasciata | Asparagaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | Africa | |

| Agave sisalana | Asparagaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | North America | |

| Sansevieria trifasciata var. laurentii | Asparagaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | Africa | |

| Beaucarnea recurvata | Asparagaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | North America | |

| Agave americana | Asparagaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 21 |

| Dracaena fragrans | Asparagaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | Africa | |

| Cordyline fruticosa | Asparagaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | Oceania | |

| Zinnia peruviana | Asteraceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 25 |

| Chromolaena odorata | Asteraceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 47 |

| Bidens pilosa | Asteraceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 49 |

| Ageratum conyzoides | Asteraceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 48 |

| Praxelis clematidea | Asteraceae | Invasive | Annual herb | South America | 49 |

| Synedrella nodiflora | Asteraceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 34 |

| Sonchus oleraceus | Asteraceae | Naturalized | Annual herb | Africa | |

| Eclipta prostrata | Asteraceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | North America | |

| Sphagneticola trilobata | Asteraceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | South America | 45 |

| Galinsoga parviflora | Asteraceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 29 |

| Mikania micrantha | Asteraceae | Invasive | Herbaceous vine | North America | 42 |

| Erigeron canadensis | Asteraceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 46 |

| Crassocephalum crepidioides | Asteraceae | Invasive | Annual herb | Africa | 41 |

| Erigeron annuus | Asteraceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 43 |

| Parthenium hysterophorus | Asteraceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 39 |

| Tridax procumbens | Asteraceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 25 |

| Tithonia diversifolia | Asteraceae | Invasive | Shrub | North America | 30 |

| Symphyotrichum subulatum | Asteraceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 46 |

| Impatiens balsamina | Balsaminaceae | Naturalized | Annual herb | Asia | |

| Basella alba | Basellaceae | Naturalized | Herbaceous vine | North America | |

| Anredera cordifolia | Basellaceae | Invasive | Herbaceous vine | North America | 33 |

| Begonia cucullata var. hookeri | Begoniaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | North America | |

| Kigelia africana | Bignoniaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Africa | |

| Handroanthus chrysanthus | Bignoniaceae | Casual alien | Tree | North America | |

| Spathodea campanulata | Bignoniaceae | Naturalized | Tree | Africa | |

| Pyrostegia venusta | Bignoniaceae | Naturalized | Woody vine | North America | |

| Heliotropium indicum | Boraginaceae | Naturalized | Annual herb | South America | |

| Ananas comosus | Bromeliaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | South America | |

| Selenicereus undatus | Cactaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | North America | |

| Cereus peruvianus | Cactaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | South America | |

| Opuntia dillenii | Cactaceae | Invasive | Shrub | North America | 44 |

| Opuntia cochenillifera | Cactaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | North America | |

| Canna generalis | Cannaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | Europe | |

| Canna indica | Cannaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | North America | |

| Carica papaya | Caricaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | North America | |

| Stellaria aquatica | Caryophyllaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | Asia | |

| Drymaria cordata | Caryophyllaceae | Naturalized | Annual herb | North America | |

| Casuarina equisetifolia | Casuarinaceae | Naturalized | Tree | Asia | |

| Terminalia neotaliala | Combretaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Africa | |

| Tradescantia spathacea | Commelinaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | North America | |

| Ipomoea batatas | Convolvulaceae | Naturalized | Herbaceous vine | North America | |

| Ipomoea nil | Convolvulaceae | Invasive | Herbaceous vine | North America | 24 |

| Ipomoea aquatica | Convolvulaceae | Naturalized | Herbaceous vine | Africa | |

| Ipomoea cairica | Convolvulaceae | Invasive | Herbaceous vine | Africa | 43 |

| Kalanchoe daigremontiana | Crassulaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | Africa | |

| Bryophyllum pinnatum | Crassulaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | Africa | 31 |

| Kalanchoe gastonis-bonnieri | Crassulaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | Africa | |

| Benincasa hispida | Cucurbitaceae | Casual alien | Herbaceous vine | Asia | |

| Luffa acutangula | Cucurbitaceae | Casual alien | Herbaceous vine | Asia | |

| Cucumis sativus | Cucurbitaceae | Casual alien | Herbaceous vine | Asia | |

| Momordica charantia | Cucurbitaceae | Casual alien | Herbaceous vine | Asia | |

| Cucurbita moschata | Cucurbitaceae | Casual alien | Herbaceous vine | North America | |

| Luffa aegyptiaca | Cucurbitaceae | Casual alien | Herbaceous vine | Asia | |

| Citrullus lanatus | Cucurbitaceae | Casual alien | Herbaceous vine | Africa | |

| Euphorbia heterophylla | Euphorbiaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 21 |

| Ricinus communis | Euphorbiaceae | Invasive | Shrub | Africa | 34 |

| Codiaeum variegatum | Euphorbiaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | Asia | |

| Jatropha integerrima | Euphorbiaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | North America | |

| Euphorbia hirta | Euphorbiaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 35 |

| Excoecaria cochinchinensis | Euphorbiaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | Asia | |

| Pedilanthus tithymaloides | Euphorbiaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | North America | |

| Euphorbia antiquorum | Euphorbiaceae | Invasive | Shrub | Asia | 21 |

| Euphorbia neriifolia | Euphorbiaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | North America | |

| Manihot esculenta | Euphorbiaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | South America | |

| Euphorbia milii | Euphorbiaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | Africa | |

| Euphorbia hypericifolia | Euphorbiaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 23 |

| Euphorbia cyathophora | Euphorbiaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 24 |

| Euphorbia pulcherrima | Euphorbiaceae | Invasive | Shrub | North America | 21 |

| Senna alata | Fabaceae | Invasive | Shrub | North America | 30 |

| Acacia auriculiformis | Fabaceae | Naturalized | Tree | Oceania | |

| Desmanthus virgatus | Fabaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 29 |

| Delonix regia | Fabaceae | Naturalized | Tree | Africa | |

| Mimosa bimucronata | Fabaceae | Invasive | Shrub | North America | 39 |

| Mimosa pudica | Fabaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 34 |

| Senna surattensis | Fabaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | Asia | |

| Erythrina crista-galli | Fabaceae | Casual alien | Tree | North America | |

| Vigna unguiculata | Fabaceae | Casual alien | Herbaceous vine | Africa | |

| Arachis hypogaea | Fabaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | South America | |

| Vigna radiata | Fabaceae | Naturalized | Herbaceous vine | Asia | |

| Acacia mangium | Fabaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Oceania | |

| Cassia bakeriana | Fabaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Asia | |

| Senna bicapsularis | Fabaceae | Invasive | Shrub | North America | 25 |

| Sesbania cannabina | Fabaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | Oceania | 35 |

| Senna occidentalis | Fabaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 24 |

| Caesalpinia pulcherrima | Fabaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | North America | |

| Leucaena leucocephala | Fabaceae | Invasive | Tree | North America | 49 |

| Mentha spicata | Lamiaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | Africa | |

| Tectona grandis | Lamiaceae | Naturalized | Tree | Asia | |

| Lagerstroemia speciosa | Lythraceae | Casual alien | Tree | Asia | |

| Punica granatum | Lythraceae | Casual alien | Shrub | Europe | |

| Sonneratia apetala | Lythraceae | Invasive | Tree | Asia | 25 |

| Michelia alba | Magnoliaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Asia | |

| Malvaviscus penduliflorus | Malvaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | North America | |

| Triumfetta rhomboidea | Malvaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | North America | |

| Pachira glabra | Malvaceae | Casual alien | Tree | North America | |

| Sida acuta | Malvaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | Asia | 22 |

| Abelmoschus esculentus | Malvaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | Asia | |

| Ceiba speciosa | Malvaceae | Casual alien | Tree | North America | |

| Malvastrum coromandelianum | Malvaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 41 |

| Sida cordata | Malvaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | Asia | |

| Maranta arundinacea | Marantaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | North America | |

| Thalia dealbata | Marantaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 21 |

| Artocarpus heterophyllus | Moraceae | Casual alien | Tree | Asia | |

| Ficus lyrata | Moraceae | Casual alien | Tree | Africa | |

| Ficus religiosa | Moraceae | Naturalized | Tree | Asia | |

| Melaleuca cajuputi subsp. cumingiana | Myrtaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Asia | |

| Psidium guajava | Myrtaceae | Naturalized | Tree | North America | |

| Callistemon rigidus | Myrtaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Oceania | |

| Xanthostemon chrysanthus | Myrtaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Oceania | |

| Eucalyptus grandis × urophylla | Myrtaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Oceania | |

| Syzygium samarangense | Myrtaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Asia | |

| Bougainvillea glabra | Nyctaginaceae | Naturalized | Woody vine | North America | |

| Bougainvillea spectabilis | Nyctaginaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | North America | |

| Mirabilis jalapa | Nyctaginaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 24 |

| Jasminum sambac | Oleaceae | Casual alien | Woody vine | Asia | |

| Oxalis corymbosa | Oxalidaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 35 |

| Averrhoa carambola | Oxalidaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Asia | |

| Pandanus utilis | Pandanaceae | Casual alien | Shrub | Africa | |

| Passiflora edulis | Passifloraceae | Naturalized | Herbaceous vine | North America | |

| Phyllanthus amarus | Phyllanthaceae | Naturalized | Annual herb | North America | |

| Phyllanthus tenellus | Phyllanthaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | Africa | 25 |

| Pittosporum tobira | Pittosporaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | Asia | |

| Plumbago auriculata | Plumbaginaceae | Casual alien | Herbaceous vine | Africa | |

| Axonopus compressus | Poaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 32 |

| Saccharum officinarum | Poaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | Asia | |

| Paspalum vaginatum | Poaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | North America | |

| Spartina alterniflora | Poaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 40 |

| Cenchrus echinatus | Poaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 36 |

| Bambusa blumeana | Poaceae | Casual alien | Bamboo | Asia | |

| Panicum repens | Poaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | Africa | 35 |

| Paspalum distichum | Poaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 30 |

| Zea mays | Poaceae | Casual alien | Annual herb | North America | |

| Pontederia crassipes | Pontederiaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 47 |

| Portulaca grandiflora | Portulacaceae | Naturalized | Annual herb | South America | |

| Portulaca umbraticola | Portulacaceae | Casual alien | Annual herb | North America | |

| Portulaca pilosa | Portulacaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 26 |

| Portulaca quadrifida | Portulacaceae | Casual alien | Annual herb | North America | |

| Macadamia integrifolia | Proteaceae | Casual alien | Tree | Oceania | |

| Spermacoce remota | Rubiaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 25 |

| Spermacoce alata | Rubiaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 46 |

| Richardia scabra | Rubiaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 37 |

| Manilkara zapota | Sapotaceae | Casual alien | Tree | North America | |

| Solanum lycopersicum | Solanaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | North America | |

| Physalis angulata | Solanaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 25 |

| Capsicum annuum | Solanaceae | Naturalized | Perennial herb | North America | |

| Solanum americanum | Solanaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 30 |

| Solanum torvum | Solanaceae | Invasive | Shrub | North America | 27 |

| Nicotiana tabacum | Solanaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | North America | |

| Datura metel | Solanaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | North America | 25 |

| Cestrum nocturnum | Solanaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | North America | |

| Solanum capsicoides | Solanaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | South America | 27 |

| Datura stramonium | Solanaceae | Invasive | Annual herb | North America | 33 |

| Ravenala madagascariensis | Strelitziaceae | Casual alien | Perennial herb | Africa | |

| Pilea microphylla | Urticaceae | Invasive | Perennial herb | South America | 28 |

| Duranta erecta | Verbenaceae | Naturalized | Shrub | North America | |

| Stachytarpheta jamaicensis | Verbenaceae | Invasive | Shrub | North America | 23 |

| Lantana camara | Verbenaceae | Invasive | Shrub | North America | 47 |

| Cissus verticillata | Vitaceae | Naturalized | Woody vine | North America | |

| Vitis vinifera | Vitaceae | Casual alien | Woody vine | Asia |

References

- Pyšek, P.; Richardson, D.M. Invasive Species, Environmental Change and Management, And Health. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Simberloff, D.; Bacher, S.; Blackburn, T.M.; Carlton, J.T.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Foxcroft, L.C.; Genovesi, P.; et al. Scientists’ Warning on Invasive Alien Species. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1511–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInerney, P.J.; Doody, T.M.; Davey, C.D. Invasive species In the Anthropocene: Help or Hindrance? J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, H.E.; Pauchard, A.; Stoett, P.; Renard Truong, T.; Bacher, S.; Galil, B.S.; Hulme, P.E.; Ikeda, T.; Sankaran, K.; McGeoch, M.A.; et al. IPBES Invasive Alien Species Assessment: Summary for Policymakers (Version 3) Zenodo; University of Rhode Island: South Kingstown, RI, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kleunen, M.; Pyšek, P.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Kreft, H.; Pergl, J.; Weigelt, P.; Stein, A.; Dullinger, S.; König, C.; et al. The Global Naturalized Alien Flora (GloNAF) database. Ecology 2019, 106, e02542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyšek, P.; Pergl, J.; Essl, F.; Lenzner, B.; Dawson, W.; Kreft, H.; Weigelt, P.; Winter, M.; Kartesz, J.; Nishino, M.; et al. Naturalized Alien Flora of the World: Species diversity, taxonomic and phylogenetic patterns, geographic distribution and global hotspots of plant invasion. Preslia 2017, 89, 203–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagad, S.; Genovesi, P.; Carnevali, L.; Scalera, R.; Clout, M. IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group: Invasive Alien Species Information Management Supporting Practitioners, Policy Makers and Decision Takers. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2015, 6, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebens, H.; Bacher, S.; Blackburn, T.M.; Capinha, C.; Dawson, W.; Dullinger, S.; Genovesi, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Kleunen, M.; Kühn, I.; et al. Projecting the Continental Accumulation of Alien Species Through to 2050. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 27, 970–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kleunen, M.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Pergl, J.; Winter, M.; Weber, E.; Kreft, H.; Weigelt, P.; Kartesz, J.; Nishino, M.; et al. Global Exchange and Accumulation of Non-Native Plants. Nature 2015, 525, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Hu, X.; Yao, S.; Yu, M.; Ying, Z. Alien, Naturalized and Invasive Plants in China. Plants 2021, 10, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhkamov, T.; Kortz, A.; Hejda, M.; Brundu, G.; Pyšek, P. Naturalized Alien Flora of Uzbekistan: Species Richness, Origin and Habitats. Biol. Invasions 2024, 26, 2819–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagad, S.; Genovesi, P.; Carnevali, L.; Schigel, D.; McGeoch, M.A. Introducing the Global Register of Introduced and Invasive Species. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 170202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi, A.; Steiner, W.W.M.; Mack, R.N.; Simberloff, D. Toward a Global Information System for Invasive Species. BioScience 2000, 50, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffer, A.; Worm, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Meentemeyer, R. GIATAR: A Spatio-temporal Dataset of Global Invasive and Alien Species and Their Traits. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacher, S.; Ryan-Colton, E.; Coiro, M.; Cassey, P.; Galil, B.S.; Nuñez, M.A.; Ansong, M.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Fayvush, G.; Fernandez, R.D.; et al. Global Impacts Dataset of Invasive Alien Species (GIDIAS). Sci. Data 2025, 12, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spampinato, G.; Laface, V.L.A.; Posillipo, G.; Cano Ortiz, A.; Quinto Canas, R.; Musarella, C.M. Alien Flora in Calabria (Southern Italy): An Updated Checklist. Biol. Invasions 2022, 24, 2323–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, S.; Naqinezhad, A.; Kortz, A.; Hejda, M.; Gherekhloo, J.; Zand, E.; Pergl, J.; Brundu, G.; Pyšek, P. Alien Flora of Iran: Species Status, Introduction Dynamics, Habitats and Pathways. Biol. Invasions 2023, 25, 1359–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehangir, S.; Khan, S.M.; Ejaz, U.; Qurat-ul-Ain; Zahid, N.; Rashid, N.; Noshad, Q.; Din, Z.U.; Shoukat, A. Alien Flora of Pakistan: Taxonomic Composition, Invasion Status, Geographic Origin, Introduction Pathways, and Ecological Patterns. Biol. Invasions 2024, 26, 2435–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Huang, H.; Xie, X.; Ou, J.; Chen, Z.; Lu, X.; Kong, D.; Nong, L.; Lin, M.; Qian, Z.; et al. Landscape, Human Disturbance, and Climate Factors Drive the Species Richness of Alien Invasive Plants on Subtropical Islands. Plants 2024, 13, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Sandoval, J.; Ackerman, J.D.; Manuel-Angel Dueñas; Velez, J.; Díaz-Soltero, H. Habitat Affiliation of Non-Native Plant Species across Their Introduced Ranges on Caribbean Islands. Biol. Invasions 2024, 26, 2237–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Li, R.; Chi, X.; Chen, N.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F. Island Urbanization and Its Ecological Consequences: A Case Study in the Zhoushan Island, East China. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 76, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogué, S.; Santos, A.M.C.; Birks, H.J.B.; Björck, S.; Castilla-Beltrán, A.; Connor, S.; de Boer, E.J.; de Nascimento, L.; Felde, V.A.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; et al. The Human Dimension of Biodiversity Changes on Islands. Science 2021, 372, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Koukoulas, S.; Michelaki, C.; Galanidis, A. Anthropogenic and Environmental Determinants of Alien Plant Species Spatial Distribution on an Island Scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; Qian, S. Floristic Homogenization as a Result of the Introduction of Exotic Species in China. Divers. Distrib. 2022, 28, 2139–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D. Why Do Introduced Species Appear to Devastate Islands More than Mainland Areas. Pac. Sci. 1995, 49, 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzner, B.; Magallón, S.; Dawson, W.; Kreft, H.; König, C.; Pergl, J.; Pyšek, P.; Weigelt, P.; Kleunen, M.; Winter, M.; et al. Role of Diversification Rates and Evolutionary History as a Driver of Plant Naturalization Success. New Phytol. 2020, 229, 2998–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, J.C.; Meyer, J.Y.; Holmes, N.D.; Pagad, S. Invasive Alien Species on Islands: Impacts, Distribution, Interactions and Management. Environ. Conserv. 2017, 44, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, J.; Weigelt, P.; Cai, L.; Westoby, M.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; Cabezas, F.J.; Plunkett, G.M.; Ranker, T.M.; Triantis, K.M.; Trigas, P.; et al. Islands Are Key for Protecting the World’s Plant Endemism. Nature 2024, 634, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfadenhauer, W.G.; DiRenzo, G.V.; Bradley, B.A. Human Activity Drives Establishment, but Not Invasion, of Non-Native Plants on Islands. Ecography 2024, 11, e07379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, R.; Gui, X.; Measey, J.; He, Q.; Xian, X.; Liu, J.; Sutherland, W.J.; Li, B.; Wu, J. How Can China Curb Biological Invasions to Meet Kunming-Montreal Target 6? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2025, e2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Xiao, C.; Ma, J.A. Dataset on Catalogue of Alien Plants in China. Biodivers. Sci. 2022, 30, 22127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Xiao, L.; Chen, X.; Lin, K.; Liu, B.; He, Z.; Liu, J.; Zheng, S. Invasive Alien Plants and Invasion Risk Assessment on Pingtan Island. Sustainability 2022, 14, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xie, X.; Weng, F.; Nong, L.; Lin, M.; Ou, J.; Wang, Y.; Mao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qian, Z.; et al. Distribution Patterns and Environmental Determinants of Invasive Alien Plants on Subtropical Islands (Fujian, China). Forests 2024, 15, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bian, Z.; Ren, W.; Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Shrestha, N. Spatial Patterns and Hotspots of Plant Invasion in China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 43, e02424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.C.; Lü, S.H.; He, C.X.; Li, X.K.; Pan, Y.M.; Pu, G.Z. The Alien Invasive Plants in Guangxi. Guihaia 2008, 28, 775–815. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.C.; Wei, C.Q.; Lü, S.H.; Pan, Y.M.; Li, X.K.; Pu, G.Z. Research on Alien Invasive Plants in Guangxi; Guangxi Science and Technology Publishing House: Nanning, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Q.; Fu, W.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Yu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Luo, P. Spatial Distribution Heterogeneity of Rare Earth Element Geochemistry in Island Soil Under the Joint Constraints of Volcanic Rock and Topography—A Case Study of Weizhou Island, Guangxi, China. Quat. Sci. 2021, 41, 1294–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dou, S.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y. Ecological Challenges on Small Tourist Islands: A Case from Chinese Rural Island. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 32, 1723–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, R.; Fu, W.; Fu, X. Heavy Metal Spatial Variation Mechanism and Ecological Health Risk Assessment in Volcanic Island Soils: A Case Study of Weizhou Island, China. Land 2024, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, R.; Fu, W.; Fu, X. Phosphorus Dynamics in Volcanic Soils of Weizhou Island, China: Implications for Environmental and Agricultural Applications. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colautti, R.I.; MacIsaac, H.J.A. Neutral Terminology to Define “Invasive” Species. Divers. Distrib. 2004, 10, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, I.; Balzani, P.; Carneiro, L.; Cuthbert, R.N.; Macedo, R.; Serhan Tarkan, A.; Ahmed, D.A.; Bang, A.; Bacela-Spychalska, K.; Bailey, S.A.; et al. Taming the Terminological Tempest in Invasion Science. Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 1357–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Bowler, P.; Xiong, W. Invasive Aquatic Plants in China. Aquat. Invasions 2016, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, C.S.; Lodge, D.M. Progress in Invasion Biology: Predicting Invaders. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, D.M.; Pysek, P.; Rejmanek, M.; Barbour, M.G.; Panetta, F.D.; West, C.J. Naturalization and Invasion of Alien Plants: Concepts and Definitions. Divers. Distrib. 2000, 6, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q.; Ma, J.S. Invasive Alien Plants in China: An Update. Plant Divers. 2022, 45, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieurance, D.; Canavan, S.; Behringer, D.C.; Kendig, A.E.; Minteer, C.R.; Reisinger, L.S.; Romagosa, C.M.; Flory, S.L.; Lockwood, J.L.; Anderson, P.J.; et al. Identifying Invasive Species Threats, Pathways, And Impacts to Improve Biosecurity. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Deng, H.; Zuo, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Qin, Q.; Yang, C. Spatial Distribution Pattern and Risk Assessment of Invasive Alien Plants on Southern Side of the Daba Mountain Area. Diversity 2022, 14, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashari, H.; Bazgir, F.; Vahabi, M.R. Prioritizing the Risk of Multiple Invasive Species in the Semiarid Rangelands of Iran: An Ecological Approach to Multicriteria Decision-Making. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Luo, Y.H.; Lin, J.Y.; Li, X.; Liang, S.; Yang, G.; Li, L.M.; Yu, G.D. Investigation and Analysis of Plant Diversity in Weizhou and Xieyang Islands of Guangxi. Guangxi For. Sci. 2023, 52, 629–635. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Fan, Q.; Li, J.T.; Shi, S.; Li, S.P.; Liao, W.B.; Shu, W.S. Naturalization of Alien Plants in China. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 20, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.A.; Atwater, D.Z.; Haak, D.C.; Bagavathiannan, M.V.; DiTommaso, A.; Lehnhoff, E.; Paterson, A.H.; Auckland, S.; Govindasamy, P.; Lemke, C.; et al. Adaptive Constraints at the Range Edge of a Widespread and Expanding Invasive Plant. AoB Plants 2023, 15, plad070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, R.P.; Silveira, M.J.; Petsch, D.K.; Mormul, R.P.; Thomaz, S.M. The Success of an Invasive Poaceae Explained by Drought Resilience but Not by Higher Competitive Ability. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 194, 104717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arianoutsou, M.; Bazos, I.; Christopoulou, A.; Kokkoris, Y.; Zikos, A.; Zervou, S.; Delipetrou, P.; Cardoso, A.C.; Deriu, I.; Gervasini, E.; et al. Alien Plants of Europe: Introduction Pathways, Gateways and Time Trends. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, E.; Sun, S.G.; Li, B. Invasive Alien Plants in China: Diversity and Ecological Insights. Biol. Invasions 2008, 10, 1411–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Deane, D.C.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Sui, X.; Xu, H.; Chu, C.; He, F.; Fang, S. Invasion Success and Impacts Depend on Different Characteristics in Non-Native Plants. Divers. Distrib. 2021, 27, 1194–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbau, A.; Stout, J.C. Factors Associated with Alien Plants Transitioning from Casual, to Naturalized, to Invasive. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubino, J.P.; Těšitel, J.; Fibich, P.; Lepš, J.; Chytrý, M. Alien Plants Tend to Occur in Species-Poor Communities. NeoBiota 2022, 73, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.E.; Callaham, M.A.; Stewart, J.E.; Warren, S.D. Invasive Species Response to Natural and Anthropogenic Disturbance. In Invasive Species in Forests and Rangelands of the United States; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gioria, M.; Hulme, P.E.; Richardson, D.M.; Pyšek, P. Why Are Invasive Plants Successful? Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 635–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, S.; Browne, M.; Boudjelas, S.; De Poorter, M. 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species: A Selection from the Global Invasive Species Database; Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG): Auckland, New Zealand, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Celesti-Grapow, L.; Bassi, L.; Brundu, G.; Camarda, I.; Carli, E.; D’aUria, G.; Del Guacchio, E.; Domina, G.; Ferretti, G.; Foggi, B.; et al. Plant Invasions on Small Mediterranean Islands: An Overview. Plant Biosyst. 2016, 150, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catford, J.A.; Vesk, P.A.; White, M.D.; Wintle, B.A. Hotspots of Plant Invasion Predicted by Propagule Pressure and Ecosystem Characteristics. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Sandoval, J.; Acevedo-Rodríguez, P. Naturalization and Invasion of Alien Plants in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Biol. Invasions 2014, 17, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S.; Battaglia, L.L. Linking Responses of Native and Invasive Plants to Hurricane Disturbances: Implications for Coastal Plant Community Structure. Plant Ecol. 2021, 222, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambdon, W.P.; Hulme, E.P. Predicting the Invasion Success of Mediterranean Alien Plants from Their Introduction Characteristics. Ecography 2006, 29, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).